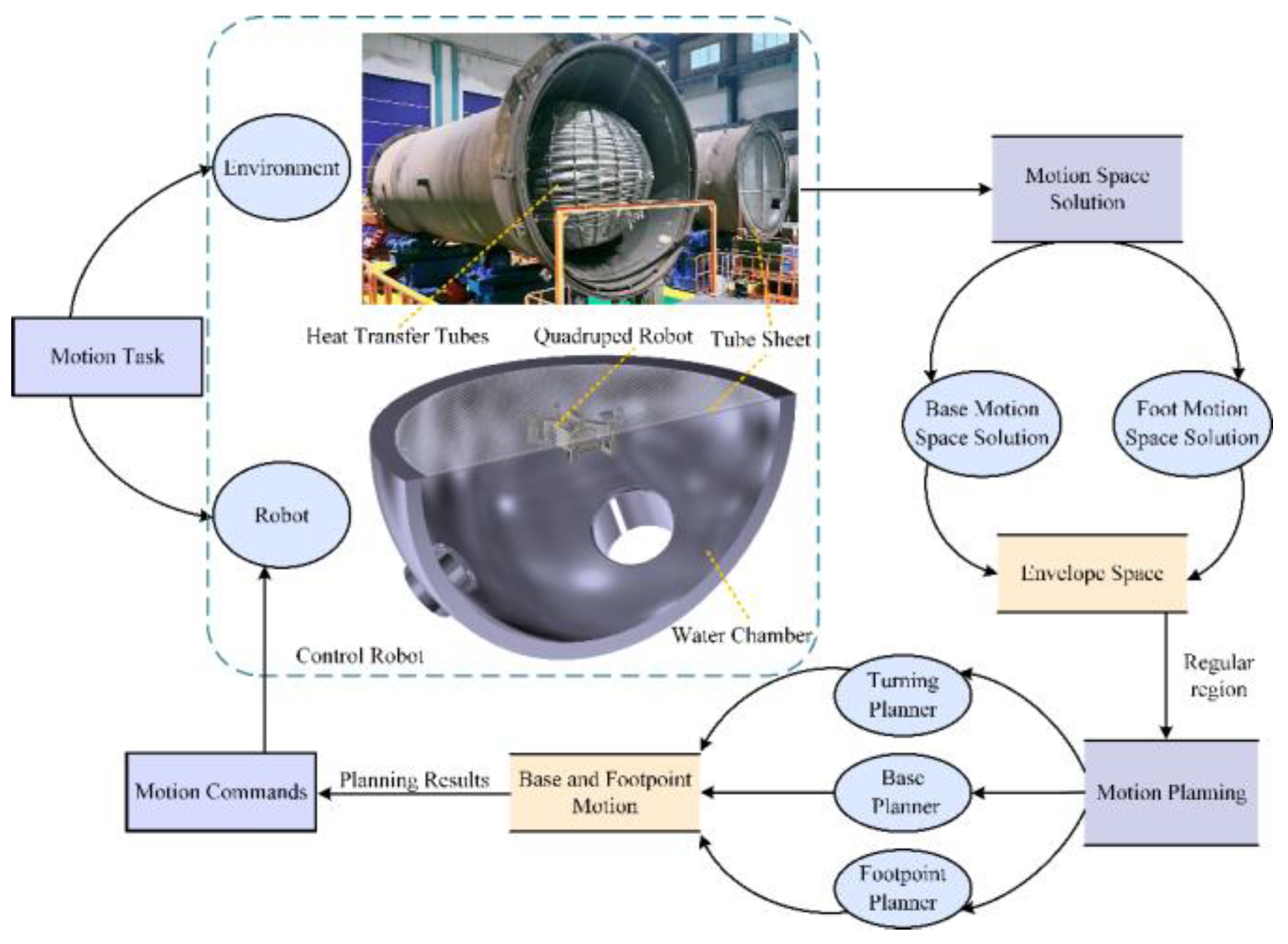

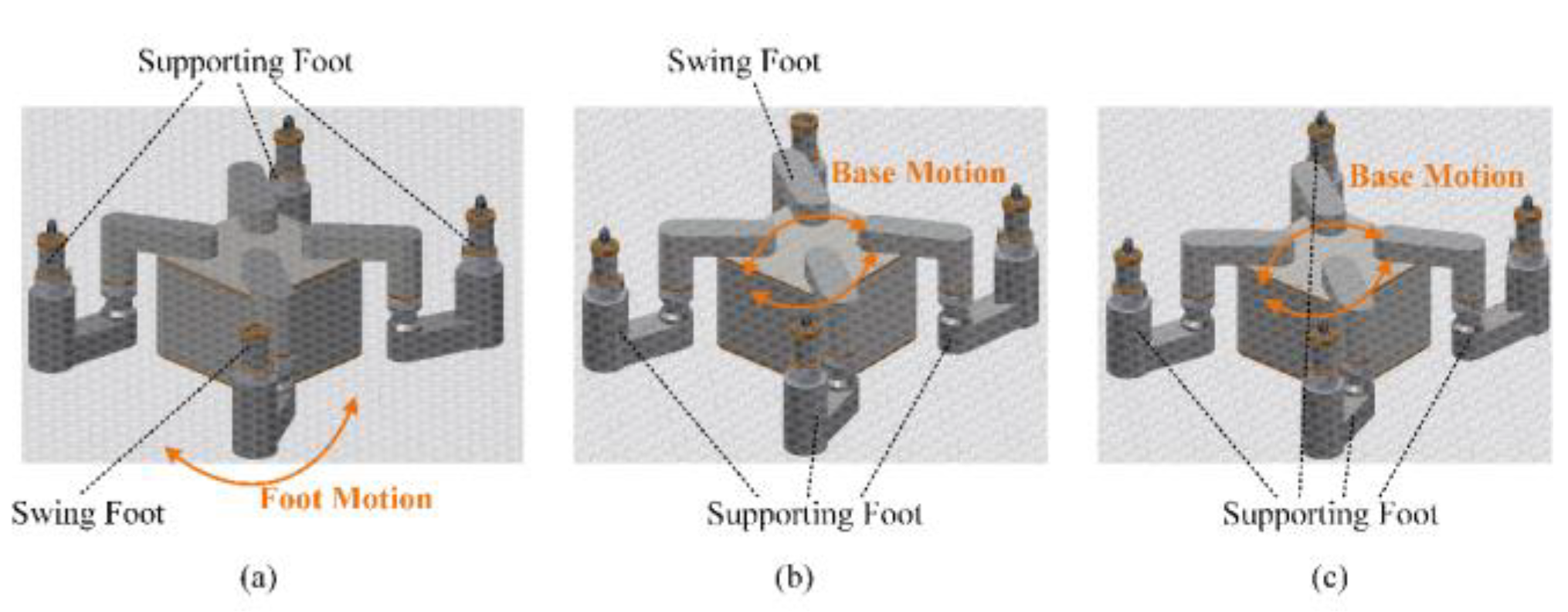

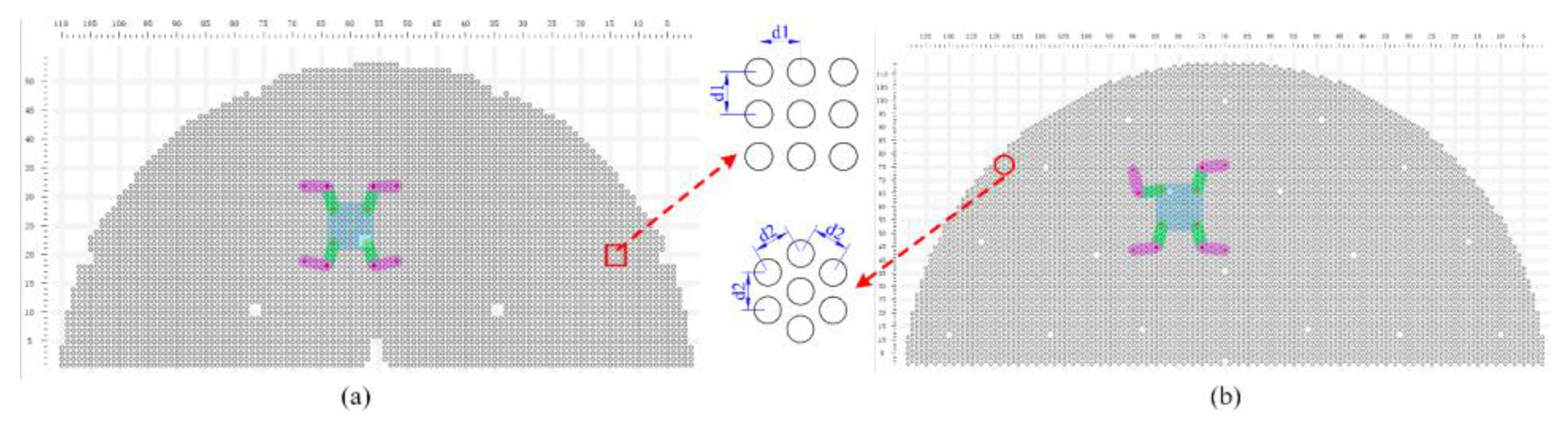

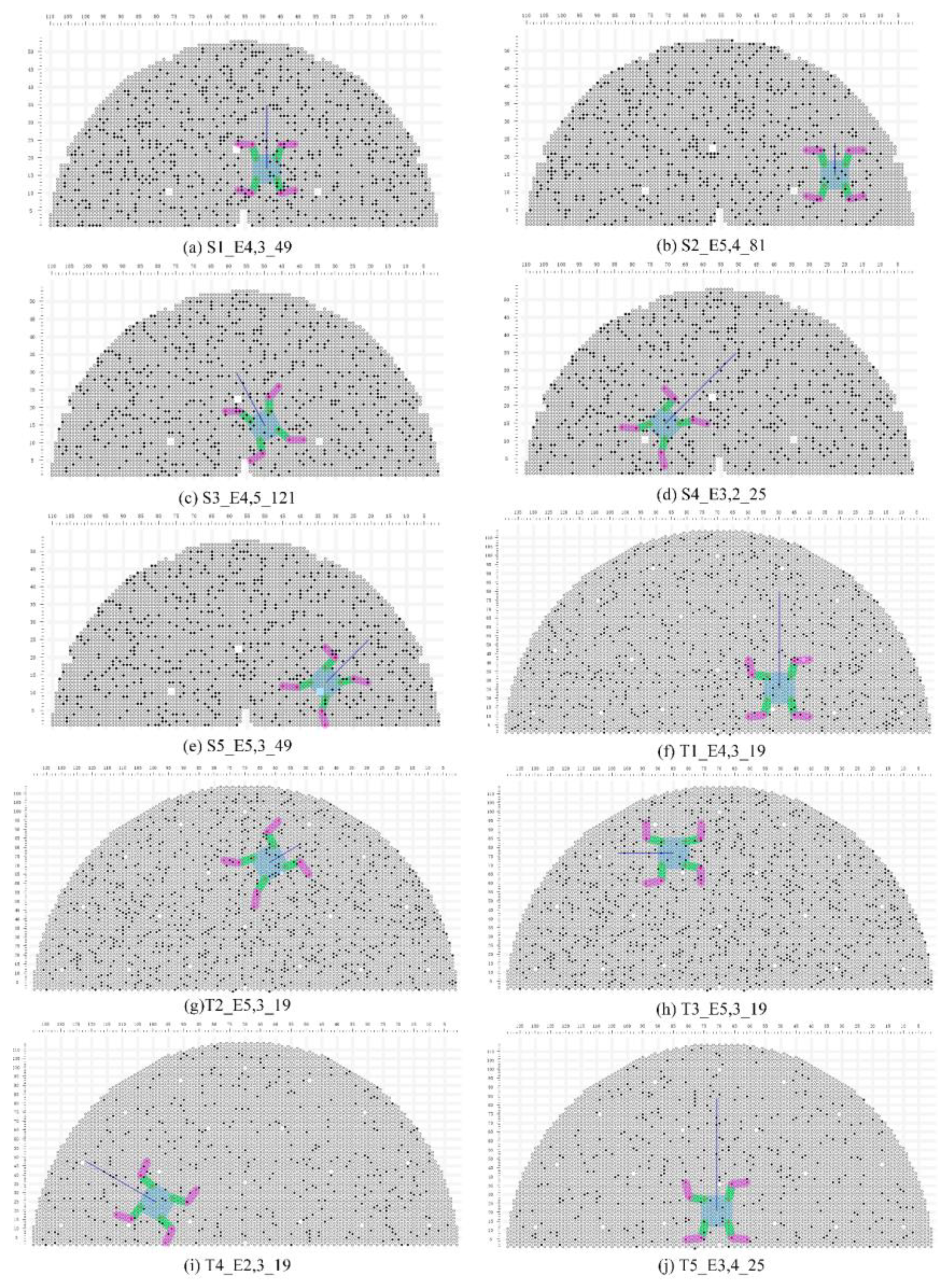

Given the tube plate and the robot's motion path, we con-sider the solved regular robot workspace as prior knowledge. Based on this, we plan the robot's motion, including base motion, base turning, and gait motion.

4.2. Robot Base Motion Planner

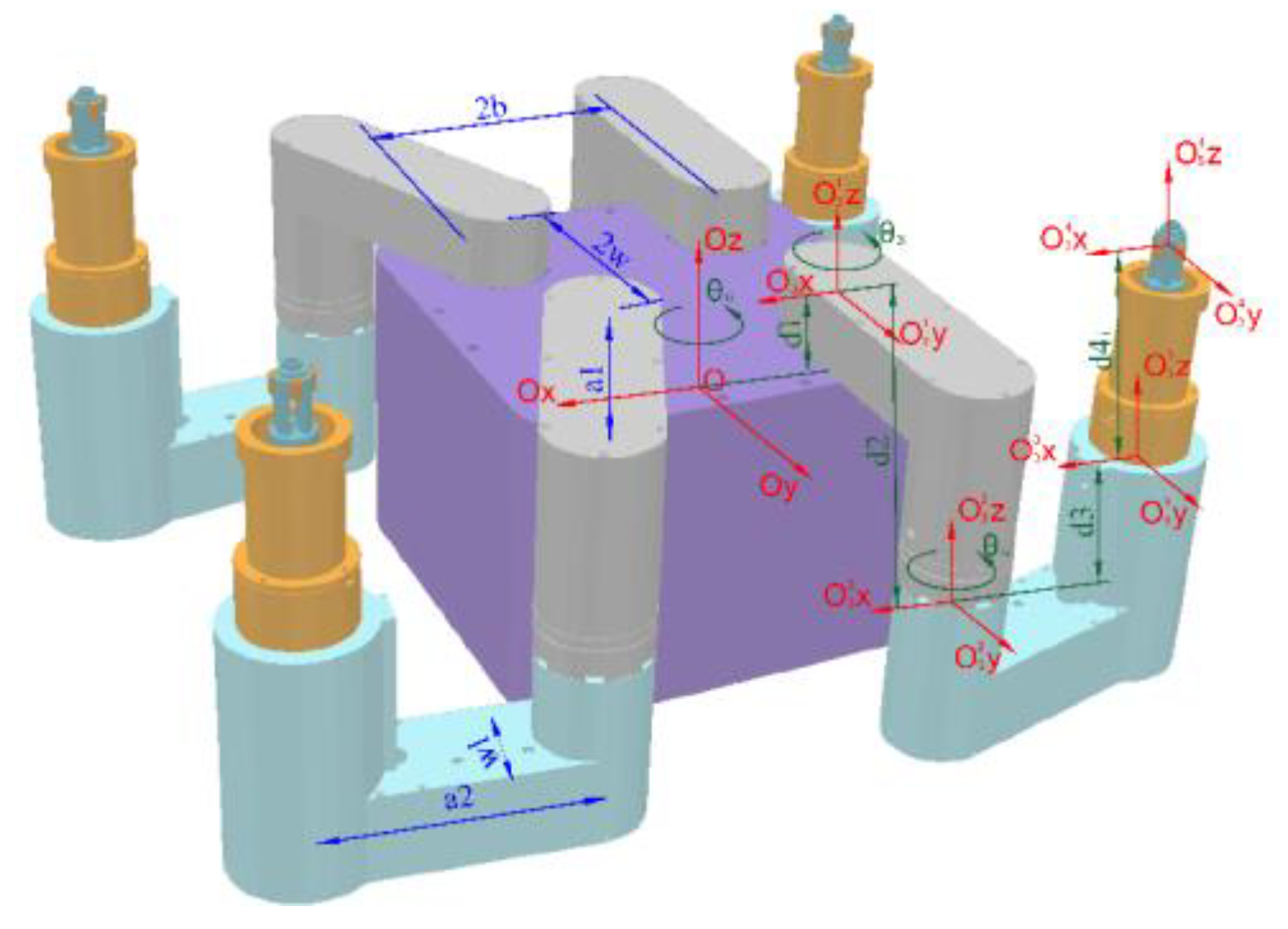

Base motion planning involves determining feasible base trajectories when the foot swings. The points along the base trajectory should lie within the base workspace and align as closely as possible with the given path. Therefore, this section aims to plan the local destinations for each base motion under three supporting feet and one swinging foot, modeling this process as a nonlinear optimization problem to obtain the optimal desired base position. For constrained optimization problems with inequality constraints, various solving methods can be employed. In this section, the Lagrange multiplier method [

24].

Assuming the starting point of the base is

, the destination of the motion direction is

, and the coordinates of the two corner points of the current supporting feet’s bounding rectangle are

and

, the optimal desired base position

is formulated as follows:

where

denotes the L2 norm of A, that is,

. Introducing Lagrange multipliers

, the corresponding Lagrangian function is formulated as follows:

By introducing the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions as follows, the solution set for the optimal ideal base position can be obtained. The evaluation criterion is based on the distance from the global motion destination, where a closer distance indicates a more optimal base position, leading to the derivation of the optimal ideal base position

.

Near the position , conducting a localized search to obtain an optimal feasible base position, satisfying the inverse kinematic feasible solutions. Through the process from the current base position to the optimal feasible base position, a series of base positions can be obtained by solving the inverse kinematics along the motion direction, thereby acquiring the local base motion trajectory.

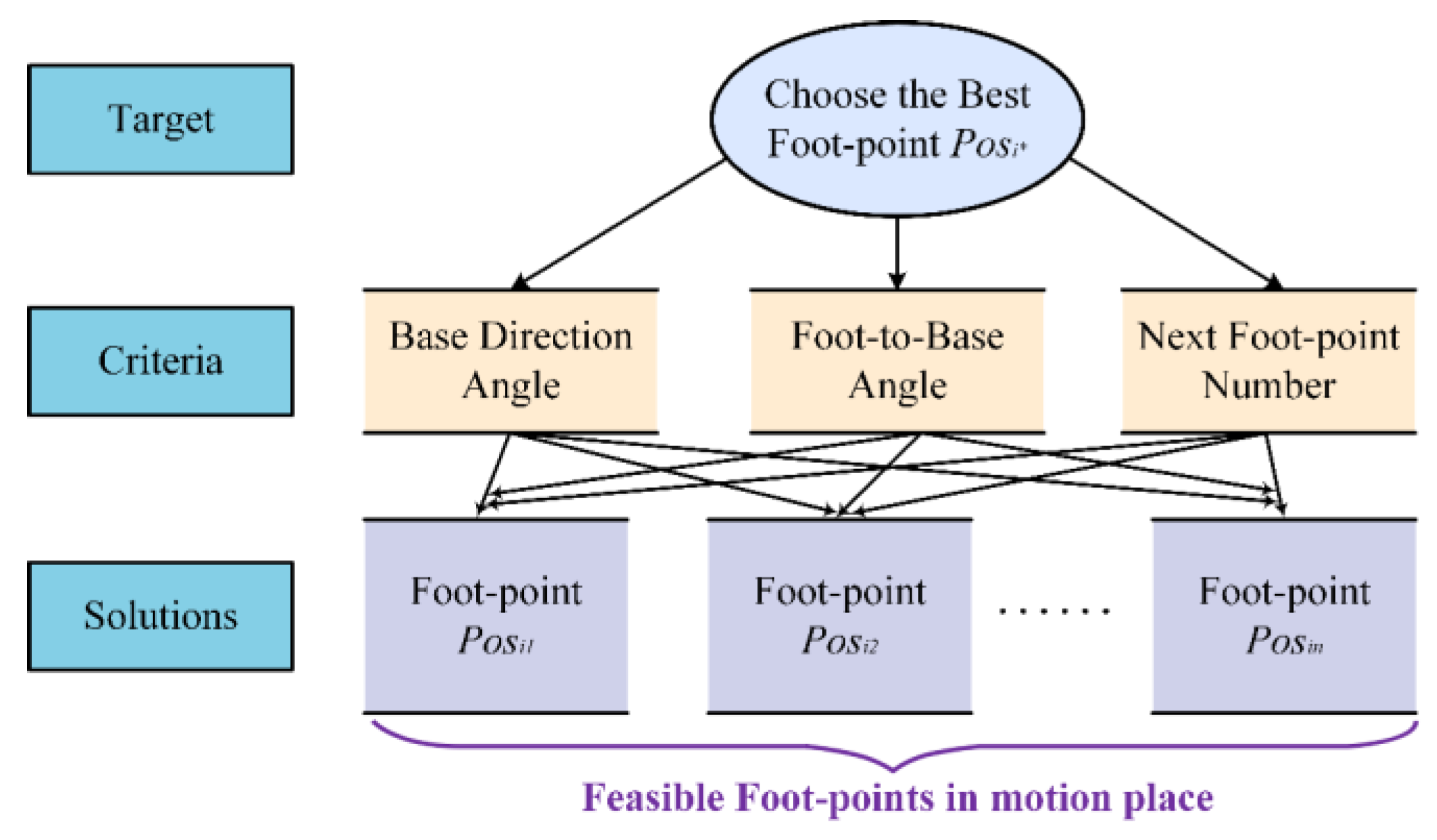

4.4. Robot Gait Motion Planner

Taking the robot posture output from the base turning planner as input to the gait motion planner, we start learning the robot's motion along the given path from existing strategies, aiming to reduce the difficulty of DRL learning [

18]. The network model trained by the D3QN algorithm obtains foot-points, then updates the status, repeating this process until reaching the destination. In this section, the robot's free gait motion is to plan the foot-points, ensuring that the robot can reach the destination as quickly as possible and minimizing the force on the toe modules.

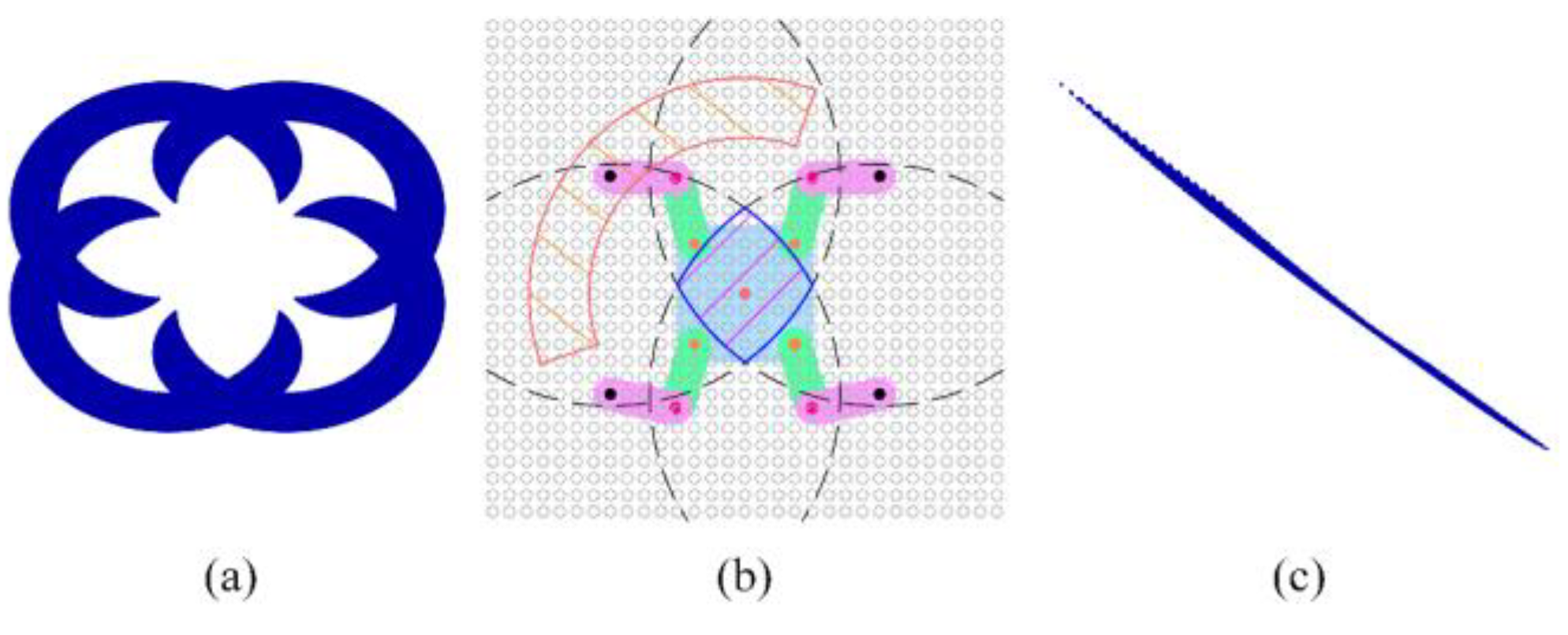

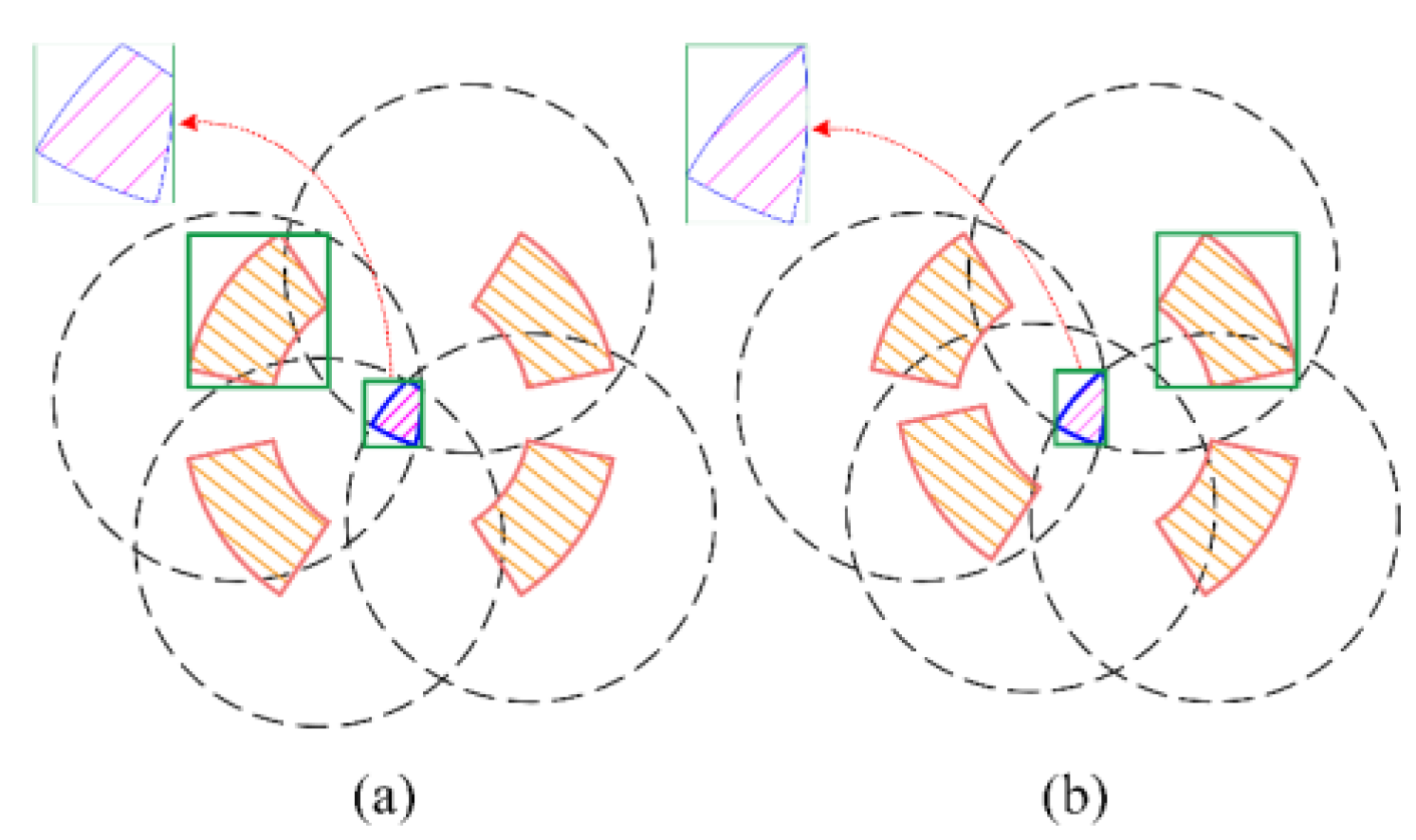

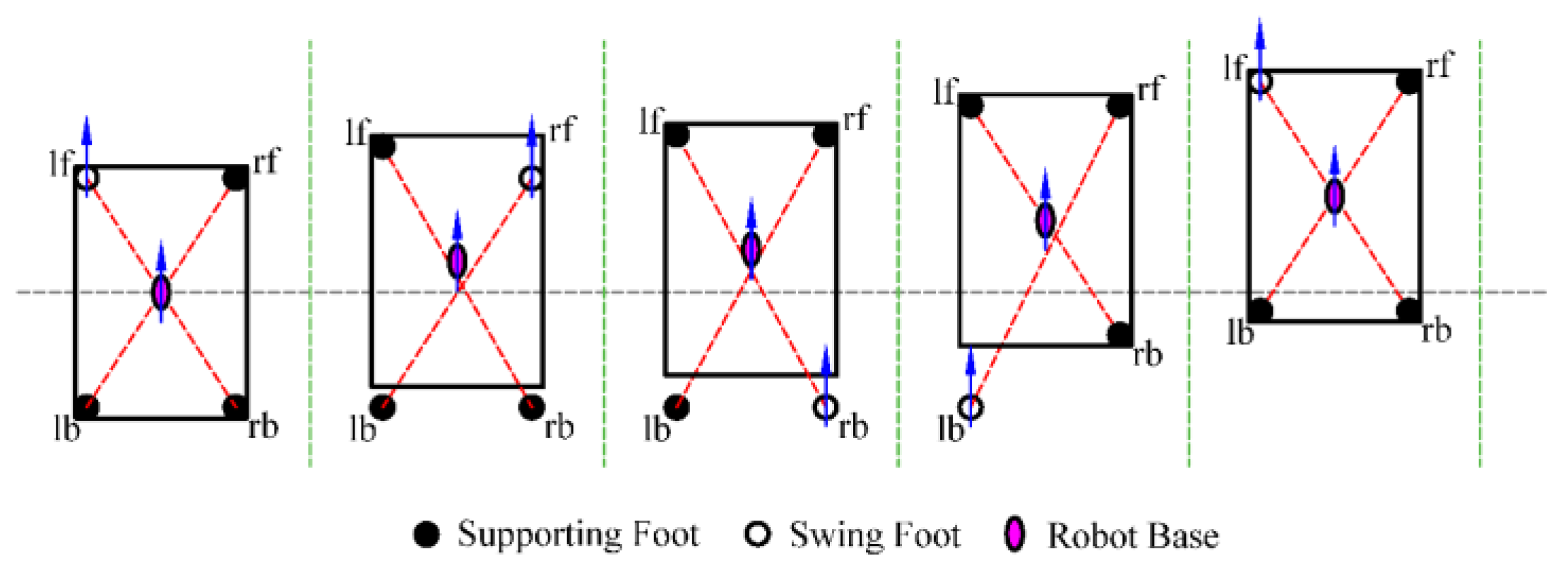

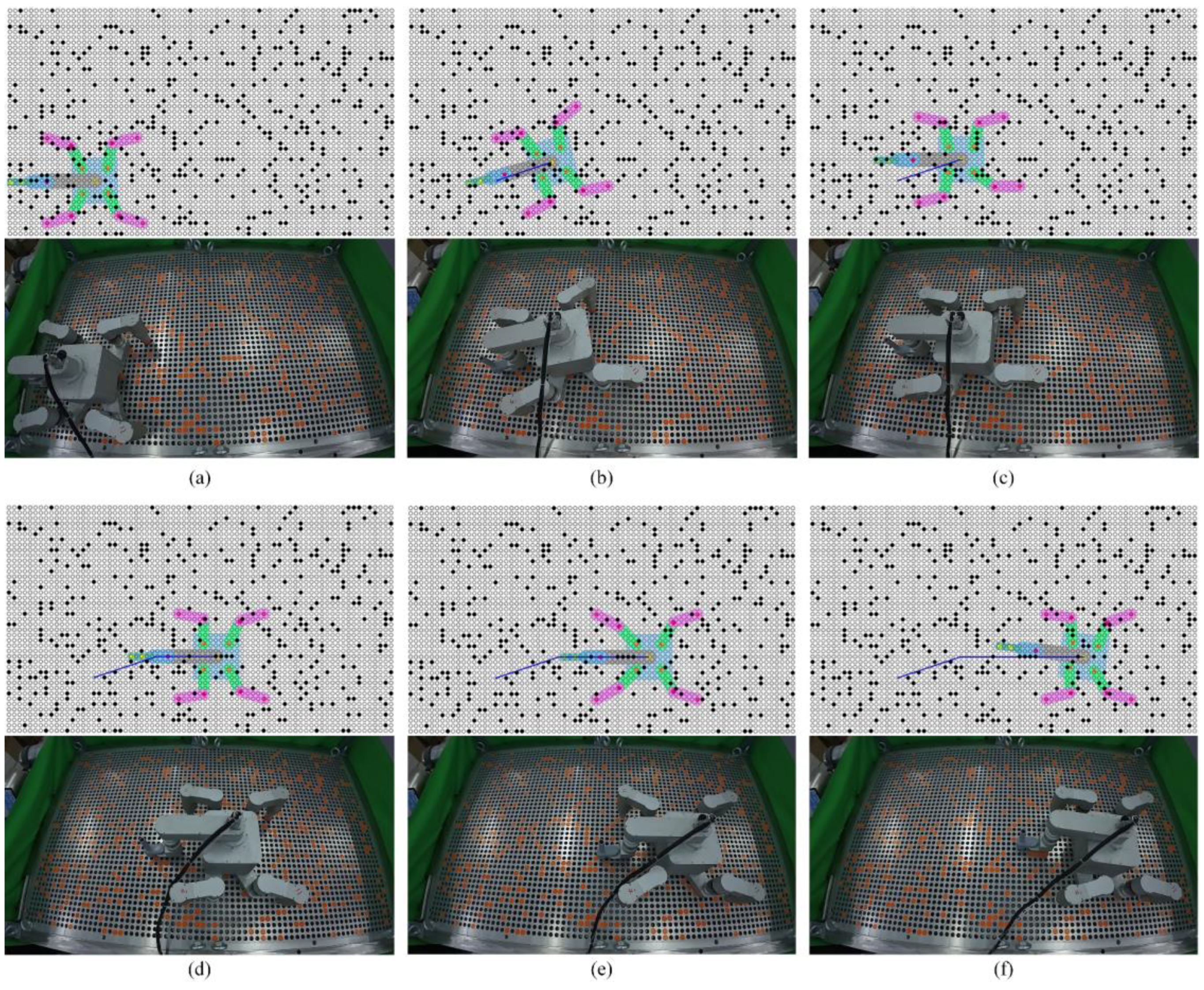

To enhance the flexibility of robot motion, this paper se-lects the foot-point sequence of the left front foot (lf), right front foot (rf), right back foot (rb), and left back foot (lb) along the motion direction, as illustrated in

Figure 8.

The learning-based approach is that the agent learns by multiple interacting with the environment, encouraging positive behaviors and punishing negative ones. We address the sequential decision-making problem of interaction between an agent and its environment with the objective of maximizing the cumulative discounted reward. This problem is modeled as a discrete-time Markov Decision Process, consisting of a tuple , where represents the states of the robot, represents actions, represents the state transition distribution, represents the reward function, and represents the discount factor.

During the training process, the state serves as the input to the robot's motion planning policy network, while the action serves as the output of the policy network. The robot interacts with the environment based on the selected actions from the policy network, leading to transitions in the robot's state. Simultaneously, the environment provides feedback through a reward function . The policy network then selects the next action based on the updated state and reward function. The continuous updating of the policy network is the training process for the motion planner using RL algorithms.

Action Space : For most quadruped robots employing RL, the action space typically consists of joint positions [

27]. However, since each foot places on a specific hole on the plate, in order to reduce unnecessary exploration at the decision-making level, this paper defines the action space as a one-dimensional vector of discrete foot-point scores, as shown as follows. Each action corresponds to a foot-point

, which is an offset relative to the current foot position

, where

. Here,

represents the number of foot-points that satisfy all possible inverse kinematics conditions and is also the dimension of the action space.

State Space: The state space typically includes information such as the robot's position and joint positions [

21]. To simplify the learning process, this paper considers prior information on the accessibility of actions offline when designing the state space, and adds the target position to guide learning. The state space

is defined as follows, containing the pose of the robot

, the global motion destination

, and the judgment flag

indicating whether the foothold point corresponding to the action space can be landed on. Here,

indicates that the foot-point is feasible, and

indicates that the foot-point is not feasible.

Reward Function

: The reward function is set based on specific task objectives [

27]. The reward function

consists of three parts and is designed as follows. One part is the regular penalty, where each step incurs a penalty

to ensure that the robot does not move excessively or remain stationary; another part is the reward/penalty for forward/backward movement

; the third part is the stability reward/penalty

. Besides,

represents the distance traveled by the foot along the motion direction, where a positive value indicates proximity to the target, a negative value indicates moving away from the target, and zero indicates stationary movement along the direction of motion;

represents the maximum distance the foot can move within the action space;

represents the distance from the centroid of the stable triangle formed by the current supporting feet to the base;

represents the distance from the centroid of the stable triangle formed by the current supporting feet to the given motion direction.

are parameters related to the reward function.

Termination Conditions: Termination conditions are crucial for initializing the state during the training process and for early termination of erroneous actions, thereby avoiding the wastage of computational resources [

21]. This paper designs the following termination conditions:

Success Termination Condition: When the robot's base position matches the target base position, it indicates that the robot has successfully reached the destination.

Failure Termination Condition: When the robot's base position oscillates repeatedly, or when the current swing foot position oscillates back and forth, it indicates failure of the current exploration.

Action Selection: Action selection essentially addresses the proportion problem between exploration and exploitation, i.e., a trade-off between exploration and exploitation [

28]. A simple and feasible method is the

-greedy method [

29]. At each time step, the agent takes a random action with a fixed probability

, instead of greedily selecting the optimal action learned about the Q function [

30]. In this paper, during greedy selection, a mask layer is added behind the output layer of the neural network, which is a list indicating whether the foot-point is feasible, to ensure that the highest scoring action is reachable, thereby avoiding a large number of unnecessary failure termination conditions. Similarly, during random selection, actions are chosen only from the list of feasible foot-points

. Action selection is depicted as follows, where

is a uniformly random number sampled at each time step.

Gait Planner: The gait planning strategy parameters are transformed into a neural network, consisting of two hidden layers with a size of 64 each and an activation function. In each iteration, based on the current state, the neural net-work outputs the Q-values for each action through a linear output layer, and then the action selection method is used to choose the action for this state.

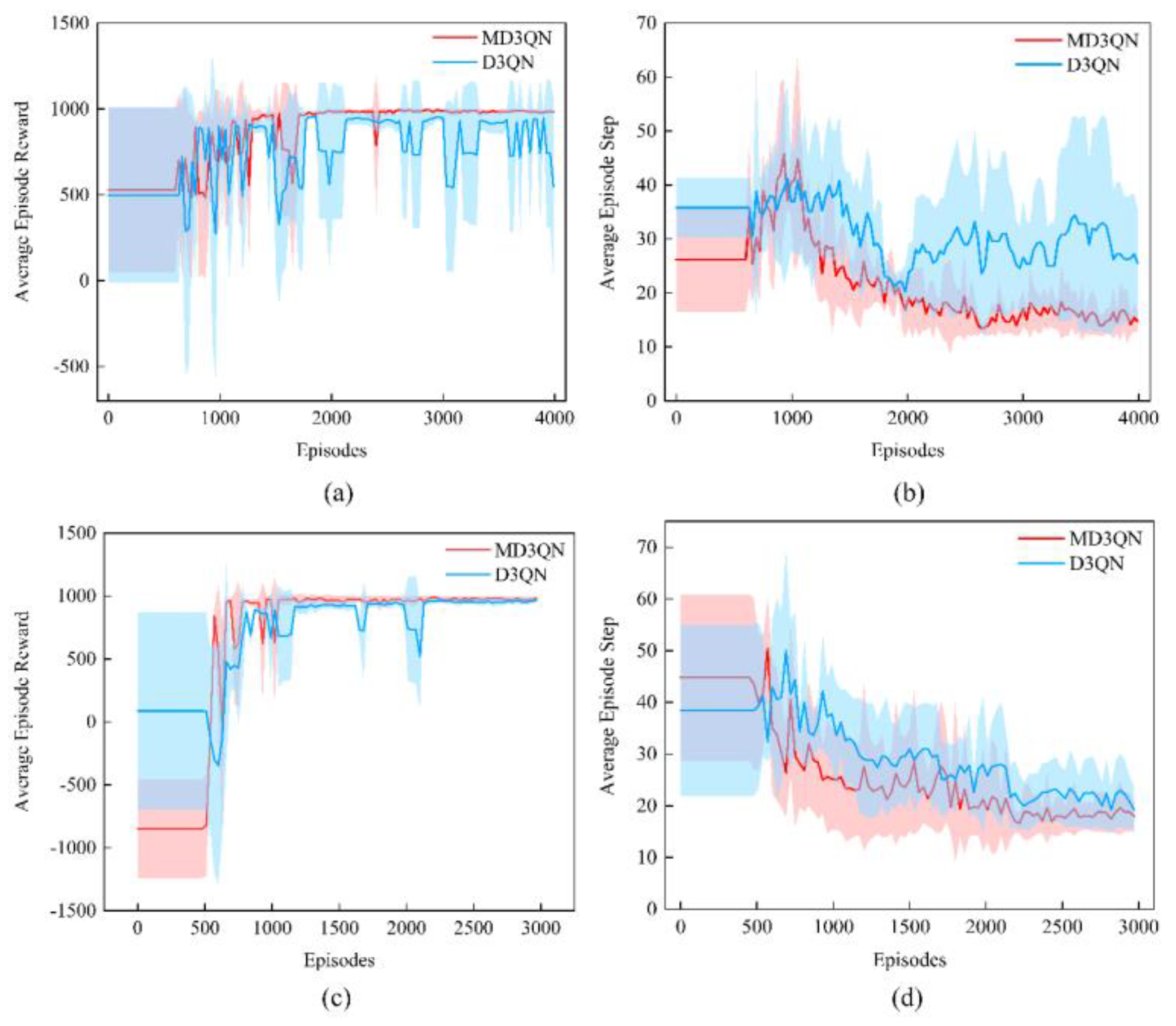

D3QN algorithm:

The D3QN algorithm is a variant algorithm that combines aspects of both Double DQN and Dueling DQN. It aims to eliminate the maximization bias during network updates, address the issue of overestimation, and expedite algorithm convergence. Compared to the traditional DQN algorithm, D3QN primarily optimizes in two aspects. Firstly, it adopts the same optimized TD error target as the Double DQN algorithm and utilizes two networks for updates: an evaluation network (parameter

)) is employed to determine the next action, while a target network (parameter

) calculates the value of the state at time t + 1, thereby mitigating the problem of overestimation. The target for D3QN updates is expressed as follows, where

represents the discount factor,

denotes the reward function at time

t + 1, and

denotes the state-action value function with respect to state

and action

.

Secondly, the D3QN algorithm decomposes the state-action value function into two components, consistent with the Dueling DQN algorithm, to model the state value function and the advantage function separately, thereby better-handling states with smaller associations with actions. The newly defined state-action value function is represented as follows, where the maximization operation is replaced with the mean operation for enhanced stability of the algorithm. Here,

denotes the state value function with respect to the state

,

represents the advantage function with respect to the state

and action

, and

mean denotes the mean operation.

Building upon the foundation of the D3QN algorithm, this paper establishes four separate MD3QN network models for each leg that incorporates a mask during action selection. The gait planning algorithm for quadrupedal robots based on the MD3QN algorithm is depicted in Algorithm 2.

|

Algorithm 2 Gait Planning Based on MD3QN |

|

Input:, attenuation parameter , attenuation rate , minimum attenuation value , target network update frequency freq, Soft update parameter , maximum number of per episode , maximum number episodes , maximum number of experience pool

|

|

Output: eval network that can output gaits according to state s

|

| Initialize the experience pool M, and the parameters and |

|

for episode do

|

| Reset and obtain the initialization state |

| for time step do

|

| for foot do

|

| Choose action |

| Compute reward |

| Obtain the new state and done flag |

| Store experience { into M

|

| if len(M) bs then

|

| Sample batch data from the experience pool M

|

| Obtain the target values |

Do a gradient descent step with loss

update |

|

end if

|

|

if

|

| Update : |

|

end if

|

|

|

|

end for

|

|

end for

|

| end for |