Submitted:

02 September 2024

Posted:

03 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

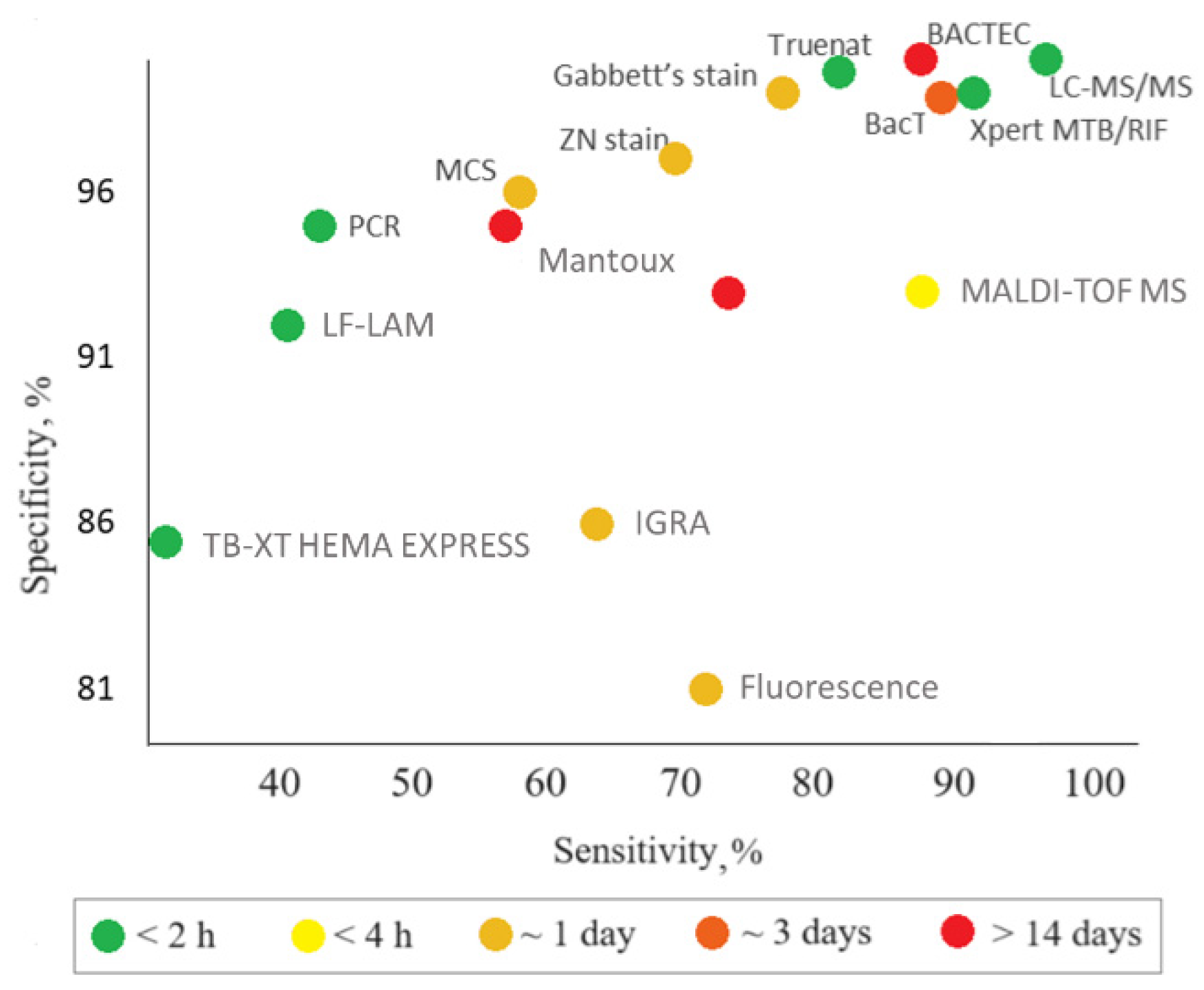

2. Current Tuberculosis Diagnostic Methods

2.1. Molecular Diagnostic Tests

2.2. Tuberculosis Tests Based on T-Cell Analysis

2.3. Cultural Methods

2.4. Skin Tests

2.5. Tests Based on Mycobacterium Staining

2.6. Other Methods

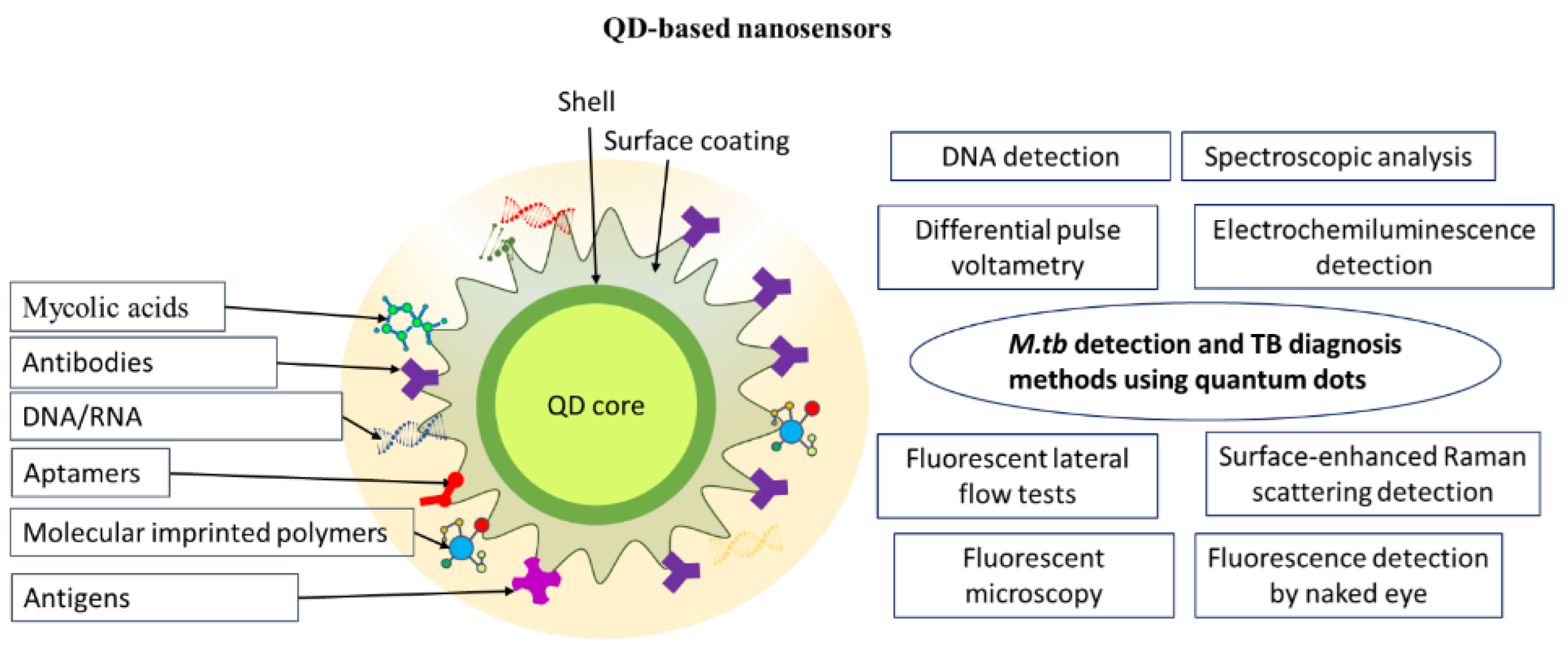

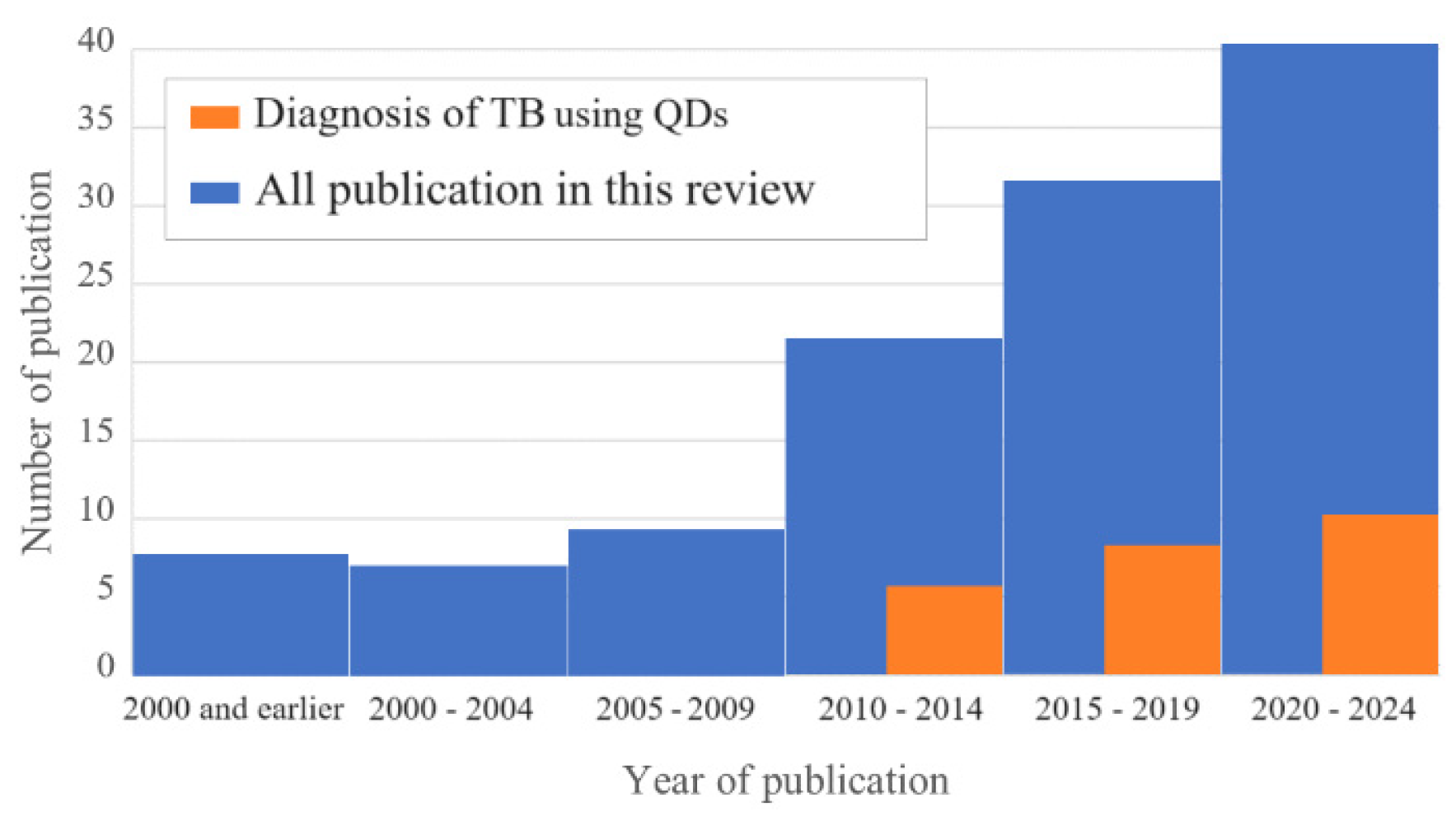

3. Quantum Dot–Based Nanosensors for M. Tuberculosis Detection and Tuberculosis Diagnosis

4. Summary and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Global Health Observatory: SDG Target 3.3 Communicable diseases. Available online: https://Www.Who.Int/Data/Gho/Data/Themes/Topics/Sdg-Target-3_3-Communicable-Diseases.

- Tuberculosis in Women, World Health Organization, Fact Sheet October 2016. Available online: http://Www.Who.Int/Tb/Areas-of-Work/Population-Groups/Gender/En/.

- Chakaya, J.; Khan, M.; Ntoumi, F.; Aklillu, E.; Fatima, R.; Mwaba, P.; Kapata, N.; Mfinanga, S.; Hasnain, S.E.; Katoto, P.D.M.C.; et al. Global Tuberculosis Report 2020 – Reflections on the global TB burden, treatment and prevention efforts. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 113, S7–S12. [CrossRef]

- Maddineni, M.; Panda, M. Pulmonary tuberculosis in a young pregnant female: Challenges in diagnosis and management. Infect. Dis. Obst. Gynecol. 2008, 2008, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, X.; Wen, J.; Tang, D.; Qi, M.; He, J. Host factors associated with false negative results in an interferon-γ release assay in adults with active tuberculosis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22900. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on the Management of Latent Tuberculosis Infection. World Health Organization, 2015.

- Yang, X.; Fan, S.; Ma, Y.; Chen, H.; Xu, J.-F.; Pi, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, G. Current progress of functional nanobiosensors for potential tuberculosis diagnosis: The novel way for TB control? Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1036678. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Perveen, S.; Negi, A.; Sharma, R. Evolution of tuberculosis diagnostics: From molecular strategies to nanodiagnostics. Tuberculosis 2023, 140, 102340. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Singh, A.; Singh, S. Diagnosis of tuberculosis: Nanodiagnostics approaches. In NanoBioMedicine; Saxena, S.K., Khurana, S.M.P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 261–283 ISBN 978-981-329-897-2.

- Jin, T.; Fei, B.; Zhang, Y.; He, X. The diagnostic value of polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis to distinguish intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease: A meta-analysis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 3. [CrossRef]

- Steingart, K.R.; Schiller, I.; Horne, D.J.; Pai, M.; Boehme, C.C.; Dendukuri, N. Xpert MTB/RIF assay for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ssengooba, W.; Katamba, A.; Sserubiri, J.; Semugenze, D.; Nyombi, A.; Byaruhanga, R.; Turyahabwe, S.; Joloba, M.L. Performance evaluation of Truenat MTB and Truenat MTB-RIF DX assays in comparison to Gene XPERT MTB/RIF Ultra for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in Uganda. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 190. [CrossRef]

- Bjerrum, S.; Schiller, I.; Dendukuri, N.; Kohli, M.; Nathavitharana, R.R.; Zwerling, A.A.; Denkinger, C.M.; Steingart, K.R.; Shah, M. Lateral flow urine lipoarabinomannan assay for detecting active tuberculosis in people living with HIV. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Manga, S.; Perales, R.; Reaño, M.; D’Ambrosio, L.; Migliori, G.B.; Amicosante, M. Performance of a lateral flow immunochromatography test for the rapid diagnosis of active tuberculosis in a large multicentre study in areas with different clinical settings and tuberculosis exposure levels. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, 3307–3313. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Nakagawa, A.; Takamori, M.; Abe, S.; Ueno, D.; Horita, N.; Kato, S.; Seki, N. Diagnostic accuracy of the interferon-gamma release assay in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients with suspected tuberculosis infection: A meta-analysis. Infection 2022, 50, 597–606. [CrossRef]

- Tortoli, E.; Mandler, F.; Tronci, M.; Penati, V.; Sbaraglia, G.; Costa, D.; Montini, G.; Predominato, M.; Riva, R.; Passerini Tosi, C.; et al. Multicenter evaluation of mycobacteria growth indicator tube (MGIT) compared with the BACTEC radiometric method, BBL biphasic growth medium and Löwenstein—Jensen medium. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 1997, 3, 468–473. [CrossRef]

- Cruciani, M.; Scarparo, C.; Malena, M.; Bosco, O.; Serpelloni, G.; Mengoli, C. Meta-analysis of BACTEC MGIT 960 and BACTEC 460 TB, with or without solid media, for detection of mycobacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 2321–2325. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.R.; Sardiñas, M.; Garcia, G.; Mederos, L.M.; Díaz, R. Evaluation of BacT/ALERT 3D system for mycobacteria isolates. J. Tuberc. Res. 2014, 2, 59–64. [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.N.; Schechter, C.B.; Adler, J.J. Interpretation of the tuberculin skin test. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1995, 10, 635–642. [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, M.M.; Bakr, W.M.K.; Hussien, S.M.; Amine, A.E.K. Diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis using Ziehl–Neelsen stain or cold staining techniques? J. Egypt. Pub. Health Assoc. 2016, 91, 39–43. [CrossRef]

- Cattamanchi, A.; Davis, J.L.; Worodria, W.; den Boon, S.; Yoo, S.; Matovu, J.; Kiidha, J.; Nankya, F.; Kyeyune, R.; Byanyima, P.; et al. Sensitivity and specificity of fluorescence microscopy for diagnosing pulmonary tuberculosis in a high HIV prevalence setting. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2009, 13, 1130–1136.

- Pinto, L.M.; Pai, M.; Dheda, K.; Schwartzman, K.; Menzies, D.; Steingart, K.R. Scoring systems using chest radiographic features for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in adults: A systematic review. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 42, 480–494. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Xu, B.; Lin, Y.; Yang, X.; Tong, J.; Huang, C. Clinical performance of nucleotide MALDI-TOF-MS in the rapid diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis and drug resistance. Tuberculosis 2023, 143, 102411. [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, J.; Bacchetti, P.; Esmail, A.; Reckers, A.; Aguilar, D.; Wen, A.; Huo, S.; Muyindike, W.R.; Hahn, J.A.; Dheda, K.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay in small hair samples for rifampin-resistant tuberculosis drug concentrations in a routine care setting. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 99. [CrossRef]

- Nsubuga, G.; Kennedy, S.; Rani, Y.; Hafiz, Z.; Kim, S.; Ruhwald, M.; Alland, D.; Ellner, J.; Joloba, M.; Dorman, S.E.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the NOVA tuberculosis total antibody rapid test for detection of pulmonary tuberculosis and infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Tuberc. Other Mycobacter. Dis. 2023, 31, 100362. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Tewari, R.; Dhatwalia, S.K.; Yadav, R.; Behera, D.; Sethi, S. A loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 219–225. [CrossRef]

- The Use of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (TB-LAMP) for the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Policy Guidance; WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2016; ISBN 978-92-4-151118-6.

- Horne, D.J.; Kohli, M.; Zifodya, J.S.; Schiller, I.; Dendukuri, N.; Tollefson, D.; Schumacher, S.G.; Ochodo, E.A.; Pai, M.; Steingart, K.R. Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019. [CrossRef]

- Aainouss, A.; Momen, Gh.; Belghiti, A.; Bennani, K.; Lamaammal, A.; Chetioui, F.; Messaoudi, M.; Blaghen, M.; Mouslim, J.; Khyatti, M.; et al. Performance of GeneXpert MTB/RIF in the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in Morocco. Rus. J. Infect. Immun. 2021, 12, 78–84. [CrossRef]

- Ngangue, Y.R.; Mbuli, C.; Neh, A.; Nshom, E.; Koudjou, A.; Palmer, D.; Ndi, N.N.; Qin, Z.Z.; Creswell, J.; Mbassa, V.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Truenat MTB Plus assay and comparison with the Xpert MTB/RIF assay to detect tuberculosis among hospital outpatients in Cameroon. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 60, e00155-22. [CrossRef]

- Sevastyanova, E.V.; Smirnova, T.G.; Larionova, E.E.; Chernousova, L.N. Detection of mycobacteria by culture inoculation. Liquid media and automated systems. Bulle. TsNIIT 2020, 88–95. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Park, K.U.; Park, J.O.; Chang, H.E.; Song, J.; Choe, G. Rapid, sensitive, and specific detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by real-time PCR on paraffin-embedded human tissues. J. Mol. Diagn. 2011, 13, 390–394. [CrossRef]

- Itani, L.Y.; Cherry, M.A.; Araj, G.F. Efficacy of BACTEC TB in the rapid confirmatory diagnosis of mycobacterial infections: A Lebanese tertiary care center experience. J. Med. Liban. 2005, 53, 208–212.

- Campelo, T.A.; Cardoso De Sousa, P.R.; Nogueira, L.D.L.; Frota, C.C.; Zuquim Antas, P.R. Revisiting the methods for detecting mycobacterium tuberculosis: What has the new millennium brought thus far? Access Microbio. 2021, 3. [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, R.; Kowalski, K.; Janiszewska-Drobinska, B.; Druszczyńska, M. Rapid method for Mycobacterium tuberculosis identification using electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry analysis of mycolic acids. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 76, 298–305. [CrossRef]

- El Khéchine, A.; Couderc, C.; Flaudrops, C.; Raoult, D.; Drancourt, M. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry identification of mycobacteria in routine clinical practice. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24720. [CrossRef]

- Bacanelli, G.; Araujo, F.R.; Verbisck, N.V. Improved MALDI-TOF MS identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by use of an enhanced cell disruption protocol. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1692. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.N.; French, D.; Jannetto, P.J.; Rappold, B.A.; Clarke, W.A. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry for clinical diagnostics. Na.t Rev. Meth. Primers 2022, 2, 96. [CrossRef]

- Malo, A.; Kellermann, T.; Ignatius, E.H.; Dooley, K.E.; Dawson, R.; Joubert, A.; Norman, J.; Castel, S.; Wiesner, L. A Validated liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry assay for the analysis of pretomanid in plasma samples from pulmonary tuberculosis patients. J. Pharmac. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 195, 113885. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, S.; Zhao, W.; Deng, J.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, T.; Wen, S.A.; Guo, H.; Li, L.; Yuan, J.; et al. A peptidomic approach to identify novel antigen biomarkers for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2022, 15, 4617–4626. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Song, B.; Jiang, H.; Yu, K.; Zhong, D. A liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry method for the simultaneous quantification of isoniazid and ethambutol in human plasma. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2005, 19, 2591–2596. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Ma, N. An overview of recent advances in quantum dots for biomedical applications. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2014, 124, 118–131. [CrossRef]

- Medintz, I.L.; Uyeda, H.T.; Goldman, E.R.; Mattoussi, H. Quantum dot bioconjugates for imaging, labelling and sensing. Nat. Mat. 2005, 4, 435–446. [CrossRef]

- Brkić, S. Applicability of quantum dots in biomedical science. In Ionizing Radiation Effects and Applications; Djezzar, B., Ed.; InTech, 2018. ISBN 978-953-51-3953-9.

- Samokhvalov, P.S.; Karaulov, A.V.; Nabiev, I.R. Control of the photoluminescence lifetime of quantum dots by engineering their shell structure. Opt. Spektrosc. 2023, 131, 1262–1267 [in Russian]. [CrossRef]

- Bilan, R.; Nabiev, I.; Sukhanova, A. quantum dot-based nanotools for bioimaging, diagnostics, and drug delivery. ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 2103–2114. [CrossRef]

- Sukhanova, A.; Ramos-Gomes, F.; Chames, P.; Sokolov, P.; Baty, D.; Alves, F.; Nabiev, I. Multiphoton deep-tissue imaging of micrometastases and disseminated cancer cells using conjugates of quantum dots and single-domain antibodies. In Multiplexed Imaging; Zamir, E., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, 2021; Volume 2350, pp. 105–123 ISBN 978-1-07-161592-8.

- Sokolov, P.; Samokhvalov, P.; Sukhanova, A.; Nabiev, I. Biosensors based on inorganic composite fluorescent hydrogels. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1748. [CrossRef]

- Hafian, H.; Sukhanova, A.; Turini, M.; Chames, P.; Baty, D.; Pluot, M.; Cohen, J.H.M.; Nabiev, I.; Millot, J.-M. Multiphoton imaging of tumor biomarkers with conjugates of single-domain antibodies and quantum dots. Nanomedicine: NBM 2014, 10, 1701–1709. [CrossRef]

- Bilan, R.; Fleury, F.; Nabiev, I.; Sukhanova, A. Quantum dot surface chemistry and functionalization for cell targeting and imaging. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015, 26, 609–624. [CrossRef]

- Sukhanova, A.; Even-Desrumeaux, K.; Kisserli, A.; Tabary, T.; Reveil, B.; Millot, J.-M.; Chames, P.; Baty, D.; Artemyev, M.; Oleinikov, V.; et al. Oriented conjugates of single-domain antibodies and quantum dots: Toward a new generation of ultrasmall diagnostic nanoprobes. Nanomedicine: NBM 2012, 8, 516–525. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Youn, Y.H.; Kwon, I.K.; Ko, N.R. Recent advances in quantum dots for biomedical applications. J. Pharmac. Invest. 2018, 48, 209–214. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xu, K.; Taratula, O.; Farsad, K. Applications of nanoparticles in biomedical imaging. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 799–819. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, N.; Chan, V. Recent advances in silicon quantum dot-based fluorescent biosensors. Biosensors 2023, 13, 311. [CrossRef]

- Brazhnik, K.; Nabiev, I.; Sukhanova, A. Oriented conjugation of single-domain antibodies and quantum dots. In Quantum Dots: Applications in Biology; Fontes, A., Santos, B.S., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, 2014; Volume 1199, pp. 129–140 ISBN 978-1-4939-1279-7.

- Brazhnik, K.; Nabiev, I.; Sukhanova, A. Advanced procedure for oriented conjugation of full-size antibodies with quantum dots. In Quantum Dots: Applications in Biology; Fontes, A., Santos, B.S., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, 2014; Volume 1199, pp. 55–66 ISBN 978-1-4939-1279-7.

- Biju, V. Chemical modifications and bioconjugate reactions of nanomaterials for sensing, imaging, drug delivery and therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 744–764. [CrossRef]

- Bilan, R.S.; Krivenkov, V.A.; Berestovoy, M.A.; Efimov, A.E.; Agapov, I.I.; Samokhvalov, P.S.; Nabiev, I.; Sukhanova, A. Engineering of optically encoded microbeads with FRET-free spatially separated quantum-dot layers for multiplexed assays. ChemPhysChem 2017, 18, 970–979. [CrossRef]

- Rousserie, G.; Sukhanova, A.; Even-Desrumeaux, K.; Fleury, F.; Chames, P.; Baty, D.; Oleinikov, V.; Pluot, M.; Cohen, J.H.M.; Nabiev, I. Semiconductor quantum dots for multiplexed bio-detection on solid-state microarrays. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2010, 74, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, L.H.; Kumari, S. Nanocarriers for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Sci. Res. 2021, 65, 33–37. [CrossRef]

- El-Shabasy, R.M.; Zahran, M.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Maghraby, Y.R.; Nayel, M. Advances in the fabrication of potential nanomaterials for diagnosis and effective treatment of tuberculosis. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 1772–1782. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Pandey, N.; Singh, K.; Ahmad, S.; Khubaib, M.; Sharma, R. Recent advances in nanocarrier based therapeutic and diagnostic approaches in tuberculosis. Prec. Nanomed. 2023, 6. [CrossRef]

- Pati, R.; Sahu, R.; Panda, J.; Sonawane, A. Encapsulation of zinc-rifampicin complex into transferrin-conjugated silver quantum-dots improves its antimycobacterial activity and stability and facilitates drug delivery into macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24184. [CrossRef]

- Gliddon, H.D.; Howes, P.D.; Kaforou, M.; Levin, M.; Stevens, M.M. A nucleic acid strand displacement system for the multiplexed detection of tuberculosis-specific mRNA using quantum dots. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 10087–10095. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, J.; Shi, S.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, P.; Zeng, G.; Jiang, Z. Detection of interferon-gamma for latent tuberculosis diagnosis using an immunosensor based on CdS quantum dots coupled to magnetic beads as labels. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2015, 10, 2580–2593. [CrossRef]

- Januarie, K.C.; Oranzie, M.; Feleni, U.; Iwuoha, E. Quantum dot amplified impedimetric aptasensor for interferon-gamma. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 463, 142825. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhu, M.; Hao, Y.; Yang, P. Potential-resolved electrochemiluminescence for simultaneous determination of triple latent tuberculosis infection markers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 30536–30542. [CrossRef]

- Hu, O.; Li, Z.; Wu, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tong, Y. A multicomponent nucleic acid enzyme-cleavable quantum dot nanobeacon for highly sensitive diagnosis of tuberculosis with the naked eye. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 254–262. [CrossRef]

- Kabwe, K.P.; Nsibande, S.A.; Pilcher, L.A.; Forbes, P.B.C. Development of a mycolic acid-graphene quantum dot probe as a potential tuberculosis biosensor. Luminescence 2022, 37, 1881–1890. [CrossRef]

- Kabwe, K.P.; Nsibande, S.A.; Lemmer, Y.; Pilcher, L.A.; Forbes, P.B.C. Synthesis and characterisation of quantum dots coupled to mycolic acids as a water-soluble fluorescent probe for potential lateral flow detection of antibodies and diagnosis of tuberculosis. Luminescence 2022, 37, 278–289. [CrossRef]

- Zou, F.; Zhou, H.; Tan, T.V.; Kim, J.; Koh, K.; Lee, J. Dual-mode SERS-fluorescence immunoassay using graphene quantum dot labeling on one-dimensional aligned magnetoplasmonic nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 12168–12175. [CrossRef]

- Hu, O.; Li, Z.; He, Q.; Tong, Y.; Tan, Y.; Chen, Z. Fluorescence biosensor for one-step simultaneous detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis multidrug-resistant genes using nanoCoTPyP and double quantum dots. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 7918–7927. [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Jiang, P.; Peng, W.; Meng, Y.; Ying, B.; Chen, P. Nucleic acid and nanomaterial synergistic amplification enables dual targets of ultrasensitive fluorescence quantification to improve the efficacy of clinical tuberculosis diagnosis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 14510–14519. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Qin, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Z.; Ma, H.; Lu, J.; Huang, X.; Shi, D.; Hu, Z. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on H37Rv binding peptides using surface functionalized magnetic microspheres coupled with quantum dots—A Nano detection method for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 77. [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qing, L.; Chen, H.; Lu, J.; Yang, H. [Methodology research and preliminary assessment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis detection by immunomagnetic beads combined with functionalized fluorescent quantum dots]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi (Chin. J. Tuberc. Resp. Dis.) 2013, 36, 100–105 [in Chinese].

- Shojaei, T.R.; Mohd Salleh, M.A.; Tabatabaei, M.; Ekrami, A.; Motallebi, R.; Rahmani-Cherati, T.; Hajalilou, A.; Jorfi, R. Development of sandwich-form biosensor to detect mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in clinical sputum specimens. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 18, 600–608. [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Chen, M.; Tong, Y.; Tan, W.; Chen, Z. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis IS6110 gene fragment by fluorescent biosensor based on FRET between two-dimensional metal-organic framework and quantum dots-labeled DNA probe. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1186, 339090. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Kim, E.B.; Lee, S.W.; Cheon, S.A.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, J.; Lee, M.-K.; Ko, S.; Park, T.J. An easy and sensitive sandwich assay for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ag85B antigen using quantum dots and gold nanorods. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 150–156. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Huang, H.; Hu, J.; Xia, L.; Liu, X.; Qu, R.; Huang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wu, K.; Ma, R.; et al. A novel quantitative urine LAM Antigen strip for point-of-care tuberculosis diagnosis in non-HIV adults. J. Infect. 2024, 88, 194–198. [CrossRef]

- Tufa, L.T.; Oh, S.; Tran, V.T.; Kim, J.; Jeong, K.-J.; Park, T.J.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, J. Electrochemical immunosensor using nanotriplex of graphene quantum dots, Fe3O4, and Ag nanoparticles for tuberculosis. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 290, 369–377. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D.; Sarswat, P.K.; Free, M.L. Quantum dots and carbon dots based fluorescent sensors for TB biomarkers detection. Vacuum 2017, 146, 606–613. [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Cai, S.; Wu, J.; Hu, O.; Liang, L.; Chen, Z. Determination of tuberculosis-related volatile organic biomarker methyl nicotinate in vapor using fluorescent assay based on quantum dots and cobalt-containing porphyrin nanosheets. Microchim. Acta 2022, 189, 108. [CrossRef]

- Gazouli, M.; Liandris, E.; Andreadou, M.; Sechi, L.A.; Masala, S.; Paccagnini, D.; Ikonomopoulos, J. Specific detection of unamplified mycobacterial DNA by use of fluorescent semiconductor quantum dots and magnetic beads. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 2830–2835. [CrossRef]

- Cimaglia, F.; Aliverti, A.; Chiesa, M.; Poltronieri, P.; De Lorenzis, E.; Santino, A.; Sechi, L.A. Quantum dots nanoparticle-based lateral flow assay for rapid detection of mycobacterium species using anti-FprA antibodies. Nanotechnol. Dev. 2012, 2, 5. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zeng, H.; Duan, C.; Hu, Q.; Wu, Q.; Yu, Y.; Yang, X. One-pot synthesis of stable and functional hydrophilic CsPbBr3 perovskite quantum dots for “turn-on” fluorescence detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 3581–3589. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Bakhori, N.; Yusof, N.A.; Abdullah, J.; Wasoh, H.; Ab Rahman, S.K.; Abd Rahman, S.F. Surface enhanced CdSe/ZnS QD/SiNP electrochemical immunosensor for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by combination of CFP10-ESAT6 for better diagnostic specificity. Materials 2019, 13, 149. [CrossRef]

- Gliddon, H.D.; Kaforou, M.; Alikian, M.; Habgood-Coote, D.; Zhou, C.; Oni, T.; Anderson, S.T.; Brent, A.J.; Crampin, A.C.; Eley, B.; et al. Identification of reduced host transcriptomic signatures for tuberculosis disease and digital PCR-based validation and quantification. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 637164. [CrossRef]

- Boyle, D.S.; McNerney, R.; Teng Low, H.; Leader, B.T.; Pérez-Osorio, A.C.; Meyer, J.C.; O’Sullivan, D.M.; Brooks, D.G.; Piepenburg, O.; Forrest, M.S. Rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by recombinase polymerase amplification. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103091. [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Dubey, A.; Singh, P.; Tewerson, S.; Sharma, D. Adenosine deaminase (ADA) level in tubercular pleural effusion. Lung India 2008, 25, 109. [CrossRef]

- DeVito, J.A.; Morris, S. Exploring the structure and function of the mycobacterial KatG protein using trans -dominant mutants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 188–195. [CrossRef]

- Clifford, V.; Tebruegge, M.; Zufferey, C.; Germano, S.; Forbes, B.; Cosentino, L.; Matchett, E.; McBryde, E.; Eisen, D.; Robins-Browne, R.; et al. Cytokine biomarkers for the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection and disease in adults in a low prevalence setting. Tuberculosis 2019, 114, 91–102. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Hao, Y.; Chen, S.; Yang, P. A Quartz crystal microbalance modified with antibody-coated silver nanoparticles acting as mass signal amplifiers for real-time monitoring of three latent tuberculosis infection biomarkers. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 212. [CrossRef]

- Parate, K.; Rangnekar, S.V.; Jing, D.; Mendivelso-Perez, D.L.; Ding, S.; Secor, E.B.; Smith, E.A.; Hostetter, J.M.; Hersam, M.C.; Claussen, J.C. Aerosol-jet-printed graphene immunosensor for label-free cytokine monitoring in serum. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 8592–8603. [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, P.S.; Panagiotidou, P.; Whelan, A.; Gordon, S.V.; Hewinson, R.G.; Williamson, R.A.; Carr, M.D. Conclusive evidence that the major T-cell antigens of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex ESAT-6 and CFP-10 form a tight, 1:1 complex and characterization of the structural properties of ESAT-6, CFP-10, and the ESAT-6·CFP-10 complex. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 21598–21603. [CrossRef]

- Welin, A.; Björnsdottir, H.; Winther, M.; Christenson, K.; Oprea, T.; Karlsson, A.; Forsman, H.; Dahlgren, C.; Bylund, J. CFP-10 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis selectively activates human neutrophils through a pertussis toxin-sensitive chemotactic receptor. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 205–213. [CrossRef]

- Chai, Q.; Wang, X.; Qiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, P.; Lu, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis surface protein recruits ubiquitin to trigger host xenophagy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1973. [CrossRef]

- P, M.; Ahmad, J.; Samal, J.; Sheikh, J.A.; Arora, S.K.; Khubaib, M.; Aggarwal, H.; Kumari, I.; Luthra, K.; Rahman, S.A.; et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis specific protein Rv1509 evokes efficient innate and adaptive immune response indicative of protective Th1 immune signature. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 706081. [CrossRef]

- Lakshmipriya, T.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Tang, T.-H. Biotin-streptavidin competition mediates sensitive detection of biomolecules in enzyme linked immunosorbent assay. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151153. [CrossRef]

- Omar, R.A.; Verma, N.; Arora, P.K. Development of ESAT-6 based immunosensor for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 653853. [CrossRef]

- Diouani, M.F.; Ouerghi, O.; Refai, A.; Belgacem, K.; Tlili, C.; Laouini, D.; Essafi, M. Detection of ESAT-6 by a label free miniature immuno-electrochemical biosensor as a diagnostic tool for tuberculosis. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 74, 465–470. [CrossRef]

- Arora, J.; Kumar, G.; Verma, A.; Bhalla, M.; Sarin, R.; Myneedu, V. Utility of MPT64 antigen detection for rapid confirmation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J. Global Infect. Dis. 2015, 7, 66. [CrossRef]

- Saengdee, P.; Chaisriratanakul, W.; Bunjongpru, W.; Sripumkhai, W.; Srisuwan, A.; Hruanun, C.; Poyai, A.; Phunpae, P.; Pata, S.; Jeamsaksiri, W.; et al. A silicon nitride ISFET based immunosensor for Ag85B detection of tuberculosis. Analyst 2016, 141, 5767–5775. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-N.; Chen, J.-P.; Chen, D.-L. Serodiagnosis efficacy and immunogenicity of the fusion protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis composed of the 10-kilodalton culture filtrate protein, ESAT-6, and the extracellular domain fragment of PPE68. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012, 19, 536–544. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Boshoff, H.I.M.; Harrison, J.R.; Ray, P.C.; Green, S.R.; Wyatt, P.G.; Barry, C.E. PE/PPE proteins mediate nutrient transport across the outer membrane of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 2020, 367, 1147–1151. [CrossRef]

- García, J.; Puentes, A.; Rodríguez, L.; Ocampo, M.; Curtidor, H.; Vera, R.; Lopez, R.; Valbuena, J.; Cortes, J.; Vanegas, M.; et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv2536 protein implicated in specific binding to human cell lines. Protein Sci. 2005, 14, 2236–2245. [CrossRef]

- Shirshikov, F.V.; Bespyatykh, J.A. TB-ISATEST: A diagnostic LAMP assay for differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Rus. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 49, 1279–1292. [CrossRef]

- Jackett, P.S.; Bothamley, G.H.; Batra, H.V.; Mistry, A.; Young, D.B.; Ivanyi, J. Specificity of antibodies to immunodominant mycobacterial antigens in pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1988, 26, 2313–2318. [CrossRef]

- Verbon, A.; Hartskeerl, R.A.; Moreno, C.; Kolk, A.H.J. Characterization of B cell epitopes on the 16K antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clini. Exp. Immunol. 2008, 89, 395–401. [CrossRef]

- Salata, R.A.; Sanson, A.J.; Malhotra, I.J.; Wiker, H.G.; Harboe, M.; Phillips, N.B.; Daniel, T.M. Purification and characterization of the 30,000 dalton native antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and characterization of six monoclonal antibodies reactive with a major epitope of this antigen. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1991, 118, 589–598.

- Andersen, A.B.; Hansen, E.B. Structure and mapping of antigenic domains of protein antigen b, a 38,000-molecular-weight protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 1989, 57, 2481–2488. [CrossRef]

- Attallah, A.M.; Osman, S.; Saad, A.; Omran, M.; Ismail, H.; Ibrahim, G.; Abo-Naglla, A. Application of a circulating antigen detection immunoassay for laboratory diagnosis of extra-pulmonary and pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2005, 356, 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.W.; Gaylord, H.; Brennan, P.J. Structure and antigenicity of the phosphorylated lipopolysaccharide antigens from the leprosy and tubercle bacilli. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 12345–12351.

- Cocito, C.; Vanlinden, F. Preparation and properties of antigen 60 from Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1986, 66, 262–272.

- Hendrickson, R.C.; Douglass, J.F.; Reynolds, L.D.; McNeill, P.D.; Carter, D.; Reed, S.G.; Houghton, R.L. Mass spectrometric identification of Mtb81, a novel serological marker for tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 2354–2361. [CrossRef]

- Arend, S.M.; Ottenhoff, T.H.; Andersen, P.; van Dissel, J.T. Uncommon presentations of tuberculosis: The potential value of a novel diagnostic assay based on the Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2001, 5, 680–686.

- Wilkinson, S.T.; Vanpatten, K.A.; Fernandez, D.R.; Brunhoeber, P.; Garsha, K.E.; Glinsmann-Gibson, B.J.; Grogan, T.M.; Teruya-Feldstein, J.; Rimsza, L.M. Partial plasma cell differentiation as a mechanism of lost major histocompatibility complex class II expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2012, 119, 1459–1467. [CrossRef]

| Assay | Biomaterial analyzed | Time of analysis | Advantages | Disadvantages | Sensitivity, specificity | Ref. | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular diagnostic tests | |||||||

| Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) | Serum, urine, blood, sputum, saliva, lung biopsy samples, BALF, pleural fluid | 4–5 h | High specificity, quickness, and informativeness | High cost, limited availability, low sensitivity for non-respiratory samples; detection of DNA only | Sensitivity: 47% (42–51%) Specificity: 95% (93–97%) CrI: 95% |

[10] | The sensitivity and specificity are averaged results of 9 studies in 709 subjects |

| Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra | Raw sputum or concentrated sediment | 1.5 h | Detection of rpoB gene mutations associated with rifampicin resistance | High cost | Sensitivity: 89% (85–92%) Specificity: 99% (98–99%) CrI: 95% |

[11] | The sensitivity and specificity are averaged result of 22 studies in 8998 subjects, including 2953 confirmed TB cases and 6045 cases without TB |

| Truenat | Raw sputum | 1 h | Use of a portable, chip-based and battery-operated device. Suitability for laboratories with technical equipment | Lower accuracy compared to Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra | Sensitivity: 80% (70.2–88.4%) Specificity: 98% (94.5–99.6%) |

[12] | The sensitivity and specificity have been estimated in tests in 250 subjects |

| LF-LAM | Urine | 0.5 h | High efficiency, ease of use, low cost, simple technology, no special equipment. Detection of TB in patients for whom other diagnostic methods cannot be used (e.g., HIV patients) | Lower sensitivity compared to Xpert MTB/RIF (though higher compared to microscopy methods). Suitability for a limited group of patients only. Impossibility to distinguish M. tb. from other mycobacteria, which requires using other diagnostic methods after the test | Sensitivity: 45% (29–63%) Specificity: 92% (80–97%) CrI: 95% |

[13] | The sensitivity and specificity are averaged results of 5 studies in 2313 subjects, including 35% of TB cases |

| TB-XT HEMA EXPRESS | Blood, serum | 0.5 h | Quickness, relatively low cost | Low sensitivity, suboptimal performance in the case of high TB prevalence | Sensitivity: 31% (3.9–78%) Specificity: 85% так (52–93%) |

[14] | The sensitivity and specificity have been estimated in tests in 1386 subjects, including 290 TB cases |

| TB tests based on T-cells analysis | |||||||

| IGRA, (T-SPOT.TB, QuantiFERON-TB Gold (QFT)) | Blood, serum | up to 2 days | Insensitivity to BCG vaccination or contact with atypical mycobacteria; one-time tests; high efficiency. T-SPOT.TB is less susceptible to immunosuppression than other TB tests and is preferable for the examination of HIV-infected or autoimmunity patients during treatment with immunosuppressants; can be used before starting therapy with biological drugs | Low specificity and sensitivity; high cost; impossibility to distinguish between the active and latent forms of TB and unsuitability as a primary diagnostic test for LTBI or active TB. The bacterium itself is not determined; the result depends on the state of the patient’s immune system |

QFT Sensitivity: 66% (47–81%) Specificity: 87% (68–94%) T-SPOT Sensitivity: 60% (48–72%) Specificity: 86% (65–95%) |

[15] | The sample consisted of 6,525 HIV-positive patients, including 3,467 TB cases, 806 of them with LTBI and 2,661 with active TB |

| Cultural methods | |||||||

| BBL Septi-Chek AFB | Sputum | Up to 23 days | Higher M.tb growth rate compared to methods using an isolated dense medium | Low sensitivity, long time of analysis | Sensitivity: 73% Specificity: 93% |

[16] | The sensitivity and specificity have been estimated in studies on 274 specimens |

| BАСТЕС (with different parameters of MGIT 460, 960) | Sputum | Up to 14 days | Rapid identification of M.tb and its drug sensitivity; accelerated culture testing of all first-line drugs | High cost, justified only for large laboratories. Semi-automatic monitoring of bacterium growth; many labor-intensive operations; use of radioisotopes and the need for disposal of radioactive waste; long time of analysis |

MGIT 960 Sensitivity: 81.5% Specificity: 99.6% MGIT 460 Sensitivity: 85.8% Specificity: 99.9% |

[17] | The sensitivity and specificity have been estimated in studies on ~8,000 clinical specimens per year. The number after MGIT is the number of wells in the plate. |

| BacT/ALERT 3D | Sputum | 24–72 h | Detection of M.tb growth; detection of M.tb and fungi in blood cultures. Full automation; no radioactive waste | Long time, high cost | Sensitivity: 87.80% Specificity: 99.21% |

[18] | The sensitivity and specificity have been estimated in studies on 2659 clinical specimens |

| Skin tests | |||||||

| Tuberculin skin tests, Mantoux tests, and Diaskintest (in vivo) | Skin tests | 72 h | Availability; low cost; ease of use | Low specificity and sensitivity; unsuitability for diagnosing active TB forms; false positive results in those who have been infected with M.tb in the past because their memory T cells still secrete interferon; impossibility to distinguish the active and latent forms of TB | Sensitivity: 59% Specificity: 95% |

[19] | The sensitivity and specificity have been estimated in tests in 643,694 U.S. Navy recruits |

| Tests based on mycobacterium staining | |||||||

| Gabbett's stain, Ziehl–Neelsen stain, modified cold stain (MCS) | Sputum | ~24 h | Simplicity, quickness, ease of use, low cost | Low sensitivity and specificity; suitability for pulmonary tuberculosis only; inaccuracy in children and HIV-infected persons; multistage and complex procedure. Impossibility to distinguish between different mycobacteria |

Gabbett’s stain Sensitivity: 77% Specificity: 98% Ziehl–Neelsen stain Sensitivity: 70% Specificity: 97% MCS Sensitivity: 60% Specificity: 96% |

[20] | The sensitivity and specificity have been estimated in tests in 100 patients |

| Fluorescence microscopy | Sputum | ~24 h | Quickness, ease of use, specificity | High cost, frequent burn-out of expensive mercury vapor lamps, need for continuous power supply, need for a dark room | Sensitivity: 72% Specificity: 81% |

[21] | The sensitivity and specificity have been estimated in tests in 426 patients |

| Other methods | |||||||

| X-ray | Radiographic test | 1 h | Quickness | High cost; low specificity | Sensitivity: 96% Specificity: 46% |

[22] | The sensitivity and specificity are averaged results of 13 studies |

| MALDI-TOF MS | BALF, sputum | 2.5 h | Rapid, reliable, cost-effective method | Method requires sample preprocessing to generate high-quality proteomic profiles, especially for proteins/peptides or other low-abundance analytes in which MS spectra are obscured by more abundant/high-molecular-weight species. This method is not highly specific because of the matrix proteins and noise issues | Sensitivity: 83%; Specificity: 93%; CrI: 95% |

[23] | The sensitivity and specificity have been estimated in tests in 214 patients |

| LC-MS/MS | Urine, blood | 1 h | Proteomic analysis of urine; identification of proteins characteristic of TB with high molecular specificity and sensitivity; simultaneous diagnosis of HIV-1 and TB using a blood sample. Structural identity of individual components | Changes in ionization efficiency in the presence of not only proteins, phospholipids, and salts, abut also reagents and contaminants | Sensitivity: 94% Specificity: 100% |

[24] | The sensitivity and specificity have been estimated in tests in 57 patients |

| No. | Biomaterial analyzed | Biomarker | Capture molecule | Nanosensor | Method of detection | Wavelength, nm (where relevant) | LOD | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blood | TMCC1, GBP6 | Oligonucleotides specific for M.tb mRNA biomarkers | QD655 and QD525 conjugated with the capture molecules | Toehold-mediated strand displacement with fluorescence quenching by FRET | Emission: 525 Emission: 655 Excitation: 480 |

GBP6: 1.6 nM TMCC1: 6.4 nM |

[64] |

| 2 | Blood | IFN-γ | Anti-human IFN-γ antibodies | CdS QDs coupled to magnetic beads conjugated with the capture molecules. Sandwich-type sensor is fabricated on a glassy carbon electrode covered with a well-ordered gold nanoparticle monolayer, which offers a solid support to immobilize the capture molecules | Square wave anodic stripping voltammetry to quantify the metal cadmium, which indirectly reflects the amount of the analyte | N/A | 0.34 pg/mL | [65] |

| 3 | Serum | IFN-γ | IFN-γ aptamer | Gold electrode covered with L-cysteine-SnTeSe QDs functionalized with the capture molecules | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy detection of the change in the electron transfer resistance upon IFN-γ binding | N/A | 0.151 pg/mL | [66] |

| 4 | Serum | IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2 | Antibody pairs for IFN-γ-, TNF-α and IL-2 | Sandwich immunoassay sensor consisting of luminol and carbon and CdS QDs integrated with gold nanoparticles and magnetic beads functionalized with the capture molecules, as well as the same capture molecules separately immobilized on three spatially resolved areas of a patterned indium tin oxide electrode to capture the corresponding triple latent TB biomarkers | Electrochemiluminescence detection | N/A | 1.6 pg/mL | [67] |

| 5 | Sputum | DNA IS1081 | Specific DNA nanobeacon | QD-based nanobeacon fluorescence probes containing QDs and black hole quenchers. After the target DNA hybridizes with the nanobeacon, the nanobeacon is cleaved into two DNA fragments, and the QDs fluoresce upon moving away from the black hole quenchers | Fluorescence detection by naked eye | Excitation: 280 Emission: 330 |

3.3 amol/L (2 copies/μL) |

[68] |

| 6 | N/A | Anti-MA antibodies | MAs | Graphene QDs covalently functionalized with MAs as detection tags for anti-MA antibodies | Fluorescent lateral flow assay | Excitation: 360 Emission: 470 |

N/A | [69] |

| 7 | N/A | Anti-MA antibodies | Mas | CdSe/ZnS QDs covalently functionalized with MAs as detection tags for anti-MA antibodies | Fluorescent lateral flow assay | Excitation: 390 Emission: 474 |

N/A | [70] |

| 8 | Pure CFP-10 solution | CFP-10 | Pair of anti-CFP-10 antibodies (G2 and G3) | Glass slide coated with magnetoplasmonic core/shell nanoparticles (Fe3O4/Au) functionalized with G2. Graphene QDs functionalized with conjugate of gold-binding protein with G3. Upon binding of CFP-10 by a G2–G3 sandwich, immunoassay is formed | Dual metal-enhanced fluorescence and surface-enhanced Raman scattering detection | Excitation: 320 Emission: 436, 516 |

0.0511 pg/mL | [71] |

| 9 | Pure DNA | rpoB531, katG315 | ssDNA specific for target DNA | QD535 and QD648 functionalized with specific ssDNA. When the target DNA is absent, the nanosensor is attached to a quencher. Binding with the target DNA leads to detachment of the nanosensor and recovery of fluorescence | Fluorescence measurement | Excitation: 380 Emission (rpoB531): 535 Emission (katG315): 648 |

rpoB531: 24 pM; katG315: 20 pM |

[72] |

| 10 | Blood | IFN-γ, IP-10 | Aptamers specific for IFN-γ and IP-10 | Cytosine–Ag+–cytosine and thymine-Hg2+–thymine hairpin structures releasing the metal ions upon specific interaction with different biomarker–aptamer complexes. Ag+ and Hg2+ are bound by CdTe and carbon QDs, which are detected by fluorescence | Fluorescence measurement | - | IP-10: 0.3×10-6 pg/mL; IFN-γ: 0.5×10-6 pg/mL |

[73] |

| 11 | Sputum | M.tb cell | M.tb-binding peptide H8, anti-M.tb polyclonal antibodies, and anti-HSP65 monoclonal antibodies | QDs conjugated with H8 or anti-HSP65 antibodies and MMS conjugated with H8 or anti-M.tb polyclonal antibodies. Magnetic separation of the QD–M.tb–MMS complex | Fluorescence microscopy | Excitation: 405 Emission: 610 |

103 CFU/mL | [74] |

| 12 | M.tb suspension and sputum | M.tb cell | M.tb-binding peptide H8 | Magnetic beads and QDs conjugated with H8. Magnetic separation of the QD–M.tb–magnetic bead complex | Fluorescence microscopy | N/A | 103 CFU/mL | [75] |

| 13 | Sputum | ESAT-6 | Oligonucleotides specific for ESAT-6 | FRET-based sandwich biosensor containing CdTe QDs and gold nanoparticles (quencher) conjugated with the capture molecules (obtained by PCR). When the marker id bound, QD fluorescence is quenched via FRET to gold nanoparticles | Fluorescence detection | Excitation: 370 Emission: 400–680 |

10 fg | [76] |

| 14 | Sputum | IS6110 DNA | ssDNA complementary to the IS6110 gene fragment | FRET-based biosensor in which CdTe QDs conjugated with the capture molecule serves as a donor and Cu-TCPP, which is more affine for ssDNA than double-stranded DNA, serves as an acceptor. In the absence of the marker, the QD fluorescence is quenched. Interaction of the ssDNA. Hybridization of the ssDNA with the marker results in fluorescence , whose intensity depends on the marker concentration | Fluorescence detection | Excitation: 365 Emission: 586 |

35 pM | [77] |

| 15 | Urine | Secretory antigen Ag85B | Anti-Ag85B antibodies (GBP-50B14 and SiBP-8B3) | FRET based biosensor in which gold nanorods conjugated with GBP-50B14 serve as acceptors and silica-coated CdTe QDs conjugated with SiBP-8B3 serve as donors. When both tags bind Ag85B, FRET between the QDs and nanorods quenches the QD fluorescence | Fluorescence detection | Excitation: 350 Emission: 630 |

13 pg/mL | [78] |

| 16 | Urine | LAM | Pair of anti-LAM recombinant monoclonal antibodies | Lateral flow test using CdSe/ZnS QDs encapsulated in polymeric bead conjugated with the capture molecules; test strip with the immobilized capture molecules | Portable fluorescence detector | Excitation: 375 Emission: 620 |

50 pg/mL | [79] |

| 17 | Urine | CFP-10 | Pair of anti-CFP-10 antibodies | Glassy carbon electrode modified with graphene quantum dot–coated Fe3O4@Ag nanoparticles and gold nanoparticles conjugated to the capture antibody. Binding of CFP-10 to the electrode results in an immune sandwich, gold nanoparticles conjugated with the detection antibody serving as signal-amplification labels | Differential pulse voltammetry | N/A | 330 pg/mL | [80] |

| 18 | Exhaled air | TB related volatile organic biomarkers | No | Suspension of CdSe or carbon QDs. The biomarker causes changes in the absorbance and fluorescence spectra. | Spectroscopic analysis | Excitation: 360–650 Emission: 300–800 |

N/A | [81] |

| 19 | Exhaled air | MN | Co ion | CoTCPP nanosheets with attached CdTe QDs. The QD fluorescence is quenched in the absence of MN and is recovered upon MN binding to CoTCPP causing QD release | Fluorescence detection | Excitation: 370 Emission: 658 |

0.59 µM | [82] |

| 20 | BALS, feces, paraffin-embedded tissues | IS6110 and IS900 DNA | Mycobacterium-specific oligonucleotides | CdSe QDs conjugated with streptavidin and species-specific probes and magnetic beads conjugated with streptavidin and genus-specific probes. Sandwich hybridization is used to bind the biomarkers and subsequent magnet separation, to concentrate the biomarker | Fluorescence detection | Excitation: 260 Emission: 655 |

12.5 ng | [83] |

| 21 | Pure fprA | fprA | Anti-fprA antibodies | Direct and double antibody sandwich lateral flow tests with CdSe/ZnS QDs conjugated with the capture molecule | Fluorescence detection | Emission: 565 | 12.5 pg/mL | [84] |

| 22 | M.tb strains | M.tb DNA | ssDNA specific for M.tb | FRET-based sensor composed of water-stable CsPbBr3 perovskite QDs conjugated to DNA probe serving as a donor and MoS2 nanosheets serving as acceptor | Fluorescence detection | N/A | 51.9 pM | [85] |

| 23 | Pure antigens | CFP10-ESAT6 | Anti-CFP10–ESAT6 monoclonal antibody | Electrochemical immunosensor consisting of SPCE functionalized with Si nanoparticles and CdSe/ZnS QDs. The target biomarker is adsorbed on the electrode and then captured by the primary antibody, the secondary antibody being labeled with catalase, whose activity is detected electrochemically | Differential pulse voltammetry | N/A | 15 pg/mL | [86] |

| Biomarker | Already detected with QD-based nanosensors | Comment | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host RNA transcript/DNA signatures | |||

| GBP2, GBP5, GBP6, TMCC1 | + | Oligonucleotides (RNA, DNA) | [64,87] |

| PRDM1 | - | PR domain zinc finger protein 1 gene | [87] |

| ARG1 | - | Arginase 1 gene (encoding the arginase enzyme) | [87] |

| IS6110 | + | IS6110 gene | [77] |

| IS1081 | - | IS1081 gene | [88] |

| rpoB531 | + | rpoB531 gene | [72] |

| katG315 | + | katG315gene | [72] |

| Acids and their derivatives | |||

| MN | + | Menthyl nicotinate | [81] |

| MAs | + | Mycolic acids | [69,70] |

| Enzymes | |||

| MNAzymes | + | Multicomponent nucleic acid enzyme | [68] |

| ADA | - | Adenosine deaminase (enzyme of purine metabolism) | [89] |

| KatGs | - | Catalase-peroxidase enzymes (responsible for the activation of the antituberculosis drug isoniazid) | [90] |

| Сytokines | |||

| IL-1ra | Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist | [91] | |

| IL-2 | + | Interleukin-2 | [91,92] |

| IL-10 | + | Interleukin-10 | [91,93] |

| IL-13 | Interleukin-13 | [91] | |

| INF-y | + | Interferon gamma | [65,92,93] |

| TNF-α | + | Tumor necrosis factor alpha | [92] |

| INF-y IP-10 | + | Interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 | [25] |

| MIP-1β | - | Macrophage inflammatory protein | [91] |

| Specific surface proteins | |||

| CFP-10 | + | 10-kDa culture-filtered protein | [86,94,95] |

| Mtb Rv1468c (PE_PGRS29) | - | M.tb surface protein | [96] |

| Rv1509 | - | M.tb-specific protein | [97] |

| ESAT-6 | - | 6-kDa early secreted antigenic target | [94,98,99,100] |

| MPT-64 | - | M.tb protein 64 | [101] |

| Ag85B | + | Secreted protein antigen 85 complex B | [78,102] |

| PPE-68 | - | Proline-proline-glutamic acid | [103,104] |

| Rv2536 | - | Potential membrane protein | [105] |

| Rv2341 | Probable conserved lipoprotein LppQ | [106] | |

| Mycobacterial antigens | |||

| 14-kDa antigen | - | 14-kDa protein antigen | [107] |

| 16-kDa antigen | - | M.tb-specific antigens | [108] |

| 19-kDa antigen | - | 19-kDa lipoprotein | [107] |

| 30-kDa antigen | - | Immunodominant phosphate-binding protein | [109] |

| 38-kDa antigen | - | Immunodominant lipoprotein antigen | [110] |

| 55-kDa antigen | - | M.tb-specific antigens | [111] |

| LAM | - | A glycolipid and a virulence factor associated with M.tb | [112] |

| A60 | - | Tuberculosis antigen | [113] |

| Mtb81 | - | Recombinant protein | [114] |

| ESAT-6 | + | M.tb-specific antigens | [86,115] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).