Submitted:

17 August 2024

Posted:

20 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

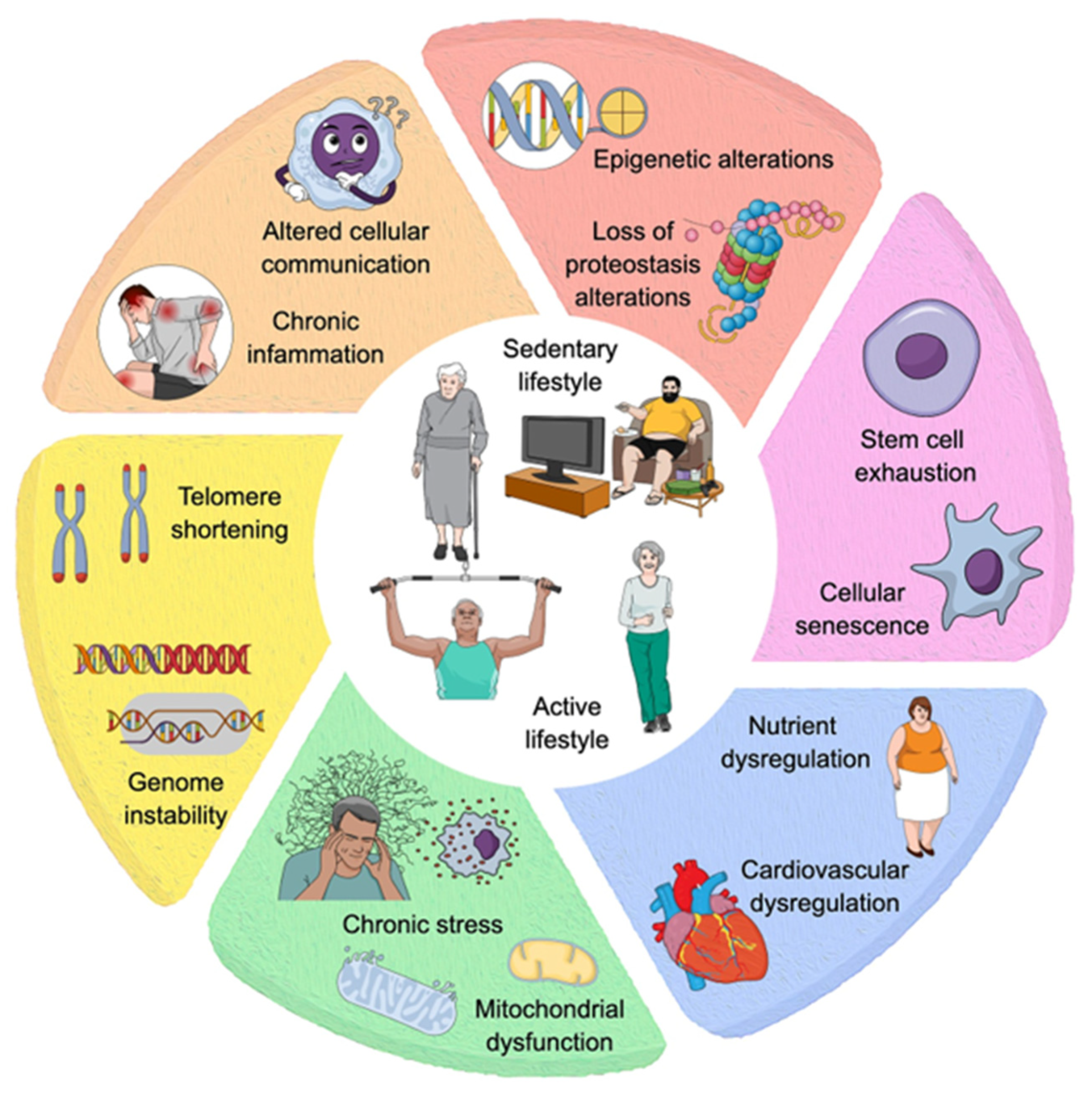

2. Cognitive Decline Risk Factors and Aging Models

3. Multivariate Influences and Variability in Age-Related Cognitive Decline

4. Molecular Determinants of Cognitive Reserve, Resilience, and Age-Related Cognitive Decline

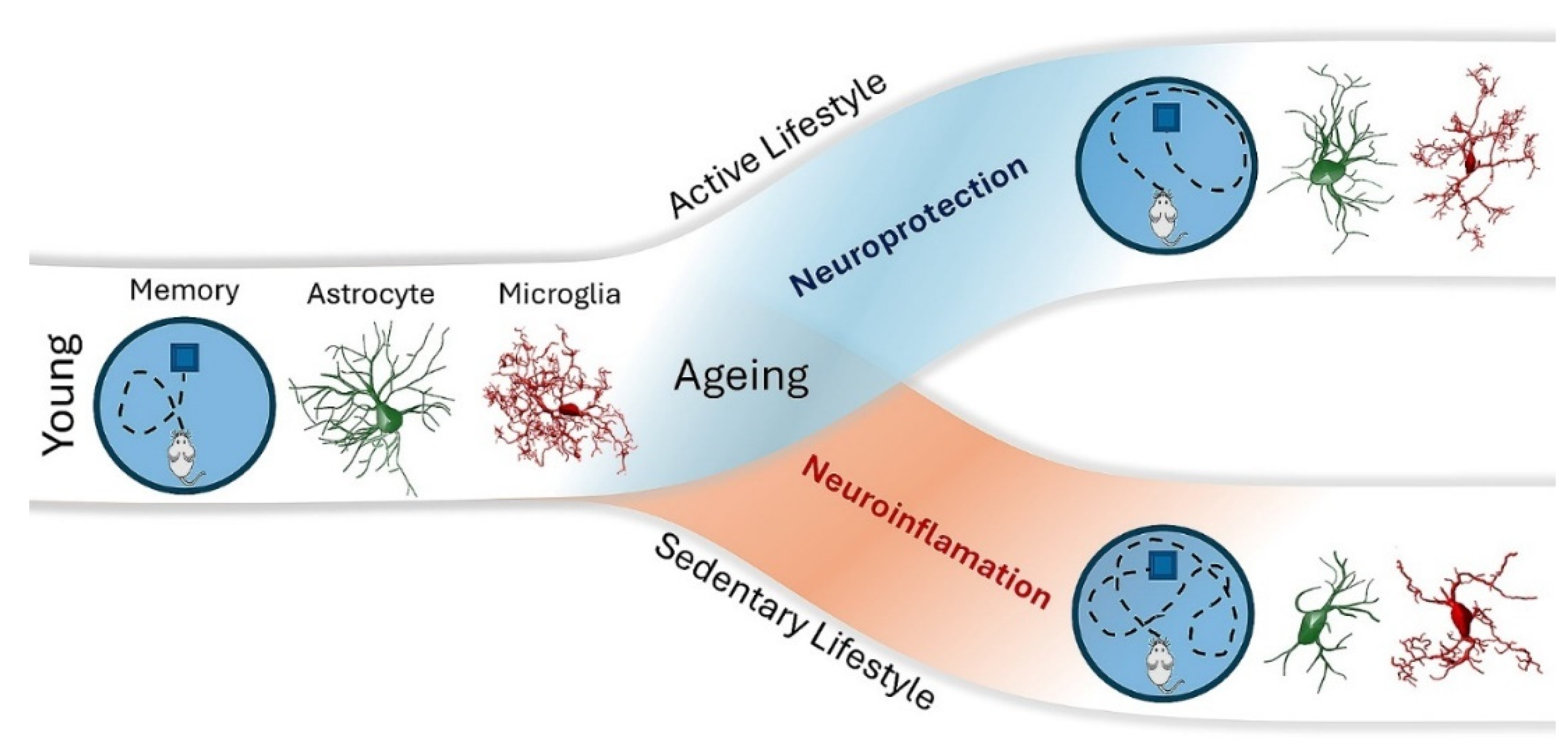

5. Neuroinflammation, Exercise, and Cognitive Variability in Old Age

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbott, R.A.; Skirrow, C.; Jokisch, M.; Timmers, M.; Streffer, J.; van Nueten, L.; Krams, M.; Winkler, A.; Pundt, N.; Nathan, P.J.; et al. Normative data from linear and nonlinear quantile regression in CANTAB: Cognition in mid-to-late life in an epidemiological sample. Alzheimer's Dementia: Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2018, 11, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahadi, S.; Zhou, W.; Rose, S.M.S.-F.; Sailani, M.R.; Contrepois, K.; Avina, M.; Ashland, M.; Brunet, A.; Snyder, M. Personal aging markers and ageotypes revealed by deep longitudinal profiling. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHarkan, K.; Sultana, N.; Al Mulhim, N.; AlAbdulKader, A.M.; Alsafwani, N.; Barnawi, M.; Alasqah, K.; Bazuhair, A.; Alhalwah, Z.; Bokhamseen, D.; et al. Artificial intelligence approaches for early detection of neurocognitive disorders among older adults. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1307305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.L.; Du, M.; Cosentino, S.; Schupf, N.; Rosso, A.L.; Perls, T.T.; Sebastiani, P. ; the Long Life Family Study Slower Decline in Processing Speed Is Associated with Familial Longevity. Gerontology 2021, 68, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, N.D. State of the science on mild cognitive impairment (MCI). CNS Spectrums 2019, 24, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antignano, I.; Liu, Y.; Offermann, N.; Capasso, M. Aging microglia. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attalla, D.; Schatz, A.; Stumpenhorst, K.; Winter, Y. Cognitive training of mice attenuates age-related decline in associative learning and behavioral flexibility. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1326501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aunan, J.R.; Watson, M.M.; Hagland, H.R.; Søreide, K. Molecular and biological hallmarks of ageing. Br. J. Surg. 2016, 103, e29–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, S.; Haque, E.; Balakrishnan, R.; Kim, I.-S.; Choi, D.-K. The Ageing Brain: Molecular and Cellular Basis of Neurodegeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, S.; Haque, E.; Kim, I.-S.; Choi, D.-K. Microglial Turnover in Ageing-Related Neurodegeneration: Therapeutic Avenue to Intervene in Disease Progression. Cells 2021, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.R.; Officer, A.; de Carvalho, I.A.; Sadana, R.; Pot, A.M.; Michel, J.-P.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; Epping-Jordan, J.E.; Peeters, G.M.E.E.G.; Mahanani, W.R.; et al. The World report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.; Livesey, P.; Meyer, J. Environmental enrichment influences survival rate and enhances exploration and learning but produces variable responses to the radial maze in old rats. Dev. Psychobiol. 2009, 51, 564–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellenguez, C.; Kucukali, F.; Jansen, I.E.; Kleineidam, L.; Moreno-Grau, S.; Amin, N.; Naj, A.C.; Campos-Martin, R.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Andrade, V.; et al. New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 412–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento-Torres, N.; Bento-Torres, J.; Tomás, A.; Costa, V.; Corrêa, P.; Costa, C.; Jardim, N.; Picanço-Diniz, C. Influence of schooling and age on cognitive performance in healthy older adults. Braz. J. Med Biol. Res. 2017, 50, e5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, F.C.B.; Tofolo, M.V.; Nunes-Souza, E.; Marchi, R.; Okano, L.M.; Ruthes, M.; Rosolen, D.; Malheiros, D.; Fonseca, A.S.; Cavalli, L.R. Extracellular vesicles-associated miRNAs in triple-negative breast cancer: from tumor biology to clinical relevance. Life Sci. 2024, 336, 122332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettio, L.E.; Rajendran, L.; Gil-Mohapel, J. The effects of aging in the hippocampus and cognitive decline. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 79, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielak, A.A.M.; Gerstorf, D.; Anstey, K.J.; Luszcz, M.A. Longitudinal associations between activity and cognition vary by age, activity type, and cognitive domain. Psychol. Aging 2014, 29, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieri, G.; Schroer, A.B.; Villeda, S.A. Blood-to-brain communication in aging and rejuvenation. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Ibrahim, M.Z.; Benoy, A.; Sajikumar, S. Long-term plasticity in the hippocampus: maintaining within and ‘tagging’ between synapses. FEBS J. 2021, 289, 2176–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, E.H.; Epel, E.S.; Lin, J. Human telomere biology: A contributory and interactive factor in aging, disease risks, and protection. Science 2015, 350, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, N.C.B.S.; Barha, C.K.; Erickson, K.I.; Kramer, A.F.; Liu-Ambrose, T. Physical exercise, cognition, and brain health in aging. Trends Neurosci. 2024, 47, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgeest, G.S.; Henson, R.N.; Shafto, M.; Samu, D.; Can, C.; Kievit, R.A. Greater lifestyle engagement is associated with better age-adjusted cognitive abilities. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0230077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourassa, K.J.; Memel, M.; Woolverton, C.; Sbarra, D.A. Social participation predicts cognitive functioning in aging adults over time: comparisons with physical health, depression, and physical activity. Aging Ment. Heal. 2015, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Boyle, P.; Wang, T.; Yu, L.; Wilson, R.S.; Dawe, R.; Arfanakis, K.; A Schneider, J.; A Bennett, D. To what degree is late life cognitive decline driven by age-related neuropathologies? Brain 2021, 144, 2166–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branigan, K.S.; Dotta, B.T. Cognitive Decline: Current Intervention Strategies and Integrative Therapeutic Approaches for Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brites, D. Regulatory function of microRNAs in microglia. Glia 2020, 68, 1631–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brites, D.; Fernandes, A. Neuroinflammation and Depression: Microglia Activation, Extracellular Microvesicles and microRNA Dysregulation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, D.; MacDonald, S.W.; Hultsch, D.F. Inconsistency in serial choice decision and motor reaction times dissociate in younger and older adults. Brain Cogn. 2004, 56, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureš, Z.; Bartošová, J.; Lindovský, J.; Chumak, T.; Popelář, J.; Syka, J. Acoustical enrichment during early postnatal development changes response properties of inferior colliculus neurons in rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014, 40, 3674–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabeza, R.; Albert, M.; Belleville, S.; Craik, F.I.M.; Duarte, A.; Grady, C.L.; Lindenberger, U.; Nyberg, L.; Park, D.C.; Reuter-Lorenz, P.A.; et al. Maintenance, reserve and compensation: the cognitive neuroscience of healthy ageing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeira, C.; Cunha, C.; Vaz, A.R.; Falcão, A.S.; Barateiro, A.; Seixas, E.; Fernandes, A.; Brites, D. Key Aging-Associated Alterations in Primary Microglia Response to Beta-Amyloid Stimulation. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeira, C.; Oliveira, A.F.; Cunha, C.; Vaz, A.R.; Falcão, A.S.; Fernandes, A.; Brites, D. Microglia change from a reactive to an age-like phenotype with the time in culture. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, D.; Navarro, E. Differences in cognitive performance, level of dependency and quality of life (QoL), related to age and cognitive status in a sample of Spanish old adults under and over 80 years of age. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 53, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Lin, J.; Xiang, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Liao, W.; Jiang, T. Physical Exercise-Induced Astrocytic Neuroprotection and Cognitive Improvement Through Primary Cilia and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases Pathway in Rats With Chronic Cerebral Hypoperfusion. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 866336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, C.; Balboni, E.; Beltrami, D.; Gasparini, F.; Vinceti, G.; Gallingani, C.; Salvatori, D.; Salemme, S.; Molinari, M.A.; Tondelli, M.; et al. Neuroanatomical Correlates of Cognitive Tests in Young-onset MCI. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2023, 22, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlew, A.R.; Kaser, A.; Schaffert, J.; Goette, W.; Lacritz, L.; Rossetti, H. A Critical Review of Neuropsychological Actuarial Criteria for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2023, 91, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, M.G.; Nicolas, S.; Lucassen, P.J.; Mul, J.D.; O’leary, O.F.; Nolan, Y.M. Ageing, Cognitive Decline, and Effects of Physical Exercise: Complexities, and Considerations from Animal Models. Brain Plast. 2024, 9, 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; Zanon, S.; Lucas, G. Exercise-Induced MicroRNA Regulation in the Mice Nervous System is Maintained After Activity Cessation. MicroRNA 2021, 10, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casaletto, K.B.; Lindbergh, C.A.; VandeBunte, A.; Neuhaus, J.; Schneider, J.A.; Buchman, A.S.; Honer, W.G.; Bennett, D.A. Microglial Correlates of Late Life Physical Activity: Relationship with Synaptic and Cognitive Aging in Older Adults. J. Neurosci. 2021, 42, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapko, D.; McCormack, R.; Black, C.; Staff, R.; Murray, A. Life-course determinants of cognitive reserve (CR) in cognitive aging and dementia – a systematic literature review. Aging Ment. Heal. 2017, 22, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelini, G.; Pantazopoulos, H.; Durning, P.; Berretta, S. The tetrapartite synapse: a key concept in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 50, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Ghosh, A.; Lin, J.; Zhang, C.; Pan, Y.; Thakur, A.; Singh, K.; Hong, H.; Tang, S. 5-lipoxygenase pathway and its downstream cysteinyl leukotrienes as potential therapeutic targets for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, S.-H.; Jia, N.; Xie, M.; Liao, X.-M. Environmental stimulation influence the cognition of developing mice by inducing changes in oxidative and apoptosis status. Brain Dev. 2014, 36, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-T. Cognitive Reserve and the Prevention of Dementia: the Role of Physical and Cognitive Activities. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.; Zhang, B.; Luo, L.; Guo, J. The influence of healthy lifestyle behaviors on cognitive function among older Chinese adults across age and gender: Evidence from panel data. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2023, 112, 105040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, A.C. Neuroinflammation and the cGAS-STING pathway. J. Neurophysiol. 2019, 121, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clare, L.; Wu, Y.-T.; Teale, J.C.; MacLeod, C.; Matthews, F.; Brayne, C.; Woods, B. ; CFAS-Wales study team Potentially modifiable lifestyle factors, cognitive reserve, and cognitive function in later life: A cross-sectional study. PLOS Med. 2017, 14, e1002259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R. A., M. M. Marsiske, and G. E. Smith. 2019. "Neuropsychology of Aging." Handb Clin Neurol 167: 149-180. [CrossRef]

- Colavitta, M.F.; Grasso, L.; Barrantes, F.J. Environmental Enrichment in Murine Models and Its Translation to Human Factors Improving Conditions in Alzheimer Disease. J. Prev. Alzheimer's Dis. 2023, 10, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro, A.; Gomes, C.; Bicker, J.; Fortuna, A. Aging and cognitive resilience: Molecular mechanisms as new potential therapeutic targets. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 104093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, F.C.; Rode, M.P.; Vietta, G.G.; Iop, R.D.R.; Creczynski-Pasa, T.B.; Martin, A.S.; Da Silva, R. Expression levels of specific microRNAs are increased after exercise and are associated with cognitive improvement in Parkinson's disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silveira, M.P.; da Silva Fagundes, K.K.; Bizuti, M.R.; Starck, É.; Rossi, R.C.; de Resende e Silva, D.T. Physical exercise as a tool to help the immune system against COVID-19: an integrative review of the current literature. Clin. Exp. Med. 2021, 21, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahan, L.; Rampon, C.; Florian, C. Age-related memory decline, dysfunction of the hippocampus and therapeutic opportunities. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 102, 109943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauncey, M.J. Nutrition, the brain and cognitive decline: insights from epigenetics. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, V.M.d.A.; Giatti, L.; Bensenor, I.; Tiemeier, H.; Ikram, M.A.; de Figueiredo, R.C.; Chor, D.; Schmidt, M.I.; Barreto, S.M. Education plays a greater role than age in cognitive test performance among participants of the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, C.P.; Macedo, L.D.E.D.d.; de Oliveira, T.C.G.; Soares, F.C.; Bento-Torres, J.; Bento-Torres, N.V.O.; Anthony, D.C. Beneficial effects of multisensory and cognitive stimulation in institutionalized elderly: 12-months follow-up. Clin. Interv. Aging 2015, ume 10, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picanço-Diniz, C.W.; De Oliveira, T.C.G.; Soares, F.C.; Macedo, L.D.E.D.D.; Diniz, D.L.W.P.; Bento-Torres, N.V.O. Beneficial effects of multisensory and cognitive stimulation on age-related cognitive decline in long-term-care institutions. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVries, S.A.; Conner, B.; Dimovasili, C.; Moore, T.L.; Medalla, M.; Mortazavi, F.; Rosene, D.L. Immune proteins C1q and CD47 may contribute to aberrant microglia-mediated synapse loss in the aging monkey brain that is associated with cognitive impairment. GeroScience 2023, 46, 2503–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhapola, R.; Hota, S.S.; Sarma, P.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Medhi, B.; Reddy, D.H. Recent advances in molecular pathways and therapeutic implications targeting neuroinflammation for Alzheimer’s disease. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 1669–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkhuizen, S.; Van Ginneken, L.M.C.; Ijpelaar, A.H.C.; Koekkoek, S.K.E.; De Zeeuw, C.I.; Boele, H.J. Impact of enriched environment on motor performance and learning in mice. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, D.G.; Foro, C.A.R.; Rego, C.M.D.; Gloria, D.A.; De Oliveira, F.R.R.; Paes, J.M.P.; De Sousa, A.A.; Tokuhashi, T.P.; Trindade, L.S.; Turiel, M.C.P.; et al. Environmental impoverishment and aging alter object recognition, spatial learning, and dentate gyrus astrocytes. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010, 32, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinoff, A.; Herrmann, N.; Swardfager, W.; Liu, C.S.; Sherman, C.; Chan, S.; Lanctôt, K.L. The Effect of Exercise Training on Resting Concentrations of Peripheral Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): A Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0163037–e0163037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, J.; Hill, N.L. Reducing Dementia Risk: The Latest Evidence to Guide Conversations With Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2023, 49, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohnalová, L.; Lundgren, P.; Carty, J.R.E.; Goldstein, N.; Wenski, S.L.; Nanudorn, P.; Thiengmag, S.; Huang, K.-P.; Litichevskiy, L.; Descamps, H.C.; et al. A microbiome-dependent gut–brain pathway regulates motivation for exercise. Nature 2022, 612, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Vernuccio, L.; Catanese, G.; Inzerillo, F.; Salemi, G.; Barbagallo, M. Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Other Lifestyle Factors in the Prevention of Cognitive Decline and Dementia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drago, V.; Babiloni, C.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Caroli, A.; Bosch, B.; Hensch, T.; Didic, M.; Klafki, H.-W.; Pievani, M.; Jovicich, J.; et al. Disease Tracking Markers for Alzheimer's Disease at the Prodromal (MCI) Stage. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2011, 26, 159–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, A. Motivation for exercise from the gut. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earls, L.R.; Westmoreland, J.J.; Zakharenko, S.S. Non-coding RNA regulation of synaptic plasticity and memory: Implications for aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2014, 17, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggen, B.J.L.; Eggen, B.J.L. How the cGAS–STING system links inflammation and cognitive decline. Nature 2023, 620, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engeroff, T.; Ingmann, T.; Banzer, W. Physical Activity Throughout the Adult Life Span and Domain-Specific Cognitive Function in Old Age: A Systematic Review of Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1405–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, K.I.; Donofry, S.D.; Sewell, K.R.; Brown, B.M.; Stillman, C.M. Cognitive Aging and the Promise of Physical Activity. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 18, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, K.I.; Hillman, C.; Stillman, C.M.; Ballard, R.M.; Bloodgood, B.; Conroy, D.E.; Macko, R.; Marquez, D.X.; Petruzzello, S.J.; Powell, K.E.; et al. Physical Activity, Cognition, and Brain Outcomes: A Review of the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, K.I.; Voss, M.W.; Prakash, R.S.; Basak, C.; Szabo, A.; Chaddock, L.; Kim, J.S.; Heo, S.; Alves, H.; White, S.M.; et al. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3017–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, K.I.; Weinstein, A.M.; Lopez, O.L. Physical Activity, Brain Plasticity, and Alzheimer's Disease. Arch. Med Res. 2012, 43, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcon, C.; Tucholka, A.; Monté-Rubio, G.C.; Cacciaglia, R.; Operto, G.; Rami, L.; Gispert, J.D.; Molinuevo, J.L. Longitudinal structural cerebral changes related to core CSF biomarkers in preclinical Alzheimer's disease: A study of two independent datasets. NeuroImage: Clin. 2018, 19, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fjell, A.M.; Walhovd, K.B. Structural Brain Changes in Aging: Courses, Causes and Cognitive Consequences. Prog. Neurobiol. 2010, 21, 187–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas. 2016. "Glutamine in Sport and Exercise." International Journal of Medical and Biological Frontiers 22, no. 4: 277-291.

- Gaspar-Silva, F.; Trigo, D.; Magalhaes, J. Ageing in the brain: mechanisms and rejuvenating strategies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M.; Islam, R.; Kerimoglu, C.; Lancelin, C.; Gisa, V.; Burkhardt, S.; Krüger, D.M.; Marquardt, T.; Malchow, B.; Schmitt, A.; et al. Exercise as a model to identify microRNAs linked to human cognition: a role for microRNA-409 and microRNA-501. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, M.M.; Garbarino, V.R.; Pollet, E.; Palavicini, J.P.; Kellogg, D.L.; Kraig, E.; Orr, M.E. Biological aging processes underlying cognitive decline and neurodegenerative disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorus, E.; De Raedt, R.; Mets, T. Diversity, dispersion and inconsistency of reaction time measures: effects of age and task complexity. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2006, 18, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Skoufas, E.; Kanellakis, S.; Sanoudou, D.; Pavlopoulos, G.A.; Eliopoulos, A.G.; Gkouskou, K.K. Ageotypes revisited: The brain and central nervous system dysfunction as a major nutritional and lifestyle target for healthy aging. Maturitas 2023, 170, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, M.L.; Szumlinski, K.K. Impoverished rearing impairs working memory and metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 expression. NeuroReport 2008, 19, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillo, F.W.; Neves, G.; Walker, A.; Vizcay-Barrena, G.; Fleck, R.A.; Branco, T.; Burrone, J. A Distance-Dependent Distribution of Presynaptic Boutons Tunes Frequency-Dependent Dendritic Integration. Neuron 2018, 99, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.-F.; Liu, D.-X.; Zhang, Q.; Liang, F.-Y.; Dai, G.-Y.; Zeng, J.-S.; Pei, Z.; Xu, G.-Q.; Lan, Y. Voluntary Exercise Promotes Glymphatic Clearance of Amyloid Beta and Reduces the Activation of Astrocytes and Microglia in Aged Mice. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedden, T.; Gabrieli, J.D.E. Insights into the ageing mind: a view from cognitive neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertzog, C.; Kramer, A.F.; Wilson, R.S.; Lindenberger, U. Enrichment Effects on Adult Cognitive Development. Psychol. Sci. Public Interes. 2008, 9, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, M. 2019. "Tau Pet Imaging." Adv Exp Med Biol 1184: 217-230. [CrossRef]

- Hipp, M.S.; Kasturi, P.; Hartl, F.U. The proteostasis network and its decline in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseiny, S.; Pietri, M.; Petit-Paitel, A.; Zarif, H.; Heurteaux, C.; Chabry, J.; Guyon, A. Differential neuronal plasticity in mouse hippocampus associated with various periods of enriched environment during postnatal development. Anat. Embryol. 2014, 220, 3435–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Dan, X.; Babbar, M.; Wei, Y.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, S.; Chen, E.-H. Specific but not general declines in attention and executive function with aging: Converging cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence across the adult lifespan. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1108725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Wen, L.; Tan, X.; Cheng, K.; Liu, Y.; Pu, J.; Liu, L.; et al. The gut microbiome modulates the transformation of microglial subtypes. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 1611–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hultsch, D.F.; MacDonald, S.W.S.; Dixon, R.A. Variability in Reaction Time Performance of Younger and Older Adults. Journals Gerontol. Ser. B 2002, 57, P101–P115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilardi, C.R.; Chieffi, S.; Iachini, T.; Iavarone, A. Neuropsychology of posteromedial parietal cortex and conversion factors from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: systematic search and state-of-the-art review. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 34, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dement. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, N.Y.V.; Bento-Torres, N.V.O.; Tomás, A.M.; da Costa, V.O.; Bento-Torres, J.; Picanço-Diniz, C.W. Unexpected cognitive similarities between older adults and young people: Scores variability and cognitive performances. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 117, 105206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.K.; Jo, M.; Kim, J.-H.; Suk, K. Microglia-Astrocyte Crosstalk: An Intimate Molecular Conversation. Neurosci. 2019, 25, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Chan, A.K.Y.; Wu, J.; Lee, T.M.C. Relationships between Inflammation and Age-Related Neurocognitive Changes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorfi, M.; Maaser-Hecker, A.; Tanzi, R.E. The neuroimmune axis of Alzheimer’s disease. Genome Med. 2023, 15, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, S. M. A., and P. A. Adlard. 2019. "Ageing and Cognition." Subcell Biochem 91: 107-122. [CrossRef]

- Jurga, A.M.; Paleczna, M.; Kuter, K.Z. Overview of General and Discriminating Markers of Differential Microglia Phenotypes. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, E.-B.; Kwon, I.-S.; Koo, J.-H.; Kim, E.-J.; Kim, C.-H.; Lee, J.; Yang, C.-H.; Lee, Y.-I.; Cho, I.-H.; Cho, J.-Y. Treadmill exercise represses neuronal cell death and inflammation during Aβ-induced ER stress by regulating unfolded protein response in aged presenilin 2 mutant mice. Apoptosis 2013, 18, 1332–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzman, R.; Brown, T.; Thal, L.J.; Fuld, P.A.; Aronson, M.; Butters, N.; Klauber, M.R.; Wiederholt, W.; Pay, M.; Renbing, X.; et al. Comparison of rate of annual change of mental status score in four independent studies of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 1988, 24, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempermann, G., H. G. Kuhn, and F. H. Gage. 1997. "More Hippocampal Neurons in Adult Mice Living in an Enriched Environment." Nature 386, no. 6624 (Apr 3): 493-5.

- Kinzer, A.; Suhr, J.A. Dementia worry and its relationship to dementia exposure, psychological factors, and subjective memory concerns. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2015, 23, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaips, C.L.; Jayaraj, G.G.; Hartl, F.U. Pathways of cellular proteostasis in aging and disease. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 217, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobilo, T.; Liu, Q.-R.; Gandhi, K.; Mughal, M.; Shaham, Y.; van Praag, H. Running is the neurogenic and neurotrophic stimulus in environmental enrichment. Learn. Mem. 2011, 18, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosyreva, A.M.; Sentyabreva, A.V.; Tsvetkov, I.S.; Makarova, O.V. Alzheimer’s Disease and Inflammaging. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraal, A.Z.; Massimo, L.; Fletcher, E.; Carrión, C.I.; Medina, L.D.; Mungas, D.; Gavett, B.E.; Farias, S.T. Functional reserve: The residual variance in instrumental activities of daily living not explained by brain structure, cognition, and demographics. Neuropsychology 2021, 35, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rani, A.; Tchigranova, O.; Lee, W.-H.; Foster, T.C. Influence of late-life exposure to environmental enrichment or exercise on hippocampal function and CA1 senescent physiology. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 828–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Srivastava, S.; Muhammad, T. Relationship between physical activity and cognitive functioning among older Indian adults. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalo, U.; Bogdanov, A.; Moss, G.W.; Pankratov, Y. Astroglia-Derived BDNF and MSK-1 Mediate Experience- and Diet-Dependent Synaptic Plasticity. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalo, U.; Pankratov, Y. Astrocytes as Perspective Targets of Exercise- and Caloric Restriction-Mimetics. Neurochem. Res. 2021, 46, 2746–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A LaPlume, A.; Anderson, N.D.; McKetton, L.; Levine, B.; Troyer, A.K. Corrigendum to: When I’m 64: Age-Related Variability in Over 40,000 Online Cognitive Test Takers. Journals Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 77, 130–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, V.; Ramer, L.; Tremblay, M. An aging, pathology burden, and glial senescence build-up hypothesis for late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J. 2023. "Mild Cognitive Impairment In relation To alzheimer’s Disease: An investigation Of principles, Classifcations,.

- Lee, J. Mild Cognitive Impairment in Relation to Alzheimer’s Disease: An Investigation of Principles, Classifications, Ethics, and Problems. Neuroethics 2023, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.-Y.; Yau, S.-Y. From Obesity to Hippocampal Neurodegeneration: Pathogenesis and Non-Pharmacological Interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leger, M., et al. 2012. "Environmental Enrichment Enhances Episodic-Like Memory in Association with a Modified Neuronal Activation Profile in Adult Mice." PLoS One 7, no. 10: e48043. [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, P., et al. 2023. "Molecular and Cognitive Signatures of Ageing Partially Restored through Synthetic Delivery of Il2 to the Brain." EMBO Mol Med 15, no. 5 (May 8): e16805. [CrossRef]

- Leng, F., et al. 2023. "Neuroinflammation Is Independently Associated with Brain Network Dysfunction in Alzheimer's Disease." Mol Psychiatry 28, no. 3 (Mar): 1303-1311. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ni, Y.-Q.; Xu, H.; Xiang, Q.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhan, J.-K.; He, J.-Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.-S. Roles and mechanisms of exosomal non-coding RNAs in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F., et al. 2021. "Neuroplastic Effect of Exercise through Astrocytes Activation and Cellular Crosstalk." Aging Dis 12, no. 7 (Oct): 1644-1657. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., et al. 2023. "Inflammation and Aging: Signaling Pathways and Intervention Therapies." Signal Transduct Target Ther 8, no. 1 (Jun 8): 239. [CrossRef]

- Lin, T. W., S. F. Tsai, and Y. M. Kuo. 2018. "Physical Exercise Enhances Neuroplasticity and Delays Alzheimer's Disease." Brain Plast 4, no. 1 (Dec 12): 95-110. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. T., et al. 2022. "Effects of Involuntary Treadmill Running in Combination with Swimming on Adult Neurogenesis in an Alzheimer's Mouse Model." Neurochem Int 155 (May): 105309. [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loch-Neckel, G., et al. 2022. "Challenges in the Development of Drug Delivery Systems Based on Small Extracellular Vesicles for Therapy of Brain Diseases." Front Pharmacol 13: 839790. [CrossRef]

- Loh, J. S., et al. 2024. "Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis and Its Therapeutic Applications in Neurodegenerative Diseases." Signal Transduct Target Ther 9, no. 1 (Feb 16): 37. [CrossRef]

- Lundquist, A. J., et al. 2019. "Exercise Induces Region-Specific Remodeling of Astrocyte Morphology and Reactive Astrocyte Gene Expression Patterns in Male Mice." J Neurosci Res 97, no. 9 (Sep): 1081-1094. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C., et al. 2023. "Hallmarks of Aging: An Expanding Universe." Cell 186, no. 2 (Jan 19): 243-278. [CrossRef]

- Lövdén, M., et al. 2020. "Education and Cognitive Functioning across the Life Span." Psychol Sci Public Interest 21, no. 1 (Aug): 6-41. [CrossRef]

- Marschallinger, J., et al. 2015. "Structural and Functional Rejuvenation of the Aged Brain by an Approved Anti-Asthmatic Drug." Nat Commun 6 (Oct 27): 8466. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P., and M. A. Blasco. 2018. "Heart-Breaking Telomeres." Circ Res 123, no. 7 (Sep 14): 787-802. [CrossRef]

- Maseda, A., et al. 2014. "Cognitive and Affective Assessment in Day Care Versus Institutionalized Elderly Patients: A 1-Year Longitudinal Study." Clin Interv Aging 9: 887-94. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, F.; Marioni, R.; Brayne, C. Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. Examining the influence of gender, education, social class and birth cohort on MMSE tracking over time: a population-based prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2012, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, G., et al. 2021. "Neuroprotective Effects of Physical Activity Via the Adaptation of Astrocytes." Cells 10, no. 6 (Jun 18). [CrossRef]

- Memel, M., et al. 2021. "Relationship between Objectively Measured Physical Activity on Neuropathology and Cognitive Outcomes in Older Adults: Resistance Versus Resilience?" Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 13, no. 1: e12245. [CrossRef]

- Methi, A., et al. 2024. "A Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of the Mouse Hippocampus after Voluntary Exercise." Mol Neurobiol 61, no. 8 (Aug): 5628-5645. [CrossRef]

- Michael, J., et al. 2020. "Microglia Depletion Diminishes Key Elements of the Leukotriene Pathway in the Brain of Alzheimer's Disease Mice." Acta Neuropathol Commun 8, no. 1 (Aug 8): 129. [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M. M., et al. 2021. "Comparison of Plasma Phosphorylated Tau Species with Amyloid and Tau Positron Emission Tomography, Neurodegeneration, Vascular Pathology, and Cognitive Outcomes." JAMA Neurol 78, no. 9 (Sep 01): 1108-1117. [CrossRef]

- Miller, K. N., et al. 2021. "Cytoplasmic Dna: Sources, Sensing, and Role in Aging and Disease." Cell 184, no. 22 (Oct 28): 5506-5526. [CrossRef]

- Monda, V., et al. 2017. "Exercise Modifies the Gut Microbiota with Positive Health Effects." Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017: 3831972. [CrossRef]

- Moore, K., et al. 2018. "Diet, Nutrition and the Ageing Brain: Current Evidence and New Directions." Proc Nutr Soc 77, no. 2 (May): 152-163. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Agostino, D., et al. 2020. "The Impact of Physical Activity on Healthy Ageing Trajectories: Evidence from Eight Cohort Studies." Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 17, no. 1 (Jul 16): 92. [CrossRef]

- Morse, C. K. 1993. "Does Variability Increase with Age? An Archival Study of Cognitive Measures." Psychol Aging 8, no. 2 (Jun): 156-64. [CrossRef]

- Mrowetz, H., et al. 2023. "Leukotriene Signaling as Molecular Correlate for Cognitive Heterogeneity in Aging: An Exploratory Study." Front Aging Neurosci 15: 1140708. [CrossRef]

- Mungas, D., et al. 2005. "Longitudinal Volumetric Mri Change and Rate of Cognitive Decline." Neurology 65, no. 4 (Aug 23): 565-71. [CrossRef]

- Musgrove, M. R. B., M. Mikhaylova, and T. W. Bredy. 2024. "Fundamental Neurochemistry Review: At the Intersection between the Brain and the Immune System: Non-Coding Rnas Spanning Learning, Memory and Adaptive Immunity." J Neurochem 168, no. 6 (Jun): 961-976. [CrossRef]

- Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Solomon, A.; Levälahti, E.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Antikainen, R.; Bäckman, L.; Hänninen, T.; Jula, A.; Laatikainen, T.; et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2255–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogrodnik, M., et al. 2021. "Whole-Body Senescent Cell Clearance Alleviates Age-Related Brain Inflammation and Cognitive Impairment in Mice." Aging Cell 20, no. 2 (Feb): e13296. [CrossRef]

- Okuno, H., K. Minatohara, and H. Bito. 2018. "Inverse Synaptic Tagging: An Inactive Synapse-Specific Mechanism to Capture Activity-Induced Arc/Arg3.1 and to Locally Regulate Spatial Distribution of Synaptic Weights." Semin Cell Dev Biol 77 (May): 43-50. [CrossRef]

- Opdebeeck, C., A. Martyr, and L. Clare. 2016. "Cognitive Reserve and Cognitive Function in Healthy Older People: A Meta-Analysis." Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 23, no. 1: 40-60. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A. L., and S. S. Ousman. 2018. "Astrocytes and Aging." Front Aging Neurosci 10: 337. [CrossRef]

- Pan, J., et al. 2020. "Transcriptomic Profiling of Microglia and Astrocytes Throughout Aging." J Neuroinflammation 17, no. 1 (Apr 1): 97. [CrossRef]

- Paolicelli, R. C., et al. 2022. "Microglia States and Nomenclature: A Field at Its Crossroads." Neuron 110, no. 21 (Nov 2): 3458-3483. [CrossRef]

- Paolillo, E. W., et al. 2023. "Multimodal Lifestyle Engagement Patterns Support Cognitive Stability Beyond Neuropathological Burden." Alzheimers Res Ther 15, no. 1 (Dec 18): 221. [CrossRef]

- Park, J. H., et al. 2020. "Sedentary Lifestyle: Overview of Updated Evidence of Potential Health Risks." Korean J Fam Med 41, no. 6 (Nov): 365-373. [CrossRef]

- Park, J. I., and Initiative Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging. 2024. "Prevalence of Mild Behavioural Impairment and Its Association with Cognitive and Functional Impairment in Normal Cognition, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Mild Alzheimer's Dementia." Psychogeriatrics 24, no. 3 (May): 555-564. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, R., et al. 2018. "Sedentary Behaviour and Risk of All-Cause, Cardiovascular and Cancer Mortality, and Incident Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Dose Response Meta-Analysis." Eur J Epidemiol 33, no. 9 (Sep): 811-829. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R. C., et al. 2014. "Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Concept in Evolution." J Intern Med 275, no. 3 (Mar): 214-28. [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Hernandez, P., et al. 2023. "Modulation of Micrornas through Lifestyle Changes in Alzheimer's Disease." Nutrients 15, no. 17 (Aug 23). [CrossRef]

- Pitrez, P. R., et al. 2024. "Cellular Reprogramming as a Tool to Model Human Aging in a Dish." Nat Commun 15, no. 1 (Feb 28): 1816. [CrossRef]

- Popov, A., et al. 2021. "Astrocyte Dystrophy in Ageing Brain Parallels Impaired Synaptic Plasticity." Aging Cell 20, no. 3 (Mar): e13334. [CrossRef]

- Puri, S., M. Shaheen, and B. Grover. 2023. "Nutrition and Cognitive Health: A Life Course Approach." Front Public Health 11: 1023907. [CrossRef]

- Quigley, A., M. MacKay-Lyons, and G. Eskes. 2020. "Effects of Exercise on Cognitive Performance in Older Adults: A Narrative Review of the Evidence, Possible Biological Mechanisms, and Recommendations for Exercise Prescription." J Aging Res 2020: 1407896. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. S., et al. 2024. "Dynamics of Cognitive Variability with Age and Its Genetic Underpinning in Nihr Bioresource Genes and Cognition Cohort Participants." Nat Med 30, no. 6 (Jun): 1739-1748. [CrossRef]

- Ribaric, S. 2022. "Physical Exercise, a Potential Non-Pharmacological Intervention for Attenuating Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer's Disease Patients." Int J Mol Sci 23, no. 6 (Mar 17). [CrossRef]

- Risacher, S. L., and A. J. Saykin. 2019. "Neuroimaging in Aging and Neurologic Diseases." Handb Clin Neurol 167: 191-227. [CrossRef]

- Rohr, S., et al. 2022. "Social Determinants and Lifestyle Factors for Brain Health: Implications for Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia." Sci Rep 12, no. 1 (Jul 28): 12965. [CrossRef]

- Salas, I. H., J. Burgado, and N. J. Allen. 2020. "Glia: Victims or Villains of the Aging Brain?" Neurobiol Dis 143 (Sep): 105008. [CrossRef]

- Sampedro-Piquero, P., et al. 2014. "Astrocytic Plasticity as a Possible Mediator of the Cognitive Improvements after Environmental Enrichment in Aged Rats." Neurobiol Learn Mem 114 (Oct): 16-25. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A., and A. Nazir. 2022. "Carrying Excess Baggage Can Slowdown Life: Protein Clearance Machineries That Go Awry During Aging and the Relevance of Maintaining Them." Mol Neurobiol 59, no. 2 (Feb): 821-840. [CrossRef]

- Schmauck-Medina, T., et al. 2022. "New Hallmarks of Ageing: A 2022 Copenhagen Ageing Meeting Summary." Aging (Albany NY) 14, no. 16 (Aug 29): 6829-6839. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, L. O., and J. M. Gaspar. 2023. "Obesity-Induced Brain Neuroinflammatory and Mitochondrial Changes." Metabolites 13, no. 1 (Jan 5). [CrossRef]

- Seale, K., et al. 2022. "Making Sense of the Ageing Methylome." Nat Rev Genet 23, no. 10 (Oct): 585-605. [CrossRef]

- Seblova, D., R. Berggren, and M. Lövdén. 2020. "Education and Age-Related Decline in Cognitive Performance: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Cohort Studies." Ageing Res Rev 58 (Mar): 101005. [CrossRef]

- Seligowski, A. V., et al. 2012. "Correlates of Life Satisfaction among Aging Veterans." Appl Psychol Health Well Being 4, no. 3 (Nov): 261-75. [CrossRef]

- Shafqat, A., et al. 2023. "Cellular Senescence in Brain Aging and Cognitive Decline." Front Aging Neurosci 15: 1281581. [CrossRef]

- Shivarama Shetty, M., and S. Sajikumar. 2017. "'Tagging' Along Memories in Aging: Synaptic Tagging and Capture Mechanisms in the Aged Hippocampus." Ageing Res Rev 35 (May): 22-35. [CrossRef]

- Sikora, E., et al. 2021. "Cellular Senescence in Brain Aging." Front Aging Neurosci 13: 646924. [CrossRef]

- Sindi, S., et al. 2017. "Baseline Telomere Length and Effects of a Multidomain Lifestyle Intervention on Cognition: The Finger Randomized Controlled Trial." J Alzheimers Dis 59, no. 4: 1459-1470. [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. J., et al. 2010. "Aerobic Exercise and Neurocognitive Performance: A Meta-Analytic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials." Psychosom Med 72, no. 3 (Apr): 239-52. [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F., et al. 2011. "Physical Activity and Risk of Cognitive Decline: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies." J Intern Med 269, no. 1 (Jan): 107-17. [CrossRef]

- Sogaard, I., and R. Ni. 2018. "Mediating Age-Related Cognitive Decline through Lifestyle Activities: A Brief Review of the Effects of Physical Exercise and Sports-Playing on Older Adult Cognition." Acta Psychopathol (Wilmington) 4, no. 5. [CrossRef]

- Song, X., et al. 2021. "Dna Repair Inhibition Leads to Active Export of Repetitive Sequences to the Cytoplasm Triggering an Inflammatory Response." J Neurosci 41, no. 45 (Nov 10): 9286-9307. [CrossRef]

- Soraci, L., et al. 2024. "Neuroinflammaging: A Tight Line between Normal Aging and Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disorders." Aging Dis 15, no. 4 (Aug 01): 1726-1747. [CrossRef]

- Speakman, J. R. 2020. "An Evolutionary Perspective on Sedentary Behavior." Bioessays 42, no. 1 (Jan): e1900156. [CrossRef]

- Speisman, R. B., et al. 2013. "Daily Exercise Improves Memory, Stimulates Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Modulates Immune and Neuroimmune Cytokines in Aging Rats." Brain Behav Immun 28 (Feb): 25-43. [CrossRef]

- Environmental Enrichment Restores Neurogenesis and Rapid Acquisition in Aged Rats." Neurobiol Aging (Jul).

- Stern, Y. 2002. "What Is Cognitive Reserve? Theory and Research Application of the Reserve Concept." J Int Neuropsychol Soc 8, no. 3 (Mar): 448-60.

- Cognitive Reserve." Neuropsychologia 47, no. 10 (Aug): 2015-28. [CrossRef]

- Cognitive Reserve in Ageing and Alzheimer's Disease." Lancet Neurol 11, no. 11 (Nov): 1006-12. [CrossRef]

- How Can Cognitive Reserve Promote Cognitive and Neurobehavioral Health?" Arch Clin Neuropsychol 36, no. 7 (Oct 13): 1291-1295. [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y.; Arenaza-Urquiljo, E.M.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Belleville, S.; Cantillon, M.; Chetelat, G.; Ewers, M.; Franzmeier, N.; Kempermann, G.; Kremen, W.S.; et al. Whitepaper: Defining and investigating cognitive reserve, brain reserve, and brain maintenance. Alzheimer's Dement. 2020, 16, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, Y., and D. Barulli. 2019. "Cognitive Reserve." Handb Clin Neurol 167: 181-190. [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y., et al. 1994. "Influence of Education and Occupation on the Incidence of Alzheimer's Disease." JAMA 271, no. 13 (Apr 06): 1004-10.

- Sun, L. N., J. S. Qi, and R. Gao. 2018. "Physical Exercise Reserved Amyloid-Beta Induced Brain Dysfunctions by Regulating Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Inflammatory Response Via Mapk Signaling." Brain Res 1697 (Oct 15): 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H., et al. 2014. "Role of Neuropsin in Parvalbumin Immunoreactivity Changes in Hippocampal Basket Terminals of Mice Reared in Various Environments." Front Cell Neurosci 8: 420. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Izquierdo, M., and R. Fernández-Ballesteros. 2021. "Cognition in Healthy Aging." Int J Environ Res Public Health 18, no. 3 (Jan 22). [CrossRef]

- Teng, L., et al. 2020. "Predicting Mci Progression with Fdg-Pet and Cognitive Scores: A Longitudinal Study." BMC Neurol 20, no. 1 (Apr 21): 148. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S. F., et al. 2016. "Exercise Counteracts Aging-Related Memory Impairment: A Potential Role for the Astrocytic Metabolic Shuttle." Front Aging Neurosci 8: 57. [CrossRef]

- Turrini, S., et al. 2023. "The Multifactorial Nature of Healthy Brain Ageing: Brain Changes, Functional Decline and Protective Factors." Ageing Res Rev 88 (Apr 27): 101939. [CrossRef]

- Tyndall, A. V., et al. 2013. "The Brain-in-Motion Study: Effect of a 6-Month Aerobic Exercise Intervention on Cerebrovascular Regulation and Cognitive Function in Older Adults." BMC Geriatr 13 (Feb 28): 21. [CrossRef]

- Vallès, A., et al. 2014. "Molecular Correlates of Cortical Network Modulation by Long-Term Sensory Experience in the Adult Rat Barrel Cortex." Learn Mem 21, no. 6 (Jun): 305-10. [CrossRef]

- van Praag, H., et al. 2005. "Exercise Enhances Learning and Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Aged Mice." J Neurosci 25, no. 38 (Sep 21): 8680-5.

- Vaynman, S., and F. Gomez-Pinilla. 2006. "Revenge of The "Sit": How Lifestyle Impacts Neuronal and Cognitive Health through Molecular Systems That Interface Energy Metabolism with Neuronal Plasticity." J Neurosci Res 84, no. 4 (Sep): 699-715. [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, Alexei, and Robert Zorec. 2024. "Neuroglia in Cognitive Reserve." Molecular Psychiatry (2024/07/02). [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, J., et al. 2022. "Evidence That Ageing Yields Improvements as Well as Declines across Attention and Executive Functions." Nat Hum Behav 6, no. 1 (Jan): 97-110. [CrossRef]

- Viana, L.C., et al. 2013. "Litter Size, Age-Related Memory Impairments, and Microglial Changes in Rat Dentate Gyrus: Stereological Analysis and Three Dimensional Morphometry." Neuroscience (2013). [CrossRef]

- Volkers, K. M., and E. J. Scherder. 2011. "Impoverished Environment, Cognition, Aging and Dementia." Rev Neurosci 22, no. 3: 259-66. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, A. D., et al. 2023. "Mouse Microglia Express Unique Mirna-Mrna Networks to Facilitate Age-Specific Functions in the Developing Central Nervous System." Commun Biol 6, no. 1 (May 22): 555. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Y., et al. 2023. "Long-Term Voluntary Exercise Inhibited Age/Rage and Microglial Activation and Reduced the Loss of Dendritic Spines in the Hippocampi of App/Ps1 Transgenic Mice." Exp Neurol 363 (May): 114371. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Q. Yuan, and L. Xie. 2018. "Histone Modifications in Aging: The Underlying Mechanisms and Implications." Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 13, no. 2: 125-135. [CrossRef]

- Wegierska, A. E., et al. 2022. "The Connection between Physical Exercise and Gut Microbiota: Implications for Competitive Sports Athletes." Sports Med 52, no. 10 (Oct): 2355-2369. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J. A., et al. 2023. "Physical Exercise Modulates the Microglial Complement Pathway in Mice to Relieve Cortical Circuitry Deficits Induced by Mutant Human Tdp-43." Cell Rep 42, no. 3 (Mar 28): 112240. [CrossRef]

- Weiner, M. W., et al. 2015. "2014 Update of the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: A Review of Papers Published since Its Inception." Alzheimers Dement 11, no. 6 (Jun): e1-120. [CrossRef]

- Werner, P., H. AboJabel, and M. Maxfield. 2021. "Conceptualization, Measurement and Correlates of Dementia Worry: A Scoping Review." Arch Gerontol Geriatr 92: 104246. [CrossRef]

- Wingo, A. P., et al. 2022. "Brain Micrornas Are Associated with Variation in Cognitive Trajectory in Advanced Age." Transl Psychiatry 12, no. 1 (Feb 1): 47. [CrossRef]

- Winocur, G. 1998. "Environmental Influences on Cognitive Decline in Aged Rats." Neurobiol Aging 19, no. 6 (Nov-Dec): 589-97.

- Wu, Z., et al. 2024. "Emerging Epigenetic Insights into Aging Mechanisms and Interventions." Trends Pharmacol Sci 45, no. 2 (Feb): 157-172. [CrossRef]

- Xue, B., et al. 2022. "Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: A Connecting Link between Nutrition, Lifestyle, and Alzheimer's Disease." Front Neurosci 16: 925991. [CrossRef]

- Yan, M., et al. 2021. "5-Lipoxygenase as an Emerging Target against Age-Related Brain Disorders." Ageing Res Rev 69 (Aug): 101359. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., et al. 2024. "The Role of Glial Cells in Synaptic Dysfunction: Insights into Alzheimer's Disease Mechanisms." Aging Dis 15, no. 2 (Apr 1): 459-479. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z., et al. 2012. "An Enriched Environment Improves Cognitive Performance in Mice from the Senescence-Accelerated Prone Mouse 8 Strain: Role of Upregulated Neurotrophic Factor Expression in the Hippocampus." Neural Regen Res 7, no. 23 (Aug): 1797-804. [CrossRef]

- Zalik, E., and B. Zalar. 2013. "Differences in Mood between Elderly Persons Living in Different Residential Environments in Slovenia." Psychiatr Danub 25, no. 1 (Mar): 40-8.

- Zhang, D., et al. 2023. "Tead4 Antagonizes Cellular Senescence by Remodeling Chromatin Accessibility at Enhancer Regions." Cell Mol Life Sci 80, no. 11 (Oct 19): 330. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., S. Wang, and B. Liu. 2023. "New Insights into the Genetics and Epigenetics of Aging Plasticity." Genes (Basel) 14, no. 2 (Jan 27). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., et al. 2025. "Gut Microbiota-Astrocyte Axis: New Insights into Age-Related Cognitive Decline." Neural Regen Res 20, no. 4 (Apr 1): 990-1008. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., et al. 2024. "Cellular Senescence, Dna Damage, and Neuroinflammation in the Aging Brain." Trends Neurosci 47, no. 6 (Jun): 461-474. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. S., et al. 2024. "Educational Attainment and Later-Life Cognitive Function in High- and Middle-Income Countries: Evidence from the Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol." J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 79, no. 5 (May 01). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., et al. 2021. "Extracellular Vesicle-Derived Mirna as a Novel Regulatory System for Bi-Directional Communication in Gut-Brain-Microbiota Axis." J Transl Med 19, no. 1 (May 11): 202. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R., et al. 2022. "Microbiota-Microglia Connections in Age-Related Cognition Decline." Aging Cell 21, no. 5 (May): e13599. [CrossRef]

- Zia, A., et al. 2021. "Molecular and Cellular Pathways Contributing to Brain Aging." Behav Brain Funct 17, no. 1 (Jun 12): 6. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).