1. Introduction

Tropical forests play a vital role in the global carbon cycle and serve as substantial carbon sinks [

1,

2,

3]. Through their dynamic exchanges of energy, water, and carbon, they shape climate patterns not only regionally but also on a global scale [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, ongoing climate change significantly impacts these land surface-atmosphere exchange processes. Rising temperatures increase the evaporative demand, which feeds back to photosynthetic activities, as indicated by net ecosystem exchange (NEE) [

5,

6]. Previous research by [

1,

7,

8] has focused on the carbon annual budgets of tropical rainforests. While these studies provide valuable insights into carbon fluxes, they did not specifically address the complexities introduced by heterogeneous terrain. Their findings emphasize the need for dedicated studies that consider the influence of topography on ecosystem carbon dynamics. The tropical mountain rain forest in the Andes Mountains of southern Ecuador represents a unique and biodiverse ecosystem that has received comparatively little attention regarding exchange processes at the ecosystem – atmosphere interface, although they are critical for the global carbon storage [

9]. As described by previous studies the area is highly endangered by deforestation [

10,

11] as well as climate change [

12] which impact the exchange of energy, water and carbon. Thus, knowledge on land surface- atmosphere interactions encompassing NEE and the surface energy balance (SEB) play an important role to understand modifications due to global changes.

A commonly used and worldwide accepted approach to directly observe atmospheric carbon and water fluxes is the eddy covariance (EC) measurement technique [

13,

14]. EC is based on the high-frequency (10-20Hz) measurements of the vertical wind speed and CO

2 / H

2O concentrations above plant canopies (turbulent eddy flux) coupled to measurements of CO

2 storage below the measurement point using slow response infrared gas analyzers [

14]. Applying this technique requires extensive quality checks to ensure the accuracy of the measurements across different surfaces [

15]. At the same time, certain conditions such as homogeneous and flat surfaces facilitates the estimation and quantification of the fluxes [

13,

16]. In order to guarantee the quality of the data, quality assessment and control is mandatory especially in non-ideal environments such as the mountainous landscape of the Andes. One of the primary challenges associated with EC measurements in complex terrains is the occurrence of stable atmospheric conditions, particularly at night during nocturnal boundary layer (NBL) development. The atmosphere can evolve a thermally stable stratification, which strongly affects turbulent exchanges and a modified turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) [

17,

18]. This may lead to an accumulation of CO

2 near the surface causing an underestimation of nighttime ecosystem respiration as a result of a reduced or intermittent TKE [

13,

14]. In contrast, a decoupling between the NBL and the air masses aloft can induce an overestimation of particle quantities due to a break-up of the NBL. The result is an energy imbalance reported by various studies [

19,

20,

21]. Further, in tropical rainforests, the often-dense canopy structure significantly limits the amount of solar radiation that reaches the forest surface. Consequences of the reduction in ground-level radiation can be a modified SEB reflected in the energy balance closure (EBC), which is a critical validation step for EC measurements. As shown by [

22,

23] an EBC in an acceptable range is also relevant in the interpretation of the atmospheric H

2O and CO

2 fluxes. However, uncertainties in association to EBC frequently occurs. [

20,

23] showed that in complex areas residuals can reach up to 35%. Additionally, the footprint area of the fluxes can become more variable, due to the heterogeneous surface characteristics inducing upslope and downslope flows in the diurnal cycle, which is frequently evolving [

24], especially in our study site, [

13,

14]. Further, forest ecosystems can impose a storage effect between the level of flux measurements above canopy and the surface due to the understory. [

25,

26] investigated the heat storage effect in a mid-latitude forest ecosystems and its effect on the EBC. They found a total heat storage varying between -35 and +45 W/m². This heat storage can create biases in land surface modelling. [

27] showed that biases in sensible and latent fluxes are related to the lack of heat storage in vegetation biomass using the Community Land Model version 5. [

28] also reported on the improvement of the modelling results under the consideration of the heat storage effect of forest ecosystems. Thus, estimation of uncertainties in EC measurements is crucial and needs a careful consideration as they are also relevant for coupled atmosphere ecosystem modelling.

However, several studies over the past decade have also successfully utilized EC measurements in complex terrain or non-ideal condition [

23,

29,

30]. For the European alpine region [

31] have employed these techniques to manage turbulent advection and account for sloping terrain effects. While these corrections and approaches can help to reduce uncertainties in the measurements, the studies also highlight that achieving accurate and closed energy balance in complex terrain remains a significant challenge for the EC method. [

3,

32,

33,

34] amongst others have specifically tackled the challenges posed by complex terrain in tropical ecosystems. [

32,

34] observed dependence of u* on the daytime EBC and demonstrated that the EBC was highly related on the thermodynamic stability of the lower atmosphere. In dry tropical forests, [

31] have successfully used EC measurements In which based on the TKE the authors used dimensionless turbulence filters and corrected radiation measurements to address these challenges.

In order to get a better understanding of the energy and carbon exchange in tropical mountain rainforest ecosystems and the response to recent and future climate changes reflected in coupled atmosphere ecosystem modelling observations are highly needed. Therefore, the main objective of this study is the analyses of the influence of the terrain complexity and vegetation height on the turbulent exchange of momentum, energy and carbon using EC measurements above a tropical forest canopy. The aims are to (i) analyze the wind field to assess the advection and turbulent activities, (ii) examine the EBC to estimate the quality of the EC measurements, quantify the imbalance of the heat fluxes and the storage effect of the forest vegetation and (iii) explore on the quality of the carbon fluxes by analyzing NEE in the diurnal and annual cycle. The accuracy of the measured energy and carbon fluxes is highly important for a subsequent partitioning of NEE

3. Results

3.1. Wind Field

Mountainous regions are highly dominated by slope winds developed in the diurnal cycle and affecting the planetary boundary layer (PBL). Because of the location of the EC system, we start our analyses by looking particularly at this mechanism and its impact on the turbulent fluxes.

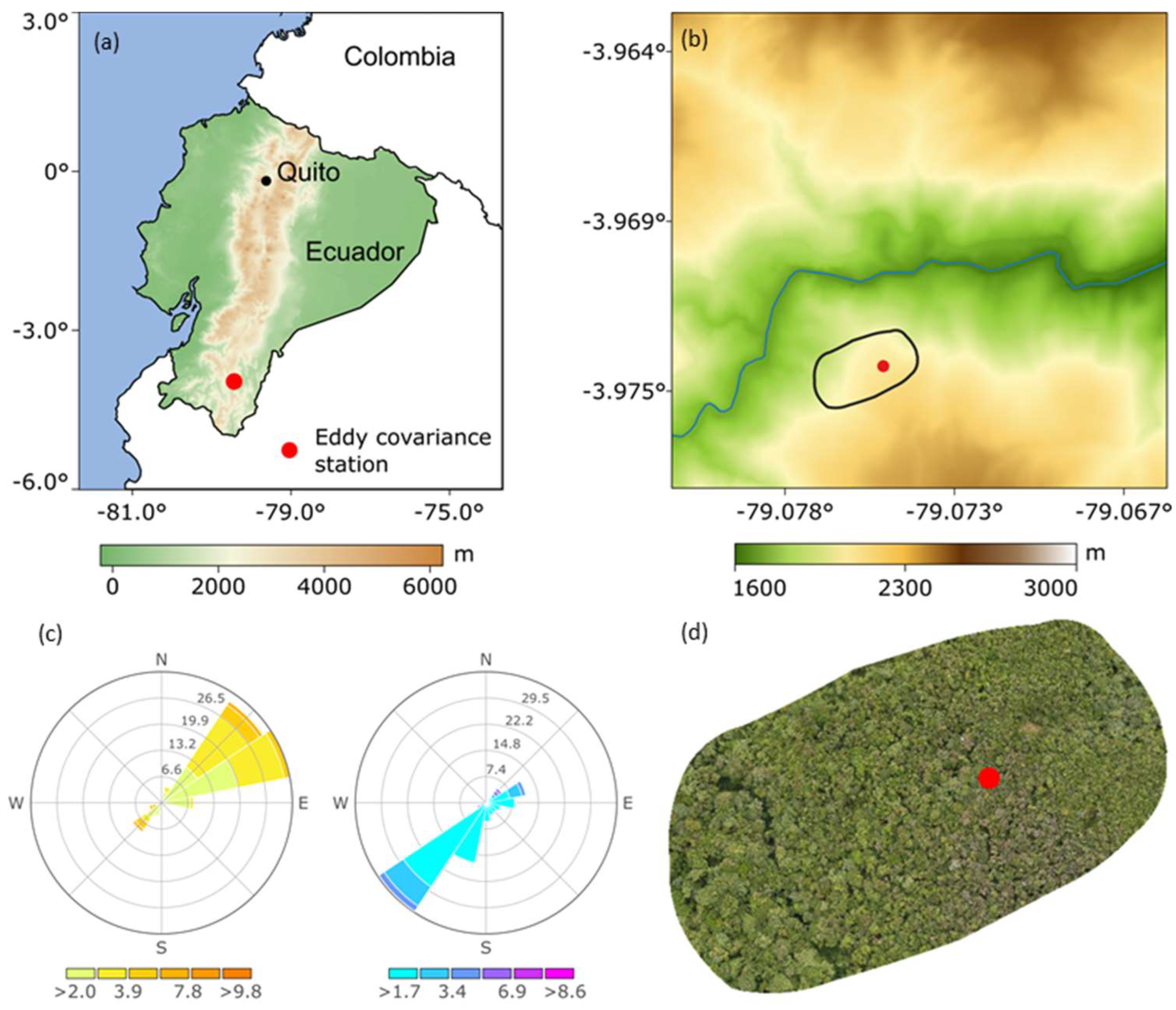

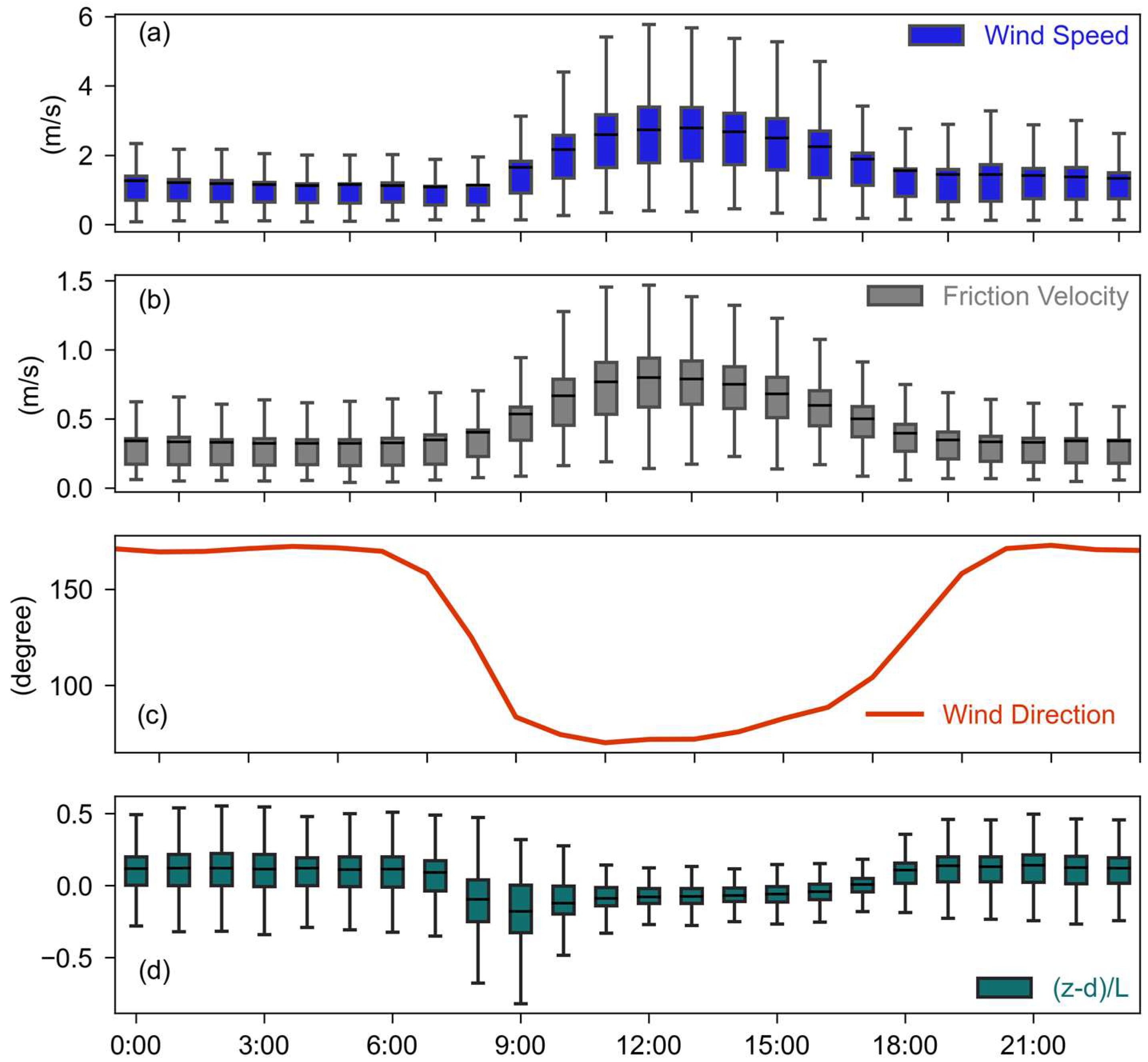

Figure 2 shows the wind field (speed and direction), u* and the Monin-Obukhov stability parameter ((z-d)/L).

Generally, a clear diurnal cycle can be observed for each variable illustrated, which points to the occurrence of changing wind fields in the diel. Wind direction is rapidly changing especially in the transition between daytime and nighttime hours. While from 9:00 – 17:00 the northeastern direction (35 – 65 degree) dominates representing up-valley flows, it is changed to a southeastern direction (155 – 175 degree) from 18:00 – 7:00 indicating down-valley flows. The slope valley winds tend to be stronger during late morning and afternoon hours as the irradiance creates the stronger gradients. This is reflected in the wind speed and u* as well. They feature the highest (lowest) values from 9:00 - 17:00 (7:00 - 8:00) associated with the strongest (weakest) variability. During daytime wind speed ranges from 4 - 6 m/s while during night time it declines down to 2.5 m/s. The maximum wind speed of 9 m/s is observed at 12:00 with a corresponding strong u* of 2.10 m/s creating strong turbulent mixing. The situation is changed during nighttime, when calm conditions predominate and mixing is weakened as indicated by u* varying between 0.1 - 0.75 m/s. Further, the variability of both, wind speed and u*, is distinctly reduced during nighttime hours.

The Monin-Obukhov stability parameter ((z-d)/L), confirms the variations in the turbulence activities from the surface to the canopy in the diurnal cycle. The lower atmosphere is mostly turbulent during the late morning period (08:00- 09:00) as indicated by the strongest negative values ranging from -0.2 to 0.2. This is the hour of day, when wind direction is changing and speed is increasing, resulting in the development of the PBL neutral and unstable conditions (values ≤ 0) during daytime. The atmospheric stratification is modified to stable conditions (values > 0) at nighttime with mostly positive values. Fluctuations towards negative values can also be observed due to down valley winds which induces turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) within the NBL [

17,

18].

3.2. Vertical Heat and Moisture Effects

As well known, forest ecosystems evolve a storage effect due to differences in the vertical energy transportation within the understory and at the canopy [

51,

52]. Storage effects within the canopy related to air temperature and relative humidity involves the retention and exchange of heat and moisture within the canopy and surface layers, which feedback to the ecosystem's energy balance. In terms of the rate of CO

2 fluxes, it is determined by the difference in the instantaneous profiles of concentrations at the beginning and end of the 30-minute EC averaging period, divided by the averaging period itself [

51,

53]. During nighttime, when the atmosphere is stable stratified and turbulence is weak, the storage effect becomes important as it may exceed the CO

2 fluxes. For this, as mentioned above we installed 4 low-budget sensors at different height levels within the canopy to estimate a storage capacity concerning air temperature and relative humidity profiles.

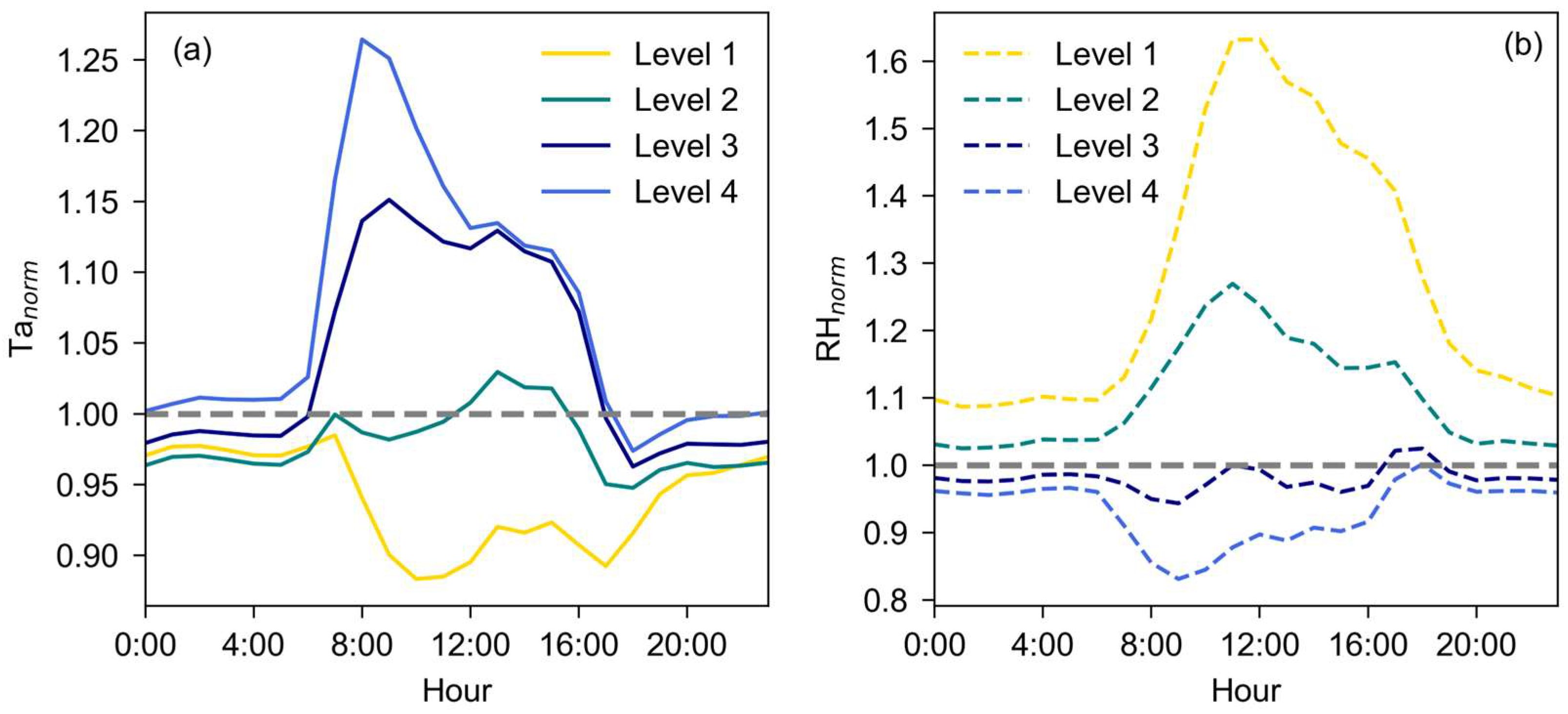

Figure 3 illustrates the storage capacity for heat and moisture calculated based on equation 2. Normalized values > 1 (< 1) indicate higher (lower) values than above the canopy at EC measurement level (z

c), while 1 represents equal values. This means, unstable, stable and neutral stratifications, respectively, can be derived. Generally, the strongest temperature deviations are developed during daytime while the nighttime hours oscillate around 1

Figure 3 (a). With exception of level 1 warmer Ta occur during daytime, particularly for level 3 and 4. Here, higher values than above the canopy between 15% (1.15) and 25% (1.25) are, rapidly develop in the morning hours and remain over the day. The lowest level (1 m agl) in contrast shows below-reference values down to 10% (0.9), which indicates cooling effects near the ground. Height level 2 fluctuates around 1 throughout the day with highest values in the afternoon (13:00 – 16:00) and lowest values around early evening (17:00 – 18:00). RH, illustrates the opposite behavior with highest deviations from reference in 1m (> 60%) around noon

Figure 3 (b), which represents an accumulation of moisture near ground. Level 3 and 4 on the other hand are close to 1 and below the reference, which points to drier conditions than above the canopy.

3.3. Energy Balance Closure

One of the greatest challenges of EC measurements, particularly in sloped and heterogeneous terrain, is the EBC as described by various authors [

24,

34,

54]. However, it offers a possibility to validate EC measurements by the sum of LE and H against the difference between net radiation (Rn) and ground heat flux (G) through linear regression analysis [

14,

55]. It is defined as

with ε as residual flux representing the imbalance.

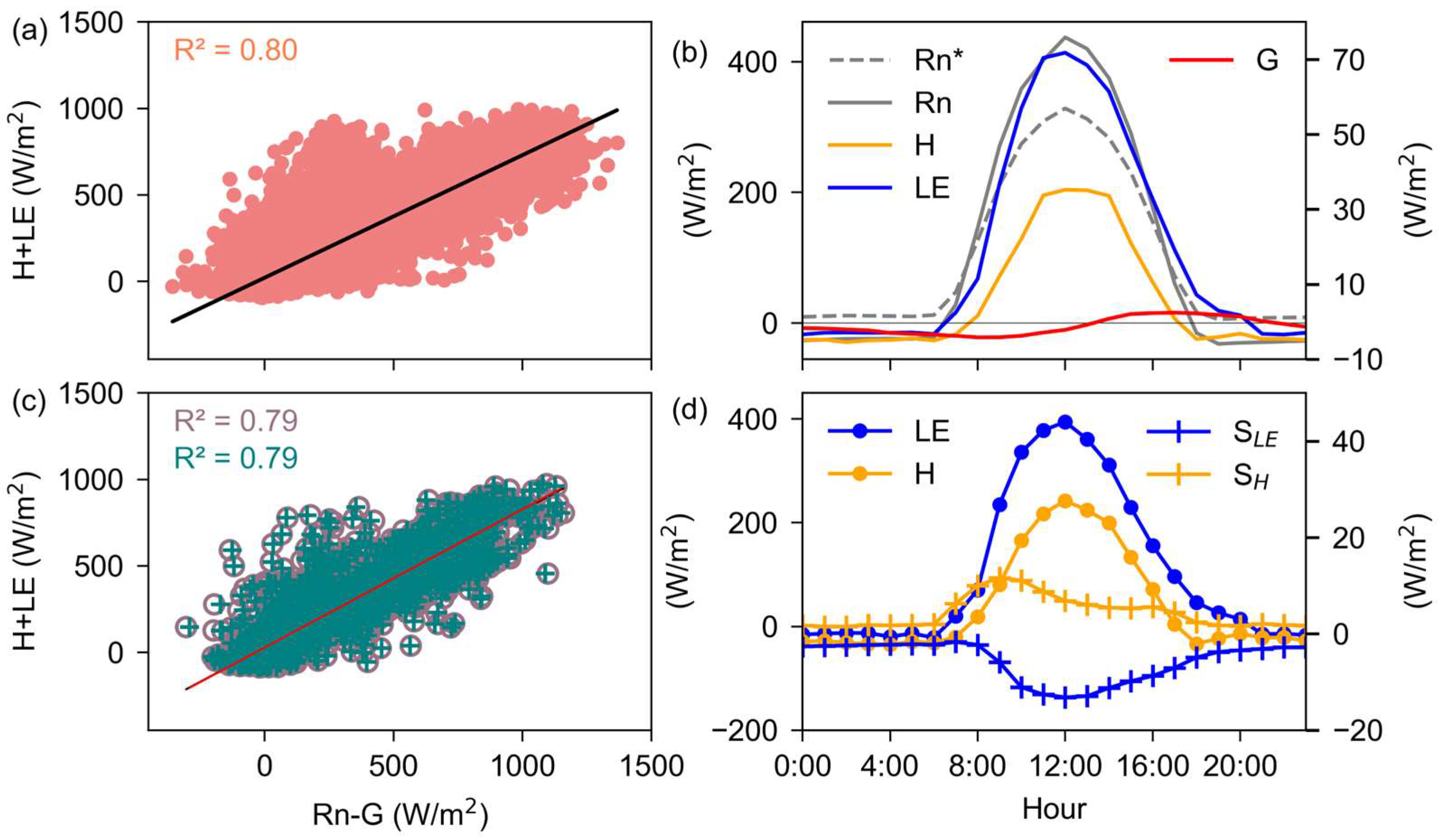

Figure 4a shows the EBC with an explained variance of R² = 0.795, which characterizes a good closure and is in the range of uncertainty in complex terrain [

22]. In order to explore on the behavior of the energy fluxes

Figure 4 (b) shows the mean diurnal cycle of H and LE, in which also, Rn and the corrected net radiation (Rn*) are examined. As expected, the energy fluxes resemble a strong diurnal cycle with a peak around noon and a decline at night. LE is the strongest contributor to the energy exchange at our site with a mean maximum of 400 W/m², while H reaches 200 W/m². Interestingly, G reveals a lag in its peak phase for both, daytime and nighttime hours.

To reduce uncertainties in the EBC we corrected Rn as described by [

23,

30,

31]. Comparisons between Rn and Rn* illustrate that the corrections applied clearly affect the magnitude of the radiation budget (

Figure 4b). While Rn reaches a maximum of 450 W/m² during daytime Rn* exhibited a reduced magnitude (320 W/m²). For nighttime this behavior is changed and Rn features a stronger radiation loss than Rn*. The most significant modifications are occurring in the morning hours as well as during daytime. Although both Rn and Rn* peaked at noon, the latter resembled a more smoothed pattern. Despite these adjustments, the overall improvement in EBC was only marginal as indicated by R² = 0.795 (Rn) in comparison to R² = 0.794 (Rn*). Since the magnitude of Rn* was consistently lower than LE, as well as that the accuracy of the EBC has not been improved significantly, the uncorrected values are used in the ongoing analyses.

Considering the storage effect on heat (S

H) and moisture (S

LE) exchange the EBC and diurnal cycle of LE and H are additionally included for the time period October 2022 – December 2022 (

Figure 4c, d). When the storage is added an improvement of the EBC from R²=0.786 to 0.789 and a root mean square error (RMSE) from 121.37 to 120.37 is achieved (

Table 2). Although the effect is only marginal, especially the diurnal cycle reveals important insight into systematic patterns.

Table 3 summarizes the mean and integrated storage effect related to the mean diurnal cycle as well as to daytime, nighttime and transition hours as defined in (

Table 1). In total on a daily basis S

H and S

LE accounts for 4.4 and -5.6 W/m², respectively. When we take a look at the hours of day, it can be observed that H generates an overestimation of heat (S

H) of more than 10 W/m², especially from 8:00 - 10:00, with a subsequent decline from noon down to 5.5 W/m², when mixing is strongest. For LE an underestimation occurs as indicated by the negative values of S

LE. It reaches its lowest values from 10:00 – 14:00 with around -12 W/m². As an integral value S

H and S

LE account for 105.2 and -133.7 W/m², respectively, 55% and 40% of which is generated in the transition hours.

3.4. Energy Balance Closure as a Function of Time

As the diurnal cycle of the storage capacity (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) revealed variations in heat and moisture on daytime (11:00 - 14:00), nighttime (20:00 – 6:00) and transition (7:00 – 10:00, 15:00 – 19:00) hours, we additionally established the EBC for these time periods.

Table 4 summarizes the linear regression coefficients as well as the R² and RMSE.

The results confirm a clear decrease in EBC during the day (R² = 0.545), while in the transition the explained variance increased to R² = 0.666. This is also reflected in the RMSE with 107.29 against 133.32 for daytime and 108.36 for the transition hours.

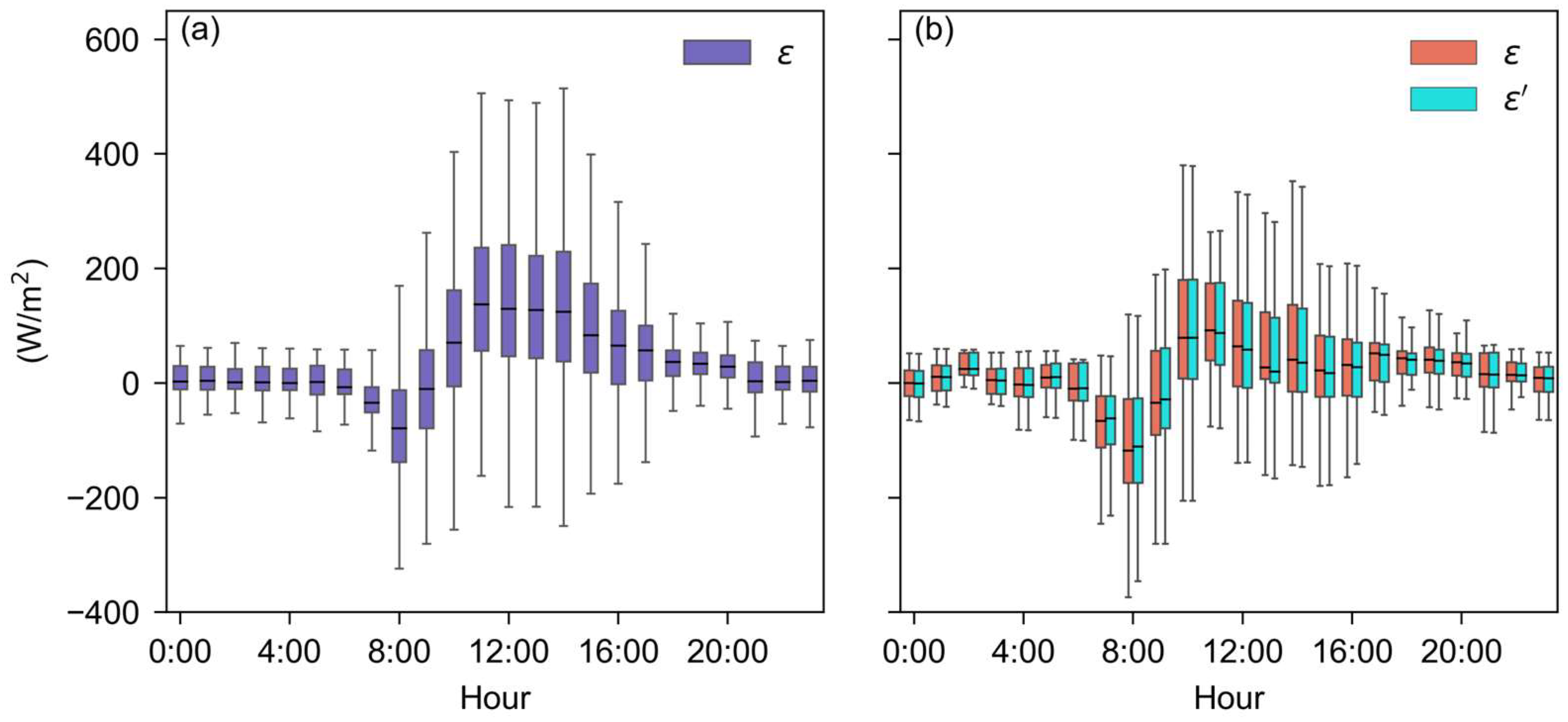

With respect to ε of the EBC differences between daytime and nighttime imbalances can be observed for both, the entire time period and the sub-period related to the storage effect (

Figure 5,

Table 3). Basically, during nighttime on average imbalances are close to zero. As the morning hours approach associated with global radiation (Rg) an underestimation of approximately 50 W/m² on average occurs. This is rapidly modified to an overestimation in the late morning hours of around 140 W/m² and peaks prior to the energy flux maxima before declining in the afternoon. Thus, variations in the EBC develop in the diurnal cycle. This is also true for the shorter time period. Comparing ε and ε’ it can be observed that the addition of the storage effect in H and LE (S

H and S

LE) reduces the imbalances. However, divided into the three time periods, it can be noted that daytime hours contribute the most to the imbalances, which accounts for 64% of the total amount (356.2 W/m²).

3.5. Energy Balance Closure and Its Relation to Thermodynamic Conditions

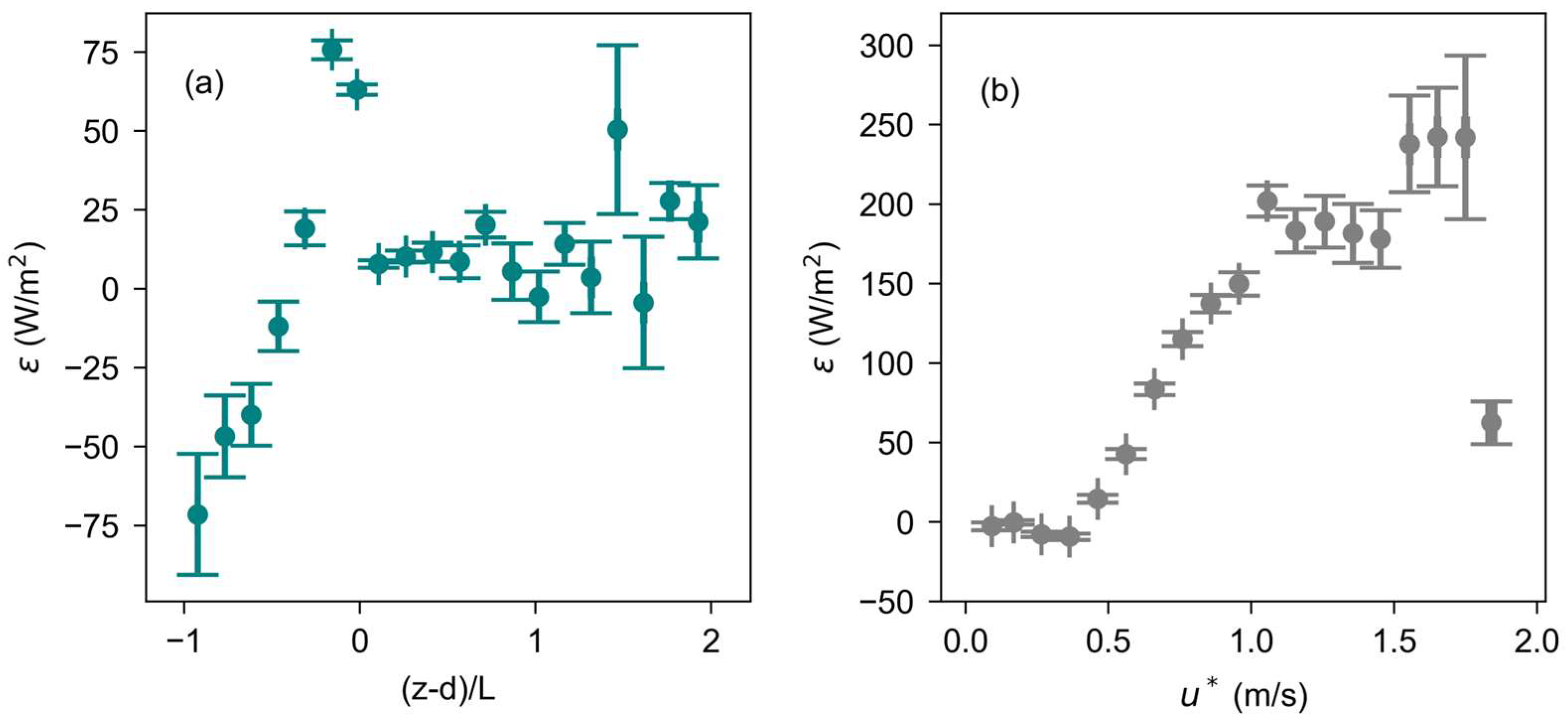

In order to shed light into the relation of imbalances to thermodynamic conditions and turbulence activities

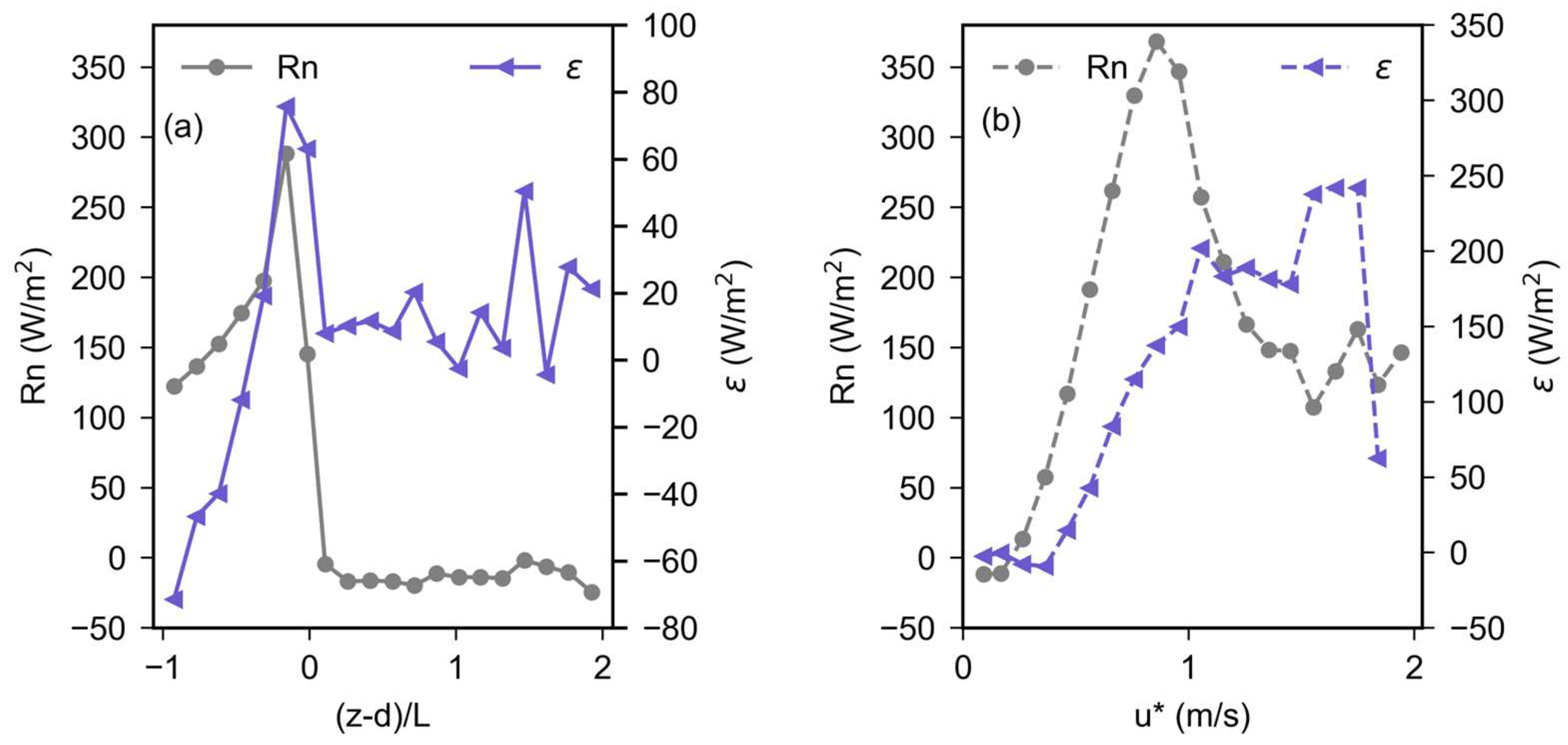

Figure 6 displays (z-d)/L and u* against ε. Since both, the residuals without and with the addition of the storage effect is comparable, the former ε is used in the ongoing analyses. The data are binned into 20 classes. As a result of averaging over each bin, but to highlight the varying signals, the y axis differs between u* and (z-d)/L.

Based on the stability parameter a clear relationship between an underestimation of the energy balance and unstable conditions can be observed as ε reaches values down to -75 W/m². In contrast, weak unstable to neutral conditions are associated with the strongest overestimation up to 75 W/m². During stable stratifications ε is close to zero, but increases towards a strong stable stratified PBL with an additional higher variability. With respect to u* weak values between 0.1 and 0.5 m/s feature small imbalances, while they increase with stronger u* values resulting in large overestimations. Reaching a u* value of more than 1.8 m/s ε decreased sharply down to 50 W/m².

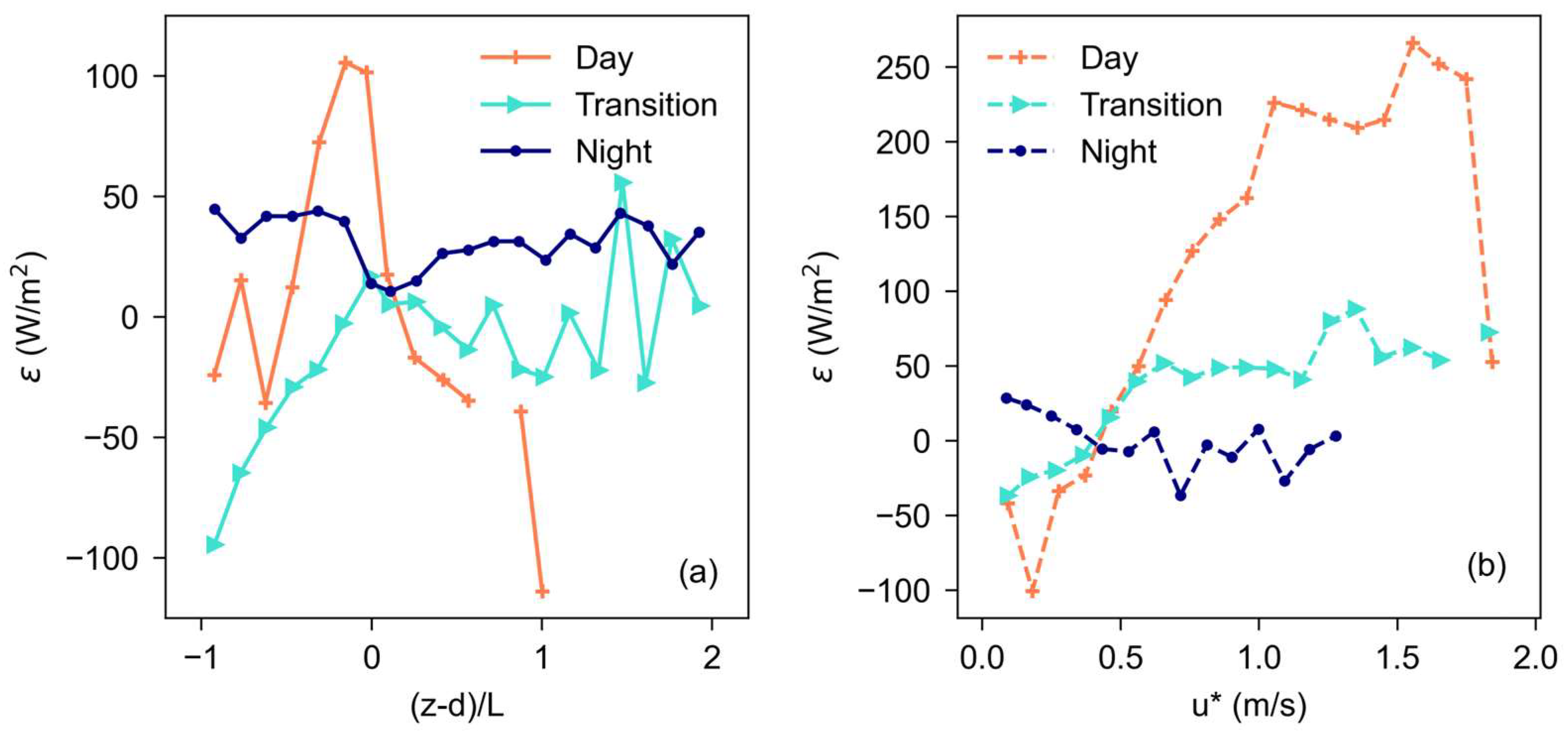

Separated into the three time periods of the day (

Table 1) and also visible in

Figure 5, variations in the amount of imbalances can be recognized.

Figure 7 illustrates that daytime imbalances vary between strongest overestimations (100 W/m²) during weak unstable to neutral conditions (-1 < (z-d)/L < 0.5) and strongest underestimations (-100 W/m²) during weak stable conditions ((z-d)/L > 1). Nighttime in contrast generates a rather small overestimation (5-50 W/m²) of the EBC independent on the stability, while the transition time reveals a clear relationship between the thermodynamic stability and ε. Imbalances as a function of u* reflects a similar behavior pointing to the turbulence activity. During daytime, when strongest mixing occurs (u* > 0.5 m/s), overestimations are largest (up to 250 W/m²), while nighttime hour represent calm conditions with the smallest ε values varying slightly between positive and negative imbalances (-30 – 20 W/m²). In the transition time, when mixing is modified imbalances change from under – to overestimation around -50 – 50 W/m².

Considering the relationship between ε and Rn as a function of (z-d)/L and u*, it can be observed that strongest overestimations of the energy balance is associated with higher irradiance. This is particularly true for the stability parameter, which reveals the peak phases for weak unstable to neutral conditions. According to u* Rn peaks with 350 W/m² between 0.5 and 1.0 m/s. Interestingly, the strongest imbalances (250 W/m²) occur during lower irradiance of around 100 W/m² representing again the transition hours of the day.

Figure 8.

Binned means of residuals (ε, W/m2) and net radiation (Rn, W/m2) as a function of (a) Monin-Obukhov stability parameter (z-d)/L and (b) friction velocity (u*, m/s).

Figure 8.

Binned means of residuals (ε, W/m2) and net radiation (Rn, W/m2) as a function of (a) Monin-Obukhov stability parameter (z-d)/L and (b) friction velocity (u*, m/s).

3.6. Diurnal Cycles of CO2 Fluxes

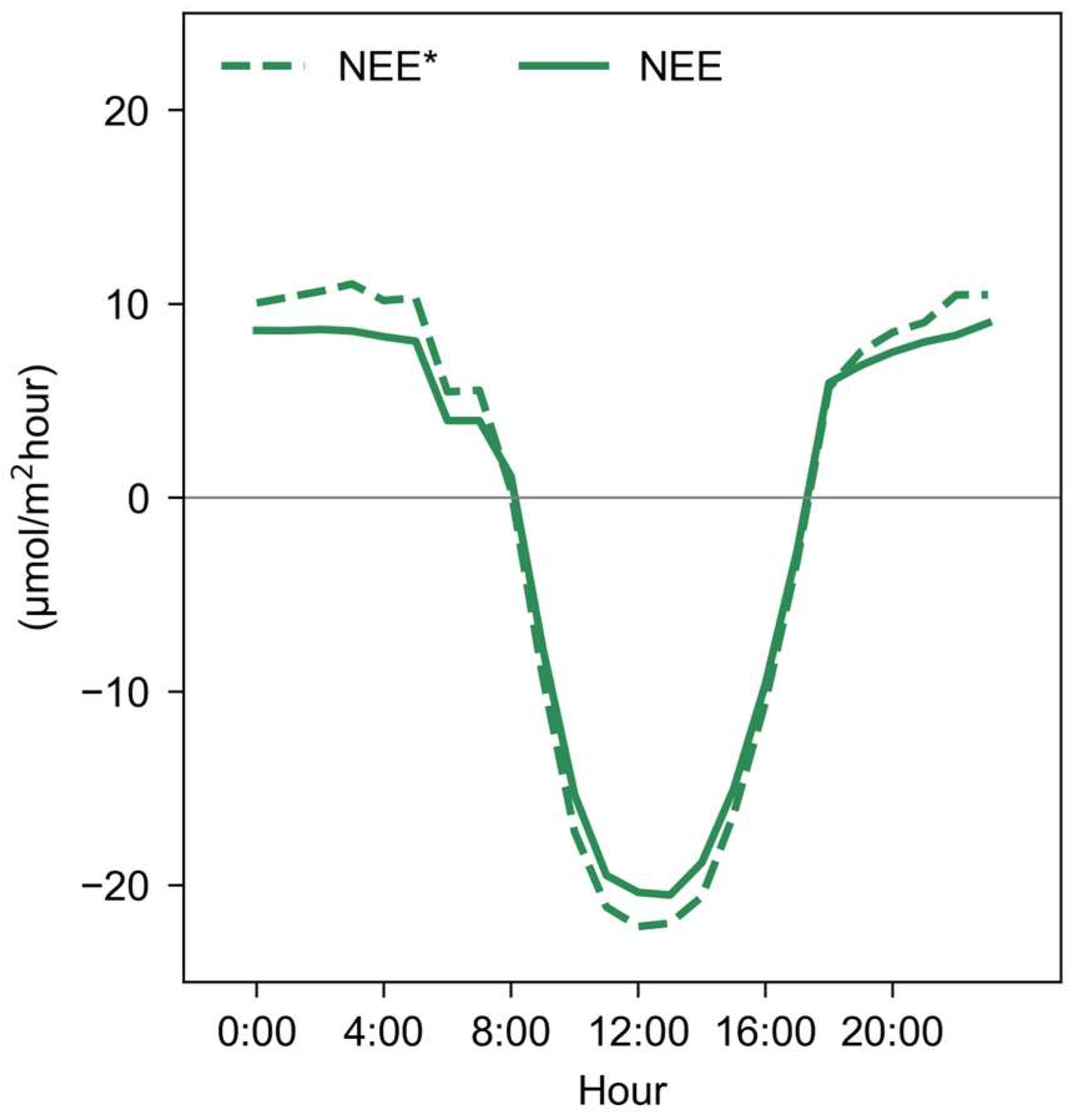

Our next step is to examine NEE estimated based on the CO2 flux measurements by the EC system. Because the data encounter similar challenges regarding the data quality as the energy fluxes, careful inspection is required as well. Thus, we explicitly analyze unfiltered NEE and filtered NEE (NEE*) to identify the impact of local wind systems and precipitation events on the carbon fluxes. The diurnal patterns of NEE and NEE* highlight the dynamic nature of CO₂ exchange within the ecosystem. Understanding these patterns is crucial for assessing the carbon balance and the role of the ecosystem.

Figure 9 shows the typical diurnal cycle of NEE and NEE* with positive values during the morning period indicating CO

2 respiration and negative values during daytime indicating the absorption of CO

2 by the canopy. The maximum absorption of CO₂ is observed between 11:00 and 12:00, with values ranging from NEE = -20 to -22 μmol/m²hour. This peak indicates the highest photosynthetic activity within the canopy during this period. A noticeable shift in NEE during the upwind period is observed between 7:00 and 8:00. During this period, maximum turbulence is seen as indicated in

Figure 2d, with NEE shifting from 0.4 to -5 μmol/m²hour. This turbulence likely enhances the mixing and thus, the transport of CO₂ within the canopy. A change in NEE from negative (-3.21 μmol/m²hour) to positive (5 μmol/m²hour) is observed during the downwind period between 17:00 and 18:00 and represents a transition from CO₂ uptake to release as the photosynthetic activity decreases and respiration becomes dominant.

With respect to the correction, difference can be detected in the magnitude of NEE. After filtering NEE reaches lower values of -1.76 μmol/m²hour for the daytime peak and -23 μmol/m²hour for the nighttime hours. The magnitude changes from NEE = -1.4 µmol/m²day to NEE* = -4.28 µmol/m²day, which was also reported by [

2]. During the stable conditions underestimation of NEE occur. Discarding this data necessarily minimizes the impact on NEE due to stable conditions [

29]. Implementing u* filtering helps to remove periods of insufficient turbulence, thereby reducing the potential bias in nocturnal flux measurements. This leads to a more accurate assessment of ecosystem respiration during nighttime. This filtering is particularly important for avoiding biases in nocturnal flux measurements and improving the overall quality and reliability of the data used in carbon budget analyses [

15,

44]. We found that the filtered data are better correlated (0.48 for NEE, 0.52 for NEE*) to light availability in terms of Rg and photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD).

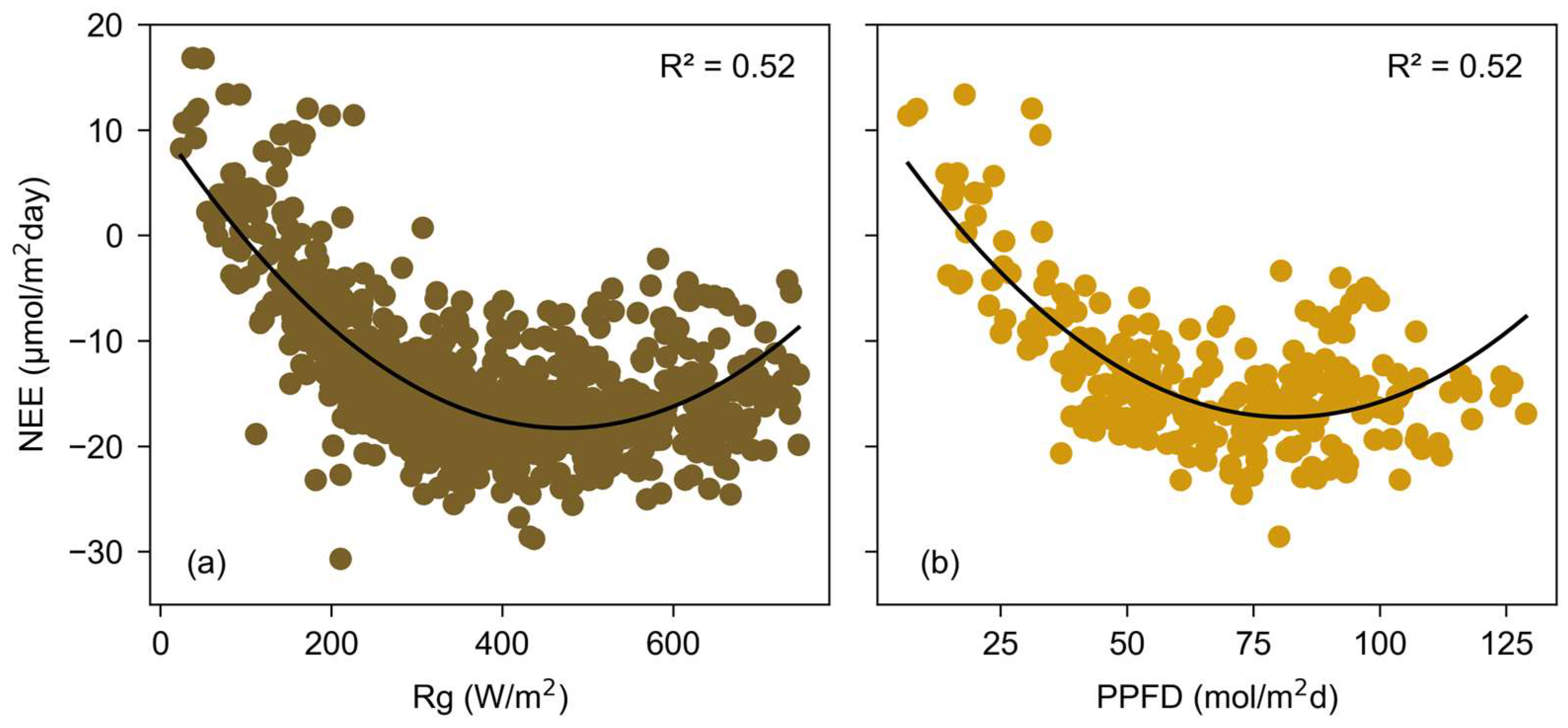

3.7. Light-Response and Carbon Exchange Model

To independently model NEE and explore on the ability to estimate carbon fluxes in such a challenging environment

Figure 10 illustrates the non-linear fit of daily NEE as a function of Rg and PPFD, respectively from 8:00 – 16:00 to ensure for a full irradiance. The latter is only available for the time period March – December 2022. The non-linear fits for both, Rg and PPFD resemble typical saturation curves with the strongest CO

2 uptake (NEE = -18 µmol/m²day) around 400 W/m² and 80 mmol/m²day, which represents the maximum uptake by the ecosystem under optimal light conditions. Since both models show a R² value of 0.52, a good performance of the carbon exchange model exists. Thus, the variance of NEE can be estimated with independent meteorological quantities, which points to a sufficient quality of the CO

2 fluxes.

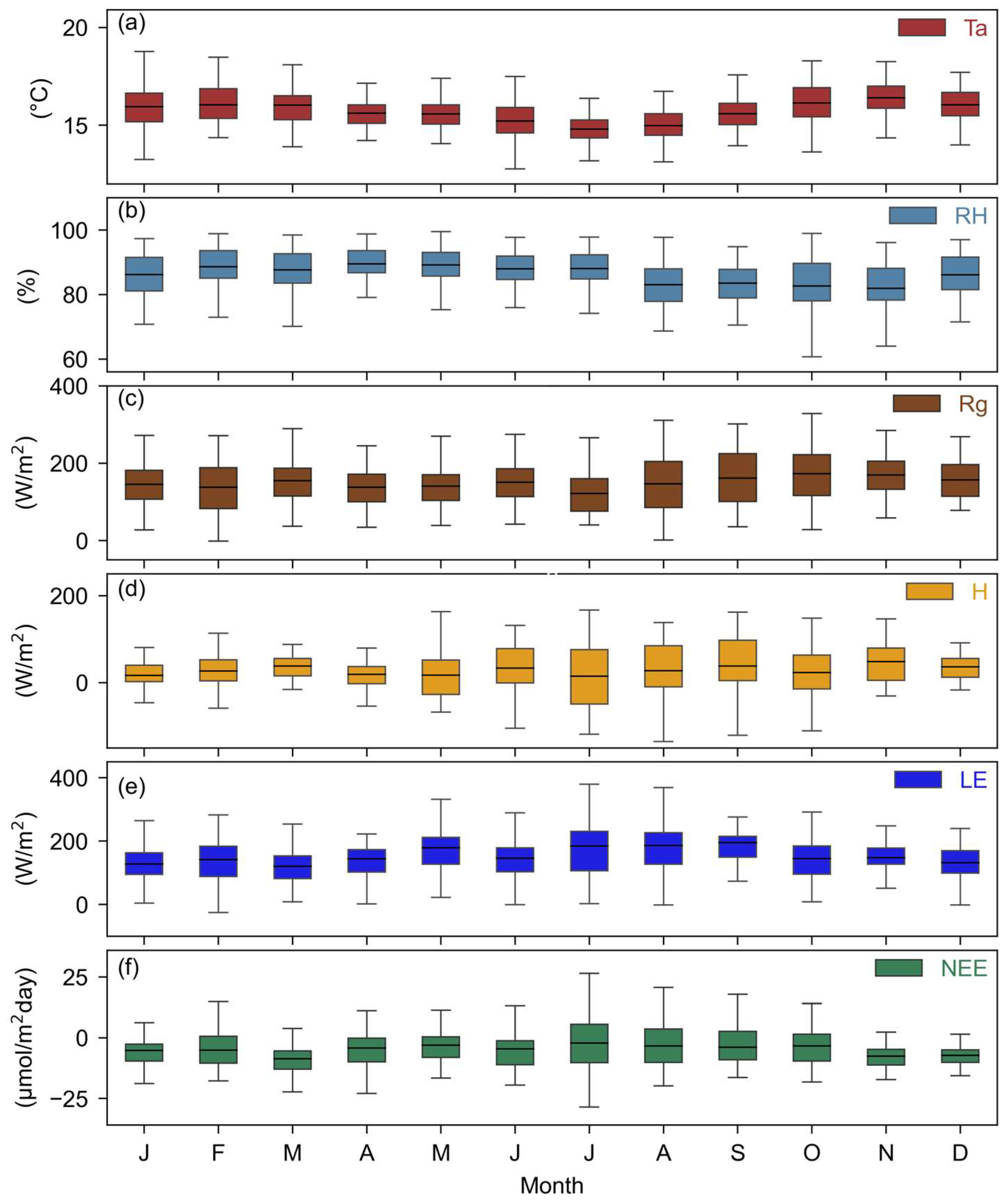

3.8. Annual Cycle of Microclimatological Conditions, Carbon and Energy Fluxes

Finally, the annual course of the meteorological quantities such as Ta and RH with energy (LE and H) and carbon (NEE) fluxes were analyzed in

Figure 11 to examine whether the fluxes resemble the microclimatological conditions. The study site is characterized by a wet period from April till June and drier conditions during September till December [

56]. This is clearly reflected in the fluxes as well.

On the annual cycle Ta varies between 12 and 20°C, whereas RH features value between 51 and 99%. Maximum distinction occurs in January for Ta (13.5 - 18°C) and for RH in October (65 - 85%). Months with drier conditions (August - October) have a higher range of Rg (260 - 310 W/m2), while during wet periods (220 - 260 W/m2) occur, most likely due to clouds. The energy (H, LE) and CO2 (NEE) fluxes reflects these micrometeorological conditions. The highest variability can be observed in July and August, where LE reaches up to 165 W/m² and H up to 43 W/m². In contrast, the lowest variability occurs in November (LE) and December (H) with a range of (142 – 137 W/m²) and (53 - 39 W/m²) respectively. The same is true for NEE with the largest range in July (-28.5 – 26.5 μmol/m²day) and the smallest December (-18 – 7.04 μmol/m²day).

4. Discussion

In this study we used energy and carbon fluxes obtained by an EC measurement system above a forest canopy in complex terrain of the tropical Andes Mountains in South Ecuador. The main focus was to investigate of the impact of the terrain as well as the vegetation height on the turbulent exchange of momentum, energy and carbon fluxes essential to quantify uncertainties in the energy balance and the heat storage effect. In such complex areas flux measurements are affected by thermally-driven wind fields in the diurnal cycle. Additionally, the EBC and its residuals were analyzed and reflected in the diurnal cycle with respect to the heat storage generated by the forest ecosystem to quantify the quality of the measurements in this challenging environment.

As expected, the study site influenced by the local wind systems which develop in the diurnal cycle (

Figure 2). This means, during daytime hours an upslope flow can be observed, while in the nighttime hours it is reversed to a downslope flow due to net radiation loss. Consequences are varying wind speeds as well as turbulence activities. The latter was confirmed by the Monin-Obukhov stability parameter ((z-d)/L). Here, it was revealed that during nighttime stable stratified atmospheric conditions dominated (values > 0), while during daytime it alternates between neutral (values = 0) and unstable stratified conditions (values < 0). However, especially the transition from nighttime to daytime showed the strongest variability with values down to -0.7. During that time of the day air masses in the downslope flow change their direction to upslope, which creates turbulent activities and a destabilization of the PBL. Advection occurred in the nighttime hours, where downslope flows led to alterations between stable and neutral conditions as indicated by u* reaching up to 1.5 m/s and (z-d)/L fluctuating from 0 to > 0.5, which was also mentioned by [

57].

The storage effect was estimated on the basis of heat and moisture profiles within the canopy as well as S

H and S

LE (

Figure 3 and 4). The normalized Ta / RH values in the diurnal cycle revealed strongest deviations from the reference level (z

c) at the highest levels in the understory (level 3 and 4) during morning hours (7:00 – 10:00). That means, during transition to daytime and incoming radiation an accumulation of heat and moisture develops, which is not mixed downward. At the same time, strongest turbulence activities above canopy were revealed, which evolves an upward mixing into the atmosphere. The lowest level on the other hand was below z

c pointing to an exchange with the soil and stable stratified conditions. From 11:00, when mixing is fully developed as indicated by the maximum of u*, wind speed and (z-d)/L differences between Ta

norm and RH

norm are reduced for level 3 and 4, but level 1 showed only weak changes. However, differences between the lower and upper levels highlight the influence of the sloped terrain as well as the vegetation height on the stratification of the air mass column and the storage capacity.

The unstable stratification and energy storage generated high EBC residuals as illustrated in

Figure 4 and 5. EBC in total showed a good performance at the study site (R² = 0.795) also described by [

20] for tropical rainforest ecosystems in complex terrain. For instance, [

31] studied a dry forest ecosystem with complex terrain and found EBC values that varied with seasonality, showing an R² ranging between 0.77 and 0.9. [

58] reported an EBC of 87% at a site with less complex terrain but evergreen forest, which is higher than the average for those sites. Similarly, for a tropical evergreen forest in China [

59] reached an EBC of 75%. These comparisons suggest that our site's EBC is within the expected range for ecosystems with similar characteristics.

Moreover, our EBC could marginally be improved for a shorter time period considering the heat storage effect of the forest which is in agreement to [

60]. The authors additionally calculated the storage effect of the biomass for individual sites, which improved the EBC more significantly. In our case, we only could consider the storage effect related to H and LE. In the diurnal cycle it could be demonstrated that S

H imposed a positive effect, i.e. accumulation of heat especially in the morning transition period, while S

LE featured an opposite pattern with a time lag towards late morning hours. Again, the storage effect predominately evolved during the transition time (40 – 55%) as already observed using the normalized Ta / RH values.

The performance of the EBC also followed the diurnal cycle. While ε was largest during daytime hours (overestimation) when strong unstable conditions lead to strong mixing, the nighttime hours were associated with stable conditions and weak turbulence generating less imbalances (

Figure 5). The transition in the morning hours was characterized by an underestimation down to -80 W/m

2 on average, when weak unstable conditions evolved. This was also shown by [

26], who pointed to stronger imbalances especially during daytime and transition, rather than nighttime hours [

34].

Reasons for the varying imbalances were demonstrated using (z-d)/L and u* (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Generally, a shift from underestimation to overestimation was observed in association with the atmospheric stratification. Very unstable condition ((z-d)/L < -1.0) were related to an energy deficit, while weak unstable and very stable conditions ((z-d)/L > 1.5) led to overestimations. The relationship between ε and u* highlighted that imbalances increase with turbulence activities. Divided into the three time periods, it can be noted that the largest imbalances (under- and overestimation) evolved during the day. With the fully developed PBL on daytime an overestimation up to 100 W/m² on average occurred as the conditions are unstable and turbulence activities are strongest (u* > 0.5 m/s). This is explained by more low frequency turbulences (i.e. larger eddies) due to the occurrence of organized convection and the development of a deeper PBL [

63]. Nighttime hours showed a weak overestimation across the stratifications. Typically, underestimations occur due to the development of the NBL and stable conditions. At our site, we could observe that fluctuations in u* values and (z-d)/L appear, which induced mixing contrary to the expected calm conditions [

61]. Further, the micrometeorological conditions differ within and above the canopy . This may lead to diabatic flows controlled by changes in air density and the slope [

51], which localizes the source area for the storage flux. Thus, influence of down-valley winds affecting the stability conditions particularly at nighttime exists. Interestingly, the transition time oscillated from underestimation during very unstable to overestimation during stable conditions. The latter occurred due to advection above and within the forest canopy air space which was also observed by [

23]. However, nighttime hours contributed the least to the EBC imbalance as u* and wind speeds declined, while daytime with high turbulence activities of u* up to 1.5 m/s and high wind speed generated a clear overestimation.

Another reason for the imbalance is the underestimation of G, which peaked during late afternoon (14:00-15:00) as shown in

Figure 4. This delay most likely developed due to the dense canopy of the tropical rain forest, which limits the absorption of SWin of the soil. The thermal wave propagation in the soil is delayed as depth increases, meaning that temperature fluctuations at the surface take longer to affect deeper soil layers. Ground heat flux decreases with depth due to the insulating properties of the humus-rich layer. This effect is more pronounced under forested areas compared to grasslands [

62].

The relationship of Rn and ε as a function of (z-d)/L and u* showed that highest net radiation gains the strongest overestimation as the atmosphere is weakly stable to neutral stratified (

Figure 8). With a net radiation loss, imbalances weaken under stable conditions. With respect to turbulence activities strongest overestimations developed with increasing u* during the transition hours as indicated by the decreasing Rn values.

As biases in the energy fluxes result in biases in the carbon fluxes NEE was examined in the diurnal cycle and modelled with independent variables (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). The mean diurnal pattern in NEE revealed a clear underestimation compared to [

1,

2]. This was likely due to underestimations during stable conditions. However, after filtering the fluxes the magnitude in carbon uptake was similar to [

29]. Modelling NEE revealed a good performance with R² = 0.52 for both, Rg and PPFD, which underpins the quality of the carbon fluxes.

Finally, microclimatological conditions and the energy and carbon fluxes were examined in the annual cycle to test the ability to map typical signals related to atmospheric conditions (

Figure 11). Here as well, H, LE and NEE reflected the dry and wet months. For drier month H achieved higher values associated with higher Rg indicating a reduced cloud coverage, while LE decreased. During these months, NEE showed a higher productivity as well, also attributed to an increased Rg, which fosters the photosynthetic activity [

8,

63].

Figure 1.

Study area and geographical location of the eddy covariance station. (a) Map of Ecuador, (b) location of the study site including drone image domain (c) Wind rose (m/s) for daytime and nighttime hours. (d) drone image of the site.

Figure 1.

Study area and geographical location of the eddy covariance station. (a) Map of Ecuador, (b) location of the study site including drone image domain (c) Wind rose (m/s) for daytime and nighttime hours. (d) drone image of the site.

Figure 2.

Mean diurnal course of meteorological variables from January 2020 to December 2022: (a) wind speed (m/s, boxplot, blue), (b) friction velocity (u* m/s, orange), (c) wind direction (degree, blue), and (d) Monin-Obukhov stability parameter ((z-d)/L), blue).

Figure 2.

Mean diurnal course of meteorological variables from January 2020 to December 2022: (a) wind speed (m/s, boxplot, blue), (b) friction velocity (u* m/s, orange), (c) wind direction (degree, blue), and (d) Monin-Obukhov stability parameter ((z-d)/L), blue).

Figure 3.

Diurnal course of storage capacity indicated by (a) normalized air temperature (Tanorm) and (b) normalized relative humidity (RHnorm) at the height levels 1 = 1m, 2 = 6m, 3 = 12.5m and 4 = 19m.

Figure 3.

Diurnal course of storage capacity indicated by (a) normalized air temperature (Tanorm) and (b) normalized relative humidity (RHnorm) at the height levels 1 = 1m, 2 = 6m, 3 = 12.5m and 4 = 19m.

Figure 4.

(a) Linear fit of the sum of sensible heat (H, W/m²) and latent heat (LE, W/m²) against net radiation (Rn, W/m²) minus ground heat flux (G, W/m²), (b) diurnal cycle of LE (dark blue, W/m²), H (orange, W/m²), G (red, W/m²), corrected net radiation (Rn*, solid blue line, W/m²), and un-corrected net radiation (Rn, dashed blue line, W/m²) for the time period January 2020 – December 2022; (c) as (a), without the addition of the storage effect and with storage effect, (d) diurnal cycle of turbulent energy fluxes without storage (LE and H, W/m²) and with addition of storage ( SLE and SH,W/m²) for the time period October – December 2022.

Figure 4.

(a) Linear fit of the sum of sensible heat (H, W/m²) and latent heat (LE, W/m²) against net radiation (Rn, W/m²) minus ground heat flux (G, W/m²), (b) diurnal cycle of LE (dark blue, W/m²), H (orange, W/m²), G (red, W/m²), corrected net radiation (Rn*, solid blue line, W/m²), and un-corrected net radiation (Rn, dashed blue line, W/m²) for the time period January 2020 – December 2022; (c) as (a), without the addition of the storage effect and with storage effect, (d) diurnal cycle of turbulent energy fluxes without storage (LE and H, W/m²) and with addition of storage ( SLE and SH,W/m²) for the time period October – December 2022.

Figure 5.

Boxplots representing the diurnal course of (a) the residuals (ε, W/m², purple) for the time period January 2020 – December 2022, (b) the residuals without storage values (ε, W/m², red) and with addition of storage (ε’, W/m², cyan) for the time period October – December 2022.

Figure 5.

Boxplots representing the diurnal course of (a) the residuals (ε, W/m², purple) for the time period January 2020 – December 2022, (b) the residuals without storage values (ε, W/m², red) and with addition of storage (ε’, W/m², cyan) for the time period October – December 2022.

Figure 6.

Binned means of residuals (ε, W/m2) as a function of (a) Monin-Obukhov stability parameter (z-d)/L and (b) friction velocity (u*, m/s). Axis is subjected to differ for subplots.

Figure 6.

Binned means of residuals (ε, W/m2) as a function of (a) Monin-Obukhov stability parameter (z-d)/L and (b) friction velocity (u*, m/s). Axis is subjected to differ for subplots.

Figure 7.

Relationship of residuals (ε, W/m²) with

(a) stability parameter ((z-d)/L, solid), (b) friction velocity (u*, dashed) at Daytime (orange line), Transition (green line), and Nighttime (blue line) as defined in

Table 1.

Figure 7.

Relationship of residuals (ε, W/m²) with

(a) stability parameter ((z-d)/L, solid), (b) friction velocity (u*, dashed) at Daytime (orange line), Transition (green line), and Nighttime (blue line) as defined in

Table 1.

Figure 9.

Daily cycle of unfiltered net ecosystem exchange (NEE, solid line, μmol/m²hour) and filtered NEE* (dashed line, μmol/m²hour) for the entire time period.

Figure 9.

Daily cycle of unfiltered net ecosystem exchange (NEE, solid line, μmol/m²hour) and filtered NEE* (dashed line, μmol/m²hour) for the entire time period.

Figure 10.

Relationship between net ecosystem exchange (NEE) and (a) global radiation (Rg, W/m²) and (b) photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD, mol/m²day). Daily means are used for analysis for specific time period between (8:00 – 16:00). Rg data span the entire period (January 2020 - December 2022), while PPFD data is limited to the period March 2022 - December 2022.

Figure 10.

Relationship between net ecosystem exchange (NEE) and (a) global radiation (Rg, W/m²) and (b) photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD, mol/m²day). Daily means are used for analysis for specific time period between (8:00 – 16:00). Rg data span the entire period (January 2020 - December 2022), while PPFD data is limited to the period March 2022 - December 2022.

Figure 11.

Box plots representing the annual course of daily values for (a) air temperature (Ta, °C), (b) relative humidity (RH, %), (c) global radiation (Rg, W/m2), (d) sensible heat flux (H, W/m²), (e) latent heat flux (LE, W/m²), and (f) net ecosystem exchange (NEE, μmol/m²day).

Figure 11.

Box plots representing the annual course of daily values for (a) air temperature (Ta, °C), (b) relative humidity (RH, %), (c) global radiation (Rg, W/m2), (d) sensible heat flux (H, W/m²), (e) latent heat flux (LE, W/m²), and (f) net ecosystem exchange (NEE, μmol/m²day).

Table 1.

Remaining data availability in percentage after filtering. The data was divided as Day (11:00-14:00), Night (20:00–6:00) and Transition (07:00-10:00) and (15:00-19:00).

Table 1.

Remaining data availability in percentage after filtering. The data was divided as Day (11:00-14:00), Night (20:00–6:00) and Transition (07:00-10:00) and (15:00-19:00).

| Filtering |

Time |

NEE |

H |

LE |

| Precipitation |

Day |

75% |

73% |

73% |

| Transition |

82% |

73% |

84% |

| Night |

95% |

85% |

87% |

| u* |

Day |

67% |

60% |

60% |

| Transition |

48% |

58% |

58% |

| Night |

34% |

21% |

21% |

Table 2.

Linear fits, explained variance (R²) and root mean square error (RMSE) of the sum of sensible heat (H, W/m²) and latent heat (LE, W/m²) as a function of available energy (Rn – G, W/m²) for H and LE without storage and with the addition of storage for the time period October 2022 – December 2022.

Table 2.

Linear fits, explained variance (R²) and root mean square error (RMSE) of the sum of sensible heat (H, W/m²) and latent heat (LE, W/m²) as a function of available energy (Rn – G, W/m²) for H and LE without storage and with the addition of storage for the time period October 2022 – December 2022.

| |

Intercept |

Slope |

R² |

RMSE |

| Without storage |

27.71 |

0.79 |

0.786 |

121.37 |

| With addition of storage |

27.20 |

0.80 |

0.789 |

120.37 |

Table 3.

Mean and sum of the storage effect generated by the sensible heat flux (S

H, W/m²), latent heat flux (S

LE, W/m²) and EBC residual (ε, W/m²) calculated over the diel (all), daytime, nighttime and transition hours as defined in

Table 1 for the time period October 2022 – December 2022.

Table 3.

Mean and sum of the storage effect generated by the sensible heat flux (S

H, W/m²), latent heat flux (S

LE, W/m²) and EBC residual (ε, W/m²) calculated over the diel (all), daytime, nighttime and transition hours as defined in

Table 1 for the time period October 2022 – December 2022.

| |

SH (W/m²) |

SLE (W/m²) |

ε (W/m²) |

| Mean |

Sum |

Mean |

Sum |

Mean |

Sum |

| All |

4.4 |

105.2 |

-5.6 |

-133.7 |

14.8 |

356.2 |

| Day |

6.8 |

27.1 |

-12.5 |

-49.9 |

56.9 |

227.8 |

| Night |

1.8 |

19.5 |

-2.6 |

-28.5 |

6.5 |

71.9 |

| Transition |

6.5 |

58.5 |

-6.1 |

-55.1 |

6.3 |

56.5 |

Table 4.

Linear fits, explained variance (R²) and root mean square error (RMSE) of the sum of sensible heat (H, W/m²) and latent heat (LE, W/m²) as a function of available energy (Rn – G, W/m²) for Day (11:00-14:00), Night (20:00–6:00) and Transition (07:00-10:00) and (15:00-19:00).

Table 4.

Linear fits, explained variance (R²) and root mean square error (RMSE) of the sum of sensible heat (H, W/m²) and latent heat (LE, W/m²) as a function of available energy (Rn – G, W/m²) for Day (11:00-14:00), Night (20:00–6:00) and Transition (07:00-10:00) and (15:00-19:00).

| Time period |

Intercept |

Slope |

R² |

RMSE |

| All data |

20.59 |

0.79 |

0.795 |

107.29 |

| Day |

135.8 |

0.56 |

0.545 |

133.32 |

| Night |

-31.19 |

-0.005 |

-- |

22.17 |

| Transition |

33.39 |

0.67 |

0.666 |

108.36 |