Submitted:

04 August 2024

Posted:

05 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Methods

Data Collection

Surgical Techniques

Statistical Analysis

Results

Preoperative Characteristics

Operative Characteristics

Postoperative Characteristics

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusions

Funding

IRB

Consent statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- www.mha.org.uk. Accessed 18th May 2023.

- Ohri, S.K.; Benedetto, U.; Luthra, S. , et al. Coronary artery bypass surgery in the UK, trends in activity and outcomes from a 15-year complete national series. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021, 61, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biancari, F.; Vasques, F.; Benenati, V.; Juvonen, T. Contemporary results after surgical repair of type A aortic dissection in patients aged 80 years and older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011, 40, 1058–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemli, J.M.; Pupovac, S.S.; Gleason, T.G.; Sundt, T.M.; Desai, N.D.; Pacini, D.; Ouzounian, M.; Appoo, J.J.; Montgomery, D.G.; Eagle, K.A.; Ota, T.; et al. Management of acute type A aortic dissection in the elderly: an analysis from IRAD. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 2022, 61, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Asai, T.; Kinoshita, T. Emergency surgery for acute type A aortic dissection in octogenarians without patient selection. Ann Thorac Surg 2019, 107, 1146–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahito, K.; Kimura, N.; Yamaguchi, A.; Aizawa, K.; Misawa, Y.; Adachi, H. Early and late surgical outcomes of acute type A aortic dissection in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Surg 2018, 105, 137–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atsushi Omura, A.; Matsuda, H.; Minami, H.; et al. Early and late outcomes of operation for acute type A aortic dissection in patients aged 80 years and older. Ann Thorac Surg 2017, 103, 131–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, M.; Sezai, A.; Niino, T.; et al. Should emergency surgical intervention be performed for an octogenarian with type A acute aortic dissection? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008, 135, 1042–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampoldi, V.; Trimarchi, S.; Eagle, K.M.; et al. ; Trimarchi, S.; Eagle, K.M.; et al. on behalf of the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) Investigators. Simple risk models to predict surgical mortality in acute type A aortic dissection: The international of acute aortic dissection score. Ann Thorac Surg 2007, 83, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Piccardo, A.; Regesta, T.; Zannis, K.; et al. Outcomes after surgical treatment for type A acute aortic dissection in octogenarians: a multicenter study. Ann Thorac Surg 2009, 88, 491–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, F.H.; Schlosser, F.J.; Indes, J.E.; et al. Management of type A aortic dissections: a meta-analysis of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg 2010, 89, 2061–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.E.S.; Papadopoulos, N.; Detho, F.; et al. Surgical repair for acute type A aortic dissection in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Surg 2015, 99, 547–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isselbacher, E.M.; Preventza, O.; Hamilton Black, J. , 3rd Augoustides, J.G.; Beck, A.W.; Bolen, M.A.; Braverman, A.C.; Bray, B.E.; Brown-Zimmerman, M.M.; Chen, E.P.; Collins, T.J.; DeAnda AJr Fanola, C.L.; Girardi, L.N.; Hicks, C.W.; Hui, D.S.; Schuyler Jones, W.; Kalahasti, V.; Kim, K.M.; Milewicz, D.M.; Oderich, G.S.; Ogbechie, L.; Promes, S.B.; Gyang Ross, E.; Schermerhorn, M.L.; Singleton Times, S.; Tseng, E.E.; Wang, G.J., Woo. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. YJ. Circulation. 2022, 146, e334–e482. [Google Scholar]

- Malvindi, P.G.; Modi, A.; Miskolczi, S.; Kaarne, M.; Velissaris, T.; Barlow, C.; Ohri, S.K.; Tsang, G.; Livesey, S. Open and closed distal anastomosis for acute type A aortic dissection repair. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016, 22, 776–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahito, K.; Kimura, N.; Yamaguchi, A.; Aizawa, K.; Misawa, Y.; Adachi, H. Early and late surgical outcomes of acute type A aortic dissection in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Surg 2018, 105, 137–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omura, A.; Matsuda, H.; Minami, H.; Nakai, H.; Henmi, S.; Murakami, H.; et al. Early and late outcomes of operation for acute type A aortic dissection in patients aged 80 years and older. Ann Thorac Surg 2017, 103, 131–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushita, A.; Tabata, M.; Fukui, T.; Sato, Y.; Matsuyama, S.; Shimokawa, T.; et al. Outcomes of contemporary emergency open surgery for type A acute aortic dissection in elderly patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014, 147, 290–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, T.; Yamamoto, H.; Miyata, H.; Motomura, N.; Tokuda, Y.; Tanemoto, K.; Usui, A.; Takamoto, S. Patient trends and outcomes of surgery for type A acute aortic dissection in Japan: an analysis of more than 10 000 patients from the Japan Cardiovascular Surgery Database. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020, 57, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Matsuda, H.; Uchida, K.; Komiya, T.; Koyama, T.; Yoshino, H.; Ito, T.; Shiiya, N.; Saiki, Y.; Kawaharada, N.; Nakai, M.; Iba, Y.; Minatoya, K.; Ogino, H. Analysis of Acute Type A Aortic Dissection in Japan Registry of Aortic Dissection (JRAD). Ann Thorac Surg. 2020, 110, 790–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bojko, M.M.; Suhail, M.; Bavaria, J.E.; Bueker, A.; Hu, R.W.; Harmon, J.; Habertheuer, A.; Milewski, R.K.; Szeto, W.Y.; Vallabhajosyula, P. Midterm outcomes of emergency surgery for acute type A aortic dissection in octogenarians. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022, 163, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumfarth, J.; Peterss, S.; Luehr, M.; Etz, C.D.; Schachner, T.; Kofler, M.; Ziganshin, B.A.; Ulmer, H.; Grimm, M.; Elefteriades, J.A.; Mohr, F.W. Acute type A dissection in octogenarians: does emergency surgery impact in-hospital outcome or long-term survival? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017, 51, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eranki, A.; Merakis, M.; Williams, M.L.; Flynn, C.D.; Villanueva, C.; Wilson-Smith, A.; Lee, Y.; Mejia, R. Outcomes of surgery for acute type A dissection in octogenarians versus non-octogenarians: a systematic review and meta analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg 2022, 17, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyama, T.; Kunisawa, S.; Fushimi, K.; Sawa, T.; Imanaka, Y. Comparison of surgical and conservative treatment outcomes for type a aortic dissection in elderly patients. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazy, T.; Eraqi, M.; Mahlmann, A.; Hegelmann, H.; Matschke, K.; Kappert, U.; Weiss, N. Quality of Life after Surgery for Stanford Type A Aortic Dissection: Influences of Different Operative Strategies. Heart Surg Forum. 2017, 20, E102–E106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jussli-Melchers, J.; Panholzer, B.; Friedrich, C.; et al. Long-term outcome and quality of life following emergency surgery for acute aortic dissection type A: a comparison between young and elderly adults. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017, 51, P465–P471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G.H.; Malekan, R.; Yu, C.J.; et al. Surgery for acute type A aortic dissection in octogenarians is justifed. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013, 145(3 Suppl), P186–90. 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashima, Y.; Toyoshima, Y.; Chiba, K.; et al. Physical activities and surgical out-comes in elderly patients with acute type A aortic dissection. J Card Surgery. 2021, 36, 2754–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total | Closed (n=22) | Open (n=28) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (IQR) | 82 (80.3-83.4) | 82.8 (80.3-85) | 81.9(80.4-82.9) | 0.23 |

| Male gender | 21 (42%) | 9 (40.9%) | 12 (42.9%) | 0.89 |

| Log EuroSCORE, % (IQR) | 40.6 (35.6- 59.2) | 40.6 (35.9-57.3) | 39.8 (34.3-59.8%) | 0.95 |

| Angina class 3-4 | 11 (22%) | 4 (18.2%) | 7 (25%) | 0.56 |

| NYHA class 3-4 | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (10.7%) | 0.11 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 4 (8%) | 3 (13.6%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0.19 |

| Previous MI | 2 (4%) | 1 (4.5%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0.86 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (4%) | 1 (4.5%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0.86 |

| Hypertension | 36 (72%) | 16 (72.7%) | 20 (71.4%) | 0.92 |

| Smoking history | 15 (30%) | 7 (31.8%) | 8 (28.6%) | 0.80 |

| Preop renal failure | 3 (6%) | 1 (4.5%) | 2 (7.1%) | 0.70 |

| Preop Hb, g/L (IQR) | 120 (110-133) | 127 (113-137) | 120 (110-124) | 0.05 |

| Preop COPD | 5 (10%) | 2 (9.1%) | 3 (10.7%) | 0.85 |

| Preop neurogical deficit | 2 (4%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.10 |

| Extracardiac arterioathy | 5 (10%) | 1 (4.5%) | 4 (14.3%) | 0.25 |

| LVEF ≤30 | 2 (4%) | 1 (4.5%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0.86 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 12 (24%) | 3 (13.6%) | 9 (32.1%) | 0.13 |

| Preop inotropes | 3 (6%) | 1 (4.5%) | 2 (7.1%) | 0.70 |

| Cause of dissection | ||||

| Hypertension | 44 (88%) | 19 (86.4%) | 25 (89.3%) | |

| Aneurysm | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | |

| Iatrogenic | 5 (10%) | 2 (0.9%) | 3 (10.7%) | |

|

Data are presented as median (quartiles; minimum–maximum) or count (percent). Abbreviations: NYHA – New York Heart Association, MI – myocardial infarction, COPD – chronic obstryctive pulmonary disease, Hb – haemoglobin, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, LOS – length of stay | ||||

| Variable | Total (50) | Closed (n=22) | Open (n=28) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPERATIVE CHARACTERISTICS | ||||

| Cannulation technique | ||||

| Femoral | 31 (62.0%) | 14 (63.6%) | 17 (60.7%) | |

| Subclavian | 10 (20..0%) | 3 (13.6%) | 7 (25.0%) | |

| Central | 7 (14.0%) | 3 13.6%) | 4 (14.3%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (4.0%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0 | |

| XCT, mins (IQR) | 93 (76-130) | 81 (69-112) | 101 (79-146) | 0.31 |

| CPB, mins (IQR) | 187 (121-245) | 115.5 (102-205) | 219 (184-282) | <0.01 |

| TCA, mins (IQR) | n/a | n/a | 26 (20-39) | |

| Neuroprotection | ||||

| Antegrade | 11 (22%) | 1 (4.6%) | 10 (35.7%) | |

| Retrograde | 3 (6.0%) | 0 | 3 (10.7%) | |

| None | 36 (72%) | 21 (95.4%) | 15 (53.6%) | |

| Aortic procedures | ||||

| 1. Interposition tube graft without extension into the arch | 31 (62%) | 19 (86.4%) | 12 (42.9%) | |

| 2. Interposition tube graft with extension into the arch | 13 (26%) | 1 (0.45%) | 12 (42.9%) | |

| 3. Interpositional graft + separate valve | 6 (12%) | 2 (0.9%) | 4 (14.3%) | |

| Other concomitant procedures 1. Aortic valve/root repair/replacement 2. Coronary artery bypass |

10 (20%) 4 (8%) |

5 (22.7 %) 2 (9.1%) |

5 (17.9%) 2 (7.1%) |

0.28 |

| POSTOPERATIVE CHARACTERISTICS | ||||

| Return to theatre | 3 (6%) | 1 (4.5%) | 2 (7.1%) | 0.70 |

| New TIA | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (10.7%) | 0.11 |

| New Stroke | 13 (26%) | 5 (22.7%) | 8 (28.6%) | 0.64 |

| New CVA | 16 (32%) | 5 (22.7%) | 11 (39.3%) | 0.21 |

| RRT | 4 (8%) | 2 (9.1%) | 2 (7.1%) | 0.80 |

| LOS, days (IQR) | 14.6 (8.0-20.7) | 13.8 (3.3-19.4) | 14.6 (8.8-20.9) | 1.00 |

| LOS ≥ 30 days | 5 (10%) | 1 (4.5%) | 4 (14.3%) | 0.25 |

| In-hospital mortality | 9 (18%) | 5 (22.7%) | 4 (14.3%) | 0.44 |

| Composite endpoint* | 26 (52%) | 10 (45.5%) | 16 (57.1%) | 0.41 |

| Discharge destination | ||||

| Home | 17 (34%) | 7 (31.8%) | 10 (35.7%) | |

| Convalescence | 16 (32%) | 7 (31.8%) | 9 (32.1%) | |

| Other hospital | 8 (16%) | 3(13.6%) | 5 (17.9%) | |

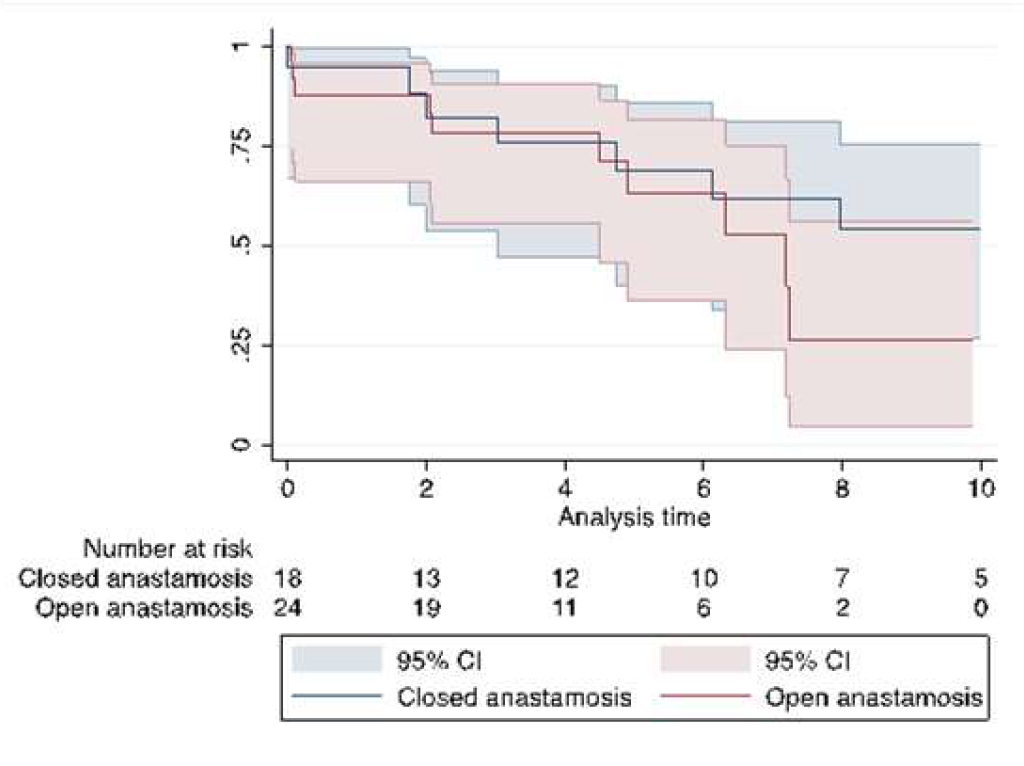

| Median survival, years (IQR) | 7.2 (4.5-11.6) | 10.6 (4.7-11.6) | 7.2 (4.5-8.1) | 0.35 |

| Survival | ||||

| 6 months | 76 ± 6.0% | 77.3 ± 8.9% | 85.7 ± 6.6% | 0.08 |

| 1 year | 75.8 ± 6.1% | 76.7 ± 9.1% | 75.0 ± 8.2% | 0.61 |

| 5 years | 55.1 ± 7.7% | 56.3 ± 11.0% | 52.9 ± 11.2% | 0.18 |

|

Data are presented as median (IQR – Inter quartile Range) or count (percent). Abbreviations: CBP – cardiopulmonary bypass time, CVA – cerebrovascular accident,TCA – total circulatory arrest time, LOS – length of stay, RRT – renal replacement therapy, TIA – transient ischemic attack, XCT - cross clamp time. *Composite endpoint of:RRT, new CVA, LOS≥30 days, return to theatre, in-hospital mortality | ||||

| Univariable | Multivariable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 95% Confidence interval | P value | Included in multivariable model? | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 95% Confidence interval | P value |

| Preoperative | |||||||

| Age | 1.03 | 0.75, 1.40 | 0.87 | N | |||

| Female gender | 0.18 | 0.035, 0.84 | 0.03 | Y | 0.35 | 0.03 – 3.5 | 0.37 |

| Log EuroSCORE | 9.69 | 0.20, 458.1 | 0.25 | N | |||

| Angina class 3-4 | 1.14 | 0.23, 5.67 | 0.87 | N | |||

| NHYA class ≥3 | 9.0 | 1.03, 78.7 | 0.047 | Y | 0.24 | 0.004, 14.8 | 0.50 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 3.24 | 1.11, 9.49 | 0.03 | Y | 1.4 | 0.35, 5.8 | 0.62 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4.76 | 0.44, 51.52 | 0.20 | N | |||

| Hypertension | 2.68 | 0.42, 17.12 | 0.30 | N | |||

| Smoking history | 0.81 | 0.25, 2.70 | 0.74 | N | |||

| Preop creatinine | 1.02 | 1.00, 1.03 | 0.05 | Y | 1.03 | 0.99, 1.1 | 0.17 |

| Preop Hemoglobin | 1.01 | 0.97, 1.06 | 0.62 | N | |||

| Preop COPD | 3.67 | 0.61, 22.22 | 0.16 | N | |||

| Preop neurology Hx | 0.83 | 0.04, 18.8 | 0.91 | N | |||

| Extracardiac arteriopathy | 1.47 | 0.20, 10.78 | 0.70 | N | |||

| LVEF <30 | 27.67 | 1.20, 635.62 | 0.038 | Y | 1.39 | 0.03, 81.2 | 0.87 |

| Critical preop state* | 1.27 | 0.30, 5.46 | 0.75 | N | |||

| Operative | |||||||

| Additional procedures | 6.68 | 1.49, 29.93 | 0.01 | Y | 1.41 | 0.12, 15.8 | 0.78 |

| Open distal anastomosis | 0.58 | 0.15, 2.34 | 0.45 | N | |||

| CPB time (mina) | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.03 | 0.008 | Y | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.03 | 0.44 |

| Postoperative | |||||||

| Re-exploration for bleeding | 0.58 | 0.03, 13.19 | 0.725 | N | |||

| RRT | 5.27 | 0.77, 35.89 | 0.09 | N | |||

| New CVA | 0.63 | 0.13, 3.03 | 0.57 | N | |||

| Composite endpoint | 0.75 | 0.18, 3.17 | 0.70 | N | |||

| LOS | 0.85 | 0.76, 0.96 | 0.01 | Y | 0.88 | 0.75, 1.03 | 0.12 |

|

Abbreviations: COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, CPB – cardiopulmonary bypass time, CVA – cerebrovascular accident, LOS – length of stay, NYHA - New York Heart Association, RRT – renal replacement therapy *Critical pre-op: pre-op neuro deficit, pre-op renal failure, inotropes, shock or mechanical ventilation | |||||||

| Variable | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Pre-opa | 3.17 | 1.1, 8.9 | 0.03 |

| Open distal anastomosis | 1.00 | 0.3, 3.1 | 1.00 |

| Concomitant procedure | 1.30 | 0.4, 4.3 | 0.67 |

| Composite endpointb | 4.06 | 1.3, 12.7 | 0.02 |

| Hypertension | 0.40 | 0.1, 1.1 | 0.08 |

|

aCritical pre-op: pre-op neuro deficit, pre-op renal failure, inotropes, shock or mechanical ventilation bComposite endpoint of RRT, new CVA, LOS>=30 days, return to theatre | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).