Submitted:

10 August 2024

Posted:

12 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Management

2.2. Experimental Design

- Treatment group (n = 25)

- Control group (n = 19)

2.3. Blood Sample Collection for Hormone and Antioxidant Marker Analyses

2.3.1. Hormone Assay

2.3.2. Antioxidant Marker

2.4. Animal Handling and Ovum Pickup (OPU) Procedure

2.5. In-Vitro Maturation (IVM) of COCs

2.6. In-Vitro Fertilization (IVF)

| Commercial IVF media of ABS, USA | = | 1ml |

| PHE (D-penicillamine, hypotaurine and epinephrine) | = | 44µl/ml |

| Heparin | = | 11µl/ml |

| Commercial antibiotic solution of ABS | = | 10µl/ml |

| (Mixed properly and filtered prior to use) | ||

2.7. In-Vitro Culture (IVC)

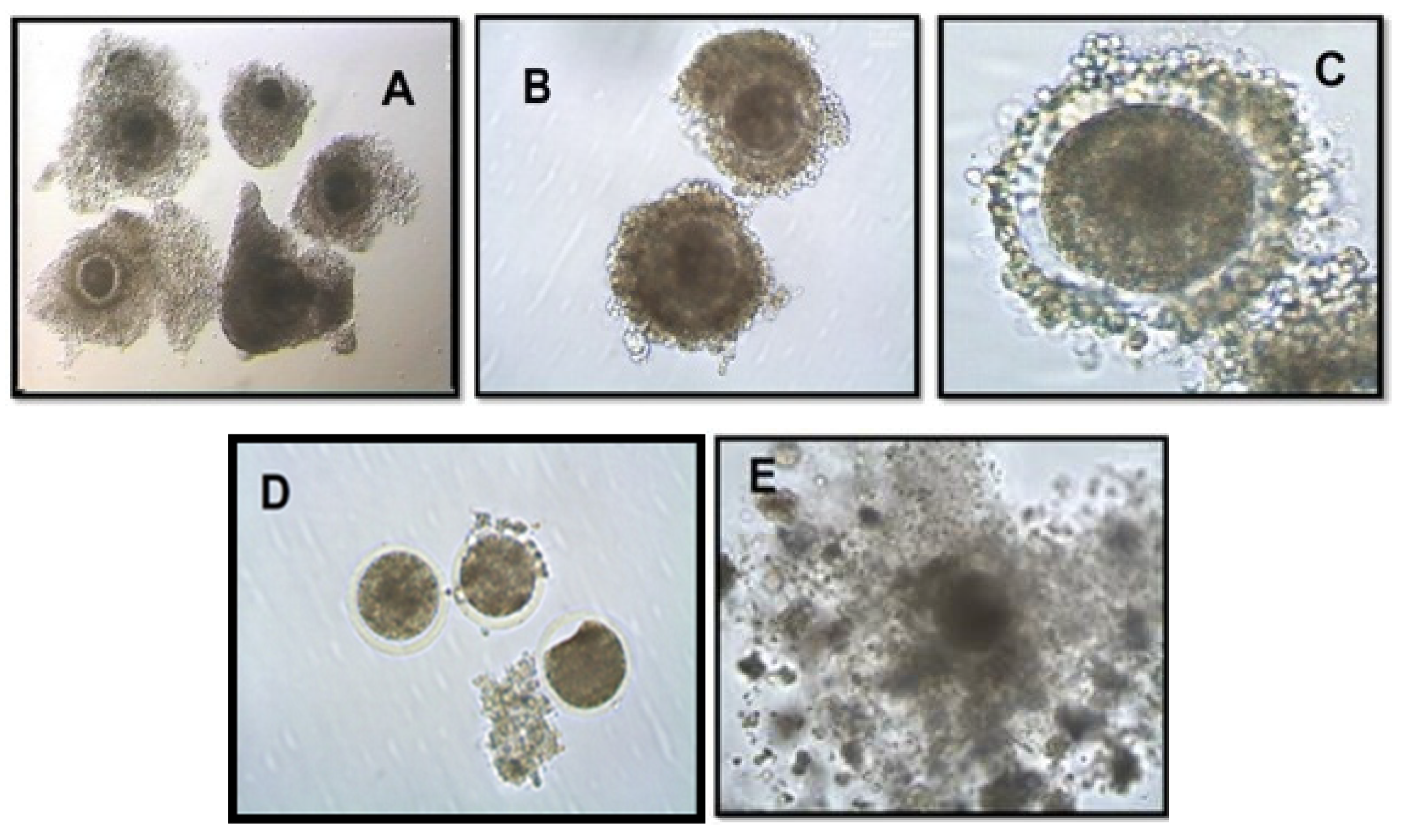

Developmental Stages of Embryos

2.8. Fresh Embryo Transfers in Recipient Animals

2.9. Assessment of Cleavage Rate

2.10. Assessment of Blastocyst Development Rate

2.11. Gene Expression Analysis of Cattle Oocytes, Cumulus Cells, Immature as Well as Mature COCs, and Blastocyst of Both Melatonin-Treated and Control Group

2.11.1. Extraction of RNA

2.11.2. Preparation of cDNA

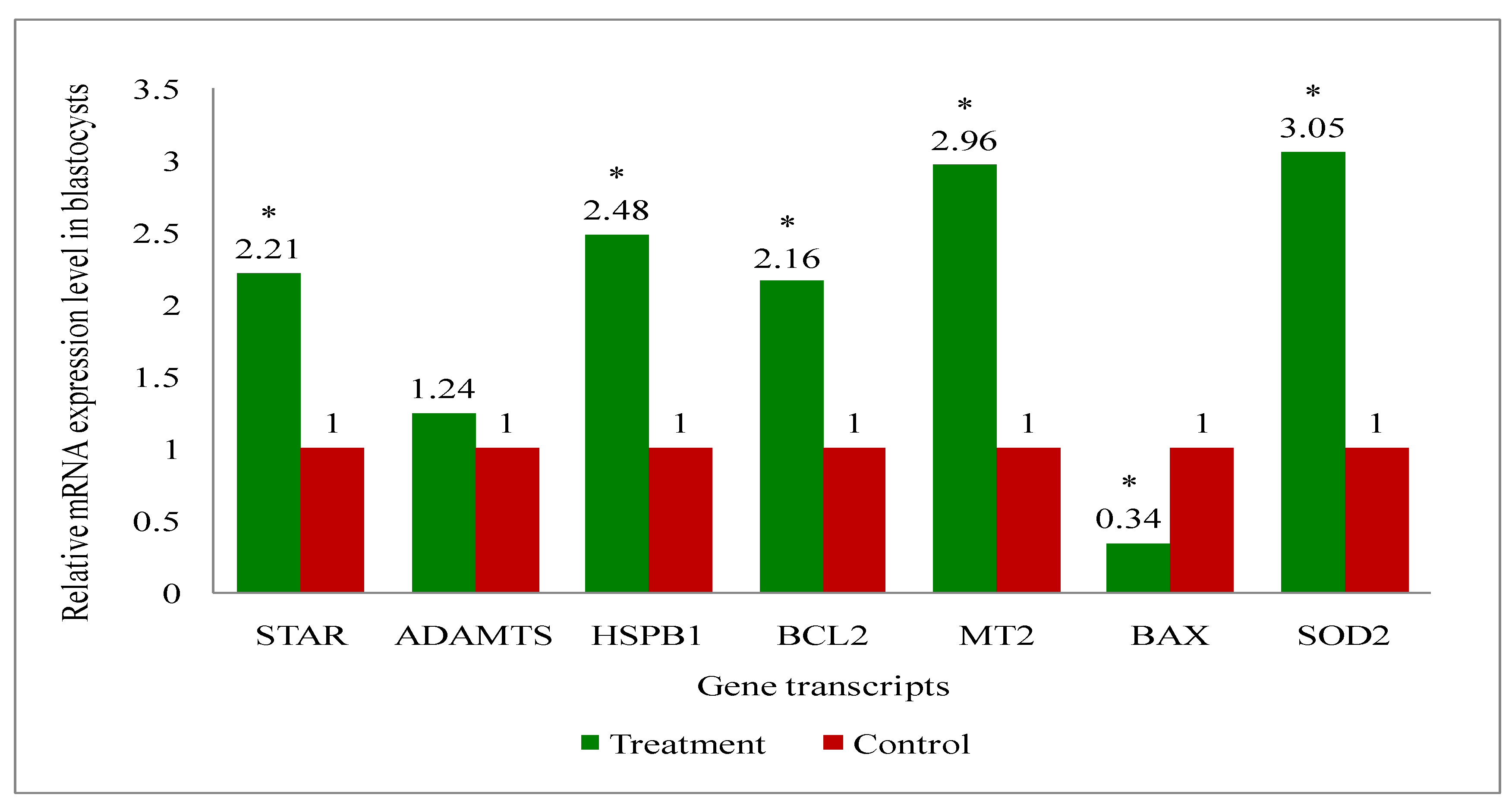

2.11.3. Expression Analysis of STAR, ADAMTS, HSPB1, BCL2, MT2, BAX, SOD2 and GAPDH (Endogenous Control) Gene Transcript by RT-qPCR

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

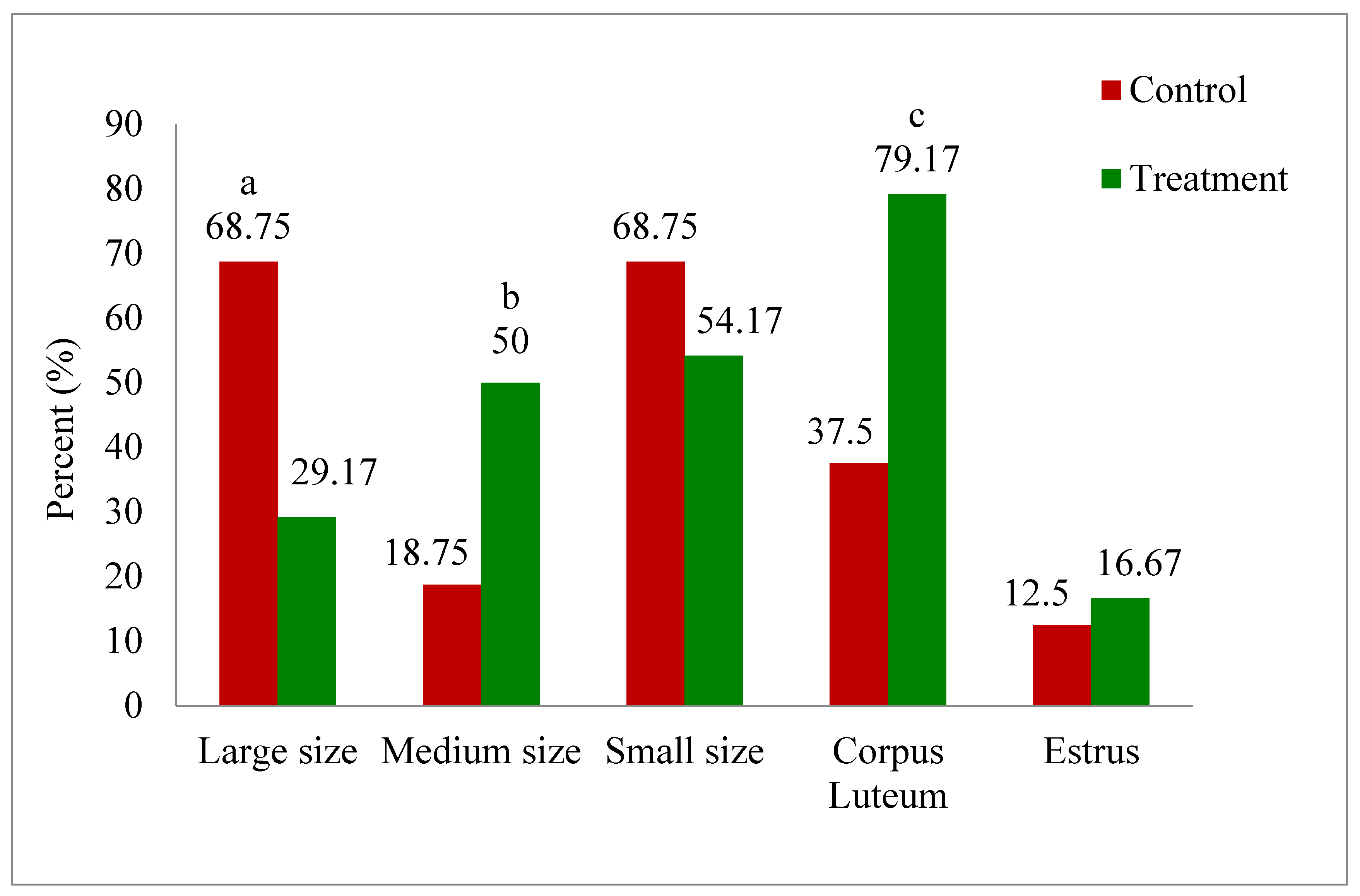

3.1. Effect of Melatonin Treatment on Ovarian Dynamics

3.2. Effect of Exogenous Melatonin on IVF Embryo Developmental Potential of Oocytes

3.3. Effects of Melatonin on Plasma Hormone (Melatonin, Estradiol and Progesterone) Profile

3.4. Effect of Melatonin on Antioxidant Markers (SOD, GSH and MDA) Profile

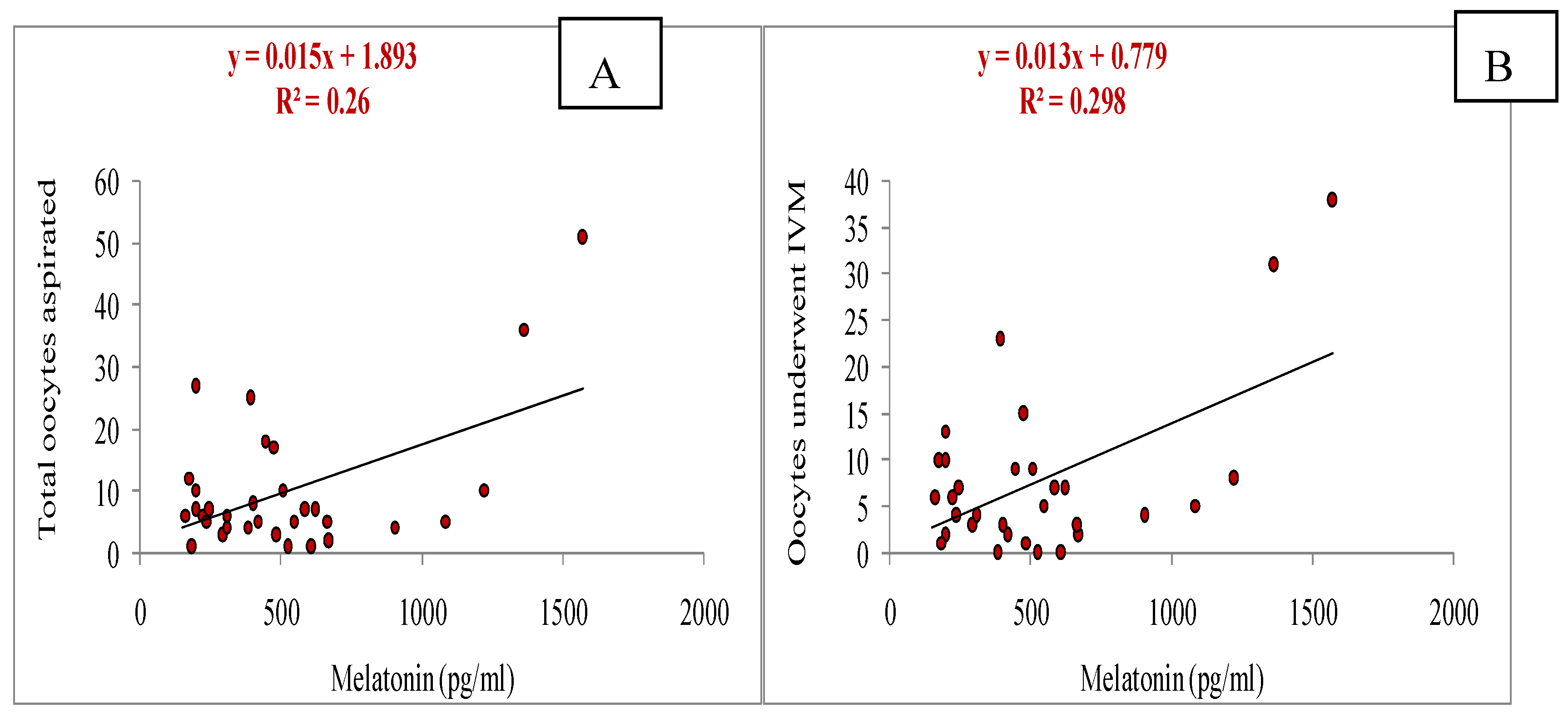

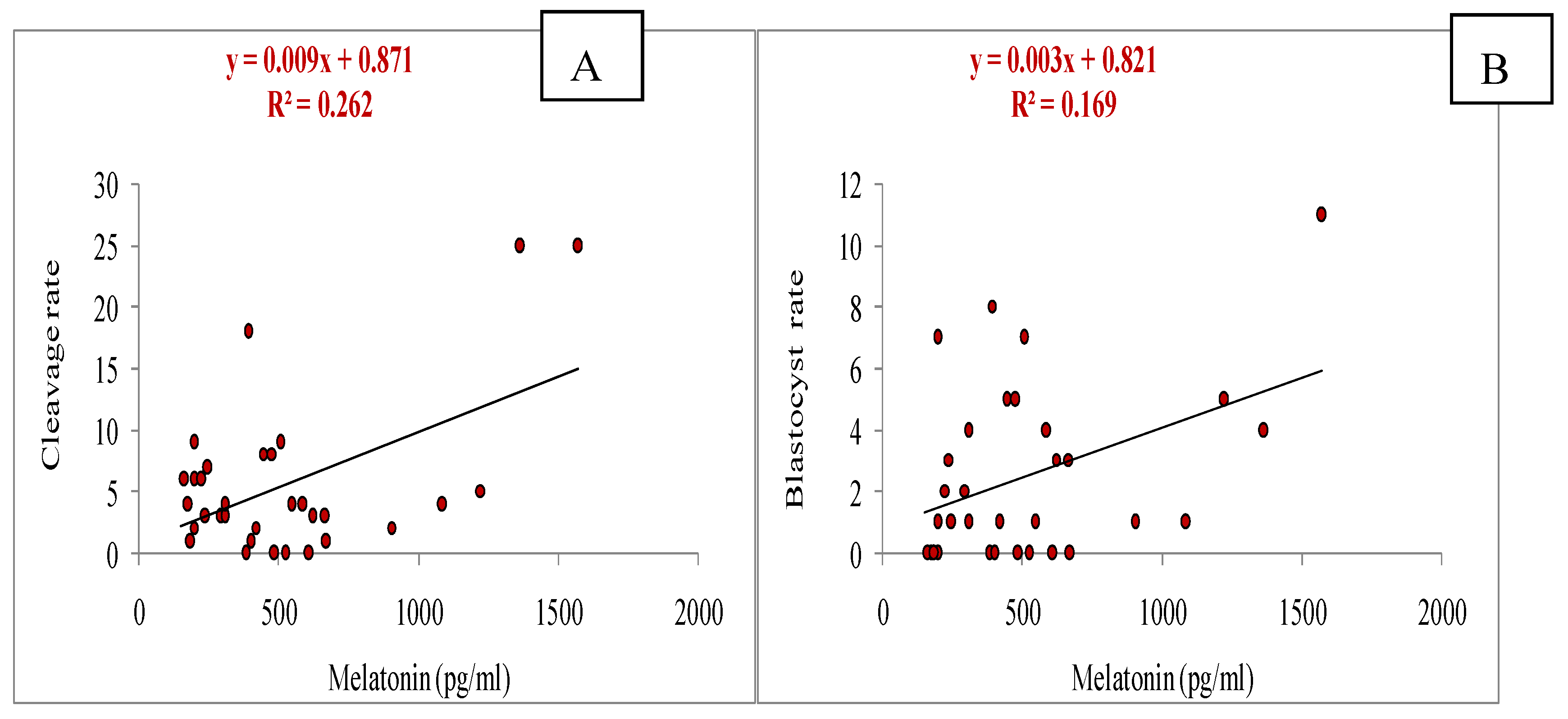

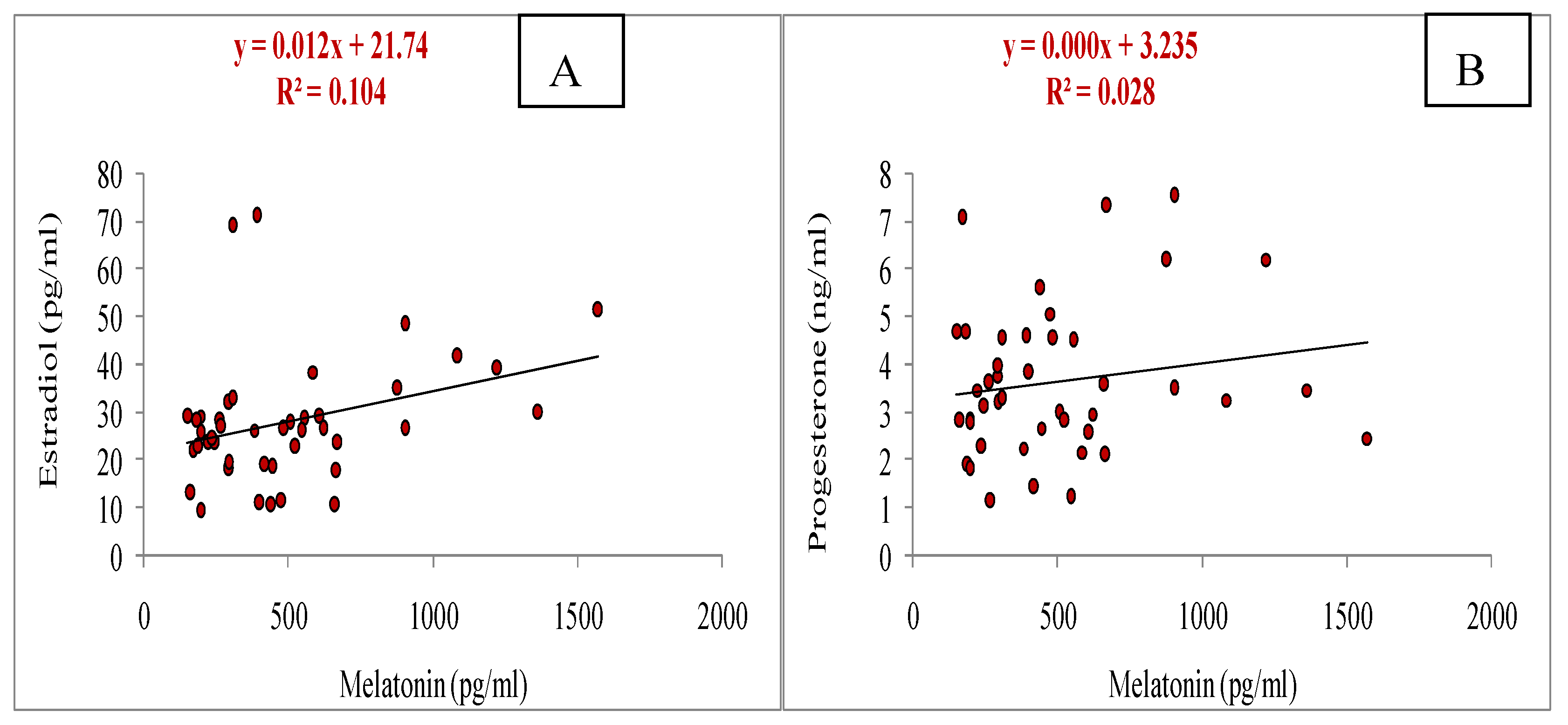

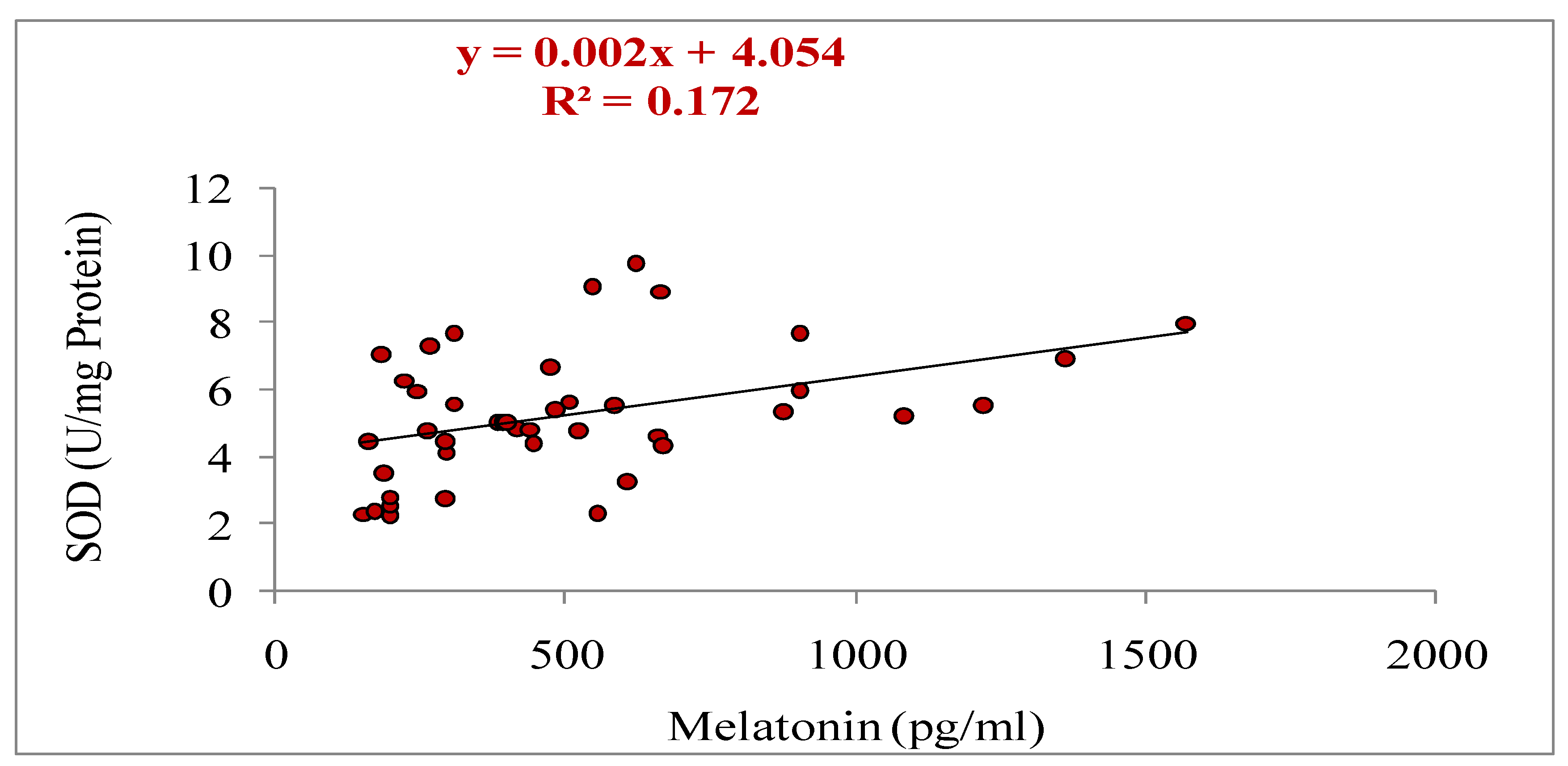

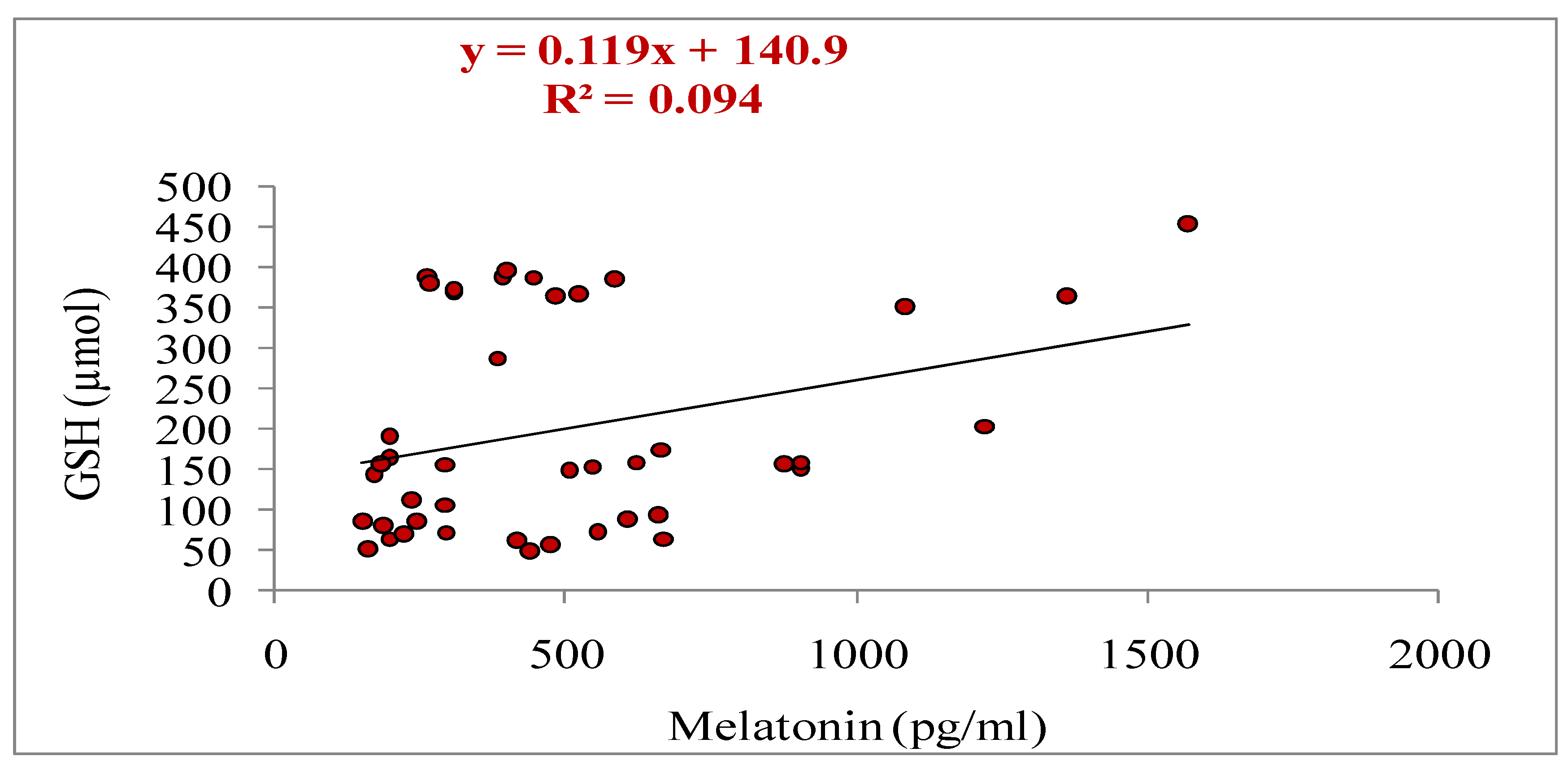

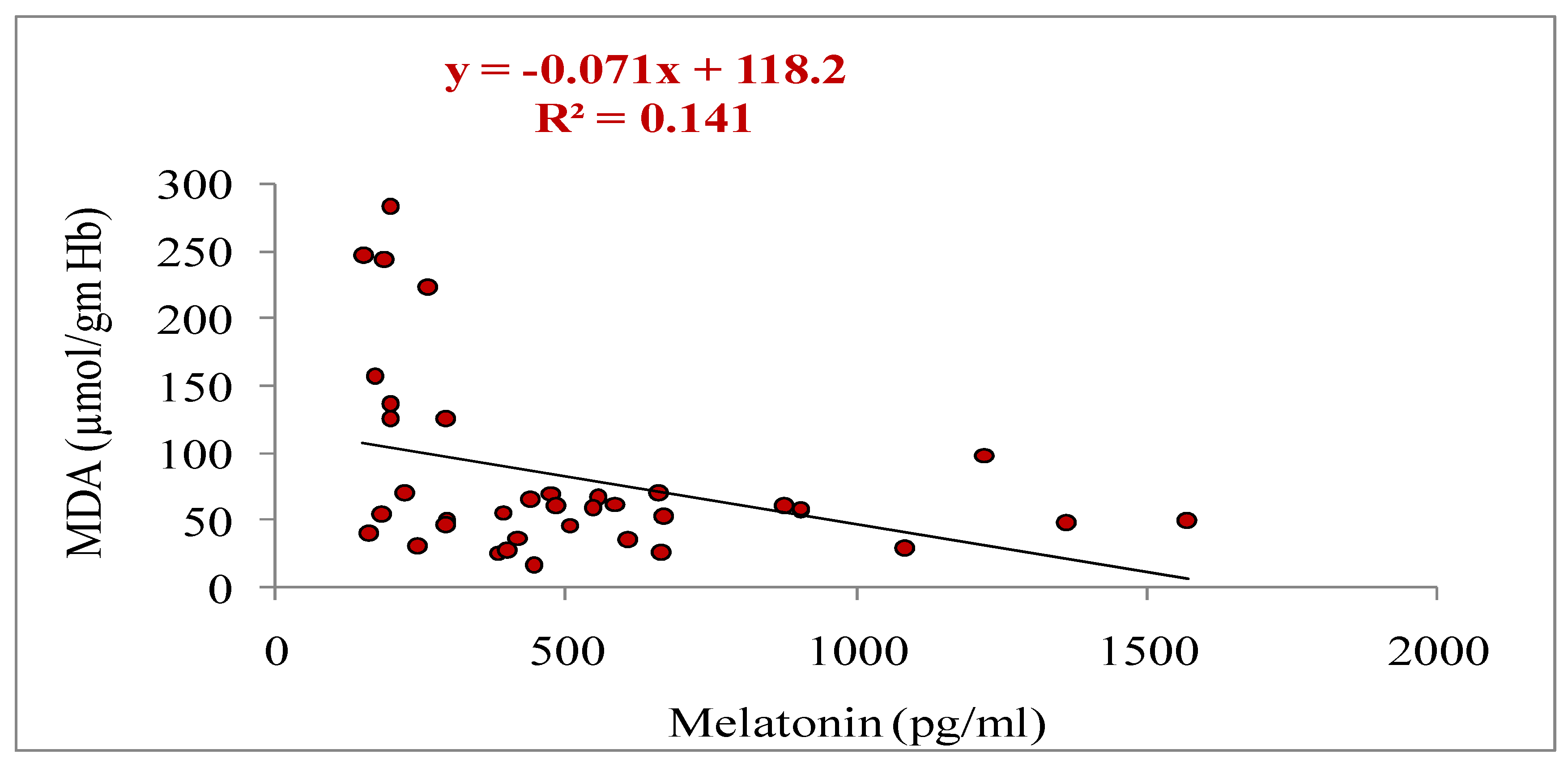

3.5. Relationship of Melatonin with Different Parameters (Total Numbers of Oocytes Aspirated, Total Numbers of Oocytes Underwent for IVM, Cleavage and Blastocyst Rate, Estradiol and Progesterone Concentrations, and Antioxidant Markers: SOD, GSH and MDA)

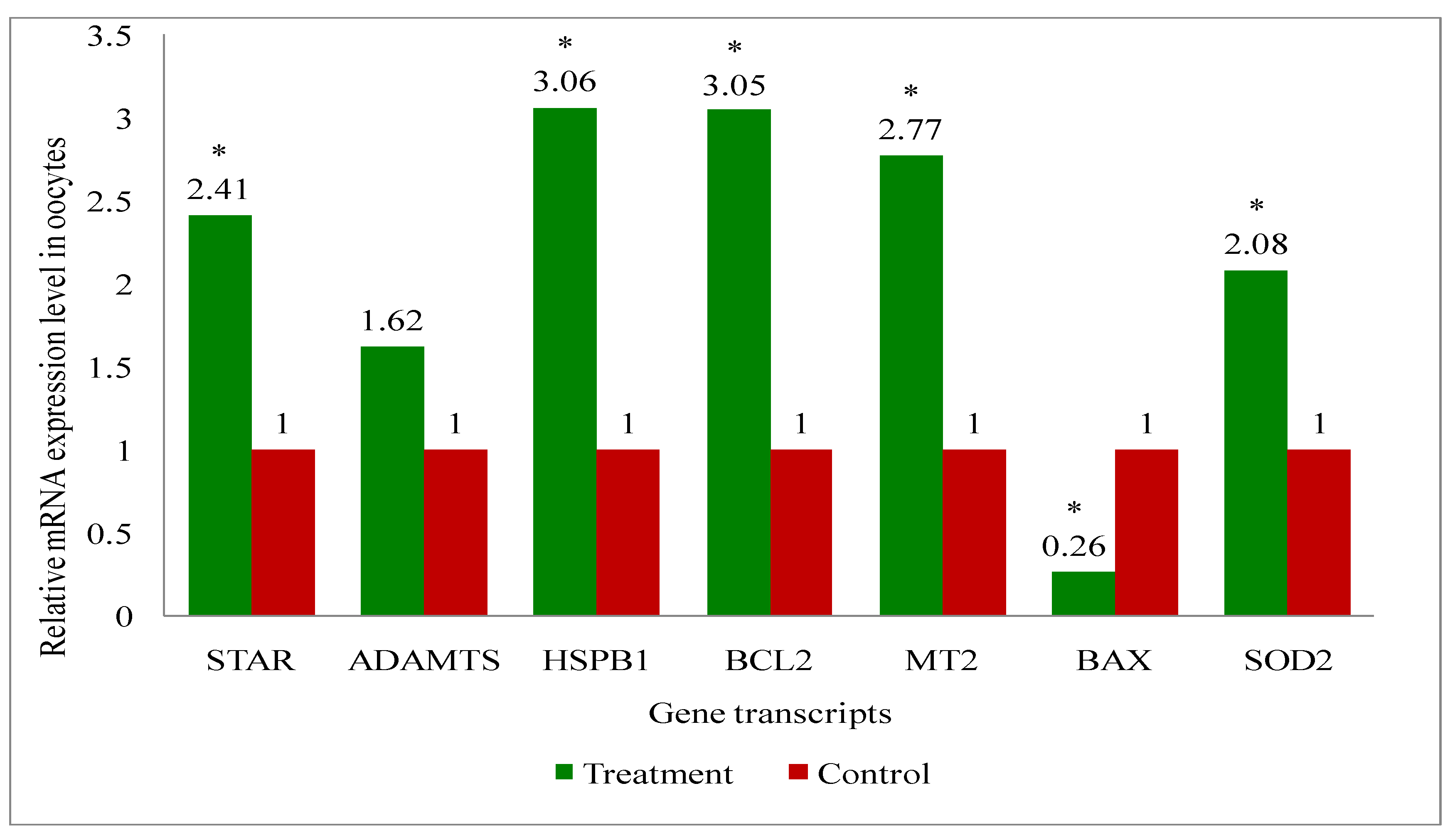

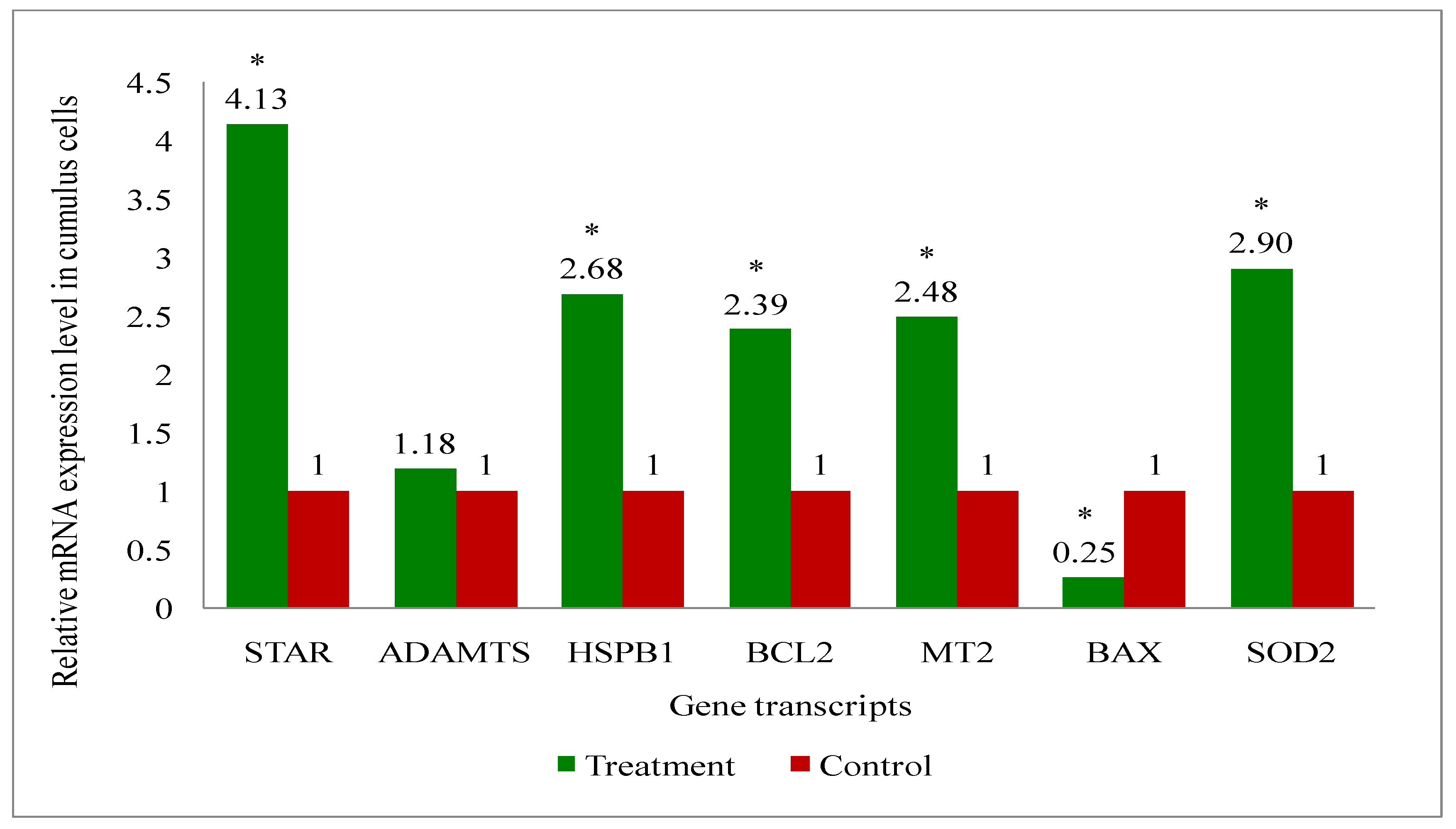

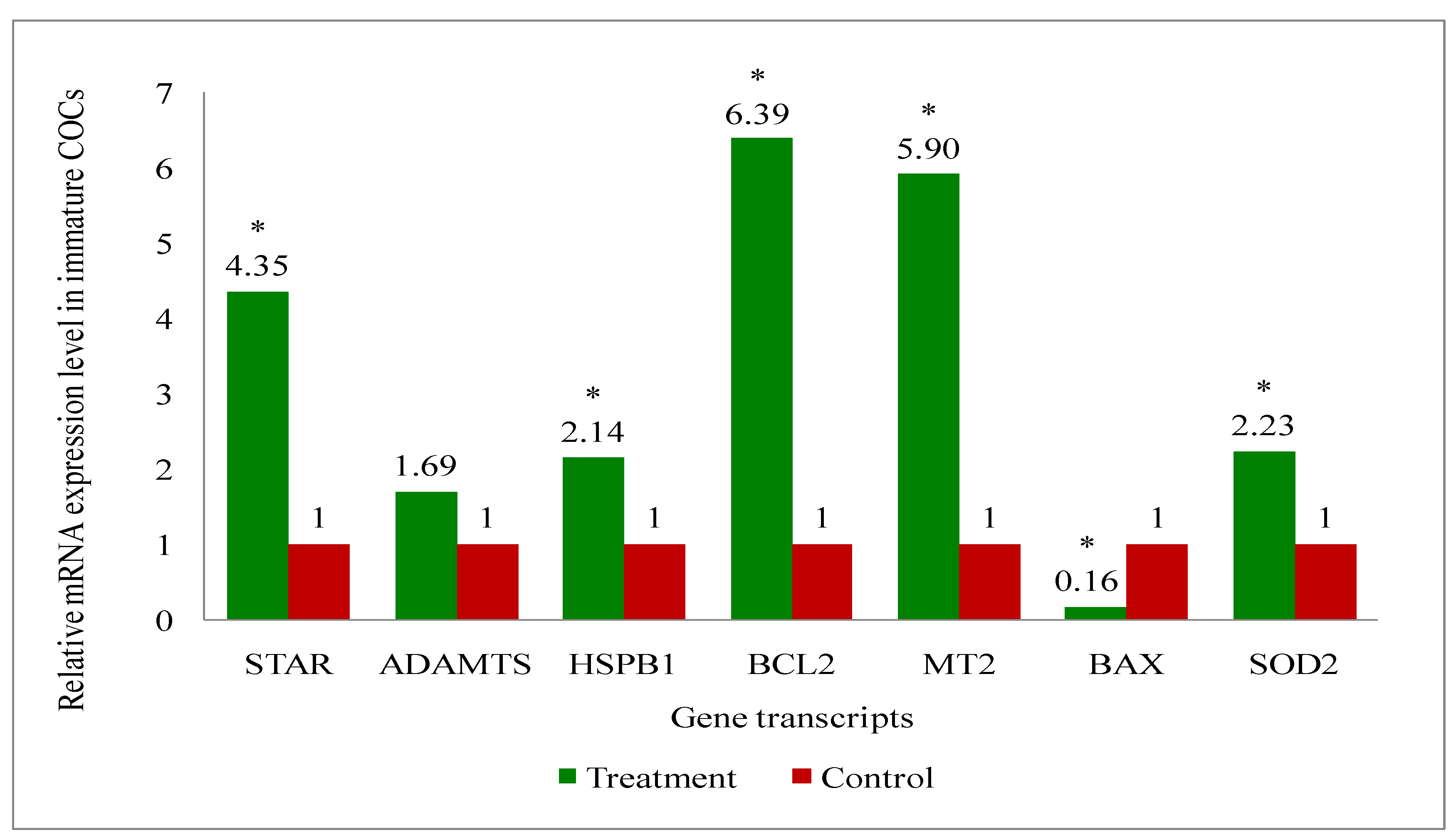

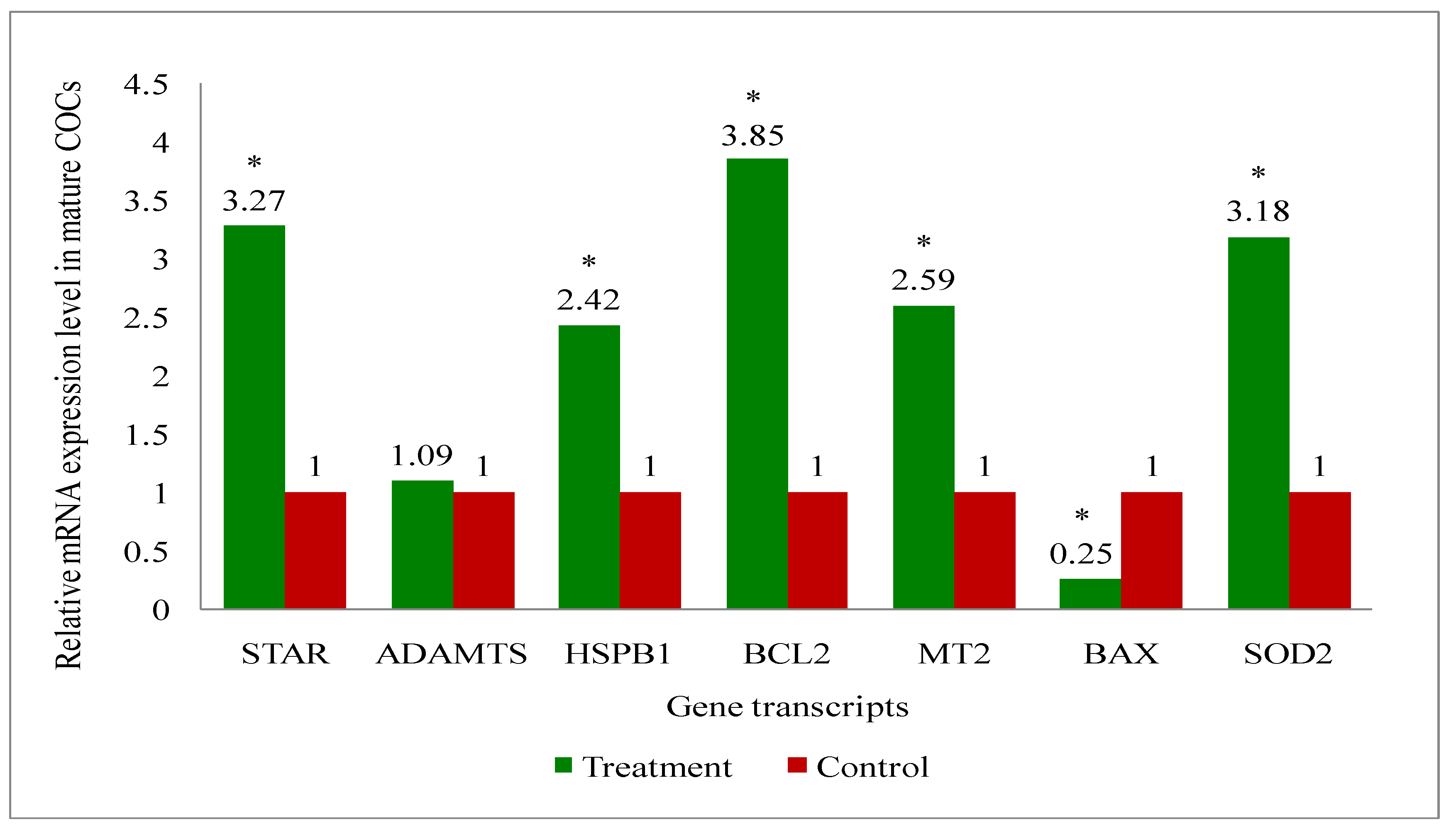

3.6. Gene Expression Analysis of the Genes Related to the Developmental Competence of Oocytes and Blastocysts in Melatonin-Treated and Non-Treated Control Group of Cows

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collier RJ, Renquist BJ and Xiao Y. A 100- Year Review: stress physiology including heat stress. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100(12):10367-10380. [CrossRef]

- Lucy MC. Stress, strain and pregnancy outcome in postpartum cows. Anim Reprod. 2019;16(3):455-464. [CrossRef]

- Khan HM, Bhakat M, Mohanty TK, Gupta AK, Raina VS and Mir MS. Peripartum reproductive disorders in buffaloes- an overview. Vet J. 2009;4(2):38.

- Sakatani M, Kobayashi S and Takahashi M. Effects of heat shock on in vitro development and intracellular oxidative state of bovine preimplantation embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 2004;67:77–82. [CrossRef]

- Orgal S, Zeron Y, Elior N, Biran D, Friedman E and Druker S. Season-induced changes in bovine sperm motility following a freeze-thaw procedure. J Reprod Dev.2011;58:212–218. [CrossRef]

- Sakatani M, Yamanaka K, Balboula AZ, Takenouchi N and Takahashi M. Heat stress during in vitro fertilization decreases fertilization success by disrupting anti-polyspermy systems of the oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev. 2015;82:36–47. [CrossRef]

- Gupta RK, Miller KP, Babus JK and Flaws JA. Methoxychlor inhibits growth and induces atresia of antral follicles through an oxidative stress pathway. Toxicol Sci. 2006;93(2):382-389. [CrossRef]

- Kala M, Shaikh MV and Nivsarkar M. Equilibrium between anti-oxidants and reactive oxygen species: A requisite for oocyte development and maturation. Reprod Med Biol. 2017;16:28-35. [CrossRef]

- Al-Gubory KH, Garrel C, Faure P and Sugino N. Roles of antioxidant enzymes in corpus luteum rescue from reactive oxygen species-induced oxidative stress. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;25(6):551-560. [CrossRef]

- Korzekwa AJ, Okuda K, Woclawek-Potocka I, Murakami S and Skarzynski DJ. Nitric oxide induces apoptosis in bovine luteal cells. J Reprod Dev. 2006;52(3):353-361. [CrossRef]

- Kawano K, Sakaguchi K, Madalitso C. et al. Effect of heat exposure on the growth and developmental competence of bovine oocytes derived from early antral follicles. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):8857. [CrossRef]

- Rispoli LA, Lawrence JL, Payton RR, Saxton AM, Schrock GE, Schrick FN, Edwards JL. Disparate consequences of heat stress exposure during meiotic maturation: embryo development after chemical activation vs fertilization of bovine oocytes. Reprod. 2011;142(6):831–843. [CrossRef]

- Roth Z. Effect of Heat Stress on Reproduction in Dairy Cows: Insights into the Cellular and Molecular Responses of the Oocyte. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2017;8(5):151-170. [CrossRef]

- Ealy AD, Drost M and Hansen PJ. Developmental changes in embryonic resistance to adverse effects of maternal heat stress in cows. J Dairy Sci. 1993;76(10):2899–2905. [CrossRef]

- Pavani K, Carvalhais I, Faheem M, Chaveiro A, Reis FV and da Silva FM. Reproductive performance of holstein dairy cows grazing in dry-summer subtropical climatic conditions: effect of heat stress and heat shock on meiotic competence and in vitro fertilization. Asian-Australas. J Anim Sci. 2015;28(3):334–342. [CrossRef]

- Sakatani M. Effects of heat stress on bovine preimplantation embryos produced in vitro. J Reprod Dev. 2017;63(4):347–352. [CrossRef]

- Verdoljak J, Pereira M, Gandara L, Acosta F, Fernandez-Lopez C and Martínez- Gonzalez J. Reproduction and mortality of cattle breeds in the subtropical climate of Argentina. Abanico Vet. 2018;8(1):28–35.

- Zubor T, Holló G, Pósa R, Nagy-Kiszlinger H, Vigh Z and Húth B. Effect of rectal temperature on efficiency of artificial insemination and embryo transfer technique in dairy cattle during hot season. Czech J Anim Sci. 2020;65:295–302. [CrossRef]

- Hansen PJ. To be or not to be–determinants of embryonic survival following heat shock. Theriogenology. 2007;68(1):S40–48. [CrossRef]

- Ramadan TA, Sharma RK, Phulia SK, Balhara AK, Ghuman SS and Singh I. Effectiveness of melatonin and controlled internal drug release device treatment on reproductive performance of buffalo heifers during out-of-breeding season under tropical conditions. Theriogenology. 2014;82:1296-1302. [CrossRef]

- Ramadan TA, Sharma RK, Phulia SK, Balhara AK, Ghuman SS and Singh I. Manipulation of reproductive performance of lactating buffaloes using melatonin and controlled internal drug release device treatment during out-of-breeding season under tropical conditions. Theriogenology. 2016;86(4):1048-1053. [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa Y, Suzuki K, Yoneda A and Watanabe T. Effects of oxygen concentration and antioxidants on the in vitro developmental ability, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and DNA fragmentation in porcine embryos. Theriogenology. 2004;62:1186–1197. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal A, Tamer MS, Mohamed AB, Jashoman B and Juan GA. Oxidative stressing assisted reproductive techniques. Steril Fertil. 2006;86: 503-512. [CrossRef]

- Miętkiewska K, Kordowitzki P and Pareek CS. Effects of heat stress on bovine oocytes and early embryonic development—an update. Cells. 2022;11(24):4073. [CrossRef]

- Luvoni GC, Keskintepe L and Brackett BG. Improvement in bovine embryo production in vitro by glutathione-containing culture media. Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;43:437-443. [CrossRef]

- Ali AA, Bilodeau JF and Sirad MA. An antioxidant requirement for bovine oocytes varies during in vitro maturation, fertilization and development. Theriogenology. 2003;59:939–949. [CrossRef]

- Reiter RJ. Pineal melatonin: cell biology of its synthesis and of its physiological interactions. Endocr Rev. 1991;12:151-180. [CrossRef]

- Tan DX, Manchester LC, Terron MP, et al. One molecule, many derivatives: A never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species? J Pineal Res. 2007;42:28-42. [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman M, Ghosal I, Das D, et al. Melatonin ameliorates H2O2-induced oxidative stress through modulation of Erk/Akt/NFkB pathway. Biol Res. 2018;51:17. [CrossRef]

- Loren P, Sanchez R, Arias M, Felmer R, Risopatrón J and Cheuquemán C. Melatonin scavenger properties against oxidative and nitrosative stress: impact on gamete handling and in vitro embryo production in humans and other mammals. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(6):1119-1136. [CrossRef]

- Tamura H, Takasaki A, Taketani T, Lee L, Tamura I, Maekawa R, Aasada H, Yamagata Yand Sugino N. Melatonin and female reproduction. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Papis K, Poleszczuk O, Wenta-Muchaiska E and Mondinski JK. Melatonin effect on bovine embryo development in vitro in relation to oxygen concentration. J Pineal Res. 2007;43:321-326. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Osorio N, Kim IJ, Wang H, Kaya A and Memilli E. Melatonin increases cleavage rate of porcine preimplantation embryos in vitro. J Pineal Res. 2007;43:283-288. [CrossRef]

- Manjunatha BM, Devaraj M, Gupta PSP, Ravindra JP and Nandi S. Effect of taurine and melatonin in the culture medium on buffalo in vitro embryo development Reprod Domest Anim. 2009;44:12-16. [CrossRef]

- He C, Wang J, Zhang Z, Yang M, Li Y, Tian X, Ma T, Tao J, Zhu K, Song et al. Mitochondria synthesize melatonin to ameliorate its function and improve mice oocyte’s quality under in vitro conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 2016a;17(6):939-955. [CrossRef]

- El-Sokary MM, El-Raey M, Mahmoud KG, Abou El-Roos ME and Sosa GM. Effect of melatonin and/or cysteamine on development and vitrification of buffalo embryos. Asian Pac J Reprod. 2017;6(4):176. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Añez JC, Lucas-Hahn A, Hadeler KG, Aldag P and Niemann H Melatonin enhances in vitro developmental competence of cumulus-oocyte complexes collected by ovum pick-up in prepubertal and adult dairy cattle. Theriogenology. 2021a;161:285-293. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Añez JC, Henning H, Lucas-Hahn A, Baulain U, Aldag P, Sieg B and Niemann H. Melatonin improves rate of monospermic fertilization and early embryo development in a bovine IVF system. PloS one. 2021b;16(9):e0256701. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Heras S, Menéndez-Blanco I, Catalá MG, Izquierdo D, Thompson JG and Paramio MT. Biphasic in vitro maturation with C-type natriuretic peptide enhances the developmental competence of juvenile-goat oocytes. PloS one. 2019;14(8):e0221663. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Heras S and Paramio MT. Impact of oxidative stress on oocyte competence for in vitro embryo production programs. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020;132:342-350. [CrossRef]

- Kang JT, Koo OJ, Kwon DK et al. Effects of melatonin on in vitro maturation of porcine oocyte and expression of melatonin receptor RNA in cumulus and granulosa cells. J Pineal Res. 2009;46:22–28. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Chai M, Tian X, Wang F, Fu Y, He C, Deng S, Lian Z, Feng J, Tan DX and Liu G. Effects of melatonin on superovulation and transgenic embryo transplantation in small-tailed han sheep (Ovis aries). Neuro Enocrinol Lett. 2013;34:294–301.

- He C, Ma T, Shi J, Zhang Z, Wang J, Zhu K, Li Y, Yang M, Song Y and Liu G. Melatonin and its receptor MT1 are involved in the downstream reaction to luteinizing hormone and participate in the regulation of luteinization in different species. J Pineal Res. 2016b;61(3):279-290. [CrossRef]

- Ratchamak R, Thananurak P, Boonkum W, Semaming Y and Chankitisakul V. The Melatonin Treatment Improves the Ovarian Responses After Superstimulation in Thai-Holstein Crossbreeds Under Heat Stress Conditions. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:888039. [CrossRef]

- Anu Rahal AR, Deepak Mehra DM, Rajesh S, Vivek Singh VS and Ahmad AH. Prophylactic efficacy of Podophyllum hexandrum in alleviation of immobilization stress-induced oxidative damage in rat. J Nat Prod. 2009:110-115.

- Ohkawa H, Ohishi N and Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95(2):351-358. [CrossRef]

- Madesh M and Balasubramanian KA. Microtiter plate assay for superoxide dismutase using MTT reduction by superoxide. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 1998;35(3):184-188.

- Beutler E. Red Cell Metabolism. A manual of Biochemical Methods 12, Academic press, London. 1971:68-70.

- International Embryo Technology Society (IETS), Chapter 9, ed. 5.

- Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J and Wittwer CT. The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments. Clin Chem. 2009;55(4):611–622. [CrossRef]

- Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-∆∆CT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402-408. [CrossRef]

- Ligiane de OL, Isabelle D, José Felipe WS, Thiago FB, Marc-André S, Maurício MF, Margot AND. Effect of vitrification using the Cryotop method on the gene expression profile of in vitro–produced bovine embryos. Theriogenology. 2016;85(4):724-733. [CrossRef]

- Rust W, Stedronsky K, Tillmann G, Morley S, Walther N and Ivell R. The role of SF-1/Ad4BP in the control of the bovine gene for the steroidogenic acute regulatory (STAR) protein. J Mol Endocrinol. 1998;21:189–200.

- Mishra B, Koshi K, Kizaki K, Ushizawa K, Takahashi T, Hosoe M, Sato T, Ito A and Hashizume K. Expression of ADAMTS1 mRNA in bovine endometrium and placenta during gestation. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2013;45(1):43-48. [CrossRef]

- Marques T, da Silva Santos E, Diesel T, Leme L, Martins C, Dode M, Alves BG, Costa FPH, de Oliveira EB, Gambarini M. Melatonin reduces apoptotic cells, SOD2 and HSPB1 and improves the in vitro production and quality of bovine blastocysts. Reprod Domest Anim. 2017;53(1), 226–236. [CrossRef]

- Silva AWB, Ribeiro RP, Menezes VG, Barberino RS, Passos JRS, Dau AMP, Costa JJN, Melo LRF, Bezerra FTG, Donato MAM, Peixoto CA, Matos MHT, Gonçalves PBD, van den Hurk R and Silva JRV. Expression of TNF-α system members in bovine ovarian follicles and the effects of TNF-α or dexamethasone on preantral follicle survival, development and ultrastructure in vitro. Anim Reprod Sci. 2017;182:56-68. [CrossRef]

- Tian X, Wang F, He C, Zhang L, Tan D, Reiter RJ and Liu G. Beneficial effects of melatonin on bovine oocytes maturation: a mechanistic approach. J Pineal Res. 2014;57(3):239–247. [CrossRef]

- Malard PF, Peixer MAS, Grazia JG, et al. Intraovarian injection of mesenchymal stem cells improves oocyte yield and in vitro embryo production in a bovine model of fertility loss. Sci Rep. 2020;10:8018. [CrossRef]

- Sananmuang T, Puthier D, Nguyen C and Chokeshaiusaha K. Novel classifier orthologs of bovine and human oocytes matured in different melatonin environments. Theriogenology. 2020;156:82–89. [CrossRef]

- Zhi giang Li, Zhang K, Zhou Y, Zhao J, Wang J and Lu W. Role of Melatonin in Bovine Reproductive Biotechnology. Mol. 2023;28:4940. [CrossRef]

- Berlinguer F, Leoni GG, Succu S, Spezzigu A, Madeddu M, Satta V, Bebbere D, Contreras-Solis I, Gonzalez-Bulnes A and Naitana S. Exogenous melatonin positively influences follicular dynamics, oocyte developmental competence and blastocyst output in a goat model. J Pineal Res. 2009;46:383-391. [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Wu H, Wang X, Haire A, Zhang X, Zhang J, Wu Y, Lian Z, Fu J, Liu G and Wusiman A. Melatonin improves the efficiency of super-ovulation and timed artificial insemination in sheep. Peer J. 2019;7:e6750. [CrossRef]

- Ishizuka B, Kuribayashi Y, Murai k, Amemiya A and Itoh MT. The effect of melatonin on in vitro fertilization and embryo development in mice. J Pineal Res. 2000;28:48-51. [CrossRef]

- Manjunatha BM, Ravindra JP, Gupta PSP, Devaraj M and Nandi S. Oocyte recovery by ovum pick up and embryo production in river buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis). Reprod Domest Anim. 2008;43:477-80. [CrossRef]

- Pang Y, Zhao S, Sun Y, Jiang X, Hao H, Du W and Zhu H. Protective effects of melatonin on the in vitro developmental competence of bovine oocytes. Anim Sci J. 2017;89(4):648–660. [CrossRef]

- Kandil OM, Rahman SMAE, Ali RS, et al. Effect of melatonin on developmental competence, mitochondrial distribution, and intensity of fresh and vitrified/thawed in vitro matured buffalo oocytes. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2024;22:39. [CrossRef]

- Reiter RJ, Tan DX and Galano A. Melatonin reduces lipid peroxidation and membrane viscosity. Front Physiol. 2014;5:377. [CrossRef]

- Shi JM, Tian XZ, Zhou GB, Wang L, Gao C, Zhu SE, Zeng SM, Tian JH and Liu GS. Melatonin exists in porcine follicular fluid and improves in vitro maturation and parthenogenetic development of porcine oocytes. J Pineal Res. 2009;47:318–323. [CrossRef]

- Tamura H, Nakamura Y, Korkmaz A, Manchester LC, Tan DX, Sugino N and Reiter RJ. Melatonin and the ovary: physiological and pathophysiological implication. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:328-343. [CrossRef]

- Kavita, Phogat JB, Pandey AK, Balhara AK, Ghuman SS and Gunwant P. Effects of melatonin supplementation prior to Ovsynch protocol on ovarian activity and conception rates in anestrous Murrah buffalo heifers during out of breeding season. Reprod Biol. 2018;18(2):161-168. [CrossRef]

- Pandey AK, Gunwant P, Soni N, Kumar S, Kumar A, Magotra A and Sahu SS. Genotype of MTNR1A gene regulates the conception rate following melatonin treatment in water buffalo. Theriogenology. 2019;128:1-7. [CrossRef]

- Reiter RJ, Manchester LC and Tan DX. Melatonin in walnuts: influence on levels of melatonin and total antioxidant capacity of blood. Nutr. 2005;21(9):920-924. [CrossRef]

- Ghuman SS, Singh J, Honparkhe M, Dadarwal D, Dhaliwal GS and Jain AK. Induction of ovulation of ovulatory size non-ovulatory follicles and initiation of ovarian cyclicity in summer anestrous buffalo heifers (Bubalus bubalis) using melatonin implants. Reprod Domest Anim. 2010;45:600-607. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Mehrotra S, Singh G, Narayanan K, Das GK, Soni YK, Singh M, Mahla AS, Srivastava N and Verma MR. Sustained delivery of exogenous melatonin influences biomarkers of oxidative stress and total antioxidant capacity in summer-stressed anestrous water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). Theriogenology. 2015;83:1402–1407. [CrossRef]

- Singh B, Ghuman SPS, Cheema RS and Bansal AK. Melatonin implant induces estrus and alleviates oxidative stress in anestrus buffalo. Indian J Anim Reprod. 2016;37(2):28–32.

- Badinga L, Thatcher WW, Diaz T, Drost M and Wolfenson D. Effect of environmental heat stress on follicular development and steroidogenesis in lactating Holstein cows. Theriogenology. 1993;39:797–810. [CrossRef]

- Wilson SJ, Kirby CJ, Koenigsfeld AT, Keisler DH and Lucy MC. Effects of controlled heat stress on ovarian function of dairy cattle. 2. Heifers. J Dairy Sci. 1998,81:2132–2138. [CrossRef]

- Badinga L, Thatcher WW, Wilcox CJ, Morris G, Entwistle K and Wolfenson D. Effect of season on follicular dynamics and plasma concentrations of oestradiol-17ß, progesterone and luteinizing hormone in lactating Holstein cows. Theriogenology. 1994;42:1263–1274. [CrossRef]

- Wolfenson D, Thatcher WW, Badinga L, Savio JD, Meidan R, Lew BJ, Braw-Tal R and Berman A. Effect of heat stress on follicular development during the estrous cycle in lactating dairy cattle. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:1106–1113. [CrossRef]

- Roth Z, Meidan R, Braw-Tal R and Wolfenson D. Immediate and delayed effects of heat stress on follicular development and its association with plasma FSH and inhibin concentration in cows. J Reprod Infertil. 2000;120(1):83–90.

- Wolfenson D, Roth Z and Meidan R. Impaired reproduction in heat-stressed cattle: basic and applied aspects. Anim Reprod Sci. 2000;60-61:535-547. [CrossRef]

- Van Voorhis BI, Dunn MS, Synder GD and Weiner CP. Nitric oxide: an autocrine regulator of human granulosa-luteal cell Steroidogenesis. Endocrinol. 1994;135:1799-1806. [CrossRef]

- Wolfenson D, Lew BJ, Thatcher WW, Graber Y and Meidan R. Seasonal and acute heat stress effects on steroid production by dominant follicles in cows. Anim Reprod Sci. 1997;47:9–19. [CrossRef]

- Roth Z, Arav A, Bor A, Zeron Y, Braw TR and Wolfenson D. Improvement of quality of oocytes collected in the autumn by enhanced removal of impaired follicles from previously heat-stressed cows. Reprod. 2001;122:737-744.

- Acuna-Castroviejo DG, Escames C, Venegas ME, Diaz-Casado E, Lima Cabello LC, Lopez S, et al. Extrapineal melatonin: Sources, regulation, and potential functions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:2997–3025. [CrossRef]

- Reiter RJ. Oxidative processes and antioxidative defense mechanisms in the aging brain. FASEB J. 1995;9:526–533. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal A, Gupta S, Sharma RK. Role of oxidative stress in female reproduction. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2005;3:28. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Xing CH, Zhang HL, Pan ZN and Sun SC. Exposure to nivalenol declines mouse oocyte quality via inducing oxidative stress-related apoptosis and DNA damage. Biol Reprod. 2021;105:1474–1483. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez C, Mayo JC, Sainz RM, Antolin I, Herrera F, Martin V, et al. Regulation of antioxidant enzymes: a significant role for melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2004;36:1- 9. [CrossRef]

- Frungieri MB, Mayerhofer A, Zitta K, Pignataro OP, Calandra RS and Gonzalez-Calvar SI. Direct action of melatonin on Syrian hamster testes: melatonin subtype 1a receptors, inhibition of androgen production, and interaction with local corticotropin-releasing hormone system. Endocrinol. 2005;146:1541–1552. [CrossRef]

- Tamura H, Jozaki M, Tanabe M, Shirafuta Y, Mihara Y, Shinagawa M, et al. Importance of melatonin in assisted reproductive technology and ovarian aging. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1135. [CrossRef]

- Zhang HM and Zhang Y. Melatonin: A well- documented antioxidant with conditional pro-oxidant actions. J Pineal Res. 2014;57:131–146. [CrossRef]

- Gao C, Han HB, Tian XZ, et al. Melatonin promotes embryonic development and reduces reactive oxygen species in vitrified mouse 2-cell embryos. J Pineal Res. 2012;52:305–311. [CrossRef]

- Guo S, Yang J, Qin J, Qazi IH, Pan B, Zang S, et al. Melatonin promotes in vitro maturation of vitrified-warmed mouse germinal vesicle oocytes, potentially by reducing oxidative stress through the Nrf2 pathway. Anim. 2021;11:2324. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz T, Celebi S and Kukner AS. The protective effects of melatonin, vitamin E and octreotide on retinal edema during ischemia-reperfusion in the guinea pig retina. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2002;12:443–449. [CrossRef]

- Sahin K, Onderci M, Gursu MF, Kucuk O and Sahin N. Effect of Melatonin supplementation on biomarkers of oxidative stress and serum vitamin and mineral concentrations in heat-stressed Japanese quail. J Appl Poult Res. 2004;13:342–348. [CrossRef]

- Allegra M, Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Gentile C, Tesoriere L and Livrea MA. The chemistry of melatonin’s interaction with reactive species. J Pineal Res. 2003;34:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Gitto E, Sainz RM, Mayo JC, Leon J, Manchester LC, Vijayalaxmi Kilic E and Kilic U. Pharmacological utility of melatonin in reducing oxidative cellular and molecular damage. Pol J Pharmacol. 2004;56:159-170.

- Ahmed WM, El-Khadrawy HH, El Hamed A, Amal R and Amer HA. Applied 315 investigations on ovarian inactivity in Buffalo heifers. Intl J Acad Res. 2010;2(1):26.

- El-Moghazy FM. Impact of parasitic infestation on ovarian activity in buffaloes-heifers with emphasis on ascariasis. World J Zool. 2011;6(2):196-203.

- He Y, Deng H, Jiang Z, Li Q, Shi M, Chen H and Han Z. Effects of melatonin on follicular atresia and granulosa cell apoptosis in the porcine. Mol Reprod Dev. 2016c;8:692–700. [CrossRef]

- Geng Y, Walls KC, Ghosh AP, Akhtar RS, Klocke BJ and Roth KA. Cytoplasmic p53 and activated Bax regulate p53-dependent, transcription-independent neural precursor cell apoptosis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58:265–275. [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Tao J, Chai M, Wu H, Wang J, Li G, He C, Xie L, Ji P, Dai Y and Yang L. Melatonin improves the quality of inferior bovine oocytes and promoted their subsequent IVF embryo development: mechanisms and results. Mol. 2017;22:2059. [CrossRef]

- Azari M, Kafi M, Asaadi A, Pakniat Z and Abouhamzeh B. Bovine oocyte developmental competence and gene expression following co-culturing with ampullary cells: an experimental study. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2021;19:371-80. [CrossRef]

- Cillo F, Brevini TAL, Antonini S, Paffoni A, Ragni G and Gandolfi F. Association between human oocyte developmental competence and expression levels of some cumulus genes. Reprod. 2007;134:645-650. [CrossRef]

- Manna PR, Dyson MT and Stocco DM. Regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene expression: present and future perspectives. Mol Hum Reprod. 2009;15:321-333. [CrossRef]

- Miller WL. Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), a novel mitochondrial cholesterol transporter. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:663–676. [CrossRef]

- Pan Z, Zhang J, Lin F, Ma X, Wang X and Liu H. Expression profiles of key candidate genes involved in steroidogenesis during follicular atresia in the pig ovary. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:10823–10832. [CrossRef]

- Zhen YH, Wang L, Riaz H, Wu JB, Yuan YF, Han L, Wang YL, Zhao Y, Dan Y and Huo LJ. Knockdown of CEBP by RNA. In porcine granulose cells resulted in S phase cell cycle arrest and decreased progesterone and estradiol synthesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;143:90–98. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Tian X, Zhang L, Tan D, Reiter RJ and Liu G. Melatonin promotes the in vitro development of pronuclear embryos and increases the efficiency of blastocyst implantation in murine. J Pineal Res. 2013;55:267–274. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Tian X, Zhang L, Gao C, He C, Fu Y and Liu G. Beneficial effects of melatonin on in vitro bovine embryonic development are mediated by melatonin receptor 1. J Pineal Res. 2014;56:333–342. [CrossRef]

- Galano A, Tan DX and Reiter RJ. On the free radical scavenging activities of melatonin’s metabolites, AFMK and AMK. J Pineal Res. 2013;54:245–257. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik HN, Kandil OM, Ahmad IM, Mansour M, El-Debaky HA, Ali KA, et al. Effect of Melatonin-loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles (CMN) on Gene Expression of In-vitro Matured Buffalo Oocyte. J Adv Vet Res. 2023;13(4):656-663.

- Al-Katanani YM, Paula-Lopes FF and Hansen PJ. Effect of season and exposure to heat stress on oocyte competence in Holstein cows. J Reprod Infertil. 2002;85:390-396. [CrossRef]

- Khan I, Lee KL, Fakruzzaman M, Song SH, Haq I, Mirza B, et al. Coagulansin-A has beneficial effects on the development of bovine embryos in vitro via HSP70 induction. Biosci Rep. 2016;36:e00310. [CrossRef]

- Lepock JR. How do cells respond to their thermal environment? Int J Hyperther. 2005;21:681–687. [CrossRef]

- Showell C and Conlon FL. Decoding development in Xenopus tropicalis. Genesis. 2007;45:418–426. [CrossRef]

- Tan DX, Manchester LC, Terron MP, et al. One molecule, many derivatives: A never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species? J Pineal Res. 2007;42:28-42. [CrossRef]

- El-Raey M, Geshi M, Somfai T, Kaneda M, Hirako M, Abdel-Ghaffar AE, Sosa GA, El-Roos ME and Nagai T. Evidence of melatonin synthesis in the cumulus oocyte complexes and its role in enhancing oocyte maturation in vitro in cattle. Mol Reprod Dev. 2011;78:250–262. [CrossRef]

- Wang SJ, Liu WJ, Wu CJ, Ma FH, Ahmad S, Liu BR, Han L, Jiang XP, Zhang SJ and Yang LG. Melatonin suppresses apoptosis and stimulates progesterone production by bovine granulosa cells via its receptors (MT1 and MT2). Theriogenology. 2012;78:1517–1526. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio RV, Conceic¸a ˜o SDB, Miranda MS, Sampaio L, de F and Ohashi OM. MT3 melatonin binding site, MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors are present in oocyte, but only MT1 is present in bovine blastocyst produced in vitro. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012;10:103. [CrossRef]

- Mishra B, Koshi K, Kizaki K, Ushizawa K, Takahashi T, Hosoe M, Sato T, Ito A and Hashizume K. Expression of ADAMTS1 mRNA in bovine endometrium and placenta during gestation. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2013;45(1):43-48. [CrossRef]

- Mittaz L, Russell DL, Wilson T, Brasted M, Tkalcevic J, Salamonsen LA, Hertzog PJ and Pritchard MA. ADAMTS-1 is essential for the development and function of the urogenital system. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1096–1105. [CrossRef]

- Shozu M, Minami N, Yokoyama H, Inoue M, Kurihara H, Matsushima K and Kuno K. ADAMTS1 is involved in normal follicular development, ovulatory process and organization of the medullary vascular network in the ovary. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;35:343–355. [CrossRef]

- Beristain AG, Zhu H and Leung PCK. Regulated Expression of ADAMTS-12 in Human Trophoblastic Cells: A Role for ADAMTS-12 in Epithelial Cell Invasion? PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4):e18473. [CrossRef]

| Oocyte grade | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Grade A | COCs having more than 3 complete and compact layers of cumulus cells covering the surface of the zona pellucida (ZP). The ooplasm was dense and have even granulation. |

| Grade B | COCs having more than or equal to 3 but incomplete and compact layers of cumulus cells covering the surface of the zona pellucida (ZP). The ooplasm was dense and have even granulation. Grade A oocytes with speckled ooplasm were downgraded to grade B. |

| Grade C | COCs having 1 or 2 compact cumulus cells layers covering the surface of the ZP and the ooplasm is dense with even granulation. Grade B oocytes with speckled ooplasm are downgraded to grade C. |

| Grade D | COCs having incomplete 1 layer of cumulus cells covering the surface of the ZP and the ooplasm is dense with uneven granulation. Grade C oocytes with speckled ooplasm are downgraded to grade D. |

| Grade E | COCs having expanded cumulus cell layers, often with an agglutinated appearance. If the ooplasm is retracted, the oocytes were considered degenerated. |

| Degenerated | COCs consist of oocytes with retracted or noticeably light and/or speckled ooplasm, fused cumulus cells or cracked and/or empty ZP. |

| Code | Quality | Characteristics |

| 1 | Excellent/ Good |

|

| 2 | Fair |

|

| 3 | Poor |

|

| 4 | Dead/ Degenerating |

|

| Gene | Primer | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | F | GGCGTGAACCACGAGAAGTATAA | [52] |

| R | CCCTCCACGATGCCAAAGT | ||

| STAR | F | CCTTTCTGCACCCTCCCTC | [53] |

| R | TAAATACCTCCAGCTGAAGGC | ||

| ADAMTS | F | CGGAAAAACCTTTAGAATGGAACA | [54] |

| R | AGGCCCGCTGCCAAA | ||

| HSPB1 | F | CTGGACGTCAACCACTTC | [55] |

| R | GGACAGAGAGGAGGAGAC | ||

| BCL2 | F | GGTAGGTGCTCGTCTGGATG | [56] |

| R | GGCCACACACGTGGTTTTAC | ||

| MT2 | F | GCTCCGTCTTCAACATCACC | [57] |

| R | CAGCACCAGCACCCAGAT | ||

| BAX | F | GCCCTTTTCTACTTTGCCAGC | [56] |

| R | GGCCGTCCCAACCACCC | ||

| SOD2 | F | TTGCTGGAAGCCATCAAACGTGAC | [58] |

| R | AATCTGTAAGCGTCCCTGCTCCTT | ||

| Group | Total Oocytes |

IVM % | IVF % | IVC % | Cleavage % | Chi- square | BL % | Chi-square | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Control (n= 15) |

121 | 74.38 (90) |

74.38 (90) |

71.90 (87) |

70.11 (61) |

1.85 | 25.29ª (22) |

4.37 | 0.04 |

|

Treatment (n= 22) |

222 | 77.48 (172) |

77.48 (172) |

73.87 (164) |

78.66 (129) |

38.41ᵇ (63) |

| Hormone | Group | N | Days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | |||

| Melatonin (pg/ml) | Control | 18 | 450.47 ± 67.07 | 339.24 ± 43.18a |

| Treatment | 25 | 378.06 ± 61.88A | 611.6 ± 75.28b,B | |

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | Control | 18 | 17.15 ± 2.33 | 20.77 ± 1.62a |

| Treatment | 25 | 16.98 ± 1.36A | 33.30 ± 2.84b,B | |

| Progesterone (ng/ml) | Control | 18 | 4.24 ± 0.47 | 3.76 ± 0.39 |

| Treatment | 25 | 3.61 ± 0.26 | 3.53 ± 0.31 | |

| Antioxidants | Group | N | Days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | |||

| SOD (U/mg Protein) | Control | 19 | 4.16 ± 0.74 | 3.96 ± 0.33a |

| Treatment | 24 | 3.95 ± 0.71A | 6.23 ± 0.32b,B | |

| GSH(µmol) | Control | 19 | 125.55 ± 23.55 | 92.66 ± 9.24a |

| Treatment | 25 | 161.24 ± 11.54A | 280.01 ± 22.87b,B | |

| MDA(µmol/gmHb) | Control | 19 | 117.43 ± 18.95 | 106.65 ± 17.65b |

| Treatment | 19 | 129.61 ± 27.17A | 58.29 ± 10.07a,B | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).