1. Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most frequent heart valve disease in elderly population and the prevalence of a concomitant internal carotid artery (ICA) stenosis ≥ 50% ranges from 13 to 33%1,2. The increased afterload of the left ventricle determined by the presence of AS results into an abnormal flow pattern distal to the aortic valve, which is characterized by a delayed upstroke, a rounded curve of the waveform which has a reduced magnitude. The typical blood flow pattern of the AS is evident at doppler spectral examination of the supraortic arteries3,4 and could be advocated as a potential cause of underestimation of a carotid artery stenosis5. Duplex Ultrasound (DUS) is the gold standard for diagnosis of ICA stenosis by visualization of the plaque and assessing blood flow velocity, the latter being the mainstem for grading obstruction severity6. Since transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is performed without affecting chest respiratory and cardiac hemodynamic, can be considered a clinical model to investigate the role of AS on supraortic arteries blood flow duplex mediated assessment. The aim of this prospective case-control study was to evaluate the effect of a severe aortic stenosis on carotid and vertebral blood flow velocity indexes before and after TAVI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (CEUR-CET/CEL 20240018953) and informed consent was obtained by all participants. From January 2022 to December 2023, eighty-five consecutive adult patients with severe aortic stenosis with high surgical risk or aged ≥75 years, and suitable for TAVI at the Division of Cardiology of the Azienda Ospedaliera San Carlo, Potenza, Italy underwent supra-aortic Duplex ultrasound (DUS) examination prior to TAVI as a part of the preoperative assessment and after the procedure for the purpose of the study. Severe AS was defined by the presence of an aortic valve area (AVA) <1 cm2 and/or mean transvalvular aortic gradient >40 mmHg and/or peak aortic jet velocity ≥ 4 m/s according to current guidelines7. Patients with carotid occlusion, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF <50%), moderate or severe aortic valve regurgitation before and/or after TAVI, uncontrolled blood pressure, tachyarrhythmias, severe anaemia or hyperthyroidism were excluded from the registry to omit other potential confounding factors that may alter carotid or vertebral blood flow.

2.2. Cardiac Ultrasound

Echocardiographic assessments were carried out using a Vivid E95 ultrasound system (GE Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois, United States) by the same certified physician before and after TAVI. AVA was calculated by the continuity equation, mean gradient by the simplified Bernoulli equation and left ventricular ejection fraction by the biplane Simpson method according to current guidelines8. The Doppler velocity index was measured by dividing the time-integral velocity in the left ventricular outflow tract by the time-integral velocity in the aorta. The severity of regurgitation of native valve and bioprosthesis was assessed by a multiparametric approach and according to current guidelines9,10.

2.3. Duplex Assessment

All DUS examinations were performed by the same certified physician using a General Electric LOGIQ E10 ultrasound system (GE Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois, United States) with a Clear linear array probe. All carotid examinations were performed with grey-scale, Color-Doppler and spectral Doppler velocity determination with an insonation angle between 40 to 60 degrees. Peak systolic velocity (PSV), end-diastolic velocity (EDV) and acceleration time (AC) were evaluated in the common, internal and vertebral artery of both sides prior and after TAVI. Symptomatic or severe carotid artery stenosis defined according to NASCET criteria11,12 were excluded.

2.4. TAVI Procedure

All patients underwent TAVI by experienced physicians. The choice of valve type (self-expanding or balloon-expandable), its size and access site were at the discretion of the Heart team considering the comorbidities and the results of pre-procedural computed tomography. Only patients who underwent a successful TAVI defined by a mean gradient < 20 mmHg, peak velocity < 3 m/s, Doppler velocity index > 0.25, and less than moderate aortic regurgitation were enrolled in our study13.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation or median and inter quartile range where appropriate. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages. The T-student test was utilized to compare the distribution of each variable. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. R software (version 4.3.3, R Development Core Team) was utilized for calculations.

3. Results

Clinical and demographic characteristics are reported in

Table 1. Among the screened patients, a total of forty-five patients (42% men) of a median age of 80 years (IQR 77 - 85) met the inclusion criteria. The mean interval time between pre and post TAVI supra-aortic blood flow indexes assessment was 5 days (IQR 3 – 9). Haemodynamic index changes of examined supraortic vessels before and after TAVI are summarized in

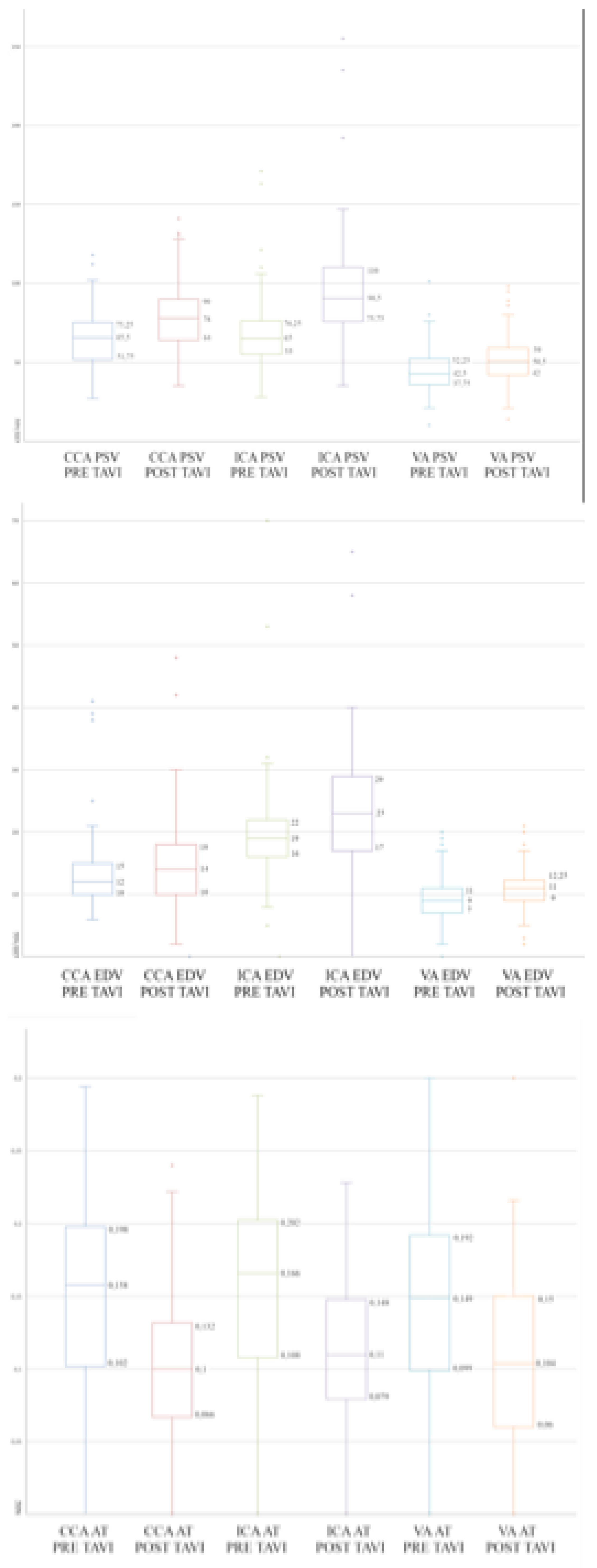

Table 2. The PSV of the assessed supraortic arteries significantly increased after TAVI (respectively common carotid artery 64 ± 17 cm/s vs 78 ± 23 cm/s, p = 0,01; internal carotid artery 68 ± 23 cm/s vs 96 ± 35 cm/s p = 0,01; vertebral artery 45 ± 14 cm/s vs 52 ± 15 cm/s, p = 0,03). The average increase of PSV in common, internal and vertebral arteries was 18%, 29% and 13% respectively. The EDV of the assessed supraortic arteries increased after TAVI (respectively common carotid artery 13 ± 6 cm/s vs 15 ± 7 cm/s, p= ns; internal carotid artery 20 ± 9 cm/s vs 24 ± 9 cm/s cm/s p = 0,01; vertebral artery and 9 ± 4 cm/s vs 11 ± 4 cm/s, p = 0,01). The average increase of EDV in common, internal and vertebral arteries was 9%, 17% and 14% respectively, which is statistically significantly only in ICA e VA. Finally, the mean AC of the assessed supraortic arteries significantly decreased after TAVI (respectively common carotid artery 0,17 ± 0,05 s vs 0,12 ± 0,05 s, p = 0.01; internal carotid artery 0,18 ± 0,05 s vs 0,12 ± 0,04 s p = 0,01; vertebral artery 0,16 ± 0,05 s vs 0,11 ± 0,05 s, p = 0,02). The average decrease of AC was 50%, 42%, 39% respectively. A whisker plot underlying the main results of the study is provided in

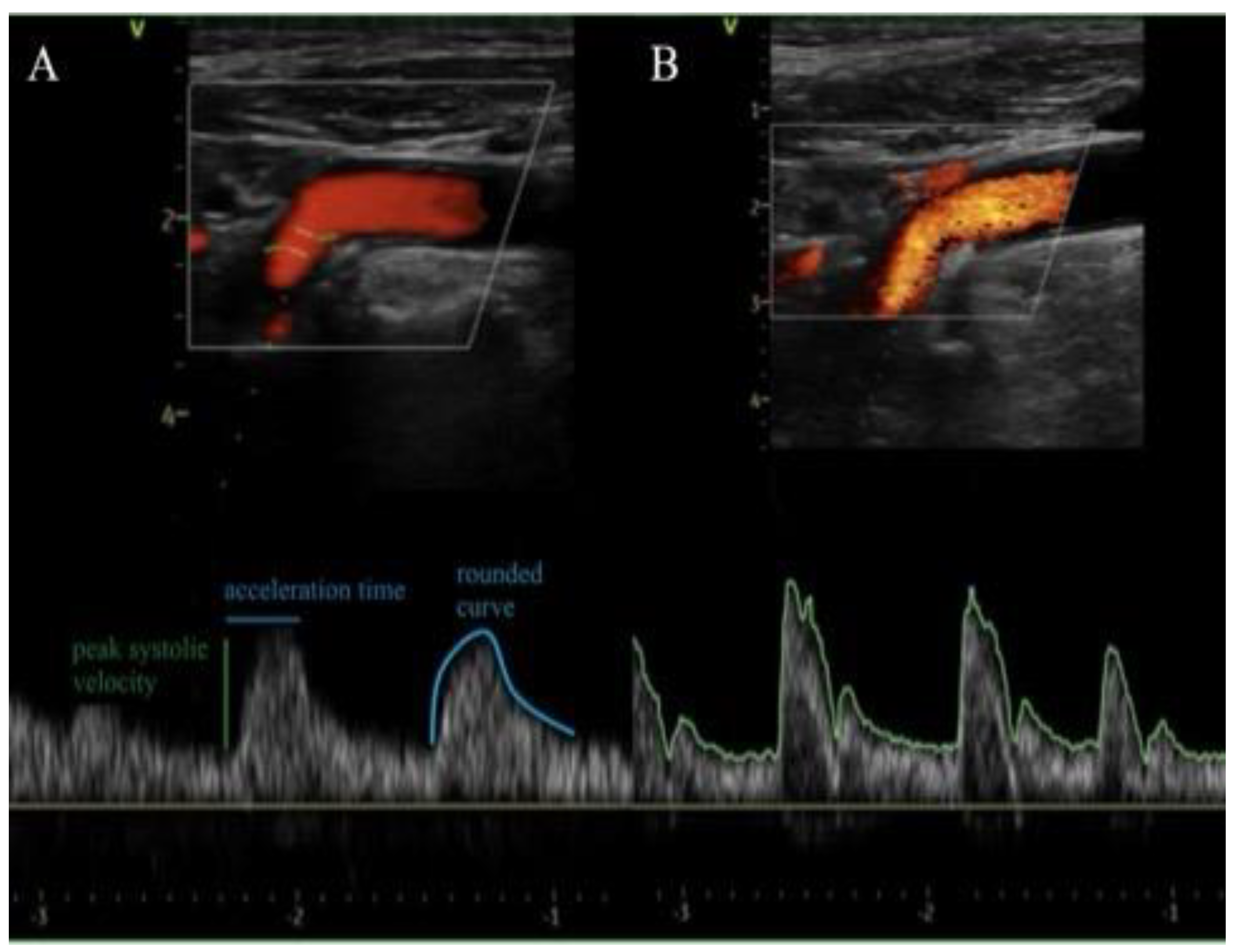

Figure 1. Spectral doppler examinations of the supra-aortic vessels after the procedures revealed no more AS related characteristics as delayed upstroke, rounded curve of the waveform and a reduced magnitude in all cases as shown in

Figure 2. Notably, according to these post TAVI hemodynamic changes, two patients of this population, who preoperatively were diagnosed with non-severe internal carotid artery stenosis based on velocity estimation, overtook the threshold for severity after TAVI.

Table 1.

Demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities and aortic valve parameters in a cohort of 45 patients diagnosed with AS.

Table 1.

Demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities and aortic valve parameters in a cohort of 45 patients diagnosed with AS.

| Variable |

Value |

| Age, y, median (IQR) |

80 (77-85) |

| Male, n (%) |

19 (42) |

| Hypertension, n (%) |

13 (29) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) |

14 (31) |

| DM, n (%) |

3 (7) |

| CKD, n (%) |

4 (9) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) |

13 (29) |

| COPD, n (%) |

3 (7) |

| CAD, n (%) |

18 (40) |

| Previous AMI, n (%) |

4 (9) |

| Previous CABG, n (%) |

0 (0) |

| Previous PCI, n (%) |

16 (36) |

| Aortic valve area, cm2, median (IQR) |

0.7 (0.7-0.8) |

| Preoperative median TG, (IQR) |

43 (40-53) |

| Postoperative median TG, (IQR) |

12 (8-14) |

| Preoperative EF, median (IQR) |

57 (55-61) |

| Mild aortic regurgitation after TAVI, n (%) |

19 (42) |

Table 2.

Supra aortic blood flow velocity indexes and their variation in a cohort of 45 patients diagnosed with AS prior and after TAVI.

Table 2.

Supra aortic blood flow velocity indexes and their variation in a cohort of 45 patients diagnosed with AS prior and after TAVI.

| |

Pre TAVI mean (SD) |

Post TAVI mean (SD) |

∆ % |

p value |

| CCA PSV (cm/s) |

64 (±17) |

78 (±22) |

18 |

0,01 |

| CCA EDV (cm/s) |

13 (±6) |

15 (±6) |

8 |

0,39 |

| CCA AT (s) |

0,168 (±0,05) |

0,112 (±0,04) |

-50 |

0,01 |

| ICA PSV (cm/s) |

68 (±23) |

96 (±35) |

29 |

0,01 |

| ICA EDV (cm/s) |

20 (±9) |

24 (±19) |

17 |

0,01 |

| ICA AT (s) |

0,177 (±0,05) |

0,124 (±0,04) |

-42 |

0,01 |

| VA PSV (cm/s) |

45 (±14) |

52 (±15) |

13 |

0,03 |

| VA EDV (cm/s) |

9 (±4) |

11 (±4) |

13 |

0,01 |

| VA AT (s) |

0,160 (±0,05) |

0,115 (±0,05) |

-39 |

0,02 |

Figure 1.

Effect of aortic stenosis on supraortic arteries duplex determined variables. Box plot of PSV (top), EDV (middle) and AT (bottom) detected on CCA, ICA and VA prior and after TAVI in a cohort of 45 patients diagnosed with AS. PSV = peak systolic velocity; EDV = end diastolic velocity; AT = acceleration time; CCA = common carotid artery; ICA = internal carotid artery; VA = vertebral artery; TAVI = transcatheter aortic valve implantation; AS = aortic stenosis.

Figure 1.

Effect of aortic stenosis on supraortic arteries duplex determined variables. Box plot of PSV (top), EDV (middle) and AT (bottom) detected on CCA, ICA and VA prior and after TAVI in a cohort of 45 patients diagnosed with AS. PSV = peak systolic velocity; EDV = end diastolic velocity; AT = acceleration time; CCA = common carotid artery; ICA = internal carotid artery; VA = vertebral artery; TAVI = transcatheter aortic valve implantation; AS = aortic stenosis.

Figure 2.

Carotid duplex assessment before and after TAVI. Representative ecocolordoppler with spectral curve of internal carotid artery of a patient diagnosed with severe AS showing delayed upstroke (prolonged acceleration time), rounded curve of the waveform and a reduced magnitude before TAVI in A and after the procedure in B with normalization of the spectral curve.

Figure 2.

Carotid duplex assessment before and after TAVI. Representative ecocolordoppler with spectral curve of internal carotid artery of a patient diagnosed with severe AS showing delayed upstroke (prolonged acceleration time), rounded curve of the waveform and a reduced magnitude before TAVI in A and after the procedure in B with normalization of the spectral curve.

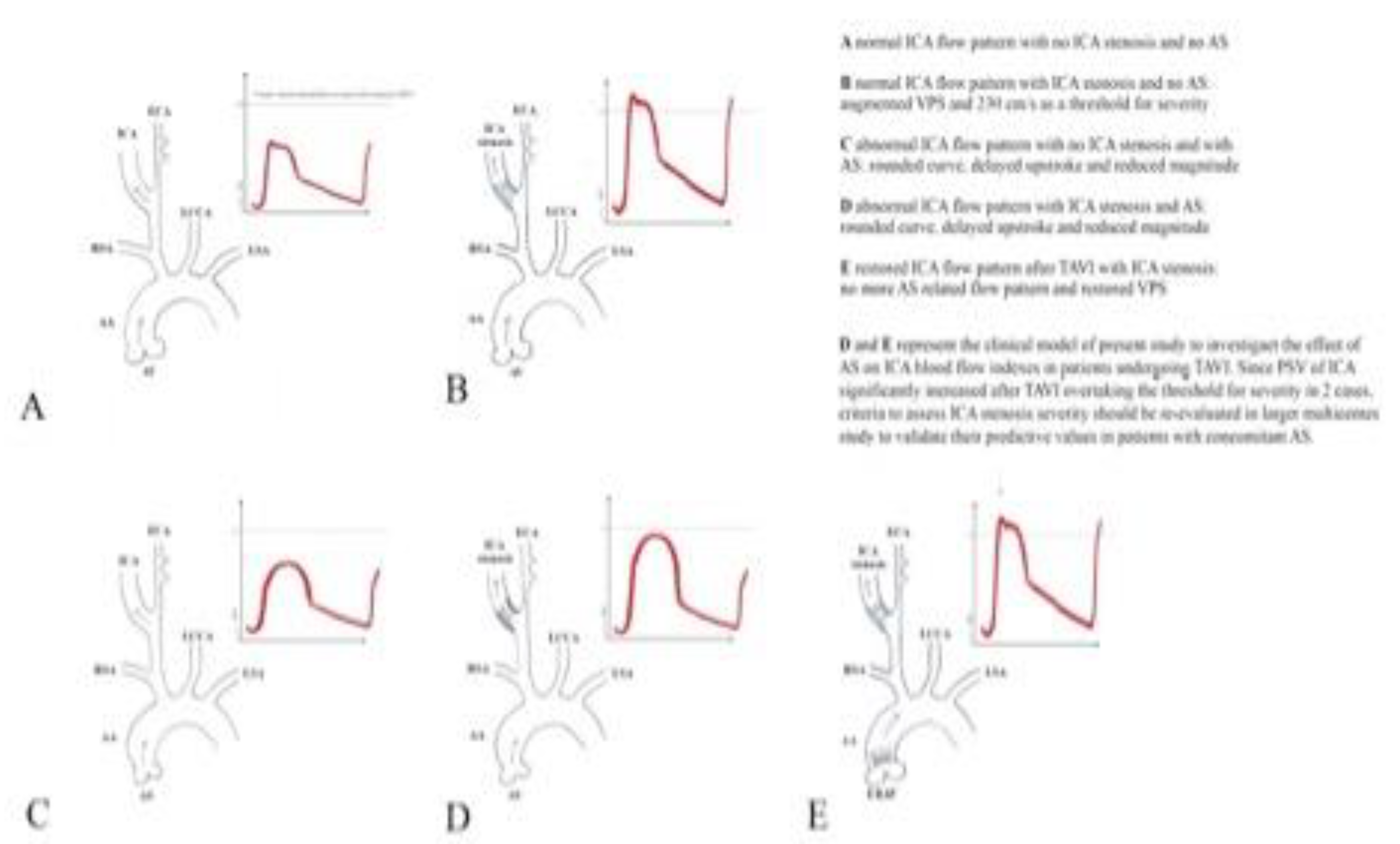

Graphical Abstract.

AA = Ascending Aorta; AS = Aortic Stenosis; AV = Aortic Valve; ECA = External Carotid Artery; ERAV = Endovascular Repaired Aortic Valve; ICA = Internal Carotid Artery; LCCA = Left Common Carotid Artery; LSA = Left Subclavian artery; PSV = Peak Systolic Velocity; RSA = right Subclavian artery.

Graphical Abstract.

AA = Ascending Aorta; AS = Aortic Stenosis; AV = Aortic Valve; ECA = External Carotid Artery; ERAV = Endovascular Repaired Aortic Valve; ICA = Internal Carotid Artery; LCCA = Left Common Carotid Artery; LSA = Left Subclavian artery; PSV = Peak Systolic Velocity; RSA = right Subclavian artery.

In the graphical abstract the 5 spectral wave prototypes of the ICA at DUS are reproduced.

4. Discussion

The study results demonstrate the abnormal flow pattern of supraortic trunks observed at the duplex assessment in the presence of a severe AS, decrease PSV and EDV in common, internal carotid and vertebral arteries and increase AC in the same arteries. So far, hemodynamic changes in the supra-aortic arteries with coexistence of AS have been evaluated with opposite results. In a retrospective registry14, carotid artery waveform abnormalities were investigated, reviewing acceleration time, peak velocity and waveform contour of common, internal and external carotid arteries of 24 patients with various degrees of aortic stenosis. The authors reported that acceleration time increase and peak velocity decrease correlated with the severity of the aortic valve disease. These data are consistent with our study findings supporting the concept that, in the presence of aortic stenosis, the abnormal flow pattern determined by the increased afterload of the LV results in a decreased blood flow velocity in the supraortic arteries. If this pathologic effect could be reversed by eliminating the aortic stenosis was already tested in the past. In a retrospective comparison of PSV and EDV of the internal carotid artery of 92 patients prior and after surgical aortic valve repair (SAVR) no difference could be observed3. Of note, in that study, only 11% of patients underwent SAVR alone. Most patients underwent other cardiac procedures such as coronary artery bypass grafting, concurrent surgery on additional heart valves or other additional surgical procedures resulting in confounding bias. Furthermore, the mean interval between the two examinations was more than six months (182 ± 98 days). Differently in a prospective study, evaluating 30 patients undergoing aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis, a postprocedural decreased acceleration time and an increased peak systolic velocity could be observed in all patients (Cardon et al). In our study we decided to isolate the effect of aortic stenosis of supraortic arteries blood flow by limiting our assessment only to patients undergoing isolated TAVI. In these conditions it is possible to avoid the effect of open chest surgery and other cardiac procedures on the supraortic blood flow pattern. On this background we decided to perform a postoperative duplex scan a few hours after TAVI because we hypotized that supraortic arteries blood flow pattern is restored to normal briefly after TAVI. In accordance with this supposition, our study demonstrated an underestimation of internal carotid artery velocity indexes in presence of an AS. This effect could affect the diagnostic accuracy of duplex carotid artery preoperative assessment.

5. Study Limitations

The small number of patients enrolled and the fact that DUS is an operator-dependent test represent limitations of the study. However, the population is extremely selected and rigorous methodology of DUS examination makes the risk of bias very low.

6. Clinical Perspectives

Prevalence of coexisting severe AS and asymptomatic ICA stenosis >50% is not negligible reaching up to one third of patients diagnosed with aortic valve disease. Despite severe carotid artery stenosis alone is not a risk factor for stroke or mortality in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting17 or TAVI, neurological impairments attributable to ICA disease still affect outcomes of aortic stenosis surgical treatment. Causes need to be clarified and a misdiagnosed severe asymptomatic ICA stenosis could be considered. Since present study demonstrated an underestimation of ICA stenosis severity as a result of the abnormal flow pattern induced by a severe AS, further studies investigating proper preoperative assessment of ICA stenosis of patients scheduled for SAVR are recommended to improve neurological outcomes.

7. Conclusions

Severe AS significantly decreases supra-aortic arteries blood flow and this effect can underestimate the grade of carotid artery stenosis. This study suggests that carotid ultrasound criteria to assess ICA stenosis severity should be re-evaluated in larger multicenter studies to validate their predictive values in patients with concomitant AS and ICA stenosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.; methodology, R.P.; validation, E.S., G.I.; writing R.P; original draft preparation, R.P.; writing—review and editing, R.P and E.S.; supervision, G.I. and V.D’A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (CEUR-CET/CEL 20240018953).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained by all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Author Kabłak-Ziembicka A, Przewłocki T, Hlawaty M, Stopa I, Rosławiecka A, Kozanecki , et al. (2008). Internal carotid artery stenosis in patients with degenerative aortic stenosis. Kardiologia Polska, 66(8), 837–842; discussion 843-4.

- Steinvil A, Leshem-Rubinow E, Abramowitz Y, Shacham Y, Arbel Y, Banai S et al. (2014). Prevalence and predictors of carotid artery stenosis in patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions, 84(6), 1007–1012. [CrossRef]

- Shivapour DM, Javed O, Wu Y, Brinza E, Hornacek D, Conic J, Gornik HL et al. (2020). Changes in Carotid Duplex Ultrasound Velocities After Aortic Valve Replacement for Severe Aortic Stenosis. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 39(1), 139–145. [CrossRef]

- Kleczyński P, Petkow Dimitrow P, Dziewierz A, Surdacki A, Dudek D. (2017). Transcatheter aortic valve implantation improves carotid and vertebral arterial blood flow in patients with severe aortic stenosis: practical role of orthostatic stress test. Clinical Cardiology, 40(7), 492–497. [CrossRef]

- Madhwal S, Yesenko S, Kim ES, Park M, Begelman SM, Gornik HL. Manifestations of Cardiac Disease in Carotid Duplex Ultrasound Examination. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2014 Feb, 7 (2) 200–203. [CrossRef]

- Grant EG, Benson CB, Moneta GL, Alexandrov AV, Baker JD, Bluth EI et al. (2003). Carotid Artery Stenosis: Gray-Scale and Doppler US Diagnosis - Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference. Radiology, 229(2), 340–346. [CrossRef]

- Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J et al; ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022 Feb 12;43(7):561-632. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner H, Hung J, Bermejo J, Chambers JB, Edvardsen T, Goldstein S et al. Recommendations on the echocardiographic assessment of aortic valve stenosis: a focused update from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography, European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging, Volume 18, Issue 3, March 2017, Pages 254–275. [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi WA, Adams D, Bonow RO, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA et al. Recommendations for Noninvasive Evaluation of Native Valvular Regurgitation: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography Developed in Collaboration with the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017 Apr;30(4):303-371. [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi WA, Asch FM, Bruce C, Gillam LD, Grayburn PA, Hahn RT et al. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Valvular Regurgitation After Percutaneous Valve Repair or Replacement: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography Developed in Collaboration with the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Japanese Society of Echocardiography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019 Apr;32(4):431-475. Epub 2019 Feb 20. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson GG, Eliasziw M, Barr HW, Clagett GP, Barnes RW, Wallace MC et al. (1999). The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial. Stroke, 30(9), 1751–1758. [CrossRef]

- Gornik HL, Needleman L, Benenati J, Bendick PP, Hutchisson M, Katanick S et al. SUPPORT FOR STANDARDIZATION OF DUPLEX ULTRASOUND DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR INTERNAL CAROTID ARTERY STENOSIS: A SURVEY FROM THE INTERSOCIETAL ACCREDITATION COMMISSION (IAC). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Mar, 61 (10_Supplement) E2020. [CrossRef]

- VARC-3 WRITING COMMITTEE; Généreux P, Piazza N, Alu MC, Nazif T, Hahn RT et al. Valve Academic Research Consortium 3: updated endpoint definitions for aortic valve clinical research, European Heart Journal, Volume 42, Issue 19, 14 May 2021, Pages 1825–1857. [CrossRef]

- O'Boyle MK, Vibhakar NI, Chung J, Keen WD, Gosink BB. (1996). Duplex sonography of the carotid arteries in patients with isolated aortic stenosis: imaging findings and relation to severity of stenosis. American Journal of Roentgenology, 166(1), 197–202. [CrossRef]

- Cardon C, Chenon D, Meimoun P, Mihaileanu S, Latremouille C, Fabiani JN. Effects of aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis on cervical arterial blood flow. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 2001; 94:103-107.

- Mahmoudi M, Hill PC, Xue Z, Torguson R, Ali G, Boyce SW et al. DO PATIENTS WITH SEVERE ASYMPTOMATIC CAROTID ARTERY STENOSIS HAVE A HIGHER RISK OF STROKE AND MORTALITY FOLLOWING CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS GRAFTING?. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Apr, 57 (14_Supplement) E1611. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).