1. Introduction

Glioma is a type of tumor that originates from neural stem cells or progenitor cells in the central nervous system, representing a common category among primary central nervous system tumors, accounting for approximately 80% of all primary malignant brain tumors[

1] . According to the 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) classification update, the categorization of gliomas is now based on the histological and molecular biomarker characteristics of the tumor, and is divided into adult diffuse gliomas, pediatric diffuse gliomas, and ependymal tumors, among other categories[

2] . Within adult diffuse gliomas, Astrocytoma, IDH mutant, WHO grade 2, and Oligodendroglioma, IDH mutant, 1p19q codeleted, WHO grade 2 are classified as diffuse low-grade gliomas (DLGG); whereas Astrocytoma, IDH mutant, WHO grades 3 and 4, Oligodendroglioma, IDH mutant, 1p19q codeleted, WHO grade 2, and Glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype, WHO grade 4 are categorized as diffuse high-grade gliomas (DHGG)[

2] . DLGG constitutes approximately 5% of primary brain tumors and 15% of gliomas[

1,

3].

DLGG exhibits a slower growth rate, a longer disease course, and a variable median survival ranging from 5.6 to 13.3 years[

4] . Some patients can survive for more than 10 years, but over 70% of DLGG cases may progress to DHGG within 10 years. Following malignant transformation, the median overall survival (mOS) of patients is significantly reduced to approximately 2.4 years[

5] . With aggressive treatment, the median survival of DLGG can be extended to about 13 years[

6] . The current standard treatment regimen includes surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, among other modalities[

7].

Radiotherapy occupies a pivotal role in the treatment strategy for patients with DLGG, with its primary objectives being to control residual tumor cells post-surgery, slow the malignant progression of the tumor, and thereby enhance patient survival rates[

8]. For DLGG patients with a more favorable prognosis, although early postoperative radiotherapy compared to delayed radiotherapy can extend progression-free survival (PFS), no significant increase in overall survival (OS) has been observed[

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] (corresponding literature searches were conducted, and the detailed search strategy can be found in the supplementary materials). This also provides a theoretical basis for the possibility of selecting delayed radiotherapy for some DLGG patients postoperatively.

Moreover, radiotherapy may induce short-term side effects such as fatigue and skin damage, as well as long-term complications including cognitive decline, radiation necrosis, and endocrine disorders[

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] These side effects may have an impact on the long-term quality of life(QoL) of patients. Therefore, in order to ensure prolonged survival while avoiding the long-term distress of radiotherapy-related side effects for certain DLGG patients, postoperative radiotherapy may be considered for postponement or termination during the course of treatment. Furthermore, the IDH inhibitor Vorasidenib has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of WHO grade 2 IDH-mutated gliomas, which can extend median PFS and delay radiotherapy to avoid the side effects induced by radiotherapy[

19].

This article systematically reviews the potential risks of postoperative brain radiotherapy in DLGG patients and proposes decision-making strategies for the timing of radiotherapy initiation and termination based on these risks and the individual preferences of patients, aiming to provide a more precise and personalized treatment plan for glioma patients. Through this research, the intention is to assist clinicians in more effectively balancing treatment efficacy with the QoL of patients during the treatment process, in the hope of maximizing patient benefit. Please note that this article does not focus on the specific dosage issues during radiotherapy for DLGG patients, as the RT dose is also one of the most common controversial topics in clinical practice[

20].

2. Side Effects of Cerebral Radiotherapy

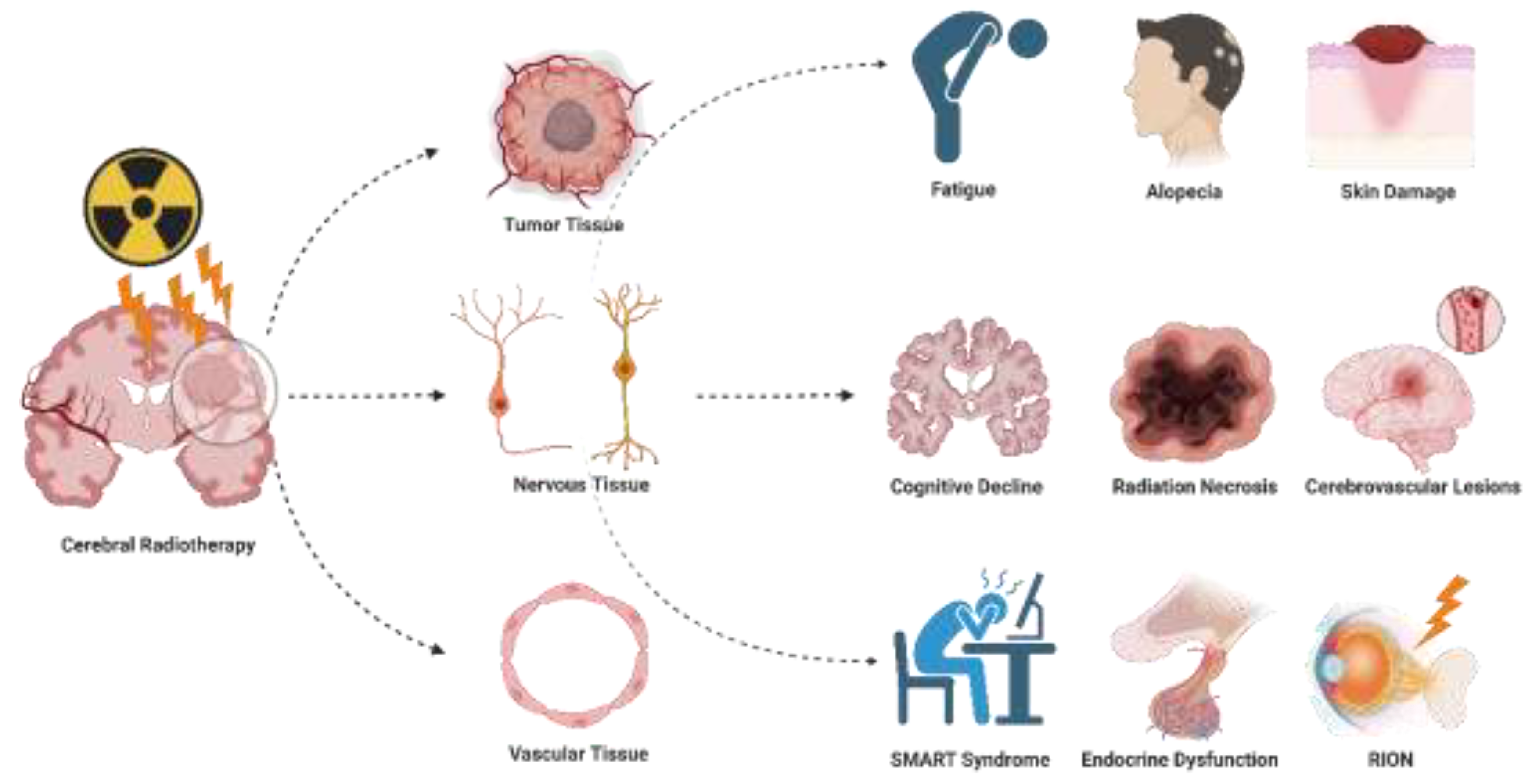

Radiotherapy, while effectively destroying tumor cells, inevitably affects normal tissue, leading to a series of side effects associated with radiation therapy (

Figure 1). These side effects are categorized into acute (short-term) and delayed (long-term) types[

21,

22,

23] . The following section of this article will outline the common clinical manifestations of these side effects and delve into how to guide whether patients require a delay in radiotherapy or a pause during treatment based on these side effects, as well as the patient’s existing complications or special circumstances that may arise during radiotherapy. Additionally, this article will discuss how to more effectively manage and prevent the occurrence and development of these side effects. This will assist physicians in comprehensively weighing the benefits and potential risks of radiotherapy, promoting effective communication between doctors and patients, and collaboratively developing a more refined and individualized treatment plan.

2.1. Acute (Short-Term) Side Effects

2.1.1. Fatigue

Symptom Description: It is well-documented that during the course of radiotherapy, patients commonly experience significant fatigue or somnolence. These fatigue symptoms are generally mild in most cases; however, it is noteworthy that as many as half of the patients may exhibit more severe symptoms. These can limit daily activities, necessitate increased daytime sleep, or fail to show significant reduction in fatigue even after rest. Patients may begin to feel fatigued within the first two weeks after the initiation of radiotherapy, and the level of fatigue may peak between 2 to 4 weeks after the completion of treatment. These symptoms typically subside over several months. Nevertheless, there are reports in the literature indicating that some patients continue to experience fatigue symptoms up to 6 to 12 months after the end of treatment[

24].

Management Strategies: This situation typically indicates that patients require further evaluation to investigate other potential causes of fatigue, which may include sleep disorders, cardiopulmonary diseases, hematologic issues, metabolic or endocrine dysregulation, nutritional deficiencies, depression or emotional disorders, and medication use (including antiepileptic drug therapy)[

24,

25].

Insights into the Decision-Making for the Initiation and Termination of Radiotherapy: If a patient exhibits severe fatigue symptoms before the commencement of radiotherapy, consideration should be given to postponing radiotherapy until the fatigue symptoms have significantly improved. Should a patient experience severe fatigue during radiotherapy that impacts normal daily activities, it may be necessary to promptly interrupt the radiotherapy treatment.

2.1.2. Cerebral Edema

Symptom Description: Cerebral edema typically occurs within days to weeks following radiotherapy to the brain, resulting from transient increases in vascular permeability due to radiation-induced vascular injury[

21,

26] . Patients may present with clinical manifestations of increased intracranial pressure, such as headache (which may also be caused by direct neurological damage from radiotherapy), nausea, vomiting, nuchal rigidity, as well as exacerbation or new onset of seizures. These symptoms severely impact the patient’s QoL and treatment compliance and, in severe cases, may even be life-threatening[

27,

28] . Many patients with brain tumors already exhibit symptoms of mass effect due to the tumor and surrounding edema prior to treatment, such as motor and sensory deficits, memory impairment, and others. Radiotherapy may exacerbate swelling around the tumor, thereby aggravating symptoms associated with diminished neurological function. Although these neurologic dysfunctions are generally temporary and not considered precursors to long-term neurological damage.

Management Strategies: Clinicians commonly employ corticosteroids such as dexamethasone, or bevacizumab (the specific mechanism of which will be discussed in subsequent sections), to alleviate cerebral edema. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) including ibuprofen and loxoprofen sodium are utilized to manage severe headaches. Prophylactic administration of antiepileptic drugs is implemented to control the exacerbation of epilepsy or to prevent the onset of new epileptic seizures[

29] . Additionally, central antiemetic agents like ondansetron are administered to mitigate symptoms of nausea and vomiting. Owing to the paucity of prospective clinical research data, the application of medications other than prophylactic antiepileptic drugs frequently relies on the individual clinical experience of the physician and the severity of the symptoms[

30,

31].

Insights into the Decision-Making for the Initiation and Termination of Radiotherapy: If a patient presents with cerebral edema attributable to the tumor itself or surgical intervention prior to the commencement of radiotherapy, and exhibits neurofunctional deficits that impair QoL, it is prudent to contemplate postponing radiotherapy until a significant reduction in cerebral edema is achieved. The exacerbation of cerebral edema symptoms during the course of radiotherapy serves as an indication for the cessation of radiotherapy and the initiation of interventions targeted at managing the cerebral edema.

2.1.3. Alopecia

Symptom Description: Alopecia is a common side effect observed in patients undergoing cranial radiotherapy, which may cause psychological distress in some individuals. The extent of hair loss is closely related to the dose of radiation therapy administered: lower doses of radiotherapy typically result in reversible alopecia, with complete hair regrowth observed in patients within 2 to 4 months following the completion of radiotherapy. However, higher doses of radiotherapy may lead to permanent hair loss[

32,

33].

Management Strategies: Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) can effectively reduce the cumulative radiation dose to the scalp without compromising the radiation dose to the tumor, thereby potentially mitigating the risk of alopecia[

34,

35].

Insights into the Decision-Making for the Initiation and Termination of Radiotherapy: For patients with a heightened concern for their aesthetic appearance, it may be prudent to consider delaying postoperative radiotherapy or opting for IMRT. In the event of severe alopecia emerging during the course of radiotherapy, the decision to terminate the treatment should be contingent upon the patient’s personal preference and the presence of any concomitant severe symptoms.

2.1.4. Skin Damage

Symptom Description:The skin is highly sensitive to radiotherapy, with over 95% of patients undergoing radiotherapy experiencing skin reactions ranging from moderate to severe[

36]。. In the initial stages of radiotherapy, the skin may exhibit discoloration, erythema, and inflammatory responses. In more severe cases, the damaged skin may present with desquamation, atrophy, and/or the formation of ulcers[

37,

38,

39].

Management Strategies: Interventions include oral systemic medications; skin care practices; steroidal topical therapies; non-steroidal topical therapies; dressings and other measures[

40].

Insights into the Decision-Making for the Initiation and Termination of Radiotherapy: In patients with DLGG who have undergone surgery, initiating radiotherapy when the surgical incision is poorly healed may lead to difficult wound healing and potentially serious consequences such as wound infection. Therefore, radiotherapy must be delayed in the presence of poor postoperative wound healing[

41,

42] . For patients with well-healed postoperative incisions who develop severe dermatitis, ulceration, or other severe skin reactions during radiotherapy, the treatment should be promptly interrupted and appropriate interventions undertaken to control the situation. Severe radiation-induced skin damage not only delays the execution of the tumor treatment plan but, more importantly, significantly impairs the patient’s QoL.

2.2. Late-Onset (Long-Term) Side Effects

Given that late-onset side effects in patients with DLGG manifest at a significantly later time following radiotherapy, insights into the decision-making for the initiation and termination of radiotherapy based on these late-onset side effects are primarily determined on a case-by-case basis for each patient. This aspect will be uniformly addressed in the final subsection of this section.

2.2.1. Cognitive Decline

Symptom Description: The issue of cognitive decline in patients with brain tumors following radiotherapy has been described in the literature, and it represents one of the primary concerns for clinicians when considering the timing of postoperative radiotherapy for patients with DLGG[

43] . An observational study of patients with low-grade gliomas in the Netherlands found that the negative impact of radiotherapy on cognition was observed only in patients receiving radiation doses exceeding 2 Gy per fraction, and the effect of radiotherapy on cognition was more significant compared to that of the brain tumor itself and the use of antiepileptic drugs[

44] . However, a subsequent study by the same research team conducted formal neuropsychological testing on 65 patients from the previous cohort at an average of 12 years post-diagnosis, revealing a gradual decline in certain cognitive functions even in patients receiving hypofractionated radiation doses (≤2 Gy/fraction)[

45].

Management Strategies: Close monitoring of cognitive function during radiotherapy is essential, as it facilitates the early identification of cognitive decline in patients and the implementation of interventions. Potential effective interventions include the use of proton therapy, stem cell therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, memantine, donepezil, methylphenidate, as well as cognitive training and memory enhancement strategies[

46,

47].

2.2.2. Radiation Necrosis

Symptom Description: Radiation necrosis is a late complication of radiotherapy, typically occurring between 1 to 3 years after treatment, but in some cases, it has been reported as late as 10 years following the completion of radiotherapy[

48] . This necrosis often occurs in the vicinity of or surrounding the treatment target area, and its clinical manifestations depend on the location of the necrosis, which may include focal neurological signs or symptoms, increased intracranial pressure, gait and balance abnormalities, and complex deficits in cranial nerves. The incidence of radiation necrosis in patients receiving postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) treatment ranges from 4% to 18% between 6 months to several years after treatment[

49,

50,

51,

52] . The combination of chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy may increase the risk of necrosis to 17%, 25%, and 38%, respectively[

53,

54,

55] . Distinguishing radiation necrosis from tumor progression is often challenging. The imaging features seen on standard MRI are non-specific and usually cannot be clearly differentiated from tumor progression, potentially requiring sequential follow-up to distinguish between tumor progression and radiation necrosis. Advanced imaging techniques may reveal a lactate peak or lipid peak on MRS[

52] , decreased cerebral blood volume (CBV) on tumor perfusion imaging[

50,

56] , restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted MRI[

57] , and lack of uptake on PET/CT[

58] Radiation necrosis is typically a self-limiting process, with symptoms possibly resolving within 5 to 7 months following their appearance.

Management Strategies: Asymptomatic patients can be observed without the need for intervention. For symptomatic patients, treatment with moderate doses of corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone 4-8 mg daily) can be administered until symptoms improve, followed by a gradual tapering of the dose. Follow-up imaging studies at 1 to 2 months post-intervention can aid in confirming the treatment response. For patients who are intolerant to corticosteroids or unable to taper the medication, bevacizumab or laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT) can be considered as treatment options[

59,

60] . Bevacizumab can be very effective, as immunohistochemical analysis of surgical samples from radiation necrosis has confirmed significantly elevated levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in reactive astrocytes surrounding the core of necrotic tissue[

61] . As an important regulator of angiogenesis, increased VEGF leads to increased vascular permeability, damage to the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and subsequent cerebral edema, resulting in symptoms such as headache, nausea, and vomiting[

62] . Bevacizumab, by binding to VEGF, effectively reduces vascular permeability, thereby mitigating damage to the BBB and the extent of cerebral edema[

63,

64] . In cases of refractory necrosis, LITT may be considered, and it can be combined with biopsy[

65,

66] , although there is a lack of high-level clinical evidence to support this approach. In cases with significant mass effect or unclear diagnosis, surgical resection may be required.

2.2.3. Cerebrovascular Diseases

Symptom Description: Radiotherapy-related cerebrovascular diseases are among the potential late complications that may arise following cranial radiotherapy, including cavernous angiomas, ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, and moyamoya disease, which may be associated with radiation-induced damage to cerebral blood vessels. The literature reports that the incidence of these issues is correlated with factors such as younger age at the time of treatment, radiation fields involving the supraclinoid internal carotid artery and Willis’ circle, higher radiation doses, and the concomitant use of chemotherapy[

67,

68,

69] . Cavernous angiomas are the most common type of radiation-related cerebrovascular lesion and may increase in size over time, with a risk of hemorrhage. This condition typically occurs in patients 3 to 6 years after cranial irradiation, with reported incidence rates ranging from 3% to 43%, higher in children than in adults, and increasing with the length of time since radiotherapy completion[

70,

71,

72,

73] . Ischemic strokes may also manifest in the late phase of radiotherapy; in a prospective, randomized study on dose-escalated meningiomas, 20% of patients experienced ischemic strokes at a median of 5.6 years post-treatment[

74] . The total radiation dose to the Willis’ circle may be the greatest risk factor, particularly when the dose exceeds 40 Gy. However, even total doses as low as 10 Gy may lead to ischemic strokes in longer follow-up periods[

75] . Although cranial radiotherapy rarely significantly affects the carotid arteries, it may increase the risk of carotid disease and atherosclerosis, thereby enhancing the risk of ischemic stroke[

76] . Vascular lesions similar to moyamoya disease have been reported to occur at a median of 40 months post-radiotherapy, with younger age (<5 years), type 1 neurofibromatosis, or low-grade glioma being independent risk factors for the development of this lesion[

77,

78] . Radiation-induced aneurysms are a rare but potentially fatal complication of radiotherapy, with the pathogenesis not yet fully understood but possibly related to vascular endothelial cell damage, vascular wall degeneration, and atherosclerosis. These aneurysms are typically cystic or multiple and are more easily detected on magnetic resonance weighted imaging[

79].

Management Strategies: Currently, there are no clear guidelines for the primary or secondary prevention of radiotherapy-related cerebrovascular lesions. From a clinical perspective, it is essential to inform patients and their families about the risks, symptoms, and preventive measures associated with radiotherapy-related cerebrovascular diseases, emphasizing the importance of regular follow-up and monitoring to facilitate timely detection and management of complications. Additionally, information regarding lifestyle and health habits should be provided to reduce the risk of complications.

2.2.4. Post-radiotherapy Stroke-like Migraine Attacks (SMART Syndrome)

Symptom Description: SMART syndrome is a rare delayed complication of cranial irradiation. Patients typically present with migraine-like headaches, epileptic seizures, and subacute stroke-like episodes several years after radiotherapy, with symptoms including hemiparesis, aphasia, and hemianopia. The episodes usually manifest in a subacute manner and often resolve spontaneously after a few weeks. Although the exact mechanism of SMART syndrome is not well understood, the process appears to be attributable to radiation-induced hyperexcitability of the brain, impaired autoregulatory mechanisms, and vascular endothelial damage[

80].

Management Strategies: The treatment of SMART syndrome is primarily symptomatic. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids can alleviate headaches, while medications such as carbamazepine and topiramate can be used to control epileptic seizures. Additionally, patients need to be educated about and avoid potential triggers of headaches, such as stress, sleep disturbances, specific foods or beverages, etc.[

81].

2.2.5. Endocrine Dysfunction

Symptom Description: Late endocrine dysfunction is quite prevalent among patients who have undergone radiotherapy, with approximately 80% of patients potentially exhibiting hypothalamic and pituitary dysfunction following exposure to as low as a 20 Gy treatment dose[

82,

83,

84] . Endocrine-related issues may arise within the first year following radiotherapy, and the incidence of these issues may increase over time. In patients with non-pituitary tumors who have received radiotherapy, between 37% and 77% of patients are diagnosed with hypopituitarism between 3 to 13 years post-radiotherapy. The most common pituitary dysfunctions include growth hormone deficiency (50%), gonadotropin deficiency (25%), hyperprolactinemia (24%), adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiency (19%), and central hypothyroidism (16%)[

84].

Management Strategies: Patients undergoing cranial radiotherapy should undergo a comprehensive evaluation of endocrine function prior to radiotherapy, including assessments of growth hormone, gonadotropins, prolactin, adrenocorticotropic hormone, and thyroid function. Following the completion of radiotherapy, regular follow-up examinations should be scheduled to monitor changes in hormone levels and to assess the function of relevant target organs. For patients with reduced or deficient hormone levels, hormone replacement therapy should be initiated to supplement the deficient hormones and maintain normal physiological functions. For patients with hyperprolactinemia, pharmacological treatment with dopamine agonists can be employed.

2.2.6. Impact on Vision

Symptom Description: Radiotherapy-induced optic neuropathy (RION) typically presents as painless visual impairment (unilateral or bilateral, depending on the site of injury) between 6 to 24 months after treatment. Symptoms may progressively worsen over a period of one week to several weeks following onset. The incidence and severity of RION are positively correlated with the total radiation dose received. It has been reported that for conventional fractionated radiotherapy, the incidence of optic neuropathy is very low when the total dose is below 55 Gy; the incidence rate is 3% to 7% with total doses ranging from 55 to 60 Gy; and the incidence increases to 7% to 20% when the total dose exceeds 60 Gy[

85] . In SRS treatments, the incidence of RION is significantly reduced when the single radiation dose to the visual pathway is maintained at 10 Gy or below, or 12 Gy or below[

86,

87].

Management Strategies: A formal neuro-ophthalmological examination can be used to confirm visual loss and assess the health of the optic disc and optic nerve. MRI may reveal signal abnormalities in the optic nerve, with optic nerve enhancement[

81,

88] . However, there is currently no definitive treatment that significantly improves the prognosis for patients with RION. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy, corticosteroids, and anticoagulant therapy may show some efficacy in specific cases, but there is a lack of high-level clinical evidence to support these treatment modalities[

89].

2.2.7. Decision Insights for the Initiation and Termination of Radiotherapy Based on Late-Onset Side Effects

According to the latest report by Martin J. van den Bent on primary malignant brain tumors, the decision to initiate adjuvant therapy immediately postoperatively or to observe first and consider reoperation or adjuvant treatments such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy upon tumor progression is based on factors including whether the patient’s age is >50 years, the presence of residual tumor post-surgery, preoperative tumor volume, preoperative tumor contrast enhancement on MRI, and whether the tumor has caused neurological symptoms[

90]. Therefore, for patients with DLGG who are in good condition postoperatively, radiotherapy may be delayed until clinical or radiological progression is observed through regular and meticulous follow-up monitoring. For patients with tumors located in functional areas, larger residual tumor volumes, severe seizure symptoms, or age >50 years, the time to tumor progression may be shorter, and the impact on neurological function and QoL following tumor progression may exceed the effects of early postoperative radiotherapy. Thus, these patients may require more aggressive early postoperative radiotherapy. For DLGG patients with preexisting severe cognitive decline, cerebrovascular disease, optic nerve function compromised by tumor compression or other causes, headache, or high risk factors for radiation necrosis (such as combined immunotherapy and targeted therapy), careful consideration should be given to whether radiotherapy should be administered upon tumor progression, as the exacerbation of these conditions due to radiotherapy can also severely impact long-term QoL and may even be life-threatening.

During the treatment of patients who have already initiated radiotherapy, it is necessary to closely monitor cognitive function, optic nerve function, endocrine function, and symptoms such as headache, and then consider discontinuing radiotherapy based on the patient’s condition to avoid further symptom exacerbation.

It should be noted that the individual needs of the patient must also be taken into account. For instance, a DLGG patient engaged in mentally demanding work who wishes to absolutely avoid the potential for early cognitive decline post-radiotherapy may prefer to consider radiotherapy only upon tumor progression. Similarly, a pregnant DLGG patient might make the same choice. This necessitates thorough communication between the clinical physician and the patient.

Table 1.

An Overview of Strategies for Timing the Initiation or Termination of Postoperative Radiotherapy in Patients with DLGG.

Table 1.

An Overview of Strategies for Timing the Initiation or Termination of Postoperative Radiotherapy in Patients with DLGG.

| Strategies for Timing of Radiotherapy |

Patient-specific Conditions |

| Postoperative Early Radiotherapy |

Tumor located in eloquent area, Substantial residual tumor volume, Severe epileptic seizures,

Age > 50 |

| Radiotherapy following tumor progression |

Tumor not located in eloquent area,

No residual tumor,

No seizures,

Age < 50,

Poor surgical incision healing,

Severe cerebral edema,

Cognitive decline,

Cerebrovascular disease,

Decreased optic nerve function, Headache,

Risk factors for radiation necrosis,

Patient’s personal preferences |

| Termination of Radiotherapy |

The exacerbation of comorbidities |

3. Conclusions

In summary, the primary challenge faced by physicians in determining the timing of radiotherapy initiation and discontinuation for patients with DLGG remains the significant long-term decline in QoL associated with radiotherapy side effects across different patients. The ability to predict whether an individual patient will experience a severe and prolonged decrease in QoL following radiotherapy would facilitate the determination of the optimal timing for radiotherapy initiation. With the advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) technology, researchers can utilize clinical feature information to predict specific outcomes. For instance, factors such as age, gender, tumor size, tumor grade, and presence of comorbidities can be included as predictive variables in the model, with the likelihood of a patient experiencing a long-term and severe decline in QoL after radiotherapy as the outcome to be predicted. Techniques such as logistic regression or machine learning can be employed to construct predictive models, thereby assisting clinicians and patients in the joint decision-making process regarding the deferral of radiotherapy. This requires a substantial amount of data to build and validate the model.

The studies available in the literature comparing early postoperative radiotherapy with delayed radiotherapy in DLGG patients[

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] are dated, with pathologic diagnoses of gliomas more heavily reliant on histology at the time of publication. Currently, the diagnosis of diffuse gliomas includes molecular diagnostics. Astrocytomas previously classified as WHO Grade 2 may now be diagnosed as WHO Grade 4 astrocytomas or glioblastomas. Consequently, the results of these studies may require reevaluation, as some DLGG cases might now be reclassified as DHGG, potentially affecting the final outcomes. Therefore, it may be necessary to conduct new retrospective studies or prospective studies under the new diagnostic criteria to reassess the accuracy of the impact of early versus delayed postoperative radiotherapy on OS and PFS in DLGG patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. The complete search strategy is outlined in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

XZ and WW searched and assessed articles, and drafted the manuscript. YW, XL and WM supervised the review. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-B-113), the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-A-019) for Yu Wang, the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2021-12M-1-014), and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82151302).

Acknowledgments

In this section you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declared no conflict of interest.

Declarations:

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of this manuscript in Caners journal.

Availability of data and materials

References

- Ostrom, Q.T., et al., CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2016—2020. Neuro-Oncology, 2023. 25(Supplement_4): p. iv1-iv99. [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N., et al., The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro-Oncology, 2021/08/02. 23(8). [CrossRef]

- Nunna, R.S., et al., Radiotherapy in adult low-grade glioma: nationwide trends in treatment and outcomes. Clinical & translational oncology : official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico, 2021. 23(3): p. 628-637.

- Lombardi, G., et al., Clinical Management of Diffuse Low-Grade Gliomas. Cancers, 2020 Oct 16. 12(10). [CrossRef]

- Tom, M.C., et al., Malignant Transformation of Molecularly Classified Adult Low-Grade Glioma. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics, 2019. 105(5): p. 1106-1112. [CrossRef]

- Bush, N.A.O. and S. Chang, Treatment Strategies for Low-Grade Glioma in Adults. Journal of Oncology Practice, 2016-12-12. 12(12). [CrossRef]

- Weller, M., et al., EANO guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diffuse gliomas of adulthood. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2020 18:3, 2020-12-08. 18(3). [CrossRef]

- Jakola, A.S., et al., Spatial distribution of malignant transformation in patients with low-grade glioma. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 2020 Jan 9. 146(2). [CrossRef]

- van den Bent, M.J., et al., Long-term efficacy of early versus delayed radiotherapy for low-grade astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma in adults: the EORTC 22845 randomised trial. Lancet (London, England), 2005. 366(9490): p. 985-90. [CrossRef]

- Buglione, M., et al., Radiotherapy in low-grade glioma adult patients: a retrospective survival and neurocognitive toxicity analysis. Radiol Med, 2014. 119(6): p. 432-9. [CrossRef]

- Hanzély, Z., et al., Role of early radiotherapy in the treatment of supratentorial WHO Grade II astrocytomas: long-term results of 97 patients. J Neurooncol, 2003. 63(3): p. 305-12. [CrossRef]

- Leighton, C., et al., Supratentorial low-grade glioma in adults: an analysis of prognostic factors and timing of radiation. J Clin Oncol, 1997. 15(4): p. 1294-301. [CrossRef]

- Obara, T., et al., Adult Diffuse Low-Grade Gliomas: 35-Year Experience at the Nancy France Neurooncology Unit. Front Oncol, 2020. 10: p. 574679. [CrossRef]

- Makale, M.T., et al., Mechanisms of radiotherapy-associated cognitive disability in patients with brain tumours. Nat Rev Neurol, 2017. 13(1): p. 52-64. [CrossRef]

- Voon, N.S., H. Abdul Manan, and N. Yahya, Cognitive Decline following Radiotherapy of Head and Neck Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of MRI Correlates. Cancers (Basel), 2021. 13(24). [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.D., et al., Association of Long-term Outcomes With Stereotactic Radiosurgery vs Whole-Brain Radiotherapy for Resected Brain Metastasis: A Secondary Analysis of The N107C/CEC.3 (Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology/Canadian Cancer Trials Group) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol, 2022. 8(12): p. 1809-1815.

- Yang, X., H. Ren, and J. Fu, Treatment of Radiation-Induced Brain Necrosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2021. 2021: p. 4793517. [CrossRef]

- Taphoorn, M.J., et al., Endocrine functions in long-term survivors of low-grade supratentorial glioma treated with radiation therapy. J Neurooncol, 1995. 25(2): p. 97-102. [CrossRef]

- Nakhate, V., A.B. Lasica, and P.Y. Wen, The Role of Mutant IDH Inhibitors in the Treatment of Glioma. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., et al., Association of high-dose radiotherapy with improved survival in patients with newly diagnosed low-grade gliomas. Cancer, 2022. 128(5): p. 1085-1092. [CrossRef]

- Sheline, G.E., W.M. Wara, and V. Smith, Therapeutic irradiation and brain injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 1980. 6(9): p. 1215-28. [CrossRef]

- Wujanto, C., et al., Radiotherapy to the brain: what are the consequences of this age-old treatment? Ann Palliat Med, 2021. 10(1): p. 936-952.

- Tanguturi, S.K. and B.M. Alexander, Neurologic Complications of Radiation Therapy. Neurol Clin, 2018. 36(3): p. 599-625. [CrossRef]

- Powell, C., et al., Somnolence syndrome in patients receiving radical radiotherapy for primary brain tumours: a prospective study. Radiother Oncol, 2011. 100(1): p. 131-6. [CrossRef]

- Faithfull, S. and M. Brada, Somnolence syndrome in adults following cranial irradiation for primary brain tumours. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol), 1998. 10(4): p. 250-4. [CrossRef]

- Milano, M.T., et al., Radiation-Induced Edema After Single-Fraction or Multifraction Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Meningioma: A Critical Review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2018. 101(2): p. 344-357. [CrossRef]

- Greene-Schloesser, D., et al., Radiation-induced brain injury: A review. Front Oncol, 2012. 2: p. 73. [CrossRef]

- Young, D.F., et al., Rapid-course radiation therapy of cerebral metastases: results and complications. Cancer, 1974. 34(4): p. 1069-76.

- Avila, E.K., et al., Brain tumor-related epilepsy management: A Society for Neuro-oncology (SNO) consensus review on current management. Neuro Oncol, 2024. 26(1): p. 7-24. [CrossRef]

- Arvold, N.D., et al., Steroid and anticonvulsant prophylaxis for stereotactic radiosurgery: Large variation in physician recommendations. Pract Radiat Oncol, 2016. 6(4): p. e89-e96. [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.L., et al., Use of steroids to suppress vascular response to radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 1987. 13(4): p. 563-7. [CrossRef]

- Severs, G.A., T. Griffin, and M. Werner-Wasik, Cicatricial alopecia secondary to radiation therapy: case report and review of the literature. Cutis, 2008. 81(2): p. 147-53.

- Ali, S.Y. and G. Singh, Radiation-induced Alopecia. Int J Trichology, 2010. 2(2): p. 118-9. [CrossRef]

- Witek, M., et al., Dose Reduction to the Scalp with Hippocampal Sparing Is Achievable with Intensity Modulated Radiotherapy. Int J Med Phys Clin Eng Radiat Oncol, 2014. 3(3): p. 176-182.

- Yu, H., et al., Dosimetric comparison of advanced radiation techniques for scalp-sparing in low-grade gliomas. Strahlenther Onkol, 2024. 200(9): p. 785-796.

- Porock, D., S. Nikoletti, and L. Kristjanson, Management of radiation skin reactions: literature review and clinical application. Plast Surg Nurs, 1999. 19(4): p. 185-92, 223; quiz 191-2.

- Straub, J.M., et al., Radiation-induced fibrosis: mechanisms and implications for therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2015. 141(11): p. 1985-94.

- O'Sullivan, B. and W. Levin, Late radiation-related fibrosis: pathogenesis, manifestations, and current management. Semin Radiat Oncol, 2003. 13(3): p. 274-89. [CrossRef]

- Delanian, S. and J.L. Lefaix, Current management for late normal tissue injury: radiation-induced fibrosis and necrosis. Semin Radiat Oncol, 2007. 17(2): p. 99-107. [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.J., et al., Prevention and treatment of acute radiation-induced skin reactions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer, 2014. 14: p. 53. [CrossRef]

- Haubner, F., et al., Wound healing after radiation therapy: review of the literature. Radiat Oncol, 2012. 7: p. 162. [CrossRef]

- Dormand, E.L., P.E. Banwell, and T.E. Goodacre, Radiotherapy and wound healing. Int Wound J, 2005. 2(2): p. 112-27. [CrossRef]

- Schaff, L.R., et al., State of the Art in Low-Grade Glioma Management: Insights From Isocitrate Dehydrogenase and Beyond. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 2024. 44(3): p. e431450. [CrossRef]

- Klein, M., et al., Effect of radiotherapy and other treatment-related factors on mid-term to long-term cognitive sequelae in low-grade gliomas: a comparative study. Lancet, 2002. 360(9343): p. 1361-8. [CrossRef]

- Douw, L., et al., Cognitive and radiological effects of radiotherapy in patients with low-grade glioma: long-term follow-up. Lancet Neurol, 2009. 8(9): p. 810-8. [CrossRef]

- Shamsesfandabadi, P., et al., Radiation-Induced Cognitive Decline: Challenges and Solutions. Cancer Manag Res, 2024. 16: p. 1043-1052.

- Cramer, C.K., et al., Treatment of Radiation-Induced Cognitive Decline in Adult Brain Tumor Patients. Curr Treat Options Oncol, 2019. 20(5): p. 42. [CrossRef]

- Strenger, V., et al., Incidence and clinical course of radionecrosis in children with brain tumors. A 20-year longitudinal observational study. Strahlenther Onkol, 2013. 189(9): p. 759-64. [CrossRef]

- Kano, H., et al., T1/T2 matching to differentiate tumor growth from radiation effects after stereotactic radiosurgery. Neurosurgery, 2010. 66(3): p. 486-91; discussion 491-2.

- Sugahara, T., et al., Posttherapeutic intraaxial brain tumor: the value of perfusion-sensitive contrast-enhanced MR imaging for differentiating tumor recurrence from nonneoplastic contrast-enhancing tissue. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2000. 21(5): p. 901-9.

- Henry, R.G., et al., Comparison of relative cerebral blood volume and proton spectroscopy in patients with treated gliomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2000. 21(2): p. 357-66.

- Kimura, T., et al., Evaluation of the response of metastatic brain tumors to stereotactic radiosurgery by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, 201TlCl single-photon emission computerized tomography, and gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg, 2004. 100(5): p. 835-41. [CrossRef]

- Correa, D.D., et al., Cognitive functions in low-grade gliomas: disease and treatment effects. J Neurooncol, 2007. 81(2): p. 175-84. [CrossRef]

- Kiehna, E.N., et al., Changes in attentional performance of children and young adults with localized primary brain tumors after conformal radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol, 2006. 24(33): p. 5283-90. [CrossRef]

- Jalali, R., et al., Efficacy of Stereotactic Conformal Radiotherapy vs Conventional Radiotherapy on Benign and Low-Grade Brain Tumors: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol, 2017. 3(10): p. 1368-1376.

- Mitsuya, K., et al., Perfusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging to distinguish the recurrence of metastatic brain tumors from radiation necrosis after stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neurooncol, 2010. 99(1): p. 81-8. [CrossRef]

- Asao, C., et al., Diffusion-weighted imaging of radiation-induced brain injury for differentiation from tumor recurrence. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2005. 26(6): p. 1455-60.

- Schwartz, R.B., et al., Dual-isotope single-photon emission computerized tomography scanning in patients with glioblastoma multiforme: association with patient survival and histopathological characteristics of tumor after high-dose radiotherapy. J Neurosurg, 1998. 89(1): p. 60-8. [CrossRef]

- Miyatake, S., et al., Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Radiation Necrosis in the Brain. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo), 2015. 55 Suppl 1: p. 50-9.

- Bernhardt, D., et al., DEGRO practical guideline for central nervous system radiation necrosis part 1: classification and a multistep approach for diagnosis. Strahlenther Onkol, 2022. 198(10): p. 873-883. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., et al., Anti-VEGF antibodies mitigate the development of radiation necrosis in mouse brain. Clin Cancer Res, 2014. 20(10): p. 2695-702. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H., et al., Bevacizumab treatment for radiation brain necrosis: mechanism, efficacy and issues. Mol Cancer, 2019. 18(1): p. 21. [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.T., et al., Bevacizumab reverses cerebral radiation necrosis. J Clin Oncol, 2008. 26(34): p. 5649-50. [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.T. and S. Brem, Antiangiogenesis treatment for glioblastoma multiforme: challenges and opportunities. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2008. 6(5): p. 515-22. [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.S., et al., Magnetic resonance-guided laser ablation improves local control for postradiosurgery recurrence and/or radiation necrosis. Neurosurgery, 2014. 74(6): p. 658-67; discussion 667. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J., et al., Long-Term Follow-up of 25 Cases of Biopsy-Proven Radiation Necrosis or Post-Radiation Treatment Effect Treated With Magnetic Resonance-Guided Laser Interstitial Thermal Therapy. Neurosurgery, 2016. 79 Suppl 1: p. S59-s72. [CrossRef]

- Campen, C.J., et al., Cranial irradiation increases risk of stroke in pediatric brain tumor survivors. Stroke, 2012. 43(11): p. 3035-40. [CrossRef]

- Bowers, D.C., et al., Late-occurring stroke among long-term survivors of childhood leukemia and brain tumors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol, 2006. 24(33): p. 5277-82. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.S., et al., Review of cranial radiotherapy-induced vasculopathy. J Neurooncol, 2015. 122(3): p. 421-9. [CrossRef]

- Strenger, V., et al., Intracerebral cavernous hemangioma after cranial irradiation in childhood. Incidence and risk factors. Strahlenther Onkol, 2008. 184(5): p. 276-80. [CrossRef]

- Burn, S., et al., Incidence of cavernoma development in children after radiotherapy for brain tumors. J Neurosurg, 2007. 106(5 Suppl): p. 379-83. [CrossRef]

- Lew, S.M., et al., Cumulative incidence of radiation-induced cavernomas in long-term survivors of medulloblastoma. J Neurosurg, 2006. 104(2 Suppl): p. 103-7.

- Heckl, S., A. Aschoff, and S. Kunze, Radiation-induced cavernous hemangiomas of the brain: a late effect predominantly in children. Cancer, 2002. 94(12): p. 3285-91.

- Sanford, N.N., et al., Prospective, Randomized Study of Radiation Dose Escalation With Combined Proton-Photon Therapy for Benign Meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2017. 99(4): p. 787-796. [CrossRef]

- El-Fayech, C., et al., Cerebrovascular Diseases in Childhood Cancer Survivors: Role of the Radiation Dose to Willis Circle Arteries. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2017. 97(2): p. 278-286. [CrossRef]

- Thalhammer, C., et al., Carotid artery disease after head and neck radiotherapy. Vasa, 2015. 44(1): p. 23-30. [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.S., et al., Radiation-induced moyamoya syndrome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2006. 65(4): p. 1222-7. [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, N.J., et al., Moyamoya following cranial irradiation for primary brain tumors in children. Neurology, 2007. 68(12): p. 932-8. [CrossRef]

- Nanney, A.D., 3rd, et al., Intracranial aneurysms in previously irradiated fields: literature review and case report. World Neurosurg, 2014. 81(3-4): p. 511-9.

- Black, D.F., et al., Stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy (SMART) syndrome is not always completely reversible: a case series. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2013. 34(12): p. 2298-303. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q., et al., Stroke-like Migraine Attacks after Radiation Therapy Syndrome. Chin Med J (Engl), 2015. 128(15): p. 2097-101. [CrossRef]

- Pai, H.H., et al., Hypothalamic/pituitary function following high-dose conformal radiotherapy to the base of skull: demonstration of a dose-effect relationship using dose-volume histogram analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2001. 49(4): p. 1079-92. [CrossRef]

- Minniti, G., et al., The long-term efficacy of conventional radiotherapy in patients with GH-secreting pituitary adenomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2005. 62(2): p. 210-6. [CrossRef]

- Appelman-Dijkstra, N.M., et al., Pituitary dysfunction in adult patients after cranial radiotherapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2011. 96(8): p. 2330-40.

- Mayo, C., et al., Radiation dose-volume effects of optic nerves and chiasm. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2010. 76(3 Suppl): p. S28-35. [CrossRef]

- Leavitt, J.A., et al., Long-term evaluation of radiation-induced optic neuropathy after single-fraction stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2013. 87(3): p. 524-7. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, B.E., et al., Dose-volume analysis of radiation-induced optic neuropathy after single-fraction stereotactic radiosurgery. Neurosurgery, 2014. 75(4): p. 456-60; discussion 460. [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.L., E.A. Liao, and J.D. Trobe, Radiation-Induced Optic Neuropathy: Clinical and Imaging Profile of Twelve Patients. J Neuroophthalmol, 2019. 39(2): p. 170-180. [CrossRef]

- Malik, A. and K. Golnik, Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of radiation optic neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol, 2012. 32(2): p. 128-31. [CrossRef]

- van den Bent, M.J., et al., Primary brain tumours in adults. Lancet, 2023. 402(10412): p. 1564-1579. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).