Submitted:

19 August 2024

Posted:

20 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

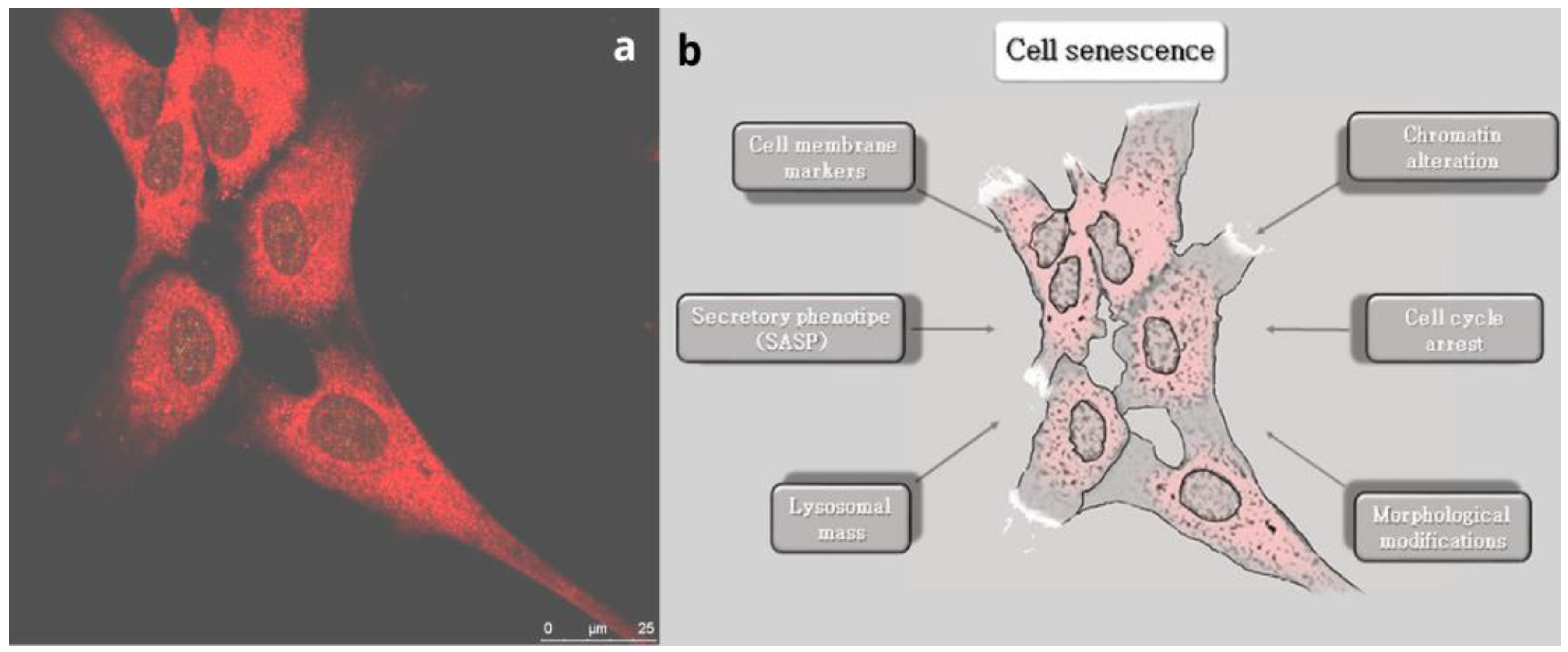

2. Assessment of Brain Aging In Vitro

3. Brain Aging in Rodents

4. Brain Aging in Ruminants

5. Brain Aging in Carnivores

6. Aging and Metabolism

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Informed Consent Statement

References

- Hayflick, L.; Moorhead, P.S. The Serial Cultivation of Human Diploid Cell Strains. Exp Cell Res 1961, 25, 585–621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zanotti, S.; Decaesteker, B.; Vanhauwaert, S.; De Wilde, B.; De Vos, W.H.; Speleman, F. Cellular Senescence in Neuroblastoma. Br J Cancer 2022, 126, 1529–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Pietrocola, F.; Roiz-Valle, D.; Galluzzi, L.; Kroemer, G. Meta-Hallmarks of Aging and Cancer. Cell Metab 2023, 35, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gualda, E.; Baker, A.G.; Fruk, L.; Muñoz-Espín, D. A Guide to Assessing Cellular Senescence in Vitro and in Vivo. FEBS J 2021, 288, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Espín, D.; Cañamero, M.; Maraver, A.; Gómez-López, G.; Contreras, J.; Murillo-Cuesta, S.; Rodríguez-Baeza, A.; Varela-Nieto, I.; Ruberte, J.; Collado, M.; et al. Programmed Cell Senescence during Mammalian Embryonic Development. Cell 2013, 155, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, B.G.; Baker, D.J.; Wijshake, T.; Conover, C.A.; Campisi, J.; van Deursen, J.M. Senescent Intimal Foam Cells Are Deleterious at All Stages of Atherosclerosis. Science (1979) 2016, 354, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussian, T.J.; Aziz, A.; Meyer, C.F.; Swenson, B.L.; van Deursen, J.M.; Baker, D.J. Clearance of Senescent Glial Cells Prevents Tau-Dependent Pathology and Cognitive Decline. Nature 2018, 562, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Mancera, P.A.; Young, A.R.J.; Narita, M. Inside and out: The Activities of Senescence in Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2014, 14, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyberg, L.; Wåhlin, A. The Many Facets of Brain Aging. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murman, D. The Impact of Age on Cognition. Semin Hear 2015, 36, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fjell, A.M.; Sneve, M.H.; Storsve, A.B.; Grydeland, H.; Yendiki, A.; Walhovd, K.B. Brain Events Underlying Episodic Memory Changes in Aging: A Longitudinal Investigation of Structural and Functional Connectivity. Cerebral Cortex 2016, 26, 1272–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidler, R.D.; Bernard, J.A.; Burutolu, T.B.; Fling, B.W.; Gordon, M.T.; Gwin, J.T.; Kwak, Y.; Lipps, D.B. Motor Control and Aging: Links to Age-Related Brain Structural, Functional, and Biochemical Effects. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010, 34, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.C.; Reuter-Lorenz, P. The Adaptive Brain: Aging and Neurocognitive Scaffolding. Annu Rev Psychol 2009, 60, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinkouskaya, Y.; Caçoilo, A.; Gollamudi, T.; Jalalian, S.; Weickenmeier, J. Brain Aging Mechanisms with Mechanical Manifestations. Mech Ageing Dev 2021, 200, 111575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, T.L.; Einstein, M.; Duan, H.; He, Y.; Flores, T.; Rolshud, D.; Erwin, J.M.; Wearne, S.L.; Morrison, J.H.; Hof, P.R. Morphological Alterations in Neurons Forming Corticocortical Projections in the Neocortex of Aged Patas Monkeys. Neurosci Lett 2002, 317, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H. Age-Related Dendritic and Spine Changes in Corticocortically Projecting Neurons in Macaque Monkeys. Cerebral Cortex 2003, 13, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geinisman, Y.; Detoledo-Morrell, L.; Morrell, F.; Heller, R.E. Hippocampal Markers of Age-Related Memory Dysfunction: Behavioral, Electrophysiological and Morphological Perspectives. Prog Neurobiol 1995, 45, 223–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepore, G.; Zedda, M.; Mura, E.; Giua, S.; Dedola, G.L.; Farina, V. Brain Aging and Testosterone-Induced Neuroprotection: Studies on Cultured Sheep Cortical Neurons. Neuroendocrinology Letters 2013, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, V.; Lepore, G.; Biagi, F.; Carcupino, M.; Zedda, M. Autophagic Processes Increase during Senescence in Cultured Sheep Neurons and Astrocytes. European Journal of Histochemistry 2018. [CrossRef]

- Dimri, G.P.; Lee, X.; Basile, G.; Acosta, M.; Scott, G.; Roskelley, C.; Medrano, E.E.; Linskens, M.; Rubelj, I.; Pereira-Smith, O. A Biomarker That Identifies Senescent Human Cells in Culture and in Aging Skin in Vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1995, 92, 9363–9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Blas, D.; Gorostieta-Salas, E.; Pommer-Alba, A.; Muciño-Hernández, G.; Gerónimo-Olvera, C.; Maciel-Barón, L.A.; Konigsberg, M.; Massieu, L.; Castro-Obregón, S. Cortical Neurons Develop a Senescence-like Phenotype Promoted by Dysfunctional Autophagy. Aging 2019, 11, 6175–6198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lleo, A.; Invernizzi, P.; Selmi, C.; Coppel, R.L.; Alpini, G.; Podda, M.; Mackay, I.R.; Gershwin, M.E. Autophagy: Highlighting a Novel Player in the Autoimmunity Scenario. J Autoimmun 2007, 29, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.J.; Torricelli, J.R. Isolation and Culture of Adult Neurons and Neurospheres. Nat Protoc 2007, 2, 1490–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Espín, D.; Serrano, M. Cellular Senescence: From Physiology to Pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014, 15, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Hou, W.; Bai, S.; Fan, J.; Tong, H.; Bai, Y. XAV939 Promotes Apoptosis in a Neuroblastoma Cell Line via Telomere Shortening. Oncol Rep 2014, 32, 1999–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalka, D.; Hoyer, S. Long-Term Cultivation of a Neuroblastoma Cell Line in Medium with Reduced Serum Content as a Model System for Neuronal Aging? Arch Gerontol Geriatr 1998, 27, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, P.; Chen, X.; Xie, Y.; Weston-Green, K.; Solowij, N.; Chew, Y.L.; Huang, X.-F. Cannabidiol Induces Autophagy and Improves Neuronal Health Associated with SIRT1 Mediated Longevity. Geroscience 2022, 44, 1505–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Y.-H.; Yan, J.-L.; Wang, Q.-J.; Chen, H.-C.; Ma, X.-Z.; Yin, J.; Gao, L.-P. Spermidine Ameliorates the Neuronal Aging by Improving the Mitochondrial Function in Vitro. Exp Gerontol 2018, 108, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.K.; Lee, D.I.; Kim, S.T.; Kim, G.H.; Park, D.W.; Park, J.Y.; Han, D.; Choi, J.K.; Lee, Y.; Han, N.-S.; et al. The Anti-Aging Properties of a Human Placental Hydrolysate Combined with Dieckol Isolated from Ecklonia Cava. BMC Complement Altern Med 2015, 15, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parpura, V.; Heneka, M.T.; Montana, V.; Oliet, S.H.R.; Schousboe, A.; Haydon, P.G.; Stout, R.F.; Spray, D.C.; Reichenbach, A.; Pannicke, T.; et al. Glial Cells in (Patho)Physiology. J Neurochem 2012, 121, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lécuyer, M.-A.; Kebir, H.; Prat, A. Glial Influences on BBB Functions and Molecular Players in Immune Cell Trafficking. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2016, 1862, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wong, A.W.; Willingham, M.M.; van den Buuse, M.; Kilpatrick, T.J.; Murray, S.S. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Promotes Central Nervous System Myelination via a Direct Effect upon Oligodendrocytes. Neurosignals 2010, 18, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VonDran, M.W.; Singh, H.; Honeywell, J.Z.; Dreyfus, C.F. Levels of BDNF Impact Oligodendrocyte Lineage Cells Following a Cuprizone Lesion. The Journal of Neuroscience 2011, 31, 14182–14190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöyhönen, S.; Er, S.; Domanskyi, A.; Airavaara, M. Effects of Neurotrophic Factors in Glial Cells in the Central Nervous System: Expression and Properties in Neurodegeneration and Injury. Front Physiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.-S.; Allen, N.J.; Eroglu, C. Astrocytes Control Synapse Formation, Function, and Elimination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2015, 7, a020370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.-S.; Clarke, L.E.; Wang, G.X.; Stafford, B.K.; Sher, A.; Chakraborty, C.; Joung, J.; Foo, L.C.; Thompson, A.; Chen, C.; et al. Astrocytes Mediate Synapse Elimination through MEGF10 and MERTK Pathways. Nature 2013, 504, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T.E.; Xie, Z.; Goldsmith, S.; Yoshida, T.; Lanzrein, A.-S.; Stone, D.; Rozovsky, I.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A.; Finch, C.E. The Mosaic of Brain Glial Hyperactivity during Normal Ageing and Its Attenuation by Food Restriction. Neuroscience 1999, 89, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Arellano, J.J.; Parpura, V.; Zorec, R.; Verkhratsky, A. Astrocytes in Physiological Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuroscience 2016, 323, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, N.R.; Day, J.R.; Laping, N.J.; Johnson, S.A.; Finch, C.E. GFAP MRNA Increases with Age in Rat and Human Brain. Neurobiol Aging 1993, 14, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, A.L.; Ousman, S.S. Astrocytes and Aging. Front Aging Neurosci 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisvert, M.M.; Erikson, G.A.; Shokhirev, M.N.; Allen, N.J. The Aging Astrocyte Transcriptome from Multiple Regions of the Mouse Brain. Cell Rep 2018, 22, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peinado, M.A.; Martinez, M.; Pedrosa, J.A.; Quesada, A.; Peinado, J.M. Quantitative Morphological Changes in Neurons and Glia in the Frontal Lobe of the Aging Rat. Anat Rec 1993, 237, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepore, G.; Gadau, S.; Mura, A.; Zedda, M.; Farina, V. Aromatase Immunoreactivity in Fetal Ovine Neuronal Cell Cultures Exposed to Oxidative Injury. European Journal of Histochemistry 2009, 53, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Letai, A.; Sarosiek, K. Regulation of Apoptosis in Health and Disease: The Balancing Act of BCL-2 Family Proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, G.W.; Oswald, M.J.; Palmer, D.N. The Development and Characterisation of Complex Ovine Neuron Cultures from Fresh and Frozen Foetal Neurons. J Neurosci Methods 2006, 155, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.M.; Kay, G.W.; Jordan, T.W.; Rickards, G.K.; Palmer, D.N. Disease-Specific Pathology in Neurons Cultured from Sheep Affected with Ceroid Lipofuscinosis. Mol Genet Metab 1999, 66, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, E.; Lepore, G.; Zedda, M.; Giua, S.; Farina, V. Sheep Primary Astrocytes under Starvation Conditions Express Higher Amount of LC3 II Autophagy Marker than Neurons. Arch Ital Biol 2014, 152, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Isla, T.; Spires, T.; De Calignon, A.; Hyman, B.T. Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. In; 2008; pp. 233–243.

- Moreno-Gonzalez, I.; Edwards, G.; Morales, R.; Duran-Aniotz, C.; Escobedo, G.; Marquez, M.; Pumarola, M.; Soto, C. Aged Cattle Brain Displays Alzheimer’s Disease-Like Pathology and Promotes Brain Amyloidosis in a Transgenic Animal Model. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallino Costassa, E.; Fiorini, M.; Zanusso, G.; Peletto, S.; Acutis, P.; Baioni, E.; Maurella, C.; Tagliavini, F.; Catania, M.; Gallo, M.; et al. Characterization of Amyloid-β Deposits in Bovine Brains. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2016, 51, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The Hallmarks of Aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C. Inflammaging as a Major Characteristic of Old People: Can It Be Prevented or Cured? Nutr Rev 2008, 65, S173–S176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montecino-Rodriguez, E.; Berent-Maoz, B.; Dorshkind, K. Causes, Consequences, and Reversal of Immune System Aging. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2013, 123, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zatta, P.; Drago, D.; Zambenedetti, P.; Bolognin, S.; Nogara, E.; Peruffo, A.; Cozzi, B. Accumulation of Copper and Other Metal Ions, and Metallothionein I/II Expression in the Bovine Brain as a Function of Aging. J Chem Neuroanat 2008, 36, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, M.H.; Capito, N.; Kuroki, K.; Stoker, A.M.; Cook, J.L.; Sherman, S.L. A Review of Translational Animal Models for Knee Osteoarthritis. Arthritis 2012, 2012, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charvet, C.J.; Hof, P.R.; Raghanti, M.A.; Van Der Kouwe, A.J.; Sherwood, C.C.; Takahashi, E. Combining Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Tractography with Stereology Highlights Increased Cross-cortical Integration in Primates. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2017, 525, 1075–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahalane, D.J.; Charvet, C.J.; Finlay, B.L. Modeling Local and Cross-Species Neuron Number Variations in the Cerebral Cortex as Arising from a Common Mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 17642–17647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquali, P. The Importance of Animal Models in Research. Res Vet Sci 2018, 118, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peruffo, A.; Cozzi, B. Bovine Brain: An in Vitro Translational Model in Developmental Neuroscience and Neurodegenerative Research. Front Pediatr 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsberg, G.M.; Nichol, J.; Araujo, J.A. Cognitive Dysfunction Syndrome. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 2012, 42, 749–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devinsky, O.; Boesch, J.M.; Cerda-Gonzalez, S.; Coffey, B.; Davis, K.; Friedman, D.; Hainline, B.; Houpt, K.; Lieberman, D.; Perry, P.; et al. A Cross-Species Approach to Disorders Affecting Brain and Behaviour. Nat Rev Neurol 2018, 14, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, B.N. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Species-Spanning Pathology. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2021, 35, 2815–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourjine, N.; Hoekstra, H.E. Expanding Evolutionary Neuroscience: Insights from Comparing Variation in Behavior. Neuron 2021, 109, 1084–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, A.A.; Rigby Dames, B.A.; Graff, E.C.; Mohamedelhassan, R.; Vassilopoulos, T.; Charvet, C.J. Going beyond Established Model Systems of Alzheimer’s Disease: Companion Animals Provide Novel Insights into the Neurobiology of Aging. Commun Biol 2023, 6, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, E. Neurobiology of the Aging Dog. Age (Omaha) 2011, 33, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, B.A. Comparative Veterinary Geroscience: Mechanism of Molecular, Cellular, and Tissue Aging in Humans, Laboratory Animal Models, and Companion Dogs and Cats. Am J Vet Res 2022, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hua, T.; Zhu, Z.; Luo, X. Age-Related Changes of Structures in Cerebellar Cortex of Cat. J Biosci 2006, 31, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn-Moore, D.; Moffat, K.; Christie, L.-A.; Head, E. Cognitive Dysfunction and the Neurobiology of Ageing in Cats. Journal of Small Animal Practice 2007, 48, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohn, T.T.; Head, E. Caspase Activation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Early to Rise and Late to Bed. Rev Neurosci 2008, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Praag, H.; Schinder, A.F.; Christie, B.R.; Toni, N.; Palmer, T.D.; Gage, F.H. Functional Neurogenesis in the Adult Hippocampus. Nature 2002, 415, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkoe, D.J. Alzheimer’s Disease: Genes, Proteins, and Therapy. Physiol Rev 2001, 81, 741–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, E.M.; Chaney, M.O.; Norris, F.H.; Pascual, R.; Little, S.P. Conservation of the Sequence of the Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid Peptide in Dog, Polar Bear and Five Other Mammals by Cross-Species Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis. Molecular Brain Research 1991, 10, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn-Moore, D.A.; McVee, J.; Bradshaw, J.M.; Pearson, G.R.; Head, E.; Gunn-Moore, F.J. Ageing Changes in Cat Brains Demonstrated by β-Amyloid and AT8-Immunoreactive Phosphorylated Tau Deposits. J Feline Med Surg 2006, 8, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brellou, G.; Vlemmas, I.; Lekkas, S.; Papaioannou, N. Immunohistochemical Investigation of Amyloid SS-Protein (Aß) in the Brain of Aged Cats. Histol Histopathol 2005.

- Landsberg, G.M.; Denenberg, S.; Araujo, J.A. Cognitive Dysfunction in Cats: A Syndrome We Used to Dismiss as ‘Old Age. ’ J Feline Med Surg 2010, 12, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lluch, G.; Navas, P. Calorie Restriction as an Intervention in Ageing. J Physiol 2016, 594, 2043–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayorga-Weber, G.; Rivera, F.J.; Castro, M.A. Neuron-glia (Mis)Interactions in Brain Energy Metabolism during Aging. J Neurosci Res 2022, 100, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puca, A.A.; Carrizzo, A.; Ferrario, A.; Villa, F.; Vecchione, C. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase, Vascular Integrity and Human Exceptional Longevity. Immunity & Ageing 2012, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderberg, M.; Edlund, C.; Kristensson, K.; Dallner, G. Lipid Compositions of Different Regions of the Human Brain During Aging. J Neurochem 1990, 54, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walz, W. The Brain as an Organ. In The Gliocentric Brain; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Schurr, A.; Gozal, E. Aerobic Production and Utilization of Lactate Satisfy Increased Energy Demands upon Neuronal Activation in Hippocampal Slices and Provide Neuroprotection against Oxidative Stress. Front Pharmacol 2011. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).