1. Introduction

Continually evolving and resurfacing infectious diseases present significant and concerning risks to public health on a global scale. These diseases, whether they are newly emerging or re-emerging, encompass a variety of transmission modes such as vector-borne, zoonotic, airborne, or foodborne. Emerging infectious diseases are those that have recently manifested within a population or are rapidly spreading across geographic regions or experiencing a surge in incidence. On the other hand, re-emerging diseases refer to infections that resurface within a population after a period of significant decline [

1]. COVID-19, a respiratory tract infection caused by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), serves as a prime illustration of a recently emerged infectious disease. Originating in 2019, this disease swiftly escalated into a global pandemic and continues to propagate on a widespread scale to this day [

2]. The virus can be likened to a devastating force that impacts individuals without regard to their wealth, educational status, religion, color, race, gender, or social class [

3]. Hence, this global health crisis emphasizes the importance of integrated research and development efforts in the field of infectious diseases. These endeavors aim to address the gaps in medical microbiology, virology, and immunology, ultimately strengthening the response to public health emergencies [

1].

Despite over 40 months having elapsed since the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak and the widespread implementation of mass vaccination in numerous countries, achieving full control of the pandemic remains a considerable challenge [

4,

5,

6]. The sudden and unexpected emergence of COVID-19 has prompted the development of data infrastructures, such as patient registries, with the primary objective of documenting, gathering, and disseminating information pertaining to the virus [

7]. A clinical registry system holds great potential for evaluating patterns in healthcare delivery, conducting epidemiological surveillance, tracking clinical outcomes, promoting evidence-based therapy, describing the natural progression of diseases, and comparing the effectiveness of various interventions. Additionally, it can serve as a valuable tool for post-marketing drug surveillance [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] . To date, there is a notable absence of a comprehensive clinical registry specifically dedicated to COVID-19 in the Philippines.

Disease registry systems play a crucial role in establishing a robust information infrastructure for decision-making, such as providing valuable epidemiological and clinical insights, as well as facilitating research endeavors [

5,

13]. Designing a registry presents challenges, particularly in middle and low-income countries, as it is recognized as a time-consuming and resource-intensive endeavor [

13]. The implementation of a COVID-19 patient registry systems provides opportunities for studying the course of the disease which includes the following but not limited to identifying the prevalence and extent of the outbreak, studying disease complications, and deducing factors affecting response to treatments as well as outcomes. To a finer extent, a COVID-19 patient registry system may provide avenues to study the side effects of vaccines and to what extent these vaccines have been effective to the population [

5].

As of July 21, 2024, the recorded number of COVID-19 cases in the Philippines stood at around 4.14 million, accompanied by 66,864 deaths, resulting in a case fatality rate (CFR) of approximately 1.61% [

14,

15]. Despite indications of a decline in the number of COVID-19 cases in the country, there remains a notable scarcity of research concerning the clinical course of the disease specifically among Filipinos. The contribution of the Philippines to the existing knowledge on COVID-19, particularly in relation to its manifestation among Filipinos, is exceedingly limited. A recent search conducted on NCBI PubMed using the terms "COVID-19" and "Philippines" resulted in 1713 publications, whereas using the term "COVID-19" alone generated 440,559 publications (as of August 8, 2024). These figures suggest that publications focusing on COVID-19 within the Philippines constitute a mere 0.37% of the total studies published in PubMed.

While individual institutions have conducted research using their own patient data, there is a need for a more comprehensive analysis that includes a larger and more representative population of Filipino patients. This is crucial in order to establish effective guidelines and policy recommendations. One of the challenges hindering COVID-19 research in the country is the absence of a centralized COVID-19 patient data repository. To address this gap, the present study aims to set the stage for developing a patient registry by collaborating with several hospitals in the regional setting (e.g., Western Visayas region) of the Philippines. These hospitals include The Medical City Iloilo (TMCI), West Visayas State University Medical Center (WVSUMC), and Corazon Locsin Montelibano Memorial Regional Hospital (CLMMRH). By pursuing this direction, there is potential to identify clinical management practices that are most suitable for Filipino patients.

The establishment of a COVID-19 patient registry system is crucial, which should encompass key data elements such as demographic information and comprehensive clinical data including chief complaint, history of present illness, review of systems, past and family medical history, personal and social history, laboratory tests and imaging, assessment, plan, patient outcome, and notable clinical events. While recognizing the potential challenges in establishing a national-level registry, initiating this plan in regional setting such as in Western Visayas, Philippines offers a potentially important milestone towards the success of such infrastructure. Establishing a regional COVID-19 patient registry as a preliminary step is considered to be more advantageous than that of establishing one at the national level since the former allows us to study the differences in case fatality rates and compare these among regions. Further, studying at the regional level will allow us to investigate the disparities in COVID-19 testing among regions during the early part of the pandemic which may have persisted for a long time.

2. The clinical course of the COVID-19 disease

The progression of COVID-19 in a hospital setting is influenced by various factors, including age, sex, pre-existing medical conditions, treatment methods used at different stages of the disease, and potential complications. Additionally, health outcomes can be influenced by the specific COVID-19 variant responsible for the infection and the patient's ethnicity, which may involve genetic factors that either provide protection or increase susceptibility to the disease. Outside of the hospital, factors in the community setting, such as socioeconomic conditions, history of exposure, and vaccination records, can also impact the clinical course of COVID-19. This study will primarily focus on investigating the factors related to both hospital and community settings that influence the clinical course of COVID-19 in Filipino patients (

Figure 1).

2.1. COVID-19 in Filipino patients

As of July 11, 2024, PubMed has already published a total of 436,436 articles covering various aspects of COVID-19 studies, including disease mechanisms and clinical management, among others. Filtering the data search to only include the keywords ‘COVID-19’ and ‘Philippines’ yielded 1,688 published studies in PubMed. Such studies are focused on psychological [

16,

17], social and behavioral [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] , and epidemiological aspects of the disease [

23,

24]. Additionally, there are case reports available that specifically focus on COVID-19 patients with comorbidities [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Several observational studies have been conducted to examine the clinical status and management of COVID-19 in Filipino patients [

24,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. The Philippine CORONA study is currently underway to conduct a thorough evaluation of the neurological aspects of COVID-19. This retrospective, multicenter study aims to identify and analyze the neurologic manifestations of the disease specifically in Filipino patients [

36]. Another study investigated the various clinical biomarkers and cytokines that may be associated with COVID disease progression and the mortality rate using a cohort of patients in the hospital with confirmed moderate to severe COVID-19 infection [

37].

The initial studies examining the clinical course of COVID-19 in Filipino patients were conducted by The Medical City (TMC), a private tertiary hospital, and San Lazaro Hospital (SLH), a public tertiary hospital, both located in Manila, Philippines. These studies utilized a dataset comprising patients who were admitted between January and October 2020.

TMC conducted a documentation of its intensive care unit (ICU) experience during the initial two months of the pandemic. Among the 91 probable COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU, 31 (34%) tested positive in the

real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test, and unfortunately, 22 of these patients succumbed to the disease. The age group of these patients ranged from 50 to 80 years, with a lower representation of males. However, neither age nor sex showed a statistically significant association with COVID-19 positivity or ICU survival. The COVID-19 positive group exhibited a higher prevalence of cardiac and endocrine comorbidities, but these conditions did not correlate with mortality. Laboratory values on the day of admission revealed significantly higher Hgb levels, lower white blood cell counts, and P/F ratios in the COVID-19 positive group. Additionally, elevated lactate levels prior to ICU admission were significantly associated with non-survival. The clinical management of patients included antiviral treatment and various modalities to address respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and cytokine storm. However, no survival benefit was observed with the interventions employed [

30].

During the initial wave of a novel pandemic, healthcare systems face uncertainties, and the typical strategies for patient management rely on best practice guidelines from other countries. In the absence of local guidelines during that period, TMC successfully leveraged the experiences of emergency departments in New York City, USA, and Sao Paulo, Brazil. This enabled the development of protocols aimed at addressing two key objectives: 1) managing the surge in ICU admissions effectively, and 2) optimizing mechanical ventilation settings to achieve the best outcomes for patients [

30,

38,

39].

In a separate study involving the analysis of the first 40 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patients at TMC, it was observed that the majority of patients were males (57.5%) and fell within the age group below 60 years. Upon admission, most patients were classified as moderate risk (67.5%). Among the patients in the high-risk group, all 8 individuals developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), 6 developed acute kidney injury (AKI) necessitating renal replacement therapy, 5 experienced septic shock, and 2 acquired nosocomial infections. Complete recovery was observed among patients classified as low risk, while 6 patients from other risk groups unfortunately succumbed to the disease. The majority of patients had at least one comorbidity, with cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus being the most commonly observed conditions [

33]. Patient data from the initial 100 suspected COVID-19 cases admitted to SLH between January 25 and March 29, 2020, were analyzed. Out of this group, 42 cases were confirmed, including 40 Filipinos and 2 Chinese nationals. The majority of confirmed cases were aged 60 years and older, while approximately one-third fell within the 41-59 age group. Upon admission, these cases exhibited difficulty breathing and had at least one underlying condition, with diabetes mellitus being particularly prevalent. Among the confirmed cases, 9 patients unfortunately succumbed to the illness, with the majority of deaths occurring within a week of admission and within 18 days of the onset of symptoms [

23]. These initial studies lack sufficient statistical power to establish any significant associations with disease progression and mortality. However, they do provide evidence of local transmission of COVID-19 in the densely populated regions of Metro Manila. The study conducted at SLH highlights the impact of factors such as small living spaces, social interactions within extended families, and overcrowding in slum areas, which contribute to a heightened risk of community transmission. These findings emphasize the need for effective public health interventions to mitigate the spread of the virus in these vulnerable communities [

23]. An additional analysis was conducted on the initial 500 laboratory-confirmed cases admitted to SLH between January and October 2020. This study comprised 133 healthcare workers (HCWs) and 367 non-HCWs. Among the HCWs, the confirmed cases were predominantly categorized as mild to moderate in severity, with cough being the most frequently reported symptom (60.1%). As anticipated, a significant proportion of the HCWs had a history of exposure within the high-risk transmission setting of their workplaces. Within the HCW group, there was one reported death (0.7%). In the non-HCW group, the patients who succumbed to the disease were predominantly in the 61-80 age range and were more likely to be male. Compared to those who recovered, these patients were more likely to present with difficulty breathing upon admission. It is important to note that this study did not explore the potential benefits of specific treatment modalities [

34].

Although the studies mentioned earlier touched upon certain demographic and clinical characteristics of patients, there remains a need for a more extensive analysis utilizing a larger and more diverse dataset. It is worth noting that these studies did not specifically address the younger patient population, which now constitutes the largest proportion of COVID-19 infections in our population, particularly individuals aged 25-29 years. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the disease and its impact on different age groups, it is crucial to include a representative sample of younger patients in the analysis, ensuring that their unique characteristics and experiences are adequately captured [

40].

In the context of a pandemic, research studies examining the impact of treatment modalities, including vaccination, on disease progression play a crucial role. These studies provide valuable insights that guide resource allocation towards the most effective strategies. Additionally, in the context of being a developing country, it is important to investigate socioeconomic factors that contribute to inherent health disparities. Factors such as poverty, nutritional status, and limited access to diagnostic testing and emergency medical response for acutely ill patients are social determinants that necessitate careful consideration and examination. Understanding the influence of these social factors is essential for implementing targeted interventions and addressing health inequalities in the population.

2.2. COVID-19 Data Sources in the Philippines

The Department of Health (DOH) has implemented the COVID KAYA System to handle COVID-19 data in the Philippines [

41]. Its primary users are registered health workers involved in contact tracing and case monitoring. They encode relevant patient information (e.g., identifiers, addresses, testing) using the online Case Information Form (CIF). Contact tracing data is continuously being migrated from StaySafe.PH into the system for integration. However, no clinical patient data is handled by the COVID KAYA nor StaySafe systems. Patient data are stored as paper or electronic health records in different hospitals across the country. In general, COVID-19 related datasets in the Philippines contain confirmed cases and related information such as the basic demographics (e.g., age, sex, residence, disease status (recovered, died, or admitted), with or without exposure, as well as the type of exposure, and other relevant dates (data announced, date recovered, and date of death)) [

42]. Humanitarian activities by civil society organizations, private organizations, and government are also available [

43])). Another COVID-19 data source in the Philippines is the Salvacion Study (Surveillance and Analysis of COVID-19 in Children Nationwide) which aims to collect retrospective and prospective data on the epidemiologic profile, clinical and laboratory features, treatment, and outcome of COVID-19 in children through a pediatric COVID-19 registry [

44,

45]. This passive COVID-19 registry is primarily limited to children no more than 18 years old[

46]. Overall, COVID-19 case information are available but only contain very limited information primarily focused on the demographics of the individuals or an aggregate data [

46,

47,

48]. In order to effectively study the clinical course of the disease especially among Filipino patients, more information which includes clinical, epidemiological, and even genetic data at the individual level are needed.

2.3. COVID-19 Data Sources outside the Philippines

Several open resources repository for COVID-19 research are available outside of the Philippines but are primarily focused on aggregated datasets without any clinical information for each patient. Such datasets include information on daily cases, population mobility, social media, climate, health facilities, policy and regulation, research articles, and global news [

49]. In a separate research investigation, conventional public health surveillance measures like reported cases, deaths, and hospitalizations, along with numerous supplementary indicators of COVID-19 activity, such as signals derived from deidentified medical claims data, large-scale online surveys, cell phone mobility data, and internet search trends, are readily accessible without cost [

50]. In another research study, a repository is also available which provides multimodal information of news articles related to COVID-19 including temporal, visual, textual, and network information [

51]. Accessing various articles to provide a one-stop shop for COVID-19 evidence is even made easier by using a free access repository and classification platform [

52].

Within the federal government, the US Center for Disease Control is collecting data about hospital’s daily COVID-19 census and capacity as well as mortality information [

53,

54]. Further, the US Food and Drug Administration and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences / National Institutes of Health have initiated the CURE ID app/web platform that allows the clinical community to report novel uses of existing drugs for patients with diseases which are difficult to treat including that of COVID-19 [

53,

54].

2.4. Existing patient registries for COVID-19

Across the globe, operational COVID-19 patient registries have emerged, yielding valuable clinical datasets derived from patient information. Collaborating with statisticians, physicians and scientists from Weill Cornell Medicine have established a COVID-19 patient registry comprising records from 4,000 patients [

55]. Information was generated from reviews of patient records in 3 hospitals: NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center Hospital, New York-Presbyterian Queens Hospital, and NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital. With this database, researchers were able to publish 20 peer-reviewed papers within 6 months of the registry’s implementation. Some of the topics were on the clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients [

56] comorbidity risks for patients with cardiac [

57] and oncological diseases [

58] and the effect of viral particle quantity on mortality [

59]. Additionally, within the United States, the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) Center provides the largest repositories of safeguarded and anonymized clinical data specifically for COVID-19 research [

60]. The N3C contains the largest, most representative cohort of COVID-19 cases in the United States to date. It is known to be a centralized, harmonized, multi-center dataset, with a high-granularity electronic health record repository. Further, it contains evidence-based development of various predictive and diagnostic tools with the capability of informing critical policy and care [

61]. Further the University of Michigan’s Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation are working with researchers around the world to develop COVID-19 patient registries to better understand the disease [

62].

In Berlin, an ongoing study known as Pa-COVID-19 is dedicated to generating a dataset of patient information specifically for clinical, molecular, and immunological phenotyping studies [

63]. The creation of this dataset aims to facilitate the generation of prompt evidence for the identification of innovative and efficient treatment and preventive measures, as well as expedite the implementation of future drug trials in Germany. Additionally, there are initiatives underway to establish patient registries targeting specific patient populations. For instance, the Thoracic Cancers International COVID-19 Collaboration (TERAVOLT) group has developed a patient registry to investigate the effects of COVID-19 on the management and health outcomes of thoracic cancer patients [

64]. Patients from a total of 42 institutions spanning across 8 countries (Italy, Spain, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, USA, UK, and China) were successfully enrolled in their registry.

Numerous Asian countries have also released research papers based on extensive patient datasets obtained from registries. In Malaysia, a significant observational study (n = 5889) was conducted to document the clinical characteristics and risk factors among patients affected by COVID-19 [

65]. The study encompassed admissions in 18 hospitals across Malaysia between February and May 2020. Researchers utilized the REDCap database to collect the required data for analysis. Similarly, in Indonesia, a comparable study was conducted on 4,265 patients admitted to 55 hospitals from March to July 2020 [

66] . Patient records were organized in a surveillance database before undergoing analysis. Presently, an ongoing study named "The Pediatric Acute and Critical Care COVID-19 Registry in Asia (PACCOVRA)" is underway. This registry collects pediatric patient data for analysis, with an estimated enrollment of 2000 patients. The study commenced its operations in May 2020 and will continue until December 2023. Study sites are located in Thailand, Singapore, Japan, China, Malaysia, and the Philippines [

67].

3. Western Visayas, Philippines

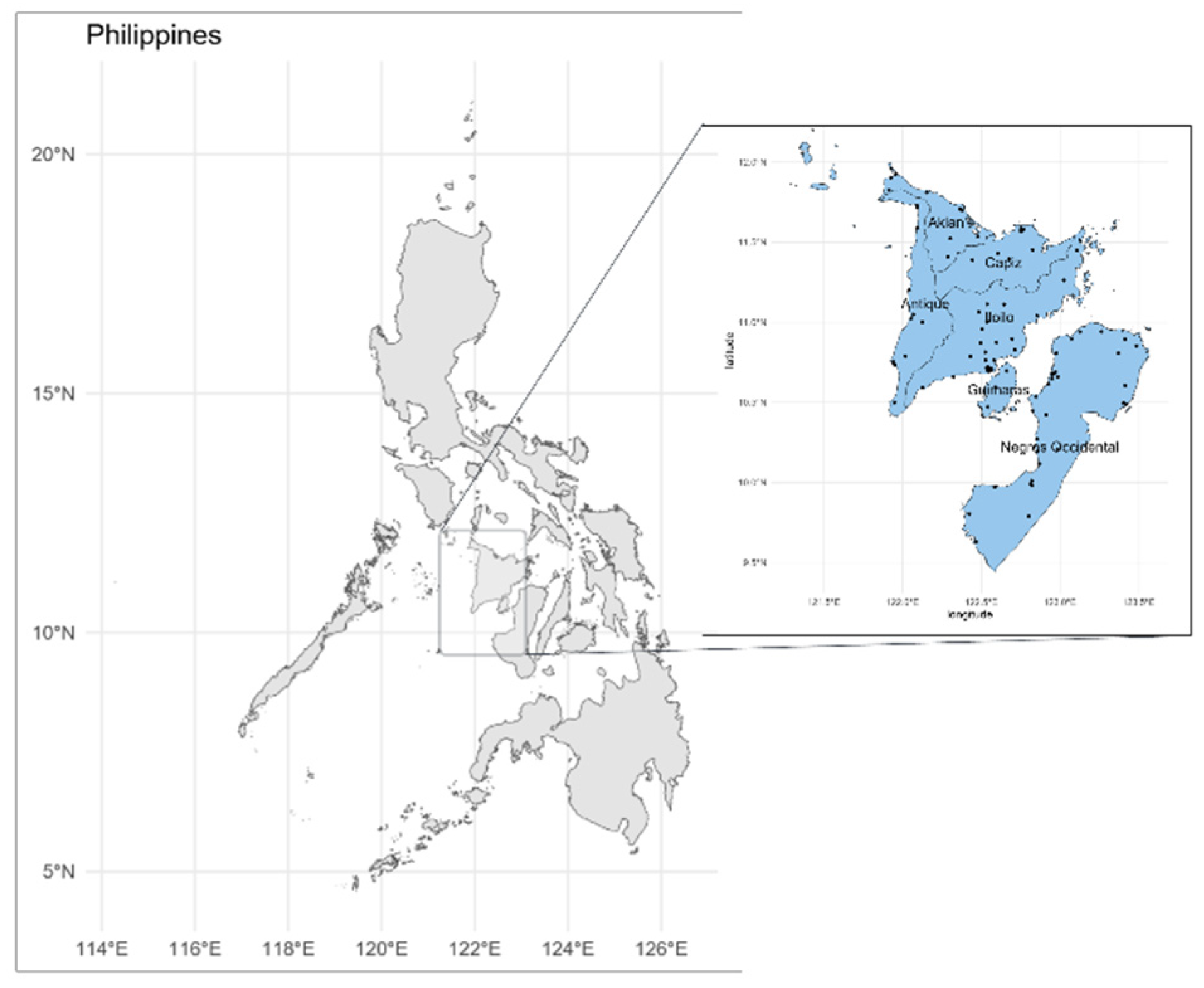

In the Western Visayas region of the Philippines, there are a total of 99 functioning hospitals. Despite the predominance of paper records rather than electronic health records, these hospitals have significant potential to contribute valuable information to the proposed COVID-19 patient registry system.

Figure 2 illustrates a map of the Philippines, with the Western Visayas region positioned at the country's center (left), and the 99 hospitals in the region (right). The Western Visayas region, an administrative division in the Philippines, consists of 6 provinces, 2 highly urbanized cities, 117 municipalities, and 4,051 barangays (the smallest administrative division). Based on the projected census of 2020, the estimated population of the region is 8 million individuals. With an average annual population growth rate of 1-1.5% and a wide range of prevalent diseases, including acute upper respiratory infection, hypertension, pneumonia, and influenza as the leading causes of morbidity according to 2017 statistical data, there is a compelling rationale and motivation to explore the impact and feasibility of conducting a COVID-19 patient registry within the aforementioned region.

It should be noted that there is no existing COVID-19 patient registry system involving clinical data in the Western Visayas region. The only registry system available is an online database COVID-19 vaccination information wherein patients are interviewed and asked basic demographics questions, and information is forwarded to the Department of Information and Communications Technology

Establishing a COVID-19 patient registry within the regional setting will allow us to enhance the health outcomes of Filipino COVID-19 patients focused within the region. This effort will consequently serve as a baseline that can even be expanded within the national level, thereby contributing to the overall pandemic response in our country. Recognizing that direct efforts aimed at establishing a disease registry at the national level may present significant challenges, we do believe that initiating such effort by starting at the regional level will be more attractive since fewer entities (i.e., stakeholders) are involved in the process. Consequently, the consolidation of standardized COVID-19 patient medical records from a wide range of healthcare institutions from various regions throughout the country will facilitate this important feat towards the national level. Thus, to accomplish this task in the Philippines, we initiate a collaboration with COVID-19 designated government hospitals, as well as early responders among private hospitals, particularly in the Western Visayas region as a start.

By employing this strategy, there is a justifiable anticipation that the aggregate data collected will yield significant findings pertaining to COVID-19, particularly tailored to the Filipino population, including the Western Visayas region. These discoveries will contribute to our collective efforts in combating and managing this disease effectively.

3.1. Barriers in establishing a COVID-19 patient registry in a regional setting

Undoubtedly, the implementation of a COVID-19 patient registry brings numerous advantages from a public health standpoint. These advantages become even more crucial in a specific area like Western Visayas, where the presence of endemic illnesses such as tuberculosis, dengue, and X-linked dystonia-parkinsonism necessitates additional research to uncover common mechanisms among diseases and gain a deeper understanding of the genetic factors influencing human ailments. This approach not only validates significant biological discoveries but also holds potential as a tool for aiding drug development by shedding light on the mechanisms of action [

68,

69,

70]. However, there are still obstacles to overcome in creating a COVID-19 patient database in an underdeveloped area such as Western Visayas in the Philippines. Nonetheless, there are also potential advantages in establishing the said registry in the region. For instance, numerous regional hospitals have expressed their enthusiasm for implementing this database. Additionally, several regional research centers including the Center for Natural Drug Discovery and Development, the Center for Chemical Biology and Biotechnology, and the Center for Informatics at the University of San Agustin have been established in recent times which alludes to the active research activity within the region [

71]. Further, the Philippine Genome Center Western Visayas located in the same region also warrants a possible collaboration with the aforementioned centers [

72]. These centers have the necessary equipment and facilities necessary to perform COVID-19 related research (e.g., genome sequencing, contact tracing, assessing the capacities of the Western Visayas Medical Center’s facilities and technicians for accreditation and compliance by the Department of Health [

73,

74,

75,

76].(

Table 1).

3.1.1. Minimum dataset requirement

Different studies have different suggestions for the minimum dataset (MDS) requirement for the establishment of a COVID-19 patient registry. In one study, MDS which includes eight major groups consisting of 434 data elements from administrative, disease exposure, medical history and physical examination, findings of clinical diagnostic tests, disease progress and outcome of treatment, medical diagnosis and cause of death, follow-up, and COVID-19 vaccination data categories are necessary in order to create a standard and comprehensive MDS to help design a national data dictionary for COVID-19 [

4]. In another study, it was found that the MDS requirement for COVID-19 registry should include the administrative part with 3 sections, including 30 data elements, and the clinical part with 4 sections, including 26 data elements [

8]. Zarei and colleagues conducted an intricate and detailed study on a study protocol and lessons learned from the pilot implementation of a regional COVID-19 registry in Khuzestan, Iran. Findings of their study show that a series of steps were considered in such project implementation. That is, the initial dataset was prepared by reviewing various forms such as the electronic and paper-based COVID-19 data collection and reporting forms, as well as the COVID-19 diagnosis guidelines of the Ministry of Health of Iran [

5]. The dataset was further finalized by considering the opinion of various health experts (Regional COVID-19 registry in Khuzestan, Iran: A study protocol and lessons learned from a pilot implementation - ScienceDirect). The Western Visayas hospitals may not have the necessary data elements required for MDS related to COVID-19 as of the moment since a COVID-19 patient registry has not been initiated yet. However, moving forward this information will be very valuable moving forward.

3.1.2. Data collection and IT infrastructure

The establishment of a COVID-19 patient registry especially in a regional setting requires the collaboration among various participating hospitals or centers. Such centers will have admitted COVID-19 patients which will be included in the registry after written consent and ethics review [

77]. Further, there are challenges related to the data collected by each hospital institution which includes lack of common data elements, variation in the data collection methods, and registries not capturing the entire patient journey [

54]. Other considerations that should be considered include sharing and privacy of medical data within the scope of COVID-19 [

78], internet connectivity, as well as the presence of computer devices especially in rural local government units. Since a registry software would require good internet connectivity, internet privileges may not be available in rural areas of the Philippines, thus, limiting the ability to reach people without internet access [

79].

3.1.3. Personnel and costs

Dr. Kenneth Gersing, head of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or NCATS, in the United States expressed that funding remains the largest obstacle in continuing the work done for the National COVID Cohort Collaborative, better known as N3C [

80]. The United States’ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) published findings that estimated up to two additional staff members would be required to effectively manage a patient registry for Clinicaltrials.gov [

81]. AHRQ also determined a cost of over

$1 million USD to fund the setup and maintenance of said patient registry in the United States [

81]. Finding an existing database management team within an organization would be desirable in seeking costs-savings with respect to a COVID-19 patient registry system in the Philippines. This comes with a challenge as the team requires expertise in COVID-19 and related technical fields. Fortunately, this problem is mitigated by the introduction of the Balik Scientist Program of the Department of Science and Technology in the Philippines. The program is open to Filipino experts who are willing to come back to the Philippines and share their expertise to accelerate the country’s development [

82]. However, the poor compensation and salary in the Philippines discourages highly trained Filipino scientists to come and share their expertise in the Philippines [

83].

Further, inadequate institutional support, including administrative and infrastructural issues, can hinder the research process and the overall sustainability of scientific endeavors. Challenges related to bureaucracy, the allocation of funds, and effective implementation can still impact the success of these initiatives [

84].

3.1.4. Implementation

One idea for cost-savings in implementation design would be to collect data through individual participants self-testing. In the case of HIV/AIDS, HIV self-testing has proven to be very effective and widely used in Metro Manila in the Philippines[

84]. Additionally, the impact of widespread HIV testing has provided support for public health effectiveness in tracking and monitoring HIV incidence [

85].

As COVID-19 testing kits become more accessible to the wider public, existing digital health applications on mobile devices could be used to gather data on exposure and positive status. Such digital health applications have already launched in the Philippines since the early days of the pandemic, however limited-user engagement poses challenges to relying on this method [

86]. Public fear and anxiety surrounding reports of positive COVID-19 status coupled with strict quarantine measures enforced make self-reporting and disclosure unlikely [

87].

The implementation of a COVID-19 patient registry in a regional setting in the Philippines comes with other challenges besides the aforementioned concerns. The project requires a significant amount of funding unless various hospitals would be willing to leverage resources (i.e., sharing of data) and would be open to using a unifying platform to input various clinical and demographic information. Further, data should also be ensured of its quality and accuracy and that any redundant information should not be included. Variability in data quality and completeness could affect the reliability of the registry. In regions with limited technological infrastructure, there might be issues related to internet connectivity, electronic health record systems, and data security, which could hinder the timely and secure transfer of patient information. Collecting and managing patient data while adhering to privacy regulations and ethical considerations is critical. Balancing data utility with patient privacy can be complex, especially in a regional context where there might be varying levels of awareness about data protection. The Philippines is an archipelago with diverse healthcare settings, ranging from urban centers to remote areas. Disparities in healthcare access and resources could result in incomplete or biased data representation. Adequate staffing and training are essential for data collection, entry, and management. Regions with limited healthcare workforce might struggle to allocate human resources for maintaining the registry effectively. Lastly, there are also concerns related to the willingness of the hospitals to participate due to issues related to confidentiality.

When establishing a COVID-19 patient registry, it's crucial to address the challenges proactively and leverage the opportunities to ensure that the registry becomes a valuable tool for both immediate pandemic response and long-term healthcare improvements [

88].

4. Moving forward: Proposed program implementation

Designing a COVID-19 patient registry can be considered to be a resource-intensive and time-consuming process particularly in middle- and low-income countries. Akin to the methods established by Rodriguez et al [

89], we systematically discuss herein the proposed implementation process for the establishment of a COVID-19 patient registry. The integration of the proposed registry into existing clinical protocols, along with a comprehensive intervention strategy encompassing educational outreach to staff, patients, and providers, can effectively overcome barriers to program implementation, as encountered in this study [

52].

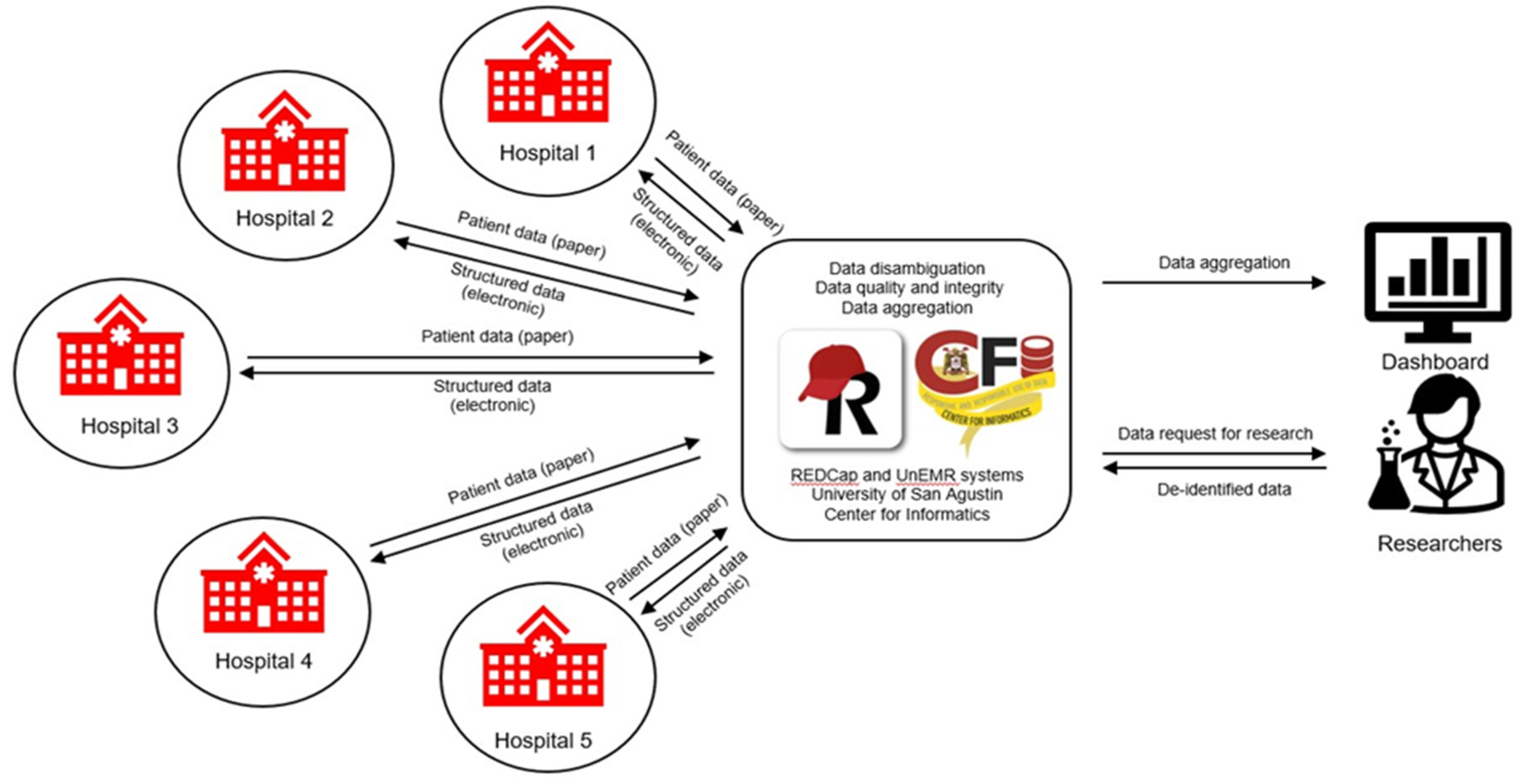

The COVID-19 patient registry, as outlined in

Figure 3, will adhere to a defined flowchart. If implemented successfully, this registry will fulfill the increasing demand for high-quality, research-ready data pertaining to COVID-19 patients in the Philippines. Scientists and researchers will leverage this data to conduct studies on various subjects such as disease phenotypes, clinical progression, risk factors, patient care, treatment response, diagnostics, vaccines, health outcomes, and artificial intelligence/machine learning applications, among numerous other topics.

4.1. Data collection.

For the retrospective cohort, patient data from confirmed cases will be gathered through a thorough review of medical charts. Each hospital will provide a list of confirmed cases to be included in the review. As previously mentioned, patients in the prospective cohort will be identified accordingly. Prior to entering patient data into the registry, a signed informed consent will be mandatory. Only de-identified will be shared with the team members for further analysis and modeling. To facilitate data collection, an electronic tool will be developed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software [

34,

35]. REDCap has also been successfully used as the data collection platform for the American College of Surgeons COVID-19 registry since it is considered to be a known system and is also widely accessible to many hospitals [

90]. The consortium, in collaboration with the University of San Agustin – Center for Informatics (USACFI), will take responsibility for the development and implementation of this tool while USACFI acts as the data steward. In addition to the data fields available in hospital records, the tool will also incorporate data fields from the Case Report Form of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium/World Health Organization (WHO). The following dataset will be collected: A) Demographic Data, B) Clinical Data (Chief complaint, History of Present Illness, Review of Systems, Past Medical History, Family Medical History, Personal and Social History, Laboratory Tests and Imaging, Assessment, Plan, Patient Outcome, Notable clinical events). Previous studies have shown that a wide multitude of factors can be used as predictors of COVID-19 outcomes. In one study, demographic, clinical, immunologic, hematological, biochemical, and radiographic findings may be of utility to clinicians to predict COVID-19 severity and mortality [

91]. In another study, lymphopenia, prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time, high international normalised ratio, high D-dimer, and high creatine kinase were found to be valuable prognostic predictors of the severity of the disease at early stages that can determine a COVID-19 outcome [

92]. Related to COVID-19 symptoms, fever, dyspnea, weakness, shivering, C-reactive protein, fatigue, dry cough, anorexia, anosmia, ageusia, dizziness, sweating, and age were also found to be important predictors of COVID-19 in another study [

93,

94,

95,

96,

97]. In general, the feasibility of data collection will depend on the availability of information, accessibility, as well time available for gathering [

89].

4.2. Data quality

Quality control of clinical data is a concern when it comes to establishing any national patient registry. Several low- and middle-income countries have already examined issues concerning data quality in COVID-19 patient registries, including Iran [

5], Brazil [

98], and India [

99]. One shared concern in maintaining quality standards was the lack of consensus within each nation regarding what specific data to collect and how to implement those standards across all testing sites.

RECOVID-19, a registry of COVID-19 patients within a tertiary healthcare center is an example of effective utilization of COVID-19 patient data to have a positive impact on the wider community. The RECOVID-19 registry has increased access to up-to-date and accurate data for COVID-19 and facilitated research and policy and decision-making in Cali, Colombia - a city of approximately 2.2 million [

89]. Additionally, the authors reported that even though the data is only collected from one single hospital that serves just over 800,000 patients, their study had a sample size greater than several multi-hospital studies previously published.

In the Philippines’ Western Visayas region where efforts have been made to measure basic demographic information, the issue remains that clinical data cannot be used to determine comorbidity across COVID-19 patients. Thus, it is important to shift the mindsets and behaviors of healthcare professionals towards good documentation practices and practice gathering good quality data from a primary care level [

100].

There are large barriers to research in the Philippines stemming from heavy reliance on paper medical records [

101]. Both technically and logistically, the country is still largely in transition towards widespread utilization of electronic medical records (EMR) that would greatly facilitate both handling and analysis of data [

101]. Other areas of concern related to data quality include introducing technological infrastructure and implementing safeguards and data validation for EMRs would systematically increase quality of data gathered and stored. Further, enabling full interoperability within and between population-based patient registry domains would open opportunities for rich source of secondary data usage [

102]. In doing so would require addressing many organizational and technical challenges including data semantics, security, data format, standard services, and individual data matching to name a few [

103].

4.3. Data curation and management

Data curation and management are very essential considerations in the establishment of a COVID-19 patient registry. The University of San Agustin-Center for Informatics (USA-CFI) located in Iloilo City, Western Visayas region of the Philippines can develop automated scripts to extract and ingest data securely emanating from various hospitals in the region that contributes to COVID-19 patient data. Such data can be in the form of PDFs or spreadsheets. The information in a patient’s record is curated into the REDCap database by medical data curators trained by the consortium on data security and privacy, data dictionary, and curation rules. Whatever data a hospital contributes is returned to them digitized, i.e., structured and research-ready, for their own analyses (

Figure 3). Aggregate data will be disambiguated (i.e., duplicate/multiple records will be reconciled, in the case a patient has records across several participating hospitals) before finalization to ensure good data quality. The contents of the research database will be the finalized data, which will then be summarized in the dashboard. A query interface will then be developed to facilitate researchers finding data for their analyses (cohort discovery). A dashboard/graphical user interface will also be publicly accessible for reporting patient aggregate data.

A data access group will be established for each hospital to guarantee that access within REDCap is limited to the hospital's own data. This measure ensures that hospitals cannot casually view data from other institutions. They will only be able to engage with deidentified data from other hospitals through research activities subject to appropriate permission, authentication, and audit trails to ensure responsible use. Interactions with aggregate data will be facilitated by the research program, which will grant access based on the evaluation of research proposals.

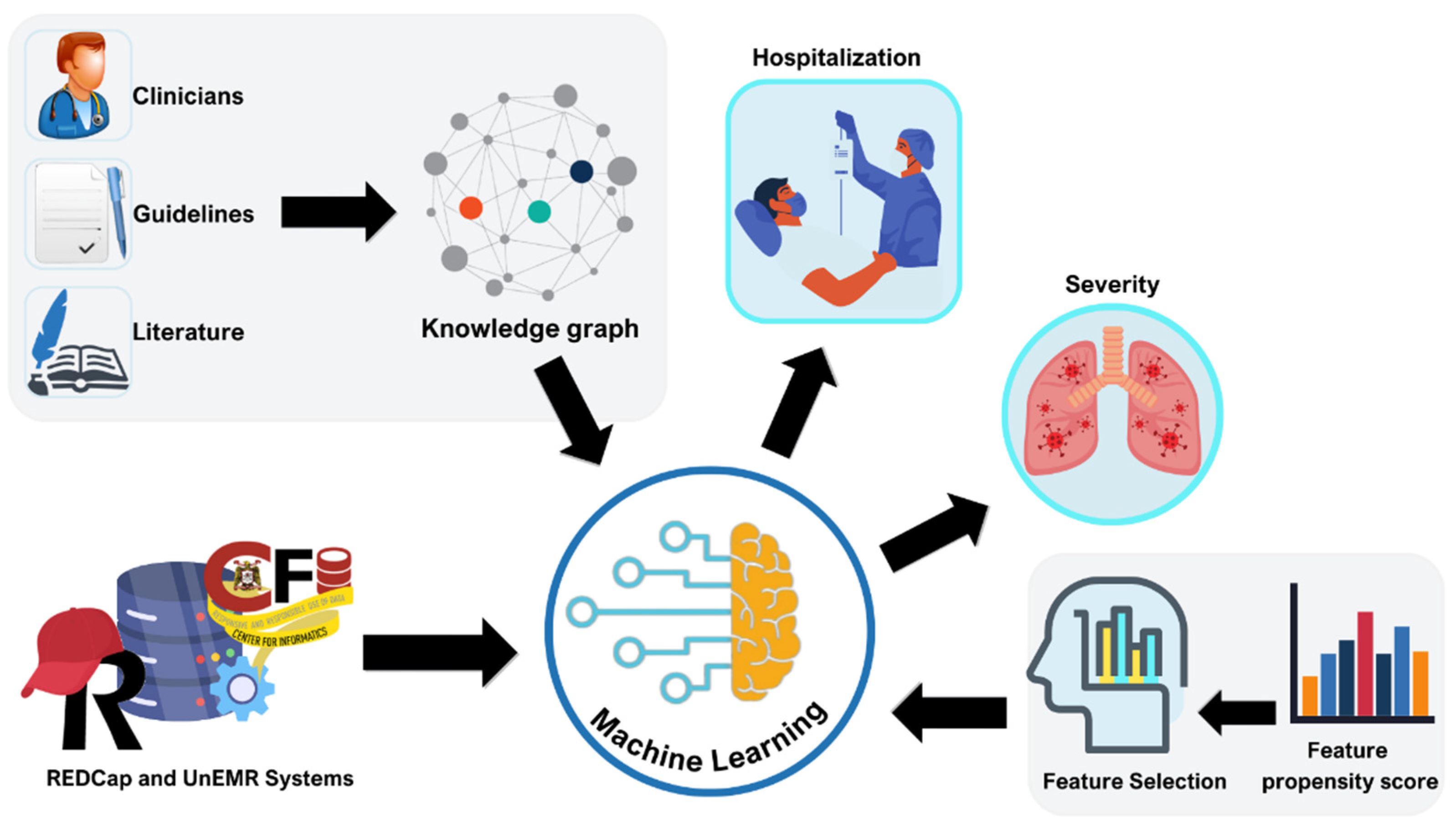

4.4. Data analyses

The dataset will be utilized for both descriptive and analytical studies, examining patient profiles, outcomes, treatment effectiveness, and interventions. The findings from descriptive studies will be presented in the form of counts, percentages, and/or proportions, with simple univariate statistical tests (parametric and non-parametric, used as appropriate) applied to examine factors on an individual basis. For analytical studies, we will utilize multivariable regression techniques to examine the statistical association between outcomes/endpoints of interest (e.g., hospitalization, severity) and potential explanatory variables. In addition, machine learning techniques will be used to develop predictive models for endpoints of interest. These approaches could be used to produce outcome-specific risk scores that can be used to stratify individuals into risk levels, based on various prognostic factors (

Figure 4) [

104]. As part of this research, we will explore and compare various machine learning algorithms – comparisons will be carried out on various metrics such as predictive accuracy (on held-out validation data), computational resource demand, etc. Prior to analytical studies and predictive modeling, data cleaning methods will be used to sanitize and standardize the data, and imputation techniques will be explored for handling potential missing values. Close collaboration between expert clinicians and scientists will ensure clinical correlation of the findings and the identification of best practices derived from the study. Since this primarily serves as a descriptive study and due to the uncertainty of the ongoing pandemic, there is no minimum sample size requirement. Pooling patient data from multiple hospitals will enhance statistical power compared to analyzing them individually (

Figure 4) [

104]. The analysis will involve all patients registered by the end of the study. Establishing the registry at present offers the advantage of increasing statistical power over time as more patients are enrolled, extending beyond the study period.

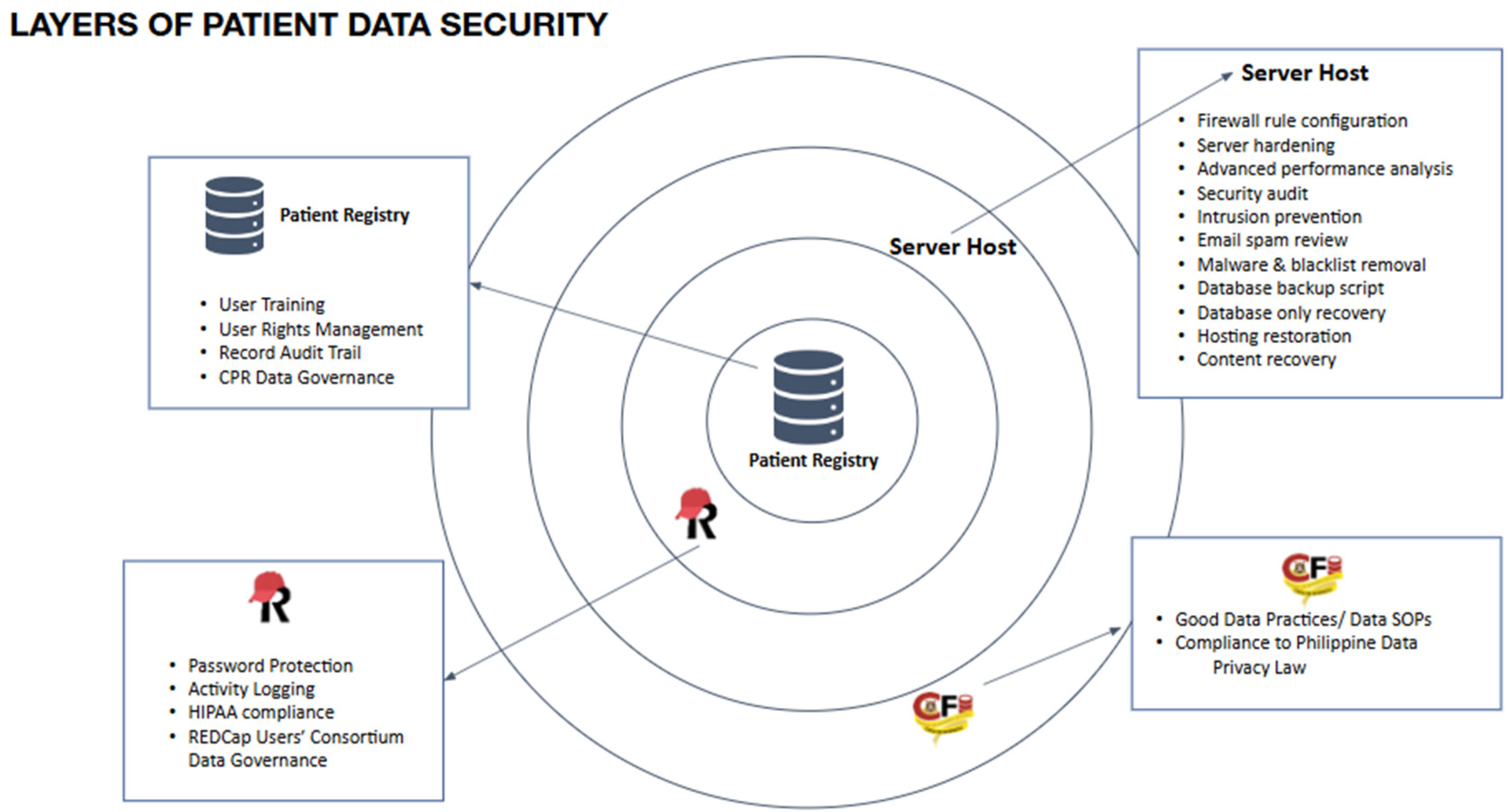

4.5. Security and Confidentiality of data

Figure 5 demonstrates the robust security measures implemented in the proposed infrastructure to safeguard patient data. The confidentiality of the Comprehensive Patient Record (CPR) is upheld through multiple layers of security protocols. Our personnel will receive training in proper data practices, following the established standards of the USA-CFI. These practices will be extended to hospital participants, ensuring ethical handling of protected health information. Patient records will be digitized and curated within the respective hospital premises where they are stored. Prior to release, all patient data used for research purposes will undergo de-identification. Access to data not displayed on the dashboard will be limited to researchers with approved research proposals. Limited data access may be granted to for-profit health entities, provided that the preservation of public health interests is maintained in the data use agreements. All processes concerning data management will undergo review by accredited research ethics committees of member hospitals prior to implementation. This study's privacy and confidentiality measures will adhere to Republic Act 10173, also known as the Data Privacy Act of 2012.

The data governance document will function as a reference for guiding the planning and execution of all data-related activities within the consortium. Philippine hospitals interested in contributing their patient data and joining the COVID-19 patient data consortium can access a publicly available CPR Information Packet for viewing purposes.

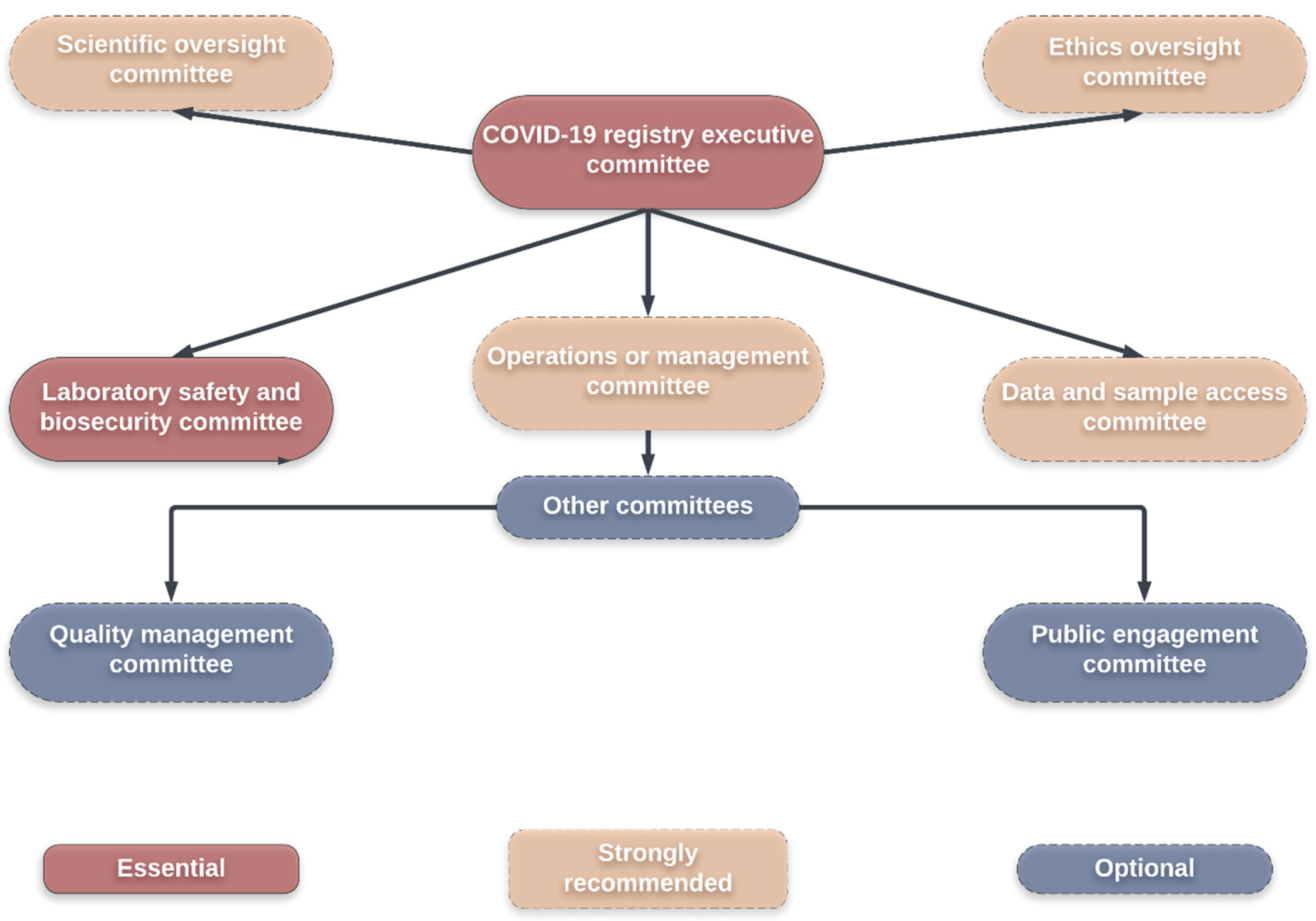

Typically, creating a COVID-19 patient registry necessitates a governance structure akin to a biobank, operating in response to sociocultural obstacles. Consequently, it entails establishing trust, conducting delicate negotiations, and fostering acceptance—a framework that effectively connects research with society and politics [

53]. Significant advancements in biobank research have yielded two innovative approaches that hold promise for addressing the complex social, legal, and ethical challenges associated with biobank research. These approaches are particularly relevant in establishing a COVID-19 patient registry in Western Visayas. The first approach focuses on public engagement and consultation, incorporating diverse methods such as interviews, community advisory groups, and public meetings. The second approach centers around the development of robust governance structures that effectively tackle concerns pertaining to social, legal, and ethical aspects [

54].

Figure 6 illustrates a suggested committee framework for internal governance within a biobank [

55].

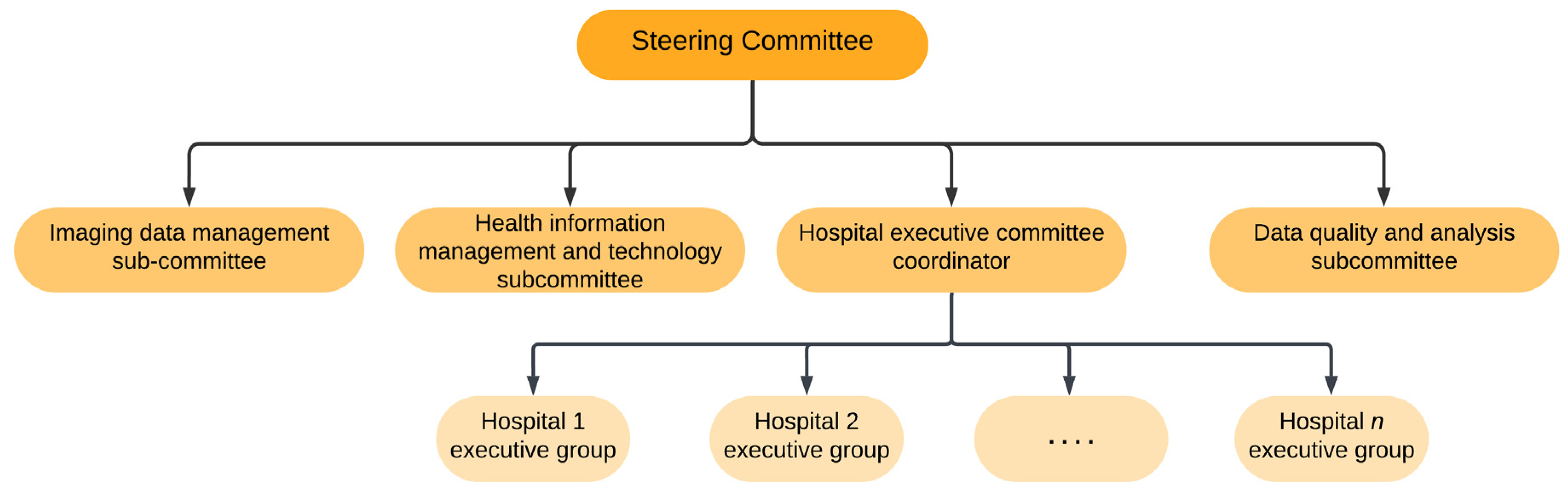

However, the establishment of a COVID-19 patient registry especially in a regional setting requires identification of stakeholders in the province and then forming a steering committee. The steering committee consists of experts with different areas of specialization which may include radiology, epidemiology, computer science, lung diseases, infectious diseases, emergency medicine, and health informatics management (

Figure 7) [

5]. The main task of this committee is to formulate the purposes of establishing a registry, develop actions and protocol for program implementation, evaluate program implementation, as well as seek support. Subcommittees are also established to ensure that activities of the program are carried out. Such subcommittees may include the hospital executive committee, imaging data management subcommittee, data quality and analysis subcommittee, as well as an imaging data management subcommittee [

5].

It is without a doubt that beyond the expertise and infrastructure, partnership with stakeholders plays a critical role in the establishment of a robust COVID-19 patient registry system. In particular, the regional setting such as the Western Visayas would require partnership with the regional Department of Health (DOH) who would mandate the regional hospitals to adopt the abovementioned strategies for the implementation of a COVID-19 patient registry in the region [

105]. The DOH is the principal health agency in the country that is responsible for ensuring basic public health services to the Filipino people by providing quality health care and regulating providers of health services and goods [

106]. Further, it may also be wise to consider a collaboration with the Western Visayas Health Research and Development Consortium, a structure created by the Department of Science and Technology - Philippine Council for Health Research and Development which together with the DOH can bring together various hospitals and academic institutions to encourage partnerships and resource sharing among partner institutions [

107].

The establishment of this type of registry system in the regional setting, if successful can be expanded to a national level which will have a myriad of benefits. Similar to other successful wider scale patient registry systems, such benefits include increased data interoperability, shortened response times to generate real-world evidence, improved utilization of limited resources, as well as improved ability to rapidly collate meaningful data [

108].

The establishment of this type of registry system in the regional setting, if successful can be expanded to a national level which will have a myriad of benefits. Similar to other successful wider scale patient registry systems, such benefits include increased data interoperability, shortened response times to generate real-world evidence, improved utilization of limited resources, as well as improved ability to rapidly collate meaningful data [

108].

5. Conclusions

The establishment of a COVID-19 patient registry in a regional setting of a developing country such as the Philippines will take a lot of effort. Indeed, a wide array of resources including financial, manpower, and infrastructure to name a few are needed for this to come to fruition. It is also essential that research teams such as the USA-CFI engage with various stakeholders including domain experts to ensure that the process of data collection, curation, management, analyses, and confidentiality are understood very clearly. These are critical steps to answering important research questions that are clinically relevant and feasible to address using the data collected.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.D and R.d.C.; methodology, G.G.D, O.B.G., H.C.E.R., P.R.F.Z.-R., J.A.R., and R.d.C.; investigation, G.G.D, H.C.E.R., P.R.F.Z.-R., J.A.R., and R.d.C; resources, G.G.D. and R.d.C.; data curation, G.G.D., P.R.F.Z.-R., J.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.D, H.C.E.R., P.R.F.Z.-R., J.A.R., and R.d.C; writing—review and editing, G.G.D, H.C.E.R., P.R.F.Z.-R., J.A.R., and R.d.C; visualization, G.G.D., O.B.G., and J.A.R..; supervision, G.G.D. and R.d.C.; project administration, G.G.D. and R.d.C..; funding acquisition, G.G.D. and R.d.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Philippines Department of Science and Technology (DOST) Balik Scientist Program through the Philippine Council for Health Research and Development (PCHRD) awarded to Dr. Gerard G. Dumancas for the Summer 2023.

Acknowledgments

The authors Dr. Romulo de Castro and Dr. Gerard G. Dumancas wish to thank the Balik Scientist Program of the DOST, Philippines through the PCHRD for the opportunity to serve the Filipino community through science, technology, and innovation. The Balik (Filipino word for Returning) Scientist Program (BSP) seeks highly trained Filipino scientists, technologists, experts, and professionals residing abroad to return to the Philippines and transfer their expertise to the local community for the acceleration of scientific, agro-industrial and economic development of the country. Dr. Dumancas would like to thank the University of San Agustin Center for Informatics for hosting Dr. Dumancas for his short term Balik Scientist stint (Summer 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Philippine Council for Health Research and Development. 2023 Call for Proposals - DOST/PCHRD Funding.

- Morens, D.M.; Fauci, A.S. Emerging Pandemic Diseases: How We Got to COVID-19. Cell 2020, 182, 1077–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abebe, G.M. Emerging and re-emerging viral diseases: The case of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19. Int J Virol AIDS 2020, 7, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Zarei, J.; Badavi, M.; Karandish, M. A study to design minimum data set of COVID-19 registry system. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, J.; Dastoorpoor, M.; Jamshidnezhad, A. Regional COVID-19 Registry in Khuzestan, Iran: A Study Protocol and Lessons Learned from a Pilot Implementation. Inf. Med Unlocked 2021, 23, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What You Need to Know about the Coronavirus Right Now. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/what-you-need-know-about-coronavirus-right-now-2022-03-18/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Ahmed, K.; Bukhari, M.A.; Mlanda, T. Novel Approach to Support Rapid Data Collection, Management, and Visuali-Zation During the COVID-19 Outbreak Response in the World Health Organization African Region: Development of a Data Summarization and Visualization Tool. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020, 6, 20355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi-Arpanahi, H.; Moulaei, K.; Shanbehzadeh, M. Design and development of a web-based registry for Coronavirus (COVID-19) disease. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2020, 34, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellgard, M.I.; Render, L.; Radochonski, M. Second Generation Registry Framework. Source Code Biol Med 2014, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, V.; Schlemmer, M.; Rossov, S. Establishing Patient Registries for Rare Diseases: Rationale and Challenges. Pharm. Med 2020, 34, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Loeb, D.F.; Sprowell, A.J. Design and Implementation of a Depression Registry for Primary Care. Am J Med Qual 2019, 34, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurvitz, E.A.; Gross, P.H.; Gannotti, M.E. Registry-Based Research in Cerebral Palsy: The Cerebral Palsy Research Network; Volume 31, pp. 185–194.

- Rodriguez, S.; Guzmán, T.M.; Tafurt, E. Hospital-Based COVID-19 Registry: Design and Implementation. Colomb. Exp. MethodsX 2023, 10, 102056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haw, J. Thinking Machines Data Science. Inf. Epidemiol. Health Syst. Capacity.

- Johns Hopkins University Philippines - COVID-19 Overview - Johns Hopkins Available online:. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/region/philippines (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Tee, M.L.; Tee, C.A.; Anlacan, J.P. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic in the Philippines. J Affect Disord 2020, 277, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J.; Los Santos, J.A.A. Fear of COVID-19, Psychological Distress, Work Satisfaction and Turnover Intention among Frontline Nurses. J Nurs Manag 2021, 29, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, L.L.; Hung, N.; Go, D.J. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of COVID-19 among Income-Poor Households in the Philippines: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Glob Health 10, 011007. [CrossRef]

- Buenaventura, R.D.; Ho, J.B.; Lapid, M.I. COVID-19 and Mental Health of Older Adults in the Philippines: A Perspective from a Developing Country. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Castillo, A.M.; Salonga, L.J. Factors Affecting Perceived Effectiveness of COVID-19 Prevention Measures among Filipinos during Enhanced Community Quarantine in Luzon, Philippines: Integrating Protection Motivation Theory and Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 99, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, A.B.I.; Mendoza, N.B. Measuring Hope during the COVID-19 Outbreak in the Philippines: Development and Val-Idation of the State Locus-of-Hope Scale Short Form in Filipino. Curr Psychol 2021, 40, 5698–5707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, E.; Shimizutani, S.; Yamada, E. Projection of the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Welfare of Remit-Tance-Dependent Households in the Philippines. EconDisCliCha 2021, 5, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salva, E.P.; Villarama, J.B.; Lopez, E.B. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Suspected COVID-19 Admitted in Metro Manila, Philippines. Trop. Med. Health 2020, 48, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Haw, N.J.L.; Uy, J.; Sy, K.T.L. Epidemiological Profile and Transmission Dynamics of COVID-19 in the Philippines. Epi-Demiology Infect. 2020, 148, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrada, E.M.; Lopez, E.B.; Villarama, J.B. First COVID-19 Infections in the Philippines: A Case Report. Trop. Med. Health 2020, 48, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Co, C.O.C.; Yu, J.R.T.; Laxamana, L.C. Intravenous Thrombolysis for Stroke in a COVID-19 Positive Filipino Patient, a Case Report. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 77, 234–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.J.; Turalde, C.W.; Bagnas, M.A. Intravenous immunoglobulin in COVID-19 associated Guillain–Barré syndrome in pregnancy. BMJ Case Rep. CP 2021, 14, 242365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, A.M.U.; Jamora, R.D.G.; Jose, A.C.E. Cerebral Vasculitis in a COVID-19 Confirmed Postpartum Patient: A Case Report. Case Rep. Neurol. 2021, 13, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de, C.L.L.C.; JDB, D.; KHD, I. Concurrent Acute Ischemic Stroke and Non-Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in COVID-19. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 48, 587–588. [Google Scholar]

- Ubaldo, O.G.V.; Palo, J.E.M.; Cinco, J.E.L. COVID-19: A Single-Center ICU Experience of the First Wave in the Philippines. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, W.S.T. Repurposed Antiviral Drugs for Covid-19—Interim WHO Solidarity Trial Results. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomacruz, I.D.; So, P.N.; Pasilan, R.M. Clinical Characteristics and Short-Term Outcomes of Chronic Dialysis Patients Admitted for COVID-19 in Metro Manila, Philippines. Int. J. Nephrol. Renov. Dis. 2021, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abad, C.L.; Lansang, M.A.D.; Cordero, C.P. Early Experience with COVID-19 Patients in a Private Tertiary Hospital in the Philippines: Implications on Surge Capacity, Healthcare Systems Response, and Clinical Care. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 10, 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrupis, K.A.; Smith, C.; Suzuki, S. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of the First 500 Confirmed COVID-19 Inpatients in a Tertiary Infectious Disease Referral Hospital in Manila, Philippines. Trop. Med. Health 2021, 49, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarigumba, M.; Aragon, J.; Kanapi, M.P. Baseline Glycemic Status and Outcome of Persons with Type 2 Diabetes with COVID-19 Infections: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. J. ASEAN Fed. Endocr. Soc. 2021, 36, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espiritu, A.I.; Sy, M.C.C.; Anlacan, V.M.M. The Philippine COVID-19 Outcomes: A Retrospective Study Of Neurological Manifestations and Associated Symptoms (The Philippine CORONA Study): A Protocol Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, 040944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punzalan, F.E.R.; Aherrera, J.A.M.; de Paz-Silava, S.L.M.; Mondragon, A.V.; Malundo, A.F.G.; Tan, J.J.E.; Tantengco, O.A.G.; Quebral, E.P.B.; Uy, M.N.A.R.; Lintao, R.C.V.; et al. Utility of Laboratory and Immune Biomarkers in Predicting Disease Progression and Mortality among Patients with Moderate to Severe COVID-19 Disease at a Philippine Tertiary Hospital. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1123497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, N.D.; Strayer, R.J.; Levitan, R. Early Self-Proning in Awake, Non-Intubated Patients in the Emergency Department: A Single ED’s Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 27, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztajnbok, J.; Maselli-Schoueri, J.H.; Resende Brasil, L.M. Prone Positioning to Improve Oxygenation and Re-Lieve Respiratory Symptoms in Awake, Spontaneously Breathing Non-Intubated Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 30, 101096. [Google Scholar]

- University of San Agustin Center for Informatics. Covid-19 DOH Data. Available online: https://www.usacfi.net/covid-19-doh-data.html (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- COVID Kaya: A Digital Platform for COVID-19 Information Management in the Philippines. Available online: https://www.who.int/philippines/news/feature-stories/detail/covid-kaya-a-digital-platform-for-covid-19-information-management-in-the-philippines (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- COVID-19 Cases in the Philippines. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/cvronao/covid19-philippine-dataset (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Philippines : COVID-19 Response (Who Does What Where) - Humanitarian Data Exchange. Available online: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/philippines-covid-19-response-who-does-what-where? (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Journal 2022 Vol.23 No.2 Original Articles 1. Available online: https://www.pidsphil.org/home/journal-2022-vol-23-no-2-original-articles-1/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Journal 2022 Vol.23 No.2. Available online: https://www.pidsphil.org/home/2022-journals-v23-i2/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- ODPH - View Public Dataset. Available online: https://data.gov.ph/index/public/dataset/COVID-19%20DOH%20Data%20Drop%20%28December%2003,%202022%29/p3tcb60f-jube-wcfz-oafv-29n337hb2t1m (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Philippines: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- COVID-19 Dashboard. Available online: https://www.covid19.gov.ph/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Hu, T.; Guan, W.W.; Zhu, X.; Shao, Y.; Liu, L.; Du, J.; Liu, H.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; She, B.; et al. Building an Open Resources Repository for COVID-19 Research. Data Inf. Manag. 2020, 4, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, A.; Brooks, L.; Jahja, M.; Rumack, A.; Tang, J.; Agrawal, S.; Saeed, W.A.; Arnold, T.; Basu, A.; Bien, J.; et al. An Open Repository of Real-Time COVID-19 Indicators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118, e2111452118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Mulay, A.; Ferrara, E.; Zafarani, R. ReCOVery: A Multimodal Repository for COVID-19 News Credibility Research. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 3205–3212. [Google Scholar]

- Verdugo-Paiva, F.; Vergara, C.; Ávila, C.; Castro-Guevara, J.A.; Cid, J.; Contreras, V.; Jara, I.; Jiménez, V.; Lee, M.H.; Muñoz, M.; et al. COVID-19 Living Overview of Evidence Repository Is Highly Comprehensive and Can Be Used as a Single Source for COVID-19 Studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 149, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC COVID Data Tracker. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Clary, A.; Solis, P.; Mitchell, K. Optimizing Clinical Registries During the COVID-19 Era. Available online: https://avalere.com/insights/optimizing-clinical-registries-during-the-covid-19-era (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- DiPietro, L. Physicians Team Up to Fight COVID-19. Available online: https://stat.cornell.edu/news/cornell-statisticians-physicians-team-fight-covid-19 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Goyal, P.; Choi, J.J.; Pinheiro, L.C. Clinical Characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2372–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Volodarskiy, A.; Sultana, R. Prognostic Utility of Right Ventricular Remodeling Over Conventional Risk Stratification in Patients With COVID-19. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1965–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brar, G.; Pinheiro, L.C.; Shusterman, M. COVID-19 Severity and Outcomes in Patients With Cancer: A Matched Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 3914–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westblade, L.F.; Brar, G.; Pinheiro, L.C. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load Predicts Mortality in Patients with and without Cancer Who Are Hospitalized with COVID-19. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 661–6712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C). Available online: https://ncats.nih.gov/n3c (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Bennett, T.D.; Moffitt, R.A.; Hajagos, J.G.; Amor, B.; Anand, A.; Bissell, M.M.; Bradwell, K.R.; Bremer, C.; Byrd, J.B.; Denham, A.; et al. The National COVID Cohort Collaborative: Clinical Characterization and Early Severity Prediction. MedRxiv Prepr. Serv. Health Sci. 2021, arXiv:2021.01.12.21249511. [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Registries, Modeling, & Clinical Resources. Available online: https://ihpi.umich.edu/covid-19-registries-modeling-clinical-resources (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Kurth, F.; Roennefarth, M.; Thibeault, C. Studying the Pathophysiology of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Protocol for the Berlin Prospective COVID-19 Patient Cohort (Pa-COVID-19. Infection 2020, 48, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trama, A.; Proto, C.; Whisenant, J.G. Supporting Clinical Decision-Making during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic through a Global Research Commitment: The TERAVOLT Experience. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 602–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, B.L.H.; Chidambaram, S.K.; Wong, X.C. Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors for Severe COVID-19 Infections in Malaysia: A Nationwide Observational Study. Lancet Reg. Health 2020, 4, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surendra, H.; Elyazar, I.R.; Djaafara, B.A. Clinical Characteristics and Mortality Associated with COVID-19 in Jakarta, Indonesia: A Hospital-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Lancet Reg. Health 2021, 9, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Women’s, K.K.; Hospital, C. Pediatric Acute and Critical Care COVID-19 Registry of Asia. Clinical Trial Registration NCT04395781. Clinicaltrials.Gov 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Diogo, D.; Tian, C.; Franklin, C.S. Phenome-Wide Association Studies across Large Population Cohorts Support Drug Target Validation. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastarache, L.; Denny, J.C.; Roden, D.M. Phenome-Wide Association Studies. JAMA 2022, 327, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumancas, G.G.; Harrison, D.; Rico, J.A.; Zamora, P.R.F.C.; Liwag, A.G.; Villaruz, J.F.; Guanzon, M.L.V.V.; Ferraris, H.F.D.; Jalandoni, P.J.B.; Padernal, W.F.; et al. Are Phenome-Wide Association Studies Feasible in a Developing Country? Trends Genet. 2022, 38, 885–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research Centers and Laboratories - University of San Agustin. Available online: https://usa.edu.ph/research-extension/research-center/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Philippine Genome Center-Visayas. Available online: https://pgc.upv.edu.ph/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- PH Genome Center Helps, W. Visayas in COVID Fight. Available online: https://www.panaynews.net/ph-genome-center-helps-w-visayas-in-covid-fight/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- USA Launches U-Contact Trace - University of San Agustin. Available online: https://usa.edu.ph/usa-launches-u-contact-trace/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Filipino Scientists Back from Abroad to Help PH Fight the Pandemic. Available online: https://mb.com.ph/2020/05/13/filipino-scientists-back-from-abroad-to-help-ph-fight-the-pandemic/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Iloilo Re-Enforces Safety Measures against COVID-19. Available online: https://www.panaynews.net/iloilo-re-enforces-safety-measures-against-covid-19/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Arienti, C.; Campagnini, S.; Brambilla, L.; Fanciullacci, C.; Lazzarini, S.G.; Mannini, A.; Patrini, M.; Carrozza, M.C. The Methodology of a “Living” COVID-19 Registry Development in a Clinical Context. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 142, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müftüoğlu, Z.; Kızrak, M.A.; Yıldırım, T. 4 - Data Sharing and Privacy Issues Arising with COVID-19 Data and Applications. In Data Science for COVID-19; Kose, U., Gupta, D., de Albuquerque, V.H.C., Khanna, A., Eds.; Academic Press, 2022; pp. 61–75. ISBN 978-0-323-90769-9. [Google Scholar]

- Peeler, A.; Miller, H.; Ogungbe, O.; Lewis Land, C.; Martinez, L.; Guerrero Vazquez, M.; Carey, S.; Murli, S.; Singleton, M.; Lacanienta, C.; et al. Centralized Registry for COVID-19 Research Recruitment: Design, Development, Implementation, and Preliminary Results. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 5, e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J. What Is the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) Data Enclave? Available online: https://healthtechmagazine.net/article/2022/09/what-is-nc3-perfcon (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Developing a Registry of Patient Registries: Options for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality | Effective Health Care (EHC) Program. Available online: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/registry-of-patient-registries-development/research (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Mirasol, P.B. Balik Scientist Program: Enticing Filipino Scientists to Come Home. Available online: https://www.bworldonline.com/labor-and-management/2020/07/02/302923/balik-scientist-program-enticing-filipino-scientists-to-come-home/ (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Salvana, E. How Sustainable Is Research and Science in the Philippines? Available online: https://mb.com.ph/2023/2/3/how-sustainable-is-research-and-science-in-the-philippines (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Vigorously Advancing Science, Technology, and Innovation. Available online: https://pdp.neda.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Chapter-14.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Rivera, A.S.; Hernandez, R.; Mag-usara, R.; Sy, K.N.; Ulitin, A.R.; O’Dwyer, L.C.; McHugh, M.C.; Jordan, N.; Hirschhorn, L.R. Implementation Outcomes of HIV Self-Testing in Low- and Middle- Income Countries: A Scoping Review. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, A.; Custodio, R.; Lapitan, M.C.; Ladia, M.A. End Users’ Perspectives on the Quality and Design of mHealth Technologies During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Philippines: Qualitative Study. JMIR Form Res 2023, 7, e41838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, W.; Brubacher, L.J.; Kipp, A.; Wyngaarden, S.; Haldane, V.; Ferrolino, H.; Wilson, K.; Servano, D.; Lau, L.L.; Wei, X. Navigating Fear and Care: The Lived Experiences of Community-Based Health Actors in the Philippines during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 308, 115222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UP COVID-19 Pandemic Response Team Prevailing Data Issues in the Time of COVID-19 and the Need for Open Data. Available online: https://up.edu.ph/prevailing-data-issues-in-the-time-of-covid-19-and-the-need-for-open-data/ (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Rodriguez, S.; Guzmán, T.M.; Tafurt, E.; Beltrán, E.; Castro, A.; Rosso, F.; Prada, S.I.; Zarama, V. Hospital-Based COVID-19 Registry: Design and Implementation. Colombian Experience. MethodsX 2023, 10, 102056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 Registry. Available online: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/data-and-registries/covid19-registry/ (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Gallo Marin, B.; Aghagoli, G.; Lavine, K.; Yang, L.; Siff, E.J.; Chiang, S.S.; Salazar-Mather, T.P.; Dumenco, L.; Savaria, M.C.; Aung, S.N.; et al. Predictors of COVID-19 Severity: A Literature Review. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021, 31, e2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljohani, F.D.; Khattab, A.; Elbadawy, H.M.; Alhaddad, A.; Alahmadey, Z.; Alahmadi, Y.; Eltahir, H.M.; Matar, H.M.H.; Wanas, H. Prognostic Factors for Predicting Severity and Mortality in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillon, A.; Zhao, K.; Klein, K.O.; Greenwood, C.M.T.; Lu, Z.; Paradis, P.; Schiffrin, E.L. High Systolic Blood Pressure at Hospital Admission Is an Important Risk Factor in Models Predicting Outcome of COVID-19 Patients. Am. J. Hypertens. 2021, 34, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Shi, L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H. Is Creatinine an Independent Risk Factor for Predicting Adverse Outcomes in COVID-19 Patients? Transpl. Infect. Dis. Off. J. Transplant. Soc. 2021, 23, e13539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estiri, H.; Strasser, Z.H.; Klann, J.G.; Naseri, P.; Wagholikar, K.B.; Murphy, S.N. Predicting COVID-19 Mortality with Electronic Medical Records. Npj Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Duan, G.; Yang, H. Dyspnea Rather than Fever Is a Risk Factor for Predicting Mortality in Patients with COVID-19. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 647–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadehsani, R.; Alizadeh Sani, Z.; Behjati, M.; Roshanzamir, Z.; Hussain, S.; Abedini, N.; Hasanzadeh, F.; Khosravi, A.; Shoeibi, A.; Roshanzamir, M.; et al. Risk Factors Prediction, Clinical Outcomes, and Mortality in COVID-19 Patients. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 2307–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.; Figueiredo Filho, D. Using Benford’s Law to Assess the Quality of COVID-19 Register Data in Brazil. J. Public Health 2021, 43, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasudevan, V.; Gnanasekaran, A.; Sankar, V.; Vasudevan, S.A.; Zou, J. Variation in COVID-19 Data Reporting Across India: 6 Months into the Pandemic. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2020, 100, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon de Lusignan; John Williams To Monitor the COVID-19 Pandemic We Need Better Quality Primary Care Data. BJGP Open 2020, 4, bjgpopen20X101070. [CrossRef]

- Macabasag, R.L.A.; Mallari, E.U.; Pascual, P.J.C.; Fernandez-Marcelo, P.G.H. Normalisation of Electronic Medical Records in Routine Healthcare Work amidst Ongoing Digitalisation of the Philippine Health System. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 307, 115182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, N.; Perego, A. Interoperability of Population-Based Patient Registries. J. Biomed. Inform. X 2020, 6, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology Connecting Health and Care for the Nation, 2015.

- Gao, J.; Yang, C.; Heintz, J.; Barrows, S.; Albers, E.; Stapel, M.; Warfield, S.; Cross, A.; Sun, J. MedML: Fusing Medical Knowledge and Machine Learning Models for Early Pediatric COVID-19 Hospitalization and Severity Prediction. iScience 2022, 25, 104970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health (DOH) Region VI Department of Health - Regional Office VI. Available online: https://ro6.doh.gov.ph/ (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Derpartment of Health (DOH) Philippines About Us | Department of Health Website. Available online: https://doh.gov.ph/about-us (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- Iloilo Today, I. All Set for Health Conference in WV. Iloilo Today 2018.

- Wall, D.; Alhusayen, R.; Arents, B.; Apfelbacher, C.; Balogh, E.A.; Bokhari, L.; Bloem, M.; Bosma, A.L.; Burton, T.; Castelo-Soccio, L.; et al. Learning from Disease Registries during a Pandemic: Moving toward an International Federation of Patient Registries. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 39, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).