Submitted:

05 August 2024

Posted:

06 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Review

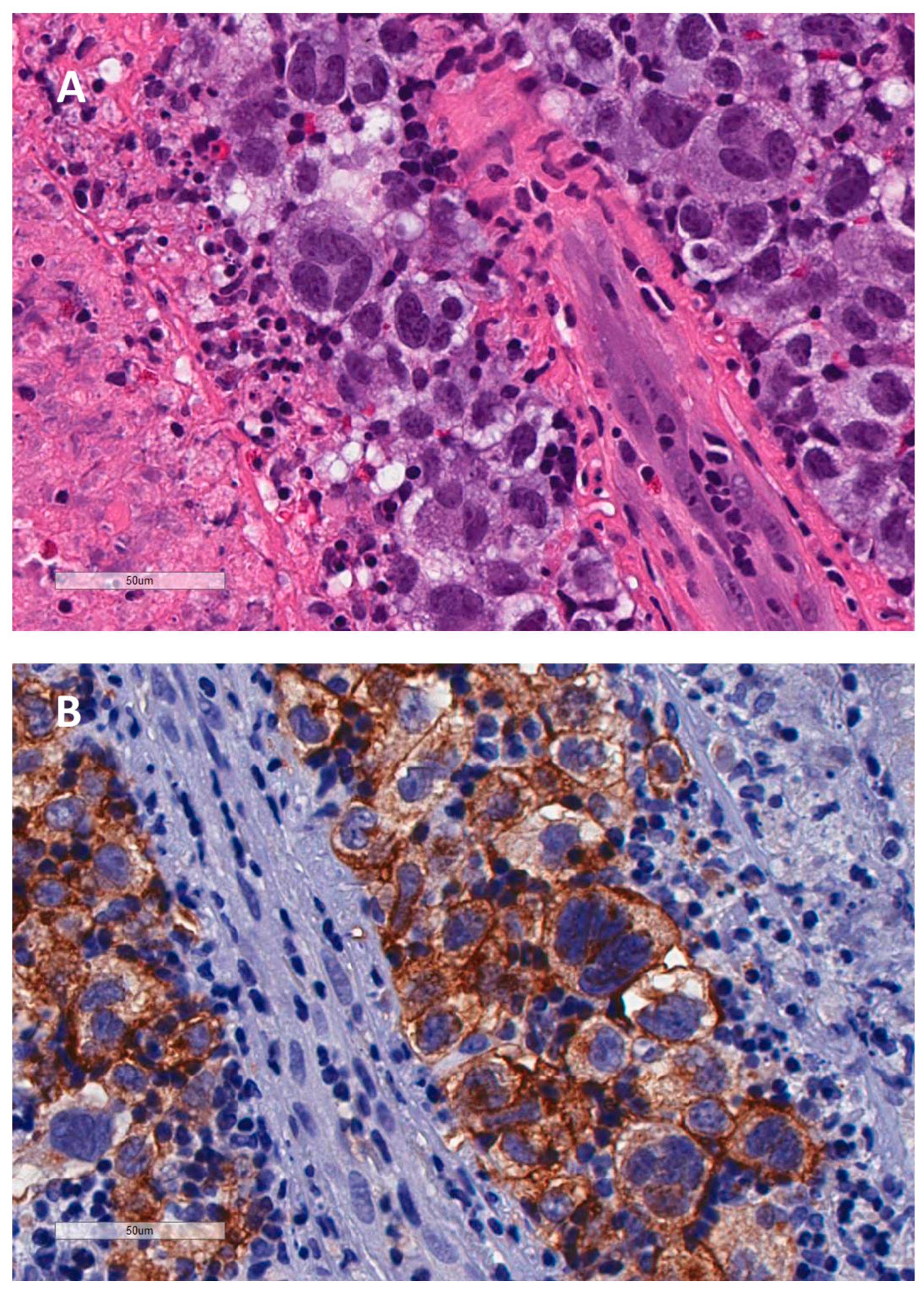

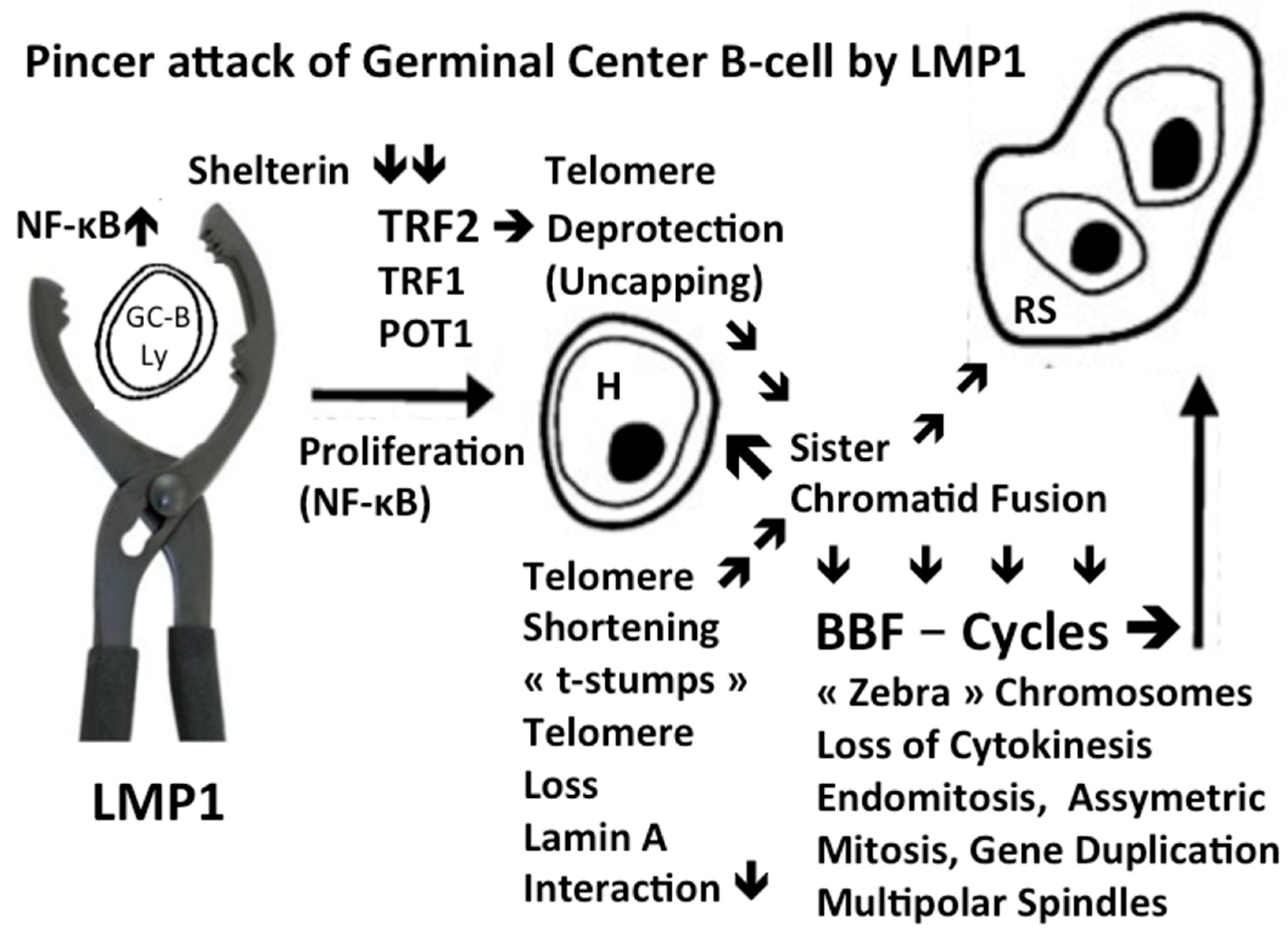

2.1. LMP1: the Golden Key to H and RS in 2D Restricted Research

2.2. 3D Telomere-Shelterin Complex: The Railway Turntable in H and RS Morphogenesis

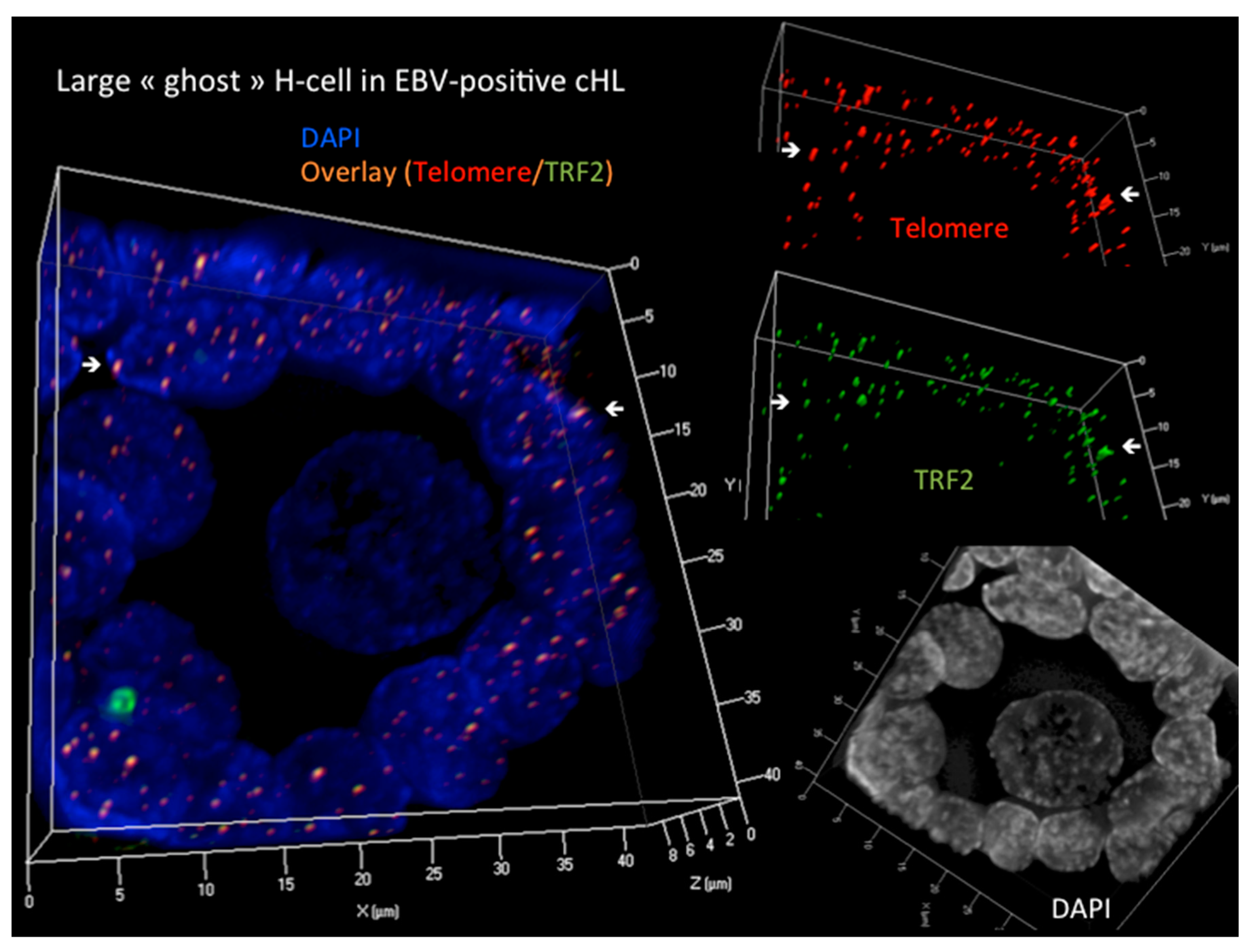

2.3. 3D nuclear Remodeling during the Transition from H to RS

2.4. LMP1 Induces TRF2 de-Regulation as Essential Step for H Formation and Progression to RS

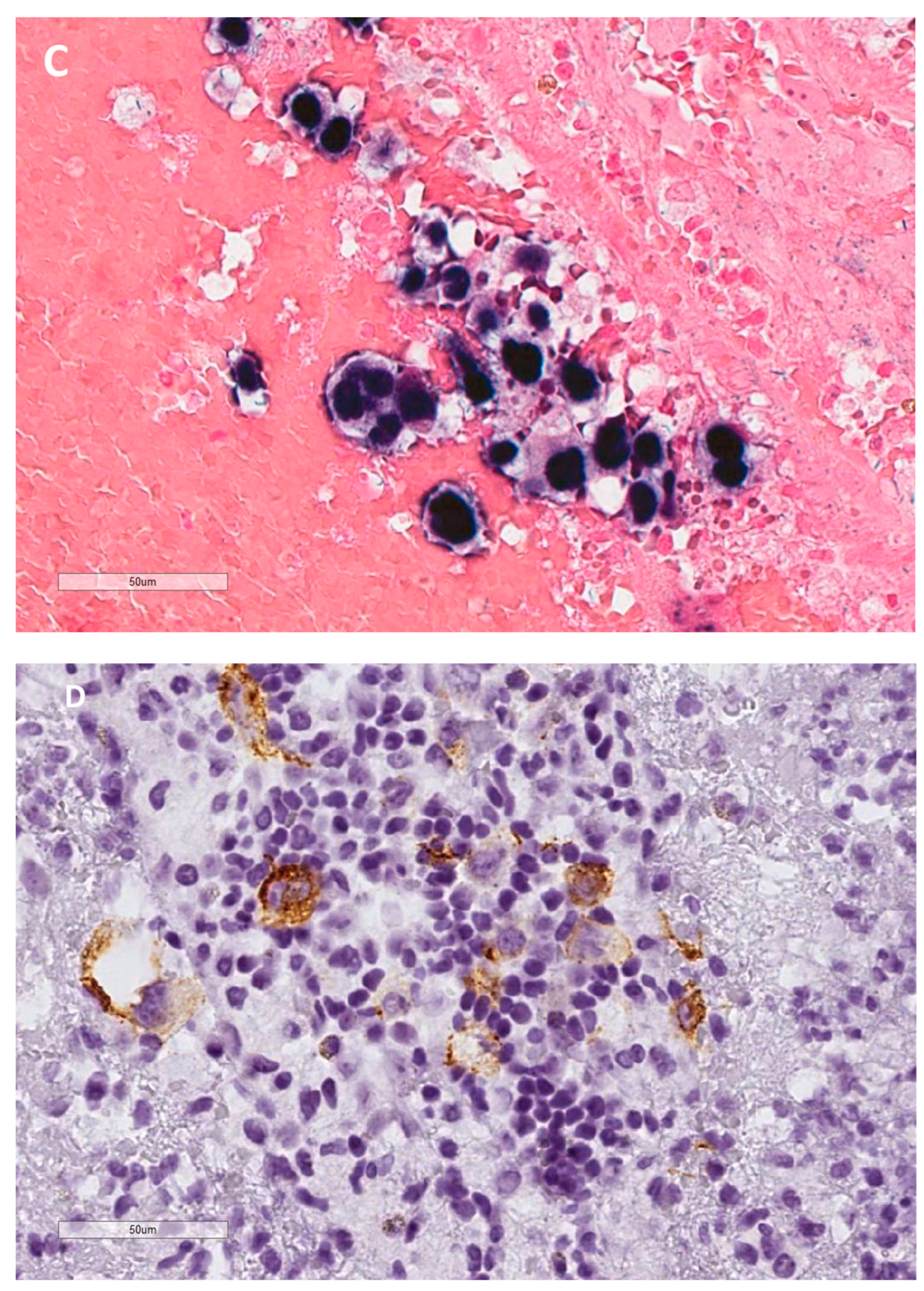

2.5. 3D Disruption of Direct 3D Telomere-TRF2 Interaction Is a Hallmark of H and RS

2.6. Lamin Basics and Lamin A/C Overexpression in H and RS

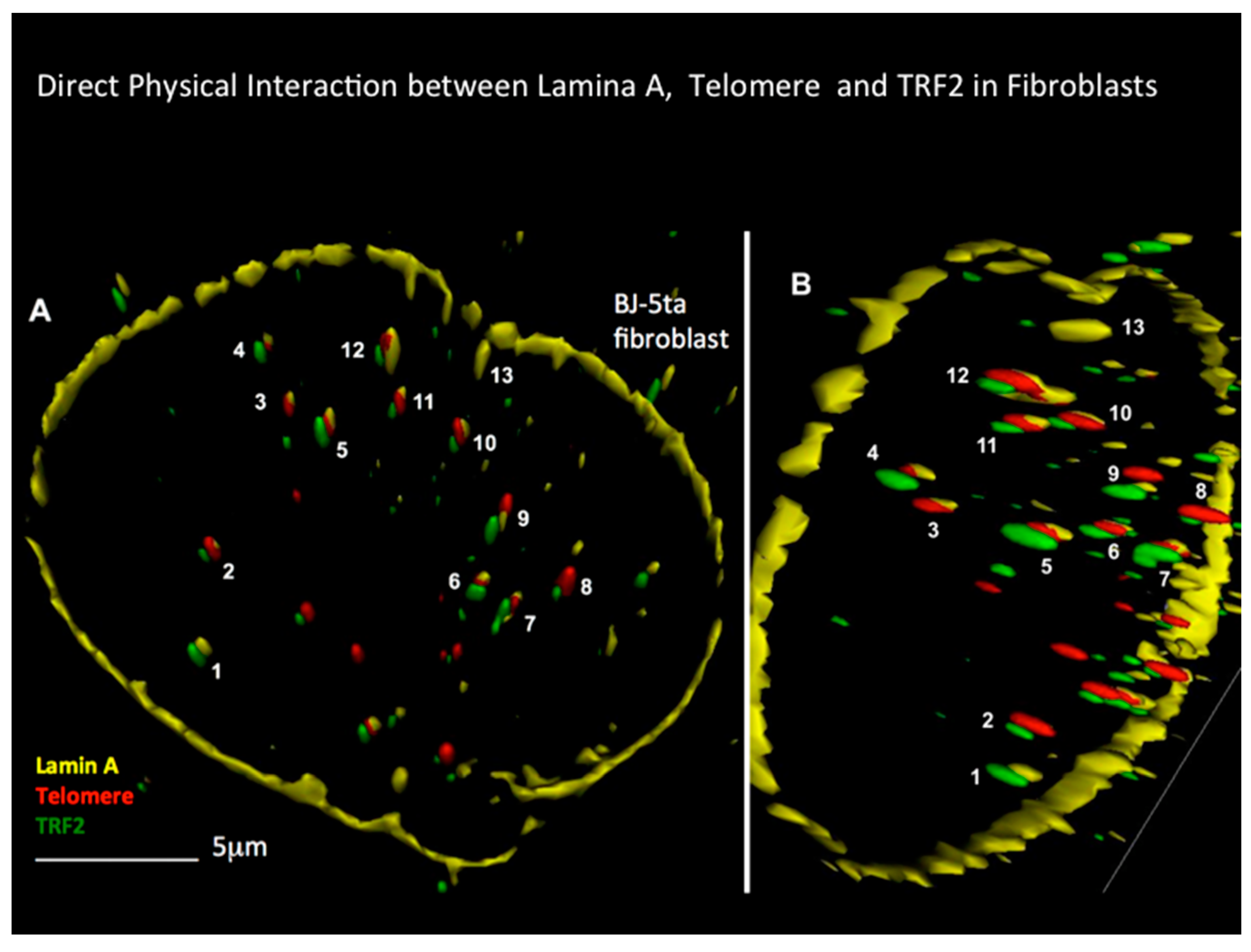

2.7. Progressive Disruption of the 3D Lamin A/C-TRF2-DNA Interaction from H to RS

2.8. Prognostic and Future Potential Therapeutic Implications of the 3D Nanotechnology Findings

3. Conclusions

References

- Hodgkin, T. On some Morbid Appearances of the Absorbent Glands and Spleen. Med. Chir. Trans. 1832, 17, 68–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, C. Über eine eigenartige unter dem Bilde der Pseudoleukämie verlaufende Tuberculosdes lymphatischen Apparates. Ztschr. Heilk. 1898, 119, 21–90. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, D.M. On the pathological changes in Hodgkin's disease, with especial reference to its relation to tuberculosis. Johns Hopkins Hosp. Rep. 1902, 10, 133–196. [Google Scholar]

- Küppers, R.; Rajewsky, K.; Zhao, M.; Simons, G.; Laumann, R.; Fischer, R.; Hansmann, M.L. Hodgkin disease: Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells picked from histological sections show clonal immunoglobulin gene rearrangements and appear to be derived from B cells at various stages of development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 10962–10966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küppers, R. Molecular biology of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In Advances in Cancer Research; Academic Press: Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2002; Volume 84, pp. 277–312. [Google Scholar]

- Mancao, C.; Altmann, M.; Jungnickel, B.; Hammerschmidt, W. Rescue of “crippled” germinal center B cells from apoptosis by Epstein-Barr virus. Blood 2005, 106, 4339–4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorley-Lawson, D.A. EBV Persistence—Introducing the Virus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 390, 151–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.J.; Gocke, C.D.; Kasamon, Y.L.; Miller, C.B.; Perkins, B.; Barber, J.P.; Vala, M.S.; Gerber, J.M.; Gellert, L.L.; Siedner, M.; Lemas, M.V.; Brennan, S.; Ambinder, R.F.; Matsui, W. Circulating clonotypic B cells in classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2009, 113, 5920–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pallesen, G.; Hamilton-Dutoit, S.J.; Rowe, M.; Young, L.S. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus latent gene products in tumour cells of Hodgkin's disease. Lancet 1991, 337, 320–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knecht, H.; Bachmann, E.; Brousset, P.; Sandvej, K.; Nadal, D.; Bachmann, F.; Odermatt, B.F.; Delsol, G.; Pallesen, G. Deletions within the LMP1 oncogene of Epstein-Barr virus are clustered in Hodgkin's disease and identical to those observed in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Blood 1993, 82, 2937–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swerdlow, S.H.; Campo, E.; Pileri, S.A.; Harris, N.L.; Stein, H.; Siebert, R.; Advani, R.; Ghielmini, M.; Salles, G.A.; Zelenetz, A.D.; et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2016, 127, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarweh, S.; Udden, M.M.; Shahab, I.; Kroll, M.; Sears, D.A.; Lynch, G.R.; Teh, B.S.; Lu, H.H. HIV-related Hodgkin's disease with central nervous system involvement and association with Epstein-Barr virus. Am J Hematol. 2003, 72, 216–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, V.; Hummel, M.; Marafioti, T.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Assaf, C.; Stein, H. Detection of clonal T-cell receptor gamma-chain gene rearrangements in Reed-Sternberg cells of classic Hodgkin disease. Blood 2000, 95, 3020–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzankov, A.; Bourgau, C.; Kaiser, A.; Zimpfer, A.; Maurer, R.; Pileri, S.A.; Went, P.; Dirnhofer, S. (2005) Rare expression of T-cell markers in classical Hodgkin's lymphoma. Mod. Pathol. 2005, 18, 1542–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drexler, H.G.; Pommerenke, C.; Eberth, S.; Nagel, S. Hodgkin lymphoma cell lines: to separate the wheat from the chaff. Biol. Chem. 2018, 399, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knecht, H.; McQuain, C.; Martin, J.; Rothenberger, S.; Drexler, H.G.; Berger, C.; Bachmann, E.; Kittler, E.L.; Odermatt, B.F.; Quesenberry, P.J. Expression of the LMP1 oncoprotein in the EBV negative Hodgkin's disease cell line L-428 is associated with Reed-Sternberg cell morphology. Oncogene 1996, 13, 947–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weber-Matthiesen, K.; Deerberg, J.; Poetsch, M.; Grote, W.; Schlegelberger, B. Numerical chromosome aberrations are present within the CD30+ Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells in 100% of analyzed cases of Hodgkin's disease. Blood 1995, 86, 1464–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deerberg-Wittram, J.; Weber-Matthiesen, K.; Schlegelberger, B. Cytogenetics and molecular cytogenetics in Hodgkin's disease. Ann. Oncol. 1996, 7 Suppl 4, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janz, M.; Mathas, S. The pathogenesis of classical Hodgkin's lymphoma: what can we learn from analyses of genomic alterations in Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells? Haematologica 2008, 93, 1292–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Subero JI, Klapper W, Sotnikova A, Callet-Bauchu E, Harder L, Bastard C, Schmitz R, Grohmann S, Höppner J, Riemke J, Barth TF, Berger F, Bernd HW, Claviez A, Gesk S, Frank GA, Kaplanskaya IB, Möller P, Parwaresch RM, Rüdiger T, Stein H, Küppers R, Hansmann ML, Siebert R; Deutsche Krebshilfe Network Project Molecular Mechanisms in Malignant Lymphomas. Chromosomal breakpoints affecting immunoglobulin loci are recurrent in Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells of classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 10332–8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roemer, M.G.; Advani, R.H.; Ligon, A.H.; Natkunam, Y.; Redd, R.A.; Homer, H.; Connelly, C.F.; Sun, H.H.; Daadi, S.E.; Freeman, G.J.; Armand, P.; Chapuy, B.; de Jong, D.; Hoppe, R.T.; Neuberg, D.S.; Rodig, S.J.; Shipp, M.A. PD-L1 and PD-L2 Genetic Alterations Define Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma and Predict Outcome. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2690–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cuceu, C.; Hempel, W.M.; Sabatier, L.; Bosq, J.; Carde, P.; M'Kacher, R. Chromosomal Instability in Hodgkin Lymphoma: An In-Depth Review and Perspectives. Cancers (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piris MA, Medeiros LJ, Chang KC Hodgkin lymphoma: a review of pathological features and recent advances in pathogenesis. Pathology 2020, 52, 154–165. [CrossRef]

- Bienz, M.; Ramdani, S.; Knecht, H. Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Past, Present, Future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weniger, M.A.; Küppers, R. Molecular biology of Hodgkin lymphoma. Leukemia 2021, 35, 968–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oliveira, L.O.D.; Costa, I.B.; Quaresma, J.A.S. Association between Epstein-Barr virus LMP-1 and Hodgkin lymphoma LMP-1 mechanisms in Hodgkin lymphoma development. Rev. Med. Virol. 2024, 34, e2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knecht, H.; Berger, C.; Rothenberger, S.; Odermatt, B.F.; Brousset, P. The role of Epstein-Barr virus in neoplastic transformation. Oncology 2001, 60, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermolen, B.J.; Garini, Y.; Mai, S.; Mougey, V.; Fest, T.; Chuang, T.C.; Chuang, A.Y.; Wark, L.; Young, I.T. Characterizing the three-dimensional organization of telomeres. Cytometry A. 2005, 67, 144–50, Erratum in: Cytometry A. 2007 May;71(5):345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, S.F.; Vermolen, B.J.; Garini, Y.; Young, I.T.; Guffei, A.; Lichtensztejn, Z.; Kuttler, F.; Chuang, T.C.; Moshir, S.; Mougey, V.; et al. c-Myc induces chromosomal rearrangements through telomere and chromosome remodeling in the interphase nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9613–9618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai S, Knecht H, Gadji M, Olujohungbe A Hematological disorder diagnosis by 3D q-FISH 2018, US Patent 9,963,745.

- Sawan, B.; Petrogiannis-Haliotis, T.; Knecht, H. Molecular Pathogenesis of Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: Advances Through the Key Player LMP1 and 3D Nanotechnology. In: Interdisciplinary Cancer Research. Springer, Cham, 2022. [CrossRef]

- de Lange, T. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 2100–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lange, T. Shelterin-Mediated Telomere Protection. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018, 52, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.J.; Cech, T.R. Shaping human telomeres: from shelterin and CST complexes to telomeric chromatin organization. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2021, 22, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brankiewicz-Kopcinska, W.; Kallingal, A.; Krzemieniecki, R.; Baginski, M. Targeting shelterin proteins for cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today 2024, 29, 104056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennewald, S.; van Santen, V.; Kieff, E. Nucleotide sequence of an mRNA transcribed in latent growth-transforming virus infection indicates that it may encode a membrane protein. J. Virol. 1984, 51, 411–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, D.; Liebowitz, D.; Kieff, E. An EBV membrane protein expressed in immortalized lymphocytes transforms established rodent cells. Cell 1985, 43(3 Pt 2), 831–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vockerodt, M.; Morgan, S.L.; Kuo, M.; Wei, W.; Chukwuma, M.B.; Arrand, J.R.; Kube, D.; Gordon, J.; Young, L.S.; Woodman, C.B.; Murray, P.G. The Epstein-Barr virus oncoprotein, latent membrane protein-1, reprograms germinal centre B cells towards a Hodgkin's Reed-Sternberg-like phenotype. J Pathol. 2008, 216, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedobitek, G.; Agathanggelou, A.; Herbst, H.; Whitehead, L.; Wright, D.H.; Young, L.S. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection in infectious mononucleosis: virus latency, replication and phenotype of EBV-infected cells. J. Pathol. 1997, 182, 151–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knecht, H.; Brousset, P.; Bachmann, E.; Sandvej, K.; Odermatt, B.F. (1994) Latent membrane protein 1: a key oncogene in EBV-related carcinogenesis? Acta Haematol. 1993, 90, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Romero-Masters, J.C.; Huebner, S.; Ohashi, M.; Hayes, M.; Bristol, J.A.; Nelson, S.E.; Eichelberg, M.R.; Van Sciver, N.; Ranheim, E.A.; Scott, R.S.; Johannsen, E.C.; Kenney, S.C. EBNA2-deleted Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) isolate, P3HR1, causes Hodgkin-like lymphomas and diffuse large B cell lymphomas with type II and Wp-restricted latency types in humanized mice. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lacoste, S.; Wiechec, E.; Dos Santos Silva, A.G.; Guffei, A.; Williams, G.; Lowbeer, M.; Benedek, K.; Henriksson, M.; Klein, G.; Mai, S. Chromosomal rearrangements after ex vivo Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection of human B cells. Oncogene 2010, 29, LCL503–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knecht, H.; Berger, C.; McQuain, C.; Rothenberger, S.; Bachmann, E.; Martin, J.; Esslinger, C.; Drexler, H.G.; Cai, Y.C.; Quesenberry, P.J.; Odermatt, B.F. Latent membrane protein 1 associated signaling pathways are important in tumor cells of Epstein-Barr virus negative Hodgkin's disease. Oncogene 1999, 18, 7161–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadji, M.; Vallente, R.; Klewes, L.; Righolt, C.; Wark, L.; Kongruttanachok, N.; Knecht, H.; Mai, S. Nuclear remodeling as a mechanism for genomic instability in cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2011, 112, 77–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knecht, H.; Mai, S. The Use of 3D Telomere FISH for the Characterization of the Nuclear Architecture in EBV-Positive Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1532, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balta-Yildrim, Z. Untersuchungen zu Telomerlängen bei Hodgkin- und Reed-Sternberg-Zellen. Doctoral Thesis, RWTH Aachen. Nov. 15, 2006.

- Chuang, T.C.; Moshir, S.; Garini, Y.; Chuang, A.Y.; Young, I.T.; Vermolen, B.; van den Doel, R.; Mougey, V.; Perrin, M.; Braun, M.; Kerr, P.D.; Fest, T.; Boukamp, P.; Mai, S. The three-dimensional organization of telomeres in the nucleus of mammalian cells. BMC Biol 2004, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knecht, H.; Sawan, B.; Lichtensztejn, D.; Lemieux, B.; Wellinger, R.J.; Mai, S. The 3D nuclear organization of telomeres marks the transition from Hodgkin to Reed-Sternberg cells. Leukemia 2009, 23, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihan, G.A.; Purohit, A.; Wallace, J.; Knecht, H.; Woda, B.; Quesenberry, P.; Doxsey, S.J. Centrosome defects and genetic instability in malignant tumors. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 3974–85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Blackburn, E.H. Human cancer cells harbor T-stumps, a distinct class of extremely short telomeres. Mol. Cell 2007, 28, 315–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Knecht, H.; Brüderlein, S.; Wegener, S.; Lichtensztejn, D.; Lichtensztejn, Z.; Lemieux, B.; Möller, P.; Mai, S. 3D nuclear organization of telomeres in the Hodgkin cell lines U-HO1 and U-HO1-PTPN1: PTPN1 expression prevents the formation of very short telomeres including "t-stumps". BMC Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheeren, F.A.; Diehl, S.A.; Smit, L.A.; Beaumont, T.; Naspetti, M.; Bende, R.J.; Blom, B.; Karube, K.; Ohshima, K.; van Noesel, C.J.; Spits, H. IL-21 is expressed in Hodgkin lymphoma and activates STAT5: evidence that activated STAT5 is required for Hodgkin lymphomagenesis. Blood 2008, 111, 4706–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Knecht, H.; Sawan, B.; Lichtensztejn, Z.; Lichtensztejn, D.; Mai, S. 3D Telomere FISH defines LMP1-expressing Reed-Sternberg cells as end-stage cells with telomere-poor ‘ghost’ nuclei and very short telomeres. Lab. Investig. 2010, 90, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremer, T.; Cremer, M.; Dietzel, S.; Müller, S.; Solovei, I.; Fakan, S. Chromosome territories--a functional nuclear landscape. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2006, 18, 307–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanctôt, C.; Cheutin, T.; Cremer, M.; Cavalli, G.; Cremer, T. Dynamic genome architecture in the nuclear space: regulation of gene expression in three dimensions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 104–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremer, T.; Cremer, M.; Hübner, B.; Silahtaroglu, A.; Hendzel, M.; Lanctôt, C.; Strickfaden, H.; Cremer, C. The Interchromatin Compartment Participates in the Structural and Functional Organization of the Cell Nucleus. Bioessays 2020, 42, e1900132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solovei, I.; Kreysing, M.; Lanctôt, C.; Kösem, S.; Peichl, L.; Cremer, T.; Guck, J.; Joffe, B. Nuclear architecture of rod photoreceptor cells adapts to vision in mammalian evolution. Cell 2009, 137, 356–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guffei, A.; Sarkar, R.; Klewes, L.; Righolt, C.; Knecht, H.; Mai, S. Dynamic chromosomal rearrangements in Hodgkin’s lymphoma are due to ongoing three-dimensional nuclear remodeling and breakage-bridge-fusion cycles. Haematologica 2010, 95, 2038–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guffei, A.; Lichtensztejn, Z.; Gonçalves Dos Santos Silva, A.; Louis, S.F.; Caporali, A.; Mai, S. c-Myc-dependent formation of Robertsonian translocation chromosomes in mouse cells. Neoplasia 2007, 9, 578–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Righolt, C.H.; Guffei, A.; Knecht, H.; Young, I.T.; Stallinga, S.; van Vliet, L.J.; Mai, S. Differences in nuclear DNA organization between lymphocytes, Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells revealed by structured illumination microscopy. J. Cell. Biochem. 2014, 115, 1441–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bilaud, T.; Brun, C.; Ancelin, K.; Koering, C.E.; Laroche, T.; Gilson, E. Telomeric localization of TRF2, a novel human telobox protein. Nat. Genet. 1997, 17, 236–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broccoli, D.; Smogorzewska, A.; Chong, L.; de Lange, T. Human telomeres contain two distinct Myb-related proteins, TRF1 and TRF2. Nat. Genet. 1997, 17, 231–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feuerhahn, S.; Chen, L.Y.; Luke, B.; Porro, A. No DDRama at chromosome ends: TRF2 takes centre stage. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 275–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, R.; Biju, K.; Sun, W.; Sodeinde, T.; Al-Hiyasat, A.; Morgan, J.; Ye, X.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Chang, S. Homology directed telomere clustering, ultrabright telomere formation and nuclear envelope rupture in cells lacking TRF2B and RAP1. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2144, Erratum in: Nat. Commun. 2023, Jun 7;14(1), 3319. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39144-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rai, R.; Sodeinde, T.; Boston, A.; Chang, S. Telomeres cooperate with the nuclear envelope to maintain genome stability. Bioessays 2024, 46, e2300184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floettmann, J.E.; Ward, K.; Rickinson, A.B.; Rowe, M. Cytostatic effect of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 analyzed using tetracycline-regulated expression in B cell lines. Virology 1996, 223, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajoie, V.; Lemieux, B.; Sawan, B.; Lichtensztejn, D.; Lichtensztejn, Z.; Wellinger, R.; Mai, S.; Knecht, H. LMP1 mediates multinuclearity through downregulation of shelterin proteins and formation of telomeric aggregates. Blood 2015, 125, 2101–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Celli, G.B.; de Lange, T. DNA processing is not required for ATM-mediated telomere damage response after TRF2 deletion. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005, 7, 712–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knecht, H.; Johnson, N.A.; Haliotis, T.; Lichtensztejn, D.; Mai, S. Disruption of direct 3D telomere-TRF2 interaction through two molecularly disparate mechanisms is a hallmark of primary Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells. Lab. Investig. 2017, 97, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nera, B.; Huang, H.S.; Lai, T.; Xu, L. Elevated levels of TRF2 induce telomeric ultrafine anaphase bridges and rapid telomere deletions. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nera, B.; Huang, H.S.; Hendrickson, E.A.; Xu, L. Both the classical and alternative non-homologous end joining pathways contribute to the fusion of drastically shortened telomeres induced by TRF2 overexpression. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bargou, R.C.; Emmerich, F.; Krappmann, D.; Bommert, K.; Mapara, M.Y.; Arnold, W.; Royer, H.D.; Grinstein, E.; Greiner, A.; Scheidereit, C.; et al. Constitutive nuclear factor-kappaB-RelA activation is required for proliferation and survival of Hodgkin’s disease tumor cells. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothenberger, S.; Bachmann, E.; Berger, C.; McQuain, C.; Odermatt, B.F.; Knecht, H. Natural 30 bp and 69 bp deletion variants of the LMP1 oncogene do stimulate NF-κB mediated transcription. Oncogene 1997, 14, 2123–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knecht, H.; Mai, S. LMP1 and Dynamic Progressive Telomere Dysfunction: A Major Culprit in EBV-Associated Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Viruses 2017, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- MacLeod, R.A.; Spitzer, D.; Bar-Am, I.; Sylvester, J.E.; Kaufmann, M.; Wernich, A.; Drexler, H.G. Karyotypic dissection of Hodgkin’s disease cell lines reveals ectopic subtelomeres and ribosomal DNA at sites of multiple jumping translocations and genomic amplification. Leukemia 2000, 14, 1803–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, R.D.; Yoon, M.; Khuon, S.; Goldman, R.D. Nuclear Lamins A and B1: Different Pathways of Assembly during Nuclear Envelope Formation in Living Cells. J. Cell. Biol. 2000, 151, 1155–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naetar, N.; Ferraioli, S.; Foisner, R. Lamins in the nuclear interior - life outside the lamina. J. Cell. Sci. 2017, 130, 2087–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubik, N.; Mai, S. Lamin A/C: Function in Normal and Tumor Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lin, F.; Worman, H.J. Structural organization of the human gene (LMNB1) encoding nuclear lamin B1. Genomics 1995, 27, 230–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höger, T.H.; Zatloukal, K.; Waizenegger, I.; Krohne, G. (1990) Characterization of a second highly conserved B-type lamin present in cells previously thought to contain only a single B-type lamin. Chromosoma 1990, 99(6), 99(6),379–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, D.Z.; Chaudhary, N.; Blobel, G. cDNA sequencing of nuclear lamins A and C reveals primary and secondary structural homology to intermediate filament proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1086, 83, 6450–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimi, T.; Kittisopikul, M.; Tran, J.; Goldman, A.E.; Adam, S.A.; Zheng, Y.; Jaqaman, K.; Goldman, R.D. Structural organization of nuclear lamins A, C, B1, and B2 revealed by superresolution microscopy. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2015, 26, 4075–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgay, Y.; Eibauer, M.; Goldman, A.E.; Shimi, T.; Khayat, M.; Ben-Harush, K.; Dubrovsky-Gaupp, A.; Sapra, K.T.; Goldman, R.D.; Medalia, O. The molecular architecture of lamins in somatic cells. Nature 2017, 543, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, A.A.; Zou, J.; Houston, D.R.; Spanos, C.; Solovyova, A.S.; Cardenal-Peralta, C.; Rappsilber, J.; Schirmer, E.C. Lamin A molecular compression and sliding as mechanisms behind nucleoskeleton elasticity. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leeuw, R.; Gruenbaum, Y.; Medalia, O. Nuclear Lamins: Thin Filaments with Major Functions. Trends Cell 2018, 28, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nmezi B, Xu J, Fu R et al. Concentric organization of A- and B-type lamins predicts their distinct roles in the spatial organization and stability of the nuclear lamina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4307–4315. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang SH, Jung HJ, Coffinier C, et al. Are B-type lamins essential in all mammalian cells? Nucleus 2019, 2, 562–9. [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, C.J.; Worman, H.J. (2004) A-type lamins: Guardians of the soma? Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 6, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, R.; Xu, N.; Wang, G.; et al. The lamin-A/C-LAP2α-BAF1 protein complex regulates mitotic spindle assembly positioning. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 2830–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimi, T.; Butin-Israeli, V.; Adam, S.A.; et al. Nuclear lamins in cell regulation and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2010, 75, 75,525–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sandre-Giovannoli A, Bernard R Cau P et al. Lamin a truncation in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria. Science 2003, 300, 2055. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, M.P.; Machiels, B.M.; Hopman, A.H.; Broers, J.L.; Bot, F.J.; Arends, J.W.; Ramaekers, F.C.; Schouten, H.C. Comparison of A and B-type lamin expression in reactive lymph nodes and nodular sclerosing Hodgkin’s disease. Histopathology 1997, 31, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Perugini, V.; Gonzalez-Granado, J.M. Nuclear envelope lamin-A as a coordinator of T cell activation. Nucleus 2014, 5, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contu, F.; Rangel-Pozzo, A.; Trokajlo, P.; Wark, L.; Klewes, L.; Johnson, N.A.; Petrogiannis-Haliotis, T.; Gartner, J.G.; Garini, Y.; Vanni, R.; et al. Distinct 3D Structural Patterns of Lamin A/C Expression in Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg Cells. Cancers 2018, 10, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, W.H.; Houben, F.; Hoebe, R.A.; Hoebe, R.A.; Hennekam, R.; van Engelen, B.; Manders, E.M.; Ramaekers, F.C.; Broers, J.L.; Van Oostveldt, P. Increased plasticity of the nuclear envelope and hypermobility of telomeres due to the loss of A–type lamins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1800, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales-Suarez I, Redwood AB, Perkins SM et al. Novel roles for A-type lamins in telomere biology and the DNA damage response pathway. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 2414–2427. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doksani Y, Wu JY, de Lange T, Zhuang X (2013) Superresolution fluorescence imaging of telomeres reveals TRF2-dependent T-loop formation. Cell 2013, 155, 345–356. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonet T, Zaragosi LE, Philippe C et al. The human TTAGGG repeat factors 1 and 2 bind to a subset of interstitial telomeric sequences and satellite repeats. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 1028–1038. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travina, A.O.; Ilicheva, N.V.; Mittenberg, A.G.; Shabelnikov, S.V.; Kotova, A.V.; Podgornaya, O.I. The Long Linker Region of Telomere-Binding Protein TRF2 Is Responsible for Interactions with Lamins. Int. J. Mol.Sci. 2021, 22, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wood, A.M.; Rendtlew Danielsen, J.M.; Lucas, C.A.; Rice, E.L.; Scalzo, D.; Shimi, T.; Goldman, R.D.; Smith, E.D.; Le Beau, M.M.; Kosak, S.T. (2014) TRF2 and lamin A/C interact to facilitate the functional organization of chromosome ends. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronshtein I, Kepten E, Kanter I et al. Loss of lamin A function increases chromatin dynamics in the nuclear interior. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8044. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, A.M.; Laster, K.; Rice, E.L.; Kosak, S.T. A beginning of the end: new insights into the functional organization of telomeres. Nucleus 2015, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.D.; Garza-Gongora, A.G.; MacQuarrie, K.L.; Kosak, S.T. Interstitial telomeric loops and implications of the interaction between TRF2 and lamin A/C. Differentiation 2018, 102, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contu, F. Spatial organization of lamin A/C in Hodgkin’s lymphoma and multiple myeloma. Doctoral thesis, University of Cagliari, February 2020.

- Canellos, G.P.; Anderson, J.R.; Propert, K.J.; Nissen, N.; Cooper, M.R.; Henderson, E.S.; Green, M.R.; Gottlieb, A.; Peterson, B.A. Chemotherapy of advanced Hodgkin's disease with MOPP, ABVD, or MOPP alternating with ABVD. N Engl. J. Med. 1992, 327, 1478–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuruvilla, J. Standard therapy of advanced Hodgkin lymphoma. Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2009, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, L.I.; Hong, F.; Fisher, R.I.; Bartlett, N.L.; Connors, J.M.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Wagner, H.; Stiff, P.J.; Cheson, B.D.; Gospodarowicz, M.; Advani, R.; Kahl, B.S.; Friedberg, J.W.; Blum, K.A.; Habermann, T.M.; Tuscano, J.M.; Hoppe, R.T.; Horning, S.J. Randomized phase III trial of ABVD versus Stanford V with or without radiation therapy in locally extensive and advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma: an intergroup study coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (E2496). J Clin Oncol 2013, 31, 684–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, L.A.; Begum, T.; Halder, A.; Babu, M.C.S.; Lokesh, K.N.; Rudresha, A.H.; Rajeev, L.K.; Saldanha, S.C. Clinical Profile and Outcome of Adult Classical Hodgkin's Lymphoma: Real World Single Centre Experience. Indian J. Hematol. Blood Transfus. 2024, 40, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carde, P.; Karrasch, M.; Fortpied, C.; Brice, P.; Khaled, H.; Casasnovas, O.; Caillot, D.; Gaillard, I.; Bologna, S.; Ferme, C.; Lugtenburg, P.J.; Morschhauser, F.; Aurer, I.; Coiffier, B.; Meyer, R.; Seftel, M.; Wolf, M.; Glimelius, B.; Sureda, A.; Mounier, N. Eight Cycles of ABVD Versus Four Cycles of BEACOPPescalated Plus Four Cycles of BEACOPPbaseline in Stage III to IV, International Prognostic Score ≥ 3, High-Risk Hodgkin Lymphoma: First Results of the Phase III EORTC 20012 Intergroup Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34(17), 34(17),2028–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merli, F.; Luminari, S.; Gobbi, P.G.; Cascavilla, N.; Mammi, C.; Ilariucci, F.; Stelitano, C.; Musso, M.; Baldini, L.; Galimberti, S.; Angrilli, F.; Polimeno, G.; Scalzulli, P.R.; Ferrari, A.; Marcheselli, L.; Federico, M. Long-Term Results of the HD2000 Trial Comparing ABVD Versus BEACOPP Versus COPP-EBV-CAD in Untreated Patients With Advanced Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Study by Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1175–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knecht, H.; Kongruttanachok, N.; Sawan, B.; Brossard, J.; Prevost, S.; Turcotte, E.; Lichtensztejn, Z.; Lichtensztejn, D.; Mai, S. Three-dimensional Telomere Signatures of Hodgkin- and Reed-Sternberg Cells at Diagnosis Identify Patients with Poor Response to Conventional Chemotherapy. Transl. Oncol. 2012, 5, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanbhag, S.; Ambinder, R.F. Hodgkin lymphoma: A review and update on recent progress. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Williams, D.; Gray, C.; Picheca, L. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma in Brentuximab Vedotin-naïve Patients: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness, and Guidelines [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2019 Jun 21. PMID: 31503428. Burton C, Allen P, Herrera AF. Paradigm Shifts in Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment: From Frontline Therapies to Relapsed Disease. Am, Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2024, 44, e433502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, N.S.; Dittus, C.; Thakkar, A.; Beaven, A.W. The optimal management of relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: post-brentuximab and checkpoint inhibitor failure. Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol, Educ. Program. 2023, 2023, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Szczurek, A.; Klewes, L.; Xing, J.; Gourram, A.; Birk, U.; Knecht, H.; Dobrucki, J.W.; Mai, S.; Cremer, C. Imaging chromatin nanostructure with binding-activated localization microscopy based on DNA structure fluctuations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- M'kacher, R.; Cuceu, C.; Al Jawhari, M.; Morat, L.; Frenzel, M.; Shim, G.; Lenain, A.; Hempel, W.M.; Junker, S.; Girinsky, T.; Colicchio, B.; Dieterlen, A.; Heidingsfelder, L.; Borie, C.; Oudrhiri, N.; Bennaceur-Griscelli, A.; Moralès, O.; Renaud, S.; Van de Wyngaert, Z.; Jeandidier, E.; Delhem, N.; Carde, P. The Transition between Telomerase and ALT Mechanisms in Hodgkin Lymphoma and Its Predictive Value in Clinical Outcomes. Cancers (Basel) 2018, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lima, M.F.; Freitas, M.O.; Hamedani, M.K.; Rangel-Pozzo, A.; Zhu, X.D.; Mai, S. Consecutive Inhibition of Telomerase and Alternative Lengthening Pathway Promotes Hodgkin's Lymphoma Cell Death. Biomedicines 2022, 10(9), 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brankiewicz-Kopcinska, W.; Kallingal, A.; Krzemieniecki, R.; Baginski, M. Targeting shelterin proteins for cancer therapy. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 104056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maco, M.; Kupcova, K.; Herman, V.; Ondeckova, I.; Kozak, T.; Mocikova, H.; Havranek, O.; Czech Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group. Circulating tumor DNA in Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 2022, 101, 2393–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Braun, H.; Xu, Z.; Chang, F.; Viceconte, N.; Rane, G.; Levin, M.; Lototska, L.; Roth, F.; Hillairet, A.; Fradera-Sola, A.; Khanchandani, V.; Sin, Z.W.; Yong, W.K.; Dreesen, O.; Yang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, F.; Butter, F.; Kappei, D. ZNF524 directly interacts with telomeric DNA and supports telomere integrity. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).