1. Introduction

The instability caused by COVID-19 gave way to a particularly complex scenario where organizations face the consequences of different armed conflicts worldwide. These conditions require constant change management and have reinforced interests in people-centered organizational factors. In that sense, employees’ mental health, specifically their emotional exhaustion, has acquired particular relevance in recent years (Lapalme et al., 2023; Santiago-Torner et al., 2023). Emotional exhaustion is a state of permanent resource deficit caused by excessive work demands, which is detrimental to the mental and physical health of employees and to business sustainability itself (Zhou et al., 2020).

Previous studies reveal that emotionally exhausted employees tend toward attitudes that, in addition to hindering performance and moral behavior (Lee et al., 2022), encourage absenteeism and an explicit desire to leave the job (Lee et al., 2021). Multiple investigations have explored the contexts where emotional exhaustion is attenuated. Some authors have reached the conclusion that social support derived from ethical leadership is associated with a supply of valuable resources and measures that prevent deterioration (Lee et al., 2021; Okpozo et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2020, 2022). Specifically, the conservation of resources (COR) theory supports this relationship as it specifies that individuals seek to acquire, protect, and extend their capabilities (Hobfoll et al., 2018).

Leadership, specifically ethical leadership, is a key situational factor in the organization as it strongly impacts subordinates. Ethical leadership has been defined from different points of view, but it usually describes the extent to which the leader’s behavior conforms to what is normatively appropriate. It is capable of transferring specific behaviors to employees that promote their well-being and are essential to face ethical dilemmas (Brown et al., 2005).

This management style seeks to persuade employees through an unusual, convincing, and apparently achievable message. Ethical dialogue has an impact on the quality of relationships and the final attitude of employees when accompanied by a proactive effort, by the leader, to influence based on normative criteria, (Zhou et al., 2020). In fact, Lee et al. (2021) go further by considering that the ethical leader has a strong capacity to influence employees emotionally as their interactions grow. These authors propose that the ethical leader is capable of regulating and nurturing the employees’ experience through a constant allocation of resources.

However, the role played by ethical leadership sparks a profound debate. The results of Feng et al. (2018); Miao et al. (2013); Mo et al. (2019); Stouten et al. (2013); establish that moral information excess can cause an ethical conflict in employees. They constantly feel judged, which weakens their motivation to actively participate in organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB) or to creatively improve their performance. Consequently, excessive interest in regulating the subordinate’s ethical behavior can trigger controlling behavior on the part of the leader and a process of moral distress that intensifies the employee’s consumption of personal resources.

Considering these opposing thoughts, this research introduces ethical leadership into the study of emotional exhaustion from a less-studied perspective that is neither linear nor necessarily positive. Actually, ethical behavior is voluntary in nature. This intentionality helps followers freely reproduce the behaviors of the ethical leader as they consider him or her an indisputably credible role model. That is, the nature of the relationship between leader and employee, in addition to being relevant, is developed in an environment of trust (Santiago-Torner, 2023a).

However, when social learning is linked to feelings of obligation, the fit between leader and employee stops relying on personal convictions, and ethics becomes a requirement (Stouten et al., 2013). In fact, learning and modeling processes are associated with the leader’s perspective of influencing employee behavior (De Hoogh & Den Hartog, 2008). Ethical leaders also encourage two-way communication and relationships based on active listening and benevolence. Therefore, when a strictly ethical proposal takes on excessive prominence, that flow of integrity overwhelms employees. When perceived as unreachable, the moral approach transforms individual behavior, neutralizing it or defining a scenario of obligation (Feng et al., 2018; Li et al., 2023).

At that point, employees may feel that the legitimacy of their values is being questioned. This perception of inequality and moral rejection can directly trigger attitudes of resignation and passivity (Mo et al., 2019) or, on the other hand, become a source of overcompensation, resulting in greater use of emotional energy that exhausts employees (Zhou et al., 2020).

Consequently, disproportionate stress would result from extensive effort and active investment of unreturned resources. The perceived moral obligation to adjust to the standards proposed by the ethical leader carries a strong psychological burden to avoid social disapproval (Ekberg et al., 2021). Thus, when the leader encourages employees to react ethically, from an intentional perspective that values integrity, it generates a normative understanding of ethical behavior that becomes an effective coping strategy to manage specific potential stressors (Zheng et al., 2015).

High moral intensity can imply that followers hide their emotions and motivation is driven towards excessive self-control. Under these conditions, the relationship between ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion is curvilinear. That is to say, ethical standards that are too high force followers to direct their efforts towards an environment of moral rigidity and low self-regulation, which prevents spontaneity (Feng et al., 2018). This supposed emotional suppression, supported by feelings of obligation, results in psychological exhaustion (Li et al., 2023).

Considering the latter, this research proposes that affective commitment is a mediating mechanism that explains the positive curvilinear relationship between ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion. Affective commitment is a psychosocial state that reflects the emotional identification of an individual toward his or her organization (Bouraoui et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019). In practice, there is an overlap between the affective and moral dimensions of commitment (González & Guillén, 2008). Therefore, a person who is permanently exposed to ethical demands and simultaneously has a deep emotional bond with the organization is likely to direct all his/her efforts toward readjusting the moral balance regarding the standard proposed by the leader.

Although affective commitment represents a positive attitude with a strong association with well-being, it is reasonable to think that this emotional balance and the psychological safety it entails may have a tipping point (Santiago-Torner et al., 2024). In fact, ethical idealization becomes an unattainable goal (Feng et al., 2018). Excessive emphasis on a leadership model with unconvincing particularities implies a permanent change of feelings that can separate an individual from his/her emotional responses to the point of wanting to evade them (Kong & Jeon, 2018).

Surely, affective commitment helps build a feeling of responsibility and task ownership that exceeds the scope of the common role (Bouraoui et al., 2019; Cohen & Caspary, 2011; Jiang & Johnson, 2018). This enthusiasm may conflict with the moral vision of the ethical leader without an equity perspective. This lack of consideration, when able to influence the employees’ mood, forces them to search for new emotional resources, leading to initial weakening and subsequent emotional exhaustion (Matthews & Edmondson, 2020). Almost certainly, restoring the status quo is only possible through an ethical leader consistent with his or her role, who maintains close communications with employees and balances managerial and personal aspects.

Therefore, this study aims to analyze the influence of ethical leadership on emotional exhaustion, considering the mediating role of affective commitment.

1.1. Ethical Leadership and Emotional Exhaustion

The buffering effect of ethical leadership on emotional exhaustion has been widely explored (Lee et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020, 2022). Most authors use the COR theory to justify this relationship. That is, ethical leaders become a source of resources, such as guidance, trust, clarity of functions, or fair treatment, which are central characteristics to reduce stress and the perception of uncertainty (Zheng et al., 2015).

In fact, ethical leaders promote an interpretation of work in accordance with certain normative behaviors whose main objectives are morality and condemnation of unethical behavior (Lukacik & Bourdage, 2019; Okpozo et al., 2017). Therefore, ethical leaders strive to maintain constant balance and ensure that their moral tendencies do not become an obligation (De Hoogh & Den Hartog, 2008). From this perspective, a work environment excessively focused on moral behaviors can be perceived as criticism and frustrate employees. In other words, employees consider that leaders who are too rigid in their ethical vision underestimate their moral effort, and this unattainable paradigm causes an emotional rupture between the two (Stouten et al., 2013).

Ethical leaders are characterized by strong willingness when it comes to transferring moral standards, which can be explained through the theory of social learning (Bandura, 1985). This conceptual assumption maintains that individuals assimilate certain behaviors when they pay attention to a person who is considered a role model (Santiago-Torner, 2023a). However, imitating a behavior is not necessarily intentional in nature and is far from obligatory. When followers feel questioned, they may decide to restore the moral balance through behavior that goes beyond their convictions. This feeling of obligation becomes a demand that deteriorates their psychological resources. Actually, the desire to neutralize a supposed moral difference involves a series of forced involuntary reactions that require a higher expenditure of emotional energy, and this context of loss leads to exhaustion (Lee & Huang, 2019).

In this sense, the inability to act according to internalized and previously accepted values determines a conditional pattern of demand that stresses followers and causes a high perception of anguish (Fumis et al., 2017). When ethical leaders prioritize trust relationships, a marked sense of dependency is established between them and their followers, which mitigates emotional exhaustion. However, trust goes much further because it needs to be nourished with beliefs and interaction (Chughtai et al., 2015). The moment communication is in only one direction, it becomes dysfunctional and breaks the previously established trust, which usually induces rigidity and emotional exhaustion (Li et al., 2023).

A moral scope that is too strict supposes that followers contain their emotional state. The relationship between ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion is no longer linear and positive under these circumstances. Sustained emotional repression, through a feigned behavioral model, leads to emotional exhaustion (Chi & Liang, 2013; Jahanzeb & Fatima, 2018). Indeed, when followers lose the ability to express what they feel without feeling rejection or obligation, they lose the ability to act in accordance with their values and enter a spiral where acceptance depends on restrictions, leading to emotional exhaustion.

Consequently, we propose Hypothesis 1. Ethical leadership is significantly related to emotional exhaustion through a curvilinear pattern

1.2. Mediating Role of Affective Commitment

The social exchange theory insists on intangible resources and their long-term importance (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). This theory maintains that when individuals feel supported, they reciprocate through positive work behaviors. In this sense, Brown et al. (2005) indicate the strong association that exists between ethical leadership and social exchange.

Given this relationship, it is logical to think that employees perceive ethical leaders as trustworthy people they can turn to under any circumstance. Therefore, this leadership style gives followers the idea that social exchange, in addition to being possible, is necessary as part of continuous feedback (Loi et al., 2015). Furthermore, social exchange research considers affective commitment an intangible resource resulting from the interaction between leaders and followers. Meaning that it is a consequence of the responsibility and concern of leaders for employees and that it simultaneously impacts organizational goals (Brown & Treviño, 2014). In this direction, the moral facet of ethical leaders dynamically transmits aspects related to individual integrity, which deliberately seeks phases of interaction and feedback in both directions (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Loi et al., 2015; Santiago-Torner & Muriel-Morales, 2023).

Employees perceive this interest as an organizational effort to satisfy their socio-emotional needs. Actually, the supervisors’ inclinations are integrated with the organization’s vision of global support. Therefore, it is expected for ethical leadership to relate positively to the followers’ affective commitment. The presumed proximity of the leader and the sincerity transmitted with their concern for employees and their closest circle give rise to affective, intentional, and genuine responses, which are far from obligatory (Bouraoui et al., 2019).

Ethical leaders probably transmit certain behaviors that followers assimilate when perceived as credible. This moral identity establishes behavioral models that reinforce affective commitment to the organization. Moral identity is a set of moral traits and relationships between them that define the moral personality of an individual (Loi et al., 2015). Therefore, the shared moral approach, meaning the moral articulation between leader and employee, facilitates an equitable regulation of the resources used at work. Furthermore, moral adjustment, when consistent with the expectations of both sides, keeps emotional exhaustion away from followers (Yurtkoru & Ebrahimi, 2017). In fact, a strong moral identity guides affective commitment and prevents this psychological state from stimulating unethical behaviors whose sole intention is to contribute to organizational goals. That is, moral identity acts as an emotional regulator (Cui et al., 2021).

However, when leaders convey an excessive and unreasonable ethical discourse, instead of reinforcing employee behavior, it can lead to a series of psychological mechanisms and pretexts leading to moral conformity and possibly apathy (Mo et al., 2019). On the other hand, when difficult ethical demands are received by an emotionally committed employee, either committed to the organization or the leader, they can lead to a state of overcompensation that alters the direction of resources, and this unexpected energy expenditure may emotionally exhaust employees (Wojdylo et al., 2017). When communication and exchange of perspectives occur in a work climate where followers feel emotionally pressured and less psychologically safe, ethical leadership loses its benefits, and its relationship with emotional exhaustion acquires a convex pattern. Psychological safety defines the degree of individual perception about the risk involved in establishing an interpersonal relationship. Therefore, it multiplies in environments characterized by trust and strong socio-emotional protection (Zhou & Chen, 2021).

Therefore, the desire to reproduce a type of behavior with such high ethical standards forces followers to make excessive efforts and to constantly modify their emotional routines until feeling unprotected (Feng et al., 2018). In this sense, although affective commitment relates organizational goals to the individual’s key values, it ceases to be a resource when the employee’s perspective moves away from his or her own emotional self-regulation and focuses on resembling the leader’s ethical approach. This emotional readjustment contributes to exhaustion because it exceeds self-control and becomes an excessive demand (Kong & Jeon, 2018). The COR theory specifies that adhering to specific rules proposed by the organization requires employees to do emotional work, which exhausts their psychological resources (Matthews & Edmondson, 2020). The number of resources invested depends on the intensity of the emotional work, and the desire to not break the rules or to get closer to an ethical ideal involves a series of constant behavioral modifications that lead to emotional exhaustion.

Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 2. Affective commitment mediates the positive relationship between ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Research design is quantitative, transversal, non-experimental, and correlational between at least two variables, in a defined environment (Sánchez Flores, 2019).

The sample consists of 448 employees who work in the Colombian electrical sector. Specifically in six companies with offices in Bogotá, Cali, Medellín, Manizales, and Pereira. The sampling method is probabilistic, using clusters to include the country’s main cities, with a confidence level of 95%. STATS statistical program is used for this calculation. The response rate was 100%. Regarding gender, 175 (39%) participants were women, and 273 (61%) were men. The average age is 37.18 years (SD = 10.059; range: 20-69). Three hundred sixty-four employees have permanent contracts (81.25%), and 84 have temporary work contracts (18.75%). Mean seniority is 13.06 years (SD = 8.82; range: 0-38 years). Regarding jobs, 86.6% (308) are analysts, 8.9% (40) hold intermediate jobs, and 4.5% (20) are managers. 100% of those surveyed have university studies, and 57.4% (257) have graduate studies. 42% (188) do not have children.

The project was presented to the Colombian electrical sector mid-2021 at its community action meeting. The six participating organizations were intentionally selected for a reliable national vision of the analyzed sector. The main criterion used was to have representation by the most important departments of the country (Cundinamarca, Valle del Cauca, Antioquía, Caldas, and Risaralda) and their capital cities. The researcher initially contacted 18 companies filtered by city and relevance. Organization relevance was measured through market share and number of employees. During a second phase, confidentiality agreements were signed, and the following documents were sent: voluntary consent and waiver, data protection, and objectives presentation. The questionnaire was supervised by experts and sent to the participants online using the Google Forms tool. All the research was subject to an ethics committee at the end of 2021.

The time estimated to complete the survey was about thirty-five minutes. Processes were conducted on separate days. The leading researcher presented the most important objectives of the research online for about five minutes each day. Additionally, he clarified the advantage of reading the questions carefully for reflective answers. Finally, the rights of respondents were emphasized, highlighting the anonymity of the data collected and the non-discrimination of participants.

2.2. Ethical Aspects

This research project was evaluated on July 21, 2021, by the ethics committee of the University of Vic - Central University of Catalonia (Internal code: 170/2021). Its conclusions certify the following: (1) The study meets the necessary suitability requirements in relation to objectives and methodological design. (2) Ethical requirements regarding the obtention of informed consent and aspects related to confidentiality are met. (3) The researcher’s competence and available means are appropriate for conducting the study without any apparent risk as it is non-experimental. In fact, informed consent is handled considering the regulation of good scientific practices proposed by Spain’s Ministry of Science and Innovation.

2.3. Measures

Unless indicated otherwise, participants responded to all items using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree and 6 = Strongly agree).

Control Variables: Seniority and gender are used as control variables. Employees who are highly adaptive to organizational idiosyncrasies may be more resilient and committed. Survey participants were asked to indicate how long they had worked in the same company using a scale with 1 year as the minimum to measure seniority. Gender was coded as 0 for men and 1 for women.

Ethical Leadership: Ethical leadership was measured using the ten items developed by Brown et al. (2005). For example: “My leader can be trusted.” The Cronbach’s Alpha obtained by the original scale was 0.94, using a seven-point Likert scale. This research obtained a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.92. Institutional leadership and its relationship with ethical attitudes are evaluated as a function of the leaders’ behaviors, interactions, and communications to transmit trust to followers. Applied by Santiago-Torner (2023c) using a 6-point scale and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.92.

Affective Commitment: Affective commitment was measured using the six items proposed by Meyer et al. (1993). For example: “This organization has great personal meaning for me.” The Cronbach’s Alpha obtained by the original scale was 0.82, using a seven-point scale ranging from “totally agree” to “totally disagree.” This research obtained a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.86. The emotional relation and proximity of employees to the organization are assessed. Used by Santiago-Torner (2023a) with a Cronbach’s Alpha of .86.

Emotional Exhaustion: Emotional exhaustion was measured using the five items proposed by Schaufeli et al. (1996). The same six-point scale was used. For example: “I am emotionally exhausted at my job.” The Cronbach’s Alpha obtained by the original scale was 0.85, using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “totally agree” to “totally disagree.” This research obtained a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.90. The effect of the workload on individuals’ emotional resources is evaluated. Used by Santiago-Torner (2023b) with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.90.

2.4. Aggregation Statistics

The model used is a simple mediation tested with an analysis based on regressions. The Confidence Interval (CI) is 95%, and the number of bootstrapping samples is 10,000. This statistical method calculates each equation independently. The first model approximates the independent variable to the mediator and the different covariables. The second model adjusts the relationship between the covariables, the independent and the mediator variables with respect to the dependent variable. Macro PROCESS (Hayes, 2018) of the SPSS statistical program is used for this end. The data was checked in terms of linearity, normality, and multicollinearity issues before the mediation analysis. Kurtosis, skewness, and Mahalanobis distance scores were examined to determine linearity and normality (Aguinis et al., 2017). Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) and Condition Index methods were used to determine multicollinearity issues. Condition Index values must be below 30 and VIF values below 10 to meet the assumption of normality. No multicollinearity issues were identified, and the data was normally distributed.

4. Discussion

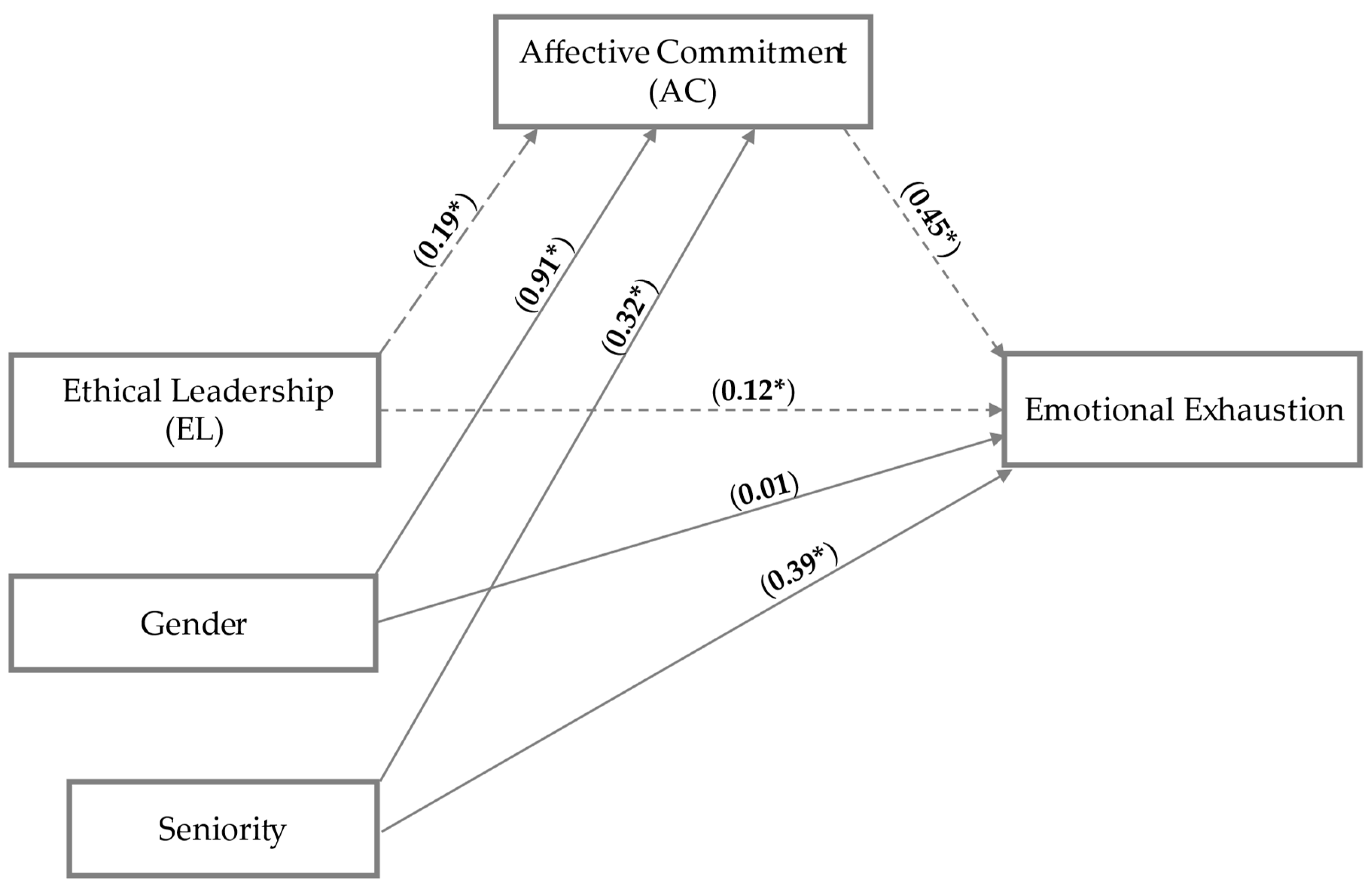

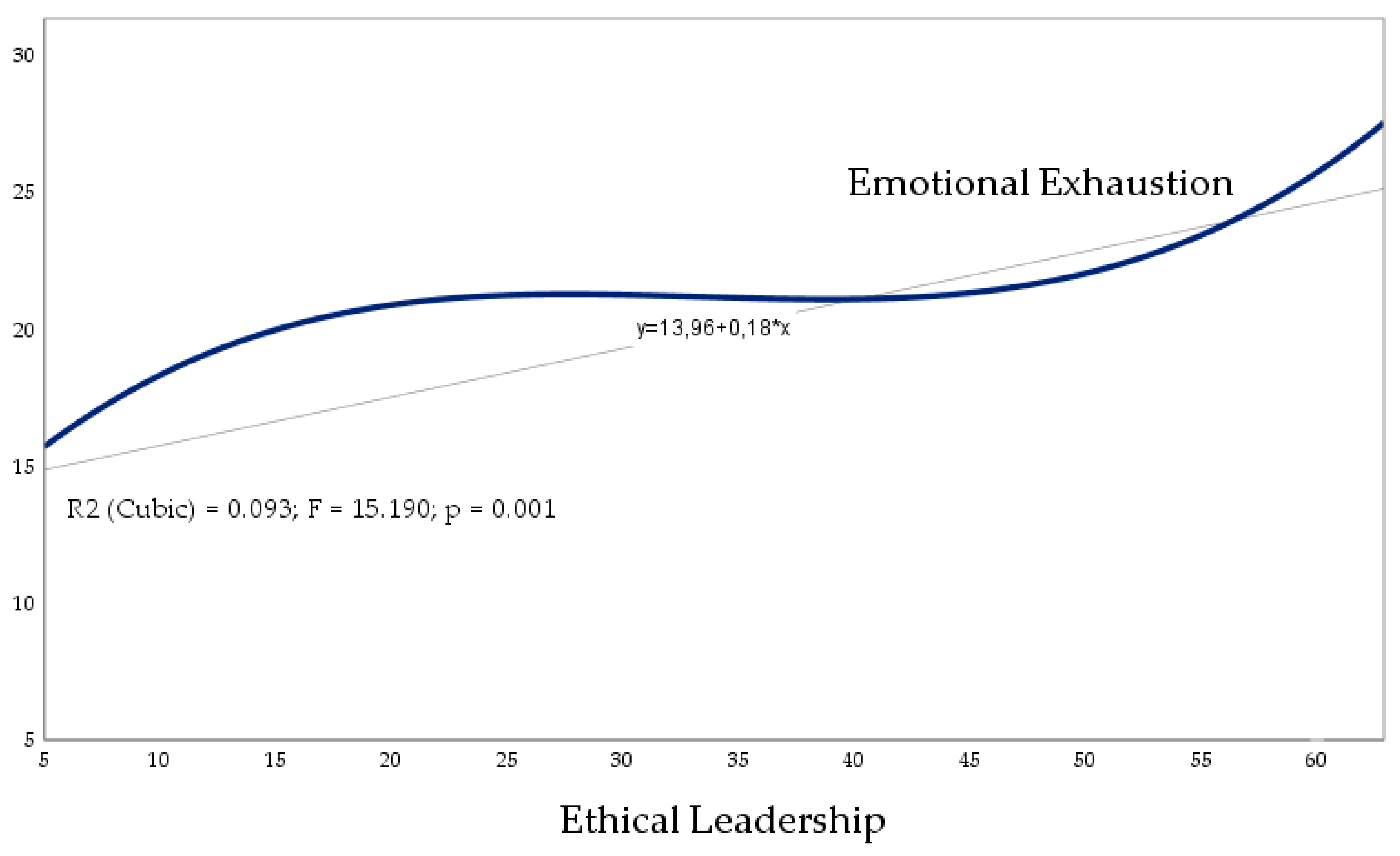

The main objective of this research is to analyze the relationship between ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion, considering the mediating role of affective commitment. Ethical leadership influences followers from opposite perspectives, representing a curvilinear relationship with emotional exhaustion (Hypothesis 1;

Figure 2). This result is possibly one of the first to establish a non-linear relationship between ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion.

Ethical leadership is a factor that can buffer the stress perceived by followers. Therefore, it acts as a resource supporting employees’ coping strategies to prevent conflicts from hindering their ability to react, and to prevent negative aspects from outweighing positive ones. From this perspective, ethical leaders care about their subordinates by facilitating positive emotional experiences, such as dignity, respect, or autonomy. That is, they place followers in a position where they can experience intense feelings of competence and self-determination (Zhou et al., 2020, 2022). Additionally, an honest approach prevents employees from wasting resources and energy by over-controlling their emotions (Lee et al., 2021). In this sense, strong compatibility is established between the role of ethical leadership and the effective reallocation of individual resources to avoid emotional exhaustion. Useful sources of motivation replenish employees’ resources and help their responses move away from exhaustion (Hobfoll et al., 2018).

On the other hand, moral values and ethical convictions are not sustainable when supported by feelings of obligation. Ethical leaders are distinguished by fair and moral behavior. Their nature persuades followers by being trustworthy, compassionate, empathetic, and honest, thus becoming a role model (Santiago-Torner, 2023a). Therefore, followers feel belittled when the leader’s character is excessively oriented toward moral and legal norms, renouncing his/her own essence (Feng et al., 2018; Stouten et al., 2013). From this perspective, the relationship between leader and follower can be perceived under dichotomous approaches of reward or punishment. The theoretical ethical insufficiency of subordinates is transformed into a moral obligation to restore a vision, under conditions of equality with the leader, which entails a permanent cognitive burden to prevent disapproval (Ekberg et al., 2021). Indeed, the feeling of pressure and the disproportionate sense of obligation lead to a continuous introjected motivation that exceeds individual cognitive resources, and weakens the self-regulation capacity to manage negative emotions correctly (Li et al., 2023). Introjected motivation seeks a balance between external demands and an unmet internal need (Flatau-Harrison et al., 2021; Gagné & Deci, 2005). This hypothetical balance has an impact on personal self-esteem. When self-regulation is insufficient due to forced behavior, employees enter a spiral of loss of resources that affects their emotional health (Zhou et al., 2020).

The need for approval contradicts the basic psychological conditions of autonomy, relationship, and competence (Gagné & Deci, 2005). Therefore, a feigned display of emotions dramatically increases emotional exhaustion (Lee et al., 2021). Finally, irrational ethical standards establish a point of moral rigidity so high that it prevents spontaneity, one of the critical traits defining ethical leaders (Feng et al., 2018).

Verification of Hypothesis 2 establishes an indirect relationship between ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion. Affective commitment develops feelings of obligation and extra-role involvement in work activities (Guohao et al., 2021). In fact, employees with high affective commitment have the main objective of staying in the organization. They show a remarkable willingness towards the guidelines defined by the leader due to this indispensable condition (Asif et al., 2019). This natural inclination requires the worker to make cognitive and emotional investments.

Matthews & Edmondson (2020) specify that perceived organizational support attenuates excessive emotional tension and increases affective commitment. However, affective commitment can conflict with the moral principles set forth by an ethical leader. The desire to help the employer causes a strong tension between the leader’s ethical standards and amoral activities considered beneficial for organizational growth (Cullinan et al., 2008; Matherne et al., 2018). Therefore, followers may feel overwhelmed wanting to imitate the moral management proposed by the ethical leader. The socio-emotional exchange between the two suggests that employees with high affective commitment have behaviors distant from moral disengagement (Yurtkoru & Ebrahimi, 2017). This one-way organizational identification confuses followers and can also exhaust them emotionally. That is, loyal employees are subject to greater pressure to direct their moral reasoning and emotions to achieve a balanced relationship with the leader (Park et al., 2023).

Furthermore, when ethical leaders surpass certain moral limits, followers may feel that their freedom is being restricted and even that their system of ideas is being questioned. Therefore, the leaders’ pretensions can act as a demand in such a way that supporting him or her represents a continuous overload requiring constant emotional modifications (Kong & Jeon, 2018). Indeed, theoretical moral differences and intrinsic desire from the follower to reduce them pose a state of imbalance and uncertainty due to an excess of expectations leading to role stress. This type of stress appears through conflict between multiple roles or when work demands excessively overload employees and destabilize them emotionally (Washburn et al., 2021). In fact, previous research has shown that role stress is a critical element directly related to emotional exhaustion and low job satisfaction (Washburn et al., 2021; Zhao & Jiang, 2022). When individuals feel questioned, they hide their emotions as environmental characteristics and pressure affect their behavior (Zhao & Jiang, 2022). This emotional confusion becomes a vulnerability factor for followers, increasing their stress and overloading their role, when they perceive that ethical approaches exceed their available resources. Therefore, the mid-term response may be a state of psychological overstimulation that emotionally exhausts them (Yurtkoru & Ebrahimi, 2017).

Finally, another interesting result of this study that is not linked to any of its hypotheses is that job seniority is significantly linked to emotional exhaustion and affective commitment.

The sector analyzed, primarily public, is characterized by solid job stability. This continuity provides professionals with training plans and promotion opportunities. Therefore, there is likely a relationship between seniority in the organization and increasing job responsibility. In fact, management and intermediate positions are reached with an average professional experience of about seven years, confirming this initial perception. In this sense, employees can feel grateful to the organization, and this context of gratitude can lead to compensatory extra-role behaviors driven by an ethical management style that does not limit the amount of energy and resources used, until exhausting them. These results are consistent with research conducted by Vargas et al. (2014). These authors conclude that job seniority, when linked to strong organizational identification, can lead to a greater consumption of energy and resources. This assumption fits with the mediating effect of affective commitment demonstrated in this research.

4.1. Practical Implications and Limitations

The possible practical implications follow. First, the findings are relevant because they establish a new relationship pattern between ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion that is different from those described so far. Ethical leaders can affect followers’ emotions in two directions: positively and negatively. This means that the interaction scheme between the two is curvilinear.

Therefore, ethical leadership does not always impact employee well-being positively. In this sense, the development of new leaders is not contingent on evaluating specific personality traits or considering integrity critical for the adequate transfer of an ethical perspective. That is to say, the relationship between leader and follower cannot ignore the importance of human beings and their differential characteristics.

Second, a horizontal leader can more easily convey an ethical discourse by sharing and understanding different emotional states. An empathetic line of leadership can lead to adaptive results that improve the emotional well-being of followers. Recognizing one’s weaknesses and the employees’ efforts to adjust to organizational values can make a difference, and prevent followers from feeling overwhelmed by a supposed moral difference that is difficult to bridge. Ultimately, respect does not have to be accompanied by absolute submission but rather by valuable reflection by both parties.

Third, ethical leadership can only thrive in a context where the culture reflects the organization’s specific ethical intentions. Furthermore, if the ethical message remains a strong declaration of intentions without facts to validate it, it will likely generate the opposite effect. Ethical language can be perceived from skeptical positions in emerging countries. Therefore, it needs to have practical consequences (Páez & Salgado, 2016).

Fourth, the results of this research determine that ethical leadership has moral limits. When such are surpassed, its effect on emotional exhaustion changes direction and favors emotional exhaustion instead of acting negatively against it. The Eastern assumption that going too far has the same negative effects as not going far enough (Feng et al., 2018) is likely to apply to the curvilinear effect of ethical leadership. However, this study adheres to the assumption that Western organizations can change this negative approach. In other words, it is possible to shorten the hierarchical distance between leader and follower, to feed their competencies through positive feedback, and to prevent through trust relationships the moral rigidity that leads to emotional exhaustion (Santiago-Torner, 2023a).

Finally, accessible, ethical leadership that emphasizes its vulnerabilities will have a much more significant impact on the follower’s affective commitment. Moral anguish prevents this type of commitment from proposing a beneficial scheme and instead acts as a resource catalyst that exhausts and frustrates the follower. However, this type of commitment can buffer emotional exhaustion if the ethical leader avoids becoming a preliminary factor of possible ethical distances.

These findings have multiple limitations that may benefit future research. The model was analyzed in an emerging country, Colombia. Regarding results generalization, it is essential to highlight the unique characteristics of Colombian leaders that considerably differ from the usual rigidity of ethical leaders. Additionally, Colombian leadership tends to be lenient when it comes to applying sanctions, and reward or punishment is precisely one of the differentiating facets of ethical leaders (Páez & Salgado, 2016).

The results of this research are probably because the organizations studied are primarily public, and the anti-corruption policies proposed in the last seven years collide with Colombian idiosyncrasy itself. Therefore, excessively ethical leaders provoke such pronounced reactions in followers’ emotional exhaustion. Finally, the main limitation of this research is the transversality that prevents determining a clear time sequence between dependent and independent variables, as both are measured simultaneously.

Regarding future research, it would be interesting to replicate the model not only in countries with identities similar to Colombia, but also in places with different characteristics to obtain more complete knowledge of the impact of ethical leadership on emotional exhaustion, and to validate this curvilinear perception. It is also possible to include other leadership styles with traits matching those of ethical leadership. For example, transformational or authentic leadership to determine a possible exclusivity of ethical leadership on emotional exhaustion. On the other hand, the approaches of some emerging leaderships, such as ethical, authentic, or service leadership, are aimed toward the followers’ behaviors and moral advancement, along with a learning style based on social contact and understanding of their context. In fact, they are strongly related to each other, which indicates an inevitable empirical overlap and redundancy, including even transformational leadership (Hoch & Kozlowski, 2014; Lemoine et al., 2019).

However, beyond their similarities, it would be interesting to study how they impact emotional exhaustion and to determine a possible exclusivity of ethical leadership. Most results establish a mitigating influence of these management styles on emotional exhaustion (Stein et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2016). Therefore, the opposite effect revealed by ethical leadership in this research represents an advance in understanding the undesirable effects of a specific management style. Finally, using moderators, among others, psychological safety, introjected motivation, or personality traits could expand the existing literature on the effect of ethical leadership.