Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

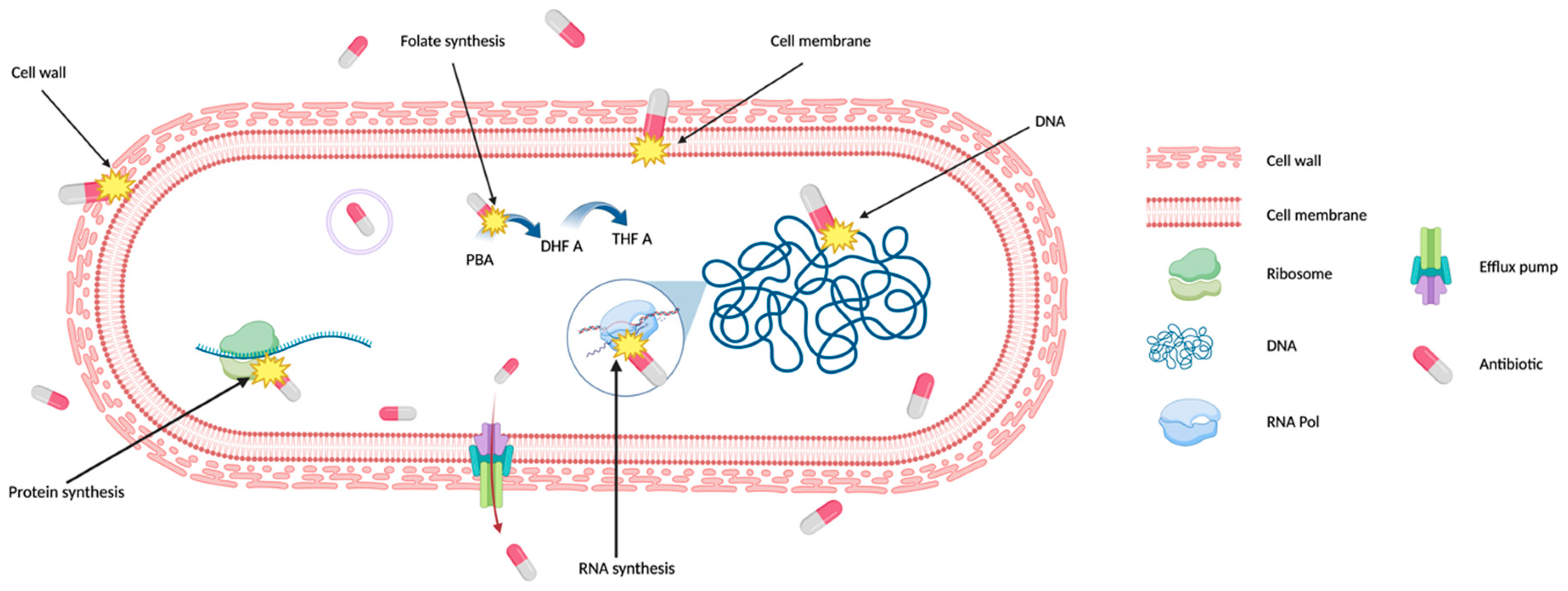

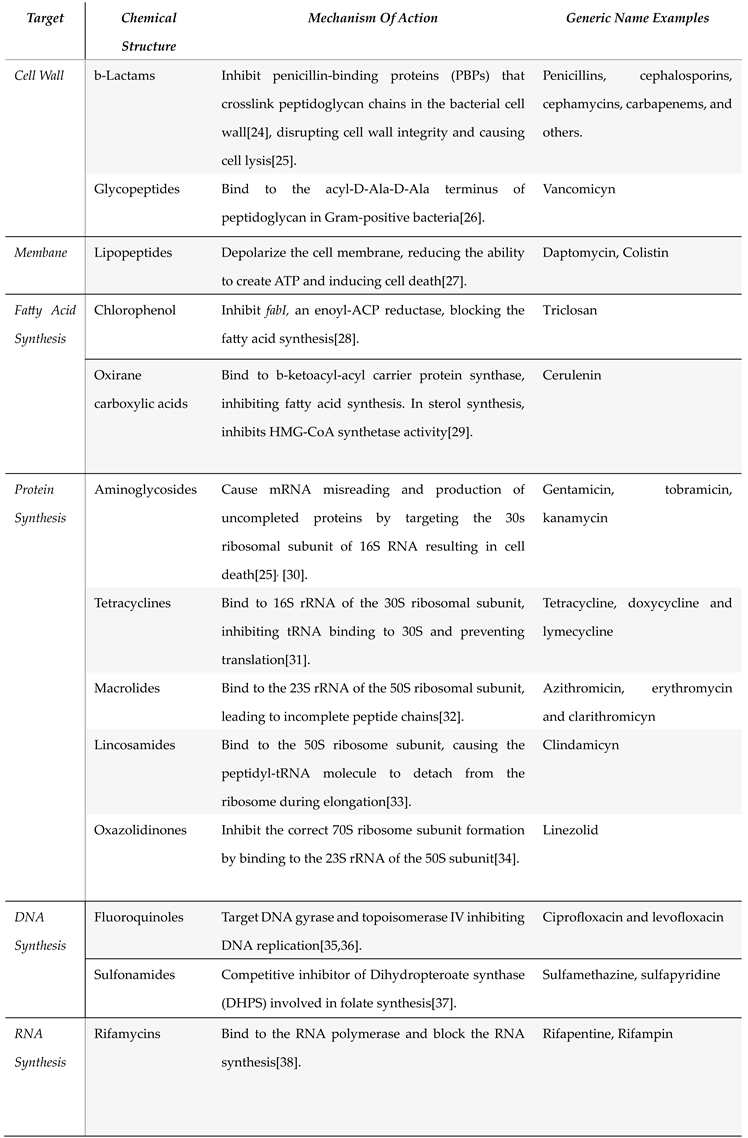

2. Antibiotic Mechanism of Action and Antibiotic Targets

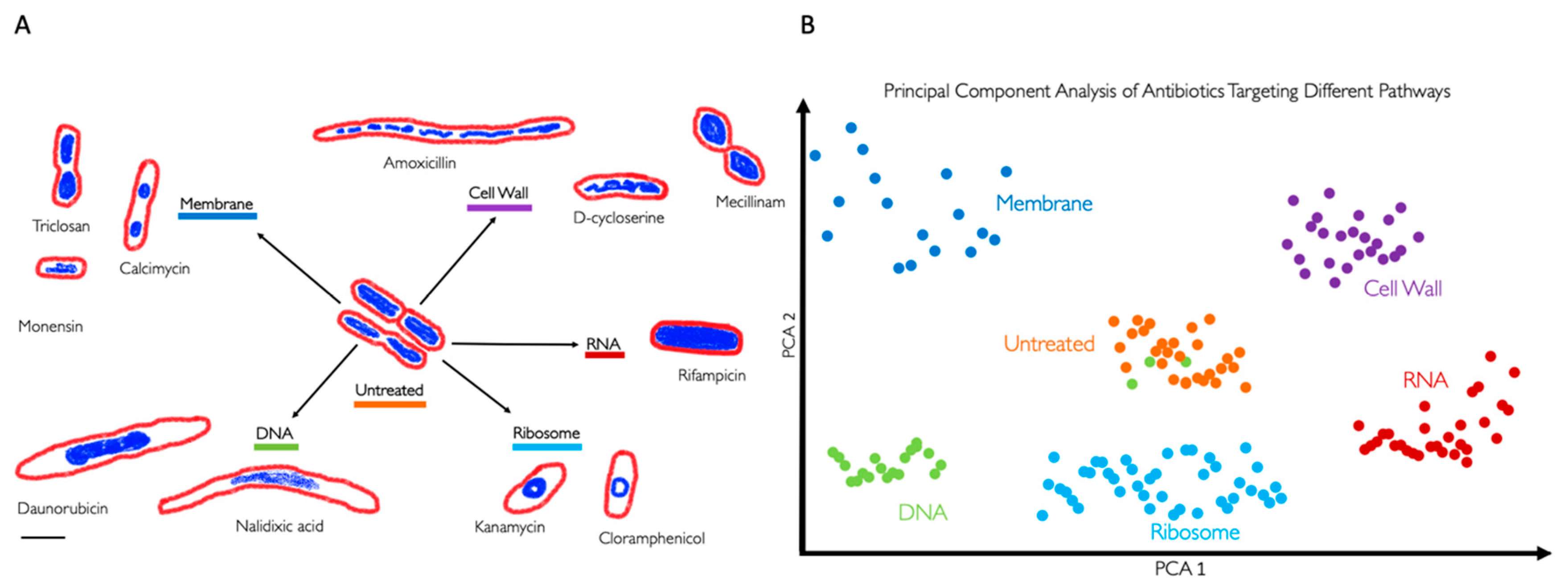

3. BCP to Identify the Mechanism of Action

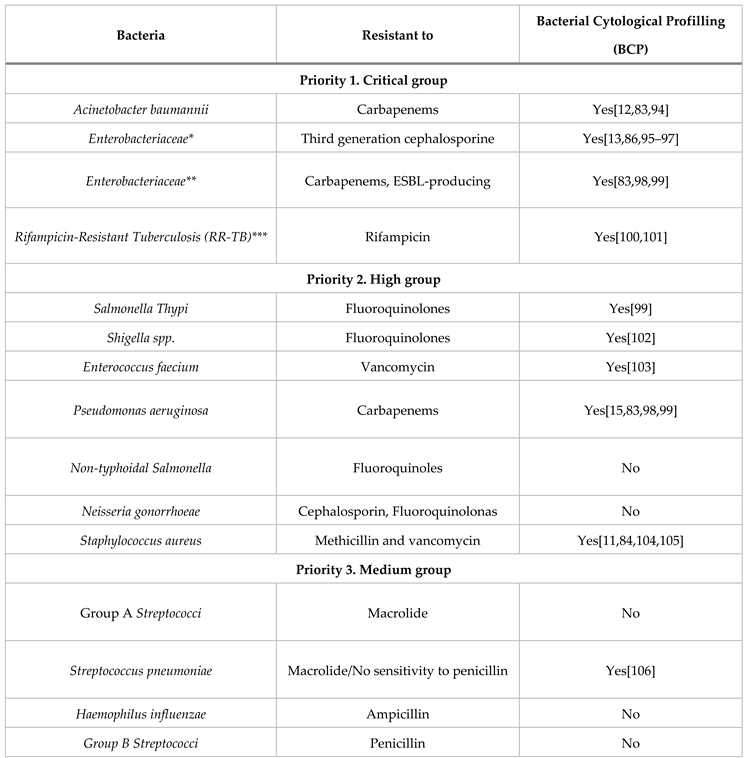

4. BCP of Important Human Pathogens

5. BCP to Identify New Druggable Cell Pathways

6. BCP Limitations

7. BCP Potential Improvements

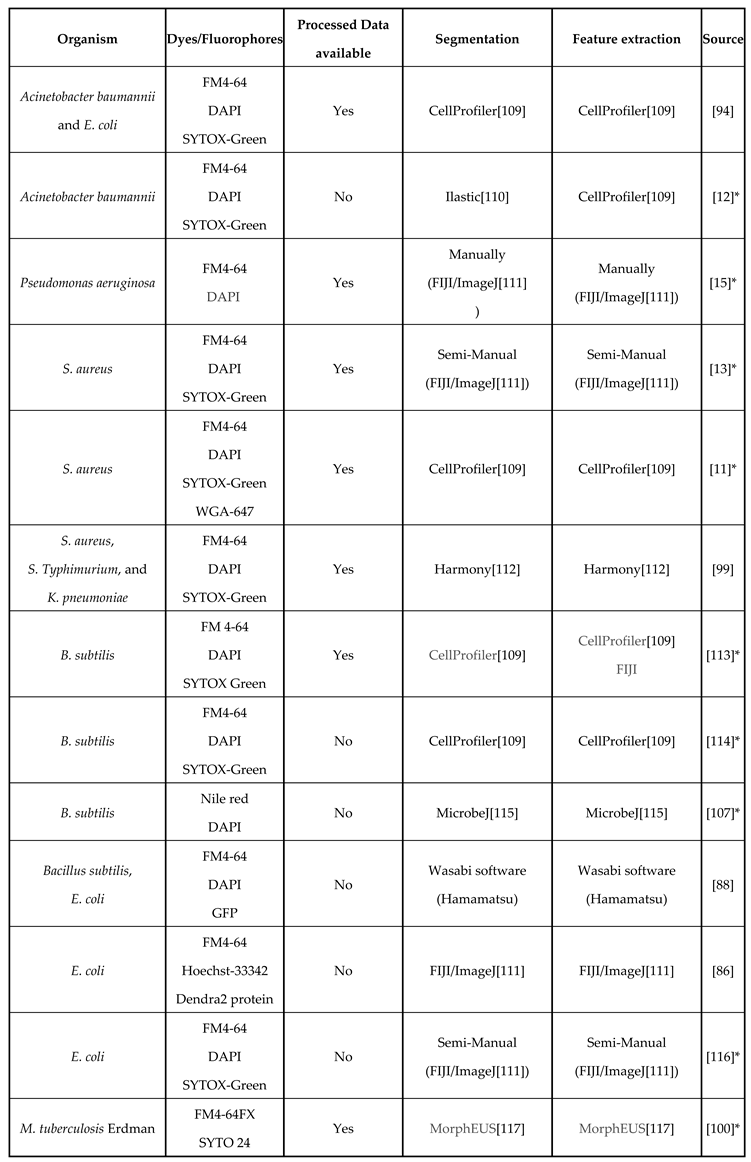

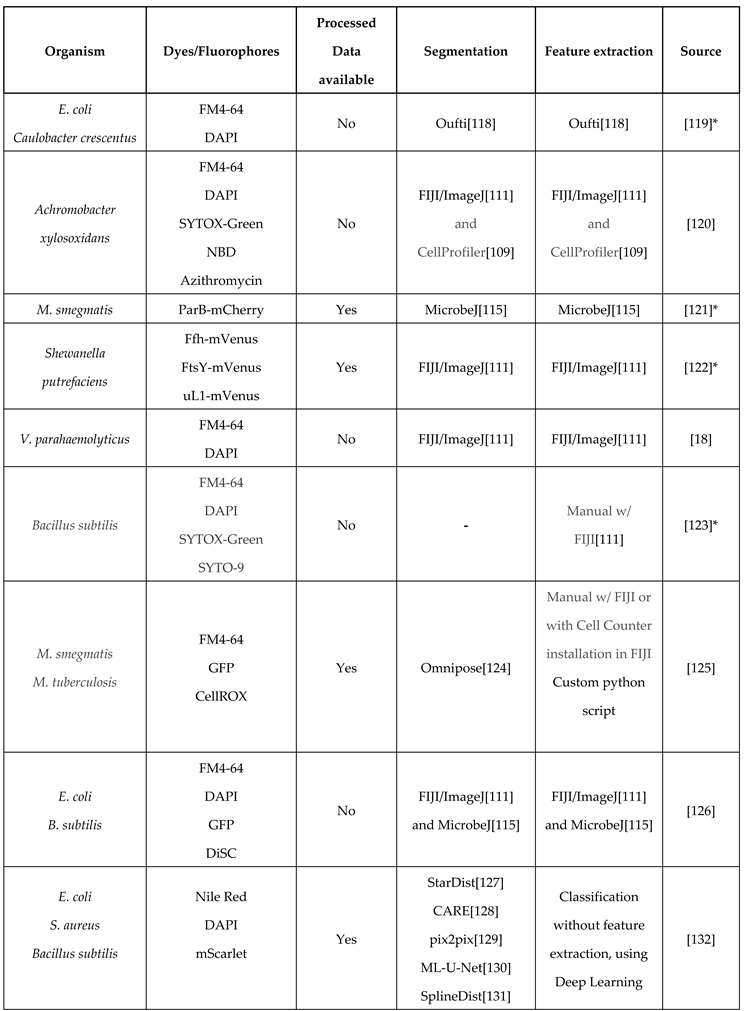

8. Image Analysis Tools for BCP and Data Availability

9. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.) Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.), 2019.

- O’Neill, J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. 2016.

- GARDNER, A.D. Morphological Effects of Penicillin on Bacteria. Nature 1940, 146, 837–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, A. Microscopical Effect of Penicillin on Spores and Vegetative Cells of Bacilli. Lancet 1945, 658–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, M.I.; Truman, A.W.; Wilkinson, B. Antibiotics: past, present and future. Curr Opin Microbiol 2019, 51, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C. Molecular mechanisms that confer antibacterial drug resistance. Nature 2000, 406, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luepke, K.H.; Suda, K.J.; Boucher, H.; Russo, R.L.; Bonney, M.W.; Hunt, T.D.; Mohr, J.F. Past, Present, and Future of Antibacterial Economics: Increasing Bacterial Resistance, Limited Antibiotic Pipeline, and Societal Implications. Pharmacotherapy 2017, 37, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampaloni, C.; Mattei, P.; Bleicher, K.; Winther, L.; Thäte, C.; Bucher, C.; Adam, J.-M.; Alanine, A.; Amrein, K.E.; Baidin, V.; et al. A novel antibiotic class targeting the lipopolysaccharide transporter. Nature 2024, 625, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, D.T.; Sakoulas, G.; Nizet, V.; Pogliano, J.; Pogliano, K. Bacterial Cytological Profiling (BCP) as a Rapid and Accurate Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Method for Staphylococcus aureus. EBioMedicine 2016, 4, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samernate, T.; Htoo, H.H.; Sugie, J.; Chavasiri, W.; Pogliano, J.; Chaikeeratisak, V.; Nonejuie, P. High-Resolution Bacterial Cytological Profiling Reveals Intrapopulation Morphological Variations upon Antibiotic Exposure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2023, 67, e01307–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonejuie, P.; Burkart, M.; Pogliano, K.; Pogliano, J. Bacterial cytological profiling rapidly identifies the cellular pathways targeted by antibacterial molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 16169–16174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deep, A.; Liang, Q.; Enustun, E.; Pogliano, J.; Corbett, K.D. Architecture and activation mechanism of the bacterial PARIS defence system. Nature 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsunemoto, H.; Sugie, J.; Enustun, E.; Pogliano, K.; Pogliano, J. Bacterial cytological profiling reveals interactions between jumbo phage φKZ infection and cell wall active antibiotics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PloS one 2023, 18, e0280070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkholz, E.A.; Morgan, C.J.; Laughlin, T.G.; Lau, R.K.; Prichard, A.; Rangarajan, S.; Meza, G.N.; Lee, J.; Armbruster, E.; Suslov, S.; et al. An intron endonuclease facilitates interference competition between coinfecting viruses. Science 2024, 385, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thammatinna, K.; Egan, M.E.; Htoo, H.H.; Khanna, K.; Sugie, J.; Nideffer, J.F.; Villa, E.; Tassanakajon, A.; Pogliano, J.; Nonejuie, P.; et al. A novel vibriophage exhibits inhibitory activity against host protein synthesis machinery. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonthonsrima, T.; Htoo, H.H.; Thiennimitr, P.; Srisuknimit, V.; Nonejuie, P.; Chaikeeratisak, V. Phage-induced bacterial morphological changes reveal a phage-derived antimicrobial affecting cell wall integrity. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2023, 67, e00764–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naknaen, A.; Samernate, T.; Wannasrichan, W.; Surachat, K.; Nonejuie, P.; Chaikeeratisak, V. Combination of genetically diverse Pseudomonas phages enhances the cocktail efficiency against bacteria. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 8921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naknaen, A.; Samernate, T.; Saeju, P.; Nonejuie, P.; Chaikeeratisak, V. Nucleus-forming jumbophage PhiKZ therapeutically outcompetes non-nucleus-forming jumbophage Callisto. iScience 2024, 27, 109790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, F.; Martinez, J.L. Phenotypic Resistance to Antibiotics. Antibiotics 2013, 2, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Davies, D. Origins and Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2010, 74, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotsonas King, A.; Wu, L. Macromolecular Synthesis and Membrane Perturbation Assays for Mechanisms of Action Studies of Antimicrobial Agents. CP Pharmacology 2009, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, L.M.; Silva, B.N.M. da; Barbosa, G.; Barreiro, E.J. β-lactam antibiotics: An overview from a medicinal chemistry perspective. Eur J Med Chem 2020, 208, 112829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baquero, F.; Levin, B.R. Proximate and ultimate causes of the bactericidal action of antibiotics. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, P.E. Structure, biochemistry and mechanism of action of glycopeptide antibiotics. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1989, 8, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerala, R. Synthetic lipopeptides: a novel class of anti-infectives. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2007, 16, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, A.; Beyhan, S.; Choi, Y.; Morales, P.; Chan, A.P.; Espinoza, J.L.; Dupont, C.L.; Meyer, K.J.; Spoering, A.; Lewis, K.; et al. Mechanism-of-Action Classification of Antibiotics by Global Transcriptome Profiling. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020, 64, e01207–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem Cerulenin. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5282054 (accessed on Aug 14, 2024).

- Davis, B.D.; Chen, L.L.; Tai, P.C. Misread protein creates membrane channels: an essential step in the bactericidal action of aminoglycosides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986, 83, 6164–6168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, I.; Roberts, M. Tetracycline Antibiotics: Mode of Action, Applications, Molecular Biology, and Epidemiology of Bacterial Resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2001, 65, 232–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Laslop, N.; Mankin, A.S. How Macrolide Antibiotics Work. Trends Biochem Sci 2018, 43, 668–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenson, T.; Lovmar, M.; Ehrenberg, M. The Mechanism of Action of Macrolides, Lincosamides and Streptogramin B Reveals the Nascent Peptide Exit Path in the Ribosome. Journal of Molecular Biology 2003, 330, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaney, S.M.; Aoki, H.; Ganoza, M.C.; Shinabarger, D.L. The oxazolidinone linezolid inhibits initiation of protein synthesis in bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998, 42, 3251–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, S.; Poeta, P.; Hébraud, M.; Capelo, J.L.; Igrejas, G. Mechanisms of quinolone action and resistance: where do we stand? J Med Microbiol 2017, 66, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojkic, N.; Lilja, E.; Direito, S.; Dawson, A.; Allen, R.J.; Waclaw, B. A Roadblock-and-Kill Mechanism of Action Model for the DNA-Targeting Antibiotic Ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020, 64, e02487–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, W.R.; Oliver, A.G.; Linington, R.G. Development of Antibiotic Activity Profile Screening for the Classification and Discovery of Natural Product Antibiotics. Chemistry & Biology 2012, 19, 1483–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohanski, M.A.; Dwyer, D.J.; Collins, J.J. How antibiotics kill bacteria: from targets to networks. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010, 8, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO AWaRe classification of antibiotics for evaluation and monitoring of use, 2023 2023.

- Silver, L.L. Challenges of Antibacterial Discovery. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011, 24, 71–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M.A.; Lockless, S.W. Elucidating the Mechanisms of Action of Antimicrobial Agents. mBio 13, e02240-21. [CrossRef]

- Hage, D.S.; Anguizola, J.A.; Bi, C.; Li, R.; Matsuda, R.; Papastavros, E.; Pfaunmiller, E.; Vargas, J.; Zheng, X. Pharmaceutical and biomedical applications of affinity chromatography: Recent trends and developments. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2012, 69, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, H.; Mathieson, T.; Childs, D.; Sweetman, G.M.A.; Werner, T.; Tögel, I.; Doce, C.; Gade, S.; Bantscheff, M.; Drewes, G.; et al. Thermal proteome profiling for unbiased identification of direct and indirect drug targets using multiplexed quantitative mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc 2015, 10, 1567–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. Platforms for antibiotic discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2013, 12, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.; Lee, R.E.; Brötz-Oesterhelt, H.; Hiller, S.; Rodnina, M.V.; Schneider, T.; Weingarth, M.; Wohlgemuth, I. Sophisticated natural products as antibiotics. Nature 2024, 632, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, N.Q.; Helaine, S.; Lewis, K.; Ackermann, M.; Aldridge, B.; Andersson, D.I.; Brynildsen, M.P.; Bumann, D.; Camilli, A.; Collins, J.J.; et al. Definitions and guidelines for research on antibiotic persistence. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019, 17, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kussell, E.; Kishony, R.; Balaban, N.Q.; Leibler, S. Bacterial Persistence. Genetics 2005, 169, 1807–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

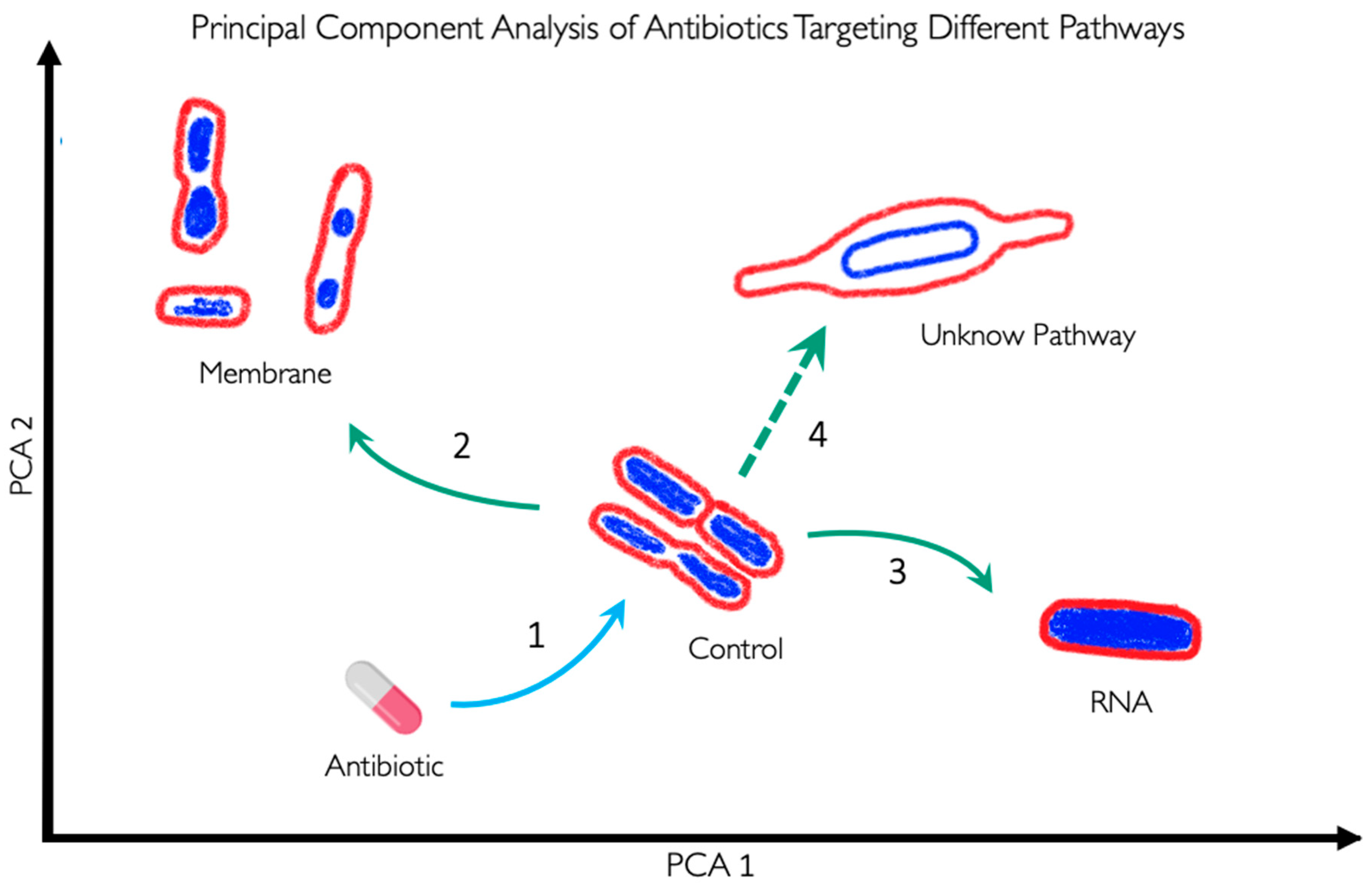

- Bailey, S. Principal Component Analysis with Noisy and/or Missing Data. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 2012, 124, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Broeck, T.; Joniau, S.; Clinckemalie, L.; Helsen, C.; Prekovic, S.; Spans, L.; Tosco, L.; Van Poppel, H.; Claessens, F. The Role of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in Predicting Prostate Cancer Risk and Therapeutic Decision Making. BioMed Research International 2014, 2014, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regev, A.; Teichmann, S.A.; Lander, E.S.; Amit, I.; Benoist, C.; Birney, E.; Bodenmiller, B.; Campbell, P.; Carninci, P.; Clatworthy, M.; et al. The Human Cell Atlas. eLife 2017, 6, e27041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction 2020.

- Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Rudin, C.; Shaposhnik, Y. Understanding How Dimension Reduction Tools Work: An Empirical Approach to Deciphering t-SNE, UMAP, TriMAP, and PaCMAP for Data Visualization 2021.

- Martin, J.K.; Sheehan, J.P.; Bratton, B.P.; Moore, G.M.; Mateus, A.; Li, S.H.-J.; Kim, H.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; Typas, A.; Savitski, M.M.; et al. A Dual-Mechanism Antibiotic Kills Gram-Negative Bacteria and Avoids Drug Resistance. Cell 2020, 181, 1518–1532.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebayashi, Y.; Ramos-Soriano, J.; Jiang, Y.J.; Samphire, J.; Belmonte-Reche, E.; O’Hagan, M.P.; Gurr, C.; Heesom, K.J.; Lewis, P.A.; Samernate, T.; et al. Small molecule G-quadruplex ligands are antibacterial candidates for Gram-negative bacteria 2024, 2022. 09.01.50 6212. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Japaridze, A.; Zheng, X.; Wiktor, J.; Kerssemakers, J.W.J.; Dekker, C. Direct imaging of the circular chromosome in a live bacterium. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, B.G. Distinct penicillin binding proteins involved in the division, elongation, and shape of Escherichia coli K12. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1975, 72, 2999–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, B.G.; Pardee, A.B. Penicillin-binding proteins and cell shape in E. coli. Nature 1975, 254, 516–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, N.A.; Orr, D.; Ross, G.W.; Boulton, M.G. Affinities of penicillins and cephalosporins for the penicillin-binding proteins of Escherichia coli K-12 and their antibacterial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1979, 16, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Modugno, E.; Erbetti, I.; Ferrari, L.; Galassi, G.; Hammond, S.M.; Xerri, L. In vitro activity of the tribactam GV104326 against gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1994, 38, 2362–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernabeu-Wittel, M.; García-Curiel, A.; Pichardo, C.; Pachón-Ibáñez, M.E.; Jiménez-Mejías, M.E.; Pachón, J. Morphological changes induced by imipenem and meropenem at sub-inhibitory concentrations in Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin Microbiol Infect 2004, 10, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.J.; Kropp, H. Differences in mode of action of (β-lactam antibiotics influence morphology, LPS release and in vivo antibiotic efficacy. Journal of Endotoxin Research 1996, 3, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pedro, M.A.; Donachie, W.D.; Höltje, J.-V.; Schwarz, H. Constitutive Septal Murein Synthesis in Escherichia coli with Impaired Activity of the Morphogenetic Proteins RodA and Penicillin-Binding Protein 2. J Bacteriol 2001, 183, 4115–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumita, Y.; Fukasawa, M.; Okuda, T. Comparison of two carbapenems, SM-7338 and imipenem: affinities for penicillin-binding proteins and morphological changes. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1990, 43, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalhoff, A.; Nasu, T.; Okamoto, K. Target affinities of faropenem to and its impact on the morphology of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Chemotherapy 2003, 49, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horii, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Sato, K.; Ichiyama, S.; Ohta, M. An in-vitro study of carbapenem-induced morphological changes and endotoxin release in clinical isolates of gram-negative bacilli. J Antimicrob Chemother 1998, 41, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumalsamy, H.; Jung, M.Y.; Hong, S.M.; Ahn, Y.-J. Growth-Inhibiting and morphostructural effects of constituents identified in Asarum heterotropoides root on human intestinal bacteria. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, W.J.; Webb, M. Effect of folic acid analogues on growth and cell division of nonexacting microorganisms. J Bacteriol 1956, 71, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushnie, T.P.T.; O’Driscoll, N.H.; Lamb, A.J. Morphological and ultrastructural changes in bacterial cells as an indicator of antibacterial mechanism of action. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 4471–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, T.S.J.; Shelton, A.; Greenwood, D. The response of Escherichia coli to ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin. Journal of Medical Microbiology 1987, 23, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Sun, G.W.; Chua, K.L.; Gan, Y.-H. Modified Virulence of Antibiotic-Induced Burkholderia pseudomallei Filaments. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005, 49, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uphoff, S.; Reyes-Lamothe, R.; Garza de Leon, F.; Sherratt, D.J.; Kapanidis, A.N. Single-molecule DNA repair in live bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 8063–8068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.C.; Uphoff, S. Single-molecule imaging of LexA degradation in Escherichia coli elucidates regulatory mechanisms and heterogeneity of the SOS response. Nat Microbiol 2021, 6, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Riveri, S.; Broughton, J.; McVey, A.; Pilizota, T.; Scott, M.; El Karoui, M. Growth-dependent heterogeneity in the DNA damage response in Escherichia coli. Mol Syst Biol 2022, 18, e10441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebicki, J.M.; James, A.M. The Preparation and Properties of Spheroplasts of Aerobacter aerogenes. Journal of General Microbiology 1960, 23, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errington, J. L-form bacteria, cell walls and the origins of life. Open Biol 2013, 3, 120143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, E.J.; Hoischen, C.; Gumpert, J. Bacterial L-forms. Adv Appl Microbiol 2009, 68, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, R.; Kawai, Y.; Errington, J. General principles for the formation and proliferation of a wall-free (L-form) state in bacteria. eLife 2014, 3, e04629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errington, J. Cell wall-deficient, L-form bacteria in the 21st century: a personal perspective. Biochem Soc Trans 2017, 45, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Lo, K.; Ojkic, N.; Stephens, R.; Scherer, N.F.; Dinner, A.R. Mechanical feedback promotes bacterial adaptation to antibiotics. Nat. Phys. 2021, 17, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojkic, N.; Serbanescu, D.; Banerjee, S. Antibiotic Resistance via Bacterial Cell Shape-Shifting. mBio 2022, 13, e00659–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojkic, N.; Serbanescu, D.; Banerjee, S. Surface-to-volume scaling and aspect ratio preservation in rod-shaped bacteria. eLife 2019, 8, e47033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojkic, N.; Banerjee, S. Bacterial cell shape control by nutrient-dependent synthesis of cell division inhibitors. Biophysical Journal 2021, 120, 2079–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Nonejuie, P.; Munguia, J.; Hollands, A.; Olson, J.; Dam, Q.; Kumaraswamy, M.; Rivera, H.; Corriden, R.; Rohde, M.; et al. Azithromycin Synergizes with Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides to Exert Bactericidal and Therapeutic Activity Against Highly Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacterial Pathogens. EBioMedicine 2015, 2, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, H.; Younis, W.; Ezzat, H.G.; Peters, C.E.; AbdelKhalek, A.; Cooper, B.; Pogliano, K.; Pogliano, J.; Mayhoub, A.S.; Seleem, M.N. Bacteriological profiling of diphenylureas as a novel class of antibiotics against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Seyedsayamdost, M.R. The Polyene Natural Product Thailandamide A Inhibits Fatty Acid Biosynthesis in Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 4247–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Heidary, D.K.; Zhang, Z.; Richards, C.I.; Glazer, E.C. Bacterial Cytological Profiling Reveals the Mechanism of Action of Anticancer Metal Complexes. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2018, 15, 3404–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, N.A.; Seif, Y.; Tsunemoto, H.; Poudel, S.; Meehan, M.; Szubin, R.; Olson, C.; Rajput, A.; Alarcon, G.; Lamsa, A.; et al. Characterizing the response of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 to azithromycin in multiple in vitro growth conditions 2020. [CrossRef]

- Araújo-Bazán, L.; Ruiz-Avila, L.B.; Andreu, D.; Huecas, S.; Andreu, J.M. Cytological Profile of Antibacterial FtsZ Inhibitors and Synthetic Peptide MciZ. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, J.M.; Huecas, S.; Araújo-Bazán, L.; Vázquez-Villa, H.; Martín-Fontecha, M. The Search for Antibacterial Inhibitors Targeting Cell Division Protein FtsZ at Its Nucleotide and Allosteric Binding Sites. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Healt Organization WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2017 2017.

- Di Bella, S.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Maraolo, A.E.; Viaggi, V.; Luzzati, R.; Bassetti, M.; Luzzaro, F.; Principe, L. Resistance to ceftazidime/avibactam in infections and colonisations by KPC-producing Enterobacterales: a systematic review of observational clinical studies. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2021, 25, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, M.S.; Gigante, V.; Sati, H.; Paulin, S.; Al-Sulaiman, L.; Rex, J.H.; Fernandes, P.; Arias, C.A.; Paul, M.; Thwaites, G.E.; et al. Analysis of the Clinical Pipeline of Treatments for Drug-Resistant Bacterial Infections: Despite Progress, More Action Is Needed. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 66. [CrossRef]

- Geneva: World Health Organization WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: bacterial pathogens of public health importance to guide research, development and strategies to prevent and control antimicrobial resistance. 2024.

- Htoo, H.H.; Brumage, L.; Chaikeeratisak, V.; Tsunemoto, H.; Sugie, J.; Tribuddharat, C.; Pogliano, J.; Nonejuie, P. Bacterial Cytological Profiling as a Tool To Study Mechanisms of Action of Antibiotics That Are Active against Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2019, 63, 10.1128–aac.02310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coram, M.A.; Wang, L.; Godinez, W.J.; Barkan, D.T.; Armstrong, Z.; Ando, D.M.; Feng, B.Y. Morphological Characterization of Antibiotic Combinations. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 8, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaño, E.T.; Nideffer, J.F.; Sugie, J.; Enustun, E.; Shapiro, A.B.; Tsunemoto, H.; Derman, A.I.; Pogliano, K.; Pogliano, J. Bacterial Cytological Profiling Identifies Rhodanine-Containing PAINS Analogs as Specific Inhibitors of Escherichia coli Thymidylate Kinase In Vivo. Journal of Bacteriology 2021, 203, 10.1128–jb.00105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonejuie, P.; Trial, R.M.; Newton, G.L.; Lamsa, A.; Ranmali Perera, V.; Aguilar, J.; Liu, W.-T.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Pogliano, J.; Pogliano, K. Application of bacterial cytological profiling to crude natural product extracts reveals the antibacterial arsenal of Bacillus subtilis. J Antibiot 2016, 69, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Tsivkovski, R.; Pogliano, J.; Tsunemoto, H.; Nelson, K.; Rubio-Aparicio, D.; Lomovskaya, O. Intrinsic Antibacterial Activity of Xeruborbactam In Vitro: Assessing Spectrum and Mode of Action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 66, e00879-22. [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Forrest, S.; Warne, B.; Maes, M.; Baker, S.; Dougan, G.; Bartholdson Scott, J. High-Content Imaging to Phenotype Antimicrobial Effects on Individual Bacteria at Scale. mSystems 6, e00028-21. [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.C.; Pullen, K.M.; Olson, M.C.; McNellis, M.E.; Richardson, I.; Hu, S.; Larkins-Ford, J.; Wang, X.; Freundlich, J.S.; Ando, D.M.; et al. Morphological profiling of tubercle bacilli identifies drug pathways of action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 18744–18753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.; Ames, L.; Baldin, V.P.; Butts, A.; Henry, K.J.; Quach, D.; Sugie, J.; Pogliano, J.; Parish, T. An arylsulphonamide that targets cell wall biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis 2024, 2024.07.22.604653. [CrossRef]

- López-Jiménez, A.T.; Brokatzky, D.; Pillay, K.; Williams, T.; Güler, G.Ö.; Mostowy, S. High-content high-resolution microscopy and deep learning assisted analysis reveals host and bacterial heterogeneity during Shigella infection. eLife 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, B.J.; Steed, M.E.; Ireland, C.E.; Tran, T.T.; Nonejuie, P.; Murray, B.E.; Rose, W.E.; Sakoulas, G.; Pogliano, J.; Arias, C.A.; et al. Defining Daptomycin Resistance Prevention Exposures in Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium and E. faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 5253–5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalla, G. Using Bacterial Cytological Profiling to Study the Interactions of Bacteria and the Defense Systems of Multicellular Eukaryotes, University of California San Diego: USA, 2020.

- Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Kavanagh, A.M.; Elliott, A.G.; Zhang, B.; Ramu, S.; Amado, M.; Lowe, G.J.; Hinton, A.O.; Pham, D.M.T.; Zuegg, J.; et al. The antimicrobial potential of cannabidiol. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakoulas, G.; Nonejuie, P.; Kullar, R.; Pogliano, J.; Rybak, M.J.; Nizet, V. Examining the Use of Ceftaroline in the Treatment of Streptococcus pneumoniae Meningitis with Reference to Human Cathelicidin LL-37. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 2428–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, A.-B.; Sidarta, M.; Abdelmesseh Nekhala, I.; Marinho Righetto, G.; Arshad, A.; Wenzel, M. Dissecting antibiotic effects on the cell envelope using bacterial cytological profiling: a phenotypic analysis starter kit. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e03275–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serbanescu, D.; Ojkic, N.; Banerjee, S. Cellular resource allocation strategies for cell size and shape control in bacteria. The FEBS Journal 2022, 289, 7891–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuin, C.; Goodman, A.; Chernyshev, V.; Kamentsky, L.; Cimini, B.A.; Karhohs, K.W.; Doan, M.; Ding, L.; Rafelski, S.M.; Thirstrup, D.; et al. CellProfiler 3.0: Next-generation image processing for biology. PLOS Biology 2018, 16, e2005970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, S.; Kutra, D.; Kroeger, T.; Straehle, C.N.; Kausler, B.X.; Haubold, C.; Schiegg, M.; Ales, J.; Beier, T.; Rudy, M.; et al. ilastik: interactive machine learning for (bio)image analysis. Nat Methods 2019, 16, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsunsky, I.; Millard, N.; Fan, J.; Slowikowski, K.; Zhang, F.; Wei, K.; Baglaenko, Y.; Brenner, M.; Loh, P.; Raychaudhuri, S. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat Methods 2019, 16, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamsa, A.; Lopez-Garrido, J.; Quach, D.; Riley, E.P.; Pogliano, J.; Pogliano, K. Rapid Inhibition Profiling in Bacillus subtilis to Identify the Mechanism of Action of New Antimicrobials. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 2222–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschede, S.R.; Salam, R.; Gneid, H.; Busschaert, N. Bacterial cytological profiling identifies transmembrane anion transport as the mechanism of action for a urea-based antibiotic. Supramolecular Chemistry 2022, 34, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducret, A.; Quardokus, E.M.; Brun, Y.V. MicrobeJ, a tool for high throughput bacterial cell detection and quantitative analysis. Nat Microbiol 2016, 1, 16077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaño, E.T.; Nideffer, J.F.; Sugie, J.; Enustun, E.; Shapiro, A.B.; Tsunemoto, H.; Derman, A.I.; Pogliano, K.; Pogliano, J. Bacterial Cytological Profiling Identifies Rhodanine-Containing PAINS Analogs as Specific Inhibitors of Escherichia coli Thymidylate Kinase In Vivo. Journal of Bacteriology 2021, 203, 10.1128/jb.00105-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausen, R.; Robertson, B.E. Morpheus: A Deep Learning Framework for the Pixel-level Analysis of Astronomical Image Data. ApJS 2020, 248, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paintdakhi, A.; Parry, B.; Campos, M.; Irnov, I.; Elf, J.; Surovtsev, I.; Jacobs-Wagner, C. Oufti: An integrated software package for high-accuracy, high-throughput quantitative microscopy analysis. Mol Microbiol 2016, 99, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, T.M.A.; Lammers, M.G.; Zhou, M.; Sparks, I.L.; Rajendran, M.; Fang, D.; De Jesus, C.L.Y.; Carneiro, G.F.R.; Cui, Q.; Weibel, D.B. Small Molecule Chelators Reveal That Iron Starvation Inhibits Late Stages of Bacterial Cytokinesis. ACS Chem Biol 2018, 13, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa, E.R.; Kousha, A.; Tsunemoto, H.; Pogliano, J.; Licitra, C.; LiPuma, J.J.; Sakoulas, G.; Nizet, V.; Kumaraswamy, M. Azithromycin Exerts Bactericidal Activity and Enhances Innate Immune Mediated Killing of MDR Achromobacter xylosoxidans. Infectious Microbes & Diseases 2020, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wet, T.J.; Winkler, K.R.; Mhlanga, M.; Mizrahi, V.; Warner, D.F. Arrayed CRISPRi and quantitative imaging describe the morphotypic landscape of essential mycobacterial genes. eLife 2020, 9, e60083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B.; Schwan, M.; Thormann, K.M.; Graumann, P.L. Antibiotic Drug screening and Image Characterization Toolbox (A.D.I.C.T.): a robust imaging workflow to monitor antibiotic stress response in bacterial cells in vivo. F1000Res 2022, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Hoeksma, J.; Lubbers, R.J.M.; Siersma, T.K.; Hamoen, L.W.; den Hertog, J. Classification of antimicrobial mechanism of action using dynamic bacterial morphology imaging. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 11162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, K.J.; Stringer, C.; Lo, T.W.; Rappez, L.; Stroustrup, N.; Brook Peterson, S.; Wiggins, P.A.; Mougous, J.D. Omnipose: a high-precision morphology-independent solution for bacterial cell segmentation. Nat Methods 2022, 19, 1438–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistretta, M.; Cimino, M.; Campagne, P.; Volant, S.; Kornobis, E.; Hebert, O.; Rochais, C.; Dallemagne, P.; Lecoutey, C.; Tisnerat, C.; et al. Dynamic microfluidic single-cell screening identifies pheno-tuning compounds to potentiate tuberculosis therapy. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-sagheir, A.M.K.; Nekhala, I.A.; El-Gaber, M.K.A.; Aboraia, A.S.; Persson, J.; Schäfer, A.-B.; Wenzel, M.; Omar, F.A. Rational design, synthesis, molecular modeling, biological activity, and mechanism of action of polypharmacological norfloxacin hydroxamic acid derivatives. RSC Med. Chem. 2023, 14, 2593–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigert, M.; Schmidt, U. Nuclei instance segmentation and classification in histopathology images with StarDist 2022. [CrossRef]

- Weigert, M.; Schmidt, U.; Boothe, T.; Müller, A.; Dibrov, A.; Jain, A.; Wilhelm, B.; Schmidt, D.; Broaddus, C.; Culley, S.; et al. Content-aware image restoration: pushing the limits of fluorescence microscopy. Nat Methods 2018, 15, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks 2018. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Wu, K.; Pei, Z.; Weng, T.; Han, Q.; Meng, L.; Qian, X.; Xu, H.; Qiu, Z.; Li, Z.; et al. MLU-Net: A Multi-Level Lightweight U-Net for Medical Image Segmentation Integrating Frequency Representation and MLP-Based Methods. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 20734–20751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Uhlmann, V. Splinedist: Automated Cell Segmentation With Spline Curves. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI); 2021; pp. 1082–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Spahn, C.; Gómez-de-Mariscal, E.; Laine, R.F.; Pereira, P.M.; Von Chamier, L.; Conduit, M.; Pinho, M.G.; Jacquemet, G.; Holden, S.; Heilemann, M.; et al. DeepBacs for multi-task bacterial image analysis using open-source deep learning approaches. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru, E.; Hughes, H.V.; Brown, P.J.; Hall, E.; Tekkam, S.; Cava, F.; de Pedro, M.A.; Brun, Y.V.; VanNieuwenhze, M.S. In Situ Probing of Newly Synthesized Peptidoglycan in Live Bacteria with Fluorescent D -Amino Acids. Angew Chem Int Ed 2012, 51, 12519–12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, W.; Blanot, D.; de Pedro, M.A. Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2008, 32, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.D. The Selective Value of Bacterial Shape. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2006, 70, 660–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratford, J.P.; Edwards, C.L.A.; Ghanshyam, M.J.; Malyshev, D.; Delise, M.A.; Hayashi, Y.; Asally, M. Electrically induced bacterial membrane-potential dynamics correspond to cellular proliferation capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116, 9552–9557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prindle, A.; Liu, J.; Asally, M.; Ly, S.; Garcia-Ojalvo, J.; Süel, G.M. Ion channels enable electrical communication in bacterial communities. Nature 2015, 527, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza-Guerreiro, T.C.; Huan Bacellar, L.; Da Costa, T.S.; Edwards, C.L.A.; Tasic, L.; Asally, M. Membrane potential dynamics unveil the promise of bioelectrical antimicrobial susceptibility Testing (BeAST) for anti-fungal screening. mBio 2024, 15, e01302–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.; Stokes, J.M.; Cervantes, B.; Penkov, S.; Friedrichs, J.; Renner, L.D.; Collins, J.J. Cytoplasmic condensation induced by membrane damage is associated with antibiotic lethality. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Xie, R.; Ayyadhury, S.; Ge, C.; Gupta, A.; Gupta, R.; Gu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, G.; Kim, J.; et al. The multimodality cell segmentation challenge: toward universal solutions. Nat Methods 2024, 21, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bali, A.; Singh, S.N. A Review on the Strategies and Techniques of Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2015 Fifth International Conference on Advanced Computing & Communication Technologies; 2015; pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, C.; Wang, T.; Michaelos, M.; Pachitariu, M. Cellpose: a generalist algorithm for cellular segmentation. Nature Methods 2020 18:1 2020, 18, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- StarDist: Application of the deep-learning tool for phase-contrast cell images - 2020 - Wiley Analytical Science. Available online: https://analyticalscience.wiley.com/do/10.1002/was.000400090/ (accessed on Aug 1, 2024).

- THE ANALYSIS OF CELL IMAGES* - Prewitt - 1966 - Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb11715.x (accessed on Aug 1, 2024).

- Mendelsohn, M.L.; Kolman, W.A.; Perry, B.; Prewitt, J.M.S. Computer Analysis of Cell Images. Postgraduate Medicine 1965, 38, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianidou, S.; Brennan, C.; Nissen, S.B.; Kuwada, N.J.; Wiggins, P.A. SuperSegger: robust image segmentation, analysis and lineage tracking of bacterial cells. Molecular Microbiology 2016, 102, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, B.; Efstathiou, C.; Yue, H.; Draviam, V.M. Opportunities and challenges for deep learning in cell dynamics research. Trends in Cell Biology 2023, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.; Spangaro, A.; Lenartowicz, M.; Mattiazzi Usaj, M. From pixels to insights: Machine learning and deep learning for bioimage analysis. BioEssays 2024, 46, 2300114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osokin, A.; Chessel, A.; Salas, R.E.C.; Vaggi, F. GANs for Biological Image Synthesis. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017; pp. 2252–2261. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsborough, P.; Pawlowski, N.; Caicedo, J.C.; Singh, S.; Carpenter, A.E. CytoGAN: Generative Modeling of Cell Images 2017, 227645. [CrossRef]

- Cylke, C.; Si, F.; Banerjee, S. Effects of antibiotics on bacterial cell morphology and their physiological origins. Biochemical Society Transactions 2022, 50, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chessel, A.; Carazo Salas, R.E. From observing to predicting single-cell structure and function with high-throughput/high-content microscopy. Essays in Biochemistry 2019, 63, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.T.; Koh, J.L.Y.; Friesen, H.; Duffy, S.K.; Cox, M.J.; Moses, A.; Moffat, J.; Boone, C.; Andrews, B.J. Yeast Proteome Dynamics from Single Cell Imaging and Automated Analysis. Cell 2015, 161, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, C.L.; Esqueda, M.; Yu, J.-J.; Wall, G.; Romo, J.A.; Vila, T.; Chaturvedi, A.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L.; Wormley, F.; Hung, C.-Y. Development of an Imaging Flow Cytometry Method for Fungal Cytological Profiling and Its Potential Application in Antifungal Drug Development. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDiarmid, A.H.; Gospodinova, K.O.; Elliott, R.J.R.; Dawson, J.C.; Graham, R.E.; El-Daher, M.-T.; Anderson, S.M.; Glen, S.C.; Glerup, S.; Carragher, N.O.; et al. Morphological profiling in human neural progenitor cells classifies hits in a pilot drug screen for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Communications 2024, 6, fcae101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, E.; Kim, S.; Mohamad, S.; Huguet, S.; Shi, Y.; Cohen, A.; Piddini, E.; Carazo-Salas, R. Deep learning-enhanced morphological profiling predicts cell fate dynamics in real-time in hPSCs; 2021.

- Perlman, Z.E.; Slack, M.D.; Feng, Y.; Mitchison, T.J.; Wu, L.F.; Altschuler, S.J. Multidimensional Drug Profiling By Automated Microscopy. Science 2004, 306, 1194–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).