Submitted:

15 August 2024

Posted:

19 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Material and Methods

2. Molecular Background of Psoriasis

2.1. Genetics of Psoriasis

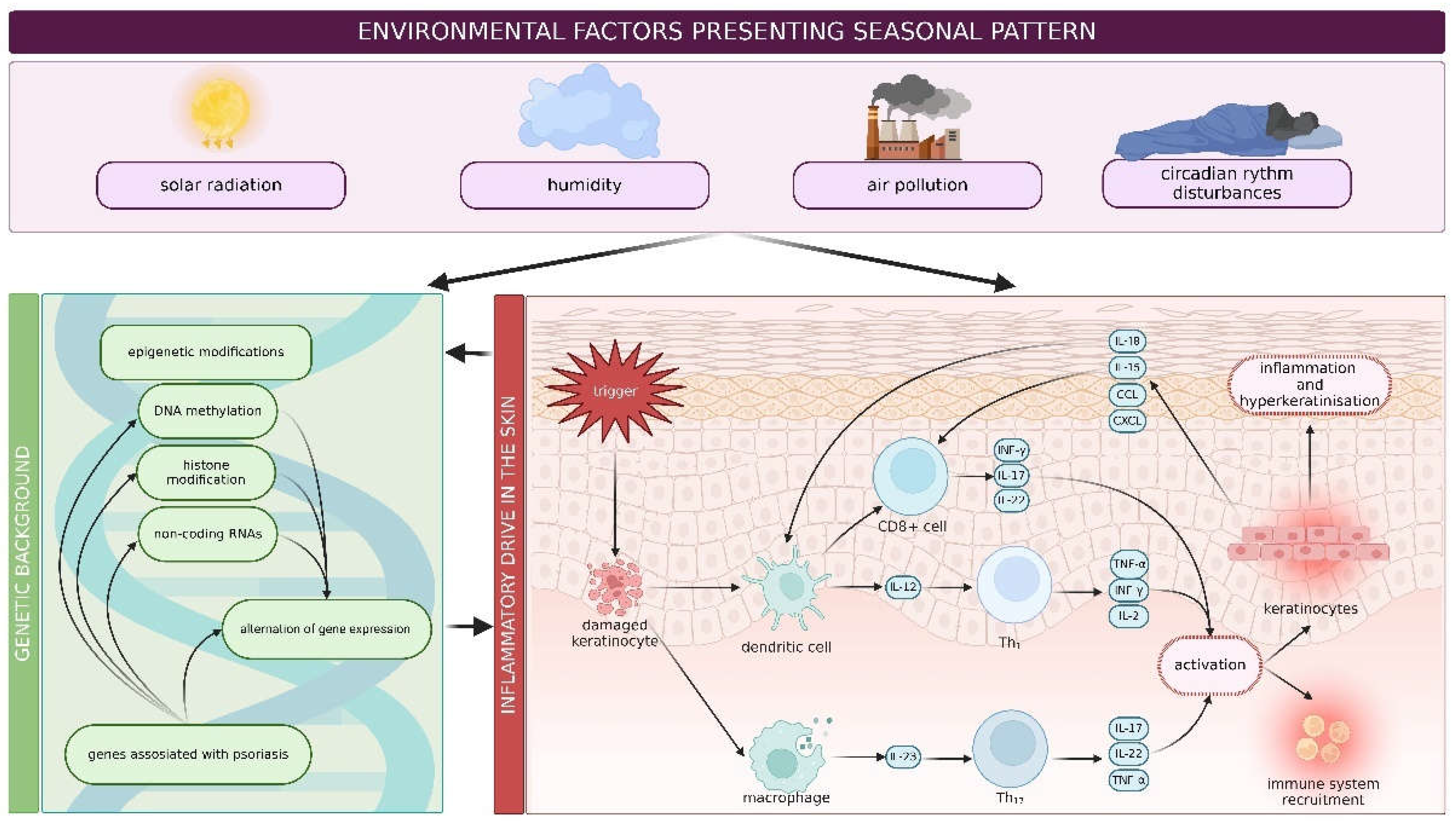

2.2. Epigenetics of Psoriasis

3.2.1. DNA Methylation

3.2.2. Histone Modification

3.2.3. Non-Coding RNA

3.2.4. Seasonality of Epigenetics

3.3. Cellular Pathomechanisms in Psoriatic Disease

4. Environmental Factors Effecting Psoriasis

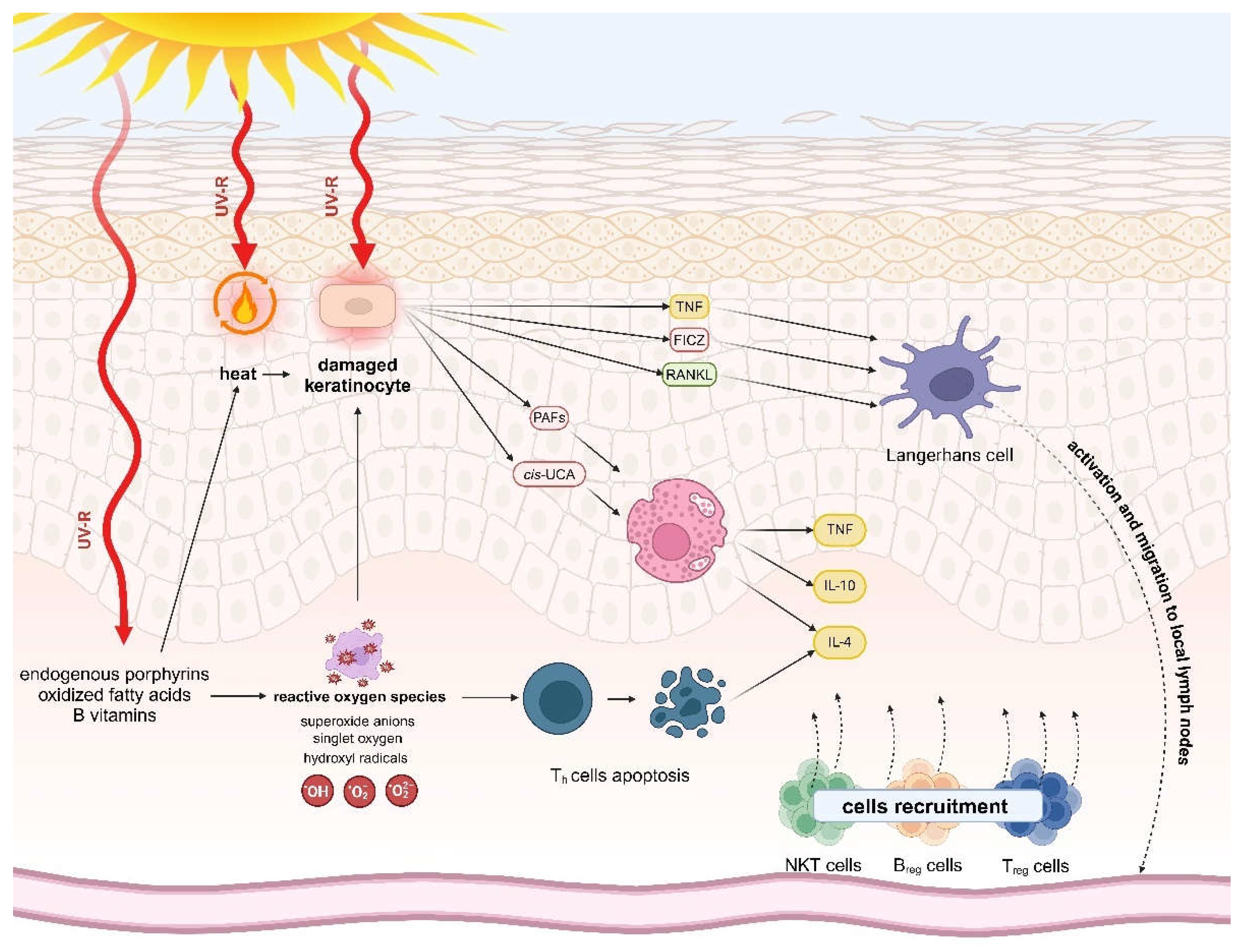

4.1. Sunlight

4.2. Humidity

4.3. Air Pollution

4.4. Circadian Rhythm

5. Geoepidemiology of Psoriasis

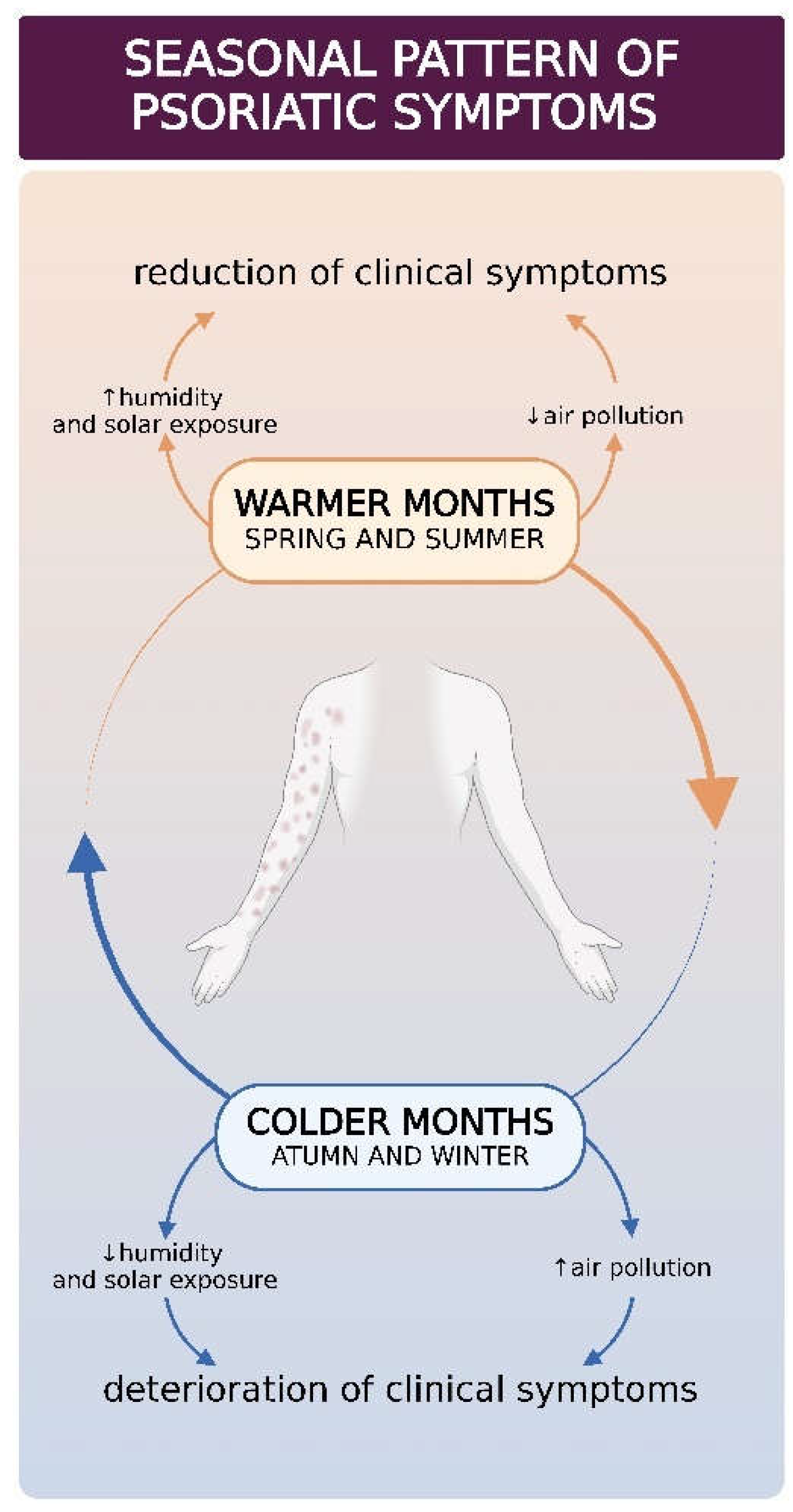

6. Seasonality of Psoriasis

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nestle, F.O.; Kaplan, D.H.; Barker, J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2009, 361, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchlin, C.T.; Colbert, R.A.; Gladman, D.D. Psoriatic Arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017, 376, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, R.; Symmons, D.P.; Griffiths, C.E.; Ashcroft, D.M.; Identification; Management of, P. ; Associated ComorbidiTy project, t. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol 2013, 133, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villani, A.P.; Rouzaud, M.; Sevrain, M.; Barnetche, T.; Paul, C.; Richard, M.A.; Beylot-Barry, M.; Misery, L.; Joly, P.; Le Maitre, M.; et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015, 73, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinaghi, F.; Calov, M.; Kristensen, L.E.; Gladman, D.D.; Coates, L.C.; Jullien, D.; Gottlieb, A.B.; Gisondi, P.; Wu, J.J.; Thyssen, J.P.; et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019, 80, 251–265 e219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogdie, A.; Weiss, P. The Epidemiology of Psoriatic Arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2015, 41, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springate, D.A.; Parisi, R.; Kontopantelis, E.; Reeves, D.; Griffiths, C.E.; Ashcroft, D.M. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of patients with psoriasis: a U.K. population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol 2017, 176, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.T.; Li, Q.; Wasikowski, R.; Mehta, N.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Elder, J.T.; Zhou, X.; Tsoi, L.C. Shared genetic risk factors and causal association between psoriasis and coronary artery disease. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahadeen, E.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Gislason, G.; Hansen, P.R.; Ahlehoff, O. Nationwide population-based study of cause-specific death rates in patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015, 29, 1002–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, J.M.; Feldman, S.R.; Stern, R.S.; Thomas, J.; Rolstad, T.; Margolis, D.J. Determinants of quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a study from the US population. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004, 51, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrazzo, M.; Cipolla, S.; Signoriello, S.; Camerlengo, A.; Calabrese, G.; Giordano, G.M.; Argenziano, G.; Galderisi, S. A systematic review on shared biological mechanisms of depression and anxiety in comorbidity with psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and hidradenitis suppurativa. Eur Psychiatry 2021, 64, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalenques, I.; Bourlot, F.; Martinez, E.; Pereira, B.; D'Incan, M.; Lauron, S.; Rondepierre, F. Prevalence and Odds of Anxiety Disorders and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adults with Psoriasis: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acta Derm Venereol 2022, 102, adv00769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marek-Jozefowicz, L.; Czajkowski, R.; Borkowska, A.; Nedoszytko, B.; Zmijewski, M.A.; Cubala, W.J.; Slominski, A.T. The Brain-Skin Axis in Psoriasis-Psychological, Psychiatric, Hormonal, and Dermatological Aspects. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, E.J.; Fox, K.M.; Patel, V.; Chiou, C.F.; Dann, F.; Lebwohl, M. Association of patient-reported psoriasis severity with income and employment. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007, 57, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, C.E.; Barker, J.N. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet 2007, 370, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaie, F.; Omraninava, M.; Gorabi, A.M.; Khosrojerdi, A.; Aslani, S.; Yazdchi, A.; Torkamandi, S.; Mikaeili, H.; Sathyapalan, T.; Sahebkar, A. Etiopathogenesis of Psoriasis from Genetic Perspective: An updated Review. Current Genomics 2022, 23, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiro, R.; Coto, P.; Gonzalez-Lara, L.; Coto, E. Genetic Variants of the NF-kappaB Pathway: Unraveling the Genetic Architecture of Psoriatic Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonnberg, A.S.; Skov, L.; Skytthe, A.; Kyvik, K.O.; Pedersen, O.B.; Thomsen, S.F. Heritability of psoriasis in a large twin sample. Br J Dermatol 2013, 169, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, S.; Li, Q.; Rahman, P.; Chandran, V. Insights into the pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis from genetic studies. Semin Immunopathol 2021, 43, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capon, F. The Genetic Basis of Psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuaga, A.B.; Ramirez, J.; Canete, J.D. Psoriatic Arthritis: Pathogenesis and Targeted Therapies. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, A.; Siewert, K.; Stohr, J.; Besgen, P.; Kim, S.M.; Ruhl, G.; Nickel, J.; Vollmer, S.; Thomas, P.; Krebs, S.; et al. Melanocyte antigen triggers autoimmunity in human psoriasis. J Exp Med 2015, 212, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Psoriasis Genetics, C. The International Psoriasis Genetics Study: assessing linkage to 14 candidate susceptibility loci in a cohort of 942 affected sib pairs. Am J Hum Genet 2003, 73, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroon, M.; Winchester, R.; Giles, J.T.; Heffernan, E.; FitzGerald, O. Clinical and genetic associations of radiographic sacroiliitis and its different patterns in psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017, 35, 270–276. [Google Scholar]

- Capon, F.; Munro, M.; Barker, J.; Trembath, R. Searching for the major histocompatibility complex psoriasis susceptibility gene. J Invest Dermatol 2002, 118, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Chada, L.M.; Balak, D.; Cohen, J.M.; Ogdie, A.; Merola, J.F.; Gottlieb, A.B. Measurement properties of instruments assessing psoriatic arthritis symptoms for psoriasis clinical trials: a systematic literature review. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2020, 16, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, J.L.; Gao, X.H.; Chen, H.D.; Li, Y.H. Association of -619C/T polymorphism in CDSN gene and psoriasis risk: a meta-analysis. Genet Mol Res 2011, 10, 3632–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonca, N.; Leclerc, E.A.; Caubet, C.; Simon, M.; Guerrin, M.; Serre, G. Corneodesmosomes and corneodesmosin: from the stratum corneum cohesion to the pathophysiology of genodermatoses. Eur J Dermatol 2011, 21 Suppl 2, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.T.; Cao, L.; Roberson, E.D.; Pierson, K.C.; Yang, C.F.; Joyce, C.E.; Ryan, C.; Duan, S.; Helms, C.A.; Liu, Y.; et al. PSORS2 is due to mutations in CARD14. Am J Hum Genet 2012, 90, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs-Telem, D.; Sarig, O.; van Steensel, M.A.; Isakov, O.; Israeli, S.; Nousbeck, J.; Richard, K.; Winnepenninckx, V.; Vernooij, M.; Shomron, N.; et al. Familial pityriasis rubra pilaris is caused by mutations in CARD14. Am J Hum Genet 2012, 91, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, K.; Muto, M.; Akiyama, M. CARD14 c.526G>C (p.Asp176His) is a significant risk factor for generalized pustular psoriasis with psoriasis vulgaris in the Japanese cohort. J Invest Dermatol 2014, 134, 1755–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, I.Y.; de Guzman Strong, C. The Molecular Revolution in Cutaneous Biology: EDC and Locus Control. J Invest Dermatol 2017, 137, e101–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cid, R.; Riveira-Munoz, E.; Zeeuwen, P.L.; Robarge, J.; Liao, W.; Dannhauser, E.N.; Giardina, E.; Stuart, P.E.; Nair, R.; Helms, C.; et al. Deletion of the late cornified envelope LCE3B and LCE3C genes as a susceptibility factor for psoriasis. Nat Genet 2009, 41, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveira-Munoz, E.; He, S.M.; Escaramis, G.; Stuart, P.E.; Huffmeier, U.; Lee, C.; Kirby, B.; Oka, A.; Giardina, E.; Liao, W.; et al. Meta-analysis confirms the LCE3C_LCE3B deletion as a risk factor for psoriasis in several ethnic groups and finds interaction with HLA-Cw6. J Invest Dermatol 2011, 131, 1105–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Meng, X.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Ren, L. Association Between Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Non-Receptor Type 22 (PTPN22) Polymorphisms and Risk of Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Meta-analysis. Med Sci Monit 2017, 23, 2619–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huraib, G.B.; Al Harthi, F.; Arfin, M.; Aljamal, A.; Alrawi, A.S.; Al-Asmari, A. Association of Functional Polymorphism in Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Nonreceptor 22 (PTPN22) Gene with Vitiligo. Biomark Insights 2020, 15, 1177271920903038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Low, H.Q.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Ellinghaus, E.; Han, J.; Estivill, X.; Sun, L.; Zuo, X.; Shen, C.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies multiple novel associations and ethnic heterogeneity of psoriasis susceptibility. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 6916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zheng, X.; Jin, H. Immune Regulation of TNFAIP3 in Psoriasis through Its Association with Th1 and Th17 Cell Differentiation and p38 Activation. J Immunol Res 2020, 2020, 5980190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisielnicka, A.; Sobalska-Kwapis, M.; Purzycka-Bohdan, D.; Nedoszytko, B.; Zabłotna, M.; Seweryn, M.; Strapagiel, D.; Nowicki, R.J.; Reich, A.; Samotij, D.; et al. The Analysis of a Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) of Overweight and Obesity in Psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Boldrup, L.; Coates, P.J.; Fahraeus, R.; Nylander, E.; Loizou, C.; Olofsson, K.; Norberg-Spaak, L.; Garskog, O.; Nylander, K. Epigenetic regulation of OAS2 shows disease-specific DNA methylation profiles at individual CpG sites. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 32579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, E.D.; Liu, Y.; Ryan, C.; Joyce, C.E.; Duan, S.; Cao, L.; Martin, A.; Liao, W.; Menter, A.; Bowcock, A.M. A subset of methylated CpG sites differentiate psoriatic from normal skin. J Invest Dermatol 2012, 132, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, D.; Ekman, A.K.; Bivik Eding, C.; Enerback, C. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Profiling Identifies Differential Methylation in Uninvolved Psoriatic Epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 2018, 138, 1088–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, A.; Senapati, S.; Roy, S.; Chatterjee, G.; Chatterjee, R. Epigenome-wide DNA methylation regulates cardinal pathological features of psoriasis. Clinical Epigenetics 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Su, Y.; Zhao, M.; Huang, W.; Lu, Q. Abnormal histone modifications in PBMCs from patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol 2011, 21, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovejero-Benito, M.C.; Reolid, A.; Sanchez-Jimenez, P.; Saiz-Rodriguez, M.; Munoz-Aceituno, E.; Llamas-Velasco, M.; Martin-Vilchez, S.; Cabaleiro, T.; Roman, M.; Ochoa, D.; et al. Histone modifications associated with biological drug response in moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Exp Dermatol 2018, 27, 1361–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopytalska, K.; Ciechanowicz, P.; Wiszniewski, K.; Szymanska, E.; Walecka, I. The Role of Epigenetic Factors in Psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Ganguly, T.; Chatterjee, R. Emerging roles of non-coding RNAs in psoriasis pathogenesis. Funct Integr Genomics 2023, 23, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonatos, C.; Grafanaki, K.; Asmenoudi, P.; Xiropotamos, P.; Nani, P.; Georgakilas, G.K.; Georgiou, S.; Vasilopoulos, Y. Contribution of the Environment, Epigenetic Mechanisms and Non-Coding RNAs in Psoriasis. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Shi, R.; Ma, R.; Tang, X.; Gong, Y.; Yu, Z.; Shi, Y. The role of microRNA in psoriasis: A review. Exp Dermatol 2023, 32, 1598–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu-Arrom, L.; Puig, L. Genetic and Epigenetic Mechanisms of Psoriasis. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Eghtedarian, R.; Taheri, M.; Rakhshan, A. The eminent roles of ncRNAs in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Noncoding RNA Res 2020, 5, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Shi, G.; Pan, Z.; Cheng, W.; Xu, L.; Lin, X.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ji, G.; Lv, X.; et al. Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis for the Identification of Key lncRNAs, mRNAs, and Potential Drugs in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinomas. Int J Gen Med 2023, 16, 2063–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, W.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Y. Identification of potential key mRNAs and LncRNAs for psoriasis by bioinformatic analysis using weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Mol Genet Genomics 2020, 295, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Mercer, T.R.; Shearwood, A.M.; Siira, S.J.; Hibbs, M.E.; Mattick, J.S.; Rackham, O.; Filipovska, A. Mapping of mitochondrial RNA-protein interactions by digital RNase footprinting. Cell Rep 2013, 5, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopico, X.C.; Evangelou, M.; Ferreira, R.C.; Guo, H.; Pekalski, M.L.; Smyth, D.J.; Cooper, N.; Burren, O.S.; Fulford, A.J.; Hennig, B.J.; et al. Widespread seasonal gene expression reveals annual differences in human immunity and physiology. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 7000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brembilla, N.C.; Boehncke, W.H. Revisiting the interleukin 17 family of cytokines in psoriasis: pathogenesis and potential targets for innovative therapies. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1186455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhardt, A.; Prinz, I. Whodunit? The Contribution of Interleukin (IL)-17/IL-22-Producing gammadelta T Cells, alphabeta T Cells, and Innate Lymphoid Cells to the Pathogenesis of Spondyloarthritis. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reali, E.; Ferrari, D. From the Skin to Distant Sites: T Cells in Psoriatic Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, J.A. Mast cells as important regulators in the development of psoriasis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1022986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielke, C.; Nielsen, J.E.; Lin, J.S.; Barron, A.E. Between good and evil: Complexation of the human cathelicidin LL-37 with nucleic acids. Biophys J 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzuncakmak, T.K.; Karadag, A.S.; Ozkanli, S.; Akbulak, O.; Ozlu, E.; Akdeniz, N.; Oguztuzun, S. Alteration of tissue expression of human beta defensin-1 and human beta defensin-2 in psoriasis vulgaris following phototherapy. Biotech Histochem 2020, 95, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, K. Pathogenic role of S100 proteins in psoriasis. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1191645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Wang, M.; Gao, H.; Zheng, A.; Li, J.; Mu, D.; Tong, J. The Role of Helper T Cells in Psoriasis. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 788940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schon, M.P.; Erpenbeck, L. The Interleukin-23/Interleukin-17 Axis Links Adaptive and Innate Immunity in Psoriasis. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonel, G.; Conrad, C.; Laggner, U.; Di Meglio, P.; Grys, K.; McClanahan, T.K.; Blumenschein, W.M.; Qin, J.Z.; Xin, H.; Oldham, E.; et al. Cutting edge: A critical functional role for IL-23 in psoriasis. J Immunol 2010, 185, 5688–5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, M.P. Adaptive and Innate Immunity in Psoriasis and Other Inflammatory Disorders. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishimoto, T.; Arakawa, Y.; Vural, S.; Stohr, J.; Vollmer, S.; Galinski, A.; Siewert, K.; Ruhl, G.; Poluektov, Y.; Delcommenne, M.; et al. Multiple environmental antigens may trigger autoimmunity in psoriasis through T-cell receptor polyspecificity. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1374581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, B.; Berneburg, M.; Baumler, W.; Karrer, S. Phototherapy: Theory and practice. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2023, 21, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyscin, J.W.; Jaroslawski, J.; Rajewska-Wiech, B.; Sobolewski, P.S.; Narbutt, J.; Lesiak, A.; Pawlaczyk, M. Effectiveness of heliotherapy for psoriasis clearance in low and mid-latitudinal regions: a theoretical approach. J Photochem Photobiol B 2012, 115, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, L.; Barnard, I.R.M.; McMillan, L.; Ibbotson, S.H.; Brown, C.T.A.; Eadie, E.; Wood, K. Depth Penetration of Light into Skin as a Function of Wavelength from 200 to 1000 nm. Photochem Photobiol 2022, 98, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knak, A.; Regensburger, J.; Maisch, T.; Baumler, W. Exposure of vitamins to UVB and UVA radiation generates singlet oxygen. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2014, 13, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Thaler, A.K.; Kamenisch, Y.; Berneburg, M. The role of ultraviolet radiation in melanomagenesis. Exp Dermatol 2010, 19, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dood, J.; Beckstead, A.A.; Li, X.B.; Nguyen, K.V.; Burrows, C.J.; Improta, R.; Kohler, B. Photoinduced Electron Transfer in DNA: Charge Shift Dynamics Between 8-Oxo-Guanine Anion and Adenine. J Phys Chem B 2015, 119, 7491–7502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagener, F.A.; Carels, C.E.; Lundvig, D.M. Targeting the redox balance in inflammatory skin conditions. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 9126–9167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, J.J.; Gallo, R.L.; Krutmann, J. Photoimmunology: how ultraviolet radiation affects the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2019, 19, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthier-Vergnes, O.; Bermond, F.; Flacher, V.; Massacrier, C.; Schmitt, D.; Péguet-Navarro, J. TNF-alpha enhances phenotypic and functional maturation of human epidermal Langerhans cells and induces IL-12 p40 and IP-10/CXCL-10 production. FEBS Lett 2005, 579, 3660–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, J.J.; Cowing-Zitron, C.; Nakatsuji, T.; Muehleisen, B.; Muto, J.; Borkowski, A.W.; Martinez, L.; Greidinger, E.L.; Yu, B.D.; Gallo, R.L. Ultraviolet radiation damages self noncoding RNA and is detected by TLR3. Nat Med 2012, 18, 1286–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, J.J.; Kydonieus, A.F.; Murphy, G.F. cis-urocanic acid induces mast cell degranulation and release of preformed TNF-alpha: A possible mechanism linking UVB and cis-urocanic acid to immunosuppression of contact hypersensitivity. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol 1999, 12, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón-Salinas, R.; Chen, L.; Chávez-Blanco, A.D.; Limón-Flores, A.Y.; Ma, Y.; Ullrich, S.E. An essential role for platelet-activating factor in activating mast cell migration following ultraviolet irradiation. J Leukoc Biol 2014, 95, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, X.; Shen, X.; Lin, M.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, J. NF-kappaB in biology and targeted therapy: new insights and translational implications. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.; Wu, S.B.; Hong, C.H.; Yu, H.S.; Wei, Y.H. Molecular Mechanisms of UV-Induced Apoptosis and Its Effects on Skin Residential Cells: The Implication in UV-Based Phototherapy. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 6414–6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Jiang, A.; Veenstra, J.; Ozog, D.M.; Mi, Q.S. The Roles of Skin Langerhans Cells in Immune Tolerance and Cancer Immunity. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukunaga, A.; Khaskhely, N.M.; Ma, Y.; Sreevidya, C.S.; Taguchi, K.; Nishigori, C.; Ullrich, S.E. Langerhans cells serve as immunoregulatory cells by activating NKT cells. J Immunol 2010, 185, 4633–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizoguchi, A.; Mizoguchi, E.; Takedatsu, H.; Blumberg, R.S.; Bhan, A.K. Chronic intestinal inflammatory condition generates IL-10-producing regulatory B cell subset characterized by CD1d upregulation. Immunity 2002, 16, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nast, A.; Smith, C.; Spuls, P.I.; Avila Valle, G.; Bata-Csorgo, Z.; Boonen, H.; De Jong, E.; Garcia-Doval, I.; Gisondi, P.; Kaur-Knudsen, D.; et al. EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the systemic treatment of Psoriasis vulgaris - Part 1: treatment and monitoring recommendations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020, 34, 2461–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nast, A.; Smith, C.; Spuls, P.I.; Avila Valle, G.; Bata-Csorgo, Z.; Boonen, H.; De Jong, E.; Garcia-Doval, I.; Gisondi, P.; Kaur-Knudsen, D.; et al. EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the systemic treatment of Psoriasis vulgaris - Part 2: specific clinical and comorbid situations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021, 35, 281–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, R.; Weatherhead, S.C.; Pawitri, A.; Smith, G.R.; Rider, A.; Grantham, H.J.; Cockell, S.J.; Reynolds, N.J. Therapeutic wavelengths of ultraviolet B radiation activate apoptotic, circadian rhythm, redox signalling and key canonical pathways in psoriatic epidermis. Redox Biol 2021, 41, 101924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, E.; Kheradmand, S.; Miller, R. An Update on Narrowband Ultraviolet B Therapy for the Treatment of Skin Diseases. Cureus 2021, 13, e19182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska, M.; Narbutt, J.; Lesiak, A. Blue Light in Dermatology. Life (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, D.; Uzunbajakava, N.E.; van Abeelen, F.; Oversluizen, G.; Peppelman, M.; van Erp, P.E.J.; van de Kerkhof, P.C.M. Effects of blue light on inflammation and skin barrier recovery following acute perturbation. Pilot study results in healthy human subjects. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2018, 34, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstabl, A.; Hoff-Lesch, S.; Merk, H.F.; von Felbert, V. Prospective randomized study on the efficacy of blue light in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatology 2011, 223, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinpenning, M.M.; Otero, M.E.; van Erp, P.E.; Gerritsen, M.J.; van de Kerkhof, P.C. Efficacy of blue light vs. red light in the treatment of psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012, 26, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maari, C.; Viau, G.; Bissonnette, R. Repeated exposure to blue light does not improve psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003, 49, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, S.; Liebmann, J.; Born, M.; Merk, H.F.; von Felbert, V. Prospective Randomized Long-Term Study on the Efficacy and Safety of UV-Free Blue Light for Treating Mild Psoriasis Vulgaris. Dermatology 2015, 231, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, P.; Scragg, R. A short history of phototherapy, vitamin D and skin disease. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2017, 16, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzyscin, J.W.; Guzikowski, J.; Czerwinska, A.; Lesiak, A.; Narbutt, J.; Jaroslawski, J.; Sobolewski, P.S.; Rajewska-Wiech, B.; Wink, J. 24 hour forecast of the surface UV for the antipsoriatic heliotherapy in Poland. J Photochem Photobiol B 2015, 148, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzyscin, J.W.; Narbutt, J.; Lesiak, A.; Jaroslawski, J.; Sobolewski, P.S.; Rajewska-Wiech, B.; Szkop, A.; Wink, J.; Czerwinska, A. Perspectives of the antipsoriatic heliotherapy in Poland. J Photochem Photobiol B 2014, 140, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melandri, D.; Albano, V.M.; Venturi, M.; Flamigni, A.; Vairetti, M. Efficacy of combined liman peloid baths and heliotherapy in the treatment of psoriasis at Cervia spa, Emilia, Italy. Int J Biometeorol 2020, 64, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmanuel, T.; Lybaek, D.; Johansen, C.; Iversen, L. Effect of Dead Sea Climatotherapy on Psoriasis; A Prospective Cohort Study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, T.; Petersen, A.; Houborg, H.I.; Ronsholdt, A.B.; Lybaek, D.; Steiniche, T.; Bregnhoj, A.; Iversen, L.; Johansen, C. Climatotherapy at the Dead Sea for psoriasis is a highly effective anti-inflammatory treatment in the short term: An immunohistochemical study. Exp Dermatol 2022, 31, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavinsky, V.; Helmy, J.; Vroman, J.; Valdebran, M. Solar ultraviolet radiation exposure in workers with outdoor occupations: a systematic review and call to action. Int J Dermatol 2024, 63, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shraim, R.; Farran, M.Z.; He, G.; Marunica Karsaj, J.; Zgaga, L.; McManus, R. Systematic review on gene-sun exposure interactions in skin cancer. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2023, 11, e2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belzer, A.; Parker, E.R. Climate Change, Skin Health, and Dermatologic Disease: A Guide for the Dermatologist. Am J Clin Dermatol 2023, 24, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzyscin, J.W.; Lesiak, A.; Narbutt, J.; Sobolewski, P.; Guzikowski, J. Perspectives of UV nowcasting to monitor personal pro-health outdoor activities. J Photochem Photobiol B 2018, 184, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwinska, A.; Krzyscin, J. Measurements of biologically effective solar radiation using erythemal weighted broadband meters. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2024, 23, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, P.; Weger, W.; Patra, V.; Gruber-Wackernagel, A.; Byrne, S.N. Desired response to phototherapy vs photoaggravation in psoriasis: what makes the difference? Exp Dermatol 2016, 25, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, K.J.; Watson, R.E.; Cotterell, L.F.; Brenn, T.; Griffiths, C.E.; Rhodes, L.E. Severely photosensitive psoriasis: a phenotypically defined patient subset. J Invest Dermatol 2009, 129, 2861–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, C.M.; Brotas, A.M.; Ramos-e-Silva, M.; Carneiro, S. Isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 2013, 31, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, L.C.; Spain, S.L.; Knight, J.; Ellinghaus, E.; Stuart, P.E.; Capon, F.; Ding, J.; Li, Y.; Tejasvi, T.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; et al. Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility loci highlights the role of innate immunity. Nat Genet 2012, 44, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, R.L.; Bernard, J.J. Innate immune sensors stimulate inflammatory and immunosuppressive responses to UVB radiation. J Invest Dermatol 2014, 134, 1508–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Niu, J.; Shi, Y.; Ouyang, H.; Wu, Z.H. NF-κB-dependent microRNA-125b up-regulation promotes cell survival by targeting p38α upon ultraviolet radiation. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 33036–33047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilion, J.V.; Khanna, S.; Anasseri, S.; Laney, C.; Mayrovitz, H.N. Physiological, Pathological, and Circadian Factors Impacting Skin Hydration. Cureus 2022, 14, e27666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahigashi, K.; Kabashima, K.; Ikoma, A.; Verkman, A.S.; Miyachi, Y.; Hara-Chikuma, M. Upregulation of aquaporin-3 is involved in keratinocyte proliferation and epidermal hyperplasia. J Invest Dermatol 2011, 131, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Vilchez, T.; Segura-Fernandez-Nogueras, M.V.; Perez-Rodriguez, I.; Soler-Gongora, M.; Martinez-Lopez, A.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, A.; Molina-Leyva, A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Skin Barrier Function in Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis: Transepidermal Water Loss and Temperature as Useful Tools to Assess Disease Severity. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.E.; Bollag, R.J.; Fussell, N.; By, C.; Sheehan, D.J.; Bollag, W.B. Abnormal aquaporin-3 protein expression in hyperproliferative skin disorders. Arch Dermatol Res 2011, 303, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denda, M.; Sato, J.; Tsuchiya, T.; Elias, P.M.; Feingold, K.R. Low humidity stimulates epidermal DNA synthesis and amplifies the hyperproliferative response to barrier disruption: implication for seasonal exacerbations of inflammatory dermatoses. J Invest Dermatol 1998, 111, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravello, B.; Ferri, A. Relationships between skin properties and environmental parameters. Skin Res Technol 2008, 14, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Kirk, B.; Polinski, J.M.; Yue, X.; Kilpatrick, R.D.; Gelfand, J.M. Impact of Season and Other Factors on Initiation, Discontinuation, and Switching of Systemic Drug Therapy in Patients with Psoriasis: A Retrospective Study. JID Innov 2023, 3, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.; Kashetsky, N.; Feschuk, A.; Maibach, H.I. Transepidermal water loss (TEWL): Environment and pollution-A systematic review. Skin Health Dis 2022, 2, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, E.R. The influence of climate change on skin cancer incidence - A review of the evidence. Int J Womens Dermatol 2021, 7, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, E.R.; Mo, J.; Goodman, R.S. The dermatological manifestations of extreme weather events: A comprehensive review of skin disease and vulnerability. The Journal of Climate Change and Health 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolhasani, R.; Araghi, F.; Tabary, M.; Aryannejad, A.; Mashinchi, B.; Robati, R.M. The impact of air pollution on skin and related disorders: A comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther 2021, 34, e14840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, M.; Colonna, M. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor: Linking environment to immunity. Semin Immunol 2015, 27, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Voorhis, M.; Knopp, S.; Julliard, W.; Fechner, J.H.; Zhang, X.; Schauer, J.J.; Mezrich, J.D. Exposure to atmospheric particulate matter enhances Th17 polarization through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. PLoS One 2013, 8, e82545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afaq, F.; Zaid, M.A.; Pelle, E.; Khan, N.; Syed, D.N.; Matsui, M.S.; Maes, D.; Mukhtar, H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor is an ozone sensor in human skin. J Invest Dermatol 2009, 129, 2396–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, F.J.; Basso, A.S.; Iglesias, A.H.; Korn, T.; Farez, M.F.; Bettelli, E.; Caccamo, M.; Oukka, M.; Weiner, H.L. Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 2008, 453, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, S.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Vender, R.; Torres, T. Tapinarof for the treatment of psoriasis. Dermatol Ther 2022, 35, e15931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, R.; Silverberg, J.I. Environmental risk factors and their role in the management of atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2017, 13, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siudek, P. Chemical composition and source apportionment of ambient PM2.5 in a coastal urban area, Northern Poland. Chemosphere 2024, 356, 141850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayinde, B.O.; Musa, M.R.; Ayinde, A.O. Application of machine learning models and landsat 8 data for estimating seasonal pm 2.5 concentrations. Environ Anal Health Toxicol 2024, 39, e2024011–2024010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinato, F.; Adami, G.; Vaienti, S.; Benini, C.; Gatti, D.; Idolazzi, L.; Fassio, A.; Rossini, M.; Girolomoni, G.; Gisondi, P. Association Between Short-term Exposure to Environmental Air Pollution and Psoriasis Flare. JAMA Dermatol 2022, 158, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, F.Y.; Chen, W.L.; Kao, T.W.; Chang, Y.W.; Huang, C.F. Exploring the link between cadmium and psoriasis in a nationally representative sample. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Environmental Agency. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en (accessed on 10th of March 2024).

- Armstrong, A.W.; Harskamp, C.T.; Dhillon, J.S.; Armstrong, E.J. Psoriasis and smoking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 2014, 170, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.W.; Armstrong, E.J.; Fuller, E.N.; Sockolov, M.E.; Voyles, S.V. Smoking and pathogenesis of psoriasis: a review of oxidative, inflammatory and genetic mechanisms. Br J Dermatol 2011, 165, 1162–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, M.; Yuan, X.; Song, L.Z.; Roberts, L.; Zarinkamar, N.; Seryshev, A.; Zhang, Y.; Hilsenbeck, S.; Chang, S.H.; Dong, C.; et al. Cigarette smoke induction of osteopontin (SPP1) mediates T(H)17 inflammation in human and experimental emphysema. Sci Transl Med 2012, 4, 117ra119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mleczko, M.; Gerkowicz, A.; Krasowska, D. Chronic Inflammation as the Underlying Mechanism of the Development of Lung Diseases in Psoriasis: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungprasert, P.; Srivali, N.; Thongprayoon, C. Association between psoriasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dermatolog Treat 2016, 27, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinch Hyttel, C.; Ghazanfar, M.N.; Zhang, D.G.; Thomsen, S.F.; Ali, Z. The association between psoriasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital J Dermatol Venerol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ke, R.; Shi, W.; Yan, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Chai, L.; Li, M. Association between psoriasis and asthma risk: A meta-analysis. Allergy Asthma Proc 2018, 39, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ger, T.Y.; Fu, Y.; Chi, C.C. Bidirectional Association Between Psoriasis and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purzycka-Bohdan, D.; Kisielnicka, A.; Zabłotna, M.; Nedoszytko, B.; Nowicki, R.J.; Reich, A.; Samotij, D.; Szczęch, J.; Krasowska, D.; Bartosińska, J.; et al. Chronic Plaque Psoriasis in Poland: Disease Severity, Prevalence of Comorbidities, and Quality of Life. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Wu, R.; Kong, Y.; Zhao, M.; Su, Y. Impact of smoking on psoriasis risk and treatment efficacy: a meta-analysis. J Int Med Res 2020, 48, 300060520964024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.; Xiao, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Z. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Paradoxical Psoriasis or Psoriasiform Lesions in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients Receiving Anti-TNF Therapy: Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 847160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.Q.; Qureshi, A.A.; Schernhammer, E.S.; Han, J. Rotating night-shift work and risk of psoriasis in US women. J Invest Dermatol 2013, 133, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jing, D.; Su, J.; Huang, Z.; Liu, H.; Tao, J.; He, M.; Chen, X.; Shen, M.; Xiao, Y. Association of Night Shift Work With Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria and Effect Modification by Circadian Dysfunction Among Workers. Front Public Health 2021, 9, 751579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, K.H.; Takahashi, J.S. Circadian clock genes and the transcriptional architecture of the clock mechanism. J Mol Endocrinol 2019, 63, R93–R102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastings, M.H.; Maywood, E.S.; Brancaccio, M. Generation of circadian rhythms in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Nat Rev Neurosci 2018, 19, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Greenberg, E.N.; Karri, S.S.; Andersen, B. The circadian clock and diseases of the skin. FEBS Lett 2021, 595, 2413–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, J.S. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat Rev Genet 2017, 18, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koronowski, K.B.; Kinouchi, K.; Welz, P.S.; Smith, J.G.; Zinna, V.M.; Shi, J.; Samad, M.; Chen, S.; Magnan, C.N.; Kinchen, J.M.; et al. Defining the Independence of the Liver Circadian Clock. Cell 2019, 177, 1448–1462 e1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinturel, F.; Gos, P.; Petrenko, V.; Hagedorn, C.; Kreppel, F.; Storch, K.F.; Knutti, D.; Liani, A.; Weitz, C.; Emmenegger, Y.; et al. Circadian hepatocyte clocks keep synchrony in the absence of a master pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus or other extrahepatic clocks. Genes Dev 2021, 35, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarkson-Townsend, D.A.; Everson, T.M.; Deyssenroth, M.A.; Burt, A.A.; Hermetz, K.E.; Hao, K.; Chen, J.; Marsit, C.J. Maternal circadian disruption is associated with variation in placental DNA methylation. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0215745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemeth, V.; Horvath, S.; Kinyo, A.; Gyulai, R.; Lengyel, Z. Expression Patterns of Clock Gene mRNAs and Clock Proteins in Human Psoriatic Skin Samples. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plikus, M.V.; Van Spyk, E.N.; Pham, K.; Geyfman, M.; Kumar, V.; Takahashi, J.S.; Andersen, B. The circadian clock in skin: implications for adult stem cells, tissue regeneration, cancer, aging, and immunity. J Biol Rhythms 2015, 30, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, N.; Nakamura, Y.; Aoki, R.; Ishimaru, K.; Ogawa, H.; Okumura, K.; Shibata, S.; Shimada, S.; Nakao, A. Circadian Gene Clock Regulates Psoriasis-Like Skin Inflammation in Mice. J Invest Dermatol 2015, 135, 3001–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narasimamurthy, R.; Hatori, M.; Nayak, S.K.; Liu, F.; Panda, S.; Verma, I.M. Circadian clock protein cryptochrome regulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 12662–12667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Rollins, D.; Ruhn, K.A.; Stubblefield, J.J.; Green, C.B.; Kashiwada, M.; Rothman, P.B.; Takahashi, J.S.; Hooper, L.V. TH17 cell differentiation is regulated by the circadian clock. Science 2013, 342, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Gong, Y.; Cui, L.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, P.; Zhang, X.; et al. High-throughput transcriptome and pathogenesis analysis of clinical psoriasis. J Dermatol Sci 2020, 98, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Loo, C.S.; Zhao, X.; Solt, L.A.; Liang, Y.; Bapat, S.P.; Cho, H.; Kamenecka, T.M.; Leblanc, M.; Atkins, A.R.; et al. The nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha modulates Th17 cell-mediated autoimmune disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 18528–18536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirotsu, C.; Rydlewski, M.; Araujo, M.S.; Tufik, S.; Andersen, M.L. Sleep loss and cytokines levels in an experimental model of psoriasis. PLoS One 2012, 7, e51183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, E.N.; Marshall, M.E.; Jin, S.; Venkatesh, S.; Dragan, M.; Tsoi, L.C.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Nie, Q.; Takahashi, J.S.; Andersen, B. Circadian control of interferon-sensitive gene expression in murine skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 5761–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Németh, V.; Horváth, S.; Kinyó, Á.; Gyulai, R.; Lengyel, Z. Expression Patterns of Clock Gene mRNAs and Clock Proteins in Human Psoriatic Skin Samples. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaaslan, C.; Suzen, S. Antioxidant properties of melatonin and its potential action in diseases. Curr Top Med Chem 2015, 15, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, A.; Nakamura, Y. Time will tell about mast cells: Circadian control of mast cell activation. Allergol Int 2022, 71, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartha, L.B.; Chandrashekar, L.; Rajappa, M.; Menon, V.; Thappa, D.M.; Ananthanarayanan, P.H. Serum melatonin levels in psoriasis and associated depressive symptoms. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014, 52, e123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohid, H.; Aleem, D.; Jackson, C. Major Depression and Psoriasis: A Psychodermatological Phenomenon. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2016, 29, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scuderi, S.A.; Cucinotta, L.; Filippone, A.; Lanza, M.; Campolo, M.; Paterniti, I.; Esposito, E. Effect of Melatonin on Psoriatic Phenotype in Human Reconstructed Skin Model. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, S.; Bahakeem, H.; Alkhalifah, A.; Cavalie, M.; Boukari, F.; Montaudie, H.; Lacour, J.P.; Passeron, T. Topical corticosteroids application in the evening is more effective than in the morning in psoriasis: results of a prospective comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017, 31, e263–e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, R.; Iskandar, I.Y.K.; Kontopantelis, E.; Augustin, M.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Ashcroft, D.M.; Global Psoriasis, A. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ 2020, 369, m1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [CrossRef]

- Lecaros, C.; Dunstan, J.; Villena, F.; Ashcroft, D.M.; Parisi, R.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Hartel, S.; Maul, J.T.; De la Cruz, C. The incidence of psoriasis in Chile: an analysis of the National Waiting List Repository. Clin Exp Dermatol 2021, 46, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watad, A.; Azrielant, S.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Sharif, K.; David, P.; Katz, I.; Aljadeff, G.; Quaresma, M.; Tanay, G.; Adawi, M.; et al. Seasonality and autoimmune diseases: The contribution of the four seasons to the mosaic of autoimmunity. J Autoimmun 2017, 82, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adawi, M.; Damiani, G.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Bridgewood, C.; Pacifico, A.; Conic, R.R.Z.; Morrone, A.; Malagoli, P.; Pigatto, P.D.M.; Amital, H.; et al. The Impact of Intermittent Fasting (Ramadan Fasting) on Psoriatic Arthritis Disease Activity, Enthesitis, and Dactylitis: A Multicentre Study. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damiani, G.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Garbarino, S.; Chattu, V.K.; Shapiro, C.M.; Pacifico, A.; Malagoli, P.; Pigatto, P.D.M.; Conic, R.R.Z.; Tiodorovic, D.; et al. Psoriatic and psoriatic arthritis patients with and without jet-lag: does it matter for disease severity scores? Insights and implications from a pilot, prospective study. Chronobiol Int 2019, 36, 1733–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedi, T.R. Psoriasis in North India. Geographical variations. Dermatologica 1977, 155, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, L.D.A.R.; Nascimento, A.C.M.D.; Marque, C.D.; Miot, H.A. Seasonality of the hospitalizations at a dermatologic ward (2007-2017). Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia 2018, 93, 755–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, F.J.; Lada, G.; Hunter, H.J.A.; Bundy, C.; Henry, A.L.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Kleyn, C.E. Diurnal and seasonal variation in psoriasis symptoms. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021, 35, e45–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancox, J.G.; Sheridan, S.C.; Feldman, S.R.; Fleischer, A.B., Jr. Seasonal variation of dermatologic disease in the USA: a study of office visits from 1990 to 1998. Int J Dermatol 2004, 43, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellgren, L. Psoriasis. A statistical, clinical and laboratory investigation of 255 psoriatics and matched healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol 1964, 44, 191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.S.; Youn, J.I. Factors influencing psoriasis: an analysis based upon the extent of involvement and clinical type. J Dermatol 1998, 25, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, V.L.; Kimball, A.B. Seasonal variation of acne and psoriasis: A 3-year study using the Physician Global Assessment severity scale. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015, 73, 523–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvell, J.D.; Selig, D.J. Seasonal variations in dermatologic and dermatopathologic diagnoses: a retrospective 15-year analysis of dermatopathologic data. Int J Dermatol 2016, 55, 1115–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, K.; Kamijima, Y.; Sato, T.; Ooba, N.; Koide, D.; Iizuka, H.; Nakagawa, H. Epidemiology of psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a nationwide study using the Japanese national claims database. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Dan, Y.L.; Zhao, C.N.; Mao, Y.M.; Liu, L.N.; Pan, H.F. Seasonality and global public interest in psoriasis: an infodemiology study. Postgrad Med J 2020, 96, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowietz, U.; Dieckmann, T.; Gerdes, S.; Szymczak, S.; von Spreckelsen, R.; Korber, A. ActiPso: definition of activity types for psoriatic disease: A novel marker for an advanced disease classification. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021, 35, 2027–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Lu, W.; Jin, L.; Chen, M.; Zhu, W.; Kuang, Y. Seasonal Variation of Psoriasis and Its Impact in the Therapeutic Management: A Retrospective Study on Chinese Patients. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2021, 14, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.K.; Serup, J.; Alsing, K.K. Psoriasis and seasonal variation: A systematic review on reports from Northern and Central Europe-Little overall variation but distinctive subsets with improvement in summer or wintertime. Skin Res Technol 2022, 28, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Air quality in Europe 2022. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2022 (accessed on 10th March 2024).

- Theodoridis, X.; Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Stamouli, E.M.; Talimtzi, P.; Pagkalidou, E.; Zafiriou, E.; Haidich, A.B.; Bogdanos, D.P. Effectiveness of oral vitamin D supplementation in lessening disease severity among patients with psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition 2021, 82, 111024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, A.R.; Siegel, M.; Bagel, J.; Cordoro, K.M.; Garg, A.; Gottlieb, A.; Green, L.J.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Koo, J.; Lebwohl, M.; et al. Dietary Recommendations for Adults With Psoriasis or Psoriatic Arthritis From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: A Systematic Review. JAMA Dermatology 2018, 154, 934–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruano, J.; Velez, A.; Casas, E.; Rodriguez-Martin, A.; Salido, R.; Isla-Tejera, B.; Espejo-Alvarez, J.; Gomez, F.; Jimenez-Puya, R.; Moreno-Gimenez, J.C. Factors influencing seasonal patterns of relapse in anti-TNF psoriatic responders after temporary drug discontinuation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014, 28, 516–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedźwiedź, M.; Noweta, M.; Narbutt, J.; Owczarek, W.; Ciążyńska, M.; Czerwińska, A.; Krzyścin, J.; Lesiak, A.; Skibińska, M. Does the effectiveness of biological medications in the treatment for psoriasis depend on the moment of starting therapy? A preliminary study. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2024, 41, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane Guy, C.; Crawford, G. Psoriasis: a statistical study of two hundred and thirty-one cases. Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology 1937, 35, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomholt, G. Psoriasis on the Faroe Islands; a preliminary report. Acta Derm Venereol 1954, 34, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Kononen, M.; Torppa, J.; Lassus, A. An epidemiological survey of psoriasis in the greater Helsinki area. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1986, 124, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knopf, B.; Geyer, A.; Roth, H.; Barta, U. [The effect of endogenous and exogenous factors on psoriasis vulgaris. A clinical study]. Dermatol Monatsschr 1989, 175, 242–246. [Google Scholar]

- Kardeş, S. Seasonal variation in the internet searches for psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res 2019, 311, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Described polymorphism | Clinical features/implication |

|---|---|

|

HLA-B*27 HLA-B*39 HLA-B*38 HLA-B*08 |

Higher risk of PsA development. |

| HLA-B*08 | Asymmetric sacroiliitis, peripheral arthritis ankylosis, and increased joint damage. |

| HLA-B*27 | Symmetric sacroiliitis, dactylitis and enthesitis development. |

| HLA-C*06:02 | An earlier onset of PsV and a later onset of PsA. Photosensitive psoriasis. |

| CARD14 | Psoriasis and/or features of PRP and GPP. Photosensitive psoriasis. |

|

FTO CALCR AC003006.7 |

PsV associated with obesity. |

| Light type | Abbreviation | Wavelength [nm] |

|---|---|---|

| UV-radiation | UV-R | 100-400 |

| UV-C | 100-280 | |

| UV-B | 280-315 | |

| UV-A | 315-400 | |

| UV-A2 | 315-340 | |

| UV-A1 | 340-400 | |

| visible light | VIS | 400-780 |

| infrared radiation | IR | 780-1000 |

| Author(s) | Year of publication | Study design | Region | Number of analysed PsV patients | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lane and Crawford [194] |

1937 | retrospective analysis of clinic visits | USA | 231 | Seasonal pattern in 75% of patients. Deterioration of psoriasis in 14.3% of patients in summer, improvement in 60.2% in summer. |

|

Lomholt [195] |

1954 | personal interview by the investigator | Faroe Islands | 206 | Seasonal pattern of psoriasis in about 50% of cases. Patients with seasonal pattern observed deterioration in winter and spring (25% and 52% respectively) and improvement in summer (63%). |

|

Hellgren [180] |

1964 | analysis of inpatients with psoriasis | Sweden | 255 | Seasonal pattern of psoriasis in about 50%. Patients observed improvement in winter and summer (7.9% and 22.6% respectively). |

|

Bedi [176] |

1977 | analysis of outpatients with psoriasis | Northern India | 162 | No seasonal pattern in 54% patients. Twenty-five percent patients reported deterioration in winter and improvement in summer. Twelve percent patients reported improvement in winter and deterioration in summer. |

|

Könönen et al. [196] |

1986 | survey/questionnaires | Finland | 1 517 | Deterioration of psoriasis in 54% of patients in winter, 18% in spring and 2% in summer. |

|

Knopf et al. [197] |

1989 | survey/questionnaires | Germany | 390 | Deterioration of psoriasis in 37.4% of patients in winter, 42.3% in spring; improvement in 60.5% of patients in summer. |

|

Park and Youn [181] |

1998 | survey/questionnaires | South Korea | 870 | Deterioration in winter reported by 65% of patients and no seasonality or improvement reported by 35%. |

|

Hancox [179] |

2004 | retrospective analysis of office visits | USA | no data | No seasonality observed by using astronomical calendar. Significant differences observed by using meteorological calendar with majority of visits in spring. |

|

Kubota et al. [184] |

2015 | statistical analysis of the data in Japanese national database of health insurance claims (JNDB) | Japan | 429 679 | No seasonal pattern observed. |

|

Pascoe and Kimball [182] |

2015 | analysis of dermatologists’ billing sheets based on PGA scores | USA | 5 468 | The percentage of patients with clear/almost clear disease was highest in summer at 20.4% and the lowest in winter at 15.3%. Number of patients with moderate/severe psoriasis was highest in winter at 40.5% and the lowest in summer at 34.1%. |

|

Harvell and Selig [183] |

2016 | retrospective analysis of dermatopathological data | USA | 223 | No seasonal pattern in histopathological diagnosis observed. |

|

Brito [177] |

2018 | retrospective analysis of ward admissions | Brazil | 155 | Twenty-nine percent of admissions of patients with psoriasis in autumn, 27% in winter, 25% in spring and 19% in summer. |

|

Kardeş [198] |

2019 | analysis of Google Trends queries for psoriasis | United States; United Kingdom; Canada; Ireland; Australia; New Zealand | no data | Statistically significant seasonal pattern of searches for psoriasis with peaks in winter/early spring and troughs in summer/early fall. Peaks in late winter/early spring and troughs in late summer/early fall presented approximately with 6-month difference between hemispheres. |

|

Wu [185] |

2020 | analysis of Google Trends queries for psoriasis | Australia, New Zealand, USA, Canada, United Kingdom, Ireland | ND | Significant seasonal pattern for psoriasis, with peaks in late winter/early spring and troughs in late summer/early autumn. |

|

Ferguson et al. [178] |

2020 | cross-sectional online survey | world-wide | 186 | Seventy-seven percent of respondents reported seasonal pattern of psoriasis exacerbation. Deterioration of psoriasis reported by 67.1% of patients in winter, 23.8% in summer, 7% in spring and 2.1% in autumn. |

|

Jensen [188] |

2021 | systematic review | Northern and Central Europe | 12 900 | Thirteen publications: nine published before 1958 and including four reported above (Lomholt, Hellgren, Könönen et al, Knopf et al.). No seasonality in 50% of patients. Approximately 30% improved in summer, and 20% performed better in winter. |

|

Purzycka-Bohdan et al. [142] |

2022 | national survey study | Poland | 1080 | Seasonal changes were reported by 45.09% to have a considerable impact on the psoriasis disease course. |

|

Liang et al. [118] |

2023 | retrospective ecological study of individuals with psoriasis identified in the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart. | USA | 74 960 | The initiation of the treatment peaked in spring months, followed by the summer, fall and winter. Discontinuation of biologic drugs peaked in summer, and switching of biologics was highest in spring. Season was associated with initiation, discontinuation, and switching, although seasonality pattern is less clear for nonbiologic systemic drugs. |

|

Niedźwiedź et al. [193] |

2024 | retrospective analysis of patients treated with biologics depend on starting point of the therapy | Poland | 62 | Seasonality appeared in the effectiveness of IL12/23 and IL17 inhibitors therapy in moderate to severe psoriasis with better results obtained within first months of treatment in patients starting therapy in the warm period of the year (May-September). No seasonality was observed in patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).