Submitted:

06 August 2024

Posted:

08 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Material

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Dry Matter

2.2.2. In Vitro Digestion

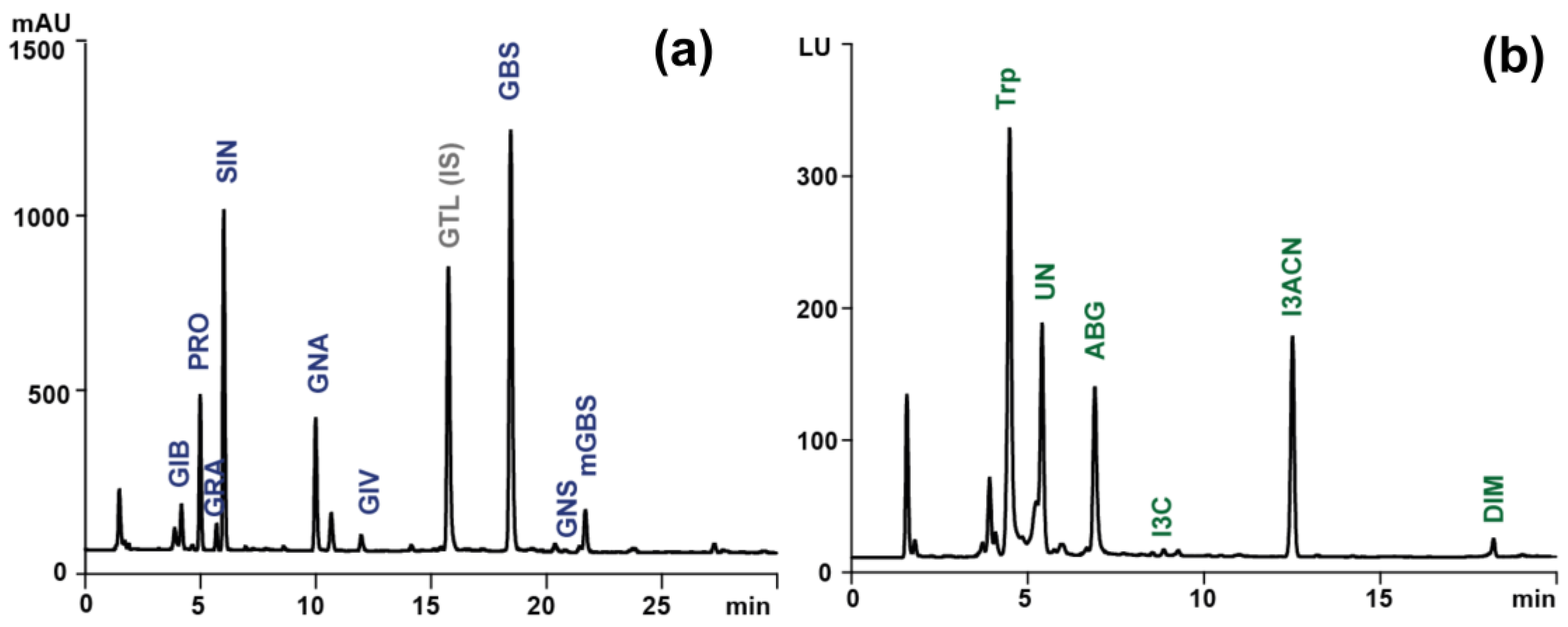

2.2.3. Determination of Glucosinolates

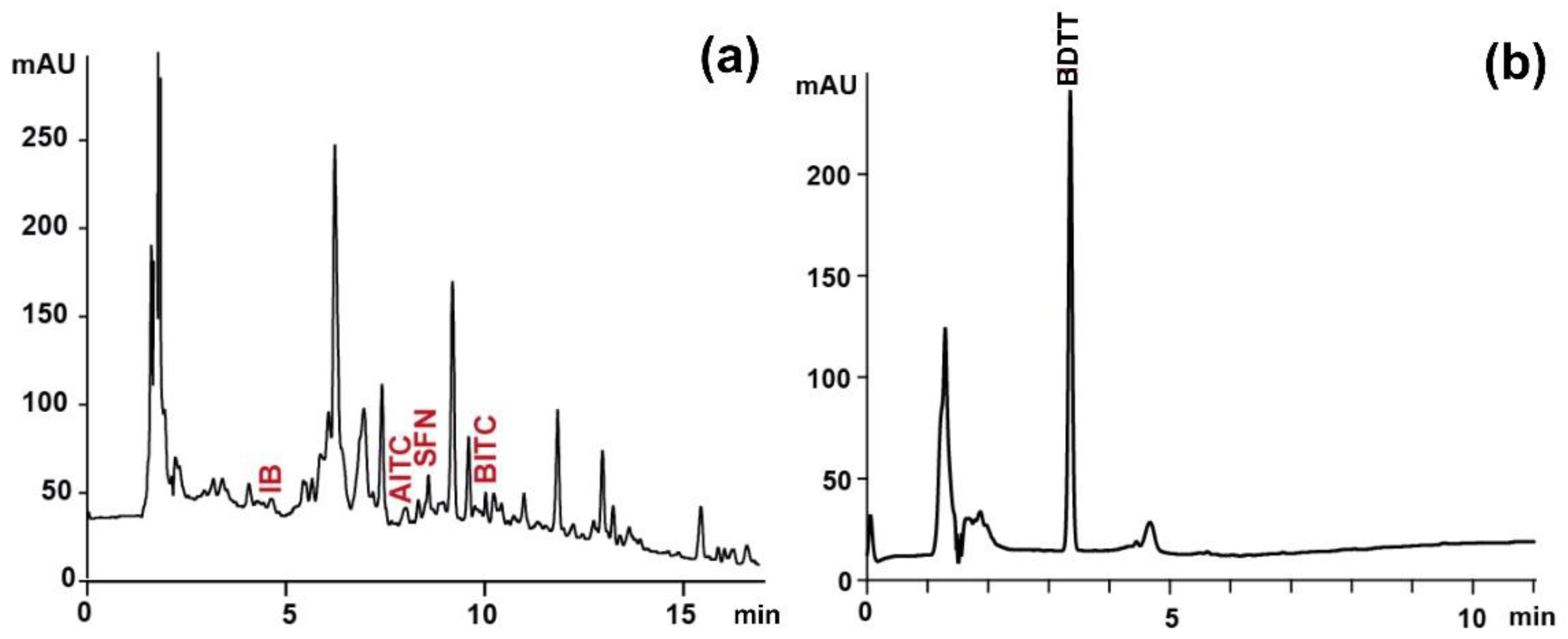

2.2.4. Determination of Indoles and Isothiocyanates

2.2.5. Bioaccessibility

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

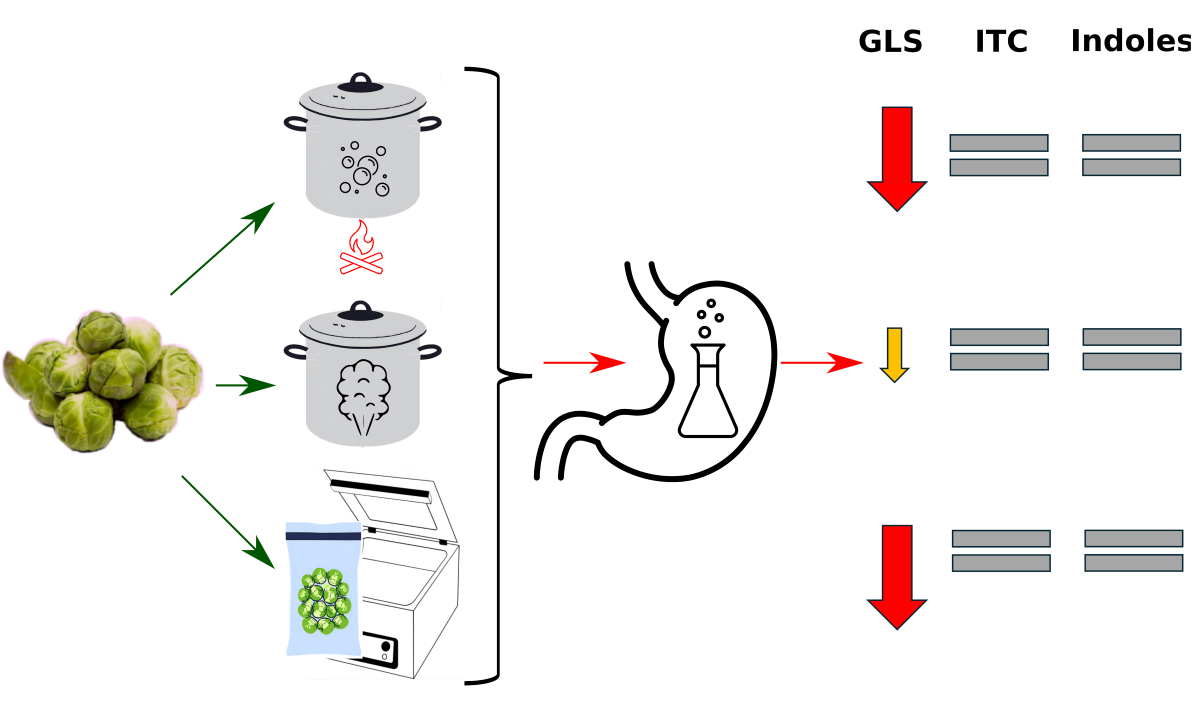

4.1. Stability of Glucosinolates and Its Metabolites during Thermal Processing

4.2. Bioaccessibility of Phytochemicals after In Vitro Digestion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hwang, E.-S.; Bornhorst, G.M.; Oteiza, P.I.; Mitchell, A.E. Assessing the fate and bioavailability of glucosinolates in kale (Brassica oleracea) using simulated human digestion and caco-2 cell uptake models. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 9492–9500. [CrossRef]

- Kuljarachanan, T.; Fu N.; Chiewchan, N.; Devahastin, S.; Chen, X.D. Evolution of important glucosinolates in three common Brassica vegetables during their processing into vegetable powder and in vitro gastric digestion. Food Funct. 2020, 11(1), 211-220.

- Vancoillie, F.; Verkempinck, S.H.E.; Sluys, L.; De Mazière, S.; Van Poucke, C.; Hendrickx, M.E.; Van Loey, A.M.; Grauwet, T. Stability and bioaccessibility of micronutrients and phytochemicals present in processed leek and Brussels sprouts during static in vitro digestion. Food Chem. 2024, 445, 138644.

- Doniec, J.; Florkiewicz, A.; Duliński, R.; Filipiak-Florkiewicz, A. Impact of Hydrothermal Treatments on Nutritional Value and Mineral Bioaccessibility of Brussels Sprouts (Brassica oleracea var. gemmifera). Molecules 2022, 27, 1861. [CrossRef]

- Doniec, J.; Pierzchalska, M.; Mickowska, B.; Grabacka, M. The in vitro digestates from Brussels sprouts processed with various hydrothermal treatments affect the intestinal epithelial cell differentiation, mitochondrial polarization and glutathione level. AFSci 2023, 32, 3, 154–165. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Castro, J.; De Haro-Bailón, A.; Obregón-Cano, S.; García Magdaleno, I.M.; Moreno Ortega, A.; Cámara-Martos, F. Bioaccessibility of glucosinolates, isothiocyanates and inorganic micronutrients in cruciferous vegetables through INFOGEST static in vitro digestion model. Food Res. Int. 2023, 166, 112598. [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, M.N.; Drabińska, N.; Jeleń, H.H. Thermal processing-induced changes in volatilome and metabolome of Brussels sprouts: focus on glucosinolate metabolism. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 2165–2174. [CrossRef]

- .

- Żyła, K.; Ledoux, D.R.; Garcia, A.; Veum, T.L. An in vitro procedure for studying enzymic dephosphorylation of phytate in maize-soya bean feeds for turkey poults. Br. J. Nutr. 1995, 74, 3–17.

- Starzyńska-Janiszewska, A.; Dulinski, R.; Stodolak, B.; Mickowska, B.; Wikiera, A. Prolonged tempe-type fermentation in order to improve bioactive potential and nutritional parameters of quinoa seeds. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 71, 116–121. [CrossRef]

- 11. ISO 9167-1:1992. Rapeseed. Determination of glucosinolates content. Part 1: Method using high-performance liquid chromatography. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland, 1992.

- Kusznierewicz, B.; Iori, R.; Piekarska, A.; Namieśnik, J.; Bartoszek, A. Convenient identification of desulfoglucosinolates on the basis of mass spectra obtained during liquid chromatography–diode array–electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry analysis: Method verification for sprouts of different Brassicaceae species extracts. J. Chrom. A. 2013, 1278, 108-115. [CrossRef]

- Seljåsen, R.; Kusznierewicz, B.; Bartoszek, A.; Mølmann, J.; Vågen, I.M. Effects of post-harvest elicitor treatments with ultrasound, UV- and photosynthetic active radiation on polyphenols, glucosinolates and antioxidant activity in a waste fraction of white cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata). Molecules 2022, 27, 5256.

- Pilipczuk, T.; Dawidowska, N.; Kusznierewicz, B.; Namieśnik, J.; Bartoszek, A. Simultaneous determination of indolic compounds in plant extracts by solid-phase extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography with UV and fluorescence detection. Food Anal. Method. 2015, 8, 2169–2177. [CrossRef]

- Pilipczuk, T.; Kusznierewicz, B.; Chmiel, T.; Przychodzeń, W.; Bartoszek, A. Simultaneous determination of individual isothiocyanates in plant samples by HPLC-DAD-MS following SPE and derivatization with N-acetyl-l-cysteine. Food Chem. 2017, 214, 587-596. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Massih, R.M.; Debs, E., Othman, L.; Attieh, J.; Cabrerizo, F.M. Glucosinolates, a natural chemical arsenal: More to tell than the myrosinase story. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1130208. [CrossRef]

- Cámara-Martos, F.; Obregón-Cano, S.; Mesa-Plata, O.; Cartea-González, M.E.; De Haro-Bailón, A. Quantification and in vitro bioaccessibility of glucosinolates and trace elements in Brassicaceae leafy vegetables. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 127860. [CrossRef]

- Ciska, E.; Drabińska, N.; Honke, J.; Narwojsz, A. Boiled Brussels sprouts: A rich source of glucosinolates and the corresponding nitriles. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 91–99. [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.E. Indoles derived from glucobrassicin: cancer chemoprevention by Indole-3-carbinol and 3,3’-diindolylmethane. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 734334. [CrossRef]

- Florkiewicz, A.; Ciska, E.; Filipiak-Florkiewicz, A.; Topolska, K. Comparison of Sous-vide methods and traditional hydrothermal treatment on GLS content in Brassica vegetables. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2017, 243, 1507–1517. [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Nikmaram, N.; Roohinejad, S.; Khelfa, A.; Zhu, Z.; Koubaa, M. Bioavailability of Glucosinolates and Their Breakdown Products: Impact of Processing. Front. Nutr. 2016, 16, 3-24. [CrossRef]

- Oliviero, T.; Verkerk, R.; Dekker, M. Isothiocyanates from Brassica Vegetables - effects of processing, cooking, mastication, and digestion. Molecular Nutrition Food Res. 2018, 62, 1701069.

- Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Pang, X.; Tian, S.; Hu, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Lu, Y. The effect of processing and cooking on glucoraphanin and sulforaphane in brassica vegetables. Food Chem. 2021, 360, 130007. [CrossRef]

- Baenas, N.; Marhuenda, J.; García-Viguera, C.; Zafrilla, P.; Moreno, D. Influence of Cooking Methods on Glucosinolates and Isothiocyanates Content in Novel Cruciferous Foods. Foods 2019, 12, 8, 257. [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, F.; Gil-Izquierdo, A.; Pérez-Vicente, A.; García-Viguera, C. In vitro gastrointestinal digestion study of broccoli inflorescence phenolic compounds, glucosinolates, and vitamin C. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 135–138. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-León, A.M.; Fernández-León, M.F.; González-Gómez, D.; Ayuso, M.C.; Bernalte, M.J. Quantification and bioaccessibility of intact glucosinolates in broccoli ‘Parthenon’ and Savoy cabbage ‘Dama.’ J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017, 61, 40–46. [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, V.; Luciano, F.B.; Meca, G.; Ritieni, A.; Mañes, J. Bioaccessibility of glucoraphanin from broccoli using an in vitro gastrointestinal digestion model. CyTA – J. Food 2015, 13, 361–365.

- Rodríguez-Hernández, M.C.; Medina, S.; Gil-Izquierdo, A.; Martínez-Ballesta, M.C.; Moreno, D.A. Broccoli isothiocyanate content and in vitro availability according to variety and origin. Maced. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2013, 32(2), 251–264. [CrossRef]

- Abellán, Á.; Domínguez-Perles, R.; García-Viguera, C.; Moreno, D.A. Evidence on the Bioaccessibility of Glucosinolates and Breakdown Products of Cruciferous Sprouts by Simulated In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11046. [CrossRef]

| Compound Name | RT [min] | Molecular Formula | Precursor Ion (m/z) | Diagnostic Ions (m/z) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical | Experimental | Δm (ppm) | ||||

| Glucosinolates | [MDS-GLS-H] − | [MDS-GLS-H-162] − | ||||

| Glucoiberin (GIB) | 3.9 | C11H21NO10S3 | 342.068123 | 342.068329 | 0.60 | 180.016 [C5H10NO2S2]− |

| Progoitrin (PRO) | 4.2 | C11H19NO10S2 | 308.080401 | 308.080780 | 1.23 | 146.027 [C5H8NO2S] − |

| Glucoraphanin (GRA) | 5.7 | C12H23NO10S3 | 356.083772 | 356.084106 | 0.94 | 194.030 [C6H12NO2S2] − |

| Sinigrin (SIN) | 5.9 | C10H17NO9S2 | 278.069836 | 278.070099 | 0.95 | 116.016 [C4H6NOS]− |

| Gluconapin (GNA) | 9.9 | C11H19NO9S2 | 292.085486 | 292.085937 | 1.54 | 130.032 [C5H8NOS]− |

| Glucoiberverin (GIV) | 11.9 | C11H21NO9S3 | 326.073208 | 326.073547 | 1.04 | 164.020 [C5H10NOS2] − |

| Glucobrassicin (GBS) | 18.4 | C16H20N2O9S2 | 367.096385 | 367.096558 | 0.47 | 205.043 [C10H9N2OS] − |

| Gluconasturtiin (GNS) | 21.4 | C15H21NO9S2 | 342.101136 | 342.101471 | 0.98 | 180.048 [C9H10NOS] − |

| Methoxyglucobrassicin (metGBS) | 21.7 | C17H22N2O10S2 | 397.106950 | 397.106735 | 0.54 | 235.054 [C11H11N2O2S]− |

| Isothiocyanates | [MNAC-ITC+H]+ | [MNAC-ITC+H-NAC]+ | ||||

| Iberin (IB) | 4.6 | C5H9NOS2 | 327.050699 | 327.049974 | 2.22 | 164.017 [C5H10NOS2]+ |

| Allyl-ITC (AITC) | 7.2 | C4H5NS | 263.052412 | 263.051697 | 2.72 | 100.022 [C4H6NS]+ |

| Sulforaphane (SFN) | 7.7 | C6H11NOS2 | 341.066349 | 341.065643 | 2.07 | 178.035 [C6H12NOS2] + |

| 3-Butenyl-ITC (BITC) | 8.9 | C5H7NS | 277.068062 | 277.0674438 | 2.23 | 114.037 [C5H8NS] + |

| Indoles | [M+H]+ | |||||

| Tryptophan (Trp) | 4.5 | C11H12N2O2 | 205.097703 | 205.097107 | 2.91 | 118.065 [C8H8N]+, 146.060 [C9H8NO]+ |

| Unknown (UN) | 5.4 | C14H15NO4 | 262.107934 | 262.107330 | 2.30 | 130.065 [C9H8N]+, 118.065 [C8H8N]+ |

| Ascorbigen (ABG) | 6.9 | C15H15NO6 | 306.097764 | 306.096924 | 2.74 | 130.065 [C9H8N]+ |

| Indole-3-carbinol (I3C) | 8.8 | C9H9NO | 148.076239 | 148.0765378 | 2.02 | 130.065 [C9H8N]+, 118.065 [C8H8N]+ |

| 3-Indoleacetonitrile (I3ACN) | 12.5 | C10H8N2 | 157.076573 | - | - | - |

| 3,3'-Diindolylmethane (DIM) | 18.2 | C17H14N2 | 247.123523 | - | - | - |

| Content [µmol/g d.w.] (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Raw (R) | Sous vide (SV) | Steam (S) | Boiled (B) | Sous vide-digested (SV-D) | Steam-digested (S-D) | Boiled-digested (B-D) |

| Glucosinolates | |||||||

| GIB* | 0.736ab ± 0.016 | 0.674a ± 0.036 | 0.774b ± 0.025 | 0.861c ± 0.032 | 0.183d ± 0.012 | 0.162d ± 0.002 | 0.080e ± 0.010 |

| PRO* | 2.162ab ± 0.193 | 1.639c ± 0.221 | 1.925ac ± 0.154 | 2.542b ± 0.293 | 0.088d ± 0.027 | 0.259d ± 0.012 | 0.278d ± 0.023 |

| GRA** | 0.295a ± 0.018 | 0.244a ± 0.03 | 0.352a ± 0.062 | 0.368a ± 0.045 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| SIN* | 4.779a ± 0.336 | 4.196a ± 0.451 | 4.495a ± 0.187 | 4.966a ± 0.443 | 0.398b ± 0.025 | 0.587b ± 0.019 | 1.070b ± 0.008 |

| GNA* | 2.795a ± 0.152 | 1.799b ± 0.196 | 2.235c ± 0.060 | 2.493ac ± 0.170 | 0.110d ± 0.023 | 0.520e ± 0.021 | 0.162de ± 0.007 |

| GIV** | 0.304ab ± 0.014 | 0.257a ± 0.021 | 0.381b ± 0.038 | 0.335ab ± 0.056 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| GBS* | 3.753a ± 0.059 | 4.074a ± 0.781 | 4.792ab ± 0.407 | 5.519b ± 0.398 | 0.352c ± 0.010 | 0.638c ± 0.007 | 0.100c ± 0.037 |

| GNS** | 0.119ab ± 0.015 | 0.076a ± 0.011 | 0.191b ± 0.046 | 0.107a ± 0.031 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| metGBS** | 0.105a ± 0.037 | 0.299b ± 0.031 | 0.444c ± 0.052 | 0.460c ± 0.057 | 0.120a ± 0.012 | 0.153a ± 0.021 | <LOD |

| Total* | 15.049ab ± 0.425 | 13.259a ± 1.670 | 15.589bc ± 0.446 | 17.651c ± 1.176 | 1.251d ± 0.023 | 2.319d ± 0.035 | 1.689d ± 0.032 |

| Isothiocyanates | |||||||

| Iberin | 0.298 ± 0.036 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ |

| Allyl iTC | 0.248 ± 0.007 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ |

| Sulforaphane | 0.035 ± 0.001 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ |

| 3-butenyl-ITC | 0.332 ± 0.025 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ |

| Total | 0.914 ± 0.019 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ |

| Isothiocyanates by Zhang method | |||||||

| Total ITC** | 0.899a ± 0.061 | 0.216abc ± 0.087 | 0.093abc ± 0.012 | 0.216abc ± 0.057 | 0.078abc ± 0.008 | 0.065bc ± 0.003 | 0.061bc ± 0.005 |

| Indoles | |||||||

| Trp** | 0.044a ± 0.003 | 0.033a ± 0.002 | 0.038a ± 0.006 | 0.036a ± 0.009 | 0.035a ± 0.007 | 0.042a ± 0.014 | 0.034a ± 0.001 |

| Unknown** | 0.021a ± 0.001 | 0.009ab ± 0.002 | 0.004ab ± 0.001 | 0.007ab ± 0.001 | 0.006ab ± 0.001 | 0.003ab ± 0.001 | 0.002b ± 0.001 |

| ABG** | 0.018 ± 0.001 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| I3C | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| I3ACN** | 0.025a ± 0.002 | 0.085ab ± 0.003 | 0.063ab ± 0.002 | 0.071ab ± 0.005 | 0.093b ± 0.003 | 0.067ab ± 0.011 | 0.071ab ± 0.014 |

| DIM | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Total* | 0.109a ± 0.007 | 0.128a ± 0.008 | 0.106a ± 0.007 | 0.115a ± 0.005 | 0.134a ± 0.010 | 0.114a ± 0.026 | 0.108a ± 0.015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).