Submitted:

18 August 2024

Posted:

21 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Genomics

1.2. Proteomics

1.3. Metabolomics

- ∘

- The resilience of proteomic network structures to minor genetic alterations.

- ∘

- The cumulative effects of mutations on protein-protein interactions and network topology.

- ∘

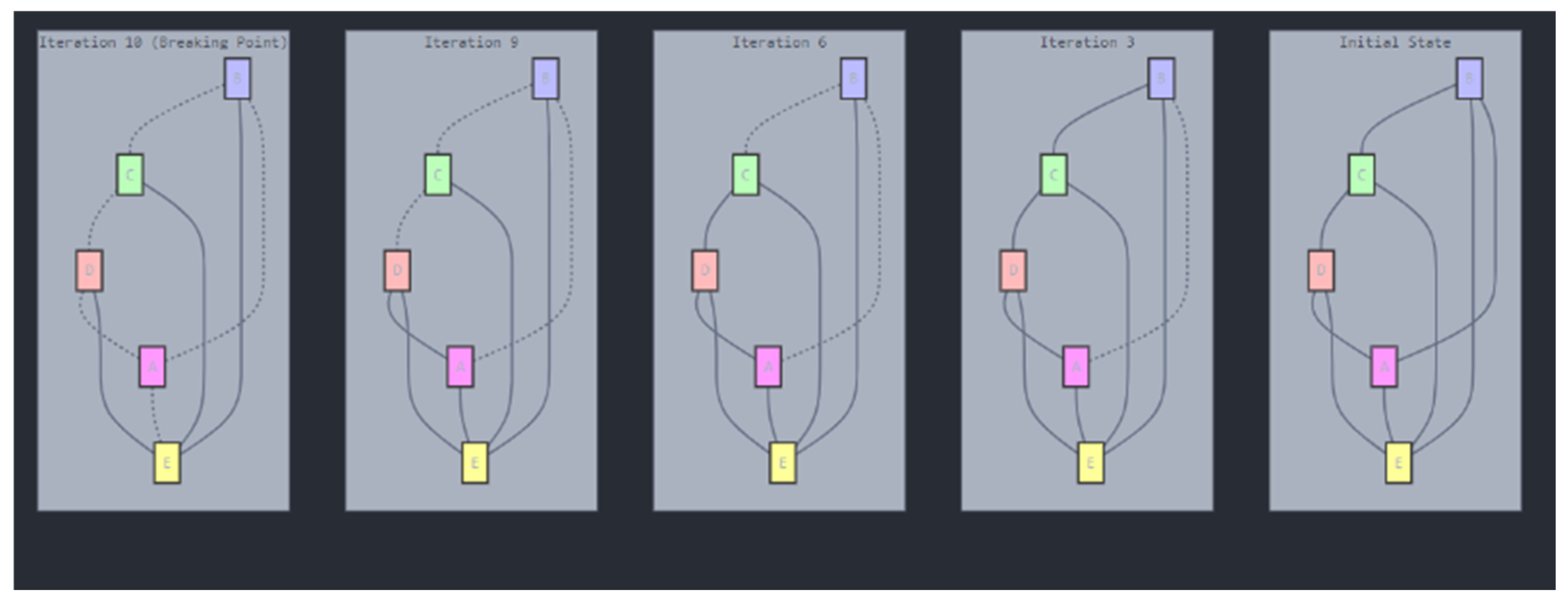

- The identification of critical thresholds or “breakage points” where proteomic networks undergo significant topological changes.

- ∘

- The potential implications of these topological shifts for cellular function and disease progression.

2. Methodology

2.1. Mathematical Formulation

-

Equation (1): Dynamics of ProteinThis equation describes the rate of change of the concentration of Protein . It consists of two terms:

- The term resembles the classic form seen in systems like the Lorenz system, where is a constant parameter.

- The term introduces an interaction between Protein A and the Regulatory Protein W, with being the interaction coefficient.

- 2.

-

Equation (2): Dynamics of Protein BThis equation governs the dynamics of Protein , with three contributing terms:

- : This term involves the interaction between Protein B and Protein A, modulated by , another parameter, and the concentration of Protein .

- : This term represents the natural decay or removal of Protein B.

- : Similar to the previous equation, this term introduces an interaction between Protein B and the Regulatory Protein W.

- 3.

-

Equation (3): Dynamics of Protein CThe dynamics of Protein , are determined by:

- The product , reflecting the interaction between Protein A and Protein B.

- The term accounts for the decay of Protein , where is a parameter.

- : This term introduces the influence of the Regulatory Protein W on Protein C.

- 4.

-

Equation (4): Dynamics of Regulatory Protein WFinally, the equation for the Regulatory Protein W, , involves:

- A combined decay term , representing the interactions between the Regulatory Protein W and each of the Proteins A, B, and C.

Summary

3. Results

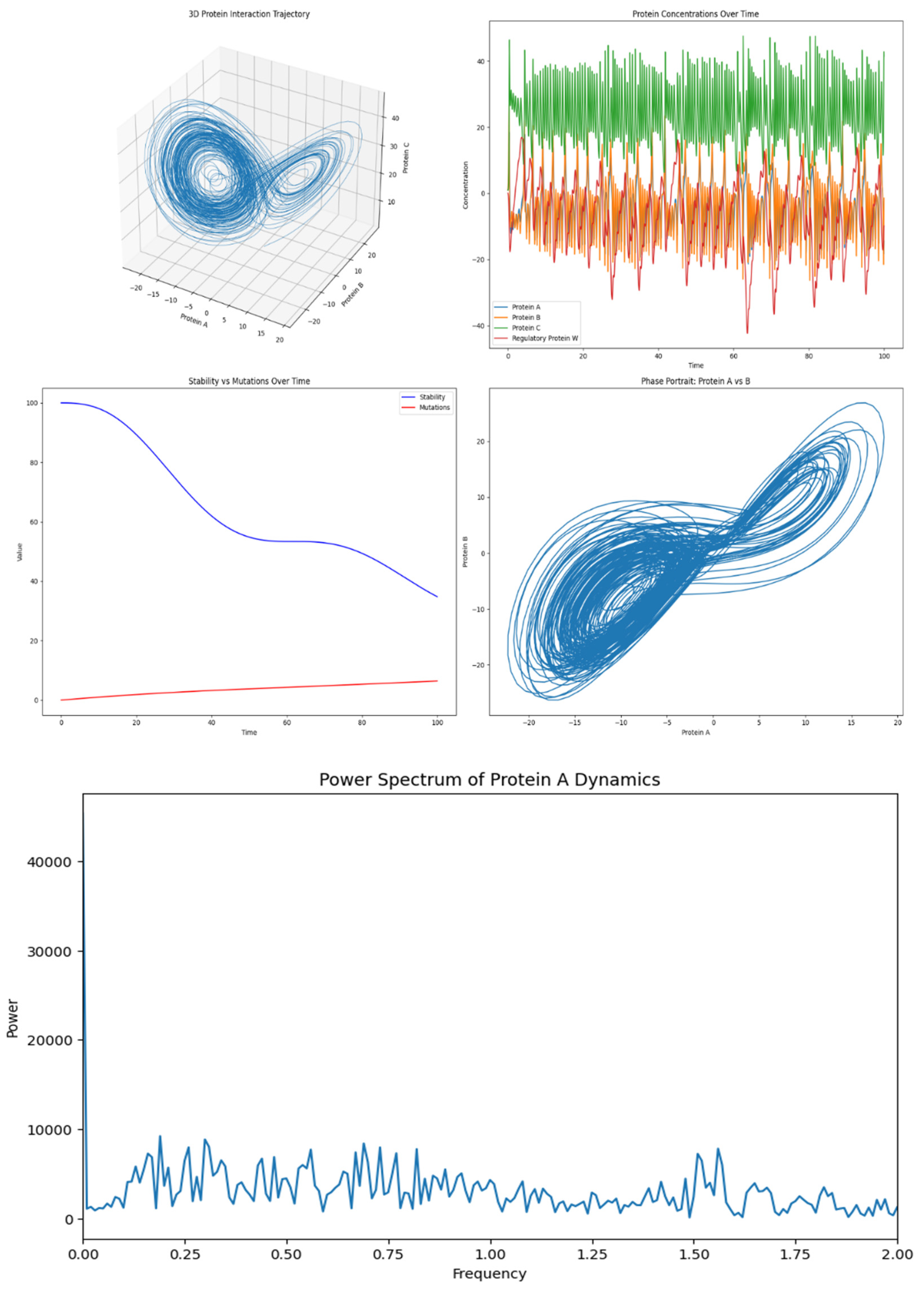

3.1. Protein Interaction Trajectory (Top Left)

- Description: This 3D plot shows the trajectory of the system in the three-dimensional space defined by Protein A (xxx), Protein B (yyy), and Protein C (zzz).

- Interpretation: The trajectory forms a complex shape reminiscent of the Lorenz attractor, which suggests chaotic dynamics in the system. This means that small changes in the initial conditions could lead to drastically different outcomes, but, on the other side, also could mean a buffering for small perturbations, like happens to brain waves in its normal state (Montgomery RM., 2023), making the system sensitive or not to initial states. The shape indicates that the protein concentrations are interdependent and do not settle into a simple steady state or periodic cycle but instead exhibit continuous, non-repeating patterns.

3.2. Protein Concentrations Over Time (Top Right)

- Description: This plot shows the concentrations of the four proteins (A, B, C, and W) over time.

-

Interpretation:

- ∘

- Protein A (blue) and Protein B (orange) exhibit high-frequency oscillations, indicating that they are rapidly fluctuating over time.

- ∘

- Protein C (green) shows larger amplitude oscillations, indicating more substantial changes in its concentration.

- ∘

- Regulatory Protein W (red), on the other hand, seems to oscillate with a lower amplitude, but it still varies significantly, which indicates that it is actively involved in the dynamic interplay among the other proteins.

- This complex, oscillatory behaviour suggests a highly dynamic system where the proteins are continuously influencing each other’s concentrations.

3.3. Stability vs Mutations Over Time (Bottom Left)

- Description: This plot compares the hypothetical stability of the system (blue curve) to the rate of mutations (red curve) over time.

-

Interpretation:

- ∘

- Stability: The blue curve shows a decreasing trend, indicating that the system becomes less stable over time. This could be due to the increasing complexity or variability in the protein interactions as time progresses.

- ∘

- Mutations: The red curve shows a slow increase, suggesting that the mutation rate is gradually rising. This could imply that as the system becomes less stable, there are more opportunities or tendencies for mutations to occur, which could further destabilize the system or lead to new patterns.

3.4. Phase Portrait: Protein A vs B (Bottom Right)

- Description: This phase portrait shows the relationship between the concentrations of Protein A (xxx) and Protein B (yyy) over time.

- Interpretation: The phase portrait again resembles a chaotic attractor (like the Lorenz attractor), which is consistent with the 3D trajectory. It shows that the relationship between Protein A and Protein B is complex and non-linear, with the system exploring a wide range of states rather than settling into a fixed point or a simple limit cycle. This indicates a strong coupling between Protein A and Protein B, where the concentration of one strongly influences the other.

Overall Interpretation

Power Spectrum of Protein A Dynamics

- Frequency Range: The x-axis shows the frequency range from 0 to 2 units. This range corresponds to the various oscillatory components of the Protein A concentration over time.

- Power Distribution: The y-axis shows the power, which indicates how much of the signal’s variance (or “energy”) is associated with each frequency.

- High Peaks: The highest peaks in the lower frequencies indicate that the most significant oscillations occur at these specific frequencies. These frequencies could correspond to the natural oscillatory modes of the system, driven by the interactions between the proteins.

- Low Power at Higher Frequencies: As the frequency increases, the power tends to decrease, which is typical in many natural systems. This suggests that higher-frequency oscillations contribute less to the overall dynamics of Protein A.

4. Discussion

Resilience and Tipping Points in Proteomic Networks

Implications for Genotype-Phenotype Relationships

Evolutionary Perspectives on Proteomic Network Topology

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

5. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aebersold, R.; Mann, M. Mass-spectrometric exploration of proteome structure and function. Nature 2016, 537, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barabási, A.L.; Oltvai, Z.N. Network biology: Understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nature Reviews Genetics 2004, 5, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, E.A. , Li, Y.I.; Pritchard, J.K. An Expanded View of Complex Traits: From Polygenic to Omnigenic. Cell 2017, 169, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, D.N. , Krawczak, M., Polychronakos, C., Tyler-Smith, C.; Kehrer-Sawatzki, H. Where genotype is not predictive of phenotype: Towards an understanding of the molecular basis of reduced penetrance in human inherited disease. Human Genetics 2013, 132, 1077–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiehn, O. Metabolomics—The link between genotypes and phenotypes. Plant Molecular Biology 2002, 48, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, S.J.; Eldredge, N. Punctuated equilibrium comes of age. Nature 1993, 366, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, A.L. Network pharmacology: The next paradigm in drug discovery. Nature Chemical Biology 2008, 4, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karczewski, K.J.; Snyder, M.P. Integrative omics for health and disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 2018, 19, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitano, H. Biological robustness. Nature Reviews Genetics 2004, 5, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, G.C. , Porras, P., Aranda, B., Hermjakob, H.; Orchard, S.E. Analyzing protein-protein interaction networks. Journal of Proteome Research 2012, 11, 2014–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lander, E.S. Initial impact of the sequencing of the human genome. Nature 2011, 470, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, R.M. (2024). Topological Dynamics in Ecological Biomes and Toroidal Structures: Mathematical Models of Stability, Bifurcation, and Structural Failure. August 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijman, S.M. Synthetic lethality: General principles, utility and detection using genetic screens in human cells. FEBS Letters 2011, 585, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, M.D. , Holzinger, E.R., Li, R., Pendergrass, S.A.; Kim, D. Methods of integrating data to uncover genotype-phenotype interactions. Nature Reviews Genetics 2015, 16, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, A. The role of robustness in phenotypic adaptation and innovation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2012, 279, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X. , Cheng, H., Zhang, L., Zhang, J.; Zhu, H. Protein-Protein Interaction Network Analysis and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis in Epilepsy Patients. Medical Science Monitor 2021, 27, e929165. [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S. Emerging applications of metabolomics in drug discovery and precision medicine. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2016, 15, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).