Submitted:

02 September 2024

Posted:

03 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Laboratory and Clinical Data

2.3. Identifying Genetic Polymorphisms

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Alleles, Genotypes and Clinical Outcomes

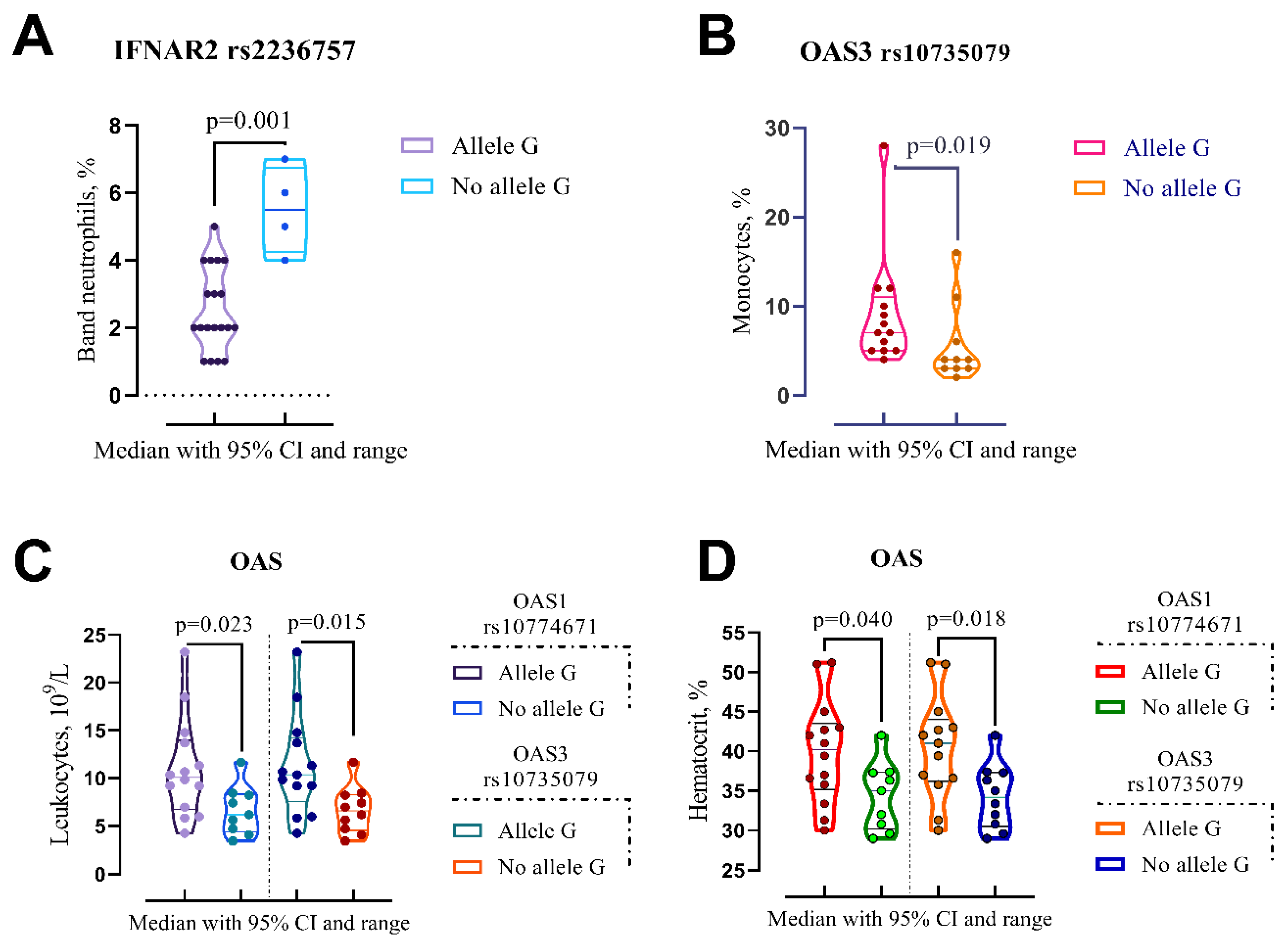

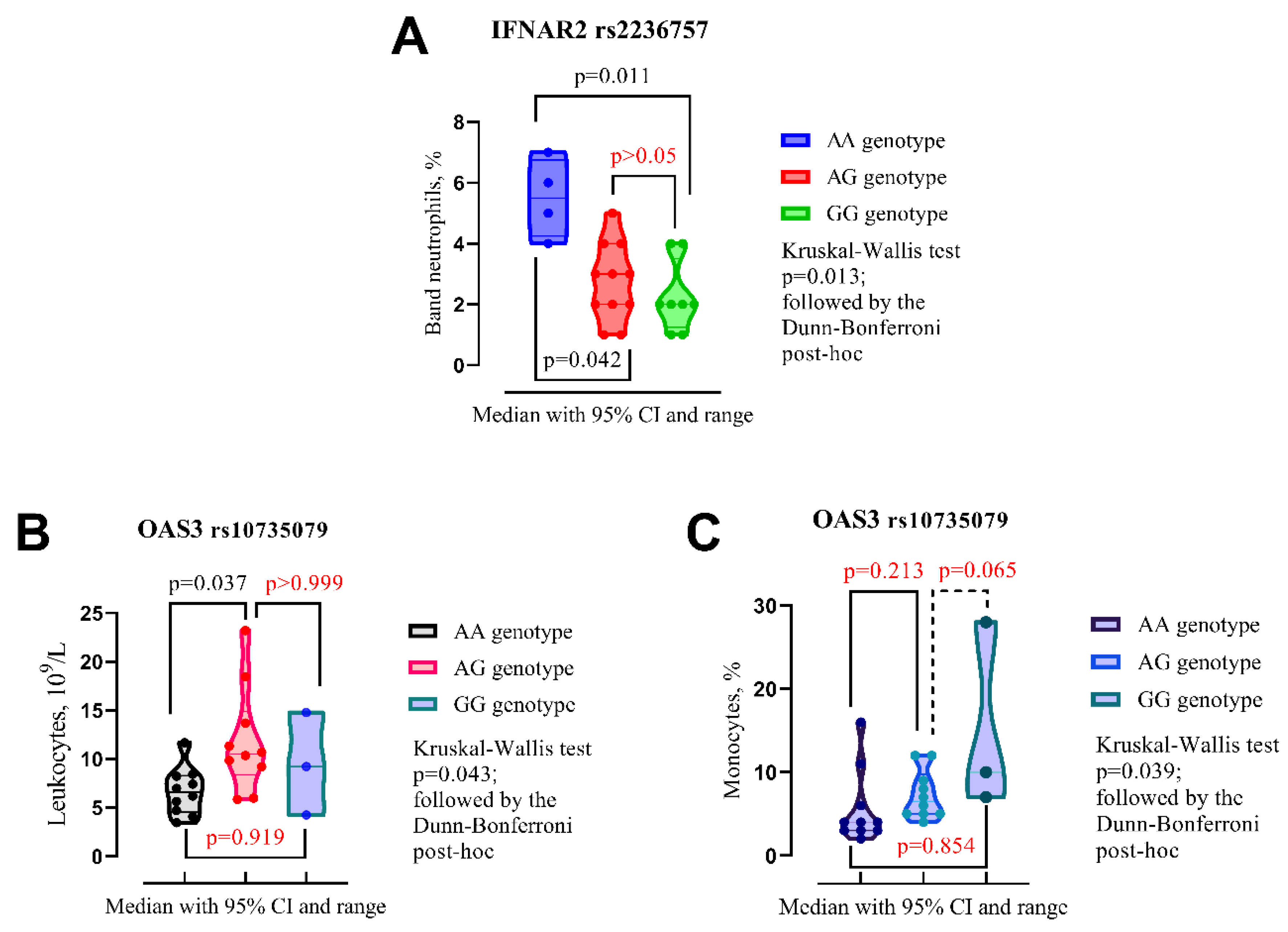

| IFNAR2 rs2236757 | |||

| No Allele G (n=4) | Allele G (n=19) | p-Valuea | |

| Band neutrophils, % (IQR) | 5.5 (4.25–6.75) | 2 (2–4) | p=0.001 |

| OAS3 rs10735079 | |||

| No Allele G (n=10) | Allele G (n=13) | p-Value | |

| Leukocytes, 109/L | 6.59 (4.56–8.29) | 10.4 (7.59–14.2) | p=0.015 |

| Monocytes, % | 4 (3–7.25) | 7 (5–11) | p=0.019 |

| Hematocrit, % | 34.2 (30.5–37.3) | 41 (36.2–44) | p=0.018 |

| OAS1 rs10774671 | |||

| No Allele G (n=9) | Allele G (n=14) | p-Value | |

| Leukocytes, 109/L | 6.19 (4.40–8.34) | 10.1 (6.74–14) | p=0.023 |

| Hematocrit, % | 35 (30.2–37.4) | 40.2 (35.2–43.5) | p=0.040 |

3.2. Alleles, Genotypes and Clinical Outcomes

4. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Najjar-Debbiny, R.; Gronich, N.; Weber, G.; Khoury, J.; Amar, M.; Stein, N.; Goldstein, L.H.; Saliba, W. Effectiveness of Paxlovid in Reducing Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Mortality in High-Risk Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. an Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2023, 76, e342–e349. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.K.H.; Au, I.C.H.; Lau, K.T.K.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Cowling, B.J.; Leung, G.M. Real-World Effectiveness of Early Molnupiravir or Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir in Hospitalised Patients with COVID-19 without Supplemental Oxygen Requirement on Admission during Hong Kong’s Omicron BA.2 Wave: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1681–1693. [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J.; Leister-Tebbe, H.; Gardner, A.; Abreu, P.; Bao, W.; Wisemandle, W.; Baniecki, M.; Hendrick, V.M.; Damle, B.; Simón-Campos, A.; et al. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1397–1408. [CrossRef]

- Yip, T.C.-F.; Lui, G.C.-Y.; Lai, M.S.-M.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Tse, Y.-K.; Ma, B.H.-M.; Hui, E.; Leung, M.K.W.; Chan, H.L.-Y.; Hui, D.S.-C.; et al. Impact of the Use of Oral Antiviral Agents on the Risk of Hospitalization in Community Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients (COVID-19). Clin. Infect. Dis. an Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2023, 76, e26–e33. [CrossRef]

- Buchynskyi, M.; Oksenych, V.; Kamyshna, I.; Kamyshnyi, O. Exploring Paxlovid Efficacy in COVID-19 Patients with MAFLD: Insights from a Single-Center Prospective Cohort Study. Viruses 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Pfizer Inc. Pfizer’s Novel COVID-19 Oral Antiviral Treatment Candidate Reduced Risk of Hospitalization or Death by 89% in Interim Analysis of Phase 2/3 EPIC-HR Study | Pfizer. Pfizer Website 2021.

- Saravolatz, L.D.; Depcinski, S.; Sharma, M. Molnupiravir and Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir: Oral Coronavirus Disease 2019 Antiviral Drugs. Clin. Infect. Dis. an Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2023, 76, 165–171. [CrossRef]

- Lamb, Y.N. Nirmatrelvir Plus Ritonavir: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 585–591. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Q.-S.; Liu, X.-L.; Wang, H.-L.; Liu, W. Adverse Events Associated with Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir: A Pharmacovigilance Analysis Based on FAERS. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Repchuk, Y.; Sydorchuk, L.P.; Sydorchuk, A.R.; Fedonyuk, L.Y.; Kamyshnyi, O.; Korovenkova, O.; Plehutsa, I.M.; Dzhuryak, V.S.; Myshkovskii, Y.M.; Iftoda, O.M.; et al. Linkage of Blood Pressure, Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus with Angiotensinogen Gene (AGT 704T>C/Rs699) Polymorphism in Hypertensive Patients. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2021, 122, 715–720. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.G.; Lin, T.; Wang, P. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Transmission and Pathogenesis. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 1100–1115. [CrossRef]

- Pouladi, N.; Abdolahi, S. Investigating the ACE2 Polymorphisms in COVID-19 Susceptibility: An in Silico Analysis. Mol. Genet. genomic Med. 2021, 9, e1672. [CrossRef]

- Sienko, J.; Marczak, I.; Kotowski, M.; Bogacz, A.; Tejchman, K.; Sienko, M.; Kotfis, K. Association of ACE2 Gene Variants with the Severity of COVID-19 Disease-A Prospective Observational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Pairo-Castineira, E.; Clohisey, S.; Klaric, L.; Bretherick, A.D.; Rawlik, K.; Pasko, D.; Walker, S.; Parkinson, N.; Fourman, M.H.; Russell, C.D.; et al. Genetic Mechanisms of Critical Illness in COVID-19. Nat. 2020 5917848 2020, 591, 92–98. [CrossRef]

- Fricke-Galindo, I.; Martínez-Morales, A.; Chávez-Galán, L.; Ocaña-Guzmán, R.; Buendía-Roldán, I.; Pérez-Rubio, G.; Hernández-Zenteno, R. de J.; Verónica-Aguilar, A.; Alarcón-Dionet, A.; Aguilar-Duran, H.; et al. IFNAR2 Relevance in the Clinical Outcome of Individuals with Severe COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 949413. [CrossRef]

- Dieter, C.; de Almeida Brondani, L.; Lemos, N.E.; Schaeffer, A.F.; Zanotto, C.; Ramos, D.T.; Girardi, E.; Pellenz, F.M.; Camargo, J.L.; Moresco, K.S.; et al. Polymorphisms in ACE1, TMPRSS2, IFIH1, IFNAR2, and TYK2 Genes Are Associated with Worse Clinical Outcomes in COVID-19. Genes (Basel). 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Banday, A.R.; Stanifer, M.L.; Florez-Vargas, O.; Onabajo, O.O.; Papenberg, B.W.; Zahoor, M.A.; Mirabello, L.; Ring, T.J.; Lee, C.-H.; Albert, P.S.; et al. Genetic Regulation of OAS1 Nonsense-Mediated Decay Underlies Association with COVID-19 Hospitalization in Patients of European and African Ancestries. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 1103–1116. [CrossRef]

- Ritonavir-Boosted Nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid) | COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Available online: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/antivirals-including-antibody-products/ritonavir-boosted-nirmatrelvir--paxlovid-/ (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Kamyshnyi, A.; Koval, H.; Kobevko, O.; Buchynskyi, M.; Oksenych, V.; Kainov, D.; Lyubomirskaya, K.; Kamyshna, I.; Potters, G.; Moshynets, O. Therapeutic Effectiveness of Interferon-A2b against COVID-19 with Community-Acquired Pneumonia: The Ukrainian Experience. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6887. [CrossRef]

- Buchynskyi, M.; Kamyshna, I.; Lyubomirskaya, K.; Moshynets, O.; Kobyliak, N.; Oksenych, V.; Kamyshnyi, A. Efficacy of Interferon Alpha for the Treatment of Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1069894. [CrossRef]

- Sodeifian, F.; Nikfarjam, M.; Kian, N.; Mohamed, K.; Rezaei, N. The Role of Type I Interferon in the Treatment of COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 63–81. [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.R.; Allerton, C.M.N.; Anderson, A.S.; Aschenbrenner, L.; Avery, M.; Berritt, S.; Boras, B.; Cardin, R.D.; Carlo, A.; Coffman, K.J.; et al. An Oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitor Clinical Candidate for the Treatment of COVID-19. Science (80-. ). 2021, 374, 1586–1593. [CrossRef]

|

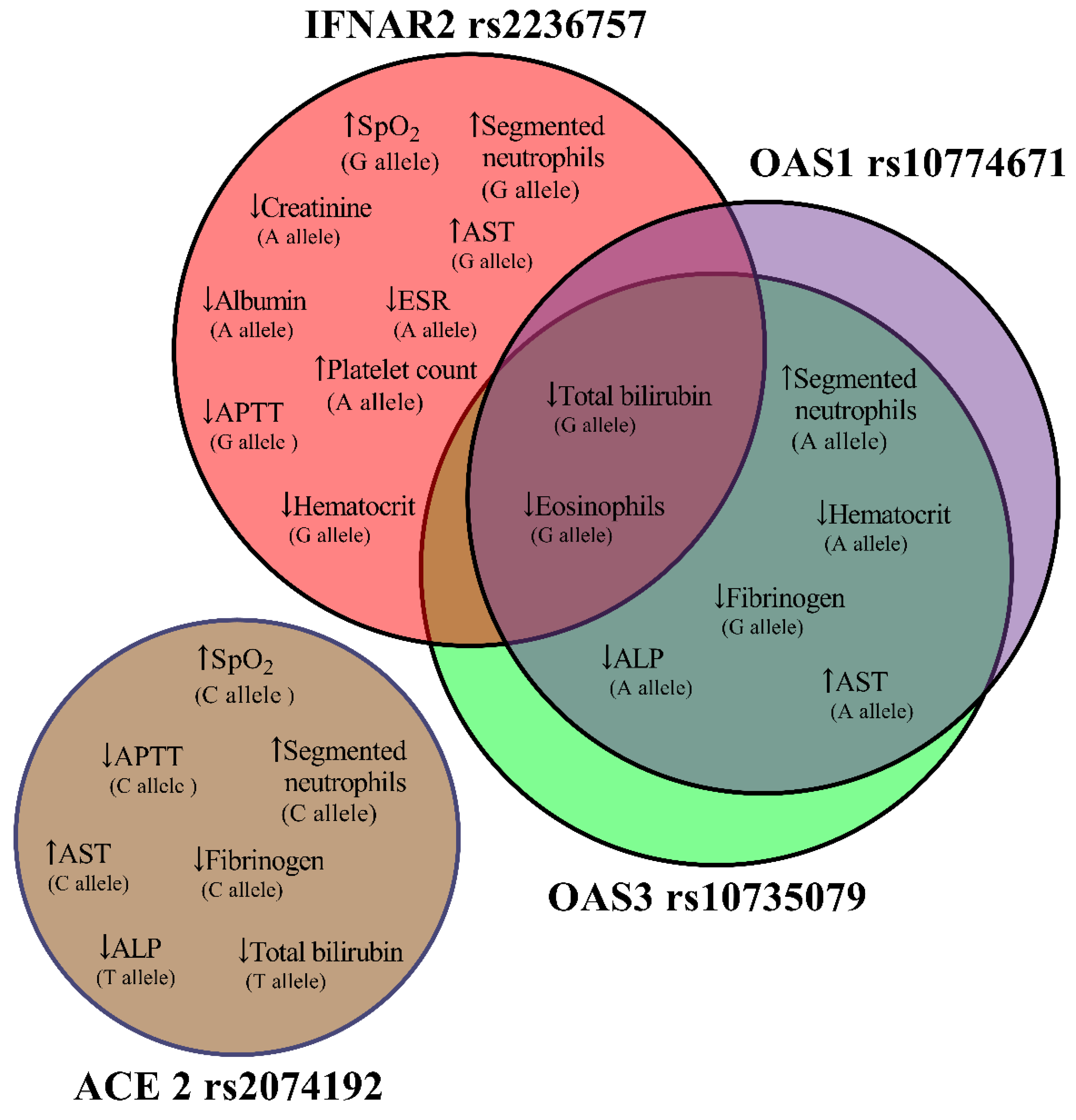

IFNAR2 rs2236757 Allele A (n=15) Allele G (n=19) |

Admission | Discharge | p-Valuea | |

| SpO2, %, median (IQR) | Allele A | 96 (94–98) | 98 (97–98) | p=0.151 |

| Allele G | 96 (92–97) | 98 (97–98) | p=0.019 | |

| Segmented neutrophils, % | Allele A | 55 (46–75) | 66 (48–74) | p=0.059 |

| Allele G | 61 (47–70) | 66 (52–78) | p=0.029 | |

| Eosinophils, % | Allele A | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–1) | p=0.169 |

| Allele G | 1 (1–2) | 1 (0–1) | p=0.048 | |

| ESR, mm/hr | Allele A | 7 (4–11) | 5 (4–6) | p=0.021 |

| Allele G | 5 (4–10) | 4 (4–5) | p=0.371 | |

| Platelet count, 109/L | Allele A | 173 (142–204) | 215 (166–244) | p=0.041 |

| Allele G | 193 (165–231) | 220 (169–262) | p=0.064 | |

| Hematocrit, % | Allele A | 37.2 (34–44) | 36.6 (30.8–41) | p=0.132 |

| Allele G | 40 (34.2–45) | 37 (32–42.7) | p=0.040 | |

| APTT, sec. | Allele A | 33.2 (29.4–35.3) | 32.8 (24.6–35.8) | p=0.177 |

| Allele G | 33.2 (29.4–37) | 29.8 (25–33.7) | p=0.035 | |

| Total bilirubin, mmol/L | Allele A | 13.4 (11.1–19.1) | 11.2 (10.7–14.1) | p=0.128 |

| Allele G | 13.7 (10.8–19.1) | 11.2 (10.5–13.5) | p=0.029 | |

| AST, mmol/L | Allele A | 23.3 (19–27.8) | 25.5 (23.3–67.4) | p=0.112 |

| Allele G | 22.2 (16.6–25.8) | 30.8 (23.3–94.1) | p=0.014 | |

| Creatinine, mmol/L | Allele A | 103 (95–117) | 92 (84–109) | p=0.044 |

| Allele G | 96 (80–117) | 98 (86–109) | p=0.825 | |

| Albumin, g/L | Allele A | 50 (45–57) | 43 (37–51) | p=0.023 |

| Allele G | 50 (45–56) | 46 (42–51) | p=0.159 | |

|

ACE 2 rs2074192 Allele C (n=22) Allele T (n=8) |

Admission | Discharge | p-Valuea | |

| SpO2, %, median (IQR) | Allele C | 96 (93.5–98) | 98 (97–98) | p=0.019 |

| Allele T | 96 (92–97.8) | 97 (97–98) | p=0.102 | |

| Segmented neutrophils, % | Allele C | 57 (46–71.3) | 66 (51.3–75.8) | p=0.016 |

| Allele T | 57 (44.8–65.5) | 68.5 (52.5–73.8) | p=0.078 | |

| APTT, sec. | Allele C | 33.3 (29.7–37.1) | 29.8 (25.5–34.9) | p=0.027 |

| Allele T | 32.8 (29.6–35.1) | 29.8 (25.2–34.5) | p=0.093 | |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | Allele C | 3.99 (3.55–4.94) | 3.33 (2.76–3.99) | p=0.017 |

| Allele T | 3.63 (3.55–4.33) | 3.83 (1.75–3.99) | p=0.611 | |

| Total biligubinum, mmol/L | Allele C | 12.7 (10.8–15.9) | 11.1 (10.6–13.7) | p=0.112 |

| Allele T | 12.9 (10.7–17.8) | 10.8 (10.2–12) | p=0.028 | |

| AST, mmol/L | Allele C | 22.4 (17.2–26.3) | 32.3 (24.2–81.2) | p=0.004 |

| Allele T | 21.9 (14.9–28.1) | 29.1 (21.3–81.1) | p=0.327 | |

| ALP, mmol/L | Allele C | 140 (116–1600 | 122 (95.3–147) | p=0.077 |

| Allele T | 148 (125–165) | 136 (94.3–148) | p=0.025 | |

|

OAS3 rs10735079 Allele A (n=20) Allele G (n=13) |

Admission | Discharge | p-Valuea | |

| Segmented neutrophils, % | Allele A | 61 (47,5–73,8) | 70,5 (53,3–77,3) | p=0.027 |

| Allele G | 55 (46–69,5) | 63 (48,5–75) | p=0.307 | |

| Eosinophils, % | Allele A | 1 (0,25–2) | 1 (0–1) | p=0.134 |

| Allele G | 1 (1–2,5) | 1 (0–1) | p=0.046 | |

| Hematocrit, % | Allele A | 38,6 (34,3–43,5) | 37,2 (31,5–42) | p=0.021 |

| Allele G | 42 (35,3–48,2) | 41 (36,2–44) | p=0.916 | |

| APTT, sec. | Allele A | 34,2 (30–37,2) | 29,8 (26,9–35,2) | p=0.033 |

| Allele G | 33,4 (29,9–37,1) | 29,1 (24,7–34,8) | p=0.066 | |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | Allele A | 3,99 (3,55–)5,05 | 3,63 (2,92–3,99) | p=0.064 |

| Allele G | 3,99 (3,55–4,1) | 3,33 (2,11–3,88) | p=0.031 | |

| Total biligubinum, mmol/L | Allele A | 13,2 (10,7–16,7) | 11,1 (10,6–14,3) | p=0.070 |

| Allele G | 12,9 (11,1–20,6) | 10,7 (10,3–13,2) | p=0.021 | |

| AST, mmol/L | Allele A | 22,7 (19,4–27,3) | 30,1 (24,5–67,4) | p=0.006 |

| Allele G | 22,2 (18,6–26,8) | 26,5 (23,9–96,3) | p=0.116 | |

| ALP, mmol/L | Allele A | 136 (115–152) | 113 (93,8–144) | p=0.025 |

| Allele G | 138 (121–156) | 127 (94–151) | p=0.196 | |

|

OAS1 rs10774671 Allele A (n=20) Allele G (n=14) |

Admission | Discharge | p-Valuea | |

| Segmented neutrophils, % | Allele A | 47,5 (61–73,8) | 70,5 (53,3–77,3) | p=0.027 |

| Allele G | 57 (46–69,3) | 63 (48,8–75) | p=0.183 | |

| Eosinophils, % | Allele A | 1 (0,25–2) | 1 (0–1) | p=0.134 |

| Allele G | 1 (1–2,25) | 1 (0–1) | p=0.032 | |

| Hematocrit, % | Allele A | 38,6 (34,3–43,5) | 37,2 (31,5–42) | p=0.021 |

| Allele G | 41 (35,8–47,7) | 40,2 (35,2–43,5) | p=0.638 | |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | Allele A | 3,99 (3,55–55) | 3,63 (2,92–3,99) | p=0.064 |

| Allele G | 3,99 (3,55–4,26) | 3,33 (2,27–3,99) | p=0.046 | |

| Total biligubinum, mmol/L | Allele A | 13,2 (10,7–16,7) | 11,1 (10,6–14,3) | p=0.170 |

| Allele G | 13,3 (11,2–22) | 10,9 (10,4–13,7) | p=0.014 | |

| AST, mmol/L | Allele A | 22,7 (19,4–27,3) | 30,1 (24,5–67,4) | p=0.006 |

| Allele G | 22,4 (19,5–26,3) | 26 (24,2–95,2) | p=0.096 | |

| ALP, mmol/L | Allele A | 136 (115–152) | 113 (93,8–144) | p=0.025 |

| Allele G | 137 (120–155) | 125 (95–148) | p=0.158 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).