Submitted:

12 August 2024

Posted:

14 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

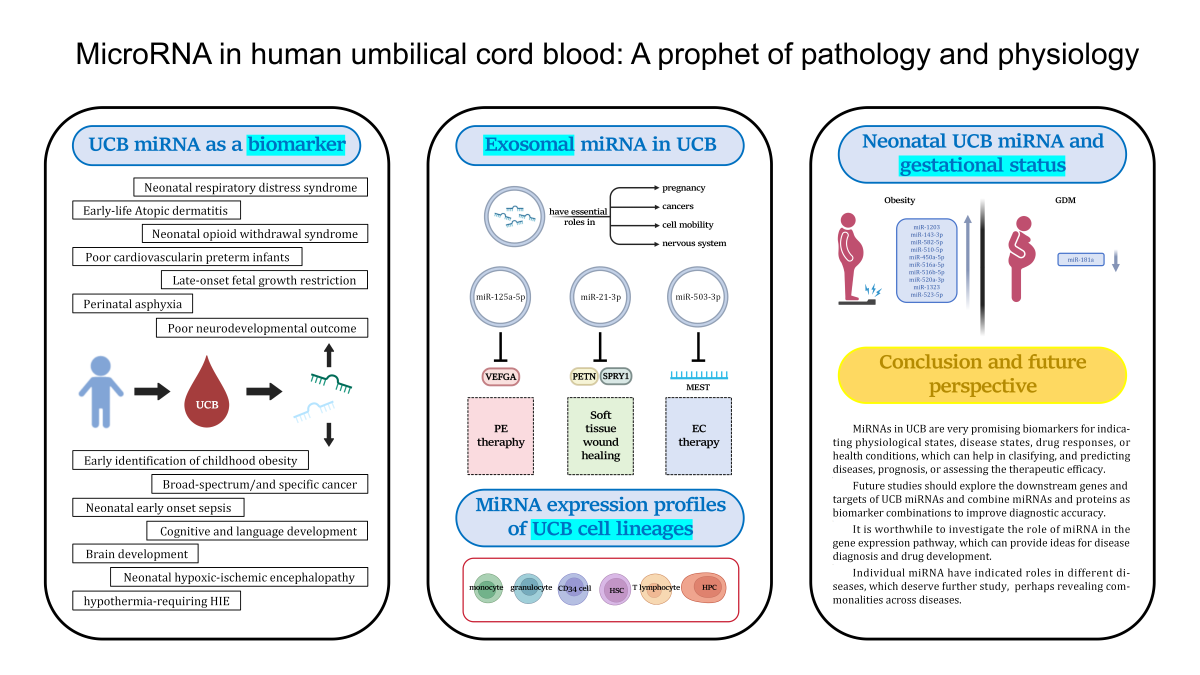

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

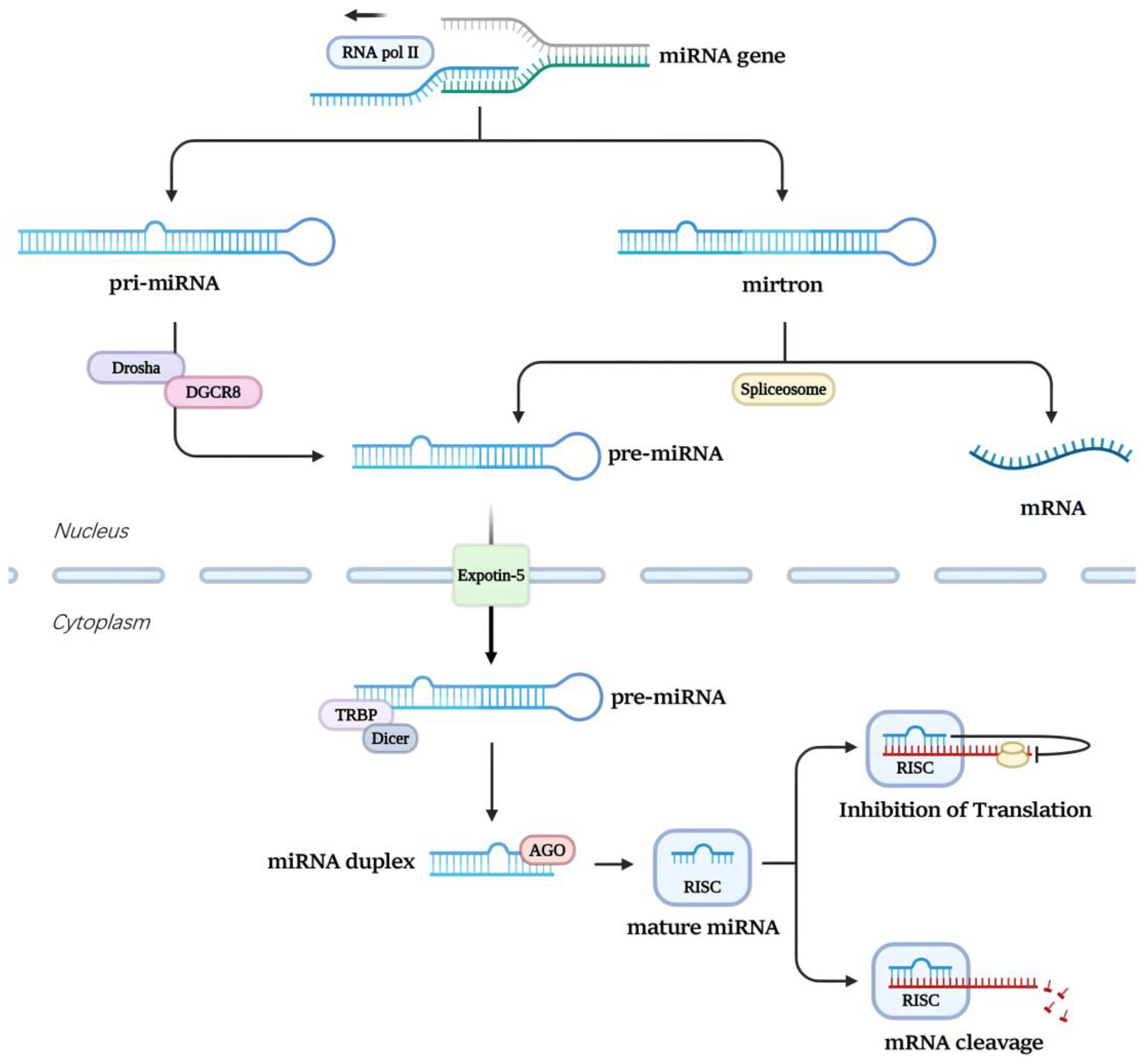

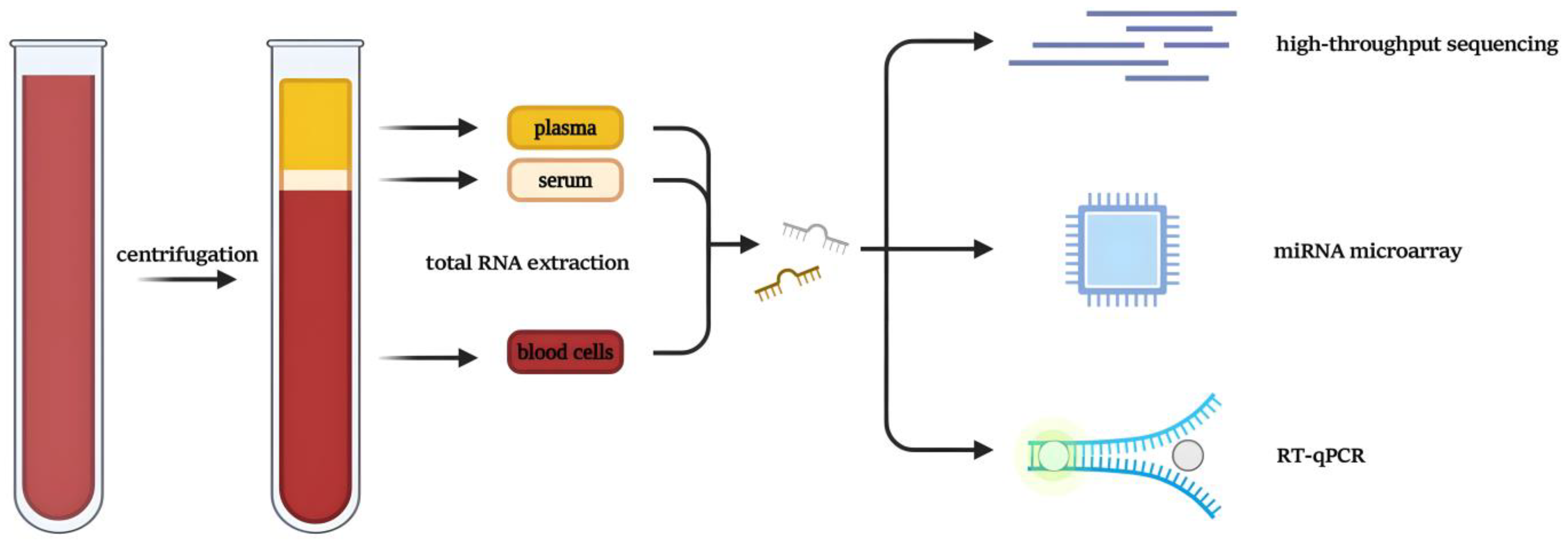

2. Biogenesis and Transport of miRNA

3. Umbilical Cord Blood miRNA in Relation to the Pathology and Physiology of Infants

3.1. Biomarkers of Normal Fetal Development

| MiRNA | UCB sample type | Function | Ref. |

| miR-142-5p miR-140-3p |

umbilical cord white blood cells | Assessing cognitive and language development in infants later in life | [46] |

| miR-210-3p | umbilical cord plasma | A biomarker of the functional status of the placent and helping to predict whether fetal weight is out of balance or not | [49] |

| miR-146a-5p miR-93-5p miR-182-5p miR-21-5p miR-16-5p |

umbilical cord plasma | A biomarker of whether fetal brain development is normal and helping for prenatal diagnosis of fetal brain development and tracking the brain development process of newborns | [50] |

3.2. Premature Birth

3.3. Late-Onset Fetal Growth Restriction

3.4. Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome

3.5. Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy

3.6. Neonatal Early Onset Sepsis

3.7. Atopicdermatitis

3.8. Childhood Obesity

3.9. Pan-Cancer and Oncofetal miRNA

| MiRNA | UCB sample type | Function | Ref. |

| miR-125 miR-145 miR-126 miR-150 miR-155 |

peripheral blood mononuclear cells | For early prediction of poor cardiovascular prognosis in preterm infants | [54] |

| miR-375 | umbilical cord serum | A biomarker of screening NRDS class III-IV neonates | [57] |

| miR-25-3p miR-148b-3p miR 185-5p miR-132-3p |

umbilical vein plasma | Biomarkers to increase the late-onset FGR diagnosis’ precision | [68,71] |

| miR-185-5p miR-132 |

umbilical cord plasma | Biomarkers to increase the late-onset FGR diagnosis’ precision | [45,70] |

| miR-421 miR-30c-5p miR-584-5p let-7d-5p miR-128-3p |

umbilical cord plasma | Biomarkers of predicting the need for pharmacological treatment in NOWS infants | [43] |

| let-7b-5p miR-421 miR-30c-5p miR-128-3p miR-10b-5p |

umbilical cord plasma | Biomarkers for prediction of prolonged hospitalization in NOWS infants | [43] |

| miR-374a | whole cord blood | Distinguishing an infant with perinatal asphyxia from an infant with HIE | [44,84] |

| miR-181b | whole cord blood | Distinguishing an infant with moderate or severe HIE | [44,86] |

| miR-376c-3p | whole cord blood | Distinguishing an infant with perinatal asphyxia or a healthy infant | [44] |

| miR-124-3p miR-1285-5p miR-331-5p |

dried blood spots | Distinguishing an infant with perinatal asphyxia or a healthy infant | [87] |

| miR-30e-5p miR-98-5p miR-497-5p miR-34b-3p miR-338-3p miR-142-3p |

dried blood spots | Biomarkers for hypothermia-requiring HIE | [87] |

| miR-145-5p | dried blood spots | A biomarker for poor neurodevelopmental outcome | [87] |

| miR-211-5p miR-142-3p |

umbilical cord plasma | Biomarkers of the diagnostic work-up for EOS | [89] |

| miR-144 | umbilical cord serum | A biomarkers of predicting the early-life AD | [97] |

| miR-516-3p miR-130a-3p miR-1260b miR-4709-3p miR-194-3p |

umbilical cord serum | Biomarkers to facilitate early detection of childhood obesity | [101] |

| miR-223-3p miR-20b-5p miR-92a-3p miR-19a-3p miR-425-5p miR-25-3p miR-93-5p miR-20a-5p miR-19b-3p |

umbilical cord serum | As broad-spectrum/and specific biomarkers for cancer detection | [105] |

| miR-106a-5p miR-146a-5p miR-584-5p miR-18a-5p miR-409-3p miR-21-5p miR-210-3p miR-20b-5p |

umbilical cord plasma | As broad-spectrum/and specific biomarkers for cancer detection | [105] |

4. The Relationship between Neonatal miRNA Expression Profiles in Umbilical Cord Blood and Maternal Gestational Status

4.1. Maternal Obesity

4.2. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

5. MiRNA Expression Profiles from Umbilical Cord Blood Cell Lineages

6. Exosomal miRNA in Umbilical Cord Blood

6.1. Preeclampsia

6.2. Endometrial Cancer Therapy

6.3. Cutaneous Wound Healing

7. Conclusion and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hüttenhofer, A.; Schattner, P.; Polacek, N. Non-Coding RNAs: Hope or Hype? Trends in Genetics 2005, 21, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameres, S.L.; Zamore, P.D. Diversifying microRNA Sequence and Function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013, 14, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, J.A.; Baxter, D.H.; Zhang, S.; Huang, D.Y.; How Huang, K.; Jen Lee, M.; Galas, D.J.; Wang, K. The MicroRNA Spectrum in 12 Body Fluids. Clinical Chemistry 2010, 56, 1733–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkerova, M.; Vasikova, A.; Belickova, M.; Bruchova, H. MicroRNA Expression Profiles in Umbilical Cord Blood Cell Lineages. Stem Cells and Development 2010, 19, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo, J.D.; Chevillet, J.R.; Kroh, E.M.; Ruf, I.K.; Pritchard, C.C.; Gibson, D.F.; Mitchell, P.S.; Bennett, C.F.; Pogosova-Agadjanyan, E.L.; Stirewalt, D.L.; et al. Argonaute2 Complexes Carry a Population of Circulating microRNAs Independent of Vesicles in Human Plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 5003–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickers, K.C.; Palmisano, B.T.; Shoucri, B.M.; Shamburek, R.D.; Remaley, A.T. MicroRNAs Are Transported in Plasma and Delivered to Recipient Cells by High-Density Lipoproteins. Nat Cell Biol 2011, 13, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Théry, C. Exosomes: Secreted Vesicles and Intercellular Communications. F1000 Biol Rep 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogure, T.; Lin, W.-L.; Yan, I.K.; Braconi, C.; Patel, T. Intercellular Nanovesicle-Mediated microRNA Transfer: A Mechanism of Environmental Modulation of Hepatocellular Cancer Cell Growth. Hepatology 2011, 54, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baergen, R.N. Cord Abnormalities, Structural Lesions, and Cord “Accidents. ” Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology 2007, 24, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, W.; Liu, C.; Na, Q. Umbilical Cord Blood-Derived Exosomes in Maternal–Fetal Disease: A Review. Reprod. Sci. 2023, 30, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornburg, K.L.; Marshall, N. The Placenta Is the Center of the Chronic Disease Universe. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2015, 213, S14–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.X.W.; Candia, A.A.; Sferruzzi-Perri, A.N. Placental Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Fetal Outcomes in Maternal Obesity. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, K. IFPA Gabor Than Award Lecture: Molecular Control of Placental Growth: The Emerging Role of microRNAs. Placenta 2013, 34, S27–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A.B.; Kertes, D.A.; McNamara, G.I.; Braithwaite, E.C.; Creeth, H.D.J.; Glover, V.I.; John, R.M. A Role for the Placenta in Programming Maternal Mood and Childhood Behavioural Disorders. J Neuroendocrinology 2016, 28, jne–12373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guma, E.; Chakravarty, M.M. Immune Alterations in the Intrauterine Environment Shape Offspring Brain Development in a Sex-Specific Manner. Biological Psychiatry 2024, S0006322324012605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.C.P.D.; Carneiro, F.D.; Almeida, K.C.D.; Fernandes-Santos, C. Role of miRNAs on the Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Diseases. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denli, A.M.; Tops, B.B.J.; Plasterk, R.H.A.; Ketting, R.F.; Hannon, G.J. Processing of Primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor Complex. Nature 2004, 432, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcón, C.R.; Lee, H.; Goodarzi, H.; Halberg, N.; Tavazoie, S.F. N6-Methyladenosine Marks Primary microRNAs for Processing. Nature 2015, 519, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Lee, Y.; Yeom, K.-H.; Kim, Y.-K.; Jin, H.; Kim, V.N. The Drosha-DGCR8 Complex in Primary microRNA Processing. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 3016–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, C.; Yamashita, E.; Lee, S.J.; Shibata, S.; Katahira, J.; Nakagawa, A.; Yoneda, Y.; Tsukihara, T. A High-Resolution Structure of the Pre-microRNA Nuclear Export Machinery. Science 2009, 326, 1275–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Kolb, F.A.; Jaskiewicz, L.; Westhof, E.; Filipowicz, W. Single Processing Center Models for Human Dicer and Bacterial RNase III. Cell 2004, 118, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoda, M.; Kawamata, T.; Paroo, Z.; Ye, X.; Iwasaki, S.; Liu, Q.; Tomari, Y. ATP-Dependent Human RISC Assembly Pathways. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010, 17, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, J.G.; Jan, C.H.; Bartel, D.P. Intronic microRNA Precursors That Bypass Drosha Processing. Nature 2007, 448, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babiarz, J.E.; Ruby, J.G.; Wang, Y.; Bartel, D.P.; Blelloch, R. Mouse ES Cells Express Endogenous shRNAs, siRNAs, and Other Microprocessor-Independent, Dicer-Dependent Small RNAs. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 2773–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamura, K.; Hagen, J.W.; Duan, H.; Tyler, D.M.; Lai, E.C. The Mirtron Pathway Generates microRNA-Class Regulatory RNAs in Drosophila. Cell 2007, 130, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condorelli, G.; Latronico, M.V.G.; Cavarretta, E. microRNAs in Cardiovascular Diseases. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2014, 63, 2177–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romaine, S.P.R.; Tomaszewski, M.; Condorelli, G.; Samani, N.J. MicroRNAs in Cardiovascular Disease: An Introduction for Clinicians. Heart 2015, 101, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangwal, S.; Thum, T. microRNA Therapeutics in Cardiovascular Disease Models. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 54, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinde, K.; Milligan, L.A. Primate Milk: Proximate Mechanisms and Ultimate Perspectives. Evolutionary Anthropology 2011, 20, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartol, F.; Wiley, A.; Bagnell, C. Epigenetic Programming of Porcine Endometrial Function and the Lactocrine Hypothesis. Reprod Domestic Animals 2008, 43, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorbach, C.; Capecchi, M.R.; Penninger, J.M. Evolution of the Mammary Gland from the Innate Immune System? BioEssays 2006, 28, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinde, K.; German, J.B. Food in an Evolutionary Context: Insights from Mother’s Milk. J Sci Food Agric 2012, 92, 2219–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sale, S.; Pavelic, K. Mammary Lineage Tracing: The Coming of Age. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 1577–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnegan, E.F.; Pasquinelli, A.E. MicroRNA Biogenesis: Regulating the Regulators. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2013, 48, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Ingolia, N.T.; Weissman, J.S.; Bartel, D.P. Mammalian microRNAs Predominantly Act to Decrease Target mRNA Levels. Nature 2010, 466, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krol, J.; Loedige, I.; Filipowicz, W. The Widespread Regulation of microRNA Biogenesis, Function and Decay. Nat Rev Genet 2010, 11, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reslan, O.M.; Khalil, R.A. Molecular and Vascular Targets in the Pathogenesis and Management of the Hypertension Associated with Preeclampsia. CHAMC 2010, 8, 204–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, M.; Lin, N.; Lin, Y.; Huang, H.; Xu, L. Evaluation of Chromosomal Abnormalities and Copy Number Variations in Late Trimester Pregnancy Using Cordocentesis. Aging 2020, 12, 15556–15565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, R.; Mattei, V.; Al Hashmi, M.; Tomei, S. Updates on the Current Technologies for microRNA Profiling. MIRNA 2019, 9, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoğlu, B.G. High-Throughput Approaches for MicroRNA Expression Analysis. In miRNomics: MicroRNA Biology and Computational Analysis; Yousef, M., Allmer, J., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2014; Vol. 1107, pp. 91–103; ISBN 978-1-62703-747-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.Q.; Zhao, R.C.; Morris, K.V. Profiling microRNA Expression with Microarrays. Trends in Biotechnology 2008, 26, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benes, V.; Castoldi, M. Expression Profiling of microRNA Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR, How to Use It and What Is Available. Methods 2010, 50, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnke, A.H.; Roberts, M.H.; Leeman, L.; Ma, X.; Bakhireva, L.N.; Miranda, R.C. Prenatal Opioid-Exposed Infant Extracellular miRNA Signature Obtained at Birth Predicts Severity of Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, M.P.; Looney, A.M.; Moloney, G.M.; Finder, M.; Hallberg, B.; Clarke, G.; Boylan, G.B.; Murray, D.M. Validation of Altered Umbilical Cord Blood MicroRNA Expression in Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. JAMA Neurol 2019, 76, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Roselló, J.; Loscalzo, G.; García-Lopez, E.M.; Ibañez Cabellos, J.S.; García-Gimenez, J.L.; Cañada Martínez, A.J.; Perales Marín, A. MicroRNA-185-5p: A Marker of Brain-Sparing in Foetuses with Late-Onset Growth Restriction. Epigenetics 2022, 17, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-J.; Tsai, C.-C.; Chao, H.-R.; Lee, S.-Y.; Chen, C.-C.; Li, S.-C. MicroRNAs in Umbilical Cord Blood and Development in Full-Term Newborns: A Prospective Study. Biomark Insights 2024, 19, 11772719241258017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-J.; Kuo, H.-C.; Lee, S.-Y.; Huang, L.-H.; Lin, Y.; Lin, P.-H.; Li, S.-C. MicroRNAs Serve as Prediction and Treatment-Response Biomarkers of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Promote the Differentiation of Neuronal Cells by Repressing the Apoptosis Pathway. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, D.J.P. The Origins of the Developmental Origins Theory. Journal of Internal Medicine 2007, 261, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchurevska, O.D.; Zhuk, S.I. ASSESSMENT OF CORRELATION BETWEEN MIRNAS-21-3P AND -210-3P EXPRESSION IN MATERNAL AND UMBILICAL CORD PLASMA AND FETAL WEIGHT AT BIRTH. Wiad Lek 2021, 74, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccani, M.A.; Padbury, J.F.; Lester, B.M.; Knopik, V.S.; Marsit, C.J. Placental miRNA Expression Profiles Are Associated with Measures of Infant Neurobehavioral Outcomes. Pediatr Res 2013, 74, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, G.P.; Vitsios, D.M.; Casey, S.; Looney, A.-M.; Hallberg, B.; Henshall, D.C.; Boylan, G.B.; Murray, D.M.; Mooney, C. RNA-Sequencing Analysis of Umbilical Cord Plasma microRNAs from Healthy Newborns. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boele, J.; Persson, H.; Shin, J.W.; Ishizu, Y.; Newie, I.S.; Søkilde, R.; Hawkins, S.M.; Coarfa, C.; Ikeda, K.; Takayama, K.; et al. PAPD5-Mediated 3′ Adenylation and Subsequent Degradation of miR-21 Is Disrupted in Proliferative Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 11467–11472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, T.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Miyauchi, K.; Suzuki, T.; Kashiwabara, S.; Baba, T.; Suzuki, T. Selective Stabilization of Mammalian microRNAs by 3′ Adenylation Mediated by the Cytoplasmic Poly(A) Polymerase GLD-2. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gródecka-Szwajkiewicz, D.; Ulańczyk, Z.; Zagrodnik, E.; Łuczkowska, K.; Rogińska, D.; Kawa, M.P.; Stecewicz, I.; Safranow, K.; Machaliński, B. Differential Secretion of Angiopoietic Factors and Expression of MicroRNA in Umbilical Cord Blood from Healthy Appropriate-For-Gestational-Age Preterm and Term Newborns—in Search of Biomarkers of Angiogenesis-Related Processes in Preterm Birth. IJMS 2020, 21, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, Y.; Sessa, W.C. MicroRNAs As Novel Regulators of Angiogenesis. Circulation Research 2009, 104, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.O.; Kotecha, S.J.; Kotecha, S. Respiratory Distress of the Term Newborn Infant. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 2013, 14, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, X. Association of Umbilical Cord Blood miR-375 with Neonatal Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Adverse Neonatal Outcomes in Premature Infants. Acta Biochim Pol 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practice Bulletin, No. 134: Fetal Growth Restriction. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2013, 121, 1122–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.L.; Huppi, P.S.; Mallard, C. The Consequences of Fetal Growth Restriction on Brain Structure and Neurodevelopmental Outcome. The Journal of Physiology 2016, 594, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quezada, S.; Castillo-Melendez, M.; Walker, D.W.; Tolcos, M. Development of the Cerebral Cortex and the Effect of the Intrauterine Environment. The Journal of Physiology 2018, 596, 5665–5674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triunfo, S.; Crispi, F.; Gratacos, E.; Figueras, F. Prediction of Delivery of Small-for-gestational-age Neonates and Adverse Perinatal Outcome by Fetoplacental Doppler at 37 Weeks’ Gestation. Ultrasound in Obstet & Gyne 2017, 49, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Roselló, J.; Khalil, A.; Fornés-Ferrer, V.; Perales-Marín, A. Accuracy of the Fetal Cerebroplacental Ratio for the Detection of Intrapartum Compromise in Nonsmall Fetuses. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 2019, 32, 2842–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, L.N.; Alsolai, A.A.; Greer, R.M.; Kumar, S. Cerebroplacental Ratio Thresholds Measured within 2 Weeks before Birth and Risk of Cesarean Section for Intrapartum Fetal Compromise and Adverse Neonatal Outcome. Ultrasound in Obstet & Gyne 2018, 52, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, L.N.; Alsolai, A.A.; Greer, R.M.; Kumar, S. Prelabor Screening for Intrapartum Fetal Compromise in Low-risk Pregnancies at Term: Cerebroplacental Ratio and Placental Growth Factor. Ultrasound in Obstet & Gyne 2018, 52, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carthew, R.W.; Sontheimer, E.J. Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 2009, 136, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Target Recognition and Regulatory Functions. Cell 2009, 136, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichihara, A.; Jinnin, M.; Yamane, K.; Fujisawa, A.; Sakai, K.; Masuguchi, S.; Fukushima, S.; Maruo, K.; Ihn, H. microRNA-Mediated Keratinocyte Hyperproliferation in Psoriasis Vulgaris. British Journal of Dermatology 2011, 165, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Roselló, J.; García-Giménez, J.L.; Martinez Priego, L.; González-Rodríguez, D.; Mena-Mollá, S.; Maquieira Catalá, A.; Loscalzo, G.; Buongiorno, S.; Jakaite, V.; Cañada Martínez, A.J.; et al. MicroRNA-148b-3p and MicroRNA-25-3p Are Overexpressed in Fetuses with Late-Onset Fetal Growth Restriction. Fetal Diagn Ther 2020, 47, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, T.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Li, P.; Qin, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, B.; Ding, F.; Gu, X.; Zhou, S. miR-148b-3p Promotes Migration of Schwann Cells by Targeting Cullin-Associated and Neddylation-Dissociated 1. Neural Regen Res 2016, 11, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Roselló, J.; Loscalzo, G.; García-Lopez, E.M.; García-Gimenez, J.L.; Perales-Marín, A. MicroRNA-132 Is Overexpressed in Fetuses with Late-onset Fetal Growth Restriction. Health Science Reports 2022, 5, e558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loscalzo, G.; Scheel, J.; Ibañez-Cabellos, J.S.; García-Lopez, E.; Gupta, S.; García-Gimenez, J.L.; Mena-Mollá, S.; Perales-Marín, A.; Morales-Roselló, J. Overexpression of microRNAs miR-25-3p, miR-185-5p and miR-132-3p in Late Onset Fetal Growth Restriction, Validation of Results and Study of the Biochemical Pathways Involved. IJMS 2021, 23, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Jimenez, R.; Borrero González, C.; García-Mejido, J.A.; Fernández-Palacín, A.; Robles, A.; Sosa, F.; Sainz-Bueno, J.A. Assessment of Late On-Set Fetal Growth Restriction Using SMI (Superb Microvascular Imaging) Doppler. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2023, 13, 4305–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, L.M.; DiPietro, J.A.; Elko, A.; Velez, M. Infant Autonomic Functioning and Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2010, 109, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, A.W.; Vestermark, V.; Kjærbye-Thygesen, A.; Eckhardt, M.; Kesmodel, U.S. Maternal Opioid Use during Pregnancy and the Risk of Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome in the Offspring. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, K.; Murphy-Oikonen, J. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 2468–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudak, M.L.; Tan, R.C.; THE COMMITTEE ON DRUGS. ; THE COMMITTEE ON FETUS AND NEWBORN.; Frattarelli, D.A.C.; Galinkin, J.L.; Green, T.P.; Neville, K.A.; Paul, I.M.; Van Den Anker, J.N.; et al. Neonatal Drug Withdrawal. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e540–e560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, V.; Angelici, L.; Nordio, F.; Bollati, V.; Fossati, S.; Frascati, F.; Tinaglia, V.; Bertazzi, P.A.; Battaglia, C.; Baccarelli, A.A. Integrative Analysis of miRNA and Inflammatory Gene Expression After Acute Particulate Matter Exposure. Toxicological Sciences 2013, 132, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, G.; Guo, C.; Zhao, X.; Shen, D.; Yang, N. MiR-128-3p Mediates TNF-α-Induced Inflammatory Responses by Regulating Sirt1 Expression in Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2020, 521, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceolotto, G.; Giannella, A.; Albiero, M.; Kuppusamy, M.; Radu, C.; Simioni, P.; Garlaschelli, K.; Baragetti, A.; Catapano, A.L.; Iori, E.; et al. miR-30c-5p Regulates Macrophage-Mediated Inflammation and pro-Atherosclerosis Pathways. Cardiovascular Research 2017, 113, 1627–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankaran, S. Neonatal Encephalopathy: Treatment with Hypothermia. Journal of Neurotrauma 2009, 26, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, A.; Takei, Y.; Cady, E.B.; Wyatt, J.S.; Penrice, J.; Edwards, A.D.; Peebles, D.; Wylezinska, M.; Owen-Reece, H.; Kirkbride, V.; et al. Delayed (“Secondary”) Cerebral Energy Failure after Acute Hypoxia-Ischemia in the Newborn Piglet: Continuous 48-Hour Studies by Phosphorus Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Pediatr Res 1994, 36, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.E.; Gunn, A.; Gluckman, P.D. Time Course of Intracellular Edema and Epileptiform Activity Following Prenatal Cerebral Ischemia in Sheep. Stroke 1991, 22, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, D.V.; Strohm, B.; Edwards, A.D.; Dyet, L.; Halliday, H.L.; Juszczak, E.; Kapellou, O.; Levene, M.; Marlow, N.; Porter, E.; et al. Moderate Hypothermia to Treat Perinatal Asphyxial Encephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2009, 361, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looney, A.-M.; Walsh, B.H.; Moloney, G.; Grenham, S.; Fagan, A.; O’Keeffe, G.W.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G.; Boylan, G.B.; et al. Downregulation of Umbilical Cord Blood Levels of miR-374a in Neonatal Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy. The Journal of Pediatrics 2015, 167, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Looney, A.M.; Ahearne, C.E.; Hallberg, B.; Boylan, G.B.; Murray, D.M. Downstream mRNA Target Analysis in Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischaemic Encephalopathy Identifies Novel Marker of Severe Injury: A Proof of Concept Paper. Mol Neurobiol 2017, 54, 8420–8428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looney, A.M.; O’Sullivan, M.P.; Ahearne, C.E.; Finder, M.; Felderhoff-Mueser, U.; Boylan, G.B.; Hallberg, B.; Murray, D.M. Altered Expression of Umbilical Cord Blood Levels of miR-181b and Its Downstream Target mUCH-L1 in Infants with Moderate and Severe Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischaemic Encephalopathy. Mol Neurobiol 2019, 56, 3657–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, I.; Heisinger, T.; Hammerl, M.; Huber, E.; Urbanek, M.; Kiechl-Kohlendorfer, U.; Griesmaier, E.; Posod, A. MicroRNA Expression Profiles as Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers of Perinatal Asphyxia and Hypoxic-Ischaemic Encephalopathy. Neonatology 2022, 119, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Oza, S.; Hogan, D.; Perin, J.; Rudan, I.; Lawn, J.E.; Cousens, S.; Mathers, C.; Black, R.E. Global, Regional, and National Causes of Child Mortality in 2000–13, with Projections to Inform Post-2015 Priorities: An Updated Systematic Analysis. The Lancet 2015, 385, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, L.M.; Mithal, L.B.; Mestan, K.; Wang, V.; Mangold, K.A.; Freedman, A.; Das, S. Umbilical Cord miRNAs to Predict Neonatal Early Onset Sepsis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Li, J.; Jiang, Z. MSCs Inhibits the Angiogenesis of HUVECs through the miR-211/Prox1 Pathway. The Journal of Biochemistry 2019, 166, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Tang, Q.; Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Wu, Z.; Han, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, B.; Shang, Y.; Yang, H. Identification of miRNA Expression Profile in Middle Ear Cholesteatoma Using Small RNA-Sequencing. BMC Med Genomics 2024, 17, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhao, L.; Fan, Y.; Liao, L.; Ma, P.X.; Xiao, G.; Chen, D. The microRNAs miR-204 and miR-211 Maintain Joint Homeostasis and Protect against Osteoarthritis Progression. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Quan, P.; Si, Y.; Liu, F.; Fan, Y.; Ding, F.; Sun, L.; Liu, H.; Huang, S.; Sun, L.; et al. The microRNA-211-5p/P2RX7/ERK/GPX4 Axis Regulates Epilepsy-Associated Neuronal Ferroptosis and Oxidative Stress. J Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareifar, P.; Ahmed, H.M.; Ghaderi, P.; Farahmand, Y.; Rahnama, N.; Esbati, R.; Moradi, A.; Yazdani, O.; Sadeghipour, Y. miR-142-3p/5p Role in Cancer: From Epigenetic Regulation to Immunomodulation. Cell Biochemistry & Function 2024, 42, e3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidinger, S.; Novak, N. Atopic Dermatitis. The Lancet 2016, 387, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, R.; Woodfolk, J.A. Skin Barrier Defects in Atopic Dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2014, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, E.; Inoue, Y.; Ochiai, S.; Eguchi, A.; Nakano, T.; Yamaide, F.; Hasegawa, S.; Kojima, H.; Suzuki, H.; Mori, C.; et al. Hsa-Mir-144-3p Expression Is Increased in Umbilical Cord Serum of Infants with Atopic Dermatitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2019, 143, 447–450.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaprasad, U.; Kinker, K.G.; Ericksen, M.B.; Lindsey, M.; Gibson, A.M.; Bass, S.A.; Hershey, N.S.; Deng, J.; Medvedovic, M.; Khurana Hershey, G.K. SERPINB3/B4 Contributes to Early Inflammation and Barrier Dysfunction in an Experimental Murine Model of Atopic Dermatitis. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2015, 135, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Onis, M.; Blössner, M.; Borghi, E. Global Prevalence and Trends of Overweight and Obesity among Preschool Children. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2010, 92, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncuoğlu Güngör, N. Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents. Jcrpe 2014, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatani, R.; Yoshioka, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Watanabe, M.; Hisada, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Sakurai, K.; Takatani, T.; Shimojo, N.; Hamada, H.; et al. Investigation of Umbilical Cord Serum miRNAs Associated with Childhood Obesity: A Pilot Study from a Birth Cohort Study. J of Diabetes Invest 2022, 13, 1740–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, M.; Holding, C. Human Embryonic Genes Re-Expressed in Cancer Cells. Oncogene 2001, 20, 8085–8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Patel, S.; Mirza, S.; Rawal, R.M. Unravelling the Link between Embryogenesis and Cancer Metastasis. Gene 2018, 642, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Wendl, M.C.; Wyczalkowski, M.A.; Bailey, M.H.; Li, Y.; Ding, L. Moving Pan-Cancer Studies from Basic Research toward the Clinic. Nat Cancer 2021, 2, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, C.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zou, X.; Xia, T.; Geng, X.; Liu, P.; Cheng, W.; Zhu, W. Diagnostic Value of Oncofetal miRNAs in Cancers: A Comprehensive Analysis of Circulating miRNAs in Pan-Cancers and UCB. CBM 2021, 32, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenenbaum-Gavish, K.; Hod, M. Impact of Maternal Obesity on Fetal Health. Fetal Diagn Ther 2013, 34, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, N.; Parry, S.; Elovitz, M.A.; Durnwald, C.P. The Effect of an Obesogenic Maternal Environment on Expression of Fetal Umbilical Cord Blood miRNA. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 22, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juracek, J.; Piler, P.; Janku, P.; Radova, L.; Slaby, O. Identification of microRNA Signatures in Umbilical Cord Blood Associated with Maternal Characteristics. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Wang, Y.; Quan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Z. Maternal Obesity Alters C19MC microRNAs Expression Profile in Fetal Umbilical Cord Blood. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2020, 17, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Prieto, D.M.; Ospina-Prieto, S.; Chaiwangyen, W.; Schoenleben, M.; Markert, U.R. Pregnancy-Associated miRNA-Clusters. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2013, 97, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hromadnikova, I.; Dvorakova, L.; Kotlabova, K.; Krofta, L. The Prediction of Gestational Hypertension, Preeclampsia and Fetal Growth Restriction via the First Trimester Screening of Plasma Exosomal C19MC microRNAs. IJMS 2019, 20, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondracka, A.; Kondracki, B.; Jaszczuk, I.; Staniczek, J.; Kwasniewski, W.; Filip, A.; Kwasniewska, A. Diagnostic Potential of microRNAs Mi 517 and Mi 526 as Biomarkers in the Detection of Hypertension and Preeclampsia in the First Trimester. Ginekol Pol, 9380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Li, C.; Qi, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wu, J.X.; Hu, Y.N.; Wu, D.M.; Liu, Y.; Yan, T.T.; et al. Downregulation of miR-181a Upregulates Sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) and Improves Hepatic Insulin Sensitivity. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 2032–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippo, M.R.; Olivieri, F.; Monsurrò, V.; Prattichizzo, F.; Albertini, M.C.; Procopio, A.D. MitomiRs in Human Inflamm-Aging: A Hypothesis Involving miR-181a, miR-34a and miR-146a. Experimental Gerontology 2014, 56, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurylowicz, A.; Owczarz, M.; Polosak, J.; Jonas, M.I.; Lisik, W.; Jonas, M.; Chmura, A.; Puzianowska-Kuznicka, M. SIRT1 and SIRT7 Expression in Adipose Tissues of Obese and Normal-Weight Individuals Is Regulated by microRNAs but Not by Methylation Status. Int J Obes 2016, 40, 1635–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcondes, J.P.D.C.; Andrade, P.F.B.; Sávio, A.L.V.; Silveira, M.A.D.; Rudge, M.V.C.; Salvadori, D.M.F. BCL2 and miR-181a Transcriptional Alterations in Umbilical-Cord Blood Cells Can Be Putative Biomarkers for Obesity. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 2018, 836, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasca, D.; Romero, M.; Diaz, A.; Garcia, D.; Thaller, S.; Blomberg, B.B. B Cells with a Senescent-Associated Secretory Phenotype Accumulate in the Adipose Tissue of Individuals with Obesity. IJMS 2021, 22, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranke, P.; Failace, R.R.; Allebrandt, W.F.; Steibel, G.; Schmidt, F.; Nardi, N.B. Hematologic and Immunophenotypic Characterization of Human Umbilical Cord Blood. Acta Haematol 2001, 105, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Liu, L.; Lei, Y.; Hu, Y. MiRNA-142-3p Increases Radiosensitivity in Human Umbilical Cord Blood Mononuclear Cells by Inhibiting the Expression of CD133. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 5674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazi, F.; Rosa, A.; Fatica, A.; Gelmetti, V.; De Marchis, M.L.; Nervi, C.; Bozzoni, I. A Minicircuitry Comprised of MicroRNA-223 and Transcription Factors NFI-A and C/EBPα Regulates Human Granulopoiesis. Cell 2005, 123, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Mackowiak, B.; Feng, D.; Lu, H.; Guan, Y.; Lehner, T.; Pan, H.; Wang, X.W.; He, Y.; Gao, B. MicroRNA-223 Attenuates Hepatocarcinogenesis by Blocking Hypoxia-Driven Angiogenesis and Immunosuppression. Gut 2023, 72, 1942–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkerova, M.; Vasikova, A.; Belickova, M.; Bruchova, H. MicroRNA Expression Profiles in Umbilical Cord Blood Cell Lineages. Stem Cells and Development 2010, 19, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Liang, H.; Yu, M.; Liao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Wang, T.; et al. Oncogenic miR-19a and miR-19b Co-Regulate Tumor Suppressor MTUS1 to Promote Cell Proliferation and Migration in Lung Cancer. Protein Cell 2017, 8, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Nie, Y.; Mi, Q.; Zhao, S. Ovarian Tumor-Associated microRNA-20a Decreases Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity by Downregulating MICA/B Expression. Cell Mol Immunol 2014, 11, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchida, A.; Ohno, S.; Wu, W.; Borjigin, N.; Fujita, K.; Aoki, T.; Ueda, S.; Takanashi, M.; Kuroda, M. miR-92 Is a Key Oncogenic Component of the miR-17–92 Cluster in Colon Cancer. Cancer Science 2011, 102, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimony, S.; Stahl, M.; Stone, R.M. Acute Myeloid Leukemia: 2023 Update on Diagnosis, Risk-stratification, and Management. American J Hematol 2023, 98, 502–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, M.; Pelosi, E.; Castelli, G.; Cerio, A.M.; D′angiò, A.; Porretti, L.; Rebulla, P.; Pavesi, L.; Russo, G.; Giordano, A.; et al. A miRNA Signature in Human Cord Blood Stem and Progenitor Cells as Potential Biomarker of Specific Acute Myeloid Leukemia Subtypes: miRNA PROFILE IN HEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELLS. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 230, 1770–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, S.; Sanderson, M.P.; Stoeck, A.; Altevogt, P. Exosomes: From Biogenesis and Secretion to Biological Function. Immunology Letters 2006, 107, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camussi, G.; Deregibus, M.C.; Bruno, S.; Cantaluppi, V.; Biancone, L. Exosomes/Microvesicles as a Mechanism of Cell-to-Cell Communication. Kidney International 2010, 78, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- György, B.; Módos, K.; Pállinger, É.; Pálóczi, K.; Pásztói, M.; Misják, P.; Deli, M.A.; Sipos, Á.; Szalai, A.; Voszka, I.; et al. Detection and Isolation of Cell-Derived Microparticles Are Compromised by Protein Complexes Resulting from Shared Biophysical Parameters. Blood 2011, 117, e39–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydrychowicz, M.; Kolecka-Bednarczyk, A.; Madejczyk, M.; Yasar, S.; Dworacki, G. Exosomes – Structure, Biogenesis and Biological Role in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Scand J Immunol 2015, 81, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Février, B.; Raposo, G. Exosomes: Endosomal-Derived Vesicles Shipping Extracellular Messages. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2004, 16, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Ashman, K.; Sobrevia, L.; Mitchell, M.D.; Rice, G.E. Hypoxia-Induced Changes in the Bioactivity of Cytotrophoblast-Derived Exosomes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkach, M.; Théry, C. Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Cell 2016, 164, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocucci, E.; Racchetti, G.; Meldolesi, J. Shedding Microvesicles: Artefacts No More. Trends in Cell Biology 2009, 19, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, S.; Rupp, C.; Stoeck, A.; Runz, S.; Fogel, M.; Lugert, S.; Hager, H.-D.; Abdel-Bakky, M.S.; Gutwein, P.; Altevogt, P. CD24 Is a Marker of Exosomes Secreted into Urine and Amniotic Fluid. Kidney International 2007, 72, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torregrosa Paredes, P.; Gutzeit, C.; Johansson, S.; Admyre, C.; Stenius, F.; Alm, J.; Scheynius, A.; Gabrielsson, S. Differences in Exosome Populations in Human Breast Milk in Relation to Allergic Sensitization and Lifestyle. Allergy 2014, 69, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caby, M.-P.; Lankar, D.; Vincendeau-Scherrer, C.; Raposo, G.; Bonnerot, C. Exosomal-like Vesicles Are Present in Human Blood Plasma. International Immunology 2005, 17, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lässer, C.; Seyed Alikhani, V.; Ekström, K.; Eldh, M.; Torregrosa Paredes, P.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Gabrielsson, S.; Lötvall, J.; Valadi, H. Human Saliva, Plasma and Breast Milk Exosomes Contain RNA: Uptake by Macrophages. J Transl Med 2011, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisitkun, T.; Shen, R.-F.; Knepper, M.A. Identification and Proteomic Profiling of Exosomes in Human Urine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 13368–13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, J.-L.; Métayer, S.; Belghazi, M.; Dacheux, F.; Dacheux, J.-L. Identification, Proteomic Profiling, and Origin of Ram Epididymal Fluid Exosome-Like Vesicles1. Biology of Reproduction 2005, 72, 1452–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Tang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D.; Li, J.; Zhou, C.; Lu, X.; Yuan, Y. Comparative Profiling of Exosomal miRNAs in Human Adult Peripheral and Umbilical Cord Blood Plasma by Deep Sequencing. Epigenomics 2020, 12, 825–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha E Rocha, K.; Ying, W.; Olefsky, J.M. Exosome-Mediated Impact on Systemic Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2024, 86, 225–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.W.; Sinkey, R.; Rajapreyar, I.; Tita, A.T.N.; Oparil, S. Preeclampsia—Pathophysiology and Clinical Presentations. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020, 76, 1690–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xueya, Z.; Yamei, L.; Sha, C.; Dan, C.; Hong, S.; Xingyu, Y.; Weiwei, C. Exosomal Encapsulation of miR-125a-5p Inhibited Trophoblast Cell Migration and Proliferation by Regulating the Expression of VEGFA in Preeclampsia. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2020, 525, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Yan, P.; Zhang, H. Human Umbilical Cord Blood Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Exosomal microRNA-503-3p Inhibits Progression of Human Endometrial Cancer Cells through Downregulating MEST. Cancer Gene Ther 2022, 29, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Rao, S.-S.; Wang, Z.-X.; Cao, J.; Tan, Y.-J.; Luo, J.; Li, H.-M.; Zhang, W.-S.; Chen, C.-Y.; Xie, H. Exosomes from Human Umbilical Cord Blood Accelerate Cutaneous Wound Healing through miR-21-3p-Mediated Promotion of Angiogenesis and Fibroblast Function. Theranostics 2018, 8, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).