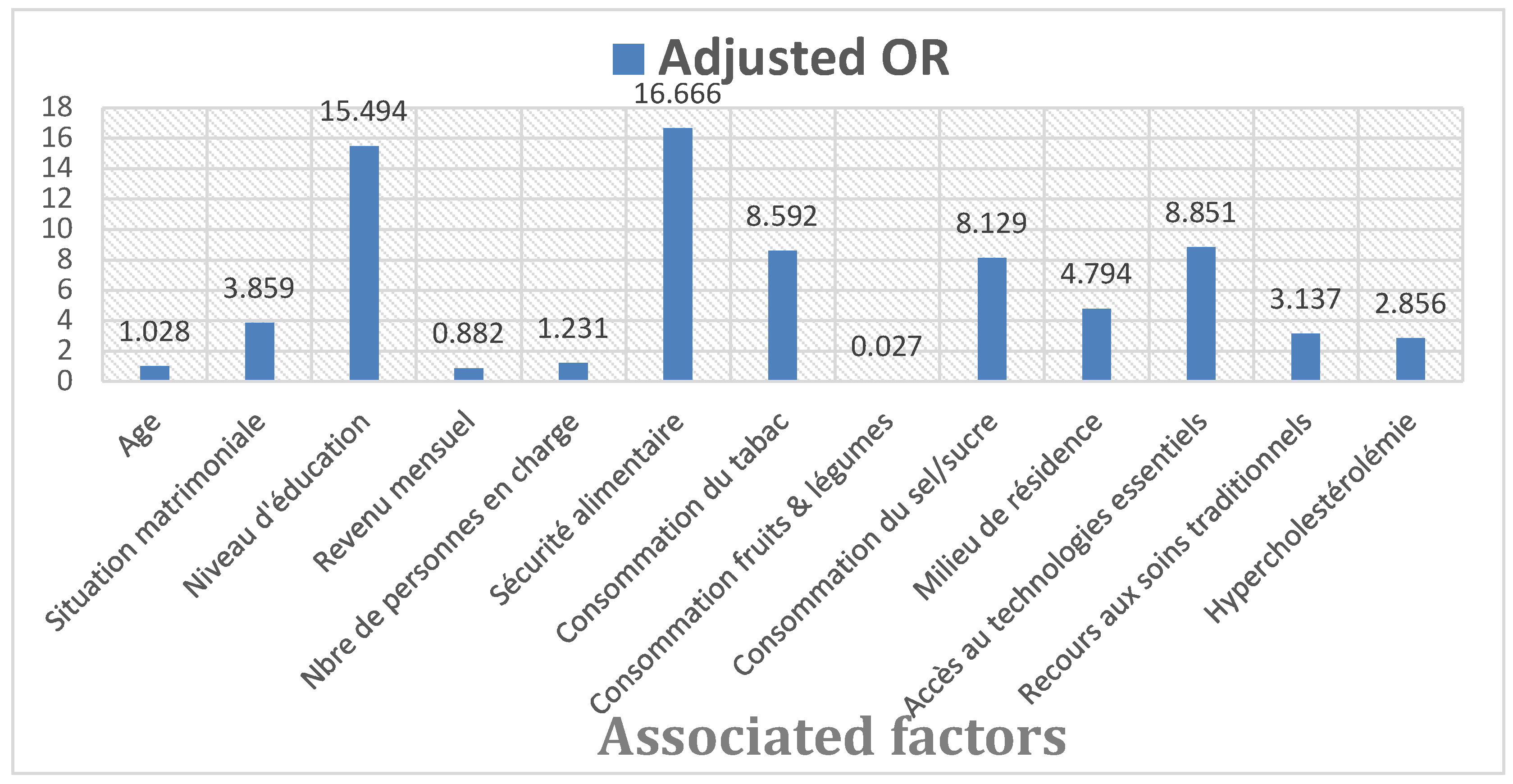

Summary: Hypertension is a public health problem with serious social, economic, and health consequences. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that 1 in 3 adults worldwide suffers from hypertension. In Cameroon, the prevalence of hypertension is estimated at 35%, with nearly 17,000 deaths recorded each year. This study aimed to determine the factors associated with the occurrence and complications of hypertension at the Sangmélima Referral Hospital (HRS). A total of 528 patients treated in the cardiology department of the HRS were identified between January and December 2023. The data were analyzed using SPSS 28 software. Binary logistic regression determined the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals associated with each variable. Differences were statistically significant for a p-value < 0.05. At the HRS, the annual incidence of hypertension was 16.13%. Hypertension was present in 78.8% of patients. The factors associated with the occurrence and complications of hypertension were age (OR=1.028; p=0.003 ), level of education (OR=15.49; p=0.023), marital status (OR=3.859; p=0.04), hypercholesterolemia (OR=2.856; p=0.01), monthly income (OR=0.882; p=0.026), number of dependents (OR=1.231; p=0.025), food security (OR=16.666; p<0.001), tobacco consumption (OR=8.592; p=0.041), fruit and vegetable consumption (OR=0.027; p=0.031), salt/sugar consumption (OR=8.129; p<0.001), place of residence (OR=4.794; p=0.005), access to essential technologies (OR=8.851; p=0.002), and use of traditional care (OR=3.137; np=0.032). HTA at the HRS is associated with several factors. In order to limit the impact of hypertension, it is crucial to emphasize improving socioeconomic and health conditions.

1. Introduction

Hypertension is responsible for more than 10 million preventable deaths worldwide each year. Low- and middle-income countries suffer the most, with an increase in cases of uncontrolled hypertension and deaths from cardiovascular disease (CVD). [

1]. Hypertension is a chronic disease associated with abnormally high blood pressure in the blood vessels. If left uncontrolled, hypertension is one of the main risk factors for cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases[

2]. Age, family history, and the coexistence of other pathologies, such as diabetes or kidney disease, can increase the risk of hypertension. However, this risk can also be increased by modifiable risk factors such as a diet high in salt, saturated fats, and trans-fatty acids, insufficient consumption of fruit and vegetables, a sedentary lifestyle, tobacco and alcohol consumption, and being overweight or obese[

1,

2,

3].

Worldwide, the prevalence of hypertension varies according to region and income group. In sub-Saharan Africa, prevalence rates vary from 25% to 35% among adults aged 25 to 64, and some studies show that there is a direct link between blood pressure levels, salt consumption, fat consumption, and body weight. [

4].

Although the epidemiological situation of hypertension in Cameroon is poorly documented, there are studies showing associations between P.H. and other chronic diseases. [

5]. A 1998 study found a prevalence of hypertension of 18.5% in men and 12.6% in women [

6]. This figure rose to 25% in the general population in 2012 [

7]. In 2015, the national prevalence of hypertension rose to 29.7%. Today, hypertension is on the rise in Cameroon, affecting almost 35% of the adult population[

8]. In the southern region, and particularly in the town of Sangmélima, the consumption of alcohol and narcotics is excessive due to the proximity of the borders. In addition, eating habits are not very diverse and are highly Westernized. A large proportion of the population (around 40%) is unaware of prevention knowledge, attitudes, and practices. [

9]. All of these factors increase the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and hypertension, particularly in urban areas, even among young people. [

10].

At the Sangmélima Reference Hospital (HRS), the arrival of a cardiologist in 2018 has improved diagnosis and revealed a high incidence of cardiovascular disease in the locality. The number of consultations for CVD-related causes (including hypertension) rose from 157 in 2018 to 625 in 2023[

11]

The influence of multiple traditional therapies, social networks, prolonged drug shortages in hospitals, poverty and illiteracy among the population complicates this situation. [

9] This situation is further complicated by the influence of multiple traditional therapies, social networks, prolonged drug shortages in hospitals, and the poverty and illiteracy of the population.

Despite the growing incidence of CVD in the locality, there is a scarcity of data that would lead to the development of policies promoting healthy lifestyles and improved socioeconomic and health conditions [

8]. The present study aimed to determine the factors associated with the onset and complications of hypertension in HRS.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective cohort study records data on 528 patients treated in the cardiology department of the HRS between January and December 2023. The variables of interest were sociodemographic, clinical, socioeconomic, behavioral, socio-cultural, and health-related.

Data was collected in two complementary phases. The first (passive) phase consisted of a census of the medical records of eligible patients, followed by the collection of quantitative data, and the second (active) phase involved individual, structured telephone interviews with participants to collect qualitative data not contained in the records.

The data were analyzed using SPSS 28 software. The Chi-2 test was used to compare frequencies and Cramer’s V to measure the magnitude of the association with each variable. Binary logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals associated with each variable. Differences were statistically significant at a p-value < 0.05.

Obtaining institutional ethical clearance, authorization for data collection, and participants’ free and voluntary participation were among the main ethical considerations. Data collection lasted 03 months from January 2024.

3. Results

3.1. Univariate Descriptive Analysis

3.1.1. Sociodemographic Factors

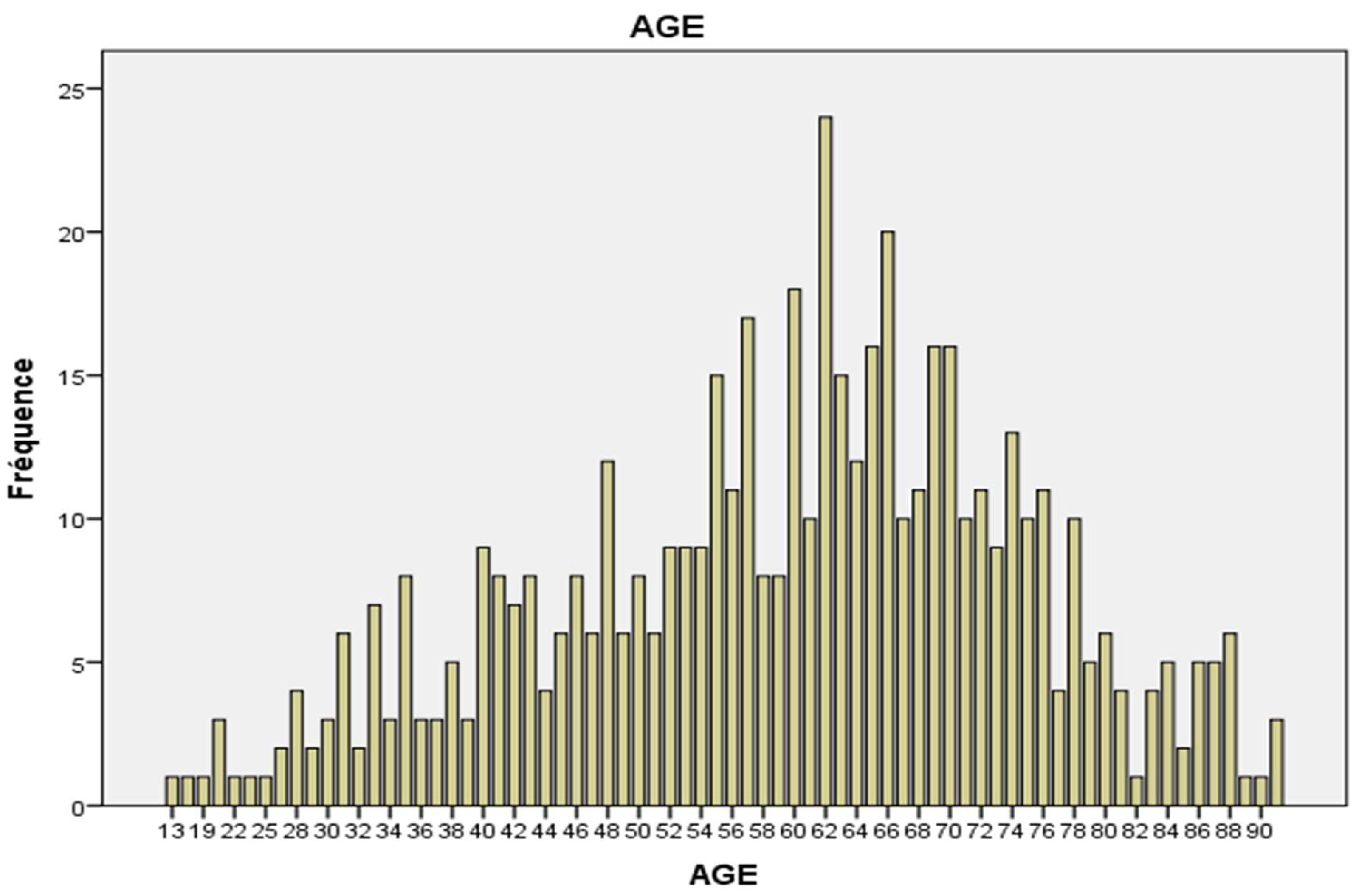

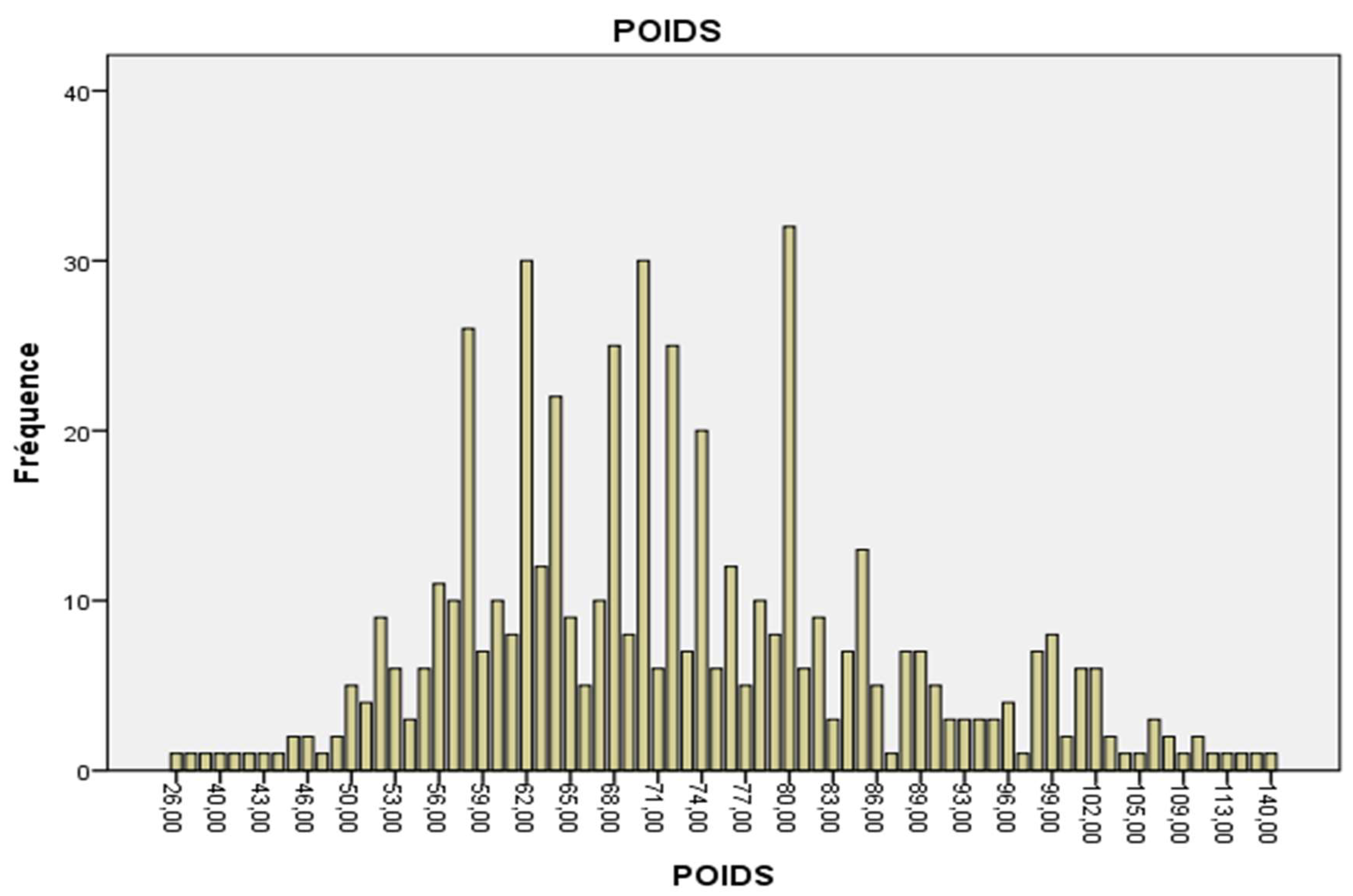

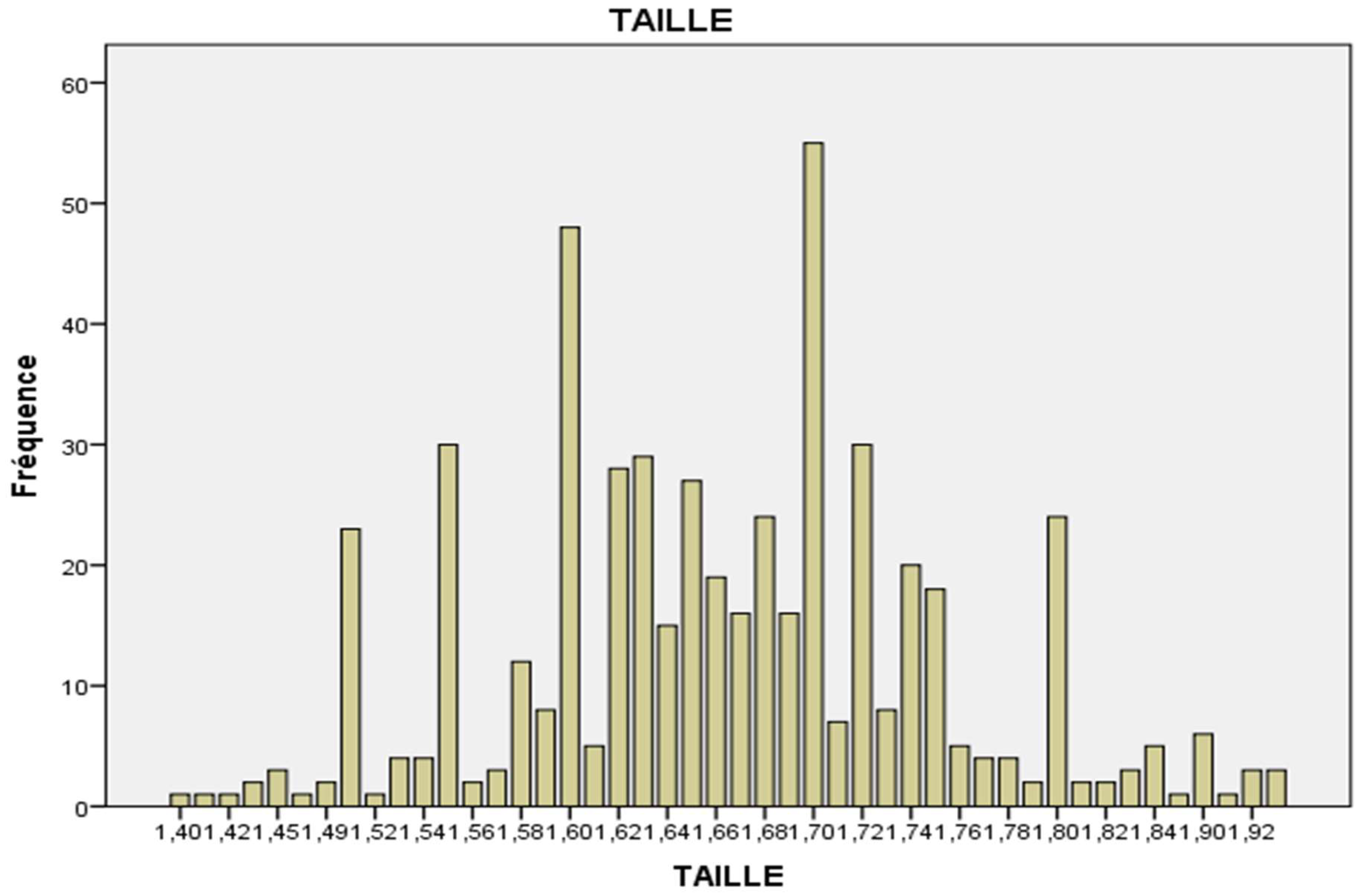

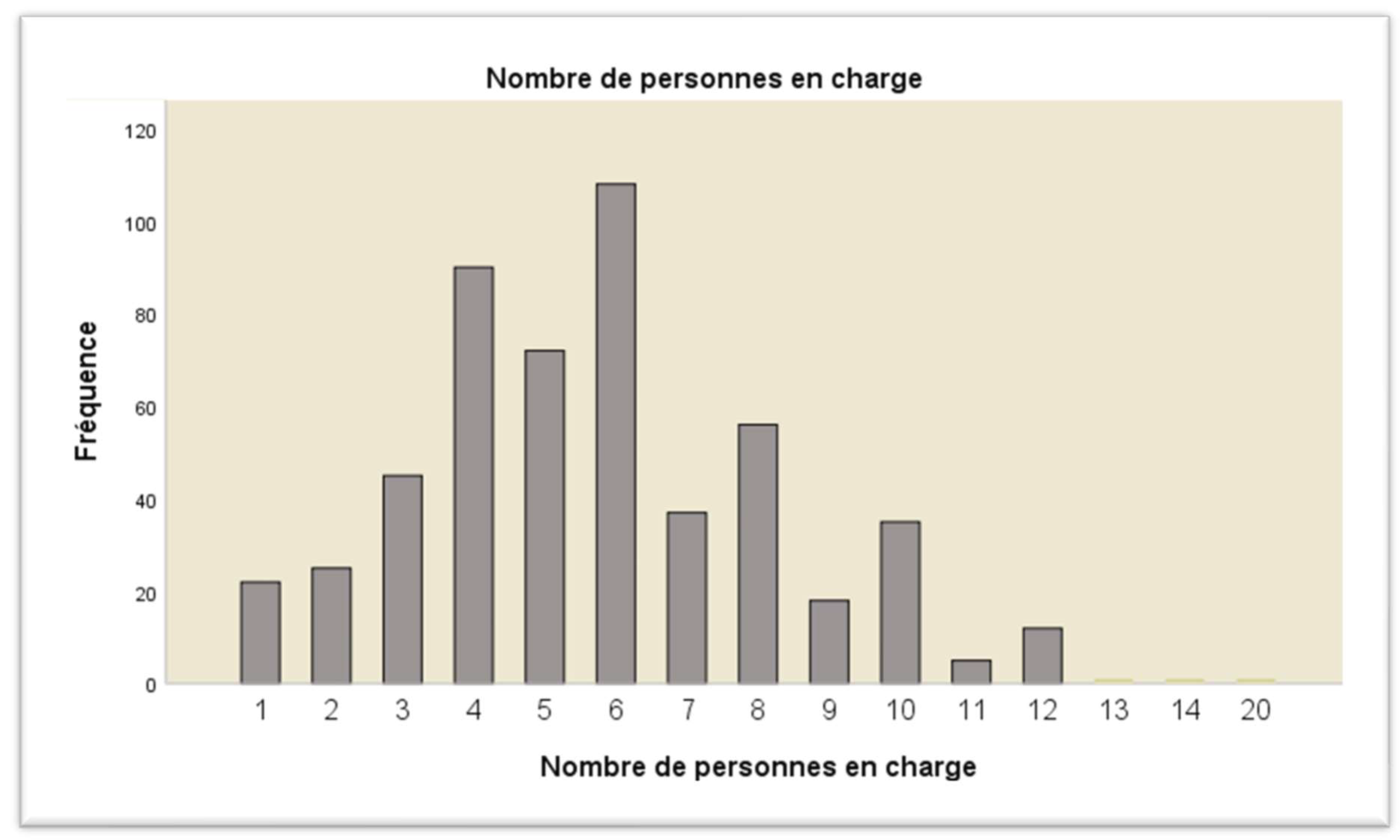

Socio-demographically, the participants ranged in age from 13 to 92 years and were predominantly female (58%). The average age was 59.46 ± 15.35 years; the average weight was 72.34 kg; the average height was 1.66 m, and the average number of dependent children was 6. 50.6% of the participants were married; primary education was the most common level with 62.7% (

Table 1,

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

3.1.2. Clinical and Metabolic Factors

Clinically and metabolically, 78.8% of the participants were hypertensive, 20.6% were obese, 10% were diabetic, and 18% had hypercholesterolemia (

Table 2).

3.1.3. Socioeconomic Factors

In socioeconomic terms, 18% of participants were retired; 54.7% of patients had a monthly income of between 50,000 and 100,000 FCFA. The average number of dependents was 6, so 84.8% of food requirements were insufficient (

Table 3).

3.1.4. Behavioural Factors

In terms of behavior, 5.7% of participants regularly smoked, 33.7% regularly drank alcohol, 26.1% played sports weekly, 22.3% regularly ate fruit and vegetables, and 62.7% regularly ate salty or sweet foods (

Table 4).

3.1.5. Environmental and Cultural Factors

Regarding environment and culture, 75.8% of participants live in urban areas, 95.5% of patients are Christian, and 81.3% belong to the Fang-Beti cultural area (

Table 5).

3.1.6. Health Factors

In terms of health, the most frequently diagnosed complications of hypertension were hypertensive heart disease (48.5%), followed by ischaemic heart disease (25.2%), heart failure (10.3%) and stroke (4.9%). In addition, of the 528 participants surveyed, 21.2% of CVD were diagnosed early, 93.2% of participants had access to essential medicines, 90% of participants had access to therapeutic education, 83.3% of participants had access to essential technologies, and 17.4% used traditional care at the same time (

Table 6).

A descriptive analysis of our sample shows that homemakers aged around 60 with primary education are the most affected by hypertension. Overall, hypertension is present in 78.8% of participants, 84.8% of whom live in unfavorable socioeconomic conditions. Of these, 75.8% live in urban areas, and 62.3% regularly consume salty or sugary foods. 78.6% of diseases are detected late and, despite this, 17.4% resort to traditional care.

3.2. Bivariate Analysis

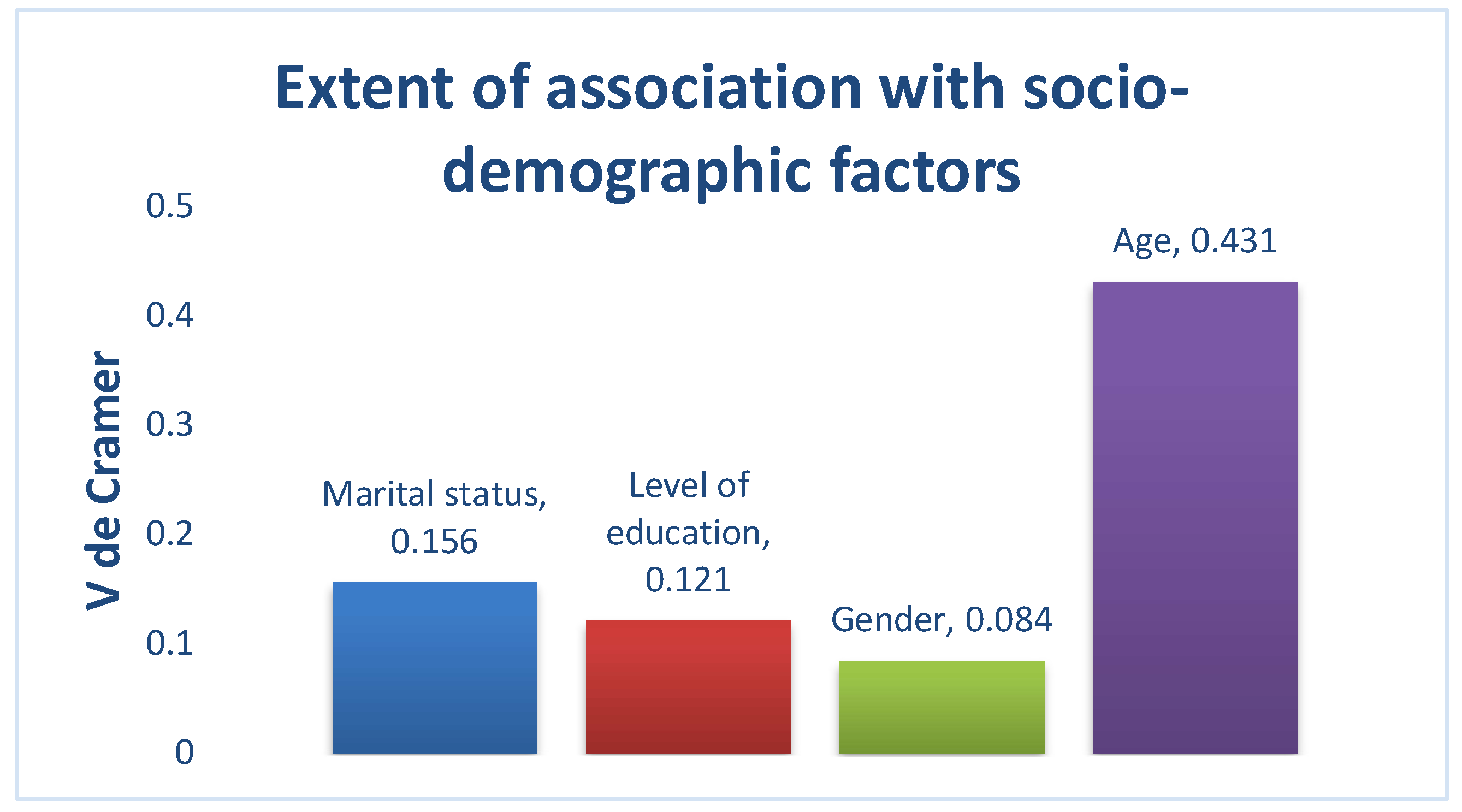

3.2.1. Sociodemographic Factors

In terms of socio-demographics, age was strongly associated with the onset of hypertension among the participants surveyed, while marital status, level of education, and gender were weakly associated with hypertension among the participants surveyed (

Figure 5).

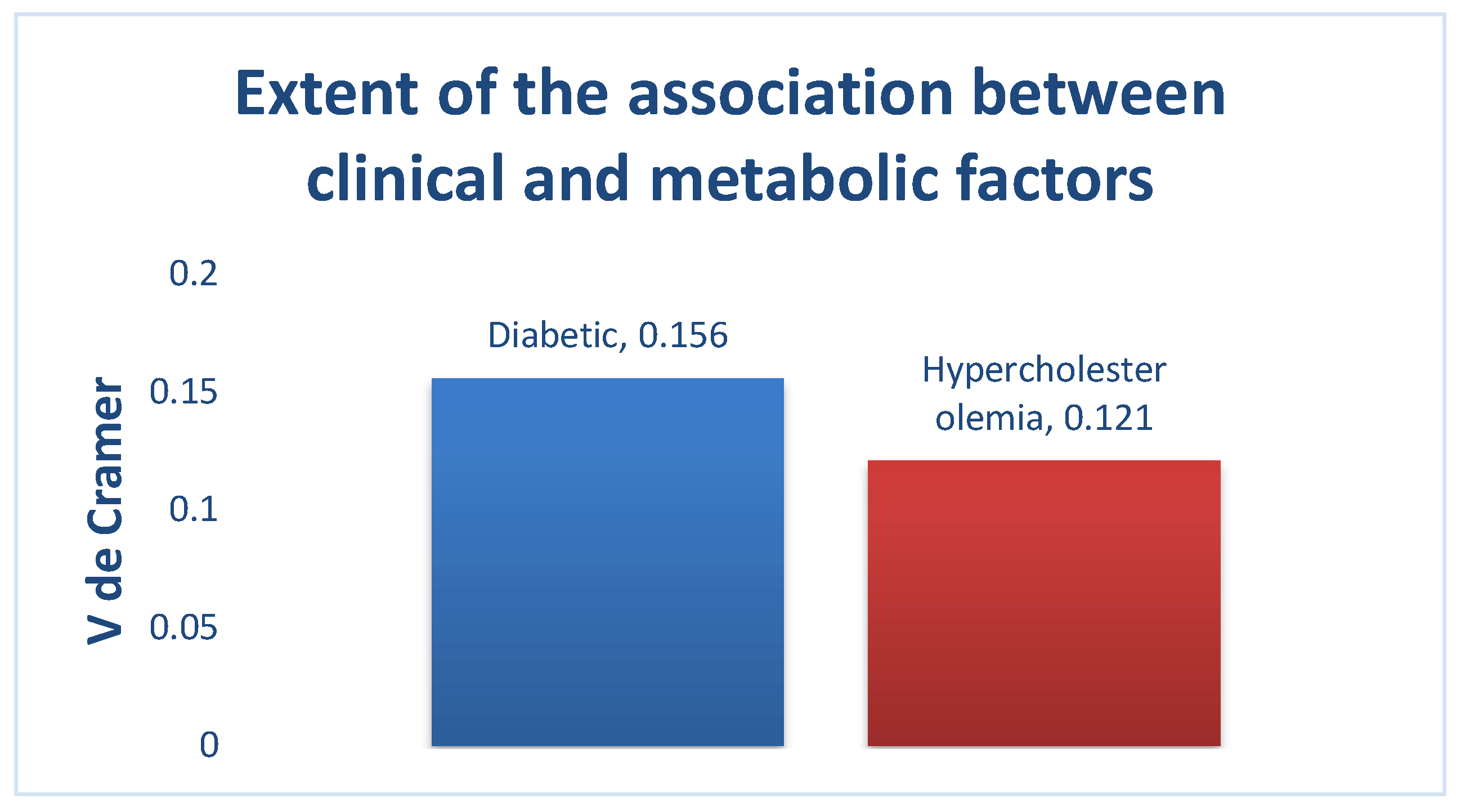

3.2.2. Clinical and Metabolic Factors

In clinical and metabolic terms, there was no association between the variables weight, height, and BMI of the participants and hypertension. On the other hand, there was a weak association between hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia, respectively among the participants surveyed (

Figure 6).

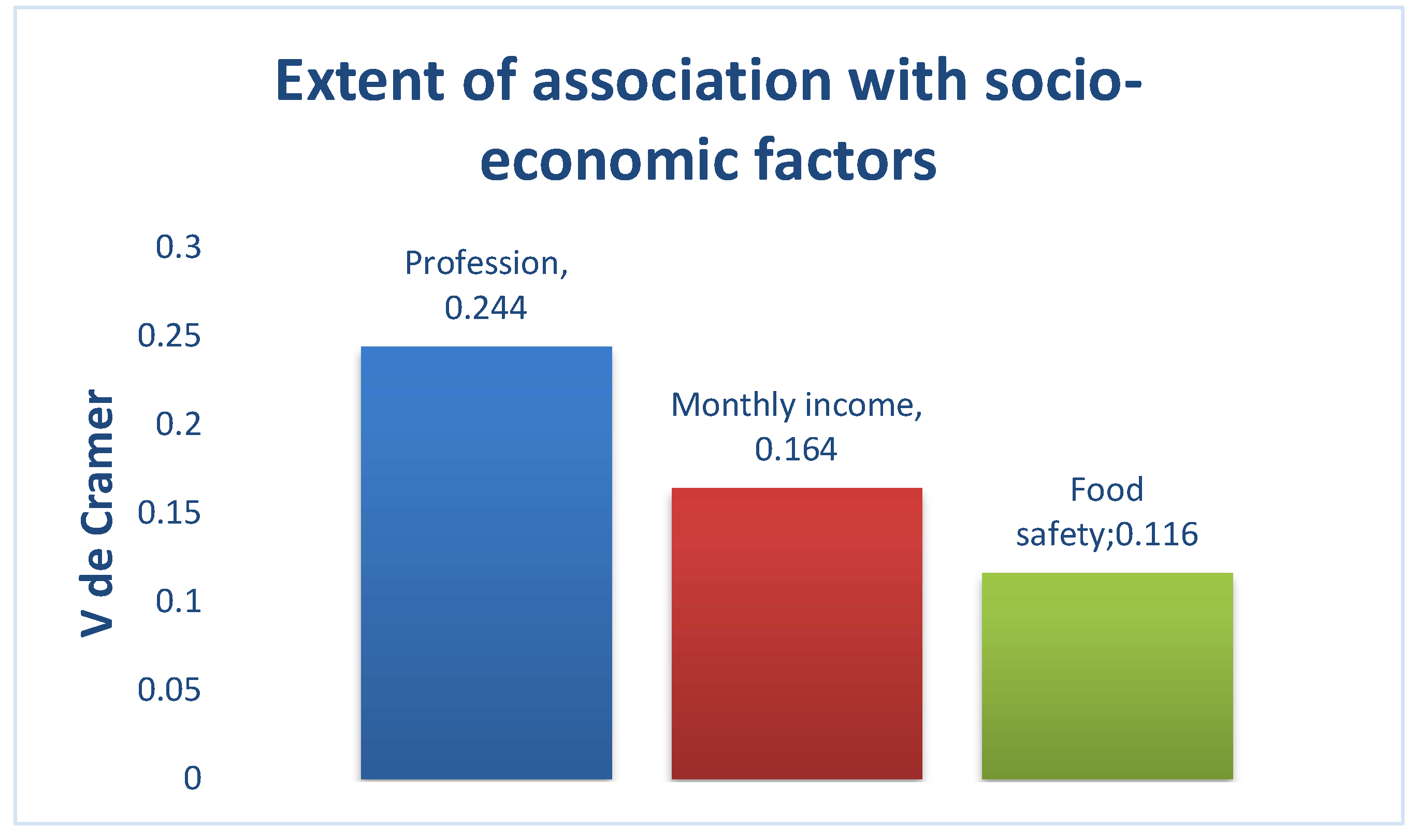

3.2.3. Socioeconomic Factors

Regarding socioeconomic status, there was a moderate association between hypertension and occupation and a weak association between hypertension, participants’ income, and food security among the participants surveyed (

Figure 7).

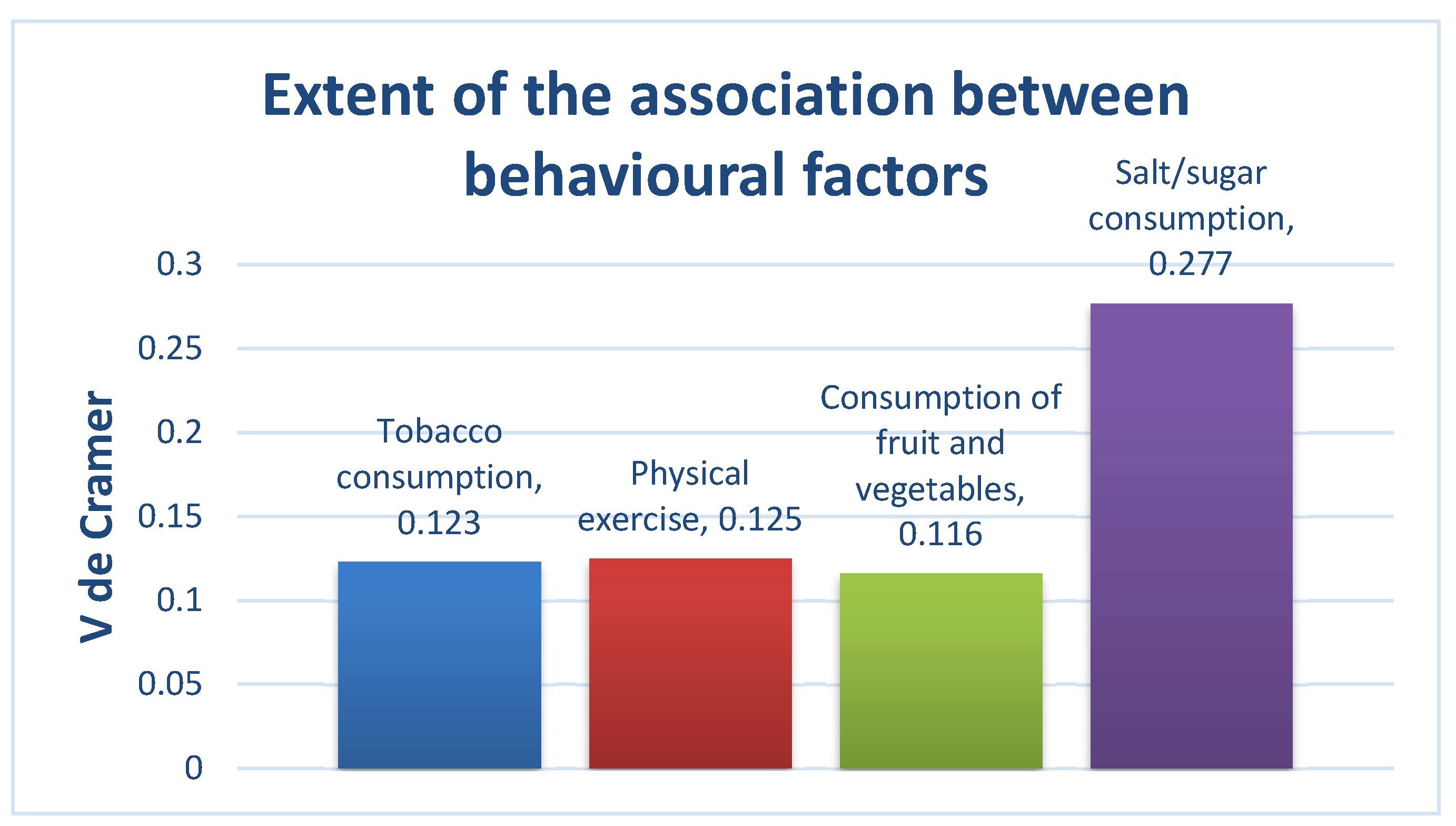

3.2.4. Behavioural Factors

At the behavioral level

, there was no association between hypertension and alcohol consumption among the participants identified. There was a weak association between hypertension and smoking, physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption, and a moderate association between hypertension and salt or sugar consumption among the participants surveyed (

Figure 8).

3.2.5. Environmental and Cultural Factors

Regarding the physical and socio-cultural environment, there was no association between hypertension and the various independent variables tested in our sample (cultural area, place of residence, and religion).

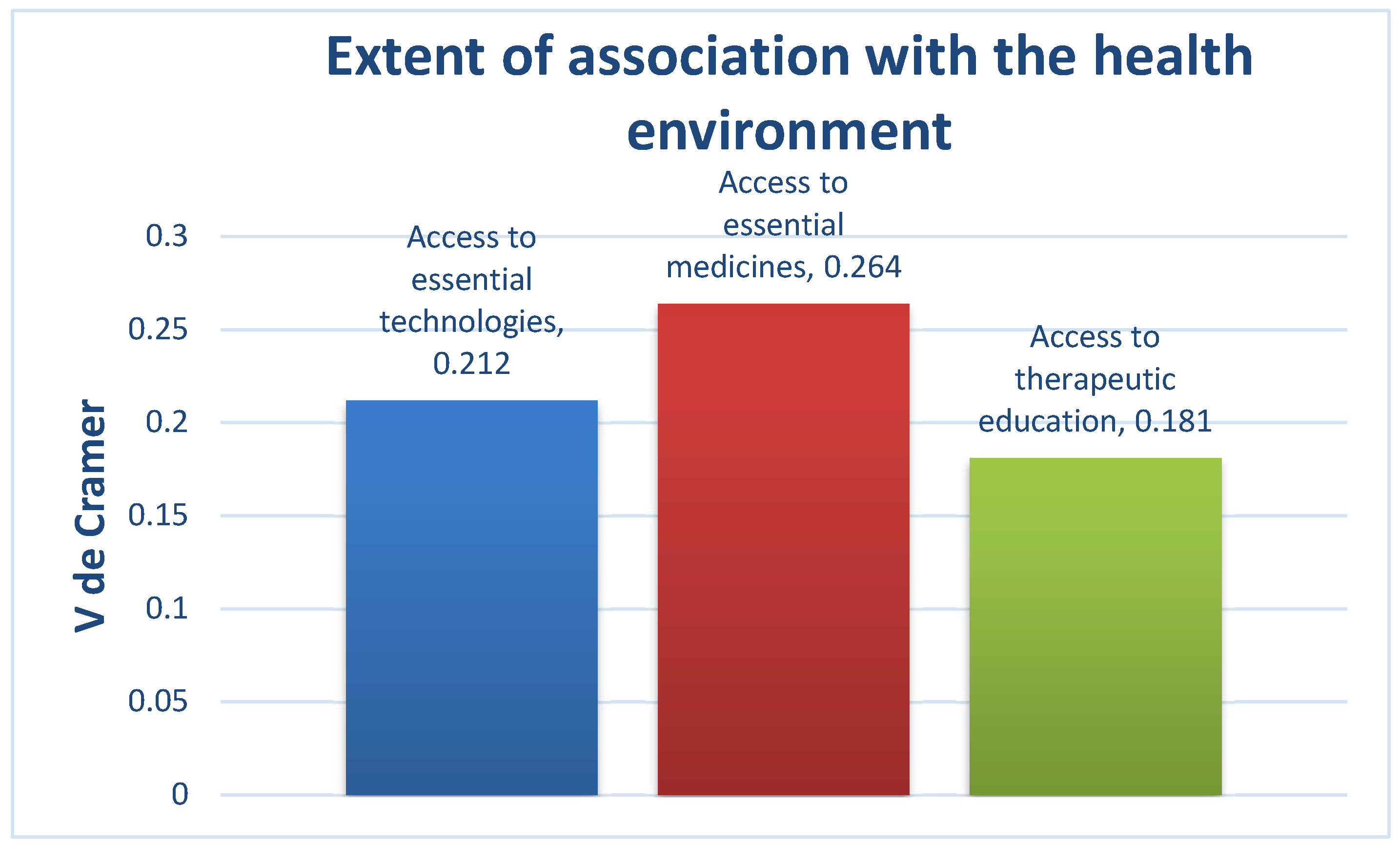

3.2.6. Health Factors

Regarding health, there was no association between hypertension, access to early detection, and use of traditional care. There was a moderate association between hypertension, access to essential technologies, and access to essential medicines, respectively, and a weak association between hypertension and access to therapeutic education among the participants identified (

Figure 9).

Finally, the bi-variate analysis of our sample shows that :

The variable most strongly associated with the onset of hypertension is age;

The variables moderately associated with the onset of hypertension are hypercholesterolemia, occupation, salt/sugar consumption, access to technology and essential medicines;

The variables weakly associated with the onset of hypertension are sex, marital status, level of education, diabetes, monthly income, food security, smoking habits, physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption, and access to therapeutic education.

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

Binary logistic regression showed that the null model (beginning block) predicted a risk of hypertension with an accuracy rate of 78.8% in the absence of associated factors. Furthermore, this model is significant at 0.001, with an association constant of 1.312 and a standard error of 0.106.

When the variables analyzed were included in the model, age, level of education, hypercholesterolemia, occupation, number of dependents, food security, fruit and vegetable consumption, salt/sugar consumption, place of residence, access to essential technologies and use of traditional care proved significant with different strengths of association (adjusted OR) (

Table 7,

Figure 10). Including these variables increases the significance of the model with a Chi-square of 293.070 and an accuracy rate of 89.6%. Among these factors :

The protective factors (OR < 1) against the onset of hypertension are: monthly income consumption of fruit and vegetables (0.976).

The risk factors (OR > 1) for the development of hypertension are: age (0.028); marital status (3.859); hypercholesterolemia (2.856); level of education (15.494); number of dependents (0.231); food security (16.666); tobacco consumption (8.592); salt or sugar consumption (8.129); place of residence (4.794); access to essential technologies (8.851); use of traditional care (3.137);

4. Discussion

4.1. The Incidence of Arterial Hypertension and Its Main Complications at Sangmélima Referral Hospital

The HRS 2023 annual activity report shows that 625 patients were seen in the cardiology department out of 3,875 outpatients and 6,977 overall hospitalizations [

9]. This represents an annual incidence of 16.13% for outpatients and 8.96% for inpatients. Among the 528 participants in our study, hypertension was present in 416 (78.8%) cases. The most frequently diagnosed complications of hypertension were hypertensive heart disease (48.5%), followed by ischaemic heart disease (25.2%), heart failure (10.3%) and stroke (4.9%). These results show that CVD is one of the major causes of consultation and hospitalization in our context. These results are in agreement with Vernay M et al., who revealed that cardiovascular disease is the second leading cause of mortality in Cameroon, with an estimated case-fatality rate of 8.6%. [

12,

13].

Furthermore, 13.7% of all deaths are attributed to hypertension. Unfortunately, these figures are set to rise with urbanization, the westernization of diets, and the aging of the population. Complications of hypertension are still dominated by hypertensive heart disease (48.5% in our study), which confirms that hypertension is both a CVD and a risk factor for aggravation and complication of other CVD.[

14].

4.2. Sociodemographic Factors Associated with the Onset of Arterial Hypertension at Sangmélima Referral Hospital

Several studies have shown the association between sociodemographic factors and the onset of hypertension[

15,

16]. In our study, the sociodemographic variables associated with the onset of hypertension were age, marital status, and level of education. The literature shows that the incidence of hypertension increases with age [

17]. Less than 10% of 18-34 year-olds are affected, compared with more than 65% after 65. Aging promotes loss of elasticity in the arteries and is the main non-modifiable risk factor. In our context, age is also associated with the onset of hypertension, with an odds ratio of 1.028. This means increasing age by one year increases hypertension by 0.028 (2.8%).

Concerning marital status, there is an association between marital status and the onset of hypertension[

18,

19,

20]. Certain groups of individuals are more likely to be victims of social exclusion or discrimination, particularly widows/widowers, and therefore more likely to develop hypertension. Some authors point out that loneliness is mainly responsible for the differences in blood pressure observed in the elderly[

21]. Others have also shown a direct link between loneliness and systolic blood pressure, a relationship that increases with age[

22,

23,

24]. We can, therefore, understand the influence of marital status on the onset of hypertension. In the case of our study, hypertension is multiplied by 3.859 in people living alone compared with married people.

Concerning level of education, the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) studies carried out in several places establish a relationship between schooling, level of education, and hypertension. In other words, there is a direct link between hypertension control and level of education[

25,

26,

27]. In the case of our study, the increase in hypertension observed among homemakers (adjusted OR = 15.494) compared with those in higher education seems to be linked to their low level of knowledge (primary education).

4.3. Clinical and Metabolic Factors Associated with the Onset of Arterial Hypertension at Sangmélima Referral Hospital

Clinically and metabolically, the variable significantly associated with the onset of hypertension is hypercholesterolemia. High cholesterol levels can reduce blood flow (hypertension) and thus increase the risk of heart attack or stroke. Hypercholesterolaemia, particularly the increase in LDL-cholesterol in the blood, is at the root of hypertension and other CVDs[

28]. The results of our study show that hypertension is significantly associated with other CVDs, with a Chi-square of 0.001 and a magnitude of association equal to 0.503. This means that hypertension shares the same risk factors as diagnosed CVD.

4.4. Socioeconomic Factors Associated with the Onset of Hypertension at Sangmélima Referral Hospital

Regarding socioeconomic status, our study found that occupation, number of dependents, and food security were significantly associated with the onset of hypertension. Many risk factors or complications of hypertension are inversely associated with an individual’s socioeconomic status[

29]. Studies show that mortality among people with hypertension was higher in the most disadvantaged environments (22.6%) than in the most advantaged environments (16.8%)[

30,

31].

There is an association between occupation (income level) and food security and hypertension, especially as malnutrition in all its forms (notably undernutrition, micronutrient deficiency, overweight, and obesity) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality linked to NCDs. Similarly, a family’s income level also influences the education offered to its offspring. This being the case, many children drop out of school for lack of financial means and are therefore subject to poverty and lack of education, which is a factor associated with hypertension, with an odds ratio that is also very high (15.494)[

30,

31,

32].

In our study, occupation and the number of dependents in a household act synergistically on food security, which in turn influences the occurrence of hypertension with an odds ratio of 16.666. This being the case, we can conclude that there is an inverse association between monthly income (adjusted OR = 0.882) and food security (adjusted OR = 0.060) on hypertension. This association is directly proportional to the number of dependent children (adjusted OR = 1.231).

4.5. Behavioural Factors Associated with the Onset of Arterial Hypertension at Sangmélima Referral Hospital

In terms of behavior, consumption of tobacco, fruit, vegetables, and salt/sugar were significantly associated with the onset of hypertension, with adjusted O.R.s of 8.592, 0.027, and 8.129, respectively. This means that fruit and vegetable consumption has a protective effect of 0.973 (97.3%) on hypertension, while tobacco and salt/sugar consumption have a multiplier effect of 8.592 and 8.129, respectively, on hypertension.

Smoking increases the risk of developing several non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, diabetes, and cancer. Smoking increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, in particular ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, and hypertensive disease[

33]. In addition, smoking has a potentiating effect on other cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypercholesterolemia, and this risk persists even after adjustment for these factors[

34,

35].

Good nutrition boosts the immune system. Greater adherence to the DASH (Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension) or Mediterranean diet benefits blood pressure. For example, fruits and vegetables provide vitamins and minerals, and the health-promoting fats contained in olives or seeds are rich in unsaturated fatty acids, which are necessary for the proper functioning of the immune response[

36]. On the other hand, a diet high in saturated fats, sugars, and salt predisposes to obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cancer. In addition, the so-called ‘Western’ diet (rich in fats, sugars, and carbohydrates) leads to chronic inflammation and a reduced immune response to viral infections[

37]. The association between a high-fat diet in the mother can sometimes lead to hypertension in the offspring[

38].

Alcohol consumption and physical activity, as identified in other studies, had no significant effect on our sample.

4.6. Socio-Cultural and Environmental Factors Associated with the Onset of Arterial Hypertension at Sangmélima Referral Hospital

In cultural and environmental terms, the environment in which people live is the only variable to significantly influence the onset of hypertension, with an adjusted OR of 4.794. An ecological study showed that an unfavorable residential context (dust, natural, and water pollution) was associated with a higher prevalence of hypertension[

39]. Another study showed that the environment did not influence hypertension in the same way as education or employment. Individuals living in an intermediate environment were found to have the highest prevalence of hypertension[

40]. In our study, urban residents increased hypertension by 4.794 times compared with rural residents.

4.7. Health Factors Associated with the Occurrence of Arterial Hypertension at Sangmélima Referral Hospital

In terms of health, there is an association between health systems and the onset of hypertension[

41]. Blood pressure may be temporarily elevated due to stress, physical activity, or the environment in which it is measured (in a hospital, for example, this is known as the white coat effect)[

42,

43,

44,

45]. Under these conditions, two measurements per consultation during three successive consultations over three to six months are necessary to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension. Doctors, therefore, recommend monitoring blood pressure at home using an automatic blood pressure monitor. Unfortunately, very few people treated for hypertension are equipped with a self-measuring device. In the case of our study, this percentage is estimated at 16.9%.[

36,

37].

Furthermore, most hospitals in outlying urban centers lack qualified staff to manage hypertension and its complications[

46,

47]. At the same time, tests such as electrocardiograms and echocardiograms, which can detect and prevent heart problems, are expensive. This situation is complicated by the influence of multiple traditional therapies[

48]. The influence of multiple traditional therapies, social networks, prolonged drug shortages in hospitals, and the poverty of the population complicates this situation. This is why recourse to traditional care is so high, estimated at 17.4% in our study. This percentage would double if we included patients who used only traditional care. Additional STEPS-type surveys, proposed by the WHO, are needed to verify this.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study show that high blood pressure is present in 78.8% of participants, 84.8% of whom live in poor socioeconomic conditions, 75.8% of whom live in urban areas, and 62.3% of whom regularly consume salty or sugary foods. Of these, 75.8% lived in urban areas, and 62.3% regularly consumed salty or sugary foods. 78.6% of the diseases were detected late; however, 17.4% resorted to traditional care. The most commonly diagnosed complications of hypertension were hypertensive heart disease (48.5%), followed by ischaemic heart disease (25.2%), heart failure (10.3%) and stroke (4.9%).

The factors associated with the onset or complications of hypertension at the Sangmélima Referral Hospital are sociodemographic (age, level of education, marital status), clinical and metabolic (hypercholesterolemia), socioeconomic (monthly income, number of direct dependents, food security), behavioral (tobacco consumption, fruit and vegetable consumption, salt/sugar consumption), environmental (place of residence) and health (access to essential technologies for screening and monitoring the disease, use of traditional care).

Overall, the factors that appear to play a predominant role in the onset of hypertension are level of education and food security. These two variables alone are responsible for around 50% of the factors associated with the onset/complication of hypertension. It is the most vulnerable social classes (homemakers aged around 60) with the lowest incomes (< 100.000FCFA), unable to meet their dietary needs because of a high food burden, who are the most affected by hypertension. This study emphasizes socioeconomic and health factors, which are more often than not relegated to second place behind sociodemographic and behavioral factors. The prevention of these two associated factors is a matter of social epidemiology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Tarcisse Biwoele and Luc Onambele; Data curation, Tarcisse Biwoele and Servais Ngo’o; Formal analysis, Servais Ngo’o; Funding acquisition, Ines Aguinaga-Ontoso and Luc Onambele; Investigation, Luc Onambele; Methodology, Tarcisse Biwoele, Ines Aguinaga-Ontoso and Luc Onambele; Project administration, Luc Onambele; Resources, Tarcisse Biwoele and Luc Onambele; Software, Servais Ngo’o; Supervision, Ines Aguinaga-Ontoso, Francisco Guillen-Grima and Luc Onambele; Writing – original draft, Tarcisse Biwoele, Annick Ndoumba, Ines Aguinaga-Ontoso, Servais Ngo’o, Séraphine Ndongo, Sylvie Ambomo, Francisco Guillen-Grima and Luc Onambele; Writing – review & editing, Tarcisse Biwoele, Annick Ndoumba, Ines Aguinaga-Ontoso, Servais Ngo’o, Séraphine Ndongo, Sylvie Ambomo, Francisco Guillen-Grima and Luc Onambele. All authors have read and validated the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This research did not receive any external funding.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted under the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the SSE-UCAC Institutional Ethics Committee (Ethical clearance no. 2024/020641/CEIRSH/ESS/MSP dated 1 February 2024) for studies involving human subjects.

Informed consent

Participants were given information about the study (objective, target). Participants’ verbal consent was a condition for data collection. Participants were treated with respect and free to withdraw their consent at any time during the study.

Data availability

The data are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, Luc ONAMBELE.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. NSO’O Marc Aurèle, Mr. AKONO ASSALE Charles, and Mrs. NYANGONO Aldine Clarisse for data collection and recording, and Mr OUNDI Alexis and Mr SIMOUO Francky for proofreading:

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest arose during this study.

References

- Chaturvedi A, Zhu A, Gadela NV, Prabhakaran D, Jafar TH. Social Determinants of Health and Disparities in Hypertension and Cardiovascular Diseases. Vol. 81, Hypertension. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2024. p. 387-99. [CrossRef]

- Xu S, Wen S, Yang Y, He J, Yang H, Qu Y, et al. Association Between Body Composition Patterns, Cardiovascular Disease, and Risk of Neurodegenerative Disease in the U.K. Biobank. Neurology [Internet]. 2024 Aug 27;103(4). Available from.

- Mbanya J. The prevalence of hypertension in rural and urban Cameroon. Int J Epidemiol. 1998 Apr 1;27(2):181-5. [CrossRef]

- Boateng EB, Ampofo AG. A glimpse into the future: modelling global prevalence of hypertension. BMC Public Health. 2023 Dec 1;23(1). [CrossRef]

- Ebasone PV, Dzudie A, Peer N, Hoover D, Shi Q, Kim HY, et al. Coprevalence and associations of diabetes mellitus and hypertension among people living with HIV/AIDS in Cameroon. AIDS Res Ther. 2024 Dec 1;21(1). [CrossRef]

- Kingue S, Ngoe CN, Menanga AP, Jingi AM, Noubiap JJN, Fesuh B, et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Hypertension in Urban Areas of Cameroon: A Nationwide Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin Hypertens. 2015 Oct 1;17(10):819-24. [CrossRef]

- From Cameroon R. WORKING PAPER. 2016.

- Bilog NC, Mekoulou Ndongo J, Bika Lele EC, Guessogo WR, Assomo-Ndemba PB, Ahmadou, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and components in rural, semi-urban and urban areas in the littoral region in Cameroon: impact of physical activity. J Health Popul Nutr. 2023 Dec 1;42(1). [CrossRef]

- Hamadou B, Jingi AM. Knowledge of Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Prevention Attitudes by the Population of the Deido-Cameroon Health District [Internet]. 2018. Available from: www.hsd-fmsb.org.

- Epacka Ewane M, Honoré Mandengue S, Belle Priso E, Moumbe Tamba S, Bita Fouda A. Screening for cardiovascular disease in students at the University of Douala and the influence of physical activity and sport [Internet]. Available from: http://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/11/77/full/.

- Noah P, Dominique N, De M, Publique LS. ANNUAL ACTIVITY REPORT (January-December 2023) REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Paix-Travail-Patrie HOPITAL DE REFERENCE DE SANGMELIMA.

- Ngeh EN, Lowe A, Garcia C, McLean S. Physiotherapy-Led Health Promotion Strategies for People with or at Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Scoping Review. Vol. 20, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2023. [CrossRef]

- Vernay M, Bonaldi C, Grémy I. Santé publique volume 27 / N° 1 Supplément-janvier-février 2015.

- Zhang J, Wu J, Sun X, Xue H, Shao J, Cai W, et al. Associations of hypertension with the severity and fatality of SARS-CoV-2 infection: A meta-Analysis. Epidemiol Infect. 2020.

- Liew SJ, Lee JT, Tan CS, Koh CHG, Van Dam R, Müller-Riemenschneider F. Sociodemographic factors in relation to hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in a multi-ethnic Asian population: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019 May 1;9(5). [CrossRef]

- Schutte AE, Jafar TH, Poulter NR, Damasceno A, Khan NA, Nilsson PM, et al. Addressing global disparities in blood pressure control: perspectives of the International Society of Hypertension. Vol. 119, Cardiovascular Research. Oxford University Press; 2023. p. 381-409. [CrossRef]

- Kayima J, Nankabirwa J, Sinabulya I, Nakibuuka J, Zhu X, Rahman M, et al. Determinants of hypertension in a young adult Ugandan population in epidemiological transition - The MEPI-CVD survey. BMC Public Health. 2015 Aug 28;15(1). [CrossRef]

- Shen S, Cheng J, Li J, Xie Y, Wang L, Zhou X, et al. Association of marital status with cognitive function in Chinese hypertensive patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2022 Dec 1;22(1). [CrossRef]

- Ramezankhani A, Azizi F, Hadaegh F. Associations of marital status with diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: A long term follow-up study. PLoS One. 2019 Apr 1;14(4). [CrossRef]

- Son M, Heo YJ, Hyun HJ, Kwak HJ. Effects of Marital Status and Income on Hypertension: The Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES). Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. 2022 Nov 1;55(6):506-19. [CrossRef]

- Yazawa A, Inoue Y, Yamamoto T, Watanabe C, Tu R, Kawachi I. Can social support buffer the association between loneliness and hypertension? a cross-sectional study in rural China. PLoS One. 2022 Feb 1;17(2 February). [CrossRef]

- Brown EG, Creaven AM, Gallagher S. Loneliness and cardiovascular reactivity to acute stress in older adults. Psychophysiology. 2022 Jul 1;59(7). [CrossRef]

- Xia N, Li H. Loneliness, Social Isolation, and Cardiovascular Health. Vol. 28, Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. Mary Ann Liebert Inc; 2018. p. 837-51.

- Guo X, Sun R, Cui X, Liu Y, Yang Y, Lin R, et al. Age-Specific Association Between Visit-to-Visit Blood Pressure Variability and Hearing Loss: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Innov Aging. 2024;8(6). [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Lopez JP, Cohen DD, Alarcon-Ariza N, Mogollon-Zehr M, Ney-Salazar D, Chacon-Manosalva MA, et al. Ethnic Differences in the Prevalence of Hypertension in Colombia: Association With Education Level. Am J Hypertens. 2022 Jul 1;35(7):610-8. [CrossRef]

- Naheed A, Islam MA, Sun Y. Low educational status correlates with a high incidence of mortality among hypertensive subjects from Northeast Rural China.

- Suh SH, Song SH, Choi HS, Kim CS, Bae EH, Ma SK, et al. Parental educational status independently predicts the risk of prevalent hypertension in young adults. Sci Rep. 2021 Dec 1;11(1). [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim A, Shafie NH, Esa NM, Shafie SR, Bahari H, Abdullah MA. Mikania micrantha extract inhibits hmg-coa reductase and acat2 and ameliorates hypercholesterolemia and lipid peroxidation in high cholesterol-fed rats. Nutrients. 2020 Oct 1;12(10):1-16.

- Son M, Heo YJ, Hyun HJ, Kwak HJ. Effects of Marital Status and Income on Hypertension: The Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES). Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. 2022;55(6):506-19. [CrossRef]

- Rahman MA. Socioeconomic inequalities in the risk factors of non-communicable diseases (hypertension and diabetes) among Bangladeshi population: Evidence based on population level data analysis. PLoS One. 2022 Sep 1;17(9 September).

- Xiao L, Le C, Wang GY, Fan LM, Cui WL, Liu YN, et al. Socioeconomic and lifestyle determinants of the prevalence of hypertension among elderly individuals in rural southwest China: a structural equation modelling approach. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021 Dec 1;21(1). [CrossRef]

- Mashuri YA, Ng N, Santosa A. Socioeconomic disparities in the burden of hypertension among Indonesian adults - a multilevel analysis. Glob Health Action. 2022;15(1). [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Zhang J, Hu K, Ma L. Association between smoking and hypertension under different PM2.5 and green space exposure: A nationwide cross-sectional study.

- Levin MG, Klarin D, Assimes TL, Freiberg MS, Ingelsson E, Lynch J, et al. Genetics of Smoking and Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Jan 19;4(1):E2034461.

- Yang Z, Zhang J, Hu K, Ma L. Association between smoking and hypertension under different PM2.5 and green space exposure: A nationwide cross-sectional study.

- Singh RB, Nabavizadeh F, Fedacko J, Pella D, Vanova N, Jakabcin P, et al. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension via Indo-Mediterranean Foods, May Be Superior to DASH Diet Intervention. Vol. 15, Nutrients. MDPI; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Canale MP, Noce A, Di Lauro M, Marrone G, Cantelmo M, Cardillo C, et al. Gut dysbiosis and western diet in the pathogenesis of essential arterial hypertension: A narrative review. Vol. 13, Nutrients. MDPI AG; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tain YL, Hsu CN. Maternal High-Fat Diet and Offspring Hypertension. Vol. 23, International Journal of Molecular Sciences. MDPI; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pirkle CM, Guerra RO, Gómez F, Belanger E, Sentell T. Socioecological Factors Associated with Hypertension Awareness and Control Among Older Adults in Brazil and Colombia: Correlational Analysis from the International Mobility in Aging Study. Glob Heart. 2023;18(1). [CrossRef]

- Charchar FJ, Prestes PR, Mills C, Ching SM, Neupane D, Marques FZ, et al. Lifestyle management of hypertension: International Society of Hypertension position paper endorsed by the World Hypertension League and European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2024 Jan 1;42(1):23-49. [CrossRef]

- Schutte AE, Jafar TH, Poulter NR, Damasceno A, Khan NA, Nilsson PM, et al. Addressing global disparities in blood pressure control: perspectives of the International Society of Hypertension. Vol. 119, Cardiovascular Research. Oxford University Press; 2023. p. 381-409. [CrossRef]

- Mogueo A, Defo BK. Patients’ and family caregivers’ experiences and perceptions about factors hampering or facilitating patient empowerment for self-management of hypertension and diabetes in Cameroon. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022 Dec 1;22(1). [CrossRef]

- Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JR, Nkeck JR, Nyaga UF, Bigna JJ. Prevalence of white coat and masked hypertension in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vol. 20, Journal of Clinical Hypertension. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2018. p. 1165-72.

- Jurko A, Minarik M, Jurko T, Tonhajzerova I. White coat hypertension in pediatrics. Vol. 42, Italian Journal of Pediatrics. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2016. [CrossRef]

- Cao R, Yue J, Gao T, Sun G, Yang X. Relations between white coat effect of blood pressure and arterial stiffness. J Clin Hypertens. 2022 Nov 1;24(11):1427-35.

- Mogueo A, Defo BK, Mbanya JC. Healthcare providers’ and policymakers’ experiences and perspectives on barriers and facilitators to chronic disease self-management for people living with hypertension and diabetes in Cameroon. BMC Primary Care. 2022 Dec 1;23(1). [CrossRef]

- Kingue S, Ngoe CN, Menanga AP, Jingi AM, Noubiap JJN, Fesuh B, et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Hypertension in Urban Areas of Cameroon: A Nationwide Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin Hypertens. 2015 Oct 1;17(10):819-24. [CrossRef]

- Xue Z, Li Y, Zhou M, Liu Z, Fan G, Wang X, et al. Traditional Herbal Medicine Discovery for the Treatment and Prevention of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Vol. 12, Frontiers in Pharmacology. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).