Submitted:

12 September 2024

Posted:

14 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

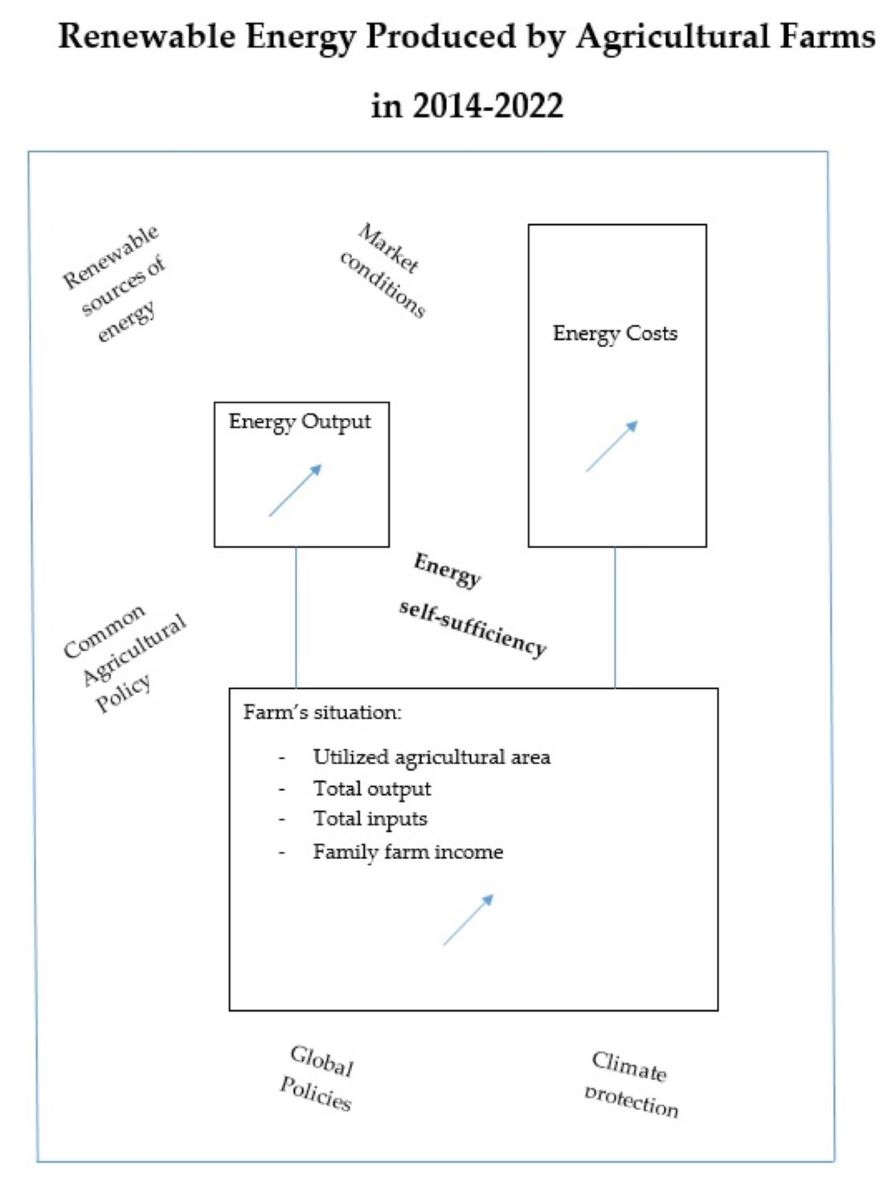

2. Materials and Methods

- How much did the European family farm earn money on energy output and spend on energy costs between the years 2014 and 2022 and what were at the same time its area, total output, costs and family farm income?

- In which European country do family farms have the highest average energy production and are they also affected by the highest energy costs?

- Does the energy output and costs of farms depending on their economic size or type of production?

- Which categories (f. ex.: area, assets, cash flow, equity, income, investment, labour, liabilities, output, taxes) interact with energy output and energy costs?

- -

- i (i = 1, ..., N) as individuals,

- -

- t (t = 1, ..., T) as time periods,

- -

- -X’i,t as the observation of K explanatory variables in country i and time t,

- -

- αi as parameter which is time invariant and accounts for any individual-specific effect not included in the regression equation.

3. Results

- Y01 – Energy Output,

- Y02 – Energy Costs,

- X01 – Labour Input,

- X02 – Utilized Agricultural Area,

- X03 – Total Output,

- X04 – Total Inputs,

- X05 – Taxes,

- X06 – Family Farm Income,

- X07 – Assets,

- X08 – Liabilities,

- X09 – Gross Investment,

- X10 – Net Investment,

- X11 – Cash Flow,

- X12 – Balance Current Subsidies and Taxes.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- How much did the European family farm earn money on energy output and spend on energy costs between the years 2014 and 2022 and what were at the same time its area, total output, costs and family farm income?

- In which European country do family farms have the highest average energy production and are they also affected by the highest energy costs?

- Does the energy output and costs of farms depending on their economic size or type of production?

- Which categories (f. ex.: area, assets, cash flow, equity, income, investment, labour, liabilities, output, taxes) interact with energy output and energy costs?

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IRENA-FAO. Renewable energy for agri-food systems. Towards the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement. IREA and FAO: Abu Dhabi and Rome, United Arab Emirates and Italy, 2021. [CrossRef]

- EIP-AGRI. Renewable energy on the farm, 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/eip/agriculture/sites/default/files/eip-agri_factsheet_renewable_energy_on_the_farm_2019_en.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- EuropaBio – The European Association for Bioindustries. Industrial Biotechnology: Enabling the Development of the Bioeconomy. 2022. Available online: https://www.europabio.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/5.-Industrial-Biotechnology-Enabling-the-Development-of-the-Bioeconomy.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- EuropaBio – The European Association for Bioindustries. Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions with the Bioeconomy. 2022. Available online: https://www.europabio.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/6.-Reducing-Greenhouse-Gas-Emissions-with-the-Bioeconomy.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- European Commission, What is the bioeconomy? (last updated: 17.02.2016), 2016, https://ec.europa.eu/research/bioeconomy/index.cfm (accessed on 1 February 2016).

- Vivien, F.-D.; Nieddu, M.; Befort, N.; Debref, R.; Giampietro, M. The hijacking of the bioeconomy. Ecological Economics 2019, 159, pp. 189–197, . [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, Ch. Renewable energy for sustainable agriculture. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2011, 31 (1), pp. 91-118. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the Connection between Economy, Society and the Environment: Updated Bioeconomy Strategy, Publications Office, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Pestisha, A.; Gabnai, Z.; Chalgynbayeva, A.; Lengyel, P.; Bai, A. On-Farm Renewable Energy Systems: A Systematic Review. Energies 2023, 16, 862. [CrossRef]

- SARE – Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education. Sustainable Production and Use of On-Farm Energy, 2017. https://www.sare.org/resources/sustainable-production-and-use-of-on-farm-energy/ (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Co-operation. Renewable Energy in Agriculture, Rural Radio Resource Pack 2008, 3; Wageningen, The Netherlands: CTA. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/9f0cec5e-e3fb-44ad-91c3-c3c5a5108509/content (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Both, A. J. Correction to: On-Farm Energy Production: Solar, Wind, Geothermal. In Regional Perspectives on Farm Energy; Ciolkosz, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 95-105. [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Bioeconomy to 2030: Designing a Policy Agenda; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009, . [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Innovating for Sustainable Growth: a Bioeconomy for Europe, Publications Office, 2012, Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/research/bioeconomy/pdf/201202_innovating_sustainable_growth_en.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, A Bioeconomy Strategy for Europe: Working with Nature for a More Sustainable Way of Living, Publications Office, 2013, . [CrossRef]

- 7th Environment Action Programme, Decision No 1386/2013/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 November 2013 on a General Union Environment Action Programme to 2020 “Living well, within the limits of our planet”, Official Journal of the European Union L 354/171, 28.12.2013. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32013D1386 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- EEA Report, The Circular Economy and the Bioeconomy. Partners in Sustainability, 02/2018, Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/circular-economy-and-bioeconomy (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: a New European Innovation Agenda, COM(2022) 332 final, 5.7.2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52022DC0332&from=EN (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- United Nations, Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, General Assembly UN, 2015, Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/291/89/PDF/N1529189.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- European Commission, Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Implementation of the Circular Economy Action Plan, COM (2019) 190 final, 4.3.2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0190 &from=EN (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- EuropaBio – The European Association for Bioindustries. Buying into Biobased. Benefiting Consumers Now and for the Future. 2022. Available online: https://www.europabio.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/4.-Buying-into-Biobased-Benefiting-Consumers-Now-and-for-the-Future.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- EuropaBio – The European Association for Bioindustries. Bioeconomy: Circular by Nature. 2022. Available online: https://www.europabio.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2.-Bioeconomy-Circular-by-Nature.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Komor, A. Specjalizacje regionalne w zakresie biogospodarki w Polsce w układzie wojewódzkim. Roczniki Naukowe SERiA 2014, XVI, 6, pp. 248-253.

- Brzezina, N.; Biely, K.; Helfgott, A.; Kopainsky, B.; Vervoort, J.; Mathijs, E. Development of organic farming in Europe at thecrossroads: Looking for the way forward through system archetypes lenses. Sustainability 2017, 9, 821. [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B. H. Econometric analysis of panel data. 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, United Kingdom, 2005; pp. 11-12.

- Arbia, G.; Piras. G. Convergence in per-capita GDP across European regions using panel data models extended to spatial autocorrelation effects. Istituto di Studi e Analisi Economica, Working Paper 51, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J. M. Introductory econometrics. A modern approach. 5th ed. South-Western Cengage Learning: Mason, United States; 2013, pp. 495-496.

- Dańska-Borsiak, B. Dynamiczne modele panelowe w badaniach ekonomicznych. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2011; pp. 29-32.

- Rahman, Md M., Khan, I., Field, D. L., Techato, K., Alameh, K. Powering agriculture: Present status, future potential, and challenges of renewable energy applications. Renewable Energy 2022, 188, pp. 731-749, . [CrossRef]

- EIP-AGRI, Minipaper: Business Models and Financial Alternatives for On-Farm Renewable Energy Projects, 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/eip/agriculture/sites/default/files/fg28_mp_businessmodels_2018_en.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Ali, S. M., Dash, N., Pradhan, A. Role of Renewable Energy on Agriculture. International Journal of Engineering Sciences Emerging Technologies 2012, 4, 1, pp. 51-57.

- European Parliament Resolution of 2 July 2013 on the contribution of cooperatives to overcoming the crisis (2012/2321(INI)) (2016/C 075/05), Official Journal of the European Union C75/34. 26.02.2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52013IP0301&rid=7.

- Rozakis, S.; Juvančič, L.; Kovacs, B. Bioeconomy for Resilient Post-COVID Economies. Energies 2022, 15, . [CrossRef]

- Hurmekoski, E.; Lovrić, M.; Lovrić, N.; Hetemäki, L.; Winkel, G. Frontiers of the forest-based bioeconomy – A European Delphi study. Forest Policy and Economics 2019, 102, pp. 86-99, . [CrossRef]

- DeBoer, J.; Panwar, R.; Kozak, R.; Cashore, B. Squaring the circle: Refining the competitiveness logic for the circular bioeconomy. Forest Policy and Economics 2020, 110 (C), 101858. [CrossRef]

- Purkus, A.; Hagemann, N.; Bedtke, N.; Gawel, E. Towards a sustainable innovation system for the German wood-based bioeconomy: Implications for policy design. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 172, pp. 3955–3968, . [CrossRef]

- Kircher, M.; Maurer, K.H.; Herzberg, D. KBBE: The Knowledge-based Bioeconomy: Concept, Status and Future Prospects. EFB Bioeconomy Journal 2022, 2, . [CrossRef]

- OECD. Meeting Policy Challenges for a Sustainable Bioeconomy, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018, . [CrossRef]

- Bracco, S.; Calicioglu, O.; Gomez San Juan, M.; Flammini, A. Assessing the contribution of bioeconomy to the total economy: A review of national frameworks. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1698, . [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, C.-I.; Loizou, E.; Chatzitheodoridis, F. Priorities in Bioeconomy Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review. Energies 2022, 15, . [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, B.; Filippelli, S. Investigating circular business model innovation through keywords analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13(9), 5036, . [CrossRef]

- Linder, M.; Williander, M. Circular Business Model Innovation: Inherent Uncertainties. Business Strategy and the Environment 2017, 26, pp. 182-196, . [CrossRef]

- Sili, M.; Dürr, J. Bioeconomic Entrepreneurship and Key Factors of Development: Lessons from Argentina. Sustainability 2022, 14(4), 2447, . [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.; Strupeit, L.; Whalen, K.; Nußholz, J. A Review and Evaluation of Circular Business Model Innovation Tools. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2210. [CrossRef]

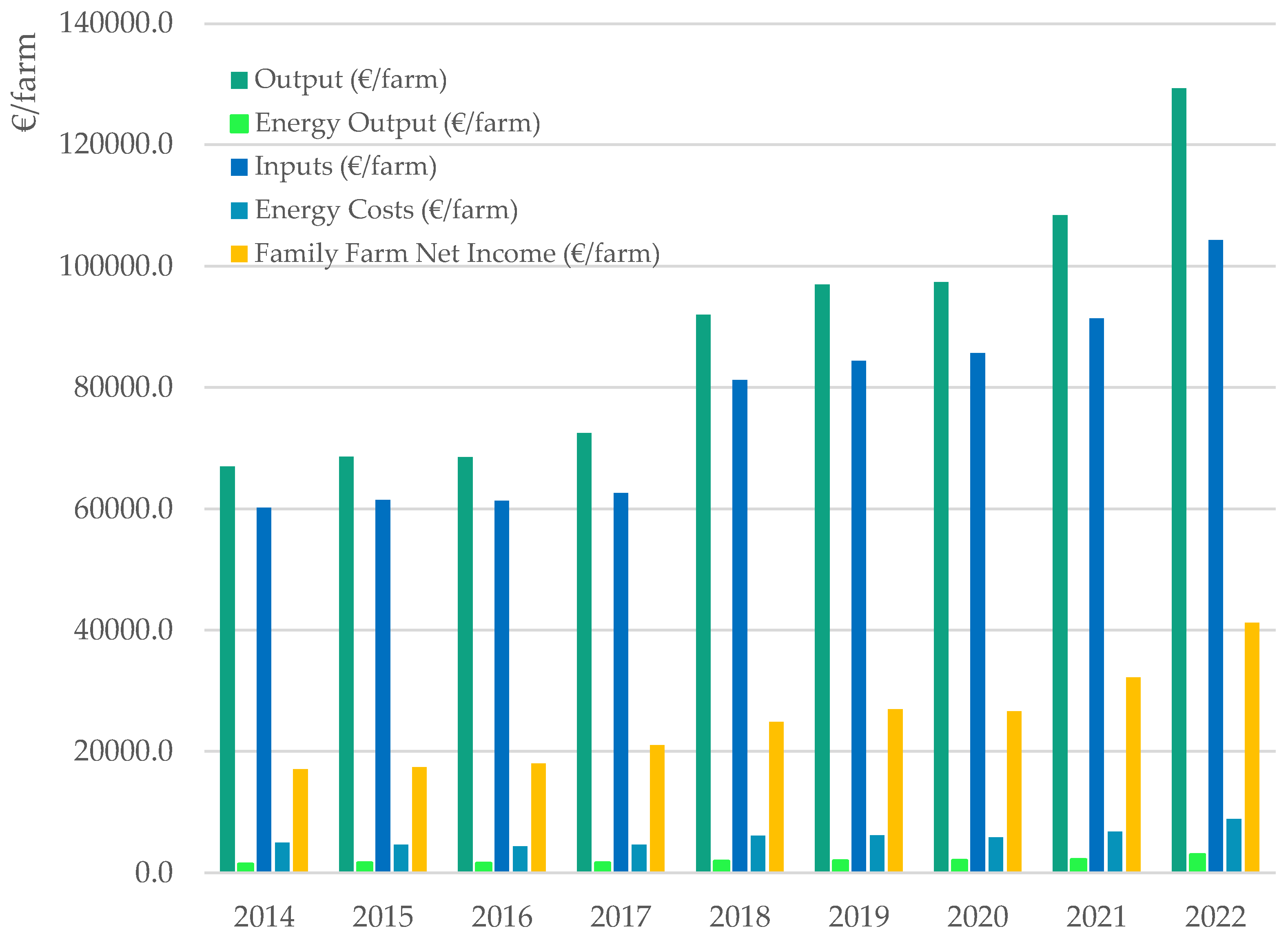

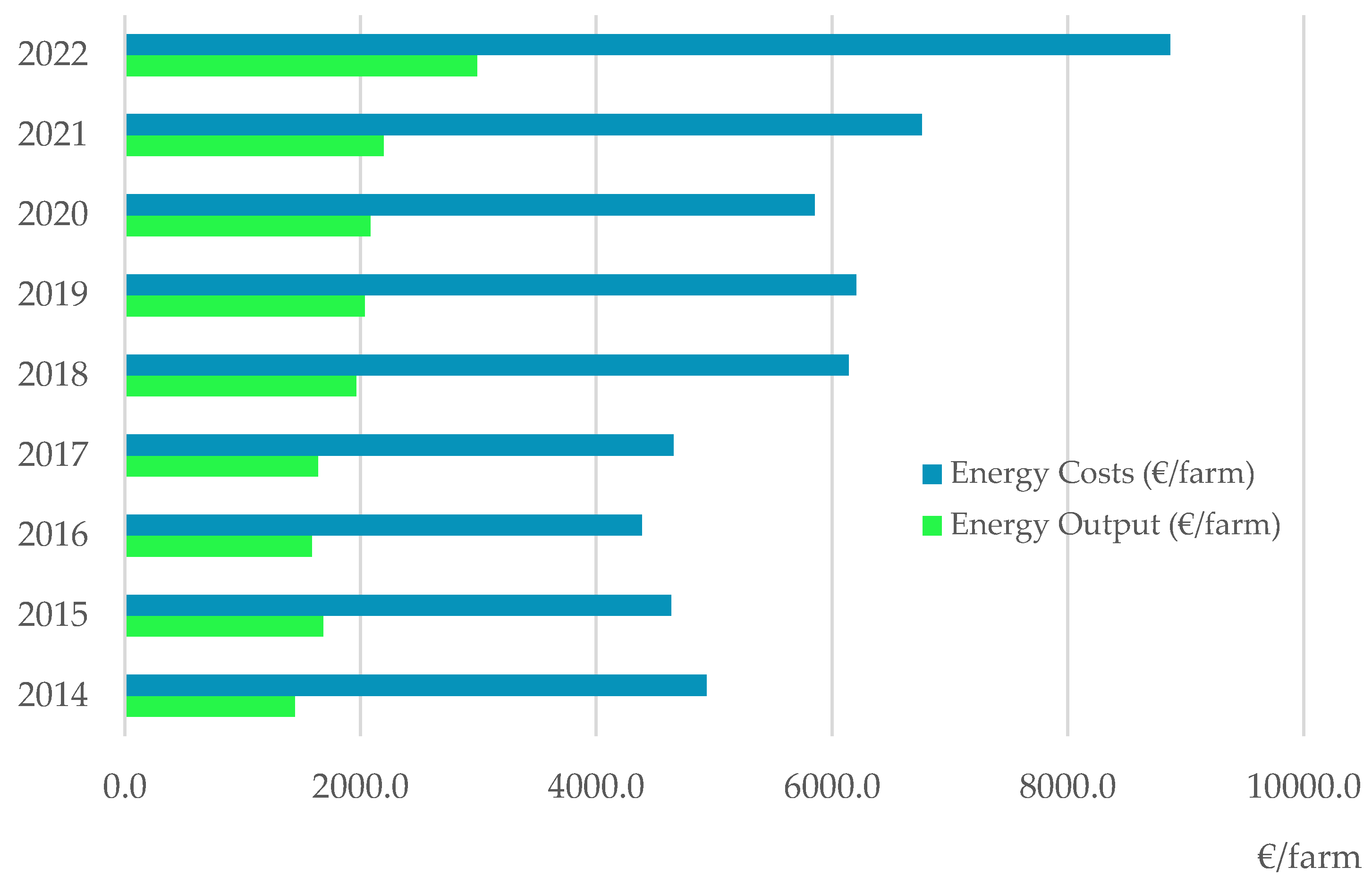

| Year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Utilised Agricultural Area (ha/farm) | 31.2 | 31.7 | 31.9 | 32.4 | 40.1 | 40.1 | 40.3 | 40.3 | 40.4 |

| Output (€/farm), including: | 66 953.0 | 68 553.0 | 68 499.0 | 72 504.0 | 92 005.0 | 96 952.0 | 97 364.0 | 108 370.0 | 129 341.0 |

| - Energy output (€/farm) | 1 442.0 | 1 685.0 | 1 590.0 | 1 640.0 | 1 965.0 | 2 035.0 | 2 084.0 | 2 196.0 | 2 990.0 |

| - Share of energy output in total output (%) | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.3 |

| Inputs (€/farm), including: | 60 147.0 | 61 479.0 | 61 304.0 | 62 607.0 | 81 218.0 | 84 392.0 | 85 662.0 | 91 408.0 | 104 325.0 |

| - Energy costs (€/farm) | 4 936.0 | 4 634.0 | 4 387.0 | 4 655.0 | 6 141.0 | 6 206.0 | 5 853.0 | 6 763.0 | 8 869.0 |

| - Share of energy costs in total intput (%) | 8.2 | 7.5 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 8.5 |

| Farm Net Income (€/farm) | 17 053.0 | 17 427.0 | 18 006.0 | 21 026.0 | 24 900.0 | 26 954.0 | 26 597.0 | 32 176.0 | 41 214.0 |

| Relation of energy output to energy costs (%) | 29.2 | 36.4 | 36.2 | 35.2 | 32.0 | 32.8 | 35.6 | 32.5 | 33.7 |

| Place in the ranking | Member State | Energy Costs (€/farm) | Member State | Energy Costs per 1ha (€/ha) | Member State | Energy Output (€/farm) | Member State | Energy Output per 1ha (€/ha) | Member State | AVERAGE RANGS |

| 1 | Slovakia | 54 871.0 | Malta | 1 465.8 | Denmark | 27 889.0 | Netherlands | 448.4 | Netherlands | 2.0 |

| 2 | Czechia | 41 652.0 | Netherlands | 870.0 | Netherlands | 18 212.0 | Hungary | 236.6 | Germany | 5.0 |

| 3 | Netherlands | 35 338.0 | Cyprus | 387.5 | Czechia | 16 882.0 | Denmark | 186.5 | Belgium | 6.0 |

| 4 | Germany | 26 188.0 | Belgium | 295.4 | Germany | 15 835.0 | Belgium | 178.1 | Denmark | 6.0 |

| 5 | Denmark | 22 572.0 | Slovenia | 270.6 | Slovakia | 14 967.0 | Luxembourg | 157.7 | Czechia | 6.8 |

| 6 | Sweden | 22 479.0 | Germany | 253.3 | Luxembourg | 14 708.0 | Germany | 153.2 | Hungary | 8.3 |

| 7 | Finland | 16 997.0 | Greece | 253.0 | Hungary | 12 253.0 | Italy | 82.6 | Luxembourg | 8.8 |

| 8 | Belgium | 16 138.0 | Italy | 223.9 | Belgium | 9 733.0 | Austria | 82.5 | Slovakia | 9.0 |

| 9 | Estonia | 15 250.0 | Finland | 217.5 | Estonia | 8 269.0 | Czechia | 66.0 | Sweden | 9.3 |

| 10 | Luxembourg | 14 956.0 | Sweden | 215.6 | Sweden | 4 131.0 | Estonia | 54.2 | Austria | 11.3 |

| 11 | France | 12 840.0 | Austria | 199.0 | Austria | 2 780.0 | Sweden | 39.6 | Italy | 11.3 |

| 12 | Hungary | 9 255.0 | Hungary | 178.7 | Latvia | 2 236.0 | Slovakia | 36.4 | Finland | 12.0 |

| 13 | Latvia | 8 505.0 | Czechia | 162.9 | France | 2 137.0 | Slovenia | 32.9 | Estonia | 13.0 |

| 14 | Bulgaria | 7 723.0 | Luxembourg | 160.3 | Italy | 1 914.0 | Latvia | 30.5 | France | 14.0 |

| 15 | Austria | 6 702.0 | Denmark | 151.0 | Finland | 1 320.0 | France | 22.7 | Slovenia | 14.3 |

| 16 | Italy | 5 185.0 | Poland | 151.0 | Slovenia | 378.0 | Croatia | 17.7 | Latvia | 14.8 |

| 17 | Spain | 4 977.0 | France | 136.5 | Croatia | 283.0 | Finland | 16.9 | Greece | 16.8 |

| 18 | Lithuania | 4 609.0 | Slovakia | 133.6 | Greece | 171.0 | Greece | 16.5 | Cyprus | 18.0 |

| 19 | Cyprus | 4 553.0 | Croatia | 129.0 | Ireland | 123.0 | Portugal | 3.3 | Malta | 18.3 |

| 20 | Malta | 4 412.0 | Latvia | 115.9 | Bulgaria | 122.0 | Ireland | 2.7 | Croatia | 19.8 |

| 21 | Ireland | 4 046.0 | Spain | 112.9 | Lithuania | 113.0 | Lithuania | 2.2 | Bulgaria | 20.0 |

| 22 | Poland | 3 226.0 | Portugal | 103.3 | Portugal | 81.0 | Poland | 2.1 | Poland | 20.8 |

| 23 | Slovenia | 3 107.0 | Bulgaria | 100.6 | Poland | 44.0 | Bulgaria | 1.6 | Spain | 21.5 |

| 24 | Greece | 2 629.0 | Estonia | 99.9 | Spain | 3.0 | Spain | 0.1 | Lithuania | 21.5 |

| 25 | Portugal | 2 507.0 | Romania | 95.7 | Cyprus | 0.0 | Cyprus | 0.0 | Ireland | 21.8 |

| 26 | Romania | 2 389.0 | Lithuania | 88.4 | Malta | 0.0 | Malta | 0.0 | Portugal | 22.0 |

| 27 | Croatia | 2 067.0 | Ireland | 87.6 | Romania | 0.0 | Romania | 0.0 | Romania | 26.3 |

| - | EU27 | 6 763.0 | EU27 | 167.6 | EU27 | 2 196.0 | EU27 | 54.4 | - | - |

| Details: | Classes of Economic Size | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 2 000 ≤ 8 000 € Very Small |

2 8 000 ≤ 25 000 € Small |

3 25 000 ≤ 50 000 € Medium-Low |

4 50 000 ≤ 100 000 € Medium-Large |

5 100 000 ≤ 500 000 € Large |

6 ≥ 500 000 € Very Large |

|

| EU-27 | ||||||

| Utilised Agricultural Area (ha/farm) | 6.0 | 13.9 | 27.2 | 48.1 | 97.9 | 252.8 |

| Output (€/farm), including: | 8 474.0 | 20 730.0 | 44 781.0 | 85 175.0 | 251 093.0 | 126 5074.0 |

| - Energy output (€/farm) | 22.0 | 107.0 | 894.0 | 1 067.0 | 3 452.0 | 40 521.0 |

| - Share of energy output in total output (%) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 3.2 |

| Inputs (€/farm), including: | 7 268.0 | 15 231.0 | 35 878.0 | 67 698.0 | 209 852.0 | 1 125 294.0 |

| - Energy costs (€/farm) | 814.0 | 1 704.0 | 3 439.0 | 5 883.0 | 14 896.0 | 71 585.0 |

| - Share of energy costs in total intput (%) | 11.2 | 11.2 | 9.6 | 8.7 | 7.1 | 6.4 |

| Relation of energy output to energy costs (%) | 2.7 | 6.3 | 26.0 | 18.1 | 23.2 | 56.6 |

| Netherlands | ||||||

| Utilised Agricultural Area (ha/farm) | - | - | 15.8 | 22.8 | 38.5 | 57.7 |

| Output (€/farm), including: | - | - | 90 572.0 | 138 822.0 | 364 407.0 | 1 486 655.0 |

| - Energy output (€/farm) | - | - | 6 423.0 | 6 010.0 | 3 807.0 | 47 341.0 |

| - Share of energy output in total output (%) | - | - | 7.1 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 3.2 |

| Inputs (€/farm), including: | - | - | 88 307.0 | 121 442.0 | 319 371.0 | 1 294 096.0 |

| - Energy costs (€/farm) | - | - | 4 788.0 | 6 381.0 | 16 689.0 | 82 448.0 |

| - Share of energy costs in total intput (%) | - | - | 5.4 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 6.4 |

| Relation of energy output to energy costs (%) | - | - | 134.1 | 94.2 | 22.8 | 57.4 |

| Germany | ||||||

| Utilised Agricultural Area (ha/farm) | - | - | 33.9 | 49.3 | 91.0 | 340.2 |

| Output (€/farm), including: | - | - | 60 703.0 | 102 793.0 | 308 850.0 | 1 308 528.0 |

| - Energy output (€/farm) | - | - | 5 189.0 | 4 157.0 | 7 517.0 | 81 155.0 |

| - Share of energy output in total output (%) | - | - | 8.5 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 6.2 |

| Inputs (€/farm), including: | - | - | 62 156.0 | 98 603.0 | 282 820.0 | 1 311 022.0 |

| - Energy costs (€/farm) | - | - | 6 296.0 | 9 664.0 | 23 117.0 | 93 794.0 |

| - Share of energy costs in total intput (%) | - | - | 10.1 | 9.8 | 8.2 | 7.2 |

| Relation of energy output to energy costs (%) | - | - | 82.4 | 43.0 | 32.5 | 86.5 |

| Details: | Type of production | |||||||

| Field-crops | Horticul-ture | Wine | Other permanent crops | Milk | Other grazing livestock | Granivo-res | Mixed | |

| EU-27 | ||||||||

| Utilised Agricultural Area (ha/farm) | 52.7 | 7.3 | 16.4 | 13.8 | 49.7 | 53.3 | 43.0 | 40.7 |

| Output (€/farm), including: | 84 278.0 | 242 889.0 | 104 567.0 | 47 848.0 | 192 509.0 | 66 967.0 | 490 316.0 | 88 654.0 |

| - Energy output (€/farm) | 2 204.0 | 9 521.0 | 554.0 | 464.0 | 3 094.0 | 738.0 | 7 107.0 | 2 381.0 |

| - Share of energy output in total output (%) | 2.6 | 3.9 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.7 |

| Inputs (€/farm), including: | 68 617.0 | 188 288.0 | 72 553.0 | 31 899.0 | 166 710.0 | 64 460.0 | 448 381.0 | 84 079.0 |

| - Energy costs (€/farm) | 6 417.0 | 16 623.0 | 3 762.0 | 2 711.0 | 10 988.0 | 4 626.0 | 21 726.0 | 6 157.0 |

| - Share of energy costs in total intput (%) | 9.4 | 8.8 | 5.2 | 8.5 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 4.8 | 7.3 |

| Relation of energy output to energy costs (%) | 34.3 | 57.3 | 14.7 | 17.1 | 28.2 | 16.0 | 32.7 | 38.7 |

| Netherlands | ||||||||

| Utilised Agricultural Area (ha/farm) | 51.5 | 16.5 | - | 16.1 | 61.5 | 28.0 | 11.6 | 46.6 |

| Output (€/farm), including: | 308 020.0 | 1 560 037.0 | - | 461 989.0 | 470 080.0 | 230 074.0 | 1 124 691.0 | 786 972.0 |

| - Energy output (€/farm) | 5 250.0 | 69 942.0 | - | 21 228.0 | 5 105.0 | 8 431.0 | 14 054.0 | 5 722.0 |

| - Share of energy output in total output (%) | 1.7 | 4.5 | - | 4.6 | 1.1 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| Inputs (€/farm), including: | 277 047.0 | 1 245 078.0 | - | 402 632.0 | 417 969.0 | 215 720.0 | 1 127 413.0 | 719 400.0 |

| - Energy costs (€/farm) | 18 588.0 | 10 6993.0 | - | 15 767.0 | 19 290.0 | 12 150.0 | 37 102.0 | 27 468.0 |

| - Share of energy costs in total intput (%) | 6.7 | 8.6 | - | 3.9 | 4.6 | 5.6 | 3.3 | 3.8 |

| Relation of energy output to energy costs (%) | 28.2 | 65.4 | - | 134.6 | 26.5 | 69.4 | 37.9 | 20.8 |

| Germany | ||||||||

| Utilised Agricultural Area (ha/farm) | 138.1 | 12.5 | 15.5 | 42.2 | 92.2 | 73.2 | 82.8 | 162.0 |

| Output (€/farm), including: | 276 095.0 | 790 269.0 | 186 812.0 | 300 755.0 | 398 198.0 | 140 205.0 | 522 686.0 | 471 212.0 |

| - Energy output (€/farm) | 12 488.0 | 113 497.0 | 6 419.0 | 29 013.0 | 10 596.0 | 4 746.0 | 13 455.0 | 31 316.0 |

| - Share of energy output in total output (%) | 4.5 | 14.4 | 3.4 | 9.6 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 6.6 |

| Inputs (€/farm), including: | 274 000.0 | 688 116.0 | 135 927.0 | 283 739.0 | 353 913.0 | 145 515.0 | 544 979.0 | 496 272.0 |

| - Energy costs (€/farm) | 24 555.0 | 48 169.0 | 7 648.0 | 18 383.0 | 29141.0 | 12 836.0 | 32 046.0 | 37 855.0 |

| - Share of energy costs in total intput (%) | 9.0 | 7.0 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 8.2 | 8.8 | 5.9 | 7.6 |

| Relation of energy output to energy costs (%) | 50.9 | 235.6 | 83.9 | 157.8 | 36.4 | 37.0 | 42.0 | 82.7 |

|

Details |

Classes of Economic Size | |||||

|

1 2 000 ≤ 8 000 € Very Small |

2 8 000 ≤ 25 000 € Small |

3 25 000 ≤ 50 000 € Medium-Low |

4 50 000 ≤ 100 000 € Medium-Large |

5 100 000 ≤ 500 000€ Large |

6 ≥ 500 000 € Very Large |

|

| Number of Observations | 105 | 173 | 209 | 216 | 216 | 175 |

| Models for Energy Output (Y01) | ||||||

| LSDV R2 | 0.6108 | 0.8872 | 0.9207 | 0.9182 | 0.8700 | 0.9145 |

| Within R2 | 0.0398 | 0.2050 | 0.4021 | 0.3538 | 0.0575 | 0.2681 |

| const | -126.5520 (0.3314) |

-199.2900 (0.7498) |

-2 245.7800 (0.3375) |

-1 303.0800 (0.6802) |

3 406.9000 (0.4211) |

94 860.7000 (0.0000) |

| X02 – Utilized Agricultural Area | - | - | -233.3140 (0.0000) |

- | -55.9753 (0.0266) |

-147.4130 (0.0003) |

| X03 – Total Output | - | - | - | 0.3372 (0.0000) |

- | 0.2444 (0.0025) |

| X04 – Total Inputs | 0.0338 (0.0567) |

0.1347 (0.0000) |

0.4091 (0.0000) |

- | 0.0443 (0.0031) |

-0.1882 (0.0141) |

| X05 – Taxes | - | - | -3.5478 (0.0229) |

-2.8264 (0.0418) |

- | - |

| X06 – Family Farm Income | - | - | - | -0.3152 (0.0000) |

- | -0.2762 (0.0008) |

| X07 – Assets | - | - | -0.0097 (0.0125) |

-0.0278 (0.0000) |

- | - |

| X08 - Liabilities | - | -0.0644 (0.0000) |

- | - | - | - |

| X09 – Gross Investment | - | - | - | 0.0718 (0.0500) |

- | - |

| Hausman Test | χ2 (1) = 0.2188 (0.6400) REM Rejected |

χ2 (2) = 18.3722 (0.0010) REM Not Rejected, FEM Sufficiently Close |

χ2 (4) = 6.0772 (0.1935) REM Rejected |

χ2 (5) = 14.3278 (0.0137) REM Not Rejected, FEM Sufficiently Close |

χ2 (2) = 3.3770 (0.1848) REM Rejected |

χ2 (4) = 12.8339 (0.0121) REM Not Rejected, FEM Sufficiently Close |

| Models of Energy Costs (Y02) | ||||||

| LSDV R2 | 0.9280 | 0.9462 | 0.9348 | 0.9312 | 0.9494 | 0.9755 |

| Within R2 | 0.7072 | 0.4271 | 0.4715 | 0.4234 | 0.5267 | 0.5169 |

| const | 121.2400 (0.0726) |

-13.3703 (0.9455) |

-61.6414 (0.8593) |

-807.2930 (0.2529) |

-10 798.5000 (0.0000) |

-28 514.4000 (0.0054) |

| X02 – Utilized Agricultural Area | - | 95.8487 (0.0000) |

90.5202 (0.0000) |

67.4532 (0.0000) |

124.2020 (0.0000) |

142.2290 (0.0000) |

| X03 – Total Output | 0.1104 (0.0000) |

0.0172 (0.0000) |

0.0276 (0.0000) |

0.0490 (0.0000) |

0.0880 (0.0000) |

0.0499 (0.0000) |

| X06 – Family Farm Income | -0.1187 (0.0000) |

- | -0.0318 (0.0002) |

-0.0199 (0.0332) |

-0.0982 (0.0000) |

- |

| X08 - Liabilities | - | - | - | - | -0.0168 (0.0003) |

- |

| X11 – Cash Flow | - | - | - | - | - | -0.0614 (0.0006) |

| X12 – Balance Current Subsidies and Taxes | 0.1248 (0.0000) |

- | - | - | - | - |

| Hausman Test | χ2 (3) = 0.5861 (0.8996) REM Rejected |

χ2 (2) = 4.6274 (0.0989) REM Rejected |

χ2 (3) = 8.7148 (0.0333) REM Not Rejected, FEM Sufficiently Close |

χ2 (3) = 4.8540 (0.1828) REM Rejected |

χ2 (4) = 14.1556 (0.0068) REM Not Rejected, FEM Sufficiently Close |

χ2 (3) = 10.5646 (0.0143) REM Not Rejected, FEM Sufficiently Close |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).