1. Introduction

The modern concept of minimal residual disease (MRD) stems from centuries of medical observations. In the East, traditional Chinese medicine texts like "

Huangdi Neijing", place emphasis on forces within the body that manifest disease [

1]. As such, disease can be "dormant" or "hidden" only to resurface years later. In the West, building on the work of Avicenna (

The Canon of Medicine) and Girolamo Fracastoro (

Miasmas and Contagions), the idea that relapse is caused by "seeds of disease" that are "left behind" was the center theme of medical discourses at the beginning of the 20th century [

2,

3]. In the last century, with the advent of microscopy and advanced pathology, the distinction between clinical and pathological remissions became better defined for various diseases. In leukemia, physicians observed that patients continue to relapse after achieving what appeared to be a morphological complete remission (CR) [

4]. This led to the hypothesis that some form of the disease persisted beyond detection. With an increasing understanding of cancer biology, the idea solidified that leukemias, even when in remission by clinical and morphological standards, might still harbor residual malignant cells capable of driving relapse. The word "minimal" in MRD emphasizes the latency and lack of detectability, encapsulating the understanding that even a minimal amount of disease if left untreated, could result in relapse. The advances in molecular biology and the development of sensitive detection techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the 1980s and 1990s shifted the focus from a purely philosophical idea of “minimal” residual disease to a measurable entity, hence the transition to the term "measurable” residual disease [

5].

2. Current Treatment Paradigms in Acute Leukemia and the Role of MRD

2.1. Traditional Approaches to Determine Treatment Response in Acute Leukemia

In acute leukemias, the primary goal of induction therapy is to reduce the total leukemic cell population below the cytologically detectable level of approximately 10

9 cells. Complete remission (CR) is defined as the absence of circulating blasts in the peripheral blood (PB), no signs of extramedullary disease, and less than 5% blasts in the bone marrow (BM) in patients who have hematologic recovery (absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1.0 x10

9/L and the platelet count ≥ 100 x 10

9/L) [

6]. Traditionally, cytotoxic chemotherapy such as “7+3” for AML or “4-drug induction” for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) regimens was used to decrease the tumor burden and achieve CR [

6,

7]. These drugs target actively dividing cells and thus, preferentially eliminate leukemia compared to the more quiescent normal hematopoietic stem cells. At the time of count recovery, typically 4-6 weeks from the initiation of therapy, using this strategy, 60-80% of patients with AML and 80-90% of those with ALL go on to achieve CR [

6,

8].

2.2. MRD as a Measure to Predict Treatment Response

Given the heterogeneity of the disease on one hand and the “one size fits all” of the induction regimens, intermediate assessments of response were traditionally used to predict outcomes. To this end, day 8 PB morphology with day 14 BM biopsy in AML, and day 15 BM flow cytometry in ALL are indicative of the likelihood of achieving CR and may be used to intensify treatment or direct post-induction, consolidation therapy [

9,

10].

Upfront incorporation of novel, targeted agents in induction regimens (i.e. venetoclax, gemtuzumab ozogamicin, and FLT3-inhibitors in AML as well as blinatumomab and BCR::ABL1 inhibitors in ALL), however, call into question the utility of some of those mid-treatment assessments as predictors of overall outcomes. For instance, the use of venetoclax in combination with “5+2” cytarabine and anthracycline chemotherapy leads to MRD-negativity in mid-treatment assessment in almost 95% of patients, and yet 30% of them will relapse within one year [

11].

2.3. Assessing MRD in CR

Patients who achieve CR remain at high risk of disease recurrence, with 60-80% of them experiencing clinical relapse. Therefore, CR cannot discriminate between patients who will experience relapse from those who are cured. Traditionally, molecular and clinical features of the disease at diagnosis or during treatment were used to identify patients in CR who are most likely to relapse and thus, lead to intensification of consolidation regimens. The development of highly sensitive methods like multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC), PCR, and more recently, next-generation sequencing (NGS), allowed clinicians to detect MRD in patients who achieved CR. Efforts are now underway to incorporate the presence or absence of MRD in the clinical decision-making regarding the management of acute leukemia in CR.

Perhaps the method with the most track record is the use of MFC to detect leukemia-associated immunophenotype (LAIP) in patients with ALL. The high sensitivity of the method (10

-4 to 10

-5) combined with decades of retrospective and prospective clinical data made MRD detection by MFC a cornerstone of the management of these patients with implications for risk stratification, prognosis, and treatment modifications [

12]. Nevertheless, data from the use of MFC to detect MRD in ALL highlight several aspects that transcend the type of acute leukemia or the method used to detect MRD. First, the timing used to perform the test plays an important role in the predictive value. Second, the correlation between MRD positivity and relapse is not perfect because only a fraction of those patients who are MRD-positive go on to experience relapse [

13].

When it comes to AML, unfortunately, the value of MRD is not as well established. This may be due to, at least in part, the lack of a “standard” LAIP that can easily be identified by MFC. Molecular, PCR-based methods have the sensitivity and specificity to play an important role as tools to detect and quantify MRD. In ALL, the use of molecular assays to detect leukemia-specific immunoglobulin chain rearrangement is beginning to position itself as an alternative to MFC [

14]. In myeloid malignancies, PCR-based methods to detect MRD have a longer track record. This is best exemplified by the use of quantitative PCR (qPCR) to detect BCR::ABL1 transcripts in patients with CML. The method has been standardized and an international scale is currently used to predict levels of response to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and inform prognosis and treatment decisions [

15]. Although in AML multiple somatic mutations can be detected by PCR, the use of this method to identify MRD and inform treatment decisions is rather limited. Detection of NPM1 mutations and more recently FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) are perhaps the most advanced MRD assays in their clinical development. These two mutations cover only a fraction of patients with AML and their prognostic implications are still waiting to be fully validated. However, virtually all patients with AML carry some somatic mutations that can be detected by NGS. The use of NGS at diagnosis to guide management of AML and inform prognosis is becoming routine given the easy access to the method and the relatively low costs. Initially, the sensitivity of NGS was rather low (10

-2) and thus not amenable to use as an MRD method. Nevertheless, NGS pipelines that have improved sensitivity into the 10

-5/10

-6 and beyond are currently under development and would make NGS a truly remarkable MRD tool [

16,

17]. If this becomes the case, new challenges will need to be overcome before such approaches will have wide clinical applicability. For example, most somatic mutations present in AML and used to assess MRD by NGS are also found in non-AML conditions such as clonal hematopoiesis (CH) or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) (

Table 1). Thus, one needs to distinguish between residual somatic mutations (such as those found in clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential – CHIP) and residual leukemia cells.

2.4. MRD-Directed Therapies

Given the strong correlation between MRD-positivity and increased risk of relapse, achieving MRD-negative CR, where no residual disease is detectable even with current sensitive methods, has become a key objective, as it is associated with a more favorable prognosis. In fact, the importance of MRD has grown so significantly that it is used to guide therapeutic decisions in many treatment protocols and clinical trials. Achieving MRD-negative status can lead to de-escalation of therapy in some cases, reducing potential toxicities, while MRD-positivity might indicate the need for more aggressive or alternative therapies. To this end, MRD-directed therapy with blinatumomab in patients with ALL significantly decreased the rate of relapse of these patients [

18]. Interestingly, however, a recent study points out that giving blinatumomab consolidation even for MRD-negative patients increases relapse-free and overall survival (95% 3-year overall survival in the blinatumomab-chemotherapy arm versus 70% in the chemotherapy-only arm) [

19]. These findings highlight the imperfect overlap between the presence of MRD and clinical relapse.

In AML there is a lack of prospective MRD-directed clinical trials. Data from a retrospective analysis of registry databases, as well as from previously randomized prospective trials clearly show that detection of somatic mutations via NGS at the time of transplant correlates with an increased risk of relapse [

20,

21]. More so, this data suggests that perhaps more intensive conditioning regimens may erase the higher relapse rates in patients with MRD-positivity [

20,

21]. In clinical practice, MRD detection in AML could lead to either relapse (70%) or cure (25-30%), however, it is prudent to be aware that the absolute quantifiable level of disease is not the sole determinant of patient outcomes. The biology of the disease, and other clinical factors modify the risk associated with MRD-test results. Recent data clearly highlight the need and utility of MRD assessment in AML. For instance, data extrapolated from the phase 3 ADMIRAL trial (NCT02421939) comparing gilteritinib versus chemotherapy for relapsed AML patients showed significant superiority of gilteritinib maintenance after allogeneic transplantation [

22]. Subsequent, randomized clinical studies, however, reported that post-transplant gilteritinib is beneficial in MRD-positivity only, the progression-free and overall survival advantage being lost in MRD-negative patients [

23]. That being said, in the absence of randomized, MRD-directed clinical trials, the value of clinical observations should be interpreted with a healthy dose of academic skepticism.

3. Lessons Learned from APL

The history of APL is a one-of-a-kind adventure that has transformed the most aggressive form of leukemia into the most treatable. APL is a subtype of AML with distinct biological, molecular, and clinical characteristics [

24]. APL was historically considered a “single gene disease” since its diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment were centered around a balanced reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 15 and 17, t(15;17)(q24;q21) which creates the PML-RARα fusion transcript. This product leads to the repression of both RARα and non-RARα target genes as well as the disruption of PML nuclear bodies, which dampens p53 signaling, prevents senescence, and drives perpetual proliferation and the suppression of terminal differentiation [

25]. The actual mutational profile is likely more intricate and alterations in FLT3, WT1, NRAS, or KRAS are commonly found in these patients [

26]. Initially, it was believed that additional somatic mutations have no influence on the clinical treatment of APL patients. Emerging data, however, suggest that mutations such as FLT3 may in fact track with less favorable prognosis including increased risk of relapse, even in the modern era, and particularly in those patients that have high mutational burden [

27].

Over the last half-century, the management of APL has seen two transformative interventions that effectively created new “eras”. The first game-changer intervention was the introduction of retinoids (especially all-trans retinoic acid - ATRA) in the early 1980’s. This coincided and was catalyzed by the use of PCR to detect PML-RARα in patients with APL. The second major shift started in the early 2000s with the use of arsenic trioxide (ATO) in the upfront management of APL. This led to the success of current chemotherapy-free regimens (ATRA plus ATO) and the unprecedented outcomes in this disease.

3.1. Pre-ATRA Era: Eliminating MRD, More Is Not Always Better

In the pre-ATRA era, patients with M3-AML (largely but not perfectly overlapping with APL) had superior outcomes compared to those with non-M3 AML, with CR rates of around 70% vs. 50% in non-M3 AML and median overall survival (OS) of almost 10 years vs. 6 months in non-M3 AML (data from SWOG trials between 1982-1986) [

28,

29,

30]. These studies established the role of high-dose anthracycline in eliminating MRD (as measured by risk of relapse). Namely, of the patients that achieved CR using 180-210 mg/m2 of daunorubicin, only 10% experienced relapse and another 10% died in remission. On the other hand, of patients that achieved remission using 135 mg/m2 of daunorubicin, 70% experienced relapse, and an additional 10% died in remission. Thus, the upfront use of high-dose daunorubicin became the standard of care in APL and catalyzed further dose intensification trials to eliminate MRD and prevent relapse.

SWOG trials between 1986 and 1991 reported that dose intensification with cytarabine improved median overall survival in non-M3 AML to about 12 months. High-dose cytarabine, however, compared to trials from 1982-1986 resulted in worse outcomes for APL patients both in terms of CR rates (47%) as well as median overall survival (13 months), and 30% of these patients still relapsed [

31]. Interestingly, the choice of post-remission therapy in these trials ranging from no treatment to high-dose cytarabine to allogeneic bone marrow transplant had no positive effect on OS [

31]. In light of this experience, one conclusion that should transcend eras is that intensification of treatment in order to eliminate MRD should be balanced against treatment toxicities. The net benefit of such interventions can only be deduced from the results of MRD-informed, randomized, controlled clinical trials.

3.2. The ATRA-Era: From Minimal to Measurable Residual Disease

Catalyzed by the identification of t(15;17) (q24;q21) in virtually all patients with APL in the 1970s and the mapping of RARα to q21 band of chromosome 17, the use of retinoids in the management of this disease marked a new approach to the treatment of acute leukemias in general [

32]. Instead of using cytotoxic therapy to kill leukemia cells, pharmacologic levels of retinoids overcome the differentiation block imposed by PML-RARα and allow malignant promyelocytes to mature into polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs). These neutrophils die naturally. The mechanism of action of ATRA is multifaceted and relies on transcriptional activation of differentiation-related genes. ATRA may also activate autophagy leading to the early death of malignant promyelocytes [

33].

Since one promyelocyte can generate 30-50 PMNs, there is an initial increase in leukocytes in response to retinoids. This phenomenon and the associated clinical signs observed during treatment with retinoids in APL were initially named retinoid syndrome and subsequently differentiation syndrome. Nowadays, differentiation syndrome is a common occurrence during treatment with small molecule inhibitors that target mutations commonly found in AML such as FLT3 inhibitors, IDH inhibitors, and menin inhibitors [

34].

The initial use of single-agent retinoids, particularly ATRA in many case reports, showed impressive CR rates, at times as high as 100%. Huang et al. presented their experience treating 24 patients with APL with 45-100 mg/m2 of ATRA. “All patients achieved complete remission without developing bone marrow hypoplasia” [

35]. Unfortunately, almost all of the patients who achieved CR with single-agent ATRA relapsed despite continuous therapy. However, the use of intravenous liposomal ATRA prevented relapse in 30% of patients [

36]. Thus, the pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of ATRA play an important role in eliminating MRD.

The aforementioned trials performed bone marrow biopsies on patients at the time of CR and by using reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) showed the presence of the PML-RARα fusion transcripts [

37]. Similarly, in patients treated with ATRA plus chemotherapy, detection of PML-RARα by RT-PCR was highly predictive of relapse [

38]. Thus, in the early 1990s, MRD changed its meaning from minimal to measurable residual disease in APL. RT-PCR positivity at the end of induction was highly predictive for relapse and predated morphologic relapse by 1-4 months.

The success of ATRA plus chemotherapy in APL was confirmed by multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trials carried out in Europe, the USA, and Japan [

39]. Molecular methods to detect PML-RARα (either PCR or RT-PCR) became an important readout for many clinical trials [

40,

41]. MRD-positivity had such a high positive predictive value that the term “molecular relapse” was developed to identify patients who became MRD positive and were thus, at impending risk of clinical relapse [

42,

43].

3.3. Arsenic Trioxide (ATO) as a Single Agent

The use of arsenic trioxide (ATO) in APL goes back to the early 1970s and the use of Ailin-1 by a Chinese research group from Harbin University [

44]. Though the mechanisms of action were not initially known, ATO was increasingly used as salvage therapy for patients with APL relapsing after ATRA-based therapy. When comparing the two agents, single-agent ATO had inferior CR rates but the 3-year rate of relapse was only 25% compared to nearly 100% in single-agent ATRA [

45]. Thus, perhaps ATRA is particularly effective in controlling early mortality and differentiating the bulk of the APL cells while ATO is superior in eliminating MRD.

Over the last decades, the mechanisms of action of ATO have become clearer [

24]. Arsenic has a strong affinity for the cysteine residues in PML and can directly bind to multiple domains of the gene. ATO promotes the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which leads to the formation of disulfide bonds between PML-RARα fusion molecules, called nuclear matrix-associated nuclear bodies. The nuclear bodies get SUMOylated and ubiquitinated with the proteasome complex being eventually degraded [

46]. Molecular evidence of ATO targeting PML is supported by the observation that point mutations in PML (C213R, A216V, L217F, and L218P) emerge during treatment with ATO and are associated with clinical resistance in patients with APL [

47].

Another described mechanism of action of ATO in APL is promoting both apoptosis and autophagy [

48,

49]. Apoptosis may be caused either through activation of caspase cascade or by upregulation of p53 but other cell death mechanisms have also been linked to ATO in the literature [

50].

3.4. ATO and Chemo-Free Regimens

Since ATRA and ATO bind different parts of the PML-RARα protein, there was early evidence for molecular synergism between these agents which provided the rationale for combining them in clinical trials. Clinical trials using ATRA/ATO combinations revolutionized APL therapy since almost all patients achieved CR and the rates of molecular relapse are as low as 0% [

51,

52]. Since single-arm trials showed the superiority of ATRA/ATO, this served as the rationale for designing randomized clinical trials comparing ATRA/ATO with ATRA and chemotherapy. These trials showed clear superiority of ATRA/ATO to achieving CR as well as preventing relapse and thus eliminating MRD [

53].

3.5. A Final Lesson from APL: Assessing MRD at the End of Consolidation

A high percentage of APL patients show long-term remission and no relapse even though they are MRD-positive after induction. Trials studying the clinical impact of ATRA/chemotherapy used MRD testing after consolidation to predict outcomes. MRD positivity after consolidation invariably characterized patients at high risk of relapse [

54]. Subsequently, in randomized clinical trials comparing ATRA/ATO with ATRA/chemotherapy, the kinetics of MRD were not significantly different between the groups [

51,

53].

Measurable RT-PCR transcripts continue to decline during consolidation in both arms from about 3-log post induction to close to 6-logs post-consolidation, and yet the rate of relapse was higher in patients treated with ATRA/chemotherapy [

53]. Thus, most recent guidelines recommend MRD testing only at the end of consolidation for APL. However, for non-APL AML, MRD testing is recommended both during induction (after 2 cycles) and post-consolidation [

55]. MRD is surely indispensable for the optimal management of AML patients. However, there is a significant difference between MRD-positivity and relapse, both in APL and non-APL AML patients.

The important lessons taught by APL and discussed in this section are summarized in

Table 2.

4. Does the BM Microenvironment Play a Role in MRD?

4.1. Leukemia Stem Cells as MRD

First postulated by Fialkow et al. in the 1960s in CML, the concept of leukemia stem cell (LSC) enjoyed renewed interest with the identification of a CD34

+CD38

- population of cells present in patients with AML and able to recapitulate the disease in xenograft models [

56,

57]. Since LSCs appear to have an immunophenotype similar to the normal hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), there was a frenzy to identify markers that distinguish these populations in general and within individual patients. Depending on the genetic subtype, LSCs can now be identified by their differential expression of CD34, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), CD123, CD44, CD96, CLL-1, CD47, and GPR56 [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66].

Most recently, using single-cell transcriptomics and cytometry by time of flight, we are now gaining insight into not only LSCs but even transition states between normal HSPCs and LSCs [

67,

68]. Functionally, LSCs and HSPCs share many of their properties including cell cycle quiescence and self-renewal making them prime candidates for the persistence of MRD [

69]. For patients with core binding factor AML for instance, LSCs characterized as CD34

+CD38

-ALDH

int represent a minute fraction of the tumor at diagnosis but are enriched in CR and their presence predicts disease relapse [

70]. Furthermore, the immunophenotype of LSCs defines the biology of leukemias and correlates with prognosis. Immature phenotypes, such as CD34-positivity in AML and ALL are associated with worse outcomes [

70,

71,

72].

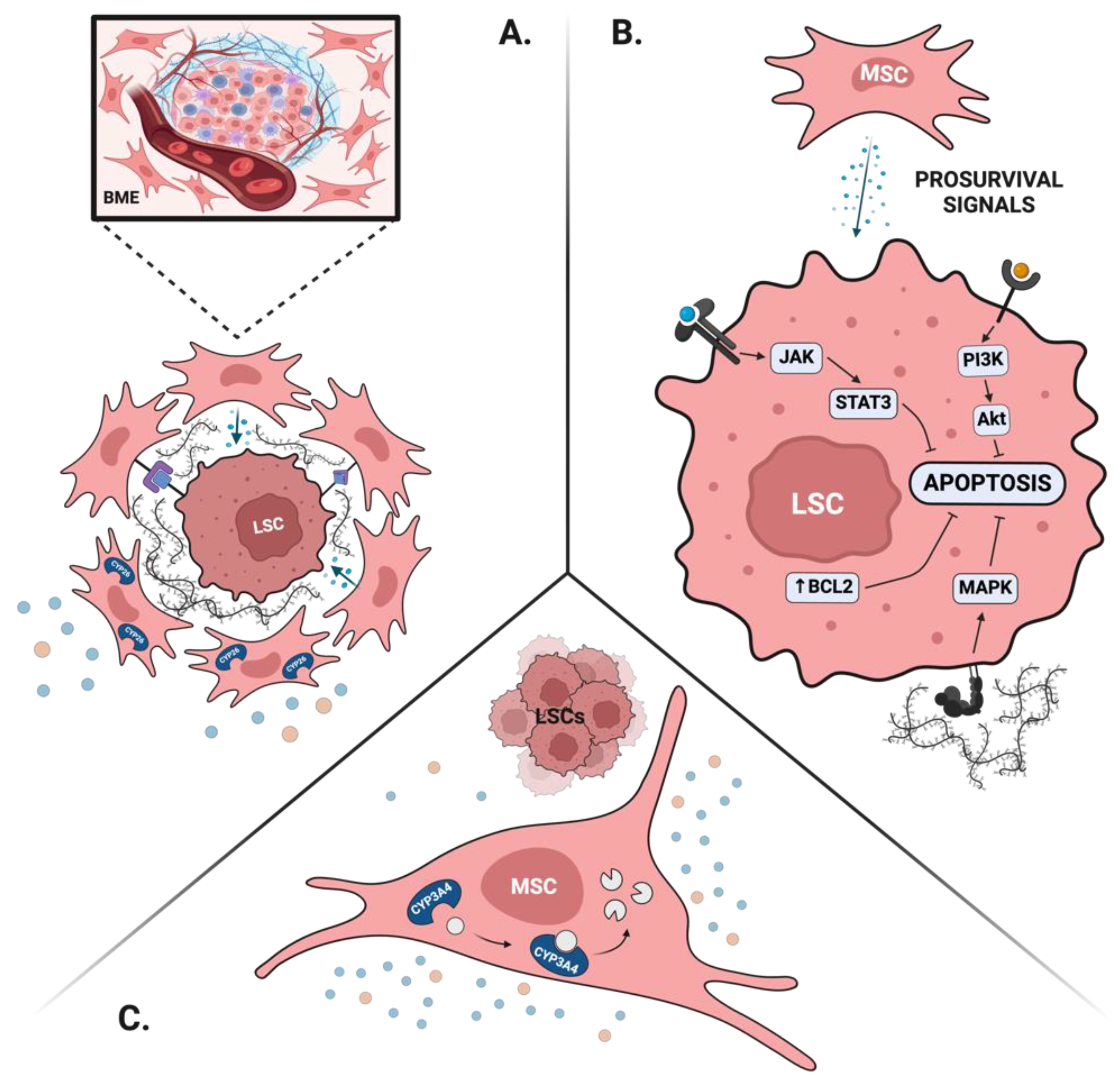

4.2. BME Protects Leukemia Stem Cells and Leads to MRD

The BM is a highly complex tissue in which cell extrinsic signals provided by various microenvironments (BME) modulate hematopoiesis to maintain blood homeostasis. LSCs and normal HSPCs rely on similar BME signals to maintain their self-renewal, dormancy, and survival and thus, may directly compete to occupy various BM niches [

58,

73,

74]. Multiple BME-dependent mechanisms are being proposed to contribute to the persistence of MRD.

4.2.1. BME Maintains LSCs Properties

Both normal HSPCs and LSCs rely on intimate interaction with the BME to maintain their stem cell properties. For instance, direct cell-cell interactions between mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) and LSCs through the CXCL12-CXCR4 and VCAM-1/VLA-4 promote stem cell quiescence and thus may contribute to drug resistance and persistence of MRD [

75,

76,

77]. More so, prolonged exposure to physiological levels of retinoids results in rapid loss of HSCs as well as LSCs during ex vivo culture [

78,

79]. Mesenchymal stromal cells, via expression of CYP26, a retinoid-inactivating enzyme, protect LSCs from differentiation and maintain their properties [

78,

80].

4.2.2. BME Provides Prosurvival Signals

Modern therapeutic approaches in AML rely on the use of targeted therapy to control disease burden. While this approach has a safe side effect profile, it also creates biological opportunities to bypass this therapeutic target and contribute to drug resistance. A unique form of drug resistance takes place in the BM niche, where signals from the surrounding stroma provide prosurvival mechanisms otherwise unavailable for circulating disease [

74,

79]. To this end, activation of RAS/MAPK or JAK/STAT pathway by cytokines secreted by BME can allow survival of FLT3-mutated AML blasts treated with FLT3-inhibitors when they are hosted in the BM niche [

79]. Similarly, AML blasts in the BM upregulate antiapoptotic proteins, such as BCL-2, and are thus relatively resistant to venetoclax [

81]. Furthermore, mitochondria transfer between the MSCs and the AML blasts via tunneling nanotubules mitigates resistance to mitochondrial stress and provides leukemic cells a survival advantage in the BME [

82].

4.2.3. BME Creates Favorable Drug Pharmacokinetics

Mesenchymal stromal cells express a large repertoire of drug-metabolizing enzymes, at levels comparable to those found in hepatocytes [

83]. Of those, CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 metabolize the vast majority of traditional and novel therapies used in AML. CYP3A4 activity in particular was shown to play an important role in protecting AML cells from traditional chemotherapy and targeted agents such as FLT3 inhibitors [

84]. Similarly, stromal-dependent CYP26 activity protects APL and non-APL blasts from pharmacological levels of ATRA and thus, may contribute to the persistence of MRD in patients treated with single-agent ATRA [

79,

80].

The relation between the BME and the malignant cells is complex and multidirectional. Not only does the BME protect the leukemia blasts but malignant cells also reorganize their surrounding microenvironment. Blasts, for instance, transform MSCs into chemoprotective islands in ALL and AML [

85,

86]. More so, initial treatments can change the molecular properties of the BME. As such, treatment with ATRA in APL upregulates stromal CYP26, and chemotherapy results in higher levels of drug-metabolizing enzymes in BM MSCs [

80,

87].

4.3. Targeting the BME to Eliminate MRD

Given the close relationship between MRD, LSCs, and BME, efforts are underway to target the BME in order to eliminate LSCs and thus, prevent disease relapse. Initial studies were centered around mobilizing LSCs from their niche by targeting either the CXCR4-CXCL12 axis or the integrins and selectins. While these strategies were able to mobilize LSCs from the protective microenvironment of the bone marrow, their combination with chemotherapy did not result in significant clinical benefit in AML and ALL [

88,

89]. It may be that the potential benefit of eliminating MRD was offset by the added toxicities. In addition, perhaps some of the cell-intrinsic, epigenetic properties that endow drug resistance to malignant stem cells have a level of inertia even after LSCs are mobilized from the niche [

90]. Thus, further studies are needed to find the optimal timing of LSCs mobilization and chemotherapeutic targeting. Perhaps, combining LSCs mobilizing approaches with targeted therapies that have more favorable side effect profiles such as FLT3-, IDH- or menin-inhibitors hold the key to preventing disease relapse as none of those treatments are curative as a single agent.

In addition to mobilizing LSCs from their BM niche in order to decrease MRD burden, disrupting the malignant niche using antiangiogenic agents (VEGF-inhibitors or anti-VEGF antibodies) or immunomodulators (lenalidomide, pomalidomide) showed promising results in phase II clinical trials [

74]. More so, recent studies showed that hypomethylating agents and epigenetic regulators such as azacytidine may reverse immunosuppression caused by LSCs in the BM and may help restore normal function of the BM T-cells microenvironment [

91]. Similarly, robust immune reconstitution of the BM microenvironment plays an important role in the persistence of MRD in ALL and thus has a profound impact on the long-term remission-free survival of these patients [

92].

Lastly, drug formulations that have improved pharmacokinetic properties such as liposomal cytarabine plus anthracycline (CPX-351) may bypass the biochemical barrier created by stromal drug metabolizing enzymes and thus eliminate LSCs in their niche. To this end, treatment with CPX-351 resulted in a high rate of MRD-negative CR which may explain the superior survival compared to the traditional “7+3” [

93]. Similarly, liposomal formulations of ATRA have greater efficiency in preventing relapse compared to oral ATRA [

79]. In addition, synthetic retinoids that are resistant to CYP26-mediated degradation, such as tamibarotene (Sy1425) or IRX195183, were also able to bypass stromal biochemical barrier and differentiate APL and non-APL leukemia cells in preclinical and clinical settings [

80,

94,

95]. In APL, tamibarotene had similar CR rates to ATRA but had significantly lower rates of relapse (50% versus 100%) highlighting the importance of adequate local retinoid pharmacokinetics in the control of MRD [

96].

The contribution of the BME to MRD is summarized in

Figure 1.

5. Conclusion

We have made remarkable strides in the management of APL, yet we often fail to rapidly translate these advancements to other forms of leukemia. It was once thought that APL is a genetically simple disease affecting younger demographics and therefore, insights from APL biology could not be applied to other leukemias. However, we now know that APL is genetically diverse and that neither additional genetic lesions nor extremes of age significantly impact outcomes. In fact, the most crucial determinant of outcome is treatment with ATRA.

It was also believed that the success seen with the addition of ATRA in APL could not be replicated in other AML subtypes. Yet, similar to ATRA in APL, we now see that targeting driver mutations in other AMLs differentiates malignant blasts and leads to differentiation syndrome. We also know that single-agent ATRA is not effective in eliminating MRD in APL and targeting the microenvironment is essential to achieving a cure. How long will it take for us to apply these lessons to non-APL AML?

Albert Einstein is often quoted as saying, “ Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results”. In the same way, it’s madness to make breakthroughs in APL treatment without applying those lessons to other leukemias, yet still expect rapid progress."

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, GG; methodology, DK, PT, GG; writing—original draft preparation, DK, PT, GG; writing—review and editing, DK, PT, GG; visualization, DK; supervision, GG; funding acquisition, G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

DK was funded by a research scholarship of the Romanian Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitalization (Bursa Henri Coandă).

Conflicts of Interest

GG received research grants from Abbvie Inc. and Menarini Ricerche. GG is an advisor for Syros Inc and for Kinomica Inc. GG holds a patent for the use of IRX195183. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen. The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine* by Ilza Veith. University of California Press. 1966;

- Avicenna 980-1037. A treatise on the Canon of medicine of Avicenna, incorporating a translation of the first book [Internet]. London : Luzac & co., 1930.; 1930. Available from: https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999714469602121.

- Nutton V. The Reception of Fracastoro’s Theory of Contagion: The Seed That Fell among Thorns? Osiris. 1990;6:196–234.

- Ossenkoppele G, Schuurhuis GJ. MRD in AML: time for redefinition of CR? Blood. 2013 Mar 21;121(12):2166–8.

- Bradstock KF, Janossy G, Tidman N, Papageorgiou ES, Prentice HG, Willoughby M, et al. Immunological monitoring of residual disease in treated thymic acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Leuk Res. 1981 Jan;5(4–5):301–9. [CrossRef]

- Döhner H, Wei AH, Appelbaum FR, Craddock C, DiNardo CD, Dombret H, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood. 2022 Sep 22;140(12):1345–77. [CrossRef]

- Gökbuget N, Boissel N, Chiaretti S, Dombret H, Doubek M, Fielding A, et al. Management of ALL in adults: 2024 ELN recommendations from a European expert panel. Blood. 2024 May 9;143(19):1903–30. [CrossRef]

- Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Children. Longo DL, editor. N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 15;373(16):1541–52.

- Estey E, Döhner H. Acute myeloid leukaemia. The Lancet. 2006 Nov;368(9550):1894–907.

- Pui CH, Yang JJ, Hunger SP, Pieters R, Schrappe M, Biondi A, et al. Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Progress Through Collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Sep 20;33(27):2938–48. [CrossRef]

- Pan J, Wang H, Mao L, Lou Y, Ren Y, Ye X, et al. Venetoclax Plus ‘2 + 5‘ Modified Intensive Chemotherapy with Daunorubicin and Cytarabine in Fit Elderly Patients with Untreated De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukaemia: A Single-Centre Retrospective Analysis. Blood. 2023 Nov 2;142(Supplement 1):2912–2912.

- Brüggemann M, Schrauder A, Raff T, Pfeifer H, Dworzak M, Ottmann OG, et al. Standardized MRD quantification in European ALL trials: Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on MRD assessment in Kiel, Germany, 18–20 September 2008. Leukemia. 2010 Mar;24(3):521–35. [CrossRef]

- Pui CH, Pei D, Raimondi SC, Coustan-Smith E, Jeha S, Cheng C, et al. Clinical impact of minimal residual disease in children with different subtypes of acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with Response-Adapted therapy. Leukemia. 2017 Feb;31(2):333–9. [CrossRef]

- Shahkarami S, Mehrasa R, Younesian S, Yaghmaie M, Chahardouli B, Vaezi M, et al. Minimal residual disease (MRD) detection using rearrangement of immunoglobulin/T cell receptor genes in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Ann Hematol. 2018 Apr;97(4):585–95. [CrossRef]

- Hughes TP, Ross DM. Moving treatment-free remission into mainstream clinical practice in CML. Blood. 2016 Jul 7;128(1):17–23. [CrossRef]

- Tsai CH, Tang JL, Tien FM, Kuo YY, Wu DC, Lin CC, et al. Clinical implications of sequential MRD monitoring by NGS at 2 time points after chemotherapy in patients with AML. Blood Adv. 2021 May 25;5(10):2456–66. [CrossRef]

- Schuurhuis GJ, Heuser M, Freeman S, Béné MC, Buccisano F, Cloos J, et al. Minimal/measurable residual disease in AML: a consensus document from the European LeukemiaNet MRD Working Party. Blood. 2018 Mar 22;131(12):1275–91. [CrossRef]

- Gökbuget N, Dombret H, Bonifacio M, Reichle A, Graux C, Faul C, et al. Blinatumomab for minimal residual disease in adults with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2018 Apr 5;131(14):1522–31. [CrossRef]

- Litzow MR, Sun Z, Mattison RJ, Paietta EM, Roberts KG, Zhang Y, et al. Blinatumomab for MRD-Negative Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Adults. N Engl J Med. 2024 Jul 25;391(4):320–33. [CrossRef]

- Boyiadzis M, Zhang MJ, Chen K, Abdel-Azim H, Abid MB, Aljurf M, et al. Impact of pre-transplant induction and consolidation cycles on AML allogeneic transplant outcomes: a CIBMTR analysis in 3113 AML patients. Leukemia. 2023 May;37(5):1006–17.

- Dillon LW, Gui G, Page KM, Ravindra N, Wong ZC, Andrew G, et al. DNA Sequencing to Detect Residual Disease in Adults With Acute Myeloid Leukemia Prior to Hematopoietic Cell Transplant. JAMA. 2023 Mar 7;329(9):745. [CrossRef]

- Perl AE, Larson RA, Podoltsev NA, Strickland S, Wang ES, Atallah E, et al. Outcomes in Patients with FLT3-Mutated Relapsed/ Refractory Acute Myelogenous Leukemia Who Underwent Transplantation in the Phase 3 ADMIRAL Trial of Gilteritinib versus Salvage Chemotherapy. Transplant Cell Ther. 2023 Apr;29(4):265.e1-265.e10.

- Levis MJ, Hamadani M, Logan B, Jones RJ, Singh AK, Litzow M, et al. Gilteritinib as Post-Transplant Maintenance for AML With Internal Tandem Duplication Mutation of FLT3. J Clin Oncol. 2024 May 20;42(15):1766–75. [CrossRef]

- Bercier P, De Thé H. History of Developing Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Treatment and Role of Promyelocytic Leukemia Bodies. Cancers. 2024 Mar 29;16(7):1351.

- Jimenez JJ, Chale RS, Abad AC, Schally AV. Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): a review of the literature. Oncotarget. 2020 Mar 17;11(11):992–1003. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Wang J, Xu H, Zhao S, Wang L, Huang J, et al. Prognosis influence of additional chromosome abnormalities in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia with t(15;17)(q24;q21). Hematology. 2024 Dec 31;29(1):2293513.

- Li AY, Kashanian SM, Hambley BC, Zacholski K, Duong VH, El Chaer F, et al. FLT3-ITD Allelic Burden and Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Risk Stratification. Biology. 2021 Mar 21;10(3):243. [CrossRef]

- Swirsky DM, Bastos MD, Parish SE, Rees JKH, Hayhoe FGJ. Features affecting outcome during remission induction of acute myeloid leukaemia in 619 adult patients. Br J Haematol. 1986 Nov;64(3):435–53. [CrossRef]

- Mertelsmann R, Tzvi Thaler H, To L, Gee TS, McKenzie S, Schauer P, et al. Morphological classification, response to therapy, and survival in 263 adult patients with acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1980 Nov;56(5):773–81.

- Morrison FS, Kopecky KJ, Head DR, Athens JW, Balcerzak SP, Gumbart C, et al. Late intensification with POMP chemotherapy prolongs survival in acute myelogenous leukemia--results of a Southwest Oncology Group study of rubidazone versus adriamycin for remission induction, prophylactic intrathecal therapy, late intensification, and levamisole maintenance. Leukemia. 1992 Jul;6(7):708–14.

- Head D, Kopecky KJ, Weick J, Files JC, Ryan D, Foucar K, et al. Effect of aggressive daunomycin therapy on survival in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 1995 Sep 1;86(5):1717–28. [CrossRef]

- Nagai Y, Ambinder AJ. The Promise of Retinoids in the Treatment of Cancer: Neither Burnt Out Nor Fading Away. Cancers. 2023 Jul 8;15(14):3535. [CrossRef]

- Liang C, Qiao G, Liu Y, Tian L, Hui N, Li J, et al. Overview of all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) and its analogues: Structures, activities, and mechanisms in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Eur J Med Chem. 2021 Aug;220:113451. [CrossRef]

- Woods AC, Norsworthy KJ. Differentiation Syndrome in Acute Leukemia: APL and Beyond. Cancers. 2023 Sep 28;15(19):4767. [CrossRef]

- Huang ME, Ye YC, Chen SR, Chai JR, Lu JX, Zhoa L, et al. Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 1988 Aug;72(2):567–72.

- Tsimberidou AM, Tirado-Gomez M, Andreeff M, O’Brien S, Kantarjian H, Keating M, et al. Single-agent liposomal all-trans retinoic acid can cure some patients with untreated acute promyelocytic leukemia: an update of The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Series. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006 Jan;47(6):1062–8. [CrossRef]

- Miller WH, Kakizuka A, Frankel SR, Warrell RP, DeBlasio A, Levine K, et al. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction for the rearranged retinoic acid receptor alpha clarifies diagnosis and detects minimal residual disease in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Apr 1;89(7):2694–8.

- Lo Coco F, Diverio D, Pandolfi PP, Biondi A, Rossi V, Avvisati G, et al. Molecular evaluation of residual disease as a predictor of relapse in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Lancet Lond Engl. 1992 Dec 12;340(8833):1437–8.

- Wang ZY, Chen Z. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: from highly fatal to highly curable. Blood. 2008 Mar 1;111(5):2505–15. [CrossRef]

- Grimwade D, Howe K, Langabeer S, Burnett A, Goldstone A, Solomon E. Minimal residual disease detection in acute promyelocytic leukemia by reverse-transcriptase PCR: evaluation of PML-RAR alpha and RAR alpha-PML assessment in patients who ultimately relapse. Leukemia. 1996 Jan;10(1):61–6.

- Diverio D, Rossi V, Avvisati G, De Santis S, Pistilli A, Pane F, et al. Early detection of relapse by prospective reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction analysis of the PML/RARalpha fusion gene in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia enrolled in the GIMEMA-AIEOP multicenter “AIDA” trial. GIMEMA-AIEOP Multicenter “AIDA” Trial. Blood. 1998 Aug 1;92(3):784–9.

- Lo Coco F, Diverio D, Avvisati G, Petti MC, Meloni G, Pogliani EM, et al. Therapy of molecular relapse in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999 Oct 1;94(7):2225–9. [CrossRef]

- Grimwade D, Jovanovic JV, Hills RK, Nugent EA, Patel Y, Flora R, et al. Prospective minimal residual disease monitoring to predict relapse of acute promyelocytic leukemia and to direct pre-emptive arsenic trioxide therapy. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009 Aug 1;27(22):3650–8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang P, Wang SY, Hu LH. Studies on the clinical practice and mechanisms of 713 (As 2 O 3) in the treatment of 117 cases of APL. J. Harbin Med. Univ. 1995;29:243.

- Mathews V, George B, Lakshmi KM, Viswabandya A, Bajel A, Balasubramanian P, et al. Single-agent arsenic trioxide in the treatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia: durable remissions with minimal toxicity. Blood. 2006 Apr 1;107(7):2627–32. [CrossRef]

- Lallemand-Breitenbach V, Jeanne M, Benhenda S, Nasr R, Lei M, Peres L, et al. Arsenic degrades PML or PML–RARα through a SUMO-triggered RNF4/ubiquitin-mediated pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2008 May;10(5):547–55.

- Dubey S, Mishra N, Shelke R, Varma AK. Mutations at proximal cysteine residues in PML impair ATO binding by destabilizing the RBCC domain. FEBS J. 2024 Apr;291(7):1422–38. [CrossRef]

- Chen GQ, Shi XG, Tang W, Xiong SM, Zhu J, Cai X, et al. Use of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): I. As2O3 exerts dose-dependent dual effects on APL cells. Blood. 1997 May 1;89(9):3345–53.

- Goussetis DJ, Altman JK, Glaser H, McNeer JL, Tallman MS, Platanias LC. Autophagy Is a Critical Mechanism for the Induction of the Antileukemic Effects of Arsenic Trioxide. J Biol Chem. 2010 Sep;285(39):29989–97. [CrossRef]

- Yan M, Wang H, Wei R, Li W. Arsenic trioxide: applications, mechanisms of action, toxicity and rescue strategies to date. Arch Pharm Res. 2024 Mar;47(3):249–71. [CrossRef]

- Burnett AK, Russell NH, Hills RK, Bowen D, Kell J, Knapper S, et al. Arsenic trioxide and all-trans retinoic acid treatment for acute promyelocytic leukaemia in all risk groups (AML17): results of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015 Oct;16(13):1295–305. [CrossRef]

- Ravandi F, Estey E, Jones D, Faderl S, O’Brien S, Fiorentino J, et al. Effective treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans-retinoic acid, arsenic trioxide, and gemtuzumab ozogamicin. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009 Feb 1;27(4):504–10.

- Lo-Coco F, Avvisati G, Vignetti M, Thiede C, Orlando SM, Iacobelli S, et al. Retinoic Acid and Arsenic Trioxide for Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 11;369(2):111–21. [CrossRef]

- Sanz MA. Risk-adapted treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans-retinoic acid and anthracycline monochemotherapy: a multicenter study by the PETHEMA group. Blood. 2003 Oct 23;103(4):1237–43.

- Heuser M, Freeman SD, Ossenkoppele GJ, Buccisano F, Hourigan CS, Ngai LL, et al. 2021 Update on MRD in acute myeloid leukemia: a consensus document from the European LeukemiaNet MRD Working Party. Blood. 2021 Dec 30;138(26):2753–67. [CrossRef]

- Fialkow PJ, Gartler SM, Yoshida A. Clonal origin of chronic myelocytic leukemia in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1967 Oct;58(4):1468–71. [CrossRef]

- Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994 Feb;367(6464):645–8. [CrossRef]

- Boyd AL, Campbell CJV, Hopkins CI, Fiebig-Comyn A, Russell J, Ulemek J, et al. Niche displacement of human leukemic stem cells uniquely allows their competitive replacement with healthy HSPCs. J Exp Med. 2014 Sep 22;211(10):1925–35. [CrossRef]

- Gerber JM, Smith BD, Ngwang B, Zhang H, Vala MS, Morsberger L, et al. A clinically relevant population of leukemic CD34+CD38− cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012 Apr 12;119(15):3571–7. [CrossRef]

- Jordan C, Upchurch D, Szilvassy S, Guzman M, Howard D, Pettigrew A, et al. The interleukin-3 receptor alpha chain is a unique marker for human acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells. Leukemia. 2000 Oct;14(10):1777–84. [CrossRef]

- Jin L, Hope KJ, Zhai Q, Smadja-Joffe F, Dick JE. Targeting of CD44 eradicates human acute myeloid leukemic stem cells. Nat Med. 2006 Oct;12(10):1167–74. [CrossRef]

- Hosen N, Park CY, Tatsumi N, Oji Y, Sugiyama H, Gramatzki M, et al. CD96 is a leukemic stem cell-specific marker in human acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007 Jun 26;104(26):11008–13. [CrossRef]

- Van Rhenen A, Van Dongen GAMS, Kelder A, Rombouts EJ, Feller N, Moshaver B, et al. The novel AML stem cell–associated antigen CLL-1 aids in discrimination between normal and leukemic stem cells. Blood. 2007 Oct 1;110(7):2659–66. [CrossRef]

- Majeti R, Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Pang WW, Jaiswal S, Gibbs KD, et al. CD47 Is an Adverse Prognostic Factor and Therapeutic Antibody Target on Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia Stem Cells. Cell. 2009 Jul;138(2):286–99. [CrossRef]

- Pabst C, Bergeron A, Lavallée VP, Yeh J, Gendron P, Norddahl GL, et al. GPR56 identifies primary human acute myeloid leukemia cells with high repopulating potential in vivo. Blood. 2016 Apr 21;127(16):2018–27. [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa B, Ghiaur G, Smith BD, Jones RJ. Translating leukemia stem cells into the clinical setting: Harmonizing the heterogeneity. Exp Hematol. 2016 Dec;44(12):1130–7. [CrossRef]

- Velten L, Story BA, Hernández-Malmierca P, Raffel S, Leonce DR, Milbank J, et al. Identification of leukemic and pre-leukemic stem cells by clonal tracking from single-cell transcriptomics. Nat Commun. 2021 Mar 1;12(1):1366. [CrossRef]

- Han L, Qiu P, Zeng Z, Jorgensen JL, Mak DH, Burks JK, et al. Single-cell mass cytometry reveals intracellular survival/proliferative signaling in FLT3-ITD-mutated AML stem/progenitor cells. Cytometry A. 2015 Apr;87(4):346–56.

- Ghiaur G, Gerber J, Jones RJ. Concise Review: Cancer Stem Cells and Minimal Residual Disease. STEM CELLS. 2012 Jan;30(1):89–93. [CrossRef]

- Gerber JM, Zeidner JF, Morse S, Blackford AL, Perkins B, Yanagisawa B, et al. Association of acute myeloid leukemias most immature phenotype with risk groups and outcomes. Haematologica. 2016 May 1;101(5):607–16. [CrossRef]

- Borowitz MJ, Shuster JJ, Civin CI, Carroll AJ, Look AT, Behm FG, et al. Prognostic significance of CD34 expression in childhood B-precursor acute lymphocytic leukemia: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1990 Aug;8(8):1389–98. [CrossRef]

- Vergez F, Green AS, Tamburini J, Sarry JE, Gaillard B, Cornillet-Lefebvre P, et al. High levels of CD34+CD38low/-CD123+ blasts are predictive of an adverse outcome in acute myeloid leukemia: a Groupe Ouest-Est des Leucemies Aigues et Maladies du Sang (GOELAMS) study. Haematologica. 2011 Dec 1;96(12):1792–8. [CrossRef]

- Schepers K, Campbell TB, Passegué E. Normal and Leukemic Stem Cell Niches: Insights and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cell Stem Cell. 2015 Mar;16(3):254–67. [CrossRef]

- Ghiaur G, Wroblewski M, Loges S. Acute Myelogenous Leukemia and its Microenvironment: A Molecular Conversation. Semin Hematol. 2015 Jul;52(3):200–6. [CrossRef]

- Ladikou EE, Chevassut T, Pepper CJ, Pepper AG. Dissecting the role of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2020 Jun;189(5):815–25.

- Malfuson JV, Boutin L, Clay D, Thépenier C, Desterke C, Torossian F, et al. SP/drug efflux functionality of hematopoietic progenitors is controlled by mesenchymal niche through VLA-4/CD44 axis. Leukemia. 2014 Apr;28(4):853–64.

- Burger JA, Kipps TJ. CXCR4: a key receptor in the crosstalk between tumor cells and their microenvironment. Blood. 2006 Mar 1;107(5):1761–7. [CrossRef]

- Ghiaur G, Yegnasubramanian S, Perkins B, Gucwa JL, Gerber JM, Jones RJ. Regulation of human hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal by the microenvironment’s control of retinoic acid signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013 Oct;110(40):16121–6. [CrossRef]

- Su M, Alonso S, Jones JW, Yu J, Kane MA, Jones RJ, et al. All-Trans Retinoic Acid Activity in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Role of Cytochrome P450 Enzyme Expression by the Microenvironment. Campbell M, editor. PLOS ONE. 2015 Jun 5;10(6):e0127790. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez D, Palau L, Norsworthy K, Anders NM, Alonso S, Su M, et al. Overcoming microenvironment-mediated protection from ATRA using CYP26-resistant retinoids. Leukemia. 2020 Nov;34(11):3077–81. [CrossRef]

- Konopleva M, Konoplev S, Hu W, Zaritskey A, Afanasiev B, Andreeff M. Stromal cells prevent apoptosis of AML cells by up-regulation of anti-apoptotic proteins. Leukemia. 2002 Sep 1;16(9):1713–24. [CrossRef]

- Tabe Y, Konopleva M. Resistance to energy metabolism - targeted therapy of AML cells residual in the bone marrow microenvironment. Cancer Drug Resist Alhambra Calif. 2023;6(1):138–50. [CrossRef]

- Alonso S, Su M, Jones JW, Ganguly S, Kane MA, Jones RJ, et al. Human bone marrow niche chemoprotection mediated by cytochrome p450 enzymes. Oncotarget. 2015 Jun 20;6(17):14905–12. [CrossRef]

- Chang YT, Hernandez D, Alonso S, Gao M, Su M, Ghiaur G, et al. Role of CYP3A4 in bone marrow microenvironment–mediated protection of FLT3/ITD AML from tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Blood Adv. 2019 Mar 26;3(6):908–16.

- Duan CW, Shi J, Chen J, Wang B, Yu YH, Qin X, et al. Leukemia Propagating Cells Rebuild an Evolving Niche in Response to Therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014 Jun;25(6):778–93. [CrossRef]

- Duarte D, Hawkins ED, Lo Celso C. The interplay of leukemia cells and the bone marrow microenvironment. Blood. 2018 Apr 5;131(14):1507–11. [CrossRef]

- Su M, Chang YT, Hernandez D, Jones RJ, Ghiaur G. Regulation of drug metabolizing enzymes in the leukaemic bone marrow microenvironment. J Cell Mol Med. 2019 Jun;23(6):4111–7. [CrossRef]

- Uy GL, Rettig MP, Motabi IH, McFarland K, Trinkaus KM, Hladnik LM, et al. A phase 1/2 study of chemosensitization with the CXCR4 antagonist plerixafor in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012 Apr 26;119(17):3917–24.

- Cancilla D, Rettig MP, DiPersio JF. Targeting CXCR4 in AML and ALL. Front Oncol. 2020 Sep 4;10:1672. [CrossRef]

- Alonso S, Hernandez D, Chang Y ting, Gocke CD, McCray M, Varadhan R, et al. Hedgehog and retinoid signaling alters multiple myeloma microenvironment and generates bortezomib resistance. J Clin Invest. 2016 Oct 24;126(12):4460–8. [CrossRef]

- Menezes DL, See WL, Risueño A, Tsai KT, Lee JK, Ma J, et al. Oral azacitidine modulates the bone marrow microenvironment in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia in remission: A subanalysis from the QUAZAR AML -001 trial. Br J Haematol. 2023 Jun;201(6):1129–43. [CrossRef]

- Hohtari H, Brück O, Blom S, Turkki R, Sinisalo M, Kovanen PE, et al. Immune cell constitution in bone marrow microenvironment predicts outcome in adult ALL. Leukemia. 2019 Jul;33(7):1570–82. [CrossRef]

- Lemoli RM, Montesinos P, Jain A. Real-world experience with CPX-351 in high-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2023 May;185:103984. [CrossRef]

- Ambinder AJ, Norsworthy K, Hernandez D, Palau L, Paun B, Duffield A, et al. A Phase 1 Study of IRX195183, a RARα-Selective CYP26 Resistant Retinoid, in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory AML. Front Oncol. 2020 Oct 23;10:587062. [CrossRef]

- De Botton S, Cluzeau T, Vigil C, Cook RJ, Rousselot P, Rizzieri DA, et al. Targeting RARA overexpression with tamibarotene, a potent and selective RARα agonist, is a novel approach in AML. Blood Adv. 2023 May 9;7(9):1858–70.

- Sanford D, Lo-Coco F, Sanz MA, Di Bona E, Coutre S, Altman JK, et al. Tamibarotene in patients with acute promyelocytic leukaemia relapsing after treatment with all-trans retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide. Br J Haematol. 2015 Nov;171(4):471–7. [CrossRef]

- Patel SA, Dalela D, Fan AC, Lloyd MR, Zhang TY. Niche-directed therapy in acute myeloid leukemia: optimization of stem cell competition for niche occupancy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2022 Jan 2;63(1):10–8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).