1. Introduction

The effort and pace at which society is reshaping its interaction with existing energy systems are unprecedented in human history. Over recent decades, societal pressure has intensified the push for an energy transition, with the energy sector identified as the primary source of global greenhouse gas emissions. This necessitates a rapid acceleration of mitigation efforts to keep warming above pre-industrial levels below 2.0°C [

1]. Reinforcing this shift, the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 targets affordable and clean energy to improve health, eradicate poverty, spur economic growth, and promote innovation [

2]. Concurrently, SDG 17 aims to enhance global partnerships to effectively achieve these sustainable development goals. It focuses on strengthening partnerships and interactions across a broad complex social system to mobilize knowledge, technology, and financial resources, as well as to foster effective collaborations between public, private, and civil society entities [

3].

These socio-economic interdependencies related to the energy transition became particularly evident during the Russo-Ukrainian War in early 2022. Prior to the conflict, the European Union (EU) depended heavily on Russian gas, which constituted over 40% of its imports by the end of 2021 [

4]. The war led to severe disruptions as the EU imposed sanctions against Russia, compelling numerous companies to comply with international laws and cease operations in Russian territories.

In retaliation, the Kremlin cut off gas supplies, forcing the EU to rapidly diversify its energy sources. This shift caused price fluctuations in the energy and fertilizer markets and led to a temporary increase in coal use, even as the EU accelerated the deployment of renewable energy sources like wind and solar power. Despite these challenges, the future of the EU’s energy transition remains promising, illustrating the complex interdependencies within global energy systems [

2].

As exemplified above, the energy transition phenomenon is highly intricate, involving multiple stakeholders within a complex system that is susceptible to broad landscape forces such as conflicts, demographic trends, political ideologies, social values, and macroeconomic patterns, all of which can reshape its structure [

5]. While traditional case studies, typically involving a limited number of actors, are valuable for advancing theoretical development [

6], we suggest that a more holistic and integrative approach spanning multiple levels of analysis may offer greater benefits for understanding complex social phenomena, since sustainability transitions are long-term, multi-dimensional processes that require broader socio-technical systems transformations [

5]. This systemic view not only benefits scholars aiming to understand the energy transition phenomenon but also provides valuable insights for policymakers who need to comprehend the impacts of new regulations on various actors, and for practitioners seeking enhanced strategies for value creation and capture.

Two strategic frameworks available to address these complex dependencies have gained increasing popularity over the years in sustainable studies. The Business Ecosystem Theory (BET), which draws a parallel with natural ecosystems, has been associated in the strategic management literature with these types of problems where value creation occurs through interaction among multiple actors, often outside their supply chains [

7]. On the other hand, the Social Network Theory (SNT), which derives from the Graph Theory, is concerned with relations between objects [

8], allowing these entities to have attributes (names, qualities, or properties) that are appropriate to study psychological, economic, and social problems [

9].

Researchers frequently utilize Social Network Theory (SNT) to operationalize and analyze ecosystems [

10,

11,

12,

13]. This approach is not surprising, given that the theory has been loosely associated with the concept of networks since its inception, a topic that we will delve into in the next section. Moreover, Schiller et al. [

14] conducted a review of network analysis within the industrial ecosystems and industrial ecology fields and found it as one of the most promising methods used by researchers.

Realizing this trend in many business fields, Shipilov and Gawer [

15] were motivated to undertake the first formal integration of both theories. This integration sought to improve the rigor and depth of ecosystem analysis by leveraging SNT's post-positivist roots, which posit that relationships among actors can be mathematically modeled using graphs. While this first formal attempt at combining different theoretical lenses should be commended, some critical points remain open. For instance, the authors commonly rely heavily on a particular stream of ecosystems that only focuses on nongeneric technical complementarities. As we will further explore in the next chapter, the literature on ecosystems reports different streams that could add more insights when analyzing sustainable transitions and the energy transition phenomena.

Additionally, most of the strategic literature using ecosystems place their unit of analysis on the level of the organization, which generally results in interoganizational networks, i.e., networks comprising the relationship among organizations [

16,

17,

18]. There are several challenges associated with this approach. Firstly, there is a lack of clear theoretical distinction between what constitutes a business ecosystem and an interoganizational network, which creates a classification issue in the business and management literature. Additionally, these networks are typically large and complex, as firms often interact with a plethora of other organizations directly or indirectly. Defining the boundaries of such a system is problematic, and this has been a topic of discussion in the work of Phillips and Ritala [

19]. Furthermore, organizations are increasingly diversifying, including in the energy sector, by expanding their operations across multiple industries [

20]. When analyzing an interoganizational network, it becomes challenging to track the numerous activities conducted by each organization.

To shed light on these points, we posit the following research question: How can integrating the Business Ecosystem and Social Network theories provide an understanding of complex social phenomena, such as the energy transition? To answer this question, we first conducted a literature review on both theories to understand their similarities and divergences. Based on our findings, we attempt to advance an integration between them by suggesting that, instead of focusing on a group of organizations, researchers should perceive ecosystems as a set of functions (i.e., activities, operations, or work). We argue that this interfunctional network perspective offers better theoretical differentiation between the theories, reduces complexity, and increases stability over time, which we support through a case study of Tesla Inc. From this example, we then discuss the emergence of a new construct—Business Ecosystem Footprints (BEF)—which could not only assist managers in mapping their organization's overall presence in the ecosystem but also guide them in making informed decisions about resource allocation and diversification, specifically tailored to support financial objectives as well as sustainability and decarbonization goals.

This research makes four main contributions to the literature: (a) to the energy transition literature, it presents a holistic view of the role of business, innovation, and technology in advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which is of interest to scholars, practitioners, and policymakers; (b) to the ecosystem literature, it advances the integration of Business Ecosystem Theory (BET) and Social Network Theory (SNT), offering new insights for business and management scholars; (c) it shifts from interoganizational networks to interfunctional network analysis, advancing holistic and systemic thinking in the context of innovation and technology for sustainability; (d) it introduces a new strategic construct—the Business Ecosystem Footprint—which has the potential to open new avenues for studies focused on understanding firm positioning, investment, and performance.

The article will follow the following structure:

Section 2 brings the theoretical background of both theories.

Section 3 discusses their similarities and differences, laying the foundation for the logic of interfunctional networks and the Business Ecosystem Footprint construct (

Section 4). Finally,

Section 5 brings the conclusions, study limitations, and suggestions for future research.

2. Theoretical Background

Okhuysen and Bonardi [

21] point that there is impressive potential in combing lenses in search of more affluent and valuable theories in management. However, this approach often comes with clear challenges, especially when integrating theories derived from different ontological and epistemological natures.

Our main objective in this chapter is to advance the understanding of Business Ecosystems by integrating two streams of theory: Business Ecosystem and Social Network theories. However, these are just two of the many management frameworks used to analyze interdependencies among organizations. Recognizing the need for clearer distinctions, Adner [

7] offered a first meticulous analysis of a variety of contrasting approaches to interdependencies in his seminal paper on business ecosystems.

For instance, while value chains [

22] and supply chains [

23] do incorporate the interdependence of multiple stakeholders, Adner [

7] recognized that they are typically modeled as a series of decomposable bilateral relationships. This approach stands in contrast to ecosystem theory, which recognizes the complexity of multiparty interdependencies that interact to create a system that surpasses the sum of its individual parts. Moreover, the linear flow of activities in supply chains, which defines a critical path, may not fully capture the dynamics of certain interactions, such as history, power, or regulation, which are crucial in phenomena such as energy transitions.

Alternatively, Adner [

7] also recognized that platforms [

24] and multisided markets [

25] also provide frameworks to analyze phenomena pertaining to the interaction of multiple stakeholders, with an emphasis on technology and transactions, respectively. Platforms often centralize control and set governance terms that manage rules, openness, access, and incentives. While this view has gained popularity in analyzing digital platforms [

26], not all interdependencies conform to this model, as will be demonstrated in the Tesla case discussed later (section 4). It is worth mentioning that sometimes platforms are seen as a theoretical stream within ecosystems [

15,

27,

28], a topic that will be explored further in this work. However, their primary concern is managing interfaces and complementarities, in contrast to ecosystems that manage the entire structure of interdependence. As mentioned earlier, in some complex social phenomena, more than just technical aspects are necessary to understand transitions, especially those related to sustainability [

5].

Conversely, ecosystems also differ from business models and open innovation. On one hand, while business models [

29,

30] detail a single firm's strategy for value creation, ecosystems involve a network of firms whose collaborative strategies are crucial, leading to the notion of an ecosystem strategy [

7]. On the other hand, open innovation [

31,

32] focuses on the origins of innovation and the flexible management of innovation processes across firms, not addressing the multilateral coordination among actors, a key element in ecosystems. Nonetheless, Baldwin et al. [

33] have suggested in their paper that focuses on the ecosystem lens on innovation studies that "there is an opportunity to study the nexus of open innovation, business models, and ecosystems, given the common focus on value creation and capture across organizational boundaries" [

33] (p. 8).

Finally, Adner [

7] also discusses networks and alliances [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39] which prioritize connectivity patterns either among individuals (social networks) or firms (alliance networks). While these networks facilitate information flow, differently from ecosystems, they do not inherently convey strategic purpose. Although we agree with such analysis, it lacks a substantial depth necessary to advance a possible integration between SNA and BET.

Therefore, we start this section by describing each theory in more detail before exploring their integration in subsequent chapters. The papers cited are not intended to be an exhaustive list but rather to introduce seminal works that have shaped the most prominent ideas in each field. This foundation will lead into the next chapter, where we will discuss how the two theories converge and diverge and explore potential integrations between them.

2.1. Social Network Theory

Social Network Theory (SNT) is derived from Graph Theory, a branch of mathematics dedicated to studying the relationship between objects [

8]. The premise of this theory is that entities (individuals, groups, or organizations) are embedded in a thick web of relationships and influences [

9].

Jacob Moreno [

40] is often considered the father of social network analysis. Departing from the currently established worldview of his time that intrinsic factors mainly drove behavior and psychological issues, he believed that the interaction among people created structures that could explain certain phenomena. He devised sociograms, a visual representation of social relationships to understand the structures of groups, and sociometry, which are quantitative methods for measuring social relationships. These techniques are still widely used in sociology, psychology, anthropology, and political science.

Three decades later, Milgram [

41] conducted the influential small-world experiment to explore the average path length in social networks, leading to a seminal publication in the Psychology Today. Participants were tasked with sending letters to a target person using only the name and location. This experiment introduced the concept of "six degrees of separation," empirically demonstrating society's higher level of connectivity than anticipated. Milgram's work laid the groundwork for studying diffusion in networks, encompassing ideas, information, and influence. It has served as inspiration for contemporary research, including investigations into the structure of digital platforms like Facebook [

42]. Subsequently, Watts and Strogatz [

43] established the mathematical framework for small-world networks in the journal Nature, characterized by high clustering and short average path lengths. Such networks frequently manifest in both natural and artificial systems.

In 1973, Mark Granovetter published a pioneering work in the American Journal of Sociology that theorized the nature of ties among actors. By studying the process of job searching and networking, he realized that individuals are more likely to find new job opportunities through acquaintances (weak ties) than close relationships, such as family and friends [

44]. This suggests that weak ties are more likely to serve as a breach outside immediate social circles, representing sources of new opportunities and information.

Research on interoganizational networks can also be traced to Granovetter [

15]. In his 1985 seminal paper on social embeddedness also published in American Journal of Sociology, the author advocated that economic actions are not isolated but embedded within social networks and relationships [

45]. In opposition to the prevalent worldview then, individuals and firms did not make decisions based solely on market efficiency and self-interest but rather on their relationships and connections. Those provide actors strategic access to resources and information, besides shaping their perceptions of opportunities and risks.

Another work that helped shape the current understanding of networks in business and management came from Ronald Burt [

46] in 1992. The author explored the concept of structural holes in social networks and how they relate to social capital and competition. It was posited that actors who bridge other actors not connected among themselves (structural holes) have better access to information, opportunities, and resources (social capital) coming from the entire structure. This, in turn, promotes more significant success in problem-solving and innovation that materializes in competitive advantage. This notion has been extrapolated from individuals to organizations and is still a core idea in network and ecosystem theories.

Following these ideas, the research on interoganizational networks flourished over the decades in business and management to explain why organizations behave the way they do. A plethora of phenomena was analyzed from network structure and formation [

34,

37], innovation systems [

47], organizational performance [

35], strategic alliances [

36,

38,

39], financial markets and mergers and acquisitions [

49], among others.

2.2. Business Ecosystem Theory

The Business Ecosystem Theory (BET) is relatively new compared to the SNT. The concept of ecosystems in a business context can be traced back to James F. Moore, as discussed by Adner [

7] and Shipilov and Gawer [2015]. In 1993, drawing a parallel with biology, Moore [

50] argued in a Harvard Business Review paper that companies should not be viewed in isolation but as members of a business ecosystem that spans various industries. Throughout his arguments, terms related to centrality are frequently used (e.g., central ecological contributor, central position, marginal business ecosystems), although the SNT is not formally invoked in the text.

However, term ecosystem was used in the industrial context even before it entered business literature. In a 1989 Scientific American paper, Frosch and Gallopoulos [

51] proposed that an industrial ecosystem would be analogous to a natural/biological ecosystem, advocating for manufacturing processes to become more integrated. This integration would optimize energy and material flows, minimize waste, and introduce a certain circularity where the effluent of one process would feed the next. This idea quickly gained traction and was further explored in the discipline of Industrial Ecology, which seeks to connect the industrial ecosystem with the natural biosphere, as noted by Lowe and Evans [

52] and Côté & Hall [

53] in publications to the Journal of Cleaner Production.

Over a decade later, in 2004, Iansiti and Levien [

54] introduced the notion of "Strategy as Ecology" in a Harvard Business Review article. They define business ecosystems as loosely connected networks comprising suppliers, distributors, outsourcing firms, markers of related products or services, technology providers, customers, competitors, and regulators. The fundamental premise of their work is that managers should be looking at ways of coordinating the interdependence of independent actors that often reside outside their supply chains. Again, the notion of networks is informally brought upon, but no integration was proposed.

Three years later, the organizational theorist David Teece [

55] published an article in the Strategic Management Journal about the capabilities necessary for companies to achieve higher performance in an innovation-driven economy. He argued that top-performance enterprises not only adapt to their business ecosystem but shape them with their capabilities. He defined those ecosystems as constructs that surpass the notion of an industry, encompassing a community of organizations, institutions, and individuals that impact the enterprise and the enterprise’s customers and suppliers, including complementor, regulators, judiciary, educational and research institutions, and standard-setting bodies.

From there, the term ecosystem started to gain increasing visibility among scholars and practitioners, entering the lexicon of modern-day business. However, although there is a consensus on the symbiotic nature arising from the interdependency among actors, there is still a multiplicity of interpretations about what an ecosystem is, pointing out that it is still in the process of evolution [

56].

Observing the nature of these multiple perspectives and confusion around what constitutes or is not a business ecosystem, Ron Adner [

7] published a paper in 2017 in the Journal of Management identifying two major types of ecosystem perspectives: ecosystem-as-affiliation and ecosystem-as-structure. The former view is an actor-centric one, starting with a single organization and emphasizing “the breakdown of traditional industry boundaries, the rise of interdependence, and the potential for symbiotic relationships in productive ecosystems" [

7] (p. 41). The position of actors within the ecosystem is determined by their existing links, with organizations possessing numerous high-quality links occupying the center and those with few or low-quality links residing on the fringe of the ecosystem.

This interpretation is often observed in academia and business as they evoke ecosystems around companies or organizations, e.g., Amazon’s and Toyota’s ecosystems. This view aligns somewhat with Moore’s traditional interpretation, which mentioned Apple’s and Walmart’s ecosystems as exemplifications. According to Adner, standard metrics to this construct are the number of partners (degree), centrality, and network density, bringing forth formal concepts from SNT. Although the author borrows metrics from SNT, the paper does not discuss or formalize the integration between the two theoretical streams.

On the other hand, the Ecosystem-as-Structure concept is defined as the "alignment structure of the multilateral set of partners that need to interact for a focal value proposition to materialize" [

7] (p. 41). The strategic approach to this construct involves managing all potential links in the system, including indirect ones that relate to activities and actors with whom a focal firm may not interact. In this perspective, the actor’s positions do not derive from existing links. Instead, it depends on the flow of activities derived from alignment requirements. In other words, this approach involves the reverse flow of the former perspective, as the process begins with defining value creation, which then leads to the diligent selection of actors and links required for its realization.

Around the same time, other scholars attempted to clarify what constitutes an ecosystem. By reviewing the extant literature on top management journals, Jacobides et al. [

28] identified three significant ecosystems perspectives in use among practitioners and scholars: ecosystems centered around a firm and its environment (business ecosystem), around a particular innovation or value proposition (innovation ecosystem), or around how actors organize in a platform (platform ecosystems).

While Adner positioned an ecosystem as a construct, Jacobides et al. [

28] started advancing it as a theory. Since the primary goal of a theory is to answer questions of how, when, and why, moving away from mere descriptions [

57], the authors conducted their research to extend beyond what an ecosystem is and how players align. Their paper focused on why and when actors align, offering a set of predictions on when the ecosystem logic emerge and dominate.

According to the authors, “an ecosystem is a set of actors with varying degrees of multilateral, nongeneric complementarities that are not fully hierarchically controlled” [

28] (p.2264). Their central assumption is that modularity, i.e., the separability along a production and consumption chain, creates the conditions for ecosystem emergence. In turn, it gives birth to different types of complementarities, a well-known construct from the field of economics that denoted items, steps, or activities that add value to one another when used together. However, in the case of ecosystems, these complementarities do not necessarily need to be bound by contracts or belong to the same industry.

The cornerstone of this theoretical stream is technical modularity, which captures technological complementarities among actors. This is appropriate for studying digital platforms, which often revolves around the tension between flexibility and variety versus the need for standards and governance [

58]. The definition of standards, API (Application Interface Programming), co-development, compatibility, and openness are current themes in this type of discussion.

However, while technical complementarities are widely acknowledged among scholars studying innovation, not all agree that it should be ubiquitous when applying the Business Ecosystem theory. For instance, Tsujimoto et al. [

27], in their systematic literature review published in the journal Technological Forecast and Social Change, examined how the term "ecosystems" is used across 90 articles from Q1 journals (top 25% of academic journals in their subject categories) in the fields of "management of technology and innovation" and "strategy and management." They identified four theoretical streams related to ecosystems: industrial ecology, business ecosystems, platforms, and multi-actor networks, and proposed an integrated model that combines different interpretations.

The first stream, which is based on industrial ecosystem theory, emphasizes natural sciences and engineering disciplines, focusing on optimizing material, energy, and monetary balances. Of the 26 articles in this stream, 25 were published in the Journal of Cleaner Production, representing approximately 28% of all articles reviewed by the authors.

In contrast, the business ecosystem stream primarily features business contexts with a focus on value creation and capture, analyzing the dynamics and patterns of interoganizational interactions, mainly involving money flows, complementary goods/services, contracts, and power.

The platform perspective is grounded in the two-sided market concept of microeconomics and is predominantly linked to the IT sector, focusing on technical modularities. This perspective often addresses platform growth and decline by analyzing its structure, hierarchy, openness, and evolvability.

The authors built upon the broadest stream, which they called the Multi-Actor Network Perspective (MNP), to propose that an ecosystem is a historically self-organized or managerially designed multilayer social network that provides a product/service consisting of actors that have different attributes, decision principles, and beliefs. This definition expands the analysis boundary from a single firm and its direct supply-chain relationships to include many actors: entrepreneurs, investors, innovators, users/user communities, policymakers, and consortiums. It also expands on the possible relationships among these actors, including power, regulation, historical relationship, money, contract, knowledge, material, and energy. Therefore, there can be multiple and simultaneous links among actors, surpassing the notion of technical complementarities.

Given that an ecosystem is a conceptual abstraction of a phenomenon that cannot be directly observed [

58], it is expected that it can take multiple forms to adapt to the necessity of each inquiry.

As an illustration, we can cite two papers using the BET that focus on using photovoltaic (PV) technology in the energy transition context. Hannah and Eisenhardt [

59] conducted a longitudinal case study on the U.S. residential solar industry between 2007 and 2014 to explore how firms navigate nascent ecosystems over time. The research published in the Strategic Management Journal focused on technical interdependencies, building upon the previous work of Jacobides et al. [

28].

In contrast, Martelli et al. [

60] published an article in Futures that outlined future scenarios for the Brazilian electricity sector, with photovoltaics (PV) as a major driving force. The authors mapped the Brazilian Electricity Ecosystem using a broader definition of actors and links from the MNP proposed by Tsujimoto et al. [

27]. This allowed the inclusion of actors such as regulators and investors that otherwise would have probably been left out of the ecosystem if only technical complementarities were deployed.

In both cases, the ecosystem logic brought value because change and transition occurred in a business setting. One can expect that the more the theory is applied to different contexts, the more plastic it becomes to cope with new phenomena. So far, Autio and Thomas [

58] have identified seven types of ecosystems (Business, Platform, Innovation, Industrial, Urban, Entrepreneurial, and Knowledge), and perhaps more will be available to the overall academic community in the future.

4. The Logic of Interfunctional Ecosystems: The Tesla Case

In this section, we present the Tesla case as an example of our proposition that the combined utilization of BET and SNT can enhance our ability to understand the complex phenomenon of energy transition and sustainability.

In 2022, the ISSB (International Sustainability Standards Board), a standard-setting body under the IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards), has defined sustainability as “the ability for a company to sustainably maintain resources and relationships with and manage its dependencies and impacts within its whole business ecosystem over the short, medium and long term” [

63]. So, for an actor engaging in sustainable practices, the first act is to understand the business ecosystem it is part of, so it can formulate appropriate strategies. However, as previously discussed, there are different interpretations of what constitutes an ecosystem [

7,

27,

28,

58,

62]. Moreover, companies are becoming increasingly diversified and commonly part of multiple industries [

20].

Let’s analyze the Tesla case. By the end of 2022, the company posted a view of its ecosystem on Twitter that was previously presented in its impact report [

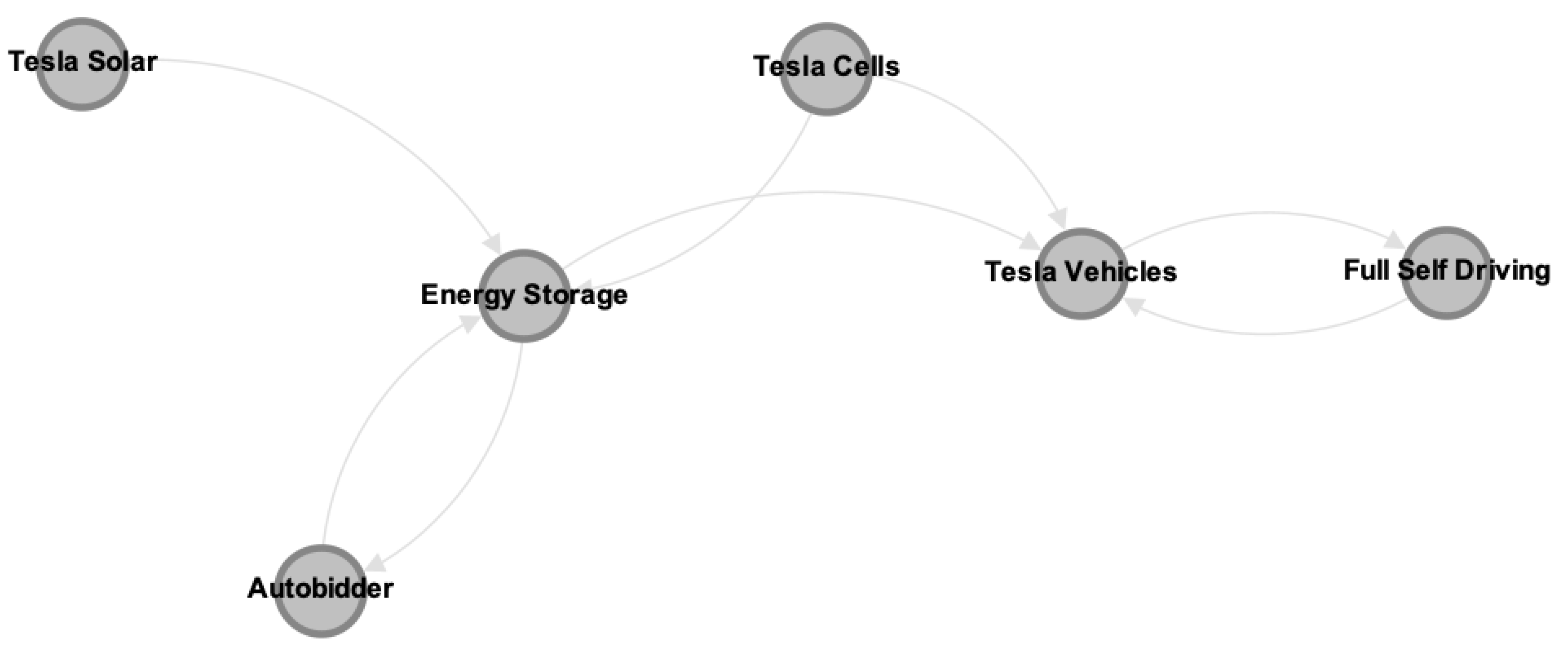

64]. As observed in

Figure 1, it constitutes six different solutions offered by the company (solar panels, energy storage, Tesla cells, Tesla cars, Autobidder, and FSD - Full Self Driving) that could be connected among themselves to offer end customers additional value.

Potential clients could use Tesla Solar Roof to charge their Powerwalls. In turn, this energy can be used to charge Tesla cars or to promote monetization by dispatching it to the grid by the autonomous real-time trading and control platform known as the Autobidder. In critical times, when the price of electricity is high due to the system’s unbalance (high market demand or technical issues), the energy stored in Tesla cars could be returned to the Powewalls to be again monetized by dispatching it to the grid. Finally, Tesla cars could be further enhanced by the use of self-driving technology, which is highly dependent on software and special hardware such as cameras, radars, and/or LiDAR1.

Not surprisingly, this ecosystem is represented as a graph with directed links among its components. It is not merely a network because it implicitly brings some of the ecosystem dimensions presented in

Table 1, such as: (a) a clear value proposition, which is to accelerate the energy transition and the electrification of mobility services, (b) a system-level output, that is represented in the form of energy and mobility products and services, (c) a cross-industry approach, as it touches many traditional industries (mobility, energy, financial services, and technology), (d) a non-decomposability logic since many technologies need to converge simultaneously for the value proposition to materialize.

Except for the Sun in the graph, this interpretation aligns with Jacobides et al. [

28], as it explored their technical interdependencies. However, instead of placing the unit of analysis upon organizations, the prevalent view on the management literature [

15], this graph aims to exemplify how the connected solutions provided by Tesla could be integrated into one another.

There are other ways one could represent Tesla’s ecosystem. Despite being relatively vertically integrated, it still interacts with other companies to deliver its value proposition.

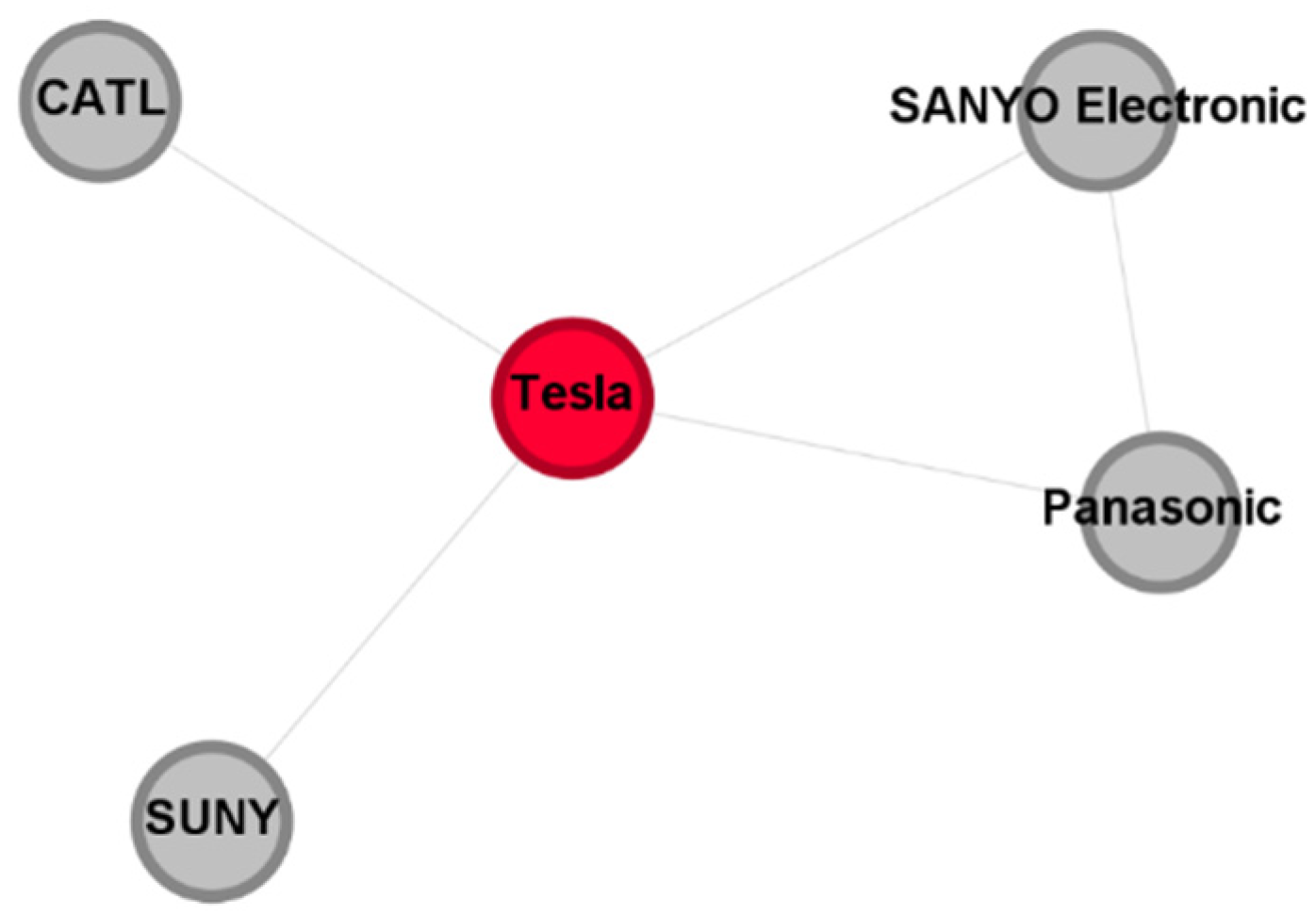

For instance, from the firm’s 10-K submitted to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for the fiscal year of 2022, there are four organizations that Tesla needs to coordinate with for delivering lithium batteries and other energy storage components, critical resources for the materialization of the firm’s operation: Panasonic, SANYO – a subsidiary of Panasonic, CATL – Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited, and SUNY – State University of New York [

65]. Other non-disclosed organizations probably interact with Tesla for the same objective. One could search for other firms that must coordinate to realize the nongeneric complementarities on other sources, such as 10-Qs, technical manuals, and patents.

For the purpose of illustration, a business ecosystem interpretation based on technical complementarities can be employed to map Tesla's interoganizational network using solely the 2022 10-K, with a focus on realizing a critical solution of its value proposition, specifically energy storage and car battery cells. An undirected graph, as shown in

Figure 2, represents this simplified model

2.

Again, this is more than a simple social network because it does possess the same characteristics as the example before (value proposition, system-level outcome, cross-industry approach, and non-decomposability logic), making this model one possible representation of Tesla’s ecosystem. The first striking characteristic of this model is that it puts Tesla at the center of this system, justifiably so because it is built using a self-reporting document from the company.

Adner [

66] call these types of ecosystems ego-systems. Their structure resembles ego networks, graphs formed by a given central actor (ego) and other actors to whom it might be connected. He argues that the presumption of centrality is detrimental since the ecosystem strategy is an alignment strategy. Hence, one needs to extend thinking to include activities and actors over which the focal organization may have no control [

7].

Namely, customers play a vital role in this ecosystem. If they do not adhere to decentralized self-production through solar panels, there will be no purpose for the Autobidder, and they will be reliant on other energy sources, such as coal and oil. That, in turn, is against Tesla’s goal to accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy [

65].

Another striking example is related to autonomous vehicles (AVs). Full self-driving car readiness does not rely solely on technological issues. Legal frameworks are still under development worldwide to determine questions such as liability (i.e., who is responsible when AVs break laws or are involved in accidents), cybersecurity, and privacy [

67]. In turn, that impacts other organizations, such as insurance and software development companies.

These examples illustrate two classes of links. The first are those connections that could be directly established with Tesla, such as consumers and regulators. However, different from the previous perspectives, more than technical complementarities are relevant when drawing these relationships. Any flow or transfer of activities (material, information, influence, and funds) is relevant in this scenario. Therefore, the network would include not only the relationship with suppliers and partners (including battery-manufacturing companies) but also customers, competitors, investors, regulators, and research institutes, among many others.

In network terms, this gives rise to an ecosystem-as-affiliation [

7], a directed ego network that converses well with the initial interpretation of what an ecosystem is [

50]. In this interpretation, since centrality is still presumed, any self-reporting document would be suited to chart an ecosystem, from financial reports to business contracts.

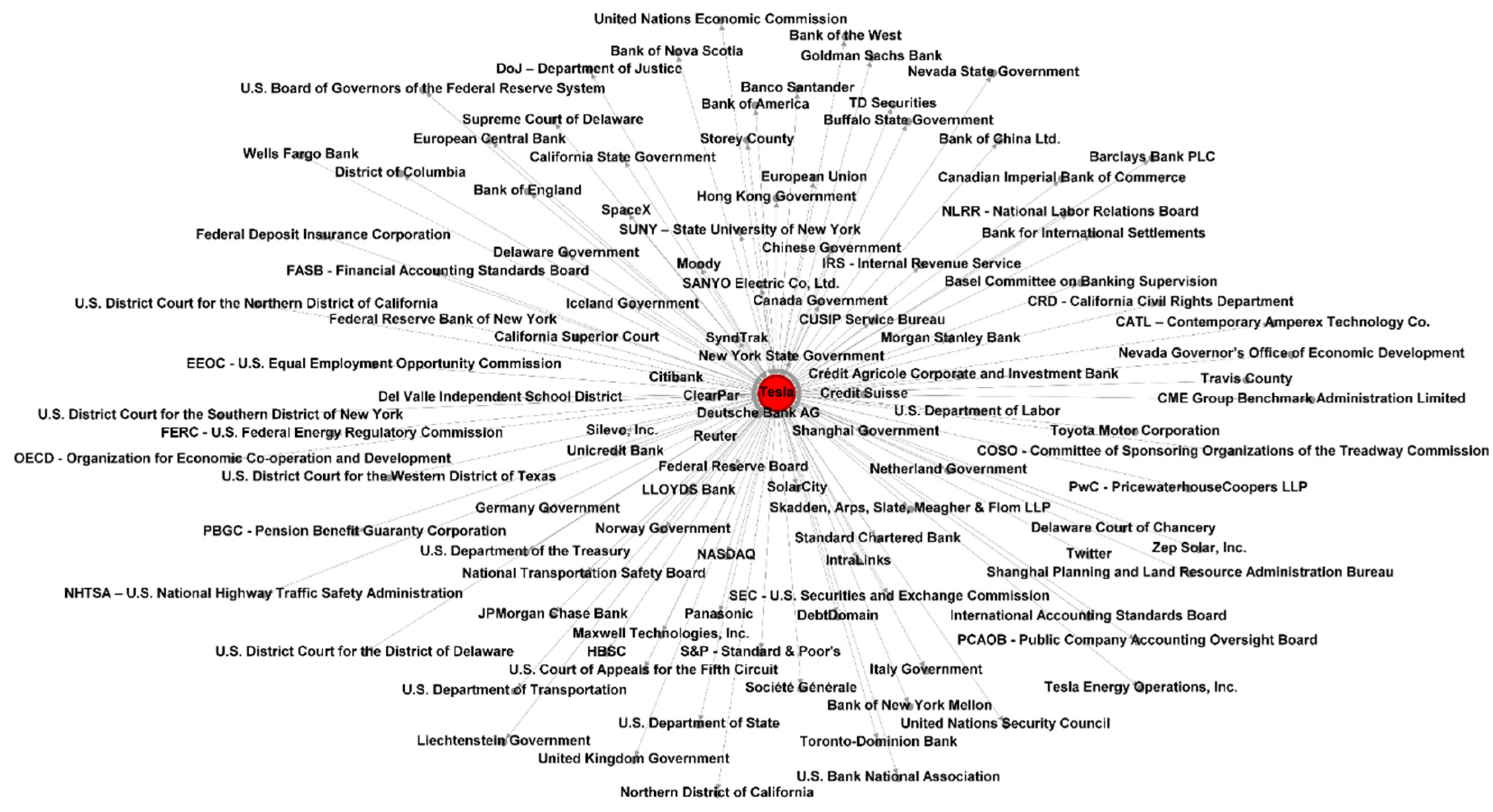

The effort required in this process is significantly higher than before because one needs to map many other types of links besides technical complementarities. Additionally, depending on the length of each source and how many are used, this can be a dull task prone to human errors. For example, the mentioned 10-K has over 250 pages containing many organizations.

One approach is to automate this task using Name Entity Recognition (NER), which uses pre-trained Natural Language Processing (NLP) models to identify and extract entity names, such as person, location, and organizations, from the text. Utilizing the automated text analysis algorithm of the 10-K, we successfully identified 109 organizations (in addition to Tesla) that were used to construct a simplified representation of Tesla's network, as illustrated in

Figure 3. It is important to note that, within this framework, networks are depicted as directed graphs, where the links represent the flow of activities.

We specifically focused on first-degree links, which encompass connections directly associated with Tesla. Therefore, the relationship between SANYO and Panasonic, despite SANYO being a subsidiary of Panasonic, does not hold relevance in this analysis. Similar considerations apply to other organizations, such as the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, which is a part of the U.S. Department of Transportation.

In addition to the assumption of centrality, another criticism of this perspective is that it takes the central firm at face value, concealing multiple functions an organization may have. In

Figure 3, it is unclear that besides an EV manufacturer company, Tesla is a solar energy, battery component company, electrical utility, and tech company. Those are implicit in the graph, but the observer's previous knowledge about the company is required to make those deductions.

The second class of links would be those not directly managed by Tesla but that could influence its value proposition, such as electrical utility companies, oil & gas companies, insurers, mining companies, etc. This type of interpretation gives rise to what Adner [

7] calls ecosystem-as-structure, whole networks that include high-order tier links (e.g., relationships that are not related to a focal firm). This opens space for executives to seek the alignment of structure to players even outside of their direct realm of control, which is essential for the prosperity of the entire ecosystem and its constituents. However, this type of interpretation also creates high complexity since it is hard to determine when an ecosystem starts or ends if one needs to consider all the links outside the realm of a central organization.

Adner [

7] offers the first idea for managing this problem. Instead of using conventional interoganizational networks, the author grouped companies by their activities since multiple actors

3 may undertake a single activity (and conversely, a single actor may undertake multiple activities). Then, actors and nodes are not in an n:n ratio. For instance, if we were to revisit

Figure 3, we could, for example, group all the banks and financial institutions into a single category before establishing the necessary links required to realize the ecosystem's value proposition. This process is inherently subjective, as it requires prior knowledge and judgment about what is the ecosystem’s value proposition, which may not be consciously understood or agreed upon by all participants.

For Jacobides et al. [

28], the actors that need to be included are those that offer nongeneric complementarities. In other words, only those links that require some form of coordination are depicted in an ecosystem. For instance, a critical resource of most restaurants is electricity.

However, most of the time, restaurant owners do not require to coordinate with the regional electric utility companies to deliver their value proposition to their customers. Then, utility companies would not appear in these ecosystems. On the other hand, when analyzing the energy ecosystem, utility companies are required to coordinate among themselves and many other actors to deliver the value proposition of energy transition. In that case, they must appear in such ecosystems.

Tsujimoto et al. [

27] argued that the boundaries of an ecosystem could be set by the consumers' product/service system evaluation range, but often, consumers are oblivious to important interdependencies. For example, most people are aware to some degree that society needs to transition to cleaner energy sources. However, most are unaware of the interaction among actors required for this herculean task.

Since these perspectives are not mutually exclusive, it is possible to build on top of one another as an attempt to propose broader inclusion and exclusion criteria for a generic ecosystem. Then, an ecosystem should include not just immediate links to a focal firm but also higher-order links. Actors and nodes should not necessarily be in an n:n ratio, as multiple actors may undertake a single activity, and a single firm may take multiple activities. Additionally, the actors that need to be included are those that require some form of coordination. Finally, while the value proposition perceived by the client should serve as the ultimate guide for the analysis of the coordination, the subjectivity in setting the boundaries of the ecosystem could be managed by using multiple trusted data sources to determine these limits, from academic papers, patents, technical manuals, in-depth interviews, etc.

Nevertheless, some points would still require attention. First, as previously mentioned, the ecosystem-as-structure only considers links that are flow or transfer of activities (material, information, influence, and funds).

Not only is energy not explicitly mentioned, which is quite important for our research phenomenon, but other types of links are not brought, such as influence/power, technical complementarities, and historical relationships [

27].

Therefore, since some of these relationships are not directional (e.g., historical relationships), an ecosystem must not necessarily be a directed network. In fact, it does make sense to start with an undirected network to decide on an ad hoc basis if directionality is needed.

Second, the ecosystem-as-structure still brings a rationale behind a central organization. It is true that the author rightfully called for executives to move away from an actor-centric (ego-network) to an activity-centric (whole-network) approach when designing and analyzing ecosystems. However, at the same time, Adner [

7] often uses terms like “focal organization,” “focal actor,” “focal firm,” and “focal firm’s aspiration” when addressing these same ecosystems. The main claim from the author is that concentrating too much on a central firm (ecosystem-as-affiliation) creates strategic myopia. However, ecosystem-as-affiliation seems not entirely free of that same bias. The perspective offers practicality to practitioners as they can quickly identify their organizations in the whole ecosystem. However, the problem is that when mapping their ecosystems, they may be tempted to always link the network to their company’s values and aspirations, generating a perspective bias.

Thirdly, interoganizational networks can obscure the diversification sought by specific organizations within an ecosystem. It is not always possible to deduce from the links surrounding a central firm which functions it performs in-house, and which are outsourced to other companies. Furthermore, even if such inferences were possible, conducting this type of analysis would be impractical for large networks.

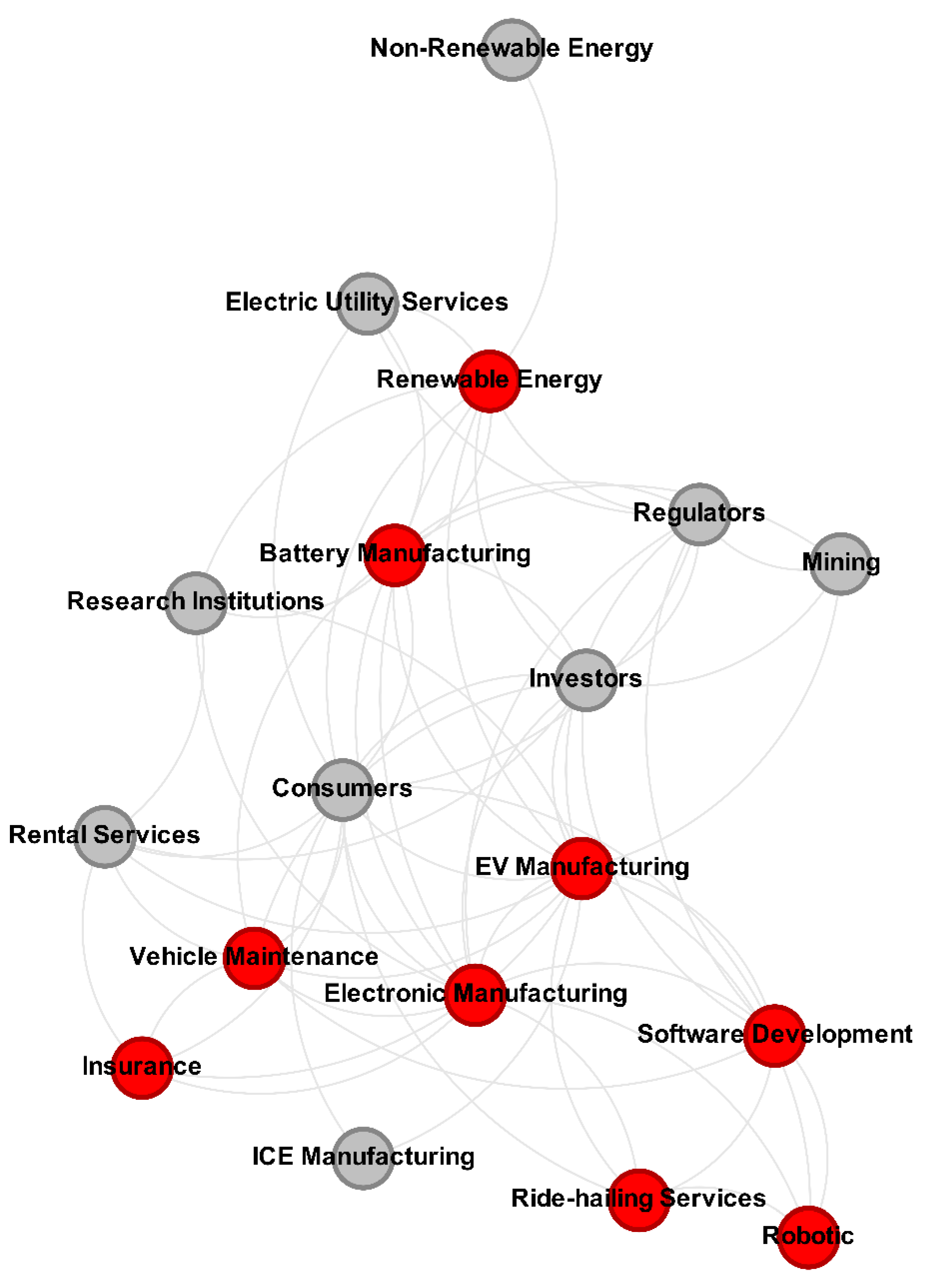

Then, simply working on variations or combinations of the existing perspectives would not be sufficient to address our phenomenon accurately. In fact, we need a paradigm shift. Instead of looking at ecosystems as an activity-centric network, which is still anchored to a focal actor’s perspective, has organizations as nodes and the flow of activities as links and conceal how the organizations approach an ecosystem, we advocate the need for interfunctional networks. In this perspective, we propose that an ecosystem can be defined as a directed or undirected whole network of aligned functions that interact to realize a value proposition for a particular group. This simple definition encompasses many of the previously discussed points:

Ecosystems may be directed or undirected but must always be a whole network to avoid the presumption of centrality from ego networks.

Differently from interoganizational networks that have organizations as nodes, in this perspective, functions (i.e., activities, operations, or work) act as nodes and are always in an n:n ratio. Many types of relationships are allowed between functions, such as transfer of activities (material, information, influence, and funds), technical complementarities, influence/power, and historical relationships.

There is alignment among the distinct functions, which depict some form of coordination.

The perception of the value proposition for someone is what motivates the existence of an ecosystem in the first place. Traditionally, this group is represented by consumers, but citizens can express it in ecosystems that address public services.

From the previous 10-K, we could identify many functions that were not necessarily attributed to an organization but still impacted Tesla’s operation, such as mining, ride-hailing & rental services.

Figure 4 brings a simplified version of this ecosystem using an interfunctional perspective:

It is worth noting that this is not Tesla’s ecosystem, unlike the previous examples we have discussed. Instead, it is an ecosystem that Tesla is a part of. Additionally, since we focus only on the key functions necessary for the ecosystem's value proposition, the graph's complexity is somewhat reduced.

We can assume that at least one organization supports each of these key functions meaning that the equivalent interoganizational network would have many more nodes, making the analysis exponentially more complex.

Furthermore, this graph can serve as a valuable tool for identifying overlooked opportunities that may not be apparent to some executives. For instance, while there are established connections between mining and battery production, the graph does not depict any mapped connections between mining and research and development. However, considering the potential environmental consequences associated with improper disposal of lithium batteries, ongoing efforts are being made to develop new technologies for lithium recovery [

68]. These developments could significantly impact mining operations, especially considering that the price of lithium reached an all-time high of

$37,000 USD per metric ton in 2022 (Statista, 2023). Given that 80% of lithium is utilized in battery manufacturing, the emergence of disruptive technologies that employ alternative chemical compounds for battery chemistry could have profound implications for the mining sector. Therefore, executives seeking novel market opportunities should not only analyze existing connections but also leverage the concept of structural holes [

46] to create and capture value.

Another characteristic of interfunctional networks is that they are more stable over time than interoganizational networks since a value proposition determines functions. This can be inferred when comparing Ecosystems 3 and 4: if any of the links in

Figure 3 are added or severed (due to contract termination, bankruptcy, approval of new legislation, etc.), the resulting interoganizational network becomes outdated. In contrast, by looking at

Figure 4, one can notice that interfunctional networks are much more stable since they represent the aligned functions that need to interact to realize a value proposition. While functions can certainly be added or removed, it is reasonable to assume that these changes occur less frequently.

Finally, considering the interconnection of functions required to materialize a value proposition further differentiates ecosystems from conventional interoganizational networks, offering a much clearer theoretical separation between them.

It is important to emphasize that the presented ecosystem is a simplified representation based on a single document source. It does not presuppose the dominance of any company but is grounded in the perception of a company that operates within this ecosystem. Consequently, it is likely that new functions and connections exist in this ecosystem. To effectively analyze ecosystems that rely on interfunctionals, it is advisable to employ a triangulation strategy that incorporates multiple sources of data.

Table 2 summarizes the main characteristics of each ecosystem perspective when integrated into the network theory.

4.1. The Business Ecosystem Footprint

So, where to position Tesla in the former ecosystem (

Figure 4)? Unlike the previous perspective, we are analyzing the whole value proposition

4 of the ecosystem Tesla is part of, not the ecosystem that needs to occur to materialize the company’s value proposition. The firm produces EVs, solar panels, some of its batteries, and software to control its current and future product functionalities. Therefore, Tesla is a company that executes multiple functions in this ecosystem as an EV manufacturer, Battery Component, Technology, Insurance, and Electricity Utility Company

5.

Hence, each organization participating in an ecosystem has a distinguishing footprint based on its functions directly related to the company’s strategy. In other word’, a company's Business Ecosystem Footprint (BEF) is the sum of all the functions it performs at different intensities, which is a deliberate strategic choice made by the organization in the quest for overall firm performance.

For example, over recent years, oil and gas companies have rebranded themselves as energy companies to transmit their efforts in transitioning towards cleaner energy sources. Namely, Statoil became Equinor, British Petrol adopted the acronym BP, and Total adopted TotalEnergies. However, if we select any two of these companies, they will probably play different functions in the ecosystem.

Even if they share the same functions, most likely, they will have different intensities on each function, meaning that they will have different BEFs. By intensity, we mean a moderating effect of the different functions performed by a company that would differentiate it from others. For instance, it could be the total amount of resources or R&D budget a company allocates for each function or the company’s market share for each. Testing these intensities opens an exciting research agenda with theoretical and methodological implications for the business and management literature.

The shift towards functions has a profound effect on ecosystem management since there can be virtual cycles where one side of the system (i.e., function) can catalyze for another. This means that not every function needs to seek its profit maximization; rather, it would be better to seek the overall companies’ financial benefit. Therefore, instead of looking at individual business units, leaders should be optimizing their resource allocation across their company’s footprint in order to generate overall firm performance. To illustrate this point, let's refer back to the ecosystem depicted in

Figure 4. Tesla's commitment to delivering Full Self-Driving (FSD) technology to its customers necessitates engagement in various functions such as Research, Electronic Manufacturing, Robotics, and Software Development. However, global regulatory constraints on the use of such technology in most places suggest that Tesla's focus in these areas is not primarily on profit maximization per se. Instead, it appears that Tesla utilizes the cash flow generated from other operations—such as EV Manufacturing, Battery Manufacturing, Vehicle Maintenance, Insurance, Renewable Energy, Electric Utility Services, and Software Development — to fund these FSD-related activities.

This strategic allocation of resources ensures that Tesla is prepared to scale up these operations when regulatory environments become more favorable. This has important implications, as the companies’ strategy departs from the conventional single industry wisdom that efficiency will lead to competitive advantage through cost reduction and better pricing [

22]. Moreover, this is relevant for both incumbents and newcomers offering products and services that align with the energy transition value proposition.

An additional insight we can infer is that while traditional network theory typically focuses on external dynamics, shifting the paradigm from interoganizational to interfunctional networks leads us to view the firm partly from the inside. This perspective emerges because the management's allocation strategy results in the restructuring of the entire organization's capabilities and resources. Then, if indeed the BEF is related to performance, as we are suggesting so far, executives should be asking the question of which are the best functions to allocate their resources on. Hannah and Eisenhardt [

59] have initiated a dialogue in that direction by exploring regions in the ecosystem that constrain it from operating at its full potential. They called these areas ecosystem bottlenecks, and they may contain none, one, or many firms. Hence, firms that occupy bottlenecks create value for the entire system and have a higher chance of capturing value for themselves.

The predicament of such a definition is that the notion of bottlenecks is based on complementarities, being technical components that are critical for the well-being of the ecosystem at that time. As discussed in the past chapters, this interpretation may be appropriate when analyzing platforms or technological innovations. However, it may be myopic to many other relationships relevant to realizing a value proposition, such as the energy transition.

Another relevant question is how to identify such critical regions of the ecosystem. Besides archival material, the authors have used a mix of expert and executive interviews. Therefore, they qualitatively identified these key areas that constrain the entire system over time since bottlenecks are not static and may evolve over the lifecycle of the ecosystem [

59].

There is inherently nothing wrong with using these methods. However, from the rich literature developed over the decades on social networks, we can also deploy quantitative metrics to map these regions, serving as a triangulation to the qualitative approaches. To enumerate one instance, centrality measures may be used in this context. Several measures could be deployed, such as degree, closeness, betweenness, and eigenvector. Exploring their correlation to firm performance and their internal coherence for such a task goes beyond the scope of the current work. However, this opens an exciting opportunity to revisit well-established metrics under a new theoretical lens to inform executives, scholars, and policymakers.

5. Conclusions

When examining complex social phenomena like the energy transition, the collaboration of numerous stakeholders is often essential, as emphasized by Sustainable Development Goal 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). In business and management literature, two strategic frameworks, namely the Business Ecosystem Theory (BET) and the Social Network Theory (SNT), have gained attention when analyzing these interconnected systems. While previous studies attempted to integrate these theories partially, they did not explore their similarities and differences and how different interpretations of the BET impact such integration.

Through an examination of their history and theoretical foundations, we found that although the two theories address similar phenomena, they are not identical. Both assume that organizations are part of larger dynamic systems with interconnected actors. However, they differ in several aspects, including their unit of analysis, focus, decomposability, types of relationships, market segment, and worldview. While the BET is suitable for analyzing phenomena that require a cross-industry perspective with non-decomposable links, such as the energy transition, it lacks the mathematical formality and rich history found in the SNT. Therefore, there is a need to combine both theories to develop novel approaches that better represent real-world phenomena in a pragmatic, reliable, generalizable, and reproducible manner. These aspects are crucial for building a robust science.

In this study, we have discerned three principal theoretical streams that comprise the Business Ecosystem and examined their intersection with Social Networks. The initial ecosystem category is centered on nongeneric technical complementarities and modularity, which is well-suited for tackling software development and platform management challenges, including APIs, compatibility, and openness. Upon integration into networks, it yields directed or undirected ego networks that are simple to chart but frequently assume the centrality of a particular enterprise, leading to the potential for unintended strategic bias.

When stakeholders such as scholars, practitioners, or policymakers invoke the concept of a "Company Ecosystem," they employ this line of reasoning. The theoretical construct known as ecosystem-as-affiliation is predicated on a central focal firm and emphasizes the activities carried out by the said entity. Combined with networks, it gives rise to directed ego networks that presume the centrality of the firm.

The third theoretical stream, ecosystem-as-structure, similarly revolves around the flow of activities but diverges from the previous categories because it does not technically assume centrality when integrated with networks. This is because it encompasses not just immediate links to the focal firm but also higher-order links that may lie beyond the purview of the company's control. Nonetheless, some perspective bias may persist within this theoretical stream, as it establishes a structure whereby a group of links is centered around a local firm while another group is not. The resultant graph is a directed whole network with subjective boundaries, as there is a perpetual tension surrounding the number of higher-order links to be included in the analysis, thus increasing its complexity and demands.

Our investigation has led us to realize that solely focusing on variations or combinations of established viewpoints is inadequate for accurately addressing complex phenomena, such as the energy transition. Interoganizational networks remain partially constrained by the concept of a focal firm, thereby giving rise to strategic bias even when employing the ecosystem-as-structure approach. Additionally, interoganizational networks obscure the diversification strategies of organizations, such as those employed by O&G companies rebranding themselves as energy firms. Finally, the conventional approach to modeling actor links is limited to nongeneric technical complementarities or activity flows, failing to account for other relevant types of relationships such as regulation, influence/power, and historical connections.

Thus, a paradigm shift is imperative. Rather than viewing ecosystems as activity-centric networks, we propose a shift toward interfunctional networks. From this perspective, an ecosystem is defined as a directed or undirected whole network of aligned functions that interact to realize a value proposition for a particular group. This new approach offers several advantages over interoganizational networks, including reduced complexity due to the assumption that each function has at least one supporting organization, greater stability over time, and a clearer theoretical delineation between extant theories.

In interpreting business ecosystems, the logic of interfunctional networks involves creating a board game where executives position their companies across multiple functions to reassess their allocation and diversification strategies. This deviates from the current predominant practice of building ecosystems with a particular firm in mind, resulting in interoganizational networks that obscure which activities are performed internally and which are outsourced. Analyzing the nature of each link on the graph to infer such information for large networks would be impractical.

This new approach contributes to the emergence of a strategic construct called the Business Ecosystem Footprint (BEF), an individual marker indicating how a particular organization is positioned across the network of functions. Even if two companies work in the same segment and perform the same functions, they will likely have different intensities on each of them, resulting in different BEFs. The intensity would be a moderating effect of a company's different functions that differentiate it from others, such as resource allocation or market share.

To map the critical functions managers should allocate their resources, they can use different strategies such as expert and executive interviews and archival material. Nevertheless, the rich literature on social networks allows quantitative metrics, such as centrality measures, to map these regions and serve as triangulation to other methods.

This work aimed to initiate a dialogue with existing literature and propose a new way of viewing and interpreting ecosystems. It is not intended to be a definitive guide but rather the start of a new conversation, generating new questions and ideas to explore the particulars, limitations, modifications, and new applications of this new theoretical perspective.

We want to assist ecosystem scholars entering this dialogue by proposing future research agendas. First, we address mapping ecosystems through functions, a crucial first step that can be quite laborious. While Name Entity Recognition (NER) algorithms exist for identifying organizations in interoganizational networks, no validated algorithm exists for identifying functions. One potential avenue for research is exploring whether Large Language Models (LLM), such as the artificial intelligence chatbot ChatGPT developed by OpenAI, could assist in identifying functions to reduce the time of this task and make the process more attractive to busy managers.

Next, we would be the most appropriate centrality measures and intensities to design the Business Ecosystem Footprint (BEF). Various centrality measures are available, such as closeness, betweenness, and eigenvector. At the same time, we have recommended three intensities: total allocation per function, R&D allocation per function, and market share of each function. Future studies must explore the rationale behind employing each variable and construct a normative framework that determines the optimal combination for specific scenarios.

Moreover, we suggest exploring how the BEF is related to firm performance. Using interfunctional network logic in business ecosystems and the BEF construct opens new avenues for creating and quantitatively testing hypotheses about a firm's performance based on its ecosystem and strategic allocations. Different numerical strategies, ranging from Multiple Regression to Structural Equation Modeling, could be employed for this purpose.

Finally, the BEF is a consequence of the interfunctional networks previously mapped. Therefore, different data sources could result in different BEFs, impacting their correlation with firm performance. Conducting a sensitivity analysis to examine the impact of different mapping strategies on the BEF and firm performance is necessary to validate this construct's applicability.