Submitted:

06 September 2024

Posted:

09 September 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Objectives

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Study characteristics:

- For copeptin dosing, studies must have included specific determination of baseline copeptin levels. Another test that will be assessed is represented by the copeptin levels after intravenous infusion of 3% NaCl solution, as well as arginine stimulation test, or other copetin stimulation methods. These mechanisms are meant to achieve a target serum sodium level of approximately 150 mmol/L, corresponding to a serum osmolality of around 300 mOsm/kg.

- Additionally, studies comparing copeptin with other traditional diagnostic methods such as the water deprivation test. This test is usually extended for 8 hours, and followed by desmopressin administration, to assess the urinary response, od ADH. The study should have recorded serum sodium levels ranging from 145 mmol/L to 150 mmol/L and urinary osmolality ranging from 300 mOsm/kg to 1200 mOsm/kg.

2.1.2. Report Characteristics

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Definitions for Data Extraction

2.7. Risk of Bias and Applicability

2.8. Principal Diagnostic Accuracy Measures

2.9. Data Handling for Synthesis of Results

- Standardization of Target Conditions: Definitions for conditions such as CDI, NDI, and PP were standardized using clinical criteria across studies.

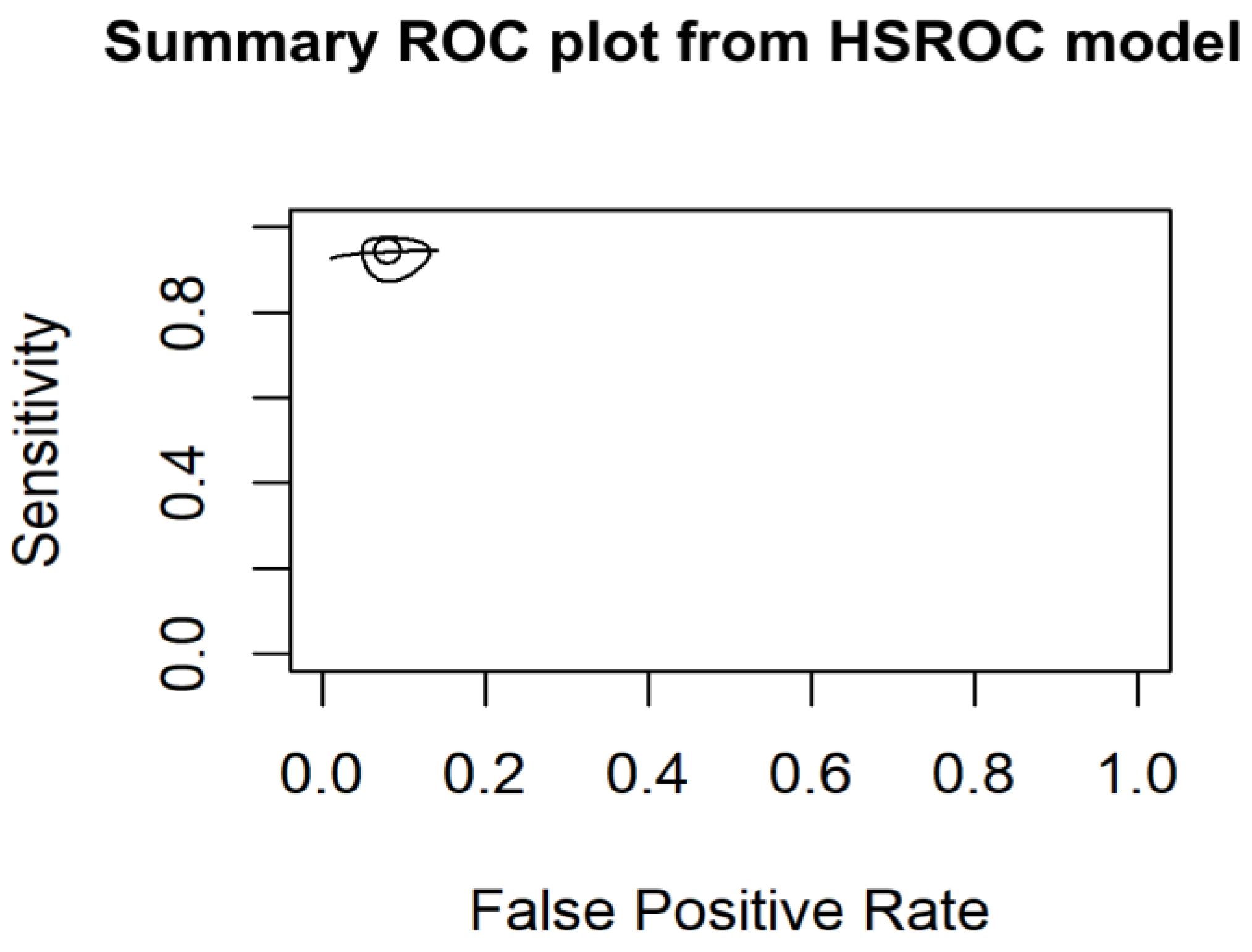

- Harmonization of threshold: Different thresholds for test positivity were harmonized, and subgroup analyses done according to different diagnostic methods. The use of HSROC modeling further allowed us to account for and understand these threshold effects, providing a more nuanced analysis of the diagnostic accuracy across studies.

- Indeterminate results: Clear definitions and sensitivity analyses were used for copeptin levels within a borderline range, and statistical adaptations were done for undefined values, when necessary.

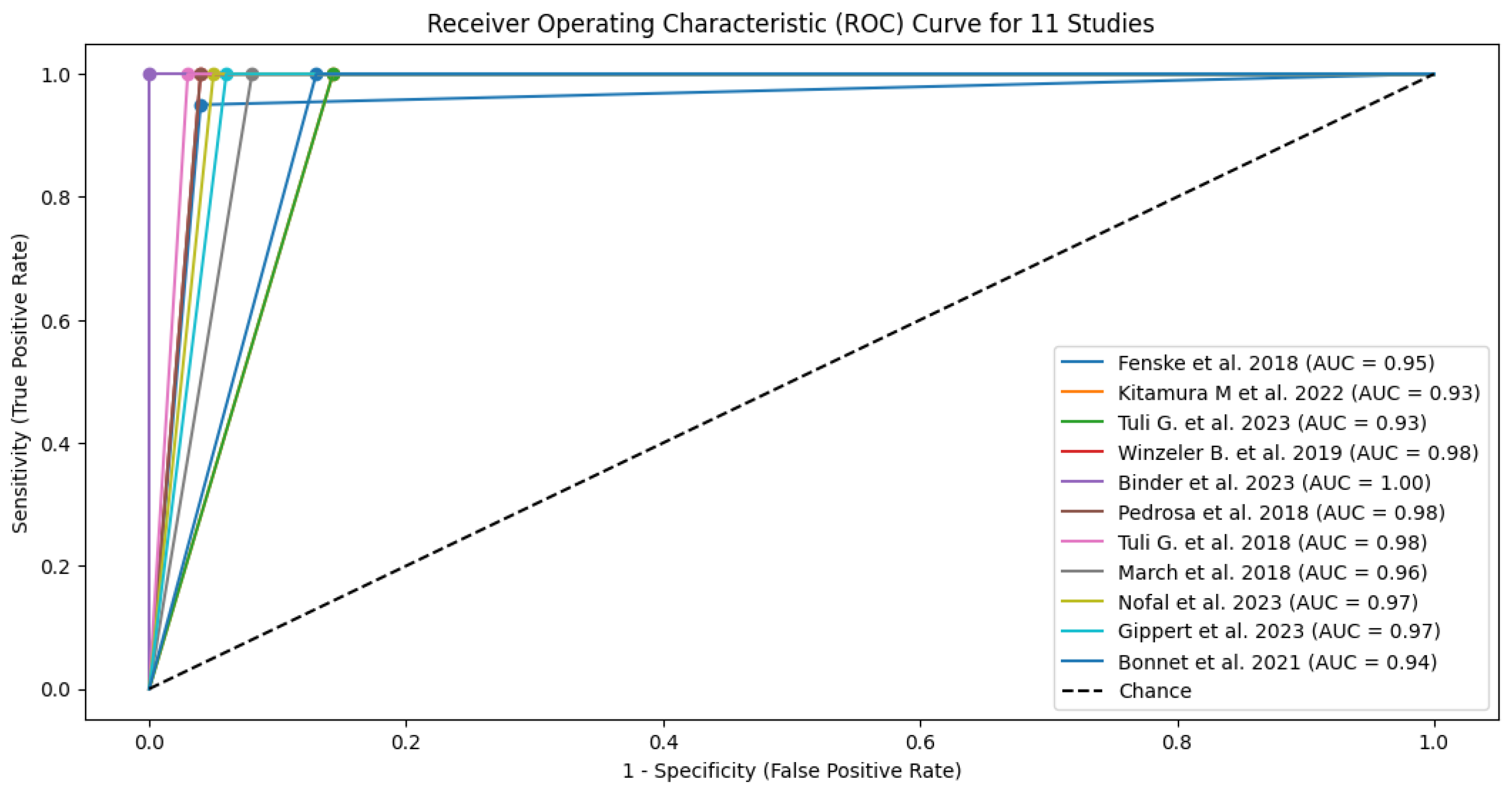

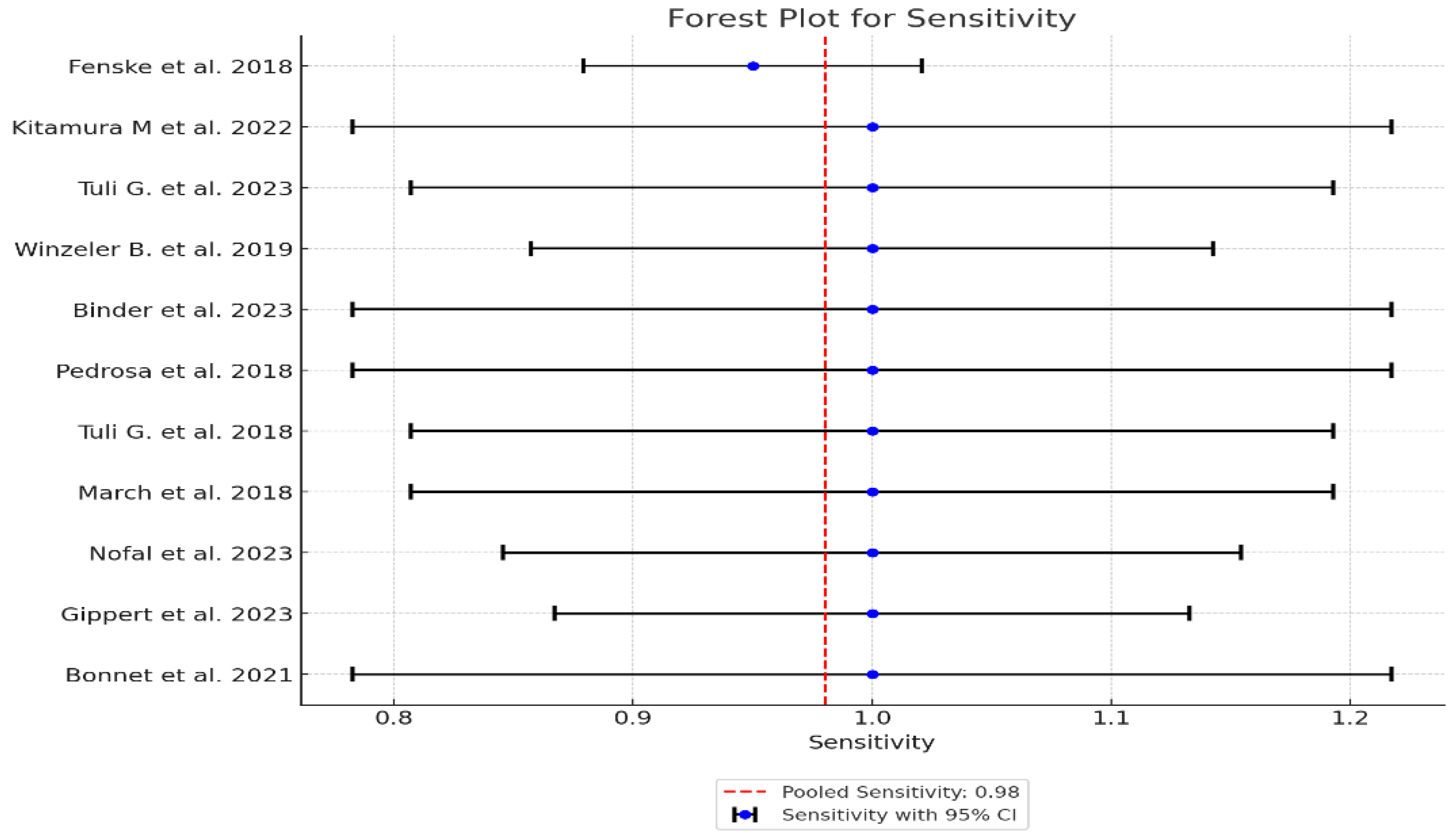

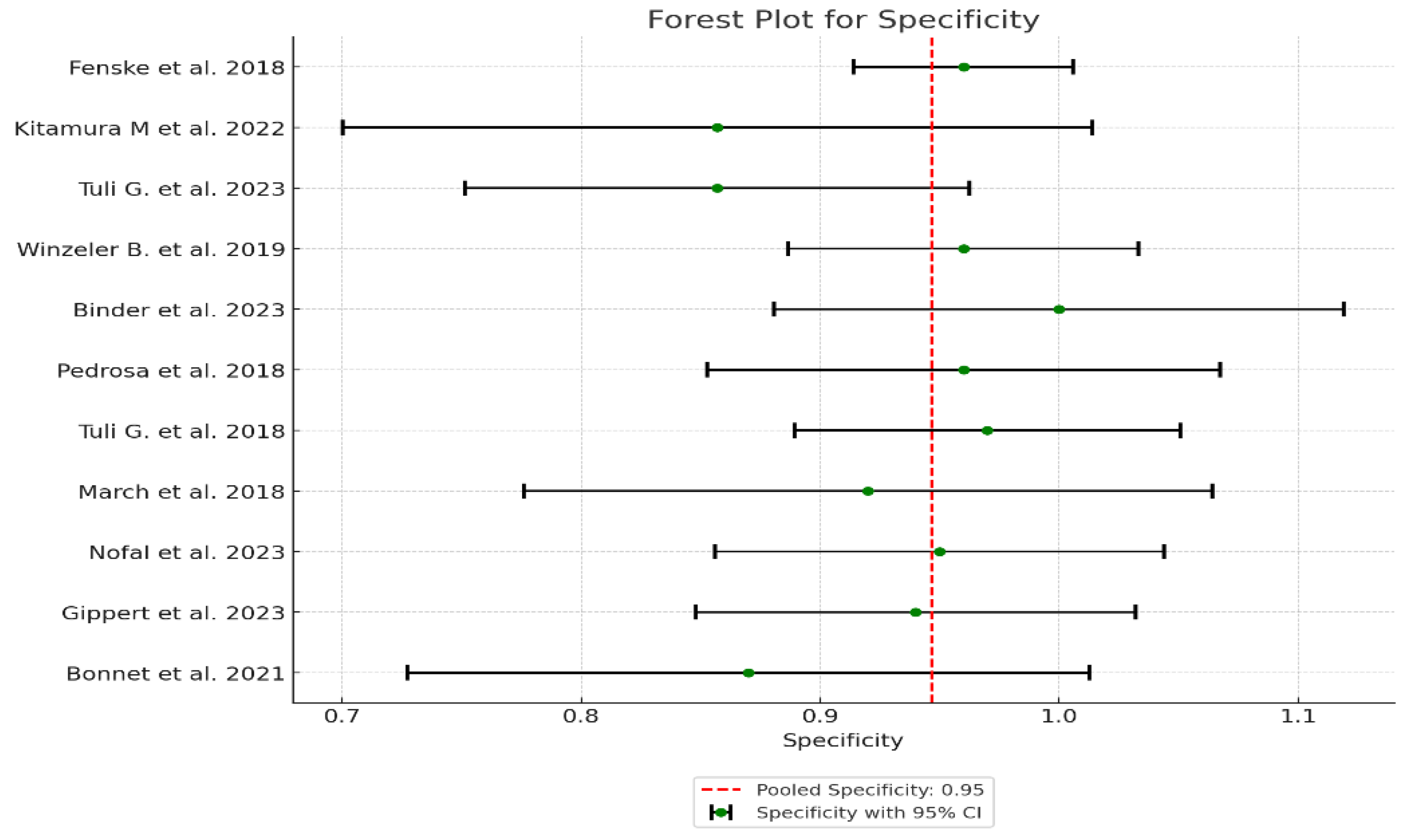

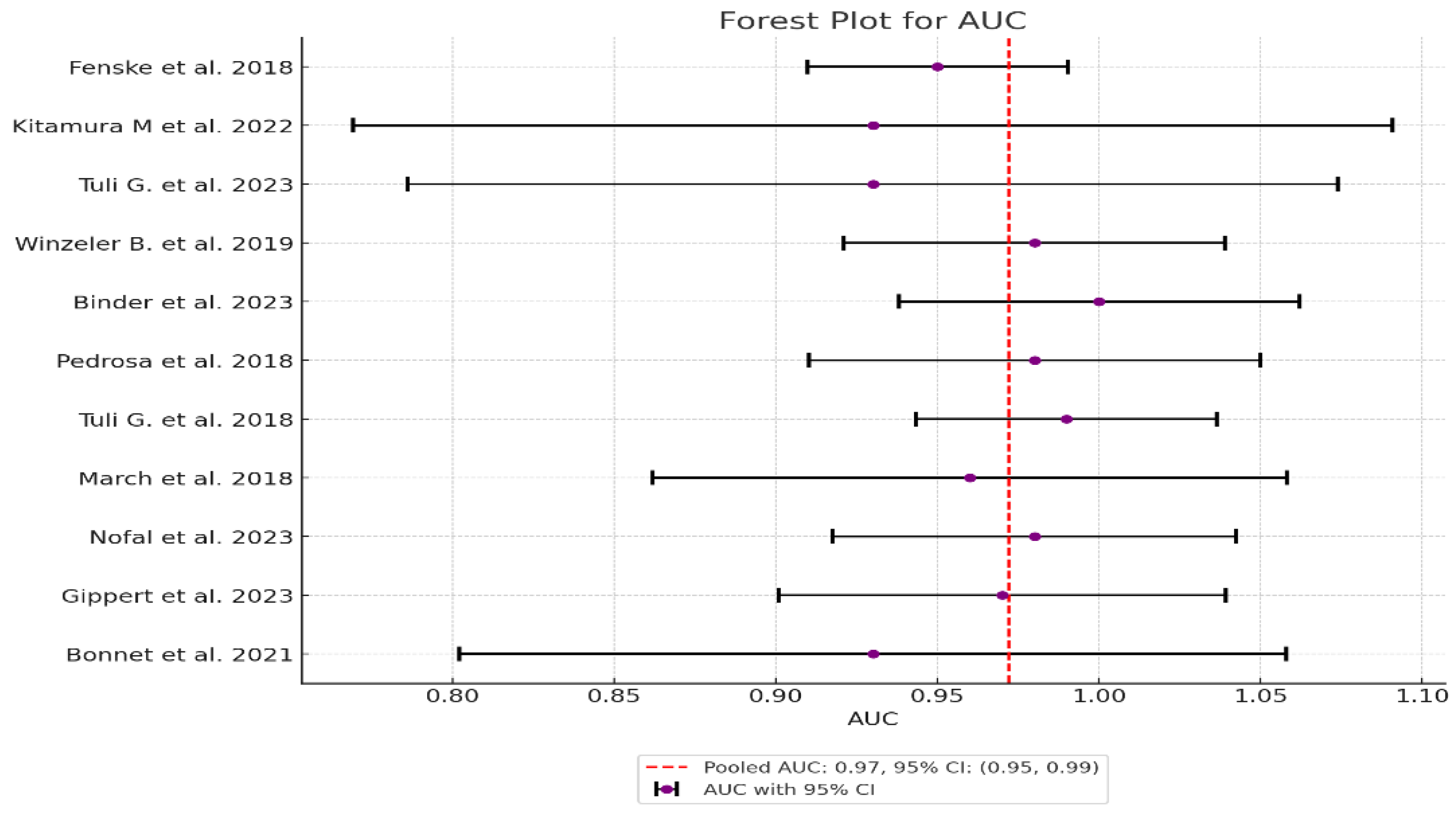

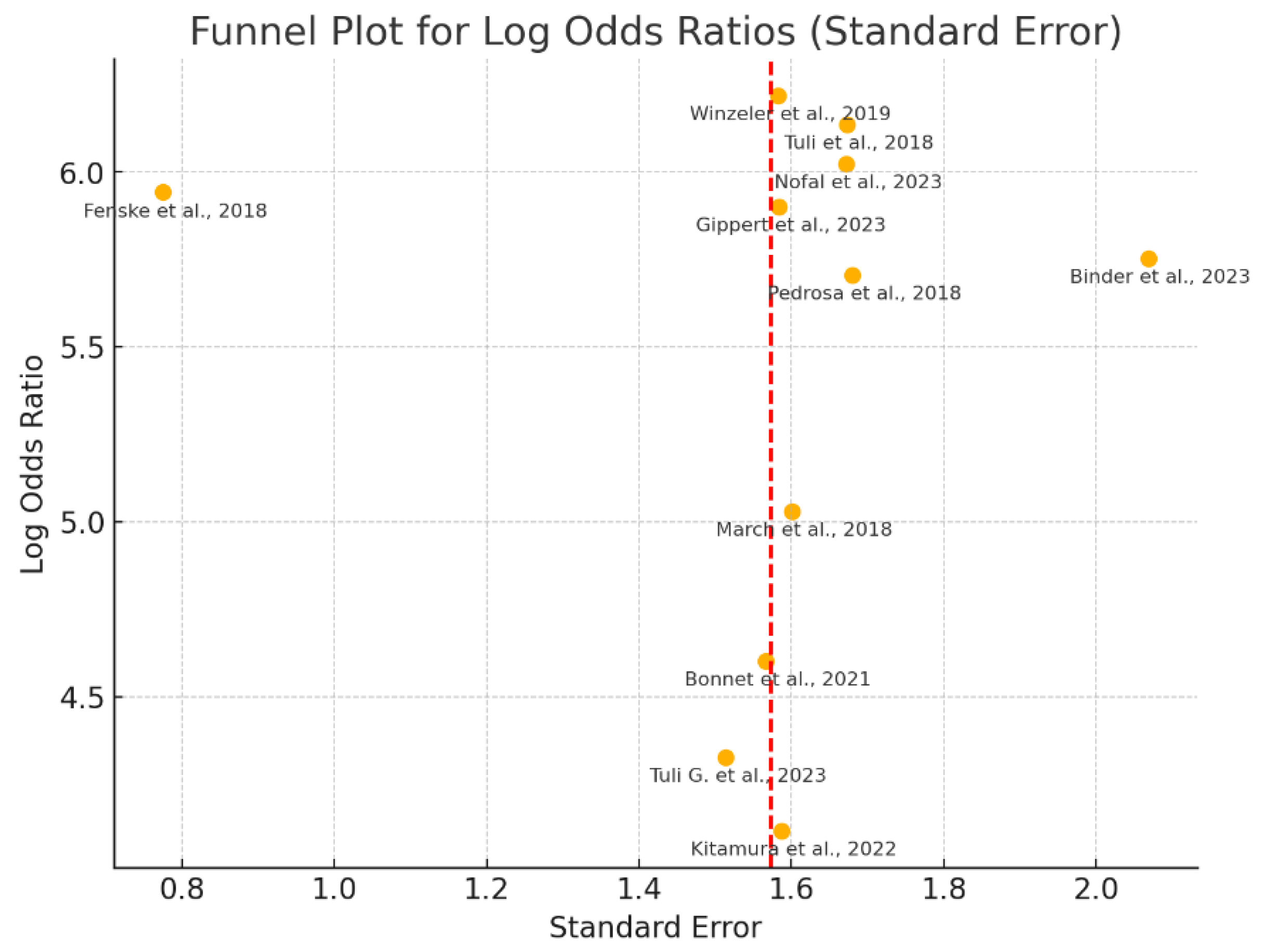

- Meta-Analysis techniques: were carried out with the use of fixed-effects models applied for the assessment of measures of diagnostic accuracy because the studies had shown low heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic, Cochran's Q test and Tau-squared (τ²) test. The statistical analyses were performed following standard meta-analysis protocols, to ensure robust and reliable estimates, using forest plots to visually compare diagnostic accuracy. Furtehrmore, we used HSROC model to assess threshold variability and obtained a deeper insight into the diagnostic accuracy across studies. [7].

2.10. Additional Analyses

3. Results

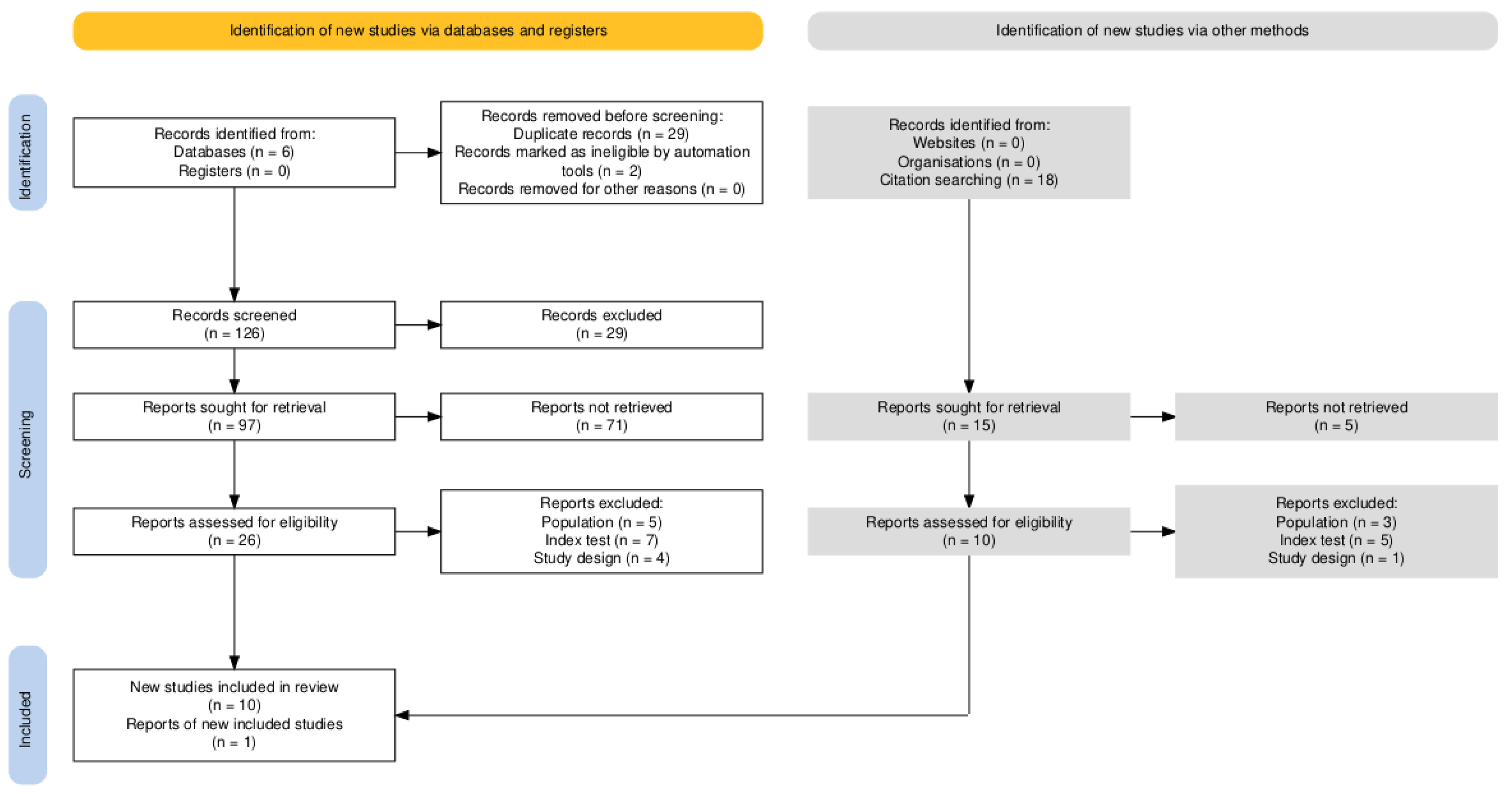

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Quality Assessment and Publication Bias

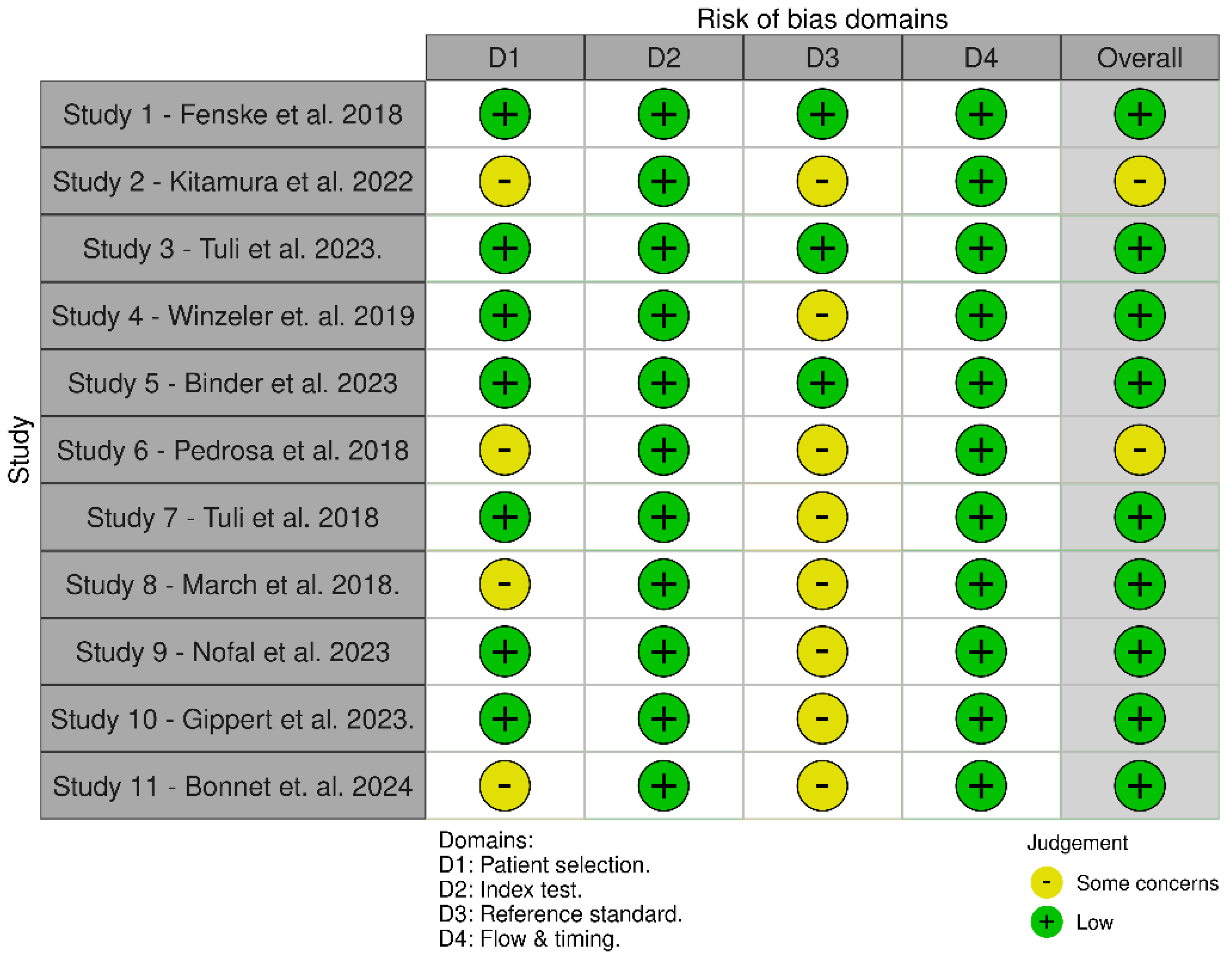

3.3.1. QUADAS-2 Was Used to Assess the Quality of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. It Evaluates the Risk of Bias and Applicability Concerns in Four Key Domains. Detailed Assessment is Available in Appendix C.

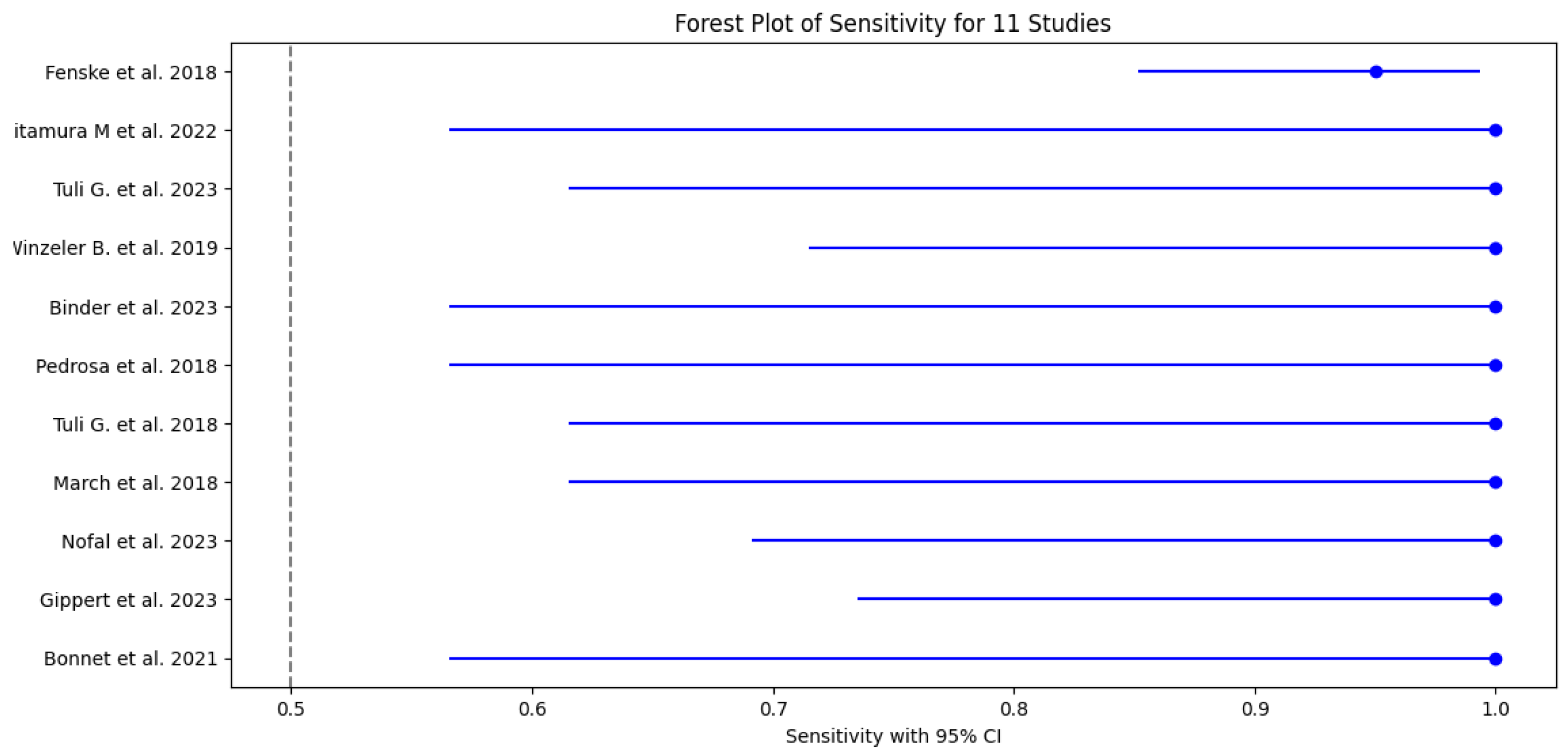

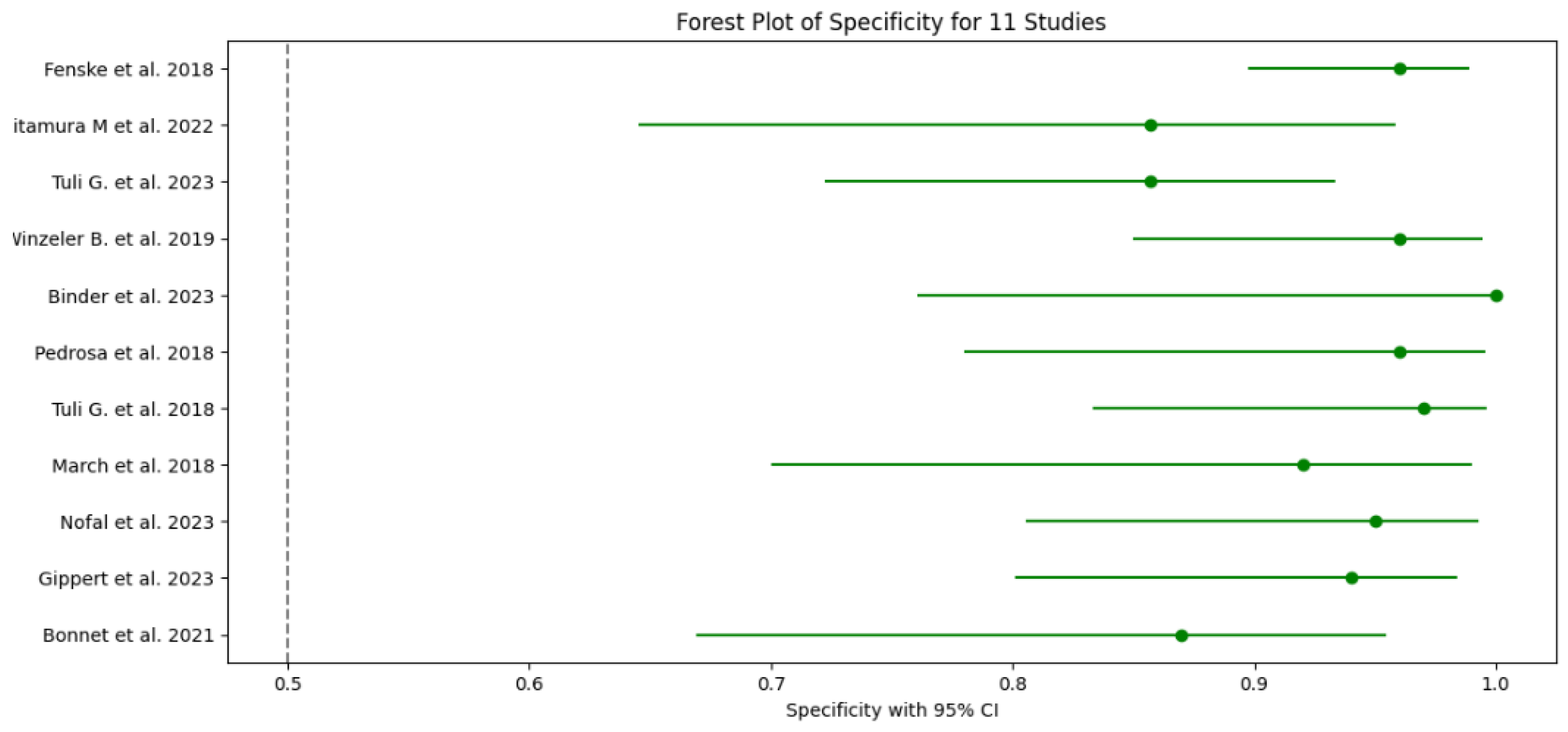

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

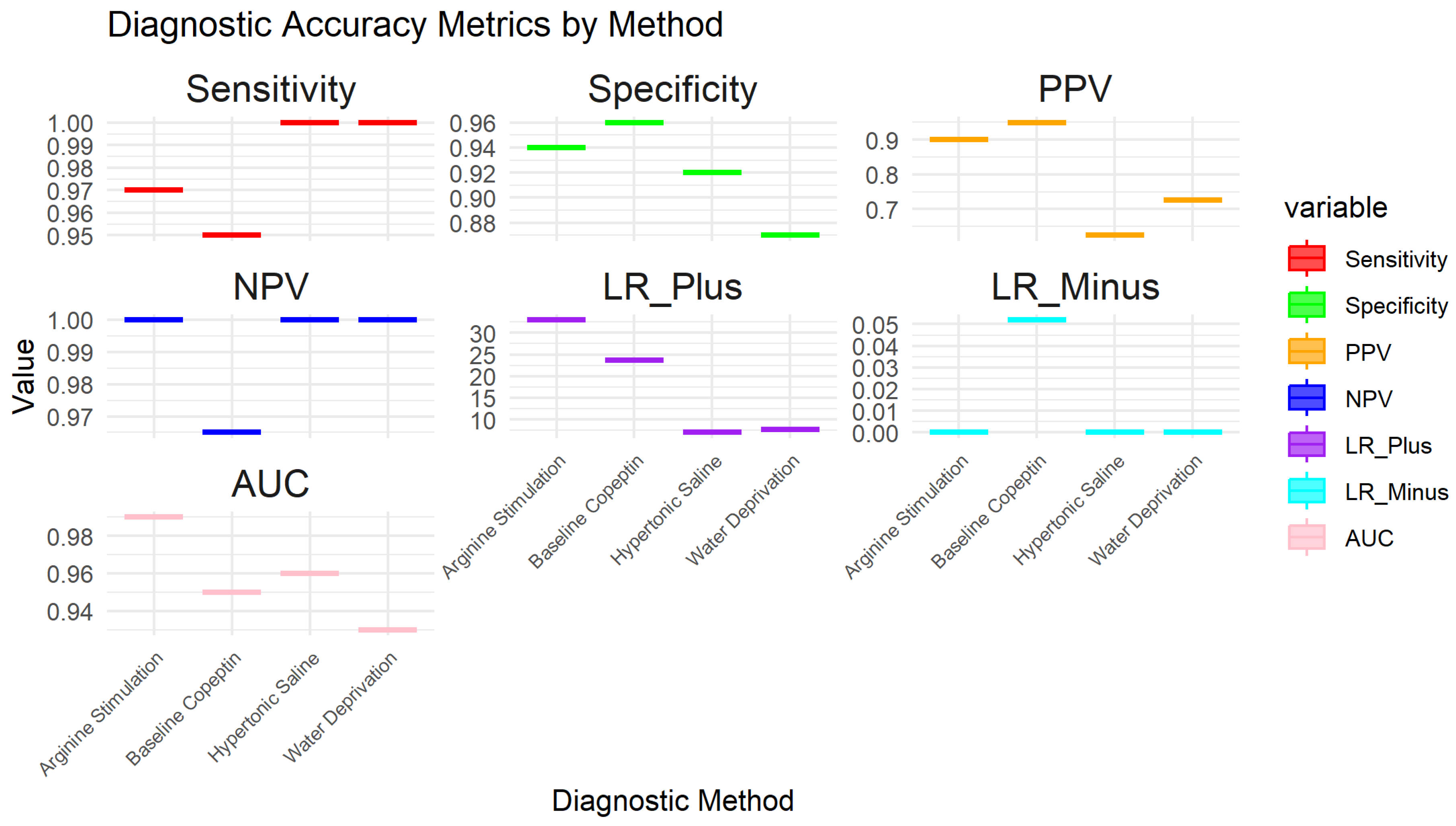

3.5. Test Accuracy and Variability

3.6. Meta-Analysis

3.6.1. HSROC Model Results

3.6.2. Assessment of Heterogeneity

3.6.3. Publication Bias Assessment

3.6.4. Sensitivity Analysis Based on Risk of Bias

3.7. Sensitivity of Sub-Group Analysis for Main Diagnostic Methods

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings:

4.2. Comparison with Previous Studies:

4.3. Clinical Implications:

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | Search String | Limits |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (("Polyuria"[Mesh] OR "Polydipsia"[Mesh] OR "Central Diabetes Insipidus"[Mesh] OR "Primary Polydipsia"[Mesh] OR "Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus"[Mesh]) AND ("Arginine Vasopressin"[Mesh] OR "C-Terminal Provasopressin"[Mesh] OR "Water Deprivation Test"[Mesh] OR "Desmopressin"[Mesh] OR "Copeptin"[Mesh] OR "Baseline Copeptin" OR "Copeptin Stimulation" OR "Copeptin Test" OR "Saline Infusion Test" OR "Arginine Stimulation") AND ("Child"[Mesh] OR "Adolescent"[Mesh]) AND ("Diagnostic Accuracy" OR "Sensitivity" OR "Specificity" OR "ROC" OR "AUC" OR "Predictive Value")) | Publication date from 2018 to 2024, Humans, Children and Adolescents |

| Cochrane Library | ((Polyuria OR Polydipsia OR "Central Diabetes Insipidus" OR "Primary Polydipsia" OR "Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus") AND ("Arginine Vasopressin" OR "C-Terminal Provasopressin" OR "Water Deprivation Test" OR "Desmopressin" OR "Copeptin" OR "Baseline Copeptin" OR "Copeptin Stimulation" OR "Copeptin Test" OR "Saline Infusion Test" OR "Arginine Stimulation") AND (Child OR Adolescent) AND ("Diagnostic Accuracy" OR "Sensitivity" OR "Specificity" OR "ROC" OR "AUC" OR "Predictive Value")) | Publication date from 2018 to 2024, Trials, Reviews |

| Web of Science | (TS=(Polyuria OR Polydipsia OR "Central Diabetes Insipidus" OR "Primary Polydipsia" OR "Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus") AND TS=("Arginine Vasopressin" OR "C-Terminal Provasopressin" OR "Water Deprivation Test" OR "Desmopressin" OR "Copeptin" OR "Baseline Copeptin" OR "Copeptin Stimulation" OR "Copeptin Test" OR "Saline Infusion Test" OR "Arginine Stimulation") AND TS=(Child OR Adolescent) AND TS=("Diagnostic Accuracy" OR "Sensitivity" OR "Specificity" OR "ROC" OR "AUC" OR "Predictive Value")) | Timespan: 2018-2024, Indexes: SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, ESCI |

| ScienceDirect | Search String 1: (Polyuria OR Polydipsia OR "Central Diabetes Insipidus" OR "Primary Polydipsia") AND (Copeptin OR "Arginine Vasopressin'' OR ''Water deprivation test'') AND (Child OR Adolescent)Search String 2: ("Water Deprivation Test" OR Desmopressin OR "Copeptin Stimulation" OR "Saline Infusion Test") AND ("Central Diabetes Insipidus" OR ''Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus'' OR "Primary Polydipsia") AND (Child OR Adolescent) | Date: 2018-2024, Article type: Research Articles |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(Polyuria OR Polydipsia OR "Central Diabetes Insipidus" OR "Primary Polydipsia" OR "Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY("Arginine Vasopressin" OR "C-Terminal Provasopressin" OR "Water Deprivation Test" OR "Desmopressin" OR "Copeptin" OR "Baseline Copeptin" OR "Copeptin Stimulation" OR "Copeptin Test" OR "Saline Infusion Test" OR "Arginine Stimulation") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Child OR Adolescent) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY("Diagnostic Accuracy" OR "Sensitivity" OR "Specificity" OR "ROC" OR "AUC" OR "Predictive Value") | Limits:Date: 2018-2024, Document type: Article; Humans; Child |

| Google Scholar | (Polyuria OR Polydipsia OR "Central Diabetes Insipidus" OR ‘’ Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus’’ OR "Primary Polydipsia") AND (Copeptin OR "Arginine Vasopressin" OR "Water deprivation test") AND (Child OR Adolescent) AND (Diagnosis OR "Diagnostic Accuracy" OR Sensitivity OR Specificity OR "ROC Curve") -treatment -meta-analysis -case-report | Date: 2018-2024 |

Appendix B. Independent Read and Assessment of Quality Using QUADAS-2

Appendix C

| Study | Patient Selection (Risk of Bias) | Index Test (Risk of Bias) | Reference Standard (Risk of Bias) | Flow and Timing (Risk of Bias) | Overall Summary of Bias | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fenske et al. 2018 | Low (some concerns on applicability) | Low | Low (minor subjectivity) | Low | Low overall risk | The study involved patients from tertiary centers, which may not represent the general population. |

| 2. Kitamura et al. 2022 | Moderate (retrospective, single-center) | Low to Moderate (potential blinding issues) | Moderate (expert consensus) | Low | Moderate overall risk | Retrospective design and single-center setting increase the selection bias; possible lack of blinding. |

| 3. Tuli et al. 2023 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low overall risk | Prospective design with a well-defined patient population, reducing bias. |

| 4. Winzeler et al. 2019 | Low (concerns about applicability to pediatric) | Low | Low to Moderate (subjectivity) | Low | Low overall risk | The study is focused on adults, limiting applicability to pediatric populations. |

| 5. Binder et al. 2023 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low overall risk | Clear protocol and prospective design contribute to low bias across domains. |

| 6. Pedrosa et al. 2018 | Moderate (retrospective, single-center) | Low | Moderate (subjectivity) | Low | Moderate overall risk | Retrospective design and reliance on expert opinion without blinding introduce moderate bias. |

| 7. Tuli et al. 2018 | Low | Low | Moderate (subjectivity) | Low | Low overall risk | Prospective study with rigorous methods, though expert consensus introduces some subjectivity. |

| 8. March et al. 2018 | Low to Moderate (single-center setting) | Low | Moderate (subjectivity) | Low | Low to Moderate overall risk | Single-center design may affect generalizability, and expert consensus introduces subjectivity. |

| 9. Nofal et al. 2023 | Low | Low | Moderate (subjectivity) | Low | Low overall risk | Multicenter design reduces selection bias, but expert consensus may introduce some subjectivity. |

| 10. Gippert et al. 2023 | Low | Low | Moderate (subjectivity) | Low | Low overall risk | Consistent methods across centers, though reliance on expert consensus introduces moderate bias. |

| 11. Bonnet et al. 2024 | Low to Moderate (single-center setting) | Low | Moderate (subjectivity) | Low | Low to Moderate overall risk | Single-center design could limit generalizability; expert consensus introduces moderate bias. |

References

- Gubbi S, H.-S. F. K. C. et al. Diagnostic Testing for Diabetes Insipidus. [Updated 2022 Nov 28]. . Endotext. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537591/ (accessed 2024-03-28).

- Yoshimura, M.; Conway-Campbell, B.; Ueta, Y. Arginine Vasopressin: Direct and Indirect Action on Metabolism. Peptides (N.Y.) 2021, 142, 170555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenske, W.; Quinkler, M.; Lorenz, D.; Zopf, K.; Haagen, U.; Papassotiriou, J.; Pfeiffer, A. F. H.; Fassnacht, M.; Störk, S.; Allolio, B. Copeptin in the Differential Diagnosis of the Polydipsia-Polyuria Syndrome—Revisiting the Direct and Indirect Water Deprivation Tests. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenske, W.; Refardt, J.; Chifu, I.; Schnyder, I.; Winzeler, B.; Drummond, J.; Ribeiro-Oliveira, A.; Drescher, T.; Bilz, S.; Vogt, D. R.; Malzahn, U.; Kroiss, M.; Christ, E.; Henzen, C.; Fischli, S.; Tönjes, A.; Mueller, B.; Schopohl, J.; Flitsch, J.; Brabant, G.; Fassnacht, M.; Christ-Crain, M. A Copeptin-Based Approach in the Diagnosis of Diabetes Insipidus. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 379, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driano, J. E.; Lteif, A. N.; Creo, A. L. Vasopressin-Dependent Disorders: What Is New in Children? Pediatrics 2021, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, D.; Ma, Y.; Cheng, J.; Qiu, L.; Chen, S.; Cheng, X. Diagnostic Accuracy of Copeptin in the Differential Diagnosis of Patients With Diabetes Insipidus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocrine Practice 2023, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks JJ; Bossuyt PM; Leeflang MM, T.; akwoingi Y. Chapter PDFs of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy (v2.0) | Cochrane Training. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook-diagnostic-test-accuracy/current (accessed 2024-08-02).

- McInnes, M. D. F.; Moher, D.; Thombs, B. D.; McGrath, T. A.; Bossuyt, P. M.; Clifford, T.; Cohen, J. F.; Deeks, J. J.; Gatsonis, C.; Hooft, L.; Hunt, H. A.; Hyde, C. J.; Korevaar, D. A.; Leeflang, M. M. G.; Macaskill, P.; Reitsma, J. B.; Rodin, R.; Rutjes, A. W. S.; Salameh, J. P.; Stevens, A.; Takwoingi, Y.; Tonelli, M.; Weeks, L.; Whiting, P.; Willis, B. H. Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies The PRISMA-DTA Statement. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 2018, 319, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, J.-P.; Bossuyt, P. M.; McGrath, T. A.; Thombs, B. D.; Hyde, C. J.; Macaskill, P.; Deeks, J. J.; Leeflang, M.; Korevaar, D. A.; Whiting, P.; Takwoingi, Y.; Reitsma, J. B.; Cohen, J. F.; Frank, R. A.; Hunt, H. A.; Hooft, L.; Rutjes, A. W. S.; Willis, B. H.; Gatsonis, C.; Levis, B.; Moher, D.; McInnes, M. D. F. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies (PRISMA-DTA): Explanation, Elaboration, and Checklist. BMJ 2020, m2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenske, W.; Refardt, J.; Chifu, I.; Schnyder, I.; Winzeler, B.; Drummond, J.; Ribeiro-Oliveira, A.; Drescher, T.; Bilz, S.; Vogt, D. R.; Malzahn, U.; Kroiss, M.; Christ, E.; Henzen, C.; Fischli, S.; Tönjes, A.; Mueller, B.; Schopohl, J.; Flitsch, J.; Brabant, G.; Fassnacht, M.; Christ-Crain, M. A Copeptin-Based Approach in the Diagnosis of Diabetes Insipidus. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 379, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J.; McKenzie, J. E.; Bossuyt, P. M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T. C.; Mulrow, C. D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J. M.; Akl, E. A.; Brennan, S. E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J. M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M. M.; Li, T.; Loder, E. W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; McGuinness, L. A.; Stewart, L. A.; Thomas, J.; Tricco, A. C.; Welch, V. A.; Whiting, P.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, M. D. F.; Moher, D.; Thombs, B. D.; McGrath, T. A.; Bossuyt, P. M.; Clifford, T.; Cohen, J. F.; Deeks, J. J.; Gatsonis, C.; Hooft, L.; Hunt, H. A.; Hyde, C. J.; Korevaar, D. A.; Leeflang, M. M. G.; Macaskill, P.; Reitsma, J. B.; Rodin, R.; Rutjes, A. W. S.; Salameh, J.-P.; Stevens, A.; Takwoingi, Y.; Tonelli, M.; Weeks, L.; Whiting, P.; Willis, B. H. Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies. JAMA 2018, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen, M. L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A. P.; Moher, D.; Page, M. J.; Koffel, J. B.; Blunt, H.; Brigham, T.; Chang, S.; Clark, J.; Conway, A.; Couban, R.; de Kock, S.; Farrah, K.; Fehrmann, P.; Foster, M.; Fowler, S. A.; Glanville, J.; Harris, E.; Hoffecker, L.; Isojarvi, J.; Kaunelis, D.; Ket, H.; Levay, P.; Lyon, J.; McGowan, J.; Murad, M. H.; Nicholson, J.; Pannabecker, V.; Paynter, R.; Pinotti, R.; Ross-White, A.; Sampson, M.; Shields, T.; Stevens, A.; Sutton, A.; Weinfurter, E.; Wright, K.; Young, S. PRISMA-S: An Extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timper, K.; Fenske, W.; Kühn, F.; Frech, N.; Arici, B.; Rutishauser, J.; Kopp, P.; Allolio, B.; Stettler, C.; Müller, B.; Katan, M.; Christ-Crain, M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Copeptin in the Differential Diagnosis of the Polyuria-Polydipsia Syndrome: A Prospective Multicenter Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015, 100, 2268–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaway, N. R.; Page, M. J.; Pritchard, C. C.; McGuinness, L. A. PRISMA2020: An R Package and Shiny App for Producing PRISMA 2020-compliant Flow Diagrams, with Interactivity for Optimised Digital Transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, M.; Nishioka, J.; Matsumoto, T.; Umino, S.; Kawano, A.; Saiki, R.; Tanaka, Y.; Yatsuga, S. Estimate Incidence and Predictive Factors of Pediatric Central Diabetes Insipidus in a Single-Institute Study. Endocrine and Metabolic Science 2022, 7–8, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, G.; Munarin, J.; De Sanctis, L. The Diagnostic Role of Arginine-Stimulated Copeptin in the Differential Diagnosis of Polyuria-Polydipsia Syndrome (PPS) in Pediatric Age. Endocrine 2023, 84, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzeler, B.; Cesana-Nigro, N.; Refardt, J.; Vogt, D. R.; Imber, C.; Morin, B.; Popovic, M.; Steinmetz, M.; Sailer, C. O.; Szinnai, G.; Chifu, I.; Fassnacht, M.; Christ-Crain, M. Arginine-Stimulated Copeptin Measurements in the Differential Diagnosis of Diabetes Insipidus: A Prospective Diagnostic Study. The Lancet 2019, 394, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, G.; Weber, K.; Peter, A.; Schweizer, R. Arginine-stimulated Copeptin in Children and Adolescents. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2023, 98, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, W.; Drummond, J. B.; Soares, B. S.; Ribeiro-Oliveira, A. A Combined Outpatient and Inpatient Overnight Water Deprivation Test Is Effective and Safe in Diagnosing Patients with Polyuria-Polydipsia Syndrome. Endocrine Practice 2018, 24, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, G.; Tessaris, D.; Einaudi, S.; Matarazzo, P.; De Sanctis, L. Copeptin Role in Polyuria-polydipsia Syndrome Differential Diagnosis and Reference Range in Paediatric Age. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2018, 88, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, C. A.; Sastry, S.; McPhaul, M. J.; Wheeler, S. E.; Garibaldi, L. Copeptin Stimulation by Combined Intravenous Arginine and Oral LevoDopa/Carbidopa in Healthy Short Children and Children with the Polyuria-Polydipsia Syndrome. Horm Res Paediatr 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nofal, A.; Hanna, C.; Lteif, A. N.; Pittock, S. T.; Schwartz, J. D.; Brumbaugh, J. E.; Creo, A. L. Copeptin Levels in Hospitalized Infants and Children with Suspected Vasopressin-Dependent Disorders: A Case Series. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 2023, 36, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gippert, S.; Brune, M.; Dirksen, R. L.; Choukair, D.; Bettendorf, M. Arginine-Stimulated Copeptin-Based Diagnosis of Central Diabetes Insipidus in Children and Adolescents. Horm Res Paediatr 2024, 97, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, L.; Marquant, E.; Fromonot, J.; Hamouda, I.; Berbis, J.; Godefroy, A.; Vierge, M.; Tsimaratos, M.; Reynaud, R. Copeptin Assays in Children for the Differential Diagnosis of Polyuria-polydipsia Syndrome and Reference Levels in Hospitalized Children. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2022, 96, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandri-Silva, C.; Carpenter, M.; Ayoob, R.; Barcia, J.; Chishti, A.; Constantinescu, A.; Dell, K. M.; Goodwin, J.; Hashmat, S.; Iragorri, S.; Kaspar, C.; Mason, S.; Misurac, J. M.; Muff-Luett, M.; Sethna, C.; Shah, S.; Weng, P.; Greenbaum, L. A.; Mahan, J. D. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcomes in Children With Congenital Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus: A Pediatric Nephrology Research Consortium Study. Front Pediatr 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loredana Petrea, C.; Ciortea, D.-A.; Miulescu, M.; Candussi, I.-L.; Chirila, S. I.; Isabela, G.; Răut, V. (; Berghes, S.-E.; Râs, M. C.; Berbece, S. I. A New Case of Paediatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus with Onset after SARS-CoV-2 and Epstein-Barr Infection-A Case Report and Literature Review. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Serbis, A.; Rallis, D.; Giapros, V.; Galli-Tsinopoulou, A.; Siomou, E. Wolfram Syndrome 1: A Pediatrician’s and Pediatric Endocrinologist’s Perspective. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagna, Y.; Courtillot, C.; Drabo, J. Y.; Tazi, A.; Donadieu, J.; Idbaih, A.; Cohen, F.; Amoura, Z.; Haroche, J.; Touraine, P. Endocrine Manifestations in a Cohort of 63 Adulthood and Childhood Onset Patients with Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Eur J Endocrinol 2019, 181, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claude, F.; Ubertini, G.; Szinnai, G. Endocrine Disorders in Children with Brain Tumors: At Diagnosis, after Surgery, Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy. Children (Basel) 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ-Crain, M.; Gaisl, O. Diabetes Insipidus. Presse Medicale. Elsevier Masson s.r.l. December 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gionis, D.; Ilias, I.; Moustaki, M.; Mantzos, E.; Papadatos, I.; Koutras, D. A.; Mastorakos, G. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis and Interleukin-6 Activity in Children with Head Trauma and Syndrome of Inappropriate Secretion of Antidiuretic Hormone. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2003, 16, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockenhauer, D.; van’t Hoff, W.; Dattani, M.; Lehnhardt, A.; Subtirelu, M.; Hildebrandt, F.; Bichet, D. G. Secondary Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus as a Complication of Inherited Renal Diseases. Nephron Physiol 2010, 116, p23–p29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakra, N. A.; Blumberg, D. A.; Herrera-Guerra, A.; Lakshminrusimha, S. Multi-System Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Review of Clinical Presentation, Hypothetical Pathogenesis, and Proposed Management. Children (Basel) 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, N. Y.; Aboelghar, H. M.; Garib, M. I.; Rizk, M. S.; Mahmoud, A. A. Pediatric Sepsis Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers: Pancreatic Stone Protein, Copeptin, and Apolipoprotein A-V. Pediatr Res 2023, 94, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, T.; Trivedi, A.; Tremoulet, A. H.; Hershey, D.; Burns, J. C. Hyponatremia in Patients With Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2021, 40, e344–e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choong, K. Vasopressin in Pediatric Critical Care. J Pediatr Intensive Care 2016, 05, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Citation | Participants | Clinical Setting | Study Design | Target Condition | Index Test | Reference Standard | Sample Size | Funding Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fenske et al., 2018 [10] | 156 patients aged 16 years or older | 11 tertiary medical centers in Switzerland, Germany, | Prospective multicenter study | Hypotonic polyuria | Copeptin measurement after water deprivation and hypertonic saline tests. | Final reference diagnosis by expert consensus. clinical diagnosis based on established criteria for central diabetes insipidus (CDI) and primary polydipsia (PP). | 156 participants | Supported by Swiss National Foundation, University Hospital Basel, Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| 2 | Kitamura M, et al. 2022 [16] | 27 patients polyuria and/or polydipsia (5 with central diabetes insipidus, 5 with primary polydipsia, 1 with nocturnal enuresis, and 16 with type 1 diabetes mellitus excluded due to hyperglycemia). | Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Kurume University School of Medicine, Japan. | Retrospective chart review | Central diabetes insipidus (CDI), primary polydipsia (PP), nocturnal enuresis | Hypertonic saline test, urine gravity in the morning | Copeptin levels, urine volume over 24 hours, urinary osmolality, plasma osmolality | 27 participants | Not specified |

| 3 | Tuli, G., Munarin, J., De Sanctis, L. (2023) [17] | Children with PPS including 7 with primary polyuria (PP), 6 with central diabetes insipidus (CDI), and 50 control subjects. | Department of Pediatric Endocrinology, Regina Margherita Children Hospital. | Prospective study | Central diabetes insipidus (CDI), primary polyuria (PP). | Arginine-stimulated copeptin test | Water deprivation test (WDT) | 63 participants (13 patients with PPS, 50 controls). | Not specified. |

| 4 | Winzeler B., et. al. 2019 [18] | Development cohort: 52 patients (12 with complete DI, 9 with partial DI, 31 with PP), 20 healthy adults, and 42 child controls; Validation cohort: 46 patients (12 with complete DI, 7 with partial DI, 27 with PP) and 30 healthy adult controls. | Multi-center study involving University Hospital Basel and five other centers in Switzerland and Germany | Prospective diagnostic study | Complete and partial diabetes insipidus, primary polydipsia. | Arginine-stimulated copeptin measurements | diagnostic accuracy of copeptin levels | Development cohort: 114 participants; Validation cohort: 76 participants (after exclusions). | Swiss National Science Foundation and University Hospital Basel. |

| 5 | Binder, G., Weber, K., Peter, A., & Schweizer, R. (2023) [19] | 72 children and adolescents tested for growth hormone deficiency, including 4 with confirmed central diabetes insipidus (CDI). | University Children's Hospital Tübingen, Germany | Monocentric retrospective analysis | Central diabetes insipidus (CDI). | Arginine-stimulated copeptin test. | Water deprivation test, serum osmolalityarginine-stimulation test and clinical evaluation | 72 participants (68 non-CDI, 4 with CDI) | Not specified. |

| 6 | Pedrosa et al., 2018 [20] | 52 patients aged 12–77 years (mean age 38.3 years; 53% women) | Hermes Pardini Endocrine Testing Center, Brazil | Retrospective analysis | Polyuria-Polydipsia Syndrome (PPS) | Hypertonic saline infusion followed by copeptin measurement | Plasma AVP levels | 52 participants | Supported by FAPEMIG and CNPq, JBD received a PhD grant from CAPES |

| 7 | Tuli, G., Munarin, J., De Sanctis, L. 2018 [21] | 80 children (53 control subjects, 12 hypopituitary children, and 15 children with PPS). | Pediatric Endocrinology Department. | Prospective observational study | Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI), complete central diabetes insipidus (CDI), and primary polydipsia (PP). | Copeptin levels after hypertonic saline infusion test and Water deprivation test | Plasma arginine-vasopressin (AVP) analysis | 80 participants | Not specified |

| 8 | March, C. A., Sastry, S., McPhaul, M. J., Wheeler, S. E., & Garibaldi, L. (2024). [22] | 47 healthy short children (controls), 10 children with primary polydipsia, and 10 children with AVP deficiency. | Pediatric endocrinology settings | Prospective interventional study. | Polyuria-polydipsia syndrome (PPS), arginine vasopressin (AVP) deficiency, primary polydipsia. | Arginine + LevoDopa/Carbidopa stimulation test (ALD-ST) for copeptin measurement. | Copeptin levels measured at baseline and after stimulation. | 67 participants (47 controls, 10 with primary polydipsia, 10 with AVP deficiency). | Not specified |

| 9 | Al Nofal, A., et. Al. (2024). [23] | 29 critically ill patients, including 6 infants, with hyper- or hypo-natremia. | Single-center study conducted in a hospital setting. | Retrospective case series. | Central diabetes insipidus (CDI), syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (SIAD). | Copeptin levels after hypertonic saline test. | Diagnostic thresholds for CDI and SIAD. | 29 patients (38% post-neurosurgical procedures). | Not specified |

| 10 | Gippert, S., Brune, M., Dirksen, R. L., Choukair, D., Bettendorf, M. (2024) [24] | 69 patients (32 with central diabetes insipidus [CDI], 32 matched controls, and 5 with primary polydipsia [PP]). | Single-center study in a pediatric endocrinology department. | Retrospective study | Central diabetes insipidus (CDI), primary polydipsia (PP) | Copeptin measurement following water deprivation test. | Comprehensive clinical and diagnostic characteristics, water deprivation test, and hypertonic saline infusion. | 69 participants | Not specified |

| 11 | Bonnet, L., et. al. 2024 [25] | 353 children aged 2 months to 18 years | Pediatric endocrinology and nephrology departments in France. | Single-center retrospective descriptive study | Central diabetes insipidus (CDI), primary polydipsia (PP), and other related conditions | Copeptin levels measured after arginine stimulation | Comparison with traditional diagnostic criteria for CDI and PP. | 353 participants, with 16 diagnosed with CDI and 18 with PP. | Funded by the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Institute Clinical and Translational Science Scholars Program (NIH/NCATS 1 KL2 TR001856). |

| Study | TP | FN | TN | FP | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | LR+ (95% CI) | LR- (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fenske et al. 2018 | 56 | 3 | 82 | 3 | 0.95 (95% CI: 85.15% - 99.36%) | 0.96 (96% CI: 89.73% - 98.89%) | 0.949 CI: (0.902-0.996) | 0.965 CI: (0.926-1.000) | 23.75 CI: (6.91-81.57) | 0.052 CI: (0.011-0.241) | 0.95 CI: (0.88-0.98) |

| 2 Kitamura et al. 2022 | 5 | 0 | 19 | 3 | 1 (100% CI: 56.56%-100%) | 0.857 (85.7% CI: 64.54% - 95.85%) | 0.625 CI: (0.396-0.854) | 1.000 CI: (0.829-1.000) | 7.00 CI: (2.55-19.24) | 0.000 CI: (0.00-0.00) | 0.93 CI: (0.85-0.99) |

| 3 Tuli G. et al. 2023 | 6 | 0 | 49 | 8 | 1 (100% CI: 61.51% -100%) | 0.857 (85.7% CI: 72.25% - 93.37%) | 0.429 CI: (0.237-0.621) | 1.000 CI: (0.928-1.000) | 7.00 CI: (2.55-19.24) | 0.000 CI: (0.00-0.00) | 0.93 CI: (0.83-0.98) |

| 4 Winzeler et al. 2019 | 11 | 0 | 54 | 2 | 1 (100% CI – 71.51% - 100%) | 0.96 (96% CI: 84.98% -99.46%) | 0.846 CI: (0.709-0.983) | 1.000 CI: (0.932-1.000) | 25.00 CI: (6.32-98.89) | 0.000 CI: (0.00-0.00) | 0.98 CI: (0.92-1.00) |

| 5 Binder et al. 2023 | 4 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 1 (100% CI: 56.56%-100%) | 1 (100% CI: 76.03% - 100%) | 1.000 CI: (0.783-1.000) | 1.000 CI: (0.803-1.000) | N/A (perfect tets) | N/A (perfect tets) | 1.00 (perfect test) CI: (0.90-1.00) |

| 6 Pedrosa et al. 2018 | 8 | 0 | 26 | 1 | 1 (100% CI: 56.56% - 1000%) | 0.96 (96% CI: 77.97% -99.57%) | 0.889 CI: (0.679-1.000) | 1.000 CI: (0.867-1.000) | 25.00 CI: (3.66-171.14) | 0.000 CI: (0.00-0.00) | 0.98 CI: (0.92-1.00) |

| 7 Tuli et al. 2018 | 9 | 0 | 36 | 1 | 1 (100% CI: 61.51% - 100%) | 0.97 (97% CI: 83.34% - 99.63%) | 0.900 CI: (0.742-1.000) | 1.000 CI: (0.889-1.000) | 33.00 CI: (4.72-230.84) | 0.000 CI: (0.00-0.00) | 0.99 CI: (0.92-1.00) |

| 8 March et al. 2018 | 8 | 0 | 22 | 2 | 1 (100% CI: 61.51% - 100%) | 0.92 (92% CI: 69.99% - 98.98%) | 0.800 CI: (0.543-1.000) | 1.000 CI: (0.824-1.000) | 12.50 CI: (3.46-45.13) | 0.000 CI: (0.00-0.00) | 0.96 CI: (0.88-0.99) |

| 9 Nofal et al. 2023 | 10 | 0 | 29 | 1 | 1 (100% CI: 69.15% - 100%) | 0.95 (95% CI: 80.53% -99.29%) | 0.909 CI: (0.725-1.000) | 1.000 CI: (0.868-1.000) | 20.00 CI: (4.65-86.08) | 0.000 CI: (0.00-0.00) | 0.98 CI: (0.90-0.99) |

| 10 Gippert et al. 2023 | 12 | 0 | 36 | 2 | 1 (100% CI: 73.54% - 100%) | 0.94 (94% CI: 80.09% - 98.40%) | 0.857 CI: (0.689-1.000) | 1.000 CI: (0.917-1.000) | 16.67 CI: (5.15-53.89) | 0.000 CI: (0.00-0.00) | 0.97 CI: (0.89-0.99) |

| 11 Bonnet et al. 2021 | 8 | 0 | 20 | 3 | 1 (100% CI: 56.56% - 100%) | 0.87 (87% CI: 66.89% - 95.45%) | 0.727 CI: (0.476-0.978) | 1.000 CI: (0.823-1.000) | 7.69 CI: (2.86-20.64) | 0.000 CI: (0.00-0.00) | 0.93 CI: (0.82-0.97) |

| Study | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity Variance | Specificity Variance | AUC Variance | Weight (Sensitivity) | Weight (Specificity) | Weight (AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fenske et al. 2018 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.0013 | 0.000548 | 0.000423 | 769.23 | 1824.82 | 2364.07 |

| 2 Kitamura et al. 2022 | 1.00 | 0.857 | 0.93 | 0.0123 | 0.0064 | 0.006735 | 81.30 | 156.25 | 148.48 |

| 3 Tuli G. et al. 2023 | 1.00 | 0.857 | 0.93 | 0.0097 | 0.0029 | 0.005389 | 103.09 | 344.83 | 185.56 |

| 4 Winzeler et al. 2019 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.0053 | 0.0014 | 0.000904 | 188.68 | 714.29 | 1106.19 |

| 5 Binder et al. 2023 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.0123 | 0.0037 | 0.001 | 81.30 | 270.27 | 1000.0 |

| 6 Pedrosa et al. 2018 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.0123 | 0.0030 | 0.001271 | 81.30 | 333.33 | 786.78 |

| 7 Tuli et al. 2018 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.0097 | 0.0017 | 0.000565 | 103.09 | 588.24 | 1769.91 |

| 8 March et al. 2018 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.0097 | 0.0054 | 0.002507 | 103.09 | 185.19 | 398.88 |

| 9 Nofal et al. 2023 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.0062 | 0.0023 | 0.001015 | 161.29 | 434.78 | 985.22 |

| 10 Gippert et al. 2023 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.0046 | 0.0022 | 0.001247 | 217.39 | 454.55 | 801.92 |

| 11 Bonnet et al. 2021 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.0123 | 0.0053 | 0.004267 | 81.30 | 188.68 | 234.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).