Submitted:

23 August 2024

Posted:

23 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Risk Factors

1.1.1. Common Non-Modifiable Risk Factors

1.1.2. Common Modifiable Risk Factors

1.1.3. Highlighted Risk Factors in East Asia

1.1.4. Transition to Microbiota Focus

2. Epidemiology Findings

| Sample | Microbes increased in ESCC | Microbes decreased in ESCC or increased in control samples | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 67 paired samples (ESCC tissue vs non-tumor tissue) |

Fusobacteria phylum Fusobacterium genus |

Firmicutes phylum Streptococcus genus |

[35] |

| 32 ESCC samples vs 21 healthy controls |

Streptococcus genus Actinobacillus genus Peptostreptococcus genus Fusobacterium genus Prevotella genus |

Fusobacteria phylum Faecalibacterium genus Bacteroides genus Curvibacter genus Blautia genus |

[36] |

| 32 ESCC samples vs 15 esophagitis samples | Streptococcus genus |

Bacteroidetes genus Faecalibacterium genus Bacteroides genus Blautia genus |

[36] |

| 17 ESCC samples vs 16 healthy control samples |

Fusobacteria phylum Prevotella genus Pseudomonas genus |

Actinobacteria phylum Ralstonia genus Burkholderia-Caballeronia-Paraburkholderia genus |

[37] |

| 17 ESCC samples vs 15 post-op ESCC samples |

Fusobacteria phylum Bacteroidetes phylum Prevotella genus |

Pseudomonas genus |

[37] |

| 100 ESCC samples vs 100 adjacent tissue samples or 30 normal esophagus samples | P. gingivalis | [38] | |

| 18 ESCC samples vs 11 normal esophagus samples |

Fusobacteria phylum Bacteroidetes phylum Spirochaetes phylum T. amylovorum, S. infantis, P. nigrescens, P. endodontalis, V. dispar, A. segnis, P. melaninogenica, P. intermedia P. tannerae, P. nanceiensis, S. anginosus |

Proteobacteria phylum Thermi Phylum |

[39] |

| 120 ESCC samples vs adjacent tissue sample from same subjects |

R. mucilaginosa, P. endodontalis unclassified species in the genus Leptotrichia unclassified species in the genus Phyllobacterium unclassified species in the genus Sphingomonas |

class Bacilli N. subflava H. pylori A. parahaemolyticus A. rhizosphaerae, unclassified species in the genus Campylobacter unclassified species in the genus Haemophilus |

[40] |

| 60 ESCC samples vs paired adjacent normal tissue samples | F. nucleatum | [41] | |

| 54 ESCC samples vs 4 normal esophageal tissues |

Proteus genus Firmicutes genus Bacteroides genus Fusobacterium genus |

[42] | |

| 7 ESCC samples vs 70 normal control samples (together with 70 esophagitis, 70 low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and 19 high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia) |

Streptococcus genus Haemophilus genus Neisseria genus Porphyromonas genus |

[43] | |

| 48 ESCC samples vs matched control samples | Staphylococcus genus | [44] | |

| 111 ESCC samples vs 41 normal samples |

Bacteroidetes phylum Fusobacteria phylum Spirochaetae phylum Streptococcus genus F. nucleatum |

Butyrivibrio genus Lactobacillus genus |

[45] |

| 31 ESCC samples vs matched controls |

Peptostreptococcaceae, Leptotrichia, Peptostreptococcus, Anaerovoracaceae, Filifactor, Anaerovoracaceae-Eubacterium_ brachygroup, Lachnoanaerobaculum, Dethiosulfatibacteraceae, Solobacterium, Johnsonella, Prevotellaceae UCG_001, and Tannerella (higher in N0 stage) Treponema and Brevibacillus (higher in N1 and N2 stages) Acinetobacter (higher in T3 stage) Corynebacterium, Aggregatibacter, Saccharimonadaceae-TM7x, and Cupriavidus (higher in T4 stage) |

[46] |

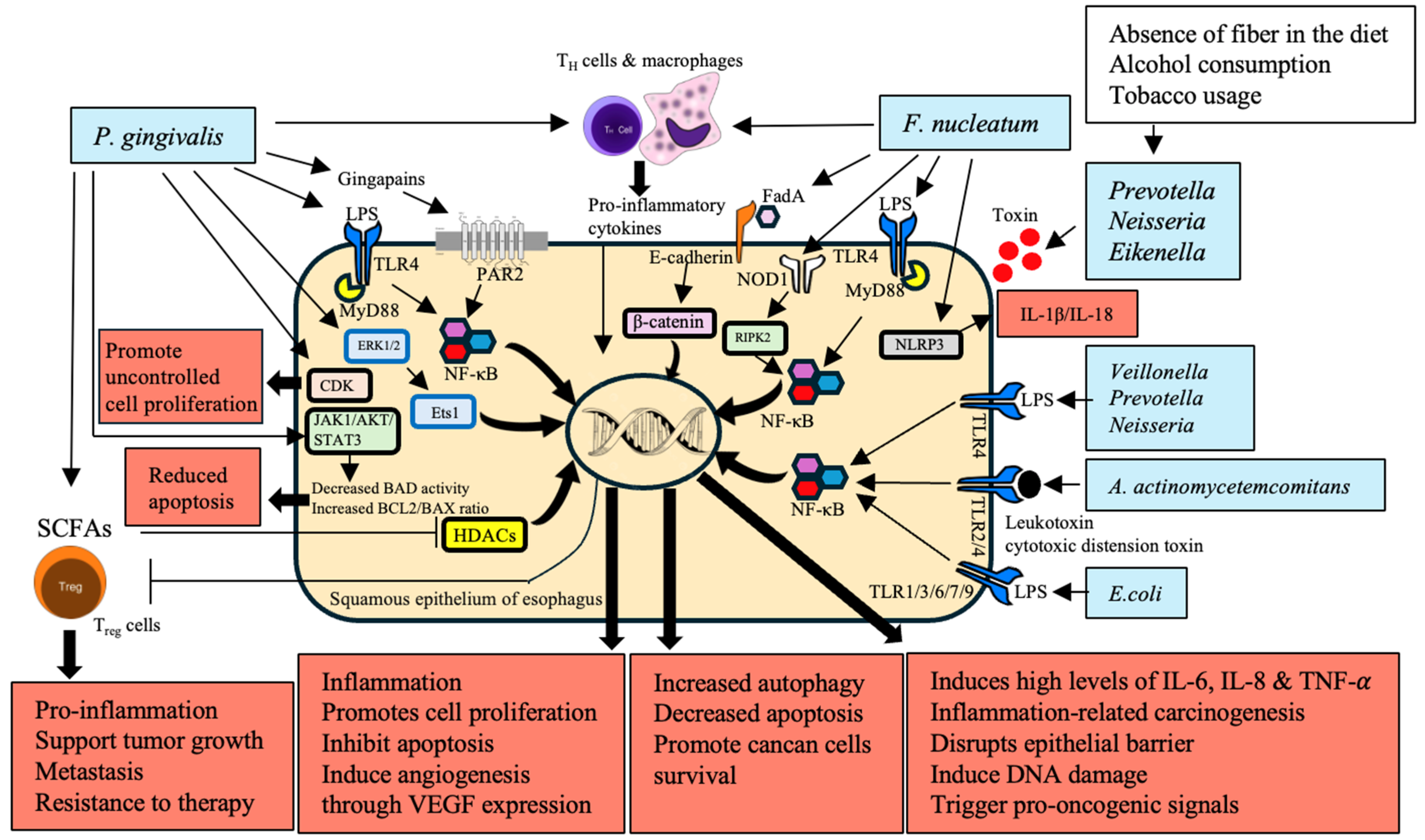

3. Chronic Inflammation

3.1. Immune Regulation by Microbiota

| Bacteria | Mechanism | Impact on EC | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. gingivalis | Activates ERK1/2-Ets1 and PAR2/NF-κB pathways | Increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines reprogramming TME | [47,48,49] |

| Interacts with T cells and macrophages | Disrupts epithelial barrier, induces DNA damage, triggers pro-oncogenic signals | [50] | |

| LPS activates TLR-4 leading to NF-κB activation | Promotes cell proliferation, inhibits apoptosis, induces angiogenesis through VEGF expression | [51] | |

| Inhibits HDACs through SCFAs modulating Treg cell function | Supports tumor growth, metastasis, and resistance to therapy | [52,53,54] | |

| F. nucleatum | Activates NOD1/RIPK2/NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome pathways | Induces high levels of IL-6 and IL-8, driving inflammation-related carcinogenesis | [47,55] |

| LPS activates TLR-4 leading to NF-κB activation |

Recruits and reprograms immune cells within TME, supporting tumor progression and immune evasion | [56] | |

| Interacts with T cells and macrophages | Promotes cell proliferation, inhibits apoptosis, induces angiogenesis through VEGF expression | [51] | |

| E. coli | Upregulates TLRs 1-3, 6, 7, and 9 | Induces early carcinogenic molecular changes through TLR signalling pathway activation | [57] |

| Veillonella, Prevotella, Neisseria | Produces LPS, activates TLR-4 leading to NF-κB activation | Creates a pro-inflammatory environment, contributing to carcinogenesis | [58,59] |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans | Produces virulence factors such as leukotoxin and cytotoxic distension toxin | Exacerbates inflammation and cancer risk | [60] |

| Streptococcus | Increases prevalence with age, producing pro-inflammatory cytokines | Influences chronic inflammation and increases the risk of EC | [61] |

| Campylobacter | Enriched in GERD and BE tissues, associated with IL-18 expression | Associated with increased expression of carcinogenesis-related cytokines | [62] |

3.2. Activation of Inflammatory and Signalling Pathways

3.3. TME and Immune Reprogramming

3.4. Influence of GERD and Microbiota Changes

4. Microbial Dysbiosis

| Bacteria | Mechanism | Impact on EC | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. gingivalis | - Activates NF-κB, ERK1/2-Ets1, and PAR2/NF-κB pathways | - Increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6), disruption of epithelial barriers, DNA damage | [47,48,49] |

| - Elicits chronic inflammation and immune evasion | - Promotes tumor growth and progression, poor clinical outcomes, potential biomarker for ESCC | [38] | |

| F. nucleatum | - Activates NF-κB, NOD1/RIPK2/NF-κB, and NLRP3 inflammasome pathways | - Induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8), creating a pro-tumorigenic environment | [47,55] |

| - Chemokine activation, specifically CCL20 | - Aggressive tumor behaviour, shorter survival, immune suppression, aiding in tumor progression and metastasis | [41] | |

| - Utilizes FadA adhesin/invasin to bind E-cadherin, activating β-catenin signalling | activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, oncogenes, and stimulation of cancer cell proliferation | [76] | |

| T. denticola, S. anginosus | - Found in higher abundance in cancerous esophageal tissues | - Production of inflammatory mediators, promotion of an immunosuppressive microenvironment | [77] |

| E. coli | - Upregulates TLRs 1-3, 6, 7, and 9 | - Induces early carcinogenic molecular changes through TLR signalling pathway activation | [78] |

| Prevotella | - Produces LPS, activates TLR-4, leading to NF-κB activation | - Promotes chronic inflammation, mucosal barrier disruption, and enhancement of inflammatory milieu | [79] |

| Neisseria | - Produces LPS, activates TLR-4, leading to NF-κB activation | - Promotes chronic inflammation, mucosal barrier disruption, and enhancement of inflammatory milieu | [80,81] |

| Eikenella | - Associated with low fiber intake, leading to increased gram-negative bacteria | - Produces endotoxins that trigger inflammation and promote carcinogenesis | [82] |

| A. segnis, T. amylovorum, P. endodontalis, S. infantis, V. dispar, S. anginosus, P. intermedia, P. melaninogenica | - Identified in high-throughput profiling of ESCC | - Contributes to chronic inflammation and tumor-promoting microenvironment | [39] |

| Campylobacter | - Enriched in GERD and BE, associated with IL-18 expression | - Associated with increased expression of carcinogenesis-related cytokines | [83,84] |

| Parvimonas | - Associated with low fiber intake, leading to increased gram-negative bacteria | - Produces endotoxins that trigger inflammation and promote carcinogenesis | [82] |

| Leptotrichia | - Observed in GERD and BE patients | - Produces pro-inflammatory molecules, exacerbating mucosal damage and inflammation, contributing to progression to EAC | [85] |

| Lautropia, Bulleidia, Catonella, Corynebacterium, Moryella, Peptococcus, Cardiobacterium | - Lower carriage in ESCC patients compared to controls | - Altered saliva microbiota associated with higher risk of ESCC | [86] |

| Tannerella forsythia | - Increased levels in EC patients | - Associated with higher risk of EAC | [87] |

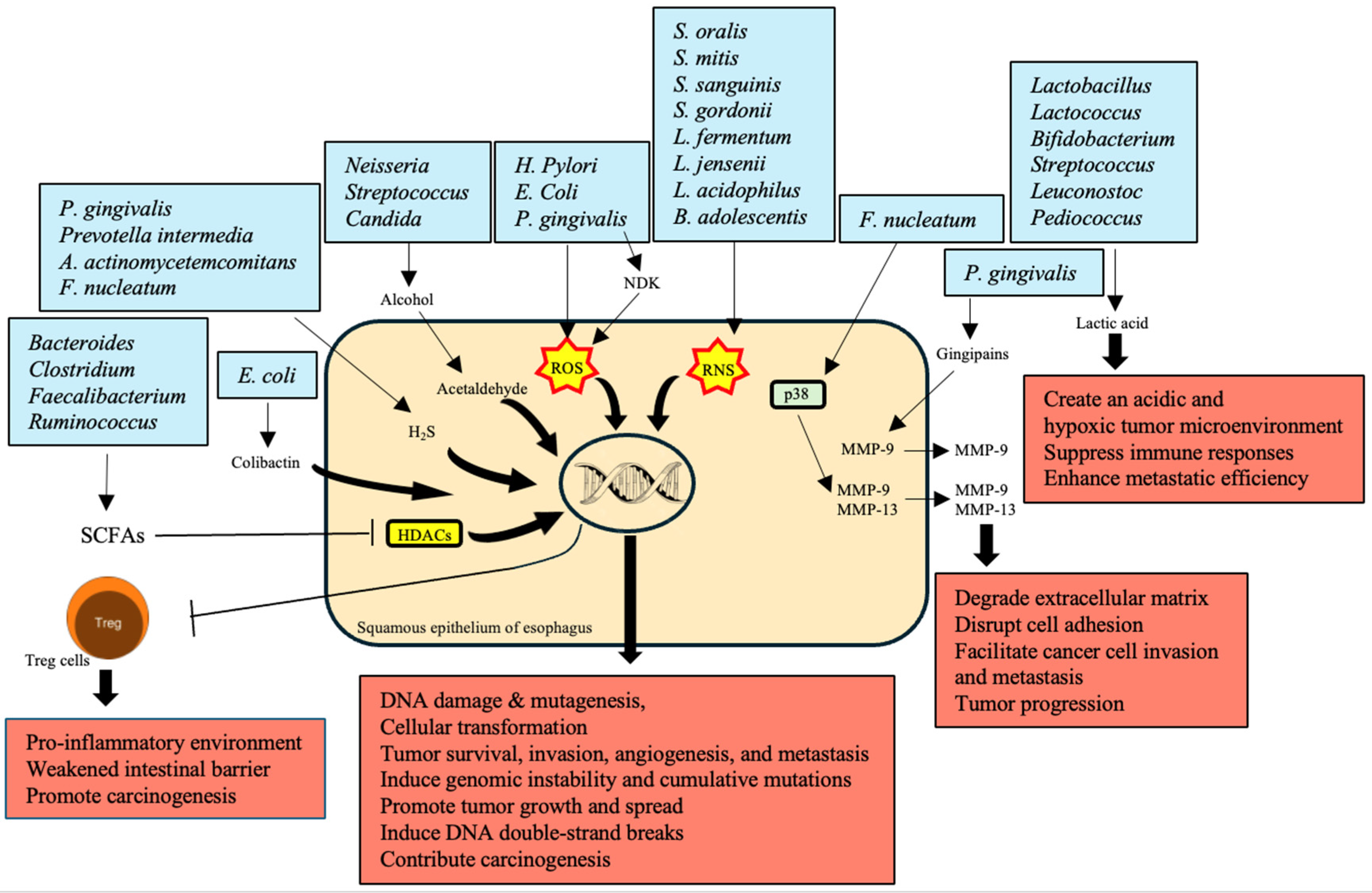

5. Production of Carcinogenic Metabolites

| Bacteria | Mechanism | Impact on EC | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroides, Clostridium, Faecalibacterium, Ruminococcus | Produce SCFAs like butyrate, acetate, and propionate through dietary fiber fermentation | Reduced SCFA production contributes to a pro-inflammatory environment and weakened intestinal barrier, promoting carcinogenesis | [98] |

| Neisseria, Streptococcus, Candida | Metabolize alcohol into acetaldehyde, a highly toxic and carcinogenic substance | Causes DNA damage, mutagenesis, and gut microbiota disruption, increasing EC risk | [101] |

| P. gingivalis, H. pylori, E. coli | Produce ROS | Leads to DNA damage, cellular transformation, tumor survival, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis | [102,103] |

| S. oralis, S. mitis, S. sanguinis, S. gordonii, L. fermentum, L. jensenii, L. acidophilus, B. adolescentis | Produce RNS | Contribute to DNA damage and cancer progression through nitrosative stress | [104,105] |

| P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum | Overexpress MMPs; P. gingivalis produces gingipains to activate MMP-9; F. nucleatum stimulates MMP-9 and MMP-13 through p38 signaling | Degrade extracellular matrix, disrupt cell adhesion, facilitating cancer cell invasion and metastasis, critical in tumor progression | [49,106] |

| P. gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum | Produce H2S, a genotoxic volatile sulfur compound | Induces genomic instability and cumulative mutations, promoting tumor growth and spread by activating various signaling pathways | [107,108] |

| Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus, Leuconostoc, Pediococcus | Produce lactic acid through fermentation | Overproduction creates an acidic and hypoxic tumor microenvironment, suppressing immune responses and enhancing metastatic efficiency | [109] |

| E. coli | Secretes colibactin, a metabolic genetic toxic substance | Induces DNA double-strand breaks, leading to genomic instability and contributing significantly to carcinogenesis | [110] |

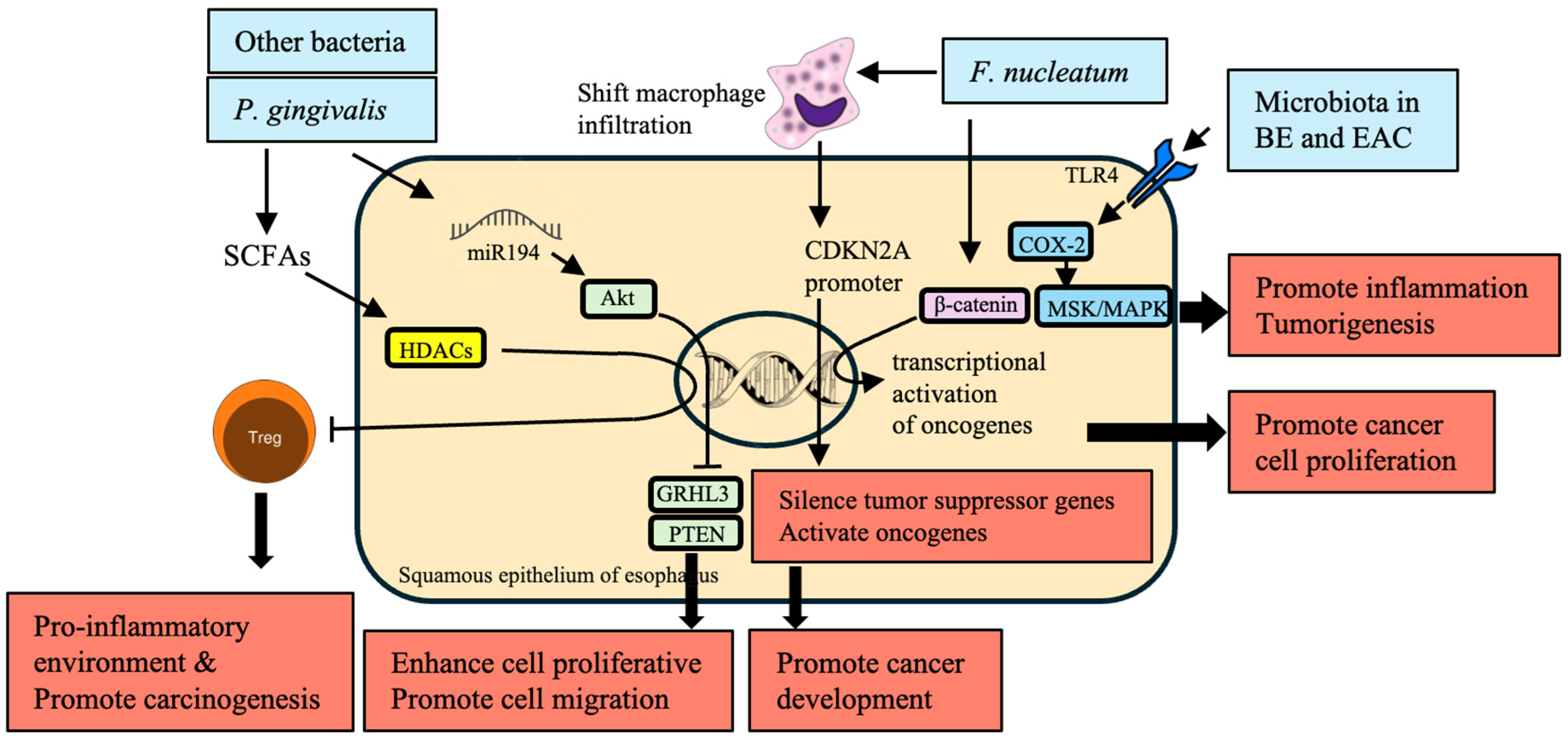

6. Direct Interaction with Epithelial Cells

| Bacteria | Mechanism | Impact on EC | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. gingivalis | Activates ERK1/2-Ets1 and PAR2/NF-κB pathways | Promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion of epithelial cells | [47,48] |

| Induces antiapoptotic activity via JAK1/AKT/STAT3 pathway | Reduces apoptotic activity of epithelial cells | [122] | |

| Secretes NDK | Enhances BCL2 to BAX ratio | [112] | |

| Accelerates S-phase progression by manipulating CDK activity | Promotes cancer cell proliferation | [123] | |

| F. nucleatum | Activates NOD1/RIPK2/NF-κB pathway | Enhances ESCC cell growth and migration | [47,55] |

| Influences TME through chemokine activation | Associated with shorter survival times and aggressive tumor behavior | [118,119] | |

| Activates TLR-4 | Promotes β-catenin signaling leading to oncogene activation | [76,124] | |

| Binds to E-cadherin on carcinoma cells | Facilitates cancer cell proliferation | [76] | |

| Campylobacter, Leptotrichia, Rothia, Capnocytophaga | Enriched in GERD and BE | Contributes to chronic inflammation and epithelial cell transformation | [61,84] |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans | Produces virulence factors that interact with epithelial cells | Promotes cell transformation and carcinogenesis | [60] |

| T. denticola, S. mitis, S. anginosus | Dominates microbiota in cancerous esophageal tissues | Suggests direct interaction with epithelial cells contributing to disease progression | [77] |

| Candida, Neisseria | Metabolizes alcohol into acetaldehyde | Causes DNA damage, mutagenesis, and disrupts gut microbiota | [125,126] |

7. Epigenetic Modifications

| Bacteria | Mechanism | Impact on EC | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. gingivalis | - Inhibits HDACs through SCFAs, modifying Treg cell function and numbers | - Creates a pro-inflammatory environment, contributing to carcinogenesis | [54,133] |

| - Upregulates miR-194 and Akt, downregulates GRHL3 and PTEN | - Enhances pro-proliferative and pro-migratory phenotype of esophageal tumors | [134] | |

| F. nucleatum | - Alters macrophage infiltration and methylation of the CDKN2A promoter | - Silences tumor suppressor genes and activates oncogenes, promoting cancer development | [135] |

| - Activates β-catenin signaling, leading to transcriptional activation of oncogenes | - Promotes cancer cell proliferation through activation of oncogenic pathways | [76,136] | |

| Microbiota in General | - Produces SCFAs that inhibit HDACs, impacting immune response and inflammation | - Creates a pro-inflammatory environment, contributing to carcinogenesis | [54] |

| - Interacts with epithelial cells, leading to genetic changes in mRNAs, miRNAs, and LncRNAs | - Disrupts normal cell regulatory mechanisms, promoting malignant transformation | [137,138] | |

| Microbiota in BE and EAC | - Activates TLR-4, influencing COX-2 expression through NF-κB-independent pathways like MSK and MAPK | - Leads to modifications in gene expression that promote inflammation and tumorigenesis | [121,132] |

8. Interaction with GERD

| Bacteria | Mechanism | Impact on EC | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| H. pylori | - Causes chronic gastritis, leading to changes in gastric acid secretion and subsequent GERD | - Promotes the progression of GERD to BE and EAC | [147] |

| Campylobacter | - Enrichment in GERD and BE patients, associated with inflammatory responses | - Contributes to chronic inflammation and changes in the esophageal mucosa, promoting the progression to EAC | [148] |

| F. nucleatum | - Adheres to and invades epithelial cells, modulates immune response, and promotes inflammation | - Exacerbates progression of BE to EAC through TLR activation and promoting an oncogenic microenvironment | [149] |

| Prevotella | - Increased prevalence in the esophageal microbiota of GERD patients, known for its role in inflammatory processes | - Leads to chronic inflammation and mucosal damage, fostering conditions conducive to BE and EAC | [150] |

| S. anginosus | - Associated with the esophageal microbiota in GERD and BE, contributing to chronic inflammation | - Promotes epithelial cell alterations, facilitating progression from GERD to BE and EAC | [77,151] |

| Leptotrichia | - Enrichment in GERD and BE patients, associated with inflammatory responses | - Promotes chronic inflammation and epithelial cell transformation, contributing to carcinogenesis | [152,153] |

| Rothia | - Enrichment in GERD and BE patients, associated with inflammatory responses | - Contributes to chronic inflammation and mucosal damage, facilitating the progression to EAC | [154] |

| Capnocytophaga | - Enrichment in GERD and BE patients, associated with inflammatory responses | - Promotes chronic inflammation and changes in the esophageal mucosa, fostering conditions conducive to EAC | [155] |

- Campylobacter: It is overrepresented in GERD and BE patients, induction of chronic inflammation and mucosa alteration that might contribute to EAC emergence [148].

- F. nucleatum: It binds to or invades epithelial cells, modulates the immune response, and promotes inflammation, which enhances progression from BE to EAC through TLR activation [149].

- Prevotella: It is overrepresented in GERD, a precursor to BE and EAC, and it may facilitate chronic inflammation and mucosal damage [150].

- Rothia: It is increased in GERD and BE patients, causing chronic inflammation and mucosal damage that promotes progression to EAC [154].

- Capnocytophaga: It tends to be enriched in GERD and BE patients, mechanistically promoting chronic inflammation and esophageal mucosal changes, thereby creating conditions conducive to EAC [155].

9. Metabolic Changes and EC

10. Angiogenesis

| Bacteria | Mechanism | Impact on EC | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| H. pylori | Increases ROS production through virulence factors | Activates angiogenesis and cancer development | [166] |

| Promotes hypoxic conditions stabilizing HIF-1α | Upregulates pro-angiogenic genes such as VEGF, contributing to tumor progression and poor prognosis | [167] | |

| F. nucleatum | Influences IL-8 production | Enhances angiogenesis and tumor invasiveness | [168] |

| Enhances IL-1β production | Creates a pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic microenvironment | [169] | |

| Increases TNF-α levels | Contributes to angiogenesis and tumor progression | [64] | |

| Activates β-catenin signaling, enhancing β-catenin, C-myc, and cyclin D1 expression | Enhances cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth | [76] | |

| P. gingivalis | Modulates inflammatory responses and cytokine production | Enhances tumor angiogenesis | [169] |

| Increases TNF-α levels | Promotes cancer cell proliferation and metastasis | [170] | |

| Produces H2S, activating proliferation, migration, and invasive signaling pathways | Contributes to a hypoxic, pro-angiogenic microenvironment | [107] | |

| Streptococcus species | Stimulates the production of angiogenic factors such as IL-8, VEGF, and bFGF | Promotes angiogenesis and cancer cell growth | [171] |

| General oral microbiota | Produces IL-1β, which activates endothelial cells to produce VEGF and other pro-angiogenic factors | Provides an inflammatory microenvironment conducive to angiogenesis and tumor progression | [172,173] |

11. Future Directions

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deboever, N.; Jones, C.M.; Yamashita, K.; Ajani, J.A.; Hofstetter, W.L. Advances in diagnosis and management of cancer of the esophagus. BMJ 2024, 385, e074962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, H.G.; Xie, S.H.; Lagergren, J. The Epidemiology of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindkvist, B.; Johansen, D.; Stocks, T.; Concin, H.; Bjørge, T.; Almquist, M.; Häggström, C.; Engeland, A.; Hallmans, G.; Nagel, G.; et al. Metabolic risk factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma: a prospective study of 580 000 subjects within the Me-Can project. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E., 3rd; Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; Wong, S.H.; Ng, S.C.; Wong, M.C.S. Updated epidemiology of gastrointestinal cancers in East Asia. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 20, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y. The prognostic value of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in patients with esophageal cancer: evidence from a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther 2017, 10, 2893–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.A.; Wu, J.; Pei, Z.; Yang, L.; Purdue, M.P.; Freedman, N.D.; Jacobs, E.J.; Gapstur, S.M.; Hayes, R.B.; Ahn, J. Oral Microbiome Composition Reflects Prospective Risk for Esophageal Cancers. Cancer Research 2017, 77, 6777–6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baima, G.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Romano, F.; Aimetti, M.; Romandini, M. The Gum–Gut Axis: Periodontitis and the Risk of Gastrointestinal Cancers. Cancers 2023, 15, 4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, E.; Duan, L.; Wu, B.U. Racial and Ethnic Minorities at Increased Risk for Gastric Cancer in a Regional US Population Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 15, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Whittemore, A.S.; Garcia, R.T.; Tawfeek, S.A.; Ning, J.; Lam, S.; Wright, T.L.; Keeffe, E.B. Role of ethnicity in risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004, 2, 820–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Laversanne, M.; Brown, L.M.; Devesa, S.S.; Bray, F. Predicting the Future Burden of Esophageal Cancer by Histological Subtype: International Trends in Incidence up to 2030. Am J Gastroenterol 2017, 112, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggar, F.A.; Boushey, R.P. Colorectal cancer epidemiology: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2009, 22, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, M.H.; Liptrot, S.; Paul, J.; Brown, I.L.; Morrison, D.; McColl, K.E. Oesophageal and gastric intestinal-type adenocarcinomas show the same male predominance due to a 17 year delayed development in females. Gut 2009, 58, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.B.; Chen, Z.L.; Li, J.G.; Hu, X.D.; Shi, X.J.; Sun, Z.M.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, Z.R.; Li, Z.T.; Liu, Z.Y.; et al. Genetic landscape of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet 2014, 46, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, M.J.; Huang, Q.C.; Bao, C.Z.; Li, Y.J.; Li, X.Q.; Ye, D.; Ye, Z.H.; Chen, K.; Wang, J.B. Attributable causes of colorectal cancer in China. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Eshak, E.S.; Shirai, K.; Liu, K.; Dong, J.Y.; Iso, H.; Tamakoshi, A.; Group, J.S. Alcohol Consumption and Risk of Gastric Cancer: The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. J Epidemiol 2021, 31, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhuang, M.; Yuan, Z.; Nie, S.; Lu, M.; Jin, L.; Ye, W. Smoking and alcohol drinking in relation to the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A population-based case-control study in China. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 17249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, P.K.; Millwood, I.Y.; Kartsonaki, C.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Du, H.; Bian, Z.; Lan, J.; Feng, S.; Yu, C.; et al. Alcohol drinking and risks of total and site-specific cancers in China: A 10-year prospective study of 0.5 million adults. Int J Cancer 2021, 149, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, S.; Gillani, S.W.; Siddiqui, A.; Jandrajupalli, S.B.; Poh, V.; Syed Sulaiman, S.A. Diet and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Asia--a Systematic Review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015, 16, 5389–5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.M.; Mizoue, T.; Tanaka, K.; Tsuji, I.; Tamakoshi, A.; Matsuo, K.; Ito, H.; Wakai, K.; Nagata, C.; Sasazuki, S.; et al. Physical activity and colorectal cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence among the Japanese population. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2012, 42, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, C.; Lai, P.K.; Mak, J.W. Immediately modifiable risk factors attributable to colorectal cancer in Malaysia. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslick, G.D.; Lim, L.L.; Byles, J.E.; Xia, H.H.; Talley, N.J. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 1999, 94, 2373–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.T.; Fang, Y. Clonorchis sinensis and clonorchiasis, an update. Parasitol Int 2012, 61, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, M.B.; Gan, X.Q.; Zhao, J.G.; Zheng, W.J.; Li, W.; Jiang, Z.H.; Zhu, T.J.; Zhou, X.N. Effectiveness of health education in improving knowledge, practice and belief related to clonorchiasis in children. Acta Trop 2020, 207, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Martel, C.; Maucort-Boulch, D.; Plummer, M.; Franceschi, S. World-wide relative contribution of hepatitis B and C viruses in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2015, 62, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, J.J.; Stevens, G.A.; Groeger, J.; Wiersma, S.T. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine 2012, 30, 2212–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tong, Y.; Yang, C.; Gan, Y.; Sun, H.; Bi, H.; Cao, S.; Yin, X.; Lu, Z. Consumption of hot beverages and foods and the risk of esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, W.P.; Nie, G.J.; Chen, M.J.; Yaz, T.Y.; Guli, A.; Wuxur, A.; Huang, Q.Q.; Lin, Z.G.; Wu, J. Hot food and beverage consumption and the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A case-control study in a northwest area in China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017, 96, e9325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundal, R.; Shaffer, E.A. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol 2014, 6, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, T.; Chen, X. Association between oral microflora and gastrointestinal tumors (Review). Oncol Rep 2021, 46, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Gupta, A.; Chauhan, R.; Bhat, A.A.; Nisar, S.; Hashem, S.; Akhtar, S.; Ahmad, A.; Haris, M.; Singh, M.; et al. Cross-talk between the microbiome and chronic inflammation in esophageal cancer: potential driver of oncogenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2022, 41, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez De Nunzio, S.; Portal-Núñez, S.; Arias Macías, C.M.; Bruna Del Cojo, M.; Adell-Pérez, C.; Latorre Molina, M.; Macías-González, M.; Adell-Pérez, A. Does a Dysbiotic Oral Microbiome Trigger the Risk of Chronic Inflammatory Disease? Current Treatment Options in Allergy 2023, 10, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Lu, X.; Nossa, C.W.; Francois, F.; Peek, R.M.; Pei, Z. Inflammation and intestinal metaplasia of the distal esophagus are associated with alterations in the microbiome. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A.P.; Redinbo, M.R.; Bultman, S.J. The role of the microbiome in cancer development and therapy. CA Cancer J Clin 2017, 67, 326–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Vogtmann, E.; Liu, A.; Qin, J.; Chen, W.; Abnet, C.C.; Wei, W. Microbial characterization of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma from a high-risk region of China. Cancer 2019, 125, 3993–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, J.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S. Characterization of Esophageal Microbiota in Patients With Esophagitis and Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 774330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; He, R.; Hou, G.; Ming, W.; Fan, T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, W.; Wang, W.; Lu, Z.; et al. Characterization of the Esophageal Microbiota and Prediction of the Metabolic Pathways Involved in Esophageal Cancer. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Li, S.; Ma, Z.; Liang, S.; Shan, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, P.; Liu, G.; Zhou, F.; et al. Presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis in esophagus and its association with the clinicopathological characteristics and survival in patients with esophageal cancer. Infect Agent Cancer 2016, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Chen, C.H.; Jia, M.; Xing, X.; Gao, L.; Tsai, H.T.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, B.; Yeung, S.J.; et al. Tumor-Associated Microbiota in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 641270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Rao, W.; Xiang, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, S.; Yu, K.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y.; et al. Characteristics and interplay of esophageal microbiota in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, K.; Baba, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Mima, K.; Miyake, K.; Nakamura, K.; Sawayama, H.; Kinoshita, K.; Ishimoto, T.; Iwatsuki, M.; et al. Human Microbiome Fusobacterium Nucleatum in Esophageal Cancer Tissue Is Associated with Prognosis. Clin Cancer Res 2016, 22, 5574–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Bai, W.; Zhao, C.; Wang, J. Distribution of esophagus flora in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and its correlation with clinicopathological characteristics. Transl Cancer Res 2020, 9, 3973–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Shao, D.; Zhou, J.; Gu, J.; Qin, J.; Chen, W.; Wei, W. Signatures within esophageal microbiota with progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res 2020, 32, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaleva, O.; Podlesnaya, P.; Rashidova, M.; Samoilova, D.; Petrenko, A.; Mochalnikova, V.; Kataev, V.; Khlopko, Y.; Plotnikov, A.; Gratchev, A. Prognostic Significance of the Microbiome and Stromal Cells Phenotype in Esophagus Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shi, C.; Zheng, J.; Guo, Y.; Fan, T.; Zhao, H.; Jian, D.; Cheng, X.; Tang, H.; Ma, J. Fusobacterium nucleatum predicts a high risk of metastasis for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Microbiol 2021, 21, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Xiao, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhou, T.; Yin, Y. Comparison of tumor-associated and nontumor-associated esophageal mucosa microbiota in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e30483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder Gallimidi, A.; Fischman, S.; Revach, B.; Bulvik, R.; Maliutina, A.; Rubinstein, A.M.; Nussbaum, G.; Elkin, M. Periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum promote tumor progression in an oral-specific chemical carcinogenesis model. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 22613–22623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, F.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; Pan, Y. Persistent Exposure to Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes Proliferative and Invasion Capabilities, and Tumorigenic Properties of Human Immortalized Oral Epithelial Cells. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, H.; Sugita, H.; Kuboniwa, M.; Iwai, S.; Hamada, M.; Noda, T.; Morisaki, I.; Lamont, R.J.; Amano, A. Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma through induction of proMMP9 and its activation. Cell Microbiol 2014, 16, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, S.C.; Agurto, M.G.; Martello, L.A. The oral-gut-circulatory axis: from homeostasis to colon cancer. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, K.; Yanamoto, S. Oral Bacterial Contributions to Gingival Carcinogenesis and Progression. Cancer Prevention Research 2023, 16, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooks, M.G.; Garrett, W.S. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2016, 16, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, R.; de Zoeten, E.F.; Ozkaynak, E.; Chen, C.; Wang, L.; Porrett, P.M.; Li, B.; Turka, L.A.; Olson, E.N.; Greene, M.I.; et al. Deacetylase inhibition promotes the generation and function of regulatory T cells. Nat Med 2007, 13, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangan, P.; Mondino, A. Microbial short-chain fatty acids: a strategy to tune adoptive T cell therapy. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2022, 10, e004147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomoto, D.; Baba, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tsutsuki, H.; Okadome, K.; Harada, K.; Ishimoto, T.; Iwatsuki, M.; Iwagami, S.; Miyamoto, Y.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression via the NOD1/RIPK2/NF-κB pathway. Cancer Lett 2022, 530, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Wang, J.; Dong, J.; Hu, P.; Guo, Q. Periodontopathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum and Their Roles in the Progression of Respiratory Diseases. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, A.H.; Kelly, L.A.; Kreft, R.; Barlek, M.; Omstead, A.N.; Matsui, D.; Boyd, N.H.; Gazarik, K.E.; Heit, M.I.; Nistico, L.; et al. Associations of microbiota and toll-like receptor signaling pathway in esophageal adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhti, S.Z.; Latifi-Navid, S. Oral microbiota and Helicobacter pylori in gastric carcinogenesis: what do we know and where next? BMC Microbiology 2021, 21, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asili, P.; Mirahmad, M.; Rezaei, P.; Mahdavi, M.; Larijani, B.; Tavangar, S.M. The Association of Oral Microbiome Dysbiosis with Gastrointestinal Cancers and Its Diagnostic Efficacy. Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer 2023, 54, 1082–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belibasakis, G.N.; Maula, T.; Bao, K.; Lindholm, M.; Bostanci, N.; Oscarsson, J.; Ihalin, R.; Johansson, A. Virulence and Pathogenicity Properties of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Pathogens 2019, 8, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, N.P.; Riordan, S.M.; Castaño-Rodríguez, N.; Wilkins, M.R.; Kaakoush, N.O. Signatures within the esophageal microbiome are associated with host genetics, age, and disease. Microbiome 2018, 6, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackett, K.L.; Siddhi, S.S.; Cleary, S.; Steed, H.; Miller, M.H.; Macfarlane, S.; Macfarlane, G.T.; Dillon, J.F. Oesophageal bacterial biofilm changes in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, Barrett's and oesophageal carcinoma: association or causality? Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2013, 37, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, M.F.; Abaurrea, A.; Azcoaga, P.; Araujo, A.M.; Caffarel, M.M. New perspectives in cancer immunotherapy: targeting IL-6 cytokine family. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2023, 11, e007530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yáñez, L.; Soto, C.; Tapia, H.; Pacheco, M.; Tapia, J.; Osses, G.; Salinas, D.; Rojas-Celis, V.; Hoare, A.; Quest, A.F.G.; et al. Co-Culture of P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum Synergistically Elevates IL-6 Expression via TLR4 Signaling in Oral Keratinocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamarajan, P.; Ateia, I.; Shin, J.M.; Fenno, J.C.; Le, C.; Zhan, L.; Chang, A.; Darveau, R.; Kapila, Y.L. Periodontal pathogens promote cancer aggressivity via TLR/MyD88 triggered activation of Integrin/FAK signaling that is therapeutically reversible by a probiotic bacteriocin. PLOS Pathogens 2020, 16, e1008881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quail, D.F.; Joyce, J.A. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med 2013, 19, 1423–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, S.; Mao, M.; Gong, Y.; Li, X.; Lei, T.; Liu, C.; Wu, S.; Hu, Q. T-cell infiltration and its regulatory mechanisms in cancers: insights at single-cell resolution. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2024, 43, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, T. IL-6 in inflammation, autoimmunity and cancer. International Immunology 2020, 33, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Li, R.; Ma, L.; Liu, L.; Lai, X.; Yang, D.; Wei, J.; Ma, D.; Li, Z. Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes the motility of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by activating NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Microbes Infect 2019, 21, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Yang, Y.; Han, B.; Wang, Q.; Du, S. Investigating the causal relationship of gut microbiota with GERD and BE: a bidirectional mendelian randomization. BMC Genomics 2024, 25, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Guo, L.; Liu, J.J.; Zhao, H.P.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.H. Alteration of the esophageal microbiota in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2019, 25, 2149–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajayi, T.A.; Cantrell, S.; Spann, A.; Garman, K.S. Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer: Links to microbes and the microbiome. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14, e1007384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Latif, M.M.; Kelleher, D.; Reynolds, J.V. Potential role of NF-kappaB in esophageal adenocarcinoma: as an emerging molecular target. J Surg Res 2009, 153, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.K.; Panda, M.; Das, A.K.; Rahman, T.; Das, R.; Das, K.; Sarma, A.; Kataki, A.C.; Chattopadhyay, I. Dysbiosis of salivary microbiome and cytokines influence oral squamous cell carcinoma through inflammation. Archives of Microbiology 2021, 203, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; He, R.; Hou, G.; Ming, W.; Fan, T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, W.; Wang, W.; Lu, Z.; et al. Characterization of the Esophageal Microbiota and Prediction of the Metabolic Pathways Involved in Esophageal Cancer. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M.R.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Hao, Y.; Cai, G.; Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narikiyo, M.; Tanabe, C.; Yamada, Y.; Igaki, H.; Tachimori, Y.; Kato, H.; Muto, M.; Montesano, R.; Sakamoto, H.; Nakajima, Y.; et al. Frequent and preferential infection of Treponema denticola, Streptococcus mitis, and Streptococcus anginosus in esophageal cancers. Cancer Sci 2004, 95, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, A.H.; Kelly, L.A.; Kreft, R.E.; Barlek, M.; Omstead, A.N.; Matsui, D.; Boyd, N.H.; Gazarik, K.E.; Heit, M.I.; Nistico, L.; et al. Associations of microbiota and toll-like receptor signaling pathway in esophageal adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.M. The immune response to Prevotella bacteria in chronic inflammatory disease. Immunology 2017, 151, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, M.; Bartfeld, S.; Munke, R.; Lange, C.; Ogilvie, L.A.; Friedrich, A.; Meyer, T.F. Activation of NF-κB by Neisseria gonorrhoeae is associated with microcolony formation and type IV pilus retraction. Cellular Microbiology 2011, 13, 1168–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikucki, A.; McCluskey, N.R.; Kahler, C.M. The Host-Pathogen Interactions and Epicellular Lifestyle of Neisseria meningitidis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 862935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobel, Y.R.; Snider, E.J.; Compres, G.; Freedberg, D.E.; Khiabanian, H.; Lightdale, C.J.; Toussaint, N.C.; Abrams, J.A. Increasing Dietary Fiber Intake Is Associated with a Distinct Esophageal Microbiome. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2018, 9, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, A. Human Immunity Against Campylobacter Infection. Immune Netw 2019, 19, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Ando, T.; Ishiguro, K.; Maeda, O.; Watanabe, O.; Funasaka, K.; Nakamura, M.; Miyahara, R.; Ohmiya, N.; Goto, H. Characterization of bacterial biota in the distal esophagus of Japanese patients with reflux esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus. BMC Infect Dis 2013, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Shrestha, P.; Qiu, Z.; Harman, D.G.; Teoh, W.C.; Al-Sohaily, S.; Liem, H.; Turner, I.; Ho, V. Distinct Microbiota Dysbiosis in Patients with Non-Erosive Reflux Disease and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Winckler, B.; Lu, M.; Cheng, H.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Jin, L.; Ye, W. Oral Microbiota and Risk for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a High-Risk Area of China. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0143603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.A.; Wu, J.; Pei, Z.; Yang, L.; Purdue, M.P.; Freedman, N.D.; Jacobs, E.J.; Gapstur, S.M.; Hayes, R.B.; Ahn, J. Oral Microbiome Composition Reflects Prospective Risk for Esophageal Cancers. Cancer Res 2017, 77, 6777–6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conteh, A.R.; Huang, R. Targeting the gut microbiota by Asian and Western dietary constituents: a new avenue for diabetes. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2020, 9, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Lecomte, V.; Maloney, C.A.; Morris, M.J. Cross-talk among metabolic parameters, esophageal microbiota, and host gene expression following chronic exposure to an obesogenic diet. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 45753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Chen, H.M.; Yang, S.F.; Liang, C.; Peng, C.Y.; Lin, F.M.; Tsai, L.L.; Wu, B.C.; Hsin, C.H.; Chuang, C.Y.; et al. Bacterial alterations in salivary microbiota and their association in oral cancer. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 16540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osias, G.L.; Bromer, M.Q.; Thomas, R.M.; Friedel, D.; Miller, L.S.; Suh, B.; Lorber, B.; Parkman, H.P.; Fisher, R.S. Esophageal bacteria and Barrett’s esophagus: a preliminary report. Dig Dis Sci 2004, 49, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, I.; Konikoff, F.M.; Oppenheim, M.; Gophna, U.; Half, E.E. Gastric microbiota is altered in oesophagitis and Barrett’s oesophagus and further modified by proton pump inhibitors. Environ Microbiol 2014, 16, 2905–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.H.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, W.F.; Fu, P.Y.; Xu, J.Q.; Wang, T.Y.; Yao, L.; Liu, Z.Q.; Li, X.Q.; Zhang, Z.C.; et al. The role of type II esophageal microbiota in achalasia: Activation of macrophages and degeneration of myenteric neurons. Microbiol Res 2023, 276, 127470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Sato, H.; Mizusawa, T.; Tominaga, K.; Ikarashi, S.; Hayashi, K.; Mizuno, K.I.; Hashimoto, S.; Yokoyama, J.; Terai, S. Comparison of Oral and Esophageal Microbiota in Patients with Achalasia Before and After Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy. Turk J Gastroenterol 2021, 32, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, S.E.; Yeo, S. Production and Absorption of Short-Chain Fatty Acids. In Dietary Fiber: Chemistry, Physiology, and Health Effects, Kritchevsky, D., Bonfield, C., Anderson, J.W., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1990; pp. 301–315. [Google Scholar]

- Tomás-Pejó, E.; González-Fernández, C.; Greses, S.; Kennes, C.; Otero-Logilde, N.; Veiga, M.C.; Bolzonella, D.; Müller, B.; Passoth, V. Production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) as chemicals or substrates for microbes to obtain biochemicals. Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts 2023, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.T.; Perez Santiago, J.; Iablokov, S.N.; Chopra, D.; Rodionov, D.A.; Peterson, S.N. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Modulate Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition and Functional Potential. Current Microbiology 2022, 79, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Pramanik, S. Structural diversity, functional aspects and future therapeutic applications of human gut microbiome. Archives of Microbiology 2021, 203, 5281–5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Li, W.; Meng, H. A double-edged sword: Role of butyrate in the oral cavity and the gut. Mol Oral Microbiol 2021, 36, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Tang, D.; Hou, P.; Shen, W.; Li, H.; Wang, T.; Liu, R. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in patients with esophageal cancer. Microb Pathog 2021, 150, 104709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagaino, R.; Washio, J.; Abiko, Y.; Tanda, N.; Sasaki, K.; Takahashi, N. Metabolic property of acetaldehyde production from ethanol and glucose by oral Streptococcus and Neisseria. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 10446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, O.; Naito, Y.; Yoshikawa, T. Helicobacter pylori: a ROS-inducing bacterial species in the stomach. Inflammation Research 2010, 59, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charoensaensuk, V.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lin, Y.-H.; Ou, K.-L.; Yang, L.-Y.; Lu, D.-Y. Porphyromonas gingivalis Induces Proinflammatory Cytokine Expression Leading to Apoptotic Death through the Oxidative Stress/NF-κB Pathway in Brain Endothelial Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Manzano-Pech, L.; Rubio-Ruíz, M.E.; Soto, M.E.; Guarner-Lans, V. Nitrosative Stress and Its Association with Cardiometabolic Disorders. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abranches, J.; Zeng, L.; Kajfasz, J.K.; Palmer, S.R.; Chakraborty, B.; Wen, Z.T.; Richards, V.P.; Brady, L.J.; Lemos, J.A. Biology of Oral Streptococci. Microbiol Spectr 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uitto, V.J.; Baillie, D.; Wu, Q.; Gendron, R.; Grenier, D.; Putnins, E.E.; Kanervo, A.; Firth, J.D. Fusobacterium nucleatum increases collagenase 3 production and migration of epithelial cells. Infect Immun 2005, 73, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.-D.; Ngowi, E.E.; Zhai, Y.-K.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Khan, N.H.; Kombo, A.F.; Khattak, S.; Li, T.; Ji, X.-Y. Role of Hydrogen Sulfide in Oral Disease. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2022, 2022, 1886277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attene-Ramos, M.S.; Wagner, E.D.; Plewa, M.J.; Gaskins, H.R. Evidence that hydrogen sulfide is a genotoxic agent. Mol Cancer Res 2006, 4, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiński, T.M.; Szkaradkiewicz, A.K. Characteristic of bacteriocines and their application. Pol J Microbiol 2013, 62, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faïs, T.; Delmas, J.; Barnich, N.; Bonnet, R.; Dalmasso, G. Colibactin: More Than a New Bacterial Toxin. Toxins (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, M.T.; Salaspuro, M. Local Acetaldehyde-An Essential Role in Alcohol-Related Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Carcinogenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; Spooner, R.; DeGuzman, J.; Koutouzis, T.; Ojcius, D.M.; Yilmaz, Ö. Porphyromonas gingivalis-nucleoside-diphosphate-kinase inhibits ATP-induced reactive-oxygen-species via P2X7 receptor/NADPH-oxidase signalling and contributes to persistence. Cell Microbiol 2013, 15, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, R.; Yilmaz, O. The role of reactive-oxygen-species in microbial persistence and inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2011, 12, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niland, S.; Riscanevo, A.X.; Eble, J.A. Matrix Metalloproteinases Shape the Tumor Microenvironment in Cancer Progression. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byun, J.-K. Tumor lactic acid: a potential target for cancer therapy. Archives of Pharmacal Research 2023, 46, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunt, S.J.; Chaudary, N.; Hill, R.P. The tumor microenvironment and metastatic disease. Clin Exp Metastasis 2009, 26, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C.; Puschhof, J.; Rosendahl Huber, A.; van Hoeck, A.; Wood, H.M.; Nomburg, J.; Gurjao, C.; Manders, F.; Dalmasso, G.; Stege, P.B.; et al. Mutational signature in colorectal cancer caused by genotoxic pks(+) E. coli. Nature 2020, 580, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, L. Fusobacterium nucleatum carcinogenesis and drug delivery interventions. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2024, 209, 115319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xing, S.; Chen, F.; Li, Q.; Dou, S.; Huang, Y.; An, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, G. Intracellular Fusobacterium nucleatum infection attenuates antitumor immunity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhta, H.; Helminen, O.; Lehenkari, P.P.; Saarnio, J.; Karttunen, T.J.; Kauppila, J.H. Toll-like receptors 1, 2, 4 and 6 in esophageal epithelium, Barrett’s esophagus, dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 23658–23667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, R.E.; Siersema, P.D.; Ten Kate, F.J.; Fluiter, K.; Souza, R.F.; Vleggaar, F.P.; Bus, P.; van Baal, J.W. Toll-like receptor 4 activation in Barrett’s esophagus results in a strong increase in COX-2 expression. J Gastroenterol 2014, 49, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Park, Y.; Hasegawa, Y.; Tribble, G.D.; James, C.E.; Handfield, M.; Stavropoulos, M.F.; Yilmaz, O.; Lamont, R.J. Intrinsic apoptotic pathways of gingival epithelial cells modulated by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Cell Microbiol 2007, 9, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Singh, A.K. Porphyromonas gingivalis in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a review. Microbes and Infection 2022, 24, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Guo, F.; Yu, Y.; Sun, T.; Ma, D.; Han, J.; Qian, Y.; Kryczek, I.; Sun, D.; Nagarsheth, N.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Chemoresistance to Colorectal Cancer by Modulating Autophagy. Cell 2017, 170, 548–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.G.S.; Kakodkar, P.; Nayanar, G. Capacity of Candida species to produce acetaldehyde at various concentrations of alcohol. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2022, 26, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muto, M.; Hitomi, Y.; Ohtsu, A.; Shimada, H.; Kashiwase, Y.; Sasaki, H.; Yoshida, S.; Esumi, H. Acetaldehyde production by non-pathogenic Neisseria in human oral microflora: implications for carcinogenesis in upper aerodigestive tract. Int J Cancer 2000, 88, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, H.; Luo, S.; Zheng, Q.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, D. Potential role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by periodontal pathogens in oral cancer. J Cell Mol Med 2024, 28, e18064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, O.; Jungas, T.; Verbeke, P.; Ojcius, D.M. Activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway contributes to survival of primary epithelial cells infected with the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun 2004, 72, 3743–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Jermanus, C.; Barbetta, B.; Choi, C.; Verbeke, P.; Ojcius, D.M.; Yilmaz, O. Porphyromonas gingivalis infection sequesters pro-apoptotic Bad through Akt in primary gingival epithelial cells. Mol Oral Microbiol 2010, 25, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhjiri, S.F.; Park, Y.; Yilmaz, O.; Chung, W.O.; Watanabe, K.; El-Sabaeny, A.; Park, K.; Lamont, R.J. Inhibition of epithelial cell apoptosis by Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2001, 200, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Pan, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, H. Fusobacterium nucleatum in tumors: from tumorigenesis to tumor metastasis and tumor resistance. Cancer Biol Ther 2024, 25, 2306676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergun, P.; Kipcak, S.; Bor, S. Epigenetic Alterations from Barrett’s Esophagus to Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooks, M.G.; Garrett, W.S. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology 2016, 16, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Wang, H.; Shi, H.; Zhu, M.; An, J.; Qi, Y.; Du, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, S. Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes the Proliferation and Migration of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma through the miR-194/GRHL3/PTEN/Akt Axis. ACS Infect Dis 2020, 6, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.E.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, N.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Kang, G.H. Intratumoral Fusobacterium nucleatum abundance correlates with macrophage infiltration and CDKN2A methylation in microsatellite-unstable colorectal carcinoma. Virchows Arch 2017, 471, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Peng, Y.; Yu, J.; Chen, T.; Wu, Y.; Shi, L.; Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Fu, X. Invasive Fusobacterium nucleatum activates beta-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer via a TLR4/P-PAK1 cascade. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 31802–31814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.; Xing, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Tang, D. Effects of Long Non-Coding RNAs Induced by the Gut Microbiome on Regulating the Development of Colorectal Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaieva, N.; Sevcikova, A.; Omelka, R.; Martiniakova, M.; Mego, M.; Ciernikova, S. Gut Microbiota-MicroRNA Interactions in Intestinal Homeostasis and Cancer Development. Microorganisms 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, I.; Yilmaz, Ö. Possible role of Porphyromonas gingivalis in orodigestive cancers. J Oral Microbiol 2019, 11, 1563410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermeking, H. MicroRNAs in the p53 network: micromanagement of tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer 2012, 12, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chela, H.K.; Gangu, K.; Ertugrul, H.; Juboori, A.A.; Daglilar, E.; Tahan, V. The 8th Wonder of the Cancer World: Esophageal Cancer and Inflammation. Diseases 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Lee, S.K. Exploring Esophageal Microbiomes in Esophageal Diseases: A Systematic Review. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2020, 26, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, Y.; Etemadi, A.; Abnet, C.C. Microbiome and Cancers of the Esophagus: A Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Quinn, P.J. Endotoxins: Lipopolysaccharides of Gram-Negative Bacteria. In Endotoxins: Structure, Function and Recognition, Wang, X., Quinn, P.J., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2010; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; von Ehrlich-Treuenstätt, V.; Schardey, J.; Wirth, U.; Zimmermann, P.; Andrassy, J.; Bazhin, A.V.; Werner, J.; Kühn, F. Gut Barrier Dysfunction and Bacterial Lipopolysaccharides in Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2023, 27, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranneh, Y.; Ali, F.; Akim, A.M.; Hamid, H.A.; Khazaai, H.; Fadel, A. Crosstalk between reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory markers in developing various chronic diseases: a review. Applied Biological Chemistry 2017, 60, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canzi Almada de Souza, R.; Hermênio Cavalcante Lima, J. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review of this intriguing relationship. Diseases of the Esophagus 2009, 22, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalanka, J.; Gunn, D.; Singh, G.; Krishnasamy, S.; Lingaya, M.; Crispie, F.; Finnegan, L.; Cotter, P.; James, L.; Nowak, A.; et al. Postinfective bowel dysfunction following <em>Campylobacter enteritis</em> is characterised by reduced microbiota diversity and impaired microbiota recovery. Gut 2023, 72, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engevik, M.A.; Danhof, H.A.; Ruan, W.; Engevik, A.C.; Chang-Graham, A.L.; Engevik, K.A.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Brand, C.K.; Krystofiak, E.S.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Secretes Outer Membrane Vesicles and Promotes Intestinal Inflammation. mBio 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawar, N.; Park, S.G.; Schwartz, J.L.; Callahan, N.; Obrez, A.; Yang, B.; Chen, Z.; Adami, G.R. Salivary microbiome with gastroesophageal reflux disease and treatment. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, O.O.; Dai, Z.; Nie, Y.; Zhao, G.; Cao, L.; Nakatsu, G.; Wu, W.K.; Wong, S.H.; Chen, Z.; Sung, J.J.Y.; et al. Mucosal microbiome dysbiosis in gastric carcinogenesis. Gut 2018, 67, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lory, S. The Family Leptotrichiaceae. In The Prokaryotes: Firmicutes and Tenericutes, Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E.F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E., Thompson, F., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; pp. 213–214. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, R.; Gou, H.; Lau, H.C.H.; Yu, J. Stomach microbiota in gastric cancer development and clinical implications. Gut 2024, gutjnl-2024-332815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigauts, C.; Aizawa, J.; Taylor, S.L.; Rogers, G.B.; Govaerts, M.; Cos, P.; Ostyn, L.; Sims, S.; Vandeplassche, E.; Sze, M.; et al. R othia mucilaginosa is an anti-inflammatory bacterium in the respiratory tract of patients with chronic lung disease. Eur Respir J 2022, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesdachai, S.; Tai, D.B.G.; Yetmar, Z.A.; Misra, A.; Ough, N.; Abu Saleh, O. The Characteristics of Capnocytophaga Infection: 10 Years of Experience. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021, 8, ofab175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertona, S.; Monrabal Lezama, M.; Patti, M.G.; Herbella, F.A.M.; Schlottmann, F. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Obese Patients. In Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: From Pathophysiology to Treatment, Schlottmann, F., Herbella, F.A.M., Patti, M.G., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.X.; Quek, K.F.; Ramadas, A. Dietary and Lifestyle Risk Factors of Obesity Among Young Adults: A Scoping Review of Observational Studies. Current Nutrition Reports 2023, 12, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Zayat, S.R.; Sibaii, H.; Mannaa, F.A. Toll-like receptors activation, signaling, and targeting: an overview. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2019, 43, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scida, S.; Russo, M.; Miraglia, C.; Leandro, G.; Franzoni, L.; Meschi, T.; De’ Angelis, G.L.; Di Mario, F. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and GERD. Acta Biomed 2018, 89, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiga, K.; Tateda, M.; Saijo, S.; Hori, T.; Sato, I.; Tateno, H.; Matsuura, K.; Takasaka, T.; Miyagi, T. Presence of Streptococcus infection in extra-oropharyngeal head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and its implication in carcinogenesis. Oncol Rep 2001, 8, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitelson, M.A.; Arzumanyan, A.; Medhat, A.; Spector, I. Short-chain fatty acids in cancer pathogenesis. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews 2023, 42, 677–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.J.; Zhang, Y.P.; Zheng, Q.Q.; Jin, H.C.; Wang, F.L.; Chen, M.; Shao, L.; Zou, D.H.; Yu, X.M.; Mao, W.M. Helicobacter pylori infection and esophageal cancer risk: an updated meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2013, 19, 6098–6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesza, I.J.; Malesza, M.; Walkowiak, J.; Mussin, N.; Walkowiak, D.; Aringazina, R.; Bartkowiak-Wieczorek, J.; Mądry, E. High-Fat, Western-Style Diet, Systemic Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota: A Narrative Review. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Millán, I.; Brooks, G.A. Reexamining cancer metabolism: lactate production for carcinogenesis could be the purpose and explanation of the Warburg Effect. Carcinogenesis 2017, 38, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, D.K.; Arjunan, A.; Lee, B.; Jung, Y.D. Reactive Oxygen Species and H. pylori Infection: A Comprehensive Review of Their Roles in Gastric Cancer Development. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Valderrama, M.; Cerda-Opazo, P.; Backert, S.; González, M.F.; Carrasco-Véliz, N.; Jorquera-Cordero, C.; Wehinger, S.; Canales, J.; Bravo, D.; Quest, A.F.G. The Helicobacter pylori Urease Virulence Factor Is Required for the Induction of Hypoxia-Induced Factor-1α in Gastric Cells. Cancers 2019, 11, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIlvanna, E.; Linden, G.J.; Craig, S.G.; Lundy, F.T.; James, J.A. Fusobacterium nucleatum and oral cancer: a critical review. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aral, K.; Milward, M.R.; Gupta, D.; Cooper, P.R. Effects of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum on inflammasomes and their regulators in H400 cells. Mol Oral Microbiol 2020, 35, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Shen, X.; Zhou, M.; Tang, B. Periodontal Pathogens Promote Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Regulating ATR and NLRP3 Inflammasome. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, S.; Rivera-Hernandez, T.; Curren, B.F.; Harbison-Price, N.; De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Jespersen, M.G.; Davies, M.R.; Walker, M.J. Pathogenesis, epidemiology and control of Group A Streptococcus infection. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 21, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.H.; Kamada, N.; Kim, Y.G.; Núñez, G. Microbiota-induced IL-1β, but not IL-6, is critical for the development of steady-state TH17 cells in the intestine. J Exp Med 2012, 209, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfo, V.; Romaniello, D.; Mazzeschi, M.; Sgarzi, M.; Grilli, G.; Morselli, A.; Manzan, B.; Rihawi, K.; Lauriola, M. Roles of IL-1 in Cancer: From Tumor Progression to Resistance to Targeted Therapies. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, H.; Takeda, A.; Nabeya, Y.; Okazumi, S.I.; Matsubara, H.; Funami, Y.; Hayashi, H.; Gunji, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Suzuki, T.; et al. Clinical significance of serum vascular endothelial growth factor in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 2001, 92, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, R.; Tyson, D.W.; Rosevear, H.M.; Brosius, F.C. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha is a critical mediator of hypoxia induced apoptosis in cardiac H9c2 and kidney epithelial HK-2 cells. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2008, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Z.; Sun, F.; Meng, Q.; Zhou, M.; Yu, J.; Hu, L. Investigating the predictive value of vascular endothelial growth factor in the evaluation of treatment efficacy and prognosis for patients with non-surgical esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waugh, D.J.J.; Wilson, C. The Interleukin-8 Pathway in Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2008, 14, 6735–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Ouyang, Y.; Lu, N.; Li, N. The NF-κB Signaling Pathway, the Microbiota, and Gastrointestinal Tumorigenesis: Recent Advances. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, J.; Deng, X.; Xiong, F.; Zhang, S.; Gong, Z.; Li, X.; Cao, K.; Deng, H.; He, Y.; et al. The role of microenvironment in tumor angiogenesis. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2020, 39, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.C.; Hughes, C.C.W. Macrophages and angiogenesis: a role for Wnt signaling. Vascular Cell 2012, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmi, Y.; Dotan, S.; Rider, P.; Kaplanov, I.; White, M.R.; Baron, R.; Abutbul, S.; Huszar, M.; Dinarello, C.A.; Apte, R.N.; et al. The role of IL-1β in the early tumor cell-induced angiogenic response. J Immunol 2013, 190, 3500–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkova, A.M.; Gubal, A.R.; Petrova, A.L.; Voronov, E.; Apte, R.N.; Semenov, K.N.; Sharoyko, V.V. Pathogenetic role and clinical significance of interleukin-1β in cancer. Immunology 2023, 168, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Omar, E.M. The importance of interleukin 1β in<em>Helicobacter pylori</em> associated disease. Gut 2001, 48, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Ono, M.; Shono, T.; Izumi, H.; Ishibashi, T.; Suzuki, H.; Kuwano, M. Involvement of interleukin-8, vascular endothelial growth factor, and basic fibroblast growth factor in tumor necrosis factor alpha-dependent angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 1997, 17, 4015–4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naserian, S.; Abdelgawad, M.E.; Afshar Bakshloo, M.; Ha, G.; Arouche, N.; Cohen, J.L.; Salomon, B.L.; Uzan, G. The TNF/TNFR2 signaling pathway is a key regulatory factor in endothelial progenitor cell immunosuppressive effect. Cell Communication and Signaling 2020, 18, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basic, A.; Blomqvist, M.; Dahlén, G.; Svensäter, G. The proteins of Fusobacterium spp. involved in hydrogen sulfide production from L-cysteine. BMC Microbiology 2017, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacteria | Mechanism | Impact on EC | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroides, Clostridium, Faecalibacterium, Ruminococcus | Produce SCFAs, modulate inflammation | Maintain gut health; reduced SCFA production leads to a pro-inflammatory environment and cancer risk | [95,98] |

| H. pylori | Induces chronic gastritis, alters gastric acid secretion | Promotes GERD, BE, and EAC | [162] |

| Campylobacter | Induces inflammatory responses | Promotes chronic inflammation and progression to BEand adenocarcinoma | [40] |

| Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Bifidobacterium, Leuconostoc | Produce lactic acid, create low pH hypoxic environment, induce Warburg effect | Immunosuppression, enhanced tumor metastasis, support cancer cell survival and proliferation | [85] |

| F. nucleatum | Produces LPS, activates β-catenin signaling, enhances oncogene expression (C-myc, cyclin D1) | Promotes cancer cell proliferation, chronic inflammation, and carcinogenesis | [136] |

| P. gingivalis | Modulates ATP/P2X7 signaling, affects ROS and antioxidant responses | Contributes to cancer development through ROS-mediated DNA damage and inflammatory responses | [112] |

| Streptococci, Candida yeasts | Metabolize alcohol to acetaldehyde via ADH activity | Causes DNA damage, increases carcinogenesis risk | [101] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).