Submitted:

09 October 2024

Posted:

10 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

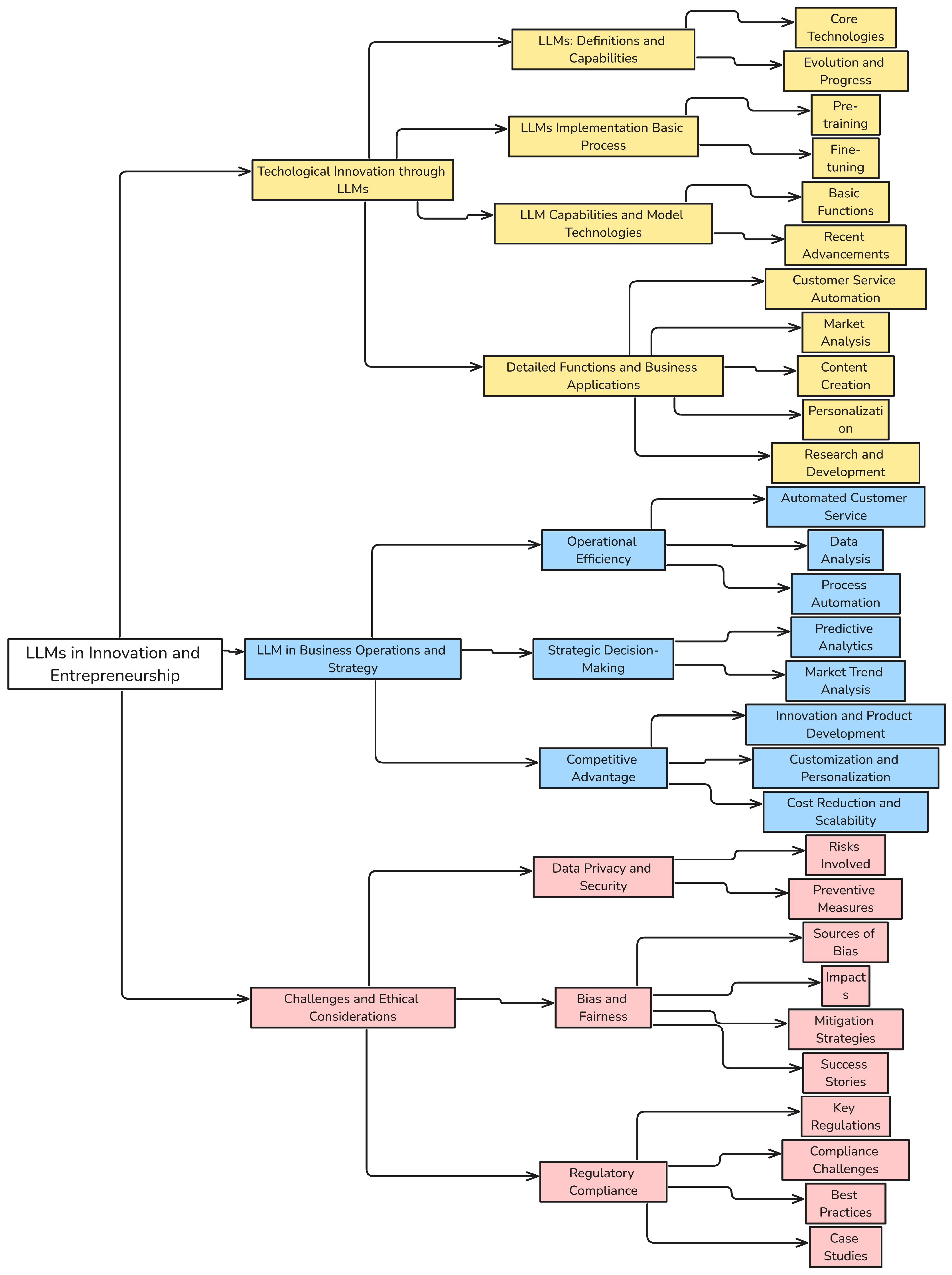

2. Technological Innovation through LLMs

2.1. LLMs: Definitions and Capabilities

2.2. LLMs Implementation Basic Process

2.3. LLM Capabilities and Model Technologies

2.4. Detailed Functions and Business Applications

- Personalization. Personalizing user experiences on digital platforms based on user behavior and preferences [58]. This increases customer loyalty and potentially higher sales through personalized recommendations and communications.

3. LLMs in Business Operations and Strategy

3.1. Operational Efficiency

3.2. Strategic Decision-Making

3.3. Competitive Advantage

4. Challenges and Ethical Considerations

4.1. Data Privacy and Security

4.2. Bias and Fairness

4.3. Regulatory Compliance

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Abd-Alrazaq, A., AlSaad, R., Alhuwail, D., Ahmed, A., Healy, P. M., Latifi, S., Aziz, S., Damseh, R., Alrazak, S. A., Sheikh, J., et al. (2023). Large language models in medical education: opportunities, challenges, and future directions. JMIR Medical Education, 9(1):e48291. [CrossRef]

- Adoma, A. F., Henry, N.-M., and Chen, W. (2020). Comparative analyses of bert, roberta, distilbert, and xlnet for text-based emotion recognition. In 2020 17th International Computer Conference on Wavelet Active Media Technology and Information Processing (ICCWAMTIP), pages 117–121. IEEE.

- Bahl, L. R., Brown, P. F., De Souza, P. V., and Mercer, R. L. (1989). A tree-based statistical language model for natural language speech recognition. IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 37(7):1001–1008. [CrossRef]

- Bellan, P., Dragoni, M., and Ghidini, C. (2022). Extracting business process entities and relations from text using pre-trained language models and in-context learning. In International Conference on Enterprise Design, Operations, and Computing, pages 182–199. Springer.

- Bengio, Y., Ducharme, R., and Vincent, P. (2000). A neural probabilistic language model. Advances in neural information processing systems, 13.

- Bert, C. W. and Malik, M. (1996). Differential quadrature method in computational mechanics: a review. [CrossRef]

- Birhane, A., Kasirzadeh, A., Leslie, D., and Wachter, S. (2023). Science in the age of large language models. Nature Reviews Physics, 5(5):277–280. [CrossRef]

- Carlini, N., Tramer, F., Wallace, E., Jagielski, M., Herbert-Voss, A., Lee, K., Roberts, A., Brown, T., Song, D., Erlingsson, U., et al. (2021). Extracting training data from large language models. In 30th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 21), pages 2633–2650.

- Chang, Y., Wang, X., Wang, J., Wu, Y., Yang, L., Zhu, K., Chen, H., Yi, X., Wang, C., Wang, Y., et al. (2024). A survey on evaluation of large language models. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 15(3):1–45.

- Chen, H., Mo, F., Wang, Y., Chen, C., Nie, J.-Y., Wang, C., and Cui, J. (2022). A customized text sanitization mechanism with differential privacy. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.01193.

- Chen, J., Liu, Z., Huang, X., Wu, C., Liu, Q., Jiang, G., Pu, Y., Lei, Y., Chen, X., Wang, X., et al. (2024). When large language models meet personalization: Perspectives of challenges and opportunities. World Wide Web, 27(4):42. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Zhang, Y., Ren, S., Zhao, H., Cai, Z., Wang, Y., Wang, P., Liu, T., and Chang, B. (2023). Towards end-to-end embodied decision making via multi-modal large language model: Explorations with gpt4-vision and beyond. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.02071.

- Choromanski, K., Likhosherstov, V., Dohan, D., Song, X., Gane, A., Sarlos, T., Hawkins, P., Davis, J., Belanger, D., Colwell, L., et al. (2020). Masked language modeling for proteins via linearly scalable long-context transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.03555.

- Chowdhery, A., Narang, S., Devlin, J., Bosma, M., Mishra, G., Roberts, A., Barham, P., Chung, H. W., Sutton, C., Gehrmann, S., et al. (2023). Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 24(240):1–113.

- Chowdhury, R., Bouatta, N., Biswas, S., Floristean, C., Kharkar, A., Roy, K., Rochereau, C., Ahdritz, G., Zhang, J., Church, G. M., et al. (2022). Single-sequence protein structure prediction using a language model and deep learning. Nature Biotechnology, 40(11):1617–1623. [CrossRef]

- Christian, H., Suhartono, D., Chowanda, A., and Zamli, K. Z. (2021). Text based personality prediction from multiple social media data sources using pre-trained language model and model averaging. Journal of Big Data, 8(1):68. [CrossRef]

- Collobert, R., Weston, J., Bottou, L., Karlen, M., Kavukcuoglu, K., and Kuksa, P. (2011). Natural language processing (almost) from scratch. Journal of machine learning research, 12:2493–2537.

- Crosman, P. (2019). Banking 2025: The rise of the invisible bank. American Banker.

- Dai, Z., Yang, Z., Yang, Y., Carbonell, J., Le, Q. V., and Salakhutdinov, R. (2019). Transformer-xl: Attentive language models beyond a fixed-length context. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.02860.

- Das, B. C., Amini, M. H., and Wu, Y. (2024). Security and privacy challenges of large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.00888.

- Delobelle, P., Tokpo, E. K., Calders, T., and Berendt, B. (2021). Measuring fairness with biased rulers: A survey on quantifying biases in pretrained language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.07447.

- Ding, H., Li, Y., Wang, J., and Chen, H. (2024). Large language model agent in financial trading: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.06361.

- Eloundou, T., Manning, S., Mishkin, P., and Rock, D. (2023). Gpts are gpts: An early look at the labor market impact potential of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.10130.

- Fan, X. and Tao, C. (2024). Towards resilient and efficient llms: A comparative study of efficiency, performance, and adversarial robustness. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.04585.

- Fan, X., Tao, C., and Zhao, J. (2024). Advanced stock price prediction with xlstm-based models: Improving long-term forecasting. Preprints.

- Gallegos, I. O., Rossi, R. A., Barrow, J., Tanjim, M. M., Kim, S., Dernoncourt, F., Yu, T., Zhang, R., and Ahmed, N. K. (2024). Bias and fairness in large language models: A survey. Computational Linguistics, pages 1–79. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. and Lin, C.-Y. (2004). Introduction to the special issue on statistical language modeling. [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Muñoz, I., Montejo-Ráez, A., Martínez-Santiago, F., and Ureña-López, L. A. (2021). A survey on bias in deep nlp. Applied Sciences, 11(7):3184. [CrossRef]

- Geng, S., Liu, S., Fu, Z., Ge, Y., and Zhang, Y. (2022). Recommendation as language processing (rlp): A unified pretrain, personalized prompt & predict paradigm (p5). In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, pages 299–315.

- George, A. S. and George, A. H. (2023). A review of chatgpt ai’s impact on several business sectors. Partners universal international innovation journal, 1(1):9–23.

- Geren, C., Board, A., Dagher, G. G., Andersen, T., and Zhuang, J. (2024). Blockchain for large language model security and safety: A holistic survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.20181.

- Goldberg, A. (2024). Ai in finance: Leveraging large language models for enhanced decision-making and risk management. Social Science Journal for Advanced Research, 4(4):33–40.

- Goldman, E. (2020). An introduction to the california consumer privacy act (ccpa). Santa Clara Univ. Legal Studies Research Paper.

- Grohs, M., Abb, L., Elsayed, N., and Rehse, J.-R. (2023). Large language models can accomplish business process management tasks. In International Conference on Business Process Management, pages 453–465. Springer.

- Gu, W., Zhong, Y., Li, S., Wei, C., Dong, L., Wang, Z., and Yan, C. (2024). Predicting stock prices with finbert-lstm: Integrating news sentiment analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.16150.

- Guo, M., Ainslie, J., Uthus, D., Ontanon, S., Ni, J., Sung, Y.-H., and Yang, Y. (2021). Longt5: Efficient text-to-text transformer for long sequences. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.07916.

- Gururangan, S., Marasović, A., Swayamdipta, S., Lo, K., Beltagy, I., Downey, D., and Smith, N. A. (2020). Don’t stop pretraining: Adapt language models to domains and tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.10964.

- Guu, K., Lee, K., Tung, Z., Pasupat, P., and Chang, M. (2020). Retrieval augmented language model pre-training. In International conference on machine learning, pages 3929–3938. PMLR.

- Hadi, M. U., Al Tashi, Q., Shah, A., Qureshi, R., Muneer, A., Irfan, M., Zafar, A., Shaikh, M. B., Akhtar, N., Wu, J., et al. (2024). Large language models: a comprehensive survey of its applications, challenges, limitations, and future prospects. Authorea Preprints.

- Hauser, M. D., Chomsky, N., and Fitch, W. T. (2002). The faculty of language: what is it, who has it, and how did it evolve? science, 298(5598):1569–1579.

- Horton, J. J. (2023). Large language models as simulated economic agents: What can we learn from homo silicus? Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Hu, T., Zhu, W., and Yan, Y. (2023). Artificial intelligence aspect of transportation analysis using large scale systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 6th Artificial Intelligence and Cloud Computing Conference, pages 54–59.

- Huang, A. H., Wang, H., and Yang, Y. (2023). Finbert: A large language model for extracting information from financial text. Contemporary Accounting Research, 40(2):806–841. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K., Huang, D., Liu, Z., and Mo, F. (2020a). A joint multiple criteria model in transfer learning for cross-domain chinese word segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2020 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP), pages 3873–3882.

- Huang, K., Mo, F., Li, H., Li, Y., Zhang, Y., Yi, W., Mao, Y., Liu, J., Xu, Y., Xu, J., et al. (2024). A survey on large language models with multilingualism: Recent advances and new frontiers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.10936.

- Huang, K., Xiao, K., Mo, F., Jin, B., Liu, Z., and Huang, D. (2021). Domain-aware word segmentation for chinese language: A document-level context-aware model. Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing, 21(2):1–16. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W., Abbeel, P., Pathak, D., and Mordatch, I. (2022). Language models as zero-shot planners: Extracting actionable knowledge for embodied agents. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 9118–9147. PMLR.

- Huang, Y., Song, Z., Chen, D., Li, K., and Arora, S. (2020b). Texthide: Tackling data privacy in language understanding tasks. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, pages 1368–1382.

- Kalyan, K. S. (2023). A survey of gpt-3 family large language models including chatgpt and gpt-4. Natural Language Processing Journal, page 100048. [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, N., Wallace, E., and Raffel, C. (2022). Deduplicating training data mitigates privacy risks in language models. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 10697–10707. PMLR.

- Kang, H. and Liu, X.-Y. (2023). Deficiency of large language models in finance: An empirical examination of hallucination. In I Can’t Believe It’s Not Better Workshop: Failure Modes in the Age of Foundation Models.

- Kang, Y., Xu, Y., Chen, C. P., Li, G., and Cheng, Z. (2021). 6: Simultaneous tracking, tagging and mapping for augmented reality. In SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers, volume 52, pages 31–33. Wiley Online Library.

- Kang, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhao, M., Yang, X., and Yang, X. (2022). Tie memories to e-souvenirs: Hybrid tangible ar souvenirs in the museum. In Adjunct Proceedings of the 35th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, pages 1–3.

- Khang, A., Jadhav, B., and Dave, T. (2024). Enhancing financial services. Synergy of AI and Fintech in the Digital Gig Economy, page 147.

- Kim, D., Lee, D., Park, J., Oh, S., Kwon, S., Lee, I., and Choi, D. (2022). Kb-bert: Training and application of korean pre-trained language model in financial domain. Journal of Intelligence and Information Systems, 28(2):191–206.

- orbak, T., Shi, K., Chen, A., Bhalerao, R. V., Buckley, C., Phang, J., Bowman, S. R., and Perez, E. (2023). Pretraining language models with human preferences. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 17506–17533. PMLR.

- Krause, D. (2023). Large language models and generative ai in finance: an analysis of chatgpt, bard, and bing ai. Bard, and Bing AI (July 15, 2023).

- Krumdick, M., Koncel-Kedziorski, R., Lai, V., Reddy, V., Lovering, C., and Tanner, C. (2024). Bizbench: A quantitative reasoning benchmark for business and finance. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 8309–8332.

- Li, H., Gao, H., Wu, C., and Vasarhelyi, M. A. (2023a). Extracting financial data from unstructured sources: Leveraging large language models. Journal of Information Systems, pages 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Zhang, Y., and Chen, L. (2021). Personalized transformer for explainable recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.11601.

- Li, S., Puig, X., Paxton, C., Du, Y., Wang, C., Fan, L., Chen, T., Huang, D.-A., Akyürek, E., Anandkumar, A., et al. (2022). Pre-trained language models for interactive decision-making. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35:31199–31212.

- Li, X. V. and Passino, F. S. (2024). Findkg: Dynamic knowledge graphs with large language models for detecting global trends in financial markets. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.10909.

- Li, Y., Wang, S., Ding, H., and Chen, H. (2023b). Large language models in finance: A survey. In Proceedings of the fourth ACM international conference on AI in finance, pages 374–382.

- Li, Z., Guan, B., Wei, Y., Zhou, Y., Zhang, J., and Xu, J. (2024). Mapping new realities: Ground truth image creation with pix2pix image-to-image translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.19265.

- Liang, P. P., Wu, C., Morency, L.-P., and Salakhutdinov, R. (2021). Towards understanding and mitigating social biases in language models. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 6565–6576. PMLR.

- Lieber, O., Lenz, B., Bata, H., Cohen, G., Osin, J., Dalmedigos, I., Safahi, E., Meirom, S., Belinkov, Y., Shalev-Shwartz, S., et al. (2024). Jamba: A hybrid transformer-mamba language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.19887.

- Lin, L., Wang, L., Guo, J., and Wong, K.-F. (2024). Investigating bias in llm-based bias detection: Disparities between llms and human perception. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.14896.

- Lin, Z., Akin, H., Rao, R., Hie, B., Zhu, Z., Lu, W., dos Santos Costa, A., Fazel-Zarandi, M., Sercu, T., Candido, S., et al. (2022). Language models of protein sequences at the scale of evolution enable accurate structure prediction. BioRxiv, 2022:500902.

- Liu, A., Feng, B., Wang, B., Wang, B., Liu, B., Zhao, C., Dengr, C., Ruan, C., Dai, D., Guo, D., et al. (2024). Deepseek-v2: A strong, economical, and efficient mixture-of-experts language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.04434.

- Liu, X. and Croft, W. B. (2005). Statistical language modeling for information retrieval. Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol., 39(1):1–31. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-Y., Wang, G., Yang, H., and Zha, D. (2023a). Fingpt: Democratizing internet-scale data for financial large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.10485., and Zha, D. (2023a). Fingpt: Democratizing internet-scale data for financial large language models.

- Liu, Y., Han, T., Ma, S., Zhang, J., Yang, Y., Tian, J., He, H., Li, A., He, M., Liu, Z., et al. (2023b). Summary of chatgpt-related research and perspective towards the future of large language models. Meta-Radiology, page 100017.

- Madani, A., Krause, B., Greene, E. R., Subramanian, S., Mohr, B. P., Holton, J. M., Olmos, J. L., Xiong, C., Sun, Z. Z., Socher, R., et al. (2023). Large language models generate functional protein sequences across diverse families. Nature Biotechnology, 41(8):1099–1106. [CrossRef]

- Mahowald, K., Ivanova, A. A., Blank, I. A., Kanwisher, N., Tenenbaum, J. B., and Fedorenko, E. (2024). Dissociating language and thought in large language models. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Mao, K., Deng, C., Chen, H., Mo, F., Liu, Z., Sakai, T., and Dou, Z. (2024). Chatretriever: Adapting large language models for generalized and robust conversational dense retrieval. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.13556.

- Mao, K., Dou, Z., Mo, F., Hou, J., Chen, H., and Qian, H. (2023a). Large language models know your contextual search intent: A prompting framework for conversational search. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.06573.

- Mao, K., Qian, H., Mo, F., Dou, Z., Liu, B., Cheng, X., and Cao, Z. (2023b). Learning denoised and interpretable session representation for conversational search. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, pages 3193–3202.

- Mastropaolo, A., Scalabrino, S., Cooper, N., Palacio, D. N., Poshyvanyk, D., Oliveto, R., and Bavota, G. (2021). Studying the usage of text-to-text transfer transformer to support code-related tasks. In 2021 IEEE/ACM 43rd International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), pages 336–347. IEEE.

- Meier, J., Rao, R., Verkuil, R., Liu, J., Sercu, T., and Rives, A. (2021). Language models enable zero-shot prediction of the effects of mutations on protein function. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34:29287–29303.

- Meyer, J. G., Urbanowicz, R. J., Martin, P. C., O’Connor, K., Li, R., Peng, P.-C., Bright, T. J., Tatonetti, N., Won, K. J., Gonzalez-Hernandez, G., et al. (2023). Chatgpt and large language models in academia: opportunities and challenges. BioData Mining, 16(1):20. [CrossRef]

- Min, B., Ross, H., Sulem, E., Veyseh, A. P. B., Nguyen, T. H., Sainz, O., Agirre, E., Heintz, I., and Roth, D. (2023). Recent advances in natural language processing via large pre-trained language models: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys, 56(2):1–40. [CrossRef]

- Minaee, S., Mikolov, T., Nikzad, N., Chenaghlu, M., Socher, R., Amatriain, X., and Gao, J. (2024). Large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.06196.

- Mo, F., Mao, K., Zhu, Y., Wu, Y., Huang, K., and Nie, J.-Y. (2023a). Convgqr: generative query reformulation for conversational search. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.15645.

- Mo, F., Nie, J.-Y., Huang, K., Mao, K., Zhu, Y., Li, P., and Liu, Y. (2023b). Learning to relate to previous turns in conversational search. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pages 1722–1732.

- Mo, F., Qu, C., Mao, K., Zhu, T., Su, Z., Huang, K., and Nie, J.-Y. (2024a). History-aware conversational dense retrieval. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.16659.

- Mo, F., Yi, B., Mao, K., Qu, C., Huang, K., and Nie, J.-Y. (2024b). Convsdg: Session data generation for conversational search. In Companion Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2024, pages 1634–1642.

- Muhammad, T., Aftab, A. B., Ibrahim, M., Ahsan, M. M., Muhu, M. M., Khan, S. I., and Alam, M. S. (2023). Transformer-based deep learning model for stock price prediction: A case study on bangladesh stock market. International Journal of Computational Intelligence and Applications, 22(03):2350013. [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M., Carlini, N., Hayase, J., Jagielski, M., Cooper, A. F., Ippolito, D., Choquette-Choo, C. A., Wallace, E., Tramèr, F., and Lee, K. (2023). Scalable extraction of training data from (production) language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.17035.

- Naveed, H., Khan, A. U., Qiu, S., Saqib, M., Anwar, S., Usman, M., Akhtar, N., Barnes, N., and Mian, A. (2023). A comprehensive overview of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.06435.

- Navigli, R., Conia, S., and Ross, B. (2023). Biases in large language models: origins, inventory, and discussion. ACM Journal of Data and Information Quality, 15(2):1–21.

- Ni, H., Meng, S., Chen, X., Zhao, Z., Chen, A., Li, P., Zhang, S., Yin, Q., Wang, Y., and Chan, Y. (2024a). Harnessing earnings reports for stock predictions: A qlora-enhanced llm approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.06634.

- Ni, H., Meng, S., Geng, X., Li, P., Li, Z., Chen, X., Wang, X., and Zhang, S. (2024b). Time series modeling for heart rate prediction: From arima to transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.12199.

- Noor, A. K., Burton, W. S., and Bert, C. W. (1996). Computational models for sandwich panels and shells. [CrossRef]

- Obschonka, M. and Audretsch, D. B. (2020). Artificial intelligence and big data in entrepreneurship: a new era has begun. Small Business Economics, 55:529–539. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI (2023). Gpt-3.5 turbo fine-tuning and api updates. https://openai.com/index/gpt-3-5-turbo-fine-tuning-and-api-updates/. Accessed: 2024-05-20.

- Pan, X., Zhang, M., Ji, S., and Yang, M. (2020). Privacy risks of general-purpose language models. In 2020 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), pages 1314–1331. IEEE.

- Park, T. (2024). Enhancing anomaly detection in financial markets with an llm-based multi-agent framework. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.19735.

- Peng, C., Yang, X., Chen, A., Smith, K. E., PourNejatian, N., Costa, A. B., Martin, C., Flores, M. G., Zhang, Y., Magoc, T., et al. (2023). A study of generative large language model for medical research and healthcare. NPJ digital medicine, 6(1):210. [CrossRef]

- Peris, C., Dupuy, C., Majmudar, J., Parikh, R., Smaili, S., Zemel, R., and Gupta, R. (2023). Privacy in the time of language models. In Proceedings of the sixteenth ACM international conference on web search and data mining, pages 1291–1292.

- Petroni, F., Rocktäschel, T., Lewis, P., Bakhtin, A., Wu, Y., Miller, A. H., and Riedel, S. (2019). Language models as knowledge bases? arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.01066.

- Pinker, S. (2003). The language instinct: How the mind creates language. Penguin uK.

- Raeini, M. (2023). Privacy-preserving large language models (ppllms). Available at SSRN 4512071.

- Rafailov, R., Sharma, A., Mitchell, E., Manning, C. D., Ermon, S., and Finn, C. (2024). Direct preference optimization: Your language model is secretly a reward model. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36.

- Raffel, C., Shazeer, N., Roberts, A., Lee, K., Narang, S., Matena, M., Zhou, Y., Li, W., and Liu, P. J. (2020). Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. Journal of machine learning research, 21(140):1–6.

- Rao, A., Kim, J., Kamineni, M., Pang, M., Lie, W., and Succi, M. D. (2023). Evaluating chatgpt as an adjunct for radiologic decision-making. MedRxiv, pages 2023–02.

- Renze, M. and Guven, E. (2024). Self-reflection in llm agents: Effects on problem-solving performance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.06682.

- Robles-Serrano, S., Rios-Perez, J., and Sanchez-Torres, G. (2024). Integration of large language models in mobile applications for statutory auditing and finance. Prospectiva (1692-8261), 22(1).

- Rosenfeld, R. (2000). Two decades of statistical language modeling: Where do we go from here? Proceedings of the IEEE, 88(8):1270–1278.

- Rubinstein, I. S. and Good, N. (2013). Privacy by design: A counterfactual analysis of google and facebook privacy incidents. Berkeley Tech. LJ, 28:1333.

- alemi, A., Mysore, S., Bendersky, M., and Zamani, H. (2023). Lamp: When large language models meet personalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.11406.

- Sha, H., Mu, Y., Jiang, Y., Chen, L., Xu, C., Luo, P., Li, S. E., Tomizuka, M., Zhan, W., and Ding, M. (2023). Languagempc: Large language models as decision makers for autonomous driving. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.03026.

- Shen, Y., Heacock, L., Elias, J., Hentel, K. D., Reig, B., Shih, G., and Moy, L. (2023). Chatgpt and other large language models are double-edged swords. [CrossRef]

- Shi, W., Ajith, A., Xia, M., Huang, Y., Liu, D., Blevins, T., Chen, D., and Zettlemoyer, L. (2023). Detecting pretraining data from large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.16789.

- Shi, W., Cui, A., Li, E., Jia, R., and Yu, Z. (2021). Selective differential privacy for language modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.12944.

- Shoeybi, M., Patwary, M., Puri, R., LeGresley, P., Casper, J., and Catanzaro, B. (2019). Megatron-lm: Training multi-billion parameter language models using model parallelism. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.08053.

- Sommestad, T., Ekstedt, M., and Holm, H. (2012). The cyber security modeling language: A tool for assessing the vulnerability of enterprise system architectures. IEEE Systems Journal, 7(3):363–373. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. (2019). Deep Learning Applications in the Medical Image Recognition. American Journal of Computer Science and Technology, 2(2):22–26.

- Song, Y., Arora, P., Singh, R., Varadharajan, S. T., Haynes, M., and Starner, T. (2023). Going Blank Comfortably: Positioning Monocular Head-Worn Displays When They are Inactive. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Symposium on Wearable Computers, pages 114–118, Cancun, Quintana Roo Mexico. ACM.

- Song, Y., Arora, P., Varadharajan, S. T., Singh, R., Haynes, M., and Starner, T. (2024). Looking From a Different Angle: Placing Head-Worn Displays Near the Nose. In Proceedings of the Augmented Humans International Conference 2024, pages 28–45, Melbourne VIC Australia. ACM.

- Stolcke, A. et al. (2002). Srilm-an extensible language modeling toolkit. In Interspeech, volume 2002, page 2002.

- Su, Z., Zhou, Y., Mo, F., and Simonsen, J. G. (2024). Language modeling using tensor trains. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.04590.

- Sun, Y., Dong, L., Huang, S., Ma, S., Xia, Y., Xue, J., Wang, J., and Wei, F. (2023). Retentive network: A successor to transformer for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.08621.

- Tang, X., Lei, N., Dong, M., and Ma, D. (2022). Stock price prediction based on natural language processing1. Complexity, 2022(1):9031900.

- Thede, S. M. and Harper, M. (1999). A second-order hidden markov model for part-of-speech tagging. In Proceedings of the 37th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 175–182.

- Thirunavukarasu, A. J., Ting, D. S. J., Elangovan, K., Gutierrez, L., Tan, T. F., and Ting, D. S. W. (2023). Large language models in medicine. Nature medicine, 29(8):1930–1940. [CrossRef]

- Turing, A. M. (2009). Computing machinery and intelligence. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Voigt, P. and Von dem Bussche, A. (2017). The eu general data protection regulation (gdpr). A Practical Guide, 1st Ed., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 10(3152676):10–5555. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Li, M., and Smola, A. J. (2019). Language models with transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.09408.

- Wang, J., Mo, F., Ma, W., Sun, P., Zhang, M., and Nie, J.-Y. (2024a). A user-centric benchmark for evaluating large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.13940.

- Wang, L., Ma, C., Feng, X., Zhang, Z., Yang, H., Zhang, J., Chen, Z., Tang, J., Chen, X., Lin, Y., et al. (2024b). A survey on large language model based autonomous agents. Frontiers of Computer Science, 18(6):186345. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Zhang, S., Mammadov, M., Li, K., Zhang, X., and Wu, S. (2022a). Semi-supervised weighting for averaged one-dependence estimators. Applied Intelligence, pages 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Zhang, X., Li, K., and Zhang, S. (2022b). Semi-supervised learning for k-dependence bayesian classifiers. Applied Intelligence, pages 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., Fu, Y., Zhou, Y., Liu, K., Li, X., and Hua, K. A. (2020). Exploiting mutual information for substructure-aware graph representation learning. In IJCAI, pages 3415–3421.

- Wang, Y., Zhong, W., Li, L., Mi, F., Zeng, X., Huang, W., Shang, L., Jiang, X., and Liu, Q. (2023). Aligning large language models with human: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.12966.

- Wang, Z., Wang, P., Liu, K., Wang, P., Fu, Y., Lu, C.-T., Aggarwal, C. C., Pei, J., and Zhou, Y. (2024c). A comprehensive survey on data augmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.09591.

- Weber, M., Beutter, M., Weking, J., Böhm, M., and Krcmar, H. (2022). Ai startup business models: Key characteristics and directions for entrepreneurship research. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 64(1):91–109.

- Wendlinger, B. (2022). The challenge of FinTech from the perspective of german incumbent banks: an exploratory study investigating industry trends and considering the future of banking. PhD thesis.

- Wu, J., Antonova, R., Kan, A., Lepert, M., Zeng, A., Song, S., Bohg, J., Rusinkiewicz, S., and Funkhouser, T. (2023a). Tidybot: Personalized robot assistance with large language models. Autonomous Robots, 47(8):1087–1102. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., Zheng, Z., Qiu, Z., Wang, H., Gu, H., Shen, T., Qin, C., Zhu, C., Zhu, H., Liu, Q., et al. (2024). A survey on large language models for recommendation. World Wide Web, 27(5):60. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., Irsoy, O., Lu, S., Dabravolski, V., Dredze, M., Gehrmann, S., Kambadur, P., Rosenberg, D., and Mann, G. (2023b). Bloomberggpt: A large language model for finance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.17564.

- Xie, Q., Han, W., Zhang, X., Lai, Y., Peng, M., Lopez-Lira, A., and Huang, J. (2023). Pixiu: A large language model, instruction data and evaluation benchmark for finance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.05443.

- Xie, Q., Huang, J., Li, D., Chen, Z., Xiang, R., Xiao, M., Yu, Y., Somasundaram, V., Yang, K., Yuan, C., et al. (2024). Finnlp-agentscen-2024 shared task: Financial challenges in large language models-finllms. In Proceedings of the Eighth Financial Technology and Natural Language Processing and the 1st Agent AI for Scenario Planning, pages 119–126.

- Xing, Y., Yan, C., and Xie, C. C. (2024). Predicting nvidia’s next-day stock price: A comparative analysis of lstm, mlp, arima, and arima-garch models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.08284.

- u, Y., Hu, L., Zhao, J., Qiu, Z., Ye, Y., and Gu, H. (2024). A survey on multilingual large language models: Corpora, alignment, and bias. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.00929.

- Xue, L. (2020). mt5: A massively multilingual pre-trained text-to-text transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11934. [CrossRef]

- Yan, B., Li, K., Xu, M., Dong, Y., Zhang, Y., Ren, Z., and Cheng, X. (2024). On protecting the data privacy of large language models (llms): A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.05156.

- Yan, C. (2019). Predict lightning location and movement with atmospherical electrical field instrument. In 2019 IEEE 10th Annual Information Technology, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (IEMCON), pages 0535–0537. IEEE.

- Yan, Y. (2022). Influencing factors of housing price in new york-analysis: Based on excel multi-regression model.

- Yang, X., Kang, Y., and Yang, X. (2022). Retargeting destinations of passive props for enhancing haptic feedback in virtual reality. In 2022 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), pages 618–619. IEEE.

- Yang, Y., Uy, M. C. S., and Huang, A. (2020). Finbert: A pretrained language model for financial communications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.08097.

- Yao, S., Yu, D., Zhao, J., Shafran, I., Griffiths, T., Cao, Y., and Narasimhan, K. (2024a). Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36.

- Yao, S., Zhao, J., Yu, D., Du, N., Shafran, I., Narasimhan, K., and Cao, Y. (2022). React: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.03629.

- Yao, Y., Duan, J., Xu, K., Cai, Y., Sun, Z., and Zhang, Y. (2024b). A survey on large language model (llm) security and privacy: The good, the bad, and the ugly. High-Confidence Computing, page 100211. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y., Huang, Y., Ma, Y., Li, X., Li, Z., Shi, Y., and Zhou, H. (2024). Rhyme-aware chinese lyric generator based on gpt. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.10130.

- Zeng, J., Chen, B., Deng, Y., Chen, W., Mao, Y., and Li, J. (2024). Fine-tuning of financial large language model and application at edge device. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computer, Artificial Intelligence and Control Engineering, pages 42–47.

- Zhang, B., Yang, H., Zhou, T., Ali Babar, M., and Liu, X.-Y. (2023a). Enhancing financial sentiment analysis via retrieval augmented large language models. In Proceedings of the fourth ACM international conference on AI in finance, pages 349–356.

- Zhang, C., Liu, X., Jin, M., Zhang, Z., Li, L., Wang, Z., Hua, W., Shu, D., Zhu, S., Jin, X., et al. (2024a). When ai meets finance (stockagent): Large language model-based stock trading in simulated real-world environments. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.18957.

- Zhang, H., Hua, F., Xu, C., Kong, H., Zuo, R., and Guo, J. (2023b). Unveiling the potential of sentiment: Can large language models predict chinese stock price movements? arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.14222.

- Zhang, J., Cao, J., Chang, J., Li, X., Liu, H., and Li, Z. (2024b). Research on the application of computer vision based on deep learning in autonomous driving technology. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.00490.

- Zhang, J., Wang, X., Jin, Y., Chen, C., Zhang, X., and Liu, K. (2024c). Prototypical reward network for data-efficient rlhf. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.06606.

- Zhang, J., Wang, X., Ren, W., Jiang, L., Wang, D., and Liu, K. (2024d). Ratt: Athought structure for coherent and correct llmreasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.02746.

- Zhang, L., Wu, Y., Mo, F., Nie, J.-Y., and Agrawal, A. (2023c). Moqagpt: Zero-shot multi-modal open-domain question answering with large language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.13265.

- Zhang, S., Chen, Z., Shen, Y., Ding, M., Tenenbaum, J. B., and Gan, C. (2023d). Planning with large language models for code generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.05510.

- Zhang, S., Dong, L., Li, X., Zhang, S., Sun, X., Wang, S., Li, J., Hu, R., Zhang, T., Wu, F., et al. (2023e). Instruction tuning for large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.10792.

- Zhang, X., Wang, Z., Jiang, L., Gao, W., Wang, P., and Liu, K. (2024e). Tfwt: Tabular feature weighting with transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.08403.

- Zhang, X., Zhang, J., Mo, F., Chen, Y., and Liu, K. (2024f). Tifg: Text-informed feature generation with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.11177.

- Zhang, X., Zhang, J., Rekabdar, B., Zhou, Y., Wang, P., and Liu, K. (2024g). Dynamic and adaptive feature generation with llm. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.03505.

- Zhao, H., Chen, H., Yang, F., Liu, N., Deng, H., Cai, H., Wang, S., Yin, D., and Du, M. (2024a). Explainability for large language models: A survey. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 15(2):1–38.

- Zhao, H., Liu, Z., Wu, Z., Li, Y., Yang, T., Shu, P., Xu, S., Dai, H., Zhao, L., Mai, G., et al. (2024b). Revolutionizing finance with llms: An overview of applications and insights. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.11641.

- Zhao, P., Zhang, H., Yu, Q., Wang, Z., Geng, Y., Fu, F., Yang, L., Zhang, W., and Cui, B. (2024c). Retrieval-augmented generation for ai-generated content: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.19473.

- Zhao, W. X., Zhou, K., Li, J., Tang, T., Wang, X., Hou, Y., Min, Y., Zhang, B., Zhang, J., Dong, Z., et al. (2023). A survey of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.18223.

- Zheng, Y., Zhang, R., Huang, M., and Mao, X. (2020). A pre-training based personalized dialogue generation model with persona-sparse data. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 34, pages 9693–9700. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Zeng, Z., Chen, A., Zhou, X., Ni, H., Zhang, S., Li, P., Liu, L., Zheng, M., and Chen, X. (2024). Evaluating modern approaches in 3d scene reconstruction: Nerf vs gaussian-based methods. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.04268.

- Zhu, W. (2022). Optimizing distributed networking with big data scheduling and cloud computing. In International Conference on Cloud Computing, Internet of Things, and Computer Applications (CICA 2022), volume 12303, pages 23–28. SPIE.

- Zhu, W. and Hu, T. (2021). Twitter sentiment analysis of covid vaccines. In 2021 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality (AIVR), pages 118–122.

- Zhu, Y., Honnet, C., Kang, Y., Zhu, J., Zheng, A. J., Heinz, K., Tang, G., Musk, L., Wessely, M., and Mueller, S. (2023). Demonstration of chromocloth: Re-programmable multi-color textures through flexible and portable light source. In Adjunct Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, pages 1–3.

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).