Submitted:

20 August 2024

Posted:

21 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Analisys

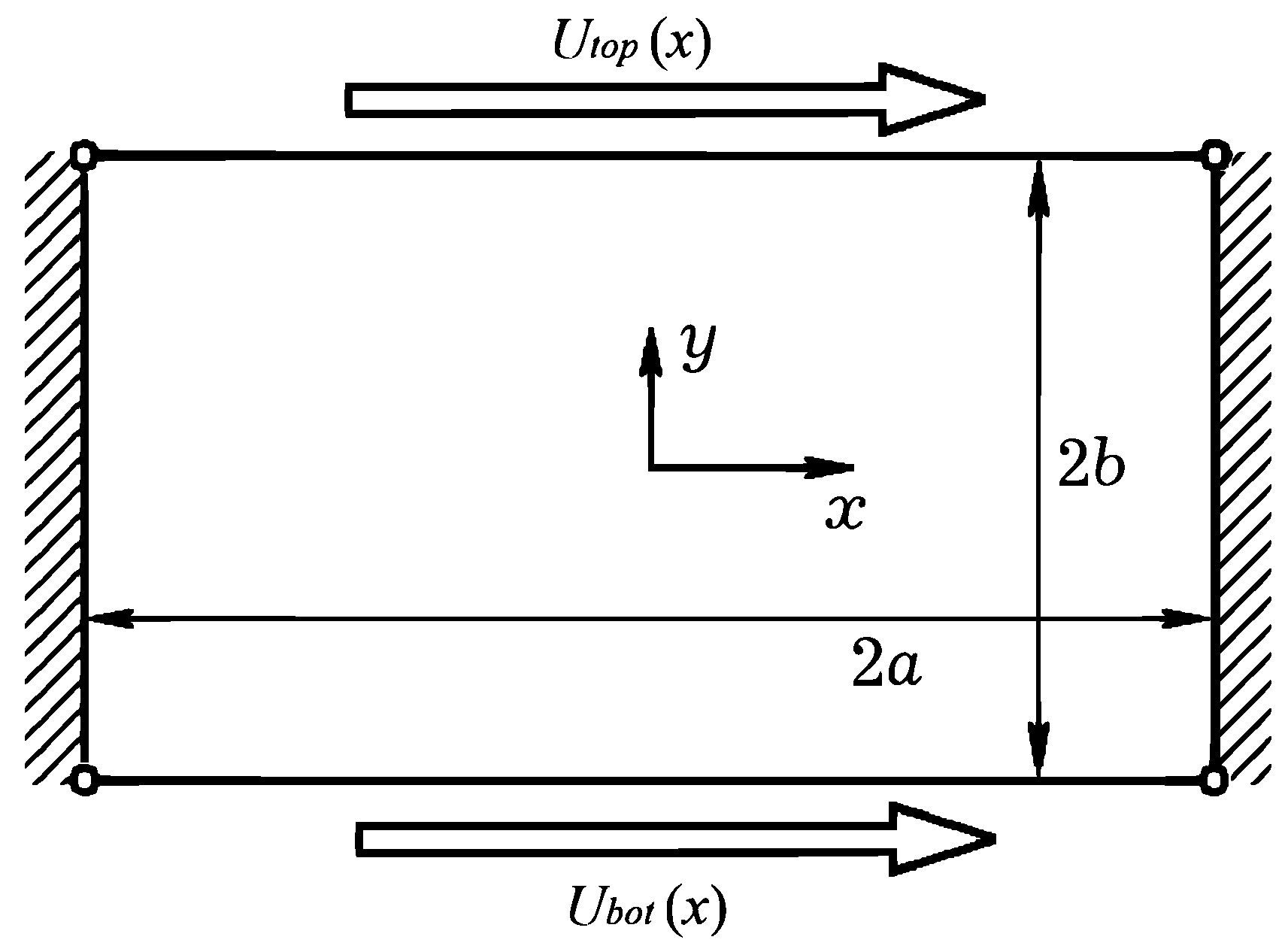

3. Analytical Determination of the Velocity Field of a Flow of a Viscous Fluid in a Rectangular Cavity

3.1. The Equation of Motion of a Viscous Fluid in the Stokes Approximation

3.2. Stokes Flow in a Rectangular Cavity

3.2.1. Construction of a Solution to a Symmetric Problem with Constant Velocities

3.2.2. Construction of a Solution to an Antisymmetric Problem with Constant Velocities

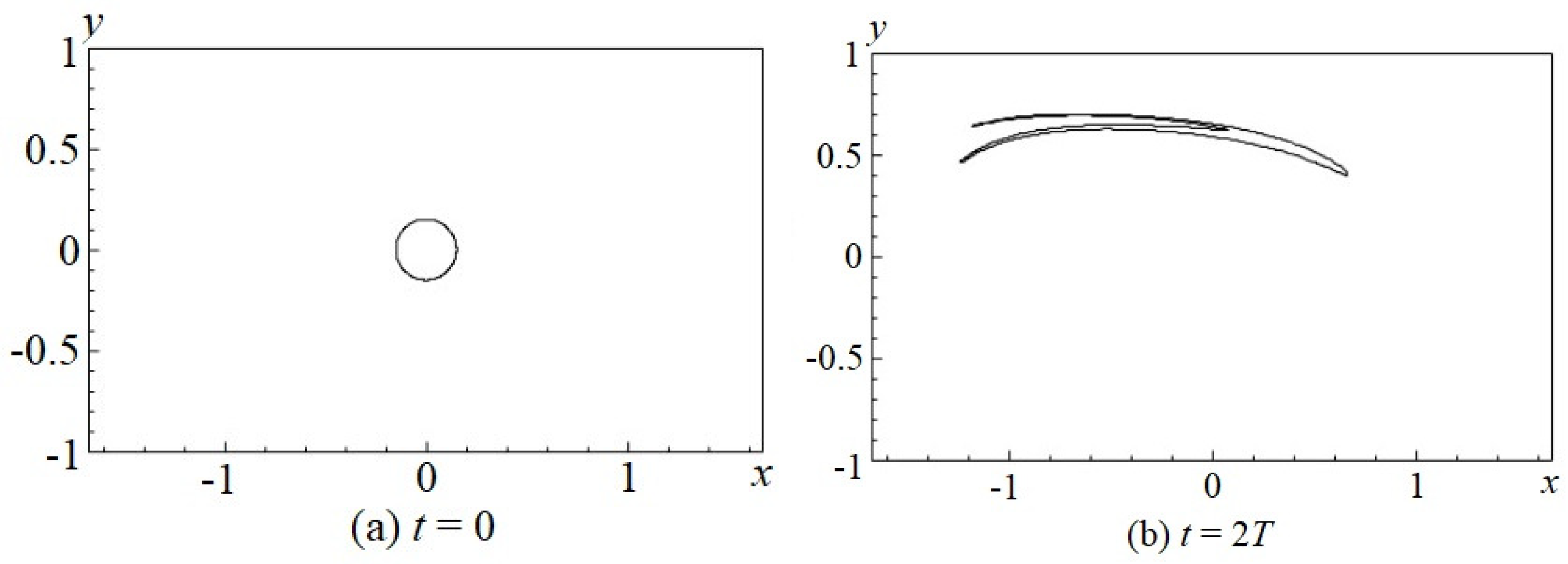

4. Advection of Fluid

4.1. Advection Equations of a Moving Fluid Particle

4.2. Numerical Modeling of Closed Loop Advection Process

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aref, H. Stirring by chaotic advection. Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 1984, 143, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre, A. , Mota, J.P.B., Rodrigo, A.J.S., Saatdjian, E. Chaotic advection and heat transfer enhancement in Stokes flows. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow 2003, 24(3), 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Woude, D. , Clercx, H.J.H., Van Heijst, G.J.F., Veleshko, V.V. Stokes flow in a rectangular cavity by rotlet forcing. Physics of Fluids 2007, 19(8). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. , Zumbrunnen, D.A. Chaotic mixing of two similar fluids in the presence of a third dissimilar fluid. AIChE Journal 1996, 42, 3301–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyland, P.L. , Aref, H., Stremler, M.A. Topological fluid mechanics of stirring. Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 2000, 403, 277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikhansky, A. Chaotic advection of finite-size bodies in a cavity flow. Physic of Fluids 2003, 15(7), 1830–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, M. , Shirani, E., Jarrahi, H., Peerhossaini, H. Mixing by Time-Dependent Orbits in Spatiotemporal Chaotic Advection. J. Fluids Eng. 2015; 127, 13p, 011201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, D.J., Adrian, R.J., Olsen, M.G., Stremler, M.A., Aref, H., Jo, B.H. Passive mixing in microchannels: Fabrication and flow experiments. Mécanique and Industries. 2001, 2(4), 343–348.

- Gorban, N.V. , Kapustyan, A.V., Kapustyan, E.A., Khomenko, O.V. Strong Global Attractor for the Three-Dimensional Navier-Stokes System of Equations in Unbounded Domain of Channel Type. Journal of Automation and Information Sciences. 2015; 47, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianlei Lin, Zhiguo Yang, Suchuan Dong. Numerical approximation of incompressible Navier-Stokes equations based on an auxiliary energy variable. Journal of Computational Physics. 2019, 388, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourjii, A.A. , Meleshko, V.V., van Heijst, G.J.F. Method of the Piece-Spline Interpolation in the Advection Problem for an Arbitrary Velocity Field. Dop. AN Ukrainy. 1996, 8, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ottino, J.M. , Leong, C.W. Experiments on mixing due to chaotic advection in a cavity. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1989, 209, 463–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.E. Introduction to Mathematical Fluid Dynamics; Dover Publications, New York, USA, 2010; 190 p.

- Milne-Thomson, L.M. Theoretical Hydrodynamics; Dover Publications, 5th ed. Edition, New York, USA, 2013; 768 p.

- Meleshko, V.V. Steady Stokes flow in a rectangular cavity. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 1996, 452(1952), 1999–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleshko, V.V. , Kurylko, O.B., Gourjii, O.A. Generation of topological chaos in the stokes flow in a rectangular cavity. Journal of Mathematical Sciences (United States). 2012, 185(6), 858-871. [CrossRef]

- Sobchuk, V. , Barabash, O., Musienko, A., Tsyganivska, I., Kurylko, O. Mathematical Model of Cyber Risks Management Based on the Expansion of Piecewise Continuous Analytical Approximation Functions of Cyber Attacks in the Fourier Series. Axioms 2023, 12(10), 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomilko, A. , Savytskiy O., Trofymchuk O. Superposition, Eigenfunctions and Orthogonal Polynomials Methods in Elasticity and Acoustic Boundary Value Problems. Kyiv: Naukova dumka. 2016, 436. [Google Scholar]

- Aref, H. The development of chaotic advection. Physics of Fluids. 2002, 14(4), 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref, H. Chaotic advection of fluid particles. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 1990, 333(1631). [CrossRef]

- Sobchuk, V. V. , Zelenska, I. O. Construction of asymptotics of the solution for a system of singularly perturbed equations by the method of essentially singular functions. Bulletin of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. Physics and Mathematics. 2023, 2, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).