Submitted:

12 August 2024

Posted:

13 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

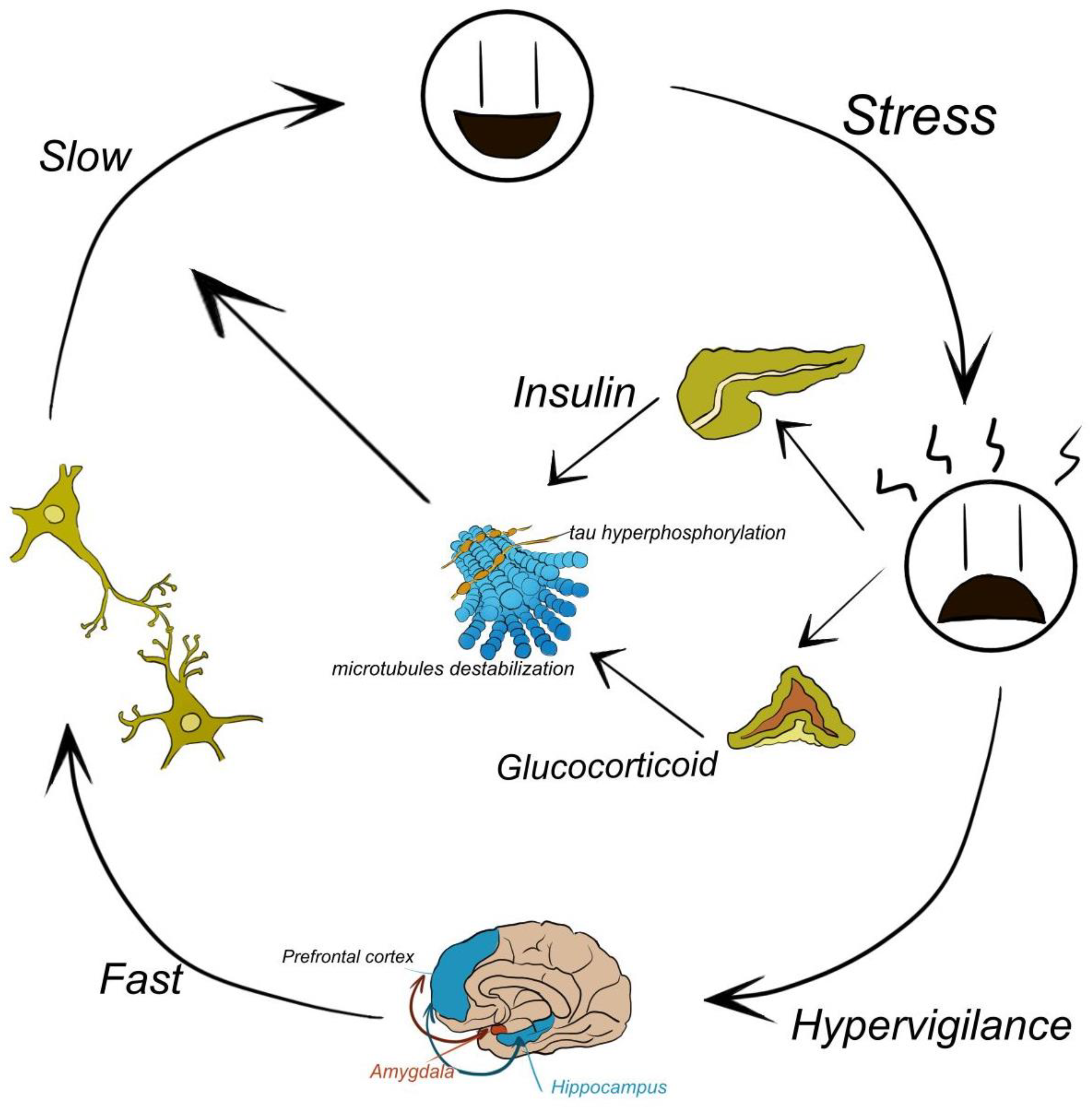

1. Introduction

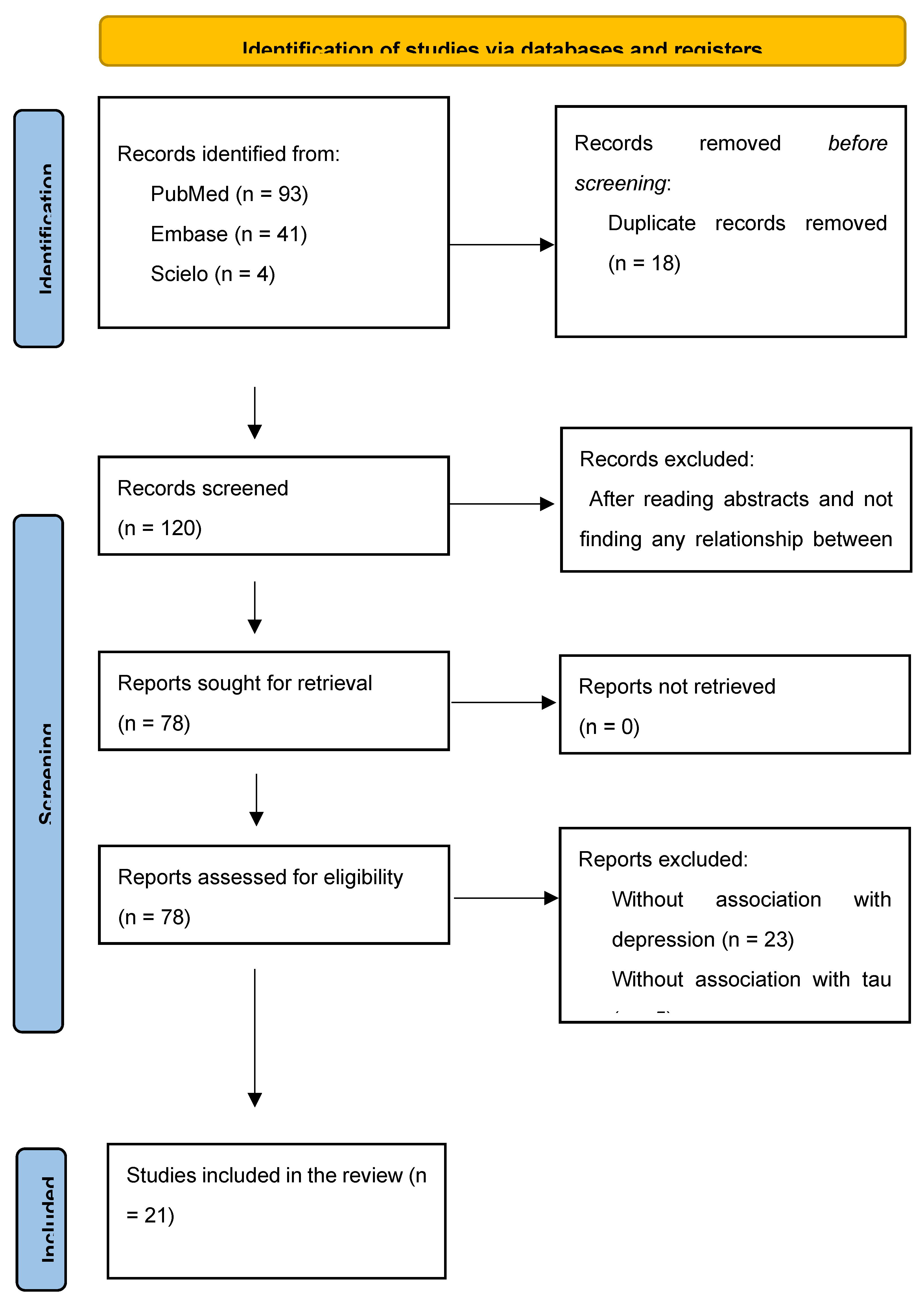

2. Method

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Weingarten, M.D.; Lockwood, A.H.; Hwo, S.-Y.; Kirschner, M.W. A Protein Factor Essential for Microtubule Assembly. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 1975, 72, 1858–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witman, G.B.; Cleveland, D.W.; Weingarten, M.D.; Kirschner, M.W. Tubulin requires tau for growth onto microtubule initiating sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1976, 73, 4070–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghfard, A.; Bozorgi, A.R.; Ahmadi, S.; Shojaei, M. The History of Melancholia Disease. Iran J M Sci 2016, 41, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, G. Synopsis Nosologiæ Methoticæ, 3rd ed.; Edinburg Press: London, UK, 1780; p. 349. [Google Scholar]

- Mayne, R.G. An Expository Lexion of the Terms, Ancient and Modern, in Medical and General Science; Churchill: London, 1860. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler, K.S. The genealogy of major depression: symptoms and signs of melancholia from 1880 to 1900. Mol Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1539–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perris, C. A study of a bipolar (manic-depressive) and unipolar recurrent depressive psychosis. Introduction. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1966, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Lövestam, S.; Murzin, A.; Peak-Chew, S.; Franco, C.; Bogdani, M.; Latimer, C.; Murrell, J.; Cullinane, P.; Jaunmuktane, Z.; et al. Tau filaments with the Alzheimer fold in cases with MAPT mutations V337M and R406W. bioRxiv. PrePrint 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Sun, H.; Cai, Q.; Tai, H.C. The Enigma of Tau Protein Aggregation: Mechanistic Insights and Future Challenges. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goedert, M.; Spillantini, M.G. Ordered Assembly of Tau Protein and Neurodegeneration. In Tau Biology, Takashima, A., Ed. Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1184, pp. 3–21.

- Watanabe, H.; Bagarinao, E.; Yokoi, T.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ishigaki, S.; Mausuda, M.; Katsuno, M.; Soube, G. Tau Accumulation and Network Breakdown in Alzheimer's Disease. In Tau Biology, Takashima, A., Ed. Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1184, pp. 231–240.

- Gratuze, M.; Joly-Amado, A.; Buee, L.; Vieau, D.; Blum, D. Tau, Diabetes and Insulin. In Tau Biology, Takashima, A., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1184, pp. 259–287. [Google Scholar]

- Naumenko, V.S.; Popova, N.K.; Lacivita, E.; Leopoldo, M.; Ponimaskin, E.G. Interplay between Serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 Receptors in Depressive Disorders. CNS Neursci Therap 2014, 20, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Mei, B.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Wei, G.; Kuang, F.; Li, B.; Su, S. Prevalence and risk factors for persistent symptoms after COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2024, 30, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertollo, A.G.; Galvan, A.C.L.; Dallagnol, C.; Cortez, A.D.; Ignácio, Z.M. Early Life Stress and Major Depressive Disorder-An Update on Molecular Mechanisms and Synaptic Impairments. Mol Neurobiol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beurel, E.; Toups, M.; Nemeroff, C.B. The Bidirectional Relationship of Depression and Inflammation: Double Trouble. Neuron 2020, 107, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernad, B.-C.; Tomescu, M.-C.; Anghel, T.; Lungeanu, D.; Enătescu, V.; Bernard, E.S.; Nicoras, V.; Arnautu, D.-A.; Hogea, L. Epigenetic and Coping Mehcanisms of Stress in Affective Disorders: A Scoping Review. Medicina 2024, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCallum, R.T.; Perreault, M.L. Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3: A Focal Point for Advancing Pathogenic Inflammation in Depression. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheynin, J.; Liberzon, I. Circuit dysregulation and circuit-based treatments in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neurosci Lett 2017, 649, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lis, M.; Miłuch, T.; Majdowski, M.; Zawodny, T. A link between ghrelin and major depressive disorder: a mini review. Front Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1367523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Gong, W.G.; Wang, Y.J.; Sun, J.J.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Z.J.; Ren, Q.G. Escitalopram alleviates stress-induced Alzheimer's disease-like tau pathologies and cognitive deficits by reducing hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reactivity and insulin/GSK-3β signal pathway activity. Neurobiol Aging 2018, 67, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panza, F.; Lozupone, M.; Bellomo, A.; Imbimbo, B.P. Do anti-amyloid- β drugs affect neuropsychiatric status in Alzheimer's disease patients? Ageing Research Reviews 2019, 55, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreasen, N.; Minthon, L.; Clarberg, A.; Davidsson, P.; Gottfries, J.; Vanmechelen, E.; Vanderstichele, H.; Winblad, B.; Blennow, K. Sensitivity, specificity, and stability of CSF-tau in AD in a community-based patient sample. Neurology 1999, 53, 1488–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerger, K.; Zinkowski, R.; Teipel, S.; Arai, H.; DeBernardis, J.; Kerkman, D.; McCulloch, C.; Padberg, F.; Faltraco, F.; Goernitz, A.; et al. Differentiation of Geriatric Major Depression From Alzheimer's Disease With CSF Tau Protein Phosphorylated at Threonine 231. Am J Psychiatry 2003, 160, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönknecht, P.; Pantel, J.; Hartmann, T.; Werle, E.; Volkmann, M.; Essig, M.; Amann, M.; Zanabili, N.; Bardenheuer, H.; Hunt, A.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau levels in Alzheimer's disease are elevated when compared with vascular dementia but do not correlate with measures of cerebral atrophy. Psychiatry Research 2003, 120, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasko, I.; Lederer, W.; Oberbauer, H.; Walch, T.; Kemmler, G.; Hinterhuber, H.; Marksteiner, J.; Humpel, C. Measurement of Thirteen Biological Markers in CSF of Patients with Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2006, 21, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönknecht, P.; Pantel, J.; Kaiser, E.; Thomann, P.; Schröder, J. Increased tau protein differentiates mild cognitive impairment from geriatric depression and predicts conversion to dementia. Neuroscience Letters 2007, 416, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, P.; Skoog, I.; Waern, M.; Blennow, K.; Pálsoon, S.; Rosengren, L.; Gustafson, D. The Relationship Between Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers and Depression in Elderely Women. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007, 15, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Kepe, V.; Barrio, J.R.; Siddarth, P.; Manoukian, V.; Elderkin-Thompson, V.; Small, G.W. Protein Binding in Patients With Late-Life Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011, 68, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, T.; Brandão, C.O.; Coutinho, E.S.F.; Engelhardt, E.; Laks, J. Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers in Alzheimer's Disease and Geriatric Depression: Preliminary Finding from Brazil. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics 2012, 18, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomara, N.; Bruno, D.; Sarreal, A.S.; Hernando, R.T.; Nierenberg, J.; Petkova, E.; Sidtis, J.J.; Wisniewski, T.M.; Mehta, P.D.; Pratico, D.; et al. Lower CSF Amyloid Beta Peptides and Higher F2-Isoprostanes in Cognitively Intact Elderly Individuals With Major Depressive Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2012, 169, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diniz, B.S.; Teixeira, A.L.; Machado-Vieira, R.; Talib, L.L.; Radanovic, M.; Gattaz, W.F.; Forlenza, O.V. Reduced Cerebrospinal Fluid Levels of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Is Associated With Cognitive Impairment in Late-Life Major Depression. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 2014, 69, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomara, N.; Bruno, D.; Osorio, R.S.; Reichert, C.; Nierenberg, J.; Sarreal, A.S.; Hernando, R.T.; Marmar, C.R.; Wisniewski, T.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. State-dependent alterations in CSF Abeta42 levels in cognitively intact elderly with late life major depression. Neuroreport 2016, 27, 1068–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, M.M.; Insel, P.S.; Nelson, C.; Touson, D.; Schöll, M.; Mattsson, N.; Sacuiu, S.; Bickford, D.; Weiner, M.W.; Mackin, R.S. Chronic depressive symptomatology and CSF amyloid beta and tau levels in mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017, gps.4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, C.; Pierantozzi, M.; Chiaravalloti, A.; Sancesario, G.M.; Mercuri, N.B.; Franchini, F.; Schillaci, O.; Sancesario, G. When Cognitive Decline and Depression Coexist in the Elderly: CSF Biomarkers Analysis Can Differentiate Alzheimer's Disease from Late-Life Depression. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babulal, G.M.; Roe, C.M.; Stout, S.H.; Rajasekar, G.; Wisch, J.K.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; Morris, J.C.; Ances, B.M. Depression is Associated with Tau and Not Amyloid Poisitron Emission Tomography in Cognitively Normal Adults. J Alzheimer Dis 2020, 74, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.-r.; Yang, L.-y.; Zheng, H.-f.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, B.-b.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.-w.; Shen, D.-y. Plasma levels of Interleukin 18 but not amyloid-B or Tau are elevated in female depressive patients. Comprehensive Psychiatry 2020, 97, 1521159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, J.C.; Stella, F.; Pais, M.V.; Radanovic, M.; Canineu, P.R.; Joaquim, H.P.G.; Talib, L.L.; Forlenza, O.V. Cognitive impairment in remitted late-life depression is not associated with Alzheimer's disease-related CSF biomarkers. Journal of Affective Disorders 2020, 272, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, S.; Takahata, K.; Shimada, H.; Kubota, M.; Kitamura, S.; Kimura, Y.; Tagai, K.; Tarumi, R.; Tabuchi, H.; Meyer, J.H.; et al. Excess tau PET ligand retention in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2020, 26, 5856–5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.; Sieber, F.E.; Blennow, K.; Inouye, S.K.; Kahn, G.; Leoutsakos, J.-M.; Marcantonio, E.R.; Neufeld, K.J.; Rosenberg, P.B.; Wang, N.-Y.; et al. Association of Depression Symptoms With Postoperative Delirium and CSF Biomarkers for Alzheimer's Disease Among Hip Fracture Patients. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry 2021, 29, 1212–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golas, A.C.; Salwierz, P.; Rajji, T.K.; Bowie, C.R.; Butters, M.A.; Fischer, C.E.; Flint, A.J.; Herrmann, N.; Mah, L.; Mulsant, B.H.; et al. Assessing the Role of Past Depression in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment, with and without Biomarkers for Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimer's Disease 2023, 92, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwierz, P.; Thapa, S.; Taghdiri, F.; Vasilevskaya, A.; Anastassiadis, C.; Tang-Wai, D.F.; Golas, A.C.; Tartaglia, M.C. Investigating the association between a history of depression and biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease, cerebrovascular disease, and neurodegeneration in patients with dementia. GeroScience 2024, 46, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurmans, I.K.; Ghanbari, M.; Cecil, C.; Ikram, M.A.; Luik, A.I. Plasma neurofilament light chain in association to late-life depression in the general population. Psychiatry and Clinical Nerurosciences 2024, 78, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL, N.; Levis, B.; Neyer, M.A.; Rice, D.B.; Booij, L.; Benedetti, A.; Thombs, B.D. Sample size and precision of estimates in studies of depression screening tool accuracy: A meta-research review of studies published in 2018-2021. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2022, 31, e1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.E.; Iwata, Y.; Chung, J.K.; Gerretsen, P.; Graff-Guerrero, A. Tau in Late-Life Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2016, 54, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blennow, K.; Wallin, A.; Ågren, H.; Spenger, C.; Siegfried, J.; Vanmechelen, E. tau Protein in Cerebrospinal Fluid: A Biochemical Marker for Axonal Degeneration in Alzheimer Disease? Mol and Chemical Neuropathology 1995, 26, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertze, J.; Minthon, L.; Zetterberg, H.; Vanmechelen, E.; Blennow, K.; Hansson, O. Evaluation of CSF Biomarkers as Predictors of Alzheimer's Disease: A Clinical Follow-Up Study of 4.7 Years. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2010, 21, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeira, C.; Lourenço, M.V.; Vargas-Lopes, C.; Suemoto, C.K.; Brandão, C.O.; Reis, T.; Leite, R.E.P.; Laks, J.; Jacob-Filho, W.; Pasqualucci, C.A.; et al. d-serine levels in Alzheimer's disease: implications for novel biomarker development. Transl Psychiatry 2015, 5, e561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisch, R.; Russo, S.J.; Müller, M.B. Neurobiology and Systems Biology of Stress Resilience. Physiol Rev 2024, 104, 1205–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Citation | Depression | Controls | |

| Andreasen et al [24] | n = 28 - CSF T-tau, pg/mL = 231 ± 110 |

n = 65 - CSF T-tau, pg/mL = 227 ± 101 |

r = .96 p < .00001* |

| Buerger et al [25] | n = 34 - CSF P-tau231 not informed* |

n = 21 - CSF P-tau231 not informed |

U=226 p < .050 |

| Schönknecht et al [26] | n = 25 T-tau, pg/mL = 202.6 ± 96.2 |

n = 17 T-tau, pg/mL = 246.6 ± 111.4 |

p > .050 |

| Blasko et al [27] | n = 11 - CSF P-tau181 = 28.6 ± 5 |

n = 25 - CSF P-tau181 = 22.8 ± 2 |

p > .050 |

| Schönknecht et al [28] | n = 54 - CSF P-tau181 = 40.6 ± 14.8 |

n = 24 - CSF P-tau181 = 49.7 ± 9.4 |

p > .050 |

| Gudmunsdsson et al [29] | n = 11 - CSF T-tau, pg/mL = 287.5 ± 114.9 |

n = 70 - CSF tau, pg/mL = 331.7 ± 189.8 |

t = .445 p = .657 |

| Kumar et al [30] | n = 20 - PET FDDNP global = 1.10 ± 0.04 |

n = 19 - PET FDDNP global = 1.07 ± 0.03 |

t = 2.55 p < .010 |

| Reis et al [31] | n = 20 - CSF P-tau = 40.5 (15.5-60.4) T-tau = 169 (141-276) |

n = 8 P-tau = 40.3 (18.4-51.3) T-tau = 156 (108-219) |

p = .700 p = .200 |

| Pomara et al [32] | n = 28 - CSF P-tau = 48.9 ± 25.9 T-tau = 273.0 ± 114.3 |

n = 19 - CSF P-tau = 51.6 ± 20.9 T-tau = 328.7 ± 151.7 |

p = .710 p = .160 |

| Diniz et al [33] | n = 25 - CSF P-tau181 = 73.6 ± 49.2 |

n = 25 - CSF P-tau181 = 68.4 ± 54.1 |

p = .700 |

| Pomara et al [34] | n = 28 - CSF Baseline: P-tau = 48.68 ± 30.76 T-tau = 254.33 ± 122.39 Follow-up: P-tau = 49.63 ± 34.86 T-tau = 277.33 ± 111.98 |

n = 19 - CSF Baseline: P-tau = 48.93 ± 25.87 T-tau = 343.59 ± 152.59 Follow-up: P-tau = 51.12 ± 18.12 T-tau = 365.71 ± 136.17 |

P-tau x Aβ: p = .700 T-tau x Aβ40: p = .011 T-tau x Aβ42: p = .016 |

| Gonzales et al [35] | n = 80 - CSF P-tau = 47.34 ± 22.94 T-tau = 101.51 ± 58.44 |

n = 158 - CSF P-tau = 39.09 ± 22.44 T-tau = 83.92 ± 51.77 |

p = .004 p = .031 |

| Liguori et al [36] | n = 48 - CSF P-tau = 33.46 ± 8.56 T-tau = 205.42 ± 83.21 |

n = 58 - CSF P-tau = 32.75 ± 5.21 T-tau = 252.89 ± 43.26 |

p > .050 p > .050 |

| Bubalat et al [37] | n = 38 - PET tau- amyloid- = 15 (39.5%) tau- amyloid+ = 0 (0%) tau+ amyloid- = 16 (42.1%) tau+ amyloid+ = 7 (18.4%) |

n = 263 - PET tau- amyloid- = 142 (54%) tau- amyloid+ = 23 (8,7%) tau+ amyloid- = 57 (21.6%) tau+ amyloid+ = 41 (15.6%) |

OR = 2.42 (1.14-5.14) (p = .021) p = .301 p = .998 p = .060 p = .284 |

| Liu et al [38] | n = 64 - plasma tau = 4.322 ± 2.116 |

n = 75 - plasma tau = 4.488 ± 1.541 |

p = .247 |

| Loureiro et al [39] | LOD + cognitive impairment: n = 22 – CSF P-tau = 41.9 ± 5.2 T-tau = 93.8 ± 14.4 EOD + cognitive impairment: n = 31 – CSF P-tau = 38.4 ± 4.4 T-tau = 98.9 ± 11.8 |

n = 22 - CSF P-tau = 39.8 ± 5.4 T-tau = 83.7 ± 14.5 |

p > .050 p > .050 |

| Moriguchi et al [40] | n = 20 - PET [11C]PBB3 SUVRs = 0.96 ± 0.07 [11C]PiB SUVRs = 1.20 ± 0.20 |

n = 20 - PET [11C]PBB3 SUVRs=0.89 ± 0.08 [11C]PiB SUVRs = 1.24 ± 0.21 |

p = .020 p = .390 |

| Chan et al [41] | n = 30 - CSF P-tau = 63.11 ± 22.33 T-tau = 510.60 ± 215.17 |

n = 169 - CSF P-tau = 55.74 ± 25.80 T-tau = 492.41 ± 292.70 |

p = .170 p = .760 |

| Golas et al [42] | Depression only n = 7 - CSF P-tau = 40.6 ± 10.2 T-tau = 173.8 ± 80.7 Depression + MCI n = 12 - CSF P-tau = 53.3 ± 21.8 T-tau = 315.9 ± 282.8 |

MCI only n = 12 - CSF P-tau = 71.1 ± 28.3 T-tau = 473.0 ± 302.1 |

p = .066 p = .028*** |

| Salwierz et al [43] | Past depression+ n = 20 - CSF P-tau = 93.3 ± 48.0 T-tau = 699.1 ± 500.3 |

Past depression- n = 65 - CSF P-tau = 86.9 ± 40.1 T-tau = 656.0 ± 405.7 |

p = .554 p = .695 |

| Schuurmans et al [44] | MDD n = 51 T-tau (hr) = .92 (.75-1.12) |

Any depression symptoms n = 439 T-tau (hr) = .68 (.37-1.25) |

p > .050 |

| Citation | Design | Study aim | Relevance to tau and depression | Relevant Result |

| Andreasen et al [24] | Follow-up | To evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of CSF-tau in clinical practice as a diagnostic marker for AD compared with normal aging and depression, to study the stability of CSF-tau in longitudinal samples, and to determine whether CSF-tau levels are influenced by different covariates such as gender, age, duration or severity of disease, or possession of the APOE-ε4 allele. | To study factors that potentially may influence the variability (and thus the sensitivity and specificity) of CSF-tau. |

There were no significant correlations between age and CSF-tau either in the probable AD (r = -0.04), possible AD (r = 0.02), or control (r = 0.24) groups, whereas a significant correlation was found in the depression group (r = 0.74; p < 0.0001). |

| Buerger et al [25] | Case-control | Whether p-tau231 levels improve the differential diagnosis between geriatric major depression and Alzheimer’s disease. | P-tau231 levels could accurately discriminate between major depression and Alzheimer’s disease because they detect an early and specific feature of the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease. | Significant difference in p-tau231 levels (χ2= 78, df=3, p<0.001) among all groups. P-tau231 levels were higher in major depression patients than in healthy comparison subjects (Mann-Whitney U=226, df=1, p<0.05). |

| Schönknecht et al [26] | Case-control | The potential value of tau levels in the differential diagnosis of AD, VD, and MDD. | The potential effects of psychotropic medication, such as antidepressants, on tau concentration. |

Tau protein concentrations in patients with AD were significantly (P-0.05) elevated compared with those in VD patients, depressed patients, and controls, but did not significantly differ between controls and patients with depression. |

| Blasko et al [27] | Case-control | To evaluate CSF levels of 13 potential biomarkers in patients with AD, frontotemporal lobe dementia, alcohol dementia, major depression, and control patients without any neuropsychiatric disease. | A variety of other possible markers have been examined in the CSF of AD patients to obtain an insight into the pathophysiology of AD and to establish them as disease markers and differentiate from other illnesses such as depression. |

By using the ratio P-tau181/Aβ42, AD patients were separated from healthy control subjects (area under the ROC curve, 0.901; p < 0.001), from subjects with FTLD (area under the ROC curve, 0.900; p = 0.006) and from subjects with alcohol dementia and major depression (area under the ROC curve, 0.909; p < 0.001 and 0.913; p < 0.001, respectively). |

| Schönknecht et al [28] | Case-control | Cross-sectionally, MCI patients would show higher t-tau and p-tau levels com- pared to patients with geriatric major depressive disorder and controls. | Though MCI often overlaps with depressive symptoms making early diagnosis difficult, to date no CSF marker has been probed to support the differential diagnosis of geriatric major depressive disorder and MCI eventually converting to AD. | CSF t-tau and p-tau levels were significantly increased in patients with mild cognitive impairment when contrasted to patients with geriatric major depressive disorder and control. |

| Gudmunsdsson et al [29] | Case-control | To better understand the biological basis and potential biomarkers for geriatric depression. |

Aβ42 and T-tau are sometimes used to discriminate geriatric depression from mild forms of AD in clinical studies. However, studies focusing on the relationship between these CSF biomarkers and geriatric depression are lacking. | T-tau levels increased with increasing age (linear- by-linear association, χ2 = 5.774, df=1, Monte Carlo p=0.015). No differences in T-tau were observed compare depression and controls. |

| Kumar et al [30] | Case-control | To examine and compare protein (amyloid and tau) binding in critical brain regions in patients diagnosed as having late-life MDD and healthy control. | Smaller brain volumes, identified using volumetric MRI estimates, are presumed to reflect neurodegeneration, although neuropathologic findings indicate only circumscribed neuronal loss in MDD. | The global [18F]FDDNP binding value was significantly higher in MDD group when compared with that of controls. Post hoc t tests demonstrated that the depressed group had significantly higher binding in the lateral temporal and PC regions when compared with controls (Cohen d effect sizes of 0.92 and 0.67, respectively). |

| Reis et al [31] | Case-control | Depression is a highly prevalent disorder in the elderly and one of the risk factors for developing dementia. The present study involves patients with AD, geriatric MDD and cognitively healthy controls aiming to compare baseline CSF biomarkers. | The assessment of changes in the concentrations of CSF Aβ42, T-tau, and P-tau in nondemented patients with depression with and without cognitive manifestations can provide important in- formation on the clinical course and outcome of these syndromes. | There was not any significant difference in measures of P-tau among the groups. Higher levels of P-tau were observed in four MDD patients compared with controls based on the previously established cut-off value of 61 pg/mL. |

| Pomara et al [32] | Case-control | Whether major depression was associated with CSF levels of amyloid beta, tau protein, and F2-isoprostanes in elderly individuals with major depressive disorder and age-matched nondepressed comparison subjects. | Increased brain amyloid beta and tau protein binding were observed in currently depressed individuals with MDD and no MCI. | No differences were observed in total and phosphorylated tau proteins. |

| Diniz et al [33] | Case-control | To determine the concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), amyloid-β42, total Tau, and phosphorylated Tau in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with LLD and cognitive impairment compared to healthy older adults. | None of the previous studies specifically addressed whether cognitive impairment in older adults with LLD related to abnormalities in CSF biomarkers related to AD (i.e., Aβ42, total Tau, and phosphorylated Tau181) or other biomarkers. | No significant differences in T-Tau: LLD, 55.5 ± 36.6 pg/ml vs. controls, 49.0±33.9 pg/ml, t(48) = 0.64, p = .5; P-Tau181: LLD, 73.6±49.2 pg/ml vs. control, 68.4±54.1 pg/ml, t(48) = 0.35, p = .7). |

| Pomara et al [34] | Follow-up | To determine first whether late-life major depression (LLMD) and time (baseline to follow-up) influenced the Aβ levels; and second to determine whether any time-related change in Aβ was associated with changes in the severity of depressive symptoms | Several lines of evidence from epidemiological, case-control and longitudinal studies provide support for an association between depression (or depressive symptoms) and an increased risk for dementia and AD, or for depression as a prodromal state of AD. | Comparisons of the baseline to follow-up levels showed significant correlation between CSF Aβ42 levels and t-tau (r=0.557, P=0.016). A significant correlation was found between CSF Aβ40 and t-tau levels as well (r=0.586, P=0.011). Thus, increases in t-tau in the LLMD group, over time, were associated with increases in both CSF Aβ42 and CSF Aβ40. The same significant correlations were not found between p-tau and CSF Aβ42 or CSF Aβ40 (P’s >0.700). |

| Gonzales et al [35] | Case-control | To evaluate the association between SSD and CSF biomarkers in a subset of individuals with MCI and stable subsyndromal depressive symptomatology. | Emerging literature indicates that even subsyndromal symptoms of depression (SSD), depressive symptomology below the frequency and severity for clinical diagnosis, accelerates cognitive decline in MCI, and hastens the conversion to dementia. | No group differences were observed for CSF T-tau (p = .497) or P-tau (p = .392). Using Mann-Whitney U test was found a significative difference in CSF P-tau (p = 0.004). |

| Liguori et al [36] | Follow-up | To investigate the cross-sectional association between depressive symptoms and cerebral tau [18F T807 (also known as 18F-AV-1451) tau positron emission tomography (PET) imaging] in cognitively normal (CN) older adults. | Depressive symptoms, both major depression and subclinical depressive symptoms, are common in older adults, in whom they are disabling and can be associated with functional impairment, decreased quality of life, and cognitive impairment. | Higher GDS was significantly associated with greater IT tau (partial r = 0.188, p = 0.050) and marginally associated with greater EC tau (partial r = 0.183, p = 0.055). |

| Bubalat et al [37] | Cohort | To examined if tau and amyloid imaging were associated with a depression diagnosis among cognitively normal adults. | Higher PET amyloid levels and higher CSF ratio tau/Aβ42 at baseline developed more depressive symptoms as measured by a change score in the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) over one year, compared with participants with lower biomarker levels. | Participants with elevated tau were 1.42 times more chance to be depressed. Antidepressant use modified this relationship where participants with elevated tau who were taking antidepressants had greater odds of being depressed. |

| Liu et al [38] | Case-control | To determine whether plasma IL18, Aβ40, Aβ42, and the AD-associated tangle component Tau, as well as IL18 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) may be biomarkers for depression. | Peripheral Tau levels are altered in depressive patients and whether IL18, Aβ and Tau are as- sociated with each other in depression remain unclear. | None of the plasma levels of IL18, Aβ40, Aβ42, and Tau, the ratio of Aβ42/Aβ40, and the genotypes of IL18 SNPs were significantly different between combined depressive patients and combined healthy controls, or between male depressive patients and male controls. |

| Loureiro et al [39] | Case-control | To determine a panel of AD-related CSF biomarkers in a cross-section of elders with MCI with and without LLD. | Depression may alternatively be an incipient feature of a subjacent neurodegenerative disorder – e.g., AD at pre-dementia stages – in which case depressive symptoms could be, along with MCI. | Mean Aβ1-42/P-tau ratio: aMCI, 7.9 (p < 0.001); LOD 14.2 (p < 0.001); EOD, 15.3 (p < 0.001); controls, 17.1 (p < 0.001); p < 0.05. No differences were observed in total and phosphorylated tau proteins. |

| Moriguchi et al [40] | Case-control | To investigate tau and Aβ accumulations both simultaneously and separately in the same subjects with elderly MDD. | There is ample evidence that depression is a risk factor for AD. | Regional [11C]PBB3 SUVRs in MDD patients had a higher trend than those of healthy controls in the anterior cingulate cortex (t(38) = 2.13, p = 0.04). |

| Chan et al [41] | Cohort | To explore the association between depression and postoperative delirium in hip fracture patients, and to examine Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology as a potential underlying mechanism linking depressive symptoms and delirium. | In AD, a risk factor for postoperative delirium, depression and other neuropsychiatric symptoms have been the focus of growing interest as early manifestations or prodromal symptoms of an underlying neurodegenerative disease process. | Both CSF A 42/t-tau (β = −1.52, 95%CI = −2.1 to −0.05) and A 42/p-tau181 (β = −0.29, 95%CI = −0.48 to −0.09) were inversely associated with higher GDS-15 scores, where lower ratios indicate greater AD pathology. |

| Golas et al [42] | Cohort | To investigate the relationship between past depression and WMH burden in those with positive (AD+) and negative (AD-) CSF biomarker profiles for AD. | There is conflicting evidence to support a direct link between Aβ and tau, two of the pathological hallmarks of AD and LLD. | Participants with MCI exhibited greater levels of phosphorylated tau (P tau) than participants with MDD (p = 0.03). |

| Salwierz et al [43] | Cohort | To investigate the relationship between a history of depression and bio- markers of AD and CVD in patients with dementia in a clinical setting. | A growing body of research has explored the association between depression and dementia where individuals with a history of depression are not only at an increased risk of developing dementia. | Trends towards higher Fazekas scores in Past Depression− patients and a higher proportion of females with depression in Past Depression+ patients. No differences in T-tau were observed compare depression and controls. |

| Schuurmans et al [44] | Follow-up | Whether plasma biomarkers for neuropathology associate with late-life depression in middle-aged and elderly individuals. | Evidence shows that those who suffer from neurodegenerative disease are more likely to experience late-life depression. | With each log2 pg./mL increase in amyloid-β 40, participants had a 0.70 (95% CI [0.15, 1.25]) points higher depressive symptoms score at baseline. No other statistically significant cross-sectional or longitudinal associations were found. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).