Submitted:

12 August 2024

Posted:

14 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

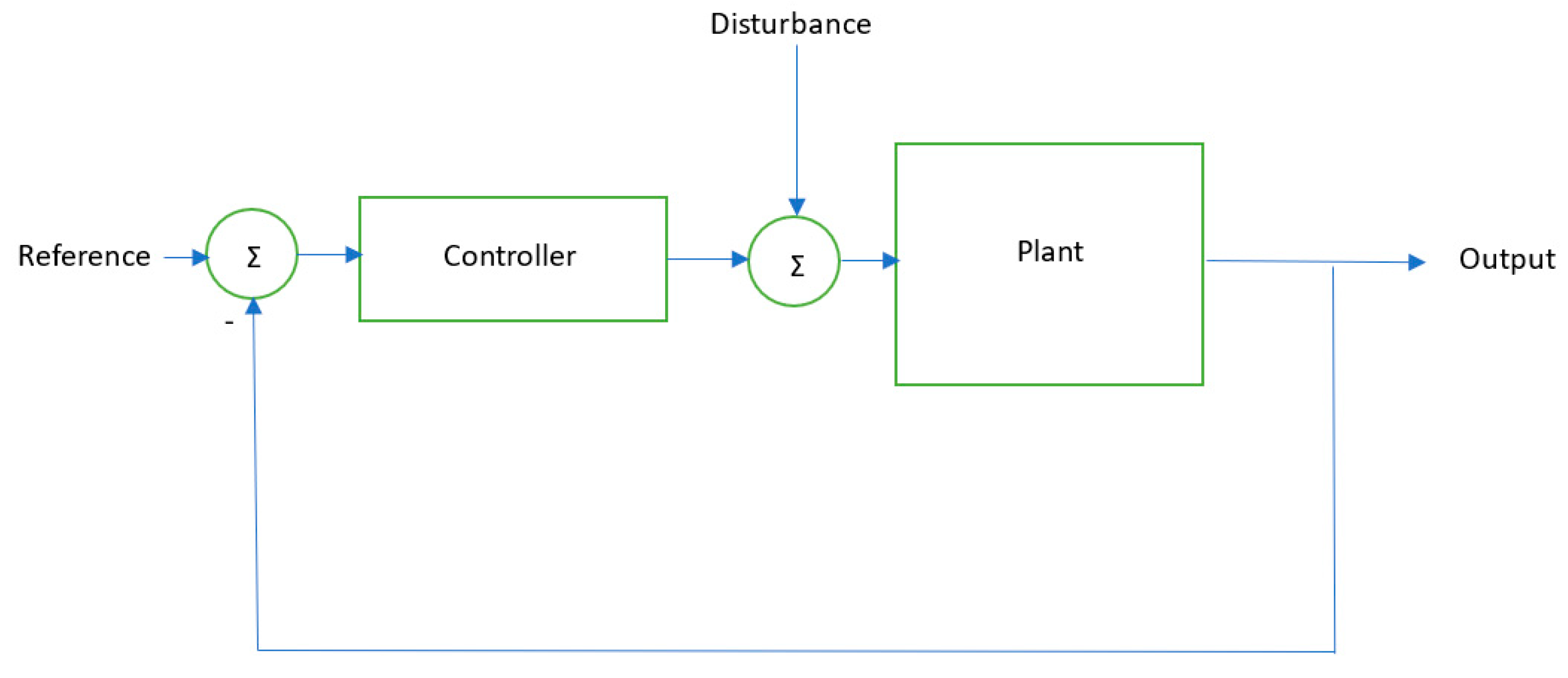

1.1. Automatic Control Concepts

1.2. Intelligent Control Systems

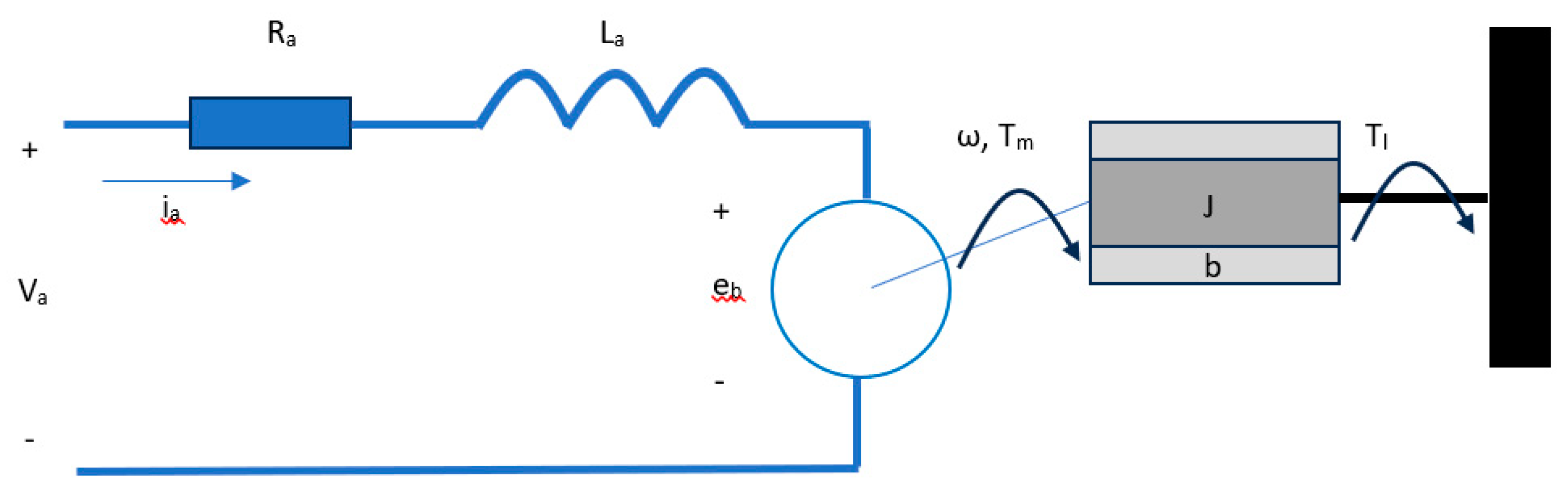

1.3. DC Motor Control

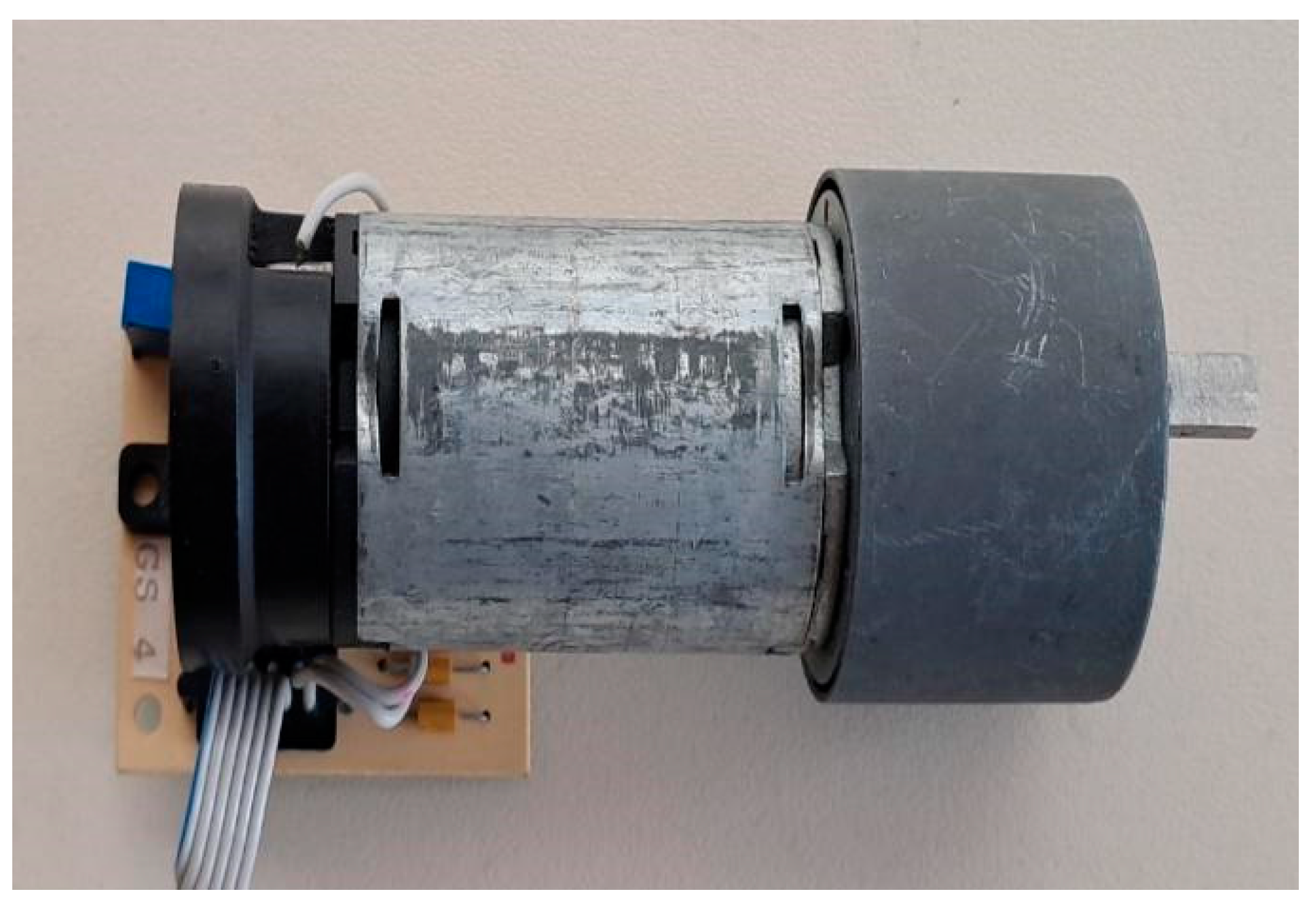

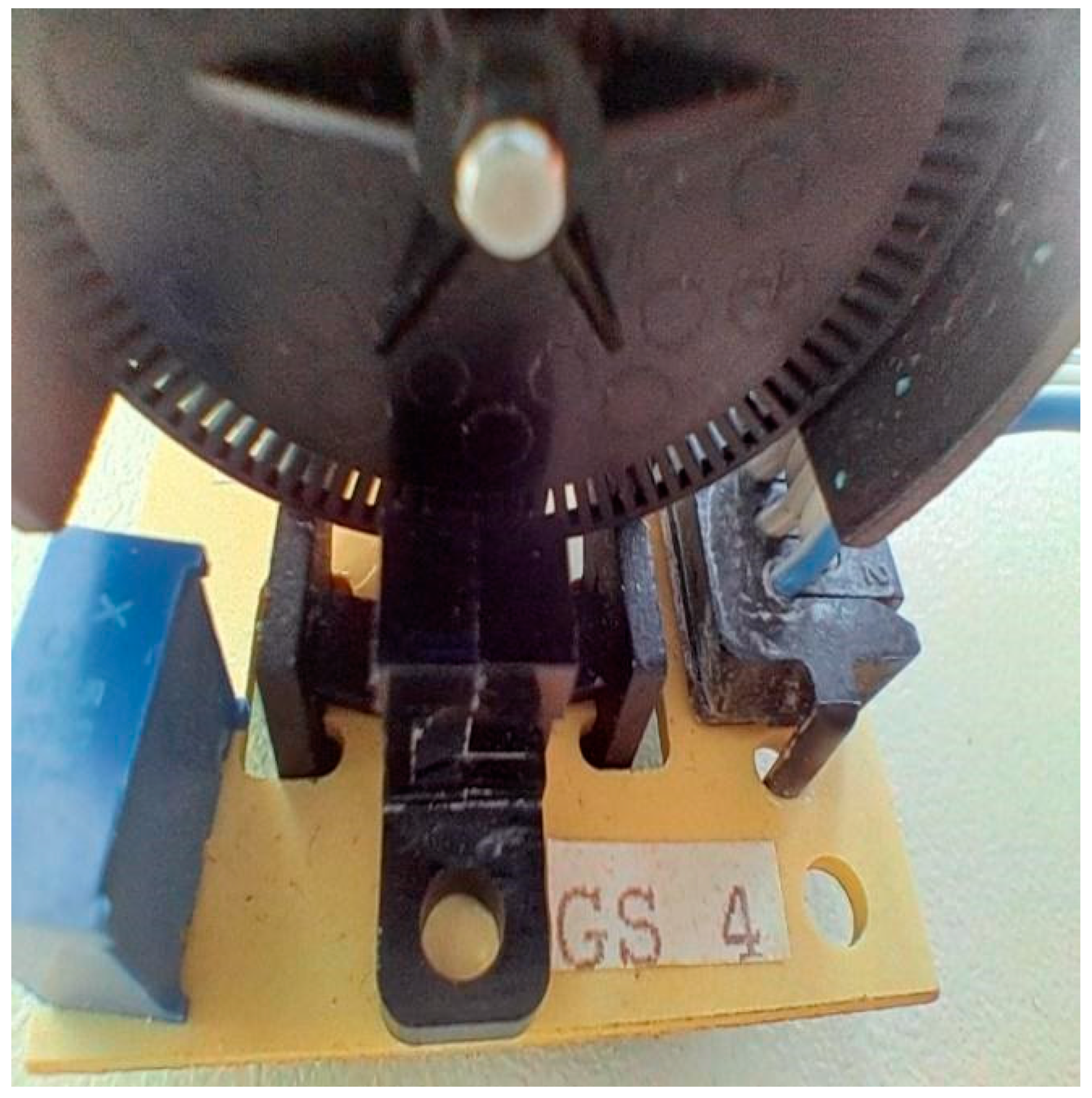

2. Materials and Methods

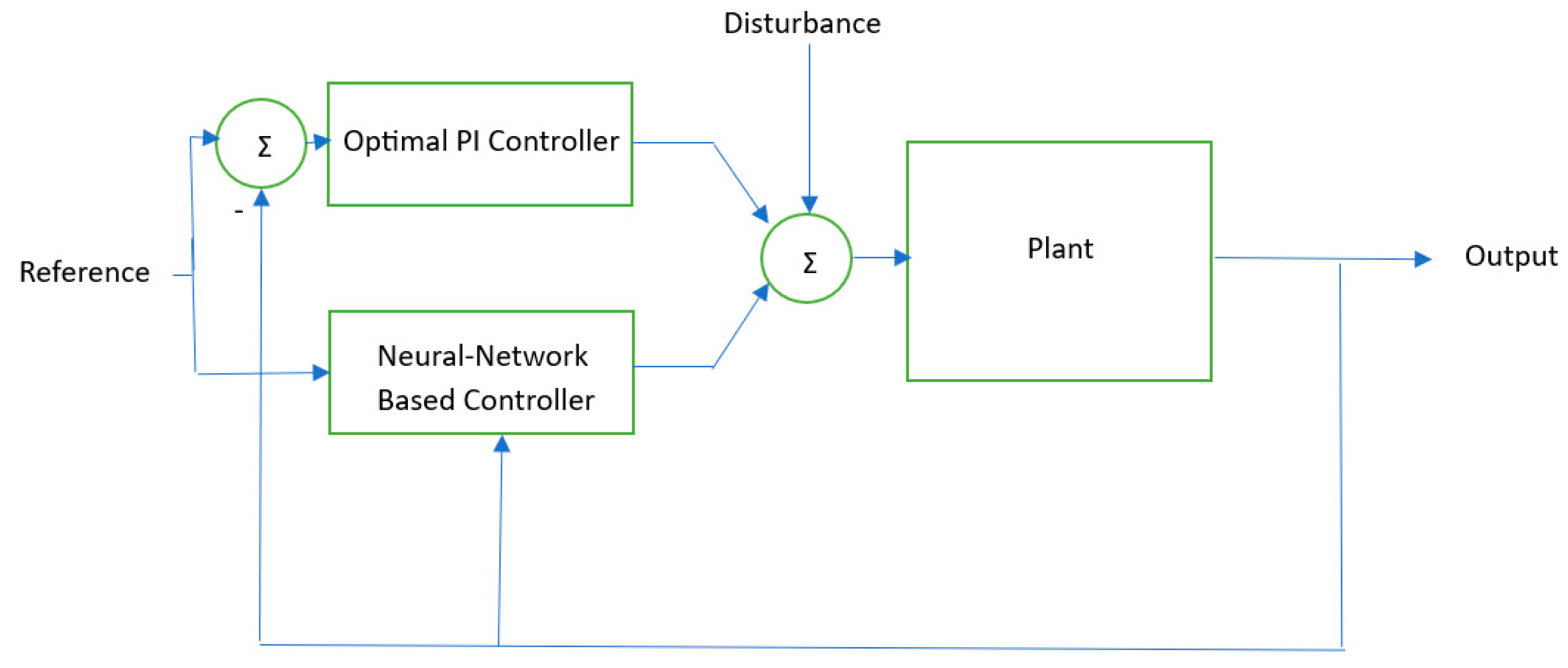

2.1. Proposed System

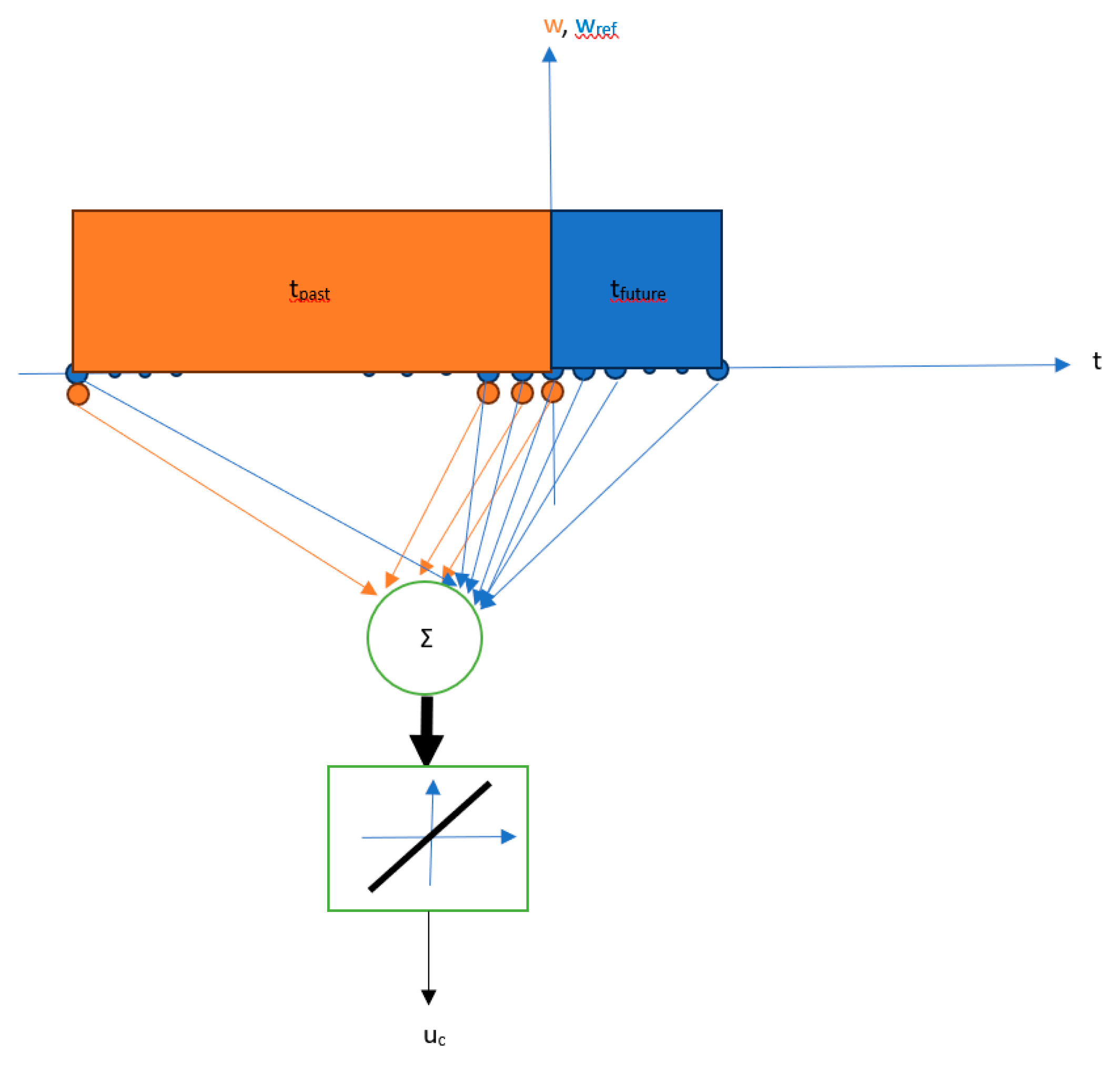

2.2. Past and Future Windows

2.3. Training Neural-Networks with PSO

2.4. Discretization and Implementation of System

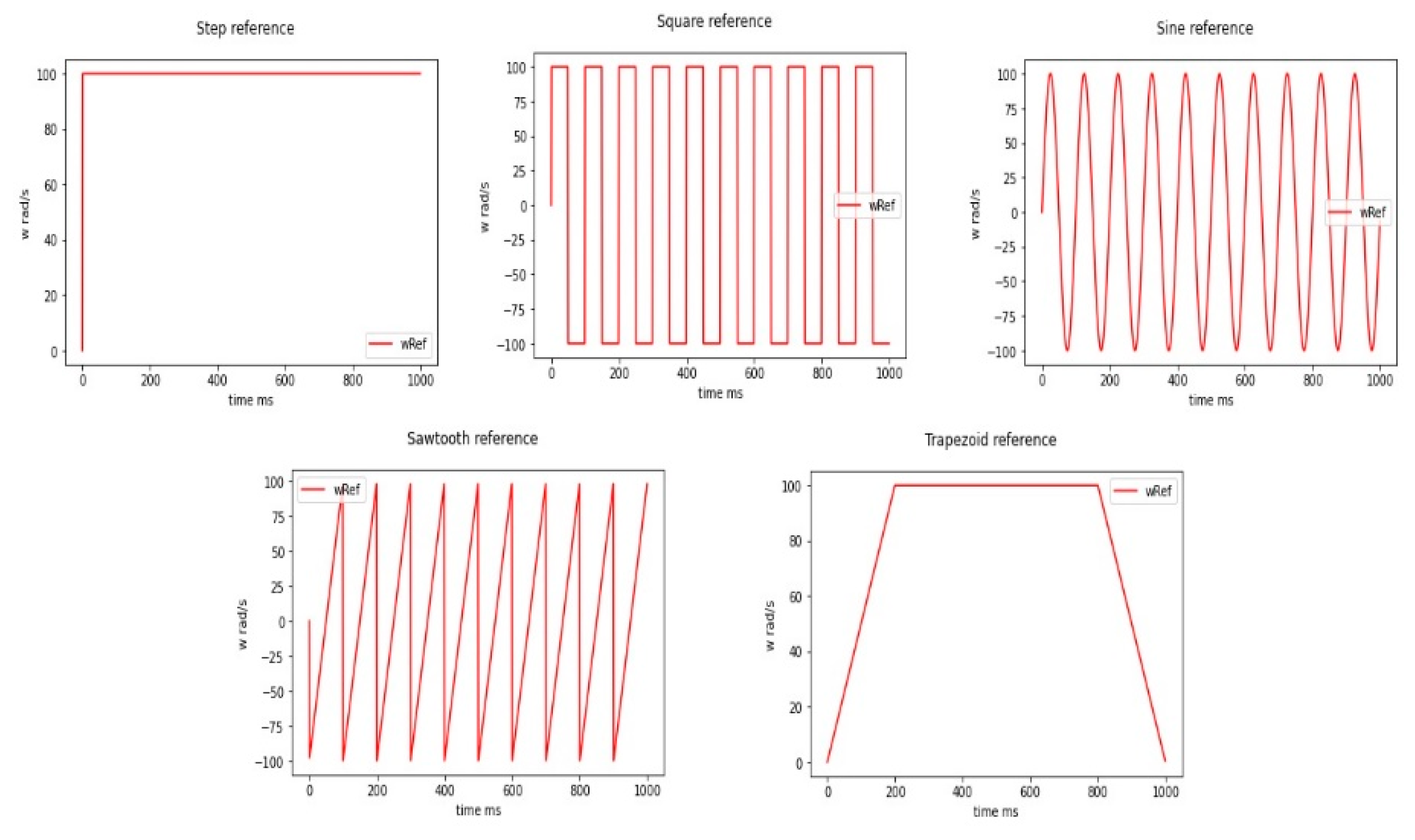

3. Results

| Signal Number | Type | Amplitude (rad/s) | Frequency (Hz) | Acc. Time (ms) | Dec. Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | step | 100 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | square | 100 | 2 | NA | NA |

| 3 | square | 100 | 3 | NA | NA |

| 4 | square | 100 | 4 | NA | NA |

| 5 | square | 100 | 5 | NA | NA |

| 6 | square | 100 | 6 | NA | NA |

| 7 | square | 100 | 8 | NA | NA |

| 8 | square | 100 | 10 | NA | NA |

| 9 | trapezoid | 100 | NA | 200 | 200 |

| 10 | trapezoid | 100 | NA | 100 | 100 |

| Signal Number | Type | Amplitude (Volts) | Frequency (Hz) | Acc. Time (ms) | Dec. Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | square | 1 | 5 | NA | NA |

| 2 | square | 1 | 10 | NA | NA |

| 3 | square | 1 | 20 | NA | NA |

| 4 | square | 2 | 5 | NA | NA |

| 5 | square | 2 | 10 | NA | NA |

| 6 | square | 2 | 20 | NA | NA |

| 7 | sawtooth | 1 | 5 | NA | NA |

| 8 | sawtooth | 1 | 20 | NA | NA |

| 9 | sawtooth | 2 | 5 | NA | NA |

| 10 | sawtooth | 2 | 20 | NA | NA |

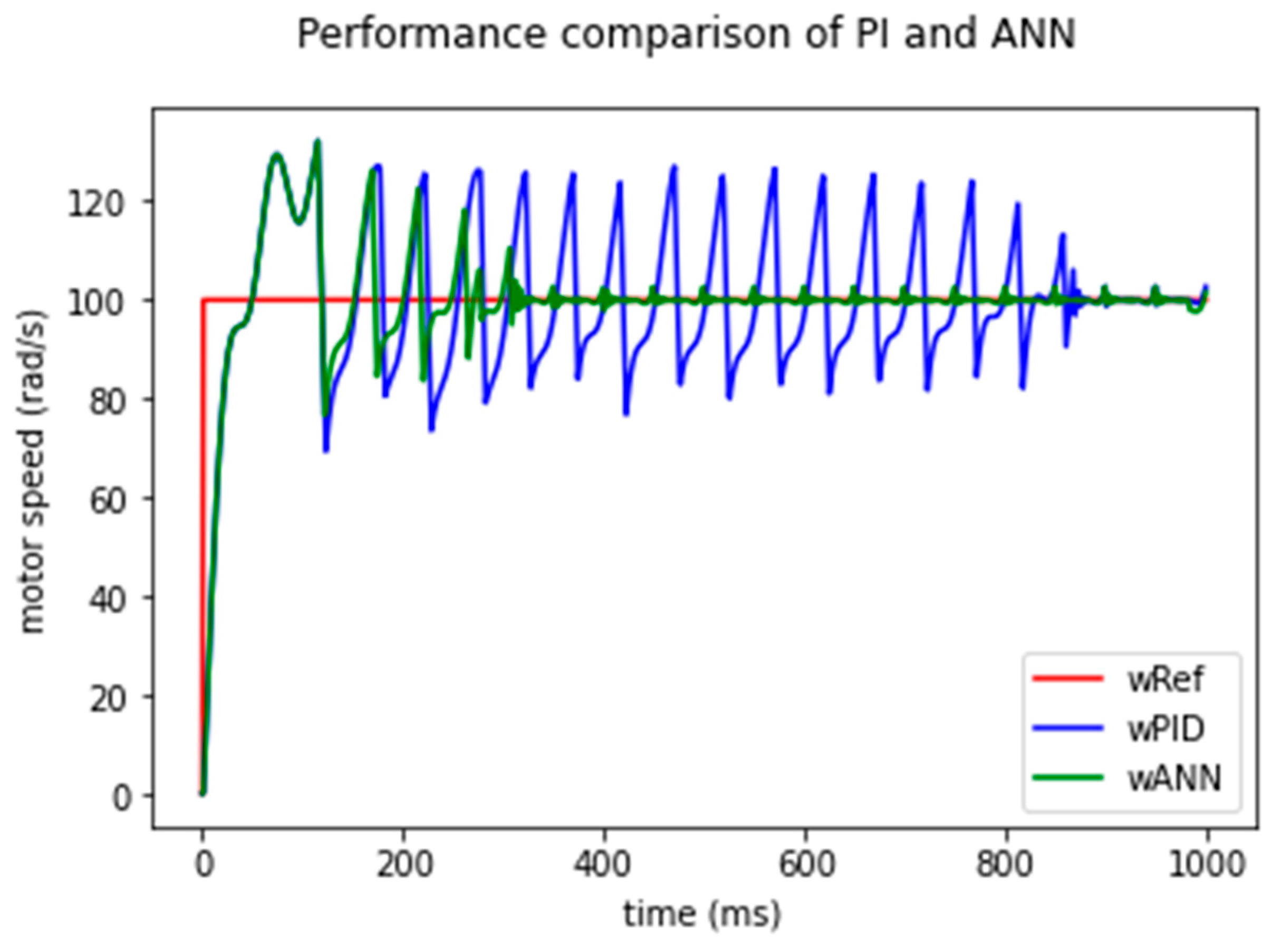

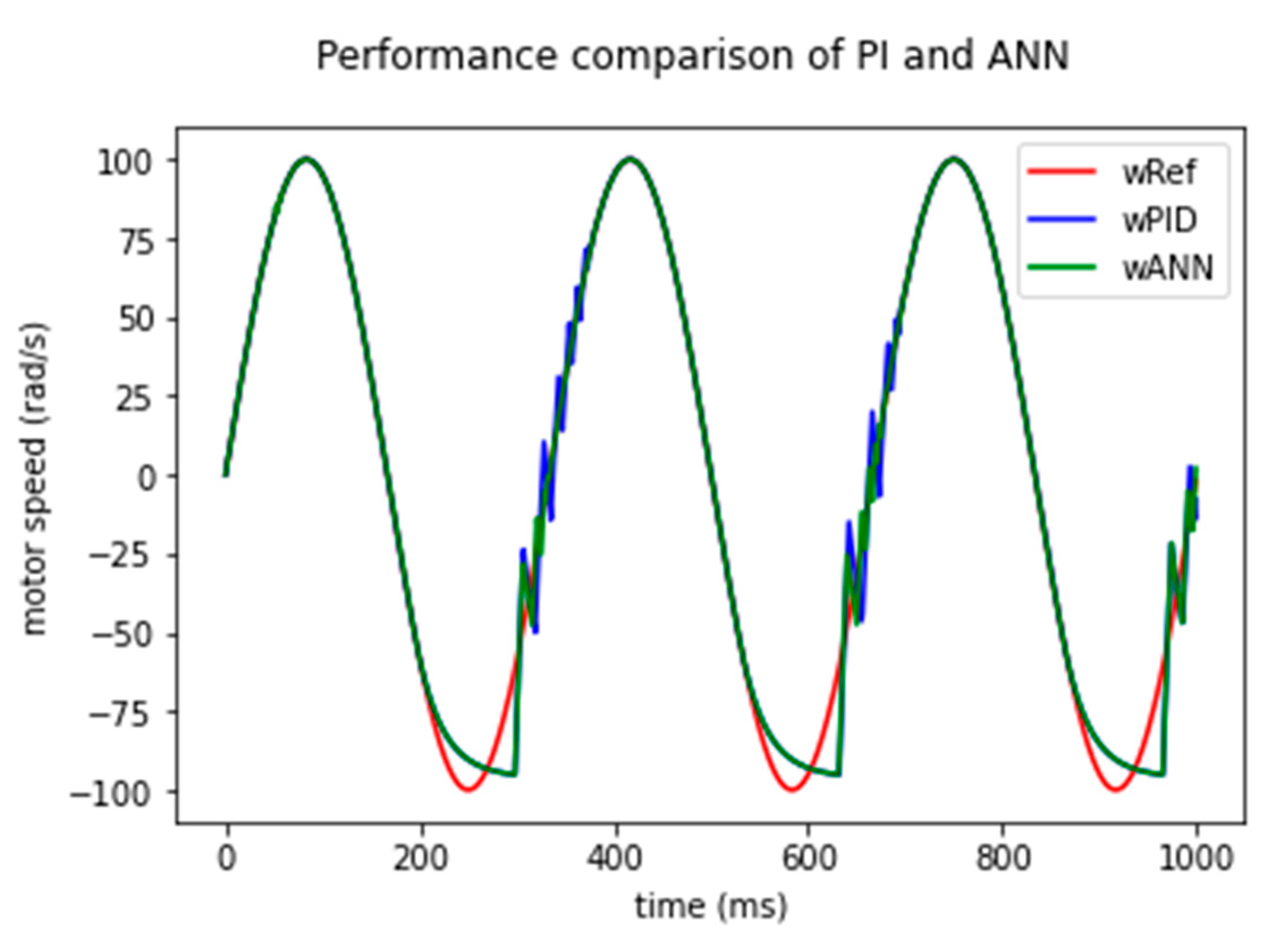

4. Discussion

4.1. Performance Issues

4.2. Implementation Issues

4.3. Ethical Issues

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ogata, K. (2020). Modern control engineering.

- Bissell, C. (2009). A history of automatic control. Springer handbook of automation, 53-69.

- Baidya, D.; Dhopte, S.; Bhattacharjee, M. Sensing system assisted novel PID controller for efficient speed control of DC motors in electric vehicles. IEEE Sensors Letters 2023, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munagala, V.K.; Jatoth, R.K. A novel approach for controlling DC motor speed using NARXnet based FOPID controller. Evolving Systems 2023, 14, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, D.; Ma'arif, A.; Maghfiroh, H.; Chotikunnan, P.; Rahmadhia, S. N. Design and application of PLC-based speed control for DC motor using PID with identification system and MATLAB tuner. International Journal of Robotics and Control Systems 2023, 3, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, S. , Izci, D., & Yilmaz, M. (2023). Efficient speed control for DC motors using novel Gazelle simplex optimizer. IEEE Access.

- Yıldırım, Ş. , Bingol, M. S., & Savas, S. (2024). Tuning PID controller parameters of the DC motor with PSO algorithm. International Review of Applied Sciences and Engineering.

- Son, J.; Kang, H.; Kang, S.H. A review on robust control of robot manipulators for future manufacturing. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing 2023, 24, 1083–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Mulyana, B.; Stankovic, V.; Cheng, S. A survey on deep reinforcement learning algorithms for robotic manipulation. Sensors 2023, 23, 3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pistone, A.; Ludovico, D.; Dal Verme, L.D.M.C.; Leggieri, S.; Canali, C.; Caldwell, D.G. Modelling and control of manipulators for inspection and maintenance in challenging environments: A literature review. Annual Reviews in Control 2024, 57, 100949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, H.; Yin, B.; Aslam, M.S.; Anjum, Z.; Rohra, A.; Wang, Y. A practical study of active disturbance rejection control for rotary flexible joint robot manipulator. Soft Computing 2023, 27, 4987–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotikunnan, P.; Chotikunnan, R. Dual design PID controller for robotic manipulator application. Journal of Robotics and Control (JRC) 2023, 4, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Tiburcio, J.F.; Estrada-Torres, J.A.; Hernández-Alvarado, R.; Montes-Martínez, J.R.; Bringas-Posadas, D.; Franco-Urquiza, E.A. ANN Enhanced Hybrid Force/Position Controller of Robot Manipulators for Fiber Placement. Robotics. 2024, 13, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-H.; Yang, C.-Y.; Lin, H.-W. Robust Adaptive-Sliding-Mode Control for Teleoperation Systems with Time-Varying Delays and Uncertainties. Robotics. 2024, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvakas, N.D.; Koumboulis, F.N.; Sigalas, J. A Two Stage Nonlinear I/O Decoupling and Partially Wireless Controller for Differential Drive Mobile Robots. Robotics. 2024, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, R.; Sousa, J.M.C.; Botto, M.A.; Gonçalves, P.J.S. A Novel Control Architecture Based on Behavior Trees for an Omni-Directional Mobile Robot. Robotics. 2023, 12, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquelanti, M.G.; Pugliese, L.F.; Silva, W.W.A.G.; Braga, R.A.S.; Monte-Mor, J.A. Comparison between an Adaptive Gain Scheduling Control Strategy and a Fuzzy Multimodel Intelligent Control Applied to the Speed Control of Non-Holonomic Robots. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Castellanos, D.; Blas-Valdez, M.; Solis-Perales, G.; Perez-Cisneros, M.A. Neural Robust Control for a Mobile Agent Leader–Follower System. Applied Sciences. 2024, 14, 5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polakovič, D.; Juhás, M.; Juhásová, B.; Červeňanská, Z. Bio-Inspired Model-Based Design and Control of Bipedal Robot. Applied Sciences. 2022, 12, 10058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K-H. ; Hsiao, Y-F.; Chen, C-C. Robust Feedback Linearization Control Design for Five-Link Human Biped Robot with Multi-Performances. Applied Sciences. 2023, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinez-Garrido, G.; Santos-Sánchez, O.-J.; Romero-Trejo, H.; García-Pérez, O. Discrete Integral Optimal Controller for Quadrotor Attitude Stabilization: Experimental Results. Applied Sciences. 2023, 13, 9293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonugür, G.; Gökçe, C.O.; Koca, Y.B.; Inci, Ş.S.; Keleş, Z. Particle swarm optimization based optimal PID controller for quadcopters. Comptes rendus de l’Acade'mie bulgare des Sciences 2021, 74, 1806–1814. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Luo, X.; Wang, X. Research and Simulation Analysis of Fuzzy Intelligent Control System Algorithm for a Servo Precision Press. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamrouni, I.; Abdul Kahar, NH.; Salem, M.; Swadi, M.; Zahroui, Y.; Kadhim, D.J.; Mohamed, F.A.; Alhuyi Nazari, M. A Comprehensive Review on the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Power System Stability, Control, and Protection: Insights and Future Directions. Applied Sciences. 2024, 14, 6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, M.; Ding, W.; Li, S.; Knoll, A. (2024). Efficient Online Planning and Robust Optimal Control for Nonholonomic Mobile Robot in Unstructured Environments. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence.

- Kumar, N.; Chaudhary, K. S. (2024). Neural network based fractional order sliding mode tracking control of nonholonomic mobile robots. Journal of Computational Analysis & Applications, 33(1).

- Freitas, J.B.S.; Marquezan, L.; de Oliveira Evald, P.J.D.; Peñaloza, E.A.G.; Cely, M.M.H. A fuzzy-based predictive PID for DC motor speed control. International Journal of Dynamics and Control 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, E., Bal, G., Öztürk, N., Bekiroglu, E., Houssein, E. H., Ocak, C., & Sharma, G. (2024). Improving speed control characteristics of PMDC motor drives using nonlinear PI control. Neural Computing and Applications, 1-12.

- Mirjalili, S.; Gandomi, A.H.; Mirjalili, S.Z.; Saremi, S.; Faris, H.; Mirjalili, S.M. Salp Swarm Algorithm: A bio-inspired optimizer for engineering design problems. Advances in engineering software 2017, 114, 163–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawane, M.K.; Malwatkar, G.M.; Deshmukh, S.P. Performance improvement of DC servo motor using sliding mode controller. Journal of Autonomous Intelligence 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerc, M. (2010). Particle swarm optimization (Vol. 93). John Wiley & Sons.

- Thomas, G. B. , Weir, M. D., & Hass, J. (2010). Thomas' Calculus: Multivariable.

| Signal Number | Type | Amplitude (rad/s) | Frequency (Hz) | Acc. Time (ms) | Dec. Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | step | 50 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | step | 70 | NA | NA | NA |

| 3 | step | 90 | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | step | 100 | NA | NA | NA |

| 5 | sine | 50 | 2 | NA | NA |

| 6 | sine | 50 | 3 | NA | NA |

| 7 | sine | 50 | 5 | NA | NA |

| 8 | sine | 100 | 2 | NA | NA |

| 9 | sine | 100 | 3 | NA | NA |

| 10 | sine | 100 | 5 | NA | NA |

| Signal Number | Type | Amplitude (Volts) | Frequency (Hz) | Acc. Time (ms) | Dec. Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | step | 1 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | step | 1,5 | NA | NA | NA |

| 3 | step | 2 | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | step | 3 | NA | NA | NA |

| 5 | sine | 1 | 5 | NA | NA |

| 6 | sine | 1 | 20 | NA | NA |

| 7 | sine | 2 | 5 | NA | NA |

| 8 | sine | 2 | 20 | NA | NA |

| 9 | sine | 3 | 5 | NA | NA |

| 10 | sine | 3 | 20 | NA | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).