Submitted:

08 August 2024

Posted:

09 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

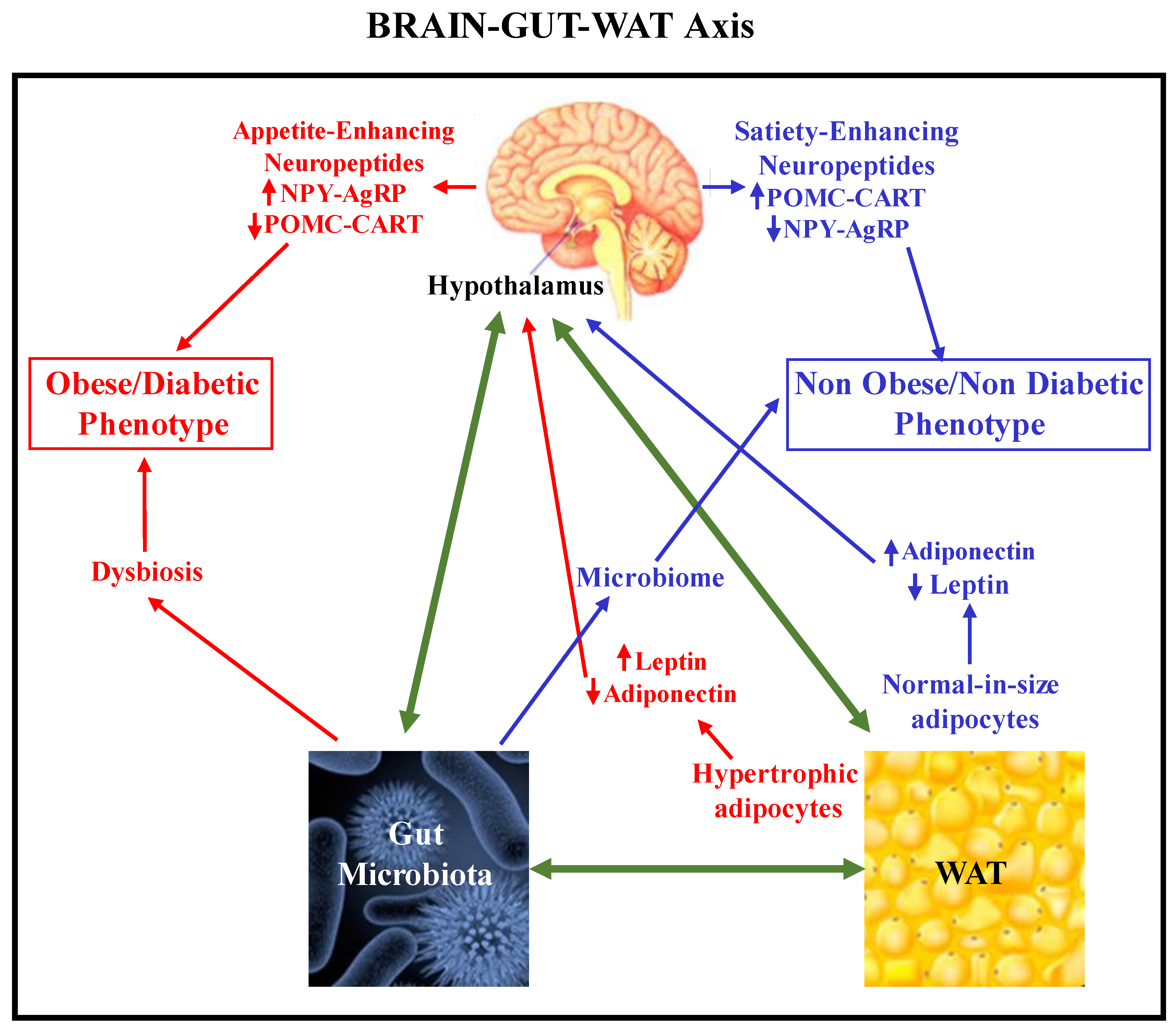

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Relevance of WAT and Gastrointestinal Tract Functions in Neuroinflammation.

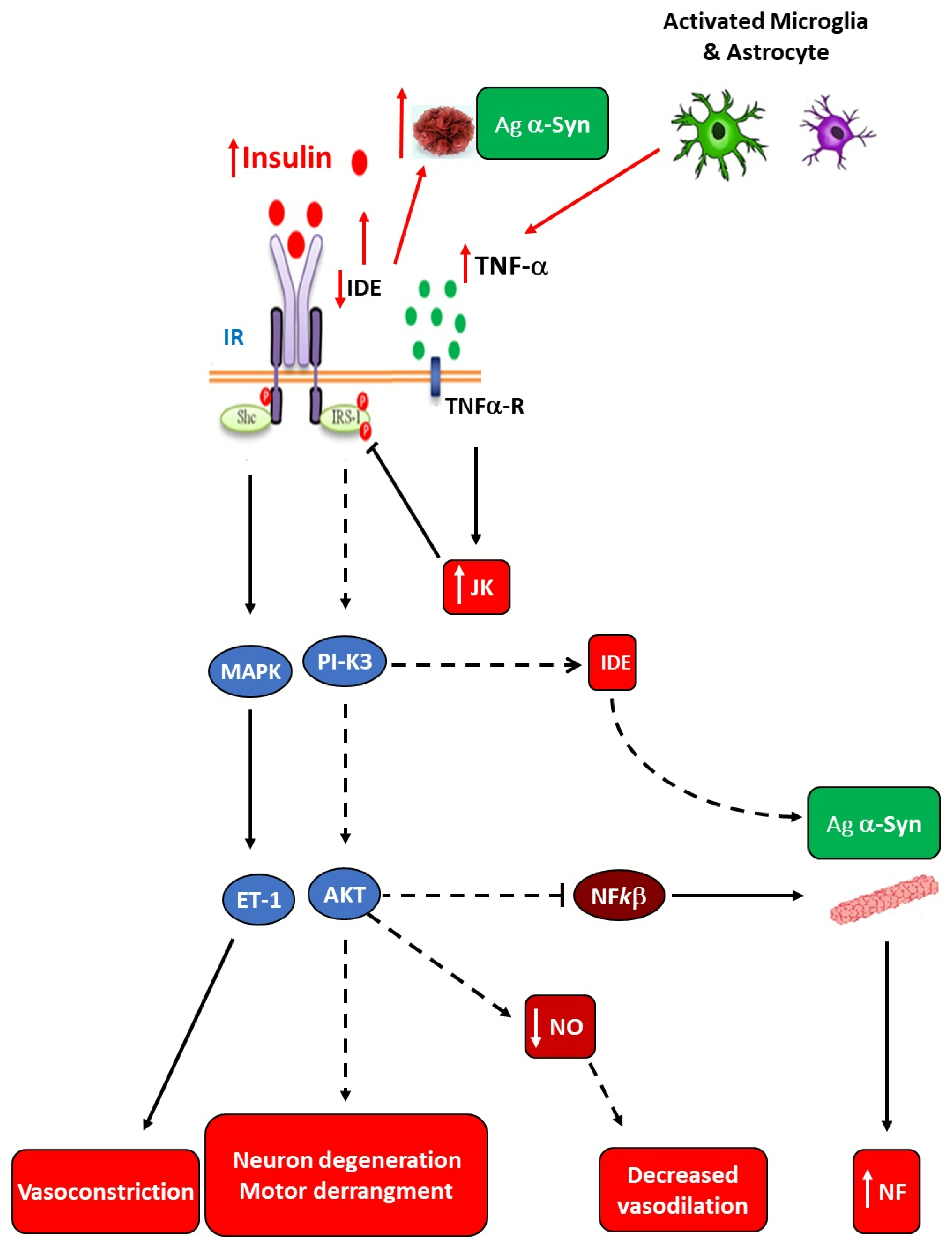

3. Hypertrophic White Adiposity-Induced Insulin Resistance (IR) as a Main Instigator of Neuroinflammation.

3.1. Sympathetic Innervation of Adipose Tissue.

3.2. Insulin-Resistant WAT Cells and Metainflammation Precede Neuroinflammation Development.

3.3. Hypothalamic-Mediated Mechanisms Involved in Neuroinflammation

3.4. Insulin Resistance-Related Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Diseases and the Role of Gut-Microbiota.

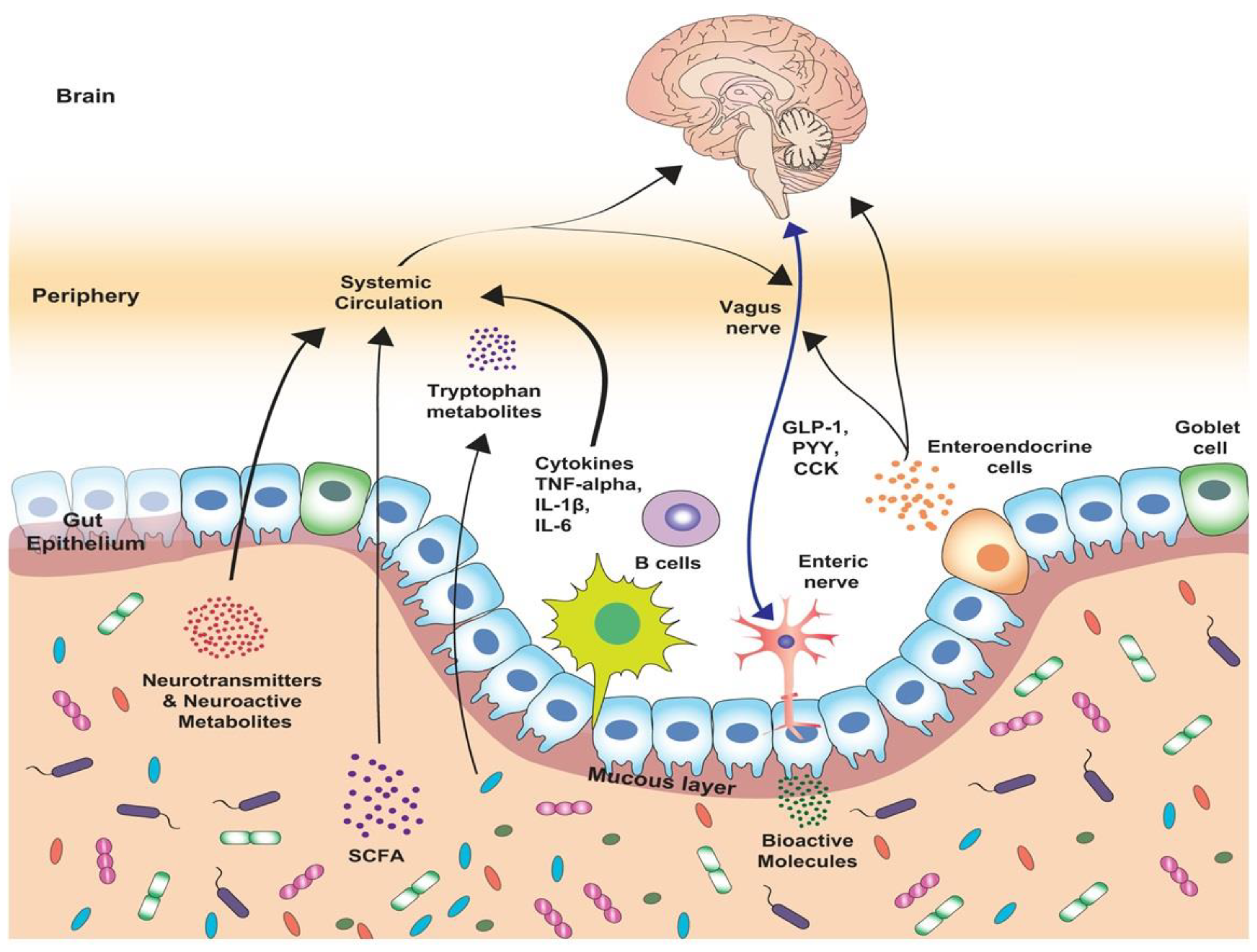

4. Gut and Neuroinflammation.

4.1. The Gut-Brain Axis: Role of the Hypothalamus.

4.2. The Nervous System and Gut: Evidence of Cell Interaction.

4.3. The Roles of the Microbiota and Barriers

5. Relation between Brain, Gut, and White Adiposity Processes.

6. Concluding Remarks.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations:

| Ab | Amyloid beta |

| Ach | Acetylcholine |

| AD | Alzheimer's Disease |

| AgRP | Aguti-related protein |

| AKT | Serine/Threonine Kinase |

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| ANS | Autonomic Nervous System |

| Arg1 | Arginase 1 |

| ASO | α-Syn-Overexpressing |

| α-Syn | α-Synuclein |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| ATRM | Adipose Tissue-Resident Macrophage |

| BBB | Blood-Brain Barrier |

| BMP2 | Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 |

| BMPR | Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor |

| CART | Cocaine-Amphetamine Related Transcript |

| CCKR | Cholecystokinin Receptor |

| CGRP | Calcitonin-Gene-Related Peptide |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CpG ODN | CpG Oligodeoxynucleotide |

| C-RP | C Reactive Protein |

| CSF1 | Colony Stimulating Factor 1 |

| CX3CL1 | Chemokine Fractalkine |

| CX3CR1 | Fractalkine Receptor 1 |

| DA | Dopamine |

| DAMP | Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern |

| DC | Dendritic Cells |

| DIO | Diet-Induced Obesity |

| DOPA | Dihydroxy Phenyl Alanine |

| ENS | Enteric Nervous System |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| FFA | Free Fatty Acid |

| FFAR | Free Fatty Acid Receptor |

| GBA | Gut-Brain axis |

| GC | Glucocorticoid |

| GLU | Glucose |

| GM | Gut Microbiota |

| GR | Glucocorticoid Receptor |

| GRE | Glucocorticoid Response Element |

| GSK3b | Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3b |

| GVB | Gut-Vascular Barrier |

| HD | Huntington Disease |

| HFD | High Fat Diet |

| HPA | Hypotalamo-Pituitary-Adrenal |

| IAPP | Islet Amyloid Polypeptide |

| IAPP | Islet Amyloid Polypeptide |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| IDE | Insulin-Degrading Enzyme |

| IFN- | Interferon-gamma |

| IKKβ | Inhibitory Kappa beta Kinase |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| ILC | Innate Lymphoid Cell |

| Ins | Insulin |

| IR | Insulin Resistance |

| IRS-1 | Insulin Receptor Susbtrate-1 |

| JAK-STAT | Janus Kinase-Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| L2-3 | Spinal Lumbar Segments 2 & 3 |

| LEP-R | Leptin Receptor |

| LPM | Lamina Propria Macrophage |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAOA | Monoamine Oxidase A |

| microRNA | micro Ribonucleic Acid |

| MM | Muscularis Macrophage |

| MMP | Matrix Metalloproteinases |

| MR | Mineralocorticoid Receptor |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| ND | Neurodegenerative Disease |

| NE | Norepinephrine |

| NF | Neuroinflammation |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor-Kappa B |

| NGF | Nerve Growth Factor |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NPY | Neuropeptide Y |

| Ob-Rb | Leptin Receptor form b |

| OS | Oxidative Stress |

| PAI-1 | Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor type 1 |

| PAMP | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Pattern |

| PD | Parkinson's Disease |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase |

| PNS | Parasympathetic Nervous System |

| POMC | Pro-opiomelanocortin |

| PRR | Pattern-Recognition Receptors |

| RA | Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| Ramp1 | Receptor Activity Modifying Protein 1 |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Substances |

| SAM | Sympathetic Neuro-Associated Macrophage |

| SCFA | Short Chain Fatty Acid |

| SLC6A2 | Solute Carrier Family 6 Member-2 |

| SNS | Sympathetic Nervous System |

| SOCS3 | Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 3 |

| SPF | Specific Pathogen Free |

| T13 | Spinal Thoracic Segment 13 |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| Th | T Helper Lymphocytes |

| TLR7 | Toll-Like Receptor |

| TNF- | Tumor Necrosis-alpha |

| TOX01 | Forkhead Box Protein 01 |

| Trp | Tryptophan |

| UCP-1 | Uncoupling Protein-1 |

| VIP | Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide |

| WAT | White Adipose Tissue |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Niranjan, R. Recent advances in the mechanisms of neuroinflammation and their roles in neurodegeneration. Neurochem. Int. 2018, 120, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyman, M.; Lloyd, D.G.; Ji, X.; Vizcaychipi, M.P.; Ma, D. Neuroinflammation: The role and consequences. J. Neuroscience. Research. 2014, 79, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhramanyam, C.S.; Wang, C.; Hu, Q.; Dheen, S.T. Microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2019, 94, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R.C.; Chiu, K.; Ho, Y.S.; So, K.F. Modulation of neuroimmune responses on glia in the central nervous system: implication in therapeutic intervention against neuroinflammation. J. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2009, 6, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A.; McQuillan, K.; Deighan, B.F.; O'Reilly, J.A.; Downer, E.J.; Murphy, A.C.; Watson, M.; Piazza, A.; O'Connell, F.; Griffin, R.; et al. Decreased neuronal CD200 expression in IL-4-deficient mice results in increased neuroinflammation in response to lipopolysaccharide. J. Brain. Behavior. Immunity. 2009, 23, 1020–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessis, A.; Biber, K.; Bilbo, S.; Blurton-Jones, M.; Boddeke, E.; Brites, D.; et al. Microglia states and nomenclature: a field at its crossroads. Neuron. 2022, 110, 3458–3483. [Google Scholar]

- Paolicelli, R.C.; Sierra, A.; Stevens, B.; Tremblay, M.E.; Aguzzi, A.; Ajami, B.; Amit, I.; Audinat, E.; Bechmann, I.; Bennett, M.; et al. Microglia states and nomenclature: a field at its crossroads. Neuron. 2022, 110, 3458–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazoukis, G.; Stavrakis, S.; Armoundas, A.A. Vagus Nerve Stimulation and Inflammation in Cardiovascular Disease: A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 2, e030539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z. , Wang, X., Feng, S.; Xie, C., Xing, Y., Guo, L., et al. A review of neuroendocrine immune system abnormalities in IBS based on the brain–gut axis and research progress of acupuncture intervention. Front Neurosci. 2023, 17, 934341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S.S.; Huh, J.Y.; Hwang, I.J.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, J.B. Adipose Tissue Remodeling: its Role in energy Metabolism and Metabolic Disorders. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelario-Jalil, E.; Dijkhuizen, R.M.; Magnus, T. ; Neuroinflammation, Stroke, Blood-Brain Barrier: Dysfunction, and Imaging Modalities. Stroke. 2022, 53, 1473–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Ruiz, R.; Fuentes-Mera, L.; Camacho, A. Central Modulation of Neuroinflammation by Neuropeptides and Energy-Sensing Hormones during Obesity. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 7949582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocchi, A.; Carloni, S.; Ravenda, P.S.V.; Bertalot, G.; Spadoni, I.; Lo Cascio, A.; Gandini, S.; Lizier, M.; Braga, D.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Gut vascular barrier impairment leads to intestinal bacteria dissemination and colorectal cancer metastasis to liver. Cancer Cell. 2021, 39, 708–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carloni, S.; Bertocchi, A.; Mancinelli, S.; Bellini, M.; Erreni, M.; Borreca, A.; Braga, D.; Giugliano, S.; Mozzarelli, A.M.; Manganaro, D.; et al. Identification of a choroid plexus vascular barrier closing during intestinal inflammation. Science. 2021, 374, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehervari, Z. A gut vascular barrier. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilski, J.; Mazur-Bialy, A.; Wojcik, D.; Surmiak, M.; Magierowski, M. , Sliwowski. Z., Pajdo, R.; Kwiecien, S.; Danielak, A.; Ptak-Belowska, A.; et al. Role of Obesity, Mesenteric Adipose Tissue, and Adipokines in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Biomolecules. 2019; 9, 780. [Google Scholar]

- Rautmann, A.W.; de La Serre, C.B. Microbiota's Role in Diet-Driven Alterations in Food Intake: Satiety, Energy Balance, and Reward. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartor, R.B. Mechanisms of disease: Pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 3, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Więckowska-Gacek, A.; Mietelska-Porowska, A.; Wydrych, M.; Wojda, U. Western diet as a trigger of Alzheimer's disease: From metabolic syndrome and systemic inflammation to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2021, 70, 101397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinedi, E.; Cardinali, D.P. Neuroendocrine-Metabolic Dysfunction and Sleep Disturbances in Neurodegenerative Disorders: Focus on Alzheimer's Disease and Melatonin. Neuroendocrinology. 2019, 108, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordovas-Montanes, J.; Rakoff-Nahoum, S.; Huang, S.; Riol-Blanco, L.; Barreiro, O.; von Andrian, U.H. The Regulation of Immunological Processes by Peripheral Neurons in Homeostasis and Disease. Trends. Immunol. 2015, 36, 578–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho-Silva, C.; Cardoso, F.; Veiga-Fernandes, H. . Neuro-Immune Cell Units: A New Paradigm in Physiology. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 26, 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, A.J.; Beresford, L.J.; Bell, E.B.; Miyan, J.A. . Mobilisation of specific T cells from lymph nodes in contact sensitivity requires substance P. J. Neuroimmunol. 2005, 164, 115–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga-Fernandes, H.; Pachnis, V. Neuroimmune regulation during intestinal development and homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furness, J.B.; Kunze, W.A.; Clerc, N. Nutrient tasting and signaling mechanisms in the gut. II. The intestine as a sensory organ: neural, endocrine, and immune responses. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 277, G922–G928. [Google Scholar]

- Neunlist, M.; Van Landeghem, L.; Mahé, M.M.; Derkinderen, P.; des Varannes, S.B.; Rolli-Derkinderen, M. The digestive neuronal-glial-epithelial unit: a new actor in gut health and disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 10, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.A.; Chung, Y.C.; Pan, S.T.; Shen, M.Y.; Hou, Y.C.; Peng, S.J.; Pasricha, P.J.; Tang, S.C. 3-D imaging, illustration, and quantitation of enteric glial network in transparent human colon mucosa. SC. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2013, 25, e324–e338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisel, J.D.; Panda, O.; Mahanti, P.; Schroeder, F.C.; Kim, D.H. Chemosensation of bacterial secondary metabolites modulates neuroendocrine signaling and behavior of C. elegans. Cell. 2014, 159, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhijani, K.; Alexander, B.; Rao, D.; Petraki, S.; Herboso, L.; Kukar, K.; Batool, I.; Wachner, S.; Gold, K.S.; Wong, C.; et al. Regulation of Drosophila hematopoietic sites by Activin-β from active sensory neurons. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Pirzgalska, R.M.; Pereira, M.M.; Kubasova, N.; Barateiro, A.; Seixas, E.; Lu, Y.H.; Kozlova, A.; Voss, H.; Martins, G.G.; et al. Sympathetic neuro-adipose connections mediate leptin-driven lipolysis. Cell. 2015, 163, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, R.B.; Dark, J. Sensory innervation of white adipose tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1987, 253, R942–R944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.K.; Schwartz, G.J.; Bartness, T.J. Anterograde transneuronal viral tract tracing reveals central sensory circuits from white adipose tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009, 296, R501–R511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.T.; Schwartz, G.J.; Nguyen, N.L.T.; Mendez, J.M.; Ryu, V.; Bartness, T.J. Leptin-sensitive sensory nerves innervate white fat. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 304, E1338–E1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garretson, J.T.; Szymanski, L.A.; Schwartz, G.J.; Xue, B.; Ryu, V.; Bartness, T.J. Lipolysis sensation by white fat afferent nerves triggers brown fat thermogenesis. Mol. Metab. 2016, 5, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youngstrom, T.G.; Bartness, T.J. Catecholaminergic innervation of white adipose tissue in Siberian hamsters. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1995, 268, R744–R751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartness, T.J.; Liu, Y.; Shrestha, Y.B.; Ryu, V. Neural innervation of white adipose tissue and the control of lipolysis. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 35, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamshad, M.; Aoki, V.T.; Adkison, M.G.; Warren, W.S.; Bartness, T.J. Central nervous system origins of the sympathetic nervous system outflow to white adipose tissue. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 275, R291–R299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, R.B.S. Denervation as a tool for testing sympathetic control of white adipose tissue. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 190, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Song, C.K.; Giordano, A.; Cinti, S.; Bartness, T.J. Sensory or sympathetic white adipose tissue denervation differentially affects depot growth and cellularity. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005, 288, R1028–R1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, M.T.; Bartness, T.J. Sympathetic but not sensory denervation stimulates white adipocyte proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006, 291, R1630–R1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herradon, G.; Ramos-Alvarez, M.P.; \Gramage, E. Connecting Metainflammation and Neuroinflammation Through the PTN-MK-RPTPβ/ζ Axis: Relevance in Therapeutic Development Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 377. [Google Scholar]

- Reaven, G.M. The insulin resistance syndrome. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2003, 5, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, J.D. What if Minkowski had been ageusic? Diabetes. 1992, 41, 826–834. [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak, S.E.; Gee, L.L.; Wachtel, M.S.; Frezza, E.E. Adipose tissue: the new endocrine organ? Dig. Dis. Sci. 2009, 54, 1847–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelliot, C.; Vidal Puig, A.J. Lipotoxicity, an imbalance between lipogenesis de novo and fatty acid-oxidation. Int. J. Obesity. 2004, 28, S22–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olefsky, J.M. Decreased insulin binding to adipocytes and circulating monocytes from obese subjects. J. Clin. Invest. 1976, 57, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, J.M.; Ciaraldi, T.P.; Brady, D.; Olefsky, J.M. Decreased activation rate of insulin-stimulated glucose transport in adipocytes from obese subjects. Diabetes. 1989, 38, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnie, J.A.; Smith, D.G.; Mavris-Vavayannis, M. Effects of insulin on lipolysis and lipogenesis in adipocytes from genetically obese (ob/ob) mice. Biochem. J. 1979, 184, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocai, A.; Lam, T.K.; Gutierrez-Juarez, R.; Obici, S.; Schwartz, G.J.; Bryan, J.; Aguilar-Bryan, L.; Rossetti, L. . Hypothalamic K(ATP) channels control hepatic glucose production. Nature. 2005, 434, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, T.J.; Habener, J.F. The adipoinsular axis: effects of leptin on pancreatic beta-cells. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 278, E1–E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frühbeck, G.; Gómez-Ambrosi, J.; Muruzábal, F.J.; Burrell, M.A. The adipocyte: a model for integration of endocrine and metabolic signaling in energy metabolism regulation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 280, E827–E84747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, A.S.; Davis, S.M.; Bates, S.H.; Myers, M.G. Jr. Activation of downstream signals by the long form of the leptin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 14563–14572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, A.; Murakami, T.; Otani, S.; Kuwajima, M.; Shima, K. Leptin affects pancreatic endocrine functions through the sympathetic nervous system. Endocrinology. 1998, 139, 3863–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huan, J.N.; Li, J.; Han, Y.; Chen, K.; Wu, N.; Zhao, A.Z. Adipocyte-selective reduction of the leptin receptors induced by antisense RNA leads to increased adiposity, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 45638–45650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, P.A.; Saghizadeh, M.; Ong, J.M.; Bosch, R.J.; Deem, R.; Simsolo, R.B. The expression of tumor necrosis factor in human adipose tissue. Regulation by obesity, weight loss, and relationship to lipoprotein lipase. J. Clin. Invest. 1995, 95, 2111–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fain, J.N.; Madan, A.K.; Hiler, M.L.; Cheema, P.; Bahouth, S.W. Comparison of the release of adipokines by adipose tissue, adipose tissue matrix, and adipocytes from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissues of obese humans. Endocrinology. 2004, 145, 2273–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, Y.; Kihara, S.; Funahashi, T.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Libby, P. Adiponectin: A key adipocytokine in metabolic syndrome. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 2006, 110, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niswender, K.D.; Schwartz, M.W. Insulin and leptin revisited: adiposity signals with overlapping physiological and intracellular signaling capabilities. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2003, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anubhuti Arora, S. Leptin and its metabolic interactions: an update. Diabetes. Obes. Metab. 2008, 10, 973–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frühbeck, G. Intracellular signalling pathways activated by leptin. Biochem. J. 2006, 393, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyama, N.; Geerts, A.; Reynaert, H. Neural connections between the hypothalamus and the liver. Anat. Rec. A. Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol. 2004, 280, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flak, J.N.; Myers, M.G. Jr. CNS Mechanisms of Leptin Action. Mol. Endocrinol. 2016, 30, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, R.H. Minireview: Weapons of lean body mass destruction: The role of ectopic lipids in the metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology. 2003, 144, 5159–5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morioka, T.; Asilmaz, E.; Hu, J.; Dishinger, J.F.; Kurpad, A.J.; Elias, C.F.; et al. Disruption of leptin receptor expression in the pancreas directly affects beta cell growth and function in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 117, 2860–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timper, K.; Bruning, J.C. Hypothalamic circuits regulating appetite and energy homeostasis: Pathways to obesity. Dis. Model. Mech. 2017, 10, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaler, J.P.; Yi, C.X.; Schur, E.A.; Guyenet, S.J.; Hwang, B.H.; Dietrich, M.O.; et al. Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 2012, 122, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velloso, L.A.; Schwartz, M.W. Altered hypothalamic function in diet-induced obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 1455–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergen, H.T.; Mizuno, T.; Taylor, J.; Mobbs, C.V. Resistance to diet-induced obesity is associated with increased proopiomelanocortin mRNA and decreased neuropeptide Y mRNA in the hypothalamus. Brain. Res. 1999, 851, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, D.I.; Lemus, M.B.; Kua, E.; Andrews, Z.B. Diet-induced obesity attenuates fasting-induced hyperphagia. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2011, 23, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanski, M.; Degasperi, G.; Coope, A.; Morari, J.; Denis, R.; Cintra, D.E.; Tsukumo, D.M.; Anhe, G.; Amaral, M.E.; Takahashi, H.K.; et al. Saturated fatty acids produce an inflammatory response predominantly through the activation of TLR4 signaling in hypothalamus: Implications for the pathogenesis of obesity. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, H.; Karin, M.; Bai, H.; Cai, D. Hypothalamic IKKbeta/NF-kappaB and ER stress link overnutrition to energy imbalance and obesity. Cell. 2008, 135, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, N.F.; Gaspar, J.M.; Lima-Junior, J.C.; Donato, J., Jr.; Velloso, L.A.; Araujo, E.P. TGF-beta1 down-regulation in the mediobasal hypothalamus attenuates hypothalamic inflammation and protects against diet-induced obesity. Metabolism. 2018, 85, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.; Kim, K.K.; Park, B.S.; Kim, D.H.; Jeong, B.; Kang, D.; Lee, T.H.; Park, J.W.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, B.J. Function of astrocyte MyD88 in high-fat-diet-induced hypothalamic inflammation. J. Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspar, J.M.; Mendes, N.F.; Correa-da-Silva, F.; Lima-Junior, J.C.; Gaspar, R.C.; Ropelle, E.R.; Araujo, E.P.; Carvalho, H.M.; Velloso, L.A. Downregulation of HIF complex in the hypothalamus exacerbates diet-induced obesity. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2018, 73, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, C.T.; Araujo, E.P.; Bordin, S.; Ashimine, R.; Zollner, R.L.; Boschero, A.C.; Saad, M.J.; Velloso, L.A. Consumption of a fat-rich diet activates a proinflammatory response and induces insulin resistance in the hypothalamus. Endocrinology. 2005, 146, 4192–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paula, G.C.; Brunetta, H.S.; Engel, D.F.; Gaspar, J.M.; Velloso, L.A.; Engblom, D.; de Oliveira, J.; de Bem, A.F. Hippocampal Function Is Impaired by a Short-Term High-Fat Diet in Mice: Increased Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability and Neuroinflammation as Triggering Events. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 734158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, T.M.; Konanur, V.R.; Taing, L.; Usui, R.; Kayser, B.D.; Goran, M.I.; Kanoski, S.E. Effects of sucrose and high fructose corn syrup consumption on spatial memory function and hippocampal neuroinflammation in adolescent rats. Hippocampus. 2015, 25, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carraro, R.S.; Souza, G.F.; Solon, C.; Razolli, D.S.; Chausse, B.; Barbizan, R.; Victorio, S.C.; Velloso, L.A. Hypothalamic mitochondrial abnormalities occur downstream of inflammation in diet-induced obesity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 460, 238–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardzinski, E.K.; Kistenmacher, A.; Melchert, U.H.; Jauch-Chara, K.; Oltmanns, K.M. Impaired brain energy gain upon a glucose load in obesity. Metabolism. 2018, 85, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdearcos, M.; Douglass, J.D.; Robblee, M.M.; Dorfman, M.D.; Stifler, D.R.; Bennett, M.L.; Gerritse, I.; Fasnacht, R.; Barres, B.A.; Thaler, J.P.; et al. Microglial Inflammatory Signaling Orchestrates the Hypothalamic Immune Response to Dietary Excess and Mediates Obesity Susceptibility. Cell. Metab. 2017, 26, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, T.L.; Hargrave, S.L.; Swithers, S.E.; Sample, C.H.; Fu, X.; Kinzig, K.P.; Zheng, W. Inter-relationships among diet, obesity and hippocampal-dependent cognitive function. Neuroscience. 2013, 253, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, M.; Baars, T.; Guyenet, S. The relationship between high-fat dairy consumption and obesity, cardiovascular, and metabolic disease. Eur. J. Nutr. 2013, 52, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, H.; Yin, Y.; Li, J.; Tang, Y.; Purkayastha, S.; Li, L.; Cai, D. Obesity- and aging-induced excess of central transforming growth factor-beta potentiates diabetic development via an RNA stress response. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Yuan, L.; Yu, H.; Xi, Y.; Xiao, R. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in the brain of diet-induced obese rats but not in diet-resistant rats. Life. Sci. 2014, 110, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, M.F.; Alzamendi, A.; Harnichar, A.E.; Castrogiovanni, D.; Zubiría, M.G.; Spinedi, E.; Giovambattista, A. Role of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in white adipose tissue beiging. Life. Sci. 2023, 322, 121681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houstis, N.; Rosen, E.D.; Lander, E.S. Reactive oxygen species have a causal role in multiple forms of insulin resistance. Nature. 2006, 440, 944–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ebenezer, P.J.; Dasuri, K.; Fernandez-Kim, S.O.; Francis, J.; Mariappan; N. ; Gao, Z.; Ye, J., Bruce-Keller, A.J.; Keller, J.N. Aging is associated with hypoxia and oxidative stress in adipose tissue: implications for adipose function. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 301, E599–E607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado-Somoza, A.; Teijeira-Fernández, E.; Fernández, A.L.; GonzálezJuanatey, J.R.; Eiras, S. 2010 Proteomic analysis of epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissue reveals differences in proteins involved in oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2010, 299, H202–H209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, E.K.; Olson, D.M.; Bernlohr, D.A. High-fat diet induces changes in adipose tissue trans-4-oxo-2-nonenal and trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal levels in a depot-specific manner. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 63, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauck, A.K.; Zhou, T.; Hahn, W.; Petegrosso, R.; Kuang, R.; Chen, Y. , Bernlohr, D.A. Obesity-induced protein carbonylation in murine adipose tissue regulates the DNA-binding domain of nuclear zinc finger proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 13464–13476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M.; MacAuley, S.L.; Holtzman, D.M. Changes in insulin and insulin signaling in Alzheimer’s disease: cause or consequence? J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 1375–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, J.; Laedtke, T.; Parisi, J.E.; O’Brien, P.; Petersen, R.C.; Butler, P.C. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in alzheimer disease. Diabetes. 2004, 53, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, K.; Wang, H.Y.; Kazi, H.; Han, L.Y.; Bakshi, K.P.; Stucky, A.; Fuino, R.L.; Kawaguchi, K.R.; Samoyedny, A.J.; Wilson, R.S.; et al. Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation and cognitive decline. J. Clin. Invest. 2012, 122, 1316–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillo, C.A.; Piroli, G.G.; Lawrence, R.C.; Wrighten, S.A.; Green, A.J.; Wilson, S.P.; Sakai, R.R.; Kelly, S.J.; Wilson, M.A.; Mott, D.D.; et al. Hippocampal insulin resistance impairs spatial learning and synaptic plasticity. Diabetes. 2015, 64, 3927–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, J.R.; Lyra, E.; Silva, N.M.; Figueiredo, C.P.; Frozza, R.L.; Ledo, J.H.; Beckman, D.; Katashima, C.K.; Razolli, D.; Carvalho, B.M.; et al. Alzheimer-associated Ab oligomers impact the central nervous system to induce peripheral metabolic deregulation. Mol. Med. 2015, 7, 190–210. [Google Scholar]

- Yarchoan, M.; Toledo, J.B.; Lee, E.B.; Arvanitakis, Z.; Kazi, H.; Han, L.Y.; Louneva, N.; Lee, V.M.; Kim, S.F.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; et al. Abnormal serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 is associated with tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease and tauopathies. Acta. Neuropathol. 2014, 128, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.Q.; De Felice, F.G.; Fernandez, S.; Chen, H.; Lambert, M.P.; Quon, M.J.; Krafft, G.A.; Klein, W.L. Amyloid b oligomers induce impairment of neuronal insulin receptors. FASEB. J. 2008, 22, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenco, M.V.; Ferreira, S.T.; De Felice, F.G. Neuronal stress signaling and eIF2a phosphorylation as molecular links between Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. Prog. Neurobiol. 2015, 129, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviles-Olmos, I.; Limousin, P.; Lees, A.; Foltynie, T. Parkinson’s disease, insulin resistance and novel agents of neuroprotection. Brain. 2013, 136, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, V.H. The influence of systemic inflammation on inflammation in the brain: implications for chronic neurodegenerative disease. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2004, 18, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, R.; Roden, M. ESCI Award 2006. Mitochondrial function and endocrine diseases. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 37, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantham Prabhakara, J.P.; Feist, G.; Thomasson, S.; Thompson, A.; Schommer, E.; Ghribi, O. Differential effects of 24-hydroxycholesterol and 27-hydroxycholesterol on tyrosine hydroxylase and alpha-synuclein in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. J. Neurochem. 2008, 107, 1722–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-Y.; Liu, S.-F.; Zhuang, J.L.; Li, M.M.; Huang, Z.-P.; Chen, Y.H.; Chen, X.-R.; Chen, C.-N.; Li-Chao Ye, S.L. Recent research progress on metabolic syndrome and risk of Parkinson's disease. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 34, 719–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraglia, F.; Colla, E. ; Microbiome, Parkinson’s disease and molecular mimicry. Cells. 2019, 8, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erny, D.; Hrabě de Angelis, A.L.; Jaitin, D.; Wieghofer. P. ; Staszewski, O. ; David, E. ; Keren-Shaul, H.; Mahlakoiv, T.; Jakobshagen, K.; Buch, T.; et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C. , Liao, J., Xia, Y., Liu, X., Jones, R., Haran, J., McCormick, B.; Sampson, T.R.; Alam, A.; Ye, K. Gut microbiota regulate Alzheimer’s disease pathologies and cognitive disorders via PUFA-associated neuroinflammation. Gut. 2022, 71, 2233–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnecke, T. , Schäfer, K.-H., Claus, I., Del Tredici, K., Jost, W.H. Gastrointestinal involvement in Parkinson’s disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. NPJ. Parkinsons. Dis. 2022, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, T.R.; Debelius, J.W.; Thron, T.; Janssen, S.; Shastri, G.G.; Ilhan, Z.E. , Challis, C.; Schretter, C.E.; Rocha, S.; Gradinaru, V.; et al. Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell. 2016, 167, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, D.-o. Holtzman, D.M. Current understanding of the Alzheimer’s disease-associated microbiome and therapeutic strategies. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Pavert, S.; Oliver, B.J.; Goverse, G.; Vondenhoff, M.F.; Greuter, M.; Beke, P.; Kusser, K.; Höpken, U.E.; Lipp, M.; Niederreither, K.; Blomhoff, R. Chemokine CXCL13 is essential for lymph node initiation and is induced by retinoic acid and neuronal stimulation. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Harker, N.; Moreira-Santos, L.; Ferreira, M.; Alden, K.; Timmis, J.; Foster, K.; Garefalaki, A.; Pachnis, P.; Andrews, P.; et al. Differential RET signaling pathways drive development of the enteric lymphoid and nervous systems. Sci. Signal. 2012, 5, ra55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Pavert, S.A.; Ferreira, M.; Domingues, R.G.; Ribeiro, H.; Molenaar, R.; Moreira-Santos, L.; Almeida, F.F.; Ibiza, S.; Barbosa, I.; Goverse, G. Maternal retinoids control type 3 innate lymphoid cells and set the offspring immunity. Nature. 2014, 508, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.; Arti,s D. ; Chiu, I.M. Neuro-immune Interactions in the Tissues. Immunity. 2020, 52, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiga-Fernandes, H.; Mucida, D. Neuro-Immune Interactions at Barrier Surfaces. Cell. 2016, 165, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouassi, E.; Li, S.Y.; Boukhris, W.; Millet, I.; Revillard, J.P. Opposite effects of the catecholamines dopamine and norepinephrine on murine polyclonal B-cell activation. Immunopharmacology. 1988, 16, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruszewska, B.; Felten, S.Y.; Moynihan, J.A. Alterations in cytokine and antibody production following chemical sympathectomy in two strains of mice. J. Immunol. 1995, 155, 4613–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiga-Fernandes, H.; Coles, M.C.; Foster, K.E.; Patel, A.; Williams, A.; Natarajan, D.; Barlow, A.; Pachnis, V.; Dimitris, Kioussis. Tyrosine kinase receptor RET is a key regulator of Peyer's patch organogenesis. Nature. 2007, 446, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vulchanova, L.; Casey, M.A.; Crabb, G.W.; Kennedy, W.R.; Brown, D.R. Anatomical evidence for enteric neuroimmune interactions in Peyer's patches. J Neuroimmunol. 2007, 185, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; von Wasielewski, R.; Lindenmaier, W.; Dittmar, K.E.J. Immmunohistochemical study of the blood and lymphatic vasculature and the innervation of mouse gut and gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2007, 36, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprowicz, D.J. Immmunohistochemical study of the blood and lymphatic vasculature and the innervation of Kohm AP, Berton MT, Chruscinski AJ, Sharpe A, V Sanders VM. Stimulation of the B cell receptor, CD86 (B7-2), and the beta 2-adrenergic receptor intrinsically modulates the level of IgG1 and IgE produced per B cell. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 680–690. [Google Scholar]

- Sitkauskiene, B.; Sakalauskas, R. The role of beta(2)-adrenergic receptors in inflammation and allergy. Curr. Drug. Targets. Inflamm Allergy 2005, 4, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, R.H.; Pongratz, G.; Weidler, C.; Linde, H-J. ; Kirschning, C.J.; Glück, T.; Schölmerich, J.; Falk, W. Ablation of the sympathetic nervous system decreases gram-negative and increases gram-positive bacterial dissemination: key roles for tumor necrosis factor/phagocytes and interleukin-4/lymphocytes. J. Infect. Dis 2005, 192, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheadle, G.A.; Costantini, T.W.; Bansal, V.; Eliceiri, B.P.; Coimbra, R. Cholinergic signaling in the gut: a novel mechanism of barrier protection through activation of enteric glia cells. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt). 2014, 15, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, D.; Miller, J.; Merad, M. Dendritic cell and macrophage heterogeneity in vivo. Immunity. 2011, 35, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rescigno, M.; Urbano, M.; Valzasina, B.; Francolini, M.; Rotta, G.; Bonasio, R.; Granucci, F.; Kraehenbuhl, J.P.; Ricciardi-Castagnoli, P. Dendritic cells express tight junction proteins and penetrate gut epithelial monolayers to sample bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niess, J.H.; Brand, S.; Gu, X.; Landsman, L.; Jung, S.; McCormick, B.A.; Vyas, J.M.; Boes, M.; Ploegh, H.L.; Fox, J.G.; Littman, D.R.; Reinecker, H.C. CX3CR1-mediated dendritic cell access to the intestinal lumen and bacterial clearance, Science. 2005, 307, 254–258.

- Mazzini, E.; Massimiliano, L.; Penna, G.; Rescigno, M. Oral tolerance can be established via gap junction transfer of fed antigens from CX3CR1 macrophages to CD103 dendritic cells. Immunity. 2011, 35, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rescigno, M. Intestinal dendritic cells. Adv. Immunol. 2010, 107, 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, C.L.; Aumeunier, A.M.; Mowat, A.M. Intestinal CD103+ dendritic cells: master regulators of tolerance? Trends. Immunol. 2011, 32, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadis, U.; Wahl, B.; Schulz, O.; Hardtke-Wolenski, M.; Schippers, A.; Wagner, N.; Müller, W. .; Sparwasser, T.; Förster, R.; Pabst, O. Intestinal tolerance requires gut homing and expansion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the lamina propria. Immunity. 2011, 34, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhar, G.; Kolesnikov, M. Intestinal macrophages and DCs close the gap o tolerance. Immunity. 2014, 40, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schepper, S.; Stakenborg, N.; Matteoli, G.; Verheijden, S.; Boeckxstaens, G.E. Muscularis macrophages: Key players in intestinal homeostasis and disease. Cell. Immunol. 2018, 330, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabanyi, I.; Muller, P.A.; Feighery, L.; Oliveira, T.Y.; Costa-Pinto, F.A.; Mucida, D. Neuro-immune Interactions Drive Tissue Programming in Intestinal Macrophages. Cell. 2016, 164, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, A.G.; Sahawneh, M.A.; Lange, P.S.; Bae, N.; Egea, M.; Ratan, R.R. Arginase 1 regulation of nitric oxide production is key to survival of trophic factor-deprived motor neurons. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 8512–8516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson, B.E.; Midtvedt, T.; Strandberg, K. Effects of microbial contamination on the cecum enlargement of germfree rats. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1970, 5, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, P.A.; Koscsó, B.; Rajani, G.M.; Stevanovic, K.; Berres, M.L.; Hashimoto, D.; Mortha, A.; Leboeuf, M.; Li, X.-M.; Mucida, D.; et al. Crosstalk between muscularis macrophages andentericneurons regulates gastrointestinal motility. Cell. 2014, 158, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stead, R.H.; Dixon, M.F.; Bramwell, N.H.; Riddell, R.H.; Bienenstock, J. Mast cells are closely apposed to nerves in the human gastrointestinal mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1989, 97, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.J.; Rothman, T.P.; Gershon, M.D. Development of the interstitial cell of Cajal: origin, kit dependence and neuronal and nonneuronal sources of kit ligand. J. Neurosci. Res. 2000, 59, 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt EB, Strait RT, Hershko D, Wang Q, Muntel EE, Scribner TA, Zimmermann N, Finkelman FD, Rothenberg ME. Mast cells are required for experimental oral allergen-induced diarrhea. J. Clin. Invest. 2003, 112, 1666–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Winter BY, van den Wijngaard RM, de Jonge WJ. Intestinal mast cells in gut inflammation and motility disturbances. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012, 1822, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, G. : Wang, B.; Stanghellini, V.; de Giorgio, R.; Cremon, C.; Di Nardo, G.; Trevisani, M.; Campi, B.; Geppetti, P.; Tonini, M.; et al. Mast cell-dependent excitation of visceral-nociceptive sensory neurons in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007, 132, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L. , Luo QQ, Chen SL. The role of intestinal mast cell infiltration in irritable bowel syndrome. J. Dig. Dis. 2021, 22, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystrom, E.E.L.; Birchenough, G.M.H.; van der Post, S.; Arike, L.; Gruber, A.D.; Hansson, G.C.; Johansson, M.E.V. Calcium-activated Chloride Channel Regulator 1 (CLCA1) Controls Mucus Expansion in Colon by Proteolytic Activity. EBioMedicine. 2018, 33, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Jacobson, A.; Meerschaert, K.A.; Sifakis, J.J.; Wu, M.; Chen, X.; Yang, T.; Zhou, Y. .; Anekal, P.V.; Rucker, R.A; et al.. Nociceptor neurons direct goblet cells via a CGRP-RAMP1 axis to drive mucus production and gut barrier protection. Cell. 2022, 185, 4190–4205.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennstein, S.B.; Uhrberg, M. Biology and therapeutic potential of human innate lymphoid cells. FEBS. J. 2022, 289, 3967–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klose, C.S.N.; Mahlakõiv, T.; Moeller, J.B.; Rankin, L.C.; Flamar, A.L.; Kabata, H.; Monticelli, L.A.; Moriyama, S.; Putzel, G.G.; Rakhilin, N.; et al. The neuropeptide neuromedin U stimulates innate lymphoid cells and type 2 inflammation. Nature. 2017, 549, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracey, K.J. Physiology and immunology of the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 117, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matteoli, G.; Boeckxstaens, G.E. The vagal innervation of the gut and immune homeostasis. Gut 2013, 62, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galle-Treger, L.; Suzuki, Y.; Patel, N.; Sankaranarayanan, I.; Aron, J.L.; Hadi Maazi, H.; Chen, L.; Akbari, O. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist attenuates ILC2-dependent airway hyperreactivity. Nat. Comm. 2016, 7, 13202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalli, J.; Colas, R.A.; Arnardottir, H.; Serhan, C.N. Vagal Regulation of Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells and the Immunoresolvent PCTR1 Controls Infection Resolution. Immunity. 2017, 46, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, S.; Brestoff, J.R.; Flamar, A-L. ; Moeller, J.B.; Klose, C.S.N.; Rankin, L.C.; Yudanin, L.A.; Monticelli, L.A.; Putzel, G.B.; Rodewald, H-R.; et al. β2-adrenergic receptor-mediated negative regulation of group 2 innate lymphoid cell responses. Science. 2018, 359, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallrapp, A.; Riesenfeld, S.J.; Burkett, P.R.; Abdulnour, R.E.; Nyman, J.; Dionne, D.; Hofree, M.; Cuoco, M.S.; Rodman, C.; Farouq, D.; et al. The neuropeptide NMU amplifies ILC2-driven allergic lung inflammation. Nature. 2017, 549, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatrini, L.; Wieduwild. E.; Guia, S.; Bernat, C.; Glaichenhaus. N.; Vivier, E.; Ugolini, S. Host resistance to endotoxic shock requires the neuroendocrine regulation of group 1 innate lymphoid cells. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 3531–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.N.; Guo, Y.B.; Li, X.; Li, C.L.; Tan, W.P.; Fan, X.L.; Qin, Z.L.; Chen, D.; Wen, W.P.; Zheng, S.G.; et al. ILC2 frequency and activity are inhibited by glucocorticoid treatment via STAT pathway in patients with asthma. Allergy. 2018, 73, 1860–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, S.; Abdulnour, R.E.; Burkett. P.R ; Lee, S. ; Cronin, S.J. ; Pascal, M.A.; Laedermann, C.; Foster, S.L.; Tran, J.V.; Lai, N. et al. Silencing Nociceptor Neurons Reduces Allergic Airway Inflammation. Neuron. 2015, 87, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seillet, C.; Luong, K.; Tellier, J.; Jacquelot, N.; Shen, R.D.; Hickey, P.; Wimmer, V.C.; Whitehead, L.; Rogers, K.; Smyth, G.K; et al. The neuropeptide VIP confers anticipatory mucosal immunity by regulating ILC3 activity. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, M.C.; Araujo, L.P.; Maricato, J.T.; Nascimento, V.M.; Guereschi, M.G.; Rezende, R.M.; Quintana, F.J.; Basso, A.S. Norepinephrine Controls Effector T Cell Differentiation through beta2-Adrenergic Receptor-Mediated Inhibition of NF-kappaB and AP-1 in Dendritic Cells. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestroni, G.J. Dendritic cell migration controlled by alpha 1b-adrenergic receptors. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 6743–6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, M.; Chorny, A.; Gonzalez-Rey, E.; Ganea, D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide generates CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in vivo. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005, 78, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padro, C.J.; Sanders, V.M. Neuroendocrine regulation of inflammation. Semin. Immunol. 2014, 26, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakai, A.; Hayano, Y.; Furuta, F.; Noda, M.; Suzuki, K. Control of lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes through β2-adrenergic receptors. J. Exp. Med. 2014, 211, 2583–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaz, B.; Sinniger, V.; Hoffmann, D.; Clarençon, D.; Mathieu, N.; Dantzer, C.; Vercueil, L.; Picq, C.; Trocmé, C.; Faure, P.; et al. Chronic vagus nerve stimulation in Crohn's disease: a 6-month follow-up pilot study. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016, 28, 948–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, F.A.; Chavan, S.S.; Miljko, S.; Grazio, S.; Sokolovic, S.; Schuurman, P.R.; Mehta, A.D.; Levine, Y.A.; Faltys, M.; Zitnik. R.; et al. Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cytokine production and attenuates disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016, 113, 8284–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarini, S.; Altavilla, D.; Cainazzo, M.M.; Giuliani, D.; Bigiani, A.; Marini, H.; Squadrito, G.; Minutoli, L.; Bertolini, A.; Marini. R.; et al. Efferent vagal fibre stimulation blunts nuclear factor-kappaB activation and protects against hypovolemic hemorrhagic shock. Circulation. 2003, 107, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, Y.A.; Koopman, F.A.; Faltys, M.; Caravaca, A.; Bendele, A.; Zitnik, R.; Margriet, J.; Vervoordeldonk, M.J.; Tak, P. P, Neurostimulation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway ameliorates disease in rat collagen-induced arthritis. PLoS. One. 2014, 9, e104530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carloni, S.; Rescigno, M. The gut-brain vascular axis in neuroinflammation. Semin. Immunol. 2023, 69, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braniste, V.; Al-Asmakh, M.; Kowal, C.; Anuar, F.; Abbaspour, A.; Tóth, M.; Korecka, A.; Bakocevic, N.; Ng, L.G.; Kundu, P. The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 19, 6:263ra158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouries, J.P.; Silvestri, A.; Spadoni, I.; Sorribas, M.; Wiest, R.; Mileti, E.; Galbiati, M.P.; Adorini, L.; Penna, G.; Rescigno, M. Microbiota-driven gut vascular barrier disruption is a prerequisite for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis development. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 1216–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häuser, W.; Janke, K-H. ; Klump, B.; Hinz, A. Anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: comparisons with chronic liver disease patients and the general population. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 2011, 17, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panara, A.J.; Yarur, A.J.; Rieders, B.; Proksell, S.; Deshpande, A.R.; Abreu, M.T.; Sussman, D.A. The incidence and risk factors for developing depression after being diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 39, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tommaso, N.; Santopaolo, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ponziani, F.R. The Gut-Vascular Barrier as a New Protagonist in Intestinal and Extraintestinal Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obata, Y.; Castaño, A.; Boeing, S.; Bon-Frauches, A.C.; Fung, C.; Fallesen, T.; Gomez de Agüero, N.; Yilmaz, B.; Lopes, R.; Huseynova, A. Neuronal programming by microbiota regulates intestinal physiology. Nature. 2020, 578, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, N.; Chida, Y.; Aiba, Y.; Sonoda, J.; Oyama, N.; Yu, X-N. ; Kubo, C.; Koga, Y. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J Physiol 2004, 558, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzi, A.; Reichmann, F.; Meinitzer, A.; Mayerhofer, R.; Jain, P.; Hassan, A.M.; Fröhlich, E.E.; Wagner, K.E.; Rinner, B.; Holzer, P. Synergistic effects of NOD1 or NOD2 and TLR4 activation on mouse sickness behavior in relation to immune and brain activity markers. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2015, 44, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savignac, H.M.; Tramullas, M.; Kiely, B.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Bifidobacteria modulate cognitive processes in an anxious mouse strain. Behav. Brain. Res. 2015, 287, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröhlich, E.E.; Farzi, A.; Mayerhofer, R.; Reichmann, F.; Jačan, A.; Wagner, B.; Zinser, E.; Bordag, N.; Magnes, C.; Fröhlich, E.; et al. Cognitive impairment by antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis: Analysis of gut microbiota-brain communication. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2016, 56, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.C.; Olson, C.A.; Hsiao, E.Y. Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Nat Neurosci. 2017, 20, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwin, E.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Recent developments in understanding the role of the gut microbiota in brain health and disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1420, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsythe, P.; Bienenstock, J.; Kunze, W.A. Vagal pathways for microbiome-brain-gut axis communication. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014, 817, 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lyte, M.; Li, W.; Opitz, N.; Gaykema, R.P.A.; Goehler, L.E. Induction of anxiety-like behavior in mice during the initial stages of infection with the agent of murine colonic hyperplasia Citrobacter rodentium. Physiol. Behav. 2006, 2006. 89, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanida, M.; Yamano, T.; Maeda, K.; Okumura, N.; Fukushima, Y.; Nagai, K. Effects of intraduodenal injection of Lactobacillus johnsonii La1 on renal sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in urethane-anesthetized rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2005, 389, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Kuruma, I. Effect of bacterial lipopolysaccharide on the content of serotonin and norepinephrine in rabbit brain. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1966, 16, 478–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, P.J.; de Boer, A.B.G.; Breimer, D.D. Pharmacological investigations on lipopolysaccharide-induced permeability changes in the blood-brain barrier in vitro. Microvasc. Res. 2003, 65, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröhlich, E.E.; Farzi, A.; Mayerhofer, R.; Reichmann, F.; Jačan, A.; Wagner, B.; Zinser, E.; Bordag, N.; Magnes, C.; Fröhlich, E.; et al. Cognitive impairment by antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis: Analysis of gut microbiota-brain communication. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2016, 56, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyles, L.; Snelling, T.; Umlai, U-K. ; Jeremy, KV.; Nicholson, J.K.; Carding, S.R.; Glem, R.C Microbiome-host systems interactions: protective effects of propionate upon the blood-brain barrier McArthur, S. Microbiome-host systems interactions: protective effects of propionate upon the blood-brain barrier. Microbiome. 2018, 6, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, G.; Grenham, S.; Scully, P.; Fitzgerald, P.; Moloney, R.D.; Shanahan, F.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. The microbiome-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner. Mol. Psychiatry. 2013, 18, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikocka-Walus, A.; Knowles, S.R.; Keefer, L.; Graff, L. Controversies revisited: a systematic review of the comorbidity of depression and anxiety with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 2016, 22, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuendorf, R.; Harding, A.; Stello, N.; Hanes, D.; Wahbeh, H. Depression and anxiety in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 87, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaus, S.; Schulte, B.; Al-Massad, N.; Thieme, F.; Schulte, D.M.; Bethge, J.; Rehman, A.; Tran, F.; Aden, K.; Häsler, R.; et al. Increased tryptophan metabolism is associated with activity of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017, 153, 1504–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobesky, J.L.; Barrientos, R.M.; De May, H.S.; Thompson, B.M.; Weber, M.D.; Watkins, L.R.; Maier, S.F. High-fat diet consumption disrupts memory and primes elevations in hippocampal IL-1β, an effect that can be prevented with dietary reversal or IL-1 receptor antagonism. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2014, 42, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, O.J.; Robison, L.S.; Salinero, A.E.; Abi-Ghanem, C.; Mansour, F.M.; Kelly, R.D.; Tyagi, A.; Brawley, R.R.; Ogg, J.D.; Zuloaga, K.L. High-fat diet exacerbates cognitive decline in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and mixed dementia in a sex-dependent manner. J. Neuroinflammation. 2022, 19, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.S.; Watson, K.Q.; Rebeck, G.W. High-fat diet increases gliosis and immediate early gene expression in APOE3 mice, but not APOE4 mice. J. Neuroinflammation. 2021, 18, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Torres, J.D.; Ontiveros-Angel, P.; Stuffle, E.C.; Solak, S.; Terrones, E.; Tyner, E.; Oropeza, M.; Dela Peña, I.; Obenaus, A.; Ford, B.D.; et al. Short-term exposure to an obesogenic diet during adolescence elicits anxiety-related behavior and neuroinflammation: Modulatory effects of exogenous neuregulin-1. Transl. Psychiatry. 2022, 12, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, G.; Grenham, S.; Scully, P.; Fitzgerald, P.; Moloney, R.D.; Shanahan, F.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. The microbiome-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner. Mol Psychiatry 2013, 18, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikocka-Walus, A.; Knowles, S.R.; Keefer, L.; Graff, L. Controversies revisited: a systematic review of the comorbidity of depression and anxiety with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuendorf, R.; Harding, A.; Stello, N.; Hanes, D.; Wahbeh, H. Depression and anxiety in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2016, 87, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaus, S.; Schulte, B.; Al-Massad, N.; Thieme, F.; Schulte, D.M.; Bethge, J.; et al. Increased tryptophan metabolism is associated with activity of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 1504–1516.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Choi, G.M.; Sur, B. Silibinin prevents depression-like behaviors in a single prolonged stress rat model: the possible role of serotonin. BMC Complement Med Ther 2020, 20, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Mahony, S.M.; Clarke, G.; Borre, Y.E.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Behav Brain Res 2015, 277, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirzgalska, R.M.; Seixas, E.; Seidman, J.S.; Link, V.M.; Sánchez, N.M. , Mahú, I.; Mendes, R.; Gres, V.; Kubasova, N.; Morris, I.; et al. Sympathetic neuron associated macrophages contribute to obesity by importing and metabolizing norepinephrine. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.; Ruiz, H.H.; Jhun, K.; Finan, B.; Oberlin, D.J.; van der Heide, V.; Kalinovich, A.V.; Petrovic, N.; Wolf, Y.; Clemmensen, C. Alternatively activated macrophages do not synthesize catecholamines or contribute to adipose tissue adaptive thermogenesis. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskell, W.H. On the structure, distribution and function of the nerves which innervate the visceral and vascular systems. J Physiol. 1886, 7, 1–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthoud, H.; Carlson, N.; Powley, T. Topography of efferent vagal innervation of the rat gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1991, 260, R200–R207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, S.; Chen, J.; Behles, R.R.; Hyun, J.; Kopin, A.S.; Moran, T.H. Differential body weight and feeding responses to high-fat diets in rats and mice lacking cholecystokinin 1 receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007, 293, R55–R63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulino, G.; Barbier de la Serre, C.; Knotts, T.A.; Oort, P.J.; Newman, J.W.; Adams, S.H.; Raybould, H.E. Increased expression of receptors for orexigenic factors in nodose ganglion of diet-induced obese rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 296, E898–E903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lartigue, G.; Ronveaux, C.C.; Raybould, H.E. Deletion of leptin signaling in vagal afferent neurons results in hyperphagia and obesity. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnone, G.; De Benedetti, F.; Bracci-Laudiero, L. NGF and its receptors in the regulation of inflammatory response. IJMS. 2017, 18, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinshagen, M.; Rom, H.; Steinkamp, M.; Lieb, K.; Geerling, I.; Von Herbay, A.; Flamig, G.; Eysselein, V.E.; Adler, G. Protective role of neurotrophins in experimental inflammation of the rat gut. Gastroenterology. 2000, 119, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, A.M.; Brierley, S.M.; Isaacs, N.; Hughes, P.A.; Castro, J.; Blackshaw, L.A. Sprouting of colonic afferent central terminals and increased spinal mitogen-activated protein kinase expression in a mouse model of chronic visceral hypersensitivity. J. Comp. Neurol. 2012, 520, 2241–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).