Submitted:

06 August 2024

Posted:

07 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Asbestos and Asbestosis

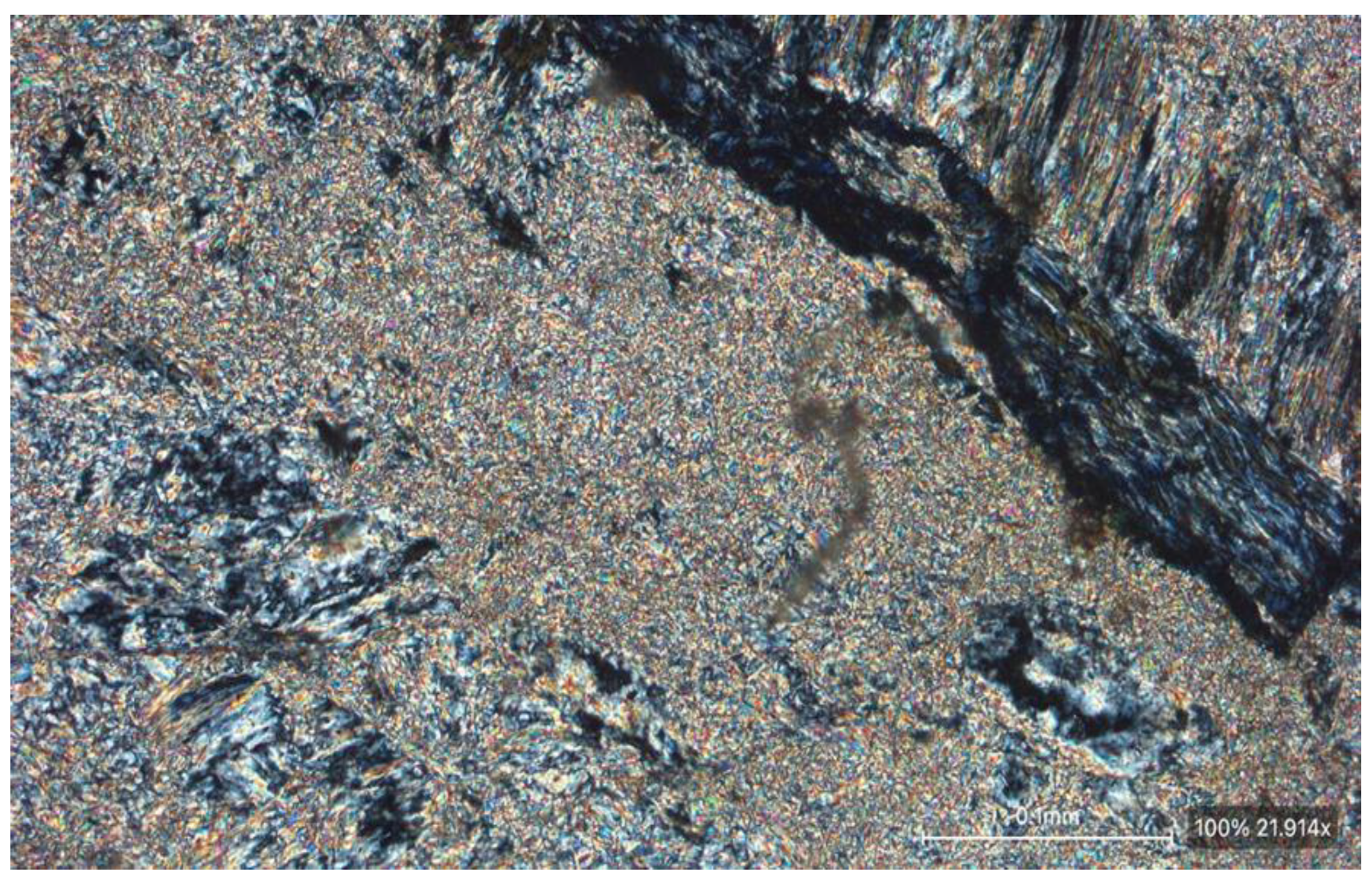

3.1. The Minerals

3.2. Clinical Features

3.3. Incidence in Population

3.4. Treatments

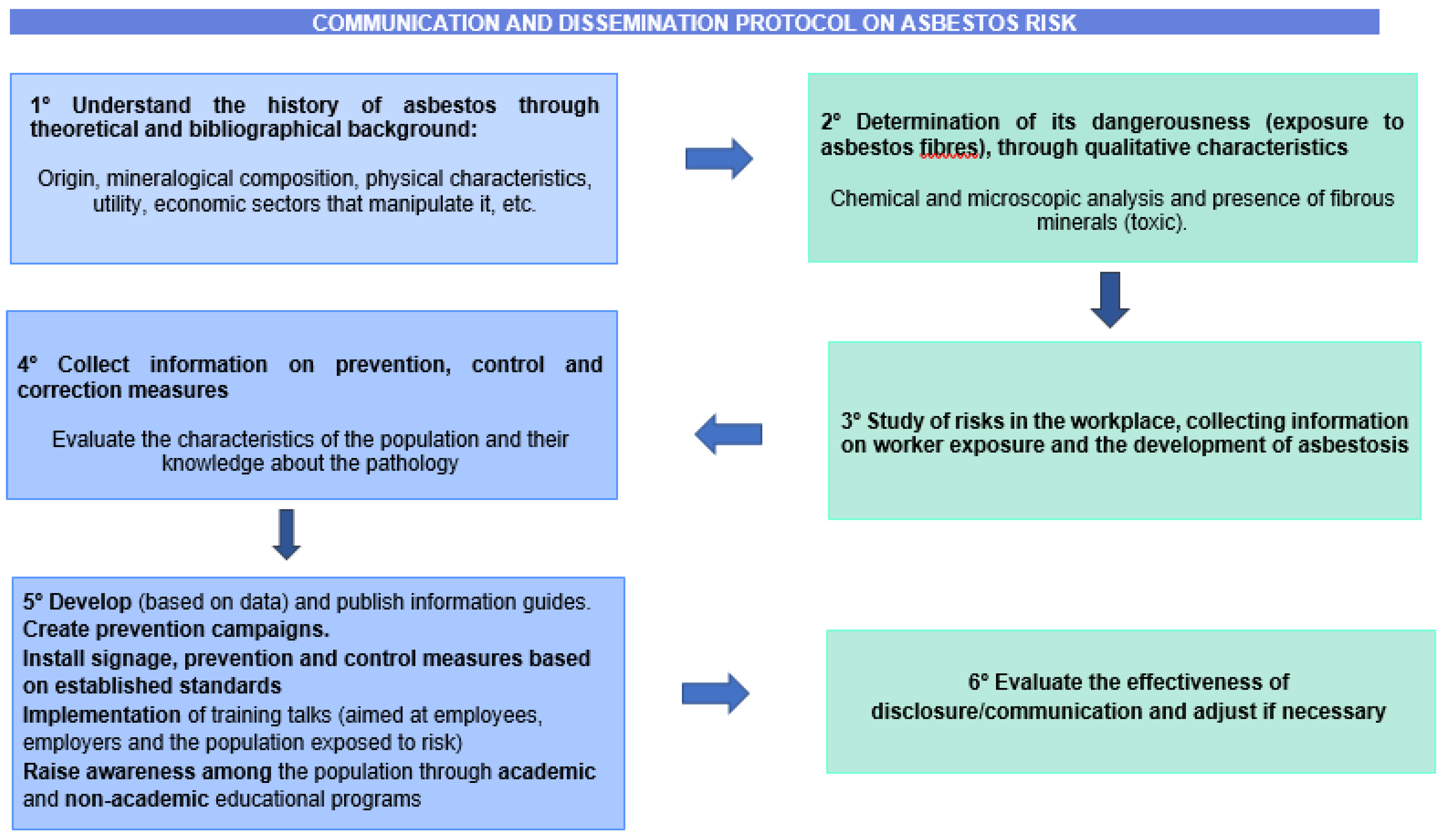

3.5. Prevention Measures: Communication and Education as the Best Way of Prevention

4. Discussion e Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Avataneo, C.; Petriglieri, J.R.; Capella, S.; Tomatis, M.; Luiso, M.; Marangoni, G.; Lazzari, E.; Tinazzi, S.; Lasagna, M.; De Luca, D.A.; et al. Chrysotile Asbestos Migration in Air from Contaminated Water: An Experimental Simulation. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 424, 127528. [CrossRef]

- Kjærheim, K.; Ulvestad, B.; Martinsen, J.I.; Andersen, A. Cancer of the Gastrointestinal Tract and Exposure to Asbestos in Drinking Water among Lighthouse Keepers (Norway). Cancer Causes Control 2005, 16, 593–598. [CrossRef]

- Bloise, A.; Ricchiuti, C.; Punturo, R.; Pereira, D. Potentially Toxic Elements (PTEs) Associated with Asbestos Chrysotile, Tremolite and Actinolite in the Calabria Region (Italy). Chemical Geology 2020, 558, 119896. [CrossRef]

- Bloise, A.; Barca, D.; Gualtieri, A.F.; Pollastri, S.; Belluso, E. Trace Elements in Hazardous Mineral Fibres. Environmental Pollution 2016, 216, 314–323. [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, A.F. Naturally Occurring Asbestos: A Global Health Concern? State of the Art and Open Issues. Environmental and Engineering Geoscience 2020, 26, 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Cralley, L.J.; Keenan, R.G.; Kupel, R.E.; Kinser, R.E.; Lynch, J.R. Characterization and Solubility of Metals Associated with Asbestos Fibers. American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal 1968, 29, 569–573. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.R.; Lowe, D.B.; Richards, D.E.; Cralley, L.J.; Stokinger, H.E. The Role of Trace Metals in Chemical Carcinogenesis: Asbestos Cancers. Cancer Res 1970, 30, 1068–1074.

- IARC Chemical Agents and Related Occupations; IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans / World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2012; ISBN 978-92-832-1323-9.

- Nemery, B. Metal Toxicity and the Respiratory Tract. European Respiratory Journal 1990, 3, 202–219. [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, A.L.; Williamson, S.H.; Hernandez, R.D.; Boyko, A.; Fledel-Alon, A.; York, T.L.; Polato, N.R.; Olsen, K.M.; Nielsen, R.; McCouch, S.R.; et al. Genome-Wide Patterns of Nucleotide Polymorphism in Domesticated Rice. PLoS Genet 2007, 3, 1745–1756. [CrossRef]

- Bloise, A.; Catalano, M.; Gualtieri, A. Effect of Grinding on Chrysotile, Amosite and Crocidolite and Implications for Thermal Treatment. Minerals 2018, 8, 135. [CrossRef]

- Bloise, A.; Belluso, E.; Critelli, T.; Catalano, M.; Apollaro, C.; Miriello, D.; Barrese, E. Amphibole Asbestos and Other Fibrous Minerals in the Meta-Basalt of the Gimigliano-Mount Reventino Unit (Calabria, South-Italy). Rendiconti Online della Società Geologica Italiana 2012, 847–848.

- Gualtieri, A.F. Mineral Fibres: Crystal Chemistry, Chemical-Physical Properties, Biological Interaction and Toxicity; European Mineralogical Union, 2017; ISBN 978-0-903056-65-6.

- Pereira, D.; Peinado, M.; Blanco, J.A.; Yenes, M. Geochemical Characterization of Serpentinites at Cabo Ortegal, Northwestern Spain. The Canadian Mineralogist 2008, 46, 317–327. [CrossRef]

- Feininger, T. Landmark Papers – Metamorphic Petrology.: Bernard W. Evans, Editor. Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 12 Baylis Mews, Amyand Park Road, Twickenham TW1 3HQ, United Kingdom. 2007, Viii + 332 Pages. £32. ISBN 978–0–903056–24–3. The Canadian Mineralogist 2009, 47, 980–981.

- Rivero Crespo, M.A.; Pereira Gómez, D.; Villa García, M.V.; Gallardo Amores, J.M.; Sánchez Escribano, V. Characterization of Serpentines from Different Regions by Transmission Electron Microscopy, X-Ray Diffraction, BET Specific Surface Area and Vibrational and Electronic Spectroscopy. Fibers 2019, 7, 47. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.; López, A.J.; Ramil, A.; Bloise, A. The Importance of Prevention When Working with Hazardous Materials in the Case of Serpentinite and Asbestos When Cleaning Monuments for Restoration. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 43. [CrossRef]

- IGME (Geological Survey of Spain) Available online: https://www.igme.es/.

- Navarro, R.; Pereira, D.; Gimeno, A.; Del Barrio, S. Caracterización mineralógica y físico-mecánica de las serpentinitas de la comarca de Macael (Almería, S de España) para su uso como roca ornamental. Geogaceta 2013, 54, 47–50.

- World Health Organization World Health Statistics “Monitoring Health for the SDGs Sustainable Development Goal”; 2018; ISBN 978-92-4-156558-5.

- Benedetti, S.; Nuvoli, B.; Catalani, S.; Galati, R. Reactive Oxygen Species a Double-Edged Sword for Mesothelioma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 16848–16865. [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Yang, L.; Zhu, O.; Yu, J.; Jia, X.; Dong, T.; Lu, R. Multivariate Analysis of Trace Elements Distribution in Hair of Pleural Plaques Patients and Health Group in a Rural Area from China. Hair Therap Transplantat 2014, 04. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sosa, M.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.; Buitrago, G.; Triana, I.; Pino, L. Asbesto como carcinógeno ocupacional en Colombia: desde la biología molecular hasta la salud pública. Revista Colombiana de Cancerología 2022, 26, 127–136. [CrossRef]

- Schreier, H.; Northcote, T.G.; Hall, K. Trace Metals in Fish Exposed to Asbestos Rich Sediments. Water Air Soil Pollut 1987, 35, 279–291. [CrossRef]

- Velandia, M.H.P.; Peñuela, J.M.V. Análisis de la normatividad en salud entorno al uso de asbesto a nivel mundial. Universidad ECCI 2019.

- Mossman, B.T.; Marsh, J.P. Evidence Supporting a Role for Active Oxygen Species in Asbestos-Induced Toxicity and Lung Disease. Environmental Health Perspectives 1989, 81, 91–94. [CrossRef]

- Pavlisko, E.N.; Sporn, T.A. MesotheliomaIn. in: Oury, T., Sporn, T., Roggli, V. (Eds). In Pathology of Asbestos-Associated Diseases; Oury, T.D., Sporn, T.A., Roggli, V.L., Eds.; 2014; pp. 81–140.

- Peralta-Amaro, A.L.; Vázquez-Hernández, A.; Morales-Osorio, G.; Pecero-García, E.; Triana-González, S.; Manzo-Carballo, F.; Acosta-Jiménez, E. A Survivor Woman after Three Years of a Cardiac Tamponade. J Cardiol Cases 2021, 25, 259–261. [CrossRef]

- Geller, S.A.; Campos, F.P.F. Asbestos-Related Pleural Disease. ACR 2013, 3. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado De Sasia, A. Asbestosis. Estudio retrospectivo de una serie de casos de Guipúzcoa y revisión bibliográfica. 2019.

- Burgos Díez, P.; Pozuelo León, R. Prevención de riesgos laborales derivados de la exposición a amianto, Universidas de Valladoid, Campus de Palencia, 2017.

- López, V.G. Análisis mineralógico y Registros laborales de amianto, un ejemplo más de su valor. Archivos de Prevención de Riesgos Laborales 2020, 23, 357–362. [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud Laboral El Amianto Hoy Retos Tras La Prohibición; Segunda edición.; IV Plan director en Prevención de Riesgos Laborales de la Comunidad de Madrid: CCOO de Madrid, 2016;

- Bhandari, J.; Thada, P.K.; Sedhai, Y.R. Asbestosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2022.

- Huh, D.-A.; Chae, W.-R.; Choi, Y.-H.; Kang, M.-S.; Lee, Y.-J.; Moon, K.-W. Disease Latency According to Asbestos Exposure Characteristics among Malignant Mesothelioma and Asbestos-Related Lung Cancer Cases in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 15934. [CrossRef]

- García Gómez, M.; Menéndez-Navarro, A.; Castañeda López, R. Incidencia En España de La Asbestosis y Otras Enfermedades Pulmonares Benignas Debidas al Amianto Durante El Período 1962-2010. Revista Española de Salud Pública 2012, 86, 613–625.

- Barjola, J.M. Las víctimas del amianto sufren un calvario judicial: “Muchos fallecen durante el proceso y tenemos que sustituirlos por sus herederos” 2024.

- Lope, V.; Pollán, M.; Pérez-Gómez, B.; Aragonés, N.; Vidal, E.; Gómez-Barroso, D.; Ramis, R.; García-Pérez, J.; Cabanes, A.; López-Abente, G. Municipal Distribution of Ovarian Cancer Mortality in Spain. BMC Cancer 2008, 8, 258. [CrossRef]

- GBD Results Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Luis Gómez, J.; Benedicto, M.; Tisminetzky, A.; Barrera, M.; Costa, E.; Pérez, E.; Lafuente, R.; Lasmarias, A.; Arenas, M.; Valldeoriola, M. Guía Informativa A Toda La Población Sobre Los Riesgos Del Amianto; Asociación de Víctimas Afectadas por el Amianto en Cataluña, 2017;

- Marín Martínez, B.; Clavera, I. Asbestosis. Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra 2005, 28, 37–44.

- García López, V. Programas de eliminación del Amianto. Lecciones desde Polonia. Arch Prev Riesgos Labor 2021, 24, 62–73. [CrossRef]

- 2009; 43. European Directive 2009/148/EU Revision of Directive 2009/148/EC on the Protection of Workers from Risks Related to the Exposure of Asbestos at Work; 2009;

- García Gómez, M.; Artieda Pellejero, L.; Esteban Buedo, V.; Guzmán Fernández, A.; Camino Durán, F.; Martínez Castillo, A.; Lezáun Goñi, M.; Gallo Fernández, M.; González García, I.; Martínez Arguisuelas, N.; et al. La Vigilancia de La Salud de Los Trabajadores Expuestos al Amianto: Ejemplo de Colaboración Entre El Sistema de Prevención de Riesgos Laborales y El Sistema Nacional de Salud. Revista Española de Salud Pública 2006, 80, 27–39.

- Aragón Bombín, R. Guía Para La Protección de Las Víctimas Del Amianto; Secretaría de Salud Laboral y Medio ambiente UGt-CEC, 2013;

- Instituto Nacional de Seguridad y Salud en el Trabajo, O.A., M.P. Guía Técnica para la evaluación y prevención de riesgos con la explosión al amianto; Madrid.; INSST, 2022;

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. NIOSH Total Worker Health National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 2023 Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/index.html (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- The Lancet Oncology Asbestos Exposure: The Dust Cloud Lingers. 2019, 20, 1035. [CrossRef]

- Fazzo, L.; Minelli, G.; De Santis, M.; Bruno, C.; Zona, A.; Conti, S.; Comba, P. Epidemiological Surveillance of Mesothelioma Mortality in Italy. Cancer Epidemiology 2018, 55, 184–191. [CrossRef]

- Merlo, D.F.; Bruzzone, M.; Bruzzi, P.; Garrone, E.; Puntoni, R.; Maiorana, L.; Ceppi, M. Mortality among Workers Exposed to Asbestos at the Shipyard of Genoa, Italy: A 55 Years Follow-Up. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source 2018, 17, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Marsili, D.; Magnani, C.; Canepa, A.; Bruno, C.; Luberto, F.; Caputo, A.; Fazzo, L.; Zona, A.; Comba, P. Communication and Health Education in Communities Experiencing Asbestos Risk and Health Impacts in Italy. Annali dell’Istituto Superiore di Sanita 2019, 55, 70–79. [CrossRef]

- Magnani, C.; Terracini, B.; Ivaldi, C.; Botta, M.; Mancini, A.; Andrion, A. Pleural Malignant Mesothelioma and Non-Occupational Exposure to Asbestos in Casale Monferrato, Italy. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 1995, 52, 362–367. [CrossRef]

- Musti, M.; Pollice, A.; Cavone, D.; Dragonieri, S.; Bilancia, M. The Relationship between Malignant Mesothelioma and an Asbestos Cement Plant Environmental Risk: A Spatial Case-Control Study in the City of Bari (Italy). International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 2009, 82, 489–497. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.M.; Tworoger, S.S.; Harris, H.R.; Anderson, G.L.; Weinberg, C.R.; Trabert, B.; Kaunitz, A.M.; D’Aloisio, A.A.; Sandler, D.P.; Wentzensen, N. Association of Powder Use in the Genital Area With Risk of Ovarian Cancer. JAMA 2020, 323, 49–59. [CrossRef]

- Rapal–Uruguay ¿Cuál Es El Problema Con El Talco y Cómo Se Relaciona Con El Asbesto?; Ipen, 2020; pp. 4–5;.

| Activities | Economic sectors |

|---|---|

| Brickwork | Shipyards and ship breaking yards |

| Firefighters | Boilermaking |

| Loading and unloading of asbestos | Carpentry |

| Installation of insulation | Construction |

| Excavation of oil wells | Oil and gas extraction and refining |

| Asbestos extraction, preparation and trasport | Asbestos miners and millers |

| Manufacture of asbestos paper | Manufacture of paints and plastics |

| Manufacturing of fibre cement boards | Wanufacturing of posts and uprights |

| Manufacturing and repair of brake shoes | Manufacturing of asbestos shingles and cardboard |

| Railway workers | Asbestos fragmentation |

| Fireproofing | Asbestos insulation industries |

| Asbestos-free cardboard and paper industries | Fiber cement product industries |

| Asbestos textile industries | Transport and treatment of waste |

| Chemical rubber industry | Acoustic product installers |

| Installation of pipes and ovens | Manufacturing of asbestos products |

| Turbine manufacturing | Car mechanics |

| Asphalt mixers | Iron gangue miners |

| Talc miners | Construction demolition operations |

| Peons | Plastic chemicals (aeronautical) |

| Machinery manufactures | Chemicals |

| Asbestos coating of boilers | Clutch and brake repair |

| Fiber cement canyon lining | Air filtration systems |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).