Submitted:

27 August 2024

Posted:

28 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

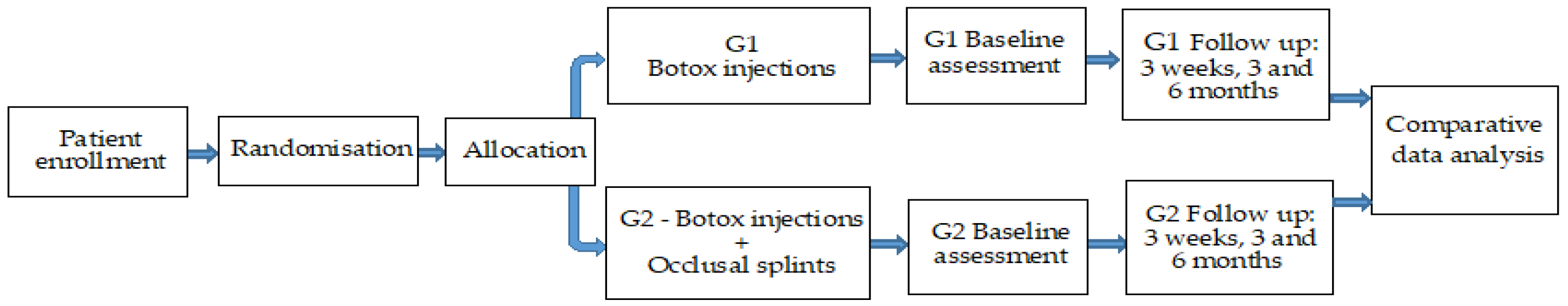

2. Materials and Methods

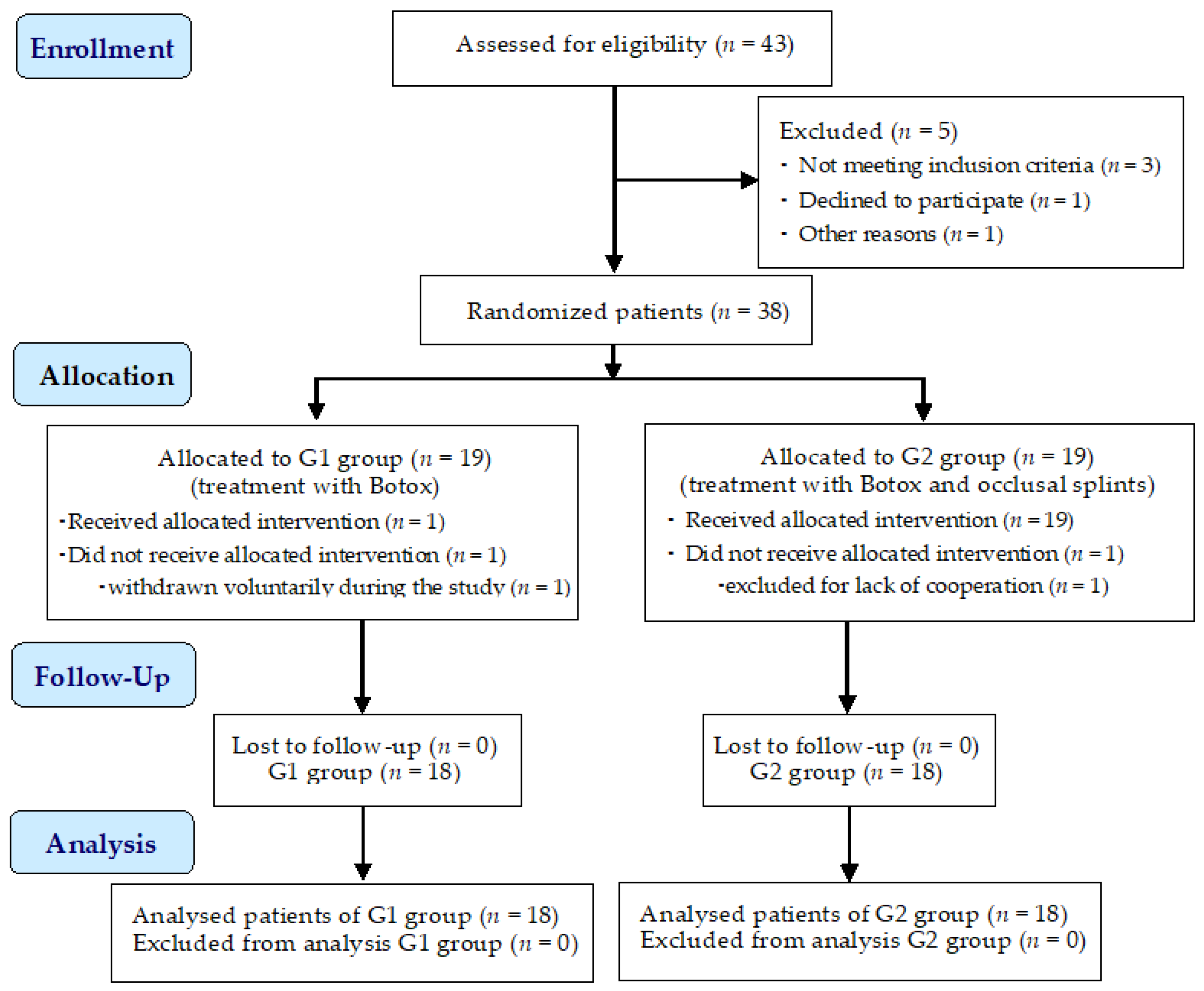

2.1. Selection of Patients

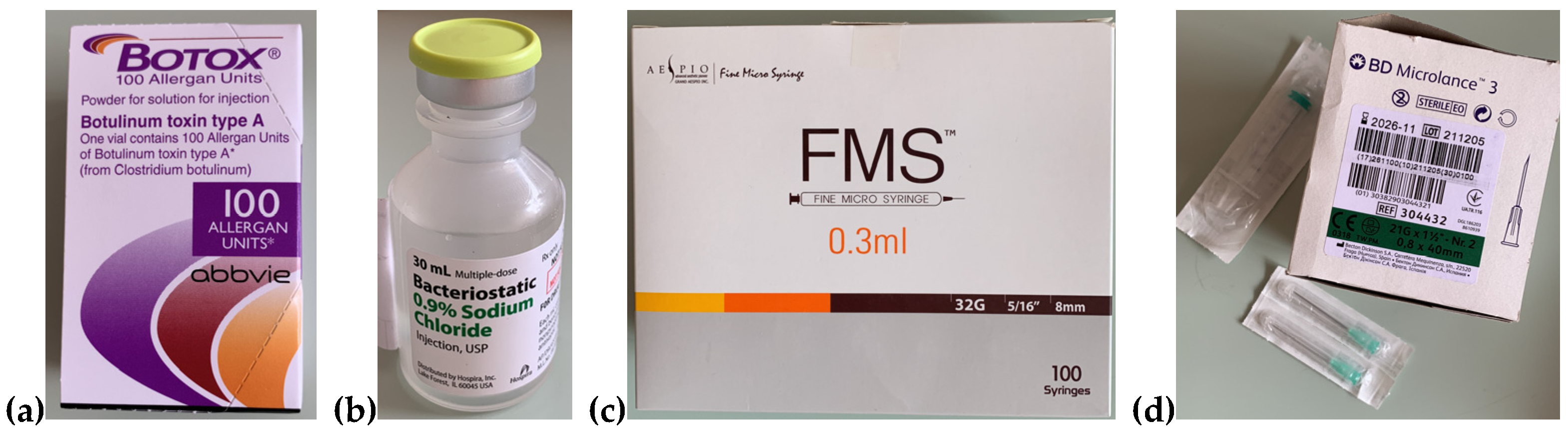

2.2. Performing Botox-Allergan Injections

2.3. Manufacturing the Thermoformed Occlusal Splints

2.4. Questionnaires Regarding the Symptomatology and the Satisfaction of Patients

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cumpston, E., Chen, P. Sleep Apnea Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Sep 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564431/ (accessed on February 2024).

- Slowik, J.M., Sankari, A., Collen, J.F. Obstructive Sleep Apnea. [Updated 2024 Mar 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459252/ (accessed on February 2024).

- Lechner, M., Breeze, C.E., Ohayon, M.M., Kotecha, B. Snoring and breathing pauses during sleep: interview survey of a United Kingdom population sample reveals a significant increase in the rates of sleep apnoea and obesity over the last 20 years—data from the UK sleep survey. Sleep Med. 2019, 54, 250-256. [CrossRef]

- Borsini, E., Noguiera, F., Nigro, C. Apnea-hypopnea index in sleep studies and the risk of over-simplification. Sleep Science, 2018, 11, 1, 45–48. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A., Gupta, S.S., Sabharwal, N., Meghrajani, V., Sharma, S., Kamholz, S., Kupfer, Y. A comprehensive review of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Sci. 2021, 14, 2, 142-154. [CrossRef]

- Leigh, C., Faigenblum, M., Fine, P., Blizard, R., Leung, A. General dental practitioners’ knowledge and opinions of snoring and sleep-related breathing disorders. Br Dent J. 2021, 1, 9, 569-574. [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, M.P., Nemomssa, H.D., Simegn, G.L. Sleep apnea syndrome detection and classification of severity level from ECG and SpO2 signals. Health Technol 2021, 5, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kazubowska-Machnowska, K., Jodkowskam, A., Michalek-Zrabkowska, M., Wieckiewicz, M., Poreba, R., Dominiak, M., Gac, P., Mazur, G., Kanclerska, J., Martynowicz, H. The Effect of Severity of Obstructive Sleep Apnea on Sleep Bruxism in Respiratory Polygraphy Study. Brain Sci. 2022,12, 7, 828. [CrossRef]

- Lv, R., Liu, X., Zhang, Y. et al. Pathophysiological mechanisms and therapeutic approaches in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 218. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.sleepfoundation.org/bruxism.

- Craciun, A.E., Cerghizan, D., Popsor, S., Bica, C. Bruxism in Children and Adolescents and its Association with Some Possible Aetiological Factors. Curr Health Sci J. 2023, 49, 2, 257-262. [CrossRef]

- Golanska, P.; Saczuk, K.; Domarecka, M.; Kuć, J.; Lukomska-Szymanska, M. Temporomandibular Myofascial Pain Syndrome—Aetiology and Biopsychosocial Modulation. A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 15, 7807. [CrossRef]

- Osses-Anguita, Á.E.; Sánchez-Sánchez, T.; Soto-Goñi, X.A.; García-González, M.; Alén Fariñas, F.; Cid-Verdejo, R.; Sánchez Romero, E.A.; Jiménez-Ortega, L. Awake and Sleep Bruxism Prevalence and Their Associated Psychological Factors in First-Year University Students: A Pre-Mid-Post COVID-19 Pandemic Comparison. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3, 2452. [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, G.; Pająk, A.; Wójcicki, M. Global Prevalence of Sleep Bruxism and Awake Bruxism in Pediatric and Adult Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 14, 4259. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, R., Paesani, D., Koyano, K., Tsukiyama, Y., Carra, M.C., Lavigne, G.J. Sleep Bruxism. In: Farah, C., Balasubramaniam, R., McCullough, M. Contemporary Oral Medicine. 2019, Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.bruxism.org.uk/what-is-bruxism.php.

- Ohlmann, B., Waldecker, M., Leckelm M., Bömicke, W., Behnisch, R., Rammelsberg, P., Schmitter, M., Correlations between Sleep Bruxism and Temporomandibular Disorders. J Clin Med. 2020, 9, 2, 611. [CrossRef]

- Iacob, S.M., Chisnoiu, A.M., Objelean, A., Fluerașu, M.I., Moga, R.R., Buduru, S.D. Correlation between bruxism, occlusal dysfunction and musculo-articular status, Romanian Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 2022, 14, 3, 48-55.

- Wetselaar, P., Vermaire, E.J.H., Lobbezoo, F., Schuller, A.A. The prevalence of awake bruxism and sleep bruxism in the Dutch adult population. J Oral Rehabil. 2019, 46, 7, 617-623. [CrossRef]

- Thayer, M.L.T., Ali, R. The dental demolition derby: bruxism and its impact—part 1: background. Br Dent J. 2022; 232, 8, 515-521. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.C., Patel, J., Kumar, S.S., Dakshinamoorthy, J., Greenstein, Y.,Kamalam Ravindran, H., Kodaganallur Pitchumani, P. Sleep related bruxism—comprehensive review of the literature based on a rare case presentation, Frontiers of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, 2024, 6, 3, 1-14. Available online: https://fomm.amegroups.org/article/view/67995.

- Available online: https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-apnea/link-between-sleep-apnea-and-teeth-grinding.

- Özsoy, H.E., Gaş, S., Aydın, K.C. The Relationship between Stress Levels, Sleep Quality, and Oral Health-related Quality of Life in Turkish University Students with Self-reported Bruxism. J Turk Sleep Med. 2022, 9, 1, 64-72. [CrossRef]

- Colonna, A., Manfredini, D. Bruxism: An orthodontist’s perspective, Seminars in Orthodontics, 2024, 30, 3, 318-324. [CrossRef]

- Mercan Başpınar, M., Mercan, Ç., Mercan, M., Arslan Aras, M. Comparison of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life, Sleep Quality, and Oral Health Literacy in Sleep and Awake Bruxism: Results from Family Medicine Practice. Int J Clin Pract. 2023, 30, 2023, 1186278. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00083.

- Rasetti-Escargueil, C.; Palea, S. Embracing the Versatility of Botulinum Neurotoxins in Conventional and New Therapeutic Applications. Toxins 2024, 16, 261. [CrossRef]

- Park, M.Y., Ahn, K.Y. Scientific review of the aesthetic uses of botulinum toxin type A. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2021, 22, 1, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Brin, M.F., Burstein, R. Botox (onabotulinumtoxinA) mechanism of action. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023, 102, S1, e32372. [CrossRef]

- Bechir, E.S., Bechir, A., Arghir, O.A., Ciavoi, G., Gioga, C., Curt Mola, F., Dascalu, I.T. Results in the Use of Two Types of Polymeric Appliances in the Therapy of Some Mild Sleep Apnea Simptoms, Rev. Mat. Plastice Bucuresti, 2017, 54, 2, 304-308. Available online: http://www.revmaterialeplastice.ro/archive.asp.

- Costăchel, B.C.; Bechir, A.; Burcea, A.; Mihai, L.L.; Ionescu, T.; Marcu, O.A.; Bechir, E.S. Evaluation of Abfraction Lesions Restored with Three Dental Materials: A Comparative Study. Clin. Pract. 2023, 13, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.verywellhealth.com/declaration-of-helsinki-4846525.

- Available online: https://ndsonline.co.uk/products/proform-3mm-dual-laminate-blanks-erkodent.

- González, A., Montero, J., Gómez Polo, C. Sleep Apnea-Hypopnea Syndrome and Sleep Bruxism: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2023, 23, 12, 3, 910. [CrossRef]

- Merrill, R.M., Ashton, M.K., Angell, E. Sleep disorders related to index and comorbid mental disorders and psychotropic drugs. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2023, 22, 1, 23. [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Chavarría, A.R., Utsman-Abarca, R., Herrero-Babiloni, A.. Bruxism an issue between the myths and fact. Odovtos International Journal of Dental Sciences, 2022, 24, 3, 15-21. [CrossRef]

- Vlăduțu, D.E.; Ionescu, M.; Mercuț, R.; Noveri, L.; Lăzărescu, G.; Popescu, S.M.; Scrieciu, M.; Manolea, H.O.; Iacov Crăițoiu, M.M.; Ionescu, A.G.; Mercuț, V. Ecological Momentary Assessment of Masseter Muscle Activity in Patients with Bruxism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1, 581. [CrossRef]

- Lobbezoo F, Ahlberg J, Raphael KG, Wetselaar P, Glaros AG, Kato T, Santiago V, Winocur E, De Laat A, De Leeuw R, Koyano K, Lavigne GJ, Svensson P, Manfredini D. International consensus on the assessment of bruxism: Report of a work in progress. J Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 11, 837-844. [CrossRef]

- Shivamurthy, P.G., Kumari, N., Sadaf, A., Meghana, M.B., Azhar, H., Sabrish, S. Use of Fonseca’s Questionnaire to assess the prevalence and severity of Temporomandibular disorders among university students—a cross sectional study. Dentistry 3000. 2022, 10, 1, a001. [CrossRef]

- Witmanowski, H., Błochowiak, K. The whole truth about botulinum toxin—a review. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2020, 37, 6, 853-861. [CrossRef]

- Dickison, C., Leggit, J.C. Botulinum toxin for chronic pain: What’s on the horizon? J Fam Pract. 2021, 70, 9, 442-449. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, R.H., Koshy, R.R., Fathima, Y., Weerasekara, R.A., Sherin, Z., Selvakumar, N., Korrapati, N.H. The clinical approach to botulinum toxin in dermatology: A literature review. CosmoDerma 2023, 3, 58, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Malcangi, G.; Patano, A.; Pezzolla, C.; Riccaldo, L.; Mancini, A.; Di Pede, C.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Inchingolo, F.; Bordea, I.R.; Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.M.. Bruxism and Botulinum Injection: Challenges and Insights. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4586. [CrossRef]

- Ângelo, D.F.; Sanz, D.; Maffia, F.; Cardoso, H.J. Outcomes of IncobotulinumtoxinA Injection on Myalgia and Arthralgia in Patients Undergoing Temporomandibular Joint Arthroscopy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Toxins 2023, 15, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K., Tan, K., Yacovelli, A., Bi, W.G. Effect of botulinum toxin type A on muscular temporomandibular disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Oral Rehabil.2024, 51, 886-897. [CrossRef]

- Mierzwa, D., Olchowy, C., Olchowy, A., Nawrot-Hadzik, I., Dąbrowski, P., Chobotow, S., Grzech-Leśniak, K., Kubasiewicz-Ross, P., Dominiak, M. Botox Therapy for Hypertrophy of the Masseter Muscle Causes a Compensatory Increase of Stiffness of Other Muscles of Masticatory Apparatus. Life (Basel). 2022 12, 6, 840. [CrossRef]

- Yağci, İ., Taşdelen, Y., Kivrak, Y. Childhood Trauma, Quality of Life, Sleep Quality, Anxiety and Depression Levels in People with Bruxism. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2020, 57, 2, 131-135. [CrossRef]

- Chirico, F.; Bove, P.; Fragola, R.; Cosenza, A.; De Falco, N.; Lo Giudice, G.; Audino, G.; Rauso, G.M. Biphasic Injection for Masseter Muscle Reduction with Botulinum Toxin. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6478. [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, N.M., Goldman, E.M. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Masseter Muscle. [Updated 2023 Jun 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539869/.

- Rathod, N.N., John, R.S. Botulinum Toxin Injection for Masseteric Hypertrophy Using 6 Point Injection Technique—A Case Report. Proposal of a Clinical Technique to Quantify Prognosis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2023, 15, 45-49. [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Rueda, J.A., López-Valverde, A., Márquez-Vera, A., Méndez-Sánchez, R., López-García, E., López-Valverde, N. Preliminary Findings of the Efficacy of Botulinum Toxin in Temporomandibular Disorders: Uncontrolled Pilot Study. Life (Basel). 2023, 13, 2, 345. [CrossRef]

- Jagger, R., King, E. Occlusal Splints for Bruxing and TMD—A Balanced Approach?, Restorative Dentistry, Dent Update 2018, 45, 912–918. [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, A., Edelhoff, D., Schubert, O., Erdelt, K.J., Pho Duc, J.M. Effect of treatment with a full-occlusion biofeedback splint on sleep bruxism and TMD pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 11, 4005-4018. [CrossRef]

- Albagieh, H., Alomran, I., Binakresh, A., Alhatarisha, N., Almeteb, M., Khalaf, Y., Alqublan, A., Alqahatany, M. Occlusal splints-types and effectiveness in temporomandibular disorder management. Saudi Dent J. 2023, 35, 1, 70-79. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J., Pauletto, P., Massignan, C., Bolan, M., Domingos, F.L., Curi Hallal, A.L., De Luca Canto, G. Association between Sleep Bruxism and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. Journal of Oral & Facial Pain and Headache. 2020. 34, 4, 341-352. [CrossRef]

- Mercan Başpınar, M., Mercan, Ç., Mercan, M., Arslan Aras, M. Comparison of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life, Sleep Quality, and Oral Health Literacy in Sleep and Awake Bruxism: Results from Family Medicine Practice. Int J Clin Pract. 2023, 30, 2023, 1186278. [CrossRef]

- Lal, S.J., Sankari, A., Weber, K.K. Bruxism Management. [Updated 2024 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482466/.

- Ferrillo, M.; Ammendolia, A.; Paduano, S.; Calafiore, D.; Marotta, N.; Migliario, M.; Fortunato, L.; Giudice, A.; Michelotti, A.; de Sire, A. Efficacy of rehabilitation on reducing pain in muscle-related temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2022, 35, 921–936. [CrossRef]

| All patients | Group 1 (G1) | Group 2 (G2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No of patients | 36 | 18 | 18 |

| Age (mean ± years) | 31-50 year | Male Female |

33-50 (mean 41,5 ± 8.5) 31-48 (mean 39.5 ± 8.5) |

| Gender M/F | Male 12 (34%) | 6 (33.33%) | 6 (33.33%) |

| Female 24 (66%) | 12 (66.66%) | 12 (66.66%) |

| Objective symptom | Patients group | Baseline | Lastfollow-up session | |||

| Present | Absent | Present | Absent | |||

| 1. | Contraction of the temporal muscle bundles | G1 | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) |

| G2 | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) | ||

| 2. | Contraction of the masseter muscle bundles | G1 | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) |

| G2 | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) | ||

| 3. | Trismus | G1 | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) |

| G2 | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) | ||

| 4. | Tongue indentation | G1 | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) |

| G2 | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) | ||

| 5. | Buccal mucosa ridges | G1 | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) |

| G2 | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) | ||

| Questions addressed to patients (n = 36) | Responses | Questions addressed to patients’ bed partner’s (n = 36) | Responses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sleep disruption (episodes of stopping breathing) |

never | 3 (=8.33%) |

Sleep disruption (episodes of stopping breathing) |

never | 0 (=0%) |

| rarely | 11 (=30.55%) | rarely | 1 (=2.77%) | ||

| sometimes | 5 (=13.88%) | sometimes | 2 (=5.55%) | ||

| usually | 11 (=30.55%) | usually | 4 (=11.11%) | ||

| always | 6 (=16.66%) | always | 29 (=80.55%) | ||

| Nocturnal bruxism (teeth grinding or clenching) | never | 0 (=0%) | Nocturnal bruxism (teeth grinding or clenching) |

never | 1 (=2.77%) |

| rarely | 1 (=2.77%) | rarely | 3 (=8.33%) | ||

| sometimes | 6 (=16.66%) | sometimes | 6 (=16.66%) | ||

| usually | 9 (=25.0%) | usually | 12 (=33.33%) | ||

| always | 20 (=55.55%) | always | 14 (=38.88%) | ||

| Awakening in the morning with a dry mouth or sore throat | never | 0 (=0%) | Snoring | never | 0 (=0%) |

| rarely | 4 (=11.11%) | rarely | 2 (=5.55%) | ||

| sometimes | 7 (=19.44%) | sometimes | 13 (=36.11%) | ||

| usually | 12 (=33.33%) | usually | 12 (=33.33%) | ||

| always | 13 (=36.11%) | always | 9 (=25.0%) | ||

| Morning pain in the masseter muscle | never | 0 (=0%) | Waking during the night and gasping or choking | never | 0 (=0%) |

| rarely | 3 (=8.33%) | rarely | 4 (=11.11%) | ||

| sometimes | 4 (=11.11%) | sometimes | 5 (=13.88%) | ||

| usually | 9 (=25.0%) | usually | 19 (=52.77%) | ||

| always | 20 (=55.55%) | always | 8 (=22.22%) | ||

| Morning fatigue, headaches, and jaw pain |

never | 0 (=0%) | Mood changes (e.g., depressive or irritable) |

never | 3 (=8.33%) |

| rarely | 5 (=13.88%) | rarely | 9 (=25.0%) | ||

| sometimes | 8 (=22.22%) | sometimes | 8 (=22.22%) | ||

| usually | 12 (=33.33%) | usually | 9 (=25.0%) | ||

| always | 11 (=30.55%) | always | 7 (=19.44%) | ||

| Diurnal (daytime) difficulty in focusing |

never | 0 (=0%) | Diurnal (daytime) difficulty in focusing |

never | 1 (=2.77%) |

| rarely | 1 (=2.77%) | rarely | 3 (=8.33%) | ||

| sometimes | 12 (=33.33%) | sometimes | 5 (=13.88%) | ||

| usually | 12 (=33.33%) | usually | 16 (=44.44%) | ||

| always | 11 (=30.55%) | always | 12 (=33.33%) | ||

| Excessive daytime sleepiness | never | 1 (=2.77%) | Excessive daytime sleepiness | never | 6 (=16.66%) |

| rarely | 8 (=22.22%) | rarely | 6 (=16.66%) | ||

| sometimes | 9 (=25.0%) | sometimes | 7 (=19.44%) | ||

| usually | 7 (=19.44%) | usually | 8 (=22.22%) | ||

| always | 11 (=30.55%) | always | 9 (=25.0%) | ||

| Questions addressed to patients (n = 36) | Responses | Questions addressed to patients’ bed partner’s (n = 36) | Responses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sleep disruption (episodes of stopping breathing) |

never | 30 (=83.33%) |

Sleep disruption (episodes of stopping breathing) |

never | 26 (=72.22%) |

| rarely | 2 (=5.55%) | rarely | 6 (=16.66%) | ||

| sometimes | 3 (=8.33%) | sometimes | 4 (=11.11%) | ||

| usually | 1 (=2.77%) | usually | 0 (=0%) | ||

| always | 0 (=0%) | always | 0 (=0%) | ||

| Nocturnal bruxism (teeth grinding or clenching) | never | 31 (=86.11%) | Nocturnal bruxism (teeth grinding or clenching) |

never | 27 (=75%) |

| rarely | 3 (=8.33%) | rarely | 6 (=16.66%) | ||

| sometimes | 1 (=2.77%) | sometimes | 3 (=8.33%) | ||

| usually | 1 (=2.77%) | usually | 0 (=0%) | ||

| always | 0 (=0%) | always | 0 (=0%) | ||

| Awakening in the morning with a dry mouth or sore throat | never | 31 (=86.11%) | Snoring | never | 30 (=83.33%) |

| rarely | 4 (=11.11%) | rarely | 3 (=8.33%) | ||

| sometimes | 1 (=2.77%) | sometimes | 2 (=5.55%) | ||

| usually | 0 (=0%) | usually | 1 (=2.77%) | ||

| always | 0 (=0%) | always | 0 (=0%) | ||

| Morning pain in the masseter muscle | never | 32 (=88.88%) | Waking during the night and gasping or choking | never | 28 (=77.77%) |

| rarely | 2 (=5.55%) | rarely | 5 (=13.88%) | ||

| sometimes | 2 (=5.55%) | sometimes | 3 (=8.33%) | ||

| usually | 0 (=0%) | usually | 0 (=0%) | ||

| always | 0 (=0%) | always | 0 (=0%) | ||

| Morning fatigue, headaches, and jaw pain |

never | 29 (=80.55%) | Mood changes (e.g., depressive or irritable) |

never | 30 (=83.33%) |

| rarely | 4 (=11.11%) | rarely | 3 (=8.33%) | ||

| sometimes | 3 (=8.33%) | sometimes | 3 (=8.33%) | ||

| usually | 0 (=0%) | usually | 0 (=0%) | ||

| always | 0 (=0%) | always | 0 (=0%) | ||

| Diurnal (daytime) difficulty in focusing |

never | 26 (=72.22%) | Diurnal (daytime) difficulty in focusing |

never | 27 (=75%) |

| rarely | 7 (=19.44%) | rarely | 7 (=19.44%) | ||

| sometimes | 3 (=8.33%) | sometimes | 2 (=5.55%) | ||

| usually | 0 (=0%) | usually | 0 (=0%) | ||

| always | 0 (=0%) | always | 0 (=0%) | ||

| Excessive daytime sleepiness | never | 28 (=77.77%) | Excessive daytime sleepiness | never | 29 (=80.55%) |

| rarely | 4 (=11.11%) | rarely | 4 (=11.11%) | ||

| sometimes | 4 (=11.11%) | sometimes | 3 (=8.33%) | ||

| usually | 0 (=0%) | usually | 0 (=0%) | ||

| always | 0 (=0%) | always | 0 (=0%) | ||

| Group | Very dissatisfied |

Quite dis- satisfied |

Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | Quite satisfied |

Very satisfied |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | LFu | B | LFu | B | LFu | B | LFu | B | LFu | ||

| How satisfied are you with your sleep? | G1 | 12 66.66% |

0 0% |

2 11,11% |

0 0% |

2 11.11% |

0 0% |

1 5.55% |

2 11.11% |

1 5.55% |

16 88.88% |

| G2 | 11 61.11% | 0 0% |

3 16.66% |

0 0% |

2 11.11% |

0 0% |

1 5.55% |

1 5.55% |

1 5.55% |

17 94.44% |

|

| How satisfied are you about the contractions in masseter muscle? | G1 | 10 55.55% |

0 0% |

4 22.22% |

0 0% |

2 11.11% |

1 5.55% |

1 5.55% |

2 11.11% |

1 5.55% |

15 83.33% |

| G2 | 12 66.66% |

0 0% |

3 16.66% |

0 0% |

2 11.11% |

0 0% |

1 5.55% |

1 5.55% |

0 0% |

17 94.44% |

|

| How satisfied are you now about your ability to perform daily living activities? | G1 | 11 61.11% |

0 0% |

5 27.77% |

0 0% |

1 5.55% |

0 0% |

1 5.55% |

2 11.11% |

0 0% |

16 88.88% |

| G2 | 12 66.66% | 0 0% |

4 22.22% |

0 0% |

1 5.55% | 0 0% |

1 5.55% |

1 5.55% |

0 0% |

17 94.44% |

|

| How satisfied are you now with your capacity for work? | G1 | 10 55.55% |

0 0% |

5 27.77% |

0 0% |

2 11.11% |

0 0% |

1 5.55% |

2 11.11% |

0 0% |

16 88.88% |

| G2 | 10 55.55% |

0 0% |

4 22.22% |

0 0% |

2 11.11% |

0 0% |

2 11.11% |

1 5.55% |

0 0% |

17 94.44% |

|

| How satisfied are you now with your condition of concentration? |

G1 | 12 66.66% |

0 0% |

3 16.66% |

0 0% |

1 5.55% |

1 5.55% |

1 5.55% |

2 11.11% |

1 5.55% |

15 83.33% |

| G2 | 13 72.22% |

0 0% |

2 11.11% |

0 0% |

1 5.55% |

0 0% |

1 5.55% |

1 5.55% |

1 5.55% |

17 94.44% |

|

| How satisfied are you now with the applied therapy? | G1 | 0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

1 5.55% |

0 0% |

17 94.44% |

| G2 | 0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

0 0% |

18 100% |

|

| How was the nocturnal comfort with your occlusal splint? | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| G2 | 3 16.66% |

0 0% |

3 16.66% |

0 0% |

3 16.66% |

1 5.55% |

4 22.22% |

2 11.11% |

5 27.77% |

15 83.33% |

|

| How satisfied are you now with the health of your orofacial system? | G1 | 6 33.33% |

0 0% |

6 33.33% |

0 0% |

4 22.22% |

0 0% |

3 16.66% |

2 11.11% |

1 5.55% |

16 88.88% |

| G2 | 6 33.33% |

0 0% |

6 33.33% |

0 0% |

3 16.66% |

0 0% |

3 16.66% |

1 5.55% |

0 0% |

17 94.44% |

|

| How satisfied are you now with yourself? | G1 | 6 33.33% |

0 0% |

5 27.77% |

0 0% |

3 16.66% |

1 5.55% |

3 16.66% |

3 16.66% |

1 5.55% |

14 77.77% |

| G2 | 6 33.33% |

0 0% |

4 22.22% |

0 0% |

4 22.22% |

0 0% |

3 16.66% |

2 11.11% |

1 5.55% |

16 88.88% |

|

| How do you evaluate now your overall quality of life? | G1 | 3 16.66% |

0 0% |

5 27.77% |

0 0% |

4 22.22% |

0 0% |

3 16.66% |

2 11.11% |

3 16.66% |

16 88.88% |

| G2 | 4 22.22% |

0 0% |

3 16.66% |

0 0% |

4 22.22% |

0 0% |

4 22.22% |

1 5.55% |

3 16.66% |

17 94.44% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).