Submitted:

14 August 2024

Posted:

15 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Features of the Device AEROK

2.2. Study Site

2.3. Microbial Sampling

2.3.1. Active Sampling

2.3.2. Passive Sampling

2.3.3. Cultural Conditions

2.3.4. Microbial Monitoring Plan

2.4. Particle Sampling

2.4.1. Particles Sampling Plan

2.5. Aerobiological Sampling of Pollen and Fungal Spores

2.5.1. Sampling Points

2.5.2. Pollen and Fungal Spores Sampling Plan

2.6. Measurement of Temperature, Relative Humidity and CO2 Concentration

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Microbial Air Sampling

3.1.1. Bacteria

3.1.2. Fungi

3.1.3. Door Openings

3.2. Particles

3.3. Pollen and Fungal Spores

3.4. Monitoring of Microclimatic Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mbareche, H.; Morawska, L.; Duchaine, C. On the Interpretation of Bioaerosol Exposure Measurements and Impacts on Health. J Air Waste Manage Assoc 2019, 69, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raaschou-Nielsen, O.; Andersen, Z.J.; Beelen, R.; Samoli, E.; Stafoggia, M.; Weinmayr, G.; Hoffmann, B.; Fischer, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Brunekreef, B.; et al. Air Pollution and Lung Cancer Incidence in 17 European Cohorts: Prospective Analyses from the European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects (ESCAPE). Lancet Oncol 2013, 14, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddrell, A.E.; Thomas, R.J. Aerobiology: Experimental Considerations, Observations, and Future Tools. Appl Environ Microbiol 2017, 83, e00809-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cincinelli, A.; Martellini, T. Indoor Air Quality and Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Singh, A.B.; Singh, R. Comprehensive Health Risk Assessment of Microbial Indoor Air Quality in Microenvironments. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0264226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedeño Laurent, J.G.; Macnaughton, P.; Jones, E.; Young, A.S.; Bliss, M.; Flanigan, S.; Vallarino, J.; Chen, L.J.; Cao, X.; Allen, J.G. Associations between Acute Exposures to PM2.5and Carbon Dioxide Indoors and Cognitive Function in Office Workers: A Multicountry Longitudinal Prospective Observational Study. Environ Res Letters 2021, 16, 094047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buters, J.; Prank, M.; Sofiev, M.; Pusch, G.; Albertini, R.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Antunes, C.; Behrendt, H.; Berger, U.; Brandao, R.; et al. Variation of the Group 5 Grass Pollen Allergen Content of Airborne Pollen in Relation to Geographic Location and Time in Season the HIALINE Working Group. J. Allergy Clin Immunology 2015, 136, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridolo, E.; Albertini, R.; Giordano, D.; Soliani, L.; Usberti, I.; Dall’Aglio, P.P. Airborne Pollen Concentrations and the Incidence of Allergic Asthma and Rhinoconjunctivitis in Northern Italy from 1992 to 2003. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2007, 142, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego Alonso, S.F.; Molina, A. Behavior of the Cultivable Airborne Mycobiota in Air-Conditioned Environments of Three Havanan Archives, Cuba. J. Atmos Sc Res 2020, 3, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquarella, C.; Barchitta, M.; D’Alessandro, D.; Cristina, M.L.; Mura, I.; Nobile, M.; Auxilia, F.; Agodi, A.; Collaborators. Heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system, microbial air contamination and surgical site infection in hip and knee arthroplasties: the GISIO-SItI Ischia study. Ann Ig 2018, 30, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, H.; Anand, P.; Garg, K.; Bhagat, N.; Varmani, SG.; Bansal, T.; McBain, AJ.; Marwah, RG. A comprehensive review of microbial contamination in the indoor environment: sources, sampling, health risks, and mitigation strategies. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1285393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadonna, L.; Briancesco, R.; Coccia, A.M.; Meloni, P.; La Rosa, G.; Moscato, U. Microbial Air Quality in Healthcare Facilities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 6226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessa, R.; Di Pietro, M.; Schiavoni, G.; Santino, I.; Altieri, A.; Pinelli, S.; Del Piano, M. Microbiological Indoor Air Quality in Healthy Buildings. New Microbiologica 2002, 25, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zoni, R.; Capobianco, E.; Viani, I.; Colucci, M.E.; Mezzetta, S.; Affanni, P.; Veronesi, L.; Di Fonzo, D.; Albertini, R.; Pasquarella, C. Fungal Contamination in a University Building. Acta Biomedica 2020, 91, 150–153. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Indoor Air Quality Research: Report on a WHO Meeting, Stockholm, 27-31 August 1984.; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, 1986; ISBN 9289012692.

- Berglund, B.; Lindvall, T. Sensory reactions to sick buildings. Environ Int 1986, 12, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlich, C.A.; Sparer, J.; Cullen, M.R. Sick-Building Syndrome. Lancet 1997, 349, 1013–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ou, C.; Magana-Arachchi, D.; Vithanage, M.; Vanka, K.S.; Palanisami, T.; Masakorala, K.; Wijesekara, H.; Yan, Y.; Bolan, N.; et al. Indoor Particulate Matter in Urban Households: Sources, Pathways, Characteristics, Health Effects, and Exposure Mitigation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 11055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, J.P.S. Can We Use Indoor Fungi as Bioindicators of Indoor Air Quality? Historical Perspectives and Open Questions. Sci Total Environ 2010, 408, 4285–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhui, K.; Newbury, J.B.; Latham, R.M.; Ucci, M.; Nasir, Z.A.; Turner, B.; O’Leary, C.; Fisher, H.L.; Marczylo, E.; Douglas, P.; Stansfeld, S.; Jackson, S.K.; Tyrrel, S.; Rzhetsky, A.; Kinnersley, R.; Kumar, P.; Duchaine, C.; Coulon, F. Air quality and mental health: evidence, challenges and future directions. BJPsych Open 2023, 5, e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.-J.; Nam, I.-S.; Yun, H.; Kim, J.; Yang, J.; Sohn, J.-R. Characterization of Indoor Air Quality and Efficiency of Air Purifier in Childcare Centers, Korea. Build Environ 2014, 82, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tran, V.; Park, D.; Lee, Y.C. Indoor Air Pollution, Related Human Diseases, and Recent Trends in the Control and Improvement of Indoor Air Quality. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNI 11425:2011. Impianto di ventilazione e condizionamento a contaminazione controllata (VCCC) per il blocco operatorio - Progettazione, installazione, messa in marcia, qualifica, gestione e manutenzione. Milano: Ente Nazionale Italiano di Unificazione 2011.

- Wu, J.; Alipouri, Y.; Luo, H.; Zhong, L. Ultraviolet Photocatalytic Oxidation Technology for Indoor Volatile Organic Compound Removal: A Critical Review with Particular Focus on Byproduct Formation and Modeling. J Hazard Mater 2022, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brągoszewska, E.; Biedroń, I. Efficiency of Air Purifiers at Removing Air Pollutants in Educational Facilities: A Preliminary Study. Front Environ Sci 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, F.J.; Fussell, J.C. Improving Indoor Air Quality, Health and Performance within Environments Where People Live, Travel, Learn and Work. Atmos Environ 2019, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.W.; Ma, W.L. Photocatalytic Oxidation Technology for Indoor Air Pollutants Elimination: A Review. Chemosphere 2021, 280, 130667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragoszewska, E.; Bogacka, M.; Pikoń, K. Efficiency and Eco-Costs of Air Purifiers in Terms of Improving Microbiological Indoor Air Quality in Dwellings-A Case Study. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombini, M.; Schreiber, L.; Albertini, R.; Alessi, E.M.; Attinà, P.; Bianco, A.; Cascone, E.; Colucci, M.E.; Cortecchia, F.; De Caprio, V.; et al. Solar Ultraviolet Light Collector for Germicidal Irradiation on the Moon. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 8326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinshpun, S.A.; Adhikari, A.; Honda, T.; Kim, K.Y.; Toivola, M.; Rao, K.S.R.; Reponen, T. Control of Aerosol Contaminants in Indoor Air: Combining the Particle Concentration Reduction with Microbial Inactivation. Environ Sci Technol 2007, 41, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otter, J.A.; Clark, L.; Taylor, G.; Hussein, A. Comparative evaluation of stand-alone HEPA-based air decontamination systems. Infection, Disease & Health 2023, 28, 246–248. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, W.D.; Bennett, A.; Speight, S.; Parks, S. Determining the Performance of a Commercial Air Purification System for Reducing Airborne Contamination Using Model Micro-Organisms: A New Test Methodology. J Hosp Infection 2005, 61, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhde, E.; Salthammer, T.; Wientzek, S.; Springorum, A.; Schulz, J. Effectiveness of Air-Purifying Devices and Measures to Reduce the Exposure to Bioaerosols in School Classrooms. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e13087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polidori, A.; Fine, P.M.; White, V.; Kwon, P.S. Pilot Study of High-Performance Air Filtration for Classroom Applications. Indoor Air 2013, 23, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heredia-Rodríguez, M.; Álvarez-Fuente, E.; Bustamante-Munguira, J.; Poves-Alvarez, R.; Fierro, I.; Gómez-Sánchez, E.; Gómez-Pesquera, E.; Lorenzo-López, M.; Eiros, J.M.; Álvarez, F.J.; et al. Impact of an Ultraviolet Air Sterilizer on Cardiac Surgery Patients, a Randomized Clinical Trial. Med Clin 2018, 151, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterman, S.; Du, L.; Mentz, G.; Mukherjee, B.; Parker, E.; Godwin, C.; Chin, J.Y.; O’Toole, A.; Robins, T.; Rowe, Z.; et al. Particulate Matter Concentrations in Residences: An Intervention Study Evaluating Stand-Alone Filters and Air Conditioners. Indoor Air 2012, 22, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.T.; Phillips, K.M.; Speth, M.M.; Besser, G.; Mueller, C.A.; Sedaghat, A.R. Portable HEPA Purifiers to Eliminate Airborne SARS-CoV-2: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngology - Head Neck Surg 2022, 166, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riederer, A.M.; Krenz, J.E.; Tchong-French, M.I.; Torres, E.; Perez, A.; Younglove, L.R.; Jansen, K.L.; Hardie, D.C.; Farquhar, S.A.; Sampson, P.D.; et al. Effectiveness of Portable HEPA Air Cleaners on Reducing Indoor Endotoxin, PM10, and Coarse Particulate Matter in an Agricultural Cohort of Children with Asthma: A Randomized Intervention Trial. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 1926–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medical Advisory Secretariat. Air cleaning technologies: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2005, 5, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kompatscher, K.; van der Vossen, J.M.B.M.; van Heumen, S.P.M.; Traversari, A.A.L. Scoping Review on the Efficacy of Filter and Germicidal Technologies for Capture and Inactivation of Micro-Organisms and Viruses. J Hospital Infec 2023, 142, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.G.; Ibrahim, A.M. Indoor Air Changes and Potential Implications for SARS-CoV-2 Transmission. JAMA 2021, 325, 2112–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardell, E.A.; Nathavitharana, R.R. Airborne Spread of SARS-CoV-2 and a Potential Role for Air Disinfection. JAMA 2020, 324, 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuit, M.; Ratnesar-Shumate, S.; Yolitz, J.; Williams, G.; Weaver, W.; Green, B.; Miller, D.; Krause, M.; Beck, K.; Wood, S.; et al. Airborne SARS-CoV-2 Is Rapidly Inactivated by Simulated Sunlight. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 222, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsley, W.G.; Derk, R.C.; Coyle, J.P.; Martin, S.B.; Mead, K.R.; Blachere, F.M.; Beezhold, D.H.; Brooks, J.T.; Boots, T.; Noti, J.D. Efficacy of Portable Air Cleaners and Masking for Reducing Indoor Exposure to Simulated Exhaled SARS-CoV-2 Aerosols — United States, 2021. MMWR 2021, 70, 972–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, A.A.; Zuñiga, J.M. The use of copper to help prevent transmission of SARS-coronavirus and influenza viruses. A general review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2020, 98, 115176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INAIL. Il Monitoraggio Microbiologico negli Ambienti di Lavoro - Campionamento e Analisi; 2010.

- International Organization for Standardization ISO 14698-1. Cleanrooms and Associated Controlled Environments — Biocontamination Control — Part 1: General Principles and Methods 2003.

- EN 17141. Camere Bianche Ed Ambienti Controllati Associati - Controllo Della Biocontaminazione. 2021.

- CDC Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities; NO:RR-10. 2003. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/environmental/index.html.

- Pitzurra, M.; Savino, A.; Pasquarella, C. Il monitoraggio ambientale microbiologico (MAM). Ann Ig 1997, 9, 439–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pasquarella, C.; Pitzurra, O.; Savino, A. The Index of Microbial Air Contamination. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2000, 46, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquarella, C.; Albertini, R.; Dall’Aglio, P.; Saccani, E.; Sansebastiano, G.E.; Signorelli, C. Air microbial sampling: the state of the art. Ig Sanita Pubbl 2008, 64, 79–120. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization ISO 21501-4:2018. Determination of Particle Size Distribution -- Single Particle Light Interaction Methods -- Part 4: Light Scattering Airborne Particle Counter for Clean Spaces.

- International Organization for Standardization SO 14644-1:2015. Cleanrooms and associated controlled environments - Part 1: Classification of air cleanliness by particle.

- International Organization for Standardization ISO 14644-2:2015. Cleanrooms and associated controlled environments - Part 2: Monitoring to provide evidence of cleanroom performance related to air cleanliness by particle concentration.

- ISO 16868:2019. Ambient air - Sampling and analysis of airborne pollen grains and fungal spores for networks related to allergy - Volumetric Hirst method.

- Pisharodi, M. Portable and Air Conditioner-Based Bio-Protection Devices to Prevent Airborne Infections in Acute and Long-Term Healthcare Facilities, Public Gathering Places, Public Transportation, and Similar Entities. Cureus 2024, 11, e55950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banholzer, N.; Jent, P.; Bittel, P.; Zürcher, K.; Furrer, L.; Bertschinger, S.; Weingartner, E.; Ramette, A.; Egger, M.; Hascher, T.; Fenner, L. Air cleaners and respiratory infections in schools: A modeling study using epidemiological, environmental, and molecular data. Open Forum Infect Dis 2024, 21, ofae169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmonsmith, J.; Ducci, A.; Balachandran, R.; Guo, L.; Torii, R.; Houlihan, C.; Epstein, R.; Rubin, J.; Tiwari, MK.; Lovat, LB. Use of portable air purifiers to reduce aerosols in hospital settings and cut down the clinical backlog. Epidemiol Infect 2023, 18, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimifakhar, A.; Poursadegh, M.; Hu, Y.; Yuill, D.P.; Luo, Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis of field studies of portable air cleaners: Performance, user behavior, and by-product emissions. Sci Total Environ 2024, 20, 168786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquarella, C.; Balocco, C.; Pasquariello, G.; Petrone, G.; Saccani, E.; Manotti, P.; Ugolotti, M.; Palla, F.; Maggi, O.; Albertini, R. A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Cultural Heritage Environments: Experience at the Palatina Library in Parma. Sci Total Environ 2015, 536, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquarella, C.; Vitali, P.; Saccani, E.; Manotti, P.; Boccuni, C.; Ugolotti, M.; Signorelli, C.; Mariotti, F.; Sansebastiano, G.E.; Albertini, R. Microbial Air Monitoring in Operating Theatres: Experience at the University Hospital of Parma. J Hospital Infec 2012, 81, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquarella, C.; Saccani, E.; Sansebastiano, G.E.; Ugolotti, M.; Pasquariello, G.; Albertini, R. Proposal for a Biological Environmental Monitoring Approach to Be Used in Libraries and Archives. Ann Agric Environ Med 2012, 19, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pasquarella, C.; Veronesi, L.; Napoli, C.; Castiglia, P.; Liguori, G.; Rizzetto, R.; Torre, I.; Righi, E.; Farruggia, P.; Tesauro, M.; Torregrossa, M.V.; Montagna, M.T.; Colucci, M.E.; Gallè, F.; Masia, M.D.; Strohmenger, L.; Bergomi, M.; Tinteri, C.; Panico, M.; Pennino, F.; Cannova, L.; Tanzi, M. SItI Working Group Hygiene in Dentistry. Microbial environmental contamination in Italian dental clinics: A multicenter study yielding recommendations for standardized sampling methods and threshold values. Sci Total Environ 2012, 420, 289–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buters, J.; Prank, M.; Sofiev, M.; Pusch, G.; Albertini, R.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Antunes, C.; Behrendt, H.; Berger, U.; Brandao, R.; Celenk, S.; Galan, C.; Grewling, Ł.; Jackowiak, B.; Kennedy, R.; Rantio-Lehtimäki, A.; Reese, G.; Sauliene, I.; Smith, M.; Thibaudon, M.; Weber, B.; Cecchi, L. Variation of the group 5 grass pollen allergen content of airborne pollen in relation to geographic location and time in season. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015, 136, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viani, I.; Colucci, M.E.; Pergreffi, M.; Rossi, D.; Veronesi, L.; Bizzarro, A.; Capobianco, E.; Affanni, P.; Zoni, R.; Saccani, E.; et al. Passive Air Sampling: The Use of the Index of Microbial Air Contamination. Acta Biomedica 2020, 91, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.; Peccia, J.; Ferro, A.R. Walking-Induced Particle Resuspension in Indoor Environments. Atmos Environ 2014, 89, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, A.; Byrne, M.A. The Influence of Human Physical Activity and Contaminated Clothing Type on Particle Resuspension. J Environ Radioact 2014, 127, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W.; Hejab, M. Particle and microbial airborne dispersion from people. Eur J Parent Pharm Sc 2007, 12, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

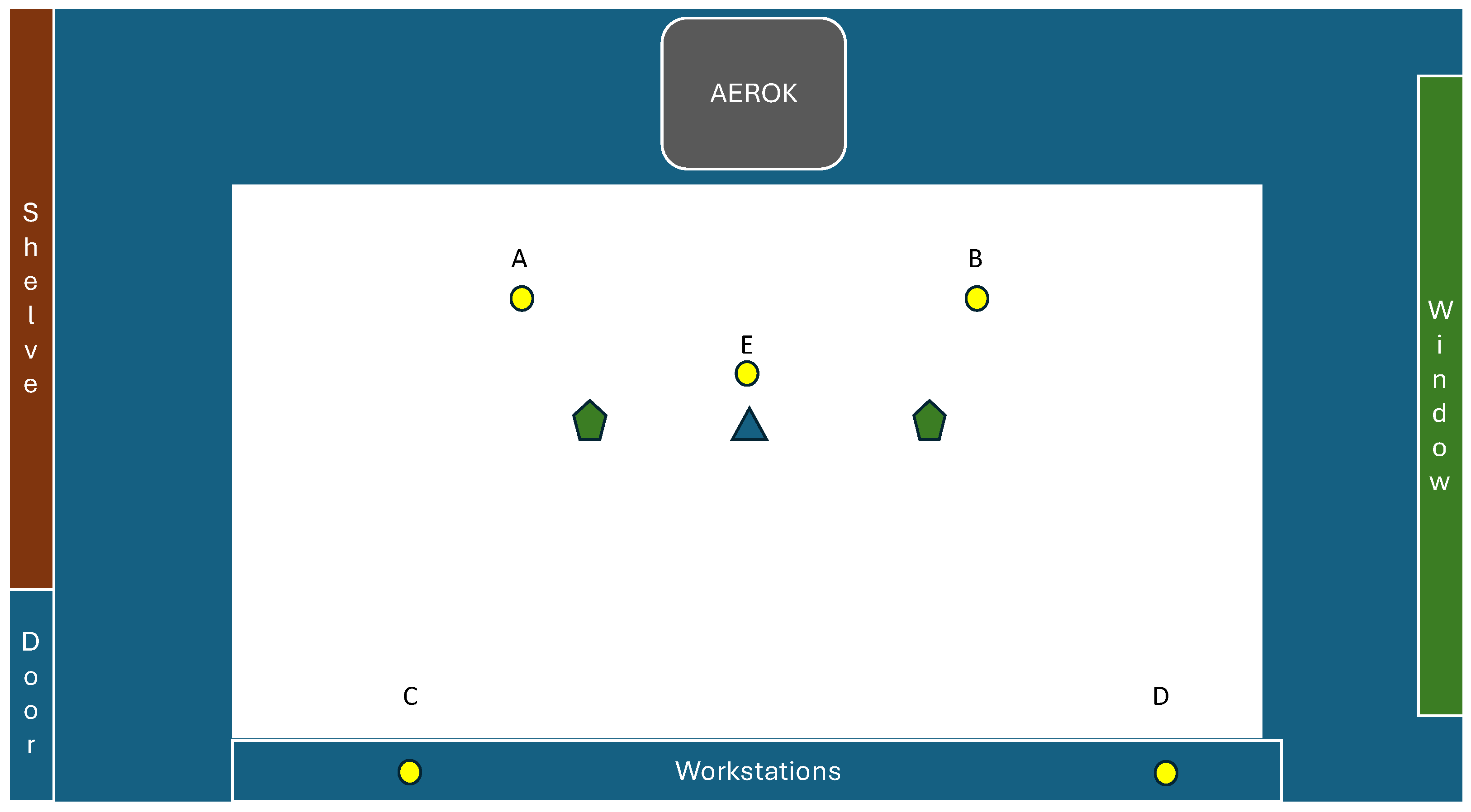

DUOSAS,

DUOSAS,  MD8),

MD8),  Petri dishes (passive sampling) and “AEROK” in the studied room.

Petri dishes (passive sampling) and “AEROK” in the studied room.

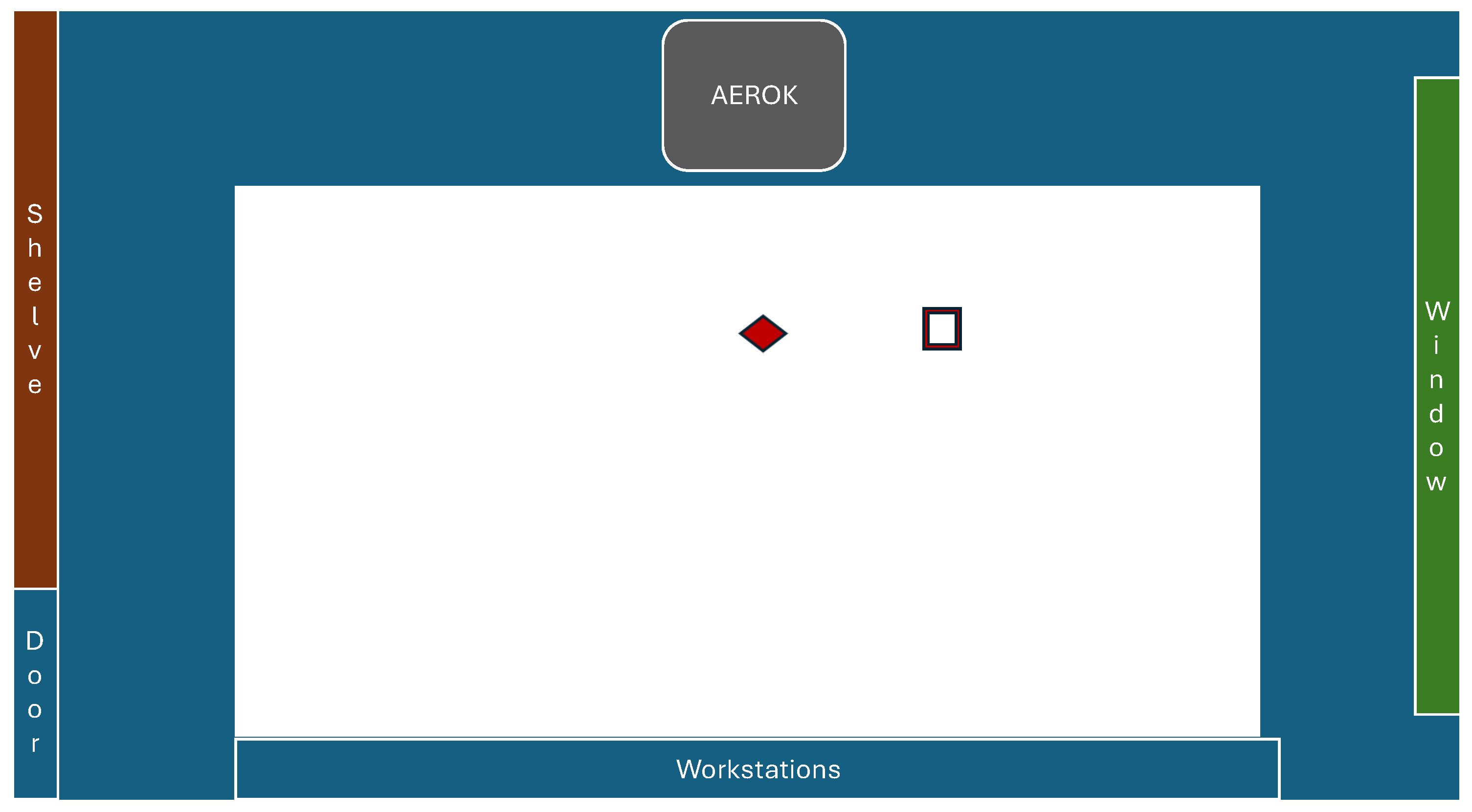

DUOSAS,

DUOSAS,  MD8),

MD8),  Petri dishes (passive sampling) and “AEROK” in the studied room.

Petri dishes (passive sampling) and “AEROK” in the studied room.

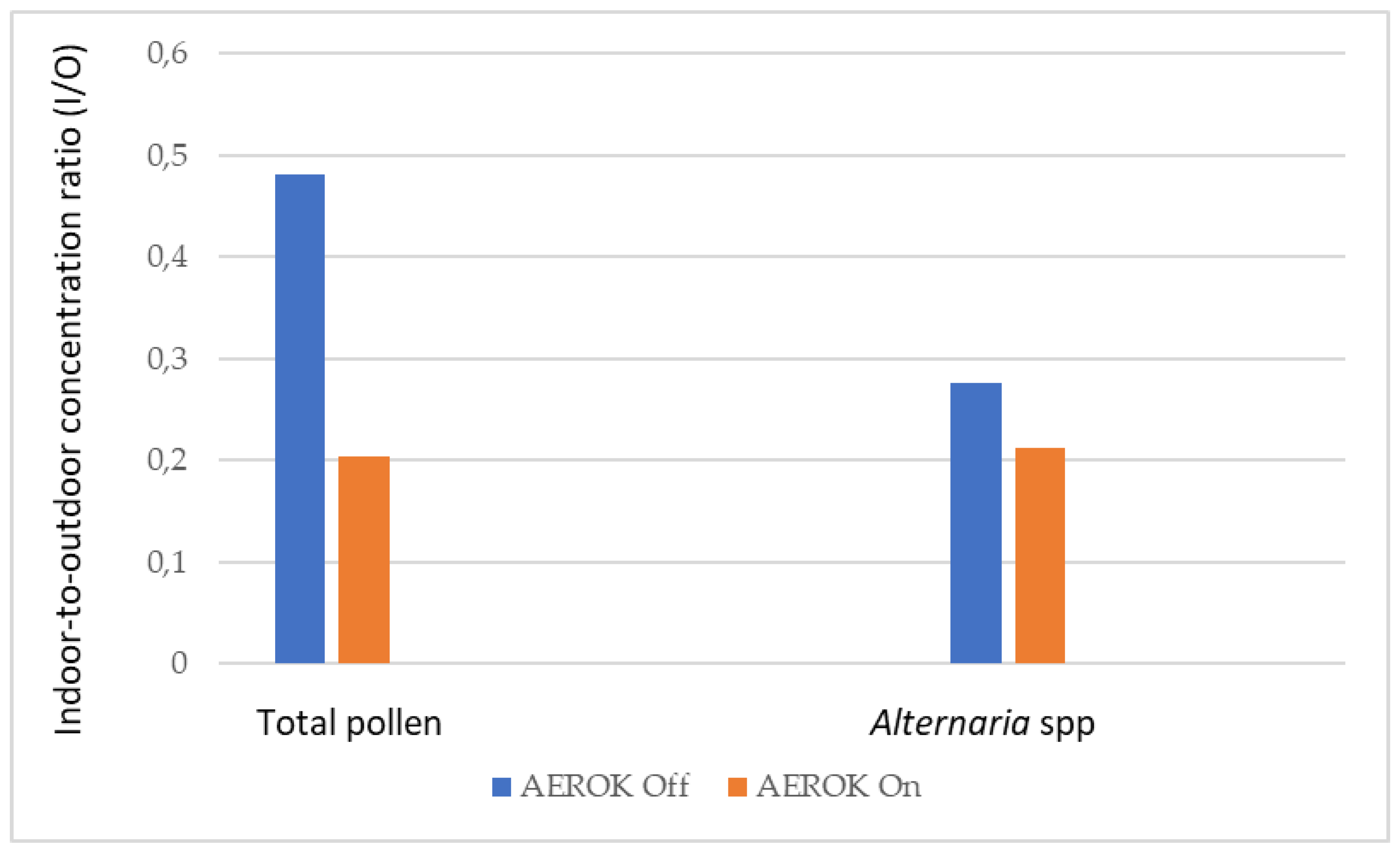

) and

pollen-trap (

) and

pollen-trap ( ) in the studied room.

) in the studied room.

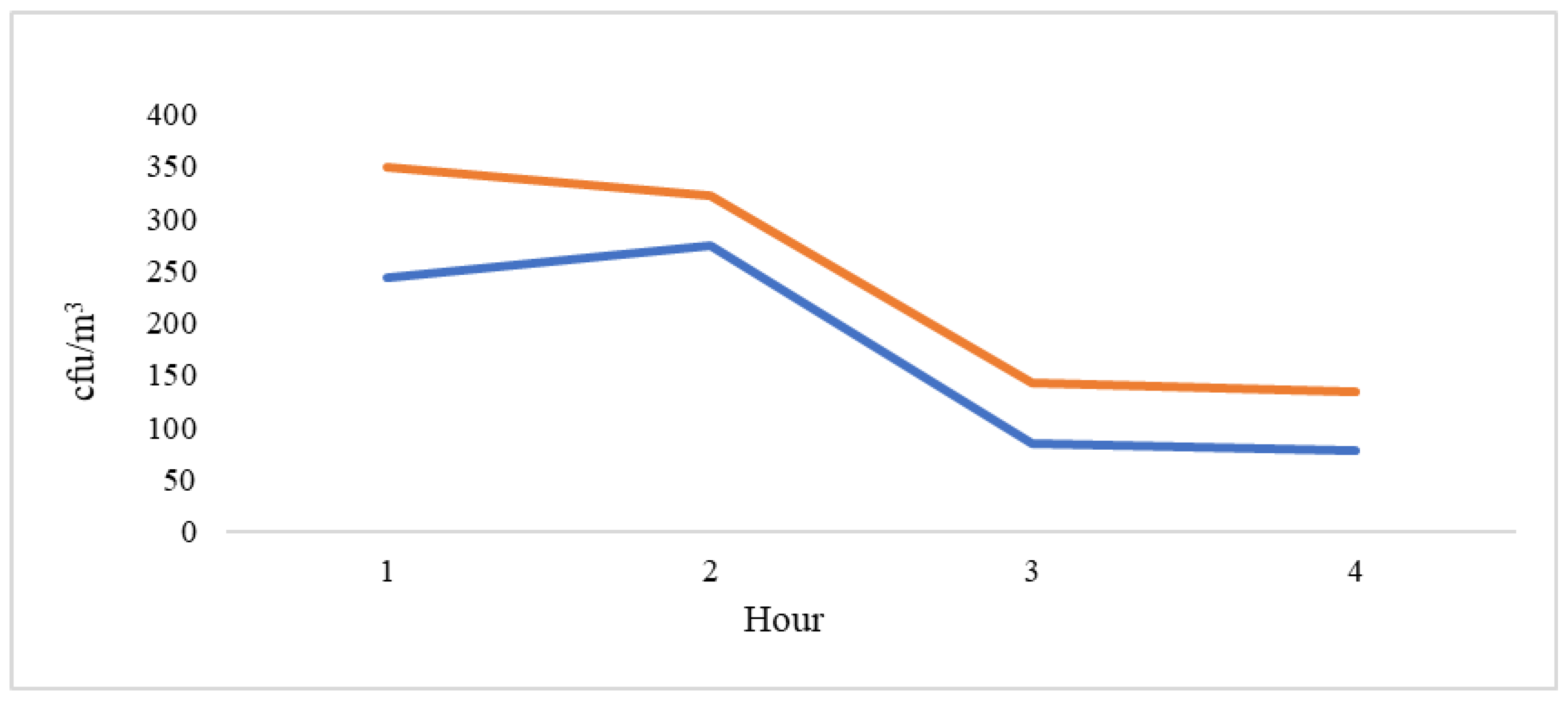

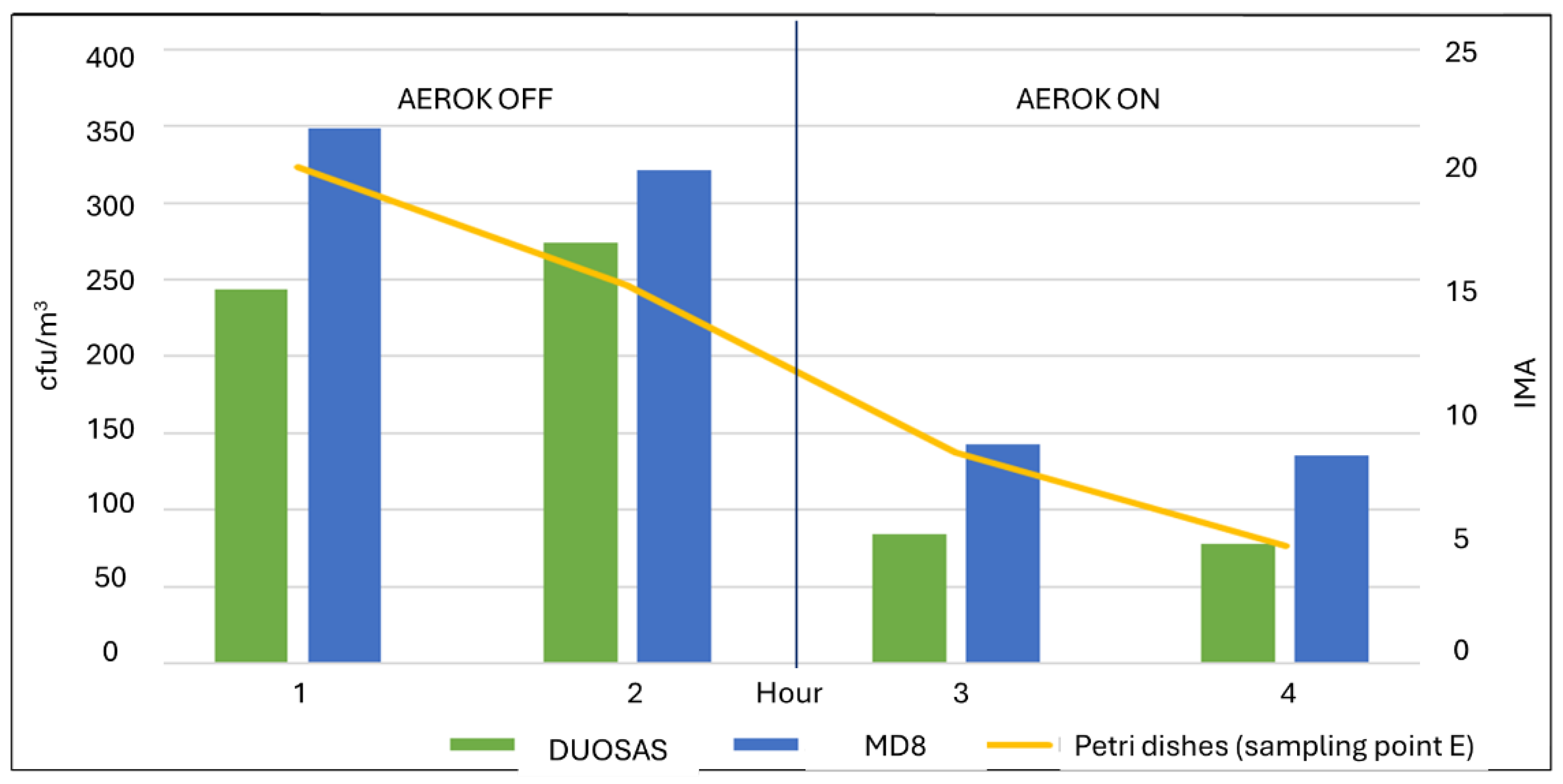

| Hour | Mean | Standard deviation | 95% Confidence interval | |

| Upper | Lower | |||

| 1 | 243.50 | 88.51 | 102.66 | 384.34 |

| 2 | 273.75 | 144.68 | 43.54 | 503.96 |

| 3 | 84.50 | 14.29 | 61,75 | 107.25 |

| 4 | 77.50 | 23.70 | 39.79 | 115.21 |

| Hour | Mean | Standard deviation | 95% Confidence interval | |

| Upper | Lower | |||

| 1 | 348.80 | 129.411 | 188.12 | 509.48 |

| 2 | 321.20 | 122.381 | 169.24 | 473.16 |

| 3 | 142.80 | 19.422 | 118.68 | 166.92 |

| 4 | 135.20 | 56.136 | 65.50 | 204.90 |

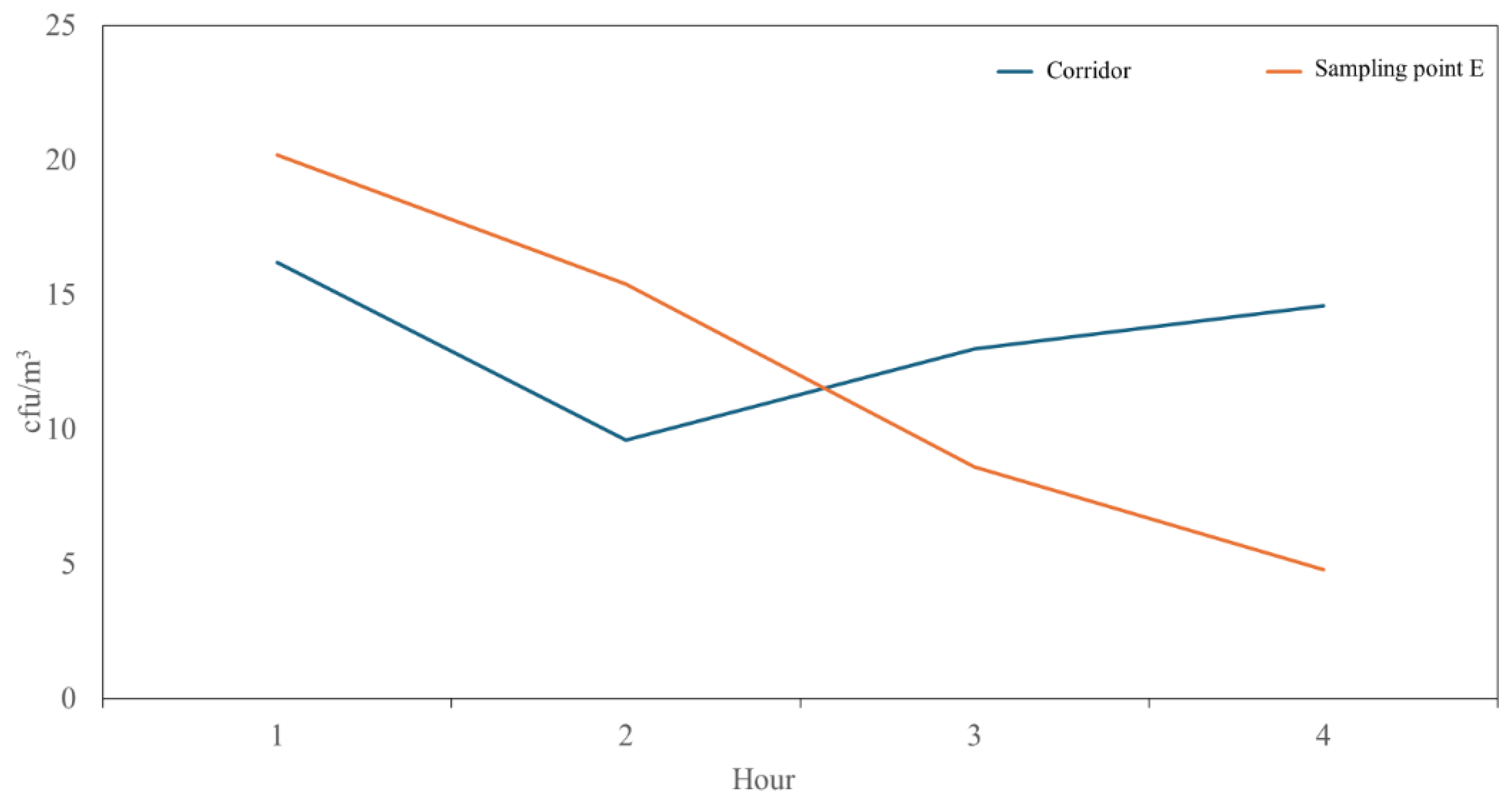

| Hour | Mean | Standard deviation |

95% Confidence interval | |

| Upper | Lower | |||

| 1 | 20.20 | 10.59 | 7.05 | 33.35 |

| 2 | 15.40 | 4.93 | 9.28 | 21.52 |

| 3 | 8.60 | 4.39 | 3.15 | 14.05 |

| 4 | 4.80 | 1.30 | 3.18 | 6.42 |

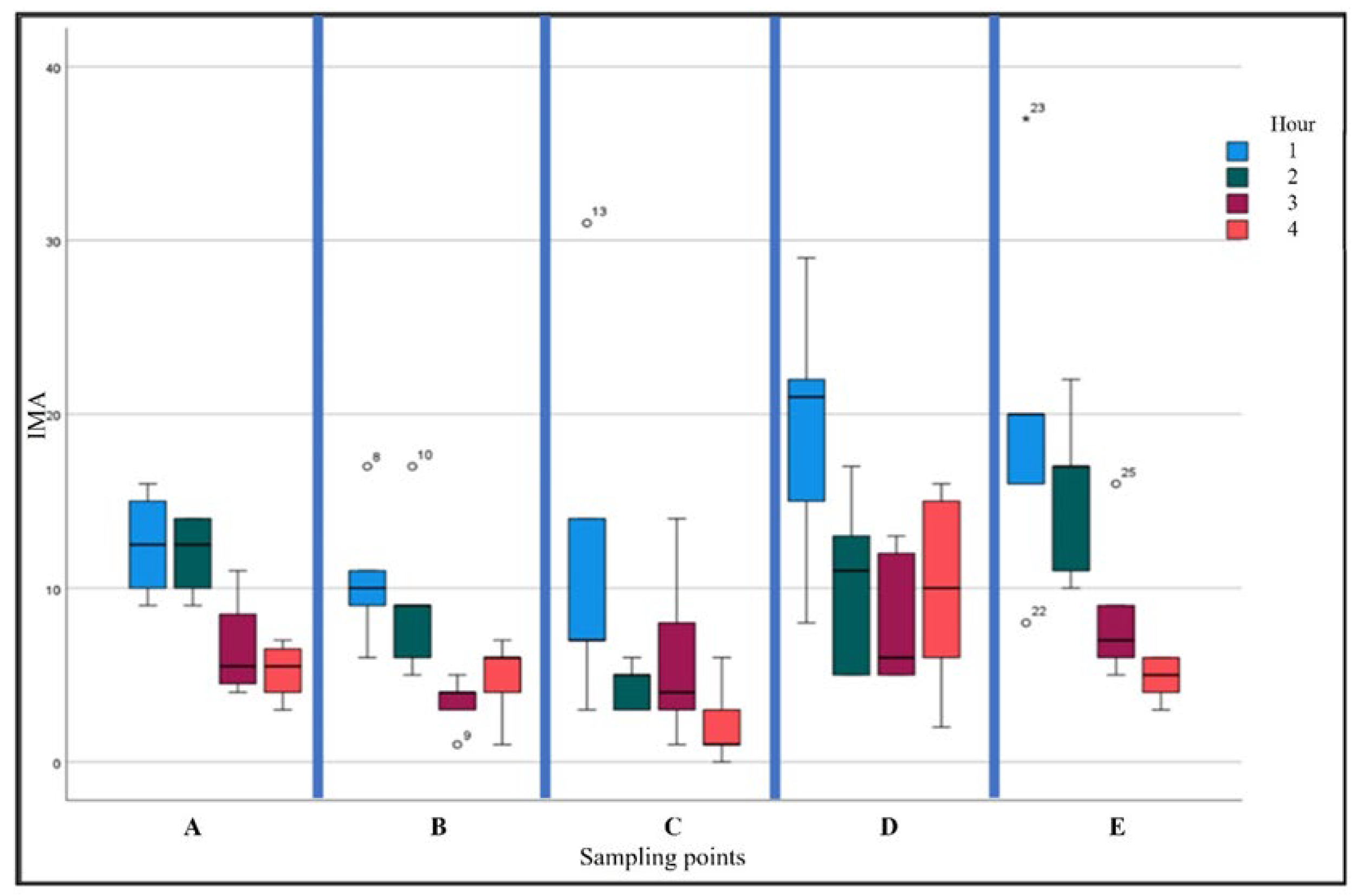

| Hour | Mean | Standard deviation |

95% Confidence interval | |

| Upper | Lower | |||

| 1 | 16.20 | 9.88 | 3.93 | 28.47 |

| 2 | 9.60 | 4.67 | 3.80 | 15.40 |

| 3 | 13.00 | 6.04 | 3.50 | 20.50 |

| 4 | 14.60 | 3.85 | 9.82 | 19.38 |

| Hour | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24.40 | 4.16 | 19 | 28 |

| 2 | 19.60 | 2.07 | 17 | 22 |

| 3 | 23.20 | 7.46 | 14 | 32 |

| 4 | 30.25 | 3.27 | 27 | 35 |

| AEROK |

Particle diameter (μm) ≥ |

Numbers of detections | Maximum | Minimum | Mean | St. deviation |

| Off | 0.5 | 200 | 3,805,710 | 2,892,967 | 3,285,666 | 234,369 |

| 1 | 691,139 | 195,696 | 512,461 | 133,723 | ||

| 2 | 265,530 | 61,854 | 139,215 | 35,317 | ||

| 5 | 36,282 | 550 | 2,687 | 5,622 | ||

| 10 | 19,450 | 0 | 496 | 1,887 | ||

| 25 | 570 | 0 | 18 | 70 | ||

| On | 0.5 | 200 | 5,430,398 | 431,967 | 2,076,980 | 859.814 |

| 1 | 1,574,021 | 108,754 | 480,738 | 243,308 | ||

| 2 | 595,518 | 31,621 | 130,090 | 87,937 | ||

| 5 | 39,166 | 170 | 1,860 | 5,284 | ||

| 10 | 10,852 | 0 | 343 | 1,371 | ||

| 25 | 750 | 0 | 16 | 78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).