Submitted:

08 August 2024

Posted:

08 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Population

2.1.2. Intervention

2.1.3. Comparator

2.1.4. Outcomes

2.1.5. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

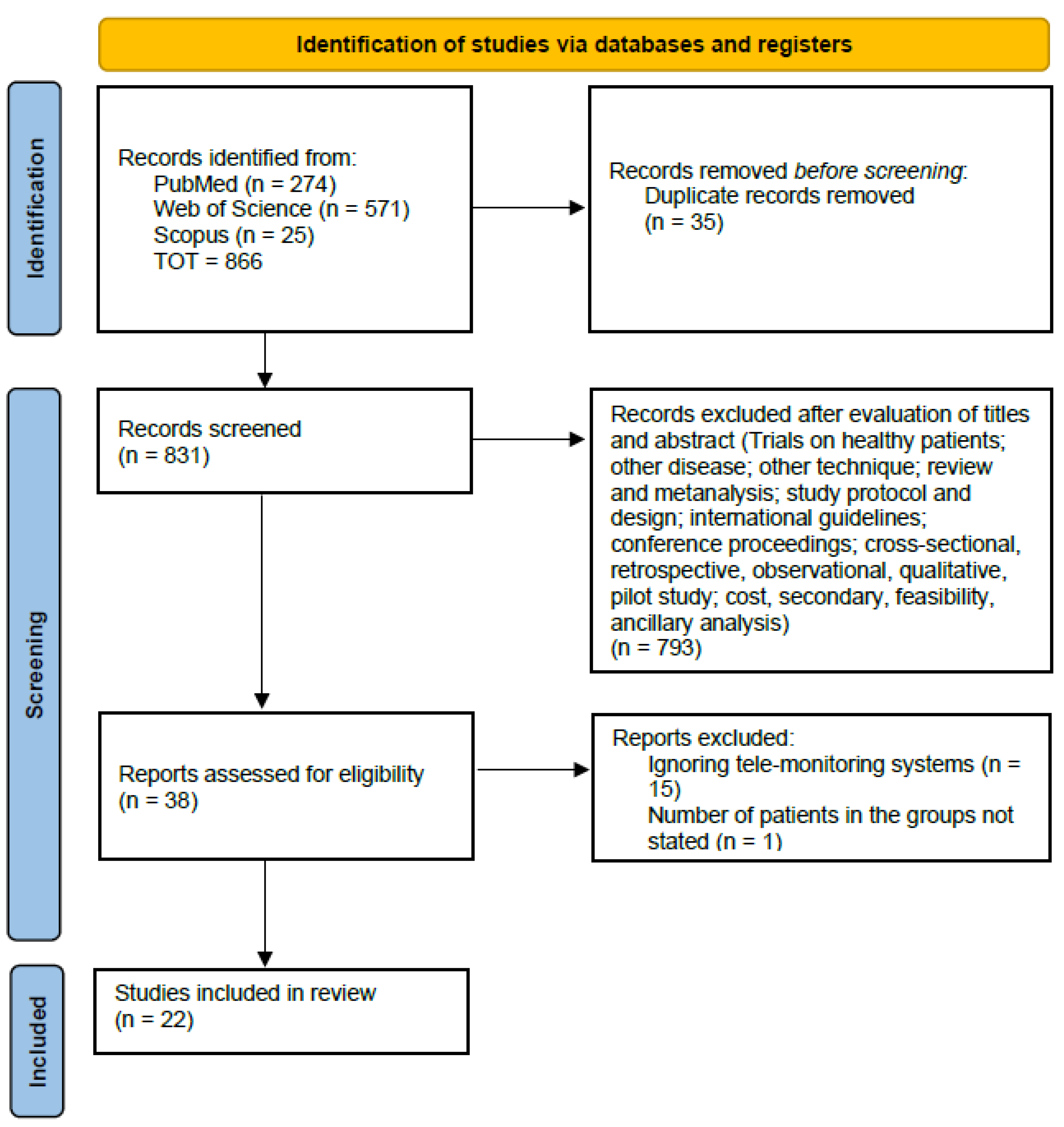

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Interventions

3.3. Risk of bias assessment

3.4. Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Comparison with Prior Works

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Practical Implications and Future Developments

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| AFEQT | Atrial Fibrillation Effect on Quality-of-Life |

| BMI | Body-mass index |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EQ-5D-5L | 5-level EuroQol EQ-5D |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HT | Hypertension |

| HRQoL | Health-related Quality-of-life |

| MCS | Mental component summary |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MLHFQ | Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| PCS | Physical component summary |

| PPG | Photoplethysmography |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| QoL | Quality-of-Life |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| SF-12 | 12-item Short-Form |

| SF-36 | 36-item Short-Form |

| TM | Telemonitoring |

| TTE | Transthoracic echocardiogram |

| UC | Usual care |

References

- Kuan, P.X.; Chan, W.K.; Ying, D.K.F.; Rahman, M.A.A.; Peariasamy, K.M.; Lai, N.M.; Mills, N.L.; Anand, A. Efficacy of telemedicine for the management of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Digital Health 2022, 4, e676–e691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashshur, R.L. On the definition and evaluation of telemedicine. Telemedicine Journal 1995, 1, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebolledo Del Toro, M.; Herrera Leaño, N.M.; Barahona-Correa, J.E.; Muñoz Velandia, O.M.; Fernández Ávila, D.G.; García Peña, Á.A. Effectiveness of mobile telemonitoring applications in heart failure patients: Systematic review of literature and meta-analysis. Heart Failure Reviews 2023, 28, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leo, D.G.; Buckley, B.J.R.; Chowdhury, M.; Harrison, S.L.; Isanejad, M.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Wright, D.J.; Lane, D.A. Interactive Remote Patient Monitoring Devices for Managing Chronic Health Conditions: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 2022, 24, e35508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles, T.D.; Berk, B.C.; Black, H.R.; Cohn, J.N.; Kostis, J.B.; Izzo, J.L., Jr.; Weber, M.A. Expanding the definition and classification of hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2005, 7, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, B.; Coats, A.J.; Tsutsui, H.; Abdelhamid, C.M.; Adamopoulos, S.; Albert, N.; Anker, S.D.; Atherton, J.; Böhm, M.; Butler, J.; et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: A report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure. European Journal of Heart Failure 2021, 23, 352–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Celutkiene, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European Heart Journal 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; Fauchier, L.; Filippatos, G.; Kalman, J.M.; La Meir, M.; Lane, D.A.; Lebeau, J.P.; Lettino, M.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Pinto, F.J.; Thomas, G.N.; Valgimigli, M.; Van Gelder, I.C.; Van Putte, B.P.; Watkins, C.L.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 373–498. [Google Scholar]

- KÄdzierski, K.; Radziejewska, J.; SÅawuta, A.; WawrzyÅska, M.; Arkowski, J. Telemedicine in Cardiology: Modern Technologies to Improve Cardiovascular Patientsâ OutcomesâA Narrative Review. Medicina 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, G.B.; Venegas-Vera, A.V.; Lerma, E.V. Utility of telemedicine in the COVID-19 era. Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine 2020, 21, 583–587. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, P.; Sianis, A.; Brown, J.; Ali, A.; Briasoulis, A. Chronic disease management in heart failure: Focus on telemedicine and remote monitoring. Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine 2021, 22, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.S.; Kim, N.S.; Kim, A.Y.; Woo, H.S. Nurse-Coordinated Blood Pressure Telemonitoring for Urban Hypertensive Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbuDagga, A.; Resnick, H.E.; Alwan, M. Impact of blood pressure telemonitoring on hypertension outcomes: A literature review. Telemed J E Health 2010, 16, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Xie, Z.; Dong, F.; Wu, Z.; Lin, Z.; Sun, N.; Xu, J. Effectiveness of home blood pressure telemonitoring: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. J Hum Hypertens 2017, 31, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nick, J.M.; Roberts, L.R.; Petersen, A.B. Effectiveness of telemonitoring on self-care behaviors among community-dwelling adults with heart failure: A quantitative systematic review. JBI Evid Synth 2021, 19, 2659–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strandberg, S.; Backåberg, S.; Fagerström, C.; Ekstedt, M. Self-care management and experiences of using telemonitoring as support when living with hypertension or heart failure: A descriptive qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances 2023, 5, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Telemedicine for healthcare: Capabilities, features, barriers, and applications. Sensors International 2021, 2, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciampi, M.; Sicuranza, M.; Silvestri, S. A Privacy-Preserving and Standard-Based Architecture for Secondary Use of Clinical Data. Information 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, S.; Islam, S.; Amelin, D.; Weiler, G.; Papastergiou, S.; Ciampi, M. Cyber threat assessment and management for securing healthcare ecosystems using natural language processing. International Journal of Information Security 2024, 23, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, T.P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLOS Medicine 2009, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T.; Loder, E.W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; McGuinness, L.A.; Stewart, L.A.; Thomas, J.; Tricco, A.C.; Welch, V.A.; Whiting, P.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, https. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muka, T.; Glisic, M.; Milic, J.; Verhoog, S.; Bohlius, J.; Bramer, W.; Chowdhury, R.; Franco, O.H. A 24-step guide on how to design, conduct, and successfully publish a systematic review and meta-analysis in medical research. European Journal of Epidemiology 2020, 35, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ãlvarez Hernández, S.; Castillo, D.; Villa-Vicente, J.G.; Yanci, J.; Marqués-Jiménez, D.; Rodrà guez-Fernández, A. Analyses of Physical and Physiological Responses during Competition in Para-Footballers with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2007, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, D.M.; Chen, J.; Chunara, R.; Testa, P.A.; Nov, O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: Evidence from the field. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2020, 27, 1132–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omboni, S.; Padwal, R.S.; Alessa, T.; Benczúr, B.; Green, B.B.; Hubbard, I.; Kario, K.; Khan, N.A.; Konradi, A.; Logan, A.G.; Lu, Y.; Mars, M.; McManus, R.J.; Melville, S.; Neumann, C.L.; Parati, G.; Renna, N.F.; Ryvlin, P.; Saner, H.; Schutte, A.E.; Wang, J. The worldwide impact of telemedicine during COVID-19: Current evidence and recommendations for the future. Connect Health 2022, 1, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hincapié, M.A.; Gallego, J.C.; Gempeler, A.; Piñeros, J.A.; Nasner, D.; Escobar, M.F. Implementation and Usefulness of Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health 2020, 11, 2150132720980612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; Emberson, J.R.; Hernán, M.A.; Hopewell, S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Junqueira, D.R.; Jüni, P.; Kirkham, J.J.; Lasserson, T.; Li, T.; McAleenan, A.; Reeves, B.C.; Shepperd, S.; Shrier, I.; Stewart, L.A.; Tilling, K.; White, I.R.; Whiting, P.F.; Higgins, J.P.T. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, https. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Francesco, F.; Lanza, A.; Di Blasio, M.; Vaienti, B.; Cafferata, E.A.; Cervino, G.; Cicciù, M.; Minervini, G. Application of Botulinum Toxin in Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, U.; Nilsson, P.M.; Kjellgren, K.; Hoffmann, M.; Wennersten, A.; Midlöv, P. PERson-centredness in Hypertension management using Information Technology: A randomized controlled trial in primary care. J Hypertens 2023, 41, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgi, A.; Hosseini, H.; Eftekhar, H.; Majdzadeh, R.; Yoonessi, A.; Ramezankhani, A.; Mansouri, M.; Ashoorkhani, M. The effect of the mobile "blood pressure management application" on hypertension self-management enhancement: A randomized controlled trial. Trials 2021, 22, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.Y.; Park, J.S.; Min, D.L.; Ahn, S.; Ahn, J.A. Heart Failure-Smart Life: A randomized controlled trial of a mobile app for self-management in patients with heart failure. BMC CARDIOVASCULAR DISORDERS 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cichosz, S.L.; Udsen, F.W.; Hejlesen, O. The impact of telehealth care on health-related quality of life of patients with heart failure: Results from the Danish TeleCare North heart failure trial. J Telemed Telecare 2020, 26, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clays, E.; Puddu, P.E.; LuÅ¡trek, M.; Pioggia, G.; Derboven, J.; Vrana, M.; De Sutter, J.; Le Donne, R.; Baert, A.; Bohanec, M.; Ciancarelli, M.C.; Dawodu, A.A.; De Pauw, M.; De Smedt, D.; Marino, F.; Pardaens, S.; Schiariti, M.S.; ValiÄ, J.; Vanderheyden, M.; Vodopija, A.; Tartarisco, G. Proof-of-concept trial results of the HeartMan mobile personal health system for self-management in congestive heart failure. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Jayasena, R.; Chen, S.H.; Maiorana, A.; Dowling, A.; Layland, J.; Good, N.; Karunanithi, M.; Edwards, I. The Effects of Telemonitoring on Patient Compliance With Self-Management Recommendations and Outcomes of the Innovative Telemonitoring Enhanced Care Program for Chronic Heart Failure: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res 2020, 22, e17559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwairej, L.; Ahmad, M. Hypertension and mobile application for self-care, self-efficacy and related knowledge. Health Educ Res 2022, 37, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeazarra, L.; Pereira, J.; Saracho, R. TensioBot: A Chatbot Assistant for Self-Managed in-House Blood Pressure Checking. J Med Syst 2021, 45, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Lane, D.A.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Wen, J.; Xing, Y.; Wu, F.; Xia, Y.; Liu, T.; Liang, Z.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Guo, J.; Burnside, G.; Chen, Y.; Lip, G.Y.H. Mobile Health Technology to Improve Care for Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 75, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Koh, K.W.L.; Ramachandran, H.J.; Nguyen, H.D.; Lim, S.; Tay, Y.K.; Shorey, S.; Wang, W. The effectiveness of a nurse-led home-based heart failure self-management programme (the HOM-HEMP) for patients with chronic heart failure: A three-arm stratified randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2021, 122, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, J.; Stengel, A.; Hofmann, T.; Wegscheider, K.; Koehler, K.; Sehner, S.; Rose, M.; Deckwart, O.; Anker, S.D.; Koehler, F.; Laufs, U. Telemonitoring in patients with chronic heart failure and moderate depressed symptoms: Results of the Telemedical Interventional Monitoring in Heart Failure (TIM-HF) study. Eur J Heart Fail 2021, 23, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaridis, C.; Bakogiannis, C.; Mouselimis, D.; Tsarouchas, A.; Antoniadis, A.P.; Triantafyllou, K.; Fragakis, N.; Vassilikos, V.P. The usability and effect of an mHealth disease management platform on the quality of life of patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation - The emPOWERD-AF study. Health Informatics J 2022, 28, 14604582221139053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leupold, F.; Karimzadeh, A.; Breitkreuz, T.; Draht, F.; Klidis, K.; Grobe, T.; Weltermann, B. Digital redesign of hypertension management with practice and patient apps for blood pressure control (PIA study): A cluster-randomised controlled trial in general practices. ECLINICALMEDICINE 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Song, T.; Yu, P.; Deng, N.; Guan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Y. Efficacy of an mHealth App to Support Patients’ Self-Management of Hypertension: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res 2023, 25, e43809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, G.M.; Modrow, M.F.; Schmid, C.H.; Sigona, K.; Nah, G.; Yang, J.; Chu, T.C.; Joyce, S.; Gettabecha, S.; Ogomori, K.; Yang, V.; Butcher, X.; Hills, M.T.; McCall, D.; Sciarappa, K.; Sim, I.; Pletcher, M.J.; Olgin, J.E. Individualized Studies of Triggers of Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation: The I-STOP-AFib Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiology 2022, 7, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus, R.J.; Little, P.; Stuart, B.; Morton, K.; Raftery, J.; Kelly, J.; Bradbury, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, S.; Murray, E.; May, C.R.; Mair, F.S.; Michie, S.; Smith, P.; Band, R.; Ogburn, E.; Allen, J.; Rice, C.; Nuttall, J.; Williams, B.; Yardley, L. Home and Online Management and Evaluation of Blood Pressure (HOME BP) using a digital intervention in poorly controlled hypertension: Randomised controlled trial. Bmj 2021, 372, m4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, W.W.; Bai, Y.Y.; Yan, L.; Zheng, W.; Zeng, Q.; Zheng, Y.S.; Zha, L.; Pi, H.Y.; Sai, X.Y. Effect of Home Blood Pressure Telemonitoring Plus Additional Support on Blood Pressure Control: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Biomed Environ Sci 2023, 36, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlin, D.; Rezanezad, B.; Edvinsson, M.L.; Bachus, E.; Melander, O.; Gerward, S. Self-care Management Intervention in Heart Failure (SMART-HF): A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. J Card Fail 2022, 28, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upshaw, J.N.; Parker, S.; Gregory, D.; Koethe, B.; Vest, A.R.; Patel, A.R.; Kiernan, M.S.; DeNofrio, D.; Davidson, E.; Mohanty, S.; Arpin, P.; Strauss, N.; Sommer, C.; Brandon, L.; Butler, R.; Dwaah, H.; Nadeau, H.; Cantor, M.; Konstam, M.A. The effect of tablet computer-based telemonitoring added to an established telephone disease management program on heart failure hospitalizations: The Specialized Primary and Networked Care in Heart Failure (SPAN-CHF) III Randomized Controlled Trial. Am Heart J 2023, 260, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanicelli, L.M.; Goy, C.B.; González, V.D.C.; Palacios, G.N.; Martà nez, E.C.; Herrera, M.C. Non-invasive home telemonitoring system for heart failure patients: A randomized clinical trial. J Telemed Telecare 2021, 27, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuting, Z.; Xiaodong, T.; Qun, W. Effectiveness of a mHealth intervention on hypertension control in a low-resource rural setting: A randomized clinical trial. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1049396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Thompson, J.; Rahmani, J.; Bhagavathula, A.S.; Xu, X.; Luo, J. Feedback based on health advice via tracing bracelet and smartphone in the management of blood pressure among hypertensive patients: A community-based RCT trial in Chongqing, China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e29346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, Jr, J. E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; Janssen, M.F.; Kind, P.; Parkin, D.; Bonsel, G.; Badia, X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Quality of Life Research 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rector, T.S.; Cohn, J.N. Assessment of patient outcome with the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire: Reliability and validity during a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pimobendan. Pimobendan Multicenter Research Group. Am Heart J 1992, 124, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spertus, J.; Dorian, P.; Bubien, R.; Lewis, S.; Godejohn, D.; Reynolds, M.R.; Lakkireddy, D.R.; Wimmer, A.P.; Bhandari, A.; Burk, C. Development and Validation of the Atrial Fibrillation Effect on QualiTy-of-Life (AFEQT) Questionnaire in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 2011, 4, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, Jr, J. ; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höfer, S.; Lim, L.; Guyatt, G.; Oldridge, N. The MacNew Heart Disease health-related quality of life instrument: A summary. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2004, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiou, G.S.; Palatini, P.; Parati, G.; O’Brien, E.; Januszewicz, A.; Lurbe, E.; Persu, A.; Mancia, G.; Kreutz, R.; on behalf of the European Society of Hypertension Council and the European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring and Cardiovascular Variability. 2021 European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for office and out-of-office blood pressure measurement. Journal of Hypertension 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.D.; Saval, M.A.; Robbins, J.L.; Ellestad, M.H.; Gottlieb, S.S.; Handberg, E.M.; Zhou, Y.; Chandler, B.; HF-ACTION Investigators. New York Heart Association functional class predicts exercise parameters in the current era. Am Heart J 2009, 158, S24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 |

| Study | Intervention / comparator (patients) | Mean age in years (SD), men (%) | Follow-up, patients after | Outcomes | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersson et al., 2023, Sweden [30] | Web-based TM system (482); UC (467) | I: 62.8 (9.8), 283 (58.7); C: 63.0 (10.0), 259 (55.5) at baseline | 12 months; I: 442, C: 420 | % patients with a controlled BP | Positive effect, with uncertain long-term effect |

| Bozorgi et al., 2021, Iran [31] | Mobile app (60); UC (60) | I: 52.0 (8.1), 35 (58.3); C: 51.6 (9.4), 36 (60.0) at baseline | 24 weeks; I: 58, C: 60 | Adherence to treatment; adherence to DASH diet, regular monitoring of BP, physical activity | Positive effect |

| Dwairej et al., 2022, Jordan [36] | Mobile app (75); UC (75) | I: 50.0 (7.3), 32 (56.1); C: 51.0 (5.1), 31 (52.5) after follow-up | 8 weeks; I: 57, C: 59 | Self-care, self-efficacy, knowledge, % patients with a controlled BP | Positive effect |

| Echeazarra et al., 2021, Spain [37] | Telegram chatbot (55); UC (57) | I: 50.2, 32 (58.2); C: 53.9, 33 (57.9) at baseline | 24 months; 88 | Adherence to checking schedule, knowledge and skills on BP checking best practices, satisfaction with intervention | No change on adherence, positive effect on knowledge and skills |

| Leupold et al., 2023, Germany [42] | Patient app connected with a practice management centre (331); UC (305) | I: 56.9 (8.7), 181 (54.7); C: 59.2 (9.7), 154 (50.5) at baseline | 6 months; I: 311, C: 305 | BP control rate, BP changes, satisfaction with intervention | Positive effect |

| Liu et al., 2023, China [43] | Mobile app (148); UC (149) | I: 48.58 (9.54), 78 (52.7); C: 50.64 (8.72), 70 (47) at baseline | 6 months; I: 111, C: 115 | BP control rate, knowledge, changes in lifestyle behavior, blood glucose levels, blood lipid levels, waist-hip ratio, BMI | Positive effect |

| McManus et al., 2021, UK [45] | Self monitoring of BP (305); UC (317) | I: 65.2 (10.3), 160 (52.46); C: 66.7 (10.2), 174 (54.89) at baseline | 12 months; I: 271, C: 282 | Change in BP, drug adherence, HRQoL (EQ-5D-5L) | Positive effect |

| Meng et al., 2023, China [46] | Smart device and a mobile app (95); UC (95) | I: 50.96 (10.50), 50 (59.5); C: 51.45 (12.22), 51 (58.0) after follow-up | 12 weeks; I: 84, C: 88 | BP reduction, % patients achieving the target BP | Positive effect |

| Yuting et al., 2023, China [50] | Smart device and a mobile app (74); UC (74) | I: 61.37 (11.73), 45 (68.18); C: 62.09 (10.66), 38 (55.88) after follow-up | 12 weeks; I: 66, C: 68 | Change in BP, in waist and hip circumference, height and weight; HT adherence, change in self-efficacy and QoL (SF-12) | No change in diastolic BP, positive effect on diastolic BP, HT compliance, mental health |

| Zhang et al., 2022, China [51] | Smart device and a mobile app (164); UC (143) | I: 56.7 (9.3), 44 (42.3); C: 62.6 (10.1), 31 (35.2) after follow-up | 6 months; I: 104, C: 88 | Reduction in BP and weight | Positive effect |

| Study | Intervention / comparator (patients) | Mean age in years (SD), men (%) | Follow-up, patients after follow-up | Outcomes | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guo et al., 2020, China [38] | Mobile app (1786); UC (1842) | I: 67.0 (15.0), 1021 (62.0); C: 70.0 (12.0), 1041 (62.0) after follow-up | 286 days (mean); I: 1646, C: 1678 | Composite of stroke / thromboembolism, all-cause death, hospitalization | Positive effect |

| Lazaridis et al., 2022, Greece [41] | Mobile app (40); Limited version of the app (40) | I: 58.8 (7.9), 27 (68); C: 57.5 (9.4), 26 (65) at baseline | 6 months; I: 40, C: 40 | QoL (AFEQT, EQ-5D-5L) | Positive effect |

| Marcus et al., 2021, USA [44] | Trigger testing with a mobile app (251); Monitoring only with a mobile app (248) | I: 58 (14), 149 (59); C: 58 (14), 140 (56) at baseline | 10 weeks; I: 136, C: 184 | QoL (AFEQT) | No change |

| Study | Intervention / comparator (patients) | Mean age in years (SD), men (%) | Follow-up, patients after follow-up | Outcomes | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi et al., 2023, South Korea [32] | Mobile app (38); UC (38) | I: 70.31 (10.55), 19 (52.8); C: 79.42 (7.59), 16 (42.1) after follow-up | 3 months; I: 36, C: 38 | Differences in BMI, waist circumference, BP, NYHA functional classes [59], TTE, depression, QoL (MacNew), medication adherence | Positive effect on physical factors, no change in psychosocial and behavioral factors |

| Cichosz et al., 2020, Denmark [33] | Tablet and smart devices (145); UC (154) | I: 70, 83 (57.24); C: 69, 79 (51.3) | 12 months; I: 93, C: 100 | Change in HRQoL (SF-36) | Positive effect on MCS, no change on PCS |

| Clays et al., 2021, Belgium & Italy [34] | Smart devices (38); UC (23) | I: 61.8 (11.0), 26 (76.47); C: 65.2 (9.6), 17 (77.27) after follow-up | 6 months; I: 34, C: 22 | Change in HRQoL (MLHFQ), self-management, exercise capacity, illness perception, mental and sexual health | Further studies required |

| Ding et al., 2020, Australia [35] | Smart devices (91); UC (93) | I: 69.5 (12.3), 66 (73); C: 70.8 (12.4), 75 (81) at baseline | 6 months; I: 67, C: 81 | Patient compliance with self-monitoring | Positive effect |

| Jiang et al., 2021, Singapore [39] | A: toolkit for self-care (71); B: additional mobile app (70); C: UC (72) | A: 69.08 (10.51), 35 (71.4); B: 66.82 (11.81), 40 (70.2); C: 68.82 (13.14), 37 (66.1) after follow-up | 6 months; A: 49, B: 57, C: 56 | HF self-care, cardiac self-efficacy, anxiety and depression, HRQoL (MLHFQ), perceived social support | Positive effect |

| Koehler et al., 2020, Germany [40] | Smart devices (339); UC (335) | I: 67.13 (10.92), 272 (80.2); C: 66.88 (10.56), 276 (82.4) at baseline | 24 months; I: 198, C: 210 | Change in depression and HRQoL (SF-36) | Positive effect |

| Sahlin et al., 2022, Sweden [47] | Home-based medical device (62); UC (62) | I: 80 (8), 39 (67.24); C: 77 (11), 32 (53.3) after follow-up | 240 days; I: 58, C: 60 | HF self-care, # HF-related in-hospital days | Positive effect |

| Upshaw et al., 2023, USA [48] | Remote monitoring of parameters and symptoms via a tablet (159); telephone-based management (53) | I: 68, 115 (72); C: 74, 35 (66) at baseline | 90 days; I: 156, C: 52 | # days hospitalized for HF | Further studies required |

| Yanicelli et al., 2020, Argentina [49] | Mobile app (20); UC (20) | 52 y.o., I: 14 (93); C: 10 (66) after follow-up | 90 days; I: 15, C: 15 | Change in HF self-care, treatment adherence, re-hospitalizion | Positive effect |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).