Submitted:

24 August 2024

Posted:

26 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Aim

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Patient Selection for the Institutional Case Series

- Confirmed diagnosis of localized prostate cancer suitable for radical prostatectomy in patients not suitable for or unwilling to undergo active surveillance;

- Incidental detection of a small renal tumor (≤4 cm) suitable for partial nephrectomy;

- Eligibility for minimally invasive robotic surgery based on overall health status and absence of contraindications;

- The absence of extensive adhesions in the peritoneal cavity after multiple abdominal surgeries and the absence of perirenal “toxic fat” significantly complicating surgical dissection.

3.2. Surgical Techniques

- RARP + RAPN

-

Robot-Assisted Partial Nephrectomy (RAPN):

- ◦

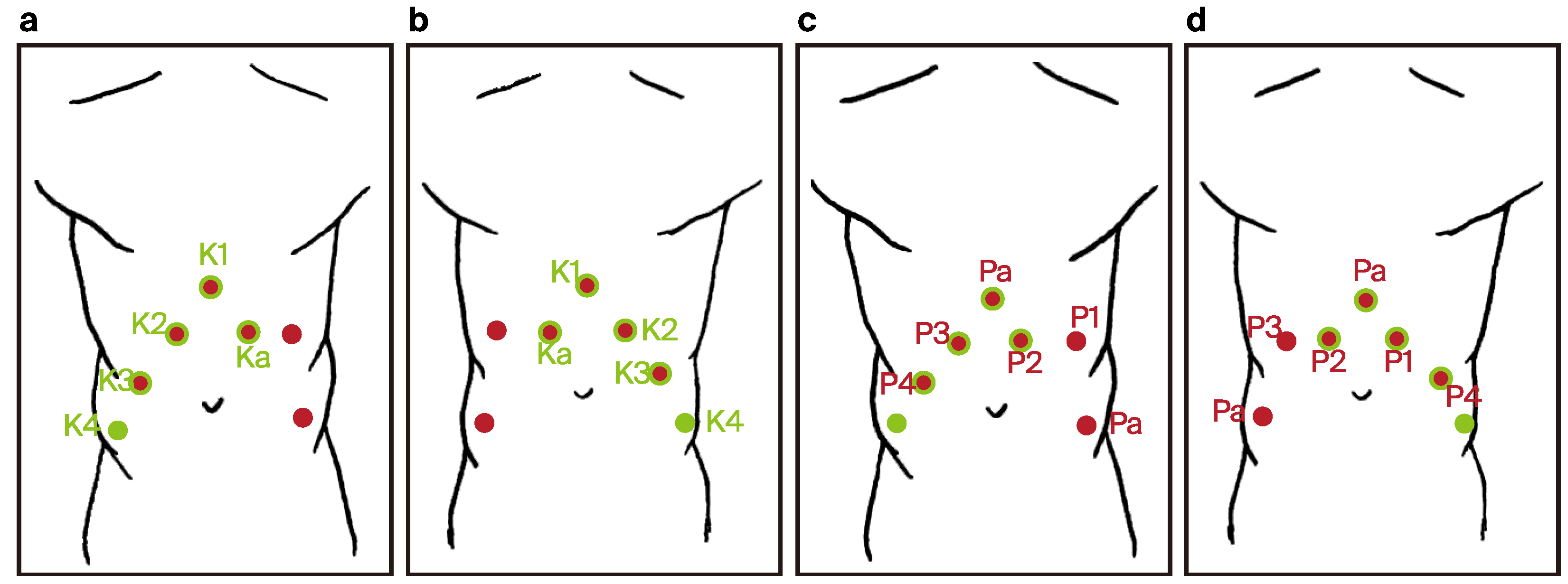

- The patient was initially placed in the lateral decubitus position (Figure 2).

- ◦

- One 12 mm laparoscopic trocar (assistant trocar) and four 8 mm robotic trocars were used (a total number of five).

- ◦

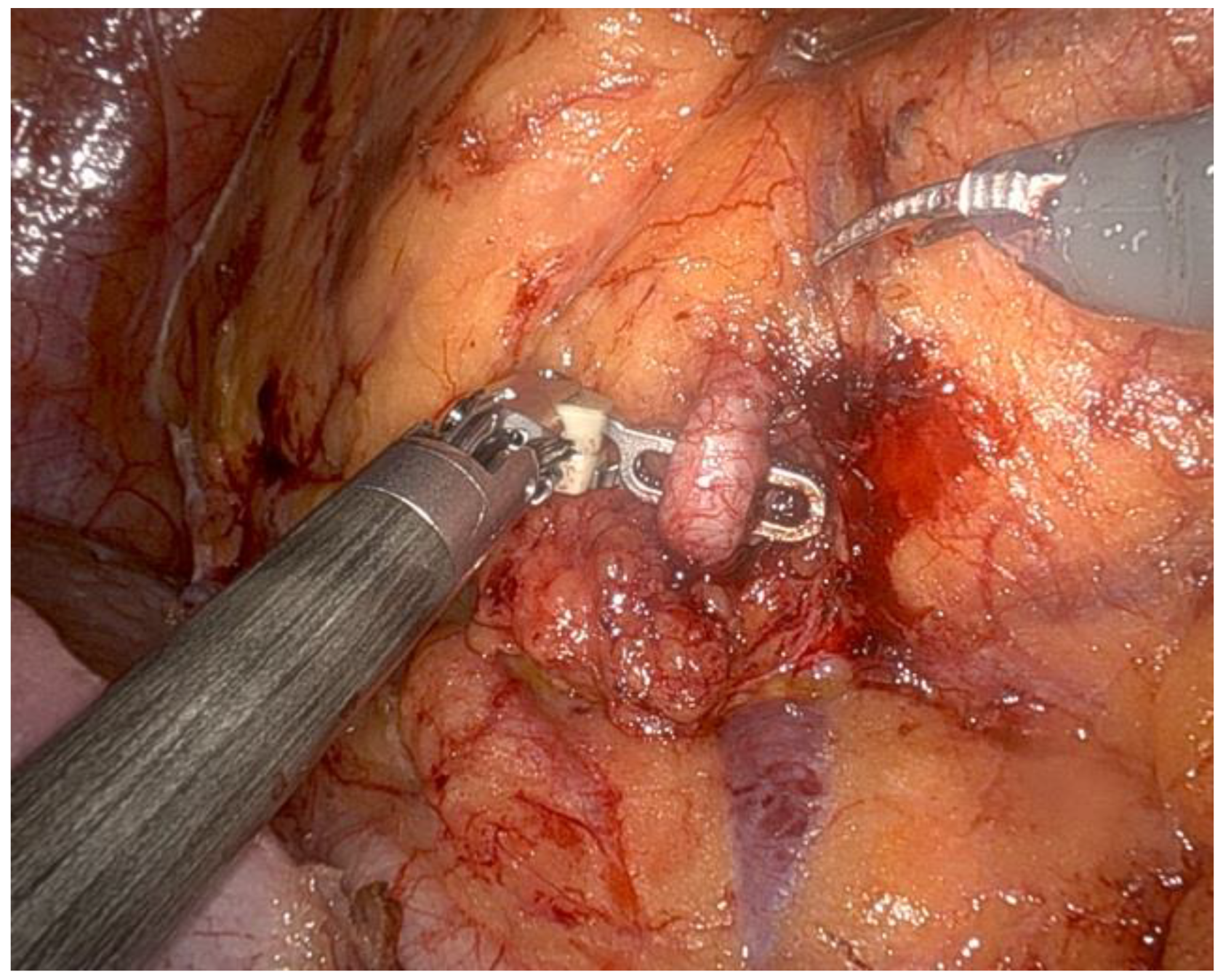

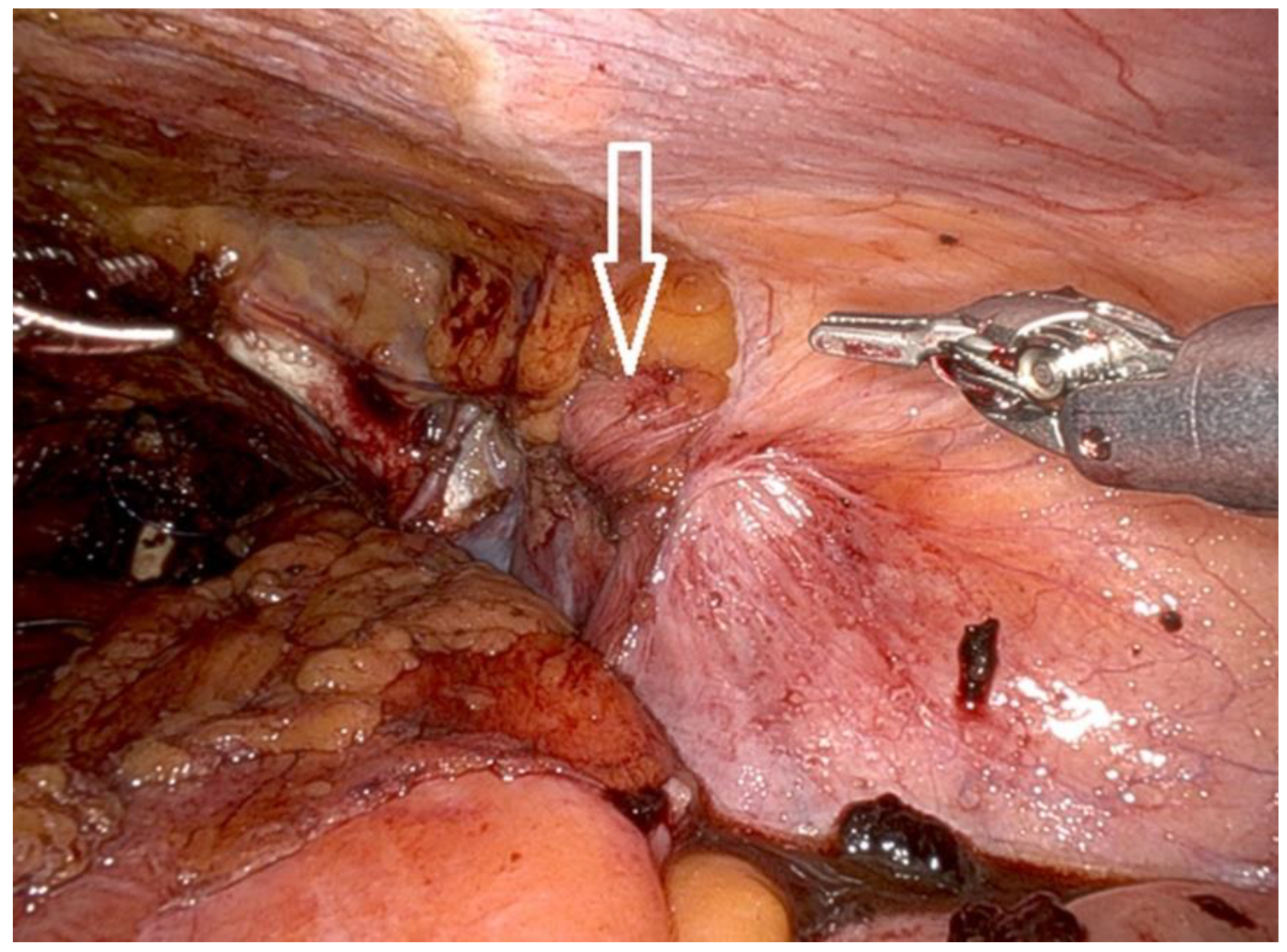

- The renal artery was isolated (Figure 3), clamped during the tumor resection, and unclamped after renorrhaphy.

- ◦

- The renal tumor was excised with a margin of healthy tissue.

- ◦

-

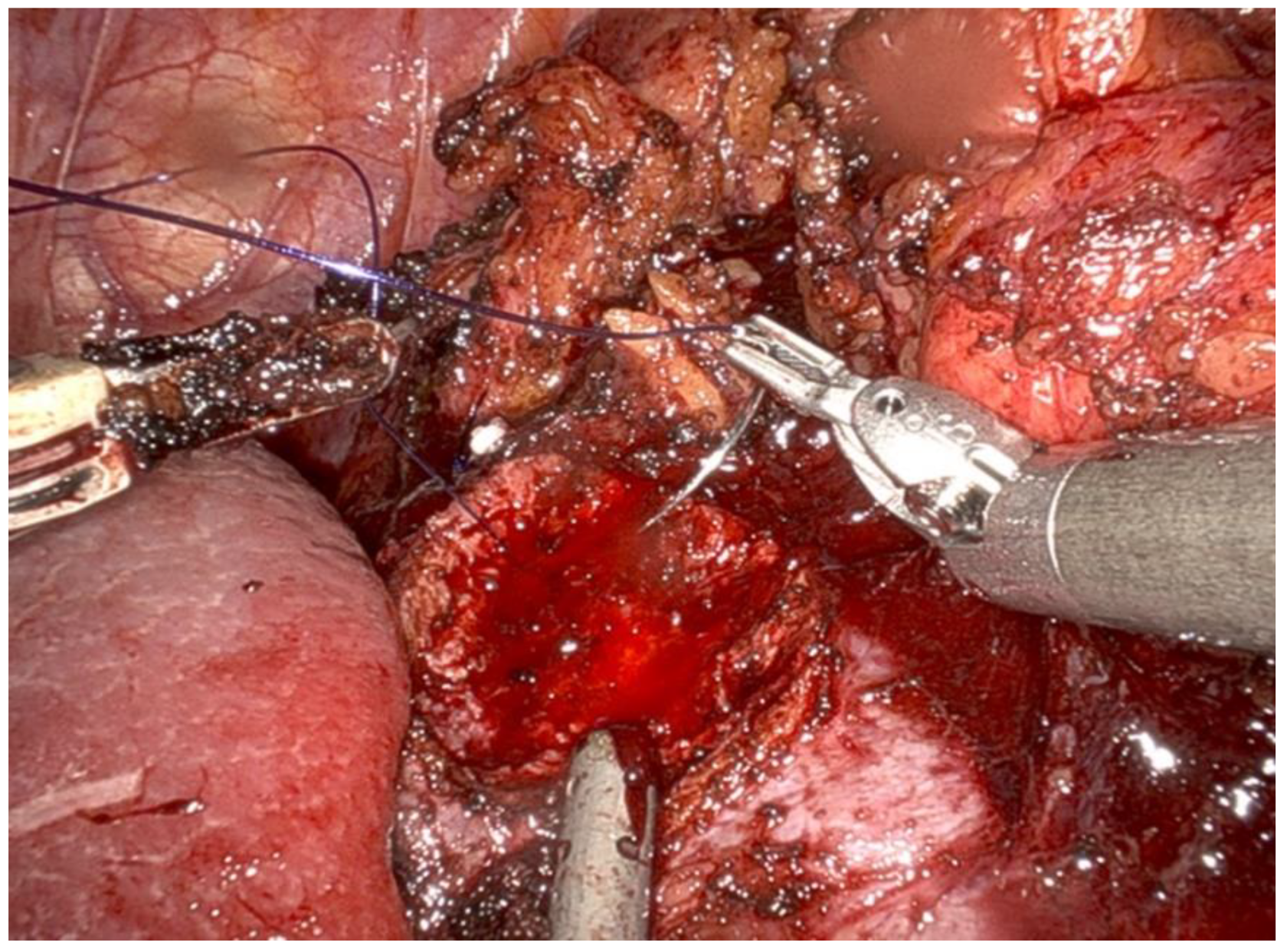

Renal reconstruction (renorrhaphy) was performed using a two-layer closure technique:

- ▪

- The inner layer was closed using a 3-0 monofilament suture on a 26 mm needle (Figure 4).

- ▪

- The outer layer (fibrous capsule and tumor bed) was closed using a barbed 3-0 V-lock™ suture on a 26 mm needle, with Hem-o-lock™ clips and TachoSil™ hemostatic material placed under the outer sutures.

- ◦

- After decompression of the renal artery, hemostasis was verified at the pressure of a 6 mm column of mercury inside the peritoneal cavity.

- ◦

- The kidney tumor was pulled out in the Endo Bag™ with the assistant’s trocar.

- 2.

-

Repositioning:

- ◦

- After the completion of RAPN, the robotic system was undocked.

- ◦

- Arm 4 switched position to the opposite side in the da Vinci X robotic system.

- ◦

- The patient was repositioned to the supine Trendelenburg position at a 30-degree angle, and the robotic system was re-docked for RARP.

- 3.

-

Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy (RARP):

- ◦

- Trocar placement for RARP was modified by using the previous incisions from the RAPN procedure. Four 8 mm robotic trocars and two 11 mm laparoscopic trocars were used (a total number of six) (Figure 5).

- ◦

- The fourth robotic arm port was closed, and two new incisions were made: one for a laparoscopic trocar and one for a robotic trocar.

- ◦

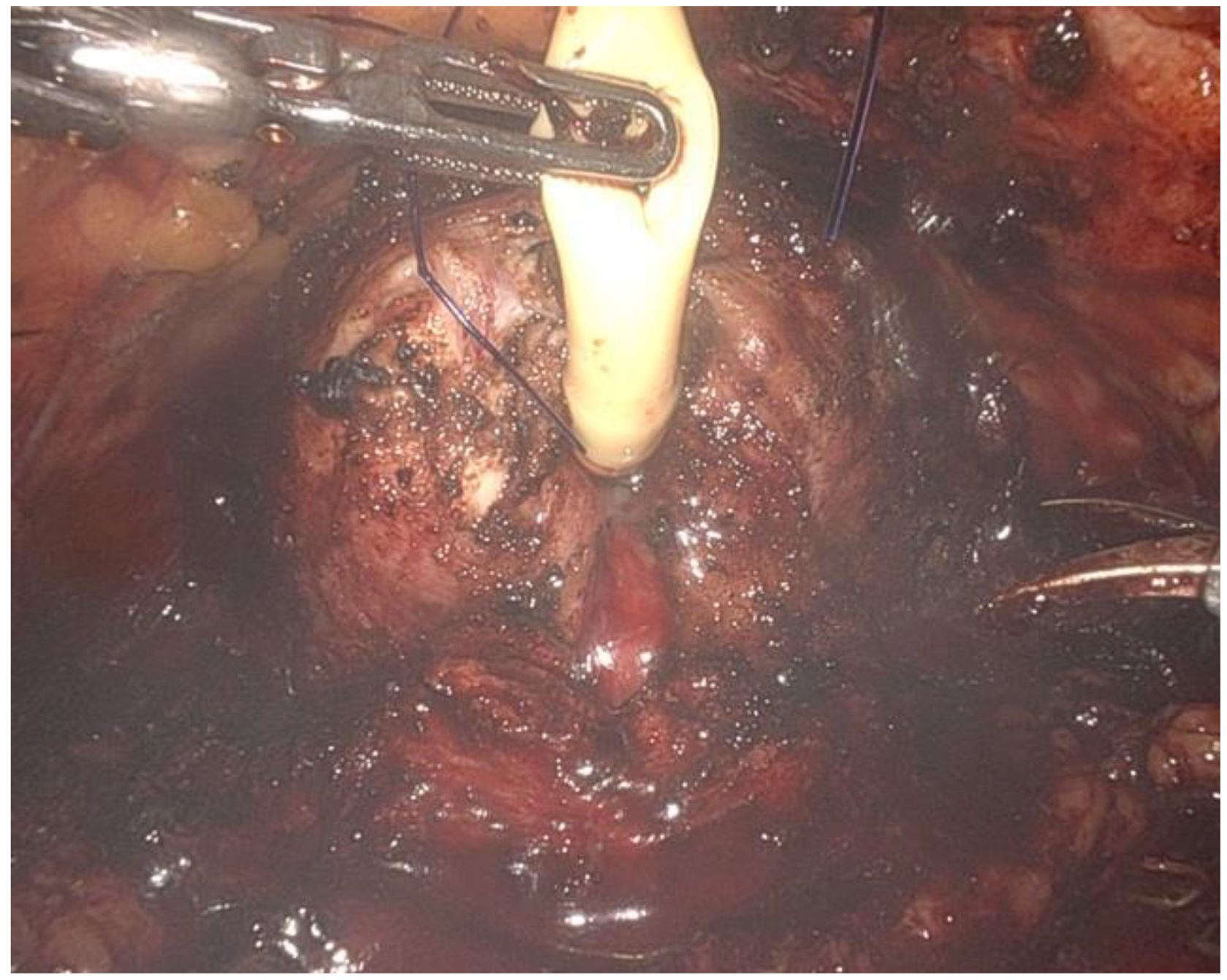

- The key steps included the dissection of the prostate with bladder neck sparing when possible (Figure 6), control of the dorsal venous complex, nerve-sparing techniques when applicable, and vesicourethral anastomosis with a continuous double-needle suture.

- ◦

- A bladder–urethral anastomosis leak test of 300 mL in the bladder was performed.

- ◦

- The prostatectomy specimen was pulled out with the assistant’s trocar in the Endo Bag™.

- ◦

- Only one 18 Ch Redon drain was inserted into the peritoneal cavity after the combined procedure.

- 4.

-

Robotic Instruments

- ◦

-

The same robotic instruments were used for both procedures:

- ▪

- Large needle driver;

- ▪

- ProGrasp forceps;

- ▪

- Monopolar curved scissors;

- ▪

- Fenestrated bipolar forceps.

- II.

- RARP + RTAPPIHR

- ▪

- Large needle driver;

- ▪

- ProGrasp forceps;

- ▪

- Monopolar curved scissors;

- ▪

- Maryland bipolar forceps.

- 1.

-

Patient Preparation and Port Placement:

- ◦

- The patient is positioned in a steep Trendelenburg position to enhance access to the abdominal cavity and pelvic anatomical structures.

- ◦

- A six-port configuration is typically employed to facilitate optimal access to both the prostate and the inguinal regions.

- 1.

-

Dissection and Identification of the Hernia:

- ◦

- Following mobilization of the prostate and incision of the endopelvic fascia, the surgeon inspects the inguinal regions for the presence of hernias.

- ◦

- Indirect hernias are identified by a dilated internal ring (Figure 7), while direct hernias are recognized due to defects medial to the epigastric vessels.

- 1.

-

Reduction of the Hernia Sac:

- ◦

- The hernia sac is carefully dissected and reduced back into the abdominal cavity, ensuring that no contents remain within it.

- 1.

-

Mesh Placement:

- ◦

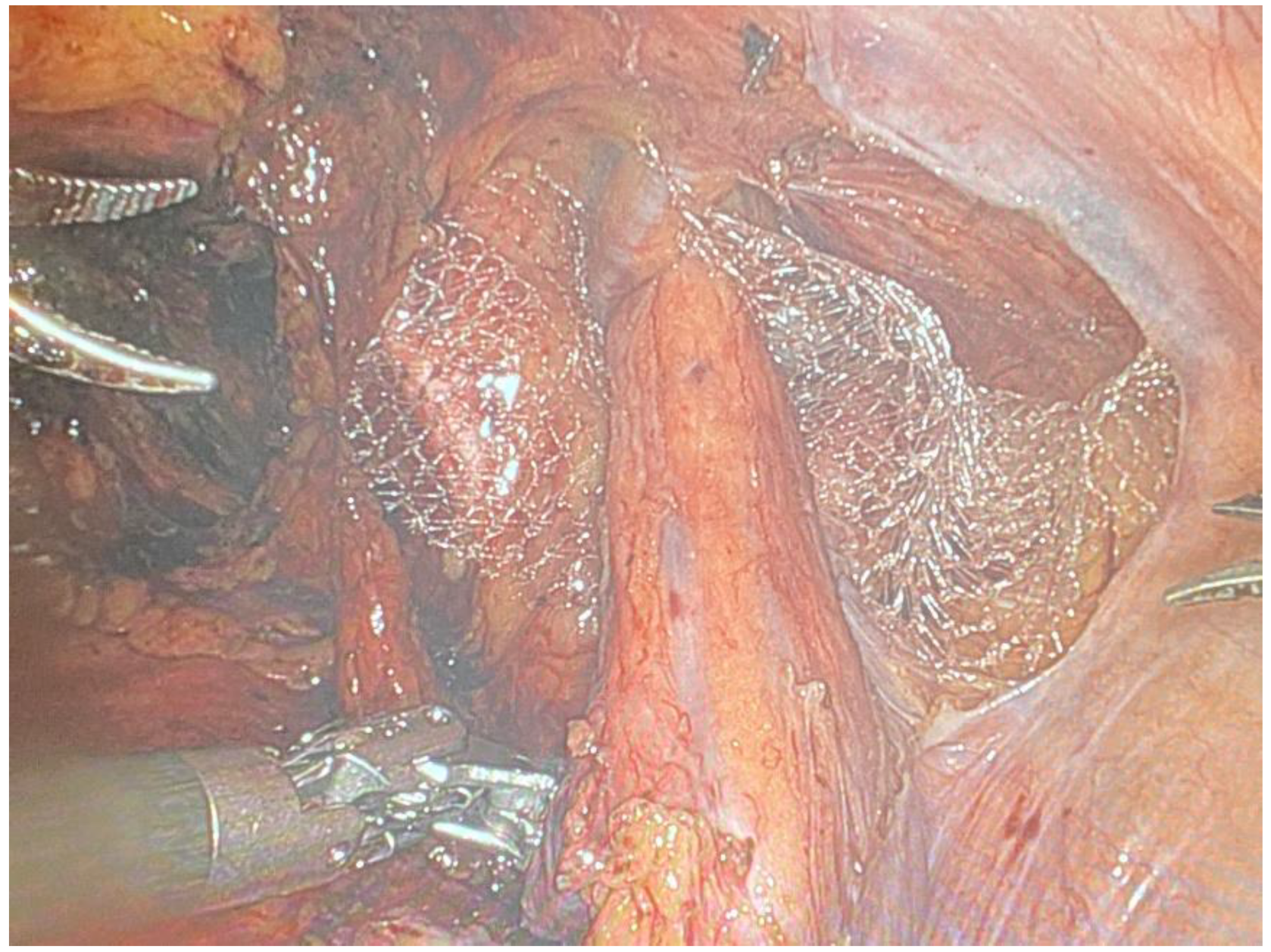

- A polypropylene mesh is selected for its strength and compatibility with biological tissues. The size of the mesh is determined by the dimensions of the defect.

- ◦

- The mesh is introduced into the abdominal cavity and positioned over the hernia defect (Figure 8) through the assistant laparoscopic port, ensuring adequate coverage to prevent recurrence.

- 1.

-

Fixation of the Mesh:

- ◦

- The mesh is secured using non-absorbable sutures, with fixation points typically including Cooper’s ligament and the transversalis fascia. Care is taken to avoid major blood vessels and nerves to prevent complications such as bleeding or chronic pain.

- 1.

-

Completion of Prostatectomy:

- ◦

- After the hernia repair, the prostatectomy is completed, including lymph node dissection (if indicated), specimen extraction, and vesicourethral anastomosis.

- 1.

-

Reperitonealization:

- ◦

- The peritoneal flap is closed over the mesh using a continuous suturing technique at the end of surgery. This step is vital to prevent bowel adhesions and mesh migration, which are potential complications of intra-abdominal mesh placement.

- ◦

- A final inspection ensures hemostasis and the integrity of the repair before the abdominal incisions are closed.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis for the Review of the Literature

- Operative time (total surgery time and console time for each separate procedure, if available);

- Estimated blood loss;

- Perioperative complications;

- Pathological outcomes, including biopsy results and post-prostatectomy histopathology in Gleason scores, as well as post-partial nephrectomy histopathology;

- Hemoglobin levels pre- and post-operation;

- Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) levels pre- and post-operation (24 h after surgery if available);

- Hospitalization period;

- Indications for surgery (if needed to be explained).

3.4. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

4.1. Overview

4.2. Cumulative Analysis

- I.

- Concurrent RARP + RAPN

- 1.

-

Operative Time:

- ◦

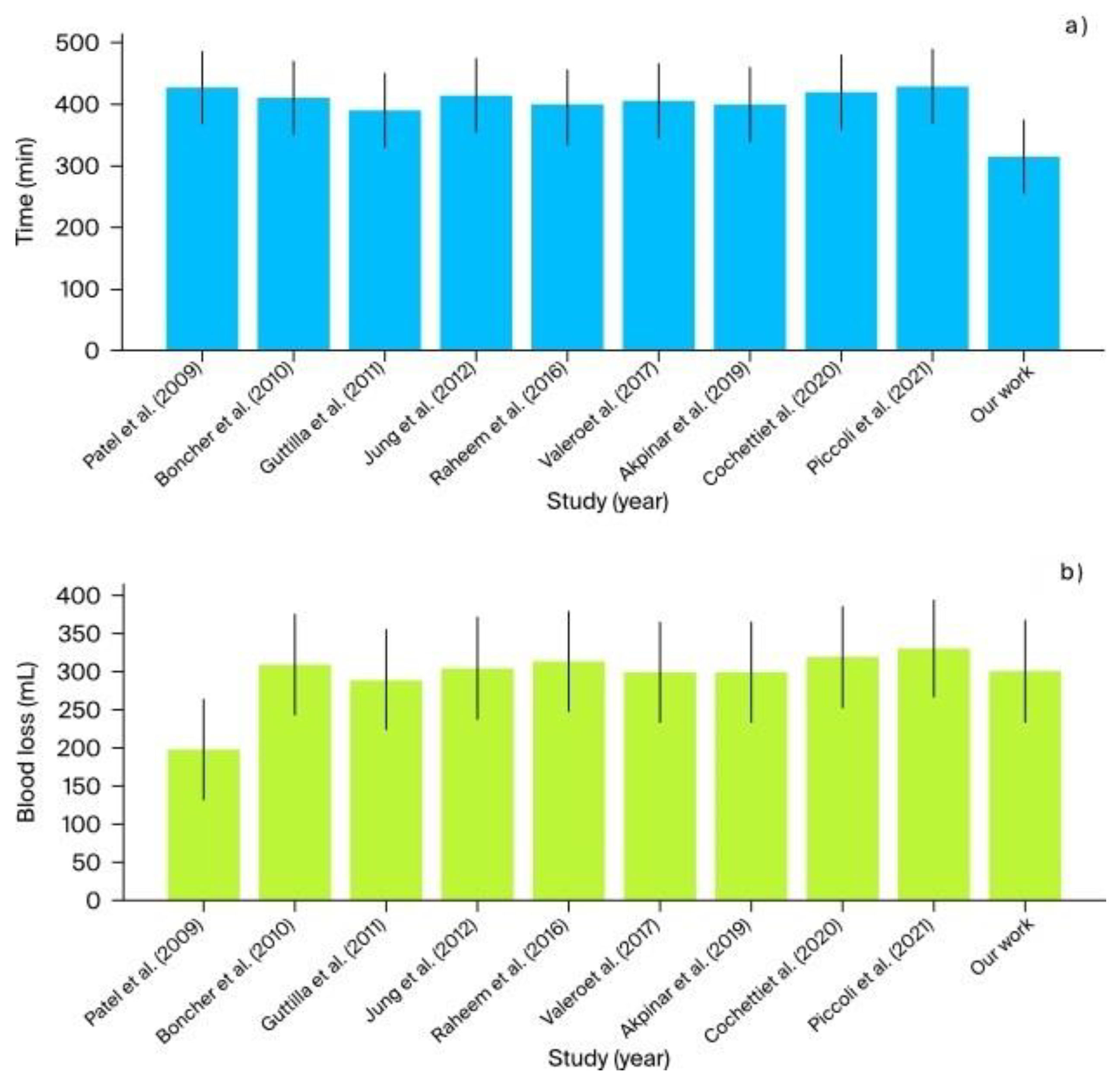

- The mean operative time across studies ranged from 390 to 430 min. In comparison, our institutional study reported the shortest operative time of 315 min, demonstrating higher efficiency (Figure 9).

- 2.

-

Console Time:

- ◦

- Console times varied between 250 and 335 min across the studies. Our institutional data showed a console time of 270 min, which falls within this range and indicates a consistent performance.

- 3.

-

Estimated Blood Loss:

- ◦

- Blood loss was generally low across studies, averaging between 200 and 330 mL. Our study reported an estimated blood loss of 300 mL, which is consistent with the range observed in other studies (Figure 9).

- 4.

-

Complications:

- ◦

- None of the reviewed studies, including ours, reported significant perioperative complications (Clavien–Dindo), confirming the overall safety of the procedure.

- 5.

-

Positive Surgical Margins:

- ◦

- While positive surgical margins were observed in a small percentage of cases across various studies, none were reported in our study, highlighting the precision of our surgical technique.

- 6.

-

Renal Function:

- ◦

- The postoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) generally showed a slight decline immediately but had stabilized by the one-month follow-up in most studies, with values ranging between −4 and −5 mL/min/1.73 m². Notably, our study showed an increase in eGFR of +24.85 mL/min/1.73 m², indicating an exceptional renal function outcome compared with the other studies. Comprehensive postoperative care, including meticulous management of hydration and renal perfusion, can aid in the recovery of renal function.

- 7.

-

Hospitalization:

- ◦

- The length of hospital stay varied between 2 and 8 days in the reviewed studies. Our institutional study reported a hospitalization time of 5.5 days, which is within this range and suggests comparable postoperative recovery times.

- II.

- Concurrent RARP + Robotic Inguinal Hernia Repair (IHR)

- 1.

-

Operative Time:

- ◦

- The operative time reported in the literature ranged from 140 to 192.5 min, with additional values being indicated as “+10 over RARP” and “+24 over RARP”. In our study, the average operative time was 221.6 min, exceeding the upper end of this range. This extended duration may be attributed to the complexity and precision required in our surgical procedures (one patient with concomitant locally advanced prostate cancer and three hernia sites), which could involve more intricate steps and careful handling of anatomical structures.

- 2.

-

Estimated Blood Loss:

- ◦

- The blood loss reported in the studies varied from 50 to 175 mL. Our study documented an average estimated blood loss of 358.3 mL, which was significantly higher than the values reported in the literature. This notable difference might be due to various aforementioned factors, patient comorbidities, and the meticulous recording of intraoperative blood loss in our institution. Further investigation into intraoperative blood management strategies could be beneficial.

- 3.

-

Complications:

- ◦

- Complications were generally minimal across all studies, with descriptions ranging from “None” to “Minor”. In our study, complications were classified as “Minor (Grade I–II)”, aligning with the literature and confirming the procedural safety. The low rate of significant complications underscores the efficacy of our surgical technique and postoperative care protocols.

- 4.

-

Recurrence Rate:

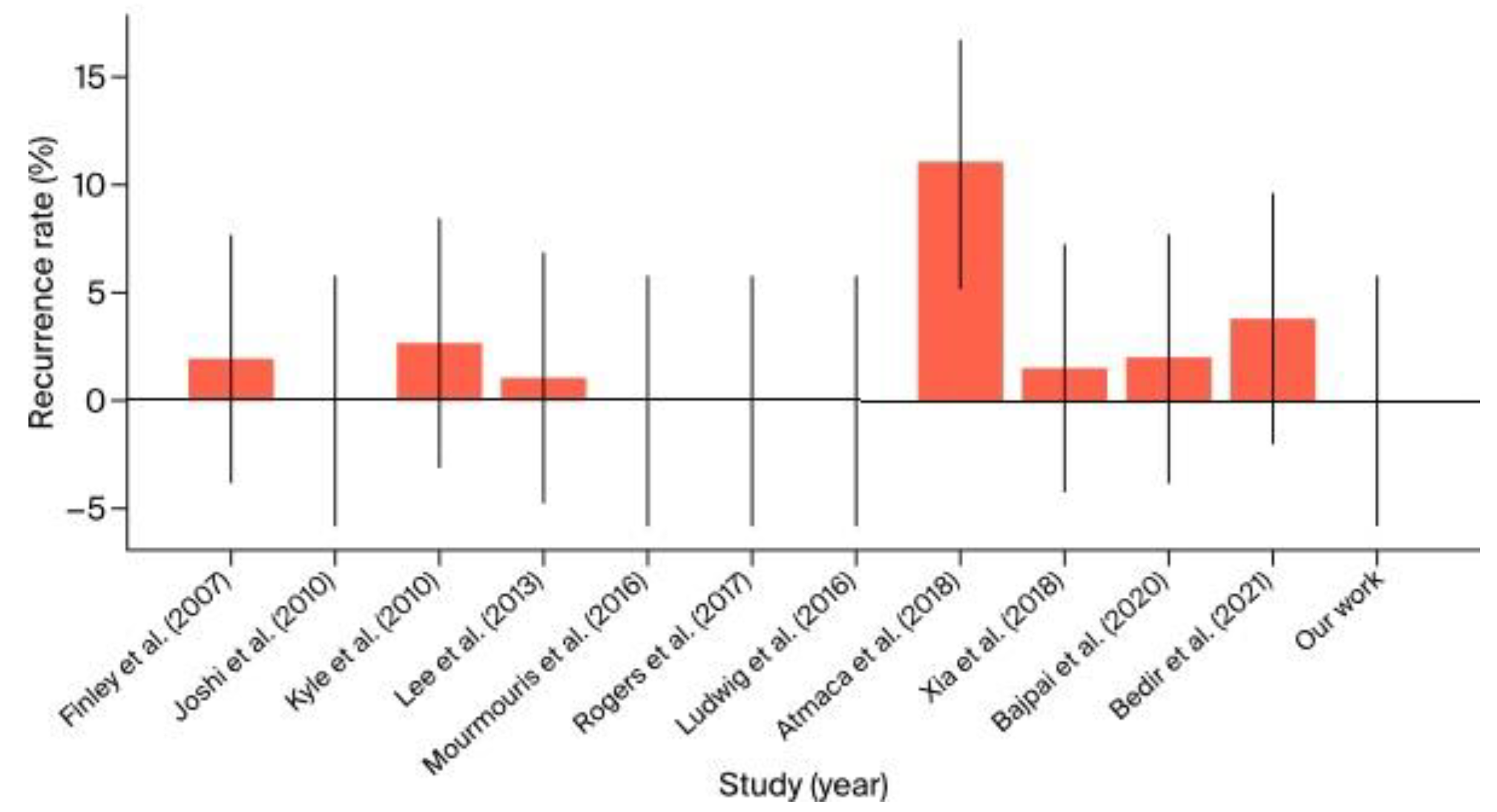

- ◦

- The recurrence rate in the literature ranged from 0% to 11%. Our study noted an absence of recurrences, which is consistent with the best outcomes in the literature. This suggests that our surgical methods are highly effective in achieving durable repairs and preventing recurrence (Figure 10).

- 5.

-

Hernia Side:

- ◦

- The reviewed studies predominantly reported unilateral hernias, with bilateral cases being less common. In our study, we observed two cases of a right-sided hernia and one bilateral case with an additional epigastric (linea alba) hernia. This distribution is in line with the literature, indicating that our patient cohort is representative of the general population undergoing similar procedures.

- 6.

-

Patient BMI:

- ◦

- The average BMI reported in the studies ranged from 26.47 to 28.0 kg/m². Our study did not provide data on BMI, which limits direct comparison. However, future studies should include BMI as a variable to better understand its impact on surgical outcomes and to allow for a more comprehensive analysis.

- 7.

-

Hospital Stay:

- ◦

- The length of hospital stay varied from 1 to 6 days in the reviewed studies. Our study reported an average hospital stay of 7 days, slightly exceeding the upper range reported in the literature. This prolonged hospitalization might reflect our institution’s cautious approach to pre-, intra-, and postoperative care, ensuring complete recovery before discharge in complex cases. Reviewing and optimizing postoperative protocols could potentially reduce the length of stay without compromising patient safety.

- 8.

-

Follow-Up Period:

- ◦

- The follow-up period in the literature ranged from 9 to 36.6 months. Our study had a follow-up period ranging from 15 to 35 months, which is consistent with the literature. Adequate follow-up is crucial for monitoring long-term outcomes and ensuring the durability of surgical repairs.

- III.

- Other Concurrent Robotic Multisite Surgery Procedures

- 1.

-

Limited Case Volume:

- ◦

- The surgical interventions discussed, including robot-assisted adrenalectomy (RAA) in conjunction with robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) and robot-assisted cystolithotomy (RACLT) performed concurrently with robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP), are rarely performed surgical procedures. Both our institutional data and existing literature emphasize that these procedures reserved for selected cases, reflecting their niche status in urological robotic surgery.

- 2.

-

Non-Standardized, Individualized Approaches:

- ◦

- These procedures often represent customized surgical solutions tailored to the unique clinical situations of patients with complex or concurrent pathologies. The inherent variability in these surgical combinations presents a challenge in establishing a standardized protocol or reliably predicting outcomes across different patient populations.

- 3.

-

Limitations in Deriving Conclusive Evidence:

- ◦

- The small number of cases analyzed makes it difficult to derive definitive conclusions regarding the overall safety and efficacy of these interventions. Although the outcomes from both our institution and the broader literature suggest that these surgeries can be performed with a favorable safety profile and minimal complications, the limited scope of available data necessitates cautious interpretation when considering broader applications.

- 4.

-

Contextual Understanding and Observational Insights:

- ◦

- Despite the constraints imposed by the small sample size, certain trends emerge from the data. The operative times, intraoperative blood loss, and complication rates observed in our cases are consistent with those documented in the literature, implying that these complex procedures can yield satisfactory outcomes with meticulous patient selection and surgical precision. However, the slightly prolonged hospital stays in our cohort, in comparaison to those reported in the literature, might indicate a more conservative approach to postoperative care, which should be reevaluated in order to streamline recovery protocols.

5. Discussion

- I.

- RARP + RAPN

- II.

- RARP + RTAPPIHR

- III.

- Other Concurrent Urological Robotic Multisite Surgery Procedures

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boncher, N.; Vricella, G.; Greene, G.; Madi, R. Concurrent Robotic Renal and Prostatic Surgery: Initial Case Series and Safety Data of a New Surgical Technique. J. Endourol. 2010, 24, 1625–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, A.A.; Santok, G.D.; Kim, D.K.; Troya, I.S.; Alabdulaali, I.; Choi, Y.D.; Rha, K.H. Simultaneous Retzius-Sparing Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy and Partial Nephrectomy. Int. Neurourol. J. 2016, 57, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochetti, G.; Cocca, D.; Maddonni, S.; Paladini, A.; Sarti, E.; Stivalini, D.; Mearini, E. Combined Robotic Surgery for Double Renal Masses and Prostate Cancer: Myth or Reality? Medicina 2020, 56, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.N.; Eun, D.; Menon, M.; Rogers, C.G. Combined Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Partial Nephrectomy and Radical Prostatectomy. J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg. 2009, 13, 229–232. [Google Scholar]

- Guttilla, A.; Crestani, A.; Zattoni, F.; Secco, S.; Dal Moro, F.; Valotto, C.; Zattoni, F. Combined Robotic-Assisted Retroperitoneoscopic Partial Nephrectomy and Extraperitoneal Prostatectomy. Urologia 2012, 79, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.H.; Arkoncel, F.R.P.; Lee, J.W.; Oh, C.K.; Yusoff, N.A.M.; Kim, K.J.; Rha, K.H. Initial Clinical Experience of Simultaneous Robot-Assisted Bilateral Partial Nephrectomy and Radical Prostatectomy. Yonsei Med. J. 2012, 53, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, R.; Sawczyn, G.; Garisto, J.; Yau, R.; Kaouk, J. Multiquadrant Combined Robotic Radical Prostatectomy and Left Partial Nephrectomy: A Combined Procedure by a Single Approach. Actas Urol. Esp. 2020, 44, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, C.; Suer, E.; Turkolmez, K.; Beduk, Y. Combined Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy and Partial Nephrectomy: Rare Coincidence. Urology 2019, 128, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, M.; Esposito, S.; Pecchini, F.; Francescato, A.; Colli, F.; Gozzo, D.; Trapani, V.; Alboni, C.; Rocco, B. Full Robotic Multivisceral Resections: The Modena Experience and Literature Review. Updates Surg. 2021, 73, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, D.S.; Rodriguez, E., Jr.; Ahlering, T.E. Combined Inguinal Hernia Repair with Prosthetic Mesh During Transperitoneal Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy: A 4-Year Experience. J. Urol. 2007, 178, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.R.T.; Spivak, J.; Rubach, E.; Goldberg, G.; DeNoto, G. Concurrent Robotic Trans-Abdominal Pre-Peritoneal (TAP) Herniorrhaphy During Robotic-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2010, 6, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyle, C.C.; Hong, M.K.H.; Challacombe, B.J.; Costello, A.J. Outcomes after Concurrent Inguinal Hernia Repair and Robotic-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy. J. Robot. Surg. 2010, 4, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.K.; Montgomery, D.P.; Porter, J.R. Concurrent Transperitoneal Repair for Incidentally Detected Inguinal Hernias During Robotically Assisted Radical Prostatectomy. Urology 2013, 82, 1320–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourmouris, P.; Argun, O.B.; Tufek, I.; Obek, C.; Skolarikos, A.; Tuna, M.B.; Keskin, S.; Kural, A.R. Nonprosthetic Direct Inguinal Hernia Repair During Robotic Radical Prostatectomy. J. Endourol. 2016, 30, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, W.W.; Sopko, N.A.; Azoury, S.C.; Dhanasopon, A.; Mettee, L.; Dwarakanath, A.; Steele, K.E.; Nguyen, H.T.; Pavlovich, C.P. Inguinal hernia repair during extraperitoneal robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. J. Endourol. 2016, 30, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, T.; Parra-Davila, E.; Malcher, F.; Hartmann, C.; Mastella, B.; de Araújo, G.; Ogaya-Pinies, G.; Ortiz-Ortiz, C.; Hernandez-Cardona, E.; Patel, V.; et al. Robotic Radical Prostatectomy with Concomitant Repair of Inguinal Hernia: Is It Safe? Robot. Surg. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, A.F.; Hamidi, N.; Canda, A.E.; Keske, M.; Ardicoglu, A. Concurrent Repair of Inguinal Hernias with Mesh Application During Transperitoneal Robotic-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: Is It Safe? Urol. J. 2018, 15, 2955–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Taylor, B.L.; Patel, N.A.; Chelluri, R.R.; Raman, J.D.; Scherr, D.S.; Guzzo, T.J. Concurrent Inguinal Hernia Repair in Patients Undergoing Minimally-Invasive Radical Prostatectomy: A National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Study. J. Endourol. 2018, 32, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, R.R.; Razdan, S.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Razdan, S. Simultaneous Robotic Assisted Laparoscopic Prostatectomy (RALP) and Inguinal Herniorrhaphy (IHR): Proof-of-Concept Analysis from a High-Volume Center. Hernia 2019, 23, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedir, F.; Altay, M.S.; Kocatürk, H.; Bedir, B.; Hamidi, N.; Canda, A.E. Concurrent Inguinal Hernia Repair During Robot-Assisted Transperitoneal Radical Prostatectomy: Single Center Experience. Robot. Surg. Res. Rev. 2021, 8, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.Y.; Sooriakumaran, P.; Peters, D.L.; Srivastava, A.; Tewari, A. Cystolithotomy during robotic radical prostatectomy: Single-stage procedure for concomitant bladder stones. Indian J. Urol. 2012, 28, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, F.I.; O'Connor, J.; Mittal, V.K.; Hurley, P. Robotic removal of eroded vaginal mesh into the bladder. Int. J. Urol. 2013, 20, 1144–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sappal, S.; Sulek, J.; Smith, S.C.; Hampton, L.J. Intrarenal adrenocortical adenoma treated by robotic partial nephrectomy with adrenalectomy. J. Endourol. Case Rep. 2016, 2, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, Z.G.; Liaw, C.W.; Reddy, A.; Mehrazin, R. Robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy and adrenalectomy: Case of a pheochromocytoma invading into renal parenchyma. Case Rep. Urol. 2020, 2020, 7321015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, E.J.; Linder, B.J. Robotic-assisted intravesical mesh excision following retropubic midurethral sling. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2024, 35, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.H.; Kim, H.W.; Oh, C.K.; Song, J.M.; Chung, B.H.; Hong, S.J.; Rha, K.H. Simultaneous Robot-Assisted Laparoendoscopic Single-Site Partial Nephrectomy and Standard Radical Prostatectomy. Yonsei Med. J. 2014, 55, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, A.R.; Moschovas, M.C.; Rogers, T.; Saikali, S.; Perera, R.; Loy, D.G.; Sandri, M.; Roof, S.; Diaz, K.; Ortiz, C.; et al. Simultaneous hernia repair following robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy is safe with low rates of mesh-related complications. J. Robot Surg. 2023, 17, 1653–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Palou, F.G.; Sánchez-Ortiz, R.F. Outcomes of minimally invasive inguinal hernia repair at the time of robotic radical prostatectomy. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2017, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisipati, S.; Bach, C.; Daneshwar, D.; Rowe, E.W.; Koupparis, A.J. Concurrent upper and lower urinary tract robotic surgery: A case series. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2014, 8, e853–e858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Sangalli, M.; Zanoni, M.; Ghezzi, M.; Fabbri, F.; Sozzi, F.; Rigatti, P.; Cestari, A. Incidental retroperitoneal paraganglioma in patient candidate to radical prostatectomy: Concurrent surgical treatments by robotic approach. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2015, 9, E539–E541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonooka, T.; Takiguchi, N.; Ikeda, A.; Soda, H.; Hoshino, I.; Sato, N.; Iwatate, Y.; Nabeya, Y. A case of concurrent robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy and laparoscopic ileocecal resection for synchronous cancer of the kidney and ascending colon. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 2019, 46, 166–168. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Flavin, K.; Prasad, V.; Gowrie-Mohan, S.; Vasdev, N. Renal physiology and robotic urological surgery. Eur. Med. J. Urol. 2017, 2, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, M.; Piramide, F.; Amparore, D.; Burgio, M.; Busacca, G.; Colombo, M.; Piana, A.; De Cillis, S.; Checcucci, E.; Fiori, C.; et al. Augmented reality: The smart way to guide robotic urologic surgery. Mini-Invasive Surg. 2022, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashira, I.; Kato, R.; Ishizaka, K. Development of a humanoid hand system to support robotic urological surgery. In Proceedings of the 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Glasgow, Scotland, UK; 2022; pp. 4849–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhu, G.; Li, H.; Francisco, P.J.M. Application of 3D Image Reconstruction in Robotic Urological Surgery. Chin. J. Urol. 2018, 39, 690–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sherbiny, A.; Eissa, A.; Ghaith, A.; Morini, E.; Marzotta, L.; Sighinolfi, M.C.; Micali, S.; Bianchi, G.; Rocco, B. Training in Urological Robotic Surgery: Future Perspectives. Arch. Esp. Urol. 2018, 71, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, A.J.; Patil, M.B.; Zehnder, P.; Cai, J.; Ng, C.K.; Aron, M.; Gill, I.S.; Desai, M.M. Concurrent and predictive validation of a novel robotic surgery simulator: A prospective, randomized study. J. Urol. 2012, 187, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.; Rai, B.; Madaan, S.; Chedgy, E.; Somani, B. The availability, cost, limitations, learning curve and future of robotic systems in urology and prostate cancer surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassetti, A.; Ragusa, A.; Tedesco, F.; Prata, F.; Cacciatore, L.; Iannuzzi, A.; Bove, A.M.; Anceschi, U.; Proietti, F.; D’annunzio, S.; et al. Robotic surgery in urology: History from PROBOT® to HUGOTM. Sensors 2023, 23, 7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, A.; Claros, O.R.; Cha, J.D.; Kayano, P.P.; Apezzato, M.; Wagner, A.A.; Lemos, G.C. Can remote assistance for robotic surgery improve surgical performance in simulation training? A prospective clinical trial of urology residents using a simulator in South America. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2022, 48, 952–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient Number | Operation Date | Hospitalization Period | Preoperative Hemoglobin (mmol/L) | Postoperative Hemoglobin (mmol/L) |

Preoperative eGFR* (mL/min/1.73 m²) |

Postoperative eGFR* (mL/min/1.73 m²) |

Preoperative Prostate Cancer Clinical Stage and Biopsy Result | Post-Prostatectomy Stage and Histopathology Result | Preoperative Kidney Tumor Clinical Stage and Side | Postoperative Kidney Tumor Histopathology Result | Total Operative Time (min.) | Console Time (min.) |

Estimated Blood Loss (mL) |

Complications (Clavien–Dindo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (of 4) | 30.06.2023 | 27.06.2023–04.07.2023 7 days in total 4 days postoperatively |

8.9 | 8.3 | 66.1 | 99.5 | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 8 (4 + 4) ISUP Grade 4 cT2bN0M0 |

Adenocarcinoma Gleason 8 (4 + 4) ISUP Grade 4 pT2cN0M0R0 5 lymph nodes dissected during extended pelvic lymph node dissection |

cT1a solid tumor right side, upper pole |

Oncocytoma without involvement of surrounding fatty tissue R0 | 345 | RAPN 105 REPOSITIONING 50 RARP + extended pelvic lymph node dissection 190 |

350 | None |

| 2 (of 4) | 13.12.2023 | 12.12.2023–16.12.2023 4 days in total 3 days postoperatively |

9.4 | 9.1 | 73.6 | 89.9 | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 7 (3 + 4) ISUP Grade 2 cT2bN0M0 |

Adenocarcinoma Gleason 7 (3 + 4) ISUP Grade 2 pT2cN0M0R0 without end |

cT2a cystic tumor Bosniak III right side, posterior aspect |

pT0 Necrotic connective tissue fragments in the form of a cyst; neoplastic tissue was not found. |

285 | RAPN 65 REPOSITIONING 30 RARP 180 |

250 | None |

| Patient Number | Operation Date | Hospitalization Period | Preoperative Hemoglobin (mmol/L) | Postoperative Hemoglobin (mmol/L) | Preoperative eGFR* (mL/min/1.73m²) | Postoperative eGFR* (mL/min/1.73m²) | Preoperative Prostate Cancer Clinical Stage and Biopsy Result | Post-Prostatectomy Stage and Histopathology Result | Preoperative Kidney Tumor Clinical Stage and Side | Preoperative Kidney Tumor Histopathology Result | Total Operative Time (min.) | Console Time (min.) | Estimated Blood Loss (mL) | Complications (Clavien–Dindo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 (of 4) | RARP (2nd) 11.09.2023 RAPN (1st) 05.07.2023 extensive adhesions in the peritoneal cavity, perirenal “toxic fat” | RARP (2nd) 06.09.2023—15.09.2023 9 days in total 4 days postoperatively RAPN (1st) 28.06.2023–09.07.2023 11 days in total 4 days postoperatively | RARP 8.5 RAPN 8.5 | RARP 6.9 RAPN 7.7 | RARP 96.5 RAPN 93.6 | RARP 95.6 RAPN 87.4 | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 7 (3 + 4) ISUP Grade 2 cT2bN0M0 | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 7 (3 + 4) ISUP Grade 2 pT2cN0M0R0 without extended pelvic lymph node dissection | cT1a solid tumor left side, upper pole | pT0 Histo-oncological changes in the examined material were absent | RAPN 210 RARP 225 | RAPN 170 RARP 205 | RAPN 350 RARP 550 | Grade II Fever, treated with antibiotic therapy |

| 4 (of 4) | RARP + extended pelvic lymph node dissection 13.02.2024 RAPN 27.05.2024 | RARP + extended pelvic lymph node dissection (1st) 12.02.2024–17.02.2024 5 days in total 4 days postoperatively RAPN (2nd) 26.05.2024–31.05.2024 5 days in total 4 days postoperatively | RARP + extended pelvic lymph node dissection 8.4 RAPN 8.8 | RARP + extended pelvic lymph node dissection 7.6 RAPN 7.9 | RARP + extended pelvic lymph node dissection 88.9 RAPN 79.1 | RARP + extended pelvic lymph node dissection 63.6 RAPN 72.3 | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 7 (4 + 3) ISUP Grade 3 cT3N1M0 locally advanced tumor, preoperative PSA 64 ng/ml | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 8 (4 + 4) ISUP Grade 4 pT2cN0M0 7 lymph nodes dissected during extended pelvic lymph node dissection | cT1b cystic tumor Bosniak III left side, posterior aspect | Papillary renal cell carcinoma, type 1, G2). The tumor mass showed foci of necrosis and congestion. pT1bR0 | RAPN 230 RARP + extended pelvic lymph node dissection 230 | RAPN 200 RARP + extended pelvic lymph node dissection 195 | RAPN 300 RARP 250 | None |

| Patient Number | Operation Date | Hospitalization Period | Preoperative Hemoglobin (mmol/l) | Postoperative Hemoglobin (mmol/l) | Preoperative eGFR* (ml/ min/ 1,73 m²) | Postoperative eGFR* (ml/ min/ 1,73 m²) | Preoperative Prostate Cancer Clinical Stage and Biopsy Result | Post-Prostatectomy Stage and Histopathology Result | Hernia side | Total Operative Time (min.) | RARP Console Time (min.) | Inguinal Hernia repair Console Time (min.) | Estimated Blood Loss (ml) | Complications (Clavien–Dindo) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (of 3) | 17.08.2021 | 11.08.2021–20.08.2021 9 days in total 3 days postoperatively | 9,8 | N/A | 92,2 | N/A | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 6 (3 + 3) ISUP Grade 1 cT2aN0M0 | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 6 (3 + 3) ISUP Grade 1 pT2aN0MxR0 | RIGHT SIDE | 195 | 135 | 25 | 150 | Grade I SARS-CoV-2 infection requiring antipyretics | |

| 2 (of 3) | 20.10.2021 + extended pelvic lymph node dissection | 18.10.2021–25.10.2021 7 days in total 5 days postoperatively | 9,7 | 9,2 | 81 | N/A | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 7 (3 + 4) ISUP Grade 2 cT3N0M0 | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 7 (4 + 3) ISUP Grade 3 pT3aN0MxR0 | RIGHT SIDE | 200 | 165 | 40 | 225 | NONE | |

| 3 (of 3) | 09.02.2023 + extended pelvic lymph node dissection | 08.02.2023–13.02.2023 5 days in total 4 days postoperatively | 8,6 | 5,9 | 66,3 | 82,5 | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 7 (3 + 4) ISUP Grade 2 cT2bN0M0 | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 8 (4 + 4) ISUP Grade 4 pT3bN0MxR1 single-point positive surgical margin | BOTH SIDES + EPIGASTRIC HERNIA (LINEA ALBA) | 270 | 155 | 65 | 700 | Grade II Red Cell Concentrate Transfusion |

| Patient Number | Operation Date and Type of Robotic Procedure | Indication | Hospitalization Period | Pre-operative Hemoglobin (mmol/L) | Postoperative Hemoglobin (mmol/L) |

Preoperative eGFR* (mL/min/1.73 m²) |

Postoperative eGFR* (mL/min/1.73 m²) |

Preoperative Prostate Cancer Clinical Stage and Biopsy Result | Post-Prostatectomy Stage and Histopathology Result | Postoperative Kidney Tumor Histopathology Result | Total Operative Time (min) | Console Time (min) | Estimated Blood Loss (mL) | Complications (Clavien–Dindo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (of 3) | 08.05.2023 RAPN + IPSILATERAL ROBOT-ASSISTED ADRENALECTOMY (RAA) |

cT4N0M0 PERIPHERAL UPPER POLE KIDNEY TUMOR WITH ADRENAL INVOLVEMENT |

07.05.2023–15.05.2023 8 days in total 7 days postoperatively |

8.6 | 8.0 | 107.7 | 123.2 | N/A | N/A | Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC Fuhrman 2 WHO G2 R0 |

265 | 230 | 800 | Grade II Red Cell Concentrate Transfusion |

| 2 (of 3) | 27.06.2023 ROBOT-ASSISTED TOTAL TRANS-OBTURATOR TAPE (TOT) REMOVAL + ROBOT-ASSISTED CYSTOLITHOTOMY (RACLT) |

INTRAVESICAL TRANS-OBTURATOR TAPE (TOT) EROSION WITH CONCOMITANT BLADDER STONE | 27.06.2023–04.07.2023 7 days in total 7 days postoperatively |

7.5 | 6.5 | 96.1 | 82.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 125 | 100 | 250 | None |

| 3 (of 3) | 29.12.2023 RALP + ROBOT-ASSISTED CYSTOLITHOTOMY (RACLT) |

ORGAN-CONFINED PROSTATE CANCER WITH CONCOMITANT BLADDER STONE | 28.12.2023–03.01.2024 6 days in total 5 days postoperatively |

8.7 | 8.2 | 98.1 | 103.6 | Adenocarcinoma Gleason 6 (3 + 3) ISUP Grade 1 cT2aN0M0 |

Adenocarcinoma Gleason 9 (4 + 5) ISUP Grade 5 pT2cN0M0R0 |

N/A | 165 | 130 | 200 | None |

| Study (Year of Surgery) | Country | Number of Patients | Robotic System | Institution | Mean Operative Time (min.) | Mean Console Time (min.) | Mean Estimated Blood Loss (mL) | Complications (Clavien-Dindo) |

Positive Surgical Margins | Mean Preoperative eGFR* (mL/min/1.73 m²) |

Mean Preoperative eGFR* (mL/min/1.73 m²) |

Calculated Mean Difference in eGFR* before and after Surgery (mL/min/1.73 m²) | Follow-Up | Mean Hospitalization Time (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patel et al. (2009) [4] | USA | 1 | da Vinci S | Henry Ford Hospital | 427 | 335 | 200 | None | None | N/A 1.1 mg/dL creatinine level |

N/A | N/A | 4 months | 2 |

| Boncher et al. (2010) [1] | USA | 4 | da Vinci S | Michigan State University | 410 | 270 | 310 | None | 1 | 82 | 78 | −4 | 1 month | 7 |

| Guttilla et al. (2011) [5] | Italy | 3 | da Vinci S | University of Padua | 390 | 250 | 290 | None | 0 | 83 | 78 | −5 | 1 month | 6 |

| Jung et al. (2012) [6] | South Korea | 5 | da Vinci Si | Seoul National University Hospital | 415 | 275 | 305 | None | 2 | 84 | 79 | −5 | 1 month | 7 |

| Raheem et al. (2016) [2] | South Korea | 6 | da Vinci Xi | Yonsei University College of Medicine | 395 | 255 | 315 | None | 2 | 80 | 75 | −5 | 1 month | 5 |

| Valero et al. (2017) [7] | USA | 3 | da Vinci Xi | Cleveland Clinic | 405 | 265 | 300 | None | 1 | 85 | 80 | −5 | 1 month | 6 |

| Akpinar et al. (2019) [8] | Turkey | 5 | da Vinci Xi | Istanbul University | 400 | 260 | 300 | None | 1 | 85 | 80 | −5 | 1 month | 7 |

| Cochetti et al. (2020) [3] | Italy | 6 | da Vinci Xi | University of Perugia | 420 | 280 | 320 | None | 1 | 80 | 75 | −5 | 1 month | 8 |

| Piccoli et al. (2021) [9] | Brazil | 7 | da Vinci Xi | Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre | 430 | 290 | 330 | None | 1 | 86 | 82 | −4 | 1 month | 7 |

| Drobot et al. (2023) | Poland | 2 | da Vinci X | Multidisciplinary Hospital in Warsaw-Miedzylesie | 315 | 270 | 300 | None | 0 | 69.85 | 94.7 | +24.85 | 12 months | 5.5 |

| Author (Year of Study) | Center (Country) | Number of Surgeries | Number of Hernia Repairs | Repair Method | Mean Operative Time (min.) | Blood Loss (mL) | Complications (Clavien-Dindo) |

Follow-Up (Months) |

Recurrence Rate | Hernia Side(Left–L/Right–R/Bilateral–B) | Average BMI (kg/m2) | Hospital Stay (Days) | Years of Surgeries—Time Frame |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finley et al. (2007) [10] |

University of California-Irvine (USA) |

533 | 49 | Mesh | +10 over RARP |

N/A | None | 15.3 | 2% | 31 L 9 R |

N/A | N/A | 2002–2006 |

| Joshi et al. (2010) [11] |

North Shore University Hospital, NY (USA) |

4 | 6 | Mesh | +24 over RARP |

N/A | None | 34 | 0% | 2 L 2 R 2 B |

N/A | N/A | 2008–2009 |

| Kyle et al. (2010) [12] |

Royal Melbourne Hospital (Australia) |

700 | 37 | Mesh | +5–10 over RARP |

N/A | None | 29 | 2.7% | 18 L 14 R 5 B |

27.1 | 2 | 2005–2009 |

| Lee et al. (2013) [13] |

University of Iowa, Iowa (USA) |

1118 | 91 | Mesh | 185 | 170 | 1 recurrence, others not significant | 9–12 | 1.1% | 41 L 29 R 22 B |

27.5 | 1 | 2010–2012 |

| Mourmouris et al. (2016) [14] |

Acibadem Maslak Hospital, Istanbul (Turkey) |

1005 | 29 | Nonprosthetic | 147 | 175 | None | 32.1 | 0% | 7 L 14 R 8 B |

26.47 | 4,3 | 2013–2015 |

| Ludwig et al. (2016) [15] |

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (USA) |

71 | 11 | Mesh | 160 | 100 | Minor | 36 | 0% | 5 L 3 R 3 B |

27.0 | 2 | 2010–2014 |

| Rogers et al. (2017) [16] |

Florida Hospital, Celebration, FL (USA) |

1139 | 39 | Mesh transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) |

188 | 110.87 | 10.26% Minor | N/A | 0% | N/A | 26.8 | N/A | 2008–2015 |

| Atmaca et al. (2018) [17] |

Health Sciences University (Turkey) |

100 | 38 | Mesh | 160 | 50 | 7% (Minor) | 36.6 | 11% | 19 L 12 R 7 B |

N/A | N/A | 2014–2017 |

| Xia et al. (2018) [18] |

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (USA) |

198 | 25 | Mesh | 155 | 110 | None | 20 | 1.5% | 10 L 8 R 7 B |

27.3 | 2 | 2015–2017 |

| Bajpai et al. (2020) [19] |

Miami Cancer Institute (USA) |

104 | 35 | Mesh | 140 | 120 | None | 18 | 2% | 15 L 12 R 8 B |

27.5 | 2 | 2017–2019 |

| Bedir et al. (2021) [20] |

Erzurum Regional Training Hospital (Turkey) |

26 | 32 | Mesh | 192.5 | 100 | None | 18 | 3.8% | 10 L 11 R 5 B |

28.0 | 6 | 2018–2020 |

| Drobot et al. (2024) |

Multidisciplinary Hospital in Warsaw-Miedzylesie (Poland) |

241 | 3 | Mesh transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) | 221.6 151.6 mean RARP console time 43.3 mean IHR console time |

358,3 | Minor (Grade I–II) | 15–35 | 0% | 2 B 1 B |

N/A | 7 (4 postoperative days) |

2021–2024 |

| Author | Year | Institution | Country | Procedure | Condition | Discharge Day | Surgery Time | Console Time | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tan, G.Y. et al. [21] | 2012 | Weill Cornell Medical College | USA | Robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy and cystolithotomy | Prostate cancer with bladder stones | Postoperative day 1 discharge | N/A | N/A | None |

| Macedo, F.I.B. et al. [22] | 2013 | James Buchanan Brady Foundation | USA | Robotic removal of eroded vaginal mesh into the bladder | Vaginal mesh erosion with bladder involvement | N/A | N/A | N/A | None |

| Sappal, S. et al. [23] | 2016 | Virginia Commonwealth University | USA | Robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy and adrenalectomy | Intrarenal adrenocortical adenoma | Postoperative day 1 discharge | 2 h 10 min | 14 min | None |

| Gul, Z.G. et al. [24] | 2020 | Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai | USA | Robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy and adrenalectomy | Pheochromocytoma | Postoperative day 1 discharge | N/A | N/A | None |

| Olive, E.J. et al. [25] | 2024 | Mayo Clinic | USA | Robotic-assisted intravesical mesh excision | Intravesical mesh erosion with stone | Postoperative day 1 discharge | N/A | N/A | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).