1. Introduction

The Asiatic apple leafminer,

Phyllonorycter ringoniella (Matsumura), is a significant insect pest of apple trees in Korea, Japan, and China [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This pest can produce four to six generations per year, which with their leaf mines affect photosynthesis, hasten defoliation, inhibit new bud growth, and ultimately cause premature ripening and premature fruit drop [

2,

4,

5].

Temperature is a crucial abiotic factor affecting various biological processes of insects, including development, survival, longevity, fecundity, and demographic parameters [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Understanding the relationship between temperature and these biological processes is essential for comprehending population growth and dynamics, predicting seasonal occurrences and outbreaks [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], and developing effective pest management strategies [

19,

20,

21,

22].

Mathematical models are critical tools for describing insect responses to variable environmental conditions and predicting population dynamics across different geographic zones and climates [

23,

24]. Various studies have introduced mathematical functions to depict these relationships based on an insect’s thermal characteristics at different temperatures. A population model can enhance our understanding of insect pest dynamics under a variety of environmental factors and aid in developing integrated pest management tactics through simulations [

7,

24].

In temperate regions, a population model for arthropod species typically requires three basic components: a spring emergence model, a temperature-dependent development model for immature stages, and an oviposition model [

6,

7,

25,

26,

27]. These models have been mathematically described and applied to various temperature-dependent and stage-structured models of insects and mites. They can also be used to calculate developmental thresholds, optimal temperatures, thermal constants, survival rates, longevity, and fecundity, aiding in predicting geographic distribution, phenology, and providing precise forecasting systems [

9,

11].

Understanding the population dynamics of P. ringoniella in apple orchards is vital for developing effective management strategies. The objective of this study is to develop and validate a population model for P. ringoniella using field data. This information will help us comprehend the population dynamics of this pest and formulate effective management strategies for apple orchards

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Construction

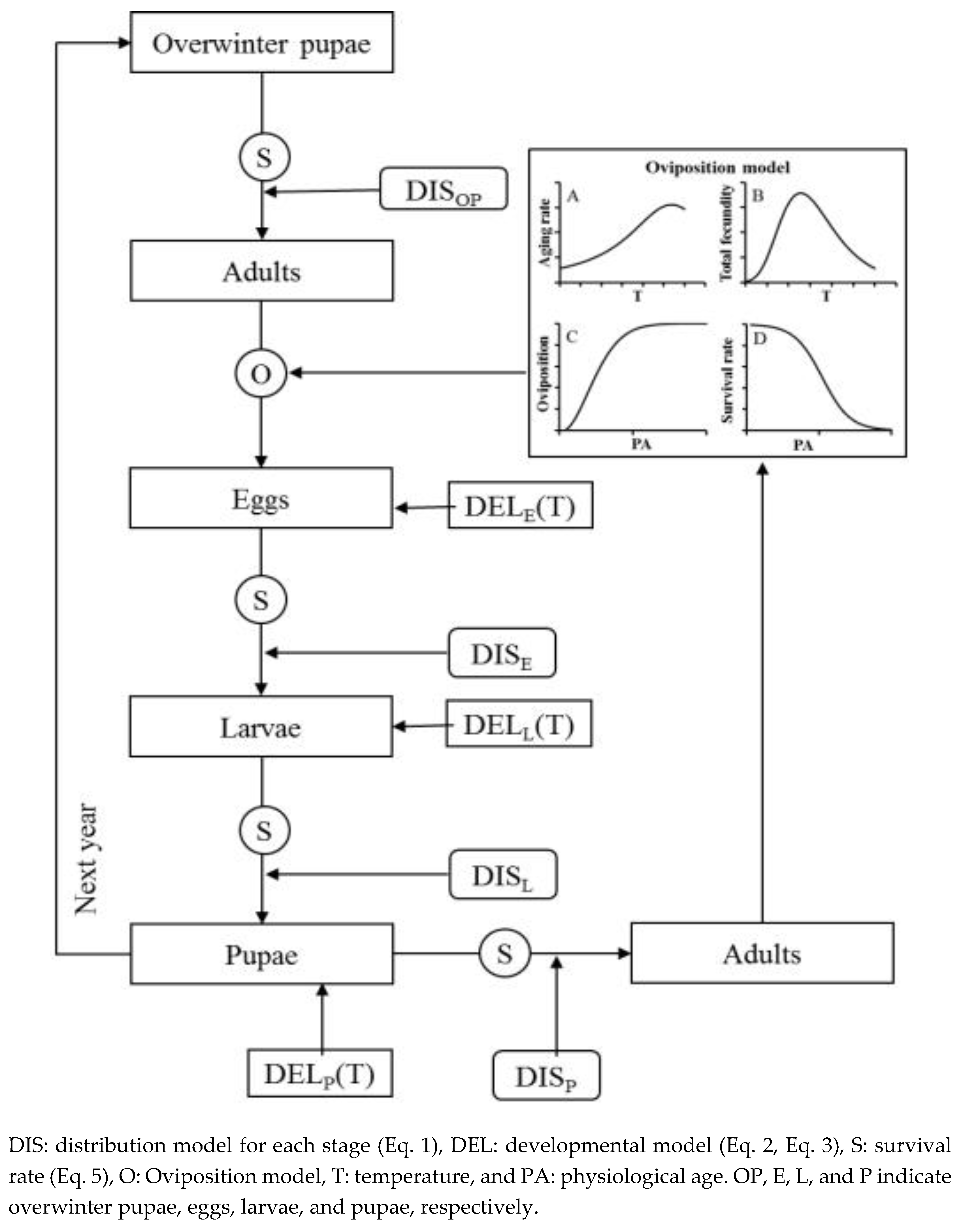

The

P. ringoniella population model was constructed to include five developmental stages: overwinter pupa, egg, larva, pupa, and adult (

Figure 1). Each stage was divided into separate cohorts of individuals, which entered the stage on a given day and were treated as different age groups within the stage [

24,

28]. However, the overwintering pupae with which the model started, consisted of a single cohort, with the assumption that individuals of this cohort were physiologically identical [

25].

The population model was consisted of three component models (

Figure 1): the spring emergence model [

29], the oviposition model [

30], and the stage transition model [

31]. The spring emergence model predicted adult emergence from overwintering pupae using the two-parameter Weibull function based on accumulated degree days. The adult oviposition model consisted of four temperature-dependent components: the developmental (aging) rate model, total fecundity model, age-specific oviposition rate model, and age-specific survival rate model. The stage transition model for each immature stage included the temperature-dependent developmental rate model and the developmental distribution model.

At any given time, each cohort was defined by two variables [

23]: aij(t), the physiological age of cohort j within stage i at time t; and Nij(t, a), the number of individuals in cohort j of physiological age a at time t. The output of the model is Ni(t), the total number in stage i at time t, calculated by summing over the cohorts.

Temperature was the only meteorological factor included in the model; other variables, such as relative humidity, were not considered. The model starts with the overwintering pupal stage with an arbitrarily defined number of individuals. Model computations used a daily time-step, assuming all mortality occurred at the transition to the next stage. It was also assumed that there was no emigration or immigration of

P. ringoniella adults. The population model was simulated using PopModel 1.5 [

32].

2.2. Sub-Models and Their Process Functions

The process functions and their parameters (

Table 1,

Table 2) were obtained from previous studies, the spring emergence model from Geng and Jung (2018) [

29], the adult oviposition model from Geng and Jung (2017) [

30], and the stage transition model from Geng and Jung (2018) [

31].

Spring Emergence Model: daily spring adult emergence was estimated using Weibull distribution model (Eq. 1). This model uses cumulative degree-days with a base temperature of 7.06℃ from January 1 as an independent variable [

29].

Adult Oviposition Model: this model included four component functions, the adult aging rate function (Eq. 4), temperature-dependent total fecundity function (Eq. 5), age-specific oviposition rate function (Eq. 6), and age-specific survival rate function (Eq. 7). Since total egg production by female adults could be influenced by temperatures experienced by them earlier, the average temperature during the 5 days prior to oviposition was taken as input variable in the total fecundity model. Daily egg production was estimated by the PopModel 1.5 [

32] according to the computational process of Kim and Lee (2003) [

26]. The sex ratio (female proportion) was assumed to be 0.5 [

33].

Stage Transition models: These models simulate the proportion of individuals transitioning from one stage to the next, comprising a temperature-dependent development rate function and a cumulative distribution function.

Immature Survival Model: the survival rates of eggs, larvae, and pupae at different constant temperatures (13.3-32.2℃) were examined in the laboratory. The survival rates were simulated using an extreme value equation (Eq. 5), with parameter values presented in

Table 2.

External Mortality Model: Parasitism is a major biological external mortality factor for the apple leafminer [

5], while insecticides are the major non-biological external mortality factor [

34]. Given the mining behavior of the larvae, an insecticide-driven mortality averaging 86.1%, was considered only for the egg stage, which is directly exposed to the pesticide spray [

34]. The insecticide was assumed to be effective against eggs oviposited five days before and five days after the spraying date [

24,

34]. Parasitism rates of larvae and pupae were assumed to be 29.5% in a conventional orchard [

5] and 54.9% in a pesticide-free orchard (unpublished data).

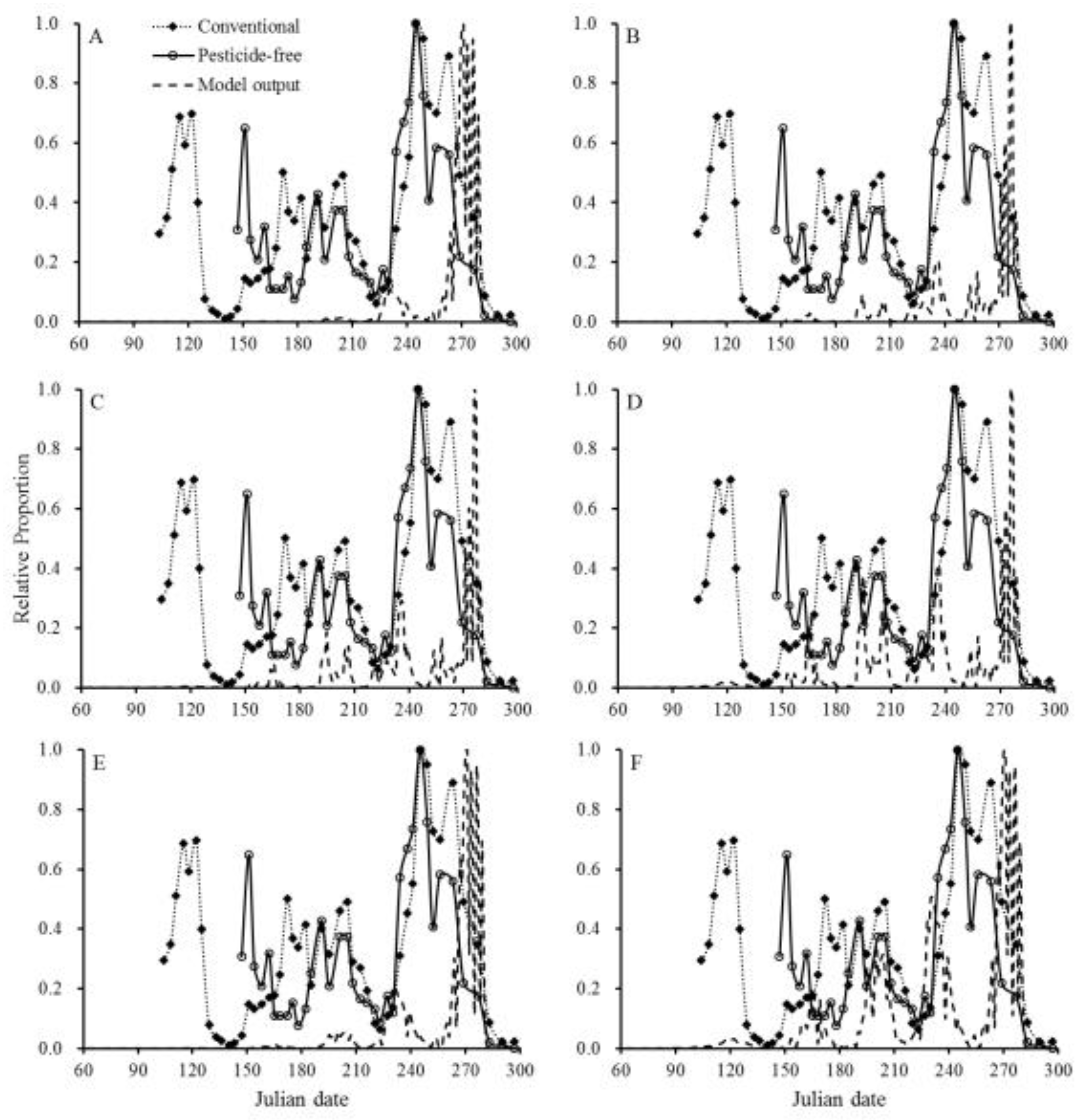

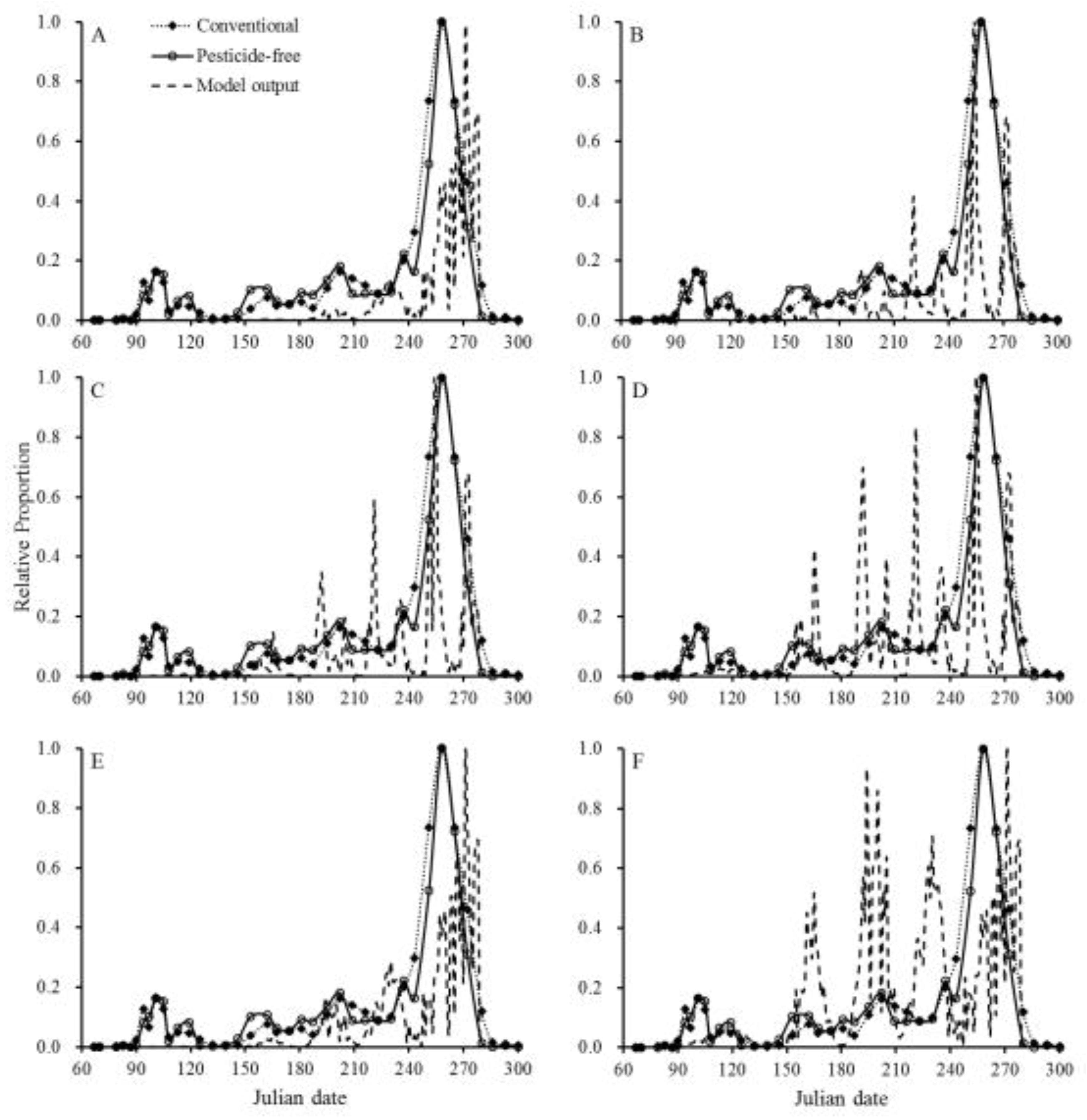

2.3. Simulations under Six Scenarios

The population model was simulated under six scenarios:

Scenario A: original run, was without insecticide effects or natural enemies. The population increased naturally.

Scenario B: based on scenario A, with the pesticide effect added to the egg stage. Pesticide was sprayed ten times, starting on Julian date 115, at 15-day intervals.

Scenario C: based on scenario B, with the natural enemy effect added to the larval stage. A parasitoid rate of 29.5% was applied.

Scenario D: based on scenario C, with the natural enemy effect added to the pupal stage. A parasitoid rate of 29.5% was applied.

Scenario E: based on scenario A, with the natural enemy effect added to the larval and pupal stages. A parasitoid rate of 29.5% was applied.

Scenario F: same as scenario E, but with a parasitoid rate 54.9 %.

These scenarios were simulated using PopModel 1.5, with meteorological data from 2015 and 2016 in Andong, South Korea.

2.4. Field Population DATA collection

To validate the model against field data, the flight occurrences of

P. ringoniella adults were monitored in 28 conventional and one pesticide-free apple orchard in Andong, from April 10 to October 24, 2015, and from March 1 to October 26, 2016. Most apple orchards were cultivated by mix varieties but dominated by ‘Fuji’ and ‘Hongro’. Commercial pheromone traps (GreenAgro Tech, Kyeongsan, Korea) baited with synthetic sex pheromone lures containing a 6:4 ratio of E4,Z10-14:Ac and Z10-14:Ac [

35], were used for monitoring. One trap was hung 1.5 meters above ground in each orchard and checked weekly or twice a week. The lures were changed every two months, and the sticky inserts were changed weekly.

2.5. Meteorological Data

The meteorological data of daily average, maximum, and minimum temperatures, were obtained from Andong meteorological station (

http://www.kma.go.kr). The biofix for degree day accumulation was set to January 1 for simplicity [

36].

2.6. Sensitivity Analysis

Temperature data of 2015 were used for all simulations during the sensitivity analyses. Simulations were carried out under Scenario F, starting from the spring emergence model with 100 overwintered pupae as the initial input.

The sensitivity of parameter changes was examined by altering certain parameter values by 10% [

23,

24]. Several model outputs were evaluated: the total number of eggs, larvae, pupae, and adults, and the peak date (Julian date) of each generation. The parameters of the developmental models were excluded from the sensitivity analyses due to invalid equation solutions with parameter changes. The average effect and non-linearity index were used for sensitivity analysis [

23,

24]:

Where F(p) is the output at parameter value p, and p0 is the parameter value in original run.

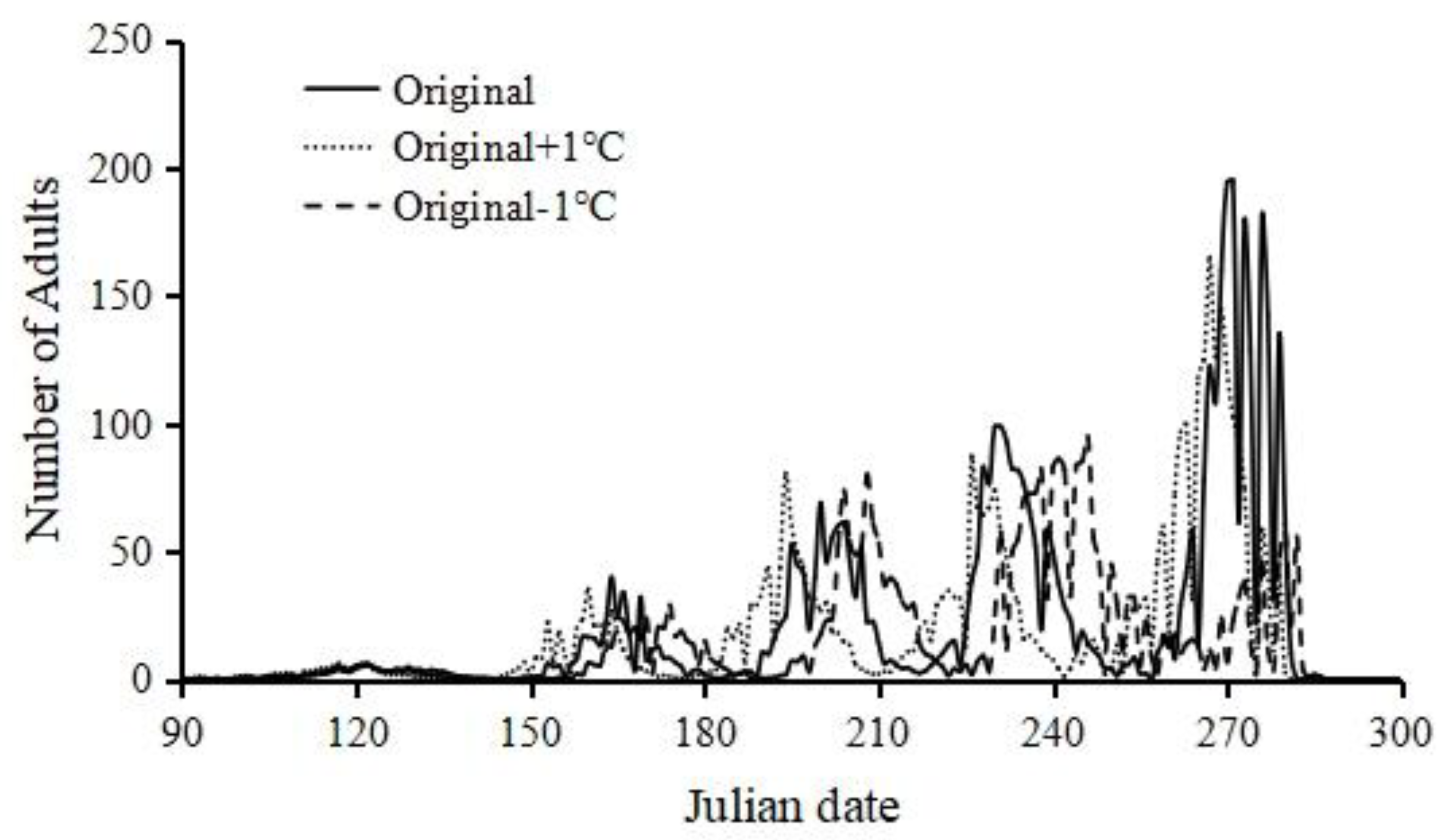

The sensitivity of temperature change was conducted by running the model with temperatures in 2015 decreased or increased 1℃.

3. Results

3.1. Simulation and Validation

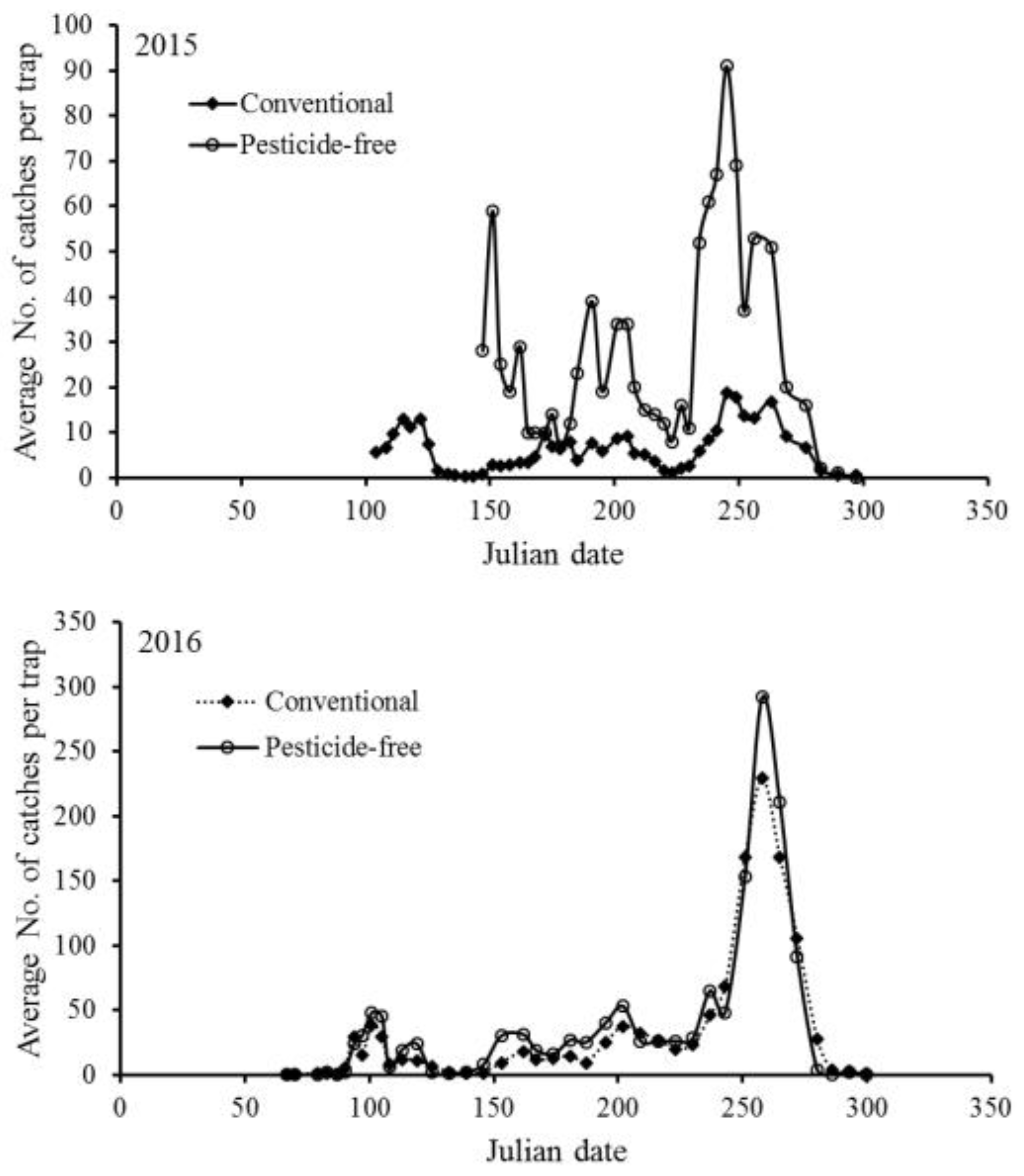

The seasonal population dynamics of

P. ringoniella in the conventional and pesticide-free orchards in 2015 and 2016 are shown in

Figure 2.

P. ringoniella exhibited five annual occurrences with overlapping 4th and 5th generations. The population model successfully simulated the typical pattern of

P. ringoniella, accurately predicting the number of generations and the peak time of each generation (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Table 3). However, the model did not accurately predict the population size for each generation. To test the effects of pesticides and natural enemies on population dynamics, the population model was simulated under six scenarios (

Figure 3,

Figure 4). The pesticide influenced both population size and peak time (

Table 3), whereas natural enemies only decreased the population size without affecting the peak time of each generation.

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis

The average effect is proportional to a numerical approximation of the partial first derivative of the output with respect to the parameter, and the non-linearity index is proportional to an approximation of the partial second derivative [

23,

24]. In most cases, the absolute value of the average effect is larger than the non-linearity index, indicating a stronger linear relationship between model outputs and the parameters (Table 4). Negative average effect values imply that model outputs decrease as parameter values increase. Negative non-linearity values indicate a convex curve relationship between the outputs and parameters. If both values are negative, the model outputs decrease along a convex curve with increasing parameter values [

24]. The most influential parameter was found in the total fecundity model. The total number of eggs, larvae, pupae, and adults increased as the parameters ω and/or ε increased. Both average effects and non-linearity were observed in our sensitivity results, suggesting that parameter changes can influence the population model in a complex manner.

Increased temperature led to earlier adult peak dates, especially for the summer generations, while decreased temperature delayed the adult peak time (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The population model provided a fundamental structure for understanding the population dynamics of P. ringoniella in apple orchards. While the model successfully simulated the typical occurrence patterns of P. ringoniella, it showed some discrepancies when compared with actual field observations. Specifically, the peak times of each generation, especially the 4th and 5th generations, differed between the actual data and the simulated results. Additionally, the model tended to overestimate the population sizes of the summer generations, particularly when pesticide and natural enemy effects were not included.

The most influential factors affecting peak times were the parameters of the developmental models. When these models are based on lower and upper threshold temperatures, insect development can be underestimated or overestimated at extreme temperatures [

24]. Previous insect population dynamic models have demonstrated that considering micro-environmental weather conditions can significantly improve model accuracy regarding population peak times and sizes [

37,

38]. Internal temperatures of leaves and fruits can differ from ambient air temperatures by as much as 13-14°C [

39,

40]. Overestimating these internal leaf temperatures results in a leftward shift in the larval distribution model, leading to earlier peak times for the 3rd generation in this study.

The population occurrence patterns of

P. ringoniella were estimated under six scenarios. However, the simulated outputs were not sufficient to fully explain actual field observations, because the model incorporated pesticide and natural enemy effects in a simplified manner. To improve the model, factors such as pesticide residue effects, pupae diapause, and adult survival should be included [

24].

The present population model demonstrated the typical patterns of

P. ringoniella population dynamics in apple orchards. Similar temperature-dependent models for other insect species have been reported in previous studies to predict developmental rates [

20,

21], spring emergences [

14,

16,

17], and population dynamics [

15,

18]. This model enhances our understanding of the role of a warming climate in the population dynamics and ecology of this insect pest, providing useful guidance for managing this pest species as suggested by Shaffer and Gold (1985) [

23].

For a population model to be used as a practical management tool, it must accurately reflect actual observations and predict the timing and number of control procedures [

13,

23,

24]. While the current model can predict adult peak times effectively, further validation is needed to test the model's efficacy in controlling

P. ringoniella in apple orchards. Consequently, we expect the model to be useful in evaluating new management practices and in estimating population dynamics and abundance changes of

P. ringoniella in response to climate changes, such as global warming.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.GENG and C.J.; methodology, C.J.; software, L.Q. and S.Guo; validation, Z.Z. and H.T.; formal analysis, S.GENG and L. CHEN; investigation, S.GENG and H.H.; data curation, L.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, S.GENG and H.H.; writing—review and editing, S.GENG and C.J.; visualization, S.Guo; supervision, C.J.; project administration, S.GENG and C.J.; funding acquisition, S.GENG and C.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly funded by International science and technology cooperation project of Henan Province (242102520042), Key Scientific Research Projects of Universities in Henan Province (24B210012), Henan Province science and technology research project (242102110178), Xinyang Academy of Ecological Research Open Foundation(2023XYQN08, 2023XYMS11), Special funds for Henan Provinces Scientific and Technological Development Guided by the Central Government (Z20221341063), and Young Scientific Research Foundation of Xinyang Agriculture and Forestry University (QN2021028). CJ was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2018R1A6A1A03024862).

Acknowledgments

We thanked Dr. Zhang and Benno Victor Meyer-Rochow for critical reading and English correction of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lee, S.W.; Kim, I.S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, M.H.; Hyun, J.S. Seasonal occurrences of the apple leaf miner, Phyllonorycter ringoniella (Matsumura) and its parasites and damaging leaf position. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 1985, 24, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Sugie, H.; Tamaki, Y.; Kawasaki, K.; Wakou, M.; Oku, T.; Hirano, C.; Horiike, M. Sex pheromone of the apple leafminer moth, Phyllonorycter ringoniella (Matsumura) (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae): Activity of geometrical isomers of tetradecadienyl acetates. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1986, 21, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.P.; Vijaykumar, B.V.D.; Harshavardhan, S.J.; Jung, H.; Xie, Y.; Yoon, Y.; Jang, K.; Shin, D. A Concise Li/liq. NH3 Mediated Synthesis of (4E, 10Z)-Tetradeca-4, 10-dienyl Acetate: The major sex pheromone of apple leafminer moth, Phyllonorycter ringoniella. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2014, 35, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Hou, H.; Jung, C. Effect of Diets and Low Temperature Storage on Adult Performance and Immature Development of Phyllonorycter ringoniella in Laboratory. Insects 2019, 10, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.W.; Kim, S.H.; Yiem, M.S.; Lee, M.H.; Hyun, J.S. Seasonal changes of leaf damage and parasitism of the apple leaf miner, Phyllonorycter ringoniella (Matsumura) in Relation to the Management and Varieties in Apple Orchards. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 1985, 24, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.J.; Cho, J.R.; Kim, J.H.; Seo, B.Y. Thermal effects on the population parameters and growth of Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris)(Hemiptera: Aphididae). Insects 2020, 11, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.S.; Samayoa, A.C.; Hwang, S.Y.; Huang, Y.B.; Ahn, J.J. Thermal effect on the fecundity and longevity of Bactrocera dorsalis adults and their improved oviposition model. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.B.; Gao, Y.; Cui, J.; Shi, S.S. Effects of temperature on the development and fecundity of Atractomorpha sinensis (Orthoptera: Pyrgomorphidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2020, 113, 2530–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, N.A.; Ganjisaffar, F.; Perring, T.M. Effect of temperature on the survival and developmental rate of immature Ooencyrtus mirus (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2020, 113, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroyoshi, S.; Mitsunaga, T.; Reddy, G.V. Effects of temperature, age and stage on testis development in diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.)(Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Physiol. Entomol. 2021, 46, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Li, G.; Zhou, C.; Yin, S. Influence of temperature on the development and reproduction of Cinara cedri (Hemiptera: Aphidoidea: Lachninae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 2021, 111, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.C.; Teulon, D.A.; Chapman, R.B.; Butler, R.C.; Drayton, G.M.; Phillipsen, H. Effects of temperature on survival, oviposition, and development rate of ‘greenhouse’and ‘lupin’strains of western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2021, 169, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongmo, M.A.; Fiaboe, K.K.M.; Kekeunou, S.; Nanga, S.N.; Kuate, A.F.; Tonnang, H.E.; Gnanvossou, D.; Hanna, R. Temperature-based phenology model to predict the development, survival, and reproduction of the oriental fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 97, 102877. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, J.; Stevens, M.M. A degree-day model for predicting adult emergence of the citrus gall wasp, Bruchophagus fellis (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae), in southern Australia. Crop Prot. 2021, 143, 105553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neta, A.; Gafni, R.; Elias, H.; Bar-Shmuel, N.; Shaltiel-Harpaz, L.; Morin, E.; Morin, S. Decision support for pest management: Using field data for optimizing temperature-dependent population dynamics models. Ecol. Modell. 2021, 440, 109402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemer, N.; Schieler, M.; Racca, P.; Saucke, H. Modelling of post-diapause development and spring emergence of Cydia nigricana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 2021, 111, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyers, E.C.; Urban, J.M.; Dechaine, A.C.; Pfeiffer, D.G.; Crawford, S.R.; Calvin, D.D. Spatio-temporal model for predicting spring hatch of the spotted lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae). Environ. Entomol. 2021, 50, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañedo, V.; Dávila, W.; Carhuapoma, P.; Kroschel, J.; Kreuze, J. A temperature-dependent phenology model for Apanteles subandinus Blanchard, parasitoid of Phthorimaea operculella Zeller and Symmetrischema tangolias (Gyen). J. Appl. Entomol. 2022, 146, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamarra, H.; Sporleder, M.; Carhuapoma, P.; Kroschel, J.; Kreuze, J. A temperature-dependent phenology model for the greenhouse whitefly Trialeurodes vaporariorum (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Virus Res. 2020, 289, 198107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nika, E.P.; Kavallieratos, N.G.; Papanikolaou, N.E. Linear and non-linear models to explain influence of temperature on life history traits of Oryzaephilus surinamensis (L.). Entomol. Gen. 2021, 41, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régnier, B.; Legrand, J.; Rebaudo, F. Modeling temperature-dependent development rate in insects and implications of experimental design. Environ. Entomol. 2022, 51, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Hu, G.; Kang, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Development of Necrobia ruficollis (Fabricius)(Coleoptera: Cleridae) under Different Constant Temperatures. Insects 2022, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, P.L.; Gold, H.J. A simulation model of population dynamics of the codling moth, Cydia pomonella. Ecol. Modell. 1985, 30, 247–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, J.H. A population model for the peach fruit moth, Carposina sasakii Matsumura (Lepidoptera: Carposinidae), in a Korean orchard system. Ecol. Modell. 2010, 221, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, J.H.; Yiem, M.S. Spring emergence pattern of Carposina sasakii (Lepidoptera: Carposinidae) in apple orchards in Korea and its forecasting models based on degree-days. Environ. Entomol. 2000, 29, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, J.H. Oviposition model of Carposina sasakii (Lepidoptera: Carposinidae). Ecol. Modell. 2003, 162, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.S.; Kim, D.S. Effect of Temperature on the Fecundity and Longevity of Ascotis selenaria (Lepidoptera: Geometridae): Developing an Oviposition Model. J. Econ. Entomol. 2016, 109, 1267–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, G.L.; Feldman, R.M. Mathematical foundations of population dynamics. The Texas Engineering experiment station monograph series, No. 3, Texas Engineering Experiment Station, Texas A and M University, TX. 1987.

- Geng, S.; Jung, C. Temperature-dependent development of overwintering pupae of Phyllonorycter ringoniella and its spring emergence model. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2018, 21, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Jung, C. Effect of temperature on longevity and fecundity of Phyllonorycter ringoniella (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae) and its oviposition model. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2017, 20, 1294–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Jung, C. Temperature-Dependent Development of Immature Phyllonorycter ringoniella (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae) and Its Stage Transition Models. J. Econ. Entomol. 2018, 111, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.S.; Kim, D.S. PopModel 1.5. Korean patent C-2017-003991, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, S.; Jung, C. Effect of temperature on the demographic parameters of Asiatic apple leafminer, Phyllonorycter ringoniella Matsumura (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae). J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2017, 20, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.H.; Li, A.H.; Sun, J.X.; Gu, H.C.; Yin, C.S. On the Biology and chemical control of Asiatic apple leafminer. J. Plant Prot. 2000, 27, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Boo, K.S.; Jung, C.H. Field tests of synthetic sex pheromone of the apple leafminer moth, Phyllonorycter ringoniella. J. Chem. Ecol. 1998, 24, 1939–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.J.; Yang, C.Y.; Jung, C. Model of Grapholita molesta spring emergence in pear orchards based on statistical information criteria. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2012, 15, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toole, J.L.; Norman, J.M.; Holtzer, T.O.; Perring, T.M. Simulating Banks grass mite (Acari: Tetranychidae) population dynamics as a subsystem of a crop canopy-microenvironment model. Environ. Entomol. 1984, 13, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, H.J.; Kendall, W.L.; Shaffer, P.L. Nonlinearity and the effects of microclimatic variability on a codling moth population (Cydia pomonella): A sensitivity simulation. Ecol. Modell. 1987, 37, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsberg, J.J.; Powell, D.B.B.; Butler, D.R. Microclimate in an apple orchard. J. Appl. Ecol. 1973, 10, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, M.R. Radiant heating of apples. J. Appl. Ecol. 1974, 11, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).