Submitted:

28 August 2024

Posted:

29 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

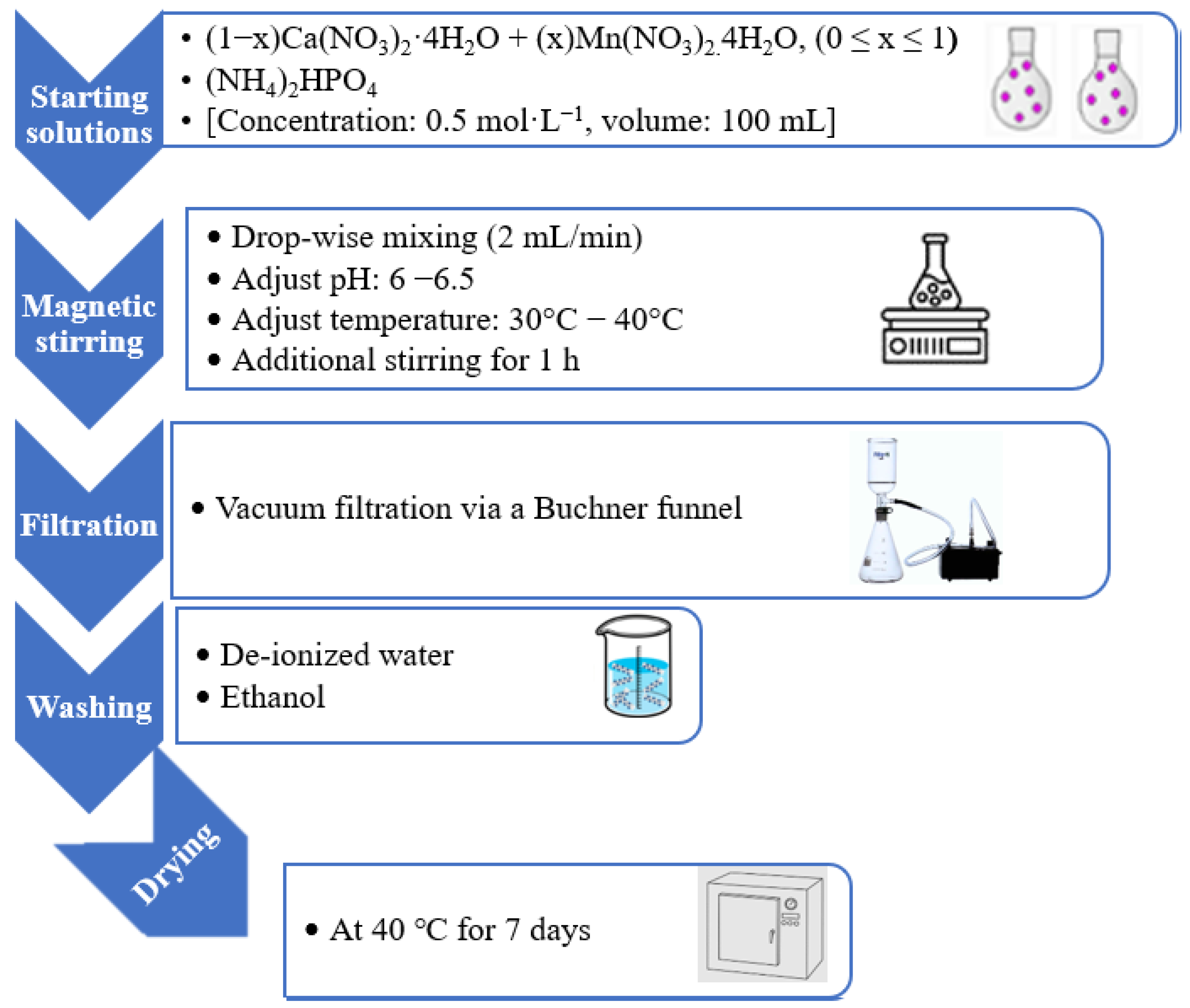

2.2. Synthesis of Ca1−xMnxHPO4·nH2O Compounds

2.3. Characterization Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

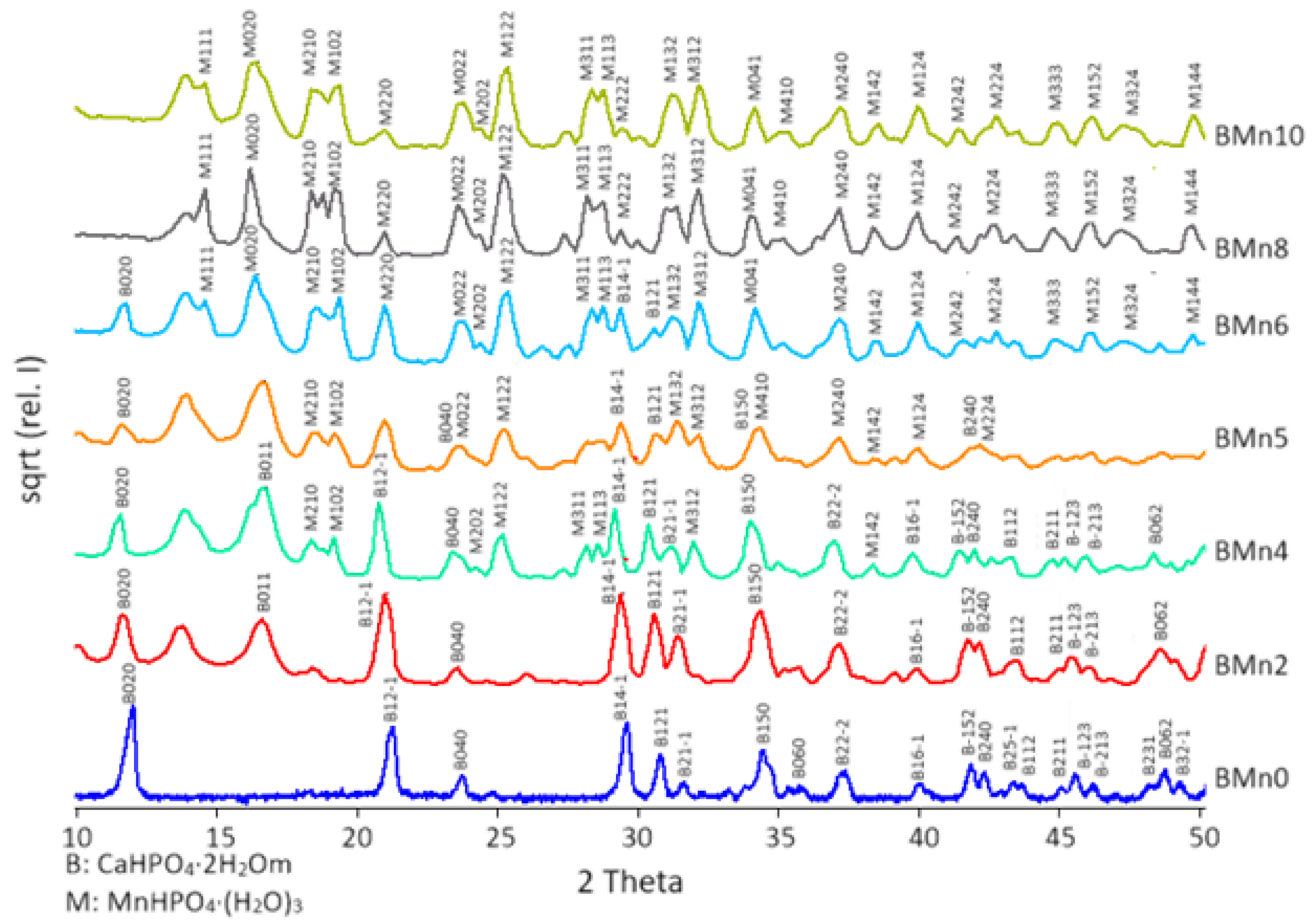

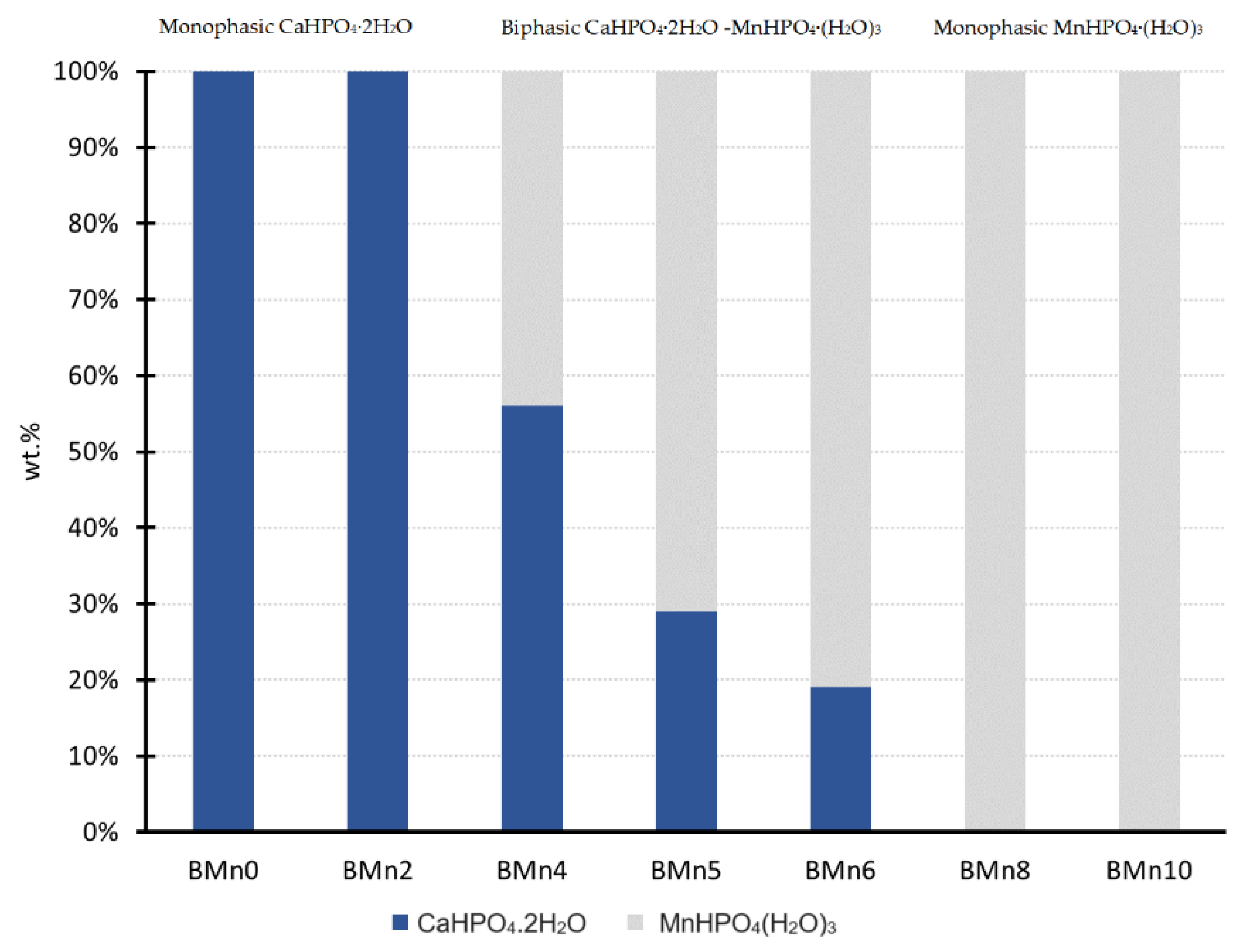

3.1. Phase Characterization and Microstructural Analysis

3.2. FT-IR Spectrum of Ca1−xMnxHPO4·nH2O Compounds

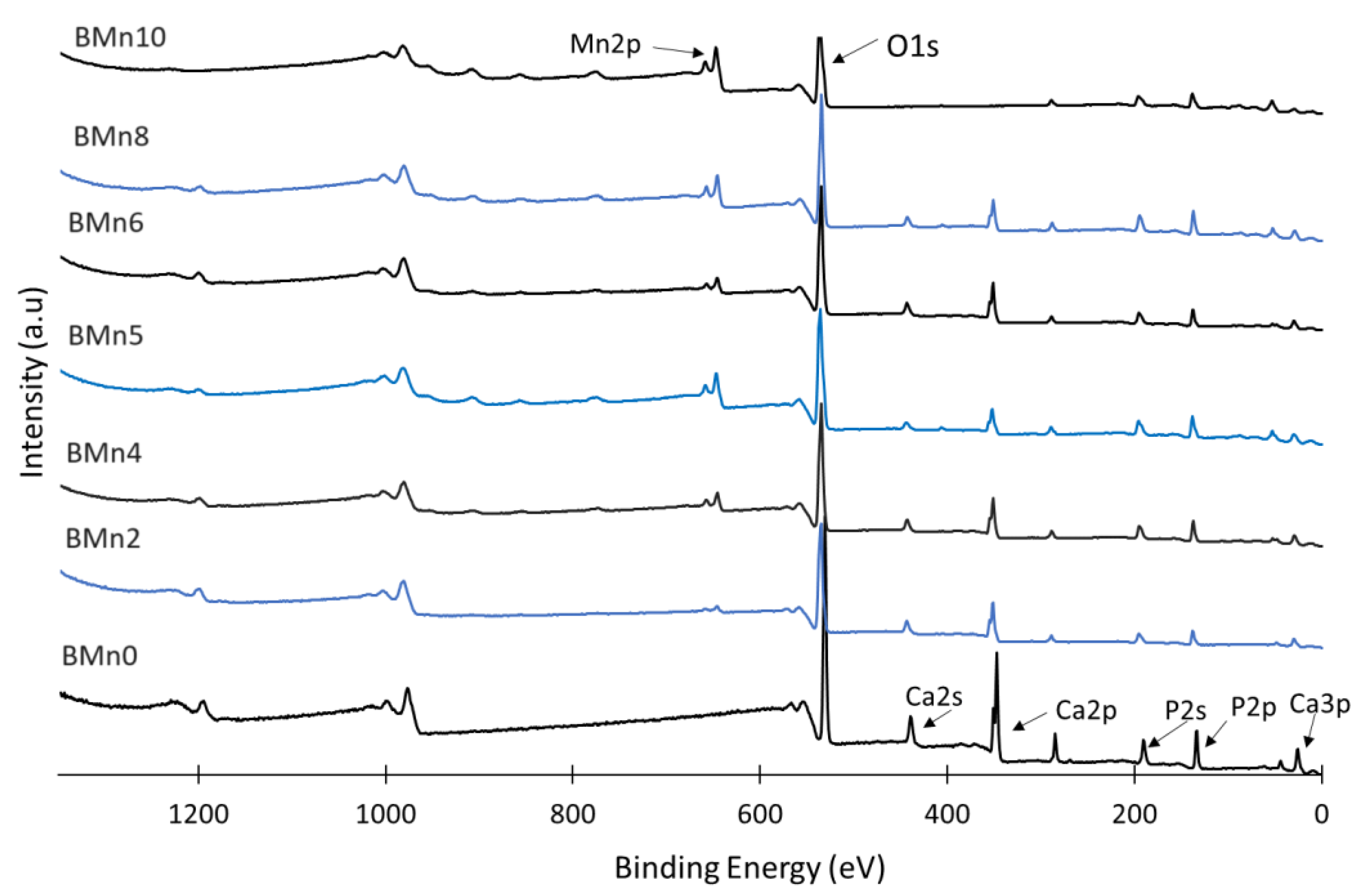

3.3. Elemental Analysis of Ca1−xMnxHPO4·nH2O Compounds

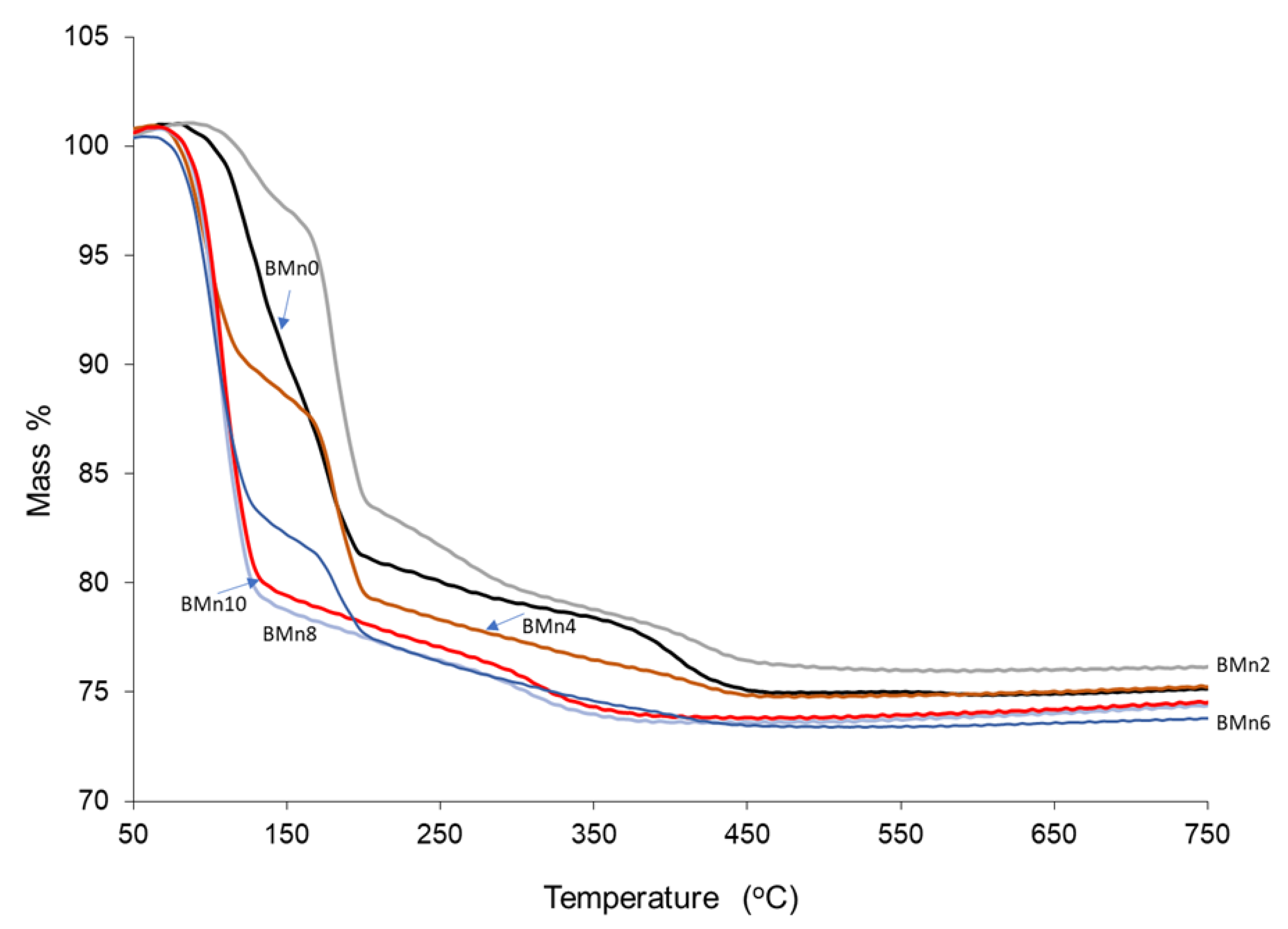

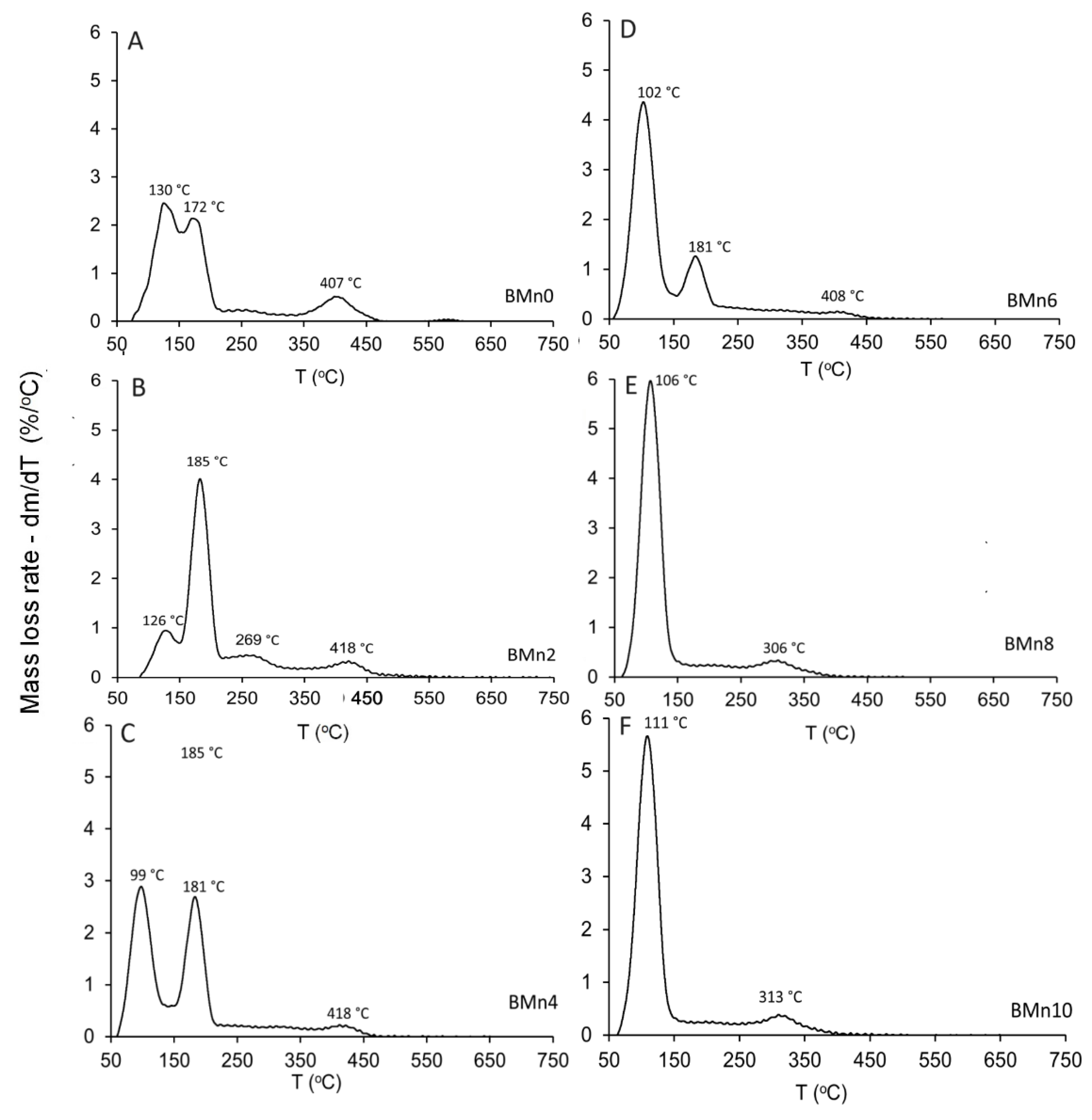

3.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- R. Khalifehzadeh and H. Arami, "Biodegradable calcium phosphate nanoparticles for cancer therapy," Advances in Colloid and Interface Science, vol. 279, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Wu, J. Wei, H. Guo, F. Chen, H. Hong and C. Liu, "Self-setting bioactive calcium-magnesium phosphate cement with high strength and degradability for bone regeneration," Acta Biomaterialia, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 1873-1884, 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. Alshaaer, M. H. Kailani, H. Jafar, N. Ababneh and A. Awidi, "Physicochemical and Microstructural Characterization of Injectable Load-Bearing Calcium Phosphate Scaffold," Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, 2013. [CrossRef]

- I. Mert, S. Mandel and A. C. Tas, "Do cell culture solutions transform brushite (CaHP04 2H20) to octacalium phosphate (Ca8(HP04)2(P04)4 5H20)?," in Advances in Bioceramics and Porous Ceramics IV, R. Narayan and P. Colombo, Eds., Hoboken, New Jersey.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2011, pp. 79-94.

- M. Vallet-Regí, "Our contributions to applications of mesoporous silica nanoparticles," Acta Biomaterialia, vol. 137, pp. 44-52, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Sánchez-Salcedo, A. García, A. González-Jiménez and M. Vallet-Regí, "Antibacterial effect of 3D printed mesoporous bioactive glass scaffolds doped with metallic silver nanoparticles," Acta Biomaterialia, vol. 155, pp. 654-666, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Alshaaer, J. Al-Kafawein, A. Afify, N. Hamad, G. Saffarini and K. Issa, "Effect of Ca2+ Replacement with Cu2+ Ions in Brushite on the Phase Composition and Crystal Structure," Minerals, vol. 11, p. 1028, 2021.

- V. Mouriño, J. Cattalini and A. Boccaccini, "Metallic ions as therapeutic agents in tissue engineering scaffolds: an overview of their biological applications and strategies for new developments," J R Soc Interface, vol. 9, no. 68, pp. 401-419, 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. Rosas, A. Ong, L. Buller, K. Sabeh, T. Law, M. Roche and V. Hernández, "Season of the year influences infection rates following total hip arthroplasty," World J. Orthop., vol. 8, no. 12, pp. 895-901, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Wei, J. Ma, L. Xu, X.-S. Gu and X.-L. Ma, "Biodegradable materials for bone defect repair," Military Medical Research, vol. 7, no. 54, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Alshaaer, M. H. Kailani, N. Ababneh, S. A. A. Mallouh, B. Sweileh and A. Awidi, "Fabrication of porous bioceramics for bone tissue applications using luffa cylindrical fibres (LCF) as template," Processing and Application of Ceramics , vol. 11, no. 1, p. 13–20, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Nosrati, D. Quang Svend Le, Zolfaghari, R. Emameh, Canillas, M. Perez and C. Eric Bünger, "Nucleation and growth of brushite crystals on the graphene sheets applicable in bone cement," Boletín de la Sociedad Española de Cerámica y Vidrio, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Tamimi, N. D. L., H. Eimar, Z. Sheikh, S. Komarova and J. Barralet, "The effect o fautoclaving on the physical and biological properties of dicalcium phosphate dihydrate bioceramics: Brushite vs. monetite," Acta Biomaterialia, vol. 8, no. 8, pp. 3161-3169, 2012.

- K. Hurle, J. Oliveira, R. Reis, S. Pina and F. Goetz-Neunhoeffer, "Ion-doped Brushite Cements for Bone Regeneration," Acta Biomaterialia, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Dosen and R. F. Giese, "Thermal decomposition of brushite, CaHPO4·2H2O to monetite CaHPO4 and the formation of an amorphous phase," American Mineralogist, vol. 96, no. (2-3), p. 368–373, 2011.

- N. H. Radwan, M. Nasr, R. A. Ishak, N. F. Abdeltawa and G. A. Awad, "Chitosan-calcium phosphate composite scaffolds for control of postoperative osteomyelitis: Fabrication, characterization, and in vitro–in vivo evaluation," Carbohydrate Polymers, vol. 244, p. 116482, 2020.

- Z. Xue, Z. Wang, A. Sun, J. Huang, W. Wu, M. Chen, X. Hao, Z. Huang, X. Lin and S. Weng, "Rapid construction of polyetheretherketone (PEEK) biological implants incorporated with brushite (CaHPO4·2H2O) and antibiotics for anti-infection and enhanced osseointegration," Materials Science and Engineering: C, vol. 111, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B.-Q. Lu, T. Willhammar, B.-B. Sun, N. Hedin, J. D. Gale and D. Gebauer, "Introducing the crystalline phase of dicalcium phosphate monohydrate," Nat Commun, vol. 11, p. 1546, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Tortet, J. R. Gavarri and G. Nihoul, "Study of Protonic Mobility in CaHPO4 · 2H2O (Brushite) and CaHPO4 (Monetite) by Infrared Spectroscopy and Neutron Scattering," Journal of Solid State Chemistry, vol. 132, pp. 6-16, 1997. [CrossRef]

- N. Matsumoto, K. Sato, K. Yoshida, K. Hashimoto and Y. Toda, "Preparation and characterization of beta-tricalcium phosphate co-doped with monovalent and divalent antibacterial metal ions," Acta Biomater., vol. 5, pp. 3157-3164, 2009.

- I. Mayer, O. Jacobsohn, T. Niazov, J. Werckmann, M. Iliescu, M. Richard-Plouet, O. Burghaus and D. Reinen, "Manganese in Precipitated Hydroxyapatites," European journal of inorganic chemistry, vol. 2003, p. 1445−1451, 2003.

- E. Boanini, F. Silingardi, M. Gazzano and A. Bigi, "Synthesis and Hydrolysis of Brushite (DCPD): The Role of Ionic Substitution," Crystal Growth & Design, vol. 21, p. 1689−1697, 2021.

- H. E. L. Madsen, "influence of foreign metal ions on crystal growth and morphology of brushite (CaHPO4, 2H2O) and its transformation to octacalcium phosphate and apatite," Journal of Crystal Growth, vol. 310, no. 10, pp. 2602-2612, 2008.

- D. Griesiute, E. Garskaite, A. Antuzevics, V. Klimavicius, V. Balevicius, A. Zarkov, A. Katelnikovas, D. Sandberg and A. Kareiva, "Synthesis, structural and luminescent properties of Mn-doped calcium pyrophosphate (Ca2P2O7) polymorphs," Scientific Reports, vol. 12, p. 7116, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Patil, A. Jena and P. Bhargava, "Influence of Ethanol Amount During Washing on Deagglomeration of Co-Precipitated Calcined Nanocrystalline 3YSZ Powders," International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology, 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. H. Piva, D. H. Piva, J. Pierri, O. R. K. Montedo and M. R. Morelli, "Azeotropic distillation, ethanol washing, and freeze drying on coprecipitated gels for production of high surface area 3Y–TZP and 8YSZ powders: A comparative study," Ceramics International, vol. 41, pp. 14148-14156, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Alshaaer, A. Afify, M. Moustapha, N. Hamad, G. Hammouda and F. Rocha, "Effects of the full-scale substitution of strontium for calcium on the microstructure of brushite: (CaxSr1–x)HPO4.nH2O system," Clay Minerals, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 366-374, 2020.

- Schofield P. F., Knight K. S., van der Houwen J. A. M., Valsami-Jones E, "The role of hydrogen bonding in the thermal expansion and dehydrationof brushite, di-calcium phosphate dihydrateSample: T = 4.2 K", Physics and Chemistry of Minerals 31, 606-624 (2004).

- Jin K, Park J, Lee J, Yang KD, Pradhan GK, Sim U, Jeong D, Jang HL, Park S, Kim D, Sung NE, Kim SH, Han S, Nam KT. Hydrated manganese(II) phosphate (Mn₃(PO₄)₂·3H₂O) as a water oxidation catalyst. J Am Chem Soc. 2014 May 21;136(20):7435-43. doi: 10.1021/ja5026529. Epub 2014 May 7. PMID: 24758237. [CrossRef]

- F. Abdulaziz, K. Issa, M. Alyami, S. Alotibi, A. Alanazi, T. Taha, A. Saad, G. Hammouda, N. Hamad and M. Alshaaer, "Preparation and Characterization of Mono- and Biphasic Ca1−xAgxHPO4·nH2O Compounds for Biomedical Applications," Biomimetics, vol. 8, p. 547, 2023.

- S. Wang, R. Zhao, S. Yao, B. Li, R. Liu, L. Hu, A. Zhang, R. Yang, X. Liu, Z. Fu, D. Wang, Z. Yang and Y.-M. Yan, "Stretching the c-axis of the Mn3O4 lattice with broadened ion transfer channels for enhanced Na-ion storage," Journal of Materials Chemistry A, vol. 9, no. 41, pp. 23506-23514, 2021.

- S. S. Alotibi and M. Alshaaer, "The Effect of Full-Scale Exchange of Ca2+ with Co2+ Ions on the Crystal Structure and Phase Composition of CaHPO4·2H2O," Crystals, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 941, 2023.

- L. Tortet, J. R. Gavarri, G. Nihoul and A. J. Dianoux, "Study of Protonic Mobility in CaHPO4·2H2O (Brushite) and CaHPO4 (Monetite) by Infrared Spectroscopy and Neutron Scattering," J. Solid State Chem., vol. 132, p. 6– 16, 1997. [CrossRef]

- A. Hirsch, I. Azuri, L. Addadi, S. Weiner, K. Yang, S. Curtarolo and L. Kronik, "Infrared Absorption Spectrum of Brushite from First Principles," Chem. Mater. , vol. 26, p. 2934– 2942, 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. K. C. Rajendran, "Growth and Characterization of Calcium Hydrogen Phosphate Dihydrate Crystals from Single Dif-fusion Gel Technique," Cryst. Res. Technol, vol. 45, no. 9, pp. 939- 945, 2010.

- Wang, T., Li, Z. Effects of MnO2 addition on the structure and electrical properties of PIN-PZN-PT ceramics with MPB composition. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 31, 22740–22748 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-020-04798-2. [CrossRef]

- M. Alshaaer, H. Cuypers, H. Rahier and J. Wastiels, "Production of monetite-based Inorganic Phosphate Cement (M-IPC) using hydrothermal post curing (HTPC)," Cement and Concrete Research, vol. 41, p. 30–37, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Dosen, Anja and Giese, Rossman F.. "Thermal decomposition of brushite, CaHPO4·2H2O to monetite CaHPO4 and the formation of an amorphous phase" American Mineralogist, vol. 96, no. 2-3, 2011, pp. 368-373. [CrossRef]

- M. Alshaaer, H. Cuypers, G. Mosselmans, H. Rahier and J. Wastiels, "Evaluation of a low temperature hardening Inorganic Phosphate Cement for high-temperature applications," Cement and Concrete Research, vol. 41, p. 38–45, 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Frost and S. J. Palmer, "Thermal stability of the ‘cave’ mineral brushite CaHPO4·2H2O – Mechanism of formation and decomposition," Thermochimica Acta, vol. 521, no. 1-2, pp. 14-17, 2011.

| ID | (NH4)2HPO4 | Ca(NO3)2·4H2O | Mn(NO3)2·4H2O | Mn/Ca Molar Ratio |

| BMn0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| BMn2 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.25 |

| BMn4 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.67 |

| BMn5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| BMn6 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| BMn8 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 4 |

| BMn10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | - |

| Phase Composition |

% wt. | Crystal Structure |

a(Å) | b (Å) | c(Å) | ß° | Unit Cell Volume (Å3) |

Crystallite Size (nm) * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMn0 | CaHPO4.2H2O | 100 | Mono. | 5.80 | 15.13 | 6.20 | 116.43 | 485.72 | 9804 |

| BMn2 | CaHPO4.2H2O | 100 | Mono. | 5.81 | 15.20 | 6.25 | 116.41 | 494.52 | 305 |

| BMn4 | CaHPO4.2H2O | 56 | Mono | 5.82 | 15.22 | 6.27 | 116.41 | 496.65 | 431 |

| MnHPO4(H2O)3 | 44 | Ortho | 10.41 | 10.86 | 10.91 | 90 | 1152.33 | 117 | |

| BMn5 | CaHPO4.2H2O | 29 | Mono. | 5.81 | 15.21 | 6.26 | 116.41 | 496.65 | 181 |

| MnHPO4(H2O)3 | 71 | Ortho | 10.41 | 10.86 | 10.19 | 90 | 1152.33 | 217 | |

| BMn6 | CaHPO4.2H2O | 19 | Mono | 5.81 | 15.19 | 6.24 | 116.41 | 493.43 | 321 |

| MnHPO4(H2O)3 | 81 | Ortho | 10.41 | 10.86 | 10.19 | 90 | 1152.33 | 358 | |

| BMn8 | MnHPO4(H2O)3 | 100 | Ortho | 10.41 | 10.86 | 10.19 | 90 | 1152.01 | 477 |

| BMn10 | MnHPO4(H2O)3 | 100 | Ortho | 10.41 | 10.86 | 10.19 | 90 | 1152.01 | 313 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).