1. Introduction

Electronics have become an integral part of everyday life, from wearable devices to smart homes fitted with sensors and remote controls to optimize consumption and facilitate daily household tasks. The advancement in electronics, especially computers, has also allowed simplifying many complex multi-factor tasks. However, electronics have become a double-edged weapon, with the constant advancement of technology and electronics and their involvement in most daily tasks leading to the continuous upgrading of electronic devices and equipment while discarding used ones and consequently bringing about the problem of electronic waste, or e-waste for short.

In 2019, the amount of e-waste generated reached 53 Mt with that number projected to become 75 Mt in the next decade [

1]; its generation is estimated to continue increasing at a rate of 3-5% per year [

2]. The problem of e-waste lies in the lack of proper handling and recycling schemes which leaves the sector heavily controlled by informal collectors and handlers. The percentage of officially handled and reported e-waste generated globally in 2019 was only 17.4% with the remainder being illegally and unsafely handled [

3]. Much of the unhandled waste which is not reported by official bodies can end up in the municipal waste streams (0.6 Mt), local dumps, recycled under unfavourable conditions (1.12 Mt), handled as mixed metal scrap (1.1 Mt) or even exported legally (0.29 Mt) and illegally to developing countries (almost 2.09 Mt) [

4].

E-waste contains a mix of materials, over one thousand different materials [

1], with varying properties, some of which are non-degradable, hazardous, ferrous and non-ferrous or ozone-depleting chemicals. Among the materials included are heavy metals, precious and rare earth metals as well as plastics, glass and persistent organic pollutants (POPs) [

4,

5,

6].

Attempts to take advantage of the advancement in computational power and to simplify the complexity of the intertwined conditions of sustainability gave rise to the branch of computational sustainability, a field that uses the recent advancements in computation and modelling in order to help solve the complex problem of sustainability with its numerous variables, primarily the aspects of the environment, social and legal boundaries as well as the economy and financial viability.

A branch of computational sustainability is the development of Decision Support Systems (DSSs) which consider the various constraints and the relations between the various factors to recommend scenario-based solutions. DSSs can help support policy and decision-makers in making a more profound decision based on the suppositions of the multifactor model. Since the use of DSSs in tackling waste problems, especially the collection phase [

7], has been demonstrated to be effective, thus they can be used to confront the complexity of electronic waste and offset its impacts. One way of developing DSSs is using ontologies to build the framework.

An ontology is a way of describing a domain of knowledge semantically. The way an ontology is developed makes it uniform and reusable across different domains and among industries within the same domain. Simply put, an ontology can be described as a single universal language that is agreed upon and understood by the different domains which allows the easy integration of knowledge bases.

Typically, an Ontology is made up of classes, relations and instances of the classes. A class is typically describing a concept within the domain, and an instance of the class is an object belonging to that specific class. Different classes and instances can be connected or disjoined using the relations defined [

8,

9]. To develop an Ontology, OWL language is among the most popular.

Ontologies were recently developed and incorporated into solutions to tackle various problems in the sustainability field. For instance, in the construction field an ontology was developed based on Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) to evaluate the cement-steel-slag stabilized soft soils [

10], and another was developed to evaluate the energy and carbon impacts of concrete structures [

11]. In the field of product life cycle, an ontology was created to represent semantically the product life cycle and facilitate the carrying out of LCA [

12]. In process optimization, a cross-domain solution was developed which takes into consideration the various domains of weather, buildings, and process engineering to tackle industrial air pollution [

9], while another framework was developed for eco-industrial parks to help share resources and decrease waste and pollution [

13]. In the nexus between Water, Energy and Food, an ontology was used to project a system’s sustainability and to aid decision-makers in optimizing the system inputs to minimize the trade-offs and guarantee sustainable growth [

14]. In the field of urban sustainability, USDA ontology was developed to join domain-specific ontologies and permit their integrated usage in a single high-level ontology [

15].

In the field of waste management, ontologies have been used as a base for DSSs for municipal solid waste [

16,

17], for the selective sorting of waste and their subsequent recycling [

18], for waste treatment plant optimization [

19] and even in specific cases of e-waste handling such as disassembly of LCD monitors [

20].

For the development of ontologies, protégé is widely used [

9,

13,

16,

18,

19]. It is an open-source software that uses the OWL language to develop the ontology [

21,

22]. The software allows the use of reasoners that deduce the inferences and new relations among the different classes and instances based on their descriptions and properties added. The software also permits exporting the ontological model to be further incorporated into Decision Support Systems or integrated with other models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Decision Support System Structure and Development

Since DSSs are used to simplify and aid in making informed decisions, being user-friendly is fundamental. Therefore, it is important to define the objectives based on the problem tackled, the nature of users, and the potential uses of the DSS before starting with the development process in order to ensure that the developed solution is tailor-made and meets its objectives. For this purpose, the methodology mentioned in [

8] and followed by [

11] during the development of the OntoSCS are taken as a guide in order to obtain a well-structured design and help define clearly the key aspects of the developed ontology.

A DSS is typically a multilayered system. The current DSS in question consists of 3 layers. A base layer that is made up of the ontology, and will serve as a core to the DSS where all data is saved. The domains covered by the ontology should overlap with the objectives of the DSS and the usage intended. The broader the ontology is, the larger the scope the DSS covers. The top layer of the DSS is a Graphical User Interface (GUI), which would allow users to interact with the ontology as a base layer, submit inputs to the system and retrieve relevant data in a simplified manner. The base layer and the top layer are connected together through a querying and computational program that processes the inputted data, draws relations among the various domains and categories in the ontology based on the inputs from the user and the relations defined in the ontology between the various components as well as feeds the results to the GUI to be represented to the user. In this paper, only the building of the base layer ontology will be studied in depth while the intermediate computational layer and the GUI will be covered in further publications.

2.1.1. Objectives and Scope of Usage of the DSS

Under the scope of e-waste are six various categories of electronic or electrical equipment at their end of life or when they are discarded by the consumer [

6,

23]. Given the fact that e-waste contains a myriad of materials, and since the quantity and type of materials contained within each device varies by model and category, it is important to narrow down the scope of the DSS to a certain category and type of e-waste in order to focus on the modelling of the various processes followed in handling this type of e-waste and their respective impacts. It is important to mention at this point that the DSS aims to cover all e-waste types, yet this would be done in phases as it is impractical to model all types at once.

Thus, the scope of the ontology in this paper is focused on the handling of solar PVs. However, it is worth noting that the modular structure with which the ontology is developed leaves the ontology generic at the top layers and gets more specific as we go down the hierarchy. This allows the subsequent integration of other ontologies as well as the further expansion of this ontology to include other e-waste items and their treatment methods in addition to enabling the seamless updating of current methodologies for solar PV treatment as they evolve.

For the ontology to be holistic, the domains covered by the ontology are the treatment processes, hazards including both environmental as well as human health, and materials with all their classifications.

With these domains in mind, other already developed ontologies were assessed in order to be adapted and further developed. Ontologies specifically made for e-waste could not be found. Alternatively, for waste management OntoWM [

24], and SWM-PnR [

25] were found, yet they focus on collection and monitoring. OntoWEDSS [

26] deals with wastewater treatment plants and, hence has little overlap with the domain of e-waste treatment. On the other hand, OntoCAPE [

27] is focused on mainly chemical and process engineering. Hence the building of a new ontology for e-waste from scratch would be favorable.

2.1.2. Potential Users and Use Cases

The domains previously mentioned to be covered by the ontology scope serve to give an overall idea about a specific e-waste item, a treatment method or a target material. This includes the technical handling specifics in addition to the potential environmental and human hazards associated with these techniques and the materials involved.

Ideally, when the DSS is fully developed, it is envisioned to be a simple software tool with a user-friendly GUI. The usage of the DSS should not require any help from language engineers or subject knowledge of ontologies. Thus, the GUI should be straightforward. Inputs to the software can be made in one of three different forms. First, by entering the type of e-waste item the user is interested to learn about its contents and possible treatment methods as well as the respective impacts of each treatment method. Alternatively, the user can choose a specific component of the e-waste item, such as choosing the housing of solar PVs with the expected outcome being the materials included and the retrieval methods along with their impacts. Finally, if the user is interested in a specific material, choosing that material would show them the e-waste items with the highest content of this material. This is specifically useful in the case of urban mining. A prototype of the GUI is shown in

Figure 1.

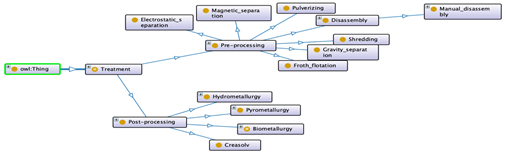

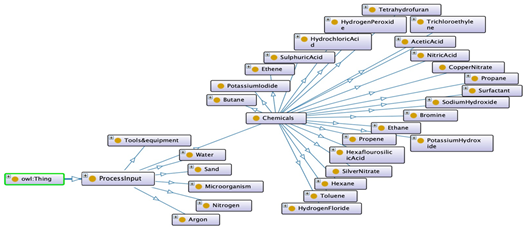

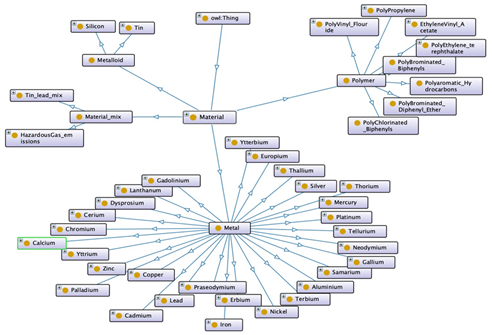

2.2. Structure of the Ontology

Protégé (V5.5) is used in developing the ontology [

21,

22]. The top layer of the ontology is defined by 7 categories: Component, E-waste item, Hazard, Material, Process flow, Process input, and Treatment. These layers are generic to allow modularity and possible integrations with other ontologies that are specifically focused on one of these domains. Each of these categories is then populated in an expanding manner from the top down to maintain the ontology modularity at each sublayer. It is important to say that, although certain categories are certainly necessary, the definition of the categories is flexible and will depend on the objective of the ontology, but also on how this is constructed by the operator.

2.2.1. Defining the Classes

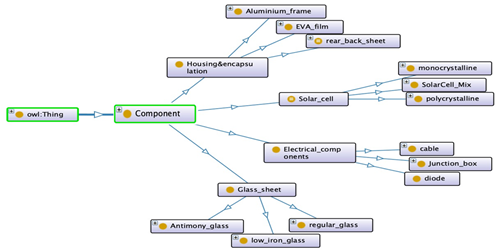

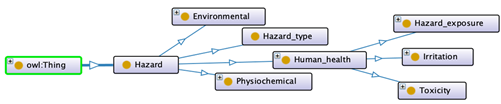

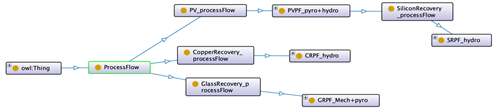

In an ontology, a class is a category and under each class, there can be subclasses that divide the parent class into further subcategories. This process of classes and subclasses is what allows the ontology to be modular since the classes become more specific and focused as they are further down the hierarchy. Based on the previously defined structure of the ontology the parent classes are created. The classes are created to model solar PV of different types; however, some general data was added as well, especially under the materials and treatment classes. The description and hierarchy of each class category are shown in

Table 1. The blue arrow line used to connect the different classes in the various categories represents the relationship of

subclass, for example in the Component category

Aluminium_frame is a subclass of

Housing&encapsulation which is a subclass of

Component.

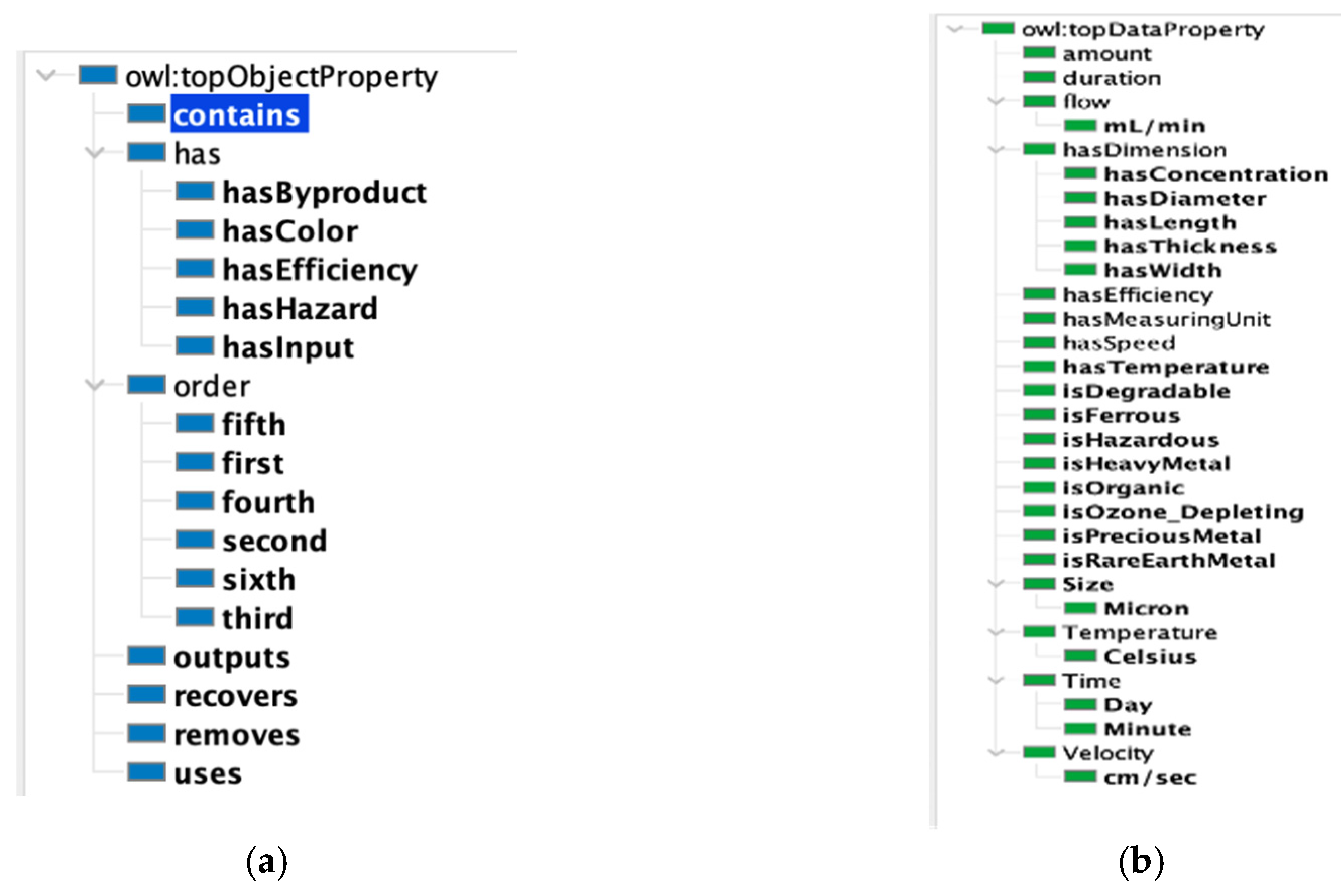

2.2.2. Object Properties and Data Properties

Each class category can contain a group of instances that belong to this class. Instances in ontologies are called individuals. When individuals are created (as further explained in section 2.2.3), their relations with other individuals across the ontology are established using object properties. Otherwise, individuals can be described using data properties which typically have values. The lists of object properties and data properties defined for the e-waste ontology are shown in

Figure 2 (a) and (b) respectively.

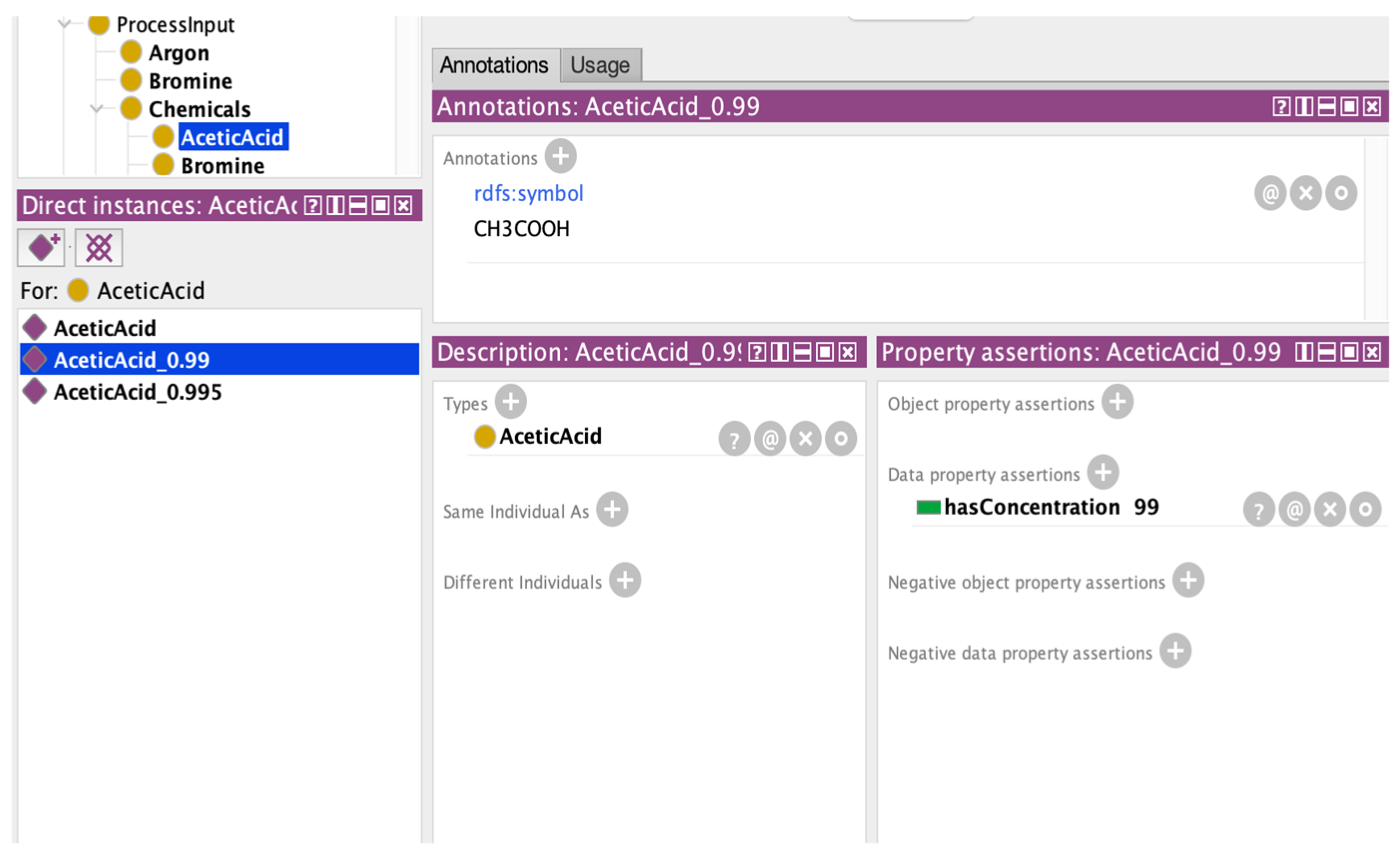

2.2.3. Creating the Individual Instances

Individuals are at the endpoints of an ontology. They come to define a specific case of a class. For instance, under the class of “Process Input” there is a subclass for “Acetic Acid” under which several instances are created for various concentrations of acetic acid, illustrated in

Figure 3. Hence, a precise description of each individual is crucial in order to ensure clarity and avoid confusion in addition to securing clear-cut modelling of the instances in the ontology and how they relate to and interact with each other. For this purpose, annotations are used to provide the extra description needed for both classes and individuals. The annotations used in the e-waste ontology are:

Reference, which documents the sources in the literature from which information was obtained.

Symbol, which is added to individuals of materials or chemicals to report their chemical formula.

Comment, to report any extra information.

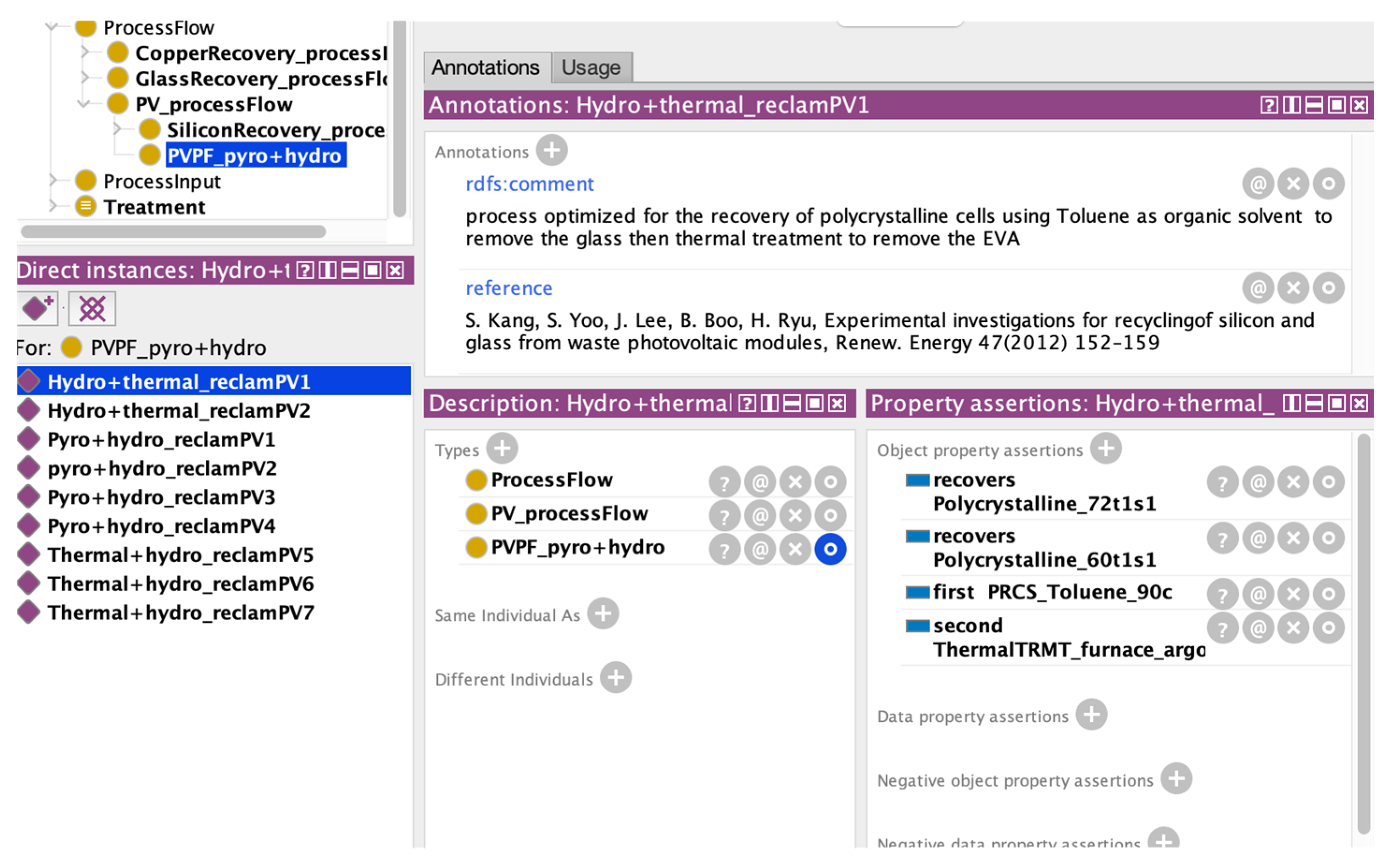

An example of using annotations to better describe the individual “Hydro+thermal_reclamPV1” is shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

Diving deeper into the individuals created in this ontology. Firstly, the e-waste items and their constituent components are created in order to model the solar PVs. The individual “SolarPV_c-Si_Mix_T1” (in the centre of

Figure 5), which belongs to the “e-waste item” category, models a mixture of solar PV of different types, hence the individual “SolarCell_mix” which contains other individuals that represent the different solar PV types such as monocrystalline, polycrystalline and cast monocrystalline cells, each with various versions that differ in size and/or number of cells found per panel. Tracing the “SolarCell_Mix” individual it belongs to the subclass “SolarCell_Mix” which is a child of the “Component” category. Under the same category, there is “Glass_sheet” which has the individual “antimony_glass_0.01-1” that is also used to model the original mixture of solar PV “SolarPV_c-Si_Mix_T1”. Another constituent of the mixture is the “TinLead_mix1” (top centre of

Figure 5) which represents a mixture of tin and lead that was reported in the literature [

28] but not specified under which component these materials were found. The individual “lead” has 3 individuals connected to it using the relation “hasHazard” to model the impacts of this material, in this case, acute toxicity, ingestion, and inhalation.

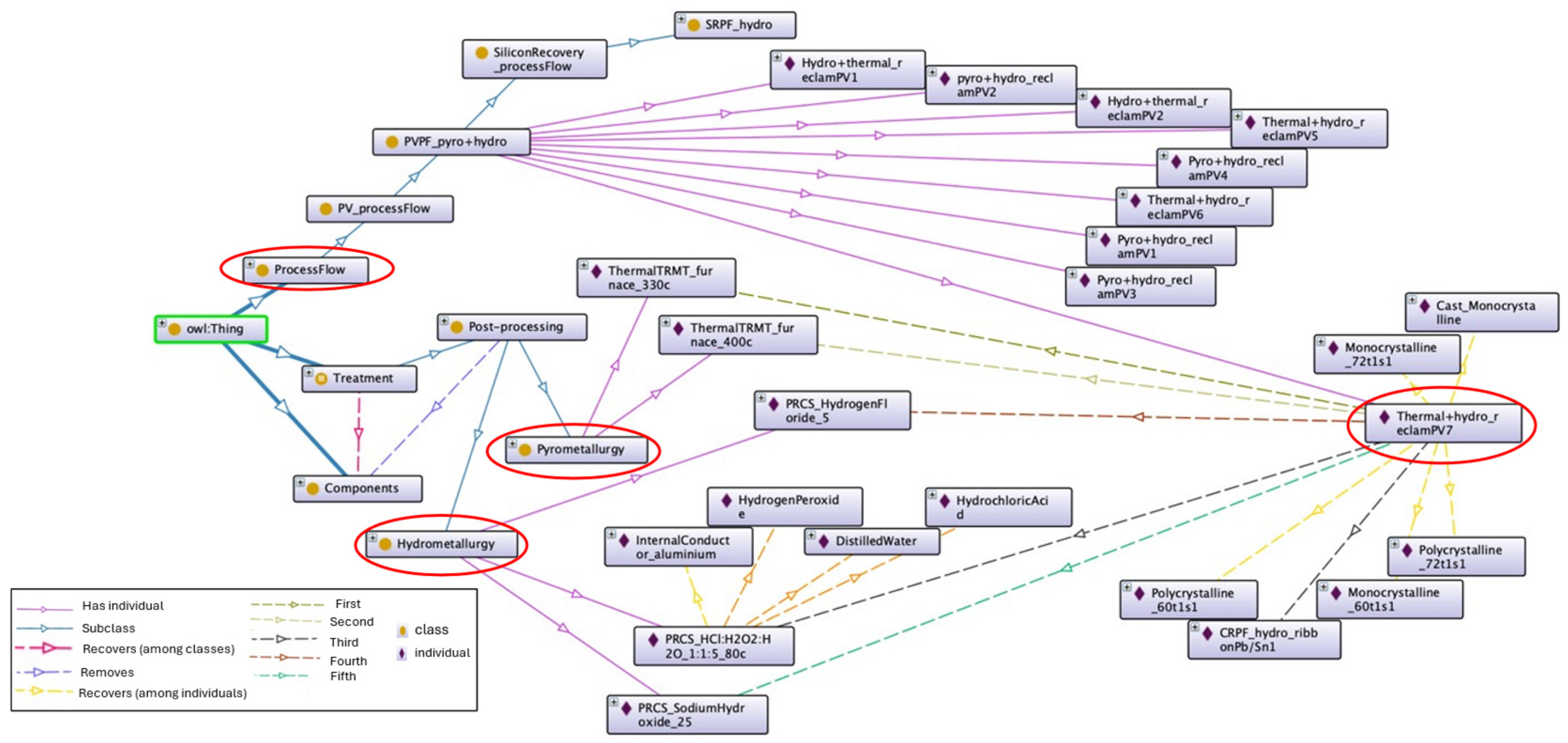

Consequently, in order to model the handling and treatment methods, individuals were created for each step of a treatment method and process specifics were detailed using annotations, object properties, and data properties. For example, to model a treatment method for solar PV which includes a multistage thermal treatment to remove the Ethyl vinyl acetate (EVA) encapsulation and Tedlar followed by multistage hydrometallurgical treatment using a mix of acids to recover the silicon and copper [

29], the individual “Thermal+hydro_reclamPV7” is created (in the rightmost part of

Figure 6). The individual belongs to the Process Flow class category, but it also connects to the components category through the relation “recovers” which ties it to the different instances of solar PV cells; namely: polycrystalline, monocrystalline, and cast monocrystalline with their various dimensions, belonging to the components category and are recovered by this method. In addition, the individual connects to the subclasses of “Hydrometallurgy” and “Pyrometallurgy”, which both descend from the main category “Treatment”, through the various individuals which each represent a step in the treatment process with its respective sequence which is represented in the mapping of the process through the various arrowed lines First through Fifth in

Figure 6 (namely the “ThermalTRMT_furnace_330c” is the first stage of the process and the “PRCS_SodiumHydroxide_25” is the fifth stage; moreover, the construct of the individual is shown in

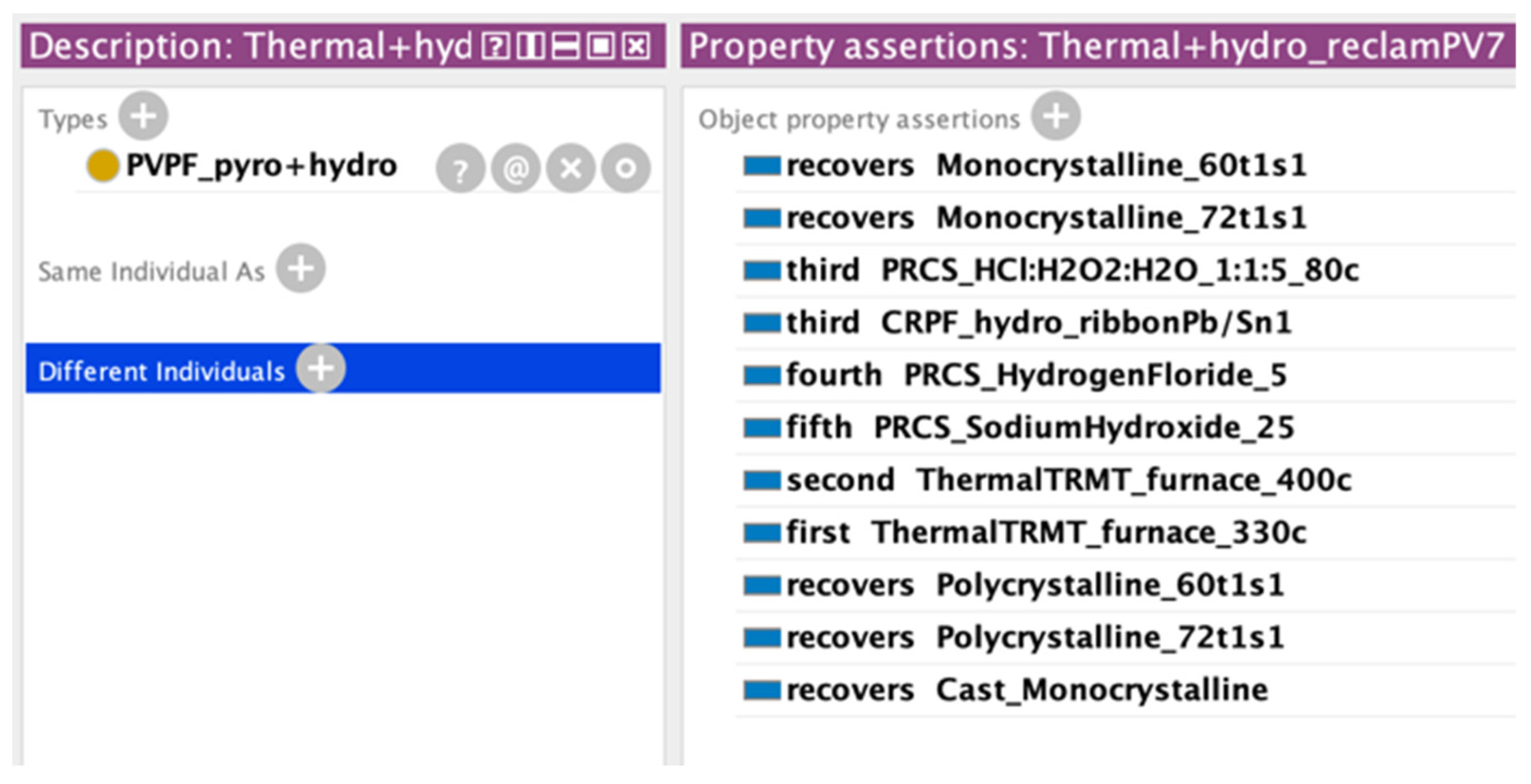

Figure 7 showing the same sequence of the execution of the processes.

2.2.4. Defining the Rules Using Semantic Web Rule Language (SWRL)

The power of using ontologies lies in the ability to automatically derive relations, both direct and indirect, among individuals and classes. This can be realized using rules which guide the reasoner to deduce such relations. The reasoner used for this purpose is HermiT (V1.4.3.456) and the rules are scripted using SWRL [

30].

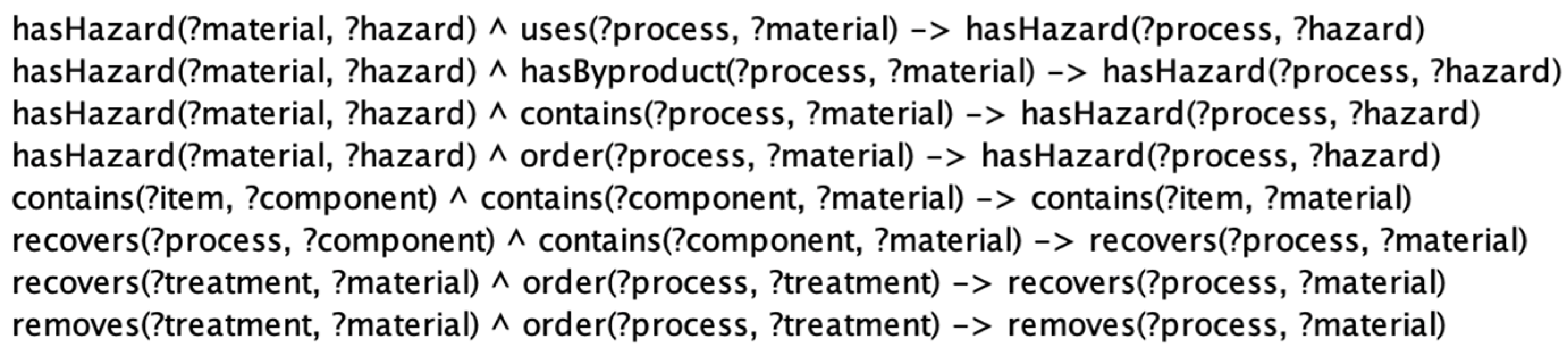

For the e-waste ontology, the rules defined focus on the associated hazards and impacts of the various components, processes, and materials. They also aim to more keenly describe the outputs of processes. For instance, the first rule shown in

Figure 8 states that if a material has a hazard and a process uses that material, this makes the process have the same hazard. Consequently, the second rule in the list associates a hazard to a process in case a material produced as a byproduct from this process has that hazard. The third rule derives a similar relationship related to the hazard associated with materials contained in a process. Regarding the fourth rule, it associates a hazard with a step of the treatment process in case that step contains a material with a hazard. Moreover, the fifth rule associates a material content to an e-waste item in case it contains a component which contains that material. The final 3 rules are related to the recovery and material removal and deducing that a process recovers or removes material in case it contains a treatment step that does so. The list of rules defined for the e-waste ontology is shown in

Figure 8.

3. Results and Discussion

At this point, the e-waste ontology is well-defined and spans across all the domains previously defined within the scope of the DSS. In order to test the correctness and efficiency of the built model, it is essential to run the reasoner and verify the relations drawn amongst the various classes and individuals.

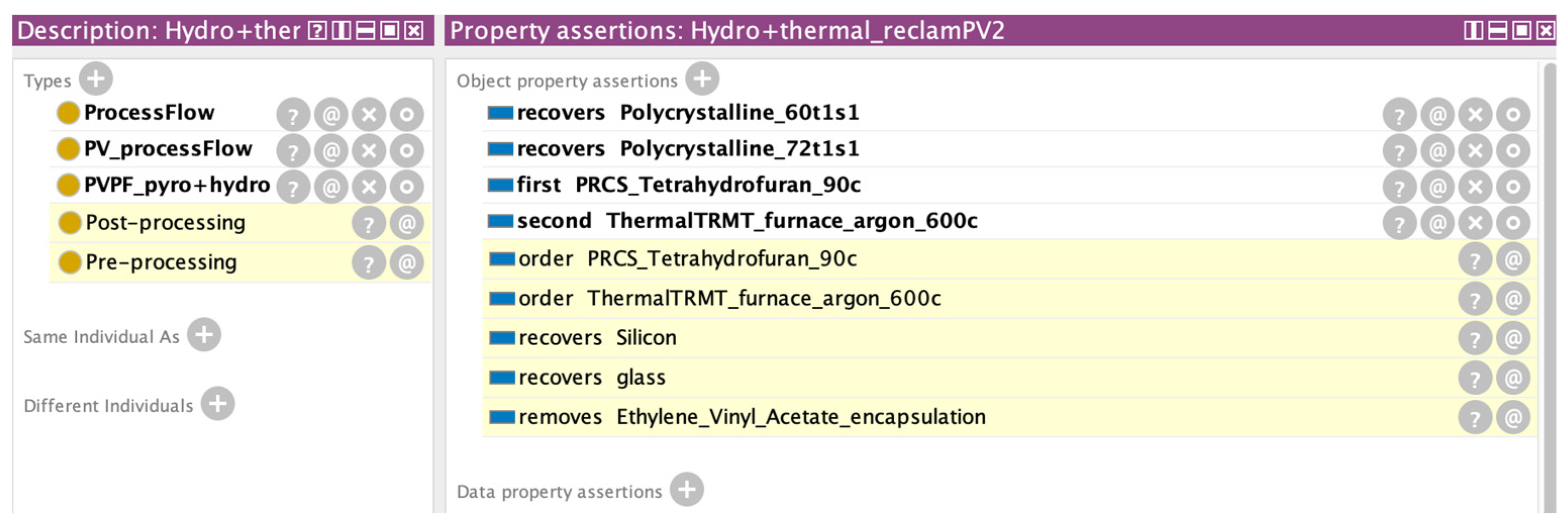

When running the reasoner, the ontology is expanded, and the new relations based on the predefined rules are associated. For example, highlighted in yellow in

Figure 9 are the inferred connections related to the individual “Hydro+thermal_reclamPV2” which is a process flow that aims to reclaim the PV from the entire panel. The reasoner concluded that since the process recovers polycrystalline PV, then it also recovers Silicon, which is the material contained within the polycrystalline object, the same applies to the EVA removed by the process. It also decides that the process can be considered as both pre-processing and post-processing treatment depending on the sequence the process is applied during the entire handling process.

The potential of the developed ontology can be further demonstrated using the SPARQL querying functionality integrated into the protégé software. SPARQL is a querying language that functions analogously to other database query languages such as SQL. SPARQL querying permits the raw usage of the developed ontology staunchly from the protégé software without the need to embed it into another program or further develop software applications, yet it requires the knowledge of the SPARQL language and thus is not tailored for non-expert users.

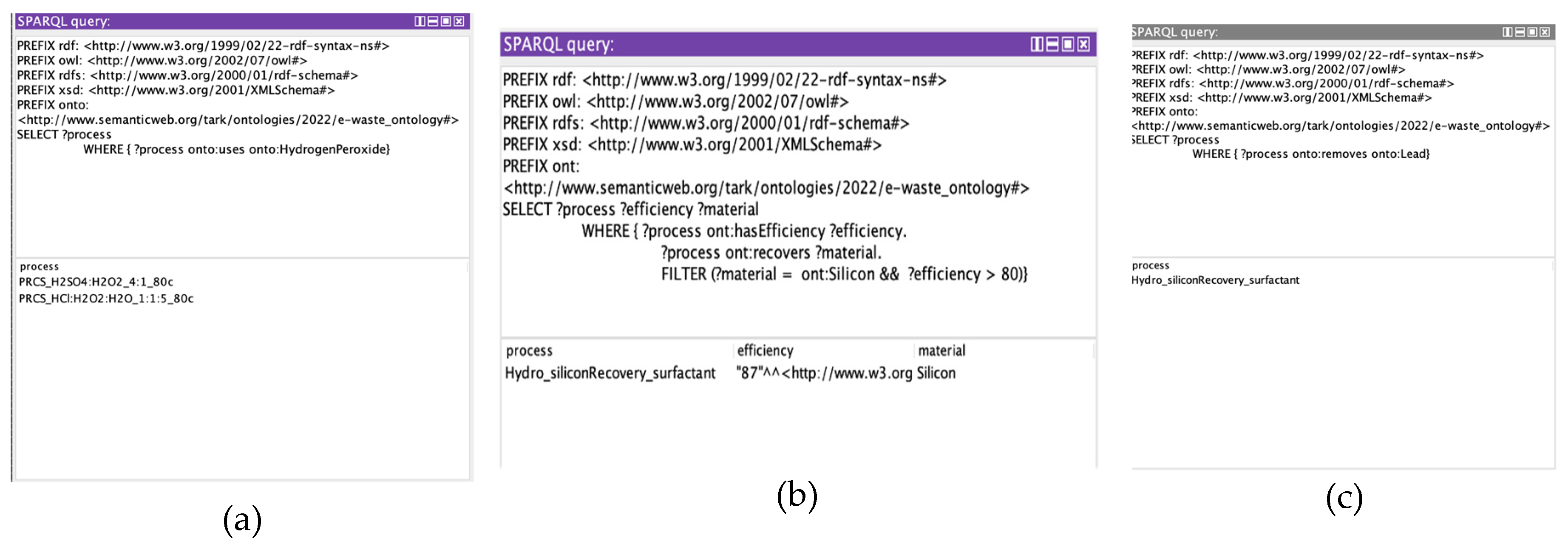

The validation of the developed ontology can be achieved by running SPARQL queries and verifying the obtained results. For instance, querying the ontology for processes that use a specific chemical agent such as hydrogen peroxide returns a list of the defined processes as shown in

Figure 10. The queries can be as general as just listing all processes which use a specific material or help remove a material of interest such as in

Figure 10 (a) and (c), which can be used in case of a preliminary search to define a starting point for a more well-defined search, or they can be more complicated such as in

Figure 10 (b) which specifies different properties and categories for the search in order to narrow down the options to include only the ones with the highest desirability of the decision-maker (in this case, the desired process is one that recovers silicon material with efficiency over 80%).

After validating the functionality and usability of the developed ontology it is more evident how the e-waste DSS would be useful and will simplify the decision-making process by extracting all the needed data to draw a crystal-clear picture about an e-waste stream and what would be the optimized approach to handle it.

While working on the e-waste ontology, a group of setbacks were identified. Firstly, the process of data extraction from the literature, beginning with finding the relevant literature passing through extracting the data, analysing it and finally feeding it into the ontology, is time-consuming as well as requires lots of human resources in case of expanding the ontology to cover a wider scope whether under the e-waste umbrella or even beyond e-waste and into other waste types. Fortunately, with the current advancement in AI, automating the data identification and extraction process can be a viable solution to mitigate such hindrances. Automating the process would not only make use of the current state-of-the-art AI solutions but would also permit a greater coverage of what is reported in the literature, identify duplicates and minimise human error. Undoubtedly, automation of the data extraction process will still require the intervention of domain experts in order to verify the data and insert them into the model, at least until the AI model is adequately developed and trained to perform such an intricate operation.

Another challenge which was identified is the lack of accurate data on the anatomical level of e-waste concerning the material content. Such a gap thwarts the full development of a holistic ontology that would offer accurate data to be used in DSSs or other applications. In most literature found and used in this ontology, material contents of different components were estimates and usually, the main categories of components were handled without diving deeper into whether there is a significant variance amongst the different models of the same components or different types of components that have similar functionalities. For instance, to our knowledge, no study investigated the different material composition of different models of printed circuit boards (PCBs) such as motherboards, central processing units (CPUs) and Random Access Memory (RAMs), and they are usually referred to with a single material composition.

For this purpose, in addition to the remaining work related to the building of the GUI for the DSS and connecting it to the e-waste ontology using the intermediate software layer, an additional part was added to the scope of work of this research to analyse the material content of some of the most common e-waste types by means of chemical analysis of collected and prepared e-waste samples using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectroscopy (ICP-MS), Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF). The data obtained would then be fed into the ontology to model the analysed components and have them ready to be integrated with future work to expand the scope of the e-waste ontology from just covering solar PVs, with potential subsequent publication of the results.

4. Conclusion

From the work presented and backed by the literature, it can be seen that an e-waste ontology is valuable given the complexity of the domain and the lack of such ontology that can be used by various stakeholders. The ontology was built in a way that adapts it to the continuously evolving nature of the domain and permits the perpetual update and integration with other projects and ontologies. The incorporation of AI is another possible future work that would further enhance the ontology and reinforce its potential while exploiting the recent advancements in computer science and AI. Such incorporation would help in maintaining the ontology updated and facilitate its assimilation with other ontologies in order to serve a wider scope with extended use cases.

Upon the completion of the ontology and its expansion to cover further types of e-waste as well as the integration with the user-friendly GUI, it is expected that the DSS would promote a more informed decision-making process and facilitate the complex task of urban mining. The benefits of such a system would contribute both directly and indirectly to the fulfilment of the UN SDGs [

31] by promoting responsible consumption and production, combating climate change, establishing new industries and developing better solid waste handling infrastructure which would indirectly contribute to wellbeing and good health as well as economic growth.

In addition to the integration of the ontology within an e-waste DSS, the ontology on its own can be used by experts or users with specific knowledge in the usage of ontologies and the protégé software in order to exploit the ontology’s standalone potential and extract data from the ontology.

This research also highlighted the need for more accurate data on the different types and models of e-waste and their materials content in order to ease their end-of-life handling and exploitation. This gap has also encouraged the initiation of ongoing research that aims to study and quantify the materials content found within different PCB types and models and the results from the study would then be fed into the ontological model in order to enhance its capacity and accuracy.

Funding

This research was funded by Eni S.p.A.

Acknowledgements

Ahmed Tarek, Francesco Laviano and Debora Fino acknowledge the support provided by Eni SpA and the PNRR NODES project. This work was conducted using Protégé.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- V. Lahtela, H. Hamod, and T. Kärki, “Assessment of critical factors in waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) plastics on the recyclability: A case study in Finland,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 830, p. 155627, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Kumar, M. Holuszko, D. Crocce, and R. Espinosa, “E-waste: An overview on generation, collection, legislation and recycling practices,” Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 122, pp. 32–42, 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Ramprasad et al., “Strategies and options for the sustainable recovery of rare earth elements from electrical and electronic waste,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 442, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Habib, M. Wagner, C. P. Baldé, L. H. Martínez, J. Huisman, and J. Dewulf, “What gets measured gets managed – does it? Uncovering the waste electrical and electronic equipment flows in the European Union,” Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 181, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Tansel, “From electronic consumer products to e-wastes: Global outlook, waste quantities, recycling challenges,” Environ Int, vol. 98, pp. 35–45, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. He, Y. Yue, and Y. Wang, “The hazards, treatment measures and sustainable development of electronic waste The hazards, treatment measures and sustainable development of electronic waste,” IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci, vol. 1011, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Faye, F. Melakessou, W. Mtalaa, P. Gautier, N. AlNaffakh, and D. Khadraoui, “SWAM: A Novel Smart Waste Management Approach for Businesses using IoT,” in Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Workshop on Technology Enablers and Innovative Applications for Smart Cities and Communities, New York, NY, USA: ACM, Nov. 2019, pp. 38–45. [CrossRef]

- M. Keet, An Introduction to Ontology Engineering. 2018. Accessed: May 05, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/590.

- A. Eibeck, M. Q. Lim, and M. Kraft, “J-Park Simulator: An ontology-based platform for cross-domain scenarios in process industry,” Comput Chem Eng, vol. 131, p. 106586, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Yu, J. Yuan, C. Cui, J. Zhao, F. Liu, and G. Li, “Ontology Framework for Sustainability Evaluation of Cement–Steel-Slag-Stabilized Soft Soil Based on Life Cycle Assessment Approach,” J Mar Sci Eng, vol. 11, no. 7, p. 1418, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Hou, H. Li, and Y. Rezgui, “Ontology-based approach for structural design considering low embodied energy and carbon,” Energy Build, vol. 102, pp. 75–90, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, X. Luo, J. J. Buis, and J. W. Sutherland, “LCA-oriented semantic representation for the product life cycle,” J Clean Prod, vol. 86, pp. 146–162, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhou, C. Zhang, I. A. Karimi, and M. Kraft, “An ontology framework towards decentralized information management for eco-industrial parks,” Comput Chem Eng, vol. 118, pp. 49–63, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Babaie, A. Davarpanah, and N. Dhakal, “Projecting Pathways to Food–Energy–Water Systems Sustainability Through Ontology,” Environ Eng Sci, vol. 36, no. 7, pp. 808–819, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Kuster, J.-L. Hippolyte, and Y. Rezgui, “The UDSA ontology: An ontology to support real time urban sustainability assessment,” Advances in Engineering Software, vol. 140, p. 102731, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Yang, C. Zuo, X. Liu, Z. Yang, and H. Zhou, “Risk Response for Municipal Solid Waste Crisis Using Ontology-Based Reasoning,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 17, no. 9, p. 3312, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Kultsova, R. Rudnev, A. Anikin, and I. Zhukova, “An ontology-based approach to intelligent support of decision making in waste management,” in 2016 7th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems & Applications (IISA), IEEE, Jul. 2016, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- A. Sinha and P. Couderc, “Using OWL Ontologies for Selective Waste Sorting and Recycling,” 2012. Accessed: Mar. 21, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://www.inria.fr/en/en/teams/aces.

- E. Muñoz, E. Capón-García, K. Hungerbühler, A. Espuña, and L. Puigjaner, “Decision Making Support based on a Process Engineering Ontology for Waste Treatment Plant Optimization,” Chem Eng Trans, vol. 32, 2013. [CrossRef]

- G. Foo, S. Kara, and M. Pagnucco, “An Ontology-Based Method for Semi-Automatic Disassembly of LCD Monitors and Unexpected Product Types”. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Musen, “Protégé.” Stanford Center for Biomedical Informatics Research, 2015.

- M. A. Musen, “The Protégé project: A look back and a look forward,” AI Matters. Association of Computing Machinery Specific Interest Group in Artificial Intelligence, vol. 1, no. 4, Jun. 2015.

- The European Parliament, Directive 2012/19/EU on waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE). 2012, pp. 38–71. Accessed: Sep. 02, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32012L0019.

- M. N. Ahmad, K. B. A. Badr, E. Salwana, N. H. Zakaria, Z. Tahar, and A. Sattar, “An Ontology for the Waste Management Domain,” PACIS 2018 Proceedings, Jun. 2018, Accessed: Jan. 06, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2018/12.

- I. Sosunova, A. Zaslavsky, T. Anagnostopoulos, P. Fedchenkov, O. Sadov, and A. Medvedev, “SWM-PnR: Ontology-Based Context-Driven Knowledge Representation for IoT-Enabled Waste Management,” in Internet of Things, Smart Spaces, and Next Generation Networks and Systems., Springer, Cham, 2017, pp. 151–162. [CrossRef]

- L. Ceccaroni, U. Cortés, and M. Sànchez-Marrè, “OntoWEDSS: augmenting environmental decision-support systems with ontologies,” Environmental Modelling & Software, vol. 19, pp. 785–797, 2004. [CrossRef]

- J. Morbach, A. Yang, and W. Marquardt, “OntoCAPE—A large-scale ontology for chemical process engineering,” Eng Appl Artif Intell, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 147–161, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- C. E. L. Latunussa, F. Ardente, G. A. Blengini, and L. Mancini, “Life Cycle Assessment of an innovative recycling process for crystalline silicon photovoltaic panels,” Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, vol. 156, pp. 101–111, 2016. [CrossRef]

- T.-Y. Wang, J.-C. Hsiao, and C.-H. Du, “Recycling of materials from silicon base solar cell module,” in 2012 38th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, IEEE, Jun. 2012, pp. 002355–002358. [CrossRef]

- B. Motik, R. Shearer, B. Glimm, G. Stoilos, and I. Horrocks, “HermiT Reasoner.” Department of Computer Science in the University of Oxford, Oxford. Accessed: Jul. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.hermit-reasoner.com/index.html.

- United Nations, “Sustainable Development Goals: 17 goals to transform our world,” United Nations. Accessed: Apr. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/summit/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).