Submitted:

31 August 2024

Posted:

02 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

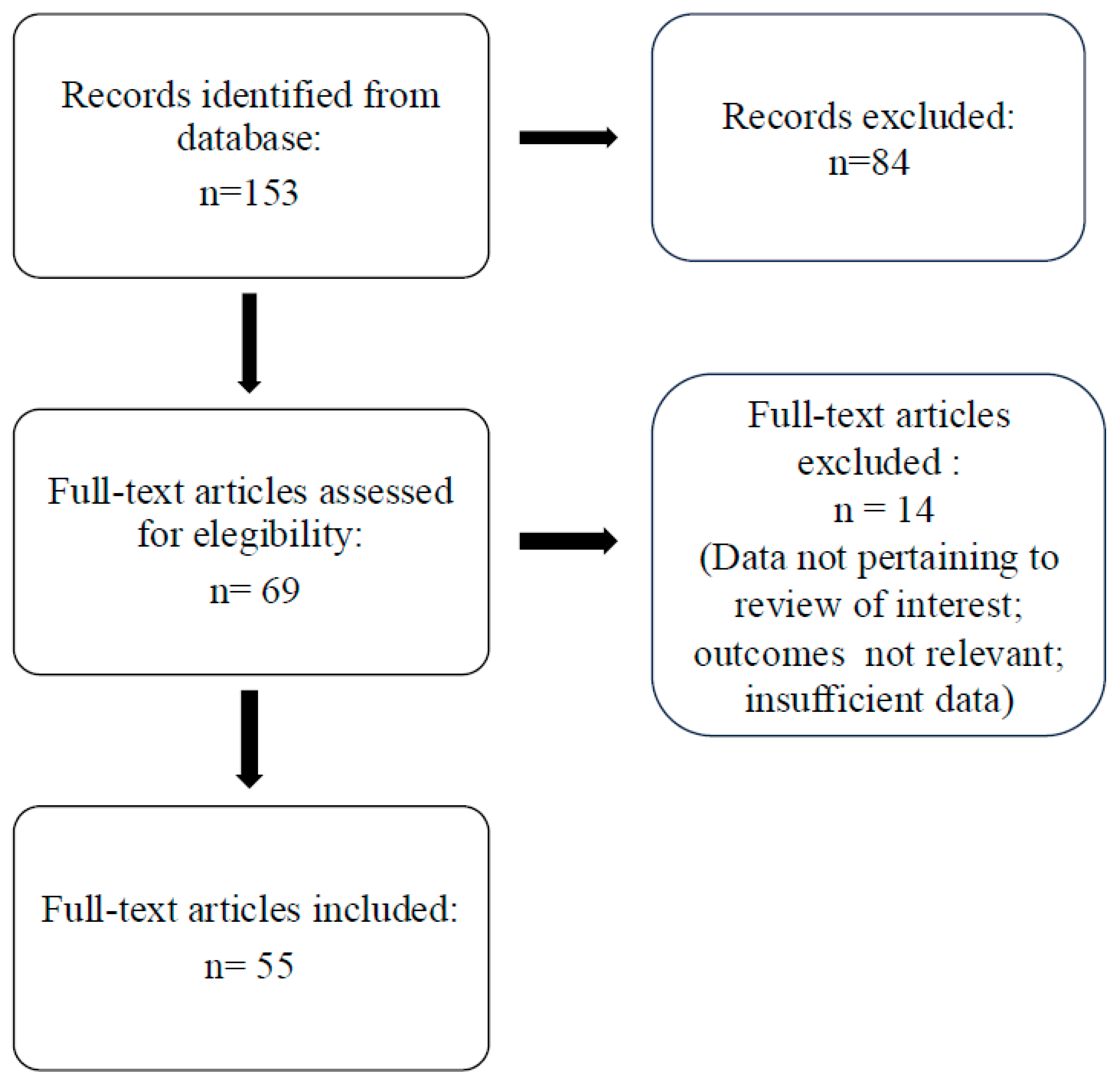

Methods

Results

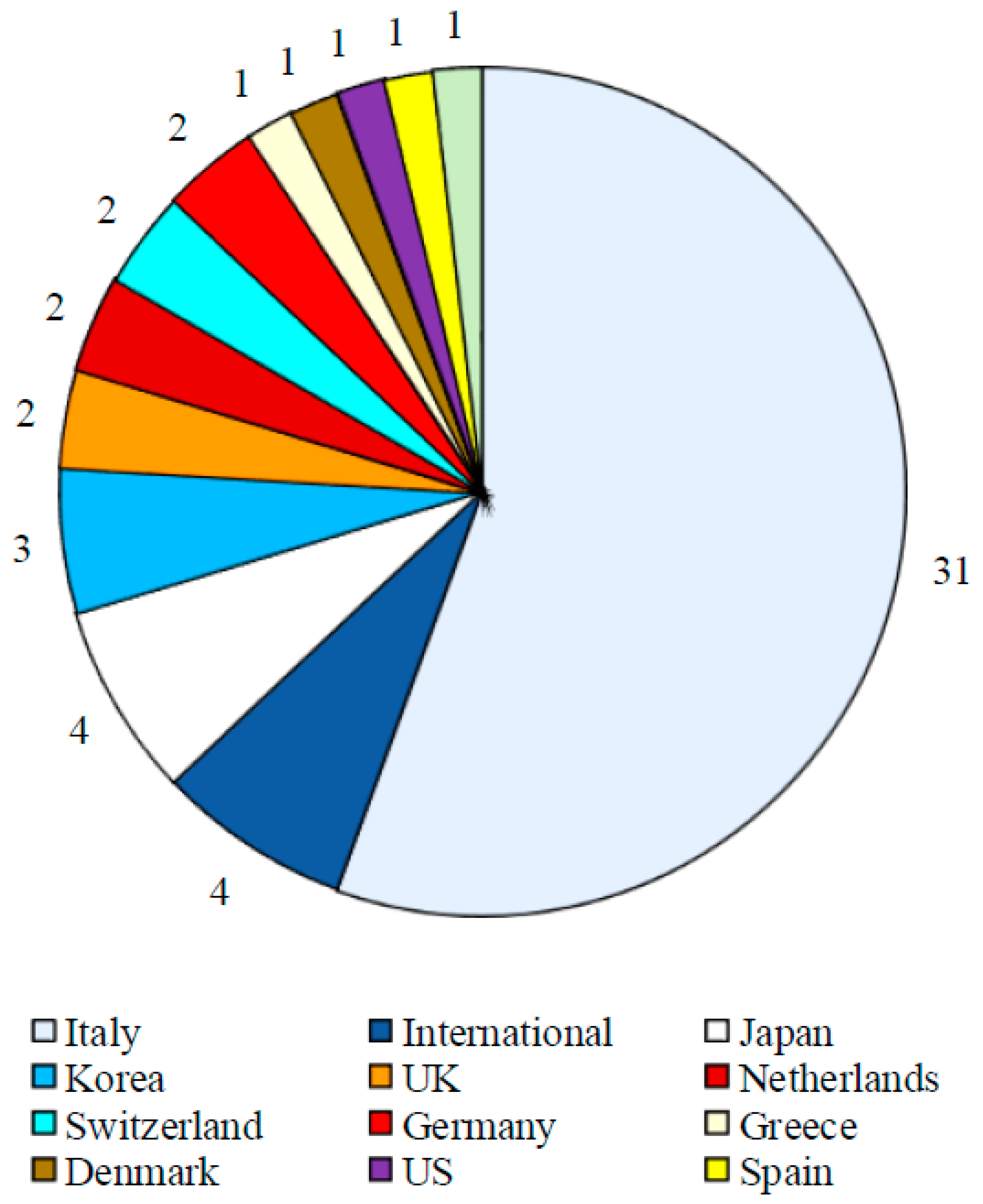

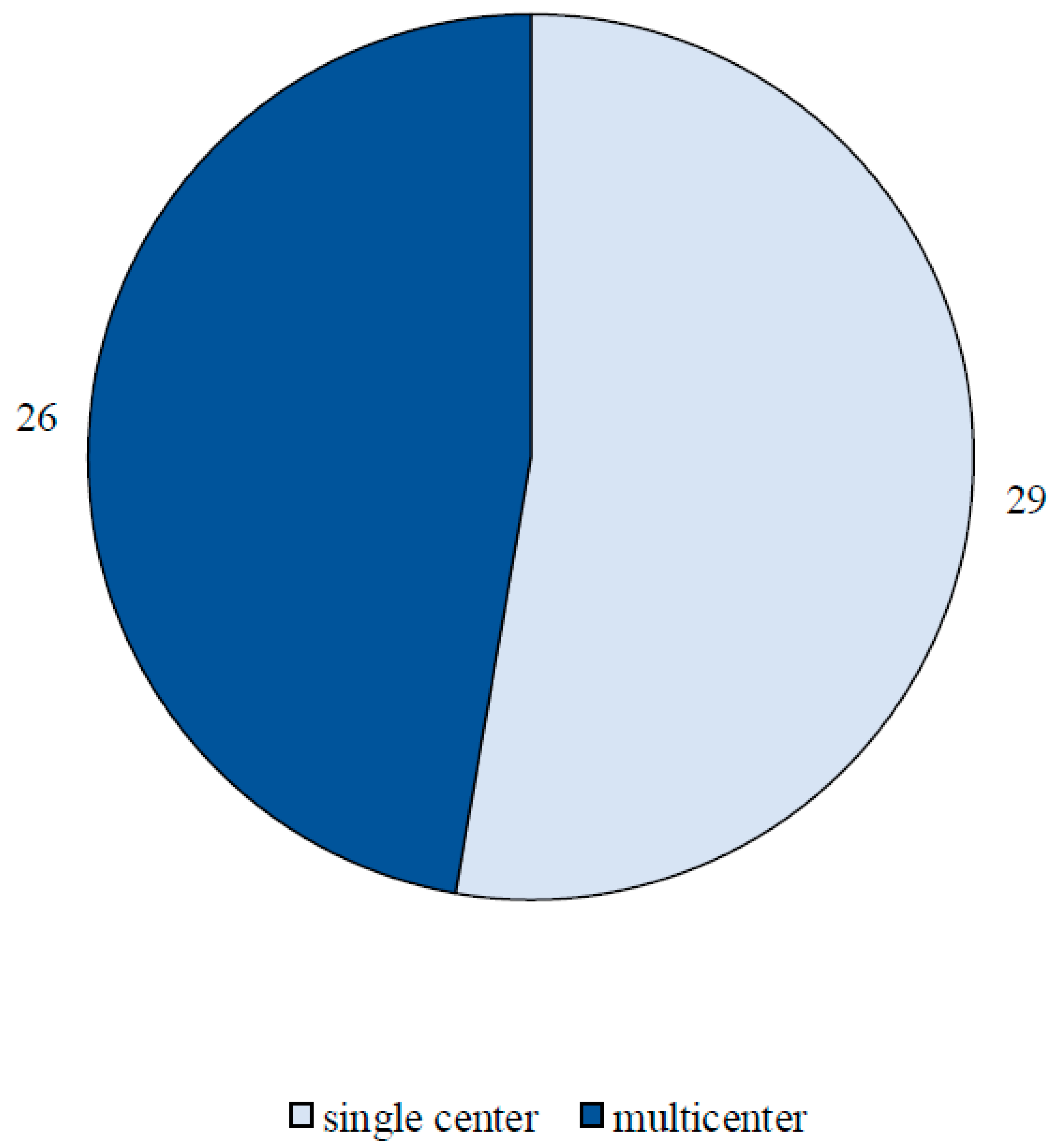

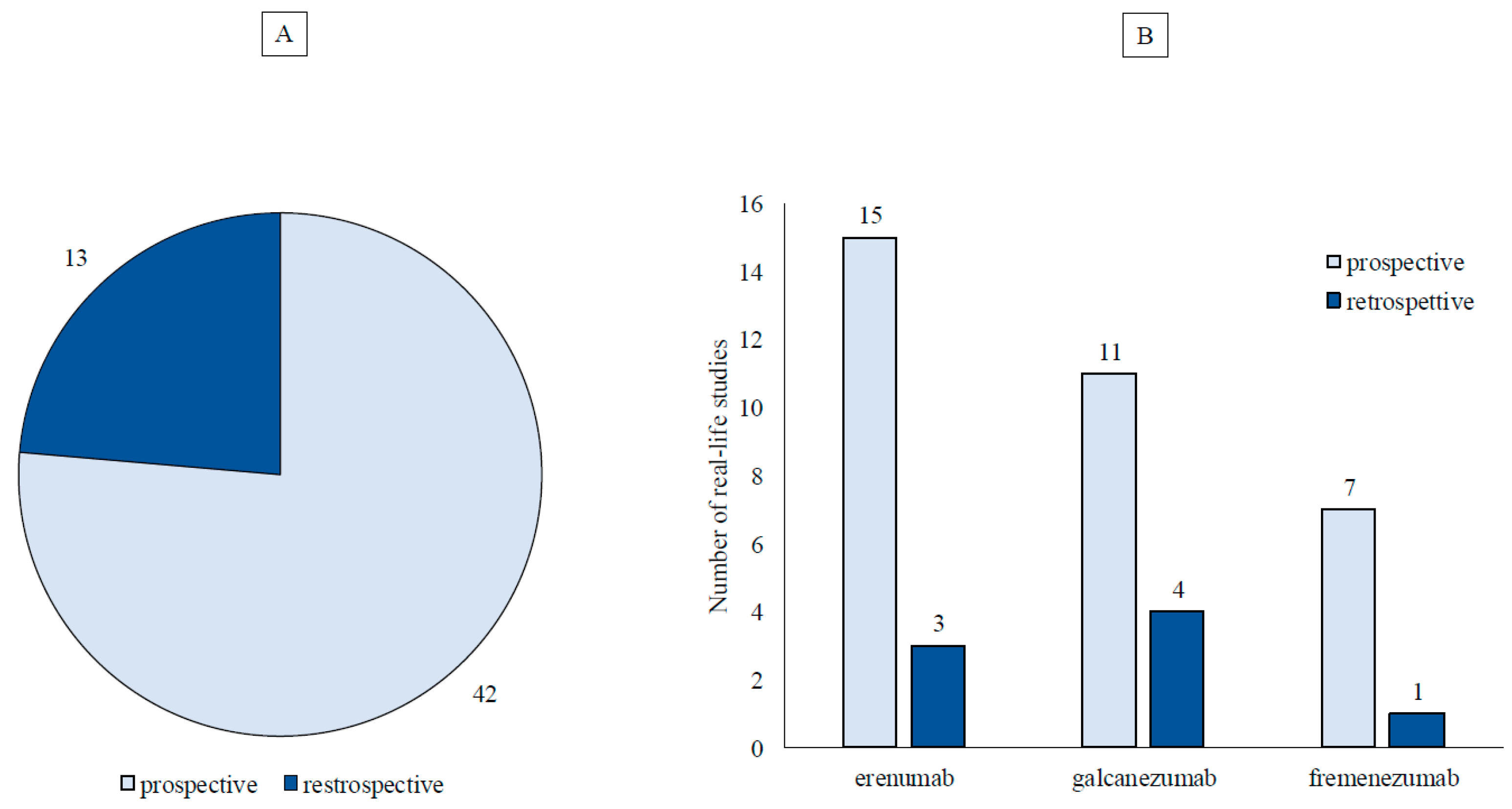

Study Characteristics

| Author/ Year |

N° pts | Observation period | Study Type/Center/National-International | Primary endpoint | Secondary endpoints | Results | Safety findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbanti et al, 2019 [22] | HFEM/CM: 13/65 | 8 weeks | P S N=Italy |

Change in MMD at weeks 5-8 vs baseline | Change in MAI, >50%, >75% and 100% RR and any variation in VAS and HIT-6 scores. |

Primary endpoints: HFEM: MMD -7; CM: MH9,7Ds – 15. Secondary endpoints: HFEM: MAI – 7; VAS -7; HIT-6 -30; ≥ 50% ≥ 75% and 100% R were 100%. CM: MAI − 15, VAS − 3, and HIT-6 – 12.8, ≥ 50% R 87.5%, ≥ 75% R 37.5%. |

One AE (injection-site erythema) in a single patient (1.3%). |

| Barbanti et al, 2020 [23] | HFEM/CM: 103/269 | 12 weeks | P M (n=9) N=Italy |

Change in MMD at weeks 9-12 vs baseline in HFEM and CM. | Change in MAI, >50%, >75% and 100% RR and any variation in VAS and HIT-6 scores. |

Primary endpoints: HFEM: MMD -4.5; CM: MMD -9.3. Secondary endpoints: HFEM: VAS -1.9; HIT -10.7; MAI from 12.0 (IQR 10.0–14.0) to 5.0 (IQR 3.0–7.0); RR: ≥50% 59.4%; ≥75% 16.8% and 100% 1. CM: VAS -1.7 ± 2.0; HIT -9.7; MAI from 20.0 (IQR 15.0–30.0) to 8.0 (IQR 5.0–15.0; RR: ≥50% 55.5%; ≥75% 22.4% and 100% 1.1%. |

Constipation (8.8%), usually rated as mild; severe in one case and classified as a SAE. |

| Scheffler et al, 2020 [24] |

EM/CM: 26/74 | 12 weeks | R S N=Germany |

RR >50% | % of conversion CM →EM; improvement of intensity and duration of pain; % AEs |

Primary endpoints: EM: 57.7%; CM: 41.9%. Secondary endpoints: 53% CM → EM; 70.5% and 58.9% improvement of intensity and duration of pain respectively. |

AEs: 42%: 23.8% constipation, 23.8% injection side skin symptoms or itching; 16.7% fatigue or a feeling of exhaustion 9.5% insomnia. |

| Ornello et al, 2020 [25] | CM: 91 | 24 weeks | P M (n=7) N=Italy |

% of conversion to EM from baseline to months 4–6 of treatment and during each month of treatment. |

Change in MHD, AMD and NRS. |

Primary endpoints: 12.1% discontinuation before month 6 due to ineffectiveness, 68.1% CM →EM. Secondary endpoints: MHD from 26.5 (IQR 20–30) to 7.5 (IQR 5–16; p < 0.001), AMD from 21 (IQR 16–30) to 6 (IQR 3–10; p < 0.001) and NRS from 8 (IQR 7–9) to 6 (IQR 4–7; p < 0.001). Significant decreases both in converters and in non-converters. |

1 pt discontinued the treatment before month 6 for AE. |

| Russo et al, 2020 [26] | CM: 90 (failure to ≥4 migraine preventive medication classes) |

24 weeks | P S N=Italy |

> 30% reduction in MHD, after ≥3 months of therapy switched to monthly erenumab 140 mg | Disease severity, migraine-related disability and impact and validated questionnaires to explore depression/anxiety, sleep, and QoL. Pain Catastrophizing Scale, Allodynia Symptom Checklist-12 and MIGraine attacks-Subjective COGnitive impairments scale (MIG-SCOG). |

Primary endpoints: after 3 doses of 70 mg 70% R, 30% switched to 140 mg; after 6 doses 29% R. After 3 doses MHD -9.7 (p<0.001) and after 6 doses -12.2 (p<0.001). RR: ≥50% of MHD after 3 and 6 doses: 53% and 70%; Secondary endpoints: pain severity, migraine-related disability, and impact on daily living, QoL, Pain Catastrophizing and allodynia (all p<0.001) scales, quality of sleep, symptoms of depression or anxiety (p<0.05) but not MIG-SCOG also improved. |

No new AE was reported. |

| Lambru et al, 2020 [27] |

CM: 162 |

24 weeks | P S N=UK |

Change in MMD at weeks 24 vs baseline |

RR: 30%, 50%, 75%; % stopped MO HIT-6 score |

Primary endpoints: MMD: -7.5 (p<0.001); MHD: -6.8 (p<0.001); Secondary endpoints: RR: 60%, 38%, 22%; MO: 54% →25 %; HIT-6: -7.5 (p=0.01). |

At least one AE reported by 48% at month 1, 22% at month 3 and 15% at month 6. The most frequent AEs: constipation 20% and cold/flu-like symptoms 15%. |

| Barbanti et al, 2021 [4] | HFEM/CM: 60/182 |

48 weeks |

P M (n=15) N=Italy |

Change in MMD and MHD at weeks 45-48 vs baseline. |

Change in MAI >50%,>75%, 100%, RR and any variation in VAS and HIT-6 scores at weeks 45-48. |

221 considered for effectiveness, 242 for safety. Primary endpoints: HFEM: MMD -4.3; CM: MHD -12.8 Secondary endpoints: HFEM: VAS -1.8; HIT-6 -12.3; MAI from 11.0 ([IQR] 10.0–13.0) to 5 (IQR 2.0–8.0); RR: ≥50% 56.1%; ≥75% 31.6%; 100% 8.8%; CM: VAS -3.0; HIT-6 - 13.1; MAI from 20.0 (IQR 15.0–30.0) to 6.0 (IQR 3.8–10.0) RR: ≥50% 75.6; ≥75% 44.5%; 100% 1.2%. 83.6% CM → EM. |

AEs: 18.6% usually mild. The most common: constipation 10.3%, injection site erythema 3.3%. 1.2% patients experienced SAEs: 1) Paralytic ileus (treatment related) 2) Non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (not related) 3) Myocardial infarction (not related). |

| Ornello et al, 2021 [28] | HFEM/CM: 374/1036 |

12 weeks | R M (n=16) I=Italy, UK, Germany, Czech Republic, Russian Federation, Australia. |

RR: 0–29%, 30–49%, 50–75%, and ≥75% Comparison between men and women |

Primary endpoints: RR≥75%: 20.2%; RR:50–74%: 20.7%; RR:30–49% 15.3%; RR:0–29%: 31.4; Secondary endpoints: gender did not influence the efficacy of outcomes. |

||

| de Vries Lentsch et al, 2021 [29] |

HFEM/CM: 54/46 | 24 weeks | P M (n=2) N=Netherlands |

MMD after 6 months vs baseline. |

AMD, RR, well-being and coping with pain. |

Primary endpoints: MMD: -4.8 (p <0.001); Secondary endpoints: AMDs (p <0.001) in all months; RR ≥50%: 36% in ≥3/6 months, and 6% in all 6 months; RR ≥30% 60% and 24%, respectively. Well-being (p<0.001) and coping with pain (p<0.001). |

AEs: 93%. Most common: abdominal complaints 72%, including constipation 65%, fatigue 43% and injection site reactions (27%). |

| De Matteis et al, 2021 [30] | HFEM+CM:32 | 52 weeks 8-weeks follow-up after treatment completion |

P M (n=2) N=Italy |

RR and change in MMD during weeks 1-4 after treatment completation as vs baseline and the last 4 weeks of treatment. | RR and changes in MMD AMD, NRS in who did not restart treatment during weeks 5-8 after treatment completion vs last 4 weeks of treatment and with baseline |

Primary endpoints: RR >50%: 56%; RR 50-75%: 34%; RR 75-100%: 22%; MMD: -19 (p<0.001) last 4 weeks of treatments, -15 (p<0.001) weeks 1-4 after treatment completation; Secondary endpoints: AMD, NRS: during the last 4 weeks of treatment (p<0.001); weeks 1-4 after completion (p<0.001) lower than baseline (MMD and AMDs p<0.001, NRS p=0.005). 56% RR ≥ 50% from baseline. At week 4 after treatment completion, 31% restarted treatment due to disease rebound. |

NA |

| Andreou et al, 2022 [31] | CM: 135 | 2 years | P S N=England |

Sustained effectiveness in 24 months of treatment | MMD, HIT-6 at month 6, 12, 18 |

Primary endpoints: RR:30%: 23%; RR:50% and 75%: 16% and 8% respectively. Secondary endpoints: MMD: (p<0.001) HIT-6: (p<0.001) at all timepoints. |

NA |

| Pensato et al, 2022 [32] | CM+MOH: 149 (previously failed onabotulinum toxin A) |

12 weeks | P M (n=5) N=Italy |

RR 50%, 75% | MHD, MAI, CM →EM |

Primary endpoints: RR >50%: 51%; RR >75%: 20%. Secondary endpoints: MHD: -11.3 (p<0.001) MAI: -29.3 (p<0.001) CM → EM: 64% |

No SAEs observed. |

| Ornello et al, 2022 [33] | HFEM+CM: 1215 | 9-12 weeks | P M (n=16) I=Italy, UK, Germany, Czech Republic, Russian Federation, Australia. |

RR: 0-29%, 30-49%, 50-74%, and ≥75% at weeks 9-12 vs baseline.For each response category median MMD and HIT-6 at baseline and at weeks 9-12. | Categorization of residual MMD at weeks 9-12: 0-3, 4-7, 8-14, ≥15. 4 categories of HIT-6: ≤49, 50-55, 56-59, and ≥60. Calculations in men and women. |

Primary endpoints: RR 0-29%: 31.4%; RR 30-49%:15.3%; RR 50-74%: 32.6% and RR ≥75%: 20.7%. Secondary endpoints: 0-3 residual MMD: 20.2%, 4-7: 36.5%, 8-14: 24.6%, ≥15: 18.7%. of R (4-7 MMD) 50-74 %: 62.1% and (8-14) 23.7%; of R (0-3) ≥75%: 74.2% (4-7) 25.8%. No differences in gender for residual MMD; HIT-6 distribution less favorable in women in the 0-29% (p=0.004) and in the 30-49% (p=0.003) response categories. |

NA |

| Gantenbein et al, 2022 [34] |

EM+CM: 172 |

24 weeks |

P M (n=13) N=Switzerland |

Impact on QoL, migraine-related impairment and treatment satisfaction HIT-6, mMIDAS, Impact of Migraine on Partners and Adolescent Children (IMPAC), TSQM-9 (Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication) after 6 months | HIT-6 -7.7 (p <0.001), the mMIDAS - 14.1 (p<0.001), MMD -7.6 (p<0.001) and AMD - 6.6 (p<0.001). IMPAC: -6.1 (p<0.001). Mean effectiveness of 67.1, convenience of 82.4 and global satisfaction of 72.4 of patients in the TSQM-9. | 99 AEs and 12 SAEs observed in 62 and 11 patients, respectively. All SAEs as not related to the study medication. |

|

| Cetta et al, 2022 [35] | 15 over 65 (O65) and 15 under 65 (U65), matched for sex HFEM/CM:12/18 |

24 weeks | P S N=Italy |

Change in MHD and MMD vs baseline between young and elder migraine patients |

MAI, AMDs, HIT-6, MIDAS, NRS, and ASC-12 after 3 (M3) and 6 (M6) months of treatment. |

Primary endpoints: baseline MHD and MMD of both groups: 20. Mean age was 70 (65-76) and 45 (19-55) in the O65 and U65 group, respectively. At M3 and M6 no statistical differences between groups. Secondary endpoints: at M3 and M6, reduction of all clinical features under examination, without statistically significant differences between the 2 groups. |

Similar proportion of AEs (M3 and M6, p= 1.0) in each group. |

| Troy et al, 2023 [36] | CM: 177 | 17-30 months | P M (n=4) I=Ireland, UK, USA |

PROM/QoL outcomes over a period 17–30 months. . |

HIT-6, MIDAS, MSQ before starting treatment and at intervals of 3–12 months after starting treatment. |

Primary endpoints: 61.6% significant improvement after 6–12 months. 54.8% on treatment (median of 25 months). Secondary endpoints: from baseline to 25-30 months: HIT-6: -14; MIDAS: -101 MSQ: -30 |

38.4% stopped during the first year, due to lack of efficacy and/or possible AEs. |

| Pilati et al, 2023 [37] |

CM: 88 (CM+MO: 84) |

12 weeks |

P M (n=6) N=Italy |

Variation in MEQ, PSQI, SCI, (Sleep Condition Indicator) ESS, MIDAS, HIT-6 at T3 and later vs baseline |

Changes in MMD, DSMs, RR 30%, 50%, 75%, and 100% after the first dose; |

Primary endpoints: MEQ morningness → intermediate: p < 0.05; PSQI score > 5 at baseline in 64% of patients and no variation at follow up. SCI significant increase at T3 (p = 0.0144) not confirmed during later (p<0.05). ESS no statistical significance during follow ups At T3 MMD: -10.6 (p<0.001) in patients receiving 70 mg and -16.4 (p<0.001) in 140 mg (p<0.001). A significant difference between T3 and T9 (p=0.014) not confirmed in T3 vs. T12 (p = 0.766). Secondary endpoints: after the first dose of 70 and 140 mg (T1), RR >30%: 13% and 18%; RR >50%: 29% and 34%; RR> 75%: 13% and 26% and RR 100% 0% and 3% respectively. MIDAS and HIT-6 during all the evaluations vs baseline (p < 0.05). |

10 different AEs in 37.5%. The most common: constipation in 10.2%. No AE led to withdrawal. 5.7% complained of insomnia. |

| Buture et al, 2023 [3 8] |

82 New Daily Persistent Headache and Persistent Post-Traumatic Headache | over a two to three years |

R M (n=3) I= Ireland, UK, USA |

Improvement of QoL after 30 months vs baseline |

Primary endpoints: significant improvements in QoL in 1/3 over a period of 11–30 months, with a 35% persistence after a median of 26 months of treatment. |

- a)

- Fremanezumab

| Author/ Year |

N° pts | Observation period | Study Type/Center/ National-International |

Primary endpoint | Secondary endpoint | Results | Safety findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbanti et al, 2022 [39] | 67 (HFEM/CM: 21/46) |

12 weeks | P M (n=9) N=Italy |

Change in MMD for HFEM and MHD for CM at weeks 9–12 vs baseline. | Change in MAI, NRS, HIT-6 and MIDAS and ≥ 50%, ≥ 75% and 100% RR at the same time intervals. |

Primary endpoints: MMD: -4.6 (p<0.05) MHD: -9.4 (p<0.001). Secondary endpoints: MAI:-5.7 (p<0.05), -11.1(p<0.001); NRS: -3.1, -2.5 (p<0.001) MIDAS: -58.3 (p<0.05), -43.7 (p<0.001) in HFEM and CM respectively; HIT-6: -18.1(p<0.001) in HFEM. The ≥ 50%, ≥ 75% and 100% RR at week 12 were 76.5%, 29.4% and 9.9% in HFEM and 58.3%, 25% and 0% in CM |

5.7% reported TEAEs: 1 injection site erythema (1.9%), 1 abdominal pain (1.9%) and 1 neck pain and somnolence (1.9%) |

| Driessen et al, 2022 [40] | 1003 (HFEM/CM: 416/587) |

24 weeks | R M (n=421 clinicians: 240 neurologists, 80 general practitioners, 36 pain management specialists, 21 psychiatrists, 38 PAs or NPs, and 6 other headache specialists) N=Netherland |

Changes in MMD and MHDs at month 6 | NA | MMD/MHD: −7.7 and −10.1 in HFEM and CM respectively; −10.8 in the MO sub-group; −9.9 in the MDD subgroup, −9.5 in the GAD subgroup, and -9.0 in the prior exposure to a different CGRP mAb subgroup. | NA |

| Barbanti et al, 2023 [41] | 410 (HFEM/CM: 214/196) |

24 weeks | P M (n=28) N=Italy |

Change in MMD and MHD at weeks 21–24 vs baseline | Changes in MAI, NRS, HIT-6, MIDAS and ≥50%, ≥75%, and 100% RR at weeks 21–24 vs baseline. |

Primary endpoints: MMD: -6.9 (p<0.001) MHD: -14.2 (p<0.001) Secondary endpoints: ≥50%, ≥75% and 100% responders: HFEM: 75.0, 30.8 and 9.6%; CM: 72.9, 44.8 and 1%; NRS: -3.4, -2.7; MAI: -8.0, -15.1; HIT: -6, -8.0; -20.9, -24.3; MIDAS: -55.0, -72.6 respectively in HFEM and CM. |

NA |

| Argyriou et al, 2023 [42] | 204 (HFEM/CM:107/97) |

12 weeks | P M (n=6) N=Greece |

A minimum 50% decrease in MHD at T1 vs T0 and the percentage of 30%, 75%, and 100% reduction in mean MHD | Changes in mean MHD, migraine severity, mean days with intake of any acute headache medications, MIDAS, HIT-6, EQ-5D and QOL |

Primary endpoints: reduction MHD: 83.5% HFEM and 62.6% CM patients . Secondary endpoints: MHD: -6.5, -9.4 respectively in HFEM and CM; p<0.001 in migraine severity, mean days with intake of any acute headache medications, MIDAS, HIT-6, EQ-5D and QOL |

25% of patients (n=26) experimented treatment-associated toxicity, 43.8% (n=21) erenumab versus 16.3% (n=7) galcanezumab versus 15.4% (n=2) fremanezumab |

| Cullum et al, 2023 [43] | 91 (HFEM/CM:-/91) |

12 weeks | P S N=Denmark |

Reduction ≥30% in MMD from baseline to weeks 9–12. | Responders ≥50 and ≥75% and proportion of patients reporting AEs. |

Primary endpoints: MMD: -7.3; MHD: -8.2. ≥30% RR: 65% Secondary endpoints: ≥50 and ≥75% RR: 51% and 24% |

NA |

| Suzuki et al, 2023 [44] | 127 (HFEM/CM:54/73) |

24 weeks | P S Japan |

Change MMD/MHD and responders at 6 months | Predictors of responder at 6 months |

Primary endpoints: MMD: −6.9 MHD: −9.7 ≥50%, ≥75% and 100% responders: HFEM: 90.4, 36.5 and 9.6%; CM: 52.2, 14.9 and 1.5% Secondary endpoints: higher percentage of nausea at baseline were associated with a≥50% MMD reduction at 6 months. |

NA |

| Caponetto et al, 2023 [45] | 83 (HFEM/CM:16/67) |

52 weeks | P M (n=17) Italy |

Change MMD, MHD, RR and persistence in medication overuse at 3-6 and 12 months | Change in MAI, MIDAS andHIT-6 at 3-6 and 12 months |

Primary endpoints: MMD: -5, -6 and -6.5 (p<0.001) MHD: -11, -13 and -15 (p<0.001) ≥50%, ≥75% and 100% responders at 12 months: HFEM: 78.6, 35.7% and 14.5; CM: 75.9%, 37% and 56% Secondary endpoints: MAI: -6, -7.5 and -7; -14, -15 and -15.5; HIT-6: -11, -20 and -18.5; -11, -12.5 and -15; MIDAS: -18, -18 and -18; -48, -52 and – 53.5 respectively in HFEM and CM. |

AEs 9.6% Discontinued for tolerability 1 pts (1.2%) local allergic reaction at site injection, constipation: 7.2%, injecion site reactions 3.6% |

| Barbanti et al, 2024 [6] | 130 (HFEM/CM: 49/81) |

48 weeks | P M (n=26) N=Italy |

Change in MMD and MHD at weeks 45-48 vs baseline | Changes in MAI, NRS, HIT-6, MIDAS and ≥50%, ≥75%, and 100% RR at weeks 45-48 vs baseline. ≥50%, ≥75%, and 100% RR in patients with psychiatric comorbidities and MO. |

Primary endpoints: MMD: -6.4(p<0.001) MHD: -14.5 (p<0.001) Secondary endpoints: ≥50%, ≥75% and 100% responders: HFEM: 75.5%, 36.7%, and 2%; CM: 71.6%, 44.4%, and 3.7%; pts with psychiatric comorbidities: 60.5%, 37.2%, and 2.3%; CM with MO: 74.2%, 50%, and 4.8%; CM with MO and psychiatric comorbidities: 60.9%, 39.1%, and 4.3%. NRS: -3.4, -3.4; MAI: -6, -16.5; HIT-6: -16.9, -17.9; MIDAS: -50.4, -76.6 respectively in HFEM and CM. |

TEAEs occurred in 7.8% (6/130) of patients treated with fremanezumab for at least 48 weeks |

- b)

- Galcanezumab

| Author/ Year |

N° pts | Observation period | Study Type/Center/ National-International |

Primary endpoint | Secondary endpoint | Results | Safety findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Takizawa et al, 2021 [46] |

52 pts (EM/CM: 25/27) | 12 weeks |

R S N= Japan |

Change in MMD, MHD, 50% RR, 100% RR. NRS, MAI | Changes from baseline in associated symptoms; premonitory symptoms. |

Primary endpoints: MMD: - 4.4 (p < 0.001) in EM. MHD: - 7.3 (p < 0.001). MAI in EM: -4 (p < 0.001). MAI in CM: -6 (p < 0.001). The ≥50% and 100% RR: 76.0% and 20.0% in EM and 48.1% and 7.4 %in CM. NRS: -2 in EM; -1 in CM (both p < 0.001) Secondary endpoints: improvement in photophobia, phonophobia, nausea/vomiting 64.9%, 50.0%, 63.9% respectively. Premonitory symptoms at baseline: 46.1%. Afrer 12 weeks 62.5% reported premonitory symptoms without subsequent headache. |

Injection site reactions at first, second and third injections: 26.9%, 17.3%,20.0%; constipation: 7.7%; fatigue: 5.8%; burning sensation: 3.8%; lightheadedness: 3.8%; others:19%. |

| Vernieri et al, 2021 [47] |

165 (EM/CM: 33/130) |

24 weeks |

P M (n=13) N= Italy |

Change in MMD (for HFEM) and MHD (for CM) after 6 months. |

Changes in NRS, MAI, HIT-6 and MIDAS scores, ≥50% RR, conversion rate from CM to EM and MO discontinuation. |

Primary endpoints: MMD - 8 (p< 0.001). MHD: -13 (p < 0.001). Secondary endpoints: NRS: - 2 in EM and – 2 in CM;( p< 0.001). HIT-6: - 14 in EM and -13 in CM (all p< 0.001); MIDAS: - 27 in EM and -54 in CM (p < .001). MAI: -8 in EM; -15 in CM (both p <0.001) ≥50%RRs: 76.5% in HFEM and 63.5% in CM. CM -→ EM: 77.2%. MO discontinuation: 82.0%. |

AE: 10.3% non-serious events. |

| Vernieri et al, 2022 [48] |

CM:156 |

12 weeks |

P M (n=14) N= Italy |

Consecutive 3-month ≥50% MHD RR. |

Persistence of conversion from MO to non-MO and from CM to EM in all 3 months of treatment. Change in MHDs, MIDAS, HIT-6, MAI. |

Primary endpoint: persistent ≥50% MHD RR: 41.7% Secondary endpoints: CM→ EM: 55.8%. Conversion from MO to non-MO: 61.8% of patients. MHD: -15 (p <0.001); MIDAS: -43 (p <0.001); HIT-6: -11 (p <0.001); NRS: -2 (p <0.001) MAI: -13 (p <0.001). |

NA |

| Altamura et al, 2022 [49] |

CM: 161 |

52 weeks |

P M (n=15) N= Italy |

Conversion rate from CM to EM from baseline to 12 months. |

MO discontinuation, changes in MAI and monthly NRS. |

Primary endpoint: CM →EM: 52.3%. Secondary endpoints: MO discontinuation rate: 82.8%. MAI: -17 (p < 0.000001). NRS: -2 (p < 0.000001). |

|

| Fofi et al, 2022 [50] |

27 (EM/CM: 14/13) |

24 weeks |

P S N= Italy |

Change in MMD, NRS, MAI, HIT-6 MIDAS and reduction in RSS and improvement in MS after 6 months of treatment. |

MMD: -10.2 (p < 0.001); NRS: -2.4 (p < 0.001); MAI: -14.3 (p < 0.001); HIT-6: -14.6 (p < 0.001); MIDAS: -68.4 (p < 0.001); RSS: - 7 (p = 0.027); MS: + 0.29 (p = 0.014). |

NA | |

| Silvestro et al, 2022 [51] |

43 (EM/CM: 8/35) |

24 weeks |

P S N= Italy |

Change in MHD, NRS, attack duration and whole pain burden score after 3 and 6 months of treatment. | ≥50% ≥75% RR; ≥50% reduction of whole pain burden core. change in MIDAS, HIT-6, MAI MSQ, BDI-II, HDRS scores. Proportion of patients converting from CM to EM and from non-responders to responders to pain killers. |

Primary endpoints: MHD: -13.1 (T3) and -14.2 (T6) (p < 0.001);NRS: -2.1 score (T3) and -2.7 (T6) (p < 0.001);Headache attack duration (treated): -5.3 hours (T3) and -6.7 hours (T6) (p < 0.001). Whole total pain burden score: -1498 (T3); -1591.3 (T6) (p < 0.001). Secondary endpoints: ≥50% RR: 72.1% (T3), 74.4% (T6). ≥75% RR:44.2% (T3), 55.8% (T6). Reduction of 50% and 75% of the whole total pain burden score: 88.4% (T3), 95.4% (T6) and 76.7% (T3) and 88.4% (T6). MIDAS: -70 (T3) -74.5 (T6) (p < 0.001) HIT-6: -11 (T3); -11.5 (T 6) (p < 0.001) MAI: -15.5 at moths 6 (p < 0.001). MSQ: - 45,71 (T3); -47.14 (T6) (p < 0.001) BDI-II: -5.5 (T3); -5.5 (T6) (p = 0.003) HDRS: -5 (T3); -5 (T6). (p < 0.001). CM -→ EM: 74.3% |

Injection site reaction: 23.26%, constipation:16.27%, fatigue: 6.98%, acrocianosys: 2.32%. |

| Kwon et al, 2022 [52] |

87 (EM/CM:22/65) |

12 weeks |

P S N= Korea |

>50% RR at 3 months. |

>30%, >75%, and 100% RR, MHD, moderate/severe headache days, MAI, CCD, and HIT-6 and MIDAS scores. |

Primary endpoint: >50% RR: 44.8% (54.5% EM and 41.5% CM). Secondary endpoints: >30% RR: EM 59.1%, CM 55.4%; >75% RR: EM 27.3%, CM 27.7%; 100% RR: EM 22.7%, CM 10.8%. MHD: -7.2 (p<0.001). Moderate/severe headache days: -4.3 (p<0.001); MAI: -4.1 (p<0.001); CCD: +7.3 (p<0.001); HIT-6: -4.4 (p<0.001); MIDAS: -32.9 (p<0.001). |

Constipation 16.3%, fatigue 7%, acrocyanosis 2.3% |

| Ashina et al, 2023 [53] |

46 (EM/CM: 27/19) |

12 weeks |

P S N= USA |

Effects on premonitory symptoms, and/or occurrence of headache afterexposure to triggers or aura episodes in treatment-responders (≥ 50%), super-responders (≥ 70%), non-responders (< 50%) and super nonresponders(< 30%). |

Premonitory symptoms decreased by 48% in responders, 28% in non-responders, 50% in super responders, and 12% in super non-responders. Triggers followed by headache decreased by 38% in responders, 13% in non-responders, 31% in super-responders, 4% in super non-responders. |

NA | |

| Guerzoni et al, 2023 [54] |

78 CM |

64 weeks |

P S N= Italy |

Change in MMD, MAI after 1 year. |

Change in NRS, HIT-6, MIDAS |

Primary endpoints: MHD: - 11.5 (p < 0.001); MAI- 30.1 (p < 0.001). Secondary endpoints: NRS: −2.8; HIT-6: -58.4 MIDAS -19.5 (p < 0.001). |

NA |

| Vernieri et al, 2023 [7] |

191 (EM/CM:43/148) |

52 weeks |

P M (n=16) N= Italy |

Change in MMD /MHD. | Changes in MAI, NRS MIDAS, HIT-6. >50%, >75%, and 100% RR. |

Primary endpoints: MMD: -6.0; MHD: -11.9. (all p < 0.00001) Persistent ≥50% RR: 56.5%. Persistent responders have a higher body mass index (BMI) (p = 0.007), a good response to triptans (p = 0.005) and MMD ≥50% RR at V1 (p < 0.0000001). Secondary endpoints: EM: MAI – 9; NRS: -2; HIT-6 -12.3; MIDAS -37,6. (p < 0.00001). >50%, >75%, and 100% RR /3.8%, 37.2%, 2.3%. CM: MAI: -18.4, NRS: -1.9; in HIT-6 :– 13.7; MIDAS – 57.6. (p < 0.00001). >30%, >75%, and 100% RR. >50%, >75%, and 100% RR 60.5%, 38.1%, 3.4%. |

Two pts dropped out for nonserious AEs. |

| Suzuki et al, 2023 [55] |

55 (EM/CM:18/37) | 12 weeks | R S N= Japan |

Change in MMD; A ≥ 50% RR at month 1,2 and 3. WMDs during month 1. |

MMD: − 6.2 at 1 month (p < 0.001), − 6.8 at 2 months (p < 0.001), and − 7.9 at 3 months (p < 0.001). The ≥ 50% RR: 40.0% at 1 month, 41.8% at 2 months, and 50.9% at 3 months. The ≥ 75% RR: 10.9% at 1 month, 14.5% at 2 months, and 27.3% at 3 months. WMDs week 1: - 1.6; week 2: - 1.2, week 3: - 1.0; week 4: - 1.1 (p < 0.001). |

NA | |

| Lee et al, 2023 [56] | 238 CM |

12 weeks |

P S N= Korea |

Change in MHD, a ≥ 50%, ≥ 75%, ≥ 100% RR at month 3. Comparison of migraine charcteristics, comorbidities, and treatment responses between responder and non-responder groups. |

MHD: - 12.7. ≥ 50% RR: 64.3%. ≥ 75% RR: 35.3%. ≥ 100% RR: 3.4%. Responder group features: younger, lower frequency of baseline headache days, more accompanying symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and photophobia, better triptan response, less depression. Everyday headache (p = 0.017), depression (p = 0.024) and absence of accompanying symptoms (p=0.020) were significantly associated with response. |

NA | |

| Schiano di Cola et al, 2023 [57] |

54 (EM/CM:17/37) | 24 weeks | R S N= Italy |

Change in MHD, MMD, NRS, MAI, MIDAS, and HIT-6 at T0, T3 and T6. |

MHD -11.2 at T3 and - 11 at T6 (p < 0.001). MMD: - 8.2 at T3 and -7.5 at T6; (p < 0.001). NRS: – 1.6 at T3 and – 1.7 at T6 (p = 0.001). MAI -17.6 at T3 and -17.1 atT6 (p < 0.001). MIDAS: - 71.8 at T3 and – 77.5 at T6 (all p < 0.001). HIT-6: - 9.3 at 3 M and -11.1 at 6 M (all p < 0.001). MIDAS: −74.3% at T3, −80.6% at T6. HIT-6: -24.3% and 29.2% at T3 a T6, respectively. |

NA | |

| Schiano di Cola et al, 2023 [58] |

47 (EM/CM:17/30) |

24 weeks | P S N= Italy |

Change in MHD, MMD, NRS, MAI, MIDAS, and HIT-6 scores at T3, and T6. |

To evaluate photophobia, photophobia at T3 and T6. |

Primary endpoints: MHD T3: -10.6; T6: -11.5 (p < 0.0001). MMD T3: -7.5; T6: -6.6 (p < 0.0001). NRS: - 1.4 both T3 and T6 (p < 0.0001) MAI: -17.5 at T3 and T6. (p < 0.0001). MIDAS T3: -60.5; T6: -64 (p < 0.0001). HIT-6 T3: -9; T6: -9.6 (p < 0.0001). Secondary endpoint: improvement in ictal photophobia: 68.1% more frequent in patients with episodic migraine (p = 0.02) and triptans responders (p = 0.03). |

NA |

| Kim et al, 2023 [59] |

104 (EM/CM: 24/80) |

12 weeks | R S N= Korea |

The ≥ 50% RR in the 3rd month of treatment vs baseline. | The ≥ 50% RR: 55.7%. |

NA |

- c)

- RWE studies examining multiple monoclonal antibodies.

| Author/ Year/Country |

N° pts | Observation period | Study Type/Center/ National-International |

Primary endpoint | Secondary endpoint | Results | Safety findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caronna et al, 2021 [8] |

CM: 139 Erenumab: 96, Galcanezumab: 43 |

24 weeks | P S N= Italy |

Change in MHD in MO e non-MO patients at monts 6; ≥50% RR at monts 6. | To compare pts with and w/o MO resolution at 6 months. |

Primary endpoint: MHD MO: − 13.4 (p < 0.0001) MHD non-MO: -7.8 (p < 0.0001) ≥50% RR MO: 63.6% ≥50% RR non- MO: 57.5% Secondary endpoint: pts with ongoing MO at 6 months: higher frequency of MDM (p = 0.020), higher score in a 0–3 pain severity scale (p = 0.020), higer MAI p = 0.049), benzodiazepine use (p = 0.034), more anxiety in BAI (p = 0.020); previous failure to onabotulinumtoxinA (p = 0.048). |

NA |

| Vernieri et al, 2021 [9] |

154 Erenumab: 91, Galcanezumab: 63 (EM/CM: 47/107) |

52 weeks 8-weeks follow-up after treatment completion |

P M N= Italy |

Change in MMD in the three months following erenumab and galcanezumab discontinuation (F-UP 1–2-3) after one year of treatment vs baseline. | Changes in MAI, in NRS, and HIT-6 score in F-UP 1–2-3. |

Primary endpoint: MMD F-UP 1 EM/CM: - 2/- 5.5 MMD F-UP 2: EM/CM: -0.5/ -4 MMD F-UP 3: EM/CM: -0.5/-4 Secondary endpoints: MAI at F-UP 1 EM/CM: -6/-13 MAI at F-UP 2: EM/CM: -3/-9 MAI at F-UP 3: EM/CM: -2/-6 NRS at F-UP 1 EM/CM: -1.5/-1 NRS at F-UP 2: EM/CM: -1.5/-1 NRS at F-UP 3: EM/CM: -0.5/0 HIT-6 at F-UP 1 EM/CM: -10-5/-7 HIT-6 at F-UP 2: EM/CM: -4/-5 HIT-6 at F-UP 3: EM/CM: -6/-4 |

NA |

| Raffaelli et al, 2022 [10] |

39 Erenumab: 16, Galcanezuma: 15, Fremanezumab: 8 (HFEM/CM: 14/25) |

60 weeks | P S N=Germany |

Change in MMD between the last four weeks of treatment discontinuation and weeks 9–12 after restart. | Changes in MHD, MAI, and HIT-6 scores in the same observation period. |

Primary endpoint: MMD: -4.5 (p<0.001). Secondary endpoint: MHD -5.4 (p< 0.001) MAI: -3.9 HIT-6: -6 (p<0.001). |

NA |

| Iannone et al, 2022 [11] |

CM:203 Erenumab: 96 Galcanezumab : 74Fremanezumab: 33 |

52 weeks | P S N= Italy |

Change in MMD; the ≥ 50%, ≥ 75% and 100% RR in MMD at 12 months. The ≥ 50% reduction in MIDAS score at 12 months. |

Clinical predictors of response at 6 months and 12 months. |

Primary endopoint: MMD: -8.4 (p< 0.0001) ≥ 50% RR: 36.4% ≥ 75% RR: 15.4% 100% RR: not achived. Reduction ≥ 50% in MIDAS: from 63.5% to 96.1%. Secondary endpoint: association with lower RR at 1 month: duration of chronicization (p = 0.04); elevated number of MMD at baseline (p < 0.0001); association with lower RR at 6 months: duration of chronicization (P = 0.04); MMD at baseline (p < 0.0001); Total Number of Analgesics (p = 0.003). |

NA |

| Nowaczewska et al, 2022 [12] | 123 Erenumab: 75, Fremanezumab: 48 (HFEM/CM:36/87) |

12 weeks | R S N=Poland |

Check if baseline clinical parameters and cerebral blood flow (CBF) measured by transcranial Doppler (TCD) may help predict mAbs efficacy | NA | Baseline Vm (mean velocity) values in middle cerebral artery were significantly lower in good responders vs non-responders. MAbs responsiveness ≥50% was positively associated with unilateral pain localization (p = 0.003) and HIT-6 score (p = 0.036) whereas negatively associated with Vm in right MCA (p = 0.012), and having no relatives with migraine (p = 0.040). | NA |

| Quintana et al, 2022 [13] | 123 (56 Erenumab: 56, Galcanezumab: 38, Fremanezumab: 29 (HFEM/CM:66/57) |

24 weeks | R S N=Italy |

Reduction in MDM and MAI at 3 and 6 months | Change in HIT-6, MIDAS and Headwork |

Primary endpoint: at 3 month Fremanezumab was statistically superior to Erenumab (MMD -16.7 vs -12.9, p<0.02). Secondary endpoint: Erenumab determined a greater improvement in the Headwork vs Fremanezumab (-14.7 vs -8.2, p<0.01) |

NA |

| Barbanti et al, 2022 [14] | 864 Erenumab: 639, Galcanezumab: 173, Fremanezumab: 52. (HFEM/CM: 208/565) |

≥ 24 weeks N=Italy |

P M (n=20) N=Italy |

≥ 50% response predictors at 24 weeks | ≥ 75% and 100% response predictors at 24 weeks. |

Primary endpoint: ≥50% response in HFEM positively associated UP + UAs (p=0.004) and in CM with UAs (p=0.0264), UP + UAs (p=0.012), UP + allodynia (p=0.034) Secondary endpoint: 75% response positively associated with UP + UAs (p=0.006) in HFEM and with UP + UAs (p=0.012) and UP + allodynia (p=0.005) in CM |

30% of Erenumab and Fremanezumab patients reported TEAEs (pain and redness at the injection site, constipation) |

| Varnado et al, 2022 [15] |

3082 CGRP mAb versus SOC and 421 Galcanezumab versus SOC EM/CM 1749/ 1333 |

52 weeks | R S N= USA |

To compare real-world treatment patterns for CGRP mAb, specifically galcanezumab versus standard-of-care (SOC) migraine preventive treatments. | Pts stopping SOC:75%. Compared with SOC, the CGRP mAb cohort had higher mean persistence (212.5 vs 131.9 days), adherence (PDC: 55.1% vs 35.2%), and more patients were adherent with PDC ≥80% (32.7% vs 18.7%) (all p <0.001). During 12-month follow-up, fewer patients discontinued CGRP mAb versus SOC (58.8% vs 77.6%, p <0.001). |

NA | |

| Katsuki et al, 2023 [16] |

8 CM Fremanezumab: 5; Galcanezumab: 3 | 12 weeks | R S N= Japan |

Median of MHD, MAI HIT-6 at 3 months. | Median MHD before, one, and three months: 30, 4 and 1 respectively. Median MAI: 17.5, 1.5, and 0 respectively) Median for HIT-6: 60.5, 45.5, and 44 respectively. |

NA | |

| Cantarelli et al, 2023 [17] | 104 CM Erenumab: 48, Galcanezumab: 43, Fremanezumab: 13 |

24 weeks | R S N=Spain |

Change in MHD, MIDAS and HIT-6 at weeks 0, 12, and 24 of treatment (at least 50%) | Treatment efficacy: young versus older patients, previous failure to >5 versus <5 drugs |

Primary endpoint: reduction form erenumab, galcanezumab and fremanezumab in MHD, MIDAS and HIT-6 at week 12 (p<0.001); MHD at week 24 from Erenumab and Galcanezumab (p <0.001); MIDAS and HIT-6 in the erenumab group (P < 0.001, P = 0.004) and MIDAS in the galcanezumab group (P < 0.001). Secondary endpoints: reduction in MHD >50% at week 12 (P = 0.044) was observed between patients with >5 prior treatment failures with fremanezumab and in MHD >75% at week 24 with galcanezumab (p = 0.038) |

NA |

| Muñoz-Vendrell et al, 2023 [18] | 162 Erenumab: 38, Galcanezumab: 85, Fremanezumab: 29 (HFEM/CM: 32/130) |

24 weeks | P M (n=18) N=Spain |

Change in MMD at 6 months of treatment and the presence of AEs | Change in MMD at 3 months, change in MHD, MAI, frequency of days by intensity, the 30%, 50%, 75% and 100% RR, HIT-6, MIDAS and PGIC at 3 and 6 months. |

Primary endpoint: MMD: -10.1 (p=0.0001). Secondary endpoint: MMD: -9.7; MHD: -10.1, -10.5; MAI: -8.8, -9.4 (p<0.001). ≥30%,≥50%,≥75% and 100% RR: 68%, 57%, 33% and 9%. |

Injection pain, rash or pruritus: 26 pts, flu-like symptoms: 8 pts, hair loss : 2 pts. |

| Guerzoni et al, 2023 [19] | 233 Erenumab, Galcanezumab, Fremanezumab (HFEM/CM:40/193) |

48 weeks | P S N=Italy |

Response to anti-CGRP mAbs between women in menopause and those of childbearing age. | Effectiveness of anti-CGRP mAbs between woman with physiological menopause and those with a surgical one and effectiveness different antibodies and the predictors of a 75% response among women in menopause |

Primary endpoint: the effectiveness of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies is almost the same between women in menopause and women of childbearing age. Secondary endpoint: no predictors of an excellent response apart from a lower AC at the baseline (p= 0.03) |

Constipation: erenumab 54.5% for galcanezumab: 40.9%; fremanezumab, 4.5%. Injection site reaction only in 7 pts with galcanezumab. |

| Barbanti et al, 2023 [20] |

771 Erenumab: 527, Fremanezumab: 40, Galcanezumab:5 (HFEM/CM:154/418) |

≥24 weeks | P M (n=16) N=Italy |

Frequency and characteristics of late responders (>12 weeks) | Late responders: 55.1%. Differed from responders: higher BMI (+0.78, p= 0.024), more frequent treatment failures (+0.52, p= 0.017) and psychiatric comorbidities (+10.1%, p = 0.041), and less common unilateral pain, alone (−10,9%, p = 0.025) or in combination with UAs (−12.3%, p = 0.006) or allodynia (−10.7, p = 0.01). | AEs: 23% constipation (4.4%), fatigue (4.4%) and dizziness (3.3%). | |

| Vernieri et al, 2023 [21] | 226 Erenumab: 125, Galcanezumab, Fremanezumab: 101 (HFEM/CM:46/180) |

64 weeks | P M (n=10) N=Italy |

MMD, MAI, and HIT-6 at baseline, after 90-112 days (Rev-1), after 84-90 days since Rev-1 (Rev-2) and 30 days after the last injection, in the first and the second year after a discontinuation period | MMD (18.1 ± 7.8 vs. 3.4±7.8), MAI (26.7± 28.3 vs.17.7 ±17.2), and HIT-6 scores (63.1 ± 5.9 vs. 67.1 ± 10.3) were lower in the second year than in the pre-treatment baseline (consistently, p<0.0001). Second-year baseline MMD were lower in patients on anti-CGRP mAbs (p = 0.001) and with lower pre-treatment baseline MMD (p ≤ 0.001). | NA |

| 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | EM | CM | All | EM | CM | All | EM | CM | |

| MMD | - | -2.5/-4.5 | - | -4.8/-7.7 | - | - | -4.3/-7.8 | - | |

| - | -4.4 | - | - | -7.5 -8.2 | - | - | -6/-11.5 | ||

| -4.6/-7.3 | - | -6.9, -7.7 | - | -6.4/-6.5 | - | ||||

| MHD | -6.9/-7.9 | - | - 4.7/-15 | -4 | - | -6.8/-19 | - | - | -12.8/-21.7 |

| - | - | -7.3/-15 | -10.2/-14.2 | - | -11/-14.9 | - | - | -10/-11.9 | |

| ù | -8.2/-9.4 | - | -9.7/-14.2 | - | -14.5/-15 | ||||

| NRS | - | -0.5/-1.9 | -1.7/-3 | -0.7/-2 | -2/-3 | - | -0.7/-3 | -1.8/-3.6 | |

| -1.6/-2.1 | -1/-2 | -1 | -1.4/-2-7 | -2 | -2 | - | -2 | -1.9/-2.8 | |

| -3.1 | -2.5 | -3.4 | -2.7 | -3.4 | -3.4 | ||||

| MAI | -6.5/-7.6 | -5/-7 | -12/-15 | -1.7 | -5/-8 | -14/-15 | - | -5/-8 | -14/-16 |

| -4.1 | -4/-6.5 | -4/-15 | -14.2/-17.5 | -8 | -8/-29.7 | - | -9 | -18.4/-30.1 | |

| -5.7 | -11.1 | -8 | -15.1 | -6/-7 | -15.5/-16.5 | ||||

| MIDAS | - | -28.5/-48.9 | -35.1/-42.1 | -32.4/-44.6 | -37.1/-45.9 | - | -38.3/-47 | -44.3/-65.1 | |

| -32.9 | - | -14/-71.8 | -64/-77.5 | -27 | -54 | - | -9.3 | 19.5/-57.6 | |

| -31/-53.8 | -43.7/-55 | -55 | -72.6 | -18/-50.4 | -53.5/-76.6 | ||||

| HIT-6 | -7/-8.4 | -8.4/-10.7 | -9.7/-11.4 | -7.1/-13.3 | -7.5/-12.7 | - | -12.3/-13.7 | -13.1/-14 | |

| -4.4 | -4 | -11 | -9.3/-14.6 | -63 | -50 | - | -12.3 | -13.7/-58.4 | |

| -10/-18.1 | -0.3/-28 | -20.9 | -24.3 | - | -16.9/-18.5 | -15/-17.9 | |||

|

>50% RR (%) |

41.9/53.3 | 57.7/59.4 | 41.9/55.5 | - | 36/63 | 22/70 | - | 56/85 | 44.5/68 |

| 50.9 | 41.7/76 | 48.1/76.5 | 73.2/95.4 | 76.7 | 61.5/74.4 | - | 73.8 | 60.5 | |

| 43.3/76.5 | 38.3/58.3 | 75/90.4* | 52.2/76.3 | 75.5/78.6 | 71.6/75.9 | ||||

|

>75% RR (%) |

20.2/20.7 | 16.8/22.9 | 20/22.4 | - | 16.3/38.4 | 38/42.3 | - | 31.6/42 | 31.6/44.5 |

| 27.3 | 41.7/73.8 | 27.7/44.2 | 45.7/55.8 | 30.2 | 63.5 | - | 37.2 | 38.1 | |

| 24/40.2 | 17/25 | 30.8/36.5 | 14.9/44.8* | 35.7/36.7 | 44.4/37 | ||||

|

100% RR (%) |

- | 1/3 | 1.1/5 | 4.6 | 2.8-9 | - | 8.8 | 1.2/ 8.5 | |

| - | 7/20 | 3.4/10.8 | - | 9.3/11.6 | 4.7 | - | 2.3 | 3.4 | |

| 9.9 | 0 | 9.6 | 1/1.5 | 2/14.3 | 3.7/5.6 | ||||

| AE type |

Frequency range |

Frequency <8% (pts n) | Frequency 8-10% (pts n) |

Frequency >10% (pts n) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pts with AEs- | 7.8%-93% |

- constipation | 8.8%-65% | - | 1 | 4 |

| - injection site erythema | 0.8%-27% | 1 | - | 2 | ||

| - fatigue | 0.8%-43% | 1 | - | 2 | ||

| - insomnia | 5.7%-9.5% | - | 1 | - | ||

| - cold/flu-like | 5%-15% | - | - | 1 | ||

| - dizziness | 0.6-1.8 | 1 | - | - | ||

| -arthralgia | 1.1-1.7 | 2 | - | - | ||

| Pts with SAEs | 0-1.2% | - paralytic ileus - constipation - myocardial infarction |

0.4% 0.8% 0.8% |

|||

| Pts who discontinued treatment due to AEs | 0-1.2% | - paralytic ileus - constipation - myocardial infarction |

0.4% 0.8% 0.8% |

| AE type |

Frequency range |

Frequency <8% (pts n) | Frequency 8-10% (pts n) |

Frequency >10% (pts n) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pts with AEs | 0%- 26.9% | - injection site reactions | 1.1-12.7% | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| - constipation | 0.7-7.2% | 7 | - | - | ||

| - dizzines | 1.9-4% | 2 | - | - | ||

| - flu-like simptoms | 3.9-4-% | 2 | - | - | ||

| - fatigue | 0.4-3% | 2 | - | - | ||

| - arthralgia | 0-2% | 1 | - | - | ||

| - nausea | 0.2-2% | 2 | - | - | ||

| - abdominal pain | 0-1.9% | 1 | - | - | ||

| - hair loss | 0.2-1% | 2 | - | - | ||

| - libido loss | 0-0.2% | 1 | - | - | ||

| Pts with SAEs | 0% | - | ||||

| Pts who discontinued treatment due to AEs | 0-1.2% | - injection site reactions |

| AE type |

Frequency range |

Frequency <8% (pts n) | Frequency 8-10% (pts n) |

Frequency >10% (pts n) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pts with AEs | 0%- 26.9% | - injection site reaction | 1%/26.9% | 1 | - | 2 |

| - constipation | 1.1%/16.3% | 2 | - | 2 | ||

| - dizziness | <2%/8% | 1 | 1 | - | ||

| - flu-like simptoms | 0%/<2% | 2 | - | - | ||

| - fatigue | 5.8%/7% | 3 | - | - | ||

| - arthralgia | 0%/2.3% | 2 | - | - | ||

| - acrocyanosis | 0%/2.3% | 2 | - | - | ||

| Pts with SAEs | 0% | - | ||||

| Pts who discontinued treatment due to AEs | 0 | - |

| AE type |

Frequency range |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pts with AEs | 0%- 54.5% | - injection site reaction | 0%- 30% |

| - constipation | 0%- 54.5% | ||

| - dizziness | 0%-3.3% | ||

| - fatigue | 0%-4% | ||

| Pts with SAEs | 0% | ||

| Pts who discontinued treatment due to AEs | 0% |

Discussion

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- F. Haghdoost, F. Puledda, D. Garcia-Azorin, E.-M. Huessler, R. Messina, e P. Pozo-Rosich, «Evaluating the efficacy of CGRP mAbs and gepants for the preventive treatment of migraine: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of phase 3 randomised controlled trials», Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache, vol. 43, fasc. 4, p. 3331024231159366, apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Serra López-Matencio et al., «Treatment of migraine with monoclonal antibodies», Expert Opin. Biol. Ther., vol. 22, fasc. 6, pp. 707–716, giu. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Blonde, K. Khunti, S. B. Harris, C. Meizinger, e N. S. Skolnik, «Interpretation and Impact of Real-World Clinical Data for the Practicing Clinician», Adv. Ther., vol. 35, fasc. 11, pp. 1763–1774, 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Barbanti et al., «Long-term (48 weeks) effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of erenumab in the prevention of high-frequency episodic and chronic migraine in a real world: Results of the EARLY 2 study», Headache, vol. 61, fasc. 9, pp. 1351–1363, ott. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Barbanti et al., «Predictors of response to anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies: a 24-week, multicenter, prospective study on 864 migraine patients», J. Headache Pain, vol. 23, fasc. 1, p. 138, nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Barbanti et al., «Assessing the Long-Term (48-Week) Effectiveness, Safety, and Tolerability of Fremanezumab in Migraine in Real Life: Insights from the Multicenter, Prospective, FRIEND3 Study», Neurol. Ther., mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Vernieri et al., «Maintenance of response and predictive factors of 1-year GalcanezumAb treatment in real-life migraine patients in Italy: The multicenter prospective cohort GARLIT study», Eur. J. Neurol., vol. 30, fasc. 1, pp. 224–234, gen. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Caronna, V. J. Gallardo, A. Alpuente, M. Torres-Ferrus, e P. Pozo-Rosich, «Anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in chronic migraine with medication overuse: real-life effectiveness and predictors of response at 6 months», J. Headache Pain, vol. 22, fasc. 1, p. 120, ott. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Vernieri et al., «Discontinuing monoclonal antibodies targeting CGRP pathway after one-year treatment: an observational longitudinal cohort study», J. Headache Pain, vol. 22, fasc. 1, p. 154, dic. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Raffaelli et al., «Resumption of migraine preventive treatment with CGRP(-receptor) antibodies after a 3-month drug holiday: a real-world experience», J. Headache Pain, vol. 23, fasc. 1, p. 40, mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. F. Iannone, D. Fattori, S. Benemei, A. Chiarugi, P. Geppetti, e F. De Cesaris, «Long-Term Effectiveness of Three Anti-CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies in Resistant Chronic Migraine Patients Based on the MIDAS score», CNS Drugs, vol. 36, fasc. 2, pp. 191–202, feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Nowaczewska, M. Straburzyński, M. Waliszewska-Prosół, G. Meder, J. Janiak-Kiszka, e W. Kaźmierczak, «Cerebral Blood Flow and Other Predictors of Responsiveness to Erenumab and Fremanezumab in Migraine—A Real-Life Study», Front. Neurol., vol. 13, mag. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Quintana, M. Russo, G. C. Manzoni, e P. Torelli, «Comparison study between erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab in the preventive treatment of high frequency episodic migraine and chronic migraine», Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol., vol. 43, fasc. 9, pp. 5757–5758, set. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Barbanti et al., «Late Response to Anti-CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies in Migraine: A Multicenter Prospective Observational Study», Neurology, vol. 101, fasc. 11, pp. 482–488, set. 2023. [CrossRef]

- O. J. Varnado, J. Manjelievskaia, W. Ye, A. Perry, K. Schuh, e R. Wenzel, «Treatment Patterns for Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Monoclonal Antibodies Including Galcanezumab versus Conventional Preventive Treatments for Migraine: A Retrospective US Claims Study», Patient Prefer. Adherence, vol. 16, pp. 821–839, mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Katsuki, K. Kashiwagi, S. Kawamura, S. Tachikawa, e A. Koh, «One-Time Use of Galcanezumab or Fremanezumab for Migraine Prevention», Cureus, vol. 15, fasc. 1, p. e34180, gen. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Cantarelli et al., «Efficacy and Safety of Erenumab, Galcanezumab, and Fremanezumab in the Treatment of Drug-Resistant Chronic Migraine: Experience in Real Clinical Practice», Ann. Pharmacother., vol. 57, fasc. 4, pp. 416–424, apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Muñoz-Vendrell et al., «Effectiveness and safety of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in patients over 65 years: a real-life multicentre analysis of 162 patients», J. Headache Pain, vol. 24, fasc. 1, p. 63, giu. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Guerzoni, F. L. Castro, D. Brovia, C. Baraldi, e L. Pani, «Evaluation of the risk of hypertension in patients treated with anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in a real-life study», Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol., vol. 45, fasc. 4, pp. 1661–1668, apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Barbanti et al., «Ultra-late response (> 24 weeks) to anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in migraine: a multicenter, prospective, observational study», J. Neurol., vol. 271, fasc. 5, pp. 2434–2443, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Vernieri et al., «Retreating migraine patients in the second year with monoclonal antibodies anti-CGRP pathway: the multicenter prospective cohort RE-DO study», J. Neurol., vol. 270, fasc. 11, pp. 5436–5448, nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Barbanti, C. Aurilia, G. Egeo, e L. Fofi, «Erenumab: from scientific evidence to clinical practice-the first Italian real-life data», Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol., vol. 40, fasc. Suppl 1, pp. 177–179, mag. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Barbanti et al., «Erenumab in the prevention of high-frequency episodic and chronic migraine: Erenumab in Real Life in Italy (EARLY), the first Italian multicenter, prospective real-life study», Headache J. Head Face Pain, vol. 61, fasc. 2, pp. 363–372, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Scheffler et al., «Erenumab in highly therapy-refractory migraine patients: First German real-world evidence», J. Headache Pain, vol. 21, fasc. 1, p. 84, lug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Ornello et al., «Real-life data on the efficacy and safety of erenumab in the Abruzzo region, central Italy», J. Headache Pain, vol. 21, fasc. 1, p. 32, apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Russo et al., «Multidimensional assessment of the effects of erenumab in chronic migraine patients with previous unsuccessful preventive treatments: a comprehensive real-world experience», J. Headache Pain, vol. 21, fasc. 1, p. 69, giu. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Lambru, B. Hill, M. Murphy, I. Tylova, e A. P. Andreou, «A prospective real-world analysis of erenumab in refractory chronic migraine», J. Headache Pain, vol. 21, fasc. 1, p. 61, giu. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Ornello et al., «Gender Differences in 3-Month Outcomes of Erenumab Treatment-Study on Efficacy and Safety of Treatment With Erenumab in Men», Front. Neurol., vol. 12, p. 774341, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. de Vries Lentsch, I. E. Verhagen, T. C. van den Hoek, A. MaassenVanDenBrink, e G. M. Terwindt, «Treatment with the monoclonal calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antibody erenumab: A real-life study», Eur. J. Neurol., vol. 28, fasc. 12, pp. 4194–4203, dic. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. De Matteis et al., «Early outcomes of migraine after erenumab discontinuation: data from a real-life setting», Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol., vol. 42, fasc. 8, pp. 3297–3303, ago. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Andreou et al., «Two-year effectiveness of erenumab in resistant chronic migraine: a prospective real-world analysis», J. Headache Pain, vol. 23, fasc. 1, p. 139, nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- U. Pensato et al., «Erenumab efficacy in highly resistant chronic migraine: a real-life study», Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol., vol. 41, fasc. Suppl 2, pp. 457–459, dic. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Ornello et al., «Comparing the relative and absolute effect of erenumab: is a 50% response enough? Results from the ESTEEMen study», J. Headache Pain, vol. 23, fasc. 1, p. 38, mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A.R. Gantenbein et al., «Swiss QUality of life and healthcare impact Assessment in a Real-world Erenumab treated migraine population (SQUARE study): interim results», J. Headache Pain, vol. 23, fasc. 1, p. 142, nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Cetta, R. Messina, L. Zanandrea, B. Colombo, e M. Filippi, «Comparison of efficacy and safety of erenumab between over and under 65-year-old refractory migraine patients: a pivotal study», Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol., vol. 43, fasc. 9, pp. 5769–5771, set. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Troy et al., «Medium-term real-world data for erenumab in 177 treatment resistant or difficult to treat chronic migraine patients: persistence and patient reported outcome measures after 17-30 months», J. Headache Pain, vol. 24, fasc. 1, p. 5, gen. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Pilati et al., «Erenumab and Possible CGRP Effect on Chronotype in Chronic Migraine: A Real-Life Study of 12 Months Treatment», J. Clin. Med., vol. 12, fasc. 10, p. 3585, mag. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Buture et al., «Two-year, real-world erenumab persistence and quality of life data in 82 pooled patients with abrupt onset, unremitting, treatment refractory headache and a migraine phenotype: New daily persistent headache or persistent post-traumatic headache in the majority of cases», Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache, vol. 43, fasc. 6, p. 3331024231182126, giu. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Barbanti et al., «Fremanezumab in the prevention of high-frequency episodic and chronic migraine: a 12-week, multicenter, real-life, cohort study (the FRIEND study)», J. Headache Pain, vol. 23, fasc. 1, p. 46, apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Driessen et al., «Real-world effectiveness after initiating fremanezumab treatment in US patients with episodic and chronic migraine or difficult-to-treat migraine», J. Headache Pain, vol. 23, fasc. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Barbanti et al., «Early and sustained efficacy of fremanezumab over 24-weeks in migraine patients with multiple preventive treatment failures: the multicenter, prospective, real-life FRIEND2 study», J. Headache Pain, vol. 24, fasc. 1, p. 30, mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Argyriou et al., «Efficacy and safety of fremanezumab for migraine prophylaxis in patients with at least three previous preventive failures: Prospective, multicenter, real-world data from a Greek registry», Eur. J. Neurol., vol. 30, fasc. 5, pp. 1435–1442, mag. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. K. Cullum, B. A. Chaudhry, T. P. Do, e F. M. Amin, «Real-world efficacy and tolerability of fremanezumab in adults with chronic migraine: a 3-month, single-center, prospective, observational study», Front. Neurol., vol. 14, p. 1226591, ago. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Suzuki, K. Suzuki, T. Shiina, Y. Haruyama, e K. Hirata, «Real-world experience with monthly and quarterly dosing of fremanezumab for the treatment of patients with migraine in Japan», Front. Neurol., vol. 14, p. 1220285, 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Caponnetto et al., «Long-Term Treatment Over 52 Weeks with Monthly Fremanezumab in Drug-Resistant Migraine: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study», CNS Drugs, vol. 37, fasc. 12, pp. 1069–1080, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Takizawa et al., «Real-world evidence of galcanezumab for migraine treatment in Japan: a retrospective analysis», BMC Neurol., vol. 22, fasc. 1, p. 512, dic. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Vernieri et al., «Rapid response to galcanezumab and predictive factors in chronic migraine patients: A 3-month observational, longitudinal, cohort, multicenter, Italian real-life study», Eur. J. Neurol., vol. 29, fasc. 4, pp. 1198–1208, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Vernieri et al., «Galcanezumab for the prevention of high frequency episodic and chronic migraine in real life in Italy: a multicenter prospective cohort study (the GARLIT study)», J. Headache Pain, vol. 22, fasc. 1, p. 35, mag. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Altamura et al., «Conversion from chronic to episodic migraine in patients treated with galcanezumab in real life in Italy: the 12-month observational, longitudinal, cohort multicenter GARLIT experience», J. Neurol., vol. 269, fasc. 11, pp. 5848–5857, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Fofi et al., «Improving distress perception and mutuality in migraine caregivers after 6 months of galcanezumab treatment», Headache, vol. 62, fasc. 9, pp. 1143–1147, ott. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Silvestro et al., «Galcanezumab effect on “whole pain burden” and multidimensional outcomes in migraine patients with previous unsuccessful treatments: a real-world experience», J. Headache Pain, vol. 23, fasc. 1, p. 69, giu. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Kwon, Y.-E. Gil, e M. J. Lee, «Real-world efficacy of galcanezumab for the treatment of migraine in Korean patients», Cephalalgia, vol. 42, fasc. 8, pp. 705–714, lug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Ashina et al., «Galcanezumab effects on incidence of headache after occurrence of triggers, premonitory symptoms, and aura in responders, non-responders, super-responders, and super non-responders», J. Headache Pain, vol. 24, fasc. 1, p. 26, mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Guerzoni, C. Baraldi, F. L. Castro, M. M. Cainazzo, e L. Pani, «Galcanezumab for the treatment of chronic migraine and medication overuse headache: Real-world clinical evidence in a severely impaired patient population», Brain Behav., vol. 13, fasc. 6, p. e2799, mag. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Suzuki et al., «Could efficacy at 1 week after galcanezumab administration for patients with migraine predict responders at 3 months? A real world study», J. Neurol., vol. 270, fasc. 9, pp. 4377–4384, set. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. C. Lee, S. Cho, e B.-K. Kim, «Predictors of response to galcanezumab in patients with chronic migraine: a real-world prospective observational study», Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol., vol. 44, fasc. 7, pp. 2455–2463, lug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. S. di Cola et al., «Migraine Disability Improvement during Treatment with Galcanezumab in Patients with Chronic and High Frequency Episodic Migraine», Neurol. Int., vol. 15, fasc. 1, pp. 273–284, feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Schiano di Cola et al., «Photophobia and migraine outcome during treatment with galcanezumab», Front. Neurol., vol. 13, p. 1088036, gen. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Kim, H. Jang, e M. J. Lee, «Predictors of galcanezumab response in a real-world study of Korean patients with migraine», Sci. Rep., vol. 13, p. 14825, set. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Sacco et al., «European Headache Federation (EHF) consensus on the definition of effective treatment of a migraine attack and of triptan failure», J. Headache Pain, vol. 23, fasc. 1, p. 133, ott. 2022. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).