1. Introduction

In recent years, significant advancements have been made in understanding the influence of nickel as an alloying element in steels[1-4]. Nickel, especially in concentrations around 4-5%, has garnered extensive research attention due to its pronounced effects on mechanical properties such as toughness, strength, and ductility. The inclusion of nickel in steel alloys is known to enhance low-temperature toughness and resistance to brittle fracture, making it an indispensable component in steels used for cryogenic applications. Nickel’s role in stabilizing austenite and inhibiting martensitic transformations at lower temperatures has been thoroughly documented[5-7]. This characteristic is particularly beneficial for maintaining uniform mechanical properties across a wide range of service conditions[

8,

9]. For example, a nickel content of approximately 6% significantly improves the impact toughness of medium-carbon steels, while maintaining an optimal balance between strength and ductility[

10].

The addition of nickel improves the hardenability of steels, allowing for the development of a finer microstructure, which in turn enhances mechanical properties. This is especially important in low-temperature environments where nickel’s ability to stabilize austenite prevents the formation of brittle phases like martensite, thus improving ductility and impact resistance[11-14]. Advances in metallurgical techniques have allowed for more precise control over nickel distribution within the steel matrix, leading to the creation of high-performance alloys tailored for specific applications. For instance, in the oil and gas sector, nickel-containing steels are prized for their resistance to corrosive environments and their ability to withstand hydrogen embrittlement, a common issue in such settings. Moreover, nickel is a critical component in the development of advanced high-strength steels (AHSS), which are increasingly employed in the automotive and aerospace industries for weight reduction and fuel efficiency improvements. The presence of nickel enables a higher concentration of carbon and other alloying elements, facilitating the formation of a stable austenitic phase at room temperature[

15,

16]. This stability is crucial for achieving a combination of high strength and good ductility, which are essential for manufacturing complex shapes without cracking.

The hot working process, which includes stages like heating, holding, and cooling, is a crucial method for enhancing the overall mechanical properties of steels[17-20]. Each stage significantly influences the material's microstructure and, consequently, its mechanical properties. The evolution of microstructure, the formation of new phases, and grain growth behavior during these stages are critical in determining the final material properties. However, due to the limitations of experimental equipment and conditions, directly observing these microstructural changes during hot processing can be challenging. This limitation often hinders a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms behind microstructural evolution and high-temperature phase transformations.

The significance of real-time in-situ observation during the hot working process cannot be overstated. In-situ techniques enable researchers to monitor and analyze microstructural transformations as they occur, providing invaluable insights into the dynamic processes that govern material behavior. Such observations are crucial for optimizing thermal processing parameters, such as temperature, heating rate, and cooling rate, which are essential for achieving desired microstructural characteristics and optimal mechanical properties. For example, precise control over thermomechanical processing conditions can lead to grain refinement, enhancing both strength and toughness through mechanisms such as grain boundary strengthening and precipitation hardening.

In this context, High Temperature Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (HTCLSM) has emerged as a powerful tool for observing microstructural changes in metallic materials during heating and holding processes[

21,

22]]. HTCLSM is particularly notable for its ability to provide real-time, high-resolution imaging of microstructural evolution under controlled thermal conditions. This technique is invaluable in the study of phase transformations, grain boundary behavior, and carbide precipitation in steels[23-25]. For instance, HTCLSM enables in-situ observations of austenite transformations and the decomposition of austenite into other phases, such as ferrite and pearlite, providing critical insights into the mechanisms controlling carbide precipitation and distribution. This information is essential for developing steels with tailored properties, as the nature and distribution of carbides significantly influence mechanical properties like hardness, toughness, and wear resistance.

HTCLSM's capability to capture dynamic microstructural changes at high temperatures offers a distinct advantage over traditional metallographic techniques, which typically involve quenching and subsequent examination at room temperature[26-28]. The non-destructive nature of HTCLSM allows for continuous monitoring of the same sample region, providing comprehensive data on microstructural evolution over time. This continuous observation is crucial for correlating microstructural features with specific thermal and mechanical treatments, thus facilitating the optimization of processing parameters.

This study focuses on a low-carbon alloy steel containing 4.5% nickel, investigating its microstructural evolution during heating and isothermal holding processes using HTCLSM. Through in-situ observations, we captured real-time changes in the microstructure, particularly noting the precipitation of a dark phase precipitates during the isothermal holding stage. This phase, identified as a potential strengthening precipitate, emerged distinctly during the thermal treatment. The primary objectives of this research are twofold: first, to characterize the nature and composition of this dark precipitate, determining its formation conditions and stability; and second, to evaluate its impact on the mechanical properties of the 4.5% Ni steel. We conducted a series of mechanical tests, correlating the presence and morphology of the precipitate with changes in strength, hardness, and toughness.

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The investigated steel is a low-carbon alloy engineered to study the impact of nickel content on microstructure and mechanical properties. The chemical composition, detailed in

Table 1, includes 4.45 wt% nickel, 0.1 wt% carbon, and minor amounts of silicon, manganese, chromium, and vanadium. These elements were selected to enhance toughness, hardness, and corrosion resistance.

Nickel is a key component, stabilizing the austenite phase and promoting a fine-grained microstructure, thereby improving both strength and ductility. Its significant presence also boosts the alloy's resistance to thermal and mechanical deformation. The low carbon content minimizes carbide formation, preserving toughness and weldability. Chromium and vanadium contribute to hardness and wear resistance, while manganese aids in deoxidation and increases hardenability. Silicon enhances strength without compromising ductility. This careful alloy design and preparation set the foundation for exploring the intricate interactions between alloying elements and processing conditions, providing insights into the development of high-performance steels for advanced engineering applications.

2.2. High Temperature Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (HTCLSM) Setup

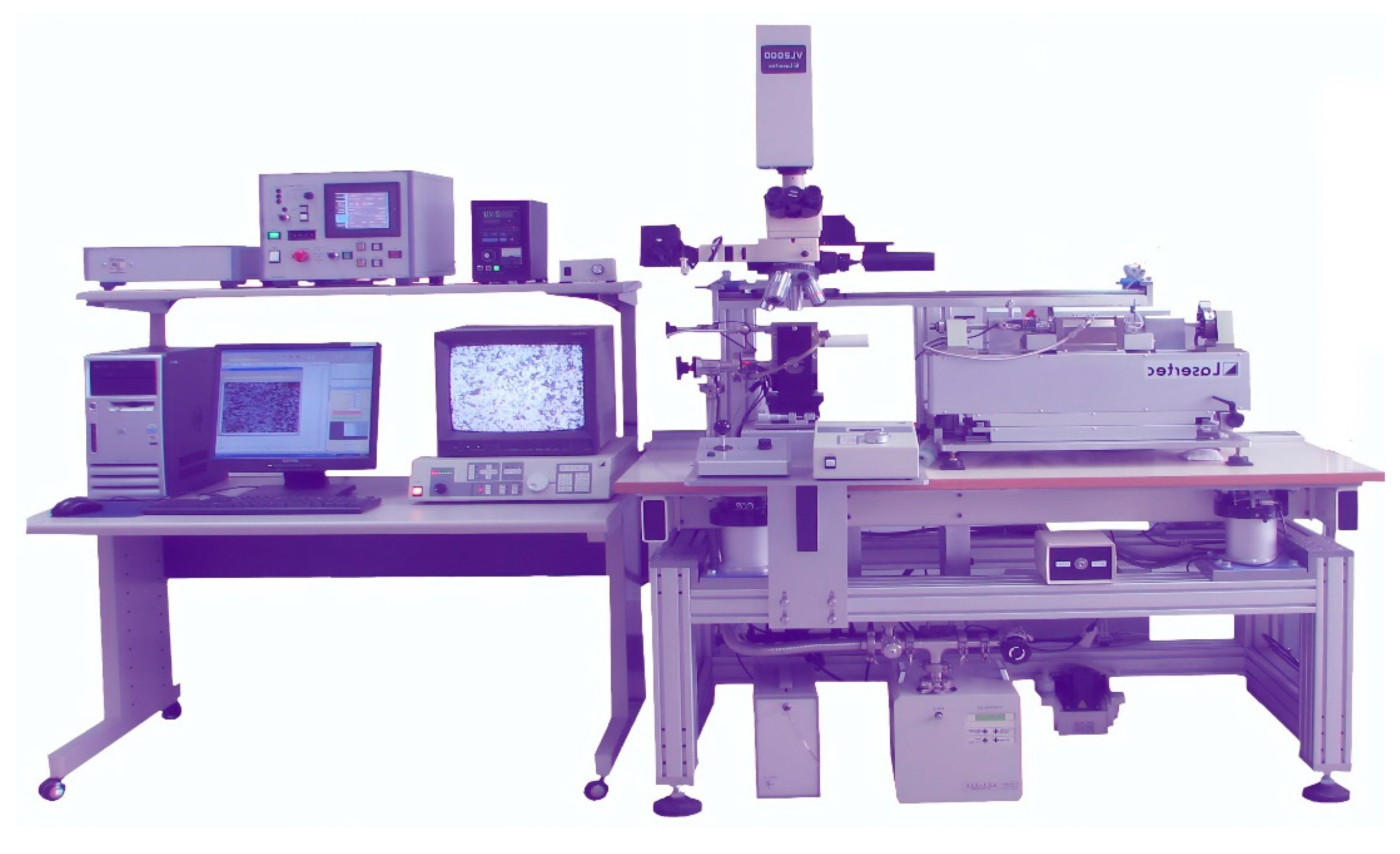

In-situ observation of the material during heating was performed using High Temperature Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (HTCLSM). The schematic diagram of the High Temperature Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (HTCLSM) is illustrated in

Figure 1. This state-of-the-art system integrates several advanced components essential for real-time microstructural observation.

The experimental setup, schematically represented in

Figure 1, features a high-temperature confocal laser scanning microscope (HTCLSM) equipped with an array of advanced components. A high-temperature furnace, capable of precise control up to 1500°C, is used to simulate various thermal processes. An integrated imaging system provides high-resolution, real-time visualization of the sample's microstructure. The temperature control system ensures accurate regulation throughout heating, holding, and cooling phases. To prevent oxidation and contamination, a protective gas system, typically utilizing argon or nitrogen, maintains an inert atmosphere around the sample. The cooling system facilitates rapid quenching, preserving microstructural features formed at high temperatures. For high-temperature mechanical testing, the setup includes a tensile furnace and control system, which allows for experiments under controlled strain rates. A sophisticated workstation and image detection system enable real-time monitoring, data acquisition, and advanced image analysis, ensuring comprehensive analysis of the observed phenomena..

2.3. Sample Preparation and Experimental Procedure

Samples for in-situ microstructural observation were prepared in cylindrical form with dimensions of φ7.5×3.5 mm. The preparation process involved meticulous grinding and polishing to achieve a smooth surface, essential for accurate imaging.

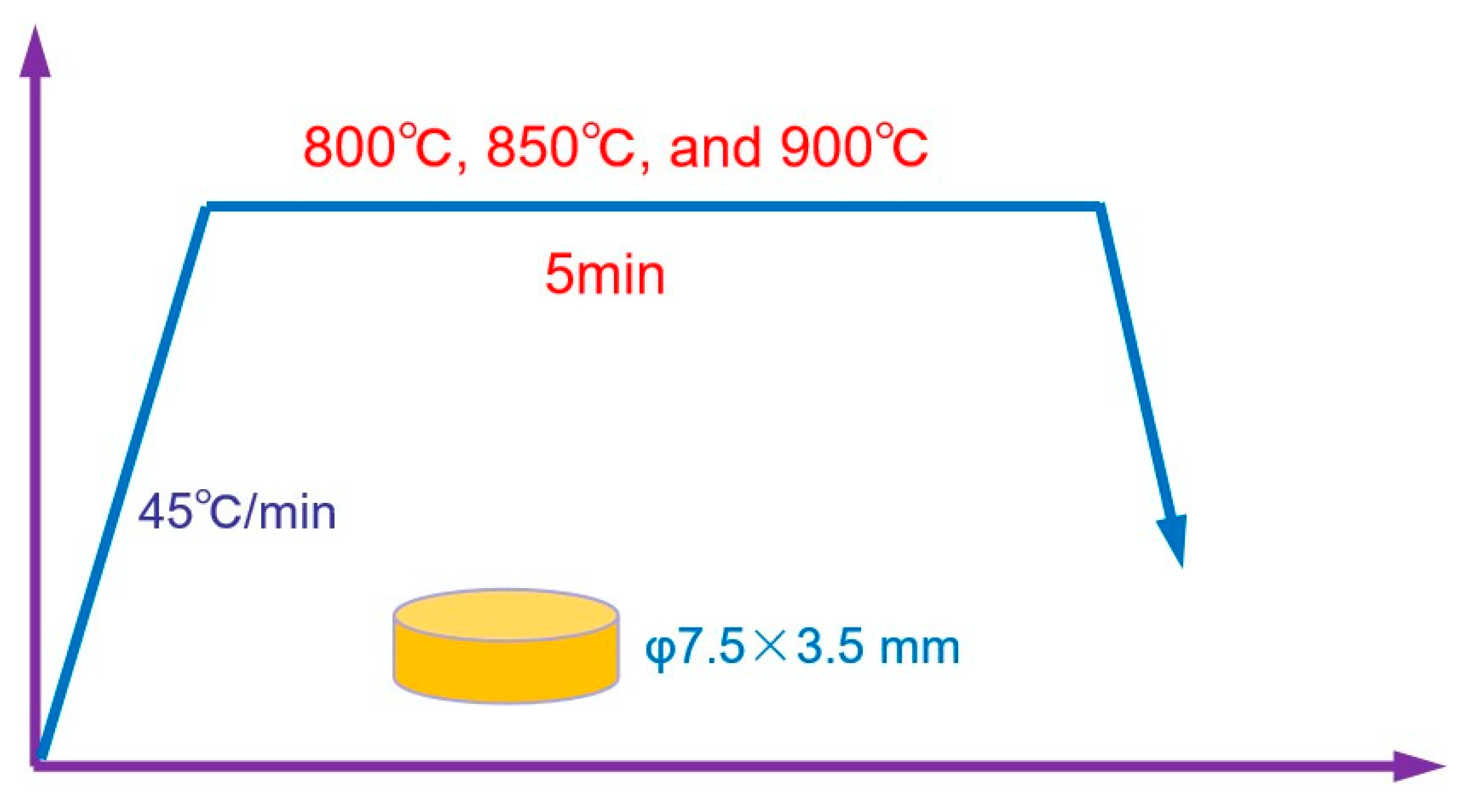

During the HTCLSM experiments, the samples were subjected to a controlled heating schedule. The schematic representation of the experimental procedure was shown in

Figure 2.

The experimental procedure began with heating the samples from room temperature at a rate of 45°C/min up to the target levels of 800°C, 850°C, and 900°C. At each target temperature, an isothermal holding period of 5 minutes was maintained to ensure uniform temperature distribution and microstructural evolution. After the holding phase, the samples were rapidly cooled to room temperature at a rate of 600°C/min, preserving the microstructural characteristics developed during the high-temperature exposure。

This thermal treatment was carefully designed to simulate industrial heat treatment processes and observe microstructural changes, particularly the precipitation of phases, under controlled conditions.

2.4. Microstructural Analysis

Post-experiment analysis of the samples involved several techniques. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was employed to investigate the microstructure and to identify the dark precipitate phase observed during HTCLSM. Elemental analysis of this phase was conducted using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) to determine its composition and distribution. A microhardness tester was used to measure the hardness of the matrix and the precipitate phase. This data was crucial for understanding the strengthening effects of the precipitate. Standard tensile tests were carried out on specimens with a diameter of 10 mm to assess the effect of the heat treatment on the room-temperature mechanical properties. These tests provided insights into the correlation between thermal processing, microstructural evolution, and mechanical performance.

The real-time observations of microstructural changes were correlated with mechanical property data to determine the impact of the dark precipitate phase on the steel's overall performance. Advanced image analysis techniques were employed to quantify grain size, phase distribution, and precipitate morphology. The combination of these analyses provided a detailed understanding of the microstructural evolution during the thermal treatment and its subsequent effect on mechanical properties.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. In-Situ Observation of Microstructural Evolution

In-situ observation of the microstructural changes during the heating process was conducted using High Temperature Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (HTCLSM).

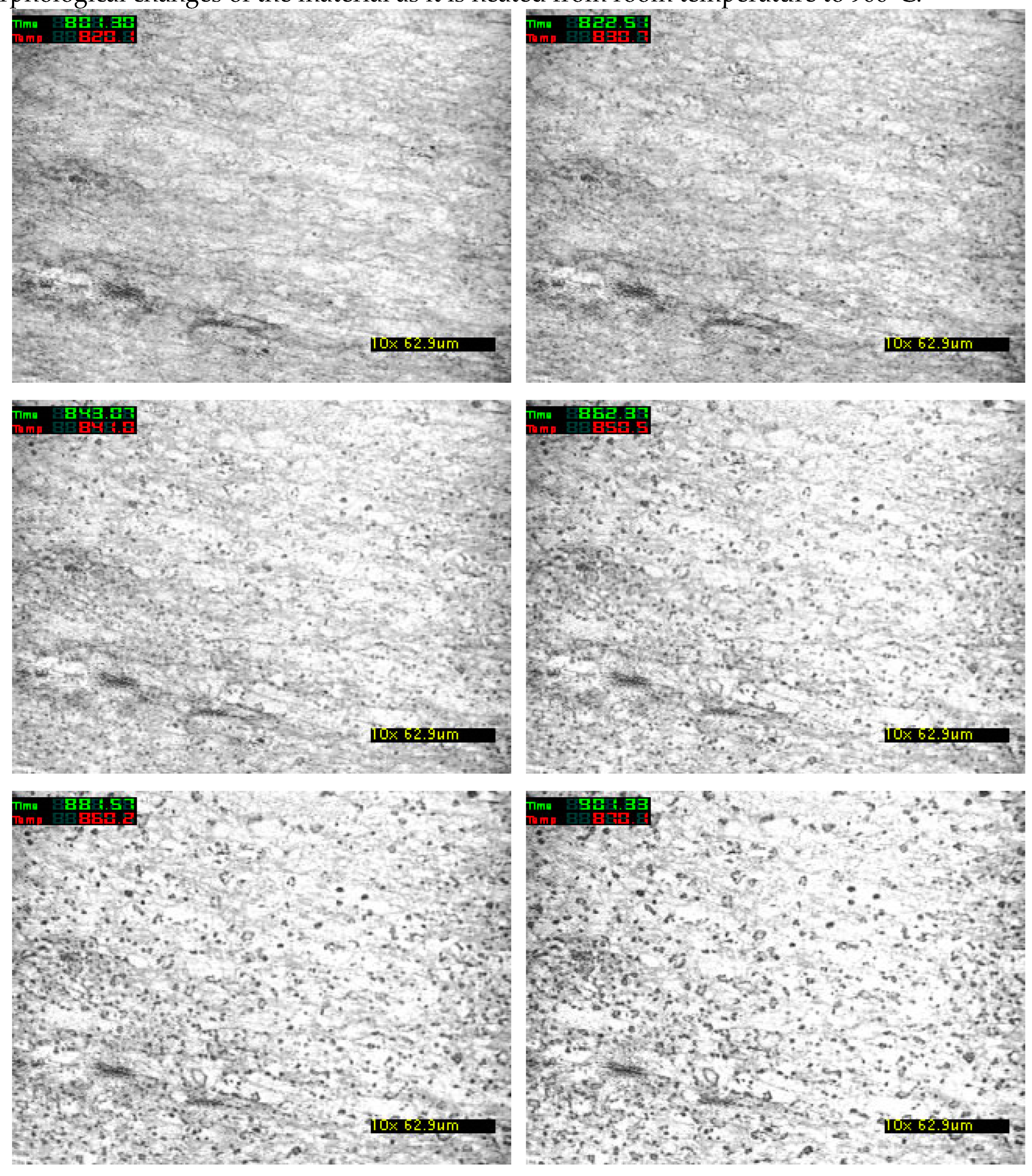

Figure 3 illustrates the morphological changes of the material as it is heated from room temperature to 900°C.

Since there were no significant microstructural changes observed at lower temperatures, the in-situ microstructures before 800°C have not been included in

Figure 3. As depicted in

Figure 3, there were no significant microstructural changes observed up to 800°C. However, upon reaching 820°C, the emergence of dark precipitate phases was evident. This precipitate formation continued to increase in quantity as the temperature rose, particularly in the range of 820°C to 870°C. By 870°C to 900°C, although the size and shape of the precipitates remained relatively stable, their number continued to increase. This increase in quantity was indicated by the deepening color of the precipitates, as shown in the observations.

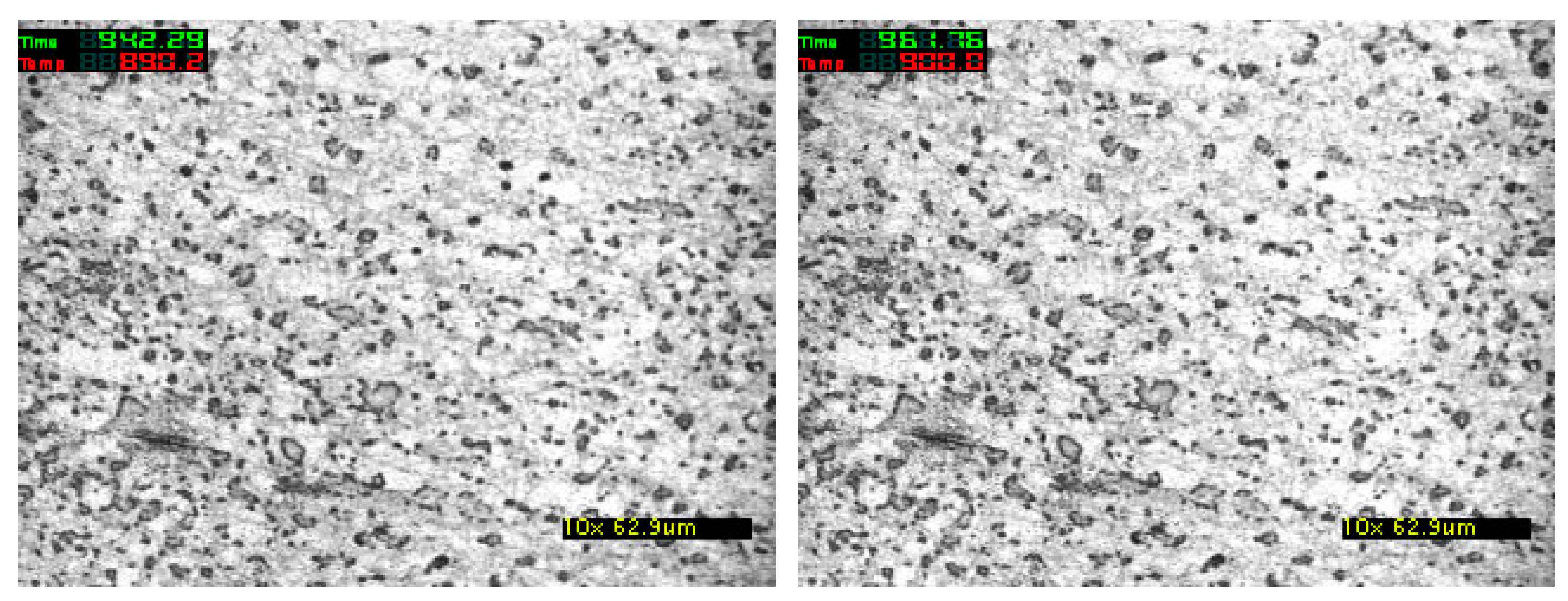

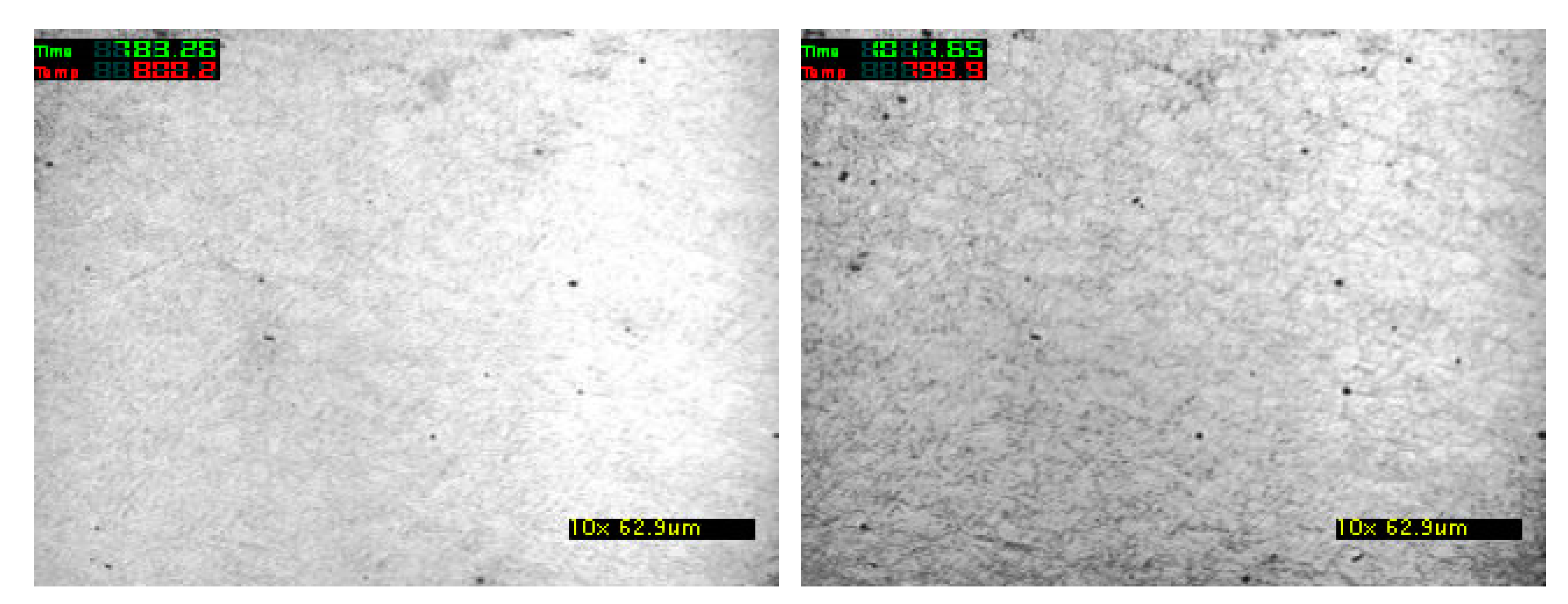

Further in-situ observations during isothermal holding at 900°C and 800°C are illustrated in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

At 900°C, the formation of numerous dark precipitates was observed. Inside the larger precipitates, new precipitates formed over time, resulting in a darker and more intense coloration. This behavior suggests that precipitates nucleate initially at grain boundaries, then grow along these boundaries as the temperature increases and holding time extends. In larger grains, precipitates also nucleate and grow randomly within the grains, leading to further darkening of the precipitate phase. In contrast, at 800°C, the quantity of dark precipitates was significantly lower. As the holding time increased, the number of precipitates remained relatively constant. This observation, depicted in

Figure 5, indicates that the formation of dark precipitates is strongly influenced by temperature. At lower temperatures, such as 800°C, the formation of these precipitates is minimal.

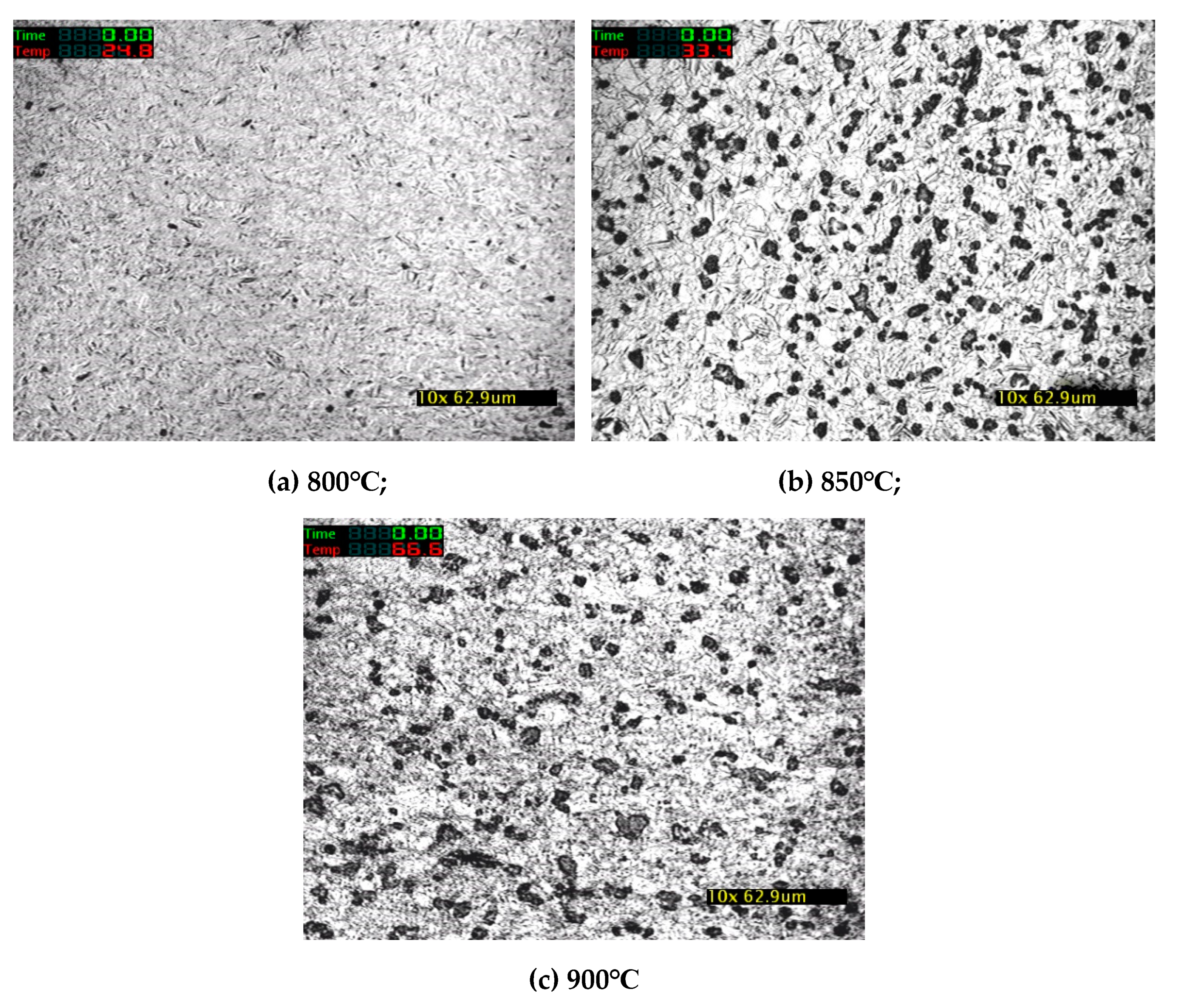

After holding the samples at 800°C, 850°C, and 900°C for 5 minutes, followed by rapid cooling to room temperature to preserve the high-temperature precipitates, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to analyze the precipitates. The results are presented in

Figure 6.

From

Figure 6, it is evident that at 800°C, the precipitates were sparse and primarily distributed along grain boundaries without forming distinct particle shapes (

Figure 6a). At 850°C, there was a noticeable increase in the number and size of the precipitates, which started to exhibit a particulate morphology (

Figure 6b). At 900°C, the number and size of the particulate precipitates were the highest among the temperatures studied, and a substantial amount of dispersed precipitates formed within the grains (

Figure 6c). This further validates the three distinct stages of precipitate formation observed during the experiments.

The observed results highlight the critical role of temperature in precipitate formation and evolution. The increasing number and size of precipitates with higher holding temperatures indicate enhanced precipitation kinetics and a greater driving force for phase transformation. These findings provide valuable insights into the behavior of nickel-containing steels under various thermal conditions, contributing to a deeper understanding of the microstructural evolution during heat treatment processes.

Overall, the detailed in-situ observations and subsequent analyses underscore the importance of precise thermal control in manipulating the microstructure and properties of alloy steels. The ability to monitor these changes in real-time allows for a more thorough understanding of the mechanisms governing precipitate formation and their impact on material performance.

3.2. Analysis of the Precipitation Process of the Dark Phase Precipitates

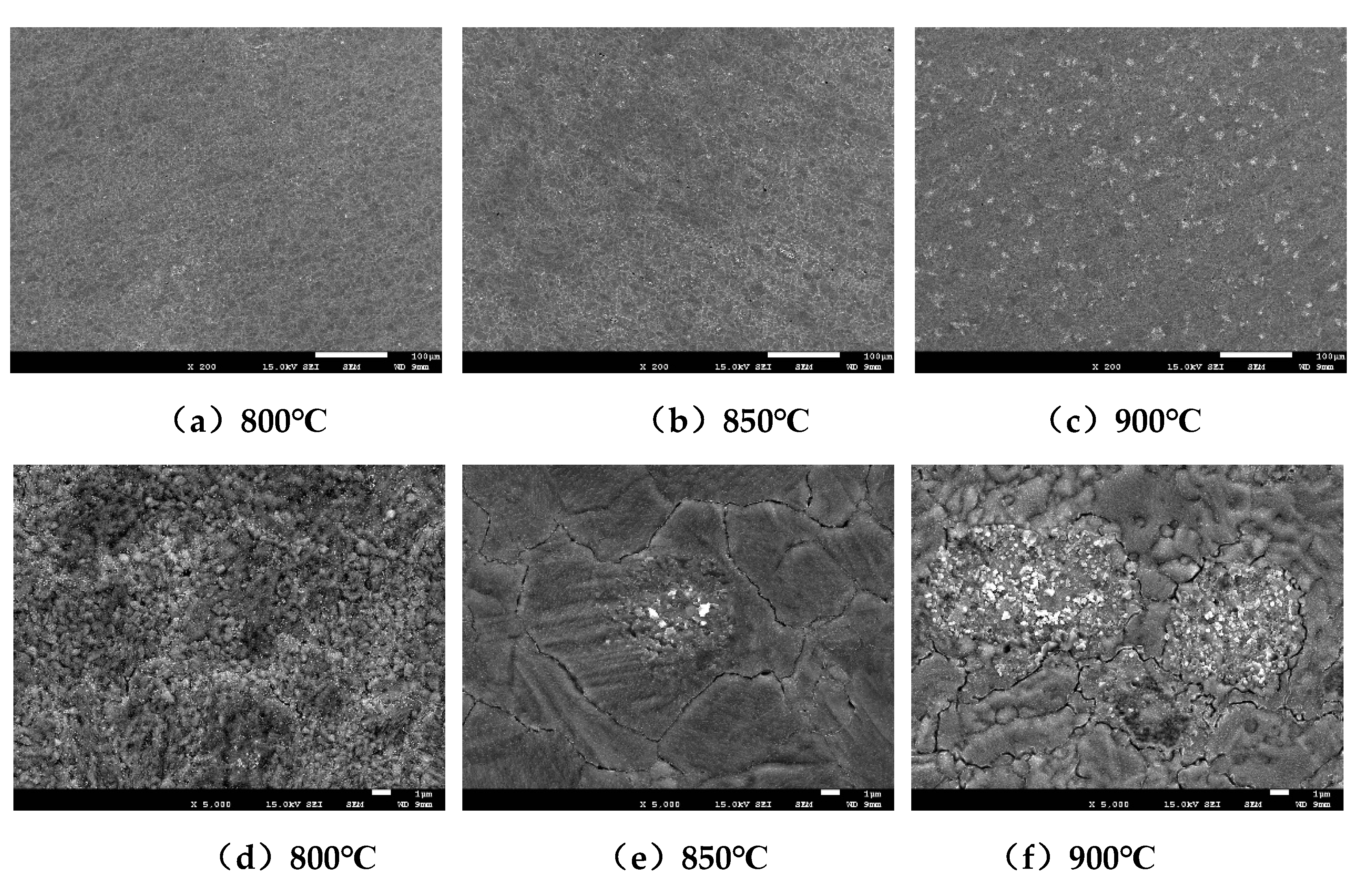

Following in-situ observation, the samples were rapidly cooled to preserve the microstructural features developed during the holding process. The precipitates were then analyzed for their composition, morphology, and distribution using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and microhardness measurements. SEM analysis provided clear insights into the amount, morphology, and distribution of precipitates across different holding temperatures.

Figure 7 displays the SEM images of the materials after a 5-minute hold at various temperatures.

As illustrated in

Figure 7, the number and size of precipitates increase with higher holding temperatures. At 800°C, the precipitates are primarily distributed along grain boundaries, as shown in

Figure 7a and 7d. At 850°C, precipitates are still found along grain boundaries but begin to nucleate and grow within the grains as well, with larger particles visible in

Figure 7e. At 900°C, the density and size of precipitates are the highest among the temperatures studied, with a significant amount of dispersed precipitates forming within the grains (

Figure 7c and 7f).

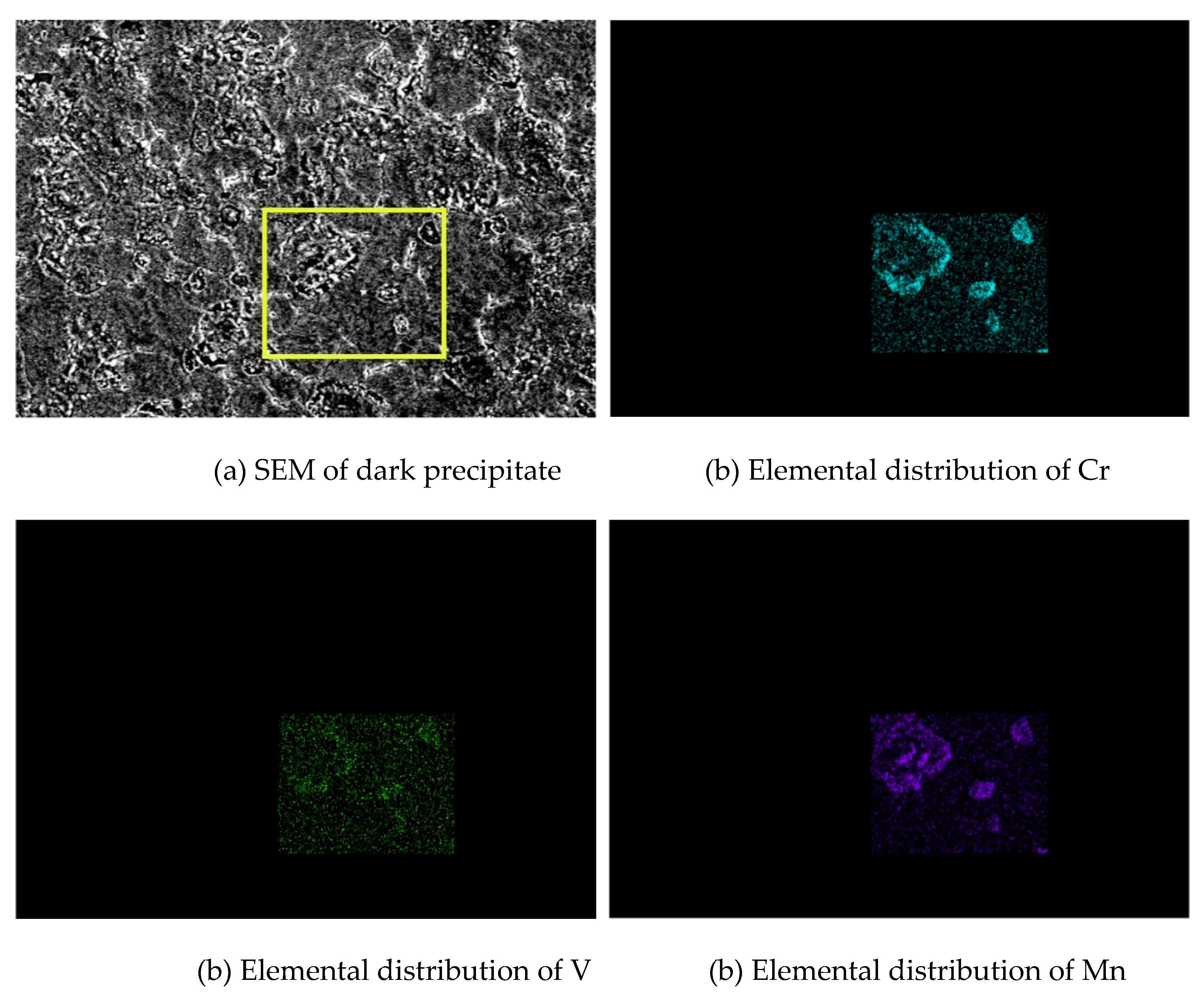

From the elemental distribution map in

Figure 8, it can be observed that the dark precipitates are primarily composed of manganese (Mn), chromium (Cr), and vanadium (V). Specifically, Cr and V are predominantly found along the grain boundaries (

Figure 8c and 8d), while Mn is more concentrated within the grains (

Figure 8b). This segregation indicates that the precipitation of the dark phase may be attributed to the redistribution of these alloying elements during the heat treatment process.

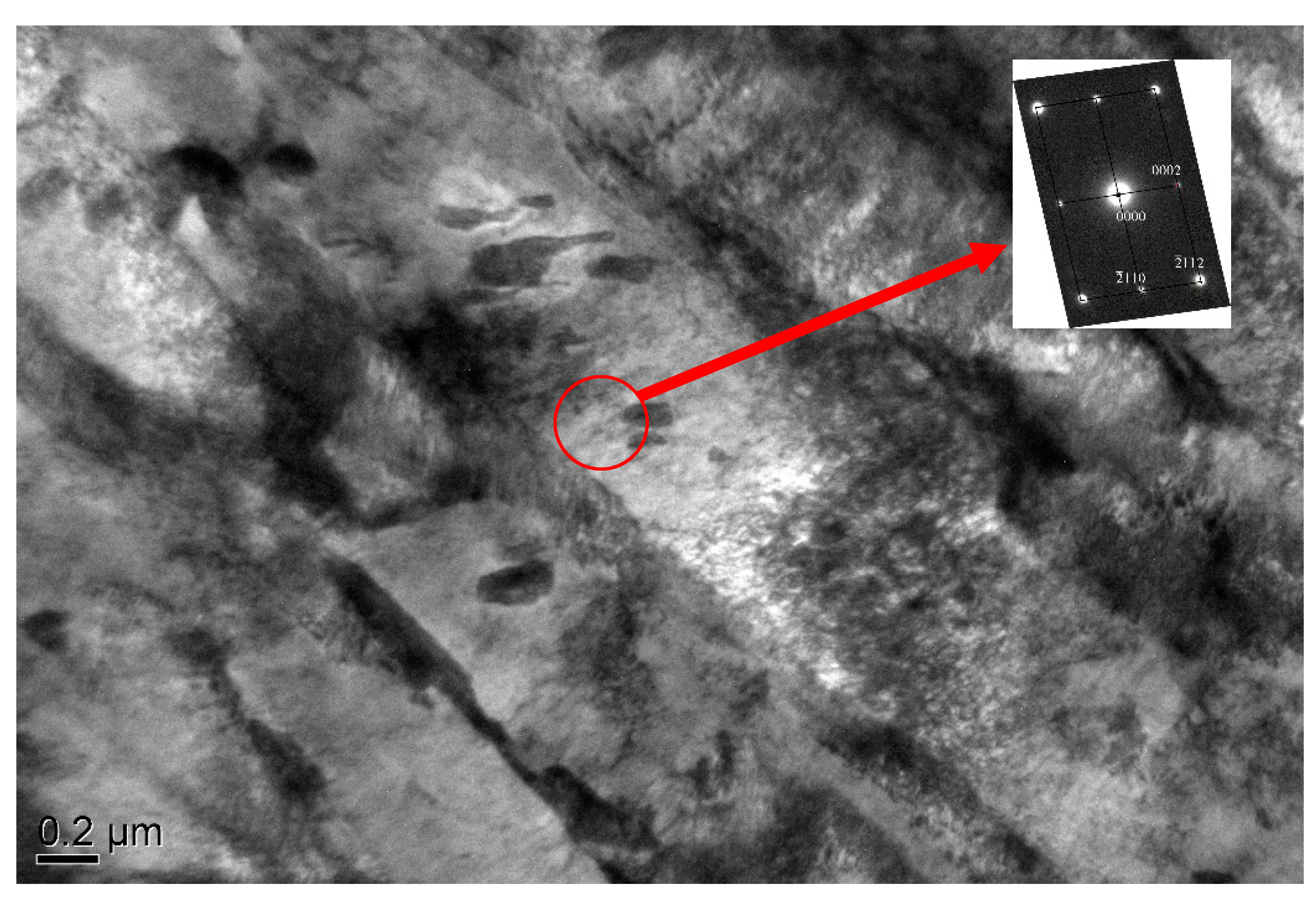

To further understand the nature of the dark phase precipitates, a 2 mm section from the in-situ surface was cut using a linear cutting machine and prepared for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis. The TEM images are presented in

Figure 9.

TEM analysis clearly shows the presence of precipitates. The diffraction pattern of these particles confirms them as chromium carbides (Cr₇C₃). Cr₇C₃ is known for its hardness, which suggests that the dispersion of Cr₇C₃ can significantly enhance the steel's strength.

The formation of dark phase particles depends on nucleation and growth processes. Nucleation involves the formation of small nuclei that grow into new phases. At lower temperatures, such as 800°C, nucleation is suppressed due to low atomic mobility. As the temperature increases, the nucleation rate rises, reaching a peak around 900°C. This explains the pronounced formation of dark phase precipitates at 900°C. With further temperature increases beyond this peak, the nucleation rate increases only slightly, indicating a marginal rise in the number of dark phase precipitates. If the temperature exceeds this optimal range, the number of nuclei may decrease, and instability in the matrix could lead to the dissolution of the dark phase precipitates back into the matrix. In conclusion, controlling the temperature is crucial for managing the quantity and distribution of dark phase precipitates. The results underscore the importance of precise thermal management during processing to optimize the microstructural features and mechanical properties of the material.

3.3. Influence of Dark Phase Precipitates on Material Mechanical Properties

The in-situ observation results indicate that during the heating and isothermal holding processes, a dark phase precipitates within the material. This phase's distribution, morphology, and size significantly affect the material's mechanical properties. To assess the impact of the dark phase precipitates on the material's mechanical performance, a series of experiments were conducted.

Initially, specimens were subjected to in-situ observation at850°C and 900°C for 5 minutes, followed by rapid cooling to room temperature. Subsequently, the microhardness of both the dark phase precipitates and the matrix was measured, as shown in

Figure 10.

From

Figure 10, it is evident that the average microhardness of the dark phase precipitates is 320 HV, whereas the average microhardness of the matrix is 270 HV. The significant increase in hardness of the dark phase precipitates compared to the matrix suggests that the presence of the dark phase precipitates will influence the material’s mechanical performance. To further analyze this effect, we designed a series of heat treatment simulations, as detailed in

Table 2, based on the in-situ observation results and experimental procedures. The specimens were held at 900°C for various times, during which the dark phase precipitated. The specimens were then rapidly quenched in water to preserve the precipitates formed at high temperature. Subsequently, the specimens were machined into 5 mm diameter tensile samples to evaluate the impact of the dark phase precipitates on tensile properties.

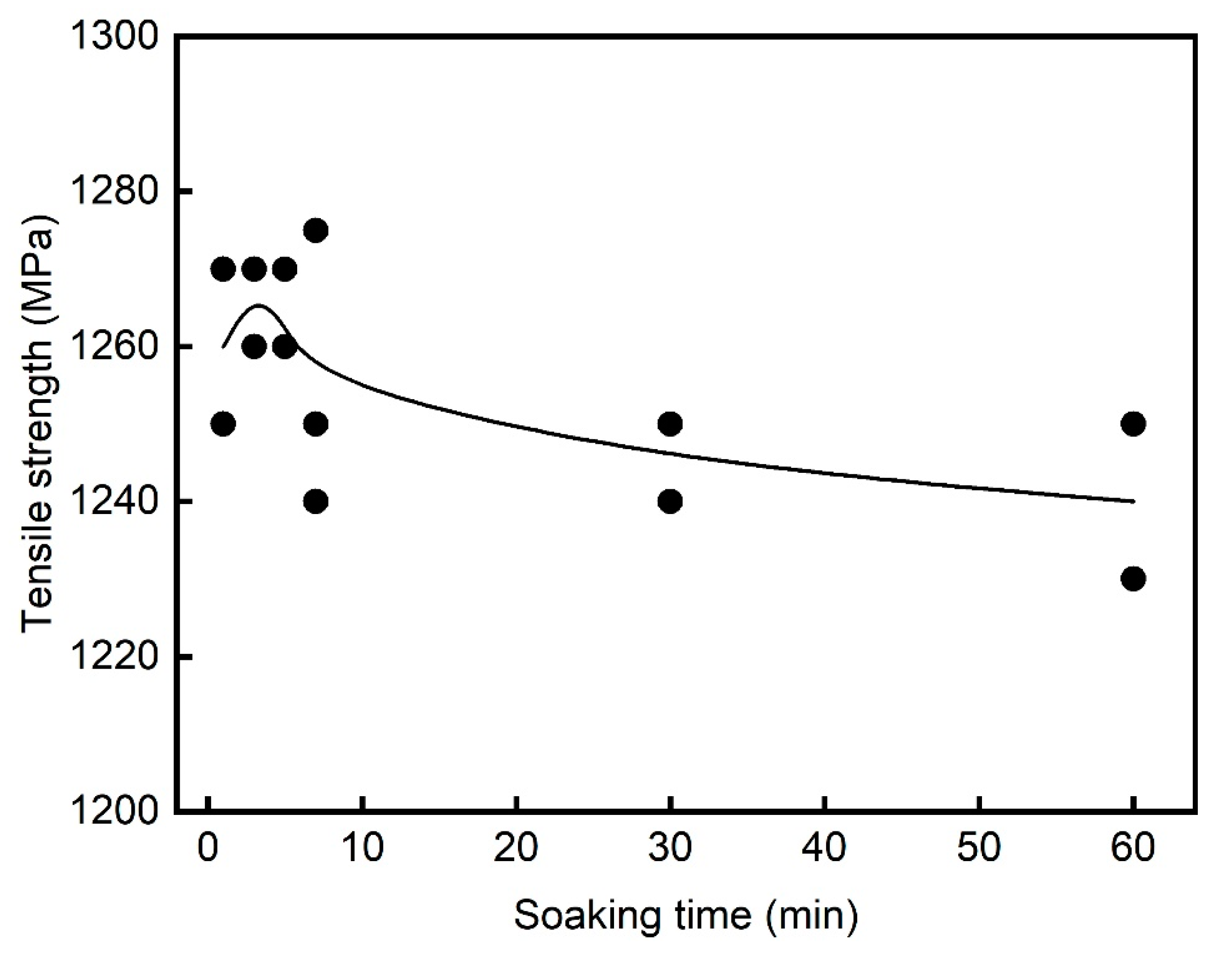

The tensile strength results of the specimens after different soaking times at 900°C and subsequent water quenching are shown in

Figure 11. It is apparent that the precipitation of the dark phase has a substantial effect on the tensile properties of the material. As observed, the tensile strength of the material at room temperature increases with the soaking time up to a maximum value at 3 minutes, after which it decreases with further increase in soaking time.

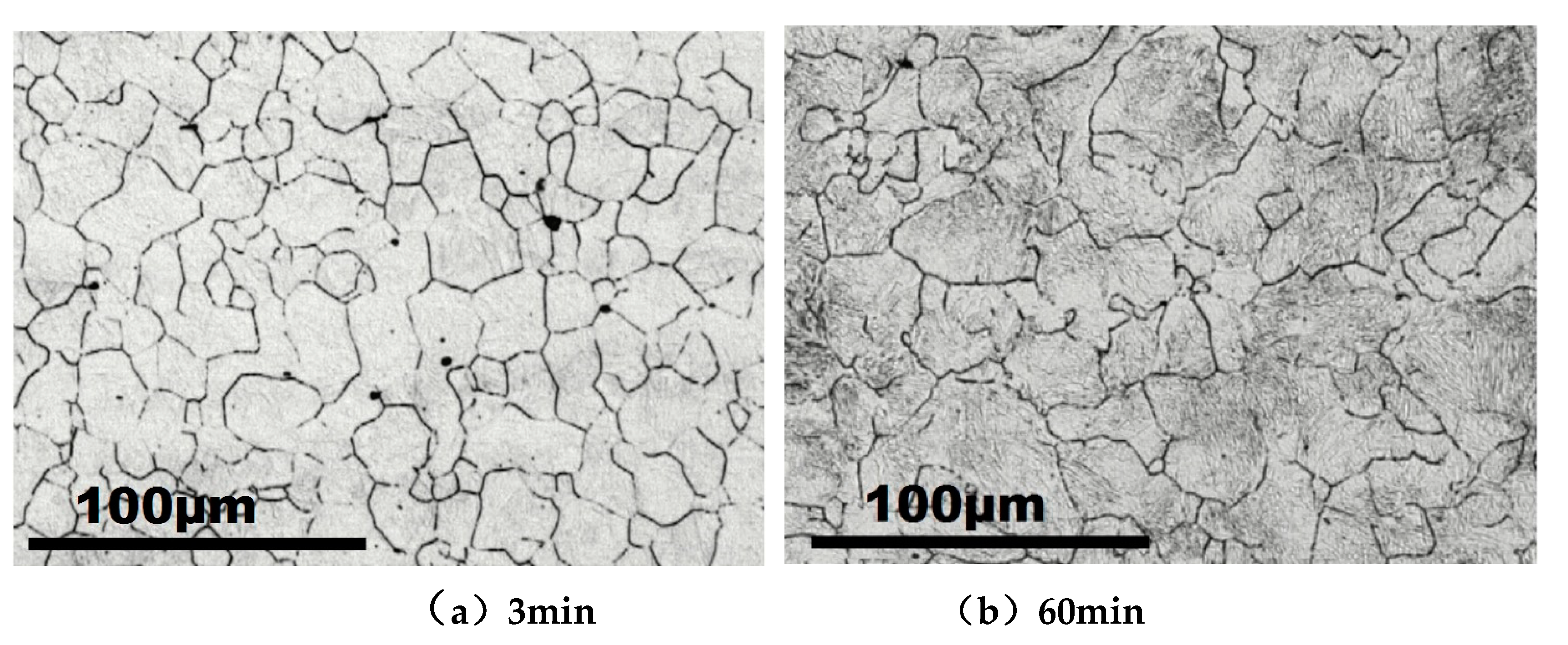

The observed variation in tensile strength can be attributed to the combined effects of the dark phase precipitates and grain size.

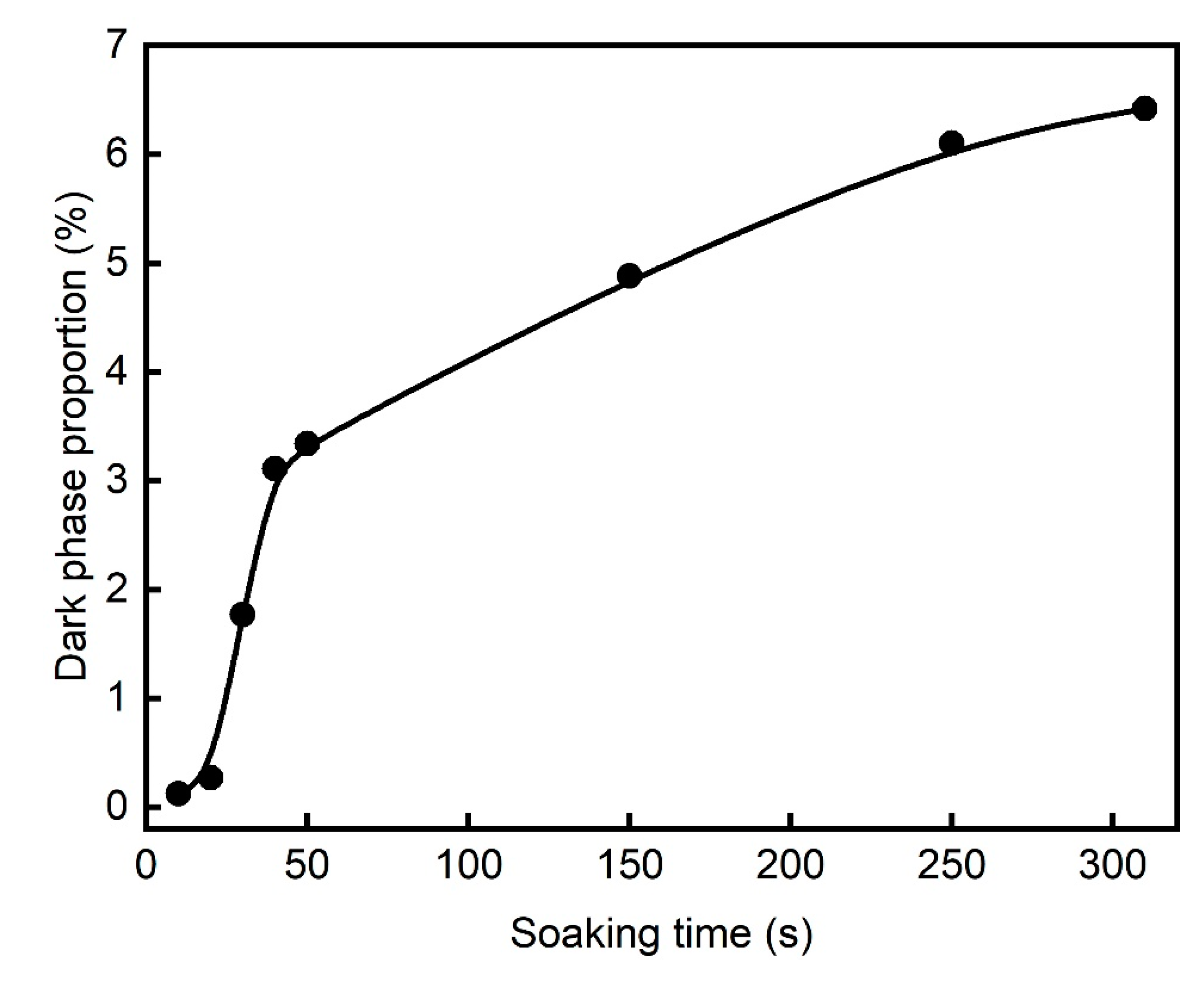

Figure 12 illustrates the increase in the proportion of the dark phase precipitates with soaking time, reaching a maximum at approximately 180 seconds (3 minutes).

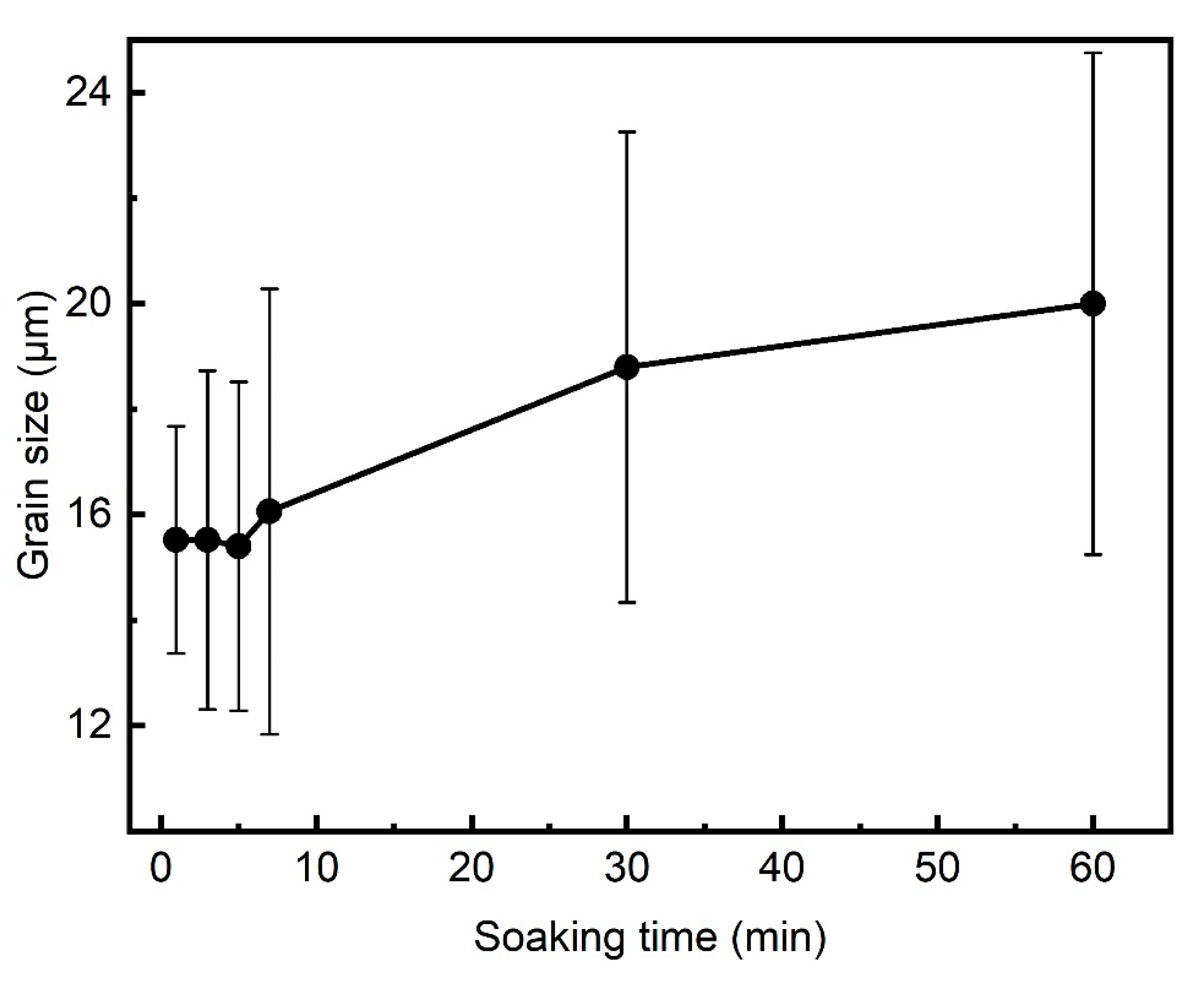

Figure 13 shows that the grain size of the material remains relatively stable during the 1 to 5 minute soaking period. Consequently, the increase in tensile strength from 1 to 3 minutes of holding time is primarily due to the strengthening effect of the dark phase precipitates. After 5 minutes of holding time, the content of the dark phase precipitates reaches its maximum, and its amount does not significantly change with further increases in soaking time. However, the grain size begins to coarsen after 5 minutes, which contributes to the observed reduction in tensile strength, as shown in

Figure 14. This decrease in strength can be attributed to the coarsening of the grain structure, which counteracts the strengthening effect of the dark phase precipitates.

This study elucidates the intricate interplay between dark phase precipitation and mechanical performance in nickel-containing steels subjected to high-temperature heat treatment. The formation and distribution of the dark phase precipitates, primarily characterized by chromium carbides, significantly influence the material’s mechanical properties, particularly its tensile strength. Our findings demonstrate that precise thermal management during the heat treatment process is crucial for optimizing these properties. Specifically, the study reveals that the formation of the dark phase precipitates is highly temperature-dependent, with a notable increase in precipitation and size observed at higher temperatures, up to 900°C. The results underscore the importance of achieving an optimal balance between the amount and distribution of the dark phase precipitates and the resultant grain size. This balance is essential for enhancing the mechanical performance of the steel, as excessive or insufficient precipitation can lead to undesirable changes in strength and ductility. The observed increase in tensile strength with rising holding times up to 3 minutes, followed by a decrease, suggests that there is a critical window during which the dark phase precipitates effectively reinforces the matrix, beyond which further increases in holding time lead to detrimental effects due to grain coarsening.

Furthermore, utilizing High Temperature Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (HTCLSM), the study emphasizes the need for meticulous control of both soaking temperatures and durations to tailor the material’s properties for specific engineering applications. The findings provide valuable insights into the thermal processing parameters that can be adjusted to achieve desired performance outcomes. This research contributes to a deeper understanding of the mechanisms governing phase transformations and their impact on mechanical properties, which is pivotal for advancing the development of high-performance steels used in demanding industrial environments. The careful regulation of heat treatment parameters is integral to optimizing the mechanical properties of nickel-containing steels. The insights gained from this study offer a foundation for further exploration into the precise control of microstructural features to enhance material performance across a range of applications. Future research should focus on refining thermal management strategies and exploring the effects of additional alloying elements to further enhance the understanding of phase transformations and their implications for steel performance.

4. Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the high-temperature behavior of steel, detailing the impact of dark phase precipitates on microstructural changes and mechanical properties. The findings offer valuable insights for optimizing heat treatment processes to enhance material performance for various industrial applications. The key findings of this research are as follows:

(1) The in-situ observations using High Temperature Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (HTCLSM) revealed that during the heating process, the formation of dark phase precipitates initiates around 820°C and continues to increase in quantity as the temperature rises up to 900°C. The precipitates exhibit a growth pattern where their number and size escalate with temperature, but their morphology remains relatively stable after reaching 870°C.

(2) The dark phase precipitates, primarily composed of chromium carbides (Cr7C3), were identified through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). These precipitates form predominantly at grain boundaries and within the grains, enhancing their hardness significantly compared to the surrounding matrix. The analysis confirmed that Cr7C3 precipitates are substantially harder than the base matrix, which is consistent with their role in strengthening the material.

(3) The microhardness measurements demonstrated that the dark phase precipitates significantly enhance the hardness of the steel, with an average microhardness of 320 HV compared to 270 HV for the matrix. Tensile tests indicated that the tensile strength of the material increases with soaking time up to 3 minutes at 900°C due to the strengthening effect of the dark phase precipitates. Beyond this point, the tensile strength begins to decline, attributed to the coarsening of the grains, which outweighs the strengthening effect of the precipitates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Guojin Sun; methodology, Guojin Sun, Zhenggui Li and Qi Wang; formal analysis, Guojin Sun, Qi Wang and Zhenggui Li; investigation, Guojin Sun ,Qi Wang and Zhenggui Li; data curation, Guojin Sun and Qi Wang ; writing—original draft preparation, Guojin Sun; writing—review and editing, Guojin Sun and Zhenggui Li; supervision, Guojin Sun and Zhengui Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from Kunlun Talent Project of Qinghai Province(2023-QLGKLYCZX-032).

References

- Petrova, L.G. , Demin, P.E., Sergeeva, A.S. et al. Surface Alloying of Carbon Steel with Chromium, Nickel, and Nitrogen. Russ. Engin. Res. 41, 551–554 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Pukhova, E.A. , Byshueva, E.G., Domarov, E.V. et al. Effect of Molybdenum Electron-Beam Cladding on the Heat and Wear Resistances of Surface Layers of Chromium-Nickel Austenitic Steel 12Kh18N9T. Met Sci Heat Treat 65, 629–634 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. , Zhao, Hl., Wang, Bx. et al. Impact of Mo/Ni alloying on microstructural modulation and low-temperature toughness of high-strength low-alloy steel. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 31, 1746–1762 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Sheik, S. , Mohammed, R. Effect of Isothermal Ageing on Microstructure and Corrosion Behavior of Nickel and Molybdenum-Free High Nitrogen Austenitic Stainless Steel. J. of Materi Eng and Perform (2024). [CrossRef]

- Hai, C. , Zhu, Y., Fan, E. et al. Effects of the microstructure and retained/reversed austenite on the corrosion behavior of NiCrMoV/Nb high-strength steel. npj Mater Degrad 7, 40 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Bhan, S. , Rawat, P., Das, S. et al. Origins of Strength, Strain Hardening, and Fracture in B2 Tailored Fe–0.8C–15Mn–10Al–5Ni Wt Pct Austenitic Low Density Steel. Metall Mater Trans A 54, 4080–4099 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Niu, J. , Cui, B., Jin, H. et al. Effect of Post-Weld Aging Temperature on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Weld Metal of 15-5 PH Stainless Steel. J. of Materi Eng and Perform 29, 7026–7033 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.D.S. , Raimundo, R.A., Morales, M.A. et al. Evaluation of the spinodal decomposition mechanism in 22Cr–5Ni duplex stainless steel using low-field magnetic analysis. MRS Communications 11, 470–475 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. , Hu, S., Wang, K. et al. Effect of Silicon Micro-Alloying on the Thermal Conductivity, Mechanical Properties and Rheological Properties of the Al–5Ni Cast Alloy. Inter Metalcast (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wei, X. , Gong, T., Cao, X. et al. Effects of Lath Boundary Segregation and Reversed Austenite on Toughness of a High-Strength Low-Carbon Steel. Metall Mater Trans A 55, 1484–1494 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.U. , Kim, I.S., Choi, B.G. et al. On the Role of Grain Boundary Serration in Simulated Weld Heat-Affected Zone Liquation of a Wrought Nickel-Based Superalloy. Metall Mater Trans A 43, 173–181 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Li, J. , Li, Y., Liu, D. et al. The Influence of Microstructure Evolution in Thick Plate 9%Ni Steel Submerged Arc Welding Joint on Fracture Toughness Properties. J. of Materi Eng and Perform (2023). [CrossRef]

- Frichtl, M. , Anwar, Y., Strifas, A. et al. Improving the Low-Temperature Toughness of a High-Strength, Low-Alloy Steel with a Lamellarization Heat Treatment. Met. Mater. Int. 29, 879–891 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, K.D. , Gavze, A.L. & Pavlov, A.A. Influence of Final Heat Treatment Modes on Structure and Properties of High Strength Sheet Steel. Steel Transl. 53, 701–706 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Halfa, H. , Amer, A.E. & Eissa, M. Production and Characterization of an Economical 1100 MPa Advanced High-Strength Silicon-Containing Steel. Metallogr. Microstruct. Anal. 13, 40–61 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Del Molino, E. , Arribas Telleria, M., Gilliams, C. et al. Influence of Ni and Process Parameters in Medium Mn Steels Heat Treated by High Partitioning Temperature Q&P Cycles. Metall Mater Trans A 53, 3937–3955 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. , Han, S. Hot Deformation Behavior and Dynamic Recrystallization Characteristics in a Low-Alloy High-Strength Ni–Cr–Mo–V Steel. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 31, 963–974 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Li, Dl. , Fu, Gq., Zhu, My. et al. Effect of Ni on the corrosion resistance of bridge steel in a simulated hot and humid coastal-industrial atmosphere. Int J Miner Metall Mater 25, 325–338 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. , Li, J., Li, J. et al. Effect of Cooling Rate on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of a Microlaminated Low-Density Steel. J. of Materi Eng and Perform 33, 451–462 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, E. , Luo, Q. & Owens, D. Microstructural Characteristics and Mechanical Properties of Low-Alloy, Medium-Carbon Steels After Multiple Tempering. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 32, 74–88 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Rozman, K.A. , Nealley, W.H.H., Nakano, J. et al. Use of Confocal Microscope for Environmental Tensile Mechanical Testing. JOM 70, 2270–2276 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Mu, W. , Hedström, P., Shibata, H. et al. High-Temperature Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy Studies of Ferrite Formation in Inclusion-Engineered Steels: A Review. JOM 70, 2283–2295 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Yin H, Emi T, Shibata H.Morphological instability of δ-ferrite/γ-austenite interphase boundary in low carbon steels[J].Acta Materialia, 1999, 47(5):1523-1535. [CrossRef]

- Tian, J. , Xu, G., Wang, L. et al. In Situ Observation of the Lengthening Rate of Bainite Sheaves During Continuous Cooling Process in a Fe–C–Mn–Si Superbainitic Steel. Trans Indian Inst Met 71, 185–194 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Chikama H, Shibata H, Emi T,et al."In-situ" Real Time Observation of Planar to Cellular and Cellular to Dendritic Transition of Crystals Growing in Fe–C Alloy Melts[J].materials transactions, 2007, 37(4):620-626. [CrossRef]

- Zou, X. , Sun, J., Matsuura, H. et al. In Situ Observation of the Nucleation and Growth of Ferrite Laths in the Heat-Affected Zone of EH36-Mg Shipbuilding Steel Subjected to Different Heat Inputs. Metall Mater Trans B 49, 2168–2173 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q. , Wang, G., Shang, D. et al. In Situ Observation of the Precipitation, Aggregation, and Dissolution Behaviors of TiN Inclusion on the Surface of Liquid GCr15 Bearing Steel. Metall Mater Trans B 49, 3137–3150 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Mao, Gj. , Cao, R., Chen, Jh. et al. In-situ observation of microstructural evolution in reheated low carbon bainite weld metals with various Ni contents. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 24, 1206–1214 (2017). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).