Submitted:

16 August 2024

Posted:

21 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

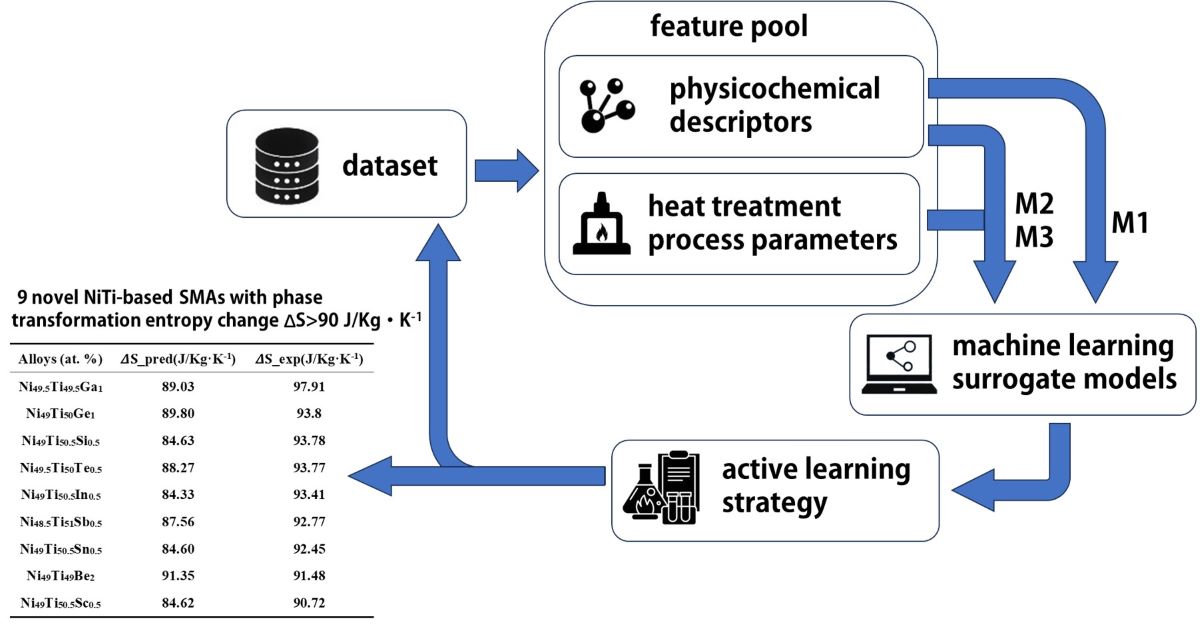

2. Methods

2.1. Datasets and Features

2.2. Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

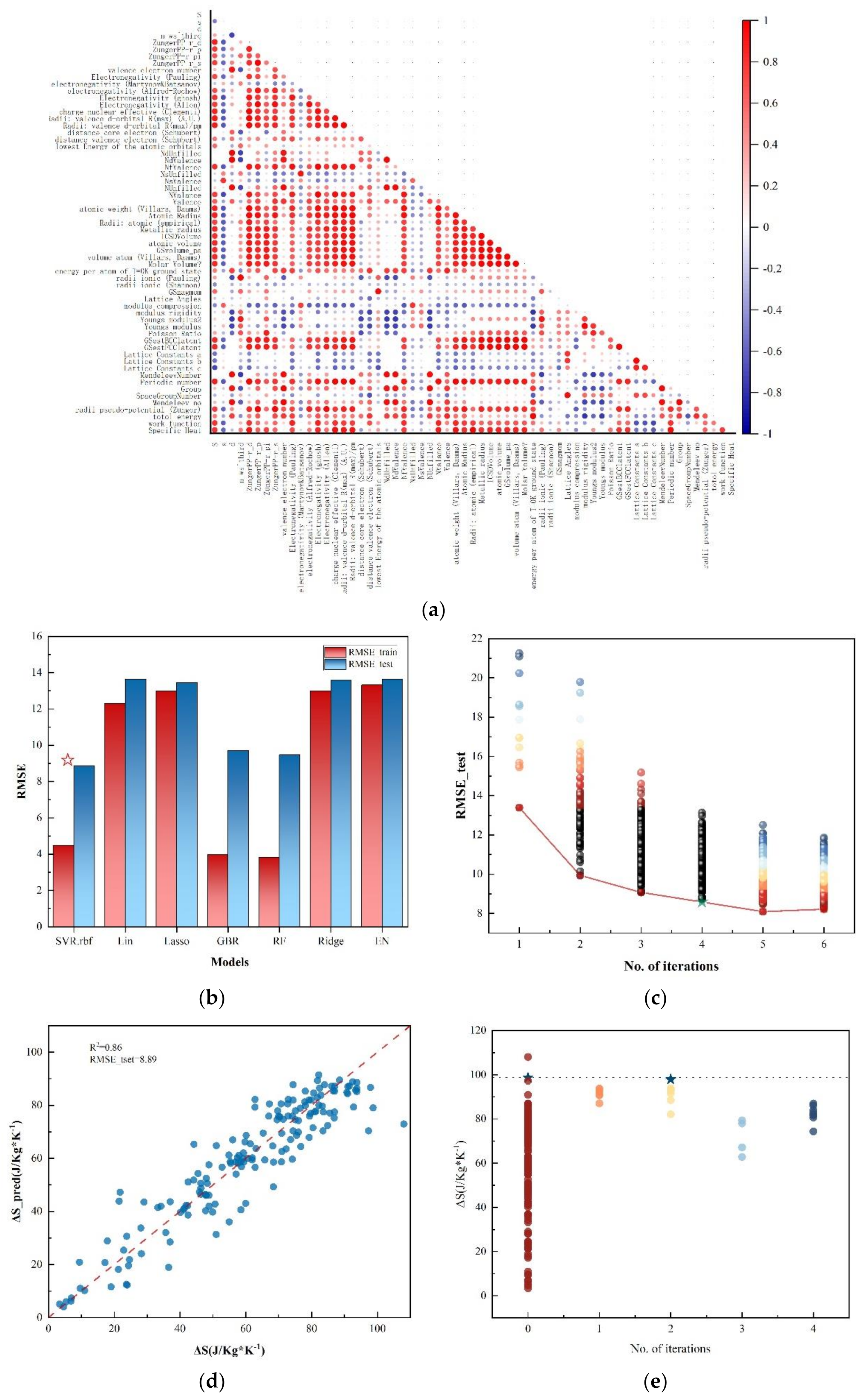

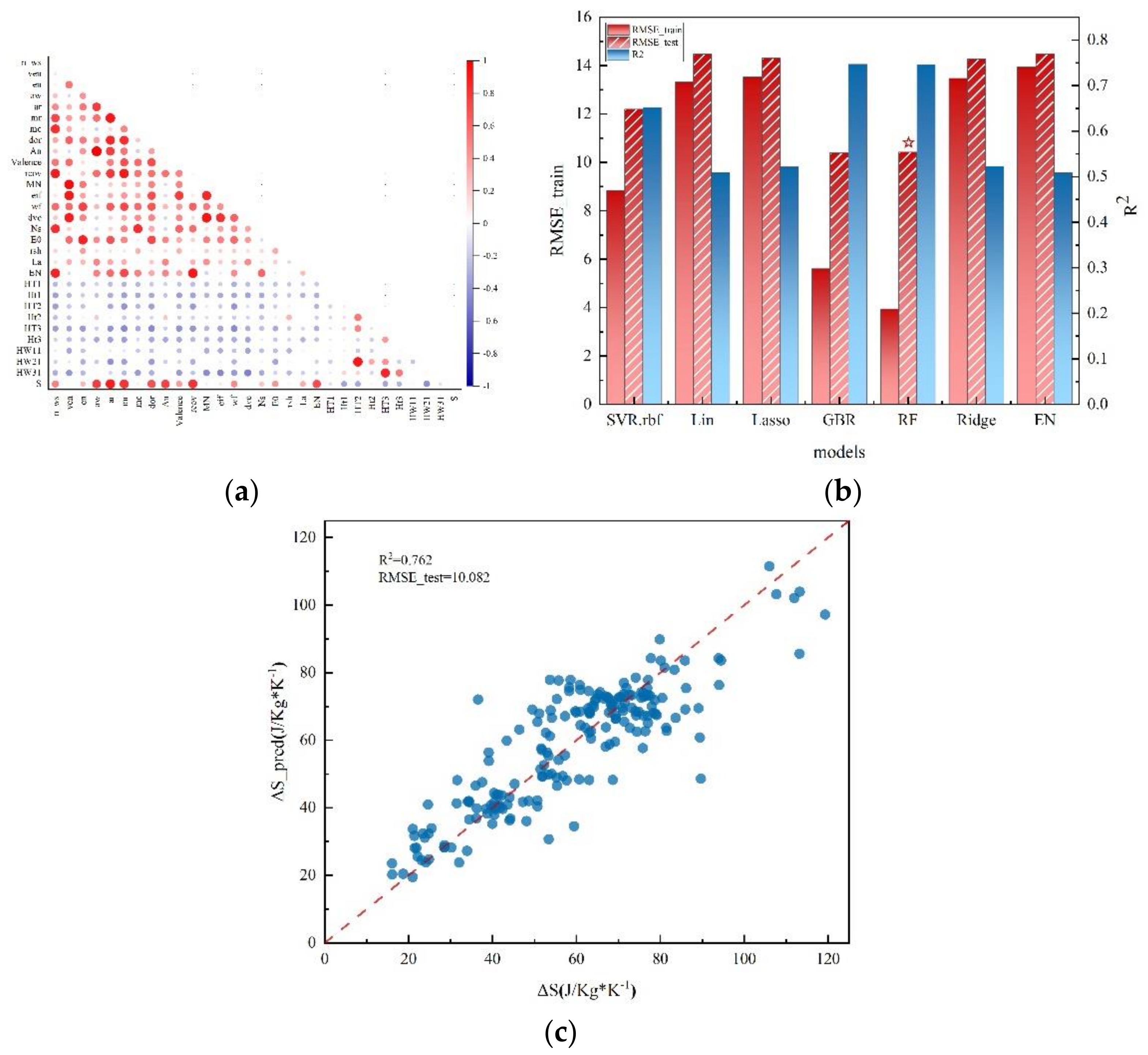

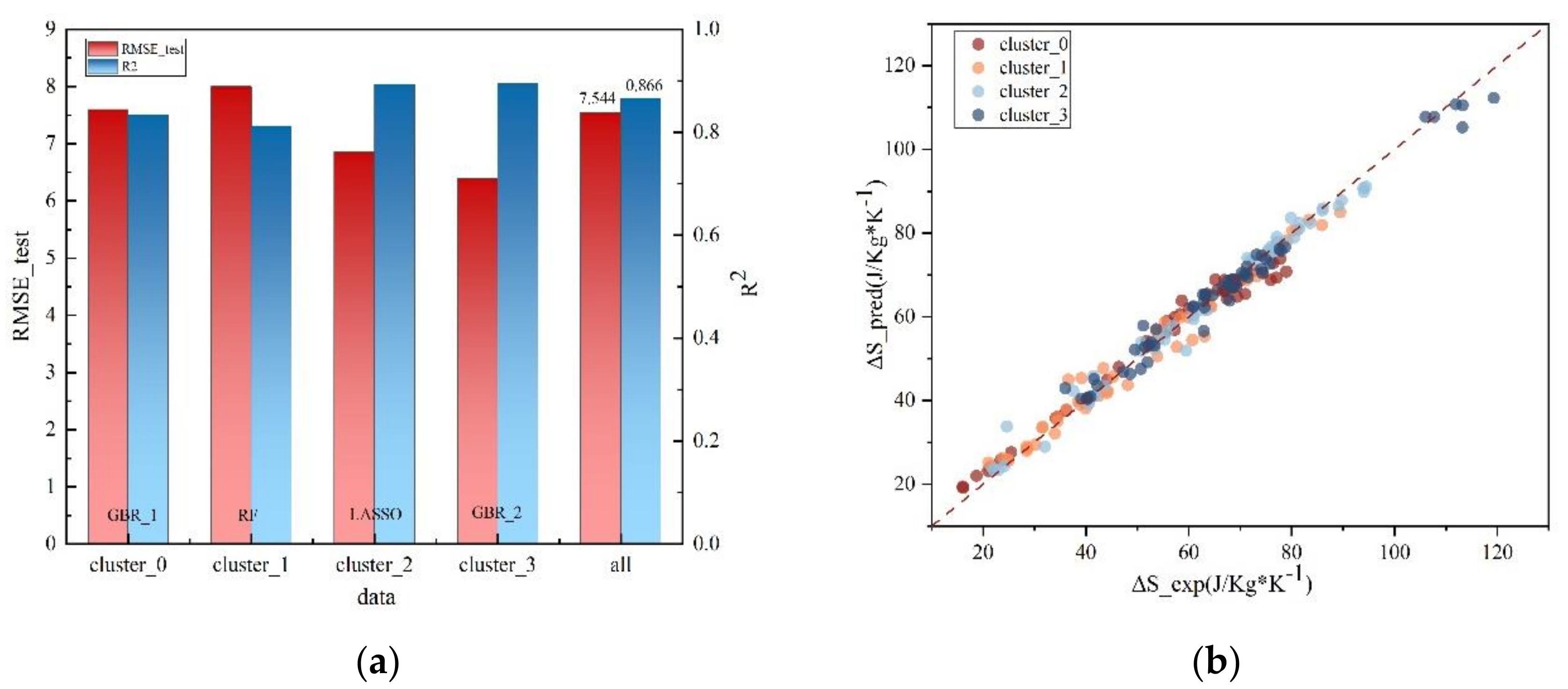

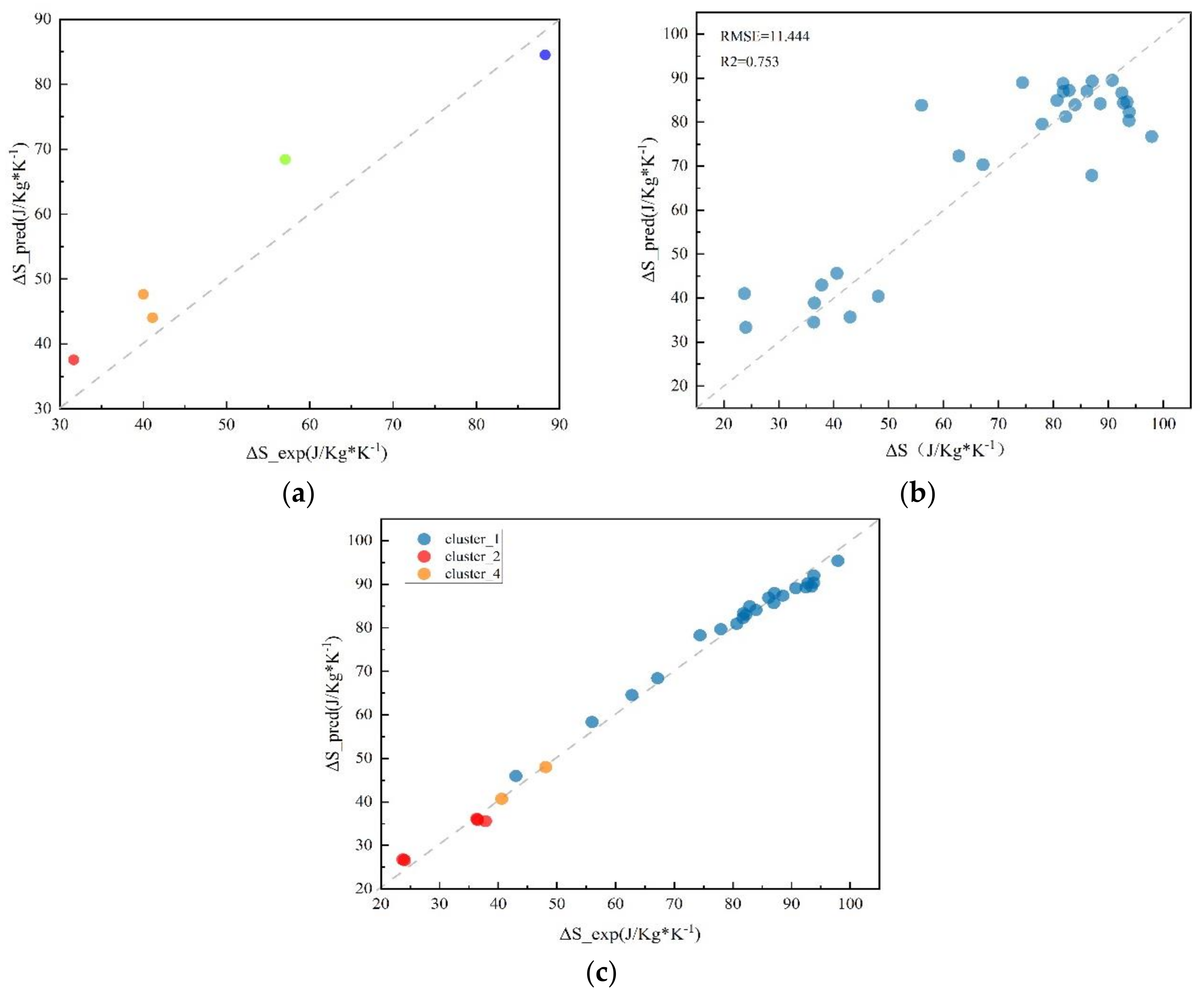

3.1. ML Model Selection and Evaluation

3.2. Validation

3.3. Materials Design toward High Elastocaloric SMA

4. Summary

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Secretariat, O. The Montreal protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer. United Nations Environment Programme. City: Nairobi, Kenya, 2000:54.

- Coulomb D, Dupont J-L, Pichard A. The Role of Refrigeration in the Global Economy - 29 Informatory Note on Refrigeration Technologies. City: Paris, 2015.

- Franco V, Blázquez J S, Ingale B, et al. The magnetocaloric effect and magnetic refrigeration near room temperature: materials and models. Annual Review of Materials Research, 2012, 42: 305-342.

- Valant, M. Electrocaloric materials for future solid-state refrigeration technologies. Progress in Materials Science, 2012, 57(6): 980-1009.

- Qian S, Geng Y, Wang Y, et al. A review of elastocaloric cooling: Materials, cycles and system integrations. International journal of refrigeration, 2016, 64: 1-19.

- Goetzler W, Shandross R, Young J, et al. Energy savings potential and RD&D opportunities for commercial building HVAC systems. City: Navigant Consulting, Burlington, MA (United States), 2017.

- Cui J, Wu Y, Muehlbauer J, et al. Demonstration of high efficiency elastocaloric cooling with large ΔT using NiTi wires. Applied Physics Letters, 2012, 101(7): 073904.

- Ossmer H, Miyazaki S, Kohl M. Elastocaloric heat pumping using a shape memory alloy foil device// Elastocaloric heat pumping using a shape memory alloy foil device. 2015 Transducers-2015 18th International Conference on Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems (TRANSDUCERS), Anchorage, AK, USA :IEEE, : 726-729.

- Schmidt M, Kirsch S-M, Seelecke S, et al. Elastocaloric cooling: From fundamental thermodynamics to solid state air conditioning. 2016, 22(5): 475-488.

- Tušek J, Engelbrecht K, Millán-Solsona R, et al. The elastocaloric effect: a way to cool efficiently. Advanced Energy Materials, 2015, 5(13): 1500361.

- Otsuka K, Ren X J P i m s. Physical metallurgy of Ti–Ni-based shape memory alloys. Progress in materials science, 2005, 50(5): 511-678.

- Frenzel J, George E P, Dlouhy A, et al. Influence of Ni on martensitic phase transformations in NiTi shape memory alloys. Acta Materialia, 2010, 58(9): 3444-3458.

- Ma J, Karaman I, Noebe R D. High temperature shape memory alloys. International Materials Reviews, 2010, 55(5): 257-315.

- Zhou Y, Xue D, Ding X, et al. Strain glass in doped Ti50(Ni50−xDx) (D=Co, Cr, Mn) alloys: Implication for the generality of strain glass in defect-containing ferroelastic systems. Acta Materialia, 2010, 58(16): 5433-5442.

- Ossmer H, Miyazaki S, Kohl M. The Elastocaloric Effect in TiNi-based Foils. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2015, 2: S971-S974.

- Schmidt M, Schütze A, Seelecke S. Scientific test setup for investigation of shape memory alloy based elastocaloric cooling processes. International Journal of Refrigeration, 2015, 54: 88-97.

- Chen H, Xiao F, Li Z, et al. Elastocaloric effect with a broad temperature window and low energy loss in a nanograin Ti-44Ni-5Cu-1Al Ti-44Ni-5Cu-1Al (at·%) shape memory alloy. Physical Review Materials, 2021, 5(1): 015201.

- Xu B, Wang C, Wang Q, et al. Enhancing elastocaloric effect of NiTi alloy by concentration-gradient engineering. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, 2023, 246: 108140.

- Yeung K W K, Cheung K M C, Lu W W, et al. Optimization of thermal treatment parameters to alter austenitic phase transition temperature of NiTi alloy for medical implant. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 2004, 383(2): 213-218.

- Deng Z, Huang K, Yin H, et al. Temperature-dependent mechanical properties and elastocaloric effects of multiphase nanocrystalline NiTi alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2023, 938: 168547.

- Liu S, Kappes B B, Amin-ahmadi B, et al. Physics-informed machine learning for composition–process–property design: Shape memory alloy demonstration. Applied Materials Today, 2021, 22: 100898.

- Malinov S, Sha W, McKeown J J. Modelling the correlation between processing parameters and properties in titanium alloys using artificial neural network. Computational Materials Science, 2001, 21(3): 375-394.

- Wen C, Zhang Y, Wang C, et al. Machine learning assisted design of high entropy alloys with desired property. Acta Materialia, 2019, 170: 109-117.

- Liu P, Huang H, Antonov S, et al. Machine learning assisted design of γ′-strengthened Co-base superalloys with multi-performance optimization. npj Computational Materials, 2020, 6(1): 62.

- Ohno, H. Training data augmentation: An empirical study using generative adversarial net-based approach with normalizing flow models for materials informatics. Applied Soft Computing, 2020, 86: 105932.

- Chanda B, Jana P P, Das J. A tool to predict the evolution of phase and Young’s modulus in high entropy alloys using artificial neural network. Computational Materials Science, 2021, 197: 110619.

- Lee J, Asahi R. Transfer learning for materials informatics using crystal graph convolutional neural network. Computational Materials Science, 2021, 190: 110314.

- Ding Y, Liu C, Zhu H, et al. A supervised data augmentation strategy based on random combinations of key features. Information Sciences, 2023, 632: 678-697.

- He S, Wang Y, Zhang Z, et al. Interpretable machine learning workflow for evaluation of the transformation temperatures of TiZrHfNiCoCu high entropy shape memory alloys. Materials & Design, 2023, 225: 111513.

- Yang Z, Li S, Li S, et al. A two-step data augmentation method based on generative adversarial network for hardness prediction of high entropy alloy. Computational Materials Science, 2023, 220: 112064.

- Zhang Y-F, Ren W, Wang W-L, et al. Interpretable hardness prediction of high-entropy alloys through ensemble learning. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2023, 945: 169329.

- Xue D, Balachandran P V, Hogden J, et al. Accelerated search for materials with targeted properties by adaptive design. Nat Commun, 2016, 7: 11241.

- Xue D, Xue D, Yuan R, et al. An informatics approach to transformation temperatures of NiTi-based shape memory alloys. Acta Materialia, 2017, 125: 532-541.

- Maharana K, Mondal S, Nemade B. A review: Data pre-processing and data augmentation techniques. Global Transitions Proceedings, 2022, 3(1): 91-99.

- Gareth J, Daniela W, Trevor H, et al. An introduction to statistical learning: with applications in R. City: Spinger, 2013.

- Schapire R E J N e, classification. The boosting approach to machine learning: An overview. Nonlinear estimation and classification, 2003, 171: 149-171.

- Khalil-Allafi J, Amin-Ahmadi B. The effect of chemical composition on enthalpy and entropy changes of martensitic transformations in binary NiTi shape memory alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2009, 487(1-2): 363-366.

- Wang T, Zhang K, Thé J, et al. Accurate prediction of band gap of materials using stacking machine learning model. Computational Materials Science, 2022, 201: 110899.

- Liu Y, Wu J, Wang Z, et al. Predicting creep rupture life of Ni-based single crystal superalloys using divide-and-conquer approach based machine learning. Acta Materialia, 2020, 195: 454-467.

- Zhang S, Chen D, Liu S, et al. Aluminum alloy microstructural segmentation method based on simple noniterative clustering and adaptive density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise. Journal of Electronic Imaging, 2019, 28(3): 033035.

- Malinov S, Sha W, McKeown J J. Modelling the correlation between processing parameters and properties in titanium alloys using artificial neural network. Computational materials science, 2001, 21(3): 375-394.

- Waber J, Cromer D T. Orbital radii of atoms and ions. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1965, 42(12): 4116-4123.

- Pauling, L. The nature of the chemical bond. IV. The energy of single bonds and the relative electronegativity of atoms. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1932, 54(9): 3570-3582.

- Rabe K M, Phillips J C, Villars P, et al. Global multinary structural chemistry of stable quasicrystals, high-TC ferroelectrics, and high-Tc superconductors. Physical Review B, 1992, 45(14): 7650-7676.

- Clementi E, Raimondi. Atomic screening constants from SCF functions. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1963, 38(11): 2686-2689.

- Pettifor D G, Pettifor D. Bonding and structure of molecules and solids. City: Clarendon Press Oxford, 1995.

| Heat treatment process parameter | Filling value |

|---|---|

| (K) | 1123 / 1223 / 1273 / 1323 |

| (mins) | 4320 |

| WQ / OQ / AC / FC | |

| (K) | 293 |

| (mins) | 0 |

| AC | |

| (K) | 293 |

| (mins) | 0 |

| AC |

| Clusters | Models | R2 | RMSE_train | RMSE_test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cluster_0 | GBR_1 | 0.834 | 3.178 | 7.598 |

| cluster_1 | RF | 0.812 | 2.899 | 7.998 |

| cluster_2 | Lasso | 0.893 | 5.678 | 6.861 |

| cluster_3 | GBR_2 | 0.895 | 1.859 | 6.393 |

| all | 0.866 | 7.544 |

| Element | Range |

|---|---|

| Ni | 1-Ti-third element |

| Ti | 45 at. % ~ 60 at. % |

| Cu, V, Mn, Fe, Hf, Pd | 0 ~ 30 at. % |

| Other | 0 ~ 10 at. % |

| Heat treatment | Range | Step |

|---|---|---|

| 1323 K | / | |

|

|

4320 mins WQ |

/ / |

| 323 K~ 1223 K | 300K | |

|

|

60 mins~ 720 mins WQ/AC |

60mins / |

| 323 K~ 1223 K | 300K | |

| 30 mins ~ 420 mins | 60mins | |

| WQ/AC | / | |

| 1323 K | / | |

|

|

4320 mins WQ |

/ / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).