Submitted:

15 August 2024

Posted:

16 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Review of Previous Research and Presentation of Hypotheses

2.1. Hofstede’s Six Cultural Scales

2.2. Hypothesis Presentation Regarding the Relationship between Cultural Measures and Ageism

3.2. Measures

3.3. Control Variables

3.4. Analysis Method

4. Analysis and Findings

5. Discussion

6. Limitation

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Revised and expanded, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Haerpfer, C.; Moreno, A.; Welzel, C.; Kizilova, K.; Diez-Medrano, J.; Lagos, M.; Norris, P.; Ponarin, E.; Puranen, B.; et al. (Eds.) World Values Survey: Round Six - Country-Pooled Datafile Version, Madrid: JD Systems Institute, 2014. Available online: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Butler, R.N. Age-ism: Another form of bigotry. Gerontologist 1969, 9, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löckenhoff, C.E.; De Fruyt, F.; Terracciano, A.; McCrae, R.R.; De Bolle, M.; Costa, P.T.; Aguilar-Vafaie, M.E.; Ahn, C.-K.; Ahn, H.-N.; Alcalay, L.; et al. Perceptions of aging across 26 cultures and their culture-level associates. Psychol. Aging 2009, 24, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, M.S.; Fiske, S.T. Modern attitudes toward older adults in the aging world: A cross-cultural meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 993–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, S.; Mariano, J.; Mendonça, J.; De Tavernier, W.; Hess, M.; Naegele, L.; Peixeiro, F.; Martins, D. Determinants of ageism against older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vauclair, C.M.; Hanke, K.; Huang, L.L.; Abrams, D. Are Asian cultures really less ageist than Western ones? It depends on the questions asked. Int. J. Psychol. 2017, 52, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstede, G.; Bond, M.H. The Confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth. Organ. Dyn. 1988, 16, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.; Baker, W.E. Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 65, 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFraniere, S. China might force visits to Mom and Dad. New York Times 29 January 2011. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Ackerman, L.S.; Chopik, W.J. Cross-cultural comparisons in implicit and explicit age bias. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 47, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, L.; Palacios-Espinosa, X. Stereotypes about old age, social support, aging anxiety and evaluations of one's own health. J. Soc. Issues 2016, 72, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrie, S.I.; Eom, K.; Moza, D.; Gavreliuc, A.; Kim, H.S. Cultural variability in the association between age and well-being: The role of uncertainty avoidance. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, R.; Lim-Soh, J.W. Ageism linked to culture, not demographics: Evidence from an 8-billion-word corpus across 20 countries. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, 1791–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pain, R.; Mowl, G.; Talbot, C. Difference and the negotiation of ‘old age’. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2000, 18, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamlath, S. Human development and national culture: A multivariate exploration. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 133, 907–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hövermann, A.; Messner, S.F. Explaining when older persons are perceived as a burden: A cross-national analysis of ageism. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2023, 64, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence; Cambridge University Press: New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, B.; Wolfers, J. Economic growth and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin paradox (No. w14282); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; North, M.S.; Zhang, X. Pension Tension: Retirement Annuity Fosters Ageism Across Countries and Cultures. Innov. Aging 2023, 7, igad080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2022; United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Country and survey year | N |

| Argentina 2012/13 | 815 |

| Australia 2012 | 1,089 |

| Brazil 2014 | 1,214 |

| Chile 2012 | 801 |

| China 2012/13 | 1,945 |

| Colombia 2012 | 1,294 |

| Estonia 2011 | 1,108 |

| Germany 2013 | 1,406 |

| Hong Kong 2014 | 788 |

| Japan 2010 | 1,571 |

| South Korea 2010 | 977 |

| Malaysia 2012 | 1,177 |

| Mexico 2012 | 1,793 |

| Morocco 2011 | 1,076 |

| Netherlands 2012 | 1,119 |

| New Zealand 2011/12 | 547 |

| Pakistan 2012 | 1,148 |

| Peru 2012 | 1,031 |

| Philippines 2012 | 1,001 |

| Poland 2012 | 689 |

| Romania 2012 | 1,105 |

| Russia 2011 | 1,972 |

| Singapore 2012 | 1,484 |

| Slovenia 2011 | 758 |

| Spain 2011 | 854 |

| Sweden 2011 | 852 |

| Thailand 2013 | 1,050 |

| Trinidad and Tobago 2010/11 | 728 |

| Turkey 2011 | 1,406 |

| United States 2011 | 1,683 |

| Uruguay 2011 | 751 |

| Item | Scoring method |

| “Social position: People in their 70s” (n = 33,402). | A ten-point Likert scale ranging from "extremely high" to "extremely low" was used for the analysis with the scores from 1 to 10 given. |

| “People over 70: are seen as friendly” (n = 33,619), “People over 70: are seen as competent” (n = 33,421), “People over 70: viewed with respect” (n = 33,831). | A six-point Likert scale ranging from " very likely to be viewed that way" to "not at all likely to be viewed that way " was used for the analysis with the scores from 0 to 5 given. |

| “Is a 70-year old boss acceptable” (n = 33,878). | A ten-point Likert scale ranging from "completely acceptable" to "completely unacceptable" was used for the analysis with the scores from 1 to 10 given. |

| “Older people are not respected much these days” (n = 34,203), “Older people get more than their fair share from the government” (n = 33,159), “Older people are a burden on society” (n = 33,885), “Companies that employ young people perform better than those that employ people of different ages” (n = 32,456), “Old people have too much political influence” (n = 31,904). | A four-point Likert scale ranging from "Strongly disagree" to "Strongly agree" was used for the analysis with the scores from 1 to 4 given. |

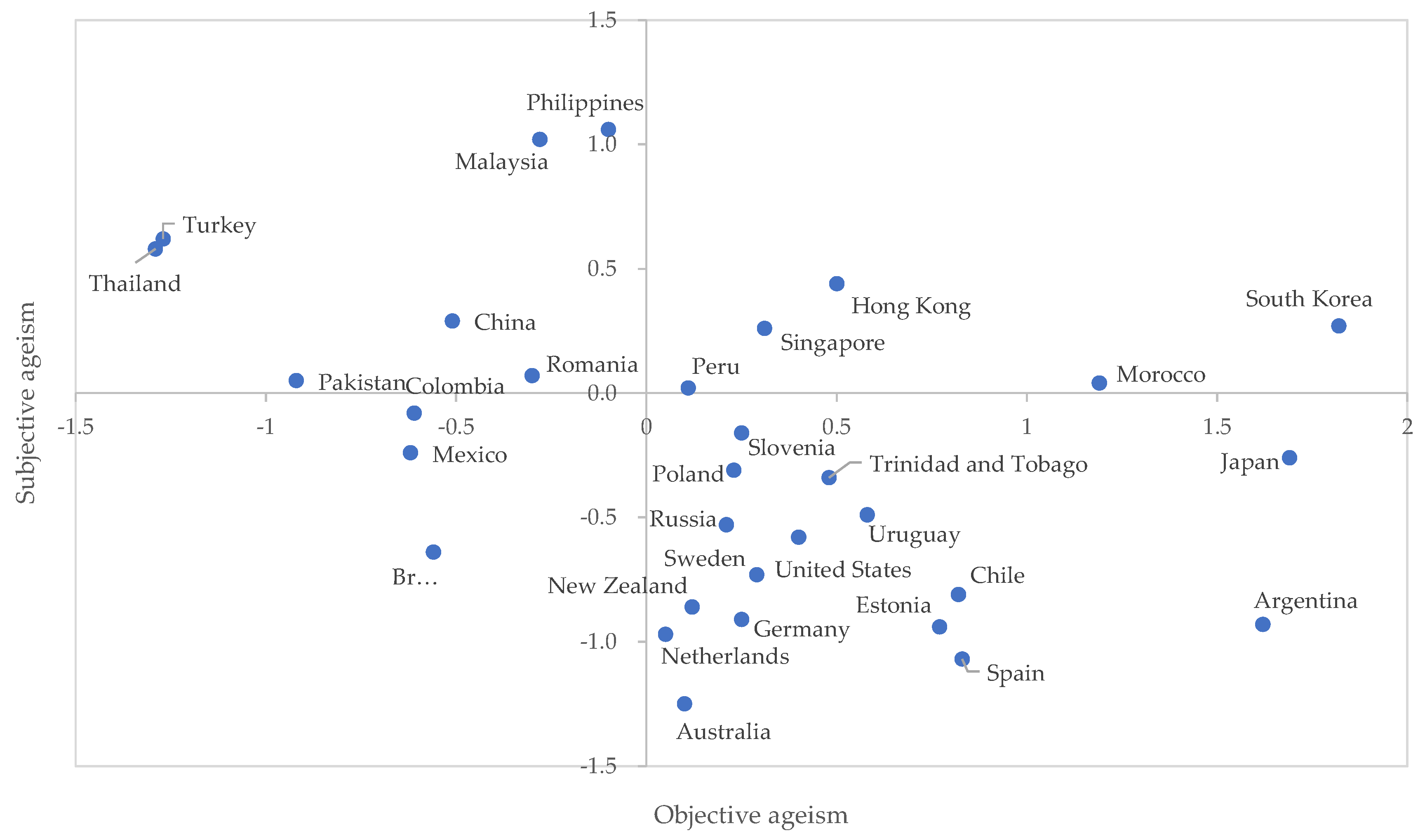

| Items | Objective ageism | Subjective ageism |

| People over 70: are seen as competent | 0.828 | -0.092 |

| People over 70: viewed with respect | 0.807 | -0.198 |

| People over 70: are seen as friendly | 0.716 | 0.282 |

| Companies that employ young people perform better than those that employ people of different ages | -0.188 | 0.741 |

| Old people have too much political influence | -0.202 | 0.738 |

| Older people get more than their fair share from the government | 0.088 | 0.595 |

| Older people are a burden on society | 0.279 | 0.528 |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

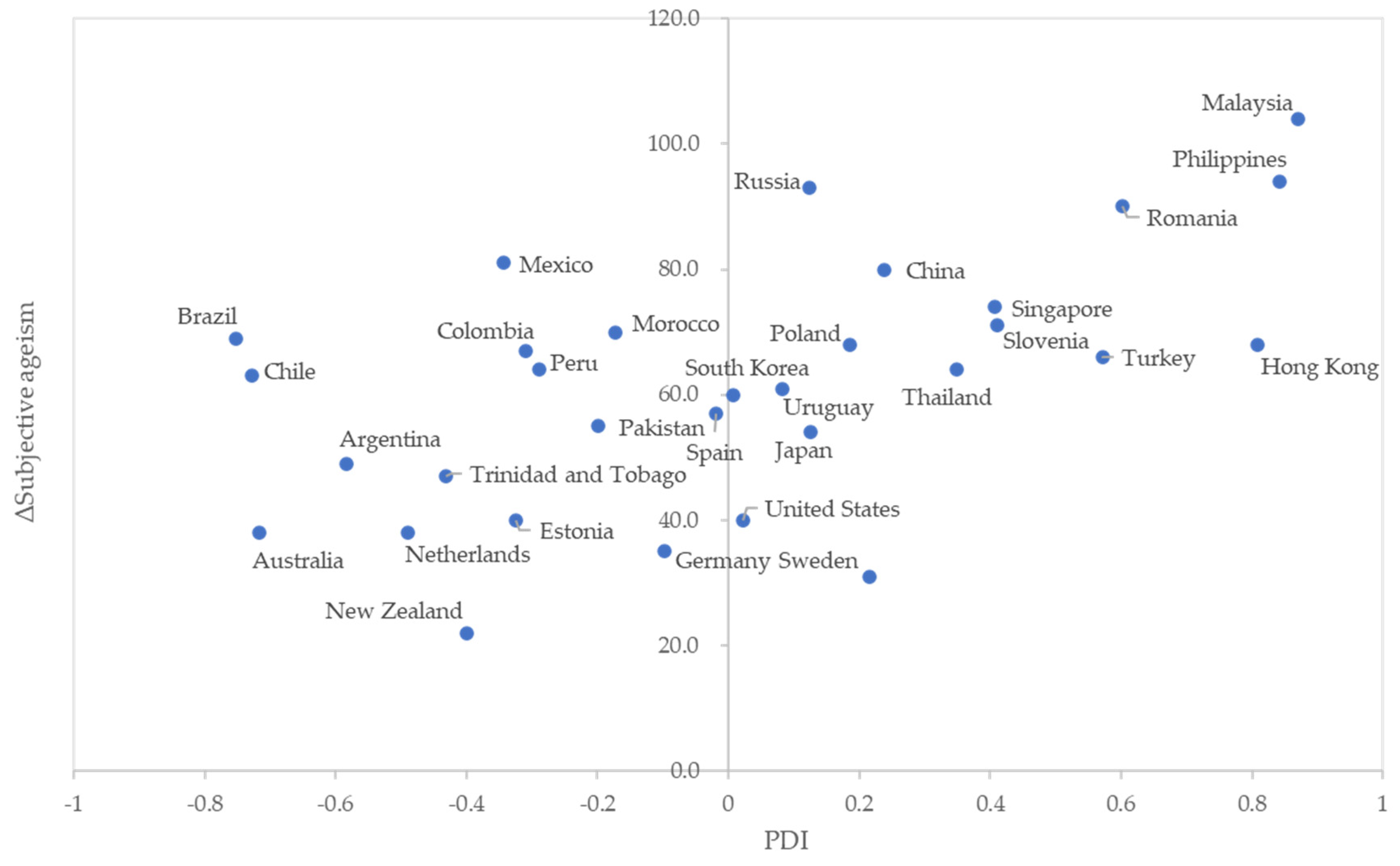

| 1 | PDI | 61.710 | 19.683 | -0.537** | 0.121 | 0.044 | 0.319 | -0.327 | -0.064 | 0.643*** | |||

| 2 | IDV | 40.870 | 23.332 | -0.639*** | -0.202 | 0.191 | -0.28 | 0.313 | -0.03 | -0.372 | |||

| 3 | UAI | 66.710 | 24.089 | 0.112 | -0.152 | 0.004 | -0.234 | 0.171 | 0.178 | -0.295 | |||

| 4 | MAS | 48.520 | 18.266 | 0.109 | -0.027 | -0.032 | -0.12 | 0.042 | 0.108 | 0.012 | |||

| 5 | LTO | 46.632 | 25.141 | 0.005 | 0.000 | -0.111 | -0.089 | -0.664*** | -0.033 | 0.298 | |||

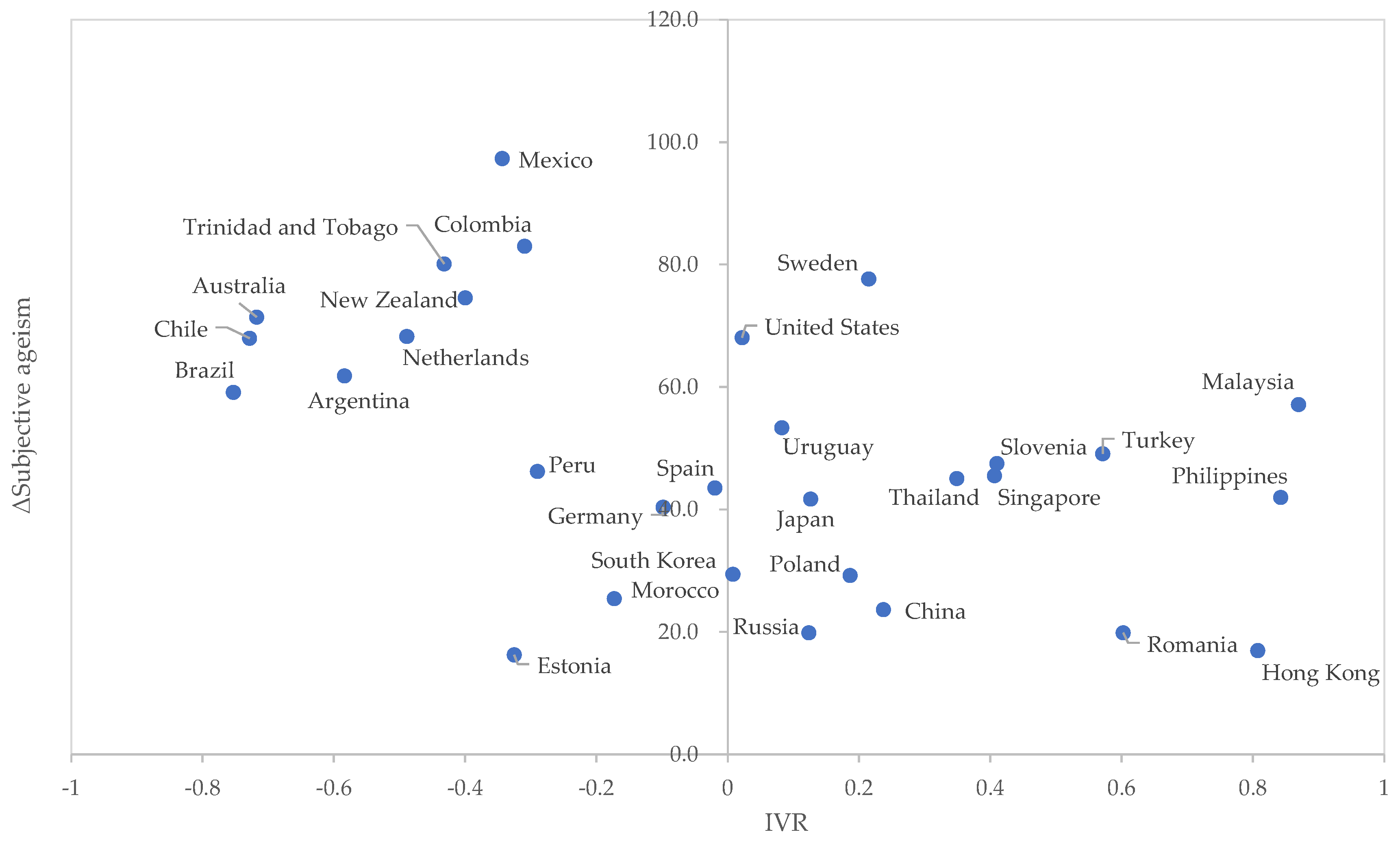

| 6 | IVR | 48.449 | 23.302 | -0.291 | 0.245 | -0.078 | 0.005 | -0.533** | -0.109 | -0.455* | |||

| 7 | Objective ageism | -0.198 | 0.775 | -0.268 | 0.195 | 0.152 | 0.062 | 0.213 | -0.080 | -0.227 | |||

| 8 | Subjective ageism | 0.237 | 0.615 | 0.700*** | -0.646** | -0.216 | 0.162 | 0.018 | -0.307 | -0.358* | |||

| 9 | Population ages 65 and above (% of total population) | 11.679 | 5.157 | -0.474** | 0.552** | 0.126 | -0.116 | 0.477** | -0.08 | 0.431* | 0.550** | ||

| 10 | Change in percentage aged 65 and above | 1.729 | 1.146 | -0.221 | -0.026 | 0.108 | 0.15 | 0.474** | -0.074 | 0.314 | 0.021 | 0.509** | |

| 11 | Log of Gross domestic product per capita, constant prices | 10.098 | 0.683 | -0.441* | 0.494** | -0.266 | -0.14 | 0.321 | 0.281 | 0.355 | 0.425* | 0.652*** | 0.297 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| β | p | β | p | |

| Population ages 65 and above (% of total population) | 0.696 | 0.003** | 0.638 | 0.002** |

| Change in percentage aged 65 and above | -0.402 | 0.025* | -0.39 | 0.005 |

| Log of Gross domestic product per capita, constant prices | 0.091 | 0.638 | -0.153 | 0.348 |

| PDI | -0.484 | 0.001** | ||

| IVR | 0.232 | 0.084 | ||

| R2 | 0.430 | 0.704 | ||

| F | 6.790** | 0.010 | 11.883*** | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).