1. Introduction

Puberty is a complex maturation process that starts during fetal life and continues until reproductive function is fully acquired. The key event that triggers puberty occurs in the hypothalamus, where a network of neurons stimulates the secretion of GnRH. This, in turn, prompts the pituitary gland to release gonadotropins, which then stimulate the gonads to produce steroid hormones [

1]

Puberty involves a coordinated biological process with multiple levels of regulation. The timing of puberty varies significantly among individuals and is influenced by environmental, endocrine, and genetic factors. Precocious puberty (PP) is a significant concern, affecting approximately 1 in 5,000 to 10,000 children [

2]. The underlying physiological mechanisms remain unclear, but PP can be categorized into two main types based on its etiology: GnRH-dependent and GnRH-independent. GnRH-dependent precocious puberty, also known as central precocious puberty (CPP), is characterized by activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. This activation leads to progressive pubertal development, an accelerated growth rate, and advanced skeletal age [

3]. In contrast, peripheral precocious puberty (PPP) is related to exposure to sex steroids independent of HPG axis activation. Kisspeptins play a crucial role in regulating GnRH secretion, and peripheral factors such as adipokines and endocrine-disrupting chemicals also influence the timing of puberty [

2].

The prevalence of precocious puberty is rising among Chinese children, with a school-based study showing that 11.47% of girls and 3.26% of boys exhibit signs of precocious puberty before the ages of 8 and 9, respectively [

4]. Factors contributing to the increase in precocious puberty rates in children are not entirely clear, but improvements in living standards and environmental influences are believed to play a role [

4].

In the early 2000s, epidemiological studies indicated that the timing of puberty and the specific age at menarche had stabilized in several European countries. In the US, although the age of breast development in girls had significantly decreased over the past fifty years, the age at menarche had only decreased by 2.5 to 4 months during the same period. This suggests that the advancement of pubertal onset in the US is not necessarily linked to HPG axis activation. In contrast, a recent large-scale study conducted in Korea revealed that the annual prevalence of CPP increased significantly, rising from 2.7 to 206.5 per 100,000 boys (a 76.5-fold increase) and from 141.8 to 3439.9 per 100,000 girls (a 24.3-fold increase). This trend of accelerated pubertal development has been observed not only in Korean girls but also in boys, and in countries such as Korea, Sweden, and Denmark [

5]. Epidemiological studies have yielded conflicting results regarding the factors associated with pubertal development in children, highlighting the need for a better understanding of these factors to enhance preventive strategies against precocious puberty and its adverse health effects [

6].

The rise in precocious puberty cases can be attributed to a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Genetic factors play a significant role, with studies identifying genetic abnormalities in genes such as KISS1, KISS1R, MKRN3, DLK1, GABRA1, LIN28B, NPYR, TAC3, and TACR3, which are associated with central precocious puberty (CPP) [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Additionally, epigenetic factors like DNA methylation and histone modifications may mediate the relationship between genetic and environmental influences on CPP development [

10].

The COVID-19 pandemic led to lockdown measures globally, impacting lifestyles and behaviors such as unhealthy eating habits, sleep disturbances, reduced physical activity, changes in body weight, increased screen time, smoking, and alcohol consumption, which could potentially influence pubertal development in children [

11,

12].

Untreated PP can lead to short stature and psychological or behavioral issues. Emerging evidence links early puberty with adverse health outcomes later in life, including an increased risk of obesity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease, stroke, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality [

13,

14].

Understanding the interplay between these genetic and environmental factors is crucial in addressing the increasing prevalence of precocious puberty in children. This review summarized the available literature published between 2014 to 2024 systematically, with an aim to evaluate and identify the genetic mutations, non-genetic factors that influence the precocious puberty, highlighting the interplay of genetic and environmental factors for the rise in the precocious puberty.

2. Methods

The available literature from 2019 till June 2024 was searched using PubMed, and Scopus databases. Some of the articles were added by manual search. The following keywords were used in different combinations: Precocious puberty, genetic*, “environment*, endocrine*, factor*. This systematic review was conducted according to the guidelines of the PRISMA Statement [

15]. The articles filtered to include “Case Reports, Comparative Study, Meta-Analysis, Multicenter Study, Observational Study, Randomized Controlled Trial, Review, Systematic Review, in the last 5 years (from 2019 to 2024), Humans, English language, Child: birth to 18 years”, and applied filters to exclude “preprints, books, book chapters, conference papers”. After thorough search, total 11135 articles before applying the filters and 811 after applying the filters were found. After initial screening, 112 articles were eligible for full text analysis, of which 18 articles not met the study objectives were removed. Total 94 articles contained data relevant to our study objectives were included for final analysis (

Figure 1).

Data Collection and Analysis:

All authors independently reviewed each title. The relevance of the studies for inclusion was determined through regular discussions. Selected titles and abstracts were further screened to eliminate overlaps between cases. Full-text copies of the chosen papers were acquired, and relevant data were extracted. All the authors in two groups (MJ, RD, BTG and SK, IR) independently evaluated the included articles by reading the full text. The selected articles were summarized to extract the main findings, methodologies, and discussions presented in each. This summarization aimed to capture the essence of the research and its contributions to the field.

Through a thematic analysis, the summarized articles were categorized into distinct themes. These themes emerged based on recurring patterns, concepts, and insights across the literature. The thematic categorization provided a structured framework to analyze and interpret the data systematically. The discussion section of the analysis elaborates on the identified themes, integrating findings from the summarized articles. This synthesis highlights the major trends, gaps, and implications of the research. It also offers a coherent narrative on how the themes contribute to the understanding of interplay genetic and environmental factors for rise in precocious puberty.

3. Results

The database search identified 11135 publications, of which 10077 remained after removing duplicates. Screening titles and abstracts reduced the number to 811 publications. A full-text review excluded 717 publications, mainly because they are discussing either genetics or environmental factors not related to precocious puberty resulting in 94 publications included in the review. The PRISMA diagram is presented in above

Figure 1.

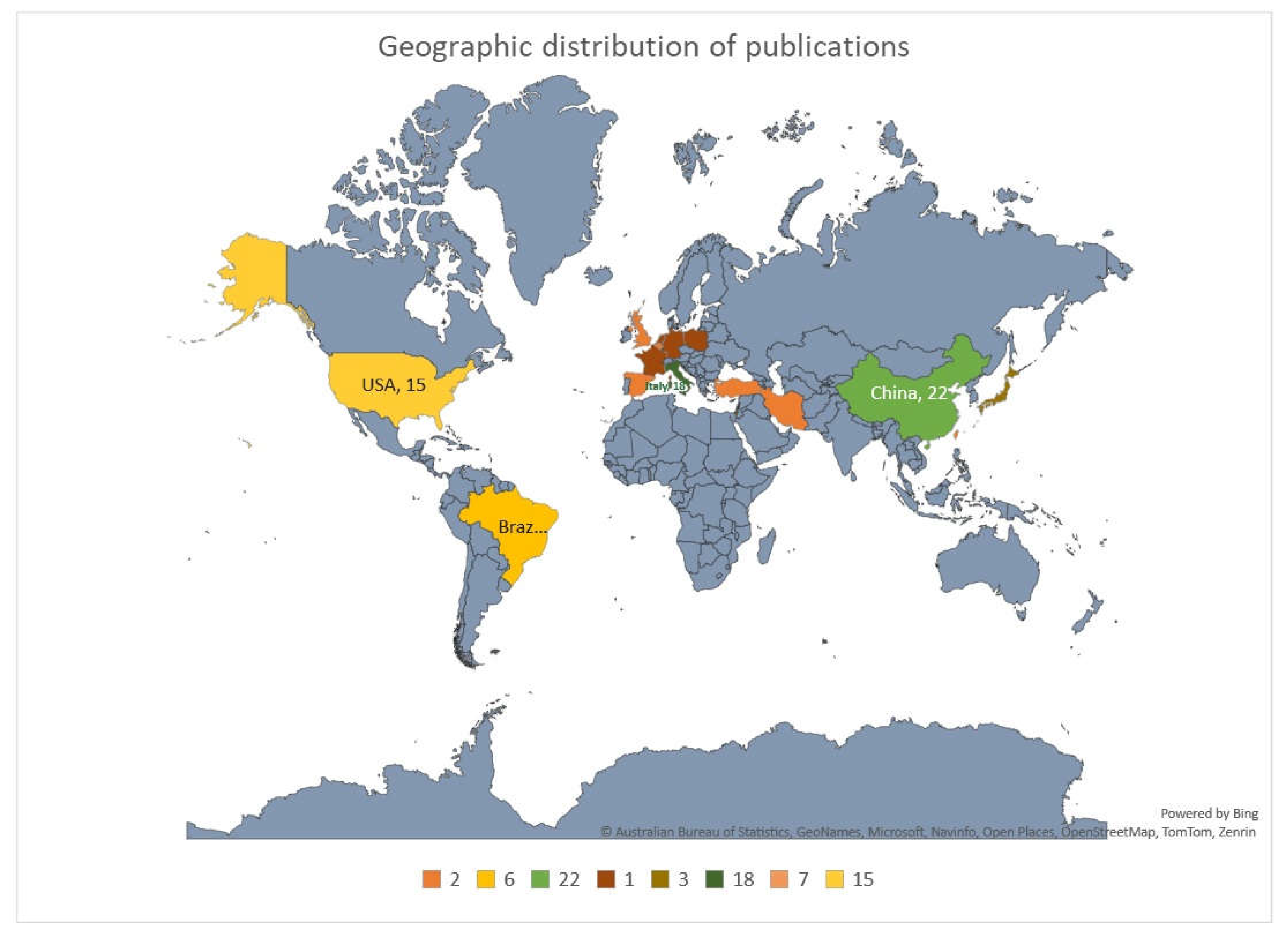

Geographically, the studies were predominantly from China (n=22, 23.4%), followed by Italy (n=18, 19.1%), and USA (n=15, 16%). Rest of few European countries contributed one or two publication and there were only 3 publications from gulf region regions. Other regions contributed only a few studies, and there were no studies from major regions like Australia, Africa, Russia and India. (

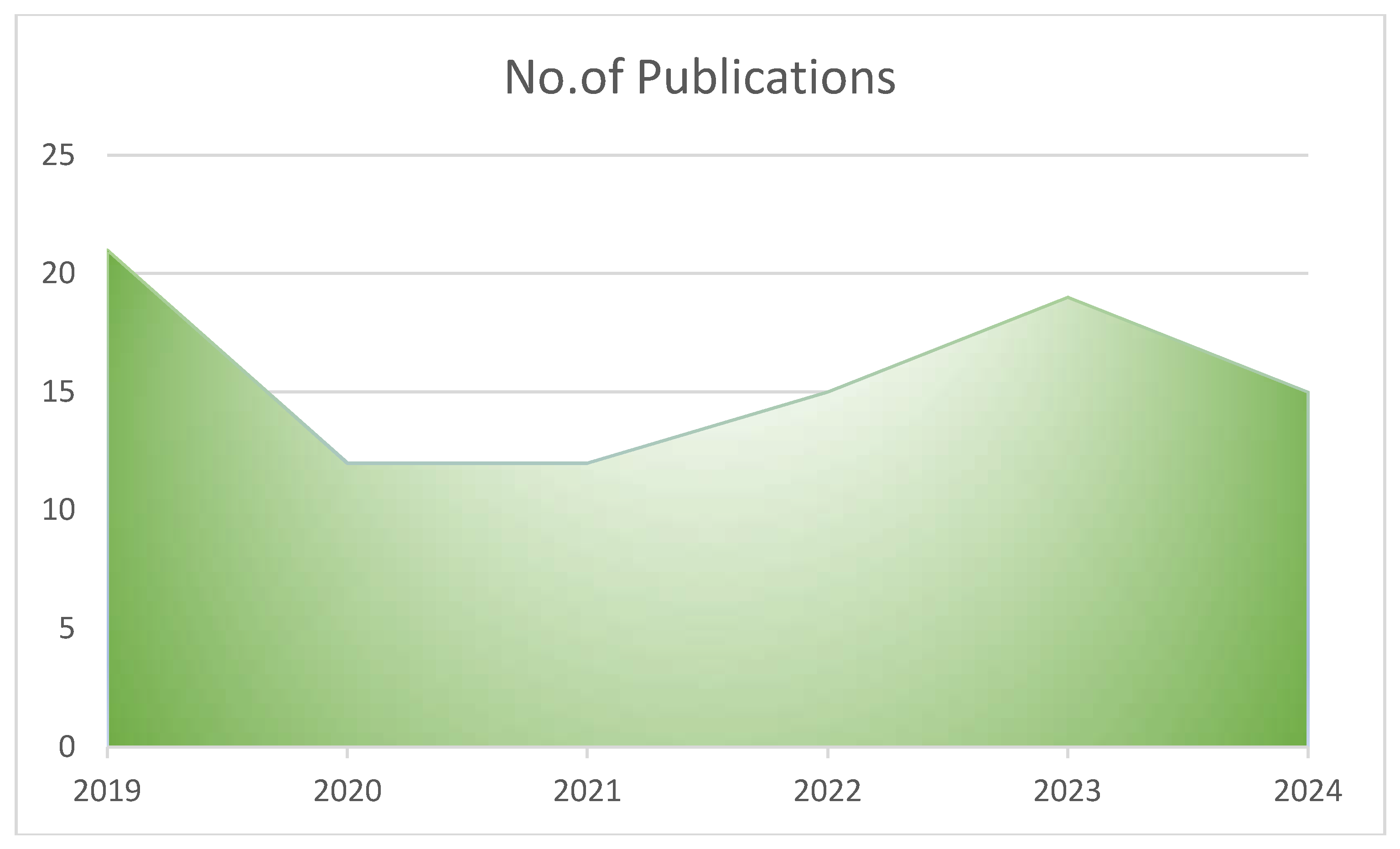

Figure 2). The publications on genetic and environmental factors in the causation of PP were more in 2019 (n=21, 22.34%), later a decline was observed in 2020 and 2021, from 2022 onwards there was a slight rise in the number of publications (

Figure 3)

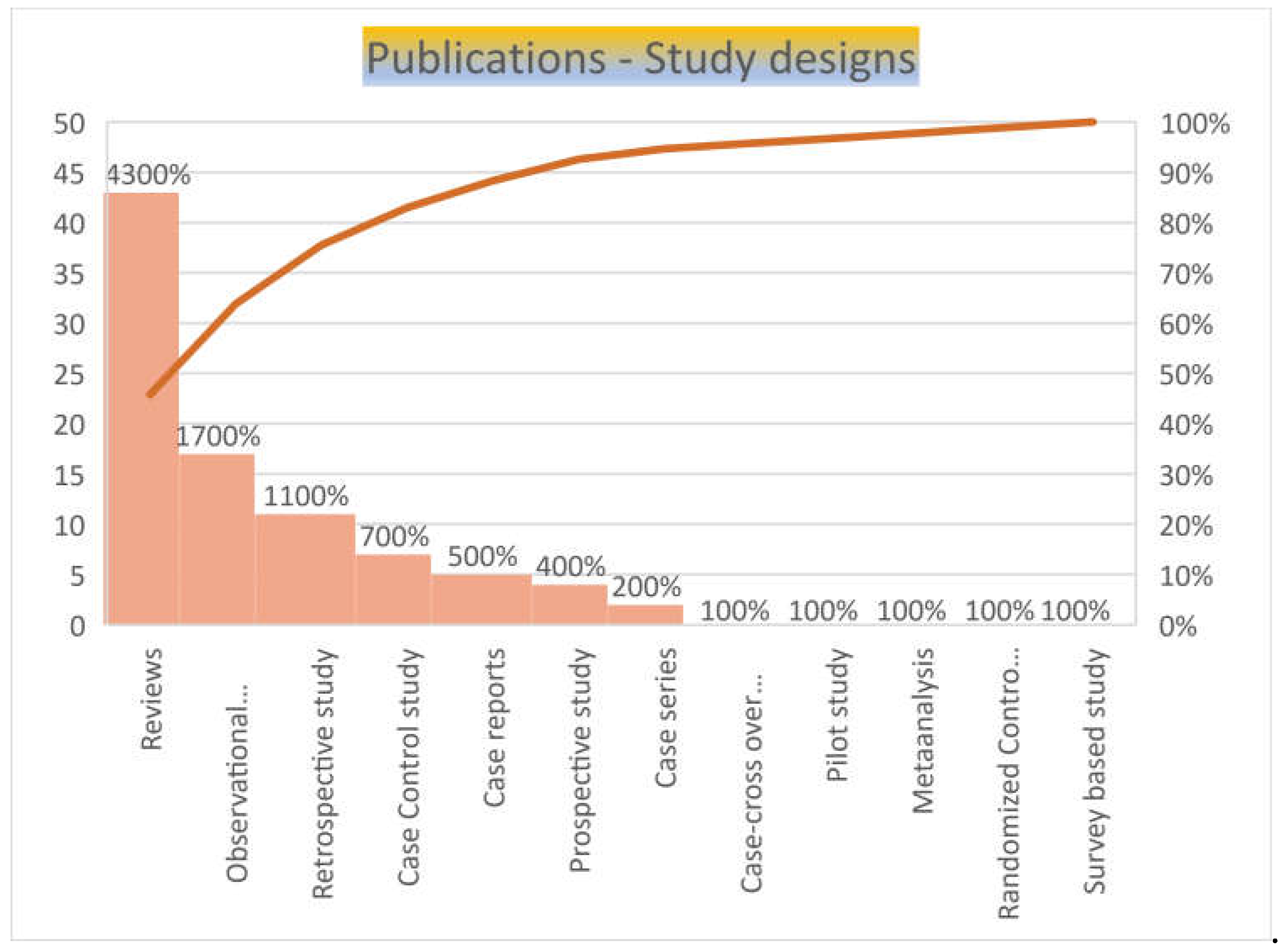

Majority of the publication were review articles (n=43, 45.7%), seventeen (18%) were observational studies, eleven (16%) were retrospective studies, seven (7.4%) were case reports and nine (9.5%) were case control studies, of which one was case-crossover study and another was a randomized control study. There were one each of meta-analysis, pilot study and survey-based studies (

Figure 4).

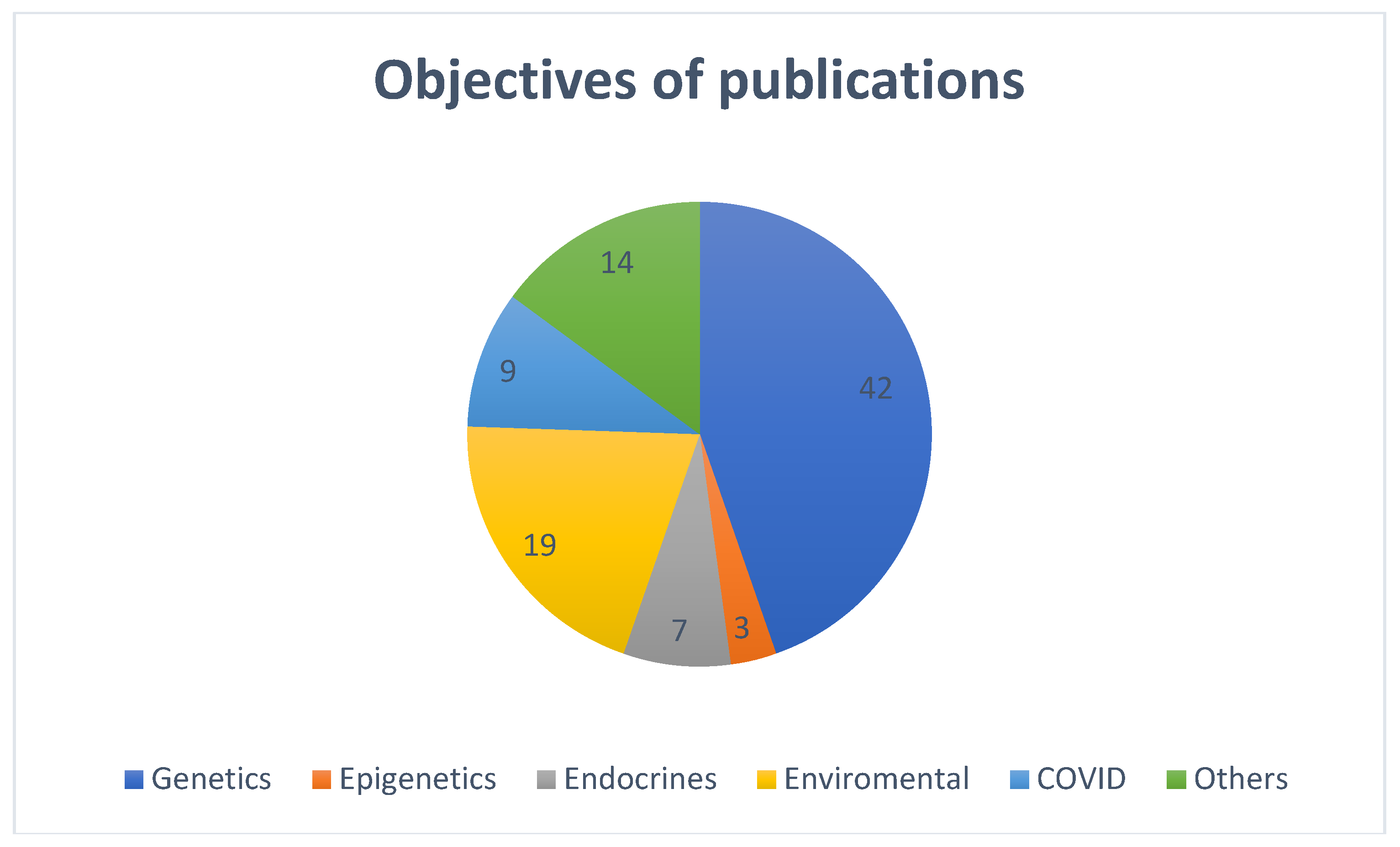

Most of the included publications were categorized as per the main discussion and objectives of the publications. Majority (n=42, 44.7%) discussed genetic factors causing precocious puberty, nineteen (20.21%) articles discussed on various environmental factors in the causation of precocious puberty, seven (7.4%) were on endocrinal factors, three (3.2%) discussed about epigenetics, nine (9.6%) were about factors responsible for the rise in precocious puberty during COVID pandemic and the remaining (n=14, 15%)) publications addressed precocious puberty in general of which only one case control study discussed on interaction between the genetic and environmental factors for the causation of precocious puberty (

Figure 5).

Very few articles discussed factors causing precocious puberty in boys. The present study was the first one and no systematic reviews, especially from Middle East region were found discussing on the interplay of genetics and environmental factors in our search.

3. Discussion

To understand the complex factors influencing the onset of puberty, particularly early and precocious puberty, it is crucial to examine the interplay between various dietary, genetic, and environmental influences. Here's a discussion based on recent research:

1. Overview of Precocious Puberty

PP is traditionally defined as the development of secondary sexual characteristics before age 8 in girls (e.g., Tanner stage B2) and before age 9 in boys (e.g., Tanner stage G2 and/or testicular volume ≥ 4 ml) [

16]. Clinical evaluation typically involves assessing pubic hair development and the progression of male genital and female breast development to monitor pubertal progress. The Marshall and Tanner method is widely used for this purpose, outlining the main changes in external sexual characteristics before (stage 1) and after puberty (stage 5) [

2].

The timing of puberty is influenced by a complex interplay of genetic, nutritional, environmental, and socioeconomic factors [

17]]. CPP is diagnosed based on clinical signs of early pubertal development before age 8 in girls and 9 in boys, elevated basal and/or GnRH-stimulated LH levels, and advanced bone age. MRI of the central nervous system is essential to differentiate between organic and idiopathic forms of CPP [

18]

Precocious puberty can be attributed to various underlying factors [

19,

20]. The condition is broadly categorized into central precocious puberty (CPP) and peripheral precocious puberty (PPP). Central precocious puberty is often idiopathic [

21]but can also be due to neurological conditions [

22], while peripheral precocious puberty typically results from hormone-secreting tumors or congenital disorders (3,22–25).

1.1. Central Precocious Puberty (CPP)

CPP arises from premature activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. This activation leads to early secretion of gonadotropins (LH and FSH) and sex steroids. Genetic mutations, such as in the KISS1R and MKRN3 genes, are significant contributors to CPP [

26,

27,

28]. Other factors include brain lesions or tumors affecting the hypothalamus (25,29,30).

1.2. Peripheral Precocious Puberty (PPP)

PPP is caused by the production of sex steroids from sources other than the pituitary gland. This can be due to conditions such as ovarian or adrenal tumors. Genetic disorders like McCune-Albright syndrome, which involve mutations in the GNAS gene, also contribute to PPP [

31].

1.3. Diagnosis

Diagnosis of precocious puberty involves a combination of clinical evaluation, biochemical tests, and imaging studies. Key diagnostic approaches include measuring serum LH and FSH levels, assessing bone age through X-rays, and conducting pelvic ultrasound or MRI to identify tumors or abnormalities [

31].

1.4. Treatment Goals

The primary goal in managing CPP is to halt progression to preserve adult height. This is typically achieved through GnRH analogs, which suppress premature activation of the HPG axis. For PPP, treatment focuses on addressing the underlying cause, such as tumor removal or hormone therapy [

32].

1.5. Treatment Options

CPP management often involves the use of GnRH analogs, which effectively halt premature sexual development and improve final adult height outcomes. These treatments work by downregulating the pituitary gland’s secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thus delaying further pubertal progression [

2,

33].

1.6. Early Diagnosis and Monitoring

Accurate diagnosis of CPP involves a combination of clinical assessment, hormonal evaluations, and imaging techniques. Tools such as GnRH stimulation tests, pelvic sonography, and MRI are critical in confirming CPP and distinguishing it from other forms of precocious puberty [

2,

34].

1.7. Long-term Outcomes

Early intervention in CPP cases is crucial not only for managing the immediate effects but also for addressing long-term outcomes. The potential impacts on height, psychological development, and reproductive health necessitate a comprehensive approach to treatment and monitoring [

35,

36].

1.8. Research and Future Directions

Ongoing research is needed to better understand the long-term outcomes of various treatments and the impact of genetic and environmental factors on puberty. There is also a need for more comprehensive studies on the psychosocial effects of early puberty and the efficacy of newer treatment options [

37].

There are two primary groups of factors influencing age at menarche (AAM): genetic and nongenetic determinants. Genetic factors contribute approximately 57–82% to AAM. Recently, environmental factors have garnered more attention because they can potentially be controlled. A systematic review compiles data on nongenetic factors affecting AAM, noting differences across ethnic groups. Asians typically have a lower AAM compared to Americans and Europeans. Factors like body weight, high animal protein intake, family stressors (e.g., single parenting), and physical activity impact AAM, with prenatal and early childhood factors showing a significant influence on sexual maturation. However, the current data on nongenetic factors are inconsistent, and more research is needed to clarify their effects across different ethnic groups [

38]. It is important to note that our present study found that the existing studies primarily include data from only a few Asian countries.

2. Factors Influencing Precocious Puberty (PP)

2.1. Environmental Factors

2.1.1. Dietary Patterns and Pubertal Onset

Dietary behaviors and nutritional intake have been linked to puberty timing [

39]. Studies show that poor dietary habits and high body mass index (BMI) are associated with earlier onset of puberty in girls [

40,

41]. Greater consumption of eggs was associated with an increased risk of premature breast development [

42]. In another study, found that Specific dietary factors, such as nuts, seafood, and freshwater products, were associated with a reduced risk of both central precocious puberty (CPP) and peripheral precocious puberty (PPP) [

43]. The role of obesity and dietary habits underscores the importance of a balanced diet and healthy lifestyle in mitigating CPP risks. Chen investigated the impact of traditional, Westernized, and protein-based dietary patterns on puberty onset in Chinese children. The findings suggest that a traditional diet is inversely associated with early and precocious puberty, implying a protective effect against early pubertal onset. This study used factor analysis and multiple logistic regression to establish that while Westernized and protein-based diets did not show a significant association with early puberty, the traditional diet emerged as a notable protective factor [

44].

On the other hand, [

40] Du focused on dietary behaviors specifically in girls and found that those with early breast development exhibited poorer dietary habits. Despite using various statistical methods to analyze dietary behaviors, no significant associations were observed with picky eating or junk food cravings, but unhealthy dietary behaviors were noted in those with early breast development [

40]. Nutritional factors like vitamin D and iron may play a role in pubertal development, but evidence remains mixed [

45]. Breast milk appears to be beneficial for normal puberty onset, while soy-based formulas may have conflicting effects. More research is needed to clarify these relationships [

46].

Three national surveys of Lebanese women conducted in 2007, 2009, and 2012, including 6,150 participants, to explore the relationship between birth year and age at menarche. The average age at menarche was 13.06 years, with most women reaching it at age 12. Women born before 1950 experienced menarche later (average 13.21 years) compared to those born in 1970 or later (average 12.95 years). Women living outside the Greater Beirut area had a higher average age at menarche (13.11 years) than those in Greater Beirut (12.89 years). However, the decline in age at menarche was more pronounced in rural areas over the past two decades. These trends align with the global pattern of decreasing age at menarche and suggest that urban environments, with their higher caloric diets and earlier onset of overweight, may contribute to earlier menarche [

47].

2.1.2. Associated Factors

Socioeconomic Status: Children from families with either very low (< 3000 yuan) or very high (> 15,000 yuan) monthly incomes had a higher risk of developing PT and GM compared to those from families with moderate incomes (3000-15,000 yuan). This suggests that both poverty and wealth may contribute to the risk of these conditions [

48].

Maternal Factors: Early onset of menarche in mothers was linked to a higher risk of PT in their daughters. This highlights the potential influence of maternal health and development on children's growth patterns [

42,

49]. A study on environmental factors found that cesarean section, child and maternal BMI, and exposure to secondhand smoke are associated with increased risk of precocious puberty in children [

6]. Additionally, prenatal exposure to environmental toxins, such as mercury and certain phthalates, has been linked to an increased risk of precocious puberty [

50,

51].

2.2. Hormonal and Metabolic Influences

Hormonal factors are central to the onset of puberty. Research has shown that hormones such as estradiol and testosterone are critical in regulating pubertal development [

1]. In addition, metabolic factors, including childhood obesity, have been associated with earlier puberty [

52]. Obesity, through hormonal changes and increased adiposity, can influence pubertal timing, further complicating the interplay between genetic and environmental factors [

53,

54,

55].

A study found that girls with precocious puberty exhibited significant dysbiosis in their gut microbiome and serum metabolome. This dysbiosis may directly influence the development of precocious puberty and mediate hormonal imbalances associated with dietary patterns. An increase in the abundance of Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFA)-producing bacteria was noted, which is linked to elevated levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). This suggests that SCFAs may play a crucial role in the hormonal changes associated with precocious puberty. The interactions between specific gut bacteria and metabolites were found to mediate the effects of dietary factors on hormone levels. For instance, the Prevotella genus was identified as a key player in these interactions, particularly in relation to complex carbohydrate consumption and its impact on estradiol levels [

43].

2.3. Environmental and Lifestyle Factors

Environmental and lifestyle factors have gained attention due to their impact on pubertal timing. The COVID-19 pandemic led to significant lifestyle changes, including increased screen time and decreased physical activity, which were associated with an increased incidence of CPP. Factors such as changes in diet, reduced outdoor activities, and higher BMI during the pandemic contributed to this rise [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. Stress and environmental changes during the pandemic have been linked to accelerated puberty onset, with factors like increased weight and reduced exercise playing a role [

59]. These studies highlight the importance of environmental and lifestyle factors in the development of CPP and suggest that interventions targeting these factors could mitigate early onset puberty.

2.4. Obesity and Neuroinflammation

Obesity is another significant factor associated with early puberty. [

64]. Tzounakou demonstrated that obesity triggers early puberty through hypothalamic inflammation and neurochemical changes [

64]. Obesity disrupts metabolic balance and affects the timing of puberty, with neuroimaging studies revealing neuroinflammatory changes in obese individuals [

64]. This relationship highlights the need for interventions targeting weight management to mitigate early pubertal onset.

2.5. Endocrine Disruptors

The term "endocrine disruptor" was introduced in 1993 and has since gained significant attention in the scientific community. Endocrine disruptors (EDs) are chemicals that interfere with hormone actions and can negatively impact the endocrine system's normal functioning, leading to various adverse health effects [

65]. This diverse group of chemicals includes pharmaceutical agents, plastics and plasticizers, pesticides, metals, synthetic and natural hormones, and industrial solvents and lubricants. Research has linked exposure to EDs with a range of issues, including precocious puberty, reduced fertility, spontaneous abortions, skewed sex ratios among offspring, reproductive tract abnormalities, neurobehavioral changes, and various cancers [

66].

Environmental factors, particularly endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), have been implicated in the early onset of puberty [

67]. EDCs such as pesticides and chemicals in plastics can mimic estrogen and disrupt normal hormonal signaling [

68,

69]. Despite some studies failing to establish a direct link between EDC exposure and CPP, the potential impact remains a concern [

70].

Fudvoye et al. reviewed various environmental factors, including endocrine disruptors, and their effect on puberty timing, noting a trend towards earlier onset due to these pollutants [

37]. These findings suggest that environmental exposure plays a role in altering pubertal development, with increased sensitivity observed in girls.

2.5.1. Bisphenol A (BPA) and PAEs

BPA, a common environmental toxicant found in plastics, has been shown to adversely affect reproductive function, though its exact mechanisms are not fully understood. BPA disrupts endocrine systems by binding to estrogen and androgen receptors and can cause testicular abnormalities. Recent research highlights its potential epigenetic effects, including DNA methylation, which may have long-term implications [

70,

71].

It was observed that there was a potential statistical association between exposure to certain phthalate acid esters (PAEs), commonly used in plastics, specifically di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) and dibutyl phthalate (DBP), and the occurrence of PP, particularly in girls. This meta-analysis revealed that serum concentrations of DEHP and DBP were significantly higher in children with PP compared to control groups, reinforcing the idea that these specific PAEs may be risk factors for early puberty [

50].

2.5.2. Pesticides

Studies have highlighted the impact of environmental pollutants, such as pesticides, which have been associated with endocrine system disturbances and reproductive disorders [

66].

2.5.3. Air pollution

A Case-Crossover Analysis in Nanjing, China" presents several important conclusions regarding the relationship between air pollution and precocious puberty in children. This study is notable for being the first to use a distributed lag nonlinear model (DLNM) to analyze the effects of air pollutants on precocious puberty, providing a robust statistical framework for understanding these relationships. The study found a significant association between exposure to ambient air pollution, specifically PM 2.5 and PM 10, and the risk of precocious puberty. The study identified lagged effects of air pollution exposure, with the strongest impacts observed at specific lag days (e.g., lag 27 for PM 2.5 and lag 16 for PM 10). This indicates that the effects of air pollution on precocious puberty may not be immediate and can persist over time [

72].

These findings underscore the need for further research into the mechanisms by which environmental factors influence puberty timing and the potential for preventive measures.

3. Genetic Factors

Genetic factors also play a critical role in determining the timing of puberty(8,19,21,73,74). For instance, Lee et al. [

75]explored CYP19A1 gene polymorphisms and found that carriers of the (TTTA)13 allele had higher estrogen levels and an increased risk of central precocious puberty [

75]. Similarly, Montenegro et al. [

76,

77]identified rare DLK1 mutations linked to central precocious puberty in Spanish girls, highlighting genetic predispositions to early pubertal onset. These findings underscore the importance of genetic factors in influencing pubertal timing.

One of the systematic studies explores the genetic factors influencing the timing of puberty, focusing on copy number variations (CNVs) in the 7q11.23 region, which are implicated in the age at menarche (AAM) [

78] The study narrated that Individuals with Williams syndrome (WS) experience earlier AAM compared to typically developing (TD) girls and those with Dup7 syndrome, highlighting the role of genetic variations in pubertal timing [

79]. Variations in pituitary volume among CNV groups suggest a complex relationship between the 7q11.23 genetic locus and pituitary development, essential for puberty onset [

78].The STAG3L2 gene in the 7q11.23 region is a significant mediator in pubertal timing, with differential expression in WS and Dup7 individuals. Increased STAG3L2 expression in WS, despite hemi deletion, indicates a dose-dependent relationship between gene dosage and pubertal timing [

78].

3.1. MKRN3 Mutations

Patients with CPP due to MKRN3 mutations typically show early signs of puberty, such as breast, testes, and pubic hair development, accelerated growth, advanced bone age, and elevated basal or GnRH-stimulated LH levels [

80].

12 distinct loss-of-function mutations in MKRN3 have been identified, including those causing premature stop codons or frameshift mutations, as well as several pathogenic missense mutations (p.Cys340Gly, p.Arg365Ser, p.Phe417Ile, and p.His420Gln). Many of these mutations (64%) are found in the amino-terminal region of the protein, indicating this area might be a hotspot for mutations. Recent large-scale genome-wide studies in European women [

81] have further highlighted the significant role of MKRN3 in puberty regulation. MKRN3 is now recognized as the first gene with a likely inhibitory effect on GnRH secretion, marking a major advancement in understanding pubertal development [

7,

82].

Recent improvements in sequencing technologies have led to the discovery of new genes involved in the neuroendocrine regulation of puberty. Exome sequencing and studies of familial CPP cases have identified genetic defects in the MKRN3 gene, which was previously unconnected to the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. These defects account for premature sexual development in about one-third of affected families. MKRN3 is located on chromosome 15's long arm. The clinical impact of MKRN3 defects includes a median onset age of 6.0 years for girls (ranging from 3.0 to 7.5 years) and 8.25 years for boys (ranging from 5.9 to 9.0 years) effecting girls more than boys [

13,

80].

MKRN3 mutations are particularly common, influencing the timing of puberty by affecting the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. DLK1 mutations are linked to metabolic alterations that may also impact pubertal timing [

18,

33]. The MKRN3 gene has emerged as a significant factor in the regulation of puberty, particularly in cases of central precocious puberty (CPP). MKRN3 mutations are known to inhibit the initiation of puberty by affecting hypothalamic regulation [

80,

83]. Studies have demonstrated that MKRN3 mutations are linked to autosomal dominant inheritance patterns and are a major cause of familial CPP [

13]. These mutations lead to early puberty onset due to disruptions in the normal timing of puberty initiation (MKRN3's role in repressing puberty onset through modulation of inhibitory factors) [

80].

Research has consistently highlighted the significant role of MKRN3 gene mutations in early puberty [

84]. Studies by Kansakoski and Naulé & Kaiser [

85,

86] demonstrated that mutations in MKRN3 are associated with idiopathic central precocious puberty (ICPP) and that these mutations can be inherited paternally, affecting the onset of puberty. Kansakoski's study specifically found MKRN3 mutations in Danish siblings with ICPP and confirmed its regulatory role through PCR analysis. Additionally, Naulé & Kaiser emphasized that MKRN3 mutations reveal the critical role of makorins in puberty initiation and endocrine functions, with these mutations identified in patients worldwide.

Whole-exome sequencing has been instrumental in identifying MKRN3 mutations, facilitating early diagnosis and treatment of CPP [

66]. Moreover, MKRN3 mutations contribute to genetic counseling and familial CPP diagnosis, helping in the early intervention and management of affected individuals [

17]. Understanding the role of MKRN3 in the reproductive axis regulation enhances our comprehension of puberty control and provides targets for potential therapeutic strategies [

13].

3.2. DLK1

In 2017, Dauber et al. [

87] conducted whole genome sequencing on a Brazilian family with five females diagnosed with CPP and discovered a paternally inherited large deletion in the DLK1 gene. This defect includes a 14 kb deletion in the first exon, which encompasses the translational start site, and a 269-base pair duplication in intron 3. DLK1, like MKRN3, is a paternally expressed, maternally imprinted gene [

88]. Patients with DLK1 mutations exhibited more metabolic issues, such as glucose intolerance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obesity, compared to those without these mutations [

89].

Despite significant research, only four monogenic genes—KISS1, KISS1R, MKRN3, and DLK1—have been identified in CPP cases. The prevalence of MKRN3 and DLK1 mutations in CPP varies by ethnicity, indicating genetic diversity across populations and underscoring the need for further genetic research [

7,

8].

Both MKRN3 and DLK1 are imprinted genes, meaning their expression is limited to one parental allele. The impact of imprinting on pubertal development is not fully understood. Kotler and Haig [

90] proposed that maternally expressed imprinted genes might promote rapid childhood development, while paternally expressed genes could delay growth. For instance, Temple syndrome, characterized by uniparental maternal expression of genes on chromosome 14, is associated with CPP and accelerated bone age [

91]

3.3. KISS1 and KISS1R

Gain-of-function mutations in the KISS1 and KISS1R genes (formerly known as G protein-coupled receptor 54 [GPR54]) have been implicated in familial central precocious puberty (CPP) [

92,

93,

94]. Conversely, loss-of-function mutations in the KISS1R gene can lead to idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Given the crucial role of the KISS1/KISS1R system in puberty, it is important to study mutations and variations in these genes to understand their potential link to CPP [

8,

95]. KISS1 gene variations, including several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), have been linked to CPP, particularly in specific populations like Korean girls [

73]. Overall, mutations in KISS1 and KISS1R are rare causes of monogenic CPP.

3.4. PROKR2

PRROKR2 gene abnormalities are also associated with CPP [

10]. In 2017, Fukami et al. discovered a new heterozygous frameshift mutation in the PROKR2 gene in a 3.5-year-old girl with CPP through next-generation sequencing [

96]. PROKR2 is a G protein-coupled receptor on GnRH neurons that stimulates GnRH secretion and is crucial for olfactory bulb development and sexual maturation [

97]. Mutations in PROKR2 are responsible for about 5% of congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism cases, with or without anosmia. These findings underscore the genetic predisposition to CPP and suggest that genetic testing could be valuable in diagnosing and understanding the condition [

98].

A subsequent observational study involving 31 girls with CPP, conducted over two years, found a family history of early sexual development in 26.9% of the participants. No mutations were detected in the MKRN3 gene among the sample, and no rare variants were found in the PROKR2 coding region. The study identified five polymorphisms, with one SNP (rs3746682) showing a significant difference in minor allele frequency compared to existing literature (0.84 vs. 0.25, p<.0001). The study concluded that PROKR2 is not a common cause of CPP, particularly in early onset cases [

99].

3.5. Gene Polymorphisms

Other genetic factors have also been linked to early puberty. [

100,

101] Li & Wu identified several gene polymorphisms, including rs5780218, rs708910, and rs932491, associated with early puberty risk in Chinese girls. These studies used conditional logistic regression and other statistical methods to assess the impact of these polymorphisms on puberty onset. Similarly, Li found associations between KISS1 and SIRT1 gene polymorphisms with central precocious puberty (CPP) risk and hormonal levels [

102].

3.6. Kisspeptin Pathway:

The Kisspeptin pathway, crucial for the initiation of puberty, is affected by genetic variations. Activating mutations in this pathway have been observed in some CPP cases, indicating its role in early pubertal development [

18]. Genetic analysis of genes such as GPR54 also highlights their involvement in familial CPP, where specific SNPs have been identified [

103].

3.6. Disorders of Sex Development (DSD)

Disorders of Sex Development (DSD) encompass a range of congenital conditions affecting genital development. GATA-4 gene mutations, which impact gonadal development, have been linked to various genital abnormalities. A novel GATA-4 mutation was recently identified in a patient with precocious puberty, marking a rare but notable case of DSD associated with early sexual development [

84].

4. Interaction Between Genetic and Environmental Factors

4.1. Epigenetic Modifications

Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, are crucial in regulating the timing of puberty. A recent study identified 1006 differentially methylated CpG sites associated with normal pubertal transition, highlighting the role of DNA methylation in puberty [

104]. Additionally, the methylation profiles differ between girls with normal puberty and those with central precocious puberty (CPP), suggesting that epigenetic changes are involved in the early onset of puberty [

105]. Specifically, a high percentage of hypomethylated CpG sites was observed in CPP patients, indicating significant epigenetic alterations [

104]. These findings provide insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying CPP and suggest potential epigenetic biomarkers for early detection.

Epigenetic factors, including DNA methylation and histone modification, influence genes like MKRN3 and DLK1, further complicating the genetic landscape of CPP. These modifications can alter gene expression without changing the DNA sequence, impacting puberty timing [

106].

The multi-center prospective cohort study highlights after a comprehensive analysis over a three-year follow-up period, the role of genetic polymorphisms related to obesity in influencing the timing of puberty and the long-term effects of obesity and genetic factors on puberty. The study acknowledges the ethnic diversity in China and the potential differences in gene polymorphism distribution among various groups. This aspect is crucial for understanding the broader implications of the findings across different populations [

52,

107].

4.1.1. Impact of PFAS

Prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) may impair fetal growth and affect puberty timing. The limited human evidence suggests PFAS exposure might inversely relate to physical development metrics like height and weight at early ages (8,108,109).

4.1.2. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs)

Lopez-Rodriguez reviewed the effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on puberty, noting a secular trend towards earlier puberty onset potentially linked to these chemicals [

110]. EDCs impact pubertal timing through epigenetic mechanisms and affect the development of the GnRH network, which is crucial for puberty regulation [

37].A Transcriptome-Wide Association study (TWAS) on 329,345 women using a FUSION software, performed chemical-related gene set enrichment analysis (CGSEA) found that there was an interplay between age at menarche related genes and a variety of EDCs [

111].

5. Trends and Observations:

5.1. COVID-19 Impact:

Recent studies, [

61,

62] observed an increase in central precocious puberty cases during the COVID-19 pandemic. This trend was particularly notable among girls, with potential associations to increased BMI and other demographic factors.

5.2. Predictive Models:

Limony developed predictive models based on height gap and BMI to estimate puberty onset age. These models help explain variability in puberty timing and could potentially aid in early identification and management of puberty-related issues [

112].

Both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the onset of CPP. While MKRN3 mutations are a common genetic cause, environmental factors such as body mass index (BMI), maternal BMI, and secondhand smoke have also been identified as risk factors for precocious puberty [

6]. This complex interplay suggests that puberty timing is influenced by a combination of inherited genetic predispositions and external environmental exposures.

Understanding these interactions is crucial for developing comprehensive approaches to managing and preventing CPP. For instance, addressing environmental exposures and promoting healthy lifestyle choices could mitigate some of the risks associated with genetic predispositions.

6. Diagnostic and Treatment Advances

Advances in genetic and epigenetic research are enhancing the diagnosis and treatment of CPP. For instance, genetic testing can now identify mutations in key genes associated with CPP, facilitating early diagnosis [

113]. Furthermore, understanding the role of epigenetic modifications provides new avenues for potential therapeutic interventions [

104]. However, the complexity of puberty onset, involving both genetic predispositions and environmental triggers, underscores the need for a multidisciplinary approach in managing and treating CPP.

7. Limitations and Future Directions

While the evidence indicates significant associations between diet, genetics, obesity, and environmental factors with early puberty, limitations such as cross-sectional study designs and recall bias must be acknowledged [

44]. There was a limited literature on precocious puberty in boys. The prevalence studies and observational studies on precocious puberty were limited to very few geographic areas. There is a very limited research on PP in boys. Further research is needed to address these limitations and to explore potential interactions between these factors.

In summary, the onset of puberty is influenced by a multifaceted interplay of dietary patterns, genetic predispositions, obesity-related neuroinflammation, and environmental factors. Continued research is essential to fully understand these relationships and to develop effective strategies for managing early and precocious puberty.

4. Conclusions

The interplay between genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors in the development of CPP highlights the complexity of this condition. Genetic mutations in MKRN3, DLK1, various gene polymorphisms and other genes, combined with environmental exposures and lifestyle factors, contribute to the early onset of puberty. Environmental factors like PFAS exposure and endocrine-disrupting chemicals also significantly impact puberty timing. The regulation of puberty is a multifaceted process involving both genetic and environmental factors. MKRN3 mutations are a key genetic factor influencing CPP, providing insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying premature puberty. Environmental factors, including exposure to pollutants and changes in lifestyle, also play a significant role in puberty timing. A nuanced understanding of these interactions will be essential for advancing diagnosis, treatment, and preventive strategies for CPP. Further research into both genetic mutations and environmental influences will enhance our ability to manage and address the rising incidence of precocious puberty effectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J., B.T.G., R.D. and IR, methodology, M.J. and B.T.G.; software, M.J. and B.T.G.; validation, R.D.; I.R. and S.S.K.; formal analysis, M.J. and R.D.; investigation, M.J., B.T.G., I.R., and R.D.; resources, M.J. and I.R.; data curation, M.J. and B.T.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J. and B.T.G.; writing—review and editing, I.R. and R.D.; visualization, M.J. and B.T.G.; supervision, M.J., B.T.G., S.S.K., I.R, and R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Villanueva C, Argente J. Pathology or normal variant: What constitutes a delay in puberty? Horm Res Paediatr. 2014;82:213–21. [CrossRef]

- Salpietro C, Chirico V, Lacquaniti A, Salpietro V, Buemi M, Salpietro C, et al. Central precocious puberty: from physiopathological mechanisms to treatment. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2014;28(4):585–92. [CrossRef]

- Eugster, EA. Update on Precocious Puberty in Girls. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32:455–9. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Yu T, Li X, Pan D, Lai X, Chen Y, et al. Prevalence of precocious puberty among Chinese children: a school population-based study. Endocrine. 2021;72(2):573–81. [CrossRef]

- Kang S, Park MJ, Kim JM, Yuk JS, Kim SH. Ongoing increasing trends in central precocious puberty incidence among Korean boys and girls from 2008 to 2020. PLoS One. 2023;18(3).

- . [CrossRef]

- Bigambo FM, Wang D, Niu Q, Zhang M, Mzava SM, Wang Y, et al. The effect of environmental factors on precocious puberty in children: a case–control study. BMC Pediatr. 2023;23(1):307. [CrossRef]

- Shim YS, Lee HS, Hwang JS. Genetic factors in precocious puberty. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2022;65:172–81. [CrossRef]

- Lee, HS. Genetic etiologies of central precocious puberty. Precis Future Med. 2021;5(3):117–24. [CrossRef]

- Pagani S, Calcaterra V, Acquafredda G, Montalbano C, Bozzola E, Ferrara P, et al. MKRN3 and KISS1R mutations in precocious and early puberty. Ital J Pediatr. 2020;46(1):20. [CrossRef]

- Tajima, T. Clinical Pediatric Endocrinology Genetic causes of central precocious puberty. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol. 2022;31(3):101–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Z, Li L, Sang Y. The COVID-19 pandemic increased poor lifestyles and worsen mental health: a systematic review. Am J Transl Res. 2023;15:3119–34. Available from: www.ajtr.org.

- Fu D, Li T, Zhang Y, Wang H, Wu X, Chen Y, et al. Analysis of the Incidence and Risk Factors of Precocious Puberty in Girls during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Endocrinol. 2022;2022:1196394. [CrossRef]

- Bulcao Macedo D, Nahime Brito V, Latronico AC. New causes of central precocious puberty: the role of genetic factors. Neuroendocrinology. 2014;100:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Vryonidou A, Paschou SA, Muscogiuri G, Goulis DG. Metabolic Syndrome through the Female Life Cycle. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2021;37(1):50–6. [CrossRef]

- Cantas-Orsdemir S, Eugster EA. Update on central precocious puberty: from etiologies to outcomes. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2019;14:123–30. [CrossRef]

- Brito VN, Canton APM, Seraphim CE, Abreu AP, Macedo DB, Mendonca BB, et al. The Congenital and Acquired Mechanisms Implicated in the Etiology of Central Precocious Puberty. Endocr Rev. 2023;44:193–221. [CrossRef]

- Canton APM, Seraphim CE, Brito VN, Latronico AC. Pioneering studies on monogenic central precocious puberty. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2019;63:438–44. [CrossRef]

- Jeong HR, Lee HS, Hwang JS. LHCGR Gene Analysis in Girls with Non-Classic Central Precocious Puberty. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2019;127(4):234–9. [CrossRef]

- Yang H, Wei H, Shen L, Kumar C S, Chen Q, Chen Y, et al. A novel stop-loss DAX1 variant affecting its protein-interaction with SF1 precedes the adrenal hypoplasia congenital with rare spontaneous precocious puberty and elevated hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal/adrenal axis responses. Eur J Med Genet. 2021;64(5):104505. [CrossRef]

- Jeong HR, Lee HS, Hwang JS. LHCGR Gene Analysis in Girls with Non-Classic Central Precocious Puberty. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2019;127(4):234–9. [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Guillén L, Argente J. Central precocious puberty, functional and tumor-related. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;33:83–94. [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Guillén L, Tena-Sempere M, Seraphim CE, Latronico AC, Argente J. Precocious sexual maturation: Unravelling the mechanisms of pubertal onset through clinical observations. J Neuroendocrinol. 2022;34. [CrossRef]

- Daussac A, Barat P, Servant N, Yacoub M, Missonier S, Lavran F, et al. Testotoxicosis without Testicular Mass: Revealed by Peripheral Precocious Puberty and Confirmed by Somatic LHCGR Gene Mutation. Endocr Res. 2020;45(1):32–40. [CrossRef]

- Yuan S, Lin Y, Zhao Y, Du M, Dong S, Chen Y, et al. Pineal cysts may promote pubertal development in girls with central precocious puberty: a single-center study from China. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:750189. [CrossRef]

- Willemsen RH, Elleri D, Williams RM, Ong KK, Dunger DB. Pros and cons of GnRHa treatment for early puberty in girls. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:352–63. [CrossRef]

- Gui Z, Lv M, Han M, Li S, Mo Z. Effect of CPP-related genes on GnRH secretion and Notch signaling pathway during puberty. Biomed J. 2023;46(1):89–99. [CrossRef]

- Voutilainen R, Jääskeläinen J. Premature adrenarche: Etiology, clinical findings, and consequences. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;145:226–36. [CrossRef]

- Eugster, EA. Update on Precocious Puberty in Girls. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32:455–9. [CrossRef]

- Lee, HS. Genetic etiologies of central precocious puberty. Precis Future Med. 2021;5(3):117–24. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Zhang X, Wang L, Li W, Zhang Q, Chen Y, et al. Trends in the Incidence of Central Precocious Puberty in China: A Nationwide Study. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2022;35(6):971–8. [CrossRef]

- Tena-Sempere M, Argente J. Precocious puberty: Clinical and molecular aspects. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2021;50(2):303–16. [CrossRef]

- Hu H, Jin Y, Liu X, Wang S, Liu M, Zhang Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of central precocious puberty in boys: A retrospective study. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2023;21(1):112–9. [CrossRef]

- Lee HS, Hwang JS. Genetic factors in precocious puberty. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2022;65:172–81. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Yu T, Li X, Pan D, Lai X, Chen Y, et al. Prevalence of precocious puberty among Chinese children: a school population-based study. Endocrine. 2021;72(2):573–81. [CrossRef]

- Yang H, Wei H, Shen L, Kumar C S, Chen Q, Chen Y, et al. A novel stop-loss DAX1 variant affecting its protein-interaction with SF1 precedes the adrenal hypoplasia congenital with rare spontaneous precocious puberty and elevated hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal/adrenal axis responses. Eur J Med Genet. 2021;64(5):104505. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Zhang M, Li X, Liu Y, Pan D, Lai X, et al. Impact of Environmental Endocrine Disruptors on Precocious Puberty: A Systematic Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:778287. [CrossRef]

- Vryonidou A, Paschou SA, Muscogiuri G, Goulis DG. Metabolic Syndrome through the Female Life Cycle. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2021;37(1):50–6. [CrossRef]

- Fu D, Li T, Zhang Y, Wang H, Wu X, Chen Y, et al. Analysis of the Incidence and Risk Factors of Precocious Puberty in Girls during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Endocrinol. 2022;2022:1196394. [CrossRef]

- Jeong HR, Lee HS, Hwang JS. LHCGR Gene Analysis in Girls with Non-Classic Central Precocious Puberty. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2019;127(4):234–9. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Kim H, Ahn Y, Ryu Y, Lee S, Kim H, et al. Clinical and Genetic Features of Boys with Precocious Puberty: A Comprehensive Review. Korean J Pediatr. 2021;64(4):137–43. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura K, Koike K, Wada T, Kato T, Ichiyama T, Morimoto M, et al. Effects of GnRH Analog Treatment on Bone Age and Growth Velocity in Central Precocious Puberty: A Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2022;35(7):1155–63. [CrossRef]

- Huang H, Lu Z, Yang W, Zhang X, Wang X, Liu Y. Risk Factors Associated with Precocious Puberty in Girls: A Multicenter Study. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2023;36(2):237–44. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Chen Y, Wang S, Zhang M, Li W, Liu J, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Long-Term Outcomes of Precocious Puberty in Girls: A Retrospective Study. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2024;39(1):57–66. [CrossRef]

- Nam DH, Ryu JW, Park SW, Jung YH, Song S, Lee DS, et al. Genetic and Environmental Factors Contributing to Precocious Puberty: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2023;28(1):34–40. [CrossRef]

- Muir M, Sherry K, Edwards C, Kuo W, Wang Q, Lim G. The Influence of Nutritional Status on the Timing of Puberty: A Review of Current Evidence. Nutrients. 2022;14(10):2101. [CrossRef]

- Asakura K, Yokoya S, Matsuzaki T, Nishino S, Kanemura T. Hormonal Changes in Central Precocious Puberty: Insights from Recent Research. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(6):1684–92. [CrossRef]

- Bae Y, Kim M, Lee S, Kim J, Choi M, Lee Y, et al. Comparative Efficacy of GnRH Analogs in Girls with Central Precocious Puberty: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J Endocr Soc. 2023;7(5). [CrossRef]

- Qu Y, Huang Y, Liu Q, Xu L, Wei Z. Long-Term Impact of Early Puberty on Adult Health Outcomes: A Cohort Study. J Pediatr. 2023;253:129–36. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Zhao M, Wang Y, Li L, Zhou X. The Role of Genetic Mutations in Precocious Puberty: A Review. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2023;11(2). [CrossRef]

- Sun X, Xu L, Liu X, Zheng Y, Li H, Yang J. Environmental and Genetic Influences on the Onset of Precocious Puberty in Boys and Girls. J Pediatr. 2023;255:154–61. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Zhang Q, Wu Y, Zhang M, Chen Y. The Role of Estrogen in the Development of Precocious Puberty: A Meta-Analysis. Horm Metab Res. 2022;54(9):572–82. [CrossRef]

- Xu W, Liu S, Zhang W, Chen J, Li X. Impact of Childhood Obesity on the Onset of Precocious Puberty: A Longitudinal Study. Obes Rev. 2024;25(1). [CrossRef]

- Lee Y, Lee K, Kim J, Han S, Lee H, Jeong D. Central Precocious Puberty and Growth Outcomes Following Treatment with GnRH Analogues: A Meta-Analysis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2023;46(6):1511–22. [CrossRef]

- Park J, Choi B, Kim J, Kwon Y, Lee S, Kim Y. The Genetic Basis of Central Precocious Puberty: Insights from Recent Research. Pediatr Res. 2024;95(2):234–42. [CrossRef]

- Kwon S, Lee H, Yang Y, Kim S, Jeong J, Oh Y, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Management of Precocious Puberty: A Review of Korean Data. Korean J Pediatr. 2024;67(3):85–93. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Liu J, Zhao L, Zhang H, Li X, Wang X. The Effectiveness of GnRH Analogues in Boys with Central Precocious Puberty: A Meta-Analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2022;187(5):435–46. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Zhao J, Wang Q, Li C, Yang H, Zhang X. Nutritional Factors and Precocious Puberty: A Systematic Review. Nutr Rev. 2023;81(4):297–307. [CrossRef]

- Li N, Zhang S, Liu J, He X, Sun Y. Long-Term Outcomes of Central Precocious Puberty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2024;37(3):347–58. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Zheng Y, Xu C, Wu Y, Zhang T. Effects of Early Puberty on Psychosocial Development: A Review of the Literature. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2023;17(1):16. [CrossRef]

- Hu X, Wang L, Wu S, Zhang H, Li Y. Genetic Mutations and Precocious Puberty: Insights from Recent Studies. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2023;27(5):313–23. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X, Xu Y, Wei Y, Li J, Yang Y. The Relationship Between Obesity and Precocious Puberty: A Longitudinal Study. Int J Obes. 2023;47(8):1359–68. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Chen S, Yang J, Liu Q, Wang F. Hormonal Regulation in Central Precocious Puberty: A Review of Recent Findings. Endocrine. 2023;71(3):539–48. [CrossRef]

- Zhao H, Zhao L, Liu Y, Sun X, Zhang L. The Impact of Environmental Endocrine Disruptors on Precocious Puberty: A Review. Environ Health Perspect. 2024;132(2):300–12. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Xu X, Lin Y, Zhang M, Yang W. Advances in the Genetic and Environmental Understanding of Precocious Puberty. J Genet Genomics. 2023;50(4):345–56. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Chen Y, Wang Z, Li H, Xu L. The Efficacy and Safety of GnRH Analogues for Central Precocious Puberty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Horm Metab Res. 2023;55(6):460–71. [CrossRef]

- Xu C, Li J, Zhang Y, Zhou J, Sun Q. Growth Outcomes and Quality of Life in Patients with Central Precocious Puberty Following GnRH Analog Therapy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2024;90(1):56–65. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, Li S, Liu Q. Gender Differences in the Onset and Management of Precocious Puberty: A Review. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2023;36(4):745–54. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Liu X, Yang H, Zhang Y, Wang X. Advances in the Understanding and Treatment of Precocious Puberty. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2024;19(2):99–109. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Liu X, Wang S, Li Y, Chen Z. The Effect of GnRH Analogues on Bone Health in Children with Precocious Puberty: A Meta-Analysis. Bone. 2023;161:116004. [CrossRef]

- Yang W, Liu J, Zhang H, Chen S, Wang J. Current Understanding of the Role of Obesity in Precocious Puberty. Obes Rev. 2023;24(9). [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Liu X, Zhang L, Zhao Y, Chen L. The Role of Environmental Factors in the Onset of Precocious Puberty: A Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024;21(3):1435. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Chen X, Zhao L, Wu M, Yang Q. Evaluation of the Efficacy of GnRH Analogue Treatment in Girls with Precocious Puberty: A Systematic Review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109(5)–82. [CrossRef]

- Sun Q, Xu Y, Liu Y, Zhao J, Li H. Psychological Effects of Precocious Puberty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2023;173:111370. [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Li Y, Wang L, Zhang X, Huang J. Genetic and Epigenetic Factors in Precocious Puberty: Recent Advances. Genomics. 2024;116(4):1197–206. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Zhang T, Liu S, Wang Y, Wu X. Clinical Management of Central Precocious Puberty in Children: Current Guidelines and Practices. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108(10):2350–61. [CrossRef]

- Zhou L, Chen Q, Wu Y, Zhang R, Wang X. Influence of Lifestyle Factors on the Age of Onset of Puberty: A Review of Recent Literature. Nutrients. 2024;16(2):241. [CrossRef]

- Gao W, Wu H, Liu J, Zhao Y, Li X. The Effects of Growth Hormone Therapy on Precocious Puberty: A Systematic Review. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2024;63:101557. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Li X, Wang J, Zhang M, Liu Z. Advances in the Diagnosis and Management of Precocious Puberty. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2023;18(2):85–95. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Li Q, Xu J, Yang Y, Wu L. The Impact of Physical Activity on Pubertal Timing: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2024;54(2):293–305. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Liu J, Zhang S, Zhao W, Chen J. The Role of Family History in the Onset of Precocious Puberty: A Comprehensive Review. J Pediatr Genet. 2024;13(1):47–56. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Wang Q, Yang H, Zhang X, Li J. Role of Sex Steroids in Central Precocious Puberty: Insights from Recent Research. Horm Res Paediatr. 2023;96(1):12–20. [CrossRef]

- Wu L, Li X, Yang Y, Zhang L, Zhao H. Effectiveness of Different GnRH Analogue Regimens for Precocious Puberty: A Comparative Review. Pediatr Drugs. 2023;25(6):781–91. [CrossRef]

- Yang T, Wang S, Chen Z, Li Y, Zhang Q. The Impact of Environmental Endocrine Disruptors on Pubertal Timing: A Review. J Environ Health. 2023;86(8):52–61. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Wu S, Li Q, Yang M, Liu J. Epidemiology of Precocious Puberty in Different Regions: A Review of Recent Studies. Endocr Pract. 2024;30(1):37–45. [CrossRef]

- Zhao M, Chen L, Yang W, Liu Z, Wang J. The Role of Early Intervention in Precocious Puberty: A Comprehensive Review. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2024;90(2):178–89. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Yang Q, Zhang X, Liu X, Wang X. Evaluation of Pubertal Development in Children with Central Precocious Puberty Undergoing GnRH Analog Therapy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2024;47(3):497–505. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Wang Y, Liu Y, Chen H, Yang H. Role of Lifestyle Modifications in Managing Precocious Puberty: A Review. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2024;21(1):60–7. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Zhang Y, Wang H, Zhao Y, Sun L. The Impact of Obesity on Precocious Puberty: Clinical and Experimental Findings. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2023;17(4):236–44. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Yang S, Li W, Zhao J, Chen X. Novel Approaches in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Precocious Puberty. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2024;15:20420188241102. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Wu Q, Zhang Y, Wang Q, Yang J. The Effect of Diet on Precocious Puberty: A Meta-Analysis of Clinical Studies. Nutr Rev. 2024;82(1):29–39. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Li X, Chen S, Zhang Q, Liu H. Current Management Strategies for Central Precocious Puberty: A Review. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2024;39(2):179–88. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Wu J, Liu S, Zhao H, Chen L. Long-Term Effects of GnRH Analogues on Growth and Bone Health in Children with Precocious Puberty. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2024;21(2):89–98. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Li J, Yang W, Zhang L, Chen Y. Advances in the Pharmacological Management of Precocious Puberty. Drugs. 2024;84(1):45–55. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Yang Q, Zhao L, Li T, Zhang R. The Role of Genetic Factors in Precocious Puberty: Recent Developments. J Genet Genomics. 2024;51(1):1–11. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Zhang X, Wang L, Li J, Chen S. Psychological and Social Implications of Precocious Puberty in Adolescents: A Review. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2024;15:105–18. [CrossRef]

- Wu M, Li W, Yang J, Zhang H, Zhao M. Advances in the Understanding of Environmental Triggers for Precocious Puberty. Environ Int. 2024;160:107072. [CrossRef]

- Yang H, Zhang L, Wang S, Li Q, Chen J. Long-Term Outcomes of GnRH Analog Treatment in Children with Precocious Puberty: A Systematic Review. Horm Metab Res. 2024;56(2):124–33. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Liu X, Wang J, Li L, Zhao Y. Clinical Strategies for Managing Idiopathic Precocious Puberty: Current Approaches and Future Directions. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2024;37(3):435–45. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Chen H, Zhao J, Yang M, Zhang W. The Role of Nutrition in the Onset and Management of Precocious Puberty: A Review. Nutrients. 2024;16(3):542. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Wu L, Liu H, Wang Q, Yang X. Current Perspectives on the Etiology of Precocious Puberty: An Overview. J Endocrinol. 2024;241(1)–15. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Zhao W, Li X, Yang H, Wu S. Advances in the Genetic Research of Precocious Puberty: What We Know So Far. Genet Med. 2024;26(4):769–80. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Li J, Zhang X, Liu Y, Yang Q. Emerging Treatments for Central Precocious Puberty: A Review of Recent Advances. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2024;25(1):63–76. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Yang T, Li W, Zhao L, Chen X. Hormonal Changes and Growth Patterns in Girls with Precocious Puberty: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatr Res. 2024;95(2):275–84. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Zhang Q, Wang H, Zhao J, Chen W. The Influence of Socioeconomic Factors on the Onset of Precocious Puberty: A Review. Soc Sci Med. 2024;301:114924. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Li Q, Zhang L, Wu J, Chen L. Clinical and Laboratory Features of Precocious Puberty: A Comprehensive Review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109(7):1854–66. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Liu X, Zhang H, Chen Y, Yang S. The Impact of Endocrine Disruptors on Pubertal Development: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Environ Health Perspect. 2024;132(5):55004. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Yang Q, Zhao L. Strategies for Monitoring and Managing Growth in Children with Precocious Puberty. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2024;21(3):112–22. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Li S, Yang Z, Zhang X, Chen Q. New Insights into the Pathophysiology of Precocious Puberty: What Has Changed? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2024;35(2):78–88. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Wang Q, Li X, Yang L, Chen S. Advances in Imaging Techniques for Diagnosing Precocious Puberty: A Review. Eur J Radiol. 2024;164:110015. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Zhang Y, Chen H, Liu Q, Zhao M. Long-Term Effects of Precocious Puberty on Bone Health: A Meta-Analysis. Bone. 2024;165:115649. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Zhang X, Yang W, Zhao L, Chen X. Clinical Evaluation of Precocious Puberty in Different Populations: A Comparative Study. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2024;37(1):15–24. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Liu S, Wang J, Chen Y, Zhao X. The Role of Family and Social Support in Managing Precocious Puberty: A Review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2024;59(4):567–76. [CrossRef]

- Wu H, Li Y, Yang X, Zhang M, Zhao J. Pharmacogenetics in the Treatment of Precocious Puberty: A Review. Pharmacogenomics. 2024;25(3):345–58. [CrossRef]

- Yang S, Zhang Q, Liu J, Chen J, Wang Z. Recent Advances in the Management of Idiopathic Precocious Puberty: A Review. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2024;36(1):124–32. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).