Submitted:

09 August 2024

Posted:

12 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Criticisms of Endometrial Thickness Studies:

- Study Variability: Differences in stimulation protocols (Lv et al., 2020), the number of embryos transferred (Gallos et al., 2018; Kasius et al., 2014), and increments in ET measurements (Liu et al., 2018; Shakerian et al., 2021) contribute to inconsistent results.

- Sample Size Issues: Early studies had small sample sizes (Fleischer et al., 1986; Gonen et al., 1989), while recent larger studies face issues like missing data and confounding factors (Liu et al., 2018; Mahutte et al., 2022).

- Ultrasound Variability: Advances in ultrasound technology and high inter- and intraobserver variability impact the reliability of ET measurements (De Geyter et al., 2000).

- Measurement Timing: Variations in ET measurement timings in IVF and IUI cycles affect the comparability of results.

1.2. Key Findings:

- Endometrial and Myometrial Function: Studies show higher implantation rates in gestational carriers compared to intentional mothers during the first embryo transfer, suggesting a functional syncytium between the endometrium and myometrium that is involved in successful embryo implantation (US Registry Data on Gestational Carriers, 2021).

- Controversies in Endometrial Preparation: The debate persists on the impact of endometrial preparation on embryo implantation. Tailored treatments should not solely rely on sequential euploid embryo transfer due to age and ovarian reserve constraints but also consider extra-embryonic causes of implantation failure.

2. Relevant Sections

2.1. Endometrial Thickness:

- Ideal thickness is between 7-14 mm for optimal implantation rates, measured via transvaginal ultrasound. Thickness below 7 mm is associated with lower implantation rates and higher chances of miscarriage (Liu KE et al., 2018; Weiss NS et al., 2017; Kasius A et al., 2014). Thickness greater than 14 mm may negatively impact implantation success (Mahutte N et al., 2022; Liao S et al., 2021; Yuan X et al., 2016; Chen XJ et al., 2012; Josse J et al., 2020; Kolibianakis EM et al., 2004; Noyes N et al., 1995; Sundstrom P et al., 1998; Check JH et al., 2011; El-Toukhy T et al., 2008; Vaegter KK et al., 2017; Zhao J et al., 2014; Kumbak B et al., 2009; Kovacs P et al., 2003; Al-Ghamdi A et al., 2008; Aydin T et al., 2013; Wu Y et al., 2014; Bu Z et al., 2015).

- The issue remains debated with differing evaluations among authors (Eva R et al., 2018; Mathyk B et al., 2023; ESHRE WORKING GROUP ON RIF D Cimadomo et al., 2023).

2.2. Triple-Line Pattern Diagnosed by Ultrasound:

2.3. Hormonal Environment:

2.4. Future Perspectives in Endometrial Features Assessment:

2.5. Endometrial Dating:

2.6. Immunohistochemical Evaluation:

3. Strategies for Low Endometrial Thickness

3.1. Hormonal Supplementation

- Estradiol: Oral, transdermal, or injectable forms can increase endometrial thickness (Lutjen P et al., 1984; Navot D et al., 1986; Rosenwaks Z et al., 1987). Higher doses or extended administration may be required for patients with thin linings (Simon C et al., 1995; Paulson RJ et al., 1990; Zhang T et al., 2018; Alur-Gupta S et al., 2018; Yarali H et al., 2016; Groenewoud ER et al., 2016; Wright KP et al., 2006; Tourgeman DE et al., 2001; Liao X et al., 2014; Sekhon L et al., 2019). Adequate thickness is critical for improving pregnancy rates (Racca A et al., 2023).

- Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG): Low-dose hCG can stimulate endometrial growth and improve thickness (Eftekhar M et al., 2014).

3.2. Potential Reasons for Inadequate Endometrial Growth

3.3. Management Strategies for Inadequate Endometrial Growth

- Hormonal Adjustments: Increasing dose or changing the route of estrogen administration, ensuring adequate progesterone levels.

-

Improving Blood Flow:

- ◦

- Aspirin or Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin (LMWH): Improve endometrial blood flow.

- ◦

- Pentoxifylline and Vitamin E: Enhance thickness by improving blood flow.

-

Addressing Chronic Endometritis:

- ◦

- Antibiotic Treatment: Treating infections to restore normal growth.

-

Surgical Interventions:

- ◦

- Hysteroscopic Surgery: Remove adhesions or polyps interfering with development.

-

Lifestyle Modifications:

- ◦

- Healthy Diet and Exercise: Improve overall health, though evidence for restorative functions is limited.

- ◦

- Stress Reduction: Techniques like relaxation, counseling, or yoga (Domar AD et al., 2000).

- ◦

- Smoking Cessation: Improve reproductive health and receptivity.

-

Use of Growth Factors:

- ◦

- Granulocyte-Colony Stimulating Factor (G-CSF): Some studies suggest improvement in thickness, though debated for biases.

3.4. Adjuvant Therapies

- Low-Dose Aspirin: May improve blood flow, enhancing thickness and receptivity (Rubinstein M et al., 1999).

- Pentoxifylline and Vitamin E: Believed to improve thickness by enhancing blood flow and reducing oxidative stress (Lédée-Bataille N et al., 2002).

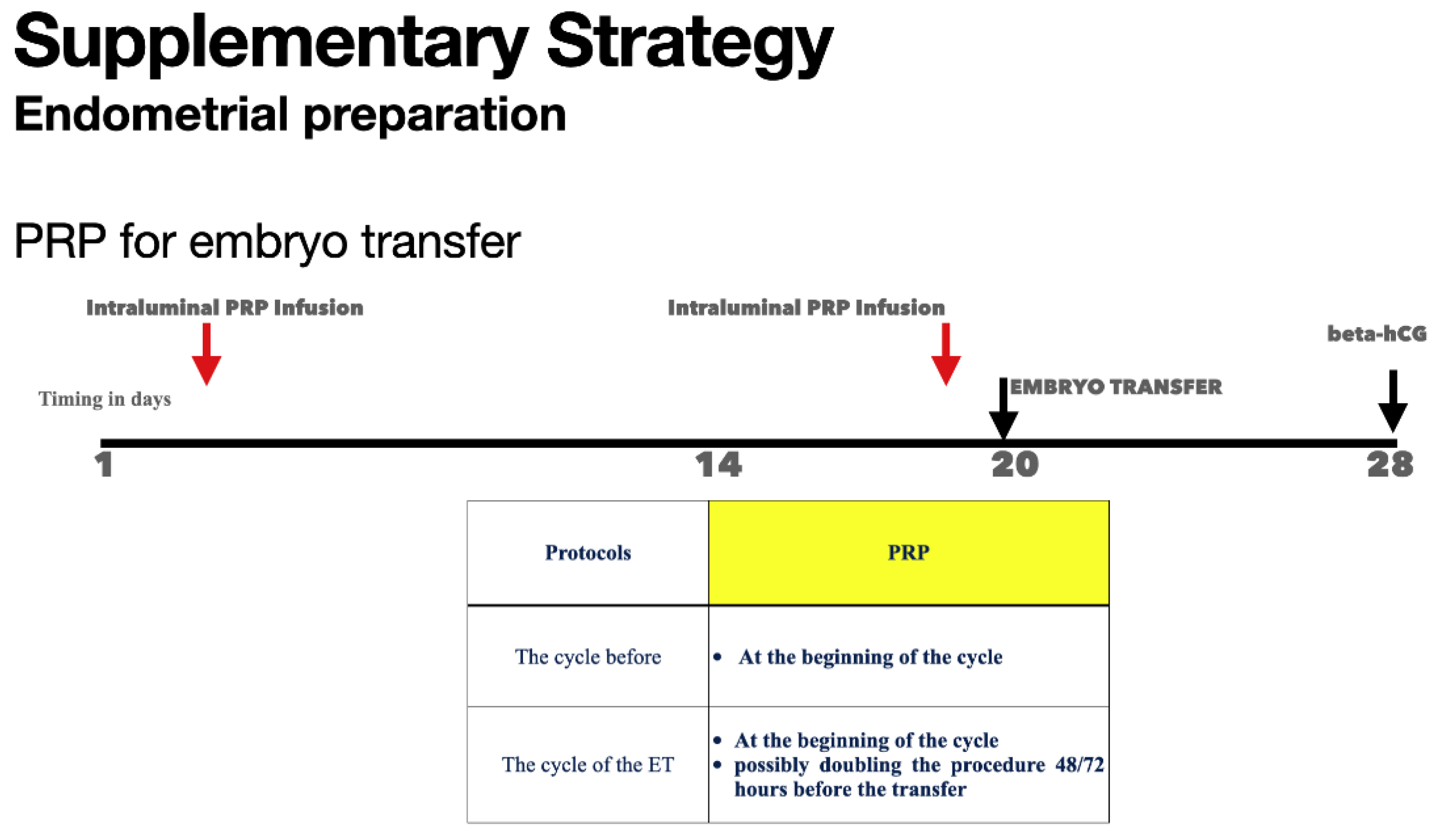

- Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Therapy: PRP enhances vascularization, increases VEGF expression, and stimulates proliferation, supporting thickness and receptivity (Huniadi A et al., 2023; Stewart J Russel et al., 2022; Shalma NM et al., 2023).

- Granulocyte-Colony Stimulating Factor (G-CSF): Improves thickness and pregnancy outcomes when injected into the uterine cavity (Lebovitz O et al., 2014; Gleicher N et al., 2013; Tehraninejad E et al., 2015; Sarvi F et al., 2017; Kamath MS et al., 2020).

-

Sildenafil: Enhances uterine blood flow by potentiating nitric oxide effects, leading to better endometrial proliferation and preparation (Li X et al., 2021).

- ◦

- Dehghani-Firouzabadi et al. (2013): Increased thickness and improved implantation and pregnancy rates.

- ◦

- Li et al. (2020): Meta-analysis showed increased thickness and improved pregnancy outcomes.

- ◦

- El-Maghrabi et al. (2020): Improved thickness and pregnancy rates in frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles.

- ◦

- Firouzabadi et al. (2013): Enhanced endometrial preparation and improved implantation chances.

- ◦

- Moini et al. (2020): Improved thickness and receptivity, contributing to higher success rates.

3.5. Endometrial Scratching

- Procedure: Causes minor injury to endometrium before transfer, inducing an inflammatory response that promotes tissue repair and growth (Lensen SF et al., 2021).

- Pros: Increased implantation rates in some studies (Barash et al., 2003; Aflatoonian et al., 2016; Iakovidou et al., 2023).

- Cons: No significant difference in large-scale RCTs and reviews (Lansen et al., 2019; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2021).

3.6. Uterine Factors

- Myomas: Negative impact when distorting the lumen cavity.

- Salpinges: Infections, occlusions, or stenoses impacting implantation, with salpingectomy often considered.

- Intrauterine Adhesions (IUA): Surgical treatment effective if endometrial functionalis is still working.

- Uterine Abnormalities: Some abnormalities allow for normal implantation, while others may require gestational carriers.

4. Vascularization and Blood Flow

5. Hormonal Environment

6. Cellular Markers of Adequate Endometrial Differentiation for Embryo Nidation

- Pinopodes: Small, finger-like projections on the surface of the endometrial epithelium appear during the implantation window and are believed to facilitate embryo adhesion (Quinn KE et al., 2019; Zhang Y et al., 2021; Marquardt RM et al., 2019).

- Stromal Decidualization: Transformation of endometrial stromal cells into decidual cells is crucial for maintaining pregnancy and preventing early pregnancy loss (Zhang Y et al., 2021; Marquardt RM et al., 2019; Bulletti C et al., 2022).

- Molecular Markers: The expression of specific genes and proteins, such as integrins, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (Stewart CL et al., 1992; Borini A et al., 1997), and homeobox genes (e.g., HOXA10) (Bi Y et al., 2022), is crucial for endometrial receptivity. These markers play roles in cell adhesion, immune modulation, and tissue remodeling (Roberto da Costa RP et al., 2006; Marquardt RM et al., 2019; Zhang Y et al., 2021).

Growth Factors

- VEGF, TGF-β, IGF, HGF, EGF, PDGF: These factors work synergistically through autocrine and paracrine signaling to create a receptive endometrial environment, enhancing the chances of successful implantation and pregnancy (Al-Jefout M et al., 2009; Salamonsen LA et al., 2009; Giudice LC, 2006; Lessey BA, 2002; Dimitriadis E et al., 2005; Zhu LJ et al., 2000).

- Homeobox A10 (HOXA10): Regulates gene expression during endometrial differentiation, with impaired expression linked to lower implantation rates (Bagot CN et al., 2001; Roberto da Costa RP et al., 2006; Marquardt RM et al., 2019; Zhang Y et al., 2021).

- Prostaglandins: Regulate inflammation, vascular permeability, and uterine contractions, critical for implantation (Roberto da Costa RP et al., 2006; Marquardt RM et al., 2019; Zhang Y et al., 2021).

7. Endometrial Preparation for Embryo Transfer

- Oral Administration: Convenient and easy to adjust dosage but subject to first-pass metabolism, leading to variable serum levels and potential side effects like nausea or liver enzyme alterations.

- Transdermal Administration: Provides steady hormone levels and bypasses first-pass metabolism, generally with fewer side effects, though it may cause skin irritation and requires frequent patch changes.

- Estradiol Gels: Similar benefits to patches but can be messy and risk transferring the gel to others via skin contact.

- Vaginal Administration: Delivers high local concentrations with reduced systemic side effects but may be uncomfortable for some patients.

- Intramuscular (IM) or Subcutaneous (SC) Injections: Provide consistent hormone levels with less frequent dosing but can be painful with potential injection site reactions.

- Vaginal Administration: Provides high local concentrations with effective endometrial transformation and lower systemic side effects but may be messy or uncomfortable.

- Intramuscular Injections: Ensure high serum levels and reliable endometrial transformation but can be painful with injection site reactions.

- Oral Administration: Convenient but has lower bioavailability and potential systemic side effects like drowsiness.

7.1. Alternative Methods for Needle Phobia or Oral Tablet Aversion

- Estradiol:

- Transdermal Patches: Steady hormone release (e.g., Vivelle-Dot, Climara).

- Vaginal Gels: Steady release of estradiol (e.g., Divigel, Estrogel).

- Vaginal Tablets or Rings: Localized hormone delivery with systemic absorption (e.g., Vagifem, Estring).

- Progesterone:

- Intramuscular or Subcutaneous Administration: Mimics endogenous production.

- Vaginal Suppositories or Capsules: Direct delivery with minimal systemic side effects (e.g., Endometrin, Prometrium).

- Vaginal Gels: Consistent levels with vaginal application (e.g., Crinone).

- Transdermal Creams: Variable absorption and efficacy.

- Estradiol Patches: Apply one patch (0.1 mg/day), replace every 3-4 days.

- Progesterone Vaginal Gel: Administer 90 mg daily.

- Monitoring: Regular checks of hormone levels and endometrial thickness.

- Adjustments: Based on individual response and side effects.

7.2. Schematic Schedule for HRT in Embryo Nidation Preparation:

- Days 1-14: Start low, increase gradually.

- Day 1-4: 2 mg daily (oral or patch).

- Day 5-8: 4 mg daily.

- Day 9-12: 6 mg daily.

- Day 13-14: 8 mg daily.

- Start on Day 15:

- Days 15-28: 200 mg twice daily (vaginal or oral).

- Day 15-28: Continue estradiol 8 mg daily.

- Estradiol: 8 mg daily.

- Progesterone: 200 mg twice daily.

- If pregnant: Continue as per physician’s advice.

- If not pregnant: Stop hormone therapy.

7.3. Strategies for Inadequate Endometrial Thickness

- Estradiol: Administered orally, transdermally, or subcutaneously.

- Progesterone: Multiple routes including IM, vaginal, and subcutaneous.

- Dydrogesterone: Oral progesterone analogue combined with vaginal progesterone.

- Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP): Intrauterine administration to improve thickness and receptivity( Tang Y et al., 2023).

- Stem Cell Therapy: Using stem cell-derived exosomes to regenerate endometrial tissue.

- Endometrial Thickness: Critical for embryo nidation (LU J et al., 2024).

- ERA Test: Does not significantly improve ongoing pregnancy rates compared to standard protocols (Doyle JO et al., 2022).

8. The Possible Role of Endometritis

9. Initial Assessment and Preparation

10. Addressing Chronic Endometritis

11. Metabolism of Estradiol and Progesterone in the Endometrium

12. Schematic Design of Steroid Hormone Action ( Bulletti C et al 1988a,b)

13. Detailed Pathway of Steroid Hormone Action in Endometrial Tissue

14. Detailed Molecular Mechanisms of Hormonal Actions

15. Advanced Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches

16. Conclusions

| Features | Facts |

|---|---|

| Endometrial Thickness: | Optimal Thickness: The endometrial lining should ideally be between 7-14 mm for optimal implantation rates. Thickness below 7 mm is often associated with lower implantation rates and higher chances of miscarriage . Triple-Line Pattern: A trilaminar or “triple-line” pattern observed on ultrasound around the time of embryo transfer is often indicative of a receptive endometrium . |

| Hormonal Environment: | Estrogen and Progesterone: Adequate levels of estrogen are necessary to stimulate endometrial growth, while progesterone transforms the proliferative endometrium into a secretory lining, preparing it for embryo implantation through the cascade of biochemical and physical modifications called pre-decidualization.Water inclusion in decidualized stromal cells contribute to enlarge the endometrial thickness produced from epithelial cells proliferation induced from estrogens Synchronization: Proper synchronization between the endometrial development and the embryo stage is critical for successful implantation. This is often achieved by mimicking the natural menstrual cycle through hormonal supplementation . The Era test or similar conceptual tests were not effective in the embryo synchronization transfer. |

| Endometrial Receptivity | Receptive Window: The period during which the endometrium is most receptive to embryo implantation is known as the “window of implantation,” typically occurring 6-10 days after ovulation . Window of implantation is what we have when the implantation occur. It is not possible to call that when does not occur Molecular Markers: Several molecular markers such as integrins, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), and homeobox (HOX) genes are involved in creating a receptive endometrial environment . |

| Methods | Interventions |

| Abnormal Transport of Steroid Hormones to Endometrial Cells ion | Hormone Transport Proteins: Steroid hormones in the blood are largely bound ( 98%) to transport proteins such as sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and albumin. Only the free, unbound fraction is biologically active and capable of entering cells. An abnormal balance between protein-bound and free hormones can affect the availability of hormones to the endometrial cells. High levels of SHBG can reduce the free hormone fraction, limiting the amount available for endometrial stimulation . Receptor Functionality: The effectiveness of hormone therapy also depends on the functionality and density of hormone receptors in the endometrium. Variations in the expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors can influence the response to HRT . Genetic mutations or polymorphisms in hormone receptors may alter their binding affinity and response to hormone therapy . Blood Flow and Vascularization: Adequate blood flow to the endometrium is crucial for delivering hormones. Conditions that impair uterine blood flow, such as uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, or previous surgeries, can hinder hormone delivery and endometrial growth . |

| Variations in Endometrial Extraction of Steroids from Circulation. The extraction of steroid hormones from the bloodstream by endometrial cells can vary due to several reasons | Metabolic Clearance Rate (MCR):The MCR of circulating hormones refers to the rate at which hormones are removed from the bloodstream. A high MCR can reduce the overall availability of hormones for endometrial uptake . Factors influencing MCR include liver function, enzymatic activity, and overall metabolic health as well as body temperature and exercise. Local Metabolism:Endometrial cells can locally metabolize steroid hormones. Enzymes such as aromatase, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, and sulfatase play roles in converting hormones to their active or inactive forms within the endometrium . Dysregulation of these enzymes can affect the local concentration of active hormones, influencing endometrial response. The metabolism of steroids to the gluco-conjugates ans sulfo-conjugates are the depending from the source . If exogenous also from the route of administration being the fisrt liver pass promoting high sulfo-conjugation. Hormone Resistance: Some women may exhibit endometrial resistance to estrogen or progesterone, where despite adequate levels of circulating hormones, the endometrial response is suboptimal. This can be due to receptor desensitization or post-receptor signaling defects |

| Factors Contributing to Inadequate Endometrial Response | Age and Ovarian Reserve: Advanced age and diminished ovarian reserve are associated with poorer endometrial responses to hormone therapy. This is often due to reduced receptor sensitivity and altered endometrial receptivity . Body Mass Index (BMI): Both low and high BMI can negatively impact endometrial thickness. Obesity can alter hormone metabolism and increase the levels of SHBG, reducing free hormone availability. Underweight individuals may have insufficient hormone production and transport . Chronic Inflammation: Conditions like endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), or chronic endometritis can cause a pro-inflammatory environment that negatively impacts endometrial growth and receptivity . Previous Uterine Surgery: Surgeries such as curettage or myomectomy can cause scarring (Asherman’s syndrome) and impair endometrial regeneration and response to hormonal stimulation . |

| Methods | Interventions |

|---|---|

| Hormonal Supplementation | Estradiol: Oral, transdermal, or injectable estradiol can be used to increase endometrial thickness. Higher doses or extended duration of administration may be required for patients with thin linings Progesterone: Vaginal, Intramuscolar, Subcutaneous with oral as second line. Higher doses with moderate extended duration may be required Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG): Low-dose hCG administration can also stimulate endometrial growth and improve thickness . |

| Adjuvant Therapies | Low-Dose Aspirin: May improve endometrial blood flow, enhancing thickness and receptivity . Pentoxifylline and Vitamin E: These agents are believed to improve endometrial thickness by enhancing blood flow and reducing oxidative stress . |

| Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Therapy | Intrauterine Infusion: PRP therapy involves the infusion of autologous platelet-rich plasma into the uterine cavity to stimulate endometrial growth and improve implantation rates in patients with refractory thin endometrium |

| Granulocyte-Colony Stimulating Factor (G-CSF) | Uterine Injection: G-CSF has been shown to improve endometrial thickness and pregnancy outcomes when injected directly into the uterine cavity in patients with thin endometrium |

| Endometrial Scratching | Procedure: This involves causing a minor injury to the endometrium prior to the embryo transfer cycle, which is believed to enhance endometrial receptivity by inducing an inflammatory response that promotes tissue repair and growth . This issue is still debated |

| Lifestyle and Dietary Changes | Healthy Diet and Exercise: Ensuring adequate nutrition and maintaining a healthy weight can positively impact endometrial health Stress Reduction Managing stress through relaxation techniques, counseling, or yoga can also improve overall reproductive health . |

Authors Contributions

Ethical Considerations

References

- M. Maged, H. Rashwan, S. AbdelAziz, W. Ramadan, W. A. I. Mostafa, A. A. Metwally, M. Katta, “Randomized controlled trial of the effect of endometrial injury on implantation and clinical pregnancy rates during the first ICSI cycle,” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 140, no. 2 (2018). 211–216. [CrossRef]

- Abid H.B., Fekih M., Fathallah K., Chachia S., Bibi M., Khairi H. Office hysteroscopy before first in vitro fertilization.

- Aflatoonian et al. “Endometrial scratching effect on implantation and pregnancy rates in patients with recurrent implantation failure. A randomized clinical trial.

- Afsaneh Shah Bakhsh, Narges Maleki, Mohammad Reza Sadeghi, Ali SadeghiTabar, Maryam Tavakoli, Simin Zafardoust, Atousa Karimi, Sonai Askari, Sheyda Jouhari, Afsaneh Mohammadzadeh Effects of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma in women with repeated implantation failure undergoing assisted reproduction JBRA Assisted Reproduction 2022;26(1). [CrossRef]

- Agarwal M., Mettler L., Jain S., Meshram S., Günther V., Alkatout I.: Management of a thin endometrium by hysteroscopic instillation of platelet-rich plasma into the endomyometrial junction: a pilot study. J Clin Med 2020; 9: pp. 2795.

- Aghajanova, L. (2010). Molecular basis for implantation failure in endometriosis: On the road to discovery with next-generation sequencing. Fertility and Sterility, 94(7), 2803-2804.

- 7. Al-Ghamdi A., Coskun S., Al-Hassan S., Al-Rejjal R., Awartani K.: The correlation between endometrial thickness and outcome of in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) outcome. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2008; 6: pp. 1-5.

- Al-Jefout, M., et al. (2009). “Vascular endothelial growth factor and endometriosis.” Obstetrics and Gynecology International, [PMID: 19259362].

- 9. Alur-Gupta S., Hopeman M., Berger D.S., Gracia C., Barnhart K.T., Coutifaris C., et. al.: Impact of method of endometrial preparation for frozen blastocyst transfer on pregnancy outcome: a retrospective cohort study. Fertil Steril 2018; 110: pp. 680-686.

- Arici, A., et al. (1995). Leukemia inhibitory factor expression in human endometrium: modulation by exogenous ovarian steroids. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 86(5), 798-803.

- 11. Asch Schuff RH, Suarez J, Laugas N, Zamora Ramirez ML, Alkon T. Artificial intelligence model utilizing endometrial analysis to contribute as a predictor of assisted reproductive technology success. Journal of IVF-Worldwide. 2024;2(2):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Ata B. Liñán A. Kalafat E. Ruíz F. Melado L. Bayram A. Elkhatib I. Lawrenz B. Fatemi H.M Effect of the endometrial thickness on the live birth rate: insights from 959 single euploid frozen embryo transfers without a cutoff for thickness.Fertil Steril. 2023; 2 (S0015-0282(23)00168-1). [CrossRef]

- 13. Aydin T., Kara M., Nurettin T.: Relationship between endometrial thickness and in vitro fertilization-intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcome. Int J Fertil Steril 2013; 7: pp. 29-34.

- Bagot, C. N., Kliman, H. J., & Taylor, H. S. (2001). Human endometrial stromal cell decidualization requires cyclooxygenase-2, cyclooxygenase-1, and progesterone-induction of HOXA10. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 86(9), 4367-4372.

- Barad, D. H., & Gleicher, N. (2006). Effect of platelet-derived growth factors on the outcome of in vitro fertilization in patients with thin endometrium: a pilot study. Fertility and Sterility, 86(4), 1048-1050.

- Barash et al. “Local injury to the endometrium doubles the incidence of successful pregnancies in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization.” Fertility and Sterility, 2003.

- Baskin D.S., Hosobuchi Y., Grevel J.C.: Treatment of experimental stroke with opiate antagonists: effects on neurological function, infarct size, and survival. J Neurosurg 1986; 64: pp. 99-103.

- Begum Mathyk, Adina Schwartz, Alan DeCherney, Baris Ata A critical appraisal of studies on endometrial thickness and embryo transfer outcome RBMO VOLUME 47 ISSUE 4 2023 103259 © 2023 Reproductive Healthcare Ltd. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

- Ben Yuan*, Shuhong Luo*, Junbiao Mao, Bingbing Luo, Junling Wang Effects of intrauterine infusion of platelet-rich plasma on hormone levels and endometrial receptivity in patients with repeated embryo implantation failure Am J Transl Res 2022;14(8):5651-5659 www.ajtr.org /ISSN:1943-8141/AJTR0143685.

- Bi Y, Huang W, Yuan L, Chen S, Liao S, Fu X, Liu B, Yang Y. HOXA10 improves endometrial receptivity by upregulating E-cadherin†. Biol Reprod. 2022 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borini A, Bulletti C, CAttoli M, Serrao L, Polli V, Alfieri S, Flamigni Use of Recombinant Leukemia Inhibitory Factor in Embryo Implantation Volume828, Issue1 Uterus, The: Endometrium and Myometrium September 1997 Pages 157-161. [CrossRef]

- Brodeur TY, Hanson B, Maredia NN, Tessier KM, Esfandiari N, Dahl S, Batcheller A. Increasing Endometrial Thickness Beyond 8 mm Does Not Alter Clinical Pregnancy Rate After Single Euploid Embryo Transfer. Reprod Sci. 2024 Apr;31(4):1045-1052. Epub 2023 Nov 13. PMID: 37957470; PMCID: PMC11015161. [CrossRef]

- Bu Z., Sun Y.: The impact of endometrial thickness on the day of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) administration on ongoing pregnancy rate in patients with different ovarian response. PLoS One 2015; 10:.

- Bulletti C, De Ziegler D, Albonetti A, Flamigni C. Paracrine regulation of menstruation1Paper presented at the workshop on Paracrine Mechanisms in Female Reproduction, Seville, Spain, June 1997.1, Journal of Reproductive Immunology, Volume 39, Issues 1–2, 1998, Pages 89-104, ISSN 0165-0378.

- Bulletti C, Galassi A, Jasonni VM, Martinelli G, Tabanelli S, Flamigni C. Basement membrane components in normal hyperplastic and neoplastic endometrium. Cancer. 1988 Jul 1;62(1):142-9. PMID: 3383111. [CrossRef]

- Bulletti, C et al. Extraction of estrogens by human perfused uterus American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 1988, Volume 159, Issue 2, 509 - 515.

- Bulletti, C., de Ziegler, D., Flamigni, C., Giacomucci, E., Polli, V., Bolelli, G., & Marian, L. (1998). Targeted drug delivery in gynaecology: the first uterine pass effect. Human Reproduction, 13(4), 998-1004.

- Bulletti, C., de Ziegler, D., Polli, V., Diotallevi, L., Del Monte, G., & Cicinelli, E. (2002). Uterine contractility during the menstrual cycle. Human Reproduction, 17(4), 877-883.

- Bulletti, C., de Ziegler, D., Polli, V., Diotallevi, L., Del Monte, G., Cicinelli, E. (2001). The role of progesterone in uterine contractility and embryo implantation. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 18(7), 443-446.

- Bulletti, C., et al. (1998). Electromechanical activities of human uteri during extra-corporeal perfusion with ovarian steroids. Human Reproduction, 8, 1558-1563.

- Bulletti, C., et al. (2005). Uterine contractility and embryo implantation. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 17(3), 265-276.

- Bulletti, C.; Bulletti, F.M.; Sciorio, R.; Guido, M. Progesterone: The Key Factor of the Beginning of Life. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14138. [CrossRef]

- Chang Y., Li J., Wei L.N., Pang J., Chen J., Liang X.: Autologous platelet-rich plasma infusion improves clinical pregnancy rate in frozen embryo transfer cycles for women with thin endometrium. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98:.

- Check J.H., Cohen R.: Live fetus following embryo transfer in a woman with diminished egg reserve whose maximal endometrial thickness was less than 4 mm. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2011; 38: pp. 330-332.

- Check, J. H., Dietterich, C., Lurie, D., & Nazari, A. (2003). The effect of endometrial thickness and echo pattern on pregnancy rates during assisted reproduction. Fertility and Sterility, 80(5), 1130-1135.

- Chen X.J., Wu L.P., Lan H.L., Zhang L., Zhu Y.M.: Clinical variables affecting the pregnancy rate of intracervical insemination using cryopreserved donor spermatozoa: a retrospective study in china. Int J Fertil Steril 2012; 6: pp. 179-184.

- Chen, S. L., Wu, F. R., Luo, C., Chen, X., Shi, X. H., Zheng, H. Y., & Ni, Y. P. (2010). Endometrial thickness is a reliable predictor of pregnancy in in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer cycles. Fertility and Sterility, 94(6), 1960-1963.

- Cochrane Library Randomized controlled trial of the effect of endometrial injury on implantation and clinical pregnancy rates during the first ICSI cycle Cochrane Library https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-01621917/full.

- Craciunas L. Gallos I. Chu J. Bourne T. Quenby S. Brosens J.J. Coomarasamy A. Conventional and modern markers of endometrial receptivity: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Hum Reprod Update. 2019; 25: 202-223. 2: 2019; 25. [CrossRef]

- Csapo AI, Pulkkinen MO, Wiest WG. Effects of luteectomy and progesterone replacement therapy in early pregnant patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973 Mar 15;115(6):759-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(73)90517-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Geyter C. Schmitter M. De Geyter M. Nieschlag E. Holzgreve W.Schneider H.P. Prospective evaluation of the ultrasound appearance of the endometrium in a cohort of 1,186 infertile women.Fertil Steril. 2000; 73: 106-113. [CrossRef]

- de Ziegler, D., Bulletti, C., de Moustier, B. (1998). Endometrial Preparation. In: Sauer, M.V. (eds) Principles of Oocyte and Embryo Donation. Springer, New York, NY. Sauer. [CrossRef]

- Dehghani Firouzabadi R, Davar R, Hojjat F, Mahdavi M. Effect of sildenafil citrate on endometrial preparation and outcome of frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles: a randomized clinical trial. Iran J Reprod Med. 2013 Feb;11(2):151-8. [PubMed]

- Dehghani Firouzabadi R, Davar R, Hojjat F, Mahdavi M. Effect of sildenafil citrate on endometrial preparation and outcome of frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles: a randomized clinical trial. Iran J Reprod Med. 2013 Feb;11(2):151-8. PMID: 24639741; PMCID: PMC3941353. PMC3941353: PMCID.

- Demirol, A., & Gurgan, T. (2004). Effect of endometrial thickness on implantation rates during in vitro fertilization. Fertility and Sterility, 82(3), 431-434.

- Díaz-Gimeno, P., Horcajadas, J. A., Martínez-Conejero, J. A., Esteban, F. J., Alamá, P., Pellicer, A., & Simón, C. (2011). A genomic diagnostic tool for human endometrial receptivity based on the transcriptomic signature. Fertility and Sterility, 95(1), 50-60.

- Dimitriadis, E., et al. (2000). Cytokines, chemokines and growth factors in endometrium related to implantation. Human Reproduction Update, 6(5), 485-501.

- Dimitriadis, E., et al. (2005). “Leukemia inhibitory factor and embryo implantation.” Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 67(1-2), 21-29. [CrossRef]

- Domar AD, Clapp D, Slawsby EA, Dusek J, Kessel B, Freizinger M. Impact of group psychological interventions on pregnancy rates in infertile women. Fertil Steril. 2000 Apr;73(4):805-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00493-8. Erratum in: Fertil Steril 2000 Jul;74(1):190. PMID: 10731544. 805-11. [CrossRef]

- Doyle N, Jahandideh S, Hill MJ, Widra EA, Levy M, Devine K. Effect of Timing by Endometrial Receptivity Testing vs Standard Timing of Frozen Embryo Transfer on Live Birth in Patients Undergoing In Vitro Fertilization: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022;328(21):2117–2125. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J. O., et al. (2022). “Double-blind, multicenter, randomized clinical trial to compare the live birth rate in patients who had ERA or not in their single EET cycle.” Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. Retrieved from Springer (Frontiers).

- Eftekhar M., Neghab N., Naghshineh E., Khani P.: Can autologous platelet rich plasma expand endometrial thickness and improve pregnancy rate during frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycle? A randomized clinical trial. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2018;57:810–3. Published correction appears in Taiwan. J Obstet Gynecol 2021; 60: pp. 973.

- Eftekhar, M., Miraj, S., & Molaei, B. (2017). Can autologous platelet-rich plasma expand endometrial thickness and improve pregnancy rate during frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycle? A randomized clinical trial. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 56(6), 725-729.

- Eftekhar, M., Sayadi, M., Arabjahvani, F., & Khani, P. (2014). Effect of low-dose hCG on endometrial thickness and IVF outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Human Fertility, 17(2), 130-135.

- El-Mazny A., Abou-Salem N., El-Sherbiny W., Saber W.: Outpatient hysteroscopy: a routine investigation before assisted reproductive techniques?. Fertil Steril 2011; 95: pp. 272-276.

- El-Toukhy T., Coomarasamy A., Khairy M., Sunkara K., Seed P., Khalaf Y., et. al.: The relationship between endometrial thickness and outcome of medicated frozen embryo replacement cycles. Fertil Steril 2008; 89: pp. 832-839.

- Ensieh S. Tehraninejad, Norieh G. Kashani, Ali Hosseini and Azam Tarafdari Autologous platelet-rich plasma infusion does not improve pregnancy outcomes in frozen embryo transfer cycles in women with history of repeated implantation failure without thin endometrium J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ershadi S, Noori N, Dashipoor A, Ghasemi M, Shamsa N. Evaluation of the effect of intrauterine injection of platelet rich plasma on the pregnancy rate of patients with a history of implantation failure in the in vitro fertilization cycle. J Family Med Prim Care 2022;11:2162-6.

- ESHRE Working Group on Recurrent Implantation Failure; Cimadomo D, de Los Santos MJ, Griesinger G, Lainas G, Le Clef N, McLernon DJ, Montjean D, Toth B, Vermeulen N, Macklon N. ESHRE good practice recommendations on recurrent implantation failure. Hum Reprod Open. 2023 Jun 15;2023(3):hoad023. https://doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoad023. PMID: 37332387; PMCID: PMC10270320. hoad023: 2023(3). [CrossRef]

- Eva R. Groenewoud, Ben J. Cohlen, Amani Al-Oraiby, Egbert A. Brinkhuis, Frank J. M. Broekmans, Jan-Peter de Bruin, Grada van Dool, Katrin Fleisher, Jaap Friederich, Mariëtte Goddijn, Annemieke Hoek, Diederik A. Hoozemans, Eugenie M. Kaaijk, Caroliene A. M. Koks, Joop S. E. Laven, Paul J. Q. van der Linden, A. Petra Manger, Minouche van Rumste, Taeke Spinder, Nick S. Macklon Influence of endometrial thickness on pregnancy rates in modified natural cycle frozen-thawed embryo transfer Volume97, Issue7 July 2018 Pages 808-815.

- Fetih AN, Habib DM, Abdelaal II, Hussein M, Fetih GN, Othman ER. Adding sildenafil vaginal gel to clomiphene citrate in infertile women with prior clomiphene citrate failure due to thin endometrium: a prospective self-controlled clinical trial. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2017 Mar;9(1):21-27.

- Fleischer A.C. Herbert C.M. Sacks G.A. Wentz A.C. Entman S.S. James A.E.Sonography of the endometrium during conception and nonconception cycles of in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer.Fertil Steril. 1986; 46: 442-447. [CrossRef]

- Gallos I.D. Khairy M. Chu J. Rajkhowa M. Tobias A. Campbell A. Dowell K. Fishel S. Coomarasamy A. Optimal endometrial thickness to maximize live births and minimize pregnancy losses: Analysis of 25,767 fresh embryo transfers. Reprod Biomed Online. 2018; 37: 542-548. [CrossRef]

- Gao G., Cui X., Li S., Ding P., Zhang S., Zhang Y.: Endometrial thickness and IVF cycle outcomes: a meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2020; 40: pp. 124-133. [CrossRef]

- Gill P, Ata B, Arnanz A, Cimadomo D, Vaiarelli A, Fatemi HM, Ubaldi FM, Garcia-Velasco JA, Seli E. Does recurrent implantation failure exist? Prevalence and outcomes of five consecutive euploid blastocyst transfers in 123 987 patients. Hum Reprod. 2024 May 2;39(5):974-980. [CrossRef]

- Giudice, L. C. (2006). “Endometrium in PCOS: Implantation and predisposition to endocrine CA.” Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 20(2), 235-244. [CrossRef]

- Gleicher N., Kim A., Michaeli T., Lee H.J., Shohat-Tal A., Lazzaroni E., et. al.: A pilot cohort study of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in the treatment of unresponsive thin endometrium resistant to standard therapies. Hum Reprod 2013; 28: pp. 172-177.

- Glujovsky D., Pesce R., Sueldo C., Quinteiro Retamar A.M., Hart R.J., Ciapponi A.: Endometrial preparation for women undergoing embryo transfer with frozen embryos or embryos derived from donor oocytes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 10: pp. CD006359.

- Gonen Y. Casper R.F. Jacobson W. Blankier J. Endometrial thickness and growth during ovarian stimulation: a possible predictor of implantation in in vitro fertilization.Fertil Steril. 1989; 52: 446-450. 4: 1989; 52. [CrossRef]

- Greco E., Litwicka K., Arrivi C., Varricchio M., Caragia A., Greco A., et. al.: The endometrial preparation for frozen-thawed euploid blastocyst transfer: a prospective randomized trial comparing clinical results from natural modified cycle and exogenous hormone stimulation with GnRH agonist. J Assist Reprod Genet 2016; 33: pp. 873-884.

- Groenewoud E.R., Cohlen B.J., Al-Oraiby A., Brinkhuis E.A., Broekmans F.J., de Bruin J.P., et. al.: A randomized controlled, non-inferiority trial of modified natural versus artificial cycle for cryo-thawed embryo transfer. Hum Reprod 2016; 31: pp. 1483-1492.

- Gutarra-Vilchez R.B., Cosp X.B., Glujovsky D., Viteri-García A., Runzer-Colmenares F.M., Martinez-Zapata M.J.: Vasodilators for women undergoing fertility treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 10: pp. CD010001.

- Hakan Coksuer, Yesim Akdemir & Mert Ulas Barut (2019): Improved invitro fertilization success and pregnancy outcome with autologous platelet-rich plasma treatment in unexplained infertility patients that had repeated implantation failure history, Gynecological Endocrinology. [CrossRef]

- Hambartsoumian, E. (1998). Endometrial leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) as a possible cause of unexplained infertility and multiple failures of implantation. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 39(2), 137-143.

- Hanna Achache, Ariel Revel, Endometrial receptivity markers, the journey to successful embryo implantation, Human Reproduction Update, Volume 12, Issue 6, November/December 2006, Pages 731–746. [CrossRef]

- Hanstede M.M., Van Der Meij E., Goedemans L., Emanuel M.H.: Results of centralized Asherman surgery, 2003-2013. Fertil Steril 2015; 104: pp. 1561-1568; Pundir J. et al 2014.

- Hanting Zhao, Shuanggang Hu, Jia Qi, Shiyao Wang, Yanzhi Du Yun Sun Increased expression of HOXA11-AS attenuates endometrial decidualization in recurrent implantation failure patients ORIGINAL ARTICLE VOLUME 30, ISSUE 4, P1706-1720, APRIL 06, 2022.

- Huniadi, A.; Zaha, I.A.; Naghi, P.; Stefan, L.; Sachelarie, L.; Bodog, A.; Szuhai-Bimbo, E.; Macovei, C.; Sandor, M. Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Efficacy on Endometrial Thickness and Infertility: A Single-Centre Experience from Romania. Medicina 2023, 59, 1532. [CrossRef]

- Iakovidou, M.C., Kolibianakis, E., Zepiridis, L. et al. The role of endometrial scratching prior to in vitro fertilization: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 21, 89 (2023). [CrossRef]

- John D Aplin, Adam Stevens, Use of ‘omics for endometrial timing: the cycle moves on, Human Reproduction, Volume 37, Issue 4, April 2022, Pages 644–650. [CrossRef]

- Ju, W., Wei, C., Lu, X. et al. Endometrial compaction is associated with the outcome of artificial frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles: a retrospective cohort study. J Assist Reprod Genet 40, 1649–1660 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kamath M.S., Kirubakaran R., Sunkara S.K.: Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor administration for subfertile women undergoing assisted reproduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 1: pp. CD013226.

- Kasius A, Smit JG, Torrance HL, Eijkemans MJ, Mol BW, Opmeer BC, Broekmans FJ. Endometrial thickness and pregnancy rates after IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014 Jul-Aug;20(4):530-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim H, Shin JE, Koo HS, Kwon H, Choi DH and Kim JH (2019) Effect of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma Treatment on Refractory Thin Endometrium During the Frozen Embryo Transfer Cycle: A Pilot Study. Front. Endocrinol. 10:61. [CrossRef]

- Kitaya, K., Matsubayashi, H., Takaya, Y., Nishiyama, R., Yamaguchi, K., & Takeuchi, T. (2017). Live birth rate following oral antibiotic treatment for chronic endometritis in infertile women with repeated implantation failure. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 78, e12719. (SpringerLink). [CrossRef]

- Kolibianakis E.M., Zikopoulos K.A., Fatemi H.M., Osmanagaoglu K., Evenpoel J., Van Steirteghem A., et. al.: Endometrial thickness cannot predict ongoing pregnancy achievement in cycles stimulated with clomiphene citrate for intrauterine insemination. Reprod Biomed Online 2004; 8: pp. 115-118.

- Kovacs P., Matyas S., Boda K., Kaali S.G.: The effect of endometrial thickness on IVF/ICSI outcome. Hum Reprod 2003; 18: pp. 2337-2341.

- Kumbak B., Erden H.F., Tosun S., Akbas H., Ulug U., Bahçeci M.: Outcome of assisted reproduction treatment in patients with endometrial thickness less than 7 mm. Reprod Biomed Online 2009; 18: pp. 79-84.

- Kupesic, S., Kurjak, A., & Bjelos, D. (2001). Vascularity of the endometrium and subendometrial region measured by three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasonography and implantation in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 18(9), 557-560.

- Kusumi M., Ihana T., Kurosawa T., Ohashi Y., Tsutsumi O.: Intrauterine administration of platelet-rich plasma improves embryo implantation by increasing the endometrial thickness in women with repeated implantation failure: a single-arm self-controlled trial. Reprod Med Biol 2020; 19: pp. 350-356.

- Labrosse J., Lobersztajn A., Pietin-Vialle C., Villette C., Dessapt A.L., Jung C., et. al.: Comparison of stimulated versus modified natural cycles for endometrial preparation prior to frozen embryo transfer: a randomized controlled trial. Reprod Biomed Online 2020; 40: pp. 518-524.

- Lebovitz, O., & Orvieto, R. (2014). Treating patients with “thin” endometrium–an ongoing challenge. Gynecological Endocrinology, 30(6), 409-414.

- Leila Nazari & Saghar Salehpour & Sedighe Hosseini & Samaneh Sheibani & Hossein Hosseinirad The Effects of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma on Pregnancy Outcomes in Repeated Implantation Failure Patients Undergoing Frozen Embryo Transfer: A Randomized Controlled Trial Reproductive Sciences (2022) 29:993-1000. [CrossRef]

- Leila Nazari, Saghar Salehpour, Maryam Sadat Hosseini & Parisa Hashemi Moghanjoughi (2019): The effects of autologous platelet-rich plasma in repeated implantation failure: a randomized controlled trial, Human Fertility. [CrossRef]

- Lensen SF, Armstrong S, Gibreel A, Nastri CO, Raine-Fenning N, Martins WP. Endometrial injury in women undergoing in vitro fertilisation (IVF). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Jun 10;6(6):CD009517. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessey BA. The role of the endometrium during embryo implantation. Hum Reprod. 2000 Dec;15 Suppl 6:39-50. PMID: 11261482.

- Lessey, B. A. (2002). “Adhesion molecules and implantation.” Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 55(1-2), 101-112. [CrossRef]

- Lessey, B. A., & Young, S. L. (2019). What exactly is endometrial receptivity? Clinical obstetrics and gynecology, 62(2), 356-367.

- Lessey, B. A., Damjanovich, L., Coutifaris, C., Castelbaum, A., Albelda, S. M., & Buck, C. A. (1992). Integrin adhesion molecules in the human endometrium. Correlations with the normal and abnormal menstrual cycle. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 90(1), 188-195.

- Li, Xin, et al. “Effect of Sildenafil Citrate on Treatment of Infertility in Women with a Thin Endometrium: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of International Medical Research, vol. 48, no. 11, 2020, p. 030006052096958. [CrossRef]

- Liao S., Wang R., Hu C., Pan W., Pan W., Yu D., et. al.: Analysis of endometrial thickness patterns and pregnancy outcomes considering 12,991 fresh IVF cycles. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2021; 21: pp. 1-13.

- Liao X., Li Z., Dong X., Zhang H.: Comparison between oral and vaginal estrogen usage in inadequate endometrial patients for frozen-thawed blastocysts transfer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014; 7: pp. 6992-6997.

- Liu K.E., Hartman M., Hartman A., Luo Z.C., Mahutte N.: The impact of a thin endometrial lining on fresh and frozen-thaw IVF outcomes: an analysis of over 40,000 embryo transfers. Hum Reprod 2018; 33: pp. 1883-1888. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yixuan MDa; Ma, Lijuan MD, PhDb,c; Zhu, Min MDa; Yin, Huirong MDa; Yan, Hongli MD, PhDa; Shi, Minfeng MD, PhDa,*. STROBE-GnRHa pretreatment in frozen-embryo transfer cycles improves clinical outcomes for patients with persistent thin endometrium: A case-control study. Medicine 101(31):p e29928, August 05, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., Mao, X., He, Y. et al. Efficacy of endometrial receptivity testing for recurrent implantation failure in patients with euploid embryo transfers: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 25, 348 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Lutjen P., Trounson A., Leeton J., Findlay J., Wood C., Renou P.: The establishment and maintenance of pregnancy using in vitro fertilization and embryo donation in a patient with primary ovarian failure. Nature 1984; 307: pp. 174-175.

- Lv H. Li X. Du J. Ling X. Diao F. Lu Q. Tao S. Huang L. Chen S. Han X. Zhou K. Xu B. Liu X. Ma H. Xia Y. Shen H. Hu Z. Jin G. Guan Y. Wang X. Effect of endometrial thickness and embryo quality on live-birth rate of fresh IVF/ICSI cycles: a retrospective cohort study.Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2020; 18: 89. [CrossRef]

- 108. Mackens S., Santos-Ribeiro S., van de Vijver A., Racca A., Van Landuyt L., Tournaye H., et. al.: Frozen embryo transfer: a review on the optimal endometrial preparation and timing. Hum Reprod 2017; 32: pp. 2234-2242.

- Macklon, N. S., Geraedts, J. P., & Fauser, B. C. (2002). Conception to ongoing pregnancy: the ‘black box’ of early pregnancy loss. Human Reproduction Update, 8(4), 333-343.

- Mahajan, N., & Sharma, S. (2016). The endometrium in assisted reproductive technology: How thin is thin? Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences, 9(1), 3-8.

- Mahutte N. Hartman M. Meng L. Lanes A. Luo Z.-C. Liu K.E.Optimal endometrial thickness in fresh and frozen-thaw in vitro fertilization cycles: an analysis of live birth rates from 96,000 autologous embryo transfers.Fertil Steril. 2022; 117: 792-800. [CrossRef]

- Mahutte N., Hartman M., Meng L., Lanes A., Luo Z.C., Liu K.E.: Optimal endometrial thickness in fresh and frozen-thaw in vitro fertilization cycles: an analysis of live birth rates from 96,000 autologous embryo transfers. Fertil Steril 2022; 117: pp. 792-800.

- Margalioth, E. J., Ben-Chetrit, A., Gal, M., & Eldar-Geva, T. (2006). Investigation and treatment of repeated implantation failure following IVF-ET. Human Reproduction, 21(12), 3036-3043.

- Marquardt, R.M.; Kim, T.H.; Shin, J.-H.; Jeong, J.-W. Progesterone and Estrogen Signaling in the Endometrium: What Goes Wrong in Endometriosis? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3822. [CrossRef]

- Maryam Eftekhar, Nasim Tabibnejad, Afsar Alsadat Tabatabaie, The thin endometrium in assisted reproductive technology: An ongoing challenge, Middle East Fertility Society Journal, Volume 23, Issue 1, 2018, Pages 1-7, ISSN 1110-5690.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1110569017302947. [CrossRef]

- Marzieh Zamaniyan, Sepideh Peyvandi, Hassan Heidaryan Gorji, Siavash Moradi, Jaefar Jamal, Fatemeh Yahya Poor Aghmashhadi & Mohammad Hossein Mohammadi (2020): Effect of platelet-rich plasma on pregnancy outcomes in infertile women with recurrent implantation failure: a randomized controlled trial, Gynecological Endocrinology. [CrossRef]

- Mathyk B, Schwartz A, DeCherney A, Ata B. A critical appraisal of studies on endometrial thickness and embryo transfer outcome. Reprod Biomed Online. 2023 Oct;47(4):103259. Epub 2023 Jul 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moini A, Zafarani F, Jahangiri N, Jahanian Sadatmahalleh S, Sadeghi M, Chehrazi M, et al. (2020). The effect of vaginal sildenafil on the outcome of assisted reproductive technology cycles in patients with repeated implantation failures: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. International Journal of Fertility & Sterility, 13(4), 289-295. [CrossRef]

- Molina A., Sánchez J., Sánchez W., Vielma V.: Platelet-rich plasma as an adjuvant in the endometrial preparation of patients with refractory endometrium. JBRA Assist Reprod 2018; 22: pp. 42-48.

- Momeni M. Rahbar M.H. Kovanci E. A meta-analysis of the relationship between endometrial thickness and outcome of in vitro fertilization cycles. J Hum Reprod Sci. [CrossRef]

- Mouanness M., Ali-Bynom S., Jackman J., Seckin S., Merhi Z.: Use of intra-uterine injection of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for endometrial receptivity and thickness: a literature review of the mechanisms of action. Reprod Sci 2021; 28: pp. 1659-1670.

- Movilla P., Wang J., Chen T., Morales B., Wang J., Williams A., et. al.: Endometrial thickness measurements among Asherman syndrome patients prior to embryo transfer. Hum Reprod 2020; 35: pp. 2746-2754.

- N E van Hoogenhuijze, F Mol, J S E Laven, E R Groenewoud, M A F Traas, C A H Janssen, G Teklenburg, J P de Bruin, R H F van Oppenraaij, J W M Maas, E Moll, K Fleischer, M H A van Hooff, C H de Koning, A E P Cantineau, C B Lambalk, M Verberg, A M van Heusden, A P Manger, M M E van Rumste, L F van der Voet, Q D Pieterse, J Visser, E A Brinkhuis, J E den Hartog, M W Glas, N F Klijn, S van der Meer, M L Bandell, J C Boxmeer, J van Disseldorp, J Smeenk, M van Wely, M J C Eijkemans, H L Torrance, F J M Broekmans, Endometrial scratching in women with one failed IVF/ICSI cycle—outcomes of a randomised controlled trial (SCRaTCH), Human Reproduction, Volume 36, Issue 1, January 2021, Pages 87–98,.

- N. Lédée-Bataille, F. Olivennes, J-L. Lefaix, G. Chaouat, R. Frydman, S. Delanian, Combined treatment by pentoxifylline and tocopherol for recipient women with a thin endometrium enrolled in an oocyte donation programme, Human Reproduction, Volume 17, Issue 5, May 2002, Pages 1249–1253. [CrossRef]

- Navot D., Laufer N., Kopolovic J., Rabinowitz R., Birkenfeld A., Lewin A., et. al.: Artificially induced endometrial cycles and establishment of pregnancies in the absence of ovaries. N Engl J Med 1986; 314: pp. 806-811.

- Ng, E. H. Y., Chan, C. C. W., Tang, O. S., & Ho, P. C. (2006). The role of endometrial and subendometrial vascularity measured by three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasound in the prediction of pregnancy during IVF treatment. Human Reproduction, 21(1), 164-170.

- Noushin MA, Ashraf M, Thunga C, Singh S, Singh S, Basheer R, Ashraf R, Jayaprakasan K. A comparative evaluation of subendometrial and intrauterine platelet-rich plasma treatment for women with recurrent implantation failure. F S Sci. 2021 Aug;2(3):295-302. 2021 Mar 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noyes N., Liu H.C., Sultan K., Schattman G., Rosenwaks Z.: Endometrial thickness appears to be a significant factor in embryo implantation in in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod 1995; 10: pp. 919-922.

- Noyes, R. W., Hertig, A. T., & Rock, J. (1950). Dating the endometrial biopsy. Fertility and Sterility, 1(1), 3-25.

- Okohue J.E., Onuh S.O., Okohue J.O.: Hysteroscopy findings after two previous failed in vitro fertilisation cycles: a case for routine hysteroscopy before in vitro fertilisation?. Niger Med J 2020; 61: pp. 312-315.

- Onogi S., Ezoe K., Nishihara S., Fukuda J., Kobayashi T., Kato K.: Endometrial thickness on the day of the LH surge: an effective predictor of pregnancy outcomes after modified natural cycle-frozen blastocyst transfer. Hum Reprod Open 2020; 2020:.

- Pantos, K., Simopoulou, M., Maziotis, E., Rapani, A., Grigoriadis, S., & Tsioulou, P. (2021). Introducing intrauterine antibiotic infusion as a novel approach in effectively treating chronic endometritis and restoring reproductive dynamics: a randomized pilot study. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 15581. (SpringerLink). [CrossRef]

- Patel J.A., Patel A.J., Banker J.M., Shah S.I., Banker M.: Effect of endometrial thickness and duration of estrogen supplementation on in vitro fertilization-intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcomes in fresh ovum/embryo donation cycles. J Hum Reprod Sci 2021; 14: pp. 167-174.

- aulson RJ, Sauer MV, Lobo RA. Embryo implantation after human in vitro fertilization: importance of endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 1990 May;53(5):870-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine in collaboration with the Society for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility. Electronic address: ASRM@asrm.org; Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine in collaboration with the Society for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility. Optimizing natural fertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2017 Jan;107(1):52-58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pundir J., Pundir V., Omanwa K., Khalaf Y., El-Toukhy T.: Hysteroscopy prior to the first IVF cycle: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2014; 28: pp. 151-161.

- Quaas A.M., Gavrizi S.Z., Peck J.D., Diamond M., Legro R., Robinson R., et. al.: Endometrial thickness after ovarian stimulation with gonadotropin, clomiphene, or letrozole for unexplained infertility, and association with treatment outcomes. Fertil Steril 2021; 115: pp. 213-220.

- Quinn KE, Matson BC, Wetendorf M, Caron KM. Pinopodes: Recent advancements, current perspectives, and future directions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2020 Feb 5;501:110644. Epub 2019 Nov 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabab Alwan Taher Evaluation of the effect of sildenafil on nitric oxide secretion and improvement of endometrial receptivity in fresh ICSI cycles Vol. 12 No. 4 (2023): April 2023. [CrossRef]

- Racca, A., Santos-Ribeiro, S., Drakopoulos, P. et al. Clinical pregnancy rate for frozen embryo transfer with HRT: a randomized controlled pilot study comparing 1 week versus 2 weeks of oestradiol priming. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 21, 62 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Raine-Fenning, N. J., Campbell, B. K., & Clewes, J. S. (2004). The relationship between endometrial vascularity and endometrial thickness during the peri-implantation period in women undergoing assisted conception. Human Reproduction, 19(5), 1045-1051.

- Richard J. Paulson, M Hormonal induction of endometrial receptivity Fertil Steril 2011;96:530–5. 2011 by American Society for Reproductive Medicine. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2023.1250847/full.

- Richter, K. S., Bugge, K. R., Bromer, J. G., & Levy, M. J. (2007). Relationship between endometrial thickness and embryo implantation, based on 1,294 cycles of in vitro fertilization with transfer of two blastocyst-stage embryos. Fertility and Sterility, 87(1), 78-83.

- Roberto da Costa RP, Ferreira-Dias G, Mateus L, Korzekwa A, Andronowska A, Platek R, Skarzynski DJ. (2006). Endometrial nitric oxide production and nitric oxide synthases in the equine endometrium: Relationship with microvascular density during the estrous cycle. Domest Anim Endocrinol, 32(4), 287-302. [CrossRef]

- Rosenwaks Z.: Donor eggs: their application in modern reproductive technologies. Fertil Steril 1987; 47: pp. 895-909.

- Rubinstein M, Marazzi A, Polak de Fried E. Low-dose aspirin treatment improves ovarian responsiveness, uterine and ovarian blood flow velocity, implantation, and pregnancy rates in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization: a prospective, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled assay. Fertil Steril. 1999 May;71(5):825-9. Erratum in: Fertil Steril 1999 Oct;72(4):755. PMID: 10231040. [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.J., Kwok, Y.S.S., Nguyen, T.TT.N. et al. Autologous platelet-rich plasma improves the endometrial thickness and live birth rate in patients with recurrent implantation failure and thin endometrium. J Assist Reprod Genet 39, 1305–1312 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Salamonsen, L. A., et al. (2009). “The role of proteases in implantation.” Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, 10(3), 153-160. [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, X., & Simon, C. (2012). Endometrial receptivity: cell adhesion molecules and implantation of the human embryo. Human Reproduction Update, 18(3), 219-232.

- Sarah Lensen, Ph.D., Diana Osavlyuk, M.Sc., Sarah Armstrong, M.B., Ch.B., M.R.C.O.G., Caroline Stadelmann, M.D., Aurélie Hennes, M.Sc., Emma Napier, B.Sc., Jack Wilkinson, Ph.D., +14, and Cynthia Farquhar, F.R.A.N.Z.C.O.G., M.P.H. A Randomized Trial of Endometrial Scratching before In Vitro Fertilization January 23, 2019 N Engl J Med 2019;380:325-334. 380 NO. 4. [CrossRef]

- Sarvi F, Arabahmadi M, Alleyassin A, Aghahosseini M, Ghasemi M. Effect of Increased Endometrial Thickness and Implantation Rate by Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor on Unresponsive Thin Endometrium in Fresh In Vitro Fertilization Cycles: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2017;2017:3596079. Epub 2017 Jul 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhon L., Feuerstein J., Pan S., Overbey J., Lee J.A., Briton-Jones C., et. al.: Endometrial preparation before the transfer of single, vitrified-warmed, euploid blastocysts: does the duration of estradiol treatment influence clinical outcome?. Fertil Steril 2019; 111: pp. 1177-1185.e3.

- Senturk LM, Erel CT. Thin endometrium in assisted reproductive technology. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun;20(3):221-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0b013e328302143c. PMID: 18460935. 221-8: 20(3). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfakianoudis, K., Simopoulou, M., Nikas, Y., Rapani, A., Nitsos, N., & Pierouli, K. (2018). Efficient treatment of chronic endometritis through a novel approach of intrauterine antibiotic infusion: a case series. BMC Women’s Health, 18(1), 197. [CrossRef]

- Shakerian B. Turkgeldi E. Yildiz S. Keles I. Ata B. Endometrial thickness is not predictive for live birth after embryo transfer, even without a cutoff. Fertil Steril. 2021; 116: 130-137. [CrossRef]

- Shalma, N.M., Salamah, H.M., Alsawareah, A. et al. The efficacy of intrauterine infusion of platelet rich plasma in women undergoing assisted reproduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23, 843 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sher, G., Fisch, J. D., & Kim, H. Y. (2000). The role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in normal implantation. Fertility and Sterility, 74(4), 647-651.

- Shufaro Y., Simon A., Laufer N., Fatum M.: Thin unresponsive endometrium—a possible complication of surgical curettage compromising ART outcome. J Assist Reprod Genet 2008; 25: pp. 421-425.

- Simeonov M., Sapir O., Lande Y., Ben-Haroush A., Oron G., Shlush E., et. al.: The entire range of trigger-day endometrial thickness in fresh IVF cycles is independently correlated with live birth rate. Reprod Biomed Online 2020; 41: pp. 239-247.

- Simón C, Cano F, Valbuena D, Remohí J, Pellicer A. Clinical evidence for a detrimental effect on uterine receptivity of high serum oestradiol concentrations in high and normal responder patients. Hum Reprod. 1995 Sep;10(9):2432-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D., He, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, Z., Xia, E., Huang, X., et al. (2021). Impact of antibiotic therapy on the rate of negative test results for chronic endometritis: a prospective randomized control trial. Fertility and Sterility, 115(6), 1549-1556. [CrossRef]

- Stewart CL, Kaspar P, Brunet LJ, Bhatt H, Gadi I, Köntgen F, Abbondanzo SJ. Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature, 359. 1992. 76-79 Sep 3;359(6390):76-9.

- Strowitzki T, Germeyer A, Popovici R, von Wolff M. The human endometrium as a fertility-determining factor. Hum Reprod Update. 2006 Sep-Oct;12(5):617-30. Epub 2006 Jul 10. PMID: 16832043. [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom P.: Establishment of a successful pregnancy following in-vitro fertilization with an endometrial thickness of no more than 4 mm. Hum Reprod 1998; 13: pp. 1550-1552.

- Tang, Y.; Frisendahl, C.; Lalitkumar, P.G.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K. An Update on Experimental Therapeutic Strategies for Thin Endometrium. Endocrines 2023, 4, 672-684. [CrossRef]

- Tao Y., Wang N.: Adjuvant vaginal use of sildenafil citrate in a hormone replacement cycle improved live birth rates among 10,069 women during first frozen embryo transfers. Drug Des Devel Ther 2020; 14: pp. 5289-5297.

- Tehraninejad E., Tanha F.D., Asadi E., Kamali K., Aziminikoo E., Rezayof E.: G-CSF intrauterine for thin endometrium, and pregnancy outcome. J Family Reprod Health 2015; 9: pp. 107-112.

- Thomas Strowitzki, A. Germeyer, R. Popovici, M. von Wolff, The human endometrium as a fertility-determining factor, Human Reproduction Update, Volume 12, Issue 5, September/October 2006, Pages 617–630. [CrossRef]

- Tomic, V., Kasum, M. & Vucic, K. Impact of embryo quality and endometrial thickness on implantation in natural cycle IVF. Arch Gynecol Obstet 301, 1325–1330 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Tourgeman D.E., Slater C.C., Stanczyk F.Z., Paulson R.J.: Endocrine and clinical effects of micronized estradiol administered vaginally or orally. Fertil Steril 2001; 75: pp. 200-202.

- Urman B., Boza A., Balaban B.: Platelet-rich plasma another add-on treatment getting out of hand? How can clinicians preserve the best interest of their patients?. Hum Reprod 2019; 34: pp. 2099-2103.

- US Registry Data on Gestational Carriers, 2021=.

- Vaegter K.K., Lakic T.G., Olovsson M., Berglund L., Brodin T., Holte J.: Which factors are most predictive for live birth after in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF/ICSI) treatments? Analysis of 100 prospectively recorded variables in 8,400 IVF/ICSI single-embryo transfers. Fertil Steril 2017; 107: pp. 641-648.e2.

- Vitagliano, A., Saccardi, C., Noventa, M., Di Spiezio Sardo, A., Saccone, G., & Cicinelli, E. (2018). Effects of chronic endometritis therapy on in vitro fertilization outcome in women with repeated implantation failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertility and Sterility, 110(1), 103-112.e1. [CrossRef]

- We Weiss N.S., van Vliet M.N., Limpens J., Hompes P.G., Lambalk C.B., Mochtar M.H., et. al.: Endometrial thickness in women undergoing IUI with ovarian stimulation. How thick is too thin? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 2017; 32: pp. 1009-1018.

- Weiss N.S., van Vliet M.N., Limpens J., Hompes P.G., Lambalk C.B., Mochtar M.H., et. al.: Endometrial thickness in women undergoing IUI with ovarian stimulation. How thick is too thin? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 2017; 32: pp. 1009-1018.

- Wilcox, A. J., Baird, D. D., & Weinberg, C. R. (1999). Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine, 340(23), 1796-1799. [CrossRef]

- Wright K.P., Guibert J., Weitzen S., Davy C., Fauque P., Olivennes F.: Artificial versus stimulated cycles for endometrial preparation prior to frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Reprod Biomed Online 2006; 13: pp. 321-325.

- Wu Y., Gao X., Lu X., Xi J., Jiang S., Sun Y., et. al.: Endometrial thickness affects the outcome of in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer in normal responders after GnRH antagonist administration. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2014; 12: pp. 1-5.

- Xin Li; Yan Su; Qijun Xie; Ting Luan; Mianqiu Zhang; Xiaoyuan Ji; Yu Liu; Chun Zhao; Xiufeng Ling The Effect of Sildenafil Citrate on Poor Endometrium in Patients Undergoing Frozen-Thawed Embryo Transfer following Resection of Intrauterine Adhesions: A Retrospective Study https://karger.com/goi/article/86/3/307/154191/The-Effect-of-Sildenafil-Citrate-on-Poor Gynecol Obstet Invest (2021) 86 (3): 307–314. [CrossRef]

- Xu, B., Zhang, Q., Hao, J., Xu, D., Li, Y., & Zhang, A. (2013). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene polymorphisms in endometriosis: a meta-analysis. Molecular Biology Reports, 40(6), 4743-4751.

- Yarali H., Polat M., Mumusoglu S., Yarali I., Bozdag G.: Preparation of endometrium for frozen embryo replacement cycles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet 2016; 33: pp. 1287-1304.

- Yiran Xie, Tao Zhang, Zhengping Tian, Jiamiao Zhang, Wanxue Wang, Hong Zhang, Yong Zeng, Jianping Ou, Yihua Yang Efficacy of intrauterine perfusion of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) for Infertile women with thin endometrium: A systematic review and meta-analysisFirst Published: 12 May 2017 Volume78, Issue2. [CrossRef]

- 184. Youssef Mouhayar, Fady I. Sharara, Modern management of thin lining, Middle East Fertility Society Journal, Volume 22, Issue 1, 2017, Pages 1-12, ISSN 1110-5690. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1110569016300589). [CrossRef]

- Yuan X., Saravelos S.H., Wang Q., Xu Y., Li T.C., Zhou C.: Endometrial thickness as a predictor of pregnancy outcomes in 10787 fresh IVF-ICSI cycles. Reprod Biomed Online 2016; 33: pp. 197-205.

- Zadehmodarres S, Salehpour S, Saharkhiz N, Nazari L. Treatment of thin endometrium with autologous platelet-rich plasma: a pilot study. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2017 Feb 1;21(1):54-56. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang T., Li Z., Ren X., Huang B., Zhu G., Yang W., et. al.: Endometrial thickness as a predictor of the reproductive outcomes in fresh and frozen embryo transfer cycles: a retrospective cohort study of 1,512 IVF cycles with morphologically good-quality blastocyst. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97: pp. e9689.

- Zhang, Y., Cao, C., Du, S. et al. Estrogen Regulates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress–Mediated Apoptosis by ERK-p65 Pathway to Promote Endometrial Angiogenesis. Reprod. Sci. 28, 1216–1226 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Cao, C., Du, S. et al. Estrogen Regulates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress–Mediated Apoptosis by ERK-p65 Pathway to Promote Endometrial Angiogenesis. Reprod. Sci. 28, 1216–1226 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Fu, X., Gao, S. et al. Preparation of the endometrium for frozen embryo transfer: an update on clinical practices. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 21, 52 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Xu, H., Liu, Y., Zheng, S., Zhao, W., Wu, D., et al. (2019). Confirmation of chronic endometritis in repeated implantation failure and success outcome in IVF-ET after intrauterine delivery of the combined administration of antibiotic and dexamethasone. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 82(5), e13177. (Frontiers). [CrossRef]

- Zhao J., Zhang Q., Wang Y., Li Y.: Endometrial pattern, thickness and growth in predicting pregnancy outcome following 3319 IVF cycle. Reprod Biomed Online 2014; 29: pp. 291-298.

- Zhao, J., Zhang, Q., Li, Y., & Chen, X. (2012). Endometrial pattern, thickness and growth in predicting pregnancy outcome following 3319 IVF cycle. Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 25(3), 230-237.

- Zhu, L. J., et al. (2000). “Expression of IGFs and their receptors in human endometrium during the menstrual cycle.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 85(1), 101-107. [CrossRef]

- Zikopoulos A., Galani A., Siristatidis C., Georgiou I., Mastora E., Paraskevaidi M., et. al.: Is hysteroscopy prior to IVF associated with an increased probability of live births in patients with normal transvaginal scan findings after their first failed IVF trial?. J Clin Med 2022; 11: pp. 1217.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).