Submitted:

16 August 2024

Posted:

16 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Motivation

- exploit the logic substrate which RDF relies on, to compute the most specific RDF graph which is common to all resources in the cluster, known as Least Common Subsumer (LCS) [9]; this phase makes use of blank nodes in RDF, which are existential variables that can abstract — like placeholders, but with a logical semantics — the single values the resources differ on; however, although the LCS is logically complete, it is full of irrelevant details [10];

- compute a Common Subsumer (CS), an RDF structure which is a generalization of the LCS — so, logically, a CS is not the most specific description of the cluster — but still enough specific to capture the relevant features common to all resources;

- use such a structure to generate a phrase in constrained, but plain English, with the original idea of using English pronouns (that, which) to verbalize blank nodes in relative sentences.

- we propose an optimized algorithm for the computation of the CS of a cluster, scaling up to cluster dimensions not attained before;

- we validate this computation through an extensive experimentation with two, very different, real datasets;

- we collect and analyze data about experiments and discuss the computational properties of the implementation: convergence, expected runtime, and possible heuristics.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Background on RDF Syntax and Simple Entailment

| ex:a ex:r _:x . | and | _:x ex:q ex:b . |

| ex:a ex:p ex:b . | and | ex:p ex:q ex:d . |

2.2. Background on Common Subsumers in

- P1:

- for all and

- P2:

- any other r-graph with Property (P1) is logically equivalent to 〈x, Tx〉.

- Piroxicam: http://bio2rdf.org/drugbank:DB00554

- Tolterodine: http://bio2rdf.org/drugbank:DB01036

- ns1:

-

DB00554 ns2:affected-organism ns2:Humans-and-other-mammals;ns2:category ns2:Anti-Inflammatory-Agents,-Non-Steroidal;ns2:enzyme ns1:BE0002793.

- ns2:

- Humans-and-other-mammals rdf:type ns2:Affected-organism.

- ns2:

- Anti-Inflammatory-Agents,-Non-Steroidal rdf:type ns2:Category.

- ns1:

-

BE0002793 rdf:type ns2:Enzyme;ns2:cellular-location "Endoplasmic reticulum".

- ns1:

-

DB01036> ns2:affected-organism ns2:Humans-and-other-mammals;ns2:category ns2:Muscarinic-Antagonists.ns2:enzyme ns1:BE0002793.

- ns2:

- Humans-and-other-mammals rdf:type ns2:Affected-organism.

- ns2:

- Muscarinic-Antagonists rdf:type ns2:Category.

- ns1:

-

BE0002793 rdf:type ns2:Enzyme;ns2:cellular-location "Endoplasmic reticulum".

- _:x

-

ns2:affected-organism ns2:Humans-and-other-mammals;ns1:category _:y;ns2:enzyme ns1:BE0002793.

- ns2:

- Humans-and-other-mammals rdf:type ns2:Affected-organism.

- _:y

- rdf:type ns2:Category.

- ns1:

-

BE0002793 rdf:type ns2:Enzyme;ns2:cellular-location "Endoplasmic reticulum".

- CSP1:

- idempotent: ,

- CSP2:

- commutative: and

- CSP3:

- associative:

3. Computation Methodology and Analysis

- we present an algorithm computing the CS of two resources, which builds on a previously published one, but with a crucial optimization that reduces the size of the resulting CS — still an RDF graph, with blank nodes, but with much less triples than the output of the original algorithm

- exploiting associativity, we iterate the above algorithm computing the CS of a “running” CS (starting with a pair and the next resource , as the expression suggests.

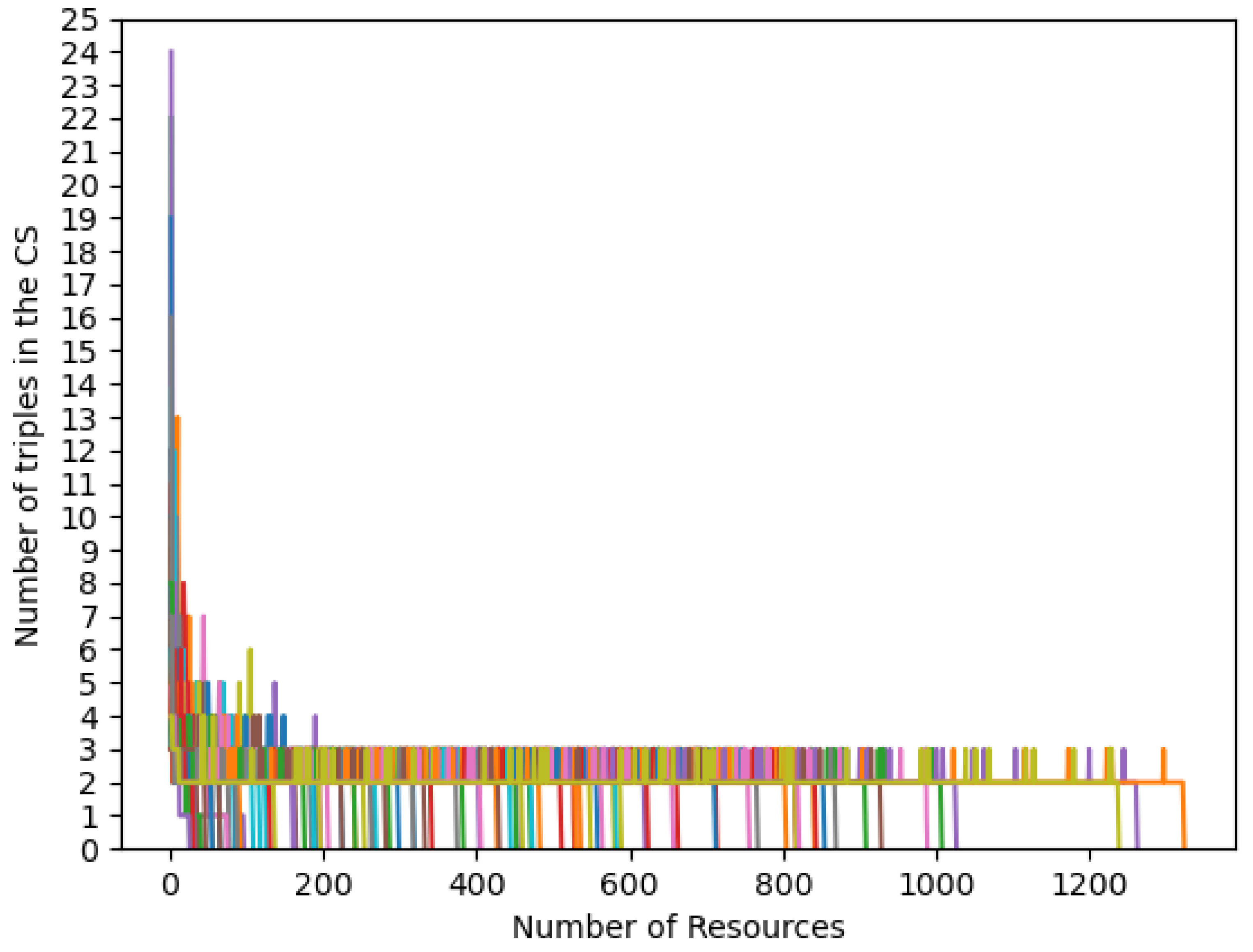

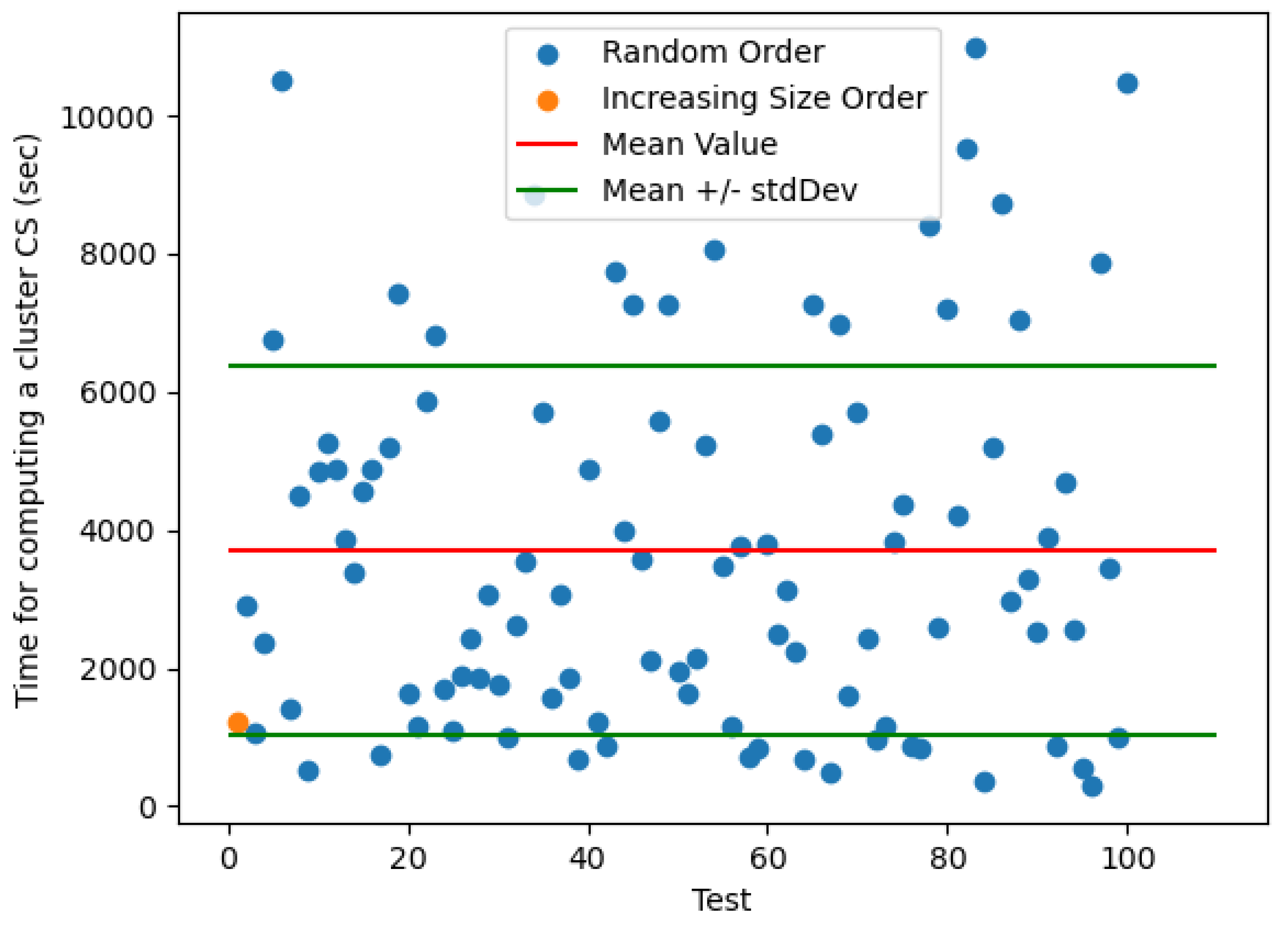

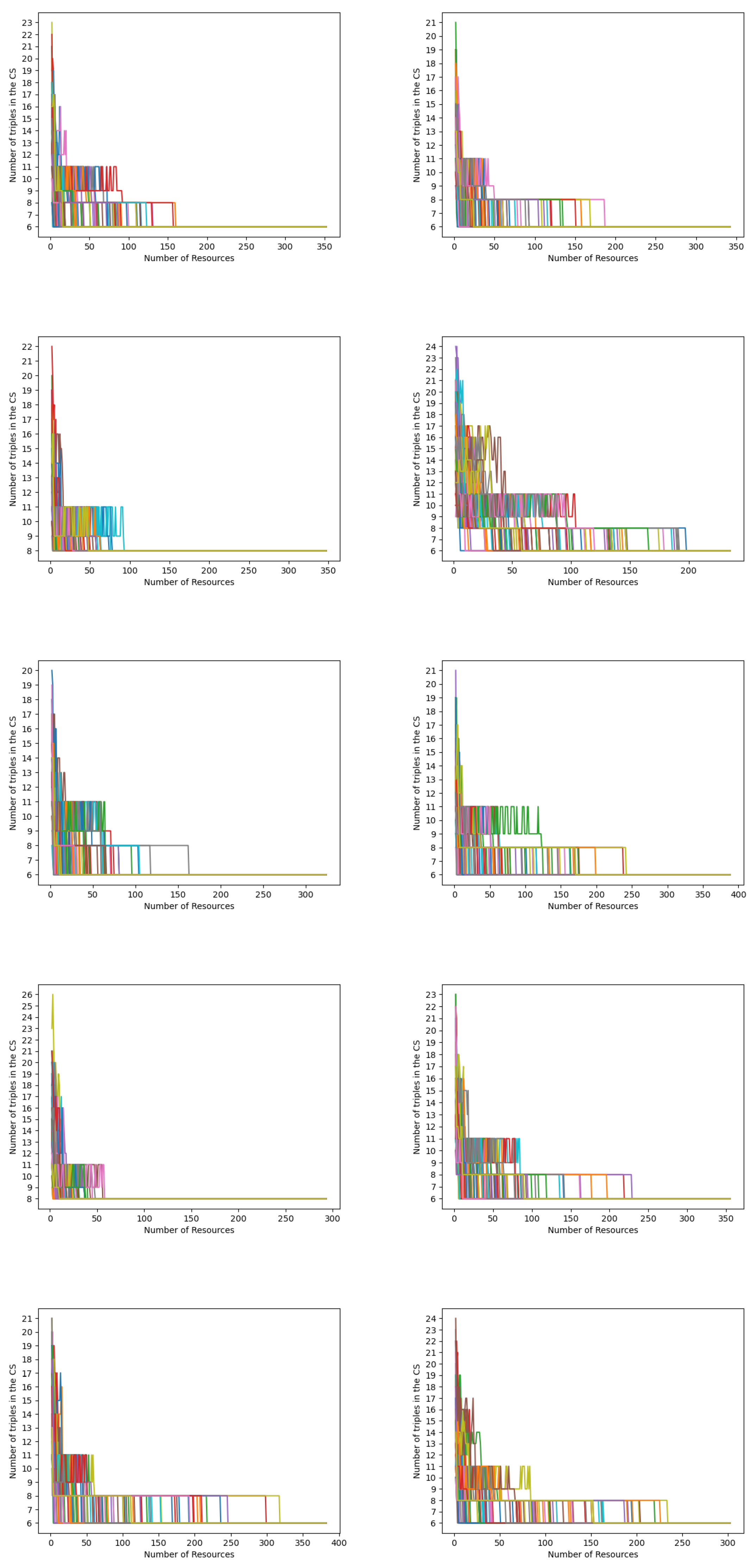

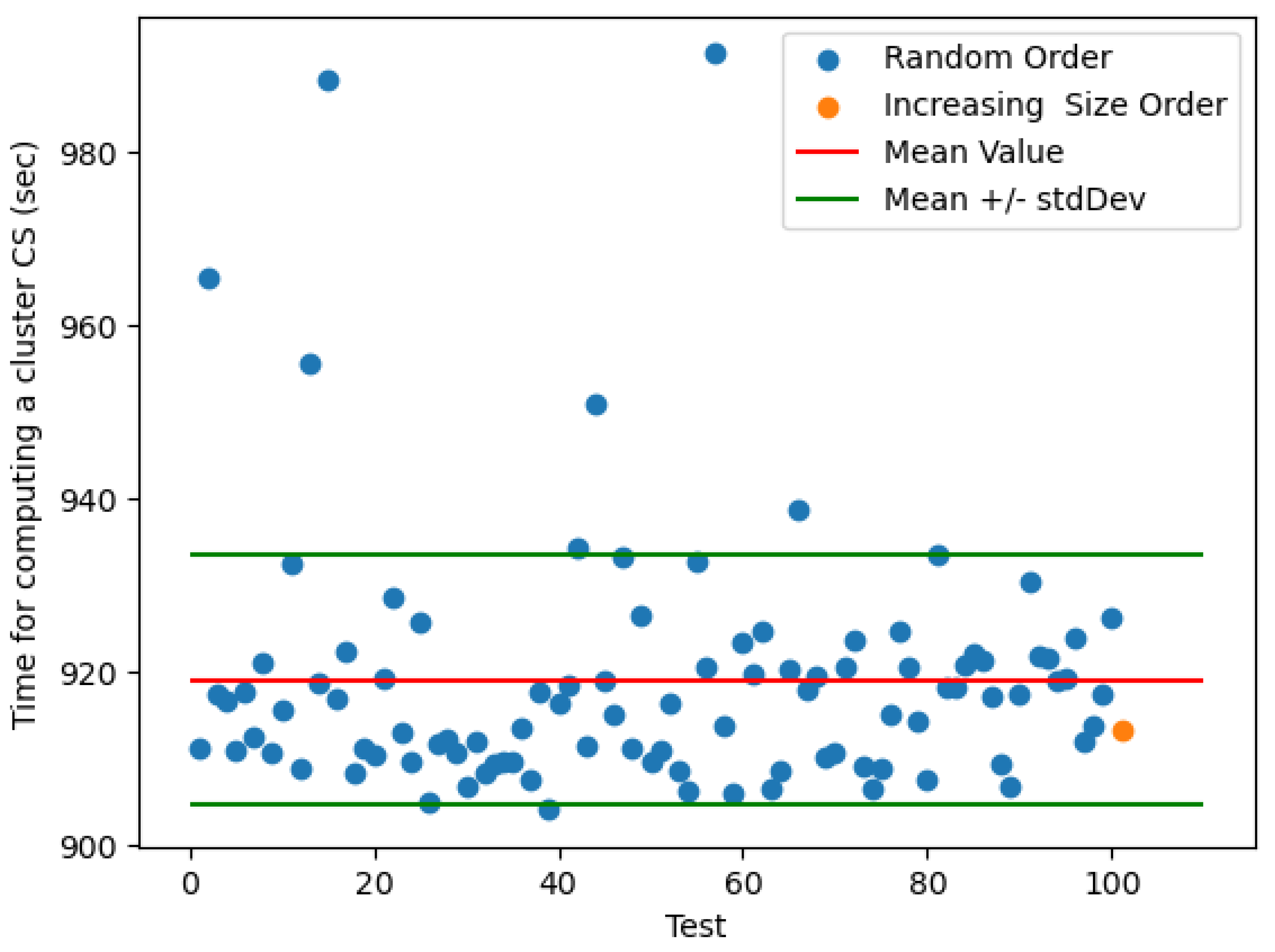

- since the time (and the size) for computing a (equivalent form of) CS of a complete cluster may vary depending on the ordering in which are given, in order to estimate the expected size of a CS of an entire cluster, and the time needed to compute it, we set up a Monte Carlo method, which probes only a random fraction of all the possible orderings, one of which could be used to incrementally compute the CS. We consider the increasing-size heuristic (see Section 3.3 below) as a special trial, and compare its size and time with the other trials

- RQ1:

- does the computation of the CS always converges to one size, when changing the order of resources incrementally added to the CS?

- RQ2:

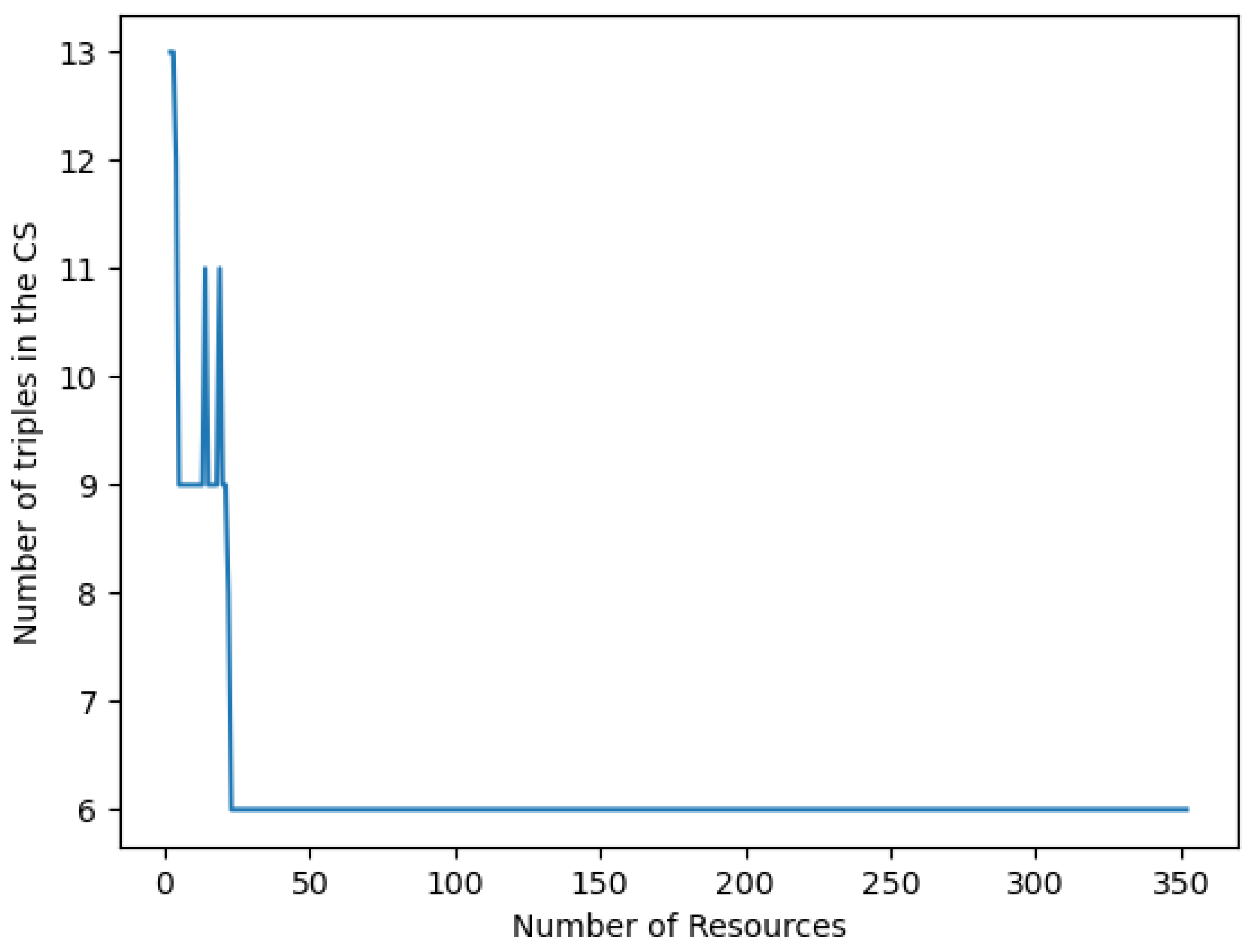

- how quickly converges (depending on the number of resources added to the CS) the incremental computation of a CS of a given cluster?

- RQ3:

- how much the different choices for the next resource to include influence the convergence, and are there simple heuristics that can be used to choose the initial pair, and the next resource?

3.1. An Improved Algorithm for the CS of Two Resources (Algorithm 1)

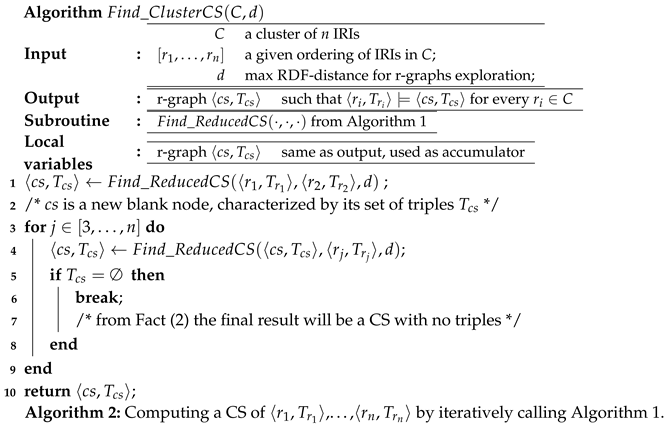

3.2. Computing the CS of a Cluster of Resources (Algorithm 2)

3.3. Expected Size of the Final CS, and Overall Runtime of Algorithm 2

4. Results

- the sequence of Common Subsumers progressively computed

- the sequence of sizes of the CS progressively computed

- the overall runtime of Algorithm 2 in that trial

4.1. Logical Convergence

4.2. Dependency of the Rate of Convergence on the Order of Added Resources

4.3. Analysis of Computation Time

4.4. Final Answers to Research Questions

- RQ1:

- does the computation of the CS always converges, when changing sequence of resources incrementally added to the CS? — Yes, independently of the sequence in which resources are added to the CS, the CS converges to the same information, represented as logically equivalent, possibly syntactically different, RDF graphs

- RQ2:

- How quickly converges (depending on the number of resources added to the CS) the incremental computation of a CS of a given cluster? — the rate of convergence to a final CS may vary a lot; the experiments reveal that the size of the final CS generally decreases, but not monotonically.

- RQ3:

- how much the different choices for the next resource to include influence the convergence, and are there simple heuristics that can be used to choose the initial pair, and the next resource? — it appears that the heuristic of choosing the resource with the minimum number of triples as the next one does not pay off in real datasets. For two real datasets, we proved that the patterns of the cases that were theoretically proved to be the exponential worst ones, do not show up.

5. Final Discussion

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RDF | Resource Description Framework |

| LCS | Least Common Subsumer |

| CS | Common Subsumer |

Appendix A

References

- Zhou, L.; Du, G.; Lü, K.; Wang, L.; Du, J. A Survey and an Empirical Evaluation of Multi-View Clustering Approaches. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Chen, Y.; Shi, X. Knowledge Graph Embedding Based on Multi-View Clustering Framework. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2021, 33, 585–596. [CrossRef]

- Bamatraf, S.A.; BinThalab, R.A. Clustering RDF data using K-medoids. 2019 First International Conference of Intelligent Computing and Engineering (ICOICE), 2019, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Aluç, G.; Özsu, M.T.; Daudjee, K. Building self-clustering RDF databases using Tunable-LSH. VLDB J. 2019, 28, 173–195. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Gao, H.; Zou, Z. WISE: Workload-Aware Partitioning for RDF Systems. Big Data Research 2020, 22. [CrossRef]

- Bandyapadhyay, S.; Fomin, F.V.; Golovach, P.A.; Lochet, W.; Purohit, N.; Simonov, K. How to find a good explanation for clustering? Artif. Intell. 2023, 322.

- Miller, T. Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences. Artificial Intelligence 2019, 267, 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Colucci, S.; Donini, F.M.; Iurilli, N.; Sciascio, E.D. A Business Intelligence Tool for Explaining Similarity. Model-Driven Organizational and Business Agility - Second International Workshop, MOBA 2022, Leuven, Belgium, June 6-7, 2022, Revised Selected Papers; Babkin, E.; Barjis, J.; Malyzhenkov, P.; Merunka, V., Eds. Springer, 2022, Vol. 457, Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, pp. 50–64. [CrossRef]

- Colucci, S.; Donini, F.; Giannini, S.; Di Sciascio, E. Defining and computing Least Common Subsumers in RDF. Web Semantics: Science, Services and Agents on the World Wide Web 2016, 39, 62 – 80.

- Colucci, S.; Donini, F.M.; Di Sciascio, E. On the Relevance of Explanation for RDF Resources Similarity. Model-Driven Organizational and Business Agility - Third International Workshop, MOBA 2023. Springer, 2023, Vol. 488, LNBIP, pp. 96–107.

- Bae, J.; Helldin, T.; Riveiro, M.; Nowaczyk, S.; Bouguelia, M.R.; Falkman, G. Interactive clustering: A comprehensive review. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2020, 53, 1–39.

- Colucci, S.; Donini, F.M.; Di Sciascio, E. A review of reasoning characteristics of RDF-based Semantic Web systems. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2024, 14.

- Cyganiak, R.; Wood, D.; Lanthaler, M. RDF 1.1 Concepts and Abstract Syntax, W3C Recommendation, 2014.

- Hartig, O.; Champin, P.A.; Kellogg, G.; Seaborne, A. RDF 1.2 Concepts and Abstract Syntax, W3C Working Draft, 2024.

- Patel-Schneider, P.; Arndt, D.; Haudebourg, T. RDF 1.2 Semantics, W3C Recommendation, 2023.

- Colucci, S.; Donini, F.M.; Di Sciascio, E. Common Subsumbers in RDF. AI*IA-2013. Springer, 2013, Vol. 8249, LNCS, pp. 348–359.

- Amendola, G.; Manna, M.; Ricioppo, A. A logic-based framework for characterizing nexus of similarity within knowledge bases. Information Sciences 2024, 664. [CrossRef]

- Colucci, S.; Donini, F.M.; Sciascio, E.D. Logical comparison over RDF resources in bio-informatics. J. Biomed. Informatics 2017, 76, 87–101. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.W.; Borgida, A.; Hirsh, H. Computing Least Common Subsumers in Description Logics. Proceedings of the 10th National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Jose, CA, USA, July 12-16, 1992; Swartout, W.R., Ed. AAAI Press / The MIT Press, 1992, pp. 754–760.

- Baader, F.; Küsters, R.; Molitor, R. Computing least common subsumers in description logics with existential restrictions. IJCAI, 1999, Vol. 99, pp. 96–101.

- Pichler, R.; Polleres, A.; Skritek, S.; Woltran, S. Complexity of redundancy detection on RDF graphs in the presence of rules, constraints, and queries. Semantic Web 2013, 4, 351–393.

- Rubinstein, R.Y. Simulation and the Monte Carlo Method, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: USA, 1981.

- Jain, A.K.; Dubes, R.C. Algorithms for Clustering Data; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1988.

- Soylu, A.; Corcho, O.; Elvesater, B.; Badenes-Olmedo, C.; Blount, T.; Yedro Martinez, F.; Kovacic, M.; Posinkovic, M.; Makgill, I.; Taggart, C.; Simperl, E.; Lech, T.C.; Roman, D. TheyBuyForYou platform and knowledge graph: Expanding horizons in public procurement with open linked data. Semantic Web 2022, 13.

- Soylu, A.; Elvesæter, B.; Turk, P.; Roman, D.; Corcho, O.; Simperl, E.; Konstantinidis, G.; Lech, T.C. Towards an Ontology for Public Procurement Based on the Open Contracting Data Standard. Proc. of 18th IFIP WG 6.11 Conference on e-Business, e-Services, and e-Society, I3E 2019. Springer-Verlag, 2019.

- Ristoski, P.; Rosati, J.; Noia, T.D.; Leone, R.D.; Paulheim, H. RDF2Vec: RDF graph embeddings and their applications. Semantic Web 2019, 10, 721–752. [CrossRef]

- Marutho, D.; Hendra Handaka, S.; Wijaya, E.; Muljono. The Determination of Cluster Number at k-Mean Using Elbow Method and Purity Evaluation on Headline News. 2018 International Seminar on Application for Technology of Information and Communication, 2018, pp. 533–538. [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 1987, 20, 53–65. [CrossRef]

- Schubert, E. Stop using the elbow criterion for k-means and how to choose the number of clusters instead. SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2023, 25, 36-42. [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Helldin, T.; Riveiro, M.; Nowaczyk, S.; Bouguelia, M.R.; Falkman, G. Interactive Clustering: A Comprehensive Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53.

- Wishart, D.S.; Knox, C.; Guo, A.C.; Cheng, D.; Shrivastava, S.; Tzur, D.; Gautam, B.; Hassanali, M. DrugBank: a knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions and drug targets. Nucleic acids research 2008, 36, D901–D906.

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Note that this interpretation requires that when RDF files are merged, name conflicts in blank nodes must be standardized apart. This aspect is carefully discussed in the W3C recommendations. |

| 6 | |

| 7 | A lean graph G is an RDF-graph that is ⊆-minimal among all RDF-graphs logically equivalent to G [15]. |

| 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).