Submitted:

29 August 2024

Posted:

30 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Data collection and Measurement

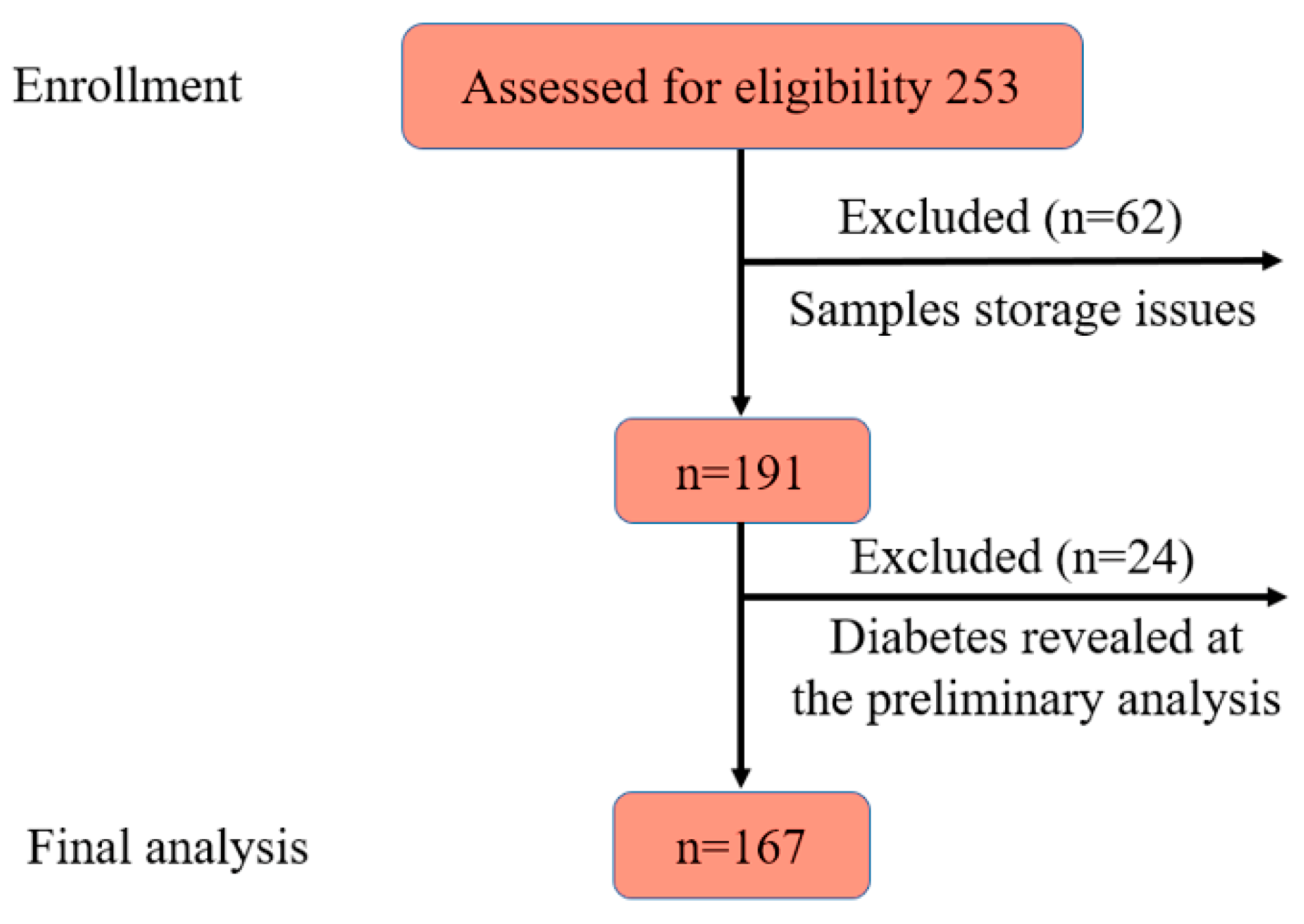

Participants

Ethics Considerations

Diagnostic Criteria

Chemicals

Biochemistry

Gas-Chromatography Mass-Spectrometry

Sample Preparation

GC-MS Analysis

Quantitative Variables

Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Data

3.2. Amino Acids and Lipid Profile

3.3. Amino Acids and the Risk of Prediabetes

3.4. AAs and Prediction of Prediabetes

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abate, N. , & Chandalia, M. ‘Ethnicity and type 2 diabetes: focus on Asian Indians.’. Journal of diabetes and its complications, 2001, 15(6), 320–327.

- Arora, P., Kumar, V. and Popli, P. Conceptual Overview of Prevalence of Prediabetes. Current Diabetes Reviews. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H. Reframing prediabetes: A call for better risk stratification and intervention. Journal of Internal Medicine, 2024, 295(6), pp.735-747. [CrossRef]

- Committee, T.I.E. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes care, 2009, 32(7), p.1327.

- Piller, C. Dubious diagnosis. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/definition-and-diagnosis-of-diabetes-mellitus-and-intermediate-hyperglycaemia.

- Genc, S. , Evren, B., AYDIN, M. and Sahin, I. Evaluation of prediabetes patients in terms of metabolic syndrome. European Review for Medical & Pharmacological Sciences, 2024, 28(7). [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. , Li, X., Adams, H., Kubena, K. and Guo, S. Etiology of metabolic syndrome and dietary intervention. International journal of molecular sciences, 2018, 20(1), p.128. [CrossRef]

- Standl, E. Aetiology and consequences of the metabolic syndrome. European Heart Journal Supplements, 2005, 7 (suppl_D), pp.D10-D13. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.B. The role of prediabetes in the metabolic syndrome: guilt by association. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders, 2023, 21(4), pp.197-204. [CrossRef]

- Knezek, S. , Engelen, M. , Ten Have, G., Thaden, J. and Deutz, N. Prediabetes Is Associated with Specific Changes in Valine Metabolism. Current Developments in Nutrition, 2022, 6, p34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. , Jung, S. and Ko, K.S. Effects of amino acids supplementation on lipid and glucose metabolism in HepG2 cells. Nutrients, 2022, 14(15), p.3050. [CrossRef]

- Formagini, T. , Brooks, J. V., Roberts, A., Bullard, K.M., Zhang, Y., Saelee, R. and O’Brien, M.J. Prediabetes prevalence and awareness by race, ethnicity, and educational attainment among US adults. Frontiers in Public Health, 2023, 11, p1277657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DING, Q. , LU, Y., HERRIN, J., ZHANG, T. and MARRERO, D.G. 1271-P: Associations of Combined Socioeconomic, Behavioral, and Metabolic Factors with Undiagnosed Diabetes and Prediabetes among Different Racial and Ethnic Groups. Diabetes, 2023, 72(Supplement_1). [CrossRef]

- Adjei, N.K. , Samkange-Zeeb, F. , Kebede, M., Saleem, M., Heise, T.L. and Zeeb, H. Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence and incidence of metabolic syndrome in high-income countries: a protocol for a systematic review. Systematic reviews, 2020, 9, pp.1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seah, J.Y.H. , Hong, Y., Cichońska, A., Sabanayagam, C., Nusinovici, S., Wong, T.Y., Cheng, C.Y., Jousilahti, P., Lundqvist, A., Perola, M. and Salomaa, V. Circulating metabolic biomarkers consistently predict incident type 2 diabetes in Asian and European populations–a plasma metabolomics analysis of four ethnic groups. medRxiv, 2021, pp.2021-07.

- Mancia, G.; Fagard, R.; Narkiewicz, K.; Redon, J.; Zanchetti, A.; Böhm, M.; Christiaens, T.; Cifkova, R.; De Backer, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Blood Press. 2013, 22, 193–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes, A. 2. classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care (2021) 44(Suppl 1): S15–33. [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. The IDF Consensus Worldwide Definition of the Metabolic Syndrome. 2005. http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/MetSyndrome_FINAL.pdf.

- Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome--a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006 May;23(5):469-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alasmari, F. , Assiri, M.A., Ahamad, S.R., Aljumayi, S.R., Alotaibi, W.H., Alhamdan, M.M., Alhazzani, K., Alharbi, M., Alqahtani, F. and Alasmari, A.F. Serum metabolomic analysis of male patients with cannabis or amphetamine use disorder. Metabolites, 2022, 12(2), p.179. [CrossRef]

- Shi, S. , Yi, L., Yun, Y., Zhang, X. and Liang, Y. A combination of GC-MS and chemometrics reveals metabolic differences between serum and plasma. Analytical Methods, 2015, 7(5), pp.1751-1757. [CrossRef]

- Yao, H. , Shi, P., Zhang, L., Fan, X., Shao, Q. and Cheng, Y. Untargeted metabolic profiling reveals potential biomarkers in myocardial infarction and its application. Molecular BioSystems, 2010, 6(6), pp.1061-1070. [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001 May 16;285(19):2486-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, MS. The emerging role of branched-chain amino acids in insulin resistance and metabolism. Nutrients 2016; 8:7.

- Lynch CJ, Adams SH. Branched-chain amino acids in metabolic signalling and insulin resistance. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014; 10:723–36. [CrossRef]

- Tessari P, Cecchet D, Cosma A, et al. Insulin resistance of amino acid and protein metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Clin Nutr. 2011;30(3):267–72. [CrossRef]

- Gar C, Rottenkolber M, Prehn C, Adamski J, Seissler J, Lechner A. Serum and plasma amino acids as markers of prediabetes, insulin resistance, and incident diabetes. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2018 Jan;55(1):21-32. [CrossRef]

- Long J, Yang Z, Wang L, Han Y, Peng C, Yan C, Yan D. Metabolite biomarkers of type 2 diabetes mellitus and pre-diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocr Disord. 2020 Nov 23;20(1):174. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park JE, Lim HR, Kim JW, Shin KH. Metabolite changes in risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in cohort studies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018 Jun;140:216-227. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira-Ferreira, R. , Oliveira, P.F. and Ferreira, R. Liver metabolism: the pathways underlying glucose utilization and production. In Glycolysis, Academic Press. 2024, (pp. 141-156). [CrossRef]

- Gautier-Stein, A. , Chilloux, J. , Soty, M., Thorens, B., Place, C., Zitoun, C., Duchampt, A., Da Costa, L., Rajas, F., Lamaze, C. and Mithieux, G. A caveolin-1 dependent glucose-6-phosphatase trafficking contributes to hepatic glucose production. Molecular metabolism, 2023, 70, p101700. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, S.C. , Leone, T.C., Wende, A.R., Croce, M.A., Chen, Z., Sherry, A.D., Malloy, C.R. and Finck, B.N. Diminished hepatic gluconeogenesis via defects in tricarboxylic acid cycle flux in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α)-deficient mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2006, 281(28), pp.19000-19008.

- Satapati, S. , Sunny, N.E., Kucejova, B., Fu, X., He, T.T., Méndez-Lucas, A., Shelton, J.M., Perales, J.C., Browning, J.D. and Burgess, S.C. Elevated TCA cycle function in the pathology of diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance and fatty liver [S]. Journal of lipid research, 2012, 53(6), pp.1080-1092. [CrossRef]

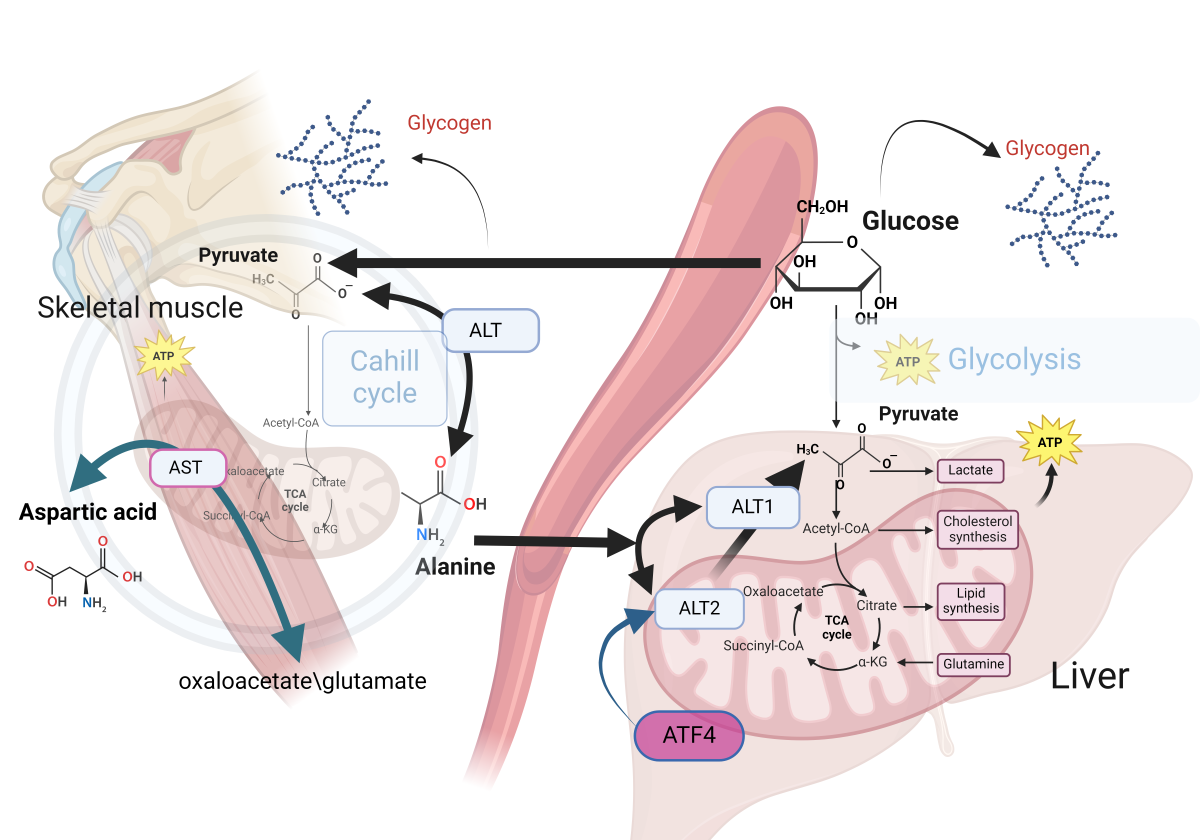

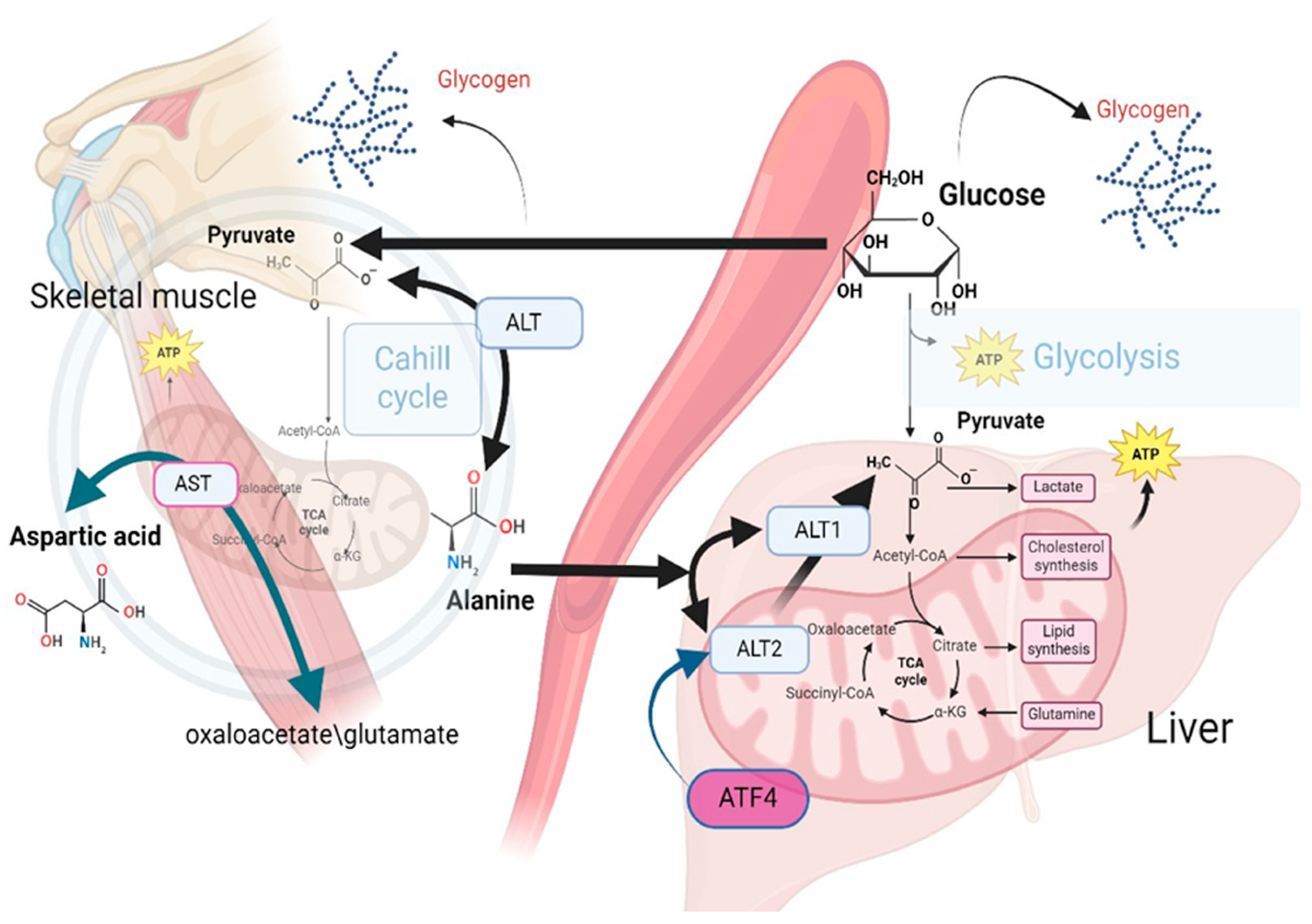

- Felig, P. , Pozefsk, T., Marlis, E. and Cahill, G.F. Alanine: key role in gluconeogenesis. Science, 1970, 167(3920), pp.1003-1004.

- Waterhouse, C. and Keilson, J. The contribution of glucose to alanine metabolism in man. The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine, 1978, 92(5), pp.803-812.

- Holeček, M. Origin and roles of Alanine and glutamine in Gluconeogenesis in the liver, kidneys, and small intestine under physiological and pathological conditions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024, 25(13), p.7037. [CrossRef]

- J Ryan, P. , Riechman, S.E., Fluckey, J.D. and Wu, G. Interorgan metabolism of amino acids in human health and disease. Amino Acids in Nutrition and Health: Amino Acids in Gene Expression, Metabolic Regulation, and Exercising Performance, 2021, pp.129-149. [CrossRef]

- Paulusma, C.C. , Lamers, W. H., Broer, S. and van de Graaf, S.F. Amino acid metabolism, transport and signalling in the liver revisited. Biochemical pharmacology, 2022, 201, p115074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiew, N.K. , Vazquez, J. H., Martino, M.R., Kennon-McGill, S., Price, J.R., Allard, F.D., Yee, E.U., Layman, A.J., James, L.P., McCommis, K.S. and Finck, B.N. Hepatic pyruvate and alanine metabolism are critical and complementary for maintenance of antioxidant capacity and resistance to oxidative insult. Molecular Metabolism, 2023, 77, p101808. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.Z. , Park, S., Reagan, W.J., Goldstein, R., Zhong, S., Lawton, M., Rajamohan, F., Qian, K., Liu, L. and Gong, D.W. Alanine aminotransferase isoenzymes: molecular cloning and quantitative analysis of tissue expression in rats and serum elevation in liver toxicity. Hepatology, 2009, 49(2), pp.598-607. [CrossRef]

- DeRosa, G. and Swick, R.W. Metabolic implications of the distribution of the alanine aminotransferase isoenzymes. Journal of biological chemistry, 1975, 250(20), pp.7961-7967.

- McCommis, K.S. , Chen, Z., Fu, X., McDonald, W.G., Colca, J.R., Kletzien, R.F., Burgess, S.C. and Finck, B.N. Loss of mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 2 in the liver leads to defects in gluconeogenesis and compensation via pyruvate-alanine cycling. Cell metabolism, 2015, 22(4), pp.682-694. [CrossRef]

- Okun, J.G. , Rusu, P.M., Chan, A.Y., Wu, Y., Yap, Y.W., Sharkie, T., Schumacher, J., Schmidt, K.V., Roberts-Thomson, K.M., Russell, R.D. and Zota, A. Liver alanine catabolism promotes skeletal muscle atrophy and hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes. Nature metabolism, 2021, 3(3), pp.394-409. [CrossRef]

- Martino, M.R. , Gutiérrez-Aguilar, M., Yiew, N.K., Lutkewitte, A.J., Singer, J.M., McCommis, K.S., Ferguson, D., Liss, K.H., Yoshino, J., Renkemeyer, M.K. and Smith, G.I. Silencing alanine transaminase 2 in diabetic liver attenuates hyperglycemia by reducing gluconeogenesis from amino acids. Cell reports, 2022, 39(4). [CrossRef]

- Sherman, K.E. Alanine aminotransferase in clinical practice: a review. Archives of internal medicine, 1991, 151(2), pp.260-265.

- Liu, Z. , Que, S., Xu, J. and Peng, T. Alanine aminotransferase-old biomarker and new concept: a review. International journal of medical sciences, 2014,11(9), p.925.

- Zhao X, Han Q, Liu Y, Sun C, Gang X, Wang G. The Relationship between Branched-Chain Amino Acid Related Metabolomic Signature and Insulin Resistance: A Systematic Review. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:2794591. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, A.Y. , Asokan, A.K., Lalia, A.Z., Sakrikar, D., Lanza, I.R., Petterson, X.M. and Nair, K.S. Insulin regulation of lysine and α-aminoadipic acid dynamics and amino metabolites in insulin-resistant and control women. Diabetes, 2024, p.db230977. [CrossRef]

- Razquin, C. , Ruiz-Canela, M. , Clish, C.B., Li, J., Toledo, E., Dennis, C., Liang, L., Salas-Huetos, A., Pierce, K.A., Guasch-Ferré, M. and Corella, D. Lysine pathway metabolites and the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in the PREDIMED study: results from two case-cohort studies. Cardiovascular diabetology, 2019, 18, pp.1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owei I, Umekwe N, Stentz F, Wan J, Dagogo-Jack S. Amino acid signature predictive of incident prediabetes: A case-control study nested within the longitudinal pathobiology of prediabetes in a biracial cohort. Metabolism. 2019 Sep;98:76-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Z.N. , Jiang, Y.F., Ru, J.N., Lu, J.H., Ding, B. and Wu, J. Amino acid metabolism in health and disease. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2023, 8(1), p.345. [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.H. , Feng, X. F., Yang, X.L., Hou, R.Q. and Fang, Z.Z. Interactive effects of asparagine and aspartate homeostasis with sex and age for the risk of type 2 diabetes risk. Biology of sex Differences, 2020, 11, pp.1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Holeček, M. The role of skeletal muscle in the pathogenesis of altered concentrations of branched-chain amino acids (valine, leucine, and isoleucine) in liver cirrhosis, diabetes, and other diseases. Physiological research, 2021, 70(3), p.293. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F. , Zhang, Y.X. and Ma, H.Y. Targeted profiling of amino acid metabolome in serum by a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method: application to identify potential markers for diet-induced hyperlipidemia. Analytical Methods, 2020, 12(18), pp.2355-2362. [CrossRef]

- Yang, P. , Hu, W. , Fu, Z., Sun, L., Zhou, Y., Gong, Y., Yang, T. and Zhou, H. The positive association of branched-chain amino acids and metabolic dyslipidemia in Chinese Han population. Lipids in health and disease, 2016, 15, pp.1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, V. , Chawla, R., Mah, T., Vivekanandan, R., Tan, S.Y., Sato, P.Y. and Mallilankaraman, K. Mitochondrial dysfunction in age-related metabolic disorders. Proteomics, 2020, 20(5-6), p.1800404. [CrossRef]

- Shahram, N. , Sungbo, C. and Eugeni, R. Alanine-specific appetite in slow growing chickens is associated with impaired glucose transport and TCA cycle. BMC Genomics (Web), 2022, 23(1), pp.1-16. [CrossRef]

- Onyango, A.N. Excessive gluconeogenesis causes the hepatic insulin resistance paradox and its sequelae. Heliyon, 2022, 8(12). [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Absolute number/% or mean/SD |

Prediabetes,% | P-value | |

| Yes | No | |||

| Gender, male | 75/44.12 | 70.83 | 29.17 | 0.367 |

| Age (years) | 50.55/7.47 | |||

| <39 | 10/5.88 | 4.46 | 9.09 | 0.04 |

| 40-49 | 70/41.18 | 35.71 | 52.73 | |

| 50-59 | 70/41.18 | 44.64 | 32.73 | |

| >60 | 20/11.76 | 15.18 | 5.45 | |

| BMI categories (kg/m2) | ||||

| <24.9 | 43/25.75 | 18.35 | 41.82 | 0.001, 0.0002* |

| 25-29.9 | 70/41.92 | 42.20 | 41.82 | |

| >30.0 | 54/32.34 | 39.45 | 16.36 | |

| Hypertension | 50/29.94 | 33.94 | 21.82 | 0.109 |

| Smoking | ||||

| No | 113/67.66 | 69.72 | 63.64 | 0.03 |

| Quitted | 34/20.36 | 15.60 | 30.91 | |

| Yes | 20/11.98 | 14.68 | 5.45 | |

| High fasting glucose (>5.6) | 23/13.61 | 73,91 | 26.09 | 0.452 |

| Lipid profile (mmol/L) | ||||

| High LDL-C (>3.3) | 73/42.94 | 70.83 | 29.17 | 0.367 |

| Low HDL-C (<1.03 in males, <1.29 in females) | 57/33.53 | 75.44 | 24.56 | 0.097 |

| High TG (>1.7) | 46/27.06 | 79.55 | 20.45 | 0.04 |

| Amino acids, mmol/L | High LDL-C>3.3 mmol/L | HDL-C>1.03 mmol/L in males and >1.29 mmol/L in females | TG>1.7 mmol/L | |||

| ORcrude | ORadjusted | ORcrude | ORadjusted | ORcrude | ORadjusted | |

| Lysine <2.57 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 1.45 | 1.50 | 0.72 | 0.76 |

| Tyrosine <1.03 | 1.28 | 1.18 | 1.50 | 1.64 | 1.02 | 0.86 |

| Alanine <10.86 | 1.26 | 1.37 | 2.22* | 2.29* | 0.28** | 0.28** |

| Valine <5.74 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 1.89 | 1.72 |

| Leucine <6.36 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.88 |

| Isoleucine <3.58 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 1.01 | 2.30* | 1.99* |

| Proline <3.70 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 1.51 | 1.55 | 0.45* | 0.45* |

| Serine <1.69 | 1.12 | 1,23 | 2.11* | 1.97 | 0.24*** | 0.27*** |

| Threonine <1.52 | 1.74 | 1.96 | 3.01** | 2.93** | 0.32** | 0.35* |

| Methionine <1.14 | 0.96 | 1.06 | 1.77 | 1.73 | 0.27*** | 0.28** |

| Aspartic acid <0.27 | 1.95 | 1.80 | 1.09 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.02 |

| Glutamic acid <0.87 | 1.0 | 0.99 | 2.16* | 2.45* | 0.37** | 0.35** |

| Phenylalanine <0.58 | 1.0 | 1.13 | 2.22* | 2.31* | 0.45* | 0.54 |

| AAs, mmol/L | ORcrude | 95%CI | p-value |

| Lysine >2.57 | 2.19 | 1.04;4.63 | 0.039 |

| Tyrosine <1.03 | 0.75 | 0.35;1.63 | 0.47 |

| Alanine <10.86 | 1.89 | 0.96;3.70 | 0.064 |

| Valine <5.74 | 0.60 | 0.29;1.21 | 0.153 |

| Leucine <6.36 | 0.74 | 0.38;1.43 | 0.367 |

| Isoleucine <3.58 | 0.67 | 0.34;1.33 | 0.249 |

| Proline <3.70 | 1.04 | 0.52;2.09 | 0.911 |

| Serine <1.69 | 1.02 | 0.51;2.07 | 0.953 |

| Threonine <1.52 | 1.27 | 0.60;2.66 | 0.531 |

| Methionine <1.14 | 0.55 | 0.28;1.09 | 0.087 |

| Aspartic <0.27 | 2.91 | 1.24;6.81 | 0.014 |

| Glutamic <0.87 | 0.83 | 0.42;1.66 | 0.595 |

| Phenylalanine <0.58 | 0.73 | 0.35;1.55 | 0.416 |

| Number of observations | OR of prediabetes | 95%CI | P-value | Adjusted for | Model |

| Alanine<10.86 mmol/L | |||||

| 156 | 1.89 | 0.96;3.70 | 0.064 | Crude | 1 |

| 156 | 2.17 | 1.06;4.48 | 0.035 | Ageα | 2 |

| 153 | 2.19 | 1.03;4.60 | 0.042 | Age+BMIβ | 3 |

| Lysine > 2.57 mmol/L | |||||

| 129 | 2.19 | 1.04;4.63 | 0.039 | Crude | 1 |

| 129 | 2.11 | 0.99;4.50 | 0.053 | Ageα | 2 |

| 126 | 2.31 | 1.03;5.14 | 0.041 | Age+BMIβ | |

| Aspartic<0.27 mmol/L | |||||

| 103 | 2.91 | 1.24;6.81 | 0.014 | Crude | 1 |

| 103 | 3.0 | 1.25;7.22 | 0.014 | Ageα | 2 |

| 100 | 2.87 | 1.12;9.86 | 0.026 | Age+BMIβ | 3 |

| LR Models | AUC | Cutoff point**, mmol/L | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | |

| Crude | Adjusted for age and BMI | ||||

| Alanine | 0.47 | 0.73 | 10.21 | 90.00 | 37.74 |

| Lysine | 0.61 | 0.74 | 2.51 | 79.01 | 48.89 |

| Aspartic | 0.49 | 0.76 | 0.056 | 90.77 | 45.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).