1. Introduction

Efficient land administration is fundamental to governance and sustainable development [

1,

2,

3]. While land administration involves a range of processes and functions which includes land registration, cadastral mapping, land tenure systems, land valuation and land use planning, the primary goal of land administration is to establish and maintain accurate and up-to-date records of land ownership, rights, and usage, thereby facilitating efficient land management and supporting socio-economic development [

3,

4,

5,

6]. This process encompasses establishing and maintaining a systematic record of land parcels, defining rights and obligations of individuals and groups to the land, and recording rights, which relies significantly on the cadastral mapping approach adopted. Hence, there is a persistent need for improved methods to aid and fast-track effective and consistent measurement and update of land records in the most appropriate way.

Cadastral mapping is a systematic process of delineating, recording, and managing land parcels and property boundaries within a specific geographic area. [

7,

8]. It involves creating maps or plans that represent the distribution of ownership, use, and related rights.[

9,

10]. Cadastral mapping employs various methods and technologies to accurately represent property and parcel boundaries. Cadastral mapping relies significantly on the spatial framework of land administration.

With improvements in technologies, the procedure of cadastral mapping has advanced from pacing to chains, tapes, Electronic Distance Measurement, satellite navigation systems and aerial imageries. Two prevalent technologies for cadastral mapping are the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) and aerial imageries. [

8,

11,

12,

13]. While GNSS technology enables surveyors to precisely determine the location of points, aerial imageries, satellites, aircraft and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) provide visual information for boundary delineation alongside information on land use, vegetation health, land cover, topography, and other environmental and geographic features. GNSS allows for efficient and rapid data collection in the field. On the other hand, aerial imageries contribute to comprehensive data capture. Furthermore, aerial imageries also facilitate remote data collection when necessary. GNSS is an integral part of aerial imagery collection as UAVs often carry GNSS chips, GNSS are used in coordinating Ground Control Points (GCPs) for UAV imagery, in obtaining control points for aerial photo mapping and georeferencing satellite imageries[

14].

Orthophotos acquired from Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) mapping processes, aerial images obtained from aircrafts and satellite imageries are the three commonly utilized aerial imageries for cadastral mapping. The Fit-for-Purpose Land Administration (FFPLA) approach advocates for the use of aerial imagery for land administration due to its cost-effectiveness and scalability [

4]. This approach is seen as a means of accelerating the process of land registration, ensuring the security of tenure for the poor, achieving global coverage of land registration, and providing individuals and groups with the benefits of an efficient land administration system. Based on principles such as flexibility, inclusiveness, participation, affordability, reliability, upgradeable and attainability, the FFPLA approach seeks to improve the spatial, legal and institutional frameworks of land administration to aid effective land governance for development[

4,

15].

In spite of global advancements in UAVs and Satellite Imagery for land administration, their underutilization persists in Nigeria and some other countries of the world where the need to fast-track land registration has become more prominent. A major challenge to leveraging remote sensing data for land administration previously was spatial accuracy, because of the resolutions of available imageries. However, advancements in remote sensing technology have led to an increase in the resolution of aerial imagery, making it more accurate and reliable for land administration purposes. This should remove the previous challenge and encourage increased utilization of this technology. Unfortunately, this is not the situation, as most states in Nigeria and similar places in developing countries still do not leverage the advantage. This underutilisation adversely affects land administration. In addressing the intricate dynamics surrounding the limited adoption of UAVs in Nigeria, it becomes important to highlight the potential synergy of integrating UAVs with GNSS for land administration and broader land management functions.

The availability of high-resolution aerial imageries across all contexts is another significant factor. The use of UAVs – the major source of high resolution imagery – is one of the most regulated technologies in the world, owing to their dexterity and use for various purposes [

16,

17]. Except for state implemented projects, UAV regulations in Nigeria often limits the use of UAVs for mapping to rural and peri-urban areas. Obtaining permission to use UAVs for mapping in urban areas in Nigeria is a complex and time-consuming process, often making it impractical or impossible. Meanwhile, it is commonly assumed based on building density that urban areas require high-resolution imageries for mapping, while rural areas can use low-resolution data. Unfortunately, rural and urban contexts are not exclusively different from each other. There are urban settlements with some rural patterns in between and rural settlements with some densely populated settlements. The need to determine the fitness of the various types of remotely sensed aerial images in mapping the different contexts of informal/formal rural, peri-urban and urban areas for land administration underpins the need for this research. Additionally, the underutilisation of UAV technology in Nigeria and similar developing countries, owing to several unclear factors, and the regulatory restrictions against the use of UAVs in urban areas where high-resolution images are most required for land administration and management owing to population density buttresses the need for this research.

Several researchers have advocated for the use of UAV orthophotos and satellite imageries for land administration. Notably, the potential of Unmanned Aerial Systems technology, including UAVs, was advocated to meet land data and user needs in Rwanda. The study concludes that UAS can contribute significantly to match most of the prioritized needs in Rwanda while acknowledging the limits posed by structural and capacity conditions. [

18]. Guidance on achieving efficient and reliable UAV data acquisition by analysing various flight configurations and their influence on data quality and cadastral feature extractability were also presented by earlier researches[

12,

19]. The work provides insights into the optimal number of ground control points required for accurate mapping and the challenges faced by different land-use categories. It recommends the use of drones with high-quality optical sensors, a suitable number of overlap ratios, and an appropriate number of ground control points for reliable cadastral mapping.

Origins and debates surrounding the use of remote sensing technologies, including UAV and satellite imageries for land administration were also presented in earlier research that discusses how remote sensing can be an entirely legitimate, if not an essential part of the domain. [

20]. The research concludes that photogrammetric and remote sensing methods have a strong historical and contemporary presence in land administration practice. Ground methods continue to dominate in many jurisdictions. The review concludes that any remnant arguments on the use, and apparent limitations, of photogrammetric methods and remote sensing applied to land administration can hardly be sustained. The use of UAVs has been identified as a promising tool for land administration in rural, peri-urban, and urban contexts. However, the success of UAVs in land administration is contingent upon the technology’s ability to address the specific challenges and needs of a given context. In areas where land administration may be absent or incomplete, it is important that flexible and pragmatic approaches be adopted to meet the specific needs of communities and governments

Despite improvements in the spatial resolutions of aerial imageries, only a few surveyors incorporate aerial imagery into their work for land administration in Ekiti State and across Nigeria, just like the many other developing contexts. Notably in Nigeria is Edo State; where satellite imageries, aerial orthophotos and UAV imageries are used by the Edo GIS for land administration and management. GNSS; an instrument for precise point positioning is the staple for cadastral mapping in most contexts. The GNSS process can be costly and time-consuming owing to the need to visit every demarcation point with the instrument. However, the use of aerial imagery can help speed up the cadastral mapping processes. Hence, this paper aims to investigate the challenges in the adoption of UAV technology for cadastral mapping in Nigeria, provide information on the associated challenges, and propose strategies aimed at leveraging UAVs for providing aerial imagery for cadastral mapping. Furthermore, the study assesses the use of multi-resolution UAV aerial imageries for land administration to identify their fitness for mapping cadastral boundaries in the various informal and formal contexts of rural, peri-urban and urban areas.

The next section presents an explanation of the data used and the rural, peri-urban, and urban areas mapped. It also contains the interviews conducted, and the design of the survey carried out to identify factors leading to the limited adoption of UAVs for land administration and management in Nigeria. In

Section 3, the results of the interviews, research survey, and aerial imagery survey were presented.

Section 4 presents information on leveraging UAVs for cadastral mapping. It discusses the fitness of Multi-resolution Satellite imageries from perspectives of recognisability, settlement characteristics and scalability. Finally, conclusions and recommendations about the adoption of UAVs and satellite imageries for cadastral mapping in rural, peri-urban and urban contexts were made based on the findings obtained during the study (

Section 5).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

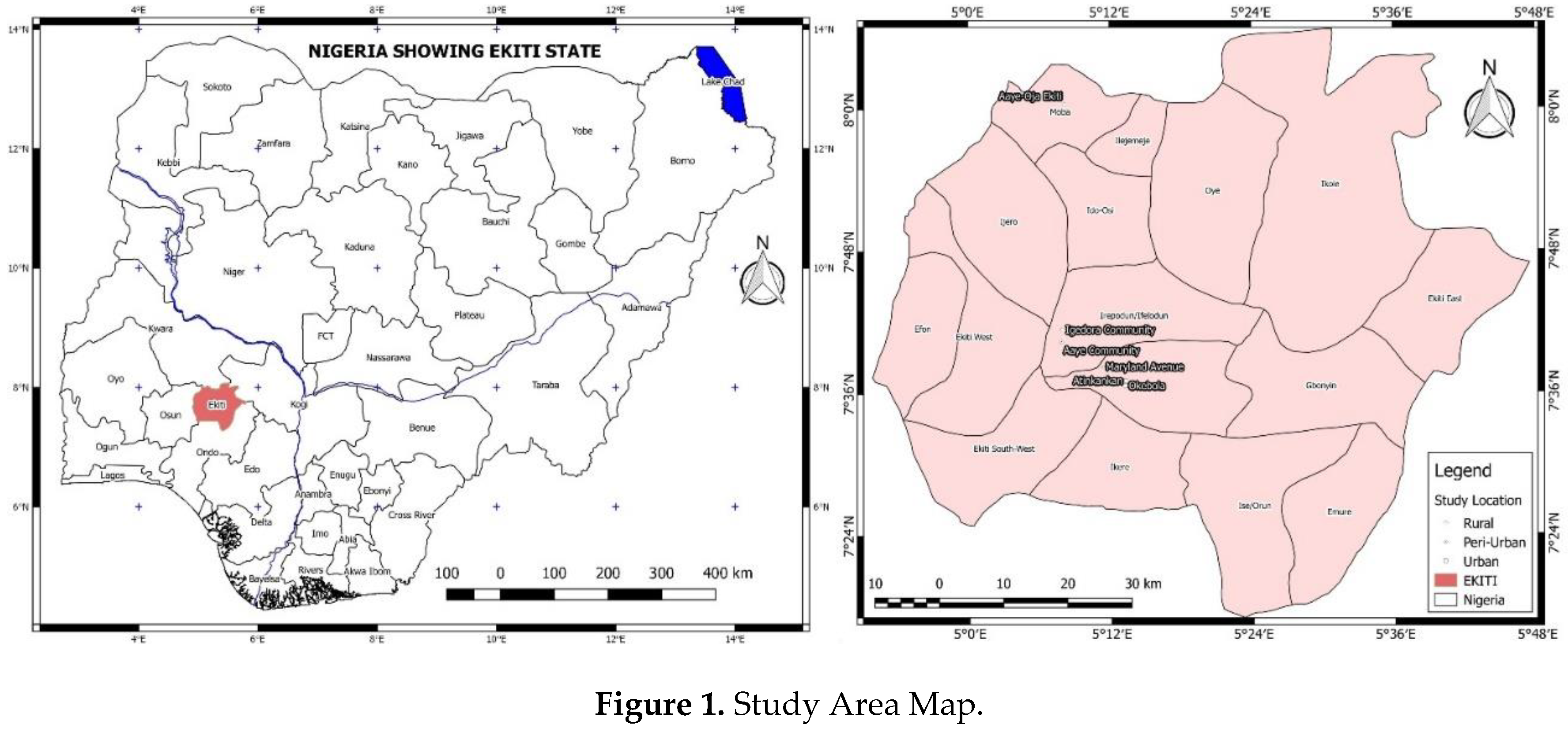

Ekiti is one of the 36 states of Nigeria aside from the Federal Capital Territory. Located within latitudes 7

o 16’N - 8

o 7’N and longitudes 4

o 51’E - 5

o 48’E. Ekiti lies at an average altitude of 528m above the Means seal level. It is bounded by Kwara State in the north, Ondo State in the south and part of the southeast, Kogi State in the east and Osun State in the west. With an approximate area of 5873 square kilometres [

21], Ekiti accounts for only 0.57% of the total land mass of Nigeria, yet, bigger in land mass when compared to Lagos, Anambra and Abia states. Deriving its name from the Yoruba word for hills i.e.

Okiti, Ekiti is a significantly undulating terrain, having a height variation of about 474m. It has its lowest point found towards the north-eastern part of the state around Iye–Ekiti, in the Ikole Local Government Area (LGA), with an elevation of 291m of ellipsoidal height, and its highest point of 765m found around Ogotun–Ekiti, in the Ekiti southwest LGA. Ekiti is made up of several rural and urban communities summing up to about 152 towns and villages. The 16 LGAs of the state are segmented into 3 senatorial districts, namely Ekiti North, Central and South senatorial districts.

To understand how aerial imagery of various resolutions can support land administration across the various formal and informal contexts of rural, peri-urban, and urban landscapes, six settlement typologies were identified, which includes; rural informal – Aaye - Oja, rural formal – Igedora, peri-urban informal – Aaye, peri-urban formal – Maryland Avenue, urban informal - Atinkankan and urban formal – Okebola. The communities were selected based on their needs for UAV products and their suitability for the research. A seventh community – Egbewa Government Residential Area (GRA) – was mapped to highlight absolute positioning accuracy in the research. Aside the above reasons; Atinkankan, Okebola and Egbewa GRA were also mapped based on the need for orthophotos for planning purposes by the Ekiti State Geospatial Data Centre (ESGDC).

Table 1.

Study Area Characteristics.

Table 1.

Study Area Characteristics.

| |

|

Location |

Type |

Description |

| 1 |

Rural |

Part of Aaye-Oja Ekiti, Moba LGA |

Informal |

A mix of clustered rural settlements and large expanses of agricultural lands |

| 2 |

Rural |

Igedora Community, Irepodun/Ifelodun LGA |

Formal |

A low-dense populated community with some planning. |

| 3 |

Peri-urban |

Aaye Community, Irepodun/Ifelodun LGA |

Informal |

Unplanned settlement with access to some basic amenities. Road, water, power |

| 4 |

Peri-urban |

Maryland Avenue, Ado-Ekiti, Ado LGA |

Formal |

Planned settlement with access to some basic amenities |

| 5 |

Urban |

Part of Atikankan , Ado-Ekiti, Ado LGA |

Informal |

A mix of Urban Slum with access to some basic facilities |

| 6 |

Urban |

Part of Okebola Street, Ado-Ekiti, Ado LGA |

Formal |

An urban area with some basic amenities |

| 7 |

Urban |

Part of Egbewa GRA |

Formal |

A Government Residential Area. |

Aaye-Oja Ekiti, situated in the Moba LGA of Ekiti State, is an ancient commercial community. Bounded by Otun and Igogo in the south, Ikosu in the east, Erinmope Ekiti in the North, and Osan in the west, Aaye-Oja is the nodal town of the Moba LGA of Ekiti state. Despite its nodal status and a comparable population among other towns in the LGA, Aaye-Oja lags in development compared to its counterparts of Otun and Erinmope-Ekiti. Its geometric properties of a mix of unplanned populated areas, scattered settlements, and expansive farmlands that characterizes the landscape makes it a fitting representation of a rural area. This community typifies the rural informal settlements found in Ekiti State, highlighting a blend of traditional and underdeveloped features.

On the other hand, Igedora Community, a satellite town of Igede-Ekiti, the LGA headquarters of Irepodun/Ifelodun stands as a rural settlement with well-planned layouts. Home to approximately 100 residents seeking the tranquillity of rural living, Igedora combines the simplicity of rural life with organized architectural and planning designs. The community reflects a balance between rural serenity and planned infrastructure, highlighting an example of rural living with intentional community planning.

Aaye is a significantly homogeneous aboriginal settlement in the peri-urban expanse of Igede-Ekiti. It serves as an informal peri-urban settlement within the local government headquarters of the Irepodun/Ifelodun LGA. The community embodies the characteristics of an informal settlement, featuring a mix of traditional and irregular structures. Aaye community bridges the gap between rural simplicity and urban influence, presenting an environment that captures the essence of informal peri-urban space.

Maryland Avenue is a rapidly developing peri-urban area of Ado-Ekiti. It lies behind the Government Residential Area (GRA) 3rd extension. Maryland Avenue distinguishes itself with well-planned layouts as a formal, though peri-urban settlement of Ado-Ekiti the state capital of Ekiti state. Unlike typical peri-urban settings marked by informality, this community boasts organized structures and roads. The area benefits from its proximity to the GRA 3rd extension, highlighting the potential for planned expansion and urbanization.

Atinkankan is a commercial and residential hub in Ekiti State. It is a representation of an overpopulated urban area. Despite its centrality to Ado-Ekiti, the characteristics of Atinkankan align more with informal urban settlements. The area projects a slum-like settlement, reflecting the challenges associated with unplanned urban growth.

Okebola stands as a densely populated urban residential area in Ado-Ekiti, boasting essential amenities such as a government-owned school and a hospital. This densely populated urban setting represents a structured urban settlement with organized residential buildings. The area mapped in Okebola reflects the vibrancy and density associated with urban living, highlighting a blend of residential, institutional, and commercial establishments.

Egbewa GRA stands out as a planned settlement with relatively superior amenities compared to the other mapped settlements. Its inclusion in the mapping was specifically intended to facilitate a precise comparison between aerial imagery-derived data and GNSS data, thereby ensuring absolute accuracy in the research findings.

2.2. Methods

Owing to the homogenous landscape of the Nigerian nation regarding UAV use and land administration laws, survey questions were designed and administered to identify factors influencing the adoption of UAVs for land administration and management in Nigeria, and interviews were conducted among professionals in the country. The results were analysed and knowledge drawn to identify pathways into leveraging UAVs and aerial imageries for land administration and Management in the country. Furthermore, through the lens of six distinct sites - namely parts of Aaye-Oja town, Igedora community, Aaye Community, Maryland Avenue, Atinkankan, and Okebola - representing formal and informal rural, peri-urban, and urban landscapes in Ekiti state, Nigeria, potential cadastral boundaries were manually delineated through on-screen digitization using different resolution imageries of 0.05m, 0.1m, 0.5m, and 1m. The inclusion of Egbewa GRA as the seventh settlement enabled a comparative analysis of the accuracy of 0.05m and 0.1m resolution imageries against GNSS-derived coordinates.

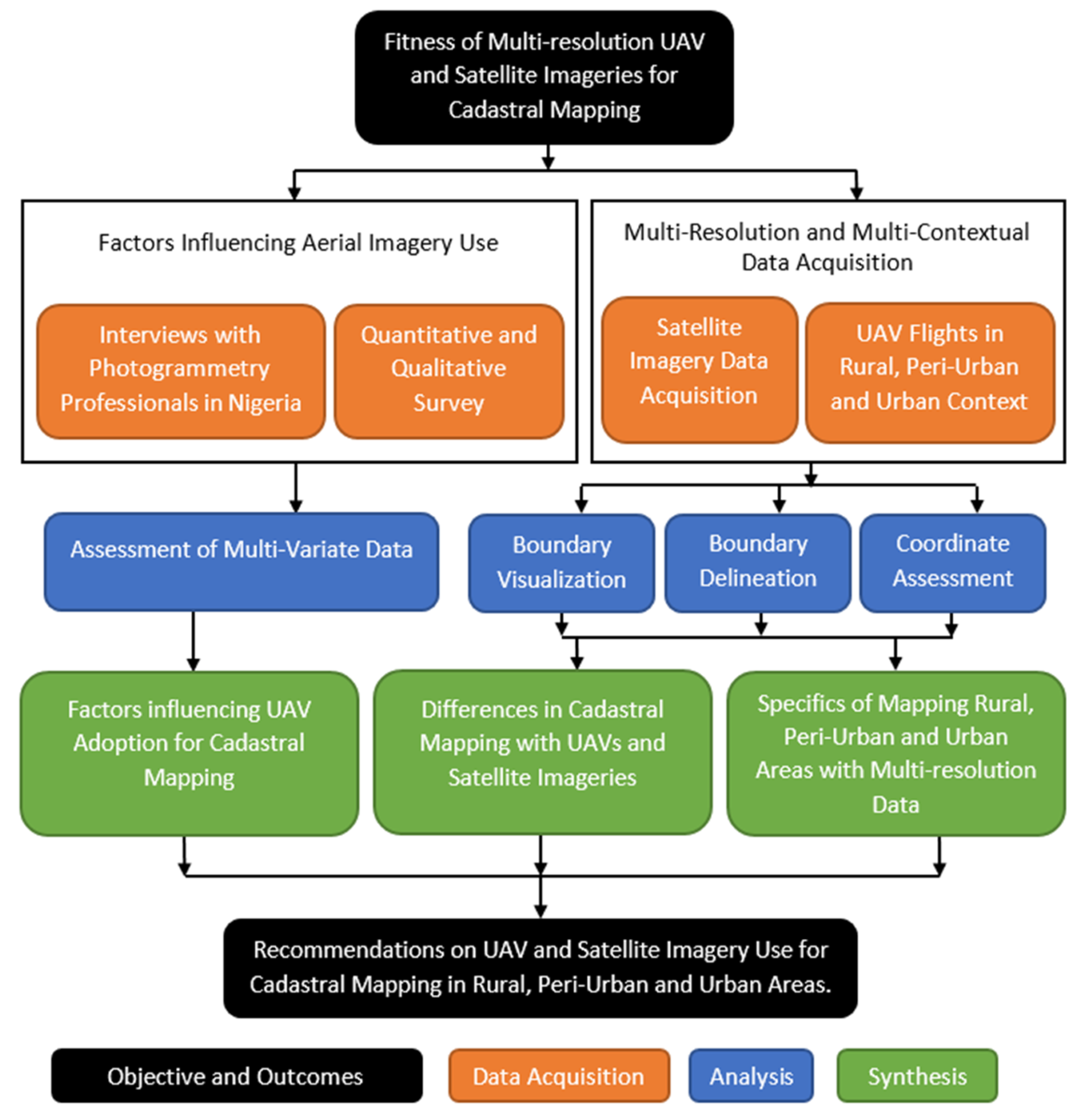

Figure 1.

Methodology Flow.

Figure 1.

Methodology Flow.

2.3. Factors Influencing Aerial Imagery Use

Employing a multifaceted approach, the study on UAV use incorporates perspectives through interviews and structured questionnaires to understand the use of aerial imageries for land administration in Nigeria, the factors contributing to the limited adoption of UAVs, and to identify potential solutions. To gain insight into the use of aerial imagery and UAVs for land administration and management-related projects in Nigeria, interviews were conducted with professionals in practice and government establishments. Three professionals actively involved in UAV mapping in Nigeria were interviewed. Their perspectives helped identify the current state of cadastral mapping with aerial imageries and UAVs in the country. A quantitative research approach was used to identify the factors limiting the adoption of UAVs for aerial imagery and to develop strategies for their successful adoption for cadastral mapping. The questions targeted at Surveyors, land administrators, and GIS analysts were developed and administered to participants using a random sampling approach. 54 of the 60 respondents (90%) identified as Surveyors, 22 respondents (36.7%) identified as GIS specialists. Six respondents (10%) are Land administrators, and 8.3% are spread across other professions. A link to the survey is provided in

Appendix A. The survey opened for 30 days and was closed at the 60th unique response. Responses were categorised into thematic groups based on commonalities, and the frequency of each item was analysed to determine recurring themes.

2.4. Multi-Resolution and Multi-Contextual Data Acquisition, Processing and Analysis

2.4.1. Aerial Images Data Acquisition and Processing

UAV Flights were conducted across the six sites ranging from rural to urban and informal to formal settlements using a DJI Mavic Pro Platinum UAV carrying a 10 megapixel resolution camera as part of a PhD research project. Three flights were conducted to cover the densely populated part of Aaye-Oja. A flight each was conducted for other areas to be mapped. All flights were conducted at 100m flying height with forward and side overlaps of 80% and 72% respectively. Agisoft Metashape Professional was used in processing imageries of the six sites. Available 2.1m panchromatic and 3.5 multi-spectral satellite imagery covering part of Aaye-Oja Ekiti, of Ekiti State were obtained from the National Space Research and Development Agency (NASRDA).

The ortho mosaics produced from the processed UAV images were exported in 0.05m, 0.1m, 0.5m and 1m spatial resolution. A 1-hectare rectangular shape defined on AutoCAD 2007 was selected across all six orthomosaics for equal comparison of study areas. Using the (GDAL) module, the Clip Raster by Extent tool of QGIS 2.14.17 was used to clip each image with the defined area. The 1-hectare area was selected to reflect the typical characteristics of the context for which the study area was chosen.

2.4.2. Reference Data for Accuracy Comparison

The absence of a reference cadastral data set necessitated the adoption of a relative accuracy comparison approach to maintain consistency across all six-settlement typologies. Consequently, coordinates from the 0.05m resolution image were designated as the reference, and coordinates from 0.1, 0.5, and 1m imagery were compared to determine positional accuracy.

However, to show the benefits of reference data in the research, a seventh flight was conducted, dedicating additional time to acquiring GNSS data in Real Time Kinematic (RTK) mode, which served as the reference. This enabled an absolute comparison with 0.05 and 0.1 orthomosaics, as the GNSS-coordinated marker points were not discernible in the lower-resolution 0.5 and 1m imagery.

2.4.2. Multi-Resolution Aerial Imagery Analysis for Cadastral Mapping Fitness Determination

Four images from each site, representing different spatial resolutions of 0.05m, 0.1m, 0.5m and 5m were assessed for clarity and feature delineation at 1:500 scale as shown in Error! Reference source not found.B. Owing to the need to maintain consistency in the data sources and in the comparism within various settlement typologies, a 1-hectare area was clipped for visual assessment and coordinate comparison, coordinates of 10 points delineating parcels were identified from the digitised sets of coordinates, and 0.05 UAV imageries were adopted as reference. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for the 0.1, 0.5 and 1m resolution images were calculated. The area of a parcel was calculated from the delineated coordinates of each resolution of UAV orthomosaics (0.1, 0.5, and 1m) and compared to the area of the parcel at 0.05m resolution. The Normalized Parcel Area Error (NPAE), which expresses the relationship between the observed area of the parcel () at different image resolutions and the reference area of the parcel () at the highest resolution of 0.05m was computed. This was computed by dividing the absolute difference between them by the reference area and multiplying the result by a normalising factor (m), which was 1000 squared meters in this case. The equation allows us to compare the errors in parcel area estimation between the different image resolutions while accounting for the different scales and accuracies of the data.

The results of the RMSE and NPAE across the various geographical contexts were analysed and discussed to identify the fitness of the multi-resolution aerial imageries across multi-contextual geographical areas for cadastral mapping purposes.

RMSE and NPAE were computed as follows:

Also, the RMSE approach adopted was repeated for the absolute comparison using GNSS data as reference while the 0.05m and 0.1m imageries served as observed values.

3. Results

This section provides results of the interviews with professionals in practice and government in Nigeria; the survey carried out with 60 respondents, the assessment of multi-resolution orthomosaic imageries produced from the acquired UAV mapping process and the satellite imageries, the coordinates of the delineated points and the areas of the delineated parcels.

3.1. The State of Land Administration with Aerial Imageries in Nigeria

From the interview conducted, it was realised that the use of aerial imagery and UAVs for land administration in Nigeria is a growing trend. However, challenges exist to the adoption and use of aerial imagery in the country. Edo State is a typical state with the use of aerial imagery for land administration in the country. In the state, the government uses acquired aerial imageries as base maps to verify the consistency of existing survey plans produced by survey professionals before Certificates of Occupancies (C of O) are issued. When the need arises, some sites are visited and checked with GNSS receivers. As urbanisation takes place, the need for re-survey arises. The Government, for land registration purposes, uses UAVs to update the base map and to prepare survey documents. While this approach is effective in most cases, it is laced with challenges when tree canopies cover demarcation points. When the fine details crucial for demarcation are not easily found on the image produced, traditional ground surveying methods are employed.

Other states such as Lagos State, Sokoto, Gombe, Kaduna, Nassarawa, Benue, Plateau, the Federal Capital Territory and Ekiti are making efforts to incorporate aerial imageries into their cadastral mapping systems. Challenges referred to by the practitioners constraining the process in some of the contexts include the technical issues of non-overlapping images of contiguous areas and differences in datum parameters. Other challenges include vegetative cover limitation, difficulty in importing UAVs into Nigeria for professional surveying and mapping by non-governmental agencies and professionals, and the management of UAV imagery infrastructure. Both Government and non-governmental bodies lamented the lack of a national regulatory framework for effective guidance of UAV surveys and the use of aerial imageries for cadastral mapping in Nigeria. The results of this interview helped to shape the design of the survey used to assess the factors affecting limited UAV use for land administration and management in Nigeria.

3.2. Factors Influencing UAV Use for Cadastral Mapping

Further insights into the factors influencing the use of UAVs for cadastral mapping in Nigeria and similar contexts were received in the survey conducted.

3.2.1. Population Characteristics

35% of respondents to the survey carried out to evaluate the “Factors Influencing Limited UAV Adoption for Land Administration and Management in Nigeria” are from Ekiti state, while the rest come from the other 35 states of Nigeria and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT).

Table 2 gives details of respondents to the survey. A total number of 60 responses were received. From the survey result, 54.2% of respondents in Lagos State indicate the use of UAVs for land administration in Lagos State, while 47.7% acknowledged the same for the Federal Capital Territory. In both cases, results show that the implementations face some challenges.

3.2.2. Awareness and Education

53.3%(32) of respondents to the survey agree to have used aerial imageries for cadastral mapping in Nigeria. 55% (33) of the respondents claimed to be very aware of the use of UAVs and their applications in land administration. 38.3%(23) claim to be moderately aware and 6.7%(4) claim not aware. While accessing the number of respondents that have received formal education or training, only 56.7% (34) of respondents indicated to have received education from secondary or tertiary institutions, Mandatory Continuous Professional Development Programs or other UAV certification training. This underscores the importance of increasing accessibility to UAV training among current and prospective land professionals in the Country.

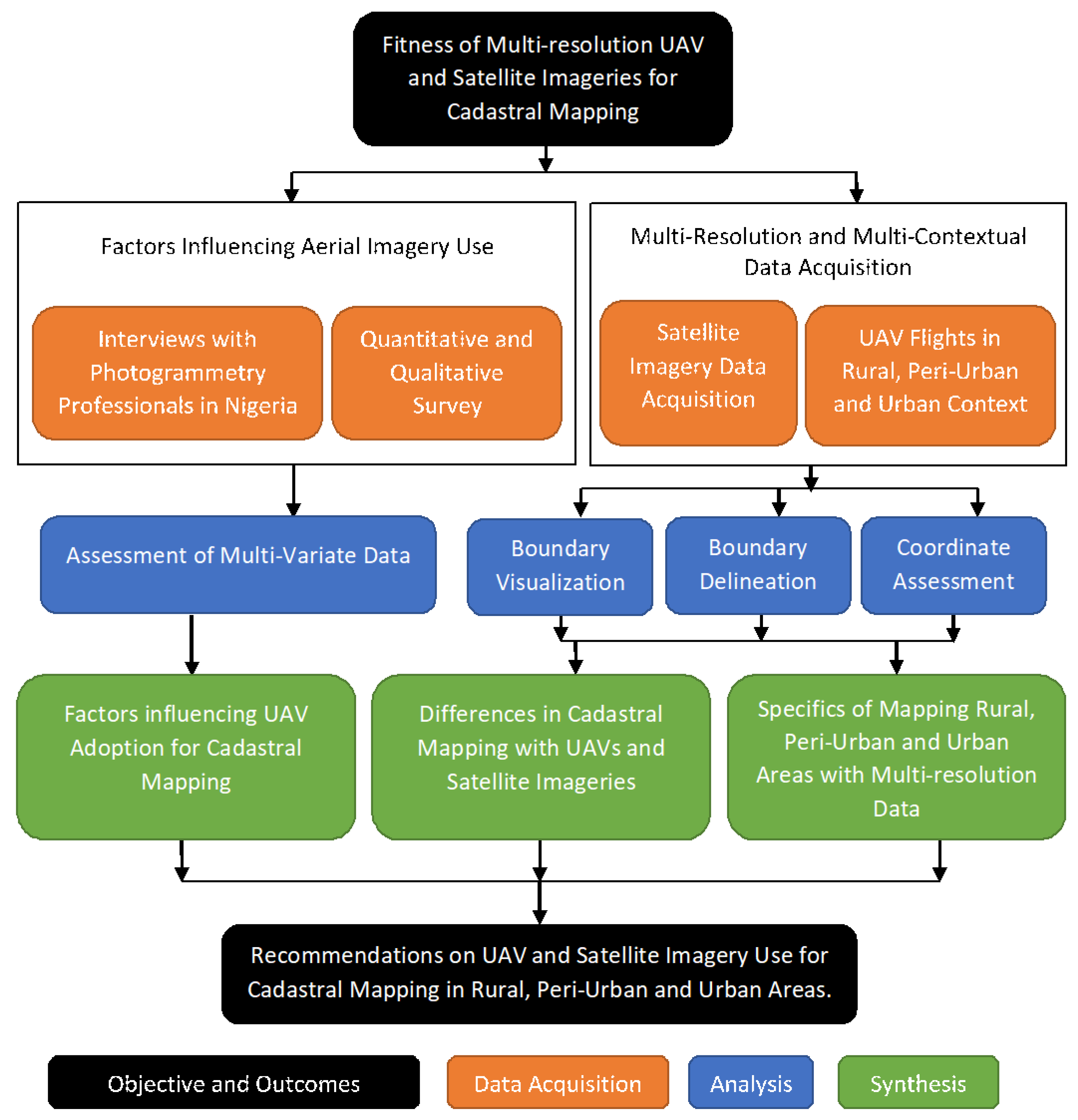

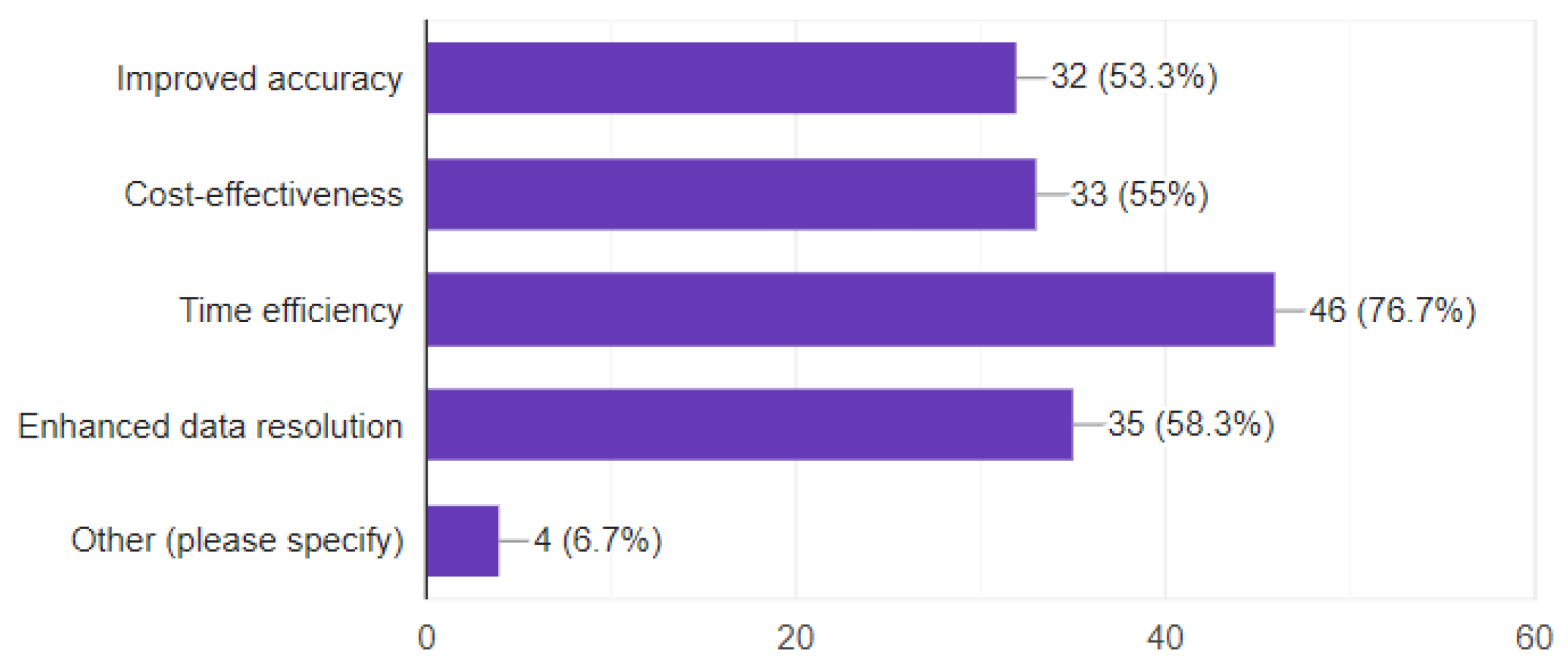

3.2.3. Perceived Benefits and Concerns of Using UAVs for Land Administration

In response to the question that asked of the potential benefits associated with the use of UAVs in land administration, time efficiency ranks the highest, followed by enhanced data resolution. Improved accuracy ranks the lowest, with 53.3% acknowledging it. This implies that the population sampled generally accepts UAVs as beneficial to land administration. Respondents suggested other benefits of UAVs, such as confidence and reliability, access to inaccessible locations, data storage and retrieval, and security and safety in volatile areas. The quantitative result is shown in

Figure 2.

3.2.4. Concerns and Challenges Perceived in Adopting UAVs for Land Administration and Management in Nigeria

The Cost of UAV technology ranks the highest at 68.3% (41), and the data security concerns rank the lowest at 33.3% (20) among the challenges perceived in adopting UAVs for land administration and management in Nigeria. Respondents also opined that a lack of regulatory framework and limited expertise are major challenges in adopting UAVs for land administration. This result is displayed in a horizontal bar graph in

Figure 3. Other challenges outlined by respondents includes bottlenecks in acquiring the necessary certification for UAV operation from regulatory agencies, acceptability issues and UAV pilot licensing as the factors militating against the adoption of UAVs for land administration and its wider land management functions in the country.

3.2.5. Regulatory and Policy Environment

58.3% (35) of the respondents indicated not being aware of specific regulations guiding the responsible use of UAVs in land administration in their state. This corroborates the lack of regulatory framework mentioned by professionals in the interviews conducted.

6.7% (4) of the respondents rated the regulatory framework as excellent, and 20% (12) of the respondents considered the regulations to be good, acknowledging their adequacy but suggesting room for minor improvements. 25% (15) of respondents expressed that the regulatory framework had some gaps or inconsistencies, indicating a need for improvements to enhance its effectiveness. 16.7% (10) of respondents indicated substantial deficiencies in the existing regulations, suggesting that significant reforms are required for effectiveness. While 31.7% (19) of respondents abstained from expressing an opinion, citing insufficient knowledge or experience to make a judgment. This further corroborates the need for improved regulations and documents to guide the use of UAVs across the countries.

In identifying the specific regulatory challenges hindering the widespread adoption of UAVs for land administration and management in Nigeria, respondents identified several challenges having the below listed as most re-occurring:

Licensing and Certification: Participants highlighted challenges related to obtaining licenses and certifications for UAV operation. Issues such as inconsistent licensing procedures and the lengthy process of obtaining the End User Certificate (EUC) were prominent concerns.

Security and Regulatory Restrictions: Respondents expressed concerns about security issues, particularly the identification of no-fly zones, restrictions imposed by military personnel (e.g., the Nigerian Army), and limitations due to airport or airforce authority regulations.

Government Policies and Awareness: Participants cited challenges related to government policies, funds, and the absence of enabling laws for UAV use. Additionally, the lack of awareness among stakeholders was identified as a barrier to widespread adoption.

3.2.6. Cost and Accessibility

Cost-related challenges were a recurring theme, including the cost of UAV technology, the expenses associated with obtaining necessary licenses, and the financial requirements for satisfying regulatory procedures. Results indicate that the cost associated with acquiring and maintaining UAV technology is a barrier to the use of the technology in the Nigerian Context. 16 (26.7%) and 27(45%) of the 60 respondents strongly agree and agree, respectively, that the cost of acquiring and maintaining UAV technology is a barrier to leveraging the technology in the Nigerian Context. 28 of the 60 respondents provided additional information on the cost and accessibility of UAV technology in Nigeria. The most frequently cited challenge was the high cost of acquiring UAVs and the associated software for image processing. Free and open-source software, such as OpenDroneMap and WebODM etc., were identified as alternatives for UAV data processing. Additional concerns included the high cost of licenses and certificates for UAV pilots, as well as the financial implications of data management. Participants emphasised the overall high cost attributed to the importation of the equipment.

Also, a larger percentage of participants opined on the non-availability of technical infrastructure to drive UAV technology in the country, as 6.7%(4) and 58.3%(35) responded that it is insufficient and sufficient, respectively. Participants underscored the need for investments to enhance the technical infrastructure for UAV adoption.

3.2.7. Leveraging UAV Technology for Aerial Imagery Provision in Nigeria

In leveraging UAV technology for land administration, participants stressed the need for government and private support for training institutions, integration of UAVs into professional bodies' continuing education programs and seminars, and the establishment of a regulatory framework. Financial support and government policies were highlighted as crucial factors to promote the acceptance and affordability of UAVs for mapping purposes. Recommendations extended to creating a UAV Board for pilot certification, increasing awareness through campaigns, and integrating UAV technology into higher education curricula.

Responses from participants underscore significant gaps in UAV training, particularly the absence of a formal curriculum devoted to UAV training in Nigerian higher learning institutions. The suggestions focused on the imperative need for comprehensive UAV training programs in polytechnics, universities and survey-related institutions. Despite the current limitations, participants expressed optimism about the evolving survey methods, transitioning from analogue to digital and now incorporating visual technology. It is believed that widespread UAV adoption is imminent. Participants stressed the importance of disseminating research results to generate interest. Additional comments highlight the critical role of UAVs in addressing security challenges in Nigeria and emphasise the need for enhanced awareness regarding their ethical use.

3.3. Analysis of UAV and Satellite Multi-Resolution Imagery in Varied Geographical Contexts for Cadastral Mapping

3.3.1. Differences in Mapping Rural, Peri-Urban and Urban Areas

From the UAV flights the imageries of 2.16, 3.39, 3.02, 2.88, 3.19 and 3.20 cm resolution covering Aaye-Oja, Igedora, Aaye Community, Maryland Avenue, Atinkankan and Okebola respectively were produced. The 1 – hectare area clipped out of each image were export at 0.05, 0.1, 0.5 and 1m resolution.

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 shows orthomosaic maps of the areas.

The ortho-mosaic imagery of part of Aaye-Oja Ekiti (a) exhibits characteristics typical of rural and informal settlements with linear or clustered settlement patterns and a large expanses of farmlands. This particular image portrays a mix of unplanned and scattered structures interspersed with farmland. Buildings are irregularly placed, and property boundaries are undefined. The lack of formal planning is evident in the absence of structured layouts and organised demarcations. Being a rural area, most properties do not have physical demarcations.

The imagery of Igedora

Figure 5 presents the geometric characteristics of a rural and formal settlement. The landscape shows well-planned layouts with organised, distantly placed building structures. The geometric features include clearly defined property boundaries, structured road networks, and a planned arrangement of buildings. The UAV aerial imagery reflects a form of formalised rural settlement.

Aaye Community's UAV aerial imagery depicts an informal peri-urban settlement.

Figure 6. The geometric characteristics reveal a mix of unplanned structures, scattered settlements, and an absence of formal organisation. The landscape lacks the well-defined boundaries and planned layouts seen in formal settlements, displaying the informality typical of peri-urban areas.

In Maryland Avenue, the aerial imageries capture the well-laid-out buildings with structured road networks. Property boundaries are clearly defined with fences, except that open spaces are prevalent owing to the gradual transition from rural to urban areas.

Figure 7.

Imageries from Atinkankan reveal the geometric characteristics of an urban and informal settlement.

Figure 8. The northwestern landscape shows densely packed, irregularly shaped slum-like settlements with limited infrastructure. It presents a lack of organised layouts and undefined property boundaries that typify informal urban development.

On the other hand, the imagery of area mapped in Okebola exhibits the characteristics of an urbanised area

Figure 9. The landscape features well-laid-out buildings, structured road networks, and clearly defined property boundaries. The area typifies a formalized and regulated urban development with organized layouts.

The orthomosaic of Egbewa GRA reveals an urban landscape, characterized by neatly arranged buildings, systematic road networks, and distinct property boundaries. This area embodies a formally planned and regulated urban environment, marked by orderly layouts and well-defined spatial organization as shown in

Figure 10.

3.3.2. Interpretability of Cadastral Boundaries from Multi-Resolution Imageries

The interpretability of cadastral boundaries from the 0.05, 0,1. 0,5 and 1m resolution aerial imageries of the same site were examined by visually comparing recognisable features across the six study sites at a 1:500 visualisation scale on QGIS 2.14.17 as shown in

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16. On all cases, the problem of tree canopy obstructing the delineation process from computer with aerial imagery persists.

Figure 11 represents the imageries of a typical rural agricultural area, showing small farms extracted from the rural informal settlement of Aaye-Oja. In the 1m resolution image of the area

Figure 11 (a), individual farms can only be identified. The image lacks appropriate fineness to aid the recognition of boundary demarcation points. However, in the higher resolutions of 0.5, 0.1, and 0.05, boundary points can be identified and delineated.

Typical of formal settlements, the rural area of Igedora is significantly laced with fences as physical boundaries, thereby making property demarcation easier not only for the people having rights to the property but also for third persons. From

Figure 12(a) with 1m resolution, although features like buildings and farmlands are recognisable, the image is not refined enough for clear demarcation. On the other hand, property boundaries are easily identified on

Figure 12(b, c and d) which corresponds to 0.5, 0.1 and 0.05 m resolutions, respectively. At the 1:500 zoom level adopted, the difference between

Figure 12(c) and

Figure 12(d) cannot be appreciated. The difference in 0.1 and 0.05m resolution imageries only became visually significant at a scale 1:250 on the GIS software.

Figure 13 represents a clip from part of the peri-urban informal settlement of Aaye community. Features like buildings, roads and vegetation can be recognised in the 1m resolution image

Figure 13 (a). However, the image lacks adequate fineness to aid proper delineation or identification of smaller features like wells, boreholes, etc. On the other hand,

Figure 13 (b) gives better clarity to features. Tree types are easily identified with higher resolution imageries. The difference between

Figure 13 (c and d) remains unclear when observed visually at a scale lower than 1:250 on the GIS software.

Figure 14 is a clip from the typical peri-urban formal settlement. Boundaries can be perceived in the 1m resolution image in

Figure 13(a) because of the prevalence of fences as physical demarcation between parcels. However, recognising demarcation lines in vegetated areas is difficult. In

Figure 13(b) with 1m resolution, some physical demarcation lines were observed in the vegetated areas, but this is insufficient in demarcating peri-urban areas with the level of accuracy required. Identifying and demarcating boundaries, especially fences, come with ease in

Figure 14(c). Non-linear features such as water tanks and wells that often lie close to boundaries were also easily identified and can aid in the demarcation process of properties in this context. The difference between

Figure 14(c) of 0.1m resolution and

Figure 14(d) of 0.05m resolution remains unperceivable with visual examination at this scale.

Figure 15 is a clip from the peri-urban informal settlement of Atinkankan. The clip presents a typical slum within the urban context containing small and closely packed buildings. The

Figure 15(a) 1m resolution image is blurry, and the non-presence of physical demarcation that characterises the area necessitates alternative approaches from using the 1m resolution image difficult for identifying property boundaries. In addition, fences and other boundary demarcation objects remain uneasily recognisable on the 0.5m resolution image of

Figure 15(b). Footpaths, building edges and other delineating features are easily perceived on

Figure 15(c) of 0.1m resolution. This highlights the need for at least a 0.1m resolution image to aid aerial imagery delineation in slum-like urban centres. At the scale of observation, no clear difference was observed between resolutions of 0.1 and 0.05m.

Figure 16 is a clip from Okebola, representing formal urban settlement. The patterned arrangement makes boundary lines easily discernible. Although images of 1m and 0.5m resolution are blurry, the regular pattern makes recognizing linear boundary patterns possible. In

Figure 16 (a), boundaries appear blurry but recognizable. However, the required level of accuracy for demarcating properties in an urban context and the potential risk of inaccurate information, owing to the value and quest for land in the area, makes it difficult to use a 1m resolution image for boundary delineation. Recognizing features became better with 0.5m resolution image in

Figure 16 (b). However, smaller point features like wells, electric poles, etc., are still not quite visible.

Figure 16 (c), recognizing boundary demarcation features came with ease. Differences were not observed between 0.1m and 0.05m resolution imageries at the scale adopted for visual perception.

In the orthomosaics, it is easier to identify features such as holes between fences and pillars at higher resolutions of 0.1 and 0.05m. In 0.5m imagery, it becomes difficult to distinguish features like beacons or holes in fences, but patterns and intersections of linear features, especially fences, help to identify demarcation points. For 1m imagery, most demarcation features are not easily identified, thereby hampering boundary delineation processes. At this resolution, delineation is possible only while working at a much smaller scale, which often makes the digitization less accurate. Ultimately, the recognisability of physical boundaries on aerial imageries aids the correct delineation of features for cadastral mapping purposes.

3.3.3. Differences in Delineating Cadastral Boundaries at Various Resolutions

RMSE is the error or discrepancy between observed values and reference values. The RMSE gives a sense of overall error magnitude, with larger values indicating potentially poorer accuracy. Using the coordinates extracted from the 0.05m resolution imageries as a reference, the RMSE of points delineated from 0.1, 0.5 and 1m resolution imageries were calculated for Aaye-Oja, Igedora, Aaye, Maryland, Atinkankan and Okebola.

Table 3 shows the characteristics of boundaries observed and the RMSE obtained from the 10 points delineated within a 1-hectare area in the six contexts.

The tables showing the RMSE computed from each observation before it was aggregated on

Table 3 is shown in the

Appendix C section.

The absolute comparison conducted at Egbewa GRA using RTK GNSS derived coordinates as reference yielded RMSE values of 0.194m and 0.206m for 0.05m and 0.1m aerial imageries. The GNSS observed coordinates and coordinates from multi-resolution orthomosaics are contained in

Table 4 and

Table 5. Notably, these values exhibit a significant increase in RMSE compared to the relative comparison values, highlighting the inaccuracies introduced by comparing data from two distinct observation methods (GNSS and aerial imagery). Also, the impact of PT1B, PT2B and PT8 which could be regarded as outliers could have contributed to the significant discrepancy. However, when the 3 data were excluded from the RMSE calculations, 0.133 and 0.152m RMSE values were obtained, whcich makes the values closer to the relative comparison conducted. This discrepancy emphasizes the importance of considering the differences in measurement techniques when evaluating positional accuracy.

Also, the result of the NPAE computed to show the effects of the coordinates delineated from different resolutions of imageries on the sizes of the parcels is shown on

Table 6. The cross-coordinate procedure adopted for parcel area calculation is also shown in the

Appendix C section of the report.

Lower values of RMSE indicate better accuracy and precision. Generally, as image resolution decreases from 0.1m to 1m, the RMSE values tend to increase. This is because lower resolutions result in less detailed images, leading to less accurate measurements. However, some sites exhibit more sensitivity to resolution changes than others, depending on the complexity of the features present within them. Sites with more complex features or boundaries, such as Aaye-Oja and Igedora, tend to have higher RMSE values compared to sites with simpler features, such as Okebola.

Table 6.

NPAE from Multi-resolution Imageries in various Geographical Contexts.

Table 6.

NPAE from Multi-resolution Imageries in various Geographical Contexts.

| Site |

Area in squared meters (m2) |

Absolute Error in squared meters (m2) |

Absolute Error Normalized to 1000 square meters (m2) |

| |

0.05m |

0.1m |

0.5m |

1m |

0.1 |

0.5 |

1 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

1 |

| Aaye-Oja |

994.028 |

984.066 |

986.359 |

1024.062 |

9.962 |

7.670 |

30.034 |

10.022 |

7.716 |

30.214 |

| Igedora |

726.928 |

728.452 |

747.314 |

796.060 |

1.524 |

20.386 |

69.133 |

2.097 |

28.044 |

95.102 |

| Aaye |

888.676 |

890.272 |

908.521 |

869.699 |

1.596 |

19.845 |

18.978 |

1.796 |

22.331 |

21.355 |

| Maryland |

1056.242 |

1054.463 |

1064.629 |

1072.923 |

1.779 |

8.387 |

16.681 |

1.684 |

7.940 |

15.793 |

| Atinkankan |

111.578 |

109.441 |

100.784 |

110.586 |

2.136 |

10.794 |

0.991 |

19.148 |

96.737 |

8.884 |

| Okebola |

1026.079 |

1027.764 |

1037.476 |

1079.781 |

1.685 |

11.396 |

53.702 |

1.642 |

11.107 |

52.337 |

Informal settlements often lack formal planning, leading to irregular and complex boundaries that are non-easily discernible. The higher RMSE values for Aaye-Oja and Atinkankan could be attributed to the complexity of features such as road intersections, farm edges, and culvert edges, which are less discernible when compared to more organised and well-defined physical boundaries such as fences, which results in lower RMSE typical of Okebola and Maryland.

The absolute errors represent the discrepancies between the observed parcel sizes and the reference sizes of 0.05m2, with lower values indicating greater positional accuracy. The absolute errors of different sizes observed across 0.1, 0.5 and 1m resolution imageries were normalised to 1000m2 to allow for a fair comparison. The trend observed across formal geographical contexts, where fences served as physical demarcations aiding easy delineation, was more consistent than that observed across informal contexts. The 0.1m resolution had a mean normalised absolute error of 1.807m2 in the formal context, while the 1m resolution had the highest inaccuracy.

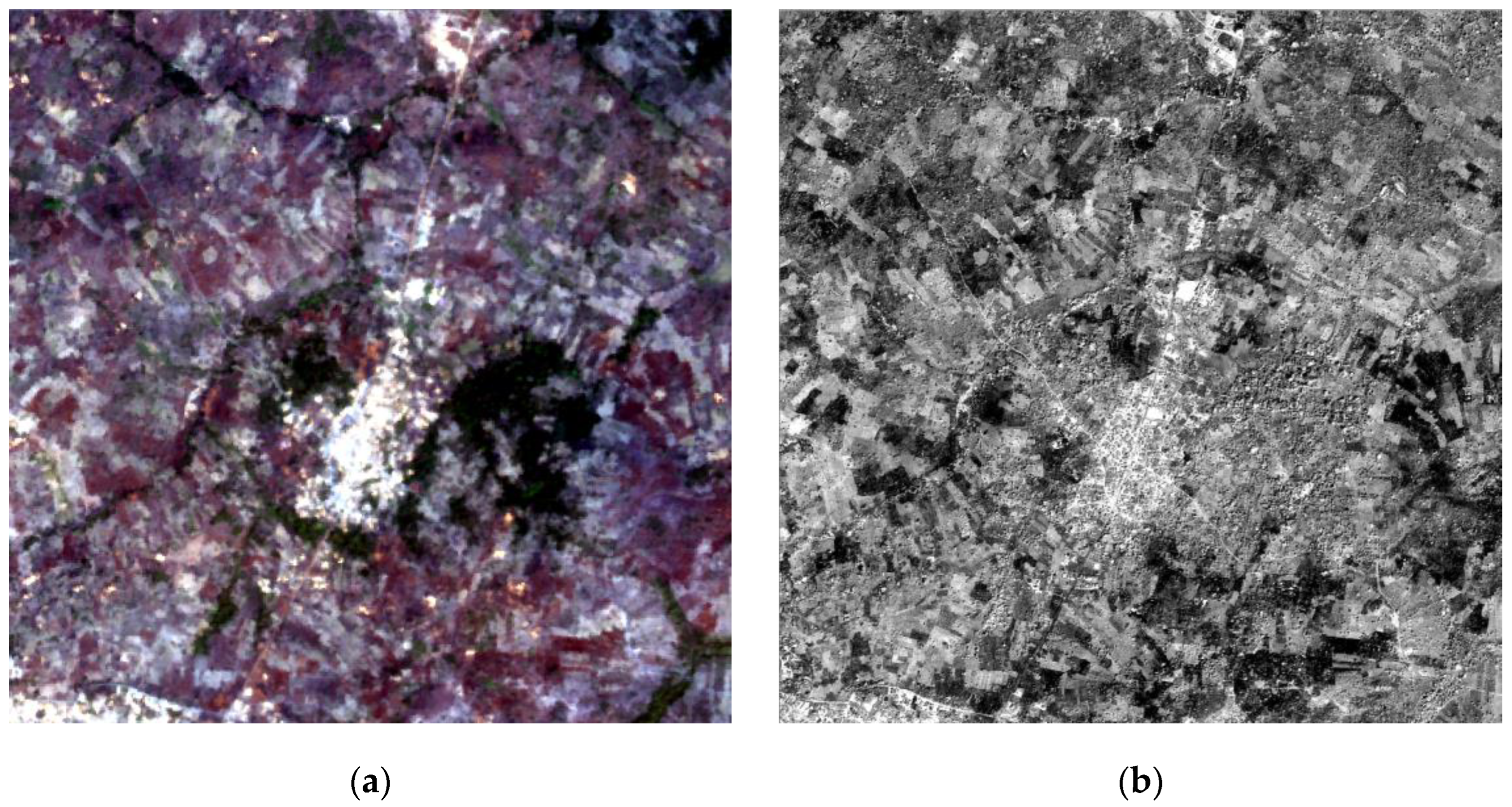

3.3.4. Differences in UAV Orthomosaic and Satellite Imagery for Cadastral Mapping

Freely available 2.1 and 3.5m resolution satellite imageries acquired from NASRDA were compared with the high-resolution orthomosaic aerial imageries produced from the UAV flights for cadastral mapping purposes. The results agree with existing research that UAV orthomosaics typically have a much higher spatial resolution than satellite imagery, allowing for more detailed and accurate mapping.[

16]. UAV orthomosaics generally provide spatially explicit detail compared to satellite imagery. UAV imageries are subjected to lesser levels of atmospheric distortions when compared with Satellite imagery. UAV imageries also allow for the high temporal resolution required for cadastral map updating [

19,

22,

23]. Maps made from the 2.1 and 3.5m resolution satellite imageries clipped at 1:20,000 visualisation scale of QGIS 2.14.17 for Aaye-Oja Ekiti are shown in

Figure 17. Large farms are visible on both imageries but more visible on the 2.1m panchromatic imagery than on the 3.6 multispectral image. However, the boundaries of the farms remain unclear because of the low spatial resolution of the imageries. In addition, small farms as those visible in

Figure 11(b

), Figure 11(c) and

Figure 11(d) cannot be seen in the satellite imagery.

As found in existing body of knowledge, UAV orthomosaics can be captured more frequently than satellite imagery, providing up-to-date information for cadastral mapping. UAVs are cost-effective for mapping small areas while satellite imageries are more cost-effective in mapping large areas. However, with the development of fixed wing UAVs with ability to take longer flights, UAVs are becoming increasingly cost-effective for mapping large areas than buying satellite imagery data acquisition. UAV orthomosaics can be produced for specific areas of interest, while satellite imagery typically covers larger areas. UAV orthomosaics can be captured and processed more quickly than satellite imagery, providing faster access to information for cadastral mapping [

16,

22]. UAV flights are restricted in certain places while satellite imageries are easily utilised without restrictions in various applications. The results are tabulated for clarity in

Table 7.

4. Discussions

4.1. Leveraging UAVs for Cadastral Mapping

The results of the interview and survey provided insights into the factors influencing the adoption of UAVs for cadastral mapping in Nigeria. Key findings from the result include:

Awareness and Education: The high level of awareness among respondents (55% very aware, 38.3% moderately aware) suggests that there is a growing recognition of the potential of UAVs in land administration. However, the relatively lower percentage of respondents who received formal education or training in UAVs (56.7%) indicates a need for increased accessibility to formal training programs.

Perceived Benefits: The perceived benefits of UAVs, particularly in terms of time efficiency and enhanced data resolution, are consistent with previous studies[

22]. These findings reinforce the notion that UAVs offer significant advantages over traditional methods of cadastral mapping.

Concerns and Challenges: The primary concerns identified by respondents include; the cost of UAV technology and regulatory challenges. These findings highlight the need for policymakers and industry stakeholders to address these concerns in order to facilitate wider adoption of UAVs. The recurring challenges identified by respondents, such as licensing and certification, security and regulatory restrictions, cost factors, knowledge and expertise, and government policies, are consistent with previous studies[

18,

22]. These challenges pose significant barriers to the adoption of UAVs and need to be addressed in order to unlock the full potential of this technology.

4.2. Fitness of Multi-Resolution Aerial Imageries for Cadastral Mapping

The delineation of features significantly depends on the availability and recognisability of physical objects that delineate the parcels based on the imagery produced. This study considered varying resolutions of aerial imageries and compared the outcomes across rural, peri-urban, and urban areas, shedding light on the suitability of aerial imageries for cadastral mapping. Considering the settlement characteristics, resolution impact on mapping, image size and computational implications and the differences between UAV orthomosaics and satellite imageries, the study drew conclusions on the fitness of UAVs and Aerial Imageries for cadastral mapping in Nigeria and similar developing countries. The visual representations in Error! Reference source not found. showcase the distinct characteristics of the settlements mapped.

The analysis of aerial imagery at resolutions of 0.05m, 0.1m, 0.5m, and 1m provides crucial insights into the fitness of different resolutions for mapping purposes. The comparisons demonstrated with

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 shows that as resolution increases, the clarity of features improves, making finer details and boundary demarcations more discernible. This is particularly important for accurately delineating property boundaries, identifying features like wells and electric poles, and ensuring precise mapping in various settlement types. The analysis of RMSE and NPAE also provides important insights into the suitability of the multi-resolution aerial imagery for cadastral mapping in multi-contextual geographical scenarios. The lower RMSE and NPAE values indicate higher accuracy of the mapped features and can be used to assess the fitness of the different resolution images for mapping purposes.

The comparison between UAV ortho mosaics and satellite imagery revealed the advantages of UAV technology for cadastral mapping. UAV ortho mosaics exhibited higher resolution, allowing for more detailed and accurate mapping. The UAV data also offered more frequent updates, cost-effectiveness for smaller areas, and faster data collection and processing. However, satellite imagery of between 0.5 and 0.1m was deemed more cost-effective for large-area mapping.

4.3. Practical Implications and Recommendations

Physical Demarcations are Fundamental for Cadastral Boundary Delineation: In the context of general boundaries and physical boundaries for and beyond FFPLA cadastral mapping, discernibility of physical demarcations is vital in achieving accurate and precise coordinates required for avoiding conflicts.

Settlement Typology Awareness: The study emphasizes the importance of considering settlement characteristics when choosing the appropriate resolution for cadastral mapping. Different resolutions are more suitable for different settlement types. Rural areas are dominated by farmlands. Hence, the use of lower resolution imageries like the 0.5m resolution imagery can suffice. However, higher resolution imageries are required for mapping urban areas because of the dense nature of properties and the need for more accurate spatial data.

UAV Advantages for Cadastral Mapping: The study underscores the advantages of UAV orthomosaics over satellite imagery in terms of resolution, accuracy, and flexibility. This necessitates the creation of pathways for the sustainable use of UAVs for professional purposes.

Regulatory Considerations: The study hints at restrictions on UAV flights for professionals, emphasising the need for policymakers to address regulatory challenges hindering UAV technology's widespread use by professionals. Professionals should be licensed and allowed to use the UAVs responsibly when needed.

For land administration purposes, where the need to fast-track land registration has become urgent, leveraging 0.5m image resolution to minimise cost and maximise efficiency becomes very vital.

4.4. Limitations and Recommendations for Further Studies

The study aims to assess the suitability of multi-resolution aerial imageries for cadastral mapping in both informal and formal contexts within rural, peri-urban, and urban areas. This work focuses on human delineation as against Automatic Feature Extraction procedures. Specifically, the investigation focused on UAV imageries at resolutions of 0.05m, 0.1m, 0.5m, and 1m, along with satellite imageries at 2.1m and 3.5m.

In this study, emphasis was placed on the identification of fences and other linear features. The identification of beacons was not the primary focus, even though 40 x 40 cm second-order control beacons were identified on the 0.5m and higher resolution images of Igedora. The potential for property beacon identification using aerial imageries, akin to automatic feature extraction, is earmarked for exploration in future research. Also, the presence of trees impedes easy boundary demarcation with aerial imagery,, necessitating field visits in such circumstances.

Aside from other recommendations for further studies implied in previous sections, in this study, it was identified that there were no discernible distinctions between aerial imagery resolutions of 0.1m and 0.05m in terms of human identification of boundaries at the 1:500 visualisation scale that was used. However, when observed at a larger scale of 1:125 during delineation, some distinctions became apparent between imageries with 0.1m and 0.05m resolutions. The identification of distinctions between very high-resolution imageries can be further explored in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.T., O.I., S.O and M.K; methodology, I.T. and MK.; software, I.T.; validation, I.T.; formal analysis, I.T.; investigation, I.T.; resources, I.T.; data curation, I.T; writing—original draft preparation, I.T; writing—review and editing, I.T., O.I., S.O and M.K; visualization, I.T.; supervision, I.T., O.I., S.O and MK.; project administration, I.T.; funding acquisition, I.T and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 2.

Perceived Benefits of UAV Use for Land Administration in Nigeria.

Figure 2.

Perceived Benefits of UAV Use for Land Administration in Nigeria.

Figure 3.

Concerns and Challenges Perceived in Adopting UAVs for Land Administration and Management in Nigeria.

Figure 3.

Concerns and Challenges Perceived in Adopting UAVs for Land Administration and Management in Nigeria.

Figure 4.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Aaye-Oja Ekiti (Rural and Informal Settlement).

Figure 4.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Aaye-Oja Ekiti (Rural and Informal Settlement).

Figure 5.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Igedora-Ekiti (Rural and Formal Settlement).

Figure 5.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Igedora-Ekiti (Rural and Formal Settlement).

Figure 6.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Aaye Community (Peri-Urban and Informal Settlement).

Figure 6.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Aaye Community (Peri-Urban and Informal Settlement).

Figure 7.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Maryland Avenue (Peri-urban and Formal Settlement).

Figure 7.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Maryland Avenue (Peri-urban and Formal Settlement).

Figure 8.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Atinkankan (Urban and Informal Settlement - Slum).

Figure 8.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Atinkankan (Urban and Informal Settlement - Slum).

Figure 9.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Okebola (Urban and Formal Settlement).

Figure 9.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Okebola (Urban and Formal Settlement).

Figure 10.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Egbewa GRA (Urban and Formal Settlement) annotated with GNSS Marker positions for Absolute Accuracy Comparism.

Figure 10.

UAV Orthomosaic of Part of Egbewa GRA (Urban and Formal Settlement) annotated with GNSS Marker positions for Absolute Accuracy Comparism.

Figure 11.

Comparison of Spatial Resolutions for Rural Agricultural Area. (a) 1m; (b) 0.5m; (c) 0.1m; (d) 0.05m.

Figure 11.

Comparison of Spatial Resolutions for Rural Agricultural Area. (a) 1m; (b) 0.5m; (c) 0.1m; (d) 0.05m.

Figure 12.

Comparison of Spatial Resolutions for Rural Formal Settlement. (a) 1m; (b) 0.5m; (c) 0.1m; (d) 0.06m.

Figure 12.

Comparison of Spatial Resolutions for Rural Formal Settlement. (a) 1m; (b) 0.5m; (c) 0.1m; (d) 0.06m.

Figure 13.

Comparison of Spatial Resolutions for Peri-Urban informal Settlement. (a) 1m; (b) 0.5m; (c) 0.1m; (d) 0.06m.

Figure 13.

Comparison of Spatial Resolutions for Peri-Urban informal Settlement. (a) 1m; (b) 0.5m; (c) 0.1m; (d) 0.06m.

Figure 14.

Comparison of Spatial Resolutions for Peri-Urban Formal Settlement. (a) 1m; (b) 0.5m; (c) 0.1m; (d) 0.05m.

Figure 14.

Comparison of Spatial Resolutions for Peri-Urban Formal Settlement. (a) 1m; (b) 0.5m; (c) 0.1m; (d) 0.05m.

Figure 15.

Comparison of Spatial Resolutions for Urban Informal Settlement (Slum). (a) 1m; (b) 0.5m; (c) 0.1m; (d) 0.05m.

Figure 15.

Comparison of Spatial Resolutions for Urban Informal Settlement (Slum). (a) 1m; (b) 0.5m; (c) 0.1m; (d) 0.05m.

Figure 16.

Comparison of Spatial Resolutions for Urban Formal Settlement. (a) 1m; (b) 0.5m; (c) 0.1m; (d) 0.05m.

Figure 16.

Comparison of Spatial Resolutions for Urban Formal Settlement. (a) 1m; (b) 0.5m; (c) 0.1m; (d) 0.05m.

Figure 17.

Satellite Imageries of Aaye-Oja Ekiti, Clipped at a 1:20,000 Visualization scale on QGIS (a) 3.5m resolution Multispectral Image (b) 2.1m Resolution Panchromatic Image.

Figure 17.

Satellite Imageries of Aaye-Oja Ekiti, Clipped at a 1:20,000 Visualization scale on QGIS (a) 3.5m resolution Multispectral Image (b) 2.1m Resolution Panchromatic Image.

Table 2.

Survey Population Characteristics.

Table 2.

Survey Population Characteristics.

| Variable |

Options |

Response |

| |

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Occupation |

Surveyor |

54 |

90 |

| GIS Specialist |

22 |

36.7 |

| Land Administrator |

6 |

10 |

| Others |

5 |

8.3 |

| Practice Domain |

Professional Practice |

41 |

68.3 |

| Academic |

15 |

25 |

| Government |

9 |

15 |

| Others |

4 |

6.7 |

| Category |

Surveying Student |

3 |

5 |

| Young Surveyor |

19 |

31.7 |

| Professional |

40 |

66.7 |

| Others |

4 |

6.7 |

| Years of Experience |

Less than 1 year |

2 |

3.3 |

| 1-5 years |

10 |

16.7 |

| 6-10 years |

23 |

38.3 |

| More than 10 years |

25 |

41.7 |

Table 3.

RMSE of Points Delineated from Multi-Resolution UAV Imageries.

Table 3.

RMSE of Points Delineated from Multi-Resolution UAV Imageries.

| Site |

Description |

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) |

| |

|

0.1m |

0.5m |

1m |

| Aaye-Oja |

General Boundaries from informal settlement comprising road intersections and farm edges |

0.190 |

0.613 |

2.572 |

| Igedora |

Mix of physical and general boundaries determined from fences and farm edges |

0.142 |

0.740 |

2.501 |

| Aaye |

Mix of physical and general boundaries determined from fences, road and farm edges |

0.075 |

0.680 |

1.543 |

| Maryland |

Physical Boundaries from fences |

0.053 |

1.332 |

1.417 |

| Atinkankan |

Physical and general boundaries extracted from fences, and culvert edges |

0.157 |

0.570 |

1.491 |

| Okebola |

Physical boundaries from fences |

0.106 |

0.535 |

1.121 |

| |

Average RMSE Values |

0.117 |

0.737 |

1.747 |

Table 4.

RMSE between GNSS Derived Coordinates and 0.05m Resolution Orthomosaic.

Table 4.

RMSE between GNSS Derived Coordinates and 0.05m Resolution Orthomosaic.

| |

GNSS Survey |

0.05 Orthomosaic |

|

|

|

|

| Point ID |

Northings (m) |

Eastings(m) |

Northings (m) |

Eastings(m) |

N0.05 - NGNSS (m) |

E0.05 – EGNSS (m) |

(N0.05 – NGNSS)2 (m2) |

(E0.05 – EGNSS)2 (m2) |

| PT1 |

843316.647 |

743574.247 |

843316.685 |

743574.355 |

0.038 |

0.108 |

0.001 |

0.012 |

| PT1A |

843294.853 |

743577.607 |

843294.833 |

743577.497 |

-0.020 |

-0.110 |

0.000 |

0.012 |

| PT1B |

843339.240 |

743572.166 |

843339.191 |

743572.457 |

-0.049 |

0.291 |

0.002 |

0.085 |

| PT2 |

843294.353 |

743854.335 |

843294.354 |

743854.243 |

0.001 |

-0.092 |

0.000 |

0.009 |

| PT2B |

843280.579 |

743881.948 |

843280.744 |

743881.692 |

0.165 |

-0.256 |

0.027 |

0.066 |

| PT2C |

843301.188 |

743828.457 |

843301.198 |

743828.436 |

0.010 |

-0.021 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| PT5A |

843408.008 |

743795.789 |

843407.863 |

743795.802 |

-0.145 |

0.013 |

0.021 |

0.000 |

| PT5B |

843427.010 |

743674.443 |

843427.006 |

743674.616 |

-0.004 |

0.173 |

0.000 |

0.030 |

| PT6 |

843873.704 |

743576.325 |

843873.817 |

743576.238 |

0.113 |

-0.087 |

0.013 |

0.008 |

| PT6A |

843881.845 |

743555.280 |

843881.930 |

743555.405 |

0.085 |

0.125 |

0.007 |

0.016 |

| PT6B |

843864.870 |

743599.227 |

843865.023 |

743599.145 |

0.153 |

-0.082 |

0.023 |

0.007 |

| PT8 |

843733.918 |

743798.118 |

843733.633 |

743797.940 |

-0.285 |

-0.178 |

0.081 |

0.032 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.122 |

0.151 |

| |

|

|

|

|

0.05 RMSE: |

0.194 |

|

Table 5.

RMSE between GNSS Derived Coordinates and 0.1m Resolution Orthomosaic.

Table 5.

RMSE between GNSS Derived Coordinates and 0.1m Resolution Orthomosaic.

| |

GNSS Survey |

0.1 Orthomosaic |

|

|

|

|

| Point ID |

Northings (m) |

Eastings(m) |

Northings (m) |

Eastings(m) |

(m)N0.1 - NGNSS (m) |

E0.1 – EGNSS (m) |

(N0.1 – NGNSS)2 (m2) |

(E0.1 – EGNSS)2 (m2) |

| PT1 |

843316.647 |

743574.247 |

843316.6722 |

743574.3841 |

0.025 |

0.137 |

0.001 |

0.019 |

| PT1A |

843294.853 |

743577.607 |

843294.8272 |

743577.4969 |

-0.026 |

-0.110 |

0.001 |

0.012 |

| PT1B |

843339.240 |

743572.166 |

843339.1871 |

743572.4427 |

-0.053 |

0.277 |

0.003 |

0.077 |

| PT2 |

843294.353 |

743854.335 |

843294.3714 |

743854.2452 |

0.018 |

-0.090 |

0.000 |

0.008 |

| PT2B |

843280.579 |

743881.948 |

843280.7391 |

743881.697 |

0.160 |

-0.251 |

0.026 |

0.063 |

| PT2C |

843301.188 |

743828.457 |

843301.1808 |

743828.3991 |

-0.007 |

-0.058 |

0.000 |

0.003 |

| PT5A |

843408.008 |

743795.789 |

843407.8339 |

743795.8027 |

-0.174 |

0.014 |

0.030 |

0.000 |

| PT5B |

843427.010 |

743674.443 |

843426.9763 |

743674.6424 |

-0.034 |

0.199 |

0.001 |

0.040 |

| PT6 |

843873.704 |

743576.325 |

843873.8234 |

743576.1993 |

0.119 |

-0.126 |

0.014 |

0.016 |

| PT6A |

843881.845 |

743555.280 |

843881.9251 |

743555.3949 |

0.080 |

0.115 |

0.006 |

0.013 |

| PT6B |

843864.870 |

743599.227 |

843865.026 |

743599.0956 |

0.156 |

-0.131 |

0.024 |

0.017 |

| PT8 |

843733.918 |

743798.118 |

843733.6282 |

743797.8981 |

-0.290 |

-0.220 |

0.084 |

0.048 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.126 |

0.162 |

| |

|

|

|

|

0.1 RMSE: |

0.206 |

|

Table 7.

Comparism between UAV Orthophoto and Satellite Imagery for Cadastral Mapping.

Table 7.

Comparism between UAV Orthophoto and Satellite Imagery for Cadastral Mapping.

| Factors |

UAV |

Satellite Imagery |

| Resolution |

Higher Resolutions (0.01m) can be achieved |

Usually of lower resolutions |

| Area |

Usually for small areas |

Wide-coverage aids synoptic view |

| Cost |

Cost-effective for small areas |

Cost effective for large areas |

| Regulations |

Restrictions, especially in Urban Areas |

No restrictions |

| Flexibility |

Ease of data collection aids high-temporal resolution for real-time data collection |

Low-temporal resolution |

| |

|

|