Submitted:

11 August 2024

Posted:

12 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

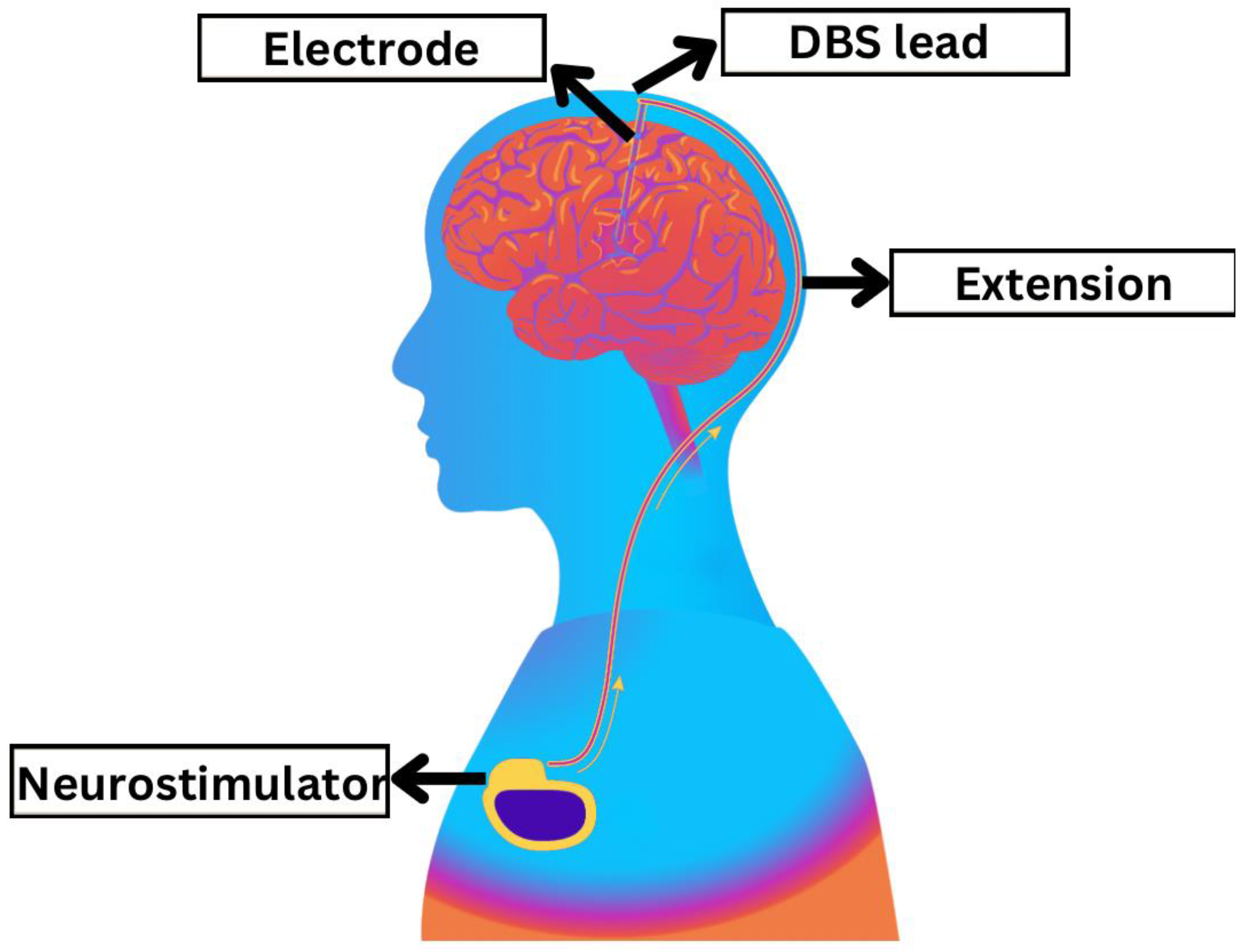

Introduction

Methods

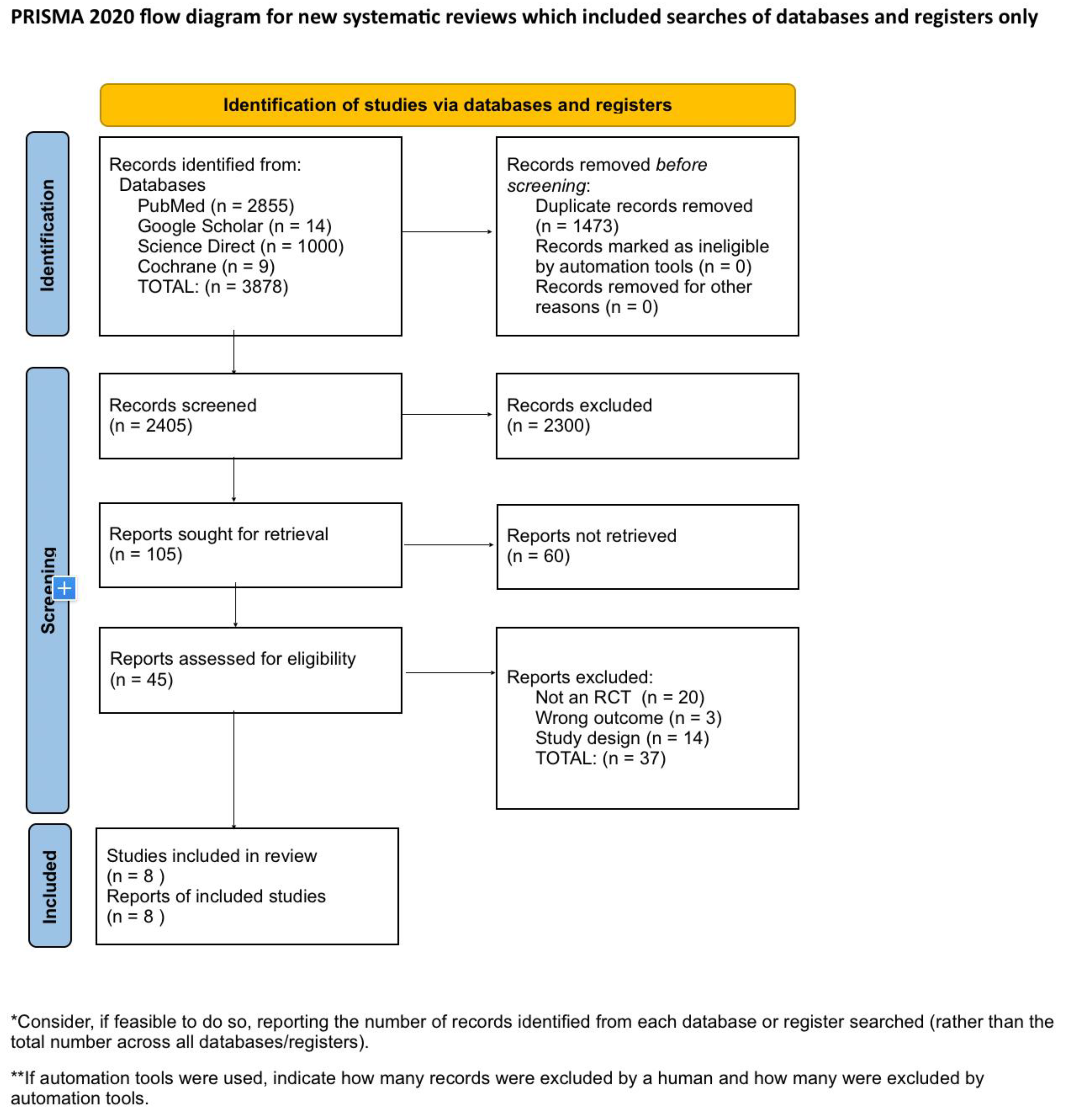

Systematic Literature Search and Study Selection

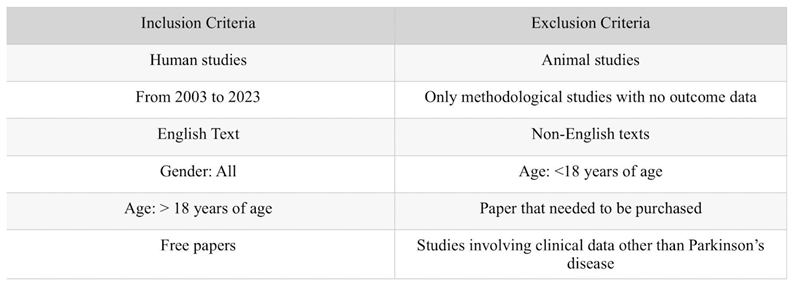

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Search Strategy

Quality Appraisal

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

References

- Collaborators GBDN. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):459–480.

- Dorsey ER, Elbaz A, Nichols E, Abd-Allah F, Abdelalim A, Adsuar JC. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):939–953.

- Rocca WA. The burden of Parkinson’s disease: a worldwide perspective. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):928–929.

- Prenger MT, Madray R, Van Hedger K, Anello M, MacDonald PA. Social symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s Dis. 2020;2020(1):8846544.

- Limousin P, Pollak P, Benazzouz A, et al. Effect of parkinsonian signs and symptoms of bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation. Lancet. 1995;345:91–95.

- Chia SJ, Tan EK, Chao YX. Historical perspective: models of Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(7):2464. Published 2020 Apr 2. [CrossRef]

- Obeso JA, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Goetz CG, Marin C, Kordower JH, Rodriguez M, et al. Missing pieces in the Parkinson’s disease puzzle. Nat Med. 2010;16:653–661.

- Jankovic J. Parkinson’s disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:368–376.

- Obeso JA, Stamelou M, Goetz CG, et al. Past, present, and future of Parkinson’s disease: a special essay on the 200th anniversary of the shaking palsy. Mov Disord. 2017;32:1264–1310.

- Armstrong MJ, Okun MS. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease. JAMA. 2020;323:548–560.

- Marras C, Lang A, van de Warrenburg BP, et al. Nomenclature of genetic movement disorders: recommendations of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society Task Force. Mov Disord. 2016;31:436–457.

- Deng H, Wang P, Jankovic J. The genetics of Parkinson disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;42:72–85.

- Ascherio A, Schwarzschild MA. The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease: risk factors and prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:1257–1272.

- Simon DK, Tanner CM, Brundin P. Parkinson disease epidemiology, pathology, genetics, and pathophysiology. Clin Geriatr Med. 2020;36:1–12.

- González-Casacuberta I, Juárez-Flores DL, Morén C, et al. Bioenergetics and autophagic imbalance in patients-derived cell models of Parkinson disease supports systemic dysfunction in neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:894.

- Pohl C, Dikic I. Cellular quality control by the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Science. 2019;366:818–822.

- Pires AO, Teixeira FG, Mendes-Pinheiro B, Serra SC, Sousa N, Salgado AJ. Old and new challenges in Parkinson’s disease therapeutics. Prog Neurobiol. 2017;156:69–89.

- Espay AJ, Brundin P, Lang AE. Precision medicine for disease modification in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(2):119–126.

- Paolini Paoletti F, Gaetani L, Parnetti L. The challenge of disease-modifying therapies in Parkinson’s disease: role of CSF biomarkers. Biomolecules. 2020;10(2):335.

- Fahn S, Elton R, Members of the UPDRS Development Committee. Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. In: Fahn S, Marsden CD, Calne DB, Goldstein M, editors. Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease. Florham Park, NJ: Macmillan Health Care Information; 1987. p. 153–164.

- de Tosin MHS, Goetz CG, Luo S, Choi D, Stebbins GT. Item response theory analysis of the MDS-UPDRS III motor examination: tremor vs nontremor items. Mov Disord. 2020;35(9):1587–1595.

- Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord. 2008;23(15):2129–2170.

- Rajan R, Brennan L, Bloem BR, et al. Integrated care in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2020;35(9):1509–1531.

- Bellini G, Best LA, Brechany U, Mills R, Pavese N. Clinical impact of deep brain stimulation on the autonomic system in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2020;7(4):373-382.

- Krauss JK, Lipsman N, Aziz T, Boutet A, Brown P, Chang JW, et al. Technology of deep brain stimulation: current status and future directions. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021 Feb;17(2):75-87. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Ramirez D, Hu W, Bona AR, Okun MS, Shukla AW. Update on deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Transl Neurodegener. 2015;4:1-8.

- Baizabal-Carvallo JF, Kagnoff MN, Jimenez-Shahed J, Fekete R, Jankovic J. The safety and efficacy of thalamic deep brain stimulation in essential tremor: 10 years and beyond. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(5):567–572.

- Vercueil L, Pollak P, Fraix V, et al. Deep brain stimulation in the treatment of severe dystonia. J Neurol. 2001;248(8):695–700.

- Kurcova S, Bardon J, Vastik M, et al. Bilateral subthalamic deep brain stimulation initial impact on nonmotor and motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: an open prospective single institution study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(5).

- Khoo HM, Kishima H, Hosomi K, Maruo T, Tani N, Oshino S, et al. Low-frequency subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized clinical trial. Mov Disord. 2014;29(2):270–274.

- Xie T, Padmanaban M, Bloom L, MacCracken E, Bertacchi B, Dachman A, et al. Effect of low versus high frequency stimulation on freezing of gait and other axial symptoms in Parkinson patients with bilateral STN DBS: a mini-review. Transl Neurodegener. 2017;6:13.

- Benabid AL. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13(6):696–706.

- Hartwigsen G. The neurophysiology of language: insights from non-invasive brain stimulation in the healthy human brain. Brain Lang. 2015;148:81–94. [CrossRef]

- Hogg E, Wertheimer J, Graner S, Tagliati M. Deep brain stimulation and nonmotor symptoms. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2017;134:1045–1089. [CrossRef]

- Weaver FM, et al. Bilateral deep brain stimulation vs best medical therapy for patients with advanced Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(1):63–73. [CrossRef]

- Williams A, et al. Deep brain stimulation plus best medical therapy versus best medical therapy alone for advanced Parkinson’s disease (PD SURG trial): a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(6):581–591.

- Conway ZJ, Silburn PA, Perera T, O’Maley K, Cole MH. Low-frequency STN-DBS provides acute gait improvements in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blinded randomised cross-over feasibility trial. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2021;18(1):125. Published 2021 Aug 10. [CrossRef]

- Momin S, Mahlknecht P, Georgiev D, et al. Impact of subthalamic deep brain stimulation frequency on upper limb motor function in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2018;8(2):267-271. [CrossRef]

- Merola A, Zibetti M, Artusi CA, et al. 80 Hz versus 130 Hz subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation: effects on involuntary movements. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19(4):453-456. [CrossRef]

- Phibbs FT, Arbogast PG, Davis TL. 60-Hz frequency effect on gait in Parkinson’s disease with subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation. Neuromodulation. 2014;17(8):717-720. [CrossRef]

- Ramdhani RA, Watts J, Kline M, Fitzpatrick T, Niethammer M, Khojandi A. Differential spatiotemporal gait effects with frequency and dopaminergic modulation in STN-DBS. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1206533. Published 2023 Sep 29. [CrossRef]

- Tsang EW, Hamani C, Moro E, et al. Subthalamic deep brain stimulation at individualized frequencies for Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2012;78(24):1930-1938. [CrossRef]

- Xie T, Vigil J, MacCracken E, et al. Low-frequency stimulation of STN-DBS reduces aspiration and freezing of gait in patients with PD. Neurology. 2015;84(4):415-420. [CrossRef]

- Fagundes VC, Rieder CR, da Cruz AN, Beber BC, Portuguez MW. Deep brain stimulation frequency of the subthalamic nucleus affects phonemic and action fluency in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2016;2016:6760243. [CrossRef]

- Little S, Pogosyan A, Neal S, Zavala B, Zrinzo L, Hariz M, et al. Adaptive deep brain stimulation in advanced Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(3):449-457.

- Paff M, Loh A, Sarica C, Lozano AM, Fasano A. Update on current technologies for deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. J Mov Disord. 2020;13(3):185-198. [CrossRef]

- Williams A, Gill S, Varma T, Jenkinson C, Quinn N, Mitchell R, et al. Deep brain stimulation plus best medical therapy versus best medical therapy alone for advanced Parkinson’s disease (PD SURG trial): a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:581–591.

- Odekerken VJJ, van Laar T, Staal MJ, Mosch A, Hoffmann CF, Nijssen PC, et al. Subthalamic nucleus versus globus pallidus bilateral deep brain stimulation for advanced Parkinson’s disease (NSTAPS study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:37–44.

- Smith J, Doe A. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease: a review. Neurology. 2023;98(4):123-130.

- Garcia L, d’Alessandro G, Bioulac B, Hammond C. High-frequency stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: more or less?. Trends Neurosci. 2005 Apr 1;28(4):209-16.

- Kühn AA, Kempf F, Brücke C, Gaynor Doyle L, Martinez-Torres I, Pogosyan A, Trottenberg T, Kupsch A, Schneider GH, Hariz MI, Vandenberghe W, Nuttin B, Brown P. High-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus suppresses oscillatory beta activity in patients with Parkinson’s disease in parallel with improvement in motor performance. J Neurosci. 2008 Jun 11;28(24):6165-73. PMID: 18550758; PMCID: PMC6670522. [CrossRef]

- Varanese S, Birnbaum Z, Rossi R, Di Rocco A. Treatment of advanced Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2011 Feb 7;2010:480260. PMID: 21331376; PMCID: PMC3038575. [CrossRef]

- Deep-Brain Stimulation for Parkinson’s Disease Study Group. Obeso JA, Olanow CW, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Krack P, Kumar R, Lang AE. Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus or the pars interna of the globus pallidus in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:956–963.

- Moreau C, Defebvre L, Destée A, Bleuse S, Clement F, Blatt JL, et al. STN-DBS frequency effects on freezing of gait in advanced Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;71:80–84.

- Khoo HM, Kishima H, Hosomi K, Maruo T, Tani N, Oshino S, et al. Low-frequency subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized clinical trial. Mov Disord. 2014;29:270–274.

| Databases | Search Strategy | Result |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ((((((((Deep Brain Stimulation[MeSH Terms]) OR (DBS[Title/Abstract])) OR (Electrical Stimulation of the brain[Title/Abstract])) AND (Parkinson Disease[MeSH Terms])) OR (PD[Title/Abstract])) OR (Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease[Title/Abstract])) OR (Parkinson’s Disease[Title/Abstract])) OR (Primary Parkinsonism[Title/Abstract])) AND (Low frequency[Title/Abstract] OR high frequency[Title/Abstract]) | 2349 (2024/05/21) 1391 Filters applied: From 2000 to 2024 Humans English MEDLINE |

| (((((Parkinson Disease[MeSH Terms]) OR (Idiopathic, Parkinson Disease[Title/Abstract])) OR (Idiopathic, Parkinson’s Disease[Title/Abstract])) OR (Idiopathic Parkinson Disease[Title/Abstract])) AND (((Deep Brain Stimulation[MeSH Terms]) OR (Deep Brain Stimulations[Title/Abstract])) OR (Brain Stimulation, Deep[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((High frequency deep brain stimulation[Title/Abstract]) OR (Low frequency deep brain stimulation[Title/Abstract])) | 52 (2024/05/22) 49 Filters applied: Humans English |

|

| (((((Parkinson Disease[MeSH Terms]) OR (Primary Parkinsonism[Title/Abstract])) OR (Paralysis Agitans[Title/Abstract])) OR (PD[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((Deep Brain Stimulation[MeSH Terms]) OR (Deep Brain Stimulations[Title/Abstract])) OR (Electrical Stimulation of the Brain[Title/Abstract])) OR (DBS[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((High frequency[Title/Abstract]) AND (Low frequency[Title/Abstract])) | 104 (2024/05/23) 71 Filters applied: Humans English |

|

| („Deep Brain Stimulation”[Mesh] OR „Deep Brain Stimulation”) AND („Parkinson Disease”[Mesh] OR „Parkinson’s Disease”) AND („Low frequency” OR „High frequency”) | 795 (2024/05/23) 174 Filters applied: Free full text Humans English MEDLINE |

|

| („Deep Brain Stimulation”[Mesh] OR „Deep Brain Stimulation”) AND („Parkinson Disease”[Mesh] OR „Parkinson’s Disease”) AND („Stimulation Frequency” OR „Low-frequency Stimulation” OR „High-frequency Stimulation”) | 416 (2024/05/23) 246 Filters applied: Humans English MEDLINE |

|

| Google Scholar | („Deep Brain Stimulation” OR DBS OR „brain stimulation”) AND („Parkinson Disease” OR Parkinson OR PD) AND (High-frequency OR Low-frequency OR „different frequencies”) AND („comparative study” OR effectiveness OR comparison) | 18,800 ONLY English 17,700 |

| Cochrane Library | ID Search #1 MeSH descriptor: [Deep Brain Stimulation] explode all trees #2 (deep brain stimulation* OR electrical stimulation of the brain OR DBS):ti,ab,kw #3 MeSH descriptor: [Parkinson Disease] explode all trees #4 (Parkinson* disease OR Idiopathic parkinson* disease OR Primary Parkinsonism OR Paralysis agitans OR Hypokinetic rigid syndrome OR Shaking palsy):ti,ab,kw #5 (High frequency stimulation AND Low frequency stimulation):ti,ab,kw #6 (#1 OR #2) AND (#3 OR #4) AND #5 |

59 (2024/05/16) |

| Science Direct | (Parkinson’s disease) AND (Deep Brain Stimulation) AND (Low frequency OR High frequency) AND (impact OR efficacy OR outcomes) | 13,629 (2024/05/18) 1,327 Filters applied: Review articles Research articles Neuroscience Medicine and Dentistry English Open access and open archive |

| Author, year | Country | Study Design | Number of patients | Medication (On/Off) | Intervention | LFS/HFS value | Follow up duration | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conway et al., 2021 [37] | Australia | Randomized double blinded | 14 | Off | Bilateral STN-DBS | 60 Hz/ 100 Hz | No long term follow up | The research revealed that low-frequency (60 Hz) STN-DBS notably enhanced gait rhythmicity, particularly medial-lateral and vertical trunk rhythmicity, in Parkinson’s disease patients compared to high-frequency stimulation. These enhancements were not influenced by the electrode location, or the total electrical energy administered. However, no significant variances were detected between the two stimulation conditions in terms of temporal gait measures, clinical mobility measures, motor symptom severity, or the presence of gait retropulsion. The study suggests that low-frequency STN-DBS may provide immediate advantages for gait stability in PD patients. |

| Momin et al., 2018 [38] | UK | Randomized double blinded | 20 | Off | Bilateral STN-DBS | 40 Hz - 160 Hz | No long term follow up | The research examined the impact of different STN-DBS frequencies on upper limb motor function in patients with Parkinson’s disease. The study did not find a consistent influence of frequency on bradykinesia using both the Simple PP task and a modified upper limb version of the UPDRS-III. However, there was a notable improvement in the Assembly PP task at 80 Hz compared to the baseline frequency of 130 Hz, indicating enhanced phasic alertness and divided attention at the lower frequency. Furthermore, tremor and rigidity were better managed at higher frequencies (>80 Hz). The overall conclusion suggests that both high and low frequencies can be effective without exacerbating bradykinesia. |

| Merola et al., 2013 [39] | Italy | Non-randomized single blinded | 10 | On | Bilateral STN-DBS | 80 Hz / 130 Hz | 1 and 12 months | The results of the study demonstrate that adjusting the subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN-DBS) frequency from 130 Hz to 80 Hz leads to a significant reduction in involuntary movements (IM) such as dyskinesias and dystonia in Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients. Dyskinesias improved in all patients, and dystonic features improved in most patients after one month of 80 Hz stimulation. However, in some patients, there was a gradual worsening of parkinsonian symptoms, necessitating a return to 130 Hz stimulation. This indicates that while 80 Hz STN-DBS may effectively address IM in certain patients, others may require higher frequencies to uphold overall motor function. |

| Phibbs et al., 2014 [40] | USA | Randomized double blinded | 20 | Off | Bilateral STN-DBS | 60 Hz / 130 Hz | No long term follow up | The study findings revealed that there was no significant variance in gait improvement observed in Parkinson’s disease patients who underwent subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation at 60 Hz versus 130 Hz. The primary measure of improvement, stride length, did not show any significant enhancement at the lower frequency. Furthermore, secondary gait parameters such as velocity and cadence also exhibited no notable differences. While there was a tendency towards reduced double limb support time at 60 Hz, it was not deemed statistically significant. As a result, the study concluded that lower frequency stimulation did not yield the anticipated improvement in gait performance. |

| Ramdhani et al., 2023 [41] | USA | Randomized double blinded | 22 | On/Off | Bilateral STN-DBS | 60 Hz / 180 Hz | No long term follow up | The research indicates that both high-frequency (HFS) and low-frequency (LFS) subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN-DBS) yield similar impacts on most lower limb gait features in individuals with advanced Parkinson’s disease. However, considerable enhancements in trunk and lumbar kinematics were noted with HFS. In addition, stimulation from ventral electrode contacts elicited more favorable responses compared to dorsal contacts. These findings suggest that customized STN-DBS settings may have the potential to improve gait and decrease the risk of falls in Parkinson’s disease patients. |

| Tsang et al., 2012 [42] | Canada | Randomized double blinded | 13 | On/Off | Bilateral STN-DBS | 4-10 Hz, 11-30 Hz, 31-100 Hz, >130 Hz | No long term follow up | The research findings indicate that customizing deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus at beta frequencies ranging from 31 to 100 Hz markedly enhances motor symptoms in individuals with Parkinson’s disease, similar to the effects of traditional high-frequency stimulation. Meanwhile, alpha (4–10 Hz) and theta (11–30 Hz) frequency stimulations did not exacerbate motor symptoms, indicating that these frequencies may be indicative of disease progression rather than directly contributing to symptoms. indicates that patient-specific DBS frequencies can be effective, but further long-term studies are needed to validate these findings and optimize DBS therapy for Parkinson’s disease. |

| Xie T. et al., 2014 [43] | USA | Randomized double blinded | 7 | On | Bilateral STN-DBS | 60 Hz / 130 Hz | 6 weeks | The results of the study indicate that 60-Hz stimulation has a significant positive impact on swallowing function, freezing of gait (FOG), and overall axial and motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease patients with bilateral subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN-DBS) in comparison to the commonly used 130-Hz stimulation. The 60-Hz setting notably reduces aspiration frequency and subjective swallowing difficulty, with sustained improvements in FOG and axial symptoms observed over a six-week period.‘s design minimized carryover effects and suggested that 60-Hz stimulation could |

| Fagundes et al., 2016 [44] | Brazil | Randomized double blinded | 20 | On | Bilateral STN-DBS | 60 Hz / 130 Hz | No long term follow up | The research indicates that the frequency of subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN-DBS) has a significant impact on verbal fluency (VF) in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Lower frequency stimulation at 60 Hz showed notable improvements in phonemic and action fluency compared to higher frequency stimulation at 130 Hz. This finding was consistent across various tasks and was not affected by practice, demographic factors, cognitive abilities, or clinical variables. The study recommends prioritizing low-frequency stimulation in Parkinson’s disease patients, particularly in those with cognitive impairments affecting verbal fluency, to minimize any adverse effects. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).