Submitted:

04 September 2024

Posted:

10 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

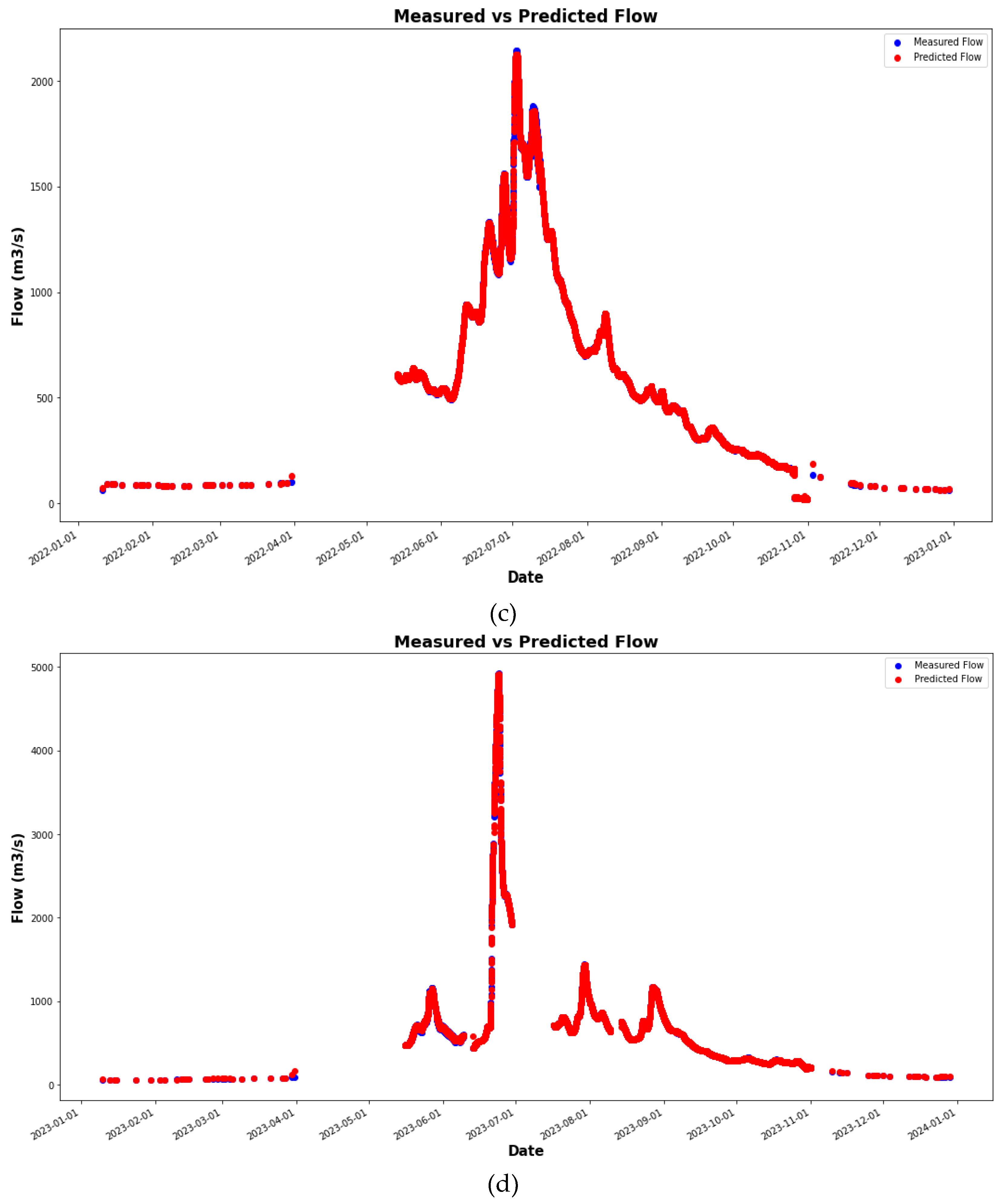

2.1. Study Area and Data Collection

2.2. Mathematic Models

2.2.1. Moving Average

2.2.2. Exponential Smoothing

2.2.3. Triple Exponential Smoothing “Holt-Winters”

3. Model Implementation

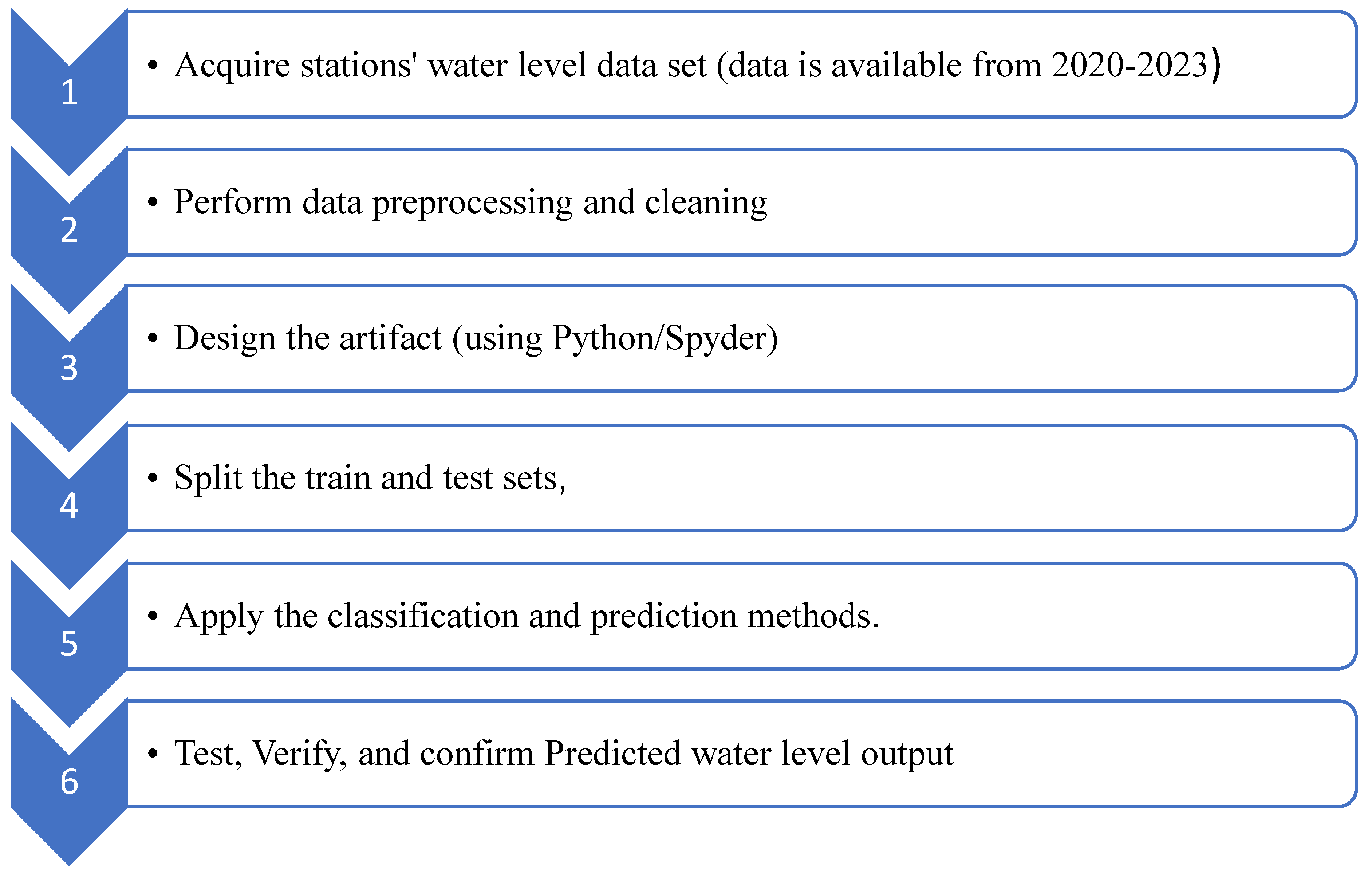

3.1. Implementation Procedure

3.2. Statistics Performance

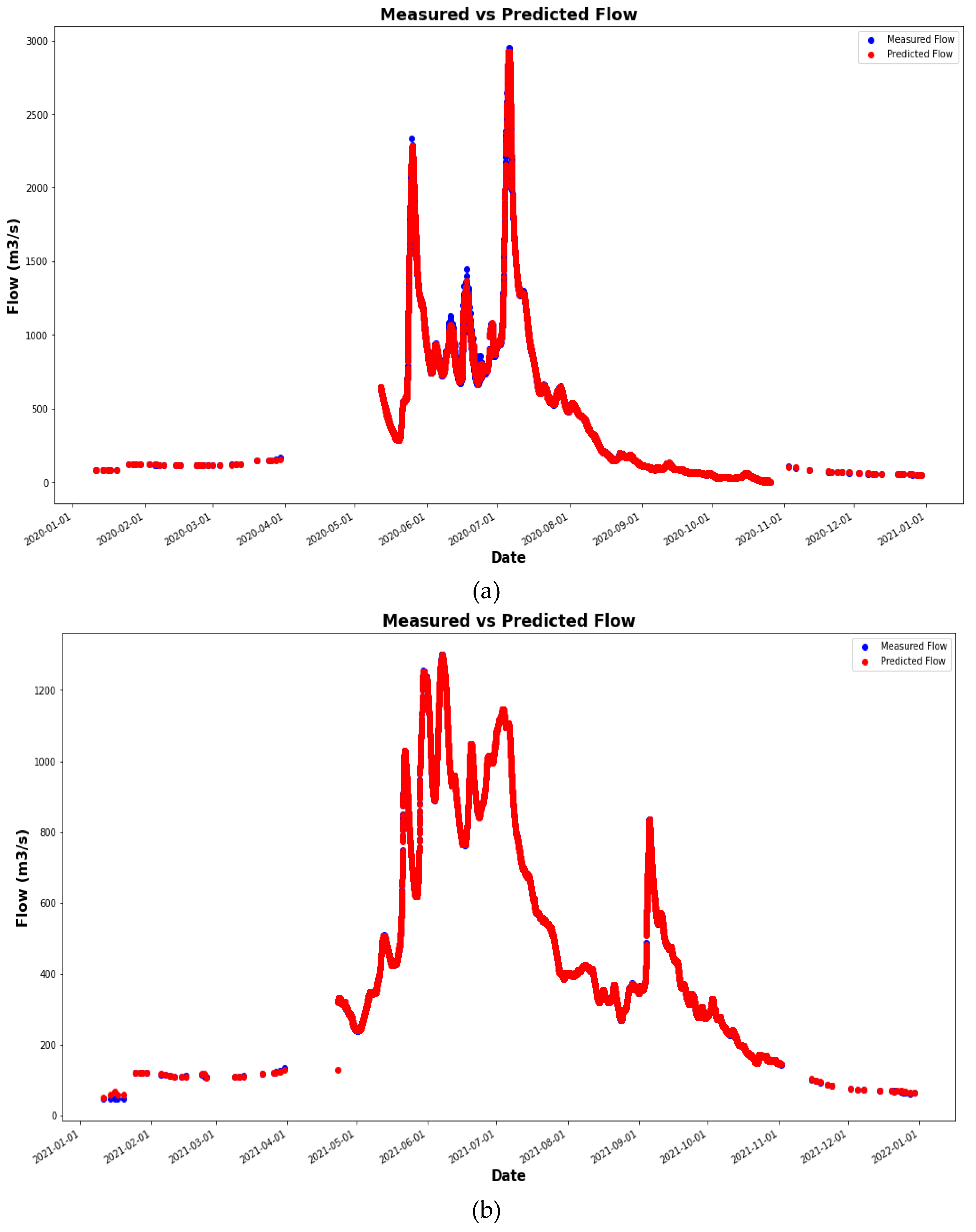

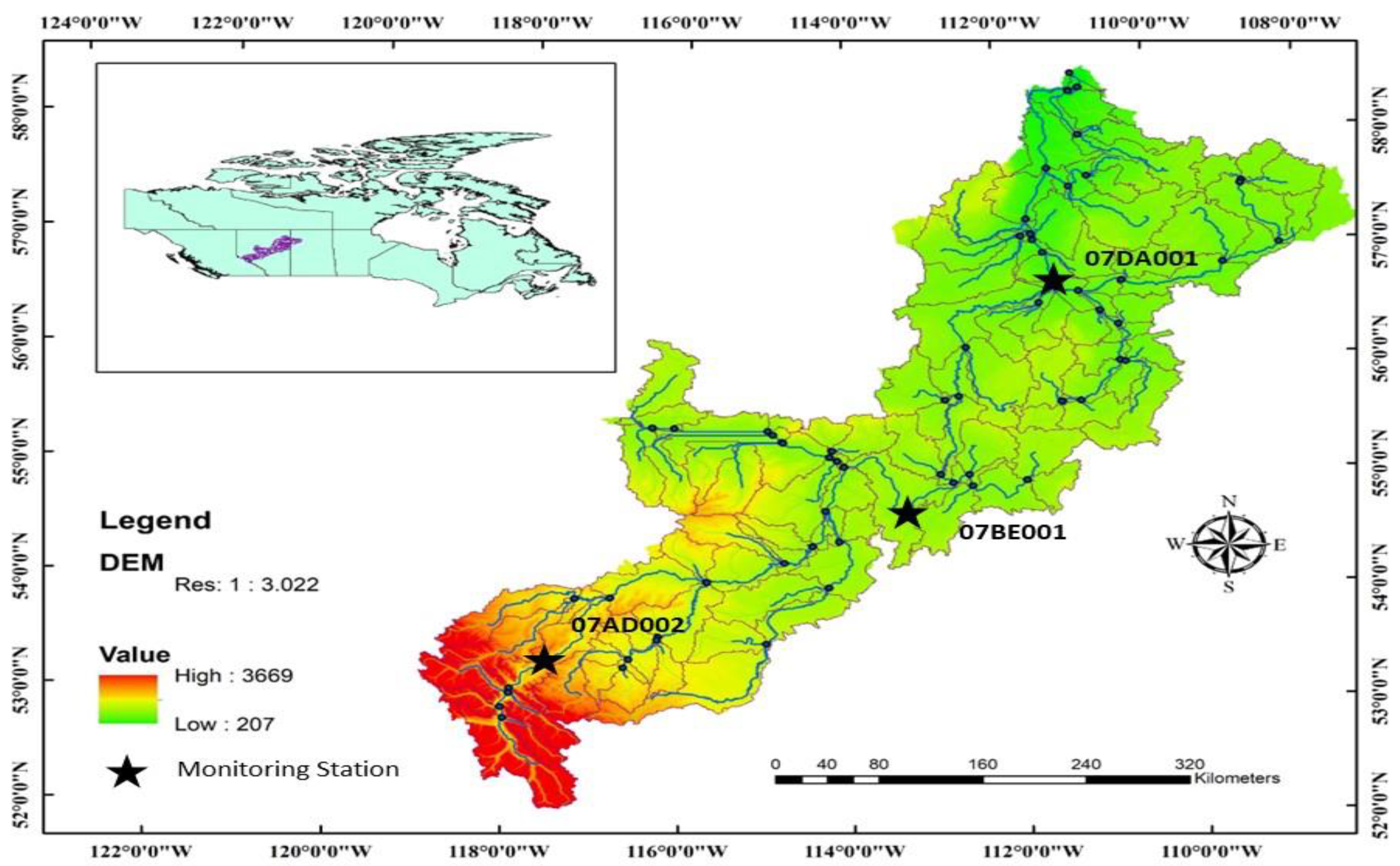

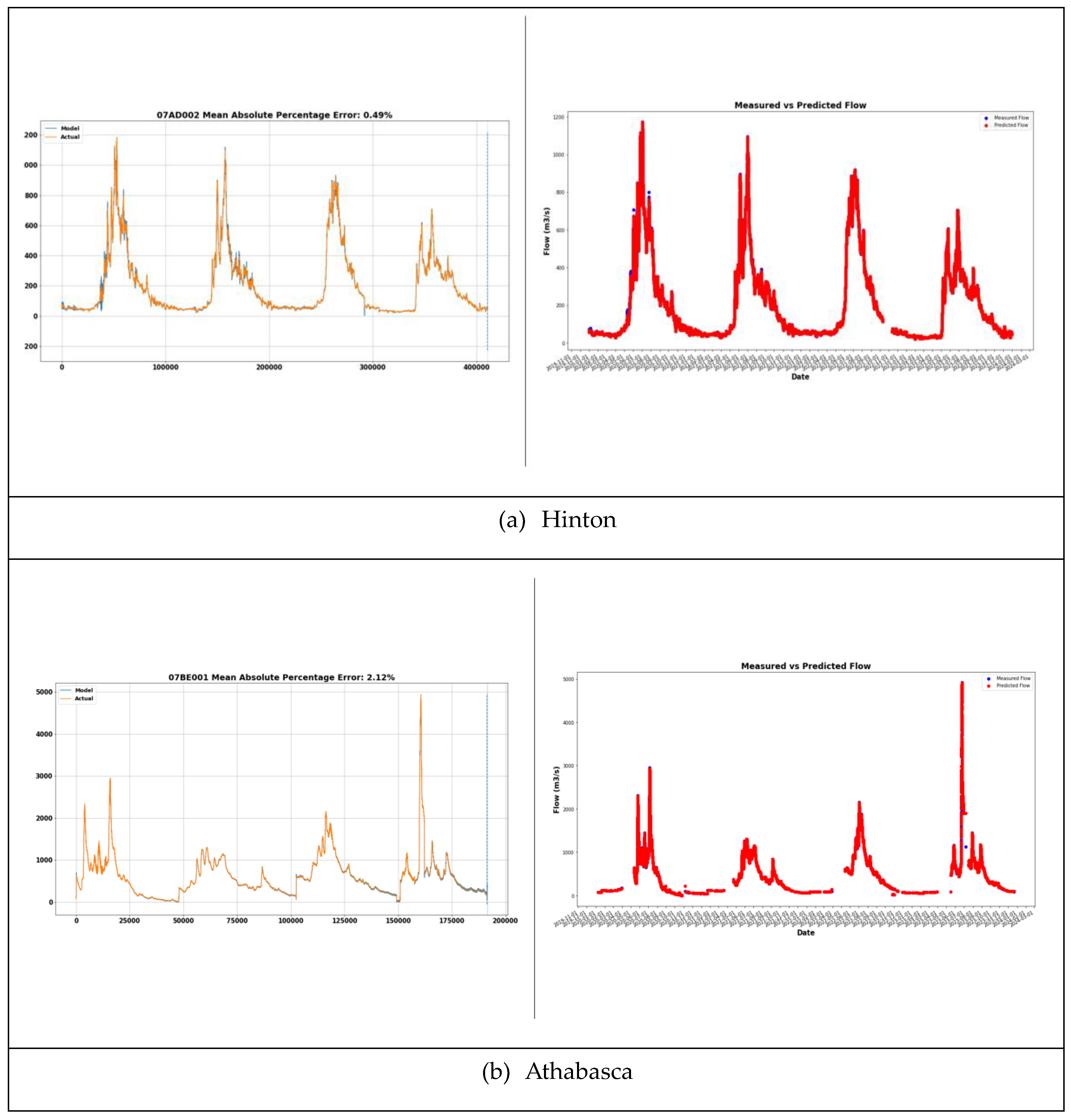

- The statistics on the left represent the Hourly River Flow- Figure 5a–c.

-

Meanwhile, the statistics on the right, Figure 5a–c, represent the correlation using a forest regression to represent classification and regression [20] [14] [29].

- ○

- The scatterplot on the right visually depicts the correlation between two quantitative variables for everyone in the dataset. Each point on the graph represents a flow, with one variable plotted on the horizontal axis and the other on the vertical axis. This clear, intuitive representation swiftly comprehends the variables' interdependence [20].

- ○

- The figures on the right exemplify a blue scatterplot displaying the data from the CSV files. The measured flow (from input data or file) is displayed on the horizontal axis, and the predicted values calculated by the linear regression model are displayed on the vertical axis colored in blue [20].

- ○

- A scatterplot can provide valuable insights into the relationship between two variables.

- ○

- Statistical measures such as the coefficient of determination ("R square") are used further to assess the degree of association between the variables. Typically, a correlation coefficient greater than 0.7 indicates a strong relationship. These tools enable us to analyze the quantitative variables displayed in the scatterplot and better understand their relationship [20].

- ○

- The coefficient of determination equation (7) is based on means and standard deviations, so it is not robust to outliers; it is strongly affected by extreme observations. These parameters are sometimes called influential observations because they strongly impact the correlation coefficient [29].

- ○

- The root mean square error (RMSE) was used to evaluate the goodness of fit of the model, so it is not sensitive to outliers due to extreme observations.

4. Results and Discussion

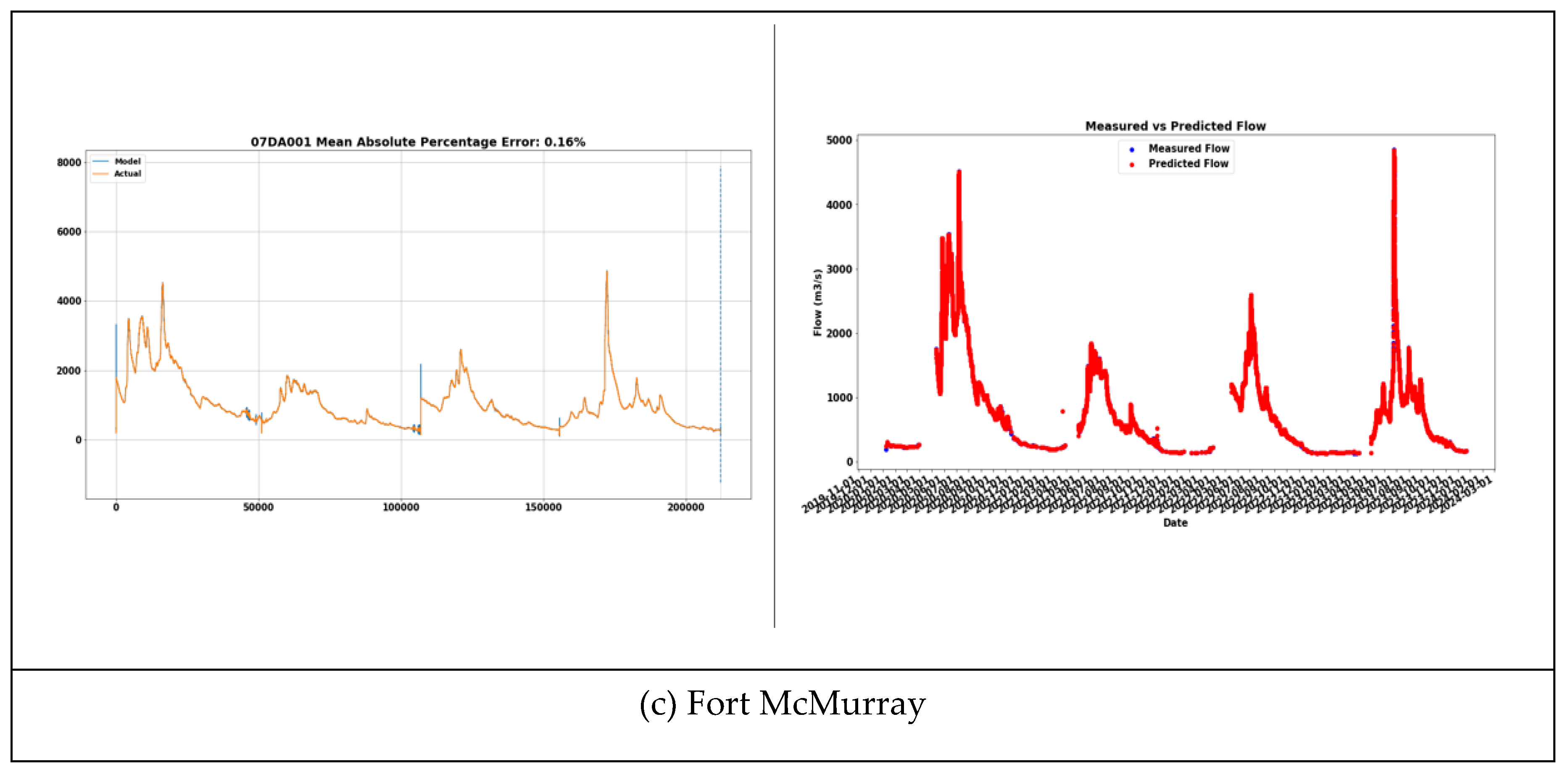

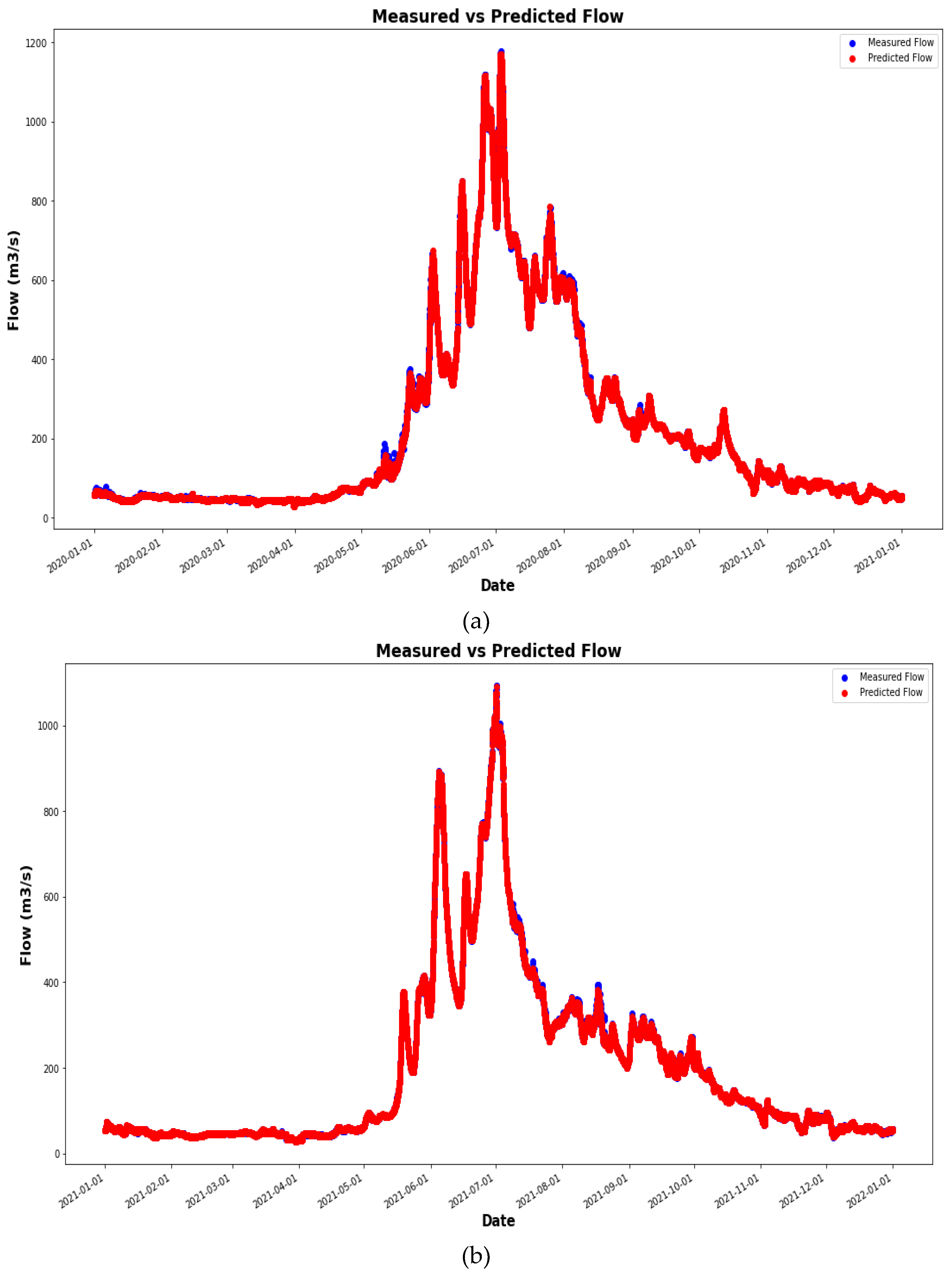

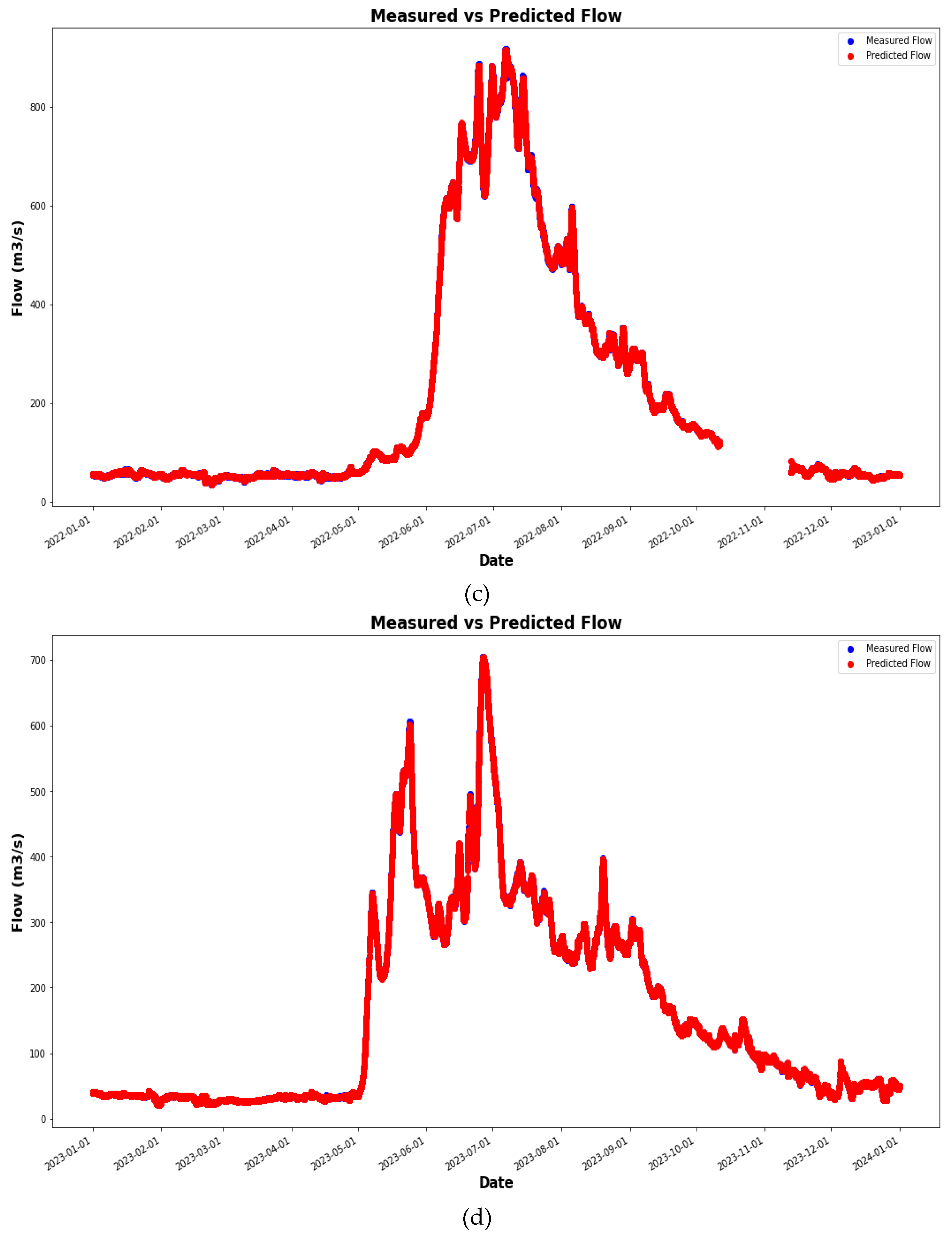

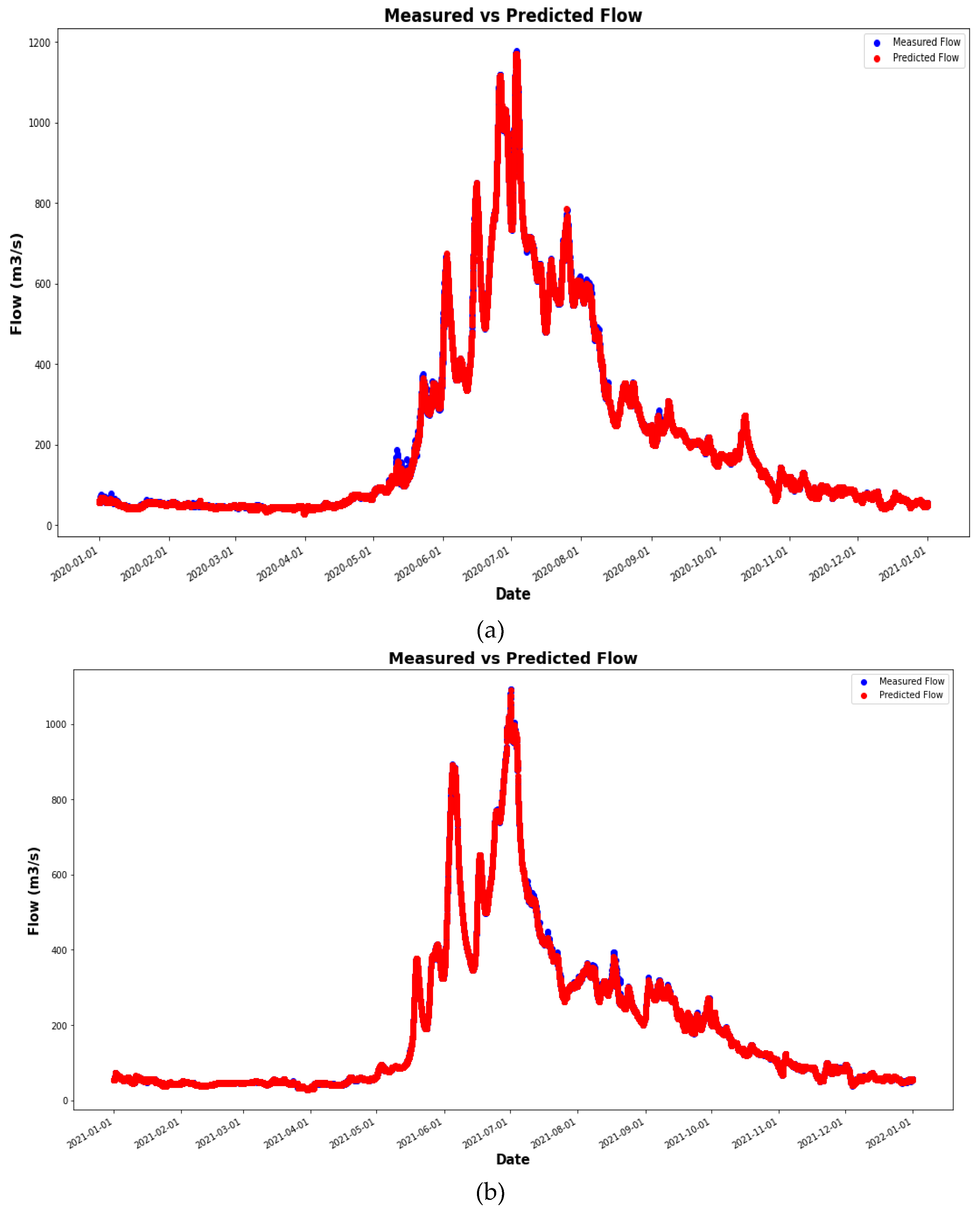

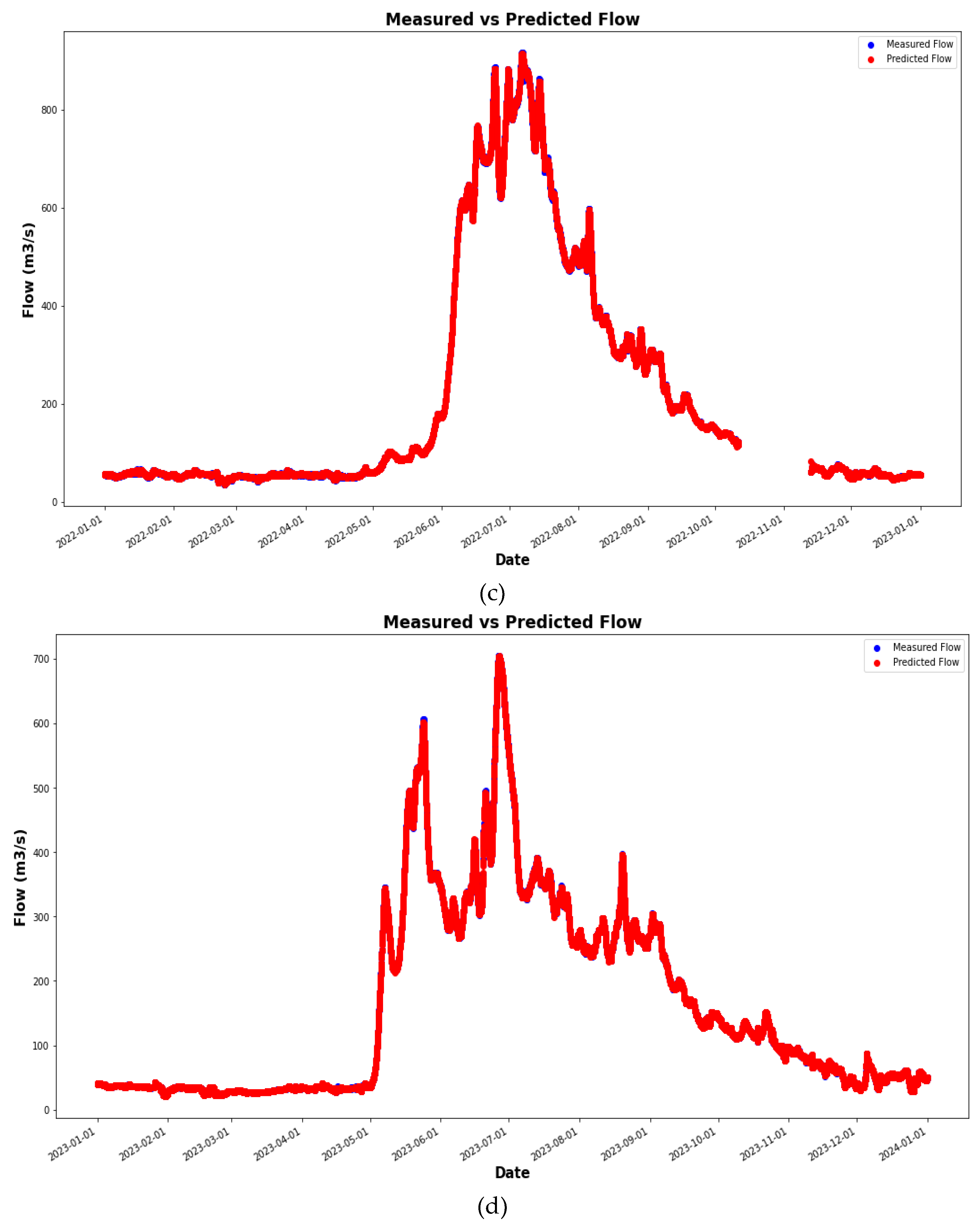

4.1. Comparison of the Simulation Results with Observed Data

| Metrics | Observed Values |

|---|---|

| Time taken to build a model (seconds) | 57.40625 |

| Window | 7 |

| Mean absolute error(equation (1)) | 0.628 |

| Slen | 24 |

| Exponential Smoothing Coefficients | Alpha=0.3 Alpha= 0.05 |

| Coefficients | Alpha = 1 Beta = 1 Gamma = 1 |

| Mean Absolute Percentage Error | 0.49% |

| Regression score function | 0.9999291031812022 |

| Metrics | Observed Values |

|---|---|

| Time taken to build a model (seconds) | 733.359375 |

| Window | 7 |

| Mean absolute error (equation (1)) | 2.161 |

| Slen | 24 |

| Exponential Smoothing Coefficients | Alpha=0.3 Alpha= 0.05 |

| Coefficients | Alpha = 0.5 Beta = 0.1 Gamma = 0.1 |

| Mean Absolute Percentage Error | 2.12% |

| Regression score function | 0.9997655049450087 |

| Metrics | Observed Values |

|---|---|

| Time taken to build a model (seconds) | 589.203125 |

| Window | 7 |

| Mean absolute error (equation (1)) | 1.4302906473354215 |

| Slen | 24 |

| Exponential Smoothing Coefficients | Alpha=0.3 Alpha= 0.05 |

| Coefficients | Alpha = 1 Beta = 1 Gamma = 1 |

| Mean Absolute Percentage Error | 0.16% |

| Regression score function | 0.999 |

4.2. Simulation Results with Observed Data

4.3. Discussion (Limitations)

5. Conclusions

- Limited data availability and how the stations report the data, as explained in section 4.3.

- Those models can be computationally demanding. Therefore, providing user-friendly predictive models is essential for ensuring that individuals can easily interpret and utilize the forecasts generated by AI systems.

- Designing intuitive interfaces and clear visualizations for predictive models is crucial for enabling users with varying technical expertise to interact effectively with the models. By simplifying the user experience and presenting information user-friendly, individuals without a technical background can still benefit from the insights provided by the models. This approach reduces the complexity of the models and minimizes the computational resources required for their operation. Ultimately, creating more simplistic interfaces can help lower the barriers to entry for end-users and enhance the accessibility and usability of predictive models across different domains.

- Developing a universal method for transferring regionalization parameters requires variability in catchment characteristics across different sites. Researchers can better categorize and assign regionalization parameters based on standard features shared among catchments by creating a set of classes representing watershed characteristics. This approach can help standardize the regionalization process and improve the consistency of outcomes when applying regionalization methods to diverse sites. Utilizing advanced AI techniques, such as machine learning algorithms, can assist in identifying patterns and relationships within the data to develop a more robust and transferable method for regionalization parameter transfer.

- Standardizing calibration and validation dataset selection is fundamental in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of predictive models, especially in the context of hydrology in cold climates. The choice of calibration and validation datasets can significantly impact model outcomes, and using time-dependent inputs during calibration can introduce bias. Various data-splitting methods can help achieve temporal and spatial representativeness, but specific guidelines or standards for modeling hydrology in ungauged catchments in cold climates are lacking.

References

- J. Vörösmarty et al, "Global Water Resources: Vulnerability from Climate Change and Population Growth.," Science 289,284-288(2000). [CrossRef]

- N. K. Shrestha, X. N. K. Shrestha, X. Du and J. Wang, "Assessing climate change impacts on fresh water resources of the Athabasca River Basin, Canada," vol. Volumes 601–602, pp. Pages 425-440, December 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, S. H. Wang, S. Song, Z. Gengxi and A. O. Olusola, "Predicting daily streamflow with a novel multi-regime switching ARIMA-MS-GARCH model," pp. 47,p.101374, June 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. K. S. N. A. D. M. W. M. T. &. B. S. Wang, "Modelling Watershed and River Basin Processes in Cold Climate Regions: A Review. Water.," 2021.

- E. B. Wegayehu and F. B. Muluneh, "Short-Term Daily Univariate Streamflow Forecasting Using Deep Learning Models," vol. vol. 2022(Computational Algorithms for Climatological and Hydrological Applications):21, February 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Junye, N. K. W. Junye, N. K. Shrestha,. M. Aghaj, T. W. Meshesha and S. N. Bhanja, "Wang, Junye, Narayan Kumar Shrestha, Mojtaba Aghajani Delavar, Tesfa Worku Meshesha and Soumendra Nath Bhanja. “Modelling Watershed and River Basin Processes in Cold Climate Regions: A Review.”," vol. Water (2021).

- X. Yu, Y. X. Yu, Y. Wang, L. Wu, G. Chen, L. Wang and H. Qin, "Comparison of support vector regression and extreme gradient boosting for decomposition-based data-driven 10-day streamflow forecasting," Journal of Hydrology, vol. Volume 582, March 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang and M. A. Delavar, "Modelling phytoremediation: Concepts, methods, challenges, and perspectives.," Soil & Environmental Health (2024):, no. 100062.

- K. Taereem, T. K. Taereem, T. Yang, S. Gao, L. Zhang, Z. Ding, X. Wen, J. J. Gourley and. Y. Hong, ""Can artificial intelligence and data-driven machine learning models match or even replace process-driven hydrologic models for streamflow simulation?," : A case study of four watersheds with different hydro-climatic regions across the CONUS." Journal of Hydrology 598 (2021): 126423., 2021.

- Q. Zhang, F. Q. Zhang, F. Zhang, T. Erfani and L. Zhu, "Bagged stepwise cluster analysis for probabilistic river flow prediction," Vols. Volume 625, Part A, October 2023, 129995. [CrossRef]

- B. Alizadeh, A. G. B. Alizadeh, A. G. Bafati, H. Kamangir, Y. Zhang, D. B. Wright and K. J. Franz, "Bagged stepwise for streamflow predictin.," Journal of Hydrology, Vols. 601,126526, 2021.

- F. Liu, M. F. Liu, M. Cai, L. Wang and Y. Lu, "An Ensemble Model Based on Adaptive Noise Reducer and Over-Fitting Prevention LSTM for Multivariate Time Series Forecasting," Vols. 2169-3536, 21 February 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Feng, K. D. Feng, K. Fang and C. Shen, "Enhancing Streamflow Forecast and Extracting InsightsUsing Long-Short Term Memory Networks With DataIntegration at Continental Scales," Water Resource Research. [CrossRef]

- H. Tao, A. H. Tao, A. Sani I, A. M. Al-Areeq, F. Tangang, S. Samantaray, A. Sahoo and H. Valadares, "Hybridized artificial intelligence models with nature-inspired algorithms for river flow modeling:," A comprehensive review, assessment, and possible future research directions." Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, no. 129(2024), 107559.

- G. E. Box, G. M. G. E. Box, G. M. Jenkins, G. C. Reinsel and G. M. Ljung, Time Series Analysis:Forecasting and Control, Hoboken, New Jersey: 5th Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2016.

- Z. M. Yaseena, S. O. Z. M. Yaseena, S. O. Sulaiman, D. C. Ravinesh and C. Kwok-Wing, "Journal of Hydrology," An enhanced extreme learning machine model for river flow forecasting:State-of-the-art, practical applications in water resource engineering area and future research direction, Received 23 August 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Holmes, T. A. T. L. Holmes, T. A. Stadnyk, M. Asadzadeh and J. J. Gibson, "Variability in flow and tracer-based performance metric sensitivities reveal regional differences in dominant hydrological processes across the Athabasca River basin,," Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, vol. 41, no. ISSN 2214-5818, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Al-Juboori and A. Guven, "(2016). A stepwise model to predict monthly streamflow. Journal of Hydrology, 543, 283-292.". [CrossRef]

- Z. MS, E. Ghaderpour , H. Dastour , B. Farjad , A. Gupta , H. Eum, G. Achari and Q. Hassan , " Long Term Trend Analysis of River Flow and Climate in Northern Canada. Hydrology. 2022; 9(11):197.,". [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen and S. E. Grasby, "Reconstructing river discharge trends from climate variables and prediction of future trends,Journal of Hydrology," ISSN 0022-1694, vol. 511, pp. 267-278. [CrossRef]

- E. Ghaderpour, M. Sherif Zaghloul, H. Dastour, A. Gupta, G. Achari and Q. K. Hassan, "Least-Squares Triple Cross-Wavelet and Multivariate Regression Analyses of Climate and River Flow in the Athabasca River Basin," p. 1883–1900, 12 Oct 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. McKenney, M. Hutchinson, P. Papadopol , K. Lawrence , J. Pedlar , K. Campbell , E. Milewska , R. Hopkinson , D. Price and T. Owen , "Customized spatial climate models for North America. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society," vol. 92(12), pp. pp.1611-1622. [CrossRef]

- E. a. Parks, "Regional Aguatics Monitoring Program," [Online]. Available online: http://www.ramp-alberta.org/ramp.aspx (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- G. o. Alberta, "Alberta River Basins," [Online]. Available online: https://rivers.alberta.ca (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Y. Kashnitsky, "Tpoic 9.Part 1. Time sereis analysis in Python," [Online]. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/code/kashnitsky/topic-9-part-1-time-series-analysis-in-python.

- J. Sun, J. Huang, G. Liu, R. Bai and W. Liu, "(2023). Prediction method for the truck's fault time in open-pit mines based on exponential smoothing neural network. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 18580. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A. Cardoso, J. Marques and N. Simões, "2019, June. Web interface for river hydrodynamics simulation. In 2019 5th Experiment International Conference (exp. at'19)," pp. pp. 278-279.

- Ferdowsi, S. Farzin, , M. Sayed-Farhad and H. Karami, "Hybrid Bat & Particle Swarm Algorithm for optimization of labyrinth spillway based on half & quarter round crest shapes,," ISSN 0955-5986,, vol. 66, pp. Pages 209-217, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Tyralis, G. Papacharalampous and A. Langousis, "A Brief Review of Random Forests for Water Scientists and Practitioners and Their Recent History in Water Resources,". 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Moore, W. I. Notz, and M. A. Fligner, Basic Practice of Statistics 6th Ed.

- Belvederesi, M. S. Zaghloul,, G. Achari, A. Gupta and Q. K. Hassan, "Modelling river flow in cold and ungauged regions: a review of the purposes, methods, and challenges," vol. Published at www.cdnsciencepub.com/er on 21 January 2022., Received 6 May 2021. Accepted 21 October 2021. 21 January. [CrossRef]

- Q. Hassan, I. Ejiagha, A. M.R, ,. A. Gupta, ,. E. Rangelova and A. Dewan, Remote sensing of the local warming Trend in Alberta, Canada during 2001–2020, and its relationship with large-scale atmospheric circulations.Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3441. [CrossRef]

- RMA, L. Goliatt , O. Kisi , S. Trajkovic and S. Shahid , "Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy for Improving Machine Learning Approaches in Streamflow Prediction," Mathematics. 2022, no. 10(16):2971. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Stadnyk and T. L. Holmes, "On the value of isotope-enabled hydrological model calibration," pp. Pages 1525-1538, 2020/07/03. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang, F. Zhang, T. Erfani and L. Zhu, "Bagged stepwise cluster analysis for probabilistic river flow prediction,Journal of Hydrology," Volume 625, Part A,, no. ISSN 0022-1694, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Timoney, "New insights into the spring flood history of the lower Peace and Athabasca Rivers, Northern Canada," vol. Received 2 April 2021; Received in revised form 16 August 2021; Accepted 3 September 2021, no. 0165-232X/© 2021 Published by Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- T. .. Raj , S. Shukla and . S. Sinha, "Design of Weather Forecast System Using R. Alexandra, Cardoso. Alberto , Sá Marques. José Alfeu, Simões. Nuno Eduardo," Web Interface for River Hydrodynamics Simulation, 2019 5th Experiment@ International Conference June 12th.

- X. Kang , L. Xuechun and T. Xintong , "Water Level Prediction Based on SSA-LSTM Model," vol. 2022 7th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Applications, no. 978-1-6654-9584-4/22/, 2022.

- Z. Z. Zizi , M. Mazlina and Y. T. Hoe , "River Water Level Prediction for Flood Risk Assessment using NARX Neural Network," 2022 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Engineering and Technology (IICAIET), no. 978-1-6654-6837-4/22.

- T. H.F., K. M, and V. C, "Time Series Database Preprocessing for Data Mining," no. 978-1-7281-6939-2, June 2020.

- Al-Juboori and A. Guven, "A stepwise model to predict monthly streamflow," 2016. Journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhydrol, no. Civil Engineering Department, Gaziantep University, 27310 Gaziantep, Turkey.

- M. Al-Omary, R. Aljarrah, A. Albatayneh and M. Jaradat, "A Composite Moving Average Algorithm for Predicting Energy in Solar Powered Wireless Sensor Nodes," no. 2021 18th International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD'21), 2021 March.

- S, V. S and R. R, "A Comparative Analysis on Linear Regression and Support Vector Regression," 2016 Online International Conference on Green Engineering and Technologies (IC-GET), no. 978-1-5090-4556-3.

- Vörösmarty, P. Green, J. Salisbury and R. Lammers, "Global Water Resources: Vulnerability from Climate Change and Population Growth. Science 2000,289,284-288". [CrossRef]

- J. V. e. al, "Global Water Resources: Vulnerability from Climate Change and Population Growth," Science 289,284-288(2000). [CrossRef]

| Station ID | Station Name | Latitude | Longitude | Period of Records |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 07AD002 | Hinton | 53.42429000 | -117.56942000 | 2020-2023 |

| 07BE001 | Athabasca | 54.72203000 | -113.28796000 | 2020-2023 |

| 07DA001 | Fort McMurray | 56.78035000 | -111.40219000 | 2020-2023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).