1. Background

1.1. Sarcopenia and Frailty Negatively Impact the Longevity of the Mid-Life and Elderly Population

Frailty is an aging-related syndrome that renders the patients more vulnerable to health-related risks, with a significant volume of clinical research aimed at this realm. Ever since Fried et al. presented their “evidence for a phenotype” in the year 2001 [

1], numerous studies engaged definitions and subtypes of frailty, with disability being the inevitable result of this rather new syndrome. The major bulk of literature, however, presented frailty as a common phenomenon amongst community dwelling elderlies. The rate of frail, not necessarily old patients within hospitals is less known and researched. Nevertheless, a retrospective cohort study that was conducted on hospitalized Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) elderly patients, showed that the higher the frailty score was, as defined by the Hospital Frailty Risk Score (HFRS), the greater was the patients’ risk of mortality. This study and others have proven the strong association between frailty and subsequent mortality of hospitalized patients [

2]. A cross-sectional, longitudinal study was conducted to evaluate the potential effect of sarcopenia and frailty on morbidity and mortality, among peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients. In this population, frailty and sarcopenia were determined using the Clinical Frailty Sc ore (CFS), and the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia criteria, respectively. In this study, once again, a positive correlation between sarcopenia, frailty and mortality was found [

3]. Tanaka and co. conducted a prospective study, in which elderly individuals were assessed based on their oral frailty (according to the following: number of natural teeth, chewing ability, articulation, tongue pressure, and subjective eating- and swallowing difficulties) over a 4-year period (spanning from 2012 to 2016). They found a strong correlation between oral frailty at baseline and future frailty, sarcopenia, and mortality [

4]. Pre-frailty and Frailty appear to affect middle-aged as well as elderly patients, suggesting that more spotlights should be directed to middle-aged frail patients [

5].

1.2. Hypothyroidism Is Potentially Associated with Sarcopenia and Frailty.

Hypothyroidism is considered as a background cause for exhaustion (alongside other pathophysiology such as depression, anemia, hypotension, and vitamin B12 deficiency) and therefore, it is recommended by clinical guidelines to be ruled out, as part of the expected management of patients diagnosed as suffering from sarcopenia and frailty [

6]. Virgini and co. did a cross-sectional, prospective study aimed at assessing the potential association between sub-clinical hypo-, and hyperthyroidism with different levels of frailty and sarcopenia. The frailty was determined by using a modified Cardiovascular Health Study Index and their results did not establish such association [

7]. Abdel-Rahman, Mansour and Holley questioned the potential contribution of hypothyroidism to the frailty status of elderlies suffering from chronic kidney disease. Moreover, they hypothesize that supplementation of thyroid hormones could, potentially treat frail elderlies [

8].

1.3. Low ALT Values Serve as a Bio-Marker for Sarcopenia and Frailty

Alanine aminotransferase, catalyzing conversion of pyruvate to the amino acid alanine, and vice versa, taking part in carbohydrate metabolism [

9], plays a major role in several metabolic pathways in various tissues like the liver and muscles. Being an intracellular enzyme, its blood levels are most commonly used to trace and monitor liver tissue damage in a wide range of viral, toxic and ischemic hepatitis. In recent years, evidence accumulated, pointing out the clinical circumstances in which the ALT blood levels are low – a laboratory finding that was generally overlooked. It was shown, that in the absence of liver tissue damage, blood ALT levels serve as a reliable marker for the whole body striated muscles’ mass. Therefore, low-normal ALT levels, when corrected to gender and age, serve as a biomarker for decreased muscle mass and functionality, namely – Sarcopenia and Frailty.

Epidemiologic studies show that while normal ALT levels proved to be protective against overall and cardiovascular mortality [

10], patients with low serum ALT levels, suffering from a myriad of clinical diagnoses in their background, had a high prevalence of sarcopenia and frailty [

10,

11]. A recent study conducted on critically ill, intubated patients found low ALT to serve as a significant marker for extubation failure, making ALT an easy, yet important laboratory value for identifying such patients [

12].

A strong association was established between low ALT levels and other accepted parameters determining sarcopenia and frailty status like the L3SMI score (Striated Muscle Index at the level of L3-vertebra), based on CT imaging analysis of internal medicine patients [

13] and the validated FRAIL Questionnaire [

14] which also serves for frailty screening and diagnosis.

Low ALT values are also associated with increased hospitalization length of stay and higher rates of re-admission [

15], poor clinical outcomes, and higher mortality among variable patients’ populations [

16,

17,

18,

19]: hospitalized patients following COPD exacerbations, heart failure patients, acute coronary syndrome patients staying in the intensive cardiac care unit (ICCU), and patients suffering from atrial fibrillation.

1.4. Aim of the Current Study

Notwithstanding to all the above, the association and prognostic implications of low ALT values amongst patients suffering from hypothyroidism were not investigated although this condition is considered as a risk factor for sarcopenia and frailty. This study aimed to establish, in a retrospective manner, the extent of the potential association of hypothyroidism with sarcopenia and frailty (as indicated by low-normal levels of blood ALT activity) and evaluate the potential negative influences of these comorbidities on patients’ long-term clinical outcomes. We will not be able to assess implications on quality of life and daily functional capacity due to the retrospective nature of our study.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Population

This study population included a sequential 100,000 hospitalized patients to the Chaim Sheba Medical center (the largest tertiary medical center in Israel) beginning from August 2002 until January 2023. This total number of patients was dictated, in an arbitral manner by the software used for data mining. Eligible patients included all those who had both thyroid function tests’ results and blood ALT activity measurements during their hospital stay.

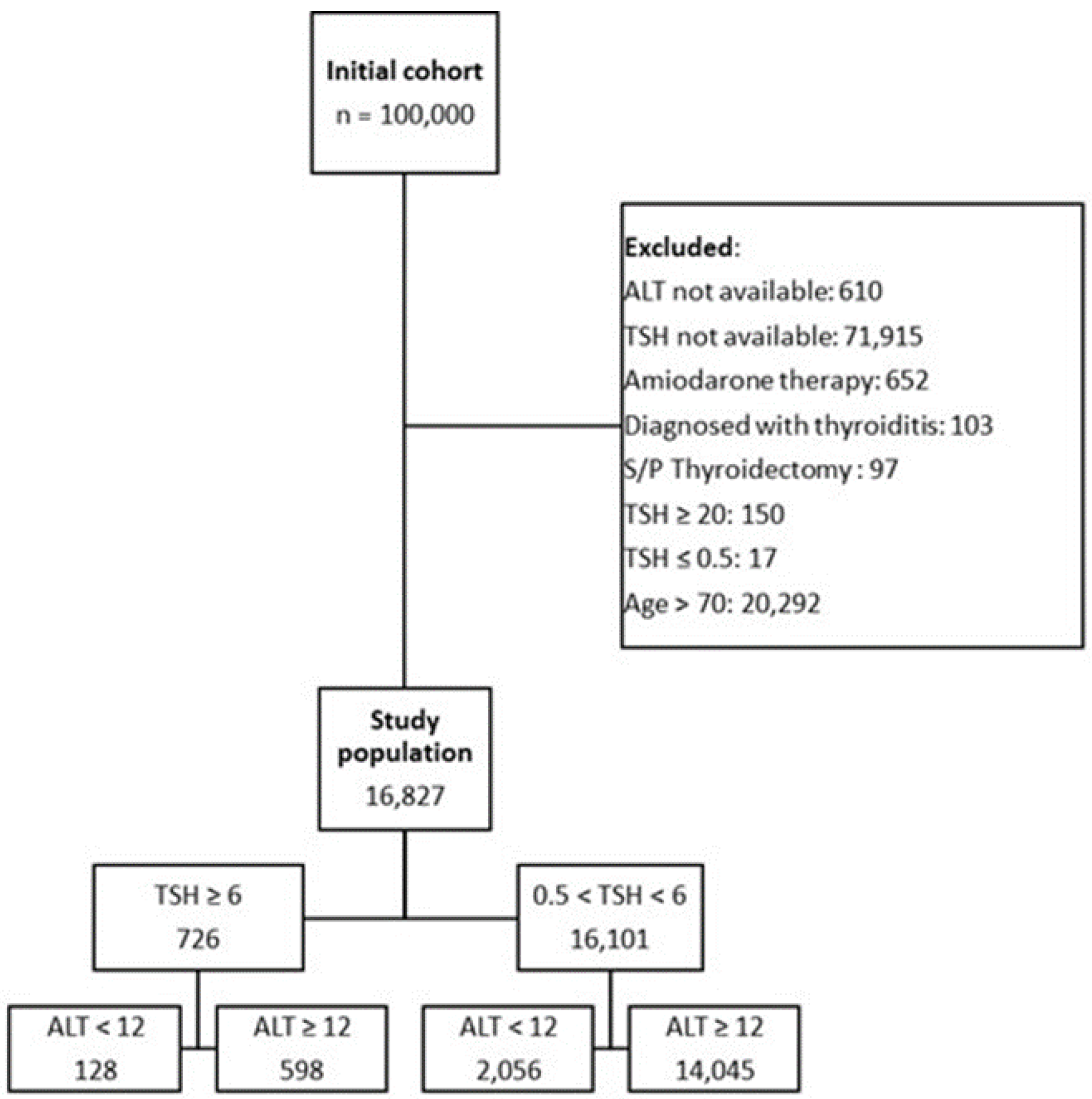

To reliably indicate for sarcopenia and frailty, we restricted the inclusion of patients according to the following rules: We included patients in the age range of 30 to 70 years only, since younger patients are not inclined to suffer from sarcopenia and frailty and older patients will not necessarily benefit from these definitions, suffering from frailty accompanying older age. We sought to define the effects of combined sarcopenia, frailty and hypothyroidism in the middle aged patients. Also, we excluded all patients who had ALT values above the upper limit of normal values (in our institution > 40IU) since such values are arising from lysis of hepatocytes and are commonly indicative of hepatitis and therefore, such ALT levels are not considered as reliable parameter of sarcopenia. Also, we excluded patients who had a diagnosis of thyroiditis whose TSH values do not reflect the chronic activity of their thyroid glands, those who had undergone thyroidectomy and those treated by Amiodarone. The exclusion and partition of the preliminary patients’ cohort to study groups is presented as a CONSORT flow diagram (

Figure 1).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

To make sure that our study sample size is sufficient, we calculated for a significance level of 5% to provide the trial with 80% power. We estimated that 5% of the population will have TSH values greater than 6. Therefore, to ascertain the sample size, we assumed that the ratio between the groups would be 1:20, while 1 and 20 represent those with abnormal and normal TSH values, respectively. Under the assumption that 15% in the abnormal group and 10% in the normal group will have low ALT levels, we assumed that 15% will have low ALT in the abnormal group and 10% will have low ALT in the normal TSH group. Hence, we calculated a sample size (performed using WINPEPI software) of 7,476 patients to be divided to a minimum of 7,120 patients in the normal TSH group while a minimum of 356 patients will be needed in the low-TSH group of patients.

Categorical variables were described as frequencies and percentages. The distribution of continuous variables was tested by a histogram and a Q-Q plot. Continuous variables that distributed normally are presented as mean ± standard deviations, and those that do not are described as median ± IQR [inter-quartile range]. A comparison between groups of categorical variables was done using a ꭓ₂ test, and comparison of continuous variables was made using t-test for independent samples, or by using a Mann-Whitney test. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to estimate the association between the ALT and the TSH category with adjustment for possible confounders. All the statistical analyses will be two-sided, and P > 0.05 will be considered as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were done using SPSS software version 23.

3. Results

Our retrospective analysis included an overall cohort of 100,000 patients of whom 16,827 patients were included in the final analysis. We excluded from analysis the following, partially overlapping groups of patients: over the age of 70 years or below 30 years (for being less relevant when sarcopenia and frailty are looked for: above the age of 70 years, frailty becomes significantly more common and below the age of 30 years it is rare to non-existent), patients with unavailable values of TSH and/or ALT, patients treated by Amiodarone and patients diagnosed with thyroiditis or status post thyroidectomy. It should be stated also that iodine-deficiency, as an etiology for hypothyroidism, is almost non-existent in our patients’ population. Also, we excluded patients with hyperthyroidism (TSH < 0.5 Miu/l) or extreme hypothyroidism (TSH > 20 Miu/l). The total of 16,827 remaining patients included in the analysis were divided into four groups used for comparison of clinical outcomes: patients with normal ALT (robust) and low TSH (euthyroid), those with low ALT (frail) and low TSH (euthyroid), those patients with normal ALT (robust) and high TSH (hypothyroid) and those who were both frail (low ALT) and hypothyroid (high TSH).

Table 1 describe these four groups, detailing their demographic and clinical characteristics: as anticipated, the patients that were both frail and hypothyroid were also predominantly females, had lower albumin blood concentrations, had higher creatinine levels with increased incidence of chronic kidney disease and background malignancies. All the differences reached statistical significance in comparison of the four groups. The following patients’ characteristics that were not significantly different between our study groups were the frequency of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), cerebrovascular accidents and dementia.

3.1. Univariate Analysis

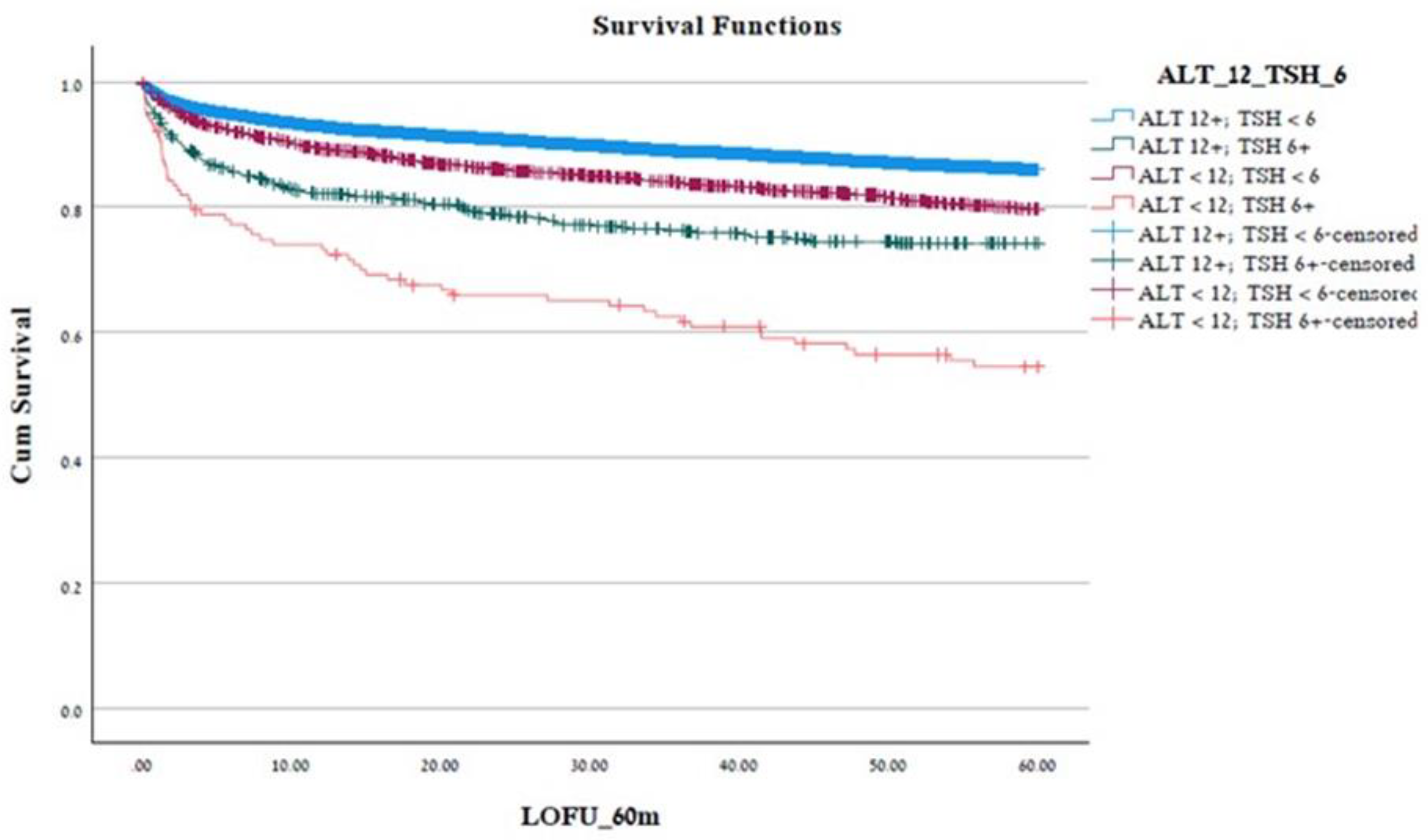

The patients included in the four groups differed, also, in their prospects of survival. As detailed in the Kaplan-Meier, crude analysis of mortality (

Figure 2), the group of the frail and hypothyroid (ALT < 12 IU/L and TSH > 6 MIU/L) patients had significantly shorter survival while the group of robust and euthyroid (ALT > 12 IU/L and TSH < 6 MIU/L) patients had the longest survival chances.

Table 2 include a univariate analysis relating to the risk of mortality: relative to a median survival duration of 54.19 ± 0.14 months of patients in the reference group (robust & euthyroid, (ALT < 12 IU/L and TSH < 6 MIU/L)), the frail and hypothyroid patients survived only for 39.32 ± 2.26 months (p < 0.001).

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

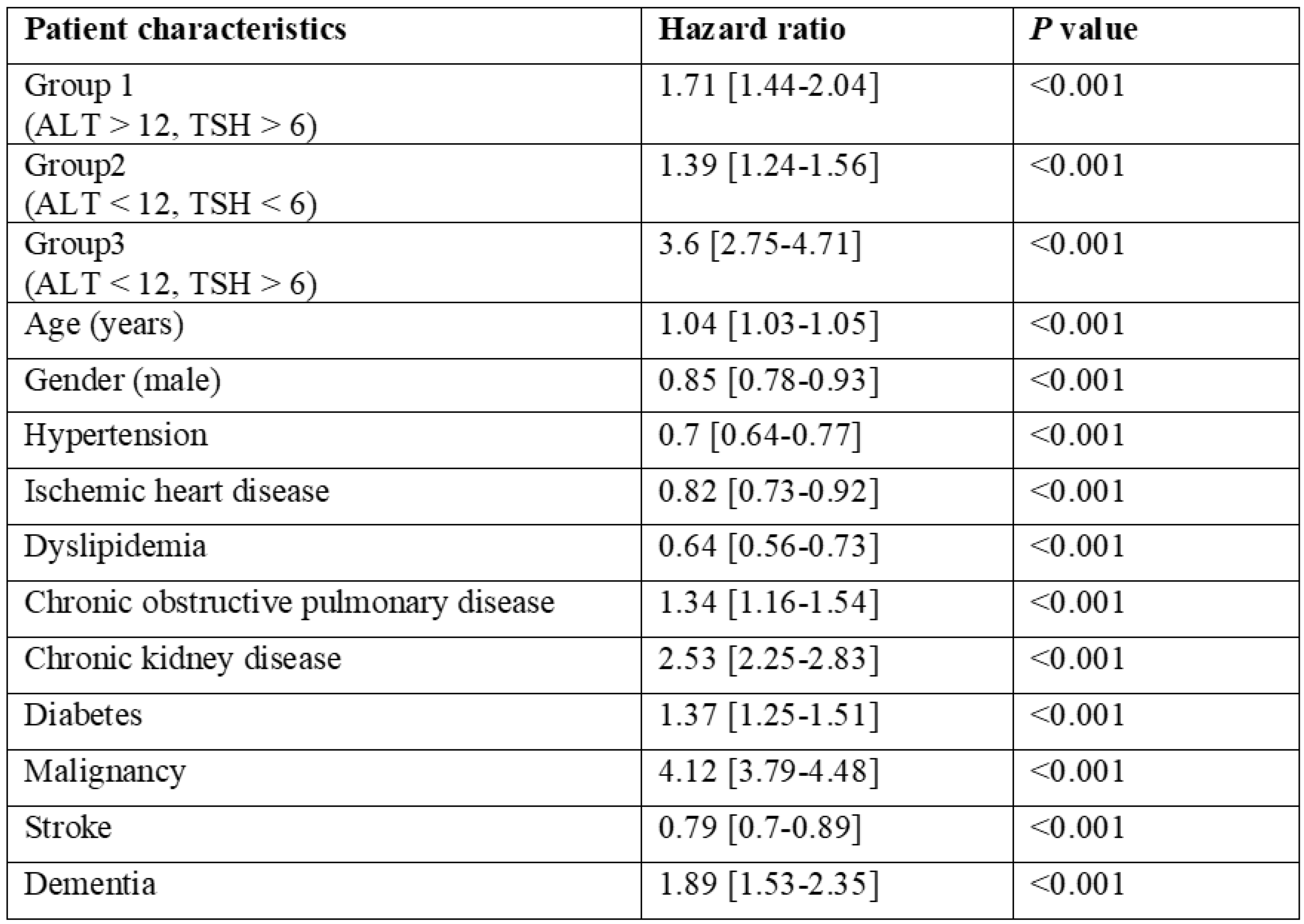

A multivariate analysis model (

Table 3) included all patients’ characteristics that had statistically significant impact on patients’ survival in the univariate analysis. In this model, still, the frail and hypothyroid group of patients (ALT < 12IU/L and TSH > 6 Miu/l) had a statistically significant increased risk of mortality in the for coming 5 years (HR = 3.6; CI 2.75-4.71; p < 0.001). Patients who were hypothyroid but were considered robust (ALT > 12 IU/L and TSH > 6 Miu/l) were also independently at a higher risk of mortality (1.71 [95% CI 1.44 – 2.04] and those patients who were frail and euthyroid (ALT < 12 IU/L and TSH < 6 Miu/l) had a higher risk of mortality (HR = 1.39, 95% CI 1.24 – 1.56). Other patients’ characteristics that were found to be independently associated with increased risk of mortality in a multi-variate analysis were: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (increased by 34%), chronic kidney disease (increased by 153%), diabetes mellitus (increased by 37%), active malignancy (increased by 312%) and concurrent dementia (increasing the risk of mortality by 89%).

4. Discussion

It seems that even though the thyroid glands importance and functions are known for more than decades, the full spectrum of impact of thyroid hormones on the human tissues’ cells is not fully elucidated. In their review, Mandoza and Hollenberg, detail novel mechanisms by which the thyroid hormones’ activities differentiate according to receptor functions and intracellular modulations of different body tissue cells [

20]. In his editorial relating to thyroid functions and longevity, Peeters describe the increasing TSH levels as people get older and the difficulties in genuine assessment of thyroid functionality in face of accumulating chronic diseases and elongating lists of medications. Nevertheless, although he concludes that decreased thyroid function is part of getting old, he did not associate this phenomenon with either sarcopenia or frailty [

21].

Indeed, hypothyroidism is a common phenomenon in both community residing patients and hospitalized patients as well, as they get older. Past research has associated hypothyroidism with a myriad of pathologies and shortened survival [

22,

23]. In reviews that do not concentrate on mortality, the disability associated with hypothyroidism is emphasized [

24]. In their narrative review, Ettelson and Papaleontio extend the therapeutic targets for hypothyroid patients: beyond normalization of TSH values, they encourage clinicians to peruse better quality of life outcomes, using the PROMS, patients reported outcome measures [

25]. Their attitude towards relating to hypothyroidism as a multisystem disease, rather than a disease of “a gland” aligns with the strong association of hypothyroidism, sarcopenia, and frailty. In a publication by Lee et al. [

26] relying on data retrieved form the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2013 to 2015), a statistically significant correlation was found between hypothyroidism, both clinical and subclinical and frailty. In patients with frank hypothyroidism, they found a correlation between TSH levels and the relative risk for development of frailty. Their frailty diagnosis relied on the Fried frailty phenotype and therefore, could not apply to large populations by simply screening their health-related characteristics. This is not the case when screening for sarcopenia and frailty rely on low ALT blood levels, data that is readily available whenever patients did their routine blood tests in the past six months.

Low ALT values, when used as biomarker for sarcopenia and frailty, were already shown to be associated with shortened survival of diverse patients’ populations, as presented above. The association of diagnosing both hypothyroidism and frailty via simple blood testing is indeed tempting for clinicians and enables sarcopenia diagnosis that is beyond the “eyeballing” old methods of assessment.

In the current study, we did a retrospective analysis of hospitalized patients regarding their hypothyroidism status (according to past TSH measurements) and simultaneously, their status of being either robust or sarcopenic and frail (according to their concurrent ALT measurements). Sarcopenia and frailty are also known to be associated with increased risk of falls, hospitalizations [

15,

18] and mortality [

13,

19,

27,

28]. The combination of both disease states, aided by low ALT values as a biomarker for sarcopenia and frailty was never questioned, as far as we know, as to the extent it would affect patients’ long-term prognosis.

Alongside past measurements of TSH levels as indicator of hypothyroidism, we relied on several recent publications, showing that low ALT levels could serve as retrospective biomarker for sarcopenia and frailty [

19,

27,

29]. We grouped our patients into four groups according to their TSH and ALT levels (robust and euthyroid, robust and hypothyroid, frail and euthyroid, frail and hypothyroid) and found that the combination of hypothyroidism and frailty is indeed, associated with significantly shortened survival.

Modern views of personalized medicine are concentrating on the patients as a whole. This, “gestalt” view of patients is complementary to the precise medicine strategies which concentrate on the disease state rather than the patients. Our findings suggest that the combination of hypothyroidism and frailty should help clinicians to better suit both diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to their patients. For example, whenever there is a doubt regarding the need to address sub-clinical hypothyroidism with supplementary levothyroxine, clinicians should have the complete “picture” of their patient by measuring his/her ALT levels. If these levels are suggestive of sarcopenia and frailty (ALT < 12 IU/L) it would only be prudent to initiate supplemental levothyroxine. The opposite is also true: there are little means, currently, to revers sarcopenia and frailty. Nevertheless, these patients should be timely screened for potential, so called, sub clinical hypothyroidism that should be addressed pharmacologically.

5. Conclusions

Clinicians should be aware to the relatively common, co-existence of hypothyroidism and sarcopenia. These comorbidities should be considered as a significantly damaging patients’ quality of life and at times, shortening patients’ survival and therefore, be promptly addressed – either by correcting thyroid function tests/reversing etiologies of acquired hypothyroidism and addressing potential causes for sarcopenia and frailty such as poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. The main contribution of our work is the fact that both morbidities were diagnosed by readily available laboratory tests. Both low ALT and increased TSH levels could be monitored in middle aged men and women, as was our cohort of patients.

Limitations

This was a retrospective, single center study and as such, should be followed by long-term, prospective interventional studies. The results should be generalized with caution regarding other patients’ populations. Causes of hypothyroidism are not detailed in this manuscript. We excluded some but it is possible that certain causes of hypothyroidism might be directly associated with sarcopenia and frailty. This possibility cannot be ruled out based on our study results.

Conflicts of Interests’ declaration

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2024 Jan 29];56(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11253156/. [CrossRef]

- Ajibawo T, Okunowo O. Higher Hospital Frailty Risk Score Is an Independent Predictor of In-Hospital Mortality in Hospitalized Older Adults with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Geriatrics (Basel) [Internet]. 2022 Nov 14 [cited 2022 Dec 15];7(6):127. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36412616/. [CrossRef]

- Kamijo Y, Kanda E, Ishibashi Y, Yoshida M. Sarcopenia and Frailty in PD: Impact on Mortality, Malnutrition, and Inflammation. Perit Dial Int. 2018;38(6):447–54. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka T, Takahashi K, Hirano H, Kikutani T, Watanabe Y, Ohara Y, et al. Oral Frailty as a Risk Factor for Physical Frailty and Mortality in Community-Dwelling Elderly. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci [Internet]. 2018 Nov 10 [cited 2022 Dec 15];73(12):1661–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29161342/. [CrossRef]

- Hanlon P, Nicholl BI, Jani BD, Lee D, McQueenie R, Mair FS. Frailty and pre-frailty in middle-aged and older adults and its association with multimorbidity and mortality: a prospective analysis of 493 737 UK Biobank participants. Lancet Public Health [Internet]. 2018 Jul 1 [cited 2022 Dec 15];3(7):e323–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29908859/. [CrossRef]

- Dent E, Morley JE, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Woodhouse L, Rodríguez-Mañas L, Fried LP, et al. Physical Frailty: ICFSR International Clinical Practice Guidelines for Identification and Management. J Nutr Health Aging [Internet]. 2019 Nov 1 [cited 2022 Dec 10];23(9):771. Available from:/pmc/articles/PMC6800406/. [CrossRef]

- Virgini VS, Rodondi N, Cawthon PM, Harrison SL, Hoffman AR, Orwoll ES, et al. Subclinical Thyroid Dysfunction and Frailty Among Older Men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab [Internet]. 2015 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Dec 10];100(12):4524–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26495751/. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman EM, Mansour W, Holley JL. Hypothesis: Thyroid Hormone Abnormalities and Frailty in Elderly Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Hypothesis. Semin Dial [Internet]. 2010 May 1 [cited 2022 Dec 10];23(3):317–23. Available from: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.sheba.idm.oclc.org/doi/full/10.1111/j.1525-139X.2010.00736.x. [CrossRef]

- Segev A, Itelman E, Avaky C, Negru L, Shenhav-Saltzman G, Grupper A, et al. Low ALT Levels Associated with Poor Outcomes in 8700 Hospitalized Heart Failure Patients. J Clin Med. 2020 Sep 30;9(10). [CrossRef]

- Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, de Vincentis A, Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Antonelli Incalzi R, Picardi A. Low Alanine Aminotransferase Levels in the Elderly Population: Frailty, Disability, Sarcopenia, and Reduced Survival. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018 Jun 14;73(7):925–30. [CrossRef]

- Ramati E, Israel A, Tal Kessler, Petz-Sinuani N, Sela BA, Idan Goren, et al. [Low ALT activity amongst patients hospitalized in internal medicine wards is a widespread phenomenon associated with low vitamin B6 levels in their blood]. Harefuah. 2015 Feb;154(2):89–93, 137.

- Weber Y, Epstein D, Miller A, Segal G, Berger G. Association of Low Alanine Aminotransferase Values with Extubation Failure in Adult Critically Ill Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2021 Jul 25;10(15). [CrossRef]

- Portal D, Melamed G, Segal G, Itelman E. Sarcopenia as Manifested by L3SMI Is Associated with Increased Long-Term Mortality amongst Internal Medicine Patients-A Prospective Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2022 Jun 17;11(12). [CrossRef]

- Irina G, Refaela C, Adi B, Avia D, Liron H, Chen A, et al. Low Blood ALT Activity and High FRAIL Questionnaire Scores Correlate with Increased Mortality and with Each Other. A Prospective Study in the Internal Medicine Department. J Clin Med. 2018 Oct 25;7(11). [CrossRef]

- Anani S, Goldhaber G, Brom A, Lasman N, Turpashvili N, Shenhav-Saltzman G, et al. Frailty and Sarcopenia Assessment upon HospitalAdmission to Internal Medicine Predicts Length ofHospital Stay and Re-Admission: A ProspectiveStudy of 980 Patients. J Clin Med. 2020 Aug 17;9(8).

- Lasman N, Shalom M, Turpashvili N, Goldhaber G, Lifshitz Y, Leibowitz E, et al. Baseline low ALT activity is associated with increased long-term mortality after COPD exacerbations. BMC Pulm Med. 2020 May 11;20(1):133. [CrossRef]

- Segev A, Itelman E, Beigel R, Segal G, Chernomordik F, Matetzky S, et al. Low ALT levels are associated with poor outcomes in acute coronary syndrome patients in the intensive cardiac care unit. J Cardiol. 2022 Mar;79(3):385–90. [CrossRef]

- Segev A, Itelman E, Avaky C, Negru L, Shenhav-Saltzman G, Grupper A, et al. Low ALT Levels Associated with Poor Outcomes in 8700 Hospitalized Heart Failure Patients. J Clin Med. 2020 Sep 30;9(10). [CrossRef]

- Saito Y, Okumura Y, Nagashima K, Fukamachi D, Yokoyama K, Matsumoto N, et al. Low alanine aminotransferase levels are independently associated with mortality risk in patients with atrial fibrillation. Sci Rep. 2022 Jul 16;12(1):12183. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza A, Hollenberg AN. New Insights into Thyroid Hormone Action. Pharmacol Ther [Internet]. 2017 May 1 [cited 2024 Feb 3];173:135. Available from:/pmc/articles/PMC5407910/. [CrossRef]

- Peeters, RP. Thyroid Function and Longevity: New Insights into an Old Dilemma. 2009 [cited 2024 Feb 3]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/94/12/4658/2596319. [CrossRef]

- Rodondi N, den Elzen WPJ, Bauer DC, Cappola AR, Razvi S, Walsh JP, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. JAMA. 2010 Sep 22;304(12):1365–74. [CrossRef]

- Inoue K, Ritz B, Brent GA, Ebrahimi R, Rhee CM, Leung AM. Association of Subclinical Hypothyroidism and Cardiovascular Disease With Mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920745. [CrossRef]

- Kalra S, Unnikrishnan A, Sahay R. The global burden of thyroid disease. Thyroid Research and Practice [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2024 Jan 29];10(3):89. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/trap/fulltext/2013/10030/the_global_burden_of_thyroid_disease.1.aspx25.

- Ettleson MD, Papaleontiou M. Evaluating health outcomes in the treatment of hypothyroidism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) [Internet]. 2022 Oct 18 [cited 2024 Jan 29];13. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36329885/. [CrossRef]

- Lee YJ, Kim MH, Lim DJ, Lee JM, Chang SA, Lee J. Exploring the Association between Thyroid Function and Frailty: Insights from Representative Korean Data. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) [Internet]. 2023 Dec 31 [cited 2024 Jan 29];38(6):729–38. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37915301/. [CrossRef]

- Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, De Vincentis A, Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Antonelli Incalzi R, Picardi A. Low Alanine Aminotransferase Levels in the Elderly Population: Frailty, Disability, Sarcopenia, and Reduced Survival. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci [Internet]. 2018 Jun 14 [cited 2023 Apr 2];73(7):925–30. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28633440/. [CrossRef]

- Uliel N, Segal G, Perri A, Turpashvili N, Kassif Lerner R, Itelman E. Low ALT, a marker of sarcopenia and frailty, is associated with shortened survival amongst myelodysplastic syndrome patients: A retrospective study. Medicine. 2023 Apr 25;102(17):e33659. [CrossRef]

- Chung SM, Moon JS, Yoon JS, Won KC, Lee HW. Low alanine aminotransferase levels predict low muscle strength in older patients with diabetes: A nationwide cross-sectional study in Korea. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020 Apr;20(4):271–6. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).