1. Introduction

The alarming surge in obesity and diabetes rates within the USA is reaching critical levels, with 41.9% and 14.7%, respectively among American adults [

1,

2]. Moreover, obesity stands as a significant precursor to diabetes, amplifying the urgency of this health crisis [

3]. Both conditions demand sustained attention and comprehensive care, presenting formidable challenges to public health. Addressing this pressing issue necessitates the development of innovative, sustainable long-term strategies. There has been strong evidence suggesting that both obesity and diabetes have been strongly linked with gut microbiota, the vast community of microbes in our intestines [

4]. Studies have showed that lean mice gained significant weight after transferring gut bacteria from obese mice, suggesting that gut microbiota play a key role in managing body weight [

5,

6]. Other studies in animals and humans demonstrate an inverse relationship between obesity and diversity of gut microbiota [

7,

8]. In addition, gut microbiota has been shown to alter low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance upon the modification via dietary interventions [

9]. In particular, a group of gut bacterial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are believed play a role in mediating the effects of gut microbiota [

10]. For instance, diabetes patients were found having a reduced population of SCFAs-producing gut bacteria, suggesting a potential link of gut bacteria with impaired blood sugar control [

4]. These findings also suggest that a potential strategy to manage obesity and type 2 diabetes by targeting gut microbiota.

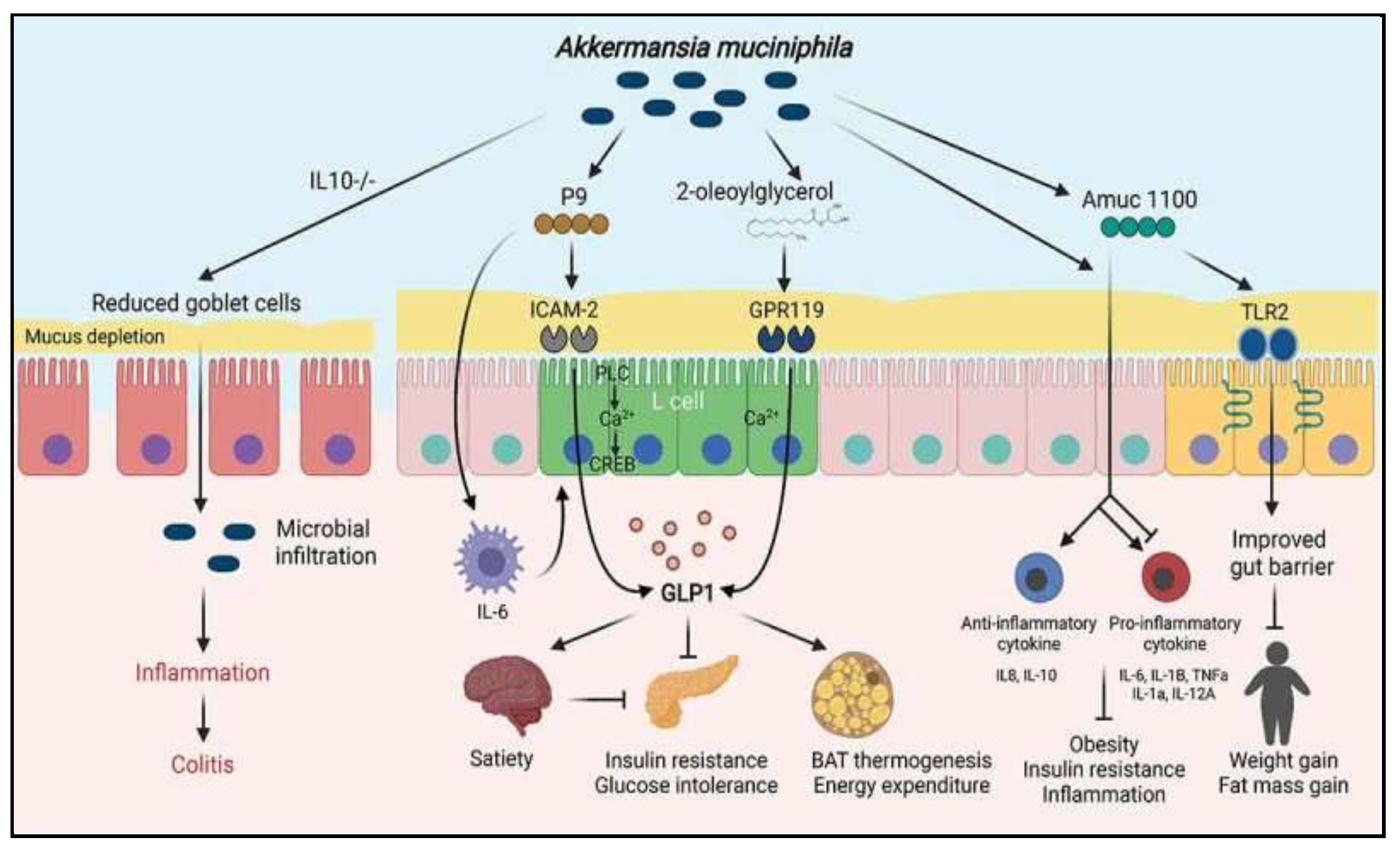

Akkermansia muciniphila (Akk) is one of the most abundant gut bacteria in humans. As a mucin-degrading bacterium, Akk in turn stimulates the growth of the protective gut lining and enhances the gut barrier functions [

11]. Akk has recently gained an increased research interest due to its potential benefits against obesity and metabolic syndrome. Studies has shown that Akk promotes the gut production of SCFAs, improving insulin resistance and host metabolism-factors linked to obesity and diabetes [

12]. Moreover, Akk has been shown to modify gut microbiota by stimulating other beneficial gut bacteria such as Bifidobacteria, and thereby, promoting a healthier gut ecosystem [

13].

There have been the growing number of studies investigating the beneficial role of Akk on obesity and diabetes. Animal studies have been particularly encouraging. For instance, dietary Akk supplementation has been shown to reduce body weight gain, fasting blood glucose, and insulin resistance in mice fed with a high-fat diets [

14,

15]. Similar findings have been demonstrated in other studies, suggesting that the protective role of Akk against obesity and diabetes, though the exact mechanisms are not clear. A recent human trial, while demonstrating improved insulin sensitivity and reduced cholesterol in overweight/obese participants, did not show significant changes in weight or body fat composition [

16]. This discrepancy highlights the need for more comprehensive analysis of Akk effects on obesity and diabetes. A previous review that compared the effects of Akk on various metabolic diseases found a positive association with the onset of type 2 diabetes following Akk supplementation. However, this association lacked strong evidence [

17]. To address this, our meta-analysis aims to systematically evaluate the latest research and compare the effects of Akk administration in different animal studies. We will employ the most comprehensive subgroup analyses possible to provide a more definitive understanding of the impact of Akk.

Figure 1.

Various pathways and models associated with

A. muciniphila [

7]

.

Figure 1.

Various pathways and models associated with

A. muciniphila [

7]

.

2. Materials and Methods

Literature Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

This meta-analysis investigates the effect of Akk dietary intake on obesity and type 2 diabetes, focusing on animal studies that generated quantitative data. The study was conducted strictly following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [

18]. The databases PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library were searched for animal trials on Akk to prevent obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Publications from the inception of the databases until February 2024 were collected. We employed a combination of terms from medical subject headings (MeSH) and keywords. The search strategy encompassed subject headings “Obesity” or “diabetes mellitus” or “metabolic syndromes” in conjunction with identifiers such as “animals” or “mice” or “rats.” The search keywords included “probiotic(s)”, “Akkermansia muciniphila”. All retrieved articles were systematically compiled using Endnote software (20th version). Additionally, we searched bibliographies to ensure inclusivity of relevant literature not initially captured by the database search.

Inclusion criteria: (1) randomized controlled-trials in mice; (2) studies employing Akk probiotic in experimental groups, with a placebo control group for comparison; (3) alternatively, studies utilizing a substrate containing Akk; and (4) Studies reporting outcomes related to the risk and development of diabetes or obesity. Exclusion criteria: (1) duplicate studies; (2) studies that were not-blinded trials; (3) studies where the probiotics composition of the intervention was not specified. Article screening and data extraction were completed by 2 reviewers using Covidence software, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and others [

19].

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two researchers independently selected the studies, resolving any disagreements through consultation with a third researcher. Data from the selected studies were extracted into a shared spreadsheet by one reviewer and validated by a second reviewer. The data extraction utilized a standardized form by an independent researcher. The primary outcome was the incidence or biomarkers of obesity or type 2 diabetes, along with any metabolic syndrome factors, upon administration of Akk in animal models. The secondary outcome included the incidence of adverse events or outlier outcomes. Additional extracted data encompassed demographics, indications for antibiotics, probiotic species and dosage, and duration of probiotics administration. Data were extracted as continuous outcomes [

20].

The quality of the selected studies was assessed using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [

21]. Previously used study quality scales were adapted to evaluate study quality and possible bias risk [

22,

23]. The methodological assessment scale was informed by guidelines and publications from rigorous biomedical research such as STAIR and RIGOR guidelines [

24,

25]. For study quality assessment, the following parameters were considered: presence or absence of exclusion statement, study pre-registration, inclusion of both sexes, aged and/or compromised animals, sample size, control of diet in the experimental group, clear description of infusion parameters (e.g., rate and/or duration, dosage), and conflict of interest statements.

Statistical Analyses

Data analysis were performed using RStudio (version 4.3.3, Ann Arbor, Michigan). Due to the variability in probiotic durations and infusion parameters, a random-effect meta-analysis model utilizing the Derismonian-Laird estimator was selected for all endpoints. The pooled relative risk (RR) and the 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using a random-effects model (DerSimonian-Laird method [

26]) or a fixed-effects model (Mantel-Haenszel method [

27]).

Meta-regression was conducted to evaluate heterogeneity, taking into account variables such as probiotic duration, infusion parameters (including temperature, rate volume), and methodological quality. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses were carried out in cases where unexpected or extreme outcomes were identified in the forest plots. Heterogeneity among the included studies was assessed using the Chi-squared (X²) test and the I² statistic [

28,

29]. P < 0.1 or I

2 > 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity, warranting the adoption of a random-effects model. In the absence of substantial heterogeneity, a fixed-effects model was applied. Publication bias was evaluated through funnel plots and further evaluated using the Begg and Egger tests [

22,

23].

3. Results

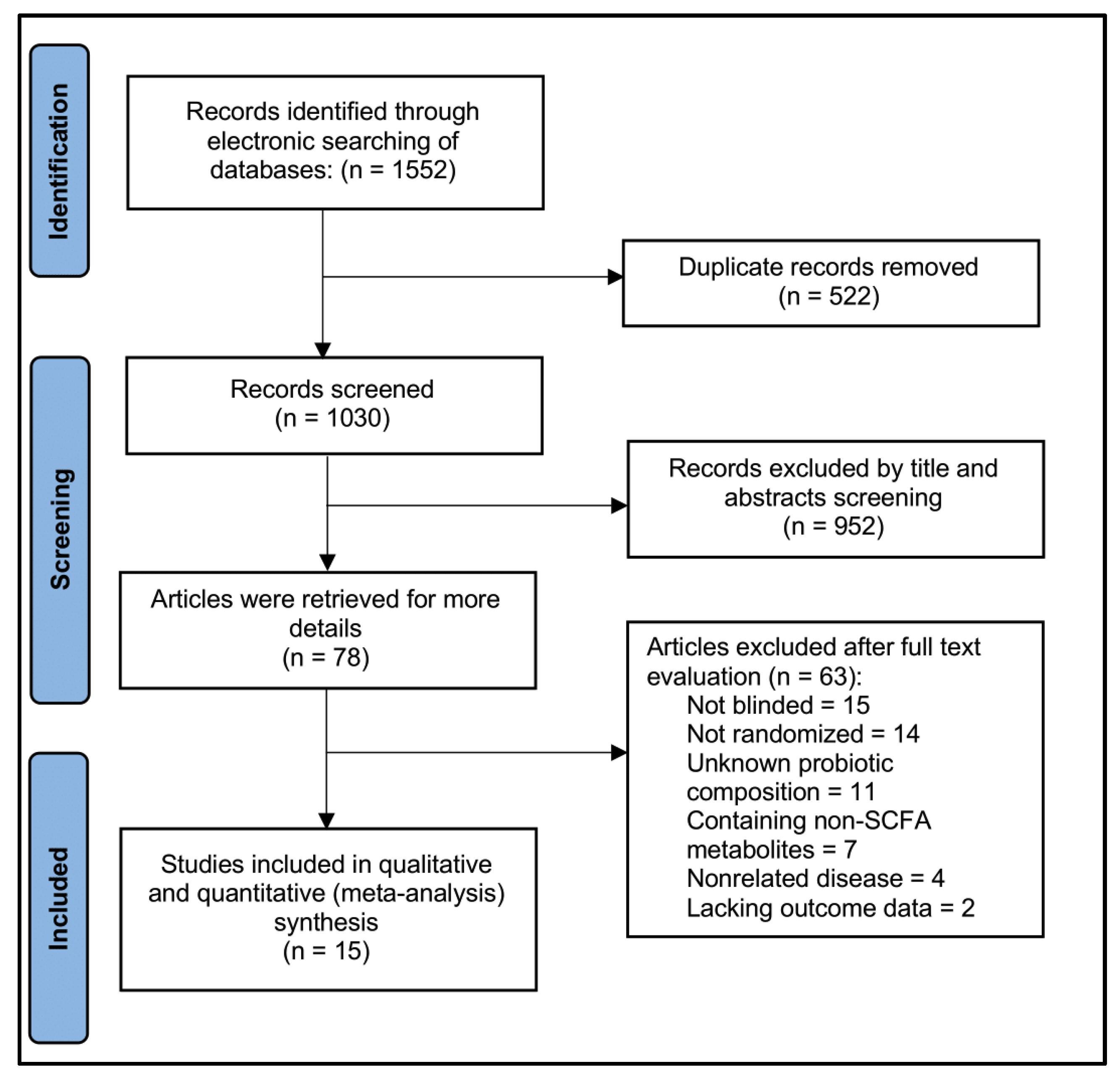

Eligible Studies

A systematic search conducted in January 2024 identified 1,552 citations across four databases: PubMed (461), Cochrane Library (52), EMBASE (336), and Web of Science (703). Following title and abstract screening, 522 duplicates were removed, resulting in 1,030 studies for further evaluation. Of these, 952 were excluded for irrelevance. A full-text review of the remaining 78 studies led to the exclusion of 63 studies due to methodological issues (15 non-blinded, 14 non-randomized, 11 unknown probiotic composition) or irrelevant outcomes (7 reporting non-SCFA metabolites, 4 involving unrelated disease, 2 with missing outcome data). Ultimately, 15 studies met our inclusion criteria [30-44], enrolling a total of 9,312 participants. The search flow details are depicted in

Figure 2.

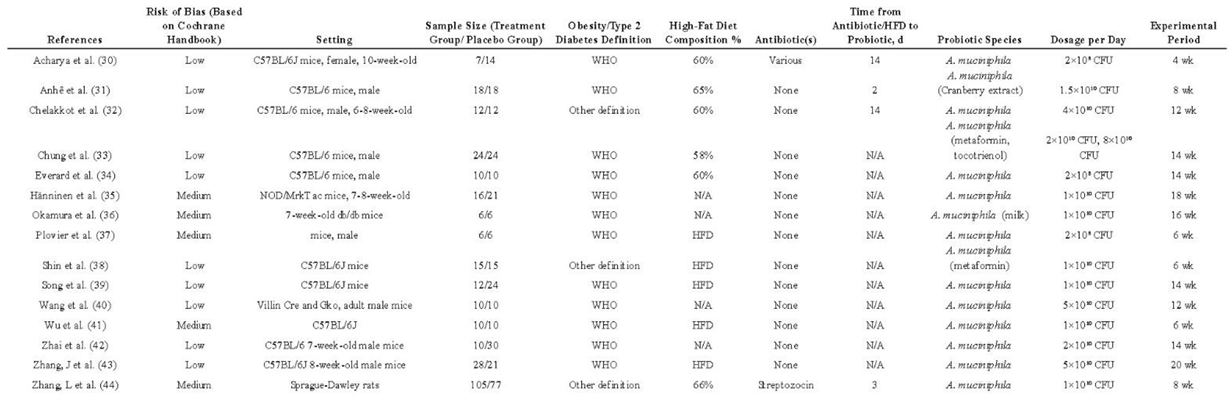

Study Characteristics

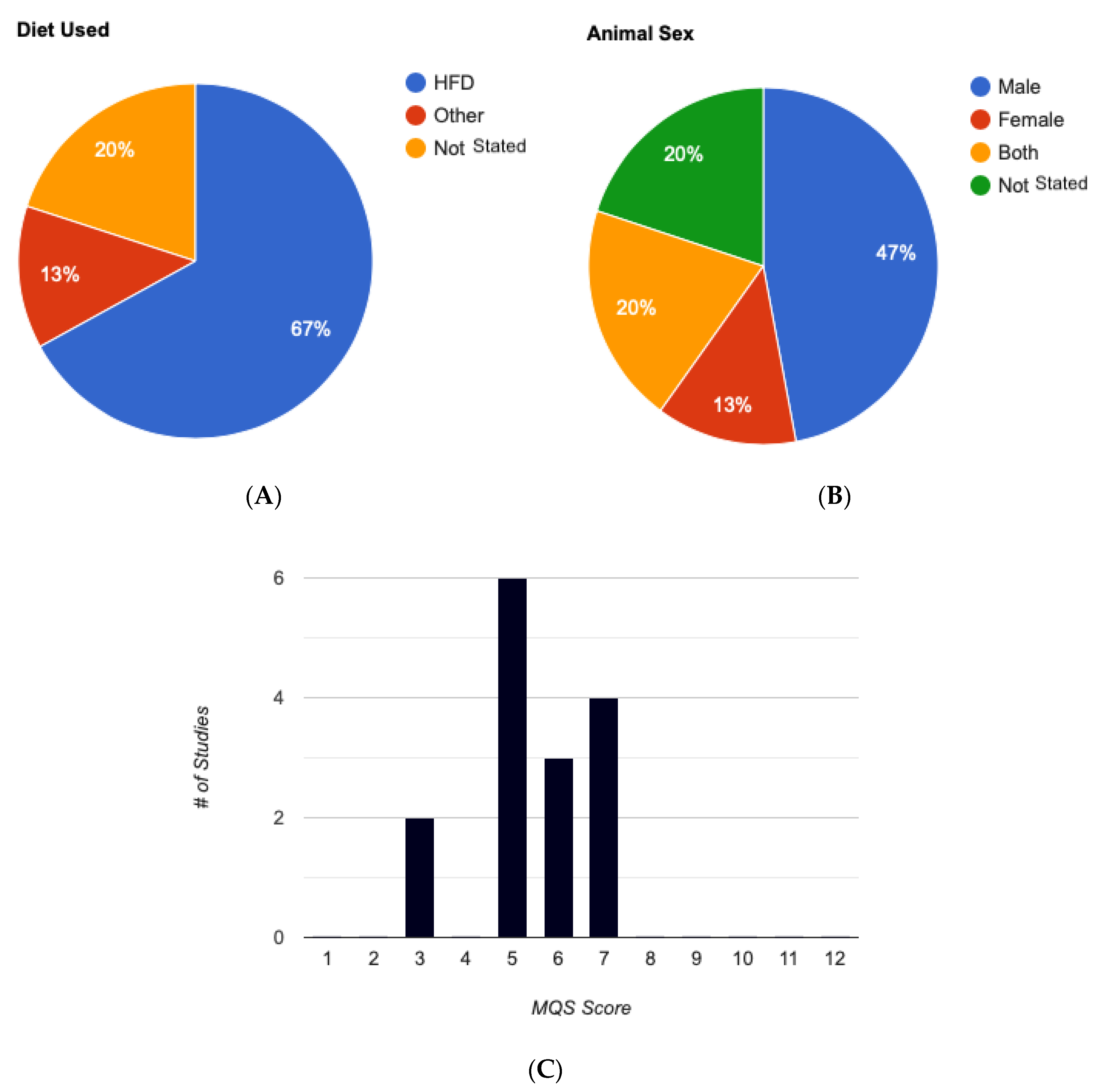

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the selected individual studies. Regarding animal models used for Akk intervention, C57BL/6J was the most prevalent (73%), followed by db/db, NOD mice, and other less common models (27%). Notably, one study utilized a streptozotocin-induced diabetic model in Sprague-Dalwley rats for oral Akk administration. Methodologically, 83% of the studies reported randomization, 60% mentioned exclusions, 47% disclosed conflicts of interest, 26% ensured complete blinding (during Akk administration and outcome assessment), and 11% included the mortality rate for both experimental and placebo groups (

Table 1). None of the studies included pre-registration, considered comorbidity rates, or performed a priori group size calculations. The experimental groups were predominantly fed a high-fat diet (HFD), comprising over 60% fat compared to carbohydrates (

Figure 3A). Most studies employed young, male C57BL/6J, except for two studies which included females but did not consider biological sex as a variable parameter or specify the number of females per group (

Figure 3B).

All studies measured changes in body weight during Akk intervention. Body composition (lean and fat mass) was assessed in 84% of the studies, highlighting its significance as an outcome measure for Akk intervention. Interestingly, four studies employed antibiotics prior to probiotic administration, likely aimed to create a more favorable intestinal environment for robust Akk colonization. The characteristics of interests for the enrolled studies were ranked from most to least prevalent to provide an overview of the current literature characteristics of selected studies (

Table 2).

Quality Assessment

The quality assessment of these studies adhered to the STAIR and RIGOR guidelines which are specifically designed to assess the rigor and robustness of preclinical research, ensuring reliable translation of findings into human studies [

28,

29]. Of the 15 eligible studies, only 10 employed blinding to minimize detection bias. Reporting on other potential biases varied among the studies. Higher risk of attrition bias and other concerns were noted in studies that: 1. lacked clear methods for handling missing outcome data and outliers (3 out of 15 studies); 2. had a short follow-up period (1 out of 15 studies); 3. experienced excessive or unbalanced loss of subjects during the study (6 out of 15 studies); 4. utilized a small sample size (5 out of 15 studies); and 5. had unbalanced baseline characteristics between groups (4 out of 15 studies). Nine studies assessed glucose tolerance, which are key indicator of body’s ability to regulate blood sugar levels. Additionally, 13 studies measured serum insulin levels, and 9 studies assessed fasting blood glucose levels.

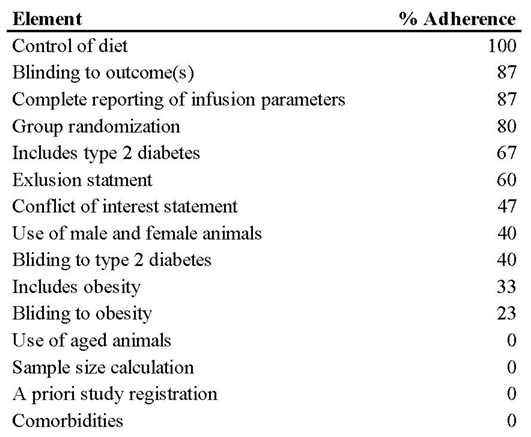

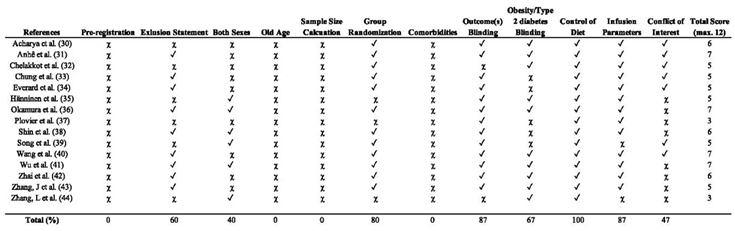

Analysis of Methodological Quality

Table 1 and

Table 2 provide a detailed overview of the methodological quality scale and the analysis of studies incorporating experimental elements.

Table 3 presents the methodological quality scores (MQS) of the selected studies. The overall median score was 5, indicating low to moderate methodological quality across the studies. Scores ranged from 3 to 7 (out of a maximum of 12 points) as illustrated in

Figure 3C. Characteristics of C75BL/6J Mice Model Studies in Akk. All studies, except one, administered Akk immediately after initiating a high-fat diet (HFD) containing 60% of energy from fat. The one exception did not use a HFD but instead administered an antibiotic prior to Akk administration. For studies that included additional supplements, such as metformin or tocotrienol, Akk was administered concurrently with the supplements. In these cases, mice received either HFD with 800 mg of tocotrienol or HFD with 200 mg of metformin, along with Akk.

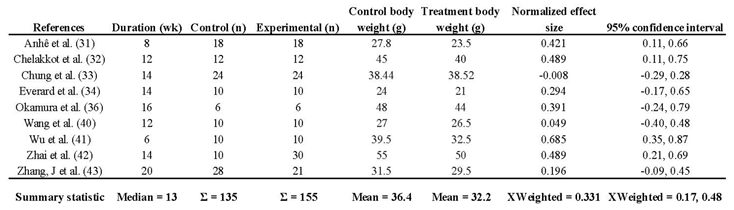

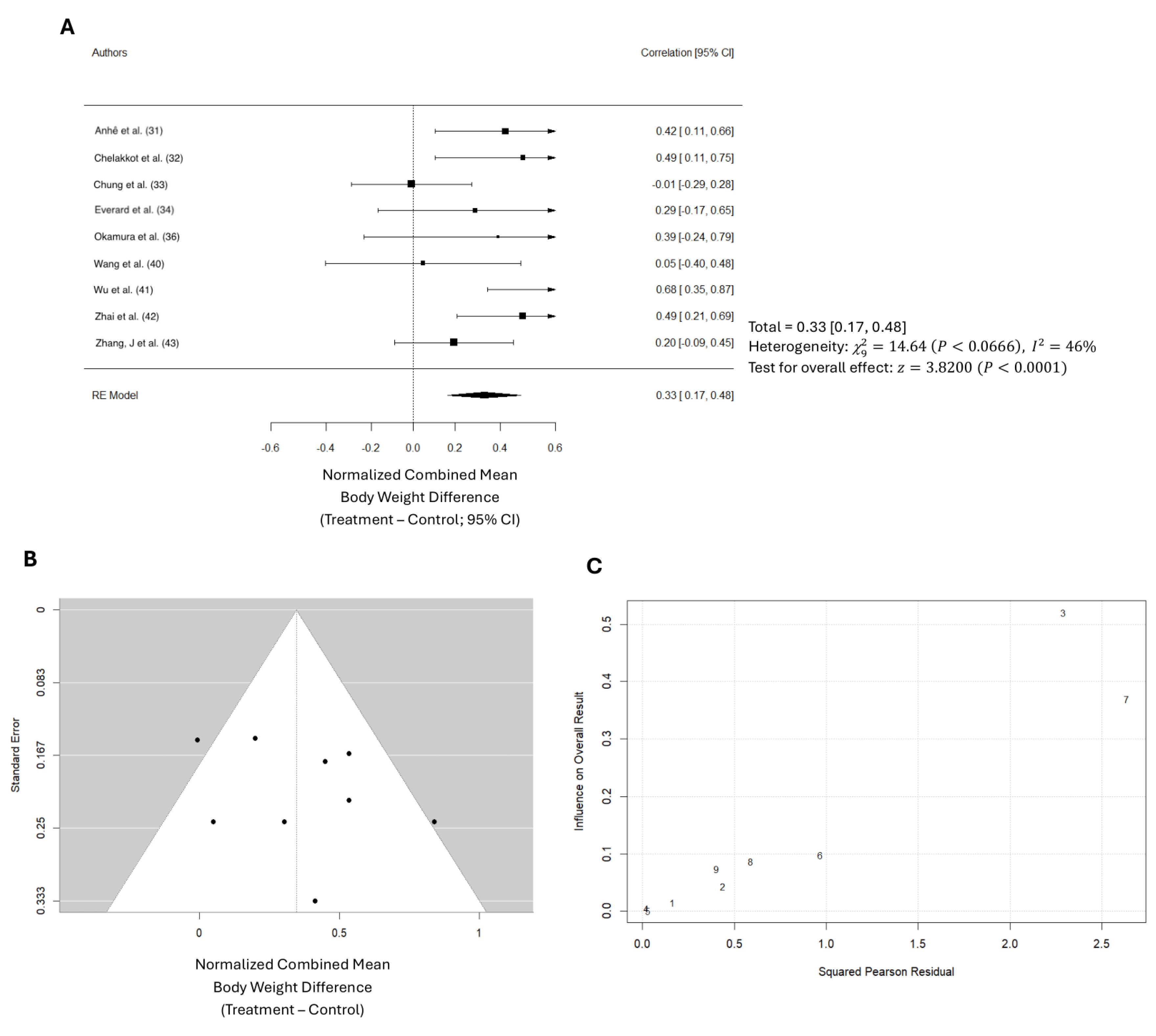

Impact of Akk on Body Weight

Ten studies examined changes in body weight during and after Akk administration. One study used rat, while the other nine studies used mice as the animal model. The study on rat showed that Akk supplementation significantly reduced body weight by an average of 25%. In the nine mice studies, an average weight reduction of 3.8 grams was observed (

Table 4). The total number of mice in the control groups across all studies is 135, compared to 155 in the treatment groups. The average body weight in the Akk groups was 32.2 grams, while the average weight of the controls was 36.4 grams, suggesting a reduction of average body weight gain by 10.4%. The normalized effect sizes vary across studies, with most studies showing positive effect sizes, suggesting that the treatment generally had a beneficial effect. However, it’s important to note that 5 out of the 9 studies reported non-significant changes in overall body weight compared to baseline. This inconsistency suggests significant variability across the studies, with body weight changes ranging from a 0.08 g increase to an 11.0 g decrease following Akk treatment. Overall, the weighted mean effect size of 0.331, with a confidence interval of 0.17 – 0.48, indicates a statistically significant reduction in body weight gain due to Akk treatment. Forest plot analysis indicated a significant reduction in body weight gain among mice treated with Akk compared to controls (p < 0.001,

Figure 4A). The pooled effect size was 0.33 (95% CI: 0.17-0.48). However, substantial heterogeneity existed among studies (I² = 46%), and the funnel plot suggested low publication bias (

Figure 4B). The Baujat plot identified the studies by Chung et al. and Wu et al. as primary contributors to this heterogeneity (

Figure 4C).

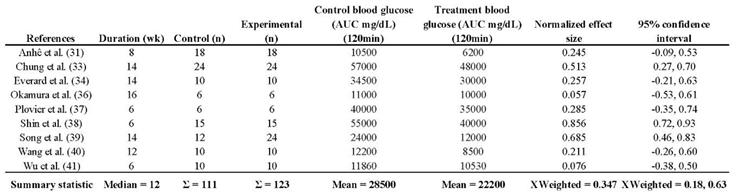

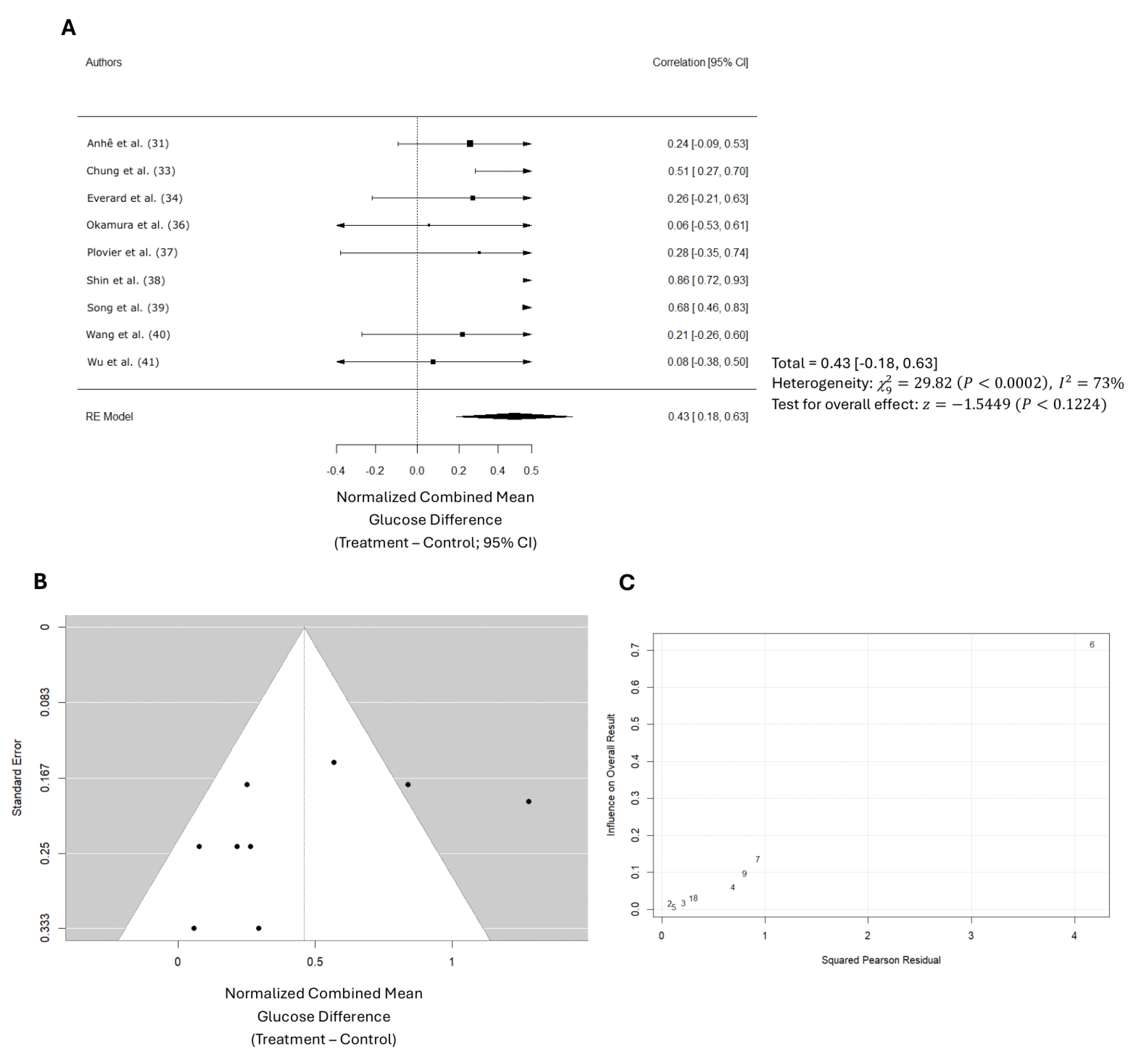

Impact of Akk on Glucose Tolerance

Nine studies evaluated the effect of Akk on glucose tolerance (

Table 5). In total, 111 participants were in the control groups, while 123 received treatment. On average, Akk treatment led to a 22.1% improvement in glucose tolerance, as estimated by the 2-hour area under the curve (AUC) for blood glucose following a glucose tolerance test. Since the exact AUC values were not provided in all the selected studies, these estimates were derived from the individual study graphs. The effect sizes varied. While three studies showed significant reductions in AUC, the majority reported only minor, non-significant decreases.

Overall, a weighted mean effect size of 0.347 (95% CI: 0.18-0.63) indicated a statistically significant reduction in blood glucose levels due to Akk treatment. Forest plot analysis confirmed this, revealing a pooled effect size of 0.43 (95% CI: 0.18-0.63; p < 0.001,

Figure 5A). A random-effects model was used to account for heterogeneity between studies, which was substantial (I² = 73%). Nonetheless, the funnel plot suggested low publication bias (

Figure 5B). The study by Shin et al. primarily contributed to the observed heterogeneity (

Figure 5C).

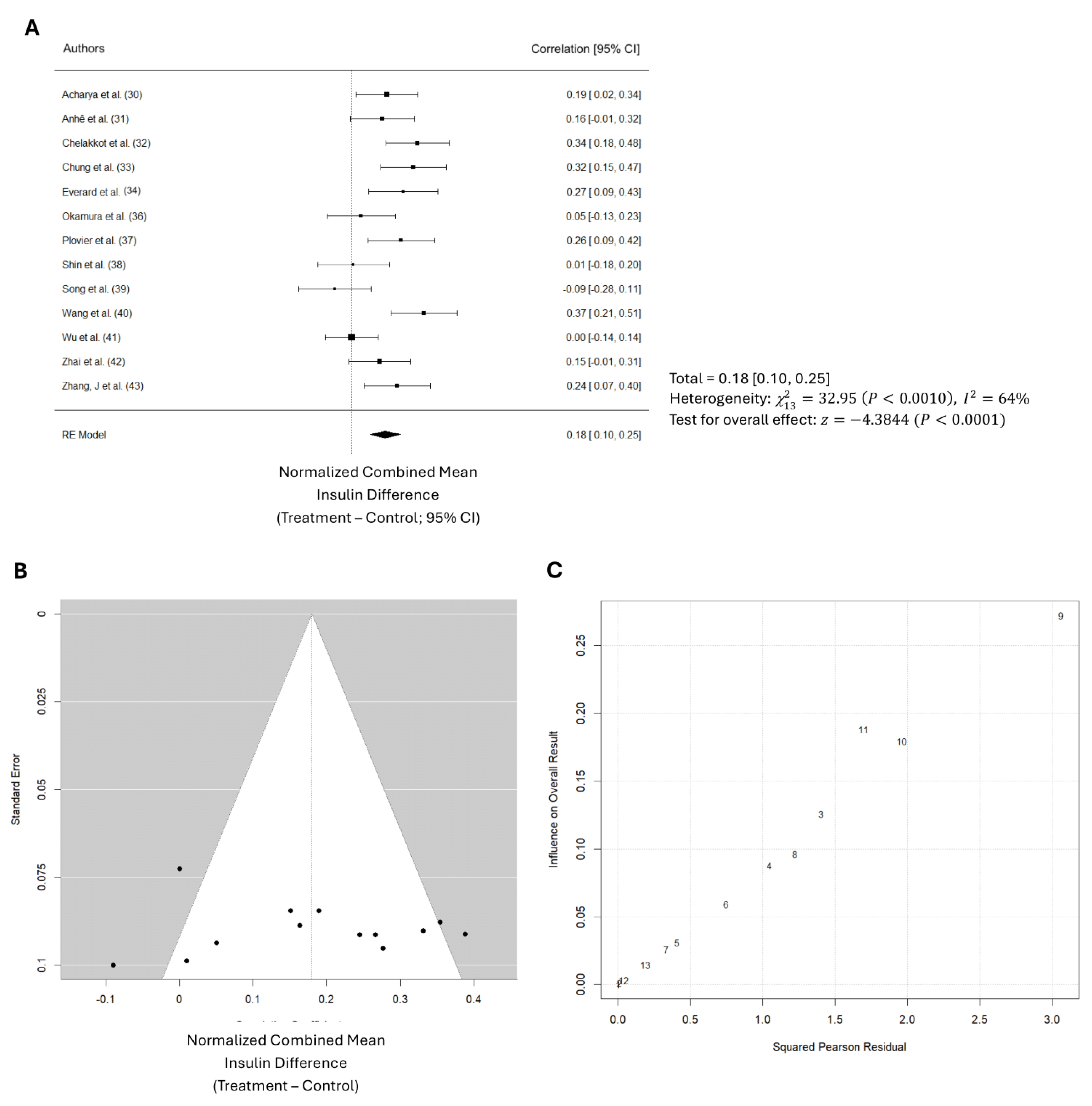

Impact of Akk on Blood Insulin

Thirteen studies examined circulating insulin hormone levels. As shown in

Table 6, the total number of participants in the control groups across all studies is 168, versus 200 in the treatment groups. The data suggest that Akk treatment stimulated blood insulin production in the animals by 26.9%, as shown by the higher mean level of 2.6 µIU/mL in the treatment groups compared to 1.9 µIU/mL in the control groups. The normalized effect sizes vary across studies, with most studies showing positive effect sizes, suggesting that the treatment generally had a beneficial effect. Nevertheless, only 7 of 13 studies showed that the effect was significant. The weighted mean effect size of 0.827 with a confidence interval of 0.10 to 0.25 indicates a statistically significant reduction in blood glucose levels due to Akk treatment. The forest plot also revealed a significant increase in blood insulin levels in animals administered Akk compared to controls (p < 0.001) as shown in

Figure 6A. The analysis showed a pooled effect size of 0.18 (95% confidence interval: 0.10 – 0.25). There was also significant variation in the study results (I² = 64%). Additionally, analysis suggests a potential publication bias (

Figure 6B). These results suggest that the studies by Shin et al., Song et al., and Wang et al. contributed the most to the observed heterogeneity (

Figure 6C).

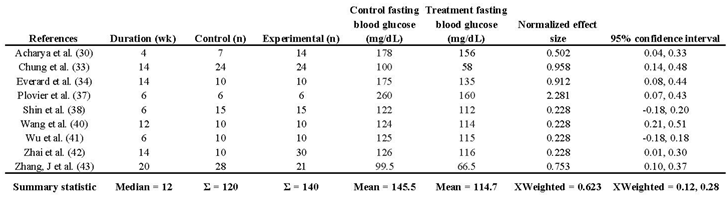

Impact of Akk on Fasting Blood Glucose

Nine studies investigated the impact of Akk on fasting blood glucose levels. Details on these assessment methods can be found in

Table 7. The analysis revealed that Akk treatment significantly reduced fasting blood glucose levels by 21.2%, as shown by the lower mean level of 114.7 mg/dL in the treatment groups compared to 145.5 mg/dL in the control groups. The normalized effect sizes vary across studies, with most studies showing positive effect sizes, suggesting that the treatment generally had a beneficial effect. Seven of 9 studies showed that the effect was significant. The weighted mean effect size of 0.623 with a confidence interval of 0.12 to 0.28 indicates a statistically significant reduction in blood glucose levels due to Akk treatment. The forest plot also revealed a significant increase in blood insulin levels in animals administered Akk compared to controls (p < 0.001) as shown in Figure 7A. The analysis showed a pooled effect size of 0.20 (95% confidence interval: 0.12 – 0.28). There was signficant variation in the study results (I² = 52%). The analysis suggests a low risk of publication bias, indicating a fair representation of both positive and negative findings (Figure 7B). Three studies by Shin et al. (study 5), Wang et al. (study 6), and Wu et al. (Study 7) contributed the most to the observed heterogeneity (Figure 7C).

4. Discussion

This meta-analysis underscores the multifaceted benefits of Akk intake in mice subjected to a high-fat diet. Overall, dietary supplementation with Akk, as analyzed from nine selected studies, significantly reduced body weight by an average of 10.4%. The dosage of Akk ranged from 2x108 to 5x1010 CFU/day, which aligns with the dosages commonly used in most probiotic animal studies. Most of the selected studies on Akk used dosages of 2x108 and 1x 1010 CFU. However, two studies by Wang et al. (40) and Zhang et al. (43) utilized a higher dose of 5x1010 CFU in mice. Interestingly, both studies showed that Akk had no effect on body weight, despite other studies with lower doses showing a beneficial effect in reducing body weight gain. These results suggest that there is no dose-dependent relationship of Akk in the prevention of body weight gain. The median duration of Akk treatment across the selected nine animal studies was 14 weeks, ranging from 6 to 20 weeks. The most prominent effects of Akk were observed during treatment durations of 6 to 12 weeks. The results suggest that Akk exerts its effect in reducing body weight gain during the early stages of obesity development (as early as 6 weeks), with the probiotic effect likely diminishing over time. For instance, Zhang’s study (43) extended Akk treatment to 20 weeks at higher dose, but showed no inhibiting effect on body weight gain. Obesity is a chronic disease that requires a long-term solution. The current animal studies were all of short duration (less than 20 weeks). Long-term studies are needed to verify Akk’s effect on obesity development.

The effect of Akk supplementation on the prevention of type 2 diabetes is reflected in its significant reduction of fasting blood glucose (by 21.2%) and improvement in glucose tolerance (by 22.1%), suggesting that Akk treatment is effective in preventing type 2 diabetes. Nine studies have measured fasting blood glucose. Except for two studies, all others showed a significant reduction in fasting blood glucose with Akk treatment. These two studies had a short treatment duration of 6 weeks, while the others were longer, suggesting that Akk may require more than 6 weeks to demonstrate a significant effect on blood glucose. No dose-response relationship was observed across the tested doses between 2x10

8 to 5x10

10 CFU/day in the nine studies. It was unclear if and how treatment duration affected the efficiency of the probiotic during administration. Additionally, a discrepancy emerged regarding the inclusion of antibiotics, which was the predominant method. In Acharya et al. study, the administration of the antibiotic before the probiotic was actually more effective than administering the probiotic by itself [

30]. Few authors provided clear justifications for the model choice and dosing parameters utilized in their studies.

Nine studies have measured glucose tolerance. The meta-analysis showed that Akk significantly improved glucose tolerance in mice by reducing the 2-hour AUC by 22.1%. However, there was substantial variation in the results across studies, as reflected by I² = 73%. Indeed, six of nine studies showed modest but no significant effect. The median duration of Akk treatment across studies was 12 weeks, ranging from 6 to 16 weeks. Shin et al. found that six weeks of Akk treatment significantly reduced DIO mice 2-hour AUC by an estimated 27.3%. This mice study of Akk treatment showed the most prominent effect among the studies with a normalized effect size of 0.856. Plovier et al. also investigated six weeks of Akk treatment on mice glucose tolerance but with a lower dose (2x108 CFU/d versus 1x1010 CFU/d in Shin’s study) and found no significant effect. The other two studies with significant effects by Akk treatment also used doses at or above 1x 1010CFU/d, suggesting that the Akk treatment dose may need to be no less than 1x1010 CFU/d to be effective. It should be noted that one study by Wang et al. used a model of FFAR4 knockout mice, which has been shown to cause severely impaired glucose tolerance under high-fat feeding conditions. FFAR4 regulates glucagon-like peptide 1 secretion by modifying Akk abundance. However, our meta-analysis showed that Akk treatment at 5x 1010 CFU/d for 12 weeks in Wang’s study did not significantly improve glucose tolerance. There is substantial heterogeneity among the studies. The studies differ in terms of doses, duration, sample size, and other factors, which could significantly influence the results. Further research is needed to confirm the consistency and magnitude of the effect of Akk on glucose tolerance.

Thirteen studies investigated the effect of Akk treatment on blood insulin levels in animals. The meta-analysis revealed a significant increase in blood insulin levels, from 1.9 to 2.6 µg/mL. Notably, three studies—Zhang et al., Chung et al., and Zhai et al.—demonstrated strong treatment effects, with effect sizes of 1.64, 1.44, and 1.17, respectively. Interestingly, all three studies also reported significant reductions in fasting blood glucose levels. Additionally, some studies explored the anti-inflammatory efficacy of Akk; however, due to the heterogeneity of inflammation biomarkers across blood and tissue, a meta-analysis on the anti-inflammatory effects was not feasible.

One of the primary objectives of this meta-analysis is to identify the variables that contribute to the efficacy of Akk, such as changes in body weight and treatment duration. Surprisingly, the meta-regression models are not able to determine these expected variables. Notably, treatment duration which has been a critical determinant of efficacy in previous studies (both preclinical and clinical), did not emerge as a significant factor in our analysis [

20,

28]. This discrepancy might be due to the limited exploration of treatment durations in the analyzed studies. Only one study specifically investigated the impact of different treatment durations, reporting no significant effect of the probiotic beyond 14 weeks [

18].

There are several limitations leads to inclusive results in our meta-regression models. First, the total number of Akk studies are limited to reach the requirement for meta-regression models analysis [

45]. Indeed, the limited number of studies assessing fasting blood glucose levels restricted our ability to conduct a comprehensive meta-regression due to constraints in degrees of freedom. Second, the presence of substantial variability among studies can compromise the power of meta-regression. Our analysis revealed significant variation between studies, as indicated by heterogeneity statistics in our primary endpoints model. This could be due to factors such as system errors among different laboratories, such as experiment duration, sample preparation, and administration parameters of Akk. The animal models used (age, sex, and species) were inconsistent. This significant methodological and model variability among the studies made it challenging to identify clear cause-and-effect relationships. Moreover, the inconclusive results regarding microbiota suggest that Akk’s influence on gut microbiota might be more critical than its direct metabolic effects on parameters such as blood glucose levels. On the other hand, the current data make it difficult to definitively determine the key factors influencing treatment outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Translational preclinical studies aim to develop and test treatments for eventual use in patients [

45]. Given the increasing prevalence of metabolic morbidities such as type 2 diabetes and diet-induced obesity, our objective was to assess whether a novel probiotic, Akk, could mitigate these metabolic diseases in animal models. Our findings indicate that Akk effectively reduces the development of type 2 diabetes and diet-induced obesity. Given that age, sex, comorbidities, and treatment duration can influence treatment outcomes [

27,

45], future studies should incorporate these factors into their design and employ comprehensive, long-term outcome assessments to provide a more complete understanding of Akk's effects on body weight and type 2 diabetes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ethan Liu, Xiangming Ji and Kequan Zhou; Data curation, Ethan Liu; Formal analysis, Ethan Liu and Kequan Zhou; Investigation, Ethan Liu and Kequan Zhou; Methodology, Ethan Liu, Xiangming Ji and Kequan Zhou; Project administration, Kequan Zhou; Resources, Kequan Zhou; Software, Ethan Liu; Supervision, Kequan Zhou; Validation, Ethan Liu and Kequan Zhou; Visualization, Kequan Zhou; Writing – original draft, Ethan Liu and Kequan Zhou; Writing – review & editing, Ethan Liu, Xiangming Ji and Kequan Zhou.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Hu, F.B. Epidemiology of Obesity and Diabetes and Their Cardiovascular Complications. Circ Res 2016, 118, 1723–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, N.; Tan, H.Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Y. Function of Akkermansia muciniphila in Obesity: Interactions With Lipid Metabolism, Immune Response and Gut Systems. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, M.C.; Everard, A.; Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Sokolovska, N.; Prifti, E.; Verger, E.O.; Kayser, B.D.; Levenez, F.; Chilloux, J.; Hoyles, L.; et al. Akkermansia muciniphila and Improved Metabolic Health During a Dietary Intervention in Obesity: Relationship with Gut Microbiome Richness and Ecology. Gut 2016, 65, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslanian, S.; Bacha, F.; Grey, M.; Marcus, M.D.; White, N.H.; Zeitler, P. Evaluation and Management of Youth-Onset Type 2 Diabetes: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2648–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harsch, I.A.; Konturek, P.C. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Obesity and Type 2 and Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: New Insights into "Old" Diseases. Med Sci (Basel) 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, R.M.C.; Simplício-Filho, A.; Sávio-Silva, C.; Oliveira, L.F.V.; Cruz, G.N.F.; Sousa, E.H.; Noronha, I.L.; Mangueira, C.L.P.; Quaglierini-Ribeiro, H.; Josefi-Rocha, G.R.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplant in a Pre-Clinical Model of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Obesity and Diabetic Kidney Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalby, M.J. Questioning the Foundations of the Gut Microbiota and Obesity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2023, 378, 20220221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.N.; Liu, X.T.; Liang, Z.H.; Wang, J.H. Gut Microbiota in Obesity. World J Gastroenterol 2021, 27, 3837–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crovesy, L.; Masterson, D.; Rosado, E.L. Profile of the Gut Microbiota of Adults With Obesity: A Systematic Review. Eur J Clin Nutr 2020, 74, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malesza, I.J.; Malesza, M.; Walkowiak, J.; Mussin, N.; Walkowiak, D.; Aringazina, R.; Bartkowiak-Wieczorek, J.; Mądry, E. High-Fat, Western-Style Diet, Systemic Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota: A Narrative Review. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bander, Z.; Nitert, M.D.; Mousa, A.; Naderpoor, N. The Gut Microbiota and Inflammation: An Overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Xin, Y. Function of Akkermansia muciniphila in Type 2 Diabetes and Related Diseases. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1172400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamzin, A.M.; Ropot, A.V.; Sergeyev, O.V.; Sechenov, E.O.K. Akkermansia muciniphila and Host Interaction Within the Intestinal Tract. Anaerobe 2021, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aron, R.A.C.; Abid, A.; Vesa, C.M.; Nechifor, A.C.; Behl, T.; Ghitea, T.C.; Munteanu, M.A.; Fratila, O.; Andronie-Cioara, F.L.; Toma, M.M.; et al. Recognizing the Benefits of Pre-/Probiotics in Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Considering the Influence of Akkermansia muciniphila as a Key Gut Bacterium. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, J.; Kang, H.; You, H.J.; Ko, G. Revisiting the Role of Akkermansia muciniphila as a Therapeutic Bacterium. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2078619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, S.; van Zuydam, N.R.; Mahajan, A.; Kurilshikov, A.; Vich Vila, A.; Võsa, U.; Mujagic, Z.; Masclee, A.A.M.; Jonkers, D.; Oosting, M.; et al. Causal Relationships Among the Gut Microbiome, Short-chain Fatty Acids and Metabolic Diseases. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, R.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Klein, S.; Gordon, J.I. Microbial Ecology: Human Gut Microbes Associated With Obesity. Nature 2006, 444, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Bmj 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.T.B.; Wu, K.C.; Hsu, J.L.; Chang, C.S.; Chou, C.; Lin, C.Y.; Liao, Y.M.; Lin, P.C.; Yang, L.Y.; Lin, H.W. Effects of Non-insulin Anti-hyperglycemic Agents on Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review on Human and Animal Studies. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajewicz, N.; Komarova, S.V. Meta-Analytic Methodology for Basic Research: A Practical Guide. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying Heterogeneity in a Meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, C.B.; Mazumdar, M. Operating Characteristics of a Rank Correlation Test for Publication Bias. Biometrics 1994, 50, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in Meta-analysis Detected by a Simple, Graphical Test. Bmj 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W.; López-López, J.A.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Marín-Martínez, F. A Comparison of Procedures to Test for Moderators in Mixed-effects Meta-regression Models. Psychol Methods 2015, 20, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, S.K.; Lawrence, C.B. Comorbidity and Age in the Modelling of Stroke: Are We Still Failing to Consider the Characteristics of Stroke Patients? BMJ Open Sci 2020, 4, e100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, N.; Reunanen, J.; Meijerink, M.; Pietilä, T.E.; Kainulainen, V.; Klievink, J.; Huuskonen, L.; Aalvink, S.; Skurnik, M.; Boeren, S.; et al. Pili-like Proteins of Akkermansia muciniphila Modulate Host Immune Responses and Gut Barrier Function. PLoS One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meldrum, D.R.; Morris, M.A.; Gambone, J.C. Obesity Pandemic: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions-but Do we Have the Will? Fertil Steril 2017, 107, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in Clinical Trials. Control Clin Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, L.J.; Ralhan, S.; Ward, D.L.; Colbourne, F. Translational Intracerebral Hemorrhage Research: Has Current Neuroprotection Research ARRIVEd at a Standard for Experimental Design and Reporting? Transl Stroke Res 2020, 11, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, K.D.; Friedline, R.H.; Ward, D.V.; Graham, M.E.; Tauer, L.; Zheng, D.; Hu, X.; de Vos, W.M.; McCormick, B.A.; Kim, J.K.; et al. Differential Effects of Akkermansia-enriched Fecal Microbiota Transplant on Energy Balance in Female Mice on High-fat Diet. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anhê, F.F.; Roy, D.; Pilon, G.; Dudonné, S.; Matamoros, S.; Varin, T.V.; Garofalo, C.; Moine, Q.; Desjardins, Y.; Levy, E.; et al. A Polyphenol-rich Cranberry Extract Protects From Diet-induced Obesity, Insulin Resistance and Intestinal Inflammation in Association With Increased Akkermansia spp. Population in the Gut Microbiota of Mice. Gut 2015, 64, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelakkot, C.; Choi, Y.; Kim, D.K.; Park, H.T.; Ghim, J.; Kwon, Y.; Jeon, J.; Kim, M.S.; Jee, Y.K.; Gho, Y.S.; et al. Akkermansia muciniphila-derived Extracellular Vesicles Influence Gut Permeability Through the Regulation of Tight Junctions. Experimental and Molecular Medicine 2018, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, E.; Elmassry, M.M.; Kottapalli, P.; Kottapalli, K.R.; Kaur, G.; Dufour, J.M.; Wright, K.; Ramalingam, L.; Moustaid-Moussa, N.; Wang, R.; et al. Metabolic Benefits of Annatto-extracted Tocotrienol on Glucose Homeostasis, Inflammation, and Gut Microbiome. Nutrition Research 2020, 77, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everard, A.; Belzer, C.; Geurts, L.; Ouwerkerk, J.P.; Druart, C.; Bindels, L.B.; Guiot, Y.; Derrien, M.; Muccioli, G.G.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. Cross-talk Between Akkermansia muciniphila and Intestinal Epithelium Controls Diet-induced Obesity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013, 110, 9066–9071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hänninen, A.; Toivonen, R.; Pöysti, S.; Belzer, C.; Plovier, H.; Ouwerkerk, J.P.; Emani, R.; Cani, P.D.; De Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila Induces Gut Microbiota Remodelling and Controls Islet Autoimmunity in NOD Mice. Gut 2018, 67, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, T.; Hamaguchi, M.; Nakajima, H.; Kitagawa, N.; Majima, S.; Senmaru, T.; Okada, H.; Ushigome, E.; Nakanishi, N.; Sasano, R.; et al. Milk Protects Against Sarcopenic Obesity Due to Increase in the Genus Akkermansia in Faeces of db/db Mice. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 2023, 14, 1395–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plovier, H.; Everard, A.; Druart, C.; Depommier, C.; Van Hul, M.; Geurts, L.; Chilloux, J.; Ottman, N.; Duparc, T.; Lichtenstein, L.; et al. A Purified Membrane Protein From Akkermansia muciniphila or the Pasteurized Bacterium Improves Metabolism in Obese and Diabetic Mice. Nat Med 2017, 23, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.R.; Lee, J.C.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Whon, T.W.; Lee, M.S.; Bae, J.W. An Increase in the Akkermansia spp. Population Induced by Metformin Treatment Improves Glucose Homeostasis in Diet-induced Obese Mice. Gut 2014, 63, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.Z.; Chu, Q.; Yan, F.J.; Yang, Y.Y.; Han, W.; Zheng, X.D. Red Pitaya Betacyanins Protects From Diet-induced Obesity, Liver Steatosis and Insulin Resistance in Association With Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Mice. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2016, 31, 1462–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Cui, S.; Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.Q.; Zhu, S.L. Akkermansia muciniphila Supplementation Improves Glucose Tolerance in Intestinal Ffar4 Knockout Mice During the Daily Light to Dark Transition. mSystems 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Guo, X.; Zhang, M.; Ou, Z.; Wu, D.; Deng, L.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Deng, G.; Chen, S.; et al. An Akkermansia muciniphila Subtype Alleviates High-fat Diet-induced Metabolic Disorders and Inhibits the Neurodegenerative Process in Mice. Anaerobe 2020, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, R.; Xue, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, C. Strain-specific Anti-inflammatory Properties of Two Akkermansia muciniphila Strains on Chronic Colitis in Mice. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ni, Y.; Qian, L.; Fang, Q.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, M.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, J.; Hou, X.; et al. Decreased Abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila Leads to the Impairment of Insulin Secretion and Glucose Homeostasis in Lean Type 2 Diabetes. Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany) 2021, 8, e2100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Qin, Q.Q.; Liu, M.N.; Zhang, X.L.; He, F.; Wang, G.Q. Akkermansia muciniphila can Reduce the Damage of Gluco/lipotoxicity, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation, and Normalize Intestine Microbiota in Streptozotocin-induced Diabetic Rats. Pathogens and Disease 2018, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langan, D.; Higgins, J.P.; Gregory, W.; Sutton, A.J. Graphical Augmentations to the Funnel Plot Assess the Impact of Additional Evidence on a Meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2012, 65, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Characteristics of enrolled studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of enrolled studies.

Table 2.

Methodological quality scale reporting elements for Akkermansia muciniphila research in type 2 diabetes and obesity and percentage adherence.

Table 2.

Methodological quality scale reporting elements for Akkermansia muciniphila research in type 2 diabetes and obesity and percentage adherence.

Table 3.

Statistical summary comparison and total percentage of reported MQS elements (✓ = yes, ✗ = no).

Table 3.

Statistical summary comparison and total percentage of reported MQS elements (✓ = yes, ✗ = no).

Table 4.

Descriptive characteristics of studies that assessed body Weight.

Table 4.

Descriptive characteristics of studies that assessed body Weight.

Table 5.

Descriptive characteristics of studies that assessed glucose tolerance.

Table 5.

Descriptive characteristics of studies that assessed glucose tolerance.

Table 6.

Descriptive characteristics of studies that assessed blood insulin.

Table 6.

Descriptive characteristics of studies that assessed blood insulin.

Table 7.

Descriptive characteristics of studies that assessed fasting blood glucose levels.

Table 7.

Descriptive characteristics of studies that assessed fasting blood glucose levels.

Figure 2.

Selection of studies for meta-analysis.

Figure 2.

Selection of studies for meta-analysis.

Figure 3.

Analysis of experimental characteristics used in animal models for A. muciniphila studies. (A): Breakdown of diets used in animal studies. (B): Animal sexes used in mouse animal studies. (C): Evaluation of methodological quality score for animal studies (max score = 12). MQS, Methodological Quality Score.

Figure 3.

Analysis of experimental characteristics used in animal models for A. muciniphila studies. (A): Breakdown of diets used in animal studies. (B): Animal sexes used in mouse animal studies. (C): Evaluation of methodological quality score for animal studies (max score = 12). MQS, Methodological Quality Score.

Figure 4.

Quantitative analysis of studies that assessed body weight using random-effects meta-analysis. (A): Forest plot of studies investigating body weight effects (normalized mean difference 95% CI). Effect size estimates were heterogenous, likely owning to study design differences. (B): Funnel plot used to assess publication bias. These results suggest that the studies used in the meta-analysis had relatively low publication bias (i.e., the symmetric distribution of closed circles). (C): Baujat plot used to assess the studies that contributed most to heterogeneity. These results suggest that studies Chung et al. (study 3) and Wu et al. (study 7) likely had moderating variables that contributed the most to the heterogeneity.

Figure 4.

Quantitative analysis of studies that assessed body weight using random-effects meta-analysis. (A): Forest plot of studies investigating body weight effects (normalized mean difference 95% CI). Effect size estimates were heterogenous, likely owning to study design differences. (B): Funnel plot used to assess publication bias. These results suggest that the studies used in the meta-analysis had relatively low publication bias (i.e., the symmetric distribution of closed circles). (C): Baujat plot used to assess the studies that contributed most to heterogeneity. These results suggest that studies Chung et al. (study 3) and Wu et al. (study 7) likely had moderating variables that contributed the most to the heterogeneity.

Figure 5.

Quantitative analysis of studies that assessed glucose tolerance using random-effects meta-analysis. (A): Forest plot of studies investigating glucose tolerance (normalized mean difference 95% CI). Effect size estimates were heterogenous, likely owning to study design differences. (B): Funnel plot used to assess publication bias. These results suggest that the studies used in the meta-analysis had relatively low publication bias. (C): Baujat plot used to assess the studies that contributed most to heterogeneity. These results suggest that the study Shin et al. (study 6) likely had moderating variables that contributed the most to the heterogeneity.

Figure 5.

Quantitative analysis of studies that assessed glucose tolerance using random-effects meta-analysis. (A): Forest plot of studies investigating glucose tolerance (normalized mean difference 95% CI). Effect size estimates were heterogenous, likely owning to study design differences. (B): Funnel plot used to assess publication bias. These results suggest that the studies used in the meta-analysis had relatively low publication bias. (C): Baujat plot used to assess the studies that contributed most to heterogeneity. These results suggest that the study Shin et al. (study 6) likely had moderating variables that contributed the most to the heterogeneity.

Figure 6.

Quantitative analysis of studies that assessed insulin hormone levels using random-effects meta-analysis. (A): Forest plot of studies investigating insulin levels (normalized mean difference 95% CI). Effect size estimates were very heterogenous, likely owning to study design differences and differences in probiotic duration. (B): Funnel plot used to assess publication bias. These results suggest that the studies used in the meta-analysis had relatively low publication bias. (C): Baujat plot used to assess the studies that contributed most to heterogeneity. These results suggest that studies Shin et al. (Study 9), Song et al. (study 10), and Wang et al. (study 11) likely had moderating variables that contributed the most to the heterogeneity.

Figure 6.

Quantitative analysis of studies that assessed insulin hormone levels using random-effects meta-analysis. (A): Forest plot of studies investigating insulin levels (normalized mean difference 95% CI). Effect size estimates were very heterogenous, likely owning to study design differences and differences in probiotic duration. (B): Funnel plot used to assess publication bias. These results suggest that the studies used in the meta-analysis had relatively low publication bias. (C): Baujat plot used to assess the studies that contributed most to heterogeneity. These results suggest that studies Shin et al. (Study 9), Song et al. (study 10), and Wang et al. (study 11) likely had moderating variables that contributed the most to the heterogeneity.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).